Abstract

In the last year increased attention has been focused on translating federally sponsored health research into improved health for Americans. Since the passage of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) on February 17, 2009, this focus has been accelerated by ARRA funds to support Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER). A high proportion of topical areas of interest in CER affect the older segment of the population. The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the National Institute on Aging (NIA), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) have supported robust research portfolios focused on aging populations that meet the varying definitions of CER. In this short paper we briefly describe the research missions of the AHRQ, NIA, and VA. We then review the various definitions of CER as put forward by the Congressional Budget Office, the Institute of Medicine, and the ARRA established Federal Coordinating Council; as well as important topics for which CER is particularly needed. Finally, we set forth approaches in which the three agencies support CER involving the aging population and outline opportunities for future CER research.

Keywords: patient outcomes, comparative effectiveness, research

INTRODUCTION

Over the last year, increased attention has been focused on translating federally sponsored health research into improved health for Americans at a cost that allows governments, businesses and families to meet the full range of obligations that they face. Since a high proportion of all health care expenditure for most people occurs in the later years of life, research that affects the elderly may play a particularly important role in defining the methods by which research expenditures improve both health outcomes and healthcare costs. The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the National Institute on Aging (NIA), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) consider research aimed at improving the health and well-being of the elderly as being of paramount importance in meeting their research missions. In this short paper we will briefly describe the research missions of the AHRQ, NIA, and VA. We will then highlight recent work by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the Institute of Medicine (IOM), and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) established Federal Coordinating Council (FCC) in both defining comparative effectiveness research (CER), as well as important topics for which CER is particularly needed. Finally, we will set forth some approaches in which the three agencies support CER involving the aging population.

AGENCY MISSIONS

As one of twelve agencies within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the mission of AHRQ is to improve the quality, safety, efficiency, and effectiveness of health care for all Americans. AHRQ fulfills this mission by developing and working with the health care system to implement information that reduces the risk of harm from health care services by using evidence-based research and technology to promote the delivery of the best possible care, transform the practice of health care to achieve wider access to effective services and reduce unnecessary health care costs, and improve health care outcomes by encouraging providers, consumers, and patients to use evidence-based information to make informed treatment decisions.

As demonstrated in the 2009 report on Research, Condition, and Disease Categories (RCDC), aging research is conducted throughout the National Institutes of Health (NIH)1. However, for the purposes of this paper, focus is placed on the activities of NIA. Congress has charged NIA to provide leadership in aging research, training, health information dissemination, and other programs relevant to aging and older people. Congress has also designated the NIA as the primary Federal agency on Alzheimer’s disease research. NIA carries out this mission by supporting and conducting high-quality research on aging processes, age-related diseases and special problems and needs of the aged, by training and developing highly skilled research scientists from all population groups, developing and maintaining state-of-the-art resources to accelerate research progress, and disseminating information and communicating with the public and interested groups on health and research advances and on new directions for research.

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) was created to fulfill the promise in President Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address – “To care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan” – by serving and honoring the men and women who are America’s veterans. The VA serves the needs of America’s veterans by providing primary care, specialized care, and related medical and social support services through a comprehensive, integrated healthcare system that provides excellence in health care provision, education, and research. VA has a particular obligation to aging Veterans; those receiving care in VA are, on average, older and sicker than the population as a whole, and over 1/3 of the VA patient population is over 65 years of age.

COMPARATIVE EFFECTIVENESS RESEARCH

The CBO has defined “comparative effectiveness” research as “simply a rigorous evaluation of the impact of different options that are available for treating a given medical condition for a particular set of patients”2 (see table 1). Such an evaluation, which may vary from comparisons of two drugs labeled for a narrow indication to comparisons involving dissimilar approaches, such as surgery vs. medication or medication vs. psychotherapy, may focus on medical risks and benefits, cost-effectiveness of the treatments, or both. These evaluations differ from those performed by the FDA, which assesses the safety and effectiveness of a drug, medical device or biologic treatments, assessed against the labeling documents under which marketing will occur3.4. It also differs from the assessment done by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for making coverage decisions, which are based on a demonstration that the proposed intervention is effective in the intended beneficiary population, but for which assessment of alternative approaches is not conducted5. As noted by the CBO, “medical procedures, which account for a much larger share of total spending on health care than drugs and devices do, can achieve widespread use without extensive clinical evaluation.”6 This poses difficulties for a health care system in which over fifty percent of all expenditures are for hospital care and physician services; and in which both physicians and patients look to new, often more expensive, technologies as representing improved care. Unfortunately, the assumption that technological innovation invariably leads to improved outcomes is demonstrably untrue in many cases. Indeed, the CBO cites as an example a project conducted by the VA Cooperative Studies Program on patients who had stable coronary artery disease and were treated either with angioplasty with a metal stent combined with a drug regimen or with the drug regimen alone7. Although patients treated with angioplasty and a stent had better blood flow and fewer symptoms of heart problems initially, the differences declined over time and were accompanied by no differences between the two groups in survival rates or the occurrence of heart attacks over a five-year period.

