Summary

DNA “zip codes” in the promoters of yeast genes confer interaction with the NPC and localization at the nuclear periphery upon activation. Some of these genes exhibit transcriptional memory: after being repressed, they remain at the nuclear periphery for several generations, primed for reactivation. Transcriptional memory requires the histone variant H2A.Z. We find that targeting of active INO1 and recently repressed INO1 to the nuclear periphery is controlled by two distinct and independent mechanisms involving different zip codes and different interactions with the NPC. An 11 base pair Memory Recruitment Sequence (MRS) in the INO1 promoter controls both peripheral targeting and H2A.Z incorporation after repression. In cells lacking either the MRS or the NPC protein Nup100, INO1 transcriptional memory is lost, leading to nucleoplasmic localization after repression and slower reactivation of the gene. Thus, interaction of recently repressed INO1 with the NPC alters its chromatin structure and rate of reactivation.

Introduction

Eukaryotic chromosomes fold and localize in stereotypical ways with respect to each other and with respect to nuclear structures (Cremer et al., 2006). The spatial arrangement of chromosomes correlates with the differentiation status of the cell and the localization of individual genes within the nucleus can impact their expression. Many developmentally regulated genes localize near the nuclear periphery when repressed and move to a more internal, nucleoplasmic location after differentiation (Takizawa et al., 2008). Likewise, the tethering of telomeres to the nuclear envelope promotes the repression of subtelomeric genes (Gasser, 2001; Hediger and Gasser, 2002; Taddei et al., 2004; Taddei et al., 2009). These observations have suggested that the nuclear periphery is a transcriptionally repressive environment. Consistent with this notion, lamin-associated parts of the genome tend to be silenced and artificially tethering DNA to the nuclear lamina is sufficient to cause repression of many neighboring genes (Finlan et al., 2008; Kumaran and Spector, 2008; Reddy et al., 2008). However, localization to the nuclear periphery does not always result in transcriptional repression. A number of genes in yeast relocalize from the nucleoplasm to the nuclear periphery upon activation (Brickner and Walter, 2004; Casolari et al., 2005; Casolari et al., 2004; Sarma et al., 2007; Schmid et al., 2006; Taddei et al., 2006). Therefore, the effects of peripheral localization on transcription are not simple and may be different for different genes or may depend on the targeting mechanism (Akhtar and Gasser, 2007).

We have used the recruitment of active genes to the nuclear periphery in yeast as a model to understand both the mechanisms that control the localization of individual genes and how localization affects gene expression. Genes that localize to the nuclear periphery in yeast physically associate with the nuclear pore complex (NPC; Casolari et al., 2004). We have found that the yeast INO1 gene is targeted to the NPC by two Gene Recruitment Sequences (GRSs) in its promoter (Ahmed et al., 2010). These elements act as “zip codes”; they are sufficient to target the normally nucleoplasmic URA3 locus to the nuclear periphery when integrated nearby (Ahmed et al., 2010). Finally, loss of peripheral targeting leads to defective expression of both INO1 and another GRS-containing gene, TSA2 (Ahmed et al., 2010) in the nucleoplasm, suggesting that interaction of these genes with the NPC promotes their full transcriptional activation.

INO1 is activated by inositol starvation (Greenberg et al., 1982). When cells are shifted to medium lacking inositol, INO1 quickly relocalizes to the nuclear periphery (Brickner et al., 2007; Brickner and Walter, 2004). If inositol is added back, INO1 transcription is rapidly repressed. However, after being repressed, INO1 remains at the nuclear periphery within the population for greater than six hours, or up to four cell divisions (Brickner et al., 2007). In other words, the localization of recently repressed INO1 both reflects the previous transcription of the gene and represents a heritable, epigenetic state. While at the nuclear periphery, INO1 is primed for reactivation (see below). We have termed this phenomenon “transcriptional memory”, defined as the persistent localization of a gene at the nuclear periphery after repression in a primed state that promotes reactivation. Transcriptional memory is not unique to INO1; galactose-regulated genes that are targeted to the nuclear periphery upon activation (such as GAL1) also remain at the nuclear periphery in an H2A.Z-dependent manner for generations after repression (Brickner et al., 2007). In fact, in the case of the GAL genes, the rate of reactivation is much faster than the rate of initial activation (Brickner et al., 2007; Brickner, 2009).

Epigenetic transcriptional memory is associated with increased H2A.Z incorporation at the INO1 promoter (Brickner et al., 2007; Brickner, 2009). H2A.Z is a universally conserved variant of histone H2A that is found in nucleosomes within the promoters of most genes from yeast to plants to humans (Creyghton et al., 2008; Guillemette et al., 2005; Li et al., 2005; Raisner et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2005; Zilberman et al., 2008). Loss of H2A.Z in yeast leads to defects in the activation of certain genes and to loss of boundary activity between transcriptionally silent and non-silent parts of the genome (Meneghini et al., 2003; Raisner and Madhani, 2006). This boundary function has been linked to the NPC; H2A.Z physically interacts with NPC components, loss of NPC components leads to loss of boundary activity (Dilworth et al., 2005; Meneghini et al., 2003) and artificially tethering DNA to the NPC is sufficient to create a boundary (Ishii et al., 2002). H2A.Z also plays an essential role in transcriptional memory. Mutants lacking H2A.Z fail to retain recently repressed INO1 and GAL1 at the nuclear periphery and exhibit a strong defect in their reactivation (Brickner et al., 2007). This role is specific; loss of H2A.Z does not affect the targeting of active INO1 to the nuclear periphery or the rate of its initial activation (Brickner et al., 2007). Thus, the mechanisms of activation and reactivation are different for these genes and peripheral localization after repression promotes reactivation.

To better understand the molecular mechanism of transcriptional memory, we determined the molecular requirements for localization of recently repressed INO1 to the nuclear periphery and H2A.Z incorporation into the INO1 promoter. We find that the previously identified GRS elements do not contribute to the localization of recently repressed INO1 to the nuclear periphery. Instead, a different cis-acting DNA zip code called the Memory Recruitment Sequence (MRS) controls peripheral targeting of recently repressed INO1. The MRS is also necessary and sufficient to induce local H2A.Z incorporation. Furthermore, certain components of the nuclear pore complex are necessary for the peripheral localization of recently repressed INO1 but are not necessary for the peripheral localization of active INO1. One of these proteins, Nup100, plays an essential and specific role in transcriptional memory. Nup100 physically interacts with recently repressed INO1 but not with active INO1. Mutants lacking either the MRS or Nup100 fail to retain INO1 at the nuclear periphery and fail to incorporate H2A.Z into the repressed promoter. This leads to loss of transcriptional memory in nup100Δ mutants; the recently repressed INO1 gene is unable to associate with a poised RNA polymerase II and shows slower reactivation. Thus, the INO1 gene utilizes two independent mechanisms to interact with the NPC, one that promotes the transcriptional output of the active gene and another that primes the recently repressed gene for reactivation.

Results

Distinct mechanisms control targeting of active and recently repressed INO1 to the nuclear periphery

