Abstract

The global burden of metabolic disease demands that we develop new therapeutic strategies. Many of these approaches may center on manipulating the behavior of adipocytes, which contribute directly and indirectly to a host of disease processes including obesity and type 2 diabetes. One way to achieve this goal will be to alter key transcriptional pathways in fat cells, such as those regulating glucose uptake, lipid handling, or adipokine secretion. In this review we look at what is known about how adipocytes govern their physiology at the gene expression level, and we discuss novel ways that we can accelerate our understanding of this area.

1. Introduction

We have experienced an enormous increase in the prevalence of obesity and its attendant metabolic complications, including Type 2 diabetes (T2DM), dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease. Once a problem solely of wealthy nations, obesity has spread from the developed to the developing world, and for the first time in human history overnutrition has surpassed undernutrition as a global cause of morbidity and mortality1. Even our children are not immune, as >40% of U.S. children are now considered overweight or obese2. This situation has provoked intense study of all aspects of metabolism, including adipocyte biology.

Adipose tissue has long been recognized as a site for storage of excess energy derived from food intake. During fasting, adipocytes release energy in the form of fatty acids for other organs to consume. However, the discovery of leptin in 19943 suggested that adipose tissue could also function as an endocrine organ, and there are now thousands of publications that demonstrate important physiological roles for a wide variety of adipocyte-derived products4-7. These substances, often collectively referred to as adipocytokines, include leptin, adiponectin, retinol binding protein 4 (RBP4), in addition to several other factors. Not all of these factors are proteins; a recent study identifies the lipid palmitoleate as a ‘lipokine’ that shares some of the functional properties of the classic adipose-derived peptide hormones, and may be the prototype for more lipid-derived mediators yet to be discovered8. These adipokines exert a variety of effects on many aspects of nutrient homeostasis, including appetite, satiety, fatty acid oxidation, and glucose uptake. In addition, adipocytes secrete hormones that regulate non-metabolic processes such as immune function, blood pressure, bone density, reproduction, and hemostasis.

Given the important role played by adipocytes in the regulation of systemic energy balance and nutrient homeostasis, it is reasonable to imagine that these cells might be therapeutic targets for metabolic diseases. In fact, the antidiabetic thiazolidinedione (TZD) drugs provide proof-of-concept for such an approach. TZDs exert their beneficial effects on hyperglycemia and insulin resistance by activating a specific transcription factor, the nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ)9. There is debate about which cell acts as primary mediator of the antidiabetic effects of TZDs, but it seems clear that PPARγ in adipocytes account for at least part of their actions. PPARγ is a master regulator of adipogenesis and adipocyte biology, and virtually all aspects of adipose metabolism are affected directly or indirectly by TZDs. These agents improve adiponectin secretion, promote lipogenesis, block lipolysis, and enhance insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. In fact, genome-wide location analysis of PPARγ in mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes identifies binding sites near an extremely large number of metabolically relevant genes10, 11.

While TZDs have been an important addition to our armamentarium for metabolic disease, they are not always highly effective. Furthermore, they can induce adverse effects such as edema and coronary events in some cases12. This indicates that additional options are needed for therapy; at least part of the reason that we don’t have such options is that we don’t fully understand the transcriptional pathways that fat cells use to control their metabolic actions.

An important point that needs to be mentioned: the goal is not to prevent adipogenesis, to enhance fat cell apoptosis, or to otherwise reduce fat cell number. Adipocytes serve as a safe place to store excess calories. Animals and humans who have a reduced ability to make fat cells are lipodystrophic, and they suffer from a range of undesirable effects including ectopic lipid deposition in muscle and liver, severe insulin resistance, and cirrhosis13. We need our fat cells. The goal is to manipulate adipocytes in selective ways that promote health.

In this review, we will look at some of the major metabolic functions of fat cells, with an emphasis on the transcriptional pathways that regulate these processes. We will then discuss newer strategies that are being brought to bear on this issue, which we believe will result in a broader understanding of how adipocytes regulate their own behavior, and may ultimately provide novel targets for drug therapy.

2. Key Functional Pathways in Adipocytes

Fat cells perform a wide array of functions that affect systemic metabolism. In this section, we review the major pathways that regulate these functions with emphasis on what is known about the transcriptional regulation of key genes within those pathways.

2.1. Adipogenesis

Adipogenesis, or the formation of new fat cells, is not really a physiological function in the strict sense of the term, but it is worth reviewing briefly because most of the key adipogenic transcription factors also play important roles in the functions of mature adipocytes. PPARγ, C/EBPα, KLFs, and other pro-and anti-adipogenic transcription factors (discussed below) are not simply required for initiating and regulating the transcriptional cascade that regulates the development of new fat cells. These same factors regulate the expression of key metabolic enzymes, signaling components, and adipocytokines in the mature fat cell, and thus maintain the differentiated state by enabling the full range of functions performed by fat cells.

It is worth making the point, however, that adipogenesis per se does not contribute to obesity, except in the most literal sense that one cannot be obese without differentiated fat cells. However, obesity cannot be caused by excessive adipogenesis. This is because obesity represents an excess of stored calories, which results from an imbalance between energy taken in and energy burned. This simple restatement of the First Law of Thermodynamics makes it clear that simply making more fat cells does not cause excess adiposity; a theoretical doubling of fat cell number without concomitant changes in food intake or energy expenditure would result in a fat pad containing twice as many cells of half the size.

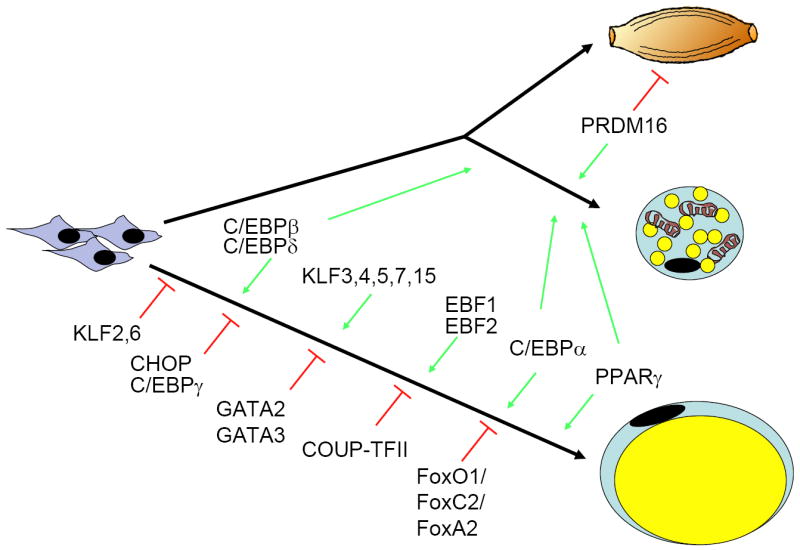

Adipocyte differentiation is regulated by a few key signaling pathways that exert their actions on a cascade of transcription factors. Pro-adipogenic extracellular signals include insulin and FGF, while the Wnt and hedgehog pathways are anti-adipogenic. Detailed reviews of the adipogenic transcriptional cascade have been recently published14-16, but we will review a few critical players here.