Table 1.

Comparative Effectiveness Research Definitions

| Congressional Budget Office | Simply a rigorous evaluation of the impact of different options that are available for treating a given medical condition for a particular set of patients |

| Institute of Medicine | CER is the generation and synthesis of evidence that compares the benefits and harms of alternative methods to prevent, diagnose, treat and monitor a clinical condition, or to improve the delivery of care. The purpose of CER is to assist consumers, clinicians, purchasers, and policy makers to make informed decisions that will improve health care at both the individual and population levels. |

| Federal Coordinating Council | “Comparative effectiveness research is the conduct and synthesis of systematic research comparing different interventions and strategies to prevent, diagnose, treat and monitor health conditions. The purpose of this research is to inform patients, providers, and decision-makers, responding to their expressed needs, about which interventions are most effective for which patients under specific circumstances. To provide this information, comparative effectiveness research must assess a comprehensive array of health-related outcomes for diverse patient populations. Defined interventions compared may include medications, procedures, medical and assistive devices and technologies, behavioral change strategies, and delivery system interventions.”9 |

The Institute of Medicine Committee on CER encapsulated the core concepts in the two sentences in table 18. The committee went on to note that “Two key elements that are embedded in this definition are the direct comparison of effective interventions and their study in patients who are typical of day-to-day clinical care. These features would ensure that the research would provide information that decision makers need to know, as would a third feature, research designed to identify the clinical characteristics that predicted which intervention would be most successful in an individual patient. The same research design would also help policymakers, by identifying subpopulations of patients that are most likely to benefit from one intervention or another.”8

The ARRA CER FCC has encapsulated the thoughts expressed by both the CBO and the IOM, as noted in table 1.9 Both the FCC and the IOM have emphasized that effective execution of a CER agenda will require the development of methods and resources that are not currently available. “This research necessitates the development, expansion, and use of a variety of data sources and methods to assess comparative effectiveness.” 9 Both the IOM and FCC broadened the CBO description of CER to include delivery of care, health systems, and other aspects of the health care system.

TOPICS FOR INVESTIGATION

The VA, AHRQ, and NIH/NIA have each sponsored extensive comparative effectiveness research efforts over the years. The Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act (MMA) of 2003 authorized AHRQ to undertake a program of comparative effectiveness research focusing on the beneficiaries of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. AHRQ has focused on methods development for research as well as methods for engaging users of the research in identifying topics to be studied and important health outcomes, studies of different clinical interventions, and the dissemination of comparative effectiveness research results. NIH and VA have focused on the assessments of specific interventional strategies, with the VA focus being driven by the specific healthcare needs of the VA patient population, and NIH strategies being driven by investigator initiated projects and Institute-specific assessments of programmatic priorities and national needs. In spite of these extensive efforts, however, the IOM panel noted that there remain a large number of unmet needs for comparative effectiveness research, listing 100 different priority areas divided into four quartiles9. A large number of these research opportunities have the potential to affect the aging population, and we believe that there are opportunities for individuals and institutions to work with NIA, AHRQ and VA to meet these needs. Areas that we see as having particular importance to the geriatric research community are indicated in table 2. Each of these topics falls within the mission of all three agencies – NIA, AHRQ and VA, although many of the items are so broad that development of a single comprehensive plan to address them is probably not feasible, even if financial resources were unlimited. Refinement of many of the topics is a necessary next step.

Table 2.