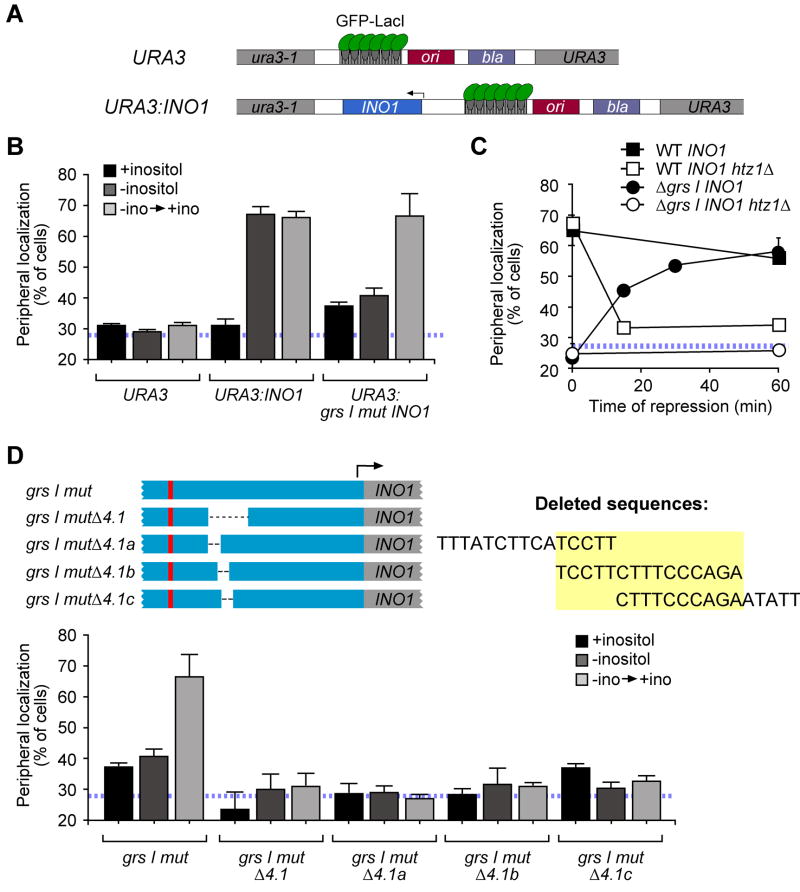

INO1 localizes to the nuclear periphery both when active and for ~6h after being repressed (Brickner et al., 2007; Brickner and Walter, 2004). Two cis-acting DNA zip codes called GRS I and GRS II control the targeting of active INO1 to the nuclear periphery (Ahmed et al., 2010). To dissect the molecular mechanisms controlling INO1 gene localization, we have integrated INO1 at a test site, the URA3 gene, which normally localizes in the nucleoplasm (Figure 1A; (Ahmed et al., 2010). We used this system to ask if localization of recently repressed INO1 to the nuclear periphery was recapitulated when the gene was integrated beside URA3. The INO1 gene (504 base pairs 5′ to 685 base pairs 3′ of the coding sequence) and an array of Lac repressor binding sites were integrated adjacent to URA3 (URA3:INO1; Figure 1A). The GFP-Lac repressor was expressed in this strain and we used immunofluorescence to visualize GFP and the nuclear envelope (marked with Sec63-myc). To quantify the peripheral localization of URA3:INO1, we determined the fraction of the population in which the GFP spot colocalized with the nuclear envelope (Brickner et al., 2010; Brickner and Walter, 2004). The URA3 gene colocalized with the nuclear envelope in 25–30% of cells, which represents the baseline level of peripheral localization in this assay (Figure 1B; indicated as a hatched blue line throughout; (Brickner and Walter, 2004). URA3:INO1 colocalized with the nuclear envelope in ~30% of cells under repressing conditions (Figure 1B; +inositol) and in ~65% of the cells under activating conditions (Figure 1B; −inositol; Ahmed et al., 2010). After 1h of repression, URA3:INO1 remained at the nuclear periphery (Figure 1B; −ino → +ino). Therefore, like the endogenous INO1 gene, URA3:INO1 localized to the nuclear periphery after repression (Brickner et al., 2007; Brickner and Walter, 2004).

Figure 1. Different cis acting DNA elements control peripheral localization of active and recently repressed INO1.

A. Schematic of the lac operator array plasmid, with or without INO1, integrated at URA3. B. Quantitative localization assay of URA3, URA3:INO1 or grs I mutant URA3:INO1. The hatched blue line indicates the baseline for this assay. Cells were grown in the presence or absence of 100μM inositol or switched from medium lacking inositol to medium containing inositol for one hour (−ino → +ino). C. Time course of peripheral localization after repression. The indicated strains were shifted from activating to repressing conditions and cells were harvested and fixed for immunofluorescence and chromatin localization at the indicated times. D. Top panel: left, schematic of INO1 promoter mutants; right, deleted sequences. Bottom panel: peripheral localization from strains having grs I mutant INO1 (data same as in panel B) or grs I mutant INO1 with each of the deletion mutations at URA3.

We next asked if the GRS elements contribute to the retention of INO1 at the nuclear periphery after repression. Because the plasmid used to create URA3:INO1 lacks GRS II, the targeting of active URA3:INO1 to the nuclear periphery is dependent exclusively on the GRS I zip code (Ahmed et al., 2010). Transversion mutations in GRS I (grs I mutant) block targeting of URA3:INO1 to the nuclear periphery in activating conditions (Figure 1B, −inositol; Ahmed et al., 2010). However, after shifting cells from activating to repressing conditions, grs I mutant URA3:INO1 was localized to the nuclear periphery (Figure 1B). Therefore, localization of recently repressed INO1 at the nuclear periphery is not dependent on GRS I (or GRS II, which is absent from URA3:INO1). Furthermore, this result indicates that localization of active INO1 to the nuclear periphery is not a prerequisite for the localization of recently repressed INO1 to the nuclear periphery.

The histone variant H2A.Z is essential for retention of INO1 at the nuclear periphery after repression (Brickner et al., 2007). To test if the targeting of recently repressed URA3:INO1 to the nuclear periphery is also dependent on H2A.Z, we examined the localization of URA3:INO1 with or without the GRS I element (Δgrs in Figure 1C; a 50bp deletion within the promoter, called Δ3 in Ahmed et al., 2010) and with or without H2A.Z (htz1Δ). These four strains were shifted from activating to repressing conditions and the localization of URA3:INO1 was monitored over time. At the beginning of the time course (i.e. activating conditions), wild type URA3:INO1 was localized to the nuclear periphery, whereas grs IΔ mutant URA3:INO1 was localized to the nucleoplasm (Figure 1C). After repression, wild type URA3:INO1 remained at the nuclear periphery in strains with H2A.Z, but not in the htz1Δ mutant (Figure 1C). Finally, grs IΔ mutant URA3:INO1 was recruited from the nucleoplasm to the nuclear periphery after repression, and this targeting required H2A.Z (Figure 1C). Therefore, like the endogenous INO1 gene (Brickner et al., 2007), localization of recently repressed URA3:INO1 to the nuclear periphery required H2A.Z.

A DNA zip code controls peripheral localization of recently repressed INO1

Because targeting of URA3:INO1 to the nuclear periphery after repression was unaffected by loss of the known GRS elements, we hypothesized that additional cis-acting DNA zip codes were responsible for the localization of recently repressed INO1 to the nuclear periphery. Consistent with this hypothesis, loss of either a 50-base pair region (segment 4.1) or smaller, overlapping segments (Δ4.1a–c) of the INO1 promoter resulted in nucleoplasmic localization of grs I mutant URA3:INO1 after repression (Figure 1D). This suggested that the 15-base pair region common to these segments is necessary for localization of recently repressed INO1 to the nuclear periphery (Figure 1D).

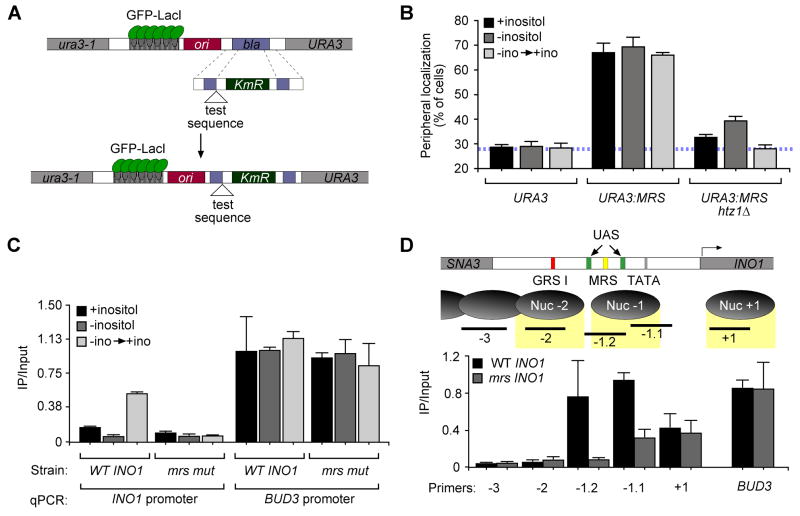

DNA zip codes like GRS I and GRS II are both necessary for targeting of active INO1 to the nuclear periphery and sufficient, in isolation, to target an ectopic locus like URA3 to the nuclear periphery (Ahmed et al., 2010). When removed from the INO1 promoter, GRS I and GRS II function as constitutive targeting elements, suggesting that they are normally negatively regulated (Ahmed et al., 2010). To test if the sequences that were necessary for URA3:INO1 localization to the nuclear periphery after repression functioned as DNA zip codes, we integrated a series of 20-base pair sequences derived from segment 4.1 beside URA3 (integration scheme in Figure 3A). Remarkably, two of the four 20-base pair sequences resulted in relocalization of URA3 to the nuclear periphery under recently repressing conditions but not under activating or long-term repressing conditions (Figure 2A). Thus, the ability of these fragments to function as zip codes was dependent on the previous expression of INO1. This suggests that peripheral targeting can be regulated in trans and is not necessarily an effect of being part of a promoter that was previously expressed (see Discussion). Furthermore, the regulation of targeting was affected by sequences from the INO1 promoter both 5′ and 3′ of the element. However, the 11 base pair element common to these sequences was sufficient to target URA3 to the nuclear periphery regardless of inositol growth conditions (Figure 2A). This suggests that the targeting function and its regulation are separable and that the protein(s) responsible for targeting are present under all of these growth conditions. Thus, this minimal Memory Recruitment Sequence (MRS) functions as a DNA zip code to target an ectopic locus to the nuclear periphery.

Figure 3. The MRS and the histone variant H2A.Z control peripheral targeting of recently repressed INO1.