2.1.1. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ)

The nuclear hormone receptor PPARγ (NR1C3) is as close to a master regulator of adipogenesis as we are likely to discover. Virtually all known activators and inhibitors of adipogenesis act at least in part by regulating the expression or activity of PPARγ, and cells that lack PPARγ cannot be converted into adipocytes even when other powerfully pro-adipogenic factors are ectopically expressed. For example, overexpression of C/EBPα or EBF1 cannot compensate for the absence of PPARγ in PPARγ-/- fibroblasts17, 18. PPARγ is the only transcription factor that is absolutely necessary and sufficient for adipogenesis19-22.

In cultured cell models of adipogenesis, PPARγ mRNA is directly induced by factors that act early in the cascade, such as C/EBPβ, C/EBPδ, EBF1, and KLF5. Conversely, early repressors of adipogenesis such as GATA2, KLF2, and CHOP act in part by reducing PPARγ expression. Other factors, such as SREBP1c and the enzyme XOR may act to increase PPARγ activity (as opposed to actual mRNA or protein levels), perhaps by regulating production of a still elusive endogenous ligand23-25. PPARγ itself induces the expression of transcription factors that induce genes of terminal differentiation, including lipid handling enzymes and other mediators of adipocyte physiology. Additionally, PPARγ itself directly binds to regulatory regions flanking the majority of these same genes, in a classic example of a ‘feed-forward’ loop.

The study of PPARγ in vivo has been hampered somewhat by the confounding fact that this protein is required for normal placentation; PPARγ-/- embryos thus die relatively early in embryogenesis19, 20. Nonetheless, a requirement for PPARγ in adipogenesis in vivo has been ascertained from several studies involving chimeric animals, or mice in which placentation was rescued using tetraploid aggregation19, 21. Furthermore, humans with dominant negative mutations in PPARγ suffer from lipodystrophy26, confirming a role for this factor in our own species as well.

There are two major isoforms of PPARγ, designated PPARγ1 and PPARγ2, which are formed by alternative promoter and first exon usage. Both proteins are induced during adipocyte differentiation, though PPARγ2 appears to be more adipose-specific. There are conflicting data on the relative importance of these two isoforms. Selective knockdown of PPARγ1 and PPARγ2 promoters using engineered zinc finger proteins suggested that only PPARγ2 can induce adipogenesis27, yet others showed that both isoforms are more or less equal in their ability to induce adipogenesis in PPARγ-/- MEFs28. The story is no clearer in vivo, as one study of PPARγ2 selective knockout mice showed decreased fat mass with impaired adipogenesis while another study found normal adiposity29, 30.

2.1.2. CCAAT-enhancer-binding proteins (C/EBPs)

Multiple members of the bZIP family of CCAAT-enhancer-binding proteins (C/EBPs) are involved in adipogenesis. C/EBPβ, C/EBPδ, and C/EBPα are all pro-adipogenic, while C/EBPγ and CHOP repress differentiation31. C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ are expressed at very early stages of differentiation, and together they induce expression of both C/EBPα and PPARγ. C/EBPα and PPARγ have an important synergistic relationship. First, they induce each other’s expression in a mutually reinforcing positive feedback loop that maintains the differentiated state. In addition, both factors bind to a highly overlapping complement of target genes at locations often quite close to one another10, 11. C/EBPα is therefore of particular importance in adipogenesis and adipocyte physiology. Nonetheless, it remains true that PPARγ can promote differentiation in the absence of C/EBPα (although the resulting adipocytes are insulin resistant; see below)32, but the converse is not true18.

2.1.3. Krüppel-like factors (KLFs)

The Krüppel-like factors (KLFs) are a large family of Cys2/His2 zinc finger DNA-binding proteins related to the Drosophila melanogaster segmentation gene product, Krüppel. KLFs are important regulators of erythropoiesis, T cell activation, vascular development, lung development, and skin development. Many KLF proteins are expressed in adipose tissues, and they show a wide variety of expression profiles during adipocyte differentiation. In keeping with this, several KLFs have been shown to play an active role in adipogenesis. These include KLF2 and KLF7, which negatively regulate adipogenesis33, 34. On the other hand, KLF3, KLF4, KLF5, KLF6, and KLF15 all promote adipogenesis to one degree or another35-39. One intriguing feature of the relationship between KLFs and adipocyte differentiation is the transitional nature of the expression of each factor. Some factors, like KLF4, act early in the transcriptional cascade, while KLF15 is induced quite late. KLF5 occupies an intermediate position in the cascade, after C/EBPβ and C/EBPδ induction but prior to PPARγ. Target genes for the KLFs in adipocytes are not clearly defined, although KLF15 is known to activate Glut4 directly40, and KLF5 induces PPARγ 36. Much remains to be discovered about the role of KLF action in adipocyte biology.

2.1.4. Early B cell factors (EBFs)

Early B cell factors (EBFs) are atypical helix-loop-helix factors important for the control of B lymphocyte specific genes and for the transcriptional regulation of genes in olfactory receptor neurons. Mammals have four EBF proteins encoded by distinct genes, designated EBF1-4. EBF1, 2 and 3 are expressed in adipose tissue, with increasing levels seen as differentiation progresses. EBF1 stimulates adipogenesis in NIH-3T3 fibroblasts, and expression of a dominant-negative EBF-fusion protein blocks 3T3-L1 differentiation41. Knockdown experiments showed that EBF1 and EBF2 are required for adipogenesis17. C/EBPα and PPARγ have been showed to be direct EBF targets17, but similar to KLFs, we still lack a comprehensive understanding of their target genes.

2.1.5. GATA factors

GATA transcriptional factors play important roles in a variety of developmental processes. GATA2 and GATA3 are specially expressed in mouse preadipocytes, and the expression and GATA2 and GATA3 decrease during adipogenesis42. Overexpression of GATA2 and GATA3 in preadipocytes inhibits terminal differentiation into mature adipocytes. GATA3-deficient embryonic stem cells have enhanced adipogenic capacity. These effects are mediated through the direct suppression of PPARγ expression as well as via inhibition of C/EBPα through protein-protein interactions42, 43.

2.1.6. Forkhead proteins

Several members of the forkhead family of winged helix proteins are expressed in adipose tissue, and many have been shown to have significant effects on adipogenesis and adipose physiology. The FoxO proteins FoxO1, FoxO3a, and FoxO4 are all induced during adipogenesis, although forced expression of FoxO1 inhibits the process; conversely, a dominant negative FoxO1 promotes differentiation44. Overexpression of the same dominant negative protein in adipose tissue in vivo causes the formation of smaller adipocytes associated with enhanced glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity45. FoxA2 is also expressed in adipose tissue, and this is dramatically enhanced by high-fat feeding. FoxA2 has divergent effects on differentiation, which it inhibits, and on metabolism in mature adipocytes46. Expression of FoxA2 in mature cells induces Glut4, HSL, and other adipocyte-specific genes. FoxC2 is another interesting family member. When expressed in preadipocytes, FoxC2 blocks differentiation47, 48, but in mature cells FoxC2 overexpression sensitizes adipocytes to β-adrenergic signaling, thus promoting lipolysis and leanness49.