Institute of Medicine Recommendations for Comparative Effectiveness Research Affecting the Elderly

First quartile (display within quartile does not indicate priority rank):

|

Second Quartile

|

Third Quartile

|

Fourth Quartile

|

In order to better understand opportunities for CER within each agency, we provide here a brief summary or previously funded CER initiatives.

AGENCY FOR HEALTHCARE RESEARCH AND QUALITY

As mentioned earlier, AHRQ was first authorized to undertake a dedicated program of CER in 2003 as part of the MMA. Initial funding for dedicated CER at AHRQ was $15 million but in fiscal year 2009 the appropriation was increased to $50 million. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) increased the dedicated dollars for CER to $1.1 billion with $300 million remaining at AHRQ, $400 million going to NIH, and $400 million to be allocated at the discretion of the Secretary of Health and Human Services. The Secretary has identified fourteen priority conditions that guide AHRQ research, many of which affect the elderly. The fourteen priority conditions are:

Cancer

Cardiovascular disease, including stroke and hypertension

Dementia, including Alzheimer Disease

Depression and other mental health disorders

Arthritis and non-traumatic joint disorders

Developmental delays, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism

Diabetes Mellitus

Functional limitations and disability

Infectious diseases including HIV/AIDS

Obesity

Peptic ulcer disease and dyspepsia

Pregnancy including pre-term birth

Pulmonary disease/Asthma

Substance abuse

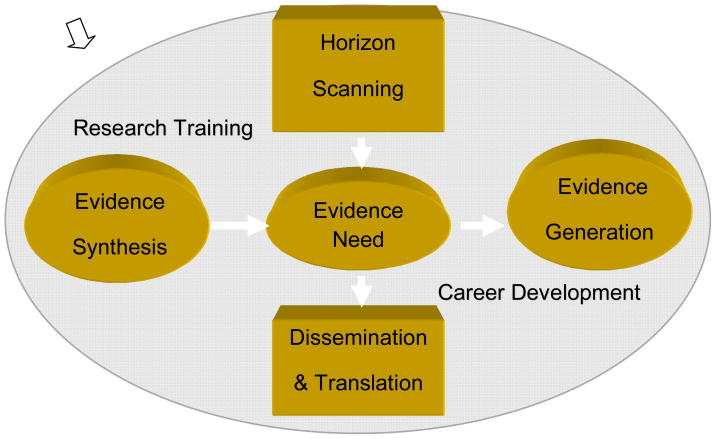

AHRQ has developed a program of CER that encompasses a variety of activities: 1) citizen involvement, 2) transparency, 3) horizon scanning for important areas for research, 3) systematic review, 4) research gap identification, 5) evidence generation, 6) new research, 7) dissemination, translation, and implementation, and 8) training and career development for researchers (see figure 1). These activities provide infrastructure and core support for networks of researchers, including Evidence-based Practice Centers (EPCs), Developing Evidence to Inform Decisions about Effectiveness (DEcIDE) Network, Centers for Education and Research on Therapeutics (CERTs), and investigator initiated funded research, training and career development in CER.

Figure 1.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Stakeholder Input and Involvement Process

AHRQ has supported significant investment in developing pilots for distributed research network (DRN) models to further the goal of developing a learning network for pragmatic CER studies in addition to supporting research consortium in diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease. Further, with current ARRA dollars, AHRQ is funding large pragmatic CER studies under the Clinical and Health Outcomes Initiative in Comparative Effectiveness (CHOICE initiative - $100 million), building new clinical infrastructure for CER through the Prospective Outcome Systems using Patient-specific Electronic data to Compare Tests and therapies (PROSPECT Studies R01 -$44 million) and Electronic Data Methods (EDM) Forum for Comparative Effectiveness Research (U13 - $4 million), Innovative Adaptation and Dissemination of AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Research Products (iADAPT - R18 $29.5 million), Mentored Clinical Scientists Comparative Effectiveness Development Award (K12 - $15 million), Institutional National Research Service Award (NRSA) Postdoctoral Comparative Effectiveness Development Training Award (T32 - $5 million), and the development of an on-going methodology and process for horizon scanning for important CER topics and the establishment of a Citizen’s Forum for CER.

Current information on AHRQ’s Effective Health Care Program and CER can be found at www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov and www.ahrq.gov/fund.