A. Scheme for integrating DNA elements for localization experiments (Ahmed et al., 2010). B. Peripheral localization of URA3, URA3:MRS and URA3:MRS in the htz1Δ strain. C. Chromatin immunoprecipitation of HA-H2A.Z (Meneghini et al., 2003) from wild type and mrs mutant INO1strains and quantified using primers to amplify −197 to −284 relative to the INO1 ORF or primers to amplify the BUD3 promoter. D. Top panel: map of nucleosomes in the INO1 promoter. Shown are the positions of GRS I (red box), the MRS (yellow box), the TATA box (grey box), two UASINO elements (green boxes) and the PCR products associated with each nucleosome. Bottom panel: ChIP of HA-H2A.Z from either a wild type or mrs mutant INO1 strain, quantified using primers corresponding to the locations in the top panel or the BUD3 promoter.

Figure 2. The MRS is a sequence-specific DNA zip code.

A. The MRS functions as a DNA zip code. Top panel: sequences of inserts tested for peripheral localization when integrated at URA3 using the strategy shown in Figure 3A. Bottom panel: peripheral localization of URA3 (data same as in Figure 1B) or URA3 having each of the indicated DNA fragments integrated nearby. B. Top, schematic of INO1 promoter, indicating relative positions of the grs I mutation (red bar) and the MRS. Bottom panel: peripheral localization of either the grs I mutant (labeled WT; same data as shown in Figure 1B) or the indicated single base pair substitutions within the MRS integrated beside URA3. C. & D. Peripheral localization of mrs mutant INO1 or grs I mrs mutant INO1 integrated at URA3 (C) or at the endogenous INO1 locus (D).

To ask if the targeting function of the MRS is determined by its sequence, we introduced single base pair transversion mutations at ten positions of the MRS within the promoter of grs I mutant URA3:INO1 and tested the localization of these mutants after 1h of repression (Figure 2B). Mutations at positions 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 9 and 10 blocked peripheral targeting after repression (Figure 2B). Mutations at positions 2, 7 and 8 resulted in partial defects in peripheral targeting, while the T5G mutant did not affect localization. Transition mutations at positions 1, 3, 4, 6, 9 and 10, but position 2, also blocked peripheral targeting (Figure 2B). These results indicate that the sequence of the MRS is essential for its function as a DNA zip code.

GRS I and GRS II function are not necessary to target recently repressed INO1 to the nuclear periphery. However, it remained possible that these elements might be sufficient and redundant with the MRS element for targeting of recently repressed INO1, either at URA3 or at the endogenous INO1 locus. To test this possibility, we introduced mutations in the MRS (mrs mutant) either alone, or in combination with the grs I mutation, in the promoter of INO1 and tested these mutants for peripheral targeting at URA3 or the endogenous locus. As expected, mutations in GRS I blocked targeting of active URA3:INO1 but did not block targeting of active endogenous INO1 to the nuclear periphery because of the presence of GRS II (Figure 2C and 2D; Ahmed et al., 2010). Mutation of the MRS alone blocked targeting of recently repressed URA3:INO1 and recently repressed endogenous INO1 (Figure 2C and 2D). Therefore, the MRS is the only cis-acting DNA element governing peripheral localization of recently repressed INO1. Furthermore, if cells were switched from recently repressing conditions to activating conditions again, the URA3:mrs mut INO1 returned to the nuclear periphery, indicating that targeting of active INO1 to the nuclear periphery is independent of targeting of recently repressed INO1 to the nuclear periphery (Figure S1A).

The MRS controls H2A.Z incorporation

H2A.Z is essential for retention of INO1 and GAL1 at the nuclear periphery after repression (I. Cajigas and J.H.B., in prep.; Brickner et al., 2007). Loss of H2A.Z also results in a strong defect in reactivation of INO1 and GAL1 (Brickner et al., 2007). To explore the connection between H2A.Z incorporation and gene localization, we asked if MRS-mediated targeting of URA3 to the nuclear periphery also required H2A.Z. In cells lacking H2A.Z (htz1Δ), URA3:MRS localized in the nucleoplasm (Figure 3B). Therefore, H2A.Z is essential both for peripheral targeting of recently repressed INO1 and for MRS-mediated peripheral targeting of an ectopic locus.

We next used ChIP to determine if the MRS affects H2A.Z incorporation at INO1. As an internal positive control for H2A.Z nucleosomes, we also measured the association of HA-H2A.Z with the BUD3 promoter (Raisner et al., 2005). We observed weak association of H2A.Z with the long-term repressed INO1 promoter and an increased association of H2A.Z with the recently repressed INO1 promoter (Figure 3B; (Brickner et al., 2007). The ChIP signal at INO1 was slightly lower than that at BUD3 (likely due to the primers used for this experiment; see below). However, the association of H2A.Z with the INO1 promoter was MRS-dependent; we did not detect H2A.Z associated with the promoter of mrs mutant INO1 (Figure 3C). Therefore, the MRS is necessary both for targeting of recently repressed INO1 to the nuclear periphery and for H2A.Z incorporation into the INO1 promoter.

Our previous work and genome-wide studies have mapped several nucleosomes within the INO1 promoter (Figure 3D; Brickner et al., 2007; Kaplan et al., 2009; Segal et al., 2006). Relative to the transcriptional start site, one nucleosome is centered ~75 bp downstream (Nuc+1), another is centered ~175 bp upstream (Nuc-1) and another, less well-positioned nucleosome is evident starting ~250 bp upstream (Nuc-2). The MRS element is within sequences protected by Nuc −1 (−201 to −211; yellow box in Figure 3D). Mutations in the MRS element did not alter the position of these nucleosomes (Figure S1B). We performed ChIP against HA-H2A.Z from wild type or mrs mutant INO1 strains and quantified the recovery at positions corresponding to each of these nucleosomes primers within each nucleosome (Figure 3D, top panel). The peak of DNA recovered with HA-H2A.Z from wild type strains was within Nuc-1 and this association was lost from mrs mutant INO1 strains (Figure 3D). This is consistent with the analysis in Figure 3B, in which we used primers slightly upstream of Nuc −1 (INO1prom For/Rev; −197 to −284). DNA associated with Nuc+1 was also weakly associated with HA-H2A.Z, but this was not MRS-dependent. This suggests that, upon repression, the MRS promotes H2A.Z incorporation into a single nucleosome in the INO1 promoter that includes the MRS, one of the upstream activating sequences (UASINO) and the TATA box (Figure 3D).

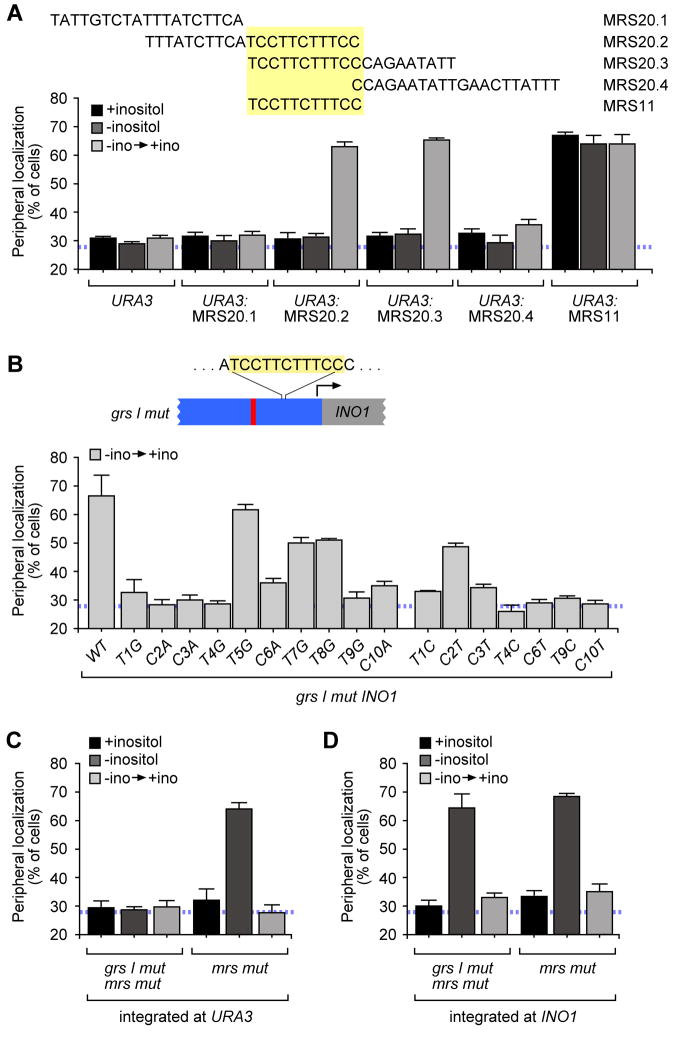

We next asked if the MRS is sufficient to promote H2A.Z incorporation. We used ChIP against HA-H2A.Z in a strain having the MRS element integrated beside URA3 (Figure 4A). H2A.Z immunoprecipitated URA3:MRS but not URA3 (Figure 4B), URA3:mrs mutant (Figure 4C) or URA3:mrsC2A point mutant that was defective for peripheral targeting (Figure 4D). Thus, the defects we observed in localization correlate with the absence of H2A.Z. Furthermore, loss of the catalytic subunit of the ATPase responsible for incorporation of H2A.Z, the Swr1 protein (Mizuguchi et al., 2004), blocked both H2A.Z incorporation (Figure 4C & 4D) and targeting to the nuclear periphery (Figure 4E). Therefore, the MRS is sufficient to promote Swr1-mediated H2A.Z incorporation at an ectopic location.