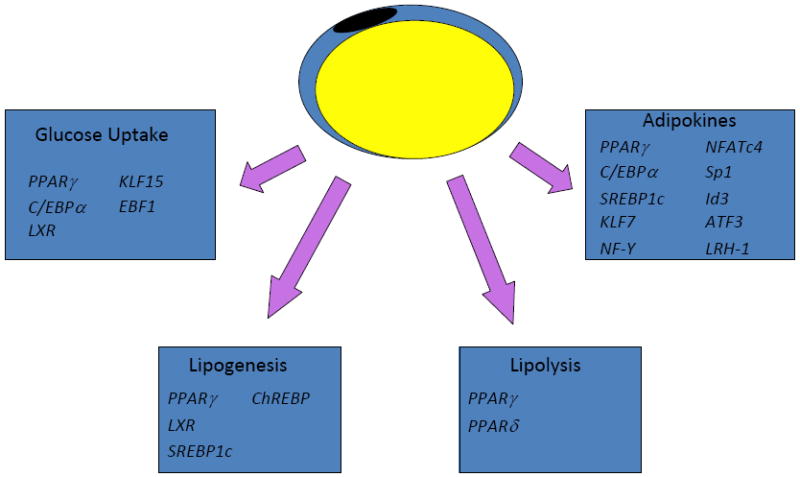

2.2. Lipogenesis

Lipogenesis refers to the process by which fatty acids are synthesized de novo and the subsequent esterification of fatty acids into triglycerides. Fatty acids can also be imported into fat cells from the circulation to be used as substrate for triglyceride accumulation, and for the sake of simplicity we consider the process of fatty acid transport to be part of the overall lipogenic pathway. Lipogenesis is often confused with adipogenesis because lipid accumulation is often used as a marker of fat cell differentiation. Nevertheless, it is important to make the distinction as one can see lipid deposition in cells without concomitant expression of other genes that mark adipocytes. Conversely, it is possible to promote adipogenesis without allowing lipid accumulation, for example, by limiting the supply of biotin (which acts as an essential cofactor of the rate-limiting enzyme of lipogenesis, acetyl CoA carboxylase). Species differences can also be important. In humans, de novo lipogenesis occurs primarily in the liver, with a relatively small contribution from adipose tissue. Rodents, however, generate a higher percentage of lipid directly in adipose tissue50.

Lipogenesis in adipocytes is activated by a high carbohydrate supply and by the actions of insulin51. The biosynthesis of fatty acids involves acetyl-CoA transport across the inner mitochondrial membrane into cytoplasm followed by conversion to malonyl-CoA by the multifunctional polypeptide acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC). Then the fatty acid synthase (FAS) complex performs a series of enzymatic reactions that generates C16 palmitate. Longer chains are synthesized and double bonds are introduced by a variety of microsomal enzymes. Fatty acids thus produced are incorporated into triglycerides by a series of reactions catalyzed by enzymes such as glycerol 3-phosphate acyltransferase (GPAT) and several isoforms of acyl-CoA:1-acylglycerol-sn-3-phosphate acyltransferase (AGPAT), diacylglycerol:acyl-CoA acyltransferase (DGAT) and others. Fatty acids can also be imported into adipocytes from the plasma using both passive mechanisms as well as via protein carriers called fatty acid transport proteins (FATPs).

Adipocyte lipogenesis is regulated by the nutritional environment. In general, feeding promotes lipogenesis, and fasting reduces it. Glucose and insulin both promote lipid formation, while polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) repress lipogenesis.

2.2.1. Sterol regulatory element binding proteins (SREBPs)

A number of studies have shown that lipogenesis is mediated in part by a transcription factor called sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c (SREBP1c; also known as adipocyte determination and differentiation factor 1 (ADD1)). SREBPs belong to the basic helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper class of transcription factors, and are represented by three isoforms: SREBP-1a, SREBP-1c and SREBP-2. SREBP-1c is the form most highly expressed in adipocytes, and plays an important role in the control of genes involved in the biosynthesis of fatty acids, such as fatty acid synthase. Specifically, studies in vitro have identified SREBP1c as an important mediator of the effect of insulin on de novo lipid synthesis52. Surprisingly, the study of SREBP-1c knockout mice showed normal fat mass, and no alteration of lipogenic gene expression53. These results suggest that SREBP1c may be more important for nutritional changes in lipid synthesis, as compared to basal lipid synthesis. Furthermore, massive overexpression of SREBP-1c under the control of aP2-promoter induces severe lipodystrophy54; these discrepancies remain unresolved.

2.2.2. PPARγ

PPARγ was discussed earlier as a key regulator of adipocyte differentiation, and as mentioned, it also plays an important role in the maintenance of the differentiated state. This includes the expression of lipogenic genes, and PPARγ binding sites have been discovered in the flanking sequence of a large number of lipogenic enzymes and regulators10, 11. This includes proteins involved in lipid transport and intracellular shuttling, such as FABPs and FATPs. Consistent with this, TZDs promote lipid accumulation in mature adipocytes.

2.2.3. Liver X receptor (LXR)

LXRs are nuclear hormone receptors that affect cholesterol metabolism and lipid biosynthesis. There are two LXR genes that encode the factors LXRα and LXRβ. LXRα is expressed in liver, spleen, kidney, small intestine and adipose tissue, while LXRβ is more widely expressed. LXR agonists increase lipid accumulation in fat55, and LXRα/β null mice have exhibit reduced lipid accumulation56.

2.2.4. Carbohydrate response element binding protein (ChREBP)

ChREBP is another member of the basic helix-loop-helix family of transcription factors. Originally discovered as a sucrose-responsive factor that promotes lipid accumulation in liver, ChREBP is also expressed in adipocytes. There are limited data available on ChREBP in fat, but it appears to be induced by glucose, insulin, and TZDs, and repressed by fatty acids57.

2.3. Lipolysis

Lipids deposited in adipose tissue during periods of nutrient availability must be broken down and released as fatty acids to supply other tissues during periods of fasting. This process involves the sequential deesterification of fatty acids from the glycerol backbone by a succession of lipases followed by release of glycerol and free fatty acids (FFAs) into the circulation. FFAs and glycerol are substrates for gluconeogenesis and ketogenesis, respectively, in the liver, and FFA is used by skeletal muscle and heart as an energy source58.

The conversion of triacylglycerol (TAG) to diacylglycerol (DAG) is performed primarily by the recently discovered adipocyte triglyceride lipase (ATGL)59. The best-known lipase involved in lipolysis is hormone sensitive lipase (HSL), which converts DAG to monoacylglerol (MAG), which is in turn hydrolysed by monoglyceride hydrolase (MGH). Other enzymes may also participate in lipolysis in adipocytes, such as carboxyesterase 3, also known as triglyceride hydrolase (TGH).

Historically, the metabolic control of lipolysis has been believed to be strictly under the control of signal transduction cascades that respond quickly to a change in nutritional status, rather than regulation at the level of gene expression. The classic example is HSL, which is phosphorylated in fasting by protein kinase A (PKA), leading to translocation of HSL from the cytosol to the lipid droplet. More recent studies, however, suggest that other lipolytic enzymes, such as ATGL, may be subject to nutritional regulation of gene expression. The expression of ATGL, for example, is sharply repressed by insulin58, which likely accounts for some of the anti-lipolytic actions of that hormone.

Another way that lipolysis is regulated transcriptionally is by the induction of glycerol kinase (GyK) by TZDs in isolated rodent adipocytes. GyK catalyzes the phosphorylation of glycerol to generate glycerol-3-phosphate, which is the first step in the resynthesis of acylglycerols. GyK was long believed to be absent in adipocytes, consistent with the idea that such activity would lead to futile cycling. Lazar and colleagues showed that GyK is abundantly expressed when PPARγ is activated, resulting in reduced FFA release60. Contrary data exist in human adipocytes, however, suggesting that GyK activation by TZDs does not contribute to the beneficial effects of these agents in our species61.