NATIONAL INSTITUTE ON AGING

NIH has been involved with patient outcomes research that fits the varying definitions of CER for many years. Patient centered research has focused on prevention, diagnosis, treatment, behavior change, health systems, and special populations. In FY08 NIH devoted $9.6 billion to clinical research. In initial analysis of ongoing NIH research as compared to the IOM 100 priorities for CER, NIH was supporting research in 88 of the areas identified. NIH has an extensive CER research and training infrastructure, with trial networks, cooperative groups, the NIH consensus development program, CTSAs and community collaborations, integration of CMS and SEER databases, and HMO research networks. Notable recent examples of outcomes from this research include the ALLHAT study10,11 and the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP)12. ALLHAT was a community based study of 33,357 hypertensive individuals that found that an inexpensive generic diuretic was as effective as more expensive agents in reducing heart disease and stroke. The DPP demonstrated that lifestyle intervention was as effective as a drug in the prevention of diabetes in at risk young and middle aged individuals, and was more effective than the drug in the population 60 years of age and older.

With the advent of ARRA, NIH was allocated $400 million of the total $1.1billion assigned to CER, via a pass-through from AHRQ. These funds allowed support for projects that would not otherwise have been feasible. For example, CER funds supported the launch of SPRINT Senior, a collaborative effort of the Heart, Diabetes, Aging, and Neurologic Institutes, (NHLBI, NIDDK, NIA, and NINDS), to compare control of systolic blood pressure to 140 versus 120 in an enhanced older adult population. Multiple endpoints are being assessed, including cardiovascular, renal, and cognitive function.

As of November, 2009, NIH had approved 166 CER submissions at a cost of $341,910,008, ranging from Grand Opportunity (GO) grants for large projects that could be completed within two years, to competitive revisions, administrative supplements, pay-line extensions, and Challenge Grants (RC1 grants of less than $500,000 per year for two years). NIA’s ARRA-funded CER projects totaled 15 (12 challenge grants, 1 GO grant, and 2 supplements), with total funding of $11,697,749. The GO grant takes advantage of the natural experiment in the state of Oregon where residents were randomized by lottery to different insurance plans. This study will assess multiple health behavior consequences of health insurance policy. Of the challenge and GO grants NIA funded, six studies relate to cognitive training, physical exercise, or the two combined. Three studies focus on medical protocol issues. Two studies (including the Oregon lottery GO grant) focus on insurance issues. Two studies relate to study design or infrastructure. Up-to-date information on funded ARRA projects can be found at http://www.nih.gov/recovery/index.htm.

NIA does not currently envision additional focused solicitations for CER projects. However, investigators are invited to initiate submissions on topics that are of interest.

DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS AFFAIRS (VA)

The VA funds research though an intramural program that has funded investigations involving at least 77 of the 100 IOM priority areas. Although VA investigators have university affiliations, all must have a VA appointment of 5/8 or greater and conduct their VA-funded research on the grounds of a VA medical center. Recently completed VA CER studies include comparisons of percutaneous coronary intervention versus (vs.) optimal medical therapy in preventing cardiovascular events7, intensive vs. standard control of glucose levels in diabetics13, on-pump vs. off-pump cardiac surgery14, and robotic-assisted training vs. intensive therapist training vs. usual care for upper extremity rehabilitation in stroke patients (unpublished). The spectrum of CER studies reflects overall VA research priority areas: chronic diseases; diseases of aging; diseases and conditions directly resulting from military service, and genomic medicine.

Each of the VA’s four research services – Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development (BLRD), Clinical Sciences Research and Development (CSRD), Health services Research and Development (HSRD) and Rehabilitation Research and Development (RRD) -- has a portfolio that focuses on specific elements of the research pipeline and has specific requirements. BLRD supports CER on clinical laboratory devices (lab tests) for which results direct specific interventions. CSR&D supports CER using epidemiologic investigations and clinical trials, and is particularly interested in proposals that focus on treatment strategies, rather than on head-to-head comparison of similar interventions; larger studies are carried out through the VA Cooperative Studies Program (CSP), a standing network. HSRD pursues research at the interface of health care systems, patients and health care outcomes, focusing on quality, access, and costs. Much of this work is based on rigorous analysis of VA medical records, with emphasis on the manner in which care is delivered. The RRD program improves the quality of life of impaired and disabled veterans by developing new rehabilitative strategies and assistive technologies.