Figure 4. The MRS is sufficient to induce H2A.Z incorporation.

A. Integration scheme for inserting DNA elements for ChIP experiments (as in Ahmed et al., 2010). B. ChIP of HA-H2A.Z at URA3. The MRS or a control insert were integrated at URA3. Immunoprecipitations were performed with or without 12CA5 mAb against the HA tag. C. ChIP of HA-H2A.Z from URA3:MRS, mrsmut:URA3 or URA3:MRS swr1Δ strains. D. & E. ChIP of HA-H2A.Z (D) or peripheral localization (E) from strains having the MRS (with or without Swr1), the mrs C2A or the Reb1bs integrated at URA3. For panels B–D, immunoprecipitated DNA was quantified relative to input DNA by using real time PCR with primers for both the INO1 promoter and BUD3 promoter.

Peripheral targeting requires both H2A.Z and the MRS

Because H2A.Z incorporation was necessary for MRS-mediated targeting to the nuclear periphery, we next asked if H2A.Z incorporation alone is sufficient to promote targeting to the nuclear periphery. To test this idea, we introduced a different DNA sequence adjacent to URA3 that has previously been shown to promote H2A.Z incorporation (Raisner et al., 2005). The Reb1 binding site along with a poly T sequence (Reb1bs) is sufficient to induce a nucleosome-free region and incorporation of H2A.Z into the flanking nucleosomes (Hartley and Madhani, 2009; Raisner et al., 2005). Indeed, as measured by ChIP, integration of the Reb1bs beside URA3 was sufficient to promote H2A.Z incorporation (Figure 4D). However, URA3:Reb1bs did not localize to the nuclear periphery (Figure 4E). Therefore, incorporation of H2A.Z is not sufficient to control subnuclear localization and targeting of recently repressed INO1 to the nuclear periphery requires a bipartite signal involving both the MRS and H2A.Z.

The MRS is essential for INO1 transcriptional memory

Loss of H2A.Z leads to both a defect in retention of recently repressed INO1 at the nuclear periphery and a defect in the reactivation of INO1 (Brickner et al., 2007). Having identified a second component of a bipartite signal for INO1 targeting to the nuclear periphery, we next asked if the MRS affects reactivation of INO1. We assayed the kinetics of INO1 activation and reactivation in wild type, htz1Δ and mrs mutant strains using RT-qPCR. The rate of activation of INO1 was very similar in the wild type, htz1Δ and mrs mutant INO1 strains (Figure 5A). Therefore, H2A.Z and the MRS element are not involved in INO1 activation (Brickner et al., 2007). Unlike the GAL genes, the reactivation of INO1 is not faster than the initial activation (Brickner et al., 2007). The reactivation occurs after a delay of approximately 90 minutes (Figure 5B). This is likely due to effect of persistent Ino1 enzyme and the recent addition of inositol on the concentration of inositol in cells and the time required for cells to perceive its absence (Brickner et al., 2007). However, the rate at which reactivation occurs is strongly affected by loss of H2A.Z and by mutations in the MRS element, suggesting that these components normally promote INO1 reactivation (Figure 5B). The ultimate steady state levels of INO1, upon activation or reactivation, were indistinguishable between the wild type and mrs mutant INO1 strains (Figure S1C). This indicates that INO1 transcriptional memory affects the rate of transcriptional reactivation and requires both the MRS and H2A.Z.

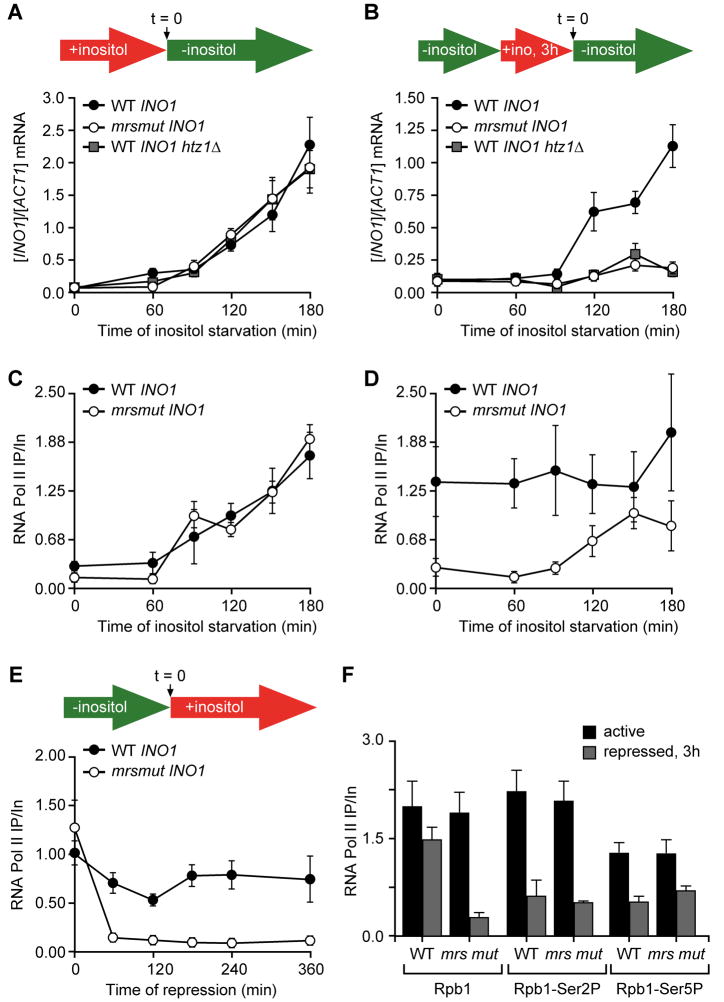

Figure 5. The MRS is required for transcriptional memory.

A. INO1 activation. At time = 0, cells were shifted from repressing medium containing 100μM inositol (red arrow in schematic) to medium without inositol (green arrow in schematic). Cells were harvested at indicated time points and INO1 mRNA levels were quantified relative to ACT1 mRNA levels by RT-qPCR. B. INO1 reactivation. Cells were shifted from activating medium to repressing medium containing 100μM inositol for 3h. At time = 0, cells were harvested and returned to medium without inositol. Cells were harvested at indicated time points and INO1 mRNA levels were quantified relative to ACT1 mRNA levels by RT-qPCR. C. ChIP with anti-Rbp1 antibody at the indicated time points during activation (same scheme as in A). D. ChIP with anti-Rbp1 antibody at the indicated time points during reactivation (same scheme as in B). E. ChIP with anti-Rbp1 antibody (8WG16) from wild type or mrs mut INO1 strains after repression. F. ChIP using anti-Rpb1, anti-phospho Ser2 CTD or anti-phospho Ser5 CTD antibodies from wild type or mrs mut INO1 strains under activating conditions or after 3h of repression.

To assess if MRS-mediated transcriptional memory affects the recruitment of RNA polymerase II to the INO1 promoter, we performed ChIP using a monoclonal antibody against the carboxy terminal domain (CTD) of the large subunit of RNA polymerase II during activation and reactivation of wild type and mrs mut INO1 (Figure 5C and 5D). During activation, we observe no difference in the rate of recruitment of RNA polymerase II to the INO1 promoter between wild type and mrs mutant INO1 (Figure 5C). However, during reactivation, we were surprised to find RNA polymerase II associated with the wild type INO1 promoter at the beginning of the time course (Figure 5D). In contrast, we did not observe RNA polymerase II associated with the mrs mutant INO1 promoter until after ~90 minutes after starving cells for inositol (Figure 5D). This suggested that MRS-mediated transcriptional memory leads to association of RNA polymerase II with the repressed INO1 promoter.

We also monitored RNA polymerase II association with the INO1 promoter after repression. The INO1 gene is repressed very rapidly after addition of inositol (Brickner et al., 2007; Greenberg et al., 1982) and the association of RNA polymerase II with the coding sequence was lost within minutes of adding inositol (Figure S1D). However, RNA polymerase II remained associated with the wild type INO1 promoter for ≥ 6h (3 to 4 generations) after repression (Figure 5E). This is consistent with the duration of transcriptional memory as measured by localization of INO1 at the nuclear periphery after repression (Brickner et al., 2007). In contrast, RNA polymerase II association with the mrs mutant INO1 promoter was lost after repression (Figure 5E). This effect was specific to the INO1 gene; RNA polymerase II did not remain associated with the promoters of two other inositol-repressed genes, OPI3 and CHO2, after repression (Figure S1E).

The RNA polymerase II that was associated with the recently repressed INO1 promoter was not phosphorylated on either Serine 2 or 5 of the CTD (Figure 5F), suggesting that it is not active for transcription. Inactive RNA polymerase II also associates with hundreds of poised promoters during stationary phase in yeast, allowing them to be rapidly induced upon entry into log phase (Radonjic et al., 2005). This suggests that INO1 transcriptional memory promotes reactivation by permitting association of poised RNA polymerase II with the repressed promoter.