Lipolysis can also be stimulated by activation of PPARδ in adipocytes, either by adding a PPARδ-specific ligand or by expressing a pre-activated PPARδ allele62. Mice expressing PPARδ fused to the viral activating protein VP16 specifically in adipocytes are protected from obesity, and ectopic expression of the same fusion protein in cultured adipocytes increases both lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation63. Interestingly, global PPARδ knockout mice are more prone to obesity than wild-type controls, but adipocyte-specific knockout mice do not show this effect64. One way to reconcile these data is to suggest that PPARδ is not required for basal lipolysis in adipocytes, but activation of this receptor can cause enhanced lipid hydrolysis and oxidation. In this scenario, increased adiposity in the global knockouts would reflect altered PPARδ-mediated fatty acid oxidation in liver, muscle, and possibly other non-adipose tissues. It has been proposed that the cannabinoid receptor CB1R may be a relevant target of PPARδ in white adipose tissue62. PPARδ represses CB1R expression, and CB1R is antilipolytic. This is a plausible pathway but there is little direct experimental evidence to support it at this time.

2.4. Insulin-stimulated glucose uptake

The ability to take up glucose in an insulin-dependent manner is a cardinal feature of adipocytes. This process involves a signal transduction cascade beginning with the insulin receptor and culminating with the translocation of Glut4-containing vesicles to the cell surface. The number of proteins known to be involved in insulin signaling is large and ever-growing, but relatively little is known about the transcription factors that regulate the expression of these proteins in adipocytes.

Adipocytes (along with muscle cells) are unique in utilizing the specialized glucose transporter Glut4, which is normally located in vesicles below the cell surface in the basal state. In the presence of insulin, these vesicles translocate to the cell surface. Insulin resistant humans show a significant reduction in adipocyte Glut4 expression, the cause of which is uncertain. This can be reversed by treatment with TZD. Transcription of Glut4 mRNA is regulated by a number of transcription factors implicated in cell metabolism, including C/EBPα, KLF15, SREBP-1c, MEF2C, NF-1, EBF1 and LXR40, 65, 66. Other factors directly inhibit Glut4 expression, including IRF467.

One interesting insight was obtained by Wu, et. al., who discovered that cells lacking C/EBPα could be induced to differentiate by expressing PPARγ 32. Despite their morphological appearance as adipocytes, however, these cells lacked normal insulin-stimulated uptake. Part of the defect was traced to the fact that Glut4-containing vesicles were inappropriately located at the cell surface in the absence of insulin, suggesting that C/EBPα may be required for the expression of a key (and as yet undetermined) intracellular vesicle tethering protein68. C/EBPα also regulates the expression of several other genes required for insulin-stimulated glucose uptake, including the insulin receptor itself, as well the signaling intermediate IRS-169.

2.5. Adipokine secretion

As mentioned earlier, the ability of adipocytes to secrete hormones that coordinate a wide variety of metabolic functions throughout the body has only been recently appreciated. The expression of several of these adipokines is regulated at the transcriptional level by fasting and feeding, by obesity, and by drugs like TZDs.

2.5.1. Leptin

The anorexic adipokine leptin is expressed almost entirely by adipose tissue. Leptin performs a wide variety of functions, but the best understood is its role in the regulation of appetite and satiety. Leptin binds to its receptor and activates JAK/STAT signaling in target neurons in several parts of the brain, including the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus70. Leptin activates pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons, which produce the anorexic peptide α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (αMSH), and conversely suppresses the expression of neuropeptide Y (NPY) and agouti-related peptide (AgRP) in orexigenic NPY/AgRP neurons70. Serum leptin levels positively correlate with the mass and lipid content of adipose tissues in rodents and humans. Importantly, obese individuals have elevated serum leptin levels but simultaneously exhibit an impaired leptin response, termed leptin resistance. The expression of leptin is also acutely suppressed by fasting and is activated by refeeding, outside of changes in adiposity.

Amazingly, despite thousands of papers written about leptin, we know very little about the specific transcription factors and pathways that regulate its expression. There is a C/EBP site in the proximal leptin promoter, although this is insufficient to account for the high degree of adipose specificity of leptin expression71. Similarly, nutritional regulation of leptin expression is at least in part mediated by insulin signaling, which acts through the activation of PI3K and MAP kinase in brown adipocytes72. It has been suggested that the transcription factors SREBP1c and Sp1 mediate the insulin effect on leptin transcription52, 73. Leptin is also induced by chronic exposure to glucocorticoids and inflammatory cytokines74. Acute elevation of glucocorticoid, however, does not have an effect on leptin expression75.

2.5.2. Adiponectin

This adipokine is highly tissue-restricted to adipocytes, and circulates in the plasma in various higher-order multimeric complexes4, 7. Adiponectin promotes glucose uptake and utilization as well as fatty acid oxidation in muscle. It also inhibits gluconeogenesis in liver. These actions are mediated through the binding of two seven-transmembrane receptors and subsequent activation of 5’-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). In contrast to leptin, serum adiponectin levels are positively correlated with insulin sensitivity and negatively correlated with obesity; the latter effect is paradoxical given the large increase in adipose mass in the obese state. Also unlike leptin, serum adiponectin concentration is induced by fasting and reduced by feeding76. Adiponectin expression is also modulated by a variety of cytokines and hormones77-79. For example, TNFα and IL-6 suppress adiponectin transcription whereas IGF-1 induces adiponectin expression. Glucocorticoids and β-adrenergic agonists also down-regulate adiponectin transcription, suggesting one mechanism by which these drugs may cause insulin resistance.

Adiponectin gene expression is regulated by a variety of transcription factors, many of which have been implicated in adipogenesis. For example, the pro-adipogenic transcription factors PPARγ 80, C/EBPα 81, 82, and SREBP1c83 activate adiponectin expression whereas the anti-adipogenic factors KLF733 and Id384 inhibit adiponectin promoter activity. Other factors that act on the adiponectin promoter have also been discovered, including the nuclear factor of activated T-cells c4 (NFATc4)82, activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3)82, nuclear factor Y (NF-Y)81 and liver receptor homolog-1 (LRH-1)85. While LRH-1 alone does not induce adiponectin expression, it enhances the effect of PPARγ on adiponectin transcription. Treatment with a TZD causes results in increased serum adiponectin levels, although this effect is only partly mediated by enhanced transcription; PPARγ also enhances the secretion of preformed adiponectin.

2.5.3. RBP4

Retinol binding protein-4 (RBP4) is a protein secreted by liver and adipose tissue. Its role in metabolism was first suggested by a search for adipokines whose expression was altered in response to the changes in adipose Glut4 expression. RBP4 levels are upregulated in adipose Glut4-/- mice and down-regulated in adipose-Glut4 overexpressers86. The serum level of RBP4 is elevated in multiple insulin-resistant mouse models due to elevated expression of RBP4 specifically in adipose tissue. RBP4 transgenic mice or mice injected with recombinant RBP4 display insulin resistance, whereas RBP4 heterozygous or knockout mice are more insulin-sensitive, indicating that circulating RBP4 may cause insulin resistance86. Studies in humans also support the notion that elevated RBP4 level is correlated with insulin resistance87. Preferentially expressed in visceral fat, RBP4 expression is dramatically elevated in obese subjects. There are now a large number of papers looking at the connection between RBP4, obesity, and insulin resistance in various human populations using a variety of technical approaches; not all of these studies have confirmed the proposed relationship (summarized in88). Some of the discrepancies may be due to shortcomings in available commercial assay techniques89.