VA aging research emphasizes care of complex medical conditions (including dementia, sarcopenia and frailty), long-term care and mobility. VA supports research to develop new models of care--acute, preventive, chronic, rehabilitative, and long-term -- and to increase access and improve delivery of health care to older Veterans by testing pathways and protocols for managing multiple, complex chronic conditions, aging syndromes (e.g. frailty, immobility, falls, and cognitive impairment); co-occurring diagnoses within a specific older population (e.g. dementia and hip fractures, nursing home care and congestive heart failure). VA conducts research in a variety of settings including medical centers, residential treatment centers and the home, and addresses problems associated with caregiving, transitions between care settings, and end-of-life issues (e.g. hospice/palliative care and quality of dying). Information on specific funding mechanisms may be found at www.research.va.gov.

Although the VA does not currently envision formal solicitations for CER projects, it will continue to support its clinical trials and HSR&D programs that have long conducted patient outcomes research. Investigators with appropriate VA appointments are encouraged to submit CER proposals of interest through their local VAMC.

SUMMARY

As is evident, AHRQ, VA, and NIA, are each focused on research to enhance the health of the population. The majority of the focus of AHRQ is on CER, while VA and NIA conduct CER studies as a component of the overall research mission. Given the focus of these entities, there are potential opportunities for researchers to initiate studies in keeping with the recommendations of the IOM CER Committee. With the graying of the U.S. population and the resultant extra demands anticipated for the health care system, such studies will be of particular import in the years to come.

Acknowledgments

Sponsor’s role: This manuscript does not have a sponsor beyond the agencies for which each of the authors works.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper.

Author contributions: O’Leary and Bernard conceived and designed this report. O’Leary, Slutsky and Bernard jointly wrote the report, with each author taking responsibility for the section particular to his/her agency, and all authors collaborating on the other sections

References

- 1.National Institutes of Health. Research Reporting On-line Tools (RePORT) [Accessed 3.6.10];Estimates for Funding for Various Research, Conditions, and Disease Categories (RCDC) http://report.nih.gov/rcdc/categories/

- 2.A CBO Paper: Research on the Comparative Effectiveness of Medical Treatments. [Accessed 1.26.10];Congress of the United States Congressional Budget Office. Pub. No. 2975. 2007 December;:3. http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/88xx/doc8891/12-18-ComparativeEffectiveness.pdf.

- 3.US Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed 3.16.10];About FDA: what we do. http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/WhatWeDo/default.htm.

- 4.Code of Federal Regulations. Title 21, part 314-Applications for FDA approval to market a new drug: subpart D-FDA action on applications and abbreviated applications. [Accessed 3.16.10];Section 314.125-Refusal to approve an application. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=314.125.

- 5.Federal Register/Vol. 68, No. 187/Friday, September 26, 2003/Notices. Department of Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Program; Revised Process for Making Medicare National Coverage Determinations

- 6.A CBO Paper: Research on the Comparative Effectiveness of Medical Treatments. [Accessed 1.26.10];Congress of the United States Congressional Budget Office. Pub. No. 2975. 2007 December;:4. http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/88xx/doc8891/12-18-ComparativeEffectiveness.pdf.

- 7.Borden WE, O’Rourke RA, Toe KK, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1503–1516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.IOM (Institute of Medicine) Initial National Priorities for Comparative Effectiveness Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Federal Coordinating Council for Comparative Effectiveness Research. Report to The President and The Congress. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Federal Coordination Committee; Jun 30, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.The ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs. diuretic. The Antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial (ALLHAT) JAMA. 2002;288:2981–2997. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in moderately hypercholesterolemic, hypertensive patients randomized to pravastatin vs. usual care. The Antihypertensive and lipid-lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial (ALLHAT) JAMA. 2002;288:2998–3007. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.2998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type II diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duckworth W, Abraira C, Moritz T, et al. Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:129–139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shroyer AL, Grover FL, Hattler B, et al. On-pump versus off-pump coronary-artery bypass surgery. New Engl J Med. 2009;361:187–1837. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]