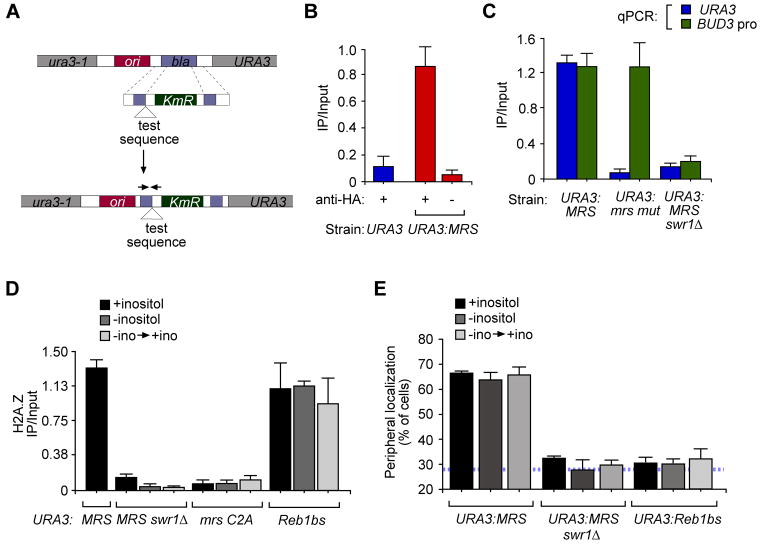

Distinct nuclear pore components control the targeting of active and recently repressed INO1

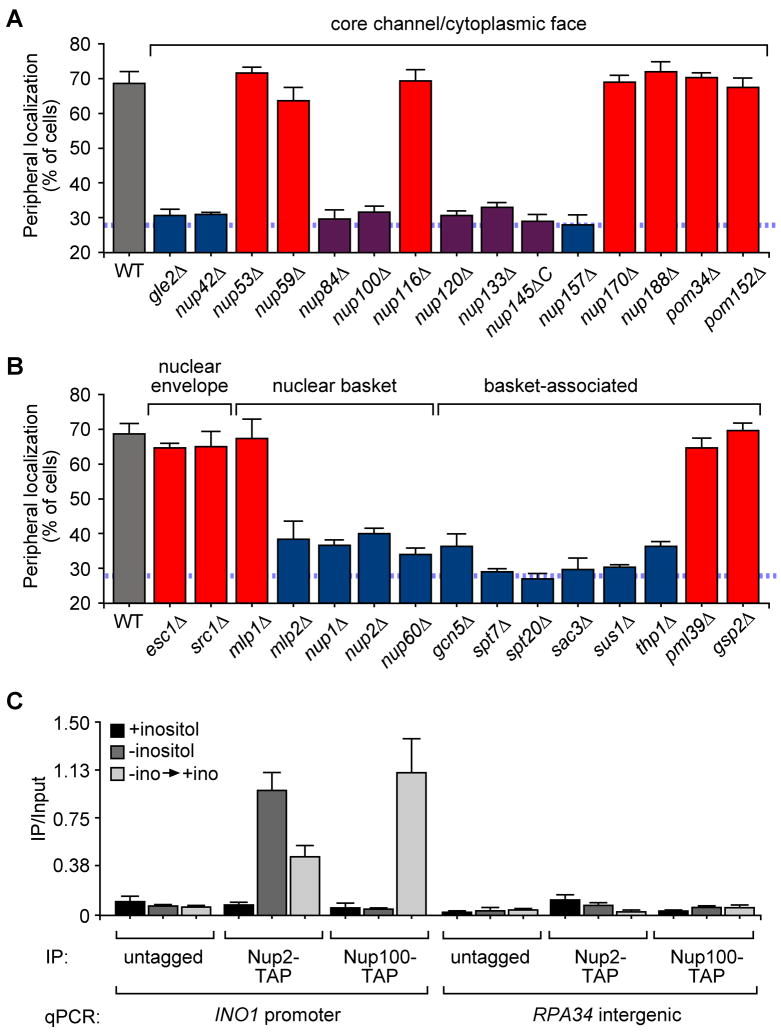

In budding yeast and metazoans, localization of active genes to the nuclear periphery requires NPC components (Ahmed et al., 2010; Brickner et al., 2007; Brown et al., 2008; Cabal et al., 2006; Casolari et al., 2004; Kurshakova et al., 2007; Schmid et al., 2006). To determine if the NPC also plays a role in the localization of recently repressed INO1, we quantified the peripheral localization of recently repressed INO1 in 30 mutant strains lacking different NPC components or associated proteins (Figure 6A and 6B; summarized in Figure S2). These proteins could be grouped into three classes; those that were not required for targeting of either active or recently repressed INO1 (red bars in Figure 6), those that were required for targeting of both active and recently repressed INO1 (blue bars in Figure 6) and those that were specifically required for targeting of recently repressed INO1 (purple bars in Figure 6). Thus, the NPC proteins required for targeting of recently repressed INO1 represent a superset of the proteins required for targeting of active INO1. Proteins required for peripheral targeting of both active and recently repressed INO1 included proteins in the nuclear basket and basket-associated proteins (Figure S2). The five proteins specifically required for peripheral targeting of recently repressed INO1 included all of the members of the Nup84 sub-complex that were tested (Nup84, Nup120, Nup133 and the C terminus of Nup145) as well as Nup100 (Figure S2). This further confirms that GRS-dependent and MRS-dependent targeting to the NPC represent two distinct mechanisms that control localization of INO1 during two distinct phases of its regulation.

Figure 6. NPC proteins required for targeting of active and recently repressed INO1.

A and B. Peripheral localization of recently repressed INO1 in NPC mutant strains. The wild type and mutant strains were grown overnight in medium lacking inositol, inositol was added for 1h and cells were fixed form immunofluorescence. Red bars highlight strains that targeted both active and recently repressed INO1 to the nuclear periphery. Blue bars highlight strains that failed to target both active and recently repressed INO1 to the nuclear periphery. Purple bars highlight strains that targeted active INO1 to the nuclear periphery but failed to target recently repressed INO1 to the nuclear periphery. C. ChIP of TAP-tagged Nup2 or Nup100. Immunoprecipitated DNA was quantified relative to input DNA using real time PCR and primers specific for the INO1 promoter and RPA34 intergenic region (negative control).

Nup100 interacts specifically with recently repressed INO1 and is required for transcriptional memory

A number of NPC components physically interact with active genes by ChIP (Ahmed et al., 2010; Brickner et al., 2007; Casolari et al., 2005; Casolari et al., 2004; Dieppois et al., 2006; Luthra et al., 2007). We used ChIP to monitor the interaction of two NPC components, Nup2 and Nup100, with active and recently repressed INO1. The nucleoplasmic basket protein Nup2, which is required for peripheral targeting of both active and recently repressed INO1, interacted with active INO1 and recently repressed INO1, but not long-term repressed INO1 (Figure 6C; Ahmed et al., 2010). Therefore, both active INO1 and recently repressed INO1 physically interact with nuclear pore components. Nup100, a protein that was specifically required for peripheral localization of recently repressed INO1, gave a robust ChIP interaction only with recently repressed INO1 (Figure 6C). These observations suggest that active and recently repressed INO1 interact differently with the NPC.