There is little known about the transcriptional pathways regulating RBP4. Retinoids reduce expression of RBP4 in fat90, as does the PPARα ligand fenofibrate91, although the specific mechanisms involved are still murky.

3. Brown fat: a cell of a different color

All of the functions mentioned above were discussed in the context of white fat, which is the form of adipose tissue that accumulates in obesity. There is another type of fat cell, however, called the brown adipocyte, which is distinguished from white cells by their enhanced metabolic rate associated with increased numbers of mitochondria and the presence of uncoupling protein-1 (UCP-1). UCP-1 dissipates the proton gradient that accumulates across the mitochondrial membrane during electron transport; this results in energy expenditure in the form of heat loss. Animals without UCP-1 are prone to obesity, and ectopic expression of UCP-1 in white adipocytes has a strong anti-obesity effect. This has led to interest in the idea that ‘trans-differentiation’ of white fat to brown could have therapeutic implications.

Brown adipogenesis is controlled by a factor called PRDM16, which acts as a coactivator of PPARγ92. Overexpression of PRDM16 in white fat precursors leads to the acquisition of a brown cell phenotype, complete with UCP-1 expression93. Conversely, RNAi-mediated reduction of PRDM16 in brown adipocytes causes the loss of the brown phenotype. Interestingly, PRDM16 regulates an important development switch involving fat in vivo, but it is not a brown-white switch. Rather, PRDM16 appears to control whether a cell becomes a muscle cell or a brown adipocyte. Mice lacking PRDM16 have abnormal brown fat with enhanced muscle gene expression, and the presence or absence of PRDM16 in cultured myoblasts determines which pathway they follow94.

Other transcriptional regulators are also involved in the full expression of the brown fat phenotype, including pRB, which is reduced in brown fat95, and PGC-1α, which promotes expression of a variety of brown fat genes, particularly those involved in mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation96.

4. Identifying novel transcriptional pathways in adipocytes

It is worth considering how we have learned what we know about transcriptional pathways in adipocyte biology. Generally speaking, key transcription factors have been identified in one of a few ways. For example, some factors were identified because they were highly or specifically expressed in fat. Initially, these studies involved Northern or Western blotting, but newer microarray-based techniques have enhanced our ability to focus on factors based on their expression pattern. For example, the pro-adipogenic factor KLF4 was pulled out of a microarray study looking at genes expressed during various timepoints of adipogenesis37. Other factors were identified because they are orthologous to factors discovered to control metabolism in lower organisms. The Drosophila protein Serpent (Srp), for example, was shown to enhance larval fat body formation in that species97. This led to the hypothesis that GATA factors, which are the mammalian orthologs of Srp, might also be involved in adipogenesis. This, in fact, proved to be true, although interestingly, GATA2 and GATA3 are anti-adipogenic and not pro-adipogenic as was predicted from the known activity of Srp42, 43. Transcriptional pathways have also been inferred from the results of knockout studies in mice, which sometimes yield an unexpected metabolic phenotype. Mice lacking the transcriptional co-repressor RIP140, for example, were lean and resistant to high-fat diet induced obesity98. This proved to be due at least in part to an effect of RIP140 on lipogenic gene expression in adipose tissue.

Newer technologies are also bearing fruit in this area. This includes siRNA screening, which independently identified RIP140 as a player in adipocyte transcriptional pathways involved in fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial biogenesis99. Tontonoz and colleagues performed a small molecule screen looking for compounds that might enhance adipogenesis, and identified an agent called harmine100. Interestingly, harmine activates PPARγ-mediated pathways by affecting PPARγ expression, rather than as a PPARγ ligand. Although the specific molecular target of harmine is still uncertain, this study illustrates that small molecule screening can provide insights in this area. Another new technology that has been applied to adipocyte biology is genome-wide assessment of transcription factor binding using chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by microarray hybridization (‘ChIP-chip’) or massively parallel sequencing (‘ChIP-Seq’). This has been accomplished for PPARγ and C/EBPα during 3T3-L1 adipogenesis, demonstrating a role for these factors in regulating the expression of a huge number of metabolically relevant genes in fat10, 11. Importantly, this approach can enable deeper understanding of how a particular transcription factor regulates adipocyte physiology, but it requires that one have a priori knowledge of which factor to look at.

Another way to approach this problem is not to look directly for novel transcription factors, but to focus on regions of the genome that appear to be important for adipocyte gene expression. By identifying specific motifs of interest in the DNA sequence, one can then infer what the cognate trans-acting factors might be, thus working ‘backward’ to fill in important pathways. This, in fact, was the approach used by Spiegelman and colleagues to identify PPARγ as the key adipogenic transcription factor101. Those experiments involved focusing on a critical region of the FABP4 (also called aP2) promoter known to drive adipose-specific expression of a reporter gene. We have used a conceptually similar approach on a broader scale, using changes in chromatin structure.

Chromatin exists in one of two major forms within a cell. Tightly packed heterochromatin is highly condensed and is generally inaccessible to transcription factors, and is thus considered to be ‘silenced’. Euchromatin, on the other hand, is in a more relaxed conformation and contains regions that are being actively transcribed. Even within euchromatin, however, one can make further distinctions based on a variety of epigenetic modifications. These include direct methylation of DNA on CpG residues, where hypermethylation is associated with reduced gene expression102. There are also a wide range of modifications that occur on histone proteins, including methylation, acetylation, and phosphorylation, and there has been extensive work done to understand the basics of the resulting histone code and how it regulates gene expression102, 103. Importantly, these modifications are perpetrated by a large group of ubiquitous nuclear proteins that do not bind directly; the specificity of chromatin marks within a particular cell type is thus dependent upon the complement of sequence-specific transcription factors that are active at that place and time. Changes in chromatin marks therefore ‘tag’ regions where such transcription factors bind, and motifs discovered within those regions can help identify the relevant factors.

We performed a ‘proof-of-concept’ study of this approach using a medium-throughput assay for DNAse hypersensitive sites flanking a select group of genes chosen for their relative adipose selectivity67. Regions of DNA that have unwound from nucleosomes and are “open” can be preferentially digested with a small amount of the enzyme DNAse I, and are thus considered hypersensitive to DNAseI. These sites correlate well with histone acetylation and other marks denoting important features such as promoters and enhancers. Traditional DNase-hypersensitivity analysis involves iterative Southern blotting, a cumbersome technique which limited the utility of this approach for decades. The use of quantitative PCR (qPCR) to quantify the degree of DNAse sensitivity, however, greatly simplifies the process. In our study, we examined DNAse sensitivity of over 250 highly conserved DNA regions (~ 70 bp in length on average) in the proximal 50 kb upstream of the transcriptional start site and the first intron of 27 adipose-selective genes in mature adipocytes as well as pre-adipocytes. We identified areas that were DNAse sensitive in adipocytes but not precursor cells, and subjected these regions to computational motif finding. Motifs that were overrepresented in DNAse hypersensitive regions included those for the high-mobility group protein HMGI-Y and PPAR, both of which were already known to promote adipogenesis22, 104. Among the unexpected motifs discovered were those corresponding to binding sites for interferon regulatory factors (IRFs) and the orphan nuclear receptors called chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription factors (COUP-TFs). We went on to show that IRF3, IRF4, and COUP-TFII are all expressed in adipose tissues and all exhibit anti-adipogenic activity in differentiation assays67, 105. Despite the fact that these experiments were performed using only a limited amount of flanking sequence from a small number of adipocyte genes, they demonstrate the power of using epigenetic marks as guides to identify novel transcriptional pathways.