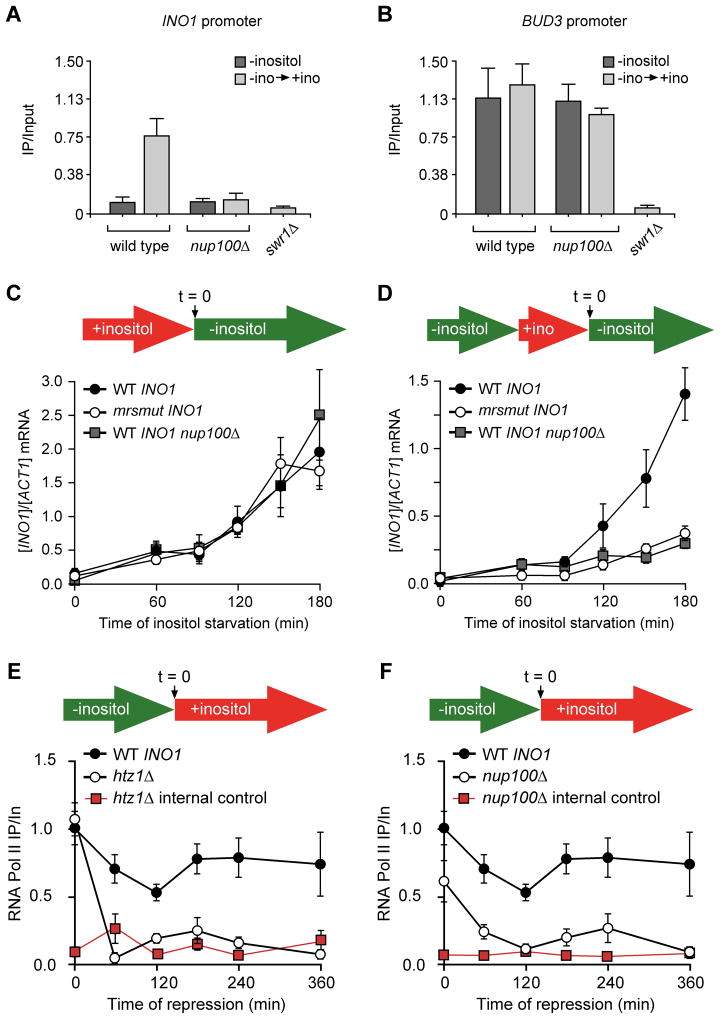

We also tested if Nup100 was required for transcriptional memory. In mutants lacking Nup100, we did not observe H2A.Z incorporation into the INO1 promoter after repression (Figure 7A) or at URA3:MRS (not shown). Incorporation of H2A.Z into the BUD3 promoter was unaffected by loss of Nup100 (Figure 7B). Strains lacking Nup100 activated INO1 at the same rate as wild type strains but showed significantly slower reactivation of INO1 (Figure 7C). Loss of Nup100 did not affect the ultimate steady state expression of INO1 (Figure S1F). Finally, loss of either Nup100 or H2A.Z led to loss of poised RNA polymerase II from the recently repressed INO1 promoter (Figure 7E and 7F). Therefore, the MRS element and Nup100 play essential and specific roles in INO1 transcriptional memory; they promote 1) localization of recently repressed INO1 to the nuclear periphery, 2) H2A.Z incorporation after repression, 3) association of poised RNA polymerase II with the INO1 promoter and 4) rapid reactivation of recently repressed INO1.

Figure 7. Nup100 is essential for INO1 transcriptional memory.

A and B. ChIP of HA-H2A.Z in wild type, nup100Δ and swr1Δ strains grown without inositol or shifted from −inositol to +inositol for one hour before cross-linking and processing for ChIP. Immunoprecipitated DNA was quantified relative to input DNA using primers against the INO1 promoter and the BUD3 promoter. C. Wild type, nup100Δ or mrs mutant INO1 cells were harvested at indicated times after shifting from repressing to activating conditions. INO1 mRNA levels were quantified relative to ACT1 mRNA levels by RT-qPCR. D. After 3h of repression, at time = 0 the strains were shifted back to activating medium and harvested at the indicated times. INO1 mRNA levels were quantified relative to ACT1 mRNA levels by RT-qPCR. E. ChIP with anti-Rbp1 after repression from wild type and htz1Δ strains. F. ChIP with anti-Rbp1 after repression from wild

Discussion

Here we show that the mechanisms controlling the localization and initial induction of a gene can be different from the mechanisms controlling its localization and reactivation after repression. Both active INO1 and recently repressed INO1 localize to the nuclear periphery (Brickner et al., 2007). However, while the targeting of active INO1 to the NPC requires two cis-acting GRS elements (Ahmed et al., 2010), the targeting of recently repressed INO1 to the NPC requires a distinct cis-acting element, the MRS. The targeting mediated by the GRS elements and the MRS elements involves distinct interactions with the NPC. These two targeting mechanisms are independent of each other; peripheral localization of recently repressed INO1 does not depend on prior targeting of active INO1 and vice versa. The MRS element is necessary and sufficient to promote H2A.Z incorporation and requires H2A.Z to function as a DNA zip code. Retention of INO1 at the nuclear periphery, incorporation of H2A.Z after repression and rapid reactivation of INO1 also require the NPC component Nup100. Therefore, these two targeting mechanisms produce different outcomes. Whereas GRS-mediated targeting of active INO1 to the NPC promotes robust transcription (Ahmed et al., 2010), MRS-mediated targeting to the NPC promotes H2A.Z incorporation and RNA polymerase II association, promoting faster reactivation.

The nuclear pore complex and transcription

Recent work in Drosophila suggests that active genes physically interact with NPC proteins like the Nup100 homologue Nup98 (Capelson et al., 2010; Kalverda et al., 2010; Kurshakova et al., 2007; Suntharalingam and Wente, 2003; Vaquerizas et al., 2010). Furthermore, the expression of many genes requires NPC proteins (Capelson et al., 2010; Vaquerizas et al., 2010). The hsp70 locus and the hyperactive X chromosome in males both localize at the nuclear periphery (Kurshakova et al., 2007; Vaquerizas et al., 2010). However, contrary to what has been observed in yeast, some of the interactions of genes with NPC components in Drosophila occur in the nucleoplasm (Capelson et al., 2010; Kalverda et al., 2010; Vaquerizas et al., 2010). This suggests that NPC proteins may have conserved roles in promoting transcription and that this need not always occur at the nuclear periphery. Furthermore, our data indicate that genes can interact with nuclear pore proteins by multiple pathways that influence expression level, chromatin structure and transcriptional kinetics. Therefore, interpreting the correlation between such interactions and gene expression might be more complex than anticipated. Also, because the two pathways we have identified are independent of each other, this raises the possibility that some genes may use either pathway alone. In other words, certain genes may be targeted to the NPC upon activation only, other genes (like INO1) are targeted to the NPC both when active and when recently repressed and yet other genes might be targeted to the NPC only when repressed. Consistent with this idea, we find that many of the genes that are targeted to the nuclear periphery when active return to the nucleoplasm after repression (D.G.B. and J.H.B., unpublished data).

The zip codes that target active and recently repressed INO1 to the NPC confer distinct physical interactions with the NPC. We observed this difference by ChIP: active INO1 interacted robustly with Nup2 but not with Nup100 and recently repressed INO1 interacted with both proteins. Furthermore, a subset of the proteins of the NPC were specifically required for targeting recently repressed INO1 to the nuclear periphery. This raises an important point: although interaction with the NPC correlates with localization to the nuclear periphery, it is possible for a gene (i.e. active INO1) to localize to the nuclear periphery without interacting with certain NPC proteins by ChIP (i.e. Nup100). This also suggests that active INO1 and recently repressed INO1 interact in biochemically distinct complexes with the NPC. We propose that sequence-specific DNA binding proteins interact with these elements in the INO1 promoter and with different parts of the NPC to produce different effects. Alternatively, it is conceivable that active and recently repressed INO1 interact with NPCs of distinct molecular composition.

The mechanism of transcriptional memory

Several genes in yeast exhibit transcriptional memory. In addition to INO1, the GAL genes (GAL1, GAL2, GAL7 and GAL10) remain at the nuclear periphery for up to seven generations after repression, primed for reactivation (Brickner et al., 2007; Kundu et al., 2007). Several mechanistic explanations have been offered for GAL gene memory. As with INO1, loss of H2A.Z causes the GAL genes to lose peripheral localization after repression and leads to a strong defect in reactivation of GAL1 (Cajigas, I. and J.H.B, in prep.; Brickner et al., 2007). The ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler SWI/SNF is also required for rapid reactivation (Kundu et al., 2007). Subsequent work showed that the Gal1 protein itself played an important role in transcriptional memory (Zacharioudakis et al., 2007). Recently, GAL gene transcriptional memory has been linked to the formation of persistent loops between the 5′ and 3′ end of the genes, associated with the NPC (Laine et al., 2009; Tan-Wong et al., 2009). The experimental regimes used in these studies were different and this has raised the possibility that GAL genes utilize more than one type of transcriptional memory (Brickner, 2009, 2010; Kundu and Peterson, 2010). Furthermore, because SWI/SNF (Bryant et al., 2008), H2A.Z (Gligoris et al., 2007) and Gal1 (Zacharioudakis et al., 2007) also promote the activation of the GAL genes, it has been unclear if they have specific roles in memory. This has led some authors to conclude that SWI/SNF and H2A.Z play roles in activation but are not involved in memory (Bryant et al., 2008; Halley et al., 2010). Although this is not the place to explain all of these results, it is clear from our work that INO1 memory is simpler. Loss of a DNA element or a nuclear pore protein that are required for H2A.Z incorporation into the INO1 promoter, like loss of H2A.Z, has a strong and specific effect on reactivation and the binding of RNA Polymerase II to the repressed promoter. Thus, H2A.Z plays an essential and direct role in promoting INO1 transcriptional memory. If the GAL genes utilize multiple, independent forms of transcriptional memory that have some overlap in their duration, then it would be difficult to interpret the effects of mutations using transcription rates alone. Examining mutants for their effects on GAL gene reactivation at various times after repression, GAL gene localization at the nuclear periphery and association of poised RNA polymerase II after repression might clarify the roles of these and other factors in GAL gene memory.