Going forward, new technologies will allow us to perform these sorts of studies in a more comprehensive fashion. For example, we are now performing ChIP-Seq to determine the modified histone landscape at several time-points during both human and murine adipogenesis. These studies will allow us to look at events that mark enhanced and repressed regions of chromatin throughout the differentiation process, and will enable us to draw conclusions that are not specific to a single model of adipogenesis. Motifs that are over-represented in regions of interest will be used to suggest interesting transcription factors. One limitation of these studies is the limited representation of transcription factors in the motif databases. There are close to 2,000 transcription factors in the mammalian genome, only several hundred of which bind to defined motifs106. For this reason, advances in motif identification are a prerequisite for further progress. An alternative approach might entail direct proteomic identification of factors binding to regions of interest. This has been a difficult task in the past, but new strategies may make this more tractable in the near future.

Other approaches discussed above will also need to be employed to gain a more complete understanding of transcriptional pathways in adipocytes, including siRNA and small molecule screens. These techniques are becoming more broadly available, and as their cost comes down, more adipocyte biology groups will be empowered to attempt this sort of unbiased screening approach.

5. Expert Opinion

Our understanding of adipose tissue has come a long way from the simplistic notion of a passive energy storage depot. Given its central role in energy homeostasis and nutrient regulation, adipose tissue will remain a critical target in drug development for metabolic disease. Furthermore, we believe strongly that one of the most exciting areas to pursue in this regard is the control of adipocyte gene expression. It bears repeating that the goal of this approach is not to simply make fewer adipocytes; adipocytes serve a critical purpose as a safe place to store excess calories, and life without them would be characterized by significant metabolic dysfunction.

What functions of adipocytes would be most favorable to manipulate? Certainly it would be advantageous to provoke white fat cells to behave more like brown adipocytes. By enhancing lipid breakdown and fatty acid oxidation, while simultaneously releasing energy in the form of heat, one could promote leanness and enhanced insulin sensitivity. Alternatively, some conditions might actually be helped by increasing lipid storage in adipose tissue, as long as this was accompanied by simultaneous reductions in ectopic lipid deposition in liver and muscle. Other strategies could involve changing the synthesis and secretion of selected adipokines. Increasing leptin and/or adiponectin would be beneficial, as would decreasing some of the factors that inhibit global insulin action, like RBP4.

In order to bring some of these ideas closer to the medicine chest, we need to overcome several obstacles. The first is that we still have incomplete knowledge of the role played by adipose tissue in global physiology. While we have learned an extraordinary amount in the last fifteen years, we are still on the steep part of the curve here. Second, we know even less about the transcriptional pathways used by adipocytes to govern these functions. This has been the primary focus of this review, and it should be clear that the community is making strides in this area but that all the pieces of puzzle are not yet on the table. Third, there are obstacles that bedevil drug development in every area. How can transcription factors (other than nuclear receptors) be targeted pharmacologically? How can we achieve tissue specificity so that we affect fat cells but not other cell types? How can we predict unintended adverse consequences, such as the fluid overload sometimes seen with TZD use?

It is important not to oversell the promise of adipocyte-based therapies, but continued research will, we believe, help to solve some of these vexing issues. The result is certain to be exciting, and will lead to new insights that translate to better therapies for metabolic disease.

Figure 1.

Mesenchymal precursor cells can give rise to multiple cell types, include brown and white adipocytes. Recent data indicate that brown fat is ontologically closer to skeletal muscle than white fat, despite many phenotypic similarities between the two types of adipocytes. Prdm16 is a major determinant of the switch between brown fat and muscle. Most of what we know about adipogenesis derives from studies in cell culture models of white fat, although many of the same factors operate in brown fat as well. Key transcription factor families involved in this process include C/EBPs, forkhead proteins, KLFs, and several nuclear receptors, including the master regulator of adipogenesis PPARγ. See text for more details.

Figure 2.

Adipocytes perform a variety of functions that are under the transcriptional control of distinct yet overlapping sets of factors. Glucose uptake (particularly in response to insulin) and lipogenesis are most prominent in the fed state, while lipolysis occurs in the fasted state. Adipokine secretion by fat cells helps to integrate global metabolism, and is under the control of a large and growing number of transcriptional pathways. Please see text for details.

Acknowledgments

Research in the authors’ laboratory has been supported by the National Institutes of Health, the American Diabetes Association, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.James WP. WHO recognition of the global obesity epidemic. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008 Dec;32(Suppl 7):S120–6. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benson L, Baer HJ, Kaelber DC. Trends in the diagnosis of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: 1999-2007. Pediatrics. 2009 Jan;123(1):e153–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature. 1994 Dec 1;372(6505):425–32. doi: 10.1038/372425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rasouli N, Kern PA. Adipocytokines and the metabolic complications of obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Nov;93(11 Suppl 1):S64–73. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farooqi IS, O’Rahilly S. Leptin: a pivotal regulator of human energy homeostasis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Mar;89(3):980S–4S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26788C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catalan V, Gomez-Ambrosi J, Rodriguez A, Salvador J, Fruhbeck G. Adipokines in the treatment of diabetes mellitus and obesity. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009 Feb;10(2):239–54. doi: 10.1517/14656560802618811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. Adipocytes as regulators of energy balance and glucose homeostasis. Nature. 2006 Dec 14;444(7121):847–53. doi: 10.1038/nature05483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao H, Gerhold K, Mayers JR, Wiest MM, Watkins SM, Hotamisligil GS. Identification of a lipokine, a lipid hormone linking adipose tissue to systemic metabolism. Cell. 2008 Sep 19;134(6):933–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rizos CV, Liberopoulos EN, Mikhailidis DP, Elisaf MS. Pleiotropic effects of thiazolidinediones. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008 May;9(7):1087–108. doi: 10.1517/14656566.9.7.1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lefterova MI, Zhang Y, Steger DJ, Schupp M, Schug J, Cristancho A, et al. PPARgamma and C/EBP factors orchestrate adipocyte biology via adjacent binding on a genome-wide scale. Genes Dev. 2008 Nov 1;22(21):2941–52. doi: 10.1101/gad.1709008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nielsen R, Pedersen TA, Hagenbeek D, Moulos P, Siersbaek R, Megens E, et al. Genome-wide profiling of PPARgamma:RXR and RNA polymerase II occupancy reveals temporal activation of distinct metabolic pathways and changes in RXR dimer composition during adipogenesis. Genes Dev. 2008 Nov 1;22(21):2953–67. doi: 10.1101/gad.501108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rizos CV, Elisaf MS, Mikhailidis DP, Liberopoulos EN. How safe is the use of thiazolidinediones in clinical practice? Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2009 Jan;8(1):15–32. doi: 10.1517/14740330802597821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garg A, Agarwal AK. Lipodystrophies: Disorders of adipose tissue biology. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009 Jan 7; doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farmer SR. Molecular determinants of brown adipocyte formation and function. Genes Dev. 2008 May 15;22(10):1269–75. doi: 10.1101/gad.1681308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farmer SR. Transcriptional control of adipocyte formation. Cell Metab. 2006 Oct;4(4):263–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosen ED, MacDougald OA. Adipocyte differentiation from the inside out. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006 Dec;7(12):885–96. doi: 10.1038/nrm2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jimenez MA, Akerblad P, Sigvardsson M, Rosen ED. Critical role for Ebf1 and Ebf2 in the adipogenic transcriptional cascade. Mol Cell Biol. 2007 Jan;27(2):743–57. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01557-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosen ED, Hsu CH, Wang X, Sakai S, Freeman MW, Gonzalez FJ, et al. C/EBPalpha induces adipogenesis through PPARgamma: a unified pathway. Genes Dev. 2002 Jan 1;16(1):22–6. doi: 10.1101/gad.948702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barak Y, Nelson MC, Ong ES, Jones YZ, Ruiz-Lozano P, Chien KR, et al. PPAR gamma is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Mol Cell. 1999 Oct;4(4):585–95. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kubota N, Terauchi Y, Miki H, Tamemoto H, Yamauchi T, Komeda K, et al. PPAR gamma mediates high-fat diet-induced adipocyte hypertrophy and insulin resistance. Mol Cell. 1999 Oct;4(4):597–609. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosen ED, Sarraf P, Troy AE, Bradwin G, Moore K, Milstone DS, et al. PPAR gamma is required for the differentiation of adipose tissue in vivo and in vitro. Mol Cell. 1999 Oct;4(4):611–7. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tontonoz P, Hu E, Spiegelman BM. Stimulation of adipogenesis in fibroblasts by PPAR gamma 2, a lipid-activated transcription factor. Cell. 1994 Dec 30;79(7):1147–56. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheung KJ, Tzameli I, Pissios P, Rovira I, Gavrilova O, Ohtsubo T, et al. Xanthine oxidoreductase is a regulator of adipogenesis and PPARgamma activity. Cell Metab. 2007 Feb;5(2):115–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tzameli I, Fang H, Ollero M, Shi H, Hamm JK, Kievit P, et al. Regulated production of a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma ligand during an early phase of adipocyte differentiation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2004 Aug 20;279(34):36093–102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405346200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JB, Wright HM, Wright M, Spiegelman BM. ADD1/SREBP1 activates PPARgamma through the production of endogenous ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998 Apr 14;95(8):4333–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barroso I, Gurnell M, Crowley VE, Agostini M, Schwabe JW, Soos MA, et al. Dominant negative mutations in human PPARgamma associated with severe insulin resistance, diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Nature. 1999 Dec 23-30;402(6764):880–3. doi: 10.1038/47254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ren D, Collingwood TN, Rebar EJ, Wolffe AP, Camp HS. PPARgamma knockdown by engineered transcription factors: exogenous PPARgamma2 but not PPARgamma1 reactivates adipogenesis. Genes Dev. 2002 Jan 1;16(1):27–32. doi: 10.1101/gad.953802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mueller E, Drori S, Aiyer A, Yie J, Sarraf P, Chen H, et al. Genetic analysis of adipogenesis through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2002 Nov 1;277(44):41925–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206950200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Medina-Gomez G, Virtue S, Lelliott C, Boiani R, Campbell M, Christodoulides C, et al. The link between nutritional status and insulin sensitivity is dependent on the adipocyte-specific peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma2 isoform. Diabetes. 2005 Jun;54(6):1706–16. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang J, Fu M, Cui T, Xiong C, Xu K, Zhong W, et al. Selective disruption of PPARgamma 2 impairs the development of adipose tissue and insulin sensitivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Jul 20;101(29):10703–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403652101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Darlington GJ, Ross SE, MacDougald OA. The role of C/EBP genes in adipocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1998 Nov 13;273(46):30057–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu Z, Rosen ED, Brun R, Hauser S, Adelmant G, Troy AE, et al. Cross-regulation of C/EBP alpha and PPAR gamma controls the transcriptional pathway of adipogenesis and insulin sensitivity. Mol Cell. 1999 Feb;3(2):151–8. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawamura Y, Tanaka Y, Kawamori R, Maeda S. Overexpression of Kruppel-like factor 7 regulates adipocytokine gene expressions in human adipocytes and inhibits glucose-induced insulin secretion in pancreatic beta-cell line. Mol Endocrinol. 2006 Apr;20(4):844–56. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banerjee SS, Feinberg MW, Watanabe M, Gray S, Haspel RL, Denkinger DJ, et al. The Kruppel-like factor KLF2 inhibits peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma expression and adipogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2003 Jan 24;278(4):2581–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210859200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sue N, Jack BH, Eaton SA, Pearson RC, Funnell AP, Turner J, et al. Targeted disruption of the basic Kruppel-like factor gene (Klf3) reveals a role in adipogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2008 Jun;28(12):3967–78. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01942-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oishi Y, Manabe I, Tobe K, Tsushima K, Shindo T, Fujiu K, et al. Kruppel-like transcription factor KLF5 is a key regulator of adipocyte differentiation. Cell Metab. 2005 Jan;1(1):27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Birsoy K, Chen Z, Friedman J. Transcriptional regulation of adipogenesis by KLF4. Cell Metab. 2008 Apr;7(4):339–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li D, Yea S, Li S, Chen Z, Narla G, Banck M, et al. Kruppel-like factor-6 promotes preadipocyte differentiation through histone deacetylase 3-dependent repression of DLK1. J Biol Chem. 2005 Jul 22;280(29):26941–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500463200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mori T, Sakaue H, Iguchi H, Gomi H, Okada Y, Takashima Y, et al. Role of Kruppel-like factor 15 (KLF15) in transcriptional regulation of adipogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2005 Apr 1;280(13):12867–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410515200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gray S, Feinberg MW, Hull S, Kuo CT, Watanabe M, Sen-Banerjee S, et al. The Kruppel-like factor KLF15 regulates the insulin-sensitive glucose transporter GLUT4. J Biol Chem. 2002 Sep 13;277(37):34322–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201304200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akerblad P, Lind U, Liberg D, Bamberg K, Sigvardsson M. Early B-cell factor (O/E-1) is a promoter of adipogenesis and involved in control of genes important for terminal adipocyte differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2002 Nov;22(22):8015–25. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.8015-8025.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tong Q, Dalgin G, Xu H, Ting CN, Leiden JM, Hotamisligil GS. Function of GATA transcription factors in preadipocyte-adipocyte transition. Science. 2000 Oct 6;290(5489):134–8. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5489.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tong Q, Tsai J, Tan G, Dalgin G, Hotamisligil GS. Interaction between GATA and the C/EBP family of transcription factors is critical in GATA-mediated suppression of adipocyte differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005 Jan;25(2):706–15. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.2.706-715.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakae J, Kitamura T, Kitamura Y, Biggs WH, 3rd, Arden KC, Accili D. The forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 regulates adipocyte differentiation. Dev Cell. 2003 Jan;4(1):119–29. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00401-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakae J, Cao Y, Oki M, Orba Y, Sawa H, Kiyonari H, et al. Forkhead transcription factor FoxO1 in adipose tissue regulates energy storage and expenditure. Diabetes. 2008 Mar;57(3):563–76. doi: 10.2337/db07-0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolfrum C, Shih DQ, Kuwajima S, Norris AW, Kahn CR, Stoffel M. Role of Foxa-2 in adipocyte metabolism and differentiation. J Clin Invest. 2003 Aug;112(3):345–56. doi: 10.1172/JCI18698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davis KE, Moldes M, Farmer SR. The forkhead transcription factor FoxC2 inhibits white adipocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2004 Oct 8;279(41):42453–61. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402197200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gerin I, Bommer GT, Lidell ME, Cederberg A, Enerback S, Macdougald OA. On the role of FOX transcription factors in adipocyte differentiation and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. J Biol Chem. 2009 Feb 24; doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809115200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cederberg A, Gronning LM, Ahren B, Tasken K, Carlsson P, Enerback S. FOXC2 is a winged helix gene that counteracts obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, and diet-induced insulin resistance. Cell. 2001 Sep 7;106(5):563–73. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00474-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Letexier D, Pinteur C, Large V, Frering V, Beylot M. Comparison of the expression and activity of the lipogenic pathway in human and rat adipose tissue. J Lipid Res. 2003 Nov;44(11):2127–34. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300235-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coleman RA, Lee DP. Enzymes of triacylglycerol synthesis and their regulation. Prog Lipid Res. 2004 Mar;43(2):134–76. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(03)00051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim JB, Sarraf P, Wright M, Yao KM, Mueller E, Solanes G, et al. Nutritional and insulin regulation of fatty acid synthetase and leptin gene expression through ADD1/SREBP1. J Clin Invest. 1998 Jan 1;101(1):1–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shimano H, Shimomura I, Hammer RE, Herz J, Goldstein JL, Brown MS, et al. Elevated levels of SREBP-2 and cholesterol synthesis in livers of mice homozygous for a targeted disruption of the SREBP-1 gene. J Clin Invest. 1997 Oct 15;100(8):2115–24. doi: 10.1172/JCI119746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shimomura I, Hammer RE, Richardson JA, Ikemoto S, Bashmakov Y, Goldstein JL, et al. Insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus in transgenic mice expressing nuclear SREBP-1c in adipose tissue: model for congenital generalized lipodystrophy. Genes Dev. 1998 Oct 15;12(20):3182–94. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.20.3182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Juvet LK, Andresen SM, Schuster GU, Dalen KT, Tobin KA, Hollung K, et al. On the role of liver X receptors in lipid accumulation in adipocytes. Mol Endocrinol. 2003 Feb;17(2):172–82. doi: 10.1210/me.2001-0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gerin I, Dolinsky VW, Shackman JG, Kennedy RT, Chiang SH, Burant CF, et al. LXRbeta is required for adipocyte growth, glucose homeostasis, and beta cell function. J Biol Chem. 2005 Jun 17;280(24):23024–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412564200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.He Z, Jiang T, Wang Z, Levi M, Li J. Modulation of carbohydrate response element-binding protein gene expression in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and rat adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004 Sep;287(3):E424–30. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00568.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang S, Soni KG, Semache M, Casavant S, Fortier M, Pan L, et al. Lipolysis and the integrated physiology of lipid energy metabolism. Mol Genet Metab. 2008 Nov;95(3):117–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zimmermann R, Lass A, Haemmerle G, Zechner R. Fate of fat: The role of adipose triglyceride lipase in lipolysis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008 Oct 29; doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guan HP, Li Y, Jensen MV, Newgard CB, Steppan CM, Lazar MA. A futile metabolic cycle activated in adipocytes by antidiabetic agents. Nat Med. 2002 Oct;8(10):1122–8. doi: 10.1038/nm780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tan GD, Debard C, Tiraby C, Humphreys SM, Frayn KN, Langin D, et al. A “futile cycle” induced by thiazolidinediones in human adipose tissue? Nature Medicine. 2003;9:811–2. doi: 10.1038/nm0703-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Lange P, Lombardi A, Silvestri E, Goglia F, Lanni A, Moreno M. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Delta: A Conserved Director of Lipid Homeostasis through Regulation of the Oxidative Capacity of Muscle. PPAR Res. 2008;2008:172676. doi: 10.1155/2008/172676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang YX, Lee CH, Tiep S, Yu RT, Ham J, Kang H, et al. Peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor delta activates fat metabolism to prevent obesity. Cell. 2003 Apr 18;113(2):159–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00269-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barak Y, Liao D, He W, Ong ES, Nelson MC, Olefsky JM, et al. Effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta on placentation, adiposity, and colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002 Jan 8;99(1):303–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012610299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Im SS, Kwon SK, Kim TH, Kim HI, Ahn YH. Regulation of glucose transporter type 4 isoform gene expression in muscle and adipocytes. IUBMB Life. 2007 Mar;59(3):134–45. doi: 10.1080/15216540701313788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dowell P, Cooke DW. Olf-1/early B cell factor is a regulator of glut4 gene expression in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2002 Jan 18;277(3):1712–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108589200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eguchi J, Yan QW, Schones DE, Kamal M, Hsu CH, Zhang MQ, et al. Interferon regulatory factors are transcriptional regulators of adipogenesis. Cell Metab. 2008 Jan;7(1):86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wertheim N, Cai Z, McGraw TE. The transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha is required for the intracellular retention of GLUT4. J Biol Chem. 2004 Oct 1;279(40):41468–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405088200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Araki E, Haag BL, 3rd, Matsuda K, Shichiri M, Kahn CR. Characterization and regulation of the mouse insulin receptor substrate gene promoter. Mol Endocrinol. 1995 Oct;9(10):1367–79. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.10.8544845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abizaid A, Horvath TL. Brain circuits regulating energy homeostasis. Regul Pept. 2008 Aug 7;149(1-3):3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.He Y, Chen H, Quon MJ, Reitman M. The mouse obese gene. Genomic organization, promoter activity, and activation by CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha. J Biol Chem. 1995 Dec 1;270(48):28887–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Buyse M, Viengchareun S, Bado A, Lombes M. Insulin and glucocorticoids differentially regulate leptin transcription and secretion in brown adipocytes. FASEB J. 2001 Jun;15(8):1357–66. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0669com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mason MM, He Y, Chen H, Quon MJ, Reitman M. Regulation of leptin promoter function by Sp1, C/EBP, and a novel factor. Endocrinology. 1998 Mar;139(3):1013–22. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.3.5792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Grunfeld C, Zhao C, Fuller J, Pollack A, Moser A, Friedman J, et al. Endotoxin and cytokines induce expression of leptin, the ob gene product, in hamsters. J Clin Invest. 1996 May 1;97(9):2152–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI118653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Torpy DJ, Bornstein SR, Cizza G, Chrousos GP. The effects of glucocorticoids on leptin levels in humans may be restricted to acute pharmacologic dosing. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998 May;83(5):1821–2. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.5.4821-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bertile F, Raclot T. Differences in mRNA expression of adipocyte-derived factors in response to fasting, refeeding and leptin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004 Jul 5;1683(1-3):101–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fasshauer M, Klein J, Neumann S, Eszlinger M, Paschke R. Adiponectin gene expression is inhibited by beta-adrenergic stimulation via protein kinase A in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. FEBS Lett. 2001 Oct 26;507(2):142–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02960-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fasshauer M, Klein J, Neumann S, Eszlinger M, Paschke R. Hormonal regulation of adiponectin