The MRS and Nup100 are required for H2A.Z incorporation into the INO1 promoter after repression, suggesting that targeting of the gene to the NPC promotes incorporation of the histone variant. How does interaction of recently repressed INO1 with the NPC affect H2A.Z incorporation? The functional relationship between the MRS, the NPC and H2A.Z is not a simple, linear genetic pathway. The MRS is necessary and sufficient to promote H2A.Z incorporation. Loss of Nup100 blocks H2A.Z incorporation. However, MRS-mediated targeting to the nuclear periphery also requires H2A.Z and H2A.Z incorporation by itself is not sufficient to induce peripheral localization. We propose that transcriptional memory utilizes a positive feedback system involving a bipartite NPC targeting mechanism requiring both H2A.Z and the MRS. The interaction of the INO1 promoter with the NPC might allow the SWR1 complex to exchange H2A.Z/H2B for H2A/H2B in Nuc-1. H2A.Z nucleosomes and NPC-associated nucleosomes are among the most dynamic nucleosomes in the yeast genome (Dion et al., 2007). Indeed, the nuclease protection conferred by the MRS-dependent H2A.Z nucleosome in the INO1 promoter is less robust in the recently repressed INO1 promoter than in the long-term repressed INO1 promoter (Brickner et al., 2007). Therefore, this nucleosome might be unstable or more rapidly turned over. If so, the disassembly of this nucleosome could allow both NPC interaction and RNA polymerase II association. In this way, NPC targeting could promote H2A.Z incorporation and H2A.Z incorporation could promote retention at the NPC and prime the promoter for reactivation.

One aspect of the transcriptional memory phenomenon that is particularly striking is that the localization of the INO1 and GAL1 genes to the nuclear periphery is maintained within the population for generations after repression (Brickner et al., 2007). Thus, both the gene that was physically transcribed and its descendants are localized to the nuclear periphery and primed for reactivation. How is this transcriptional memory inherited? We envision that targeting of recently repressed INO1 and incorporation of H2A.Z could be controlled by a sequence-specific DNA binding protein whose ability to function at the INO1 promoter is affected by recent growth conditions. Consistent with this idea, 20-base pair fragments from the INO1 promoter, when introduced beside URA3, were targeted to the nuclear periphery only when INO1 has been recently repressed. Incorporation of H2A.Z at URA3 in these strains also occurs only after shifting cells from activating to repressing conditions (Figure S3). This suggests that diffusible factors control targeting and MRS-mediated H2A.Z incorporation in trans. We hypothesize that the localization and chromatin structure of genes that exhibit transcriptional memory are regulated by proteins that are produced during activation but function only on the repressed form of the gene. If so, such proteins might interfere with the normal repression of these genes for a period of time that can extend through multiple generations, depending on their rate of turnover and the critical concentration required for their function. Such a system would then allow cells to more rapidly produce enzymes required to grow under conditions that they have previously encountered.

H2A.Z incorporation

The association of H2A.Z with MRS-containing promoters is significantly higher than the association of H2A.Z with all promoters, based on genome-wide ChIP experiments (P = 0.02 using two tailed t test; Figure S4; Zhang et al., 2005). The MRS element is the second example of a DNA sequence that is sufficient to induce H2A.Z incorporation. The Reb1 binding site and a polyT sequence confer H2A.Z incorporation, when inserted into the coding sequence of the PRM1 gene, through the recruitment of the RSC chromatin remodeler (Hartley and Madhani, 2009; Raisner et al., 2005). We think that the MRS represents a different mechanism for several reasons. First, MRS-mediated incorporation of H2A.Z, both within the INO1 promoter and when the MRS is integrated near URA3 (data not shown), requires Nup100. This is not a generally true of H2A.Z nucleosomes; loss of Nup100 had no effect on the incorporation of H2A.Z in the promoter of the BUD3 gene. Second, unlike the Reb1bs, the MRS behaves as a DNA zip code, targeting URA3 to the nuclear periphery. Third, insertion of the MRS element and the Reb1bs result in distinct patterns of H2A.Z incorporation within the PRM1 coding sequence (Figure S5). Finally, in the context of the INO1 promoter, the MRS promotes incorporation of H2A.Z into a single nucleosome and, unlike the Reb1bs, it does not create an obvious nucleosome-free region (Hartley and Madhani, 2009). Therefore, the interaction of the MRS with the NPC may represent a novel pathway by which H2A.Z incorporation can be controlled to create an altered chromatin state that primes genes for reactivation after repression.

Experimental procedures

Chemicals and Reagents

Unless noted otherwise, chemicals were from Sigma Aldrich, media components were from Q-BIOgene, oligonucleotides were obtained from Operon or Integrated DNA Technologies and restriction enzymes were from New England Biolabs. Fluorescent secondary antibodies, antibodies against GFP, Protein G dynabeads and Pan mouse IgG dynabeads were from Invitrogen. Other antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (anti-myc 9E10), Encore Biotechnology (anti-Nsp1), Covance (anti-Rpb1, 8WG16) and Abcam (anti-CTD Ser2P & anti-CTD Ser5P). The 12CA5 anti-HA antibody was a generous gift from Dr. Robert Lamb.

Chromatin Localization Assay

Chromatin localization was performed as described previously (Brickner and Walter, 2004) and detailed in (Brickner et al., 2010), in the Northwestern University Biological Imaging Facility. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean for three biological replicates of 30–50 cells each. The hatched blue line in Figures 1, 2, 3 & 6 represents the mean peripheral localization of the URA3 gene.

Plasmid Construction

Plasmids pRS306, pRS306-INO1, p6LacO128 and p6LacO128INO1 have been described (Brickner and Walter, 2004). All oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Table S1. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using high-fidelity PCR and mutagenic primers, followed by digestion with DpnI. Transformants were then screened and confirmed by sequencing. Mutant sequences were then cloned into p6LacO128.

Yeast strains

Yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table S2. The integration of test sequences at URA3 was performed as shown in Figure 3A and as described previously (Ahmed et al., 2010). The mrs mutation (or, as a control, wild type INO1) was introduced into the endogenous INO1 promoter by using homologous recombination (Ahmed et al., 2010). The MRS, mrs mutant, mrsC2A mutant and the Reb1bs were introduced within PRM1 using Delitto Perfetto system (Storici et al., 2003).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

ChIP was performed as described (Ahmed et al., 2010). Recovery of the INO1 promoter by ChIP was analyzed using INO1prom For and Rev, except in panel 3D (Table S1). TAP tagged Nup2 and Nup100 were recovered using Pan Mouse IgG Dynabeads. HA-H2A.Z was recovered using 12CA5 anti-HA antibody and Protein G Dynabeads. Error bars represent the S.E.M. from three biological replicates.

Reverse transcriptase real time quantitative PCR

For experiments in which mRNA levels were quantified, RT qPCR was performed as described (Brickner et al., 2007). Error bars represent the S.E.M. of three biological replicates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Lamb for generously providing anti-HA antibody and for sharing his confocal microscope. Also, we thank Rick Gaber, Jonathan Widom and members of the Brickner lab for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM080484 and a W. M. Keck Young Scholar in Medical Research Award.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahmed S, Brickner DG, Light WH, McDonough M, Froyshteter AB, Volpe T, Brickner JH. DNA zip codes control an ancient mechanism for targeting genes to the nuclear periphery. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:111–118. doi: 10.1038/ncb2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar A, Gasser SM. The nuclear envelope and transcriptional control. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:507–517. doi: 10.1038/nrg2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickner DG, Cajigas IC, Fondufe-Mittendorf Y, Ahmed S, Lee PC, Widom J, Brickner JH. H2A.Z-mediated localization of genes at the nuclear periphery confers epigenetic memory of previous transcriptional state. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e81. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickner DG, Light WH, Brickner JH. Quantitative localization of chromosomal loci by immunofluorescence. In: Weissman J, Guthrie C, Fink GR, editors. Methods in Enzymology. Burlington: Academic Press; 2010. pp. 569–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickner JH. Transcriptional memory at the nuclear periphery. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickner JH. Transcriptional memory: staying in the loop. Curr Biol. 2010;20:R20–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickner JH, Walter P. Gene recruitment of the activated INO1 locus to the nuclear membrane. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CR, Kennedy CJ, Delmar VA, Forbes DJ, Silver PA. Global histone acetylation induces functional genomic reorganization at mammalian nuclear pore complexes. Genes Dev. 2008;22:627–639. doi: 10.1101/gad.1632708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant GO, Prabhu V, Floer M, Wang X, Spagna D, Schreiber D, Ptashne M. Activator control of nucleosome occupancy in activation and repression of transcription. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:2928–2939. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabal GG, Genovesio A, Rodriguez-Navarro S, Zimmer C, Gadal O, Lesne A, Buc H, Feuerbach-Fournier F, Olivo-Marin JC, Hurt EC, Nehrbass U. SAGA interacting factors confine sub-diffusion of transcribed genes to the nuclear envelope. Nature. 2006;441:770–773. doi: 10.1038/nature04752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capelson M, Liang Y, Schulte R, Mair W, Wagner U, Hetzer MW. Chromatin-bound nuclear pore components regulate gene expression in higher eukaryotes. Cell. 2010;140:372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casolari JM, Brown CR, Drubin DA, Rando OJ, Silver PA. Developmentally induced changes in transcriptional program alter spatial organization across chromosomes. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1188–1198. doi: 10.1101/gad.1307205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casolari JM, Brown CR, Komili S, West J, Hieronymus H, Silver PA. Genome-wide localization of the nuclear transport machinery couples transcriptional status and nuclear organization. Cell. 2004;117:427–439. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00448-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremer T, Cremer M, Dietzel S, Muller S, Solovei I, Fakan S. Chromosome territories--a functional nuclear landscape. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creyghton MP, Markoulaki S, Levine SS, Hanna J, Lodato MA, Sha K, Young RA, Jaenisch R, Boyer LA. H2AZ is enriched at polycomb complex target genes in ES cells and is necessary for lineage commitment. Cell. 2008;135:649–661. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieppois G, Iglesias N, Stutz F. Cotranscriptional recruitment to the mRNA export receptor Mex67p contributes to nuclear pore anchoring of activated genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:7858–7870. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00870-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth DJ, Tackett AJ, Rogers RS, Yi EC, Christmas RH, Smith JJ, Siegel AF, Chait BT, Wozniak RW, Aitchison JD. The mobile nucleoporin Nup2p and chromatin-bound Prp20p function in endogenous NPC-mediated transcriptional control. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:955–965. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dion MF, Kaplan T, Kim M, Buratowski S, Friedman N, Rando OJ. Dynamics of replication-independent histone turnover in budding yeast. Science. 2007;315:1405–1408. doi: 10.1126/science.1134053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlan LE, Sproul D, Thomson I, Boyle S, Kerr E, Perry P, Ylstra B, Chubb JR, Bickmore WA. Recruitment to the nuclear periphery can alter expression of genes in human cells. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser SM. Positions of potential: nuclear organization and gene expression. Cell. 2001;104:639–642. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00259-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gligoris T, Thireos G, Tzamarias D. The Tup1 corepressor directs Htz1 deposition at a specific promoter nucleosome marking the GAL1 gene for rapid activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:4198–4205. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00238-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg ML, Reiner B, Henry SA. Regulatory mutations of inositol biosynthesis in yeast: isolation of inositol-excreting mutants. Genetics. 1982;100:19–33. doi: 10.1093/genetics/100.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemette B, Bataille AR, Gevry N, Adam M, Blanchette M, Robert F, Gaudreau L. Variant histone H2A.Z is globally localized to the promoters of inactive yeast genes and regulates nucleosome positioning. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halley JE, Kaplan T, Wang AY, Kobor MS, Rine J. Roles for H2A.Z and Its Acetylation in GAL1 Transcription and Gene Induction, but Not GAL1-Transcriptional Memory. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley PD, Madhani HD. Mechanisms that specify promoter nucleosome location and identity. Cell. 2009;137:445–458. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hediger F, Gasser SM. Nuclear organization and silencing: putting things in their place. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:E53–55. doi: 10.1038/ncb0302-e53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii K, Arib G, Lin C, Van Houwe G, Laemmli UK. Chromatin boundaries in budding yeast: the nuclear pore connection. Cell. 2002;109:551–562. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00756-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalverda B, Pickersgill H, Shloma VV, Fornerod M. Nucleoporins directly stimulate expression of developmental and cell-cycle genes inside the nucleoplasm. Cell. 2010;140:360–371. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan N, Moore IK, Fondufe-Mittendorf Y, Gossett AJ, Tillo D, Field Y, LeProust EM, Hughes TR, Lieb JD, Widom J, Segal E. The DNA-encoded nucleosome organization of a eukaryotic genome. Nature. 2009;458:362–366. doi: 10.1038/nature07667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaran RI, Spector DL. A genetic locus targeted to the nuclear periphery in living cells maintains its transcriptional competence. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:51–65. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200706060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu S, Horn PJ, Peterson CL. SWI/SNF is required for transcriptional memory at the yeast GAL gene cluster. Genes Dev. 2007;21:997–1004. doi: 10.1101/gad.1506607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu S, Peterson CL. Dominant role for signal transduction in the transcriptional memory of yeast GAL genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:2330–2340. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01675-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurshakova MM, Krasnov AN, Kopytova DV, Shidlovskii YV, Nikolenko JV, Nabirochkina EN, Spehner D, Schultz P, Tora L, Georgieva SG. SAGA and a novel Drosophila export complex anchor efficient transcription and mRNA export to NPC. Embo J. 2007;26:4956–4965. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laine JP, Singh BN, Krishnamurthy S, Hampsey M. A physiological role for gene loops in yeast. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2604–2609. doi: 10.1101/gad.1823609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Pattenden SG, Lee D, Gutierrez J, Chen J, Seidel C, Gerton J, Workman JL. Preferential occupancy of histone variant H2AZ at inactive promoters influences local histone modifications and chromatin remodeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18385–18390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507975102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthra R, Kerr SC, Harreman MT, Apponi LH, Fasken MB, Ramineni S, Chaurasia S, Valentini SR, Corbett AH. Actively transcribed GAL genes can be physically linked to the nuclear pore by the SAGA chromatin modifying complex. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:3042–3049. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608741200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meneghini MD, Wu M, Madhani HD. Conserved histone variant H2A.Z protects euchromatin from the ectopic spread of silent heterochromatin. Cell. 2003;112:725–736. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00123-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuguchi G, Shen X, Landry J, Wu WH, Sen S, Wu C. ATP-driven exchange of histone H2AZ variant catalyzed by SWR1 chromatin remodeling complex. Science. 2004;303:343–348. doi: 10.1126/science.1090701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radonjic M, Andrau JC, Lijnzaad P, Kemmeren P, Kockelkorn TT, van Leenen D, van Berkum NL, Holstege FC. Genome-wide analyses reveal RNA polymerase II located upstream of genes poised for rapid response upon S. cerevisiae stationary phase exit. Mol Cell. 2005;18:171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raisner RM, Hartley PD, Meneghini MD, Bao MZ, Liu CL, Schreiber SL, Rando OJ, Madhani HD. Histone variant H2A.Z marks the 5′ ends of both active and inactive genes in euchromatin. Cell. 2005;123:233–248. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raisner RM, Madhani HD. Patterning chromatin: form and function for H2A.Z variant nucleosomes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy KL, Zullo JM, Bertolino E, Singh H. Transcriptional repression mediated by repositioning of genes to the nuclear lamina. Nature. 2008;452:243–247. doi: 10.1038/nature06727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarma NJ, Haley TM, Barbara KE, Buford TD, Willis KA, Santangelo GM. Glucose-responsive regulators of gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae function at the nuclear periphery via a reverse recruitment mechanism. Genetics. 2007;175:1127–1135. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.068932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M, Arib G, Laemmli C, Nishikawa J, Durussel T, Laemmli UK. Nup-PI: the nucleopore-promoter interaction of genes in yeast. Mol Cell. 2006;21:379–391. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal E, Fondufe-Mittendorf Y, Chen L, Thastrom A, Field Y, Moore IK, Wang JP, Widom J. A genomic code for nucleosome positioning. Nature. 2006;442:772–778. doi: 10.1038/nature04979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storici F, Durham CL, Gordenin DA, Resnick MA. Chromosomal site-specific double-strand breaks are efficiently targeted for repair by oligonucleotides in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14994–14999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036296100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suntharalingam M, Wente SR. Peering through the pore: nuclear pore complex structure, assembly, and function. Dev Cell. 2003;4:775–789. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00162-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei A, Hediger F, Neumann FR, Bauer C, Gasser SM. Separation of silencing from perinuclear anchoring functions in yeast Ku80, Sir4 and Esc1 proteins. Embo J. 2004;23:1301–1312. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei A, Van Houwe G, Hediger F, Kalck V, Cubizolles F, Schober H, Gasser SM. Nuclear pore association confers optimal expression levels for an inducible yeast gene. Nature. 2006;441:774–778. doi: 10.1038/nature04845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei A, Van Houwe G, Nagai S, Erb I, van Nimwegen E, Gasser SM. The functional importance of telomere clustering: global changes in gene expression result from SIR factor dispersion. Genome Res. 2009;19:611–625. doi: 10.1101/gr.083881.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takizawa T, Meaburn KJ, Misteli T. The meaning of gene positioning. Cell. 2008;135:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan-Wong SM, Wijayatilake HD, Proudfoot NJ. Gene loops function to maintain transcriptional memory through interaction with the nuclear pore complex. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2610–2624. doi: 10.1101/gad.1823209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaquerizas JM, Suyama R, Kind J, Miura K, Luscombe NM, Akhtar A. Nuclear pore proteins nup153 and megator define transcriptionally active regions in the Drosophila genome. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000846. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharioudakis I, Gligoris T, Tzamarias D. A yeast catabolic enzyme controls transcriptional memory. Curr Biol. 2007;17:2041–2046. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Roberts DN, Cairns BR. Genome-wide dynamics of Htz1, a histone H2A variant that poises repressed/basal promoters for activation through histone loss. Cell. 2005;123:219–231. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilberman D, Coleman-Derr D, Ballinger T, Henikoff S. Histone H2A.Z and DNA methylation are mutually antagonistic chromatin marks. Nature. 2008;456:125–129. doi: 10.1038/nature07324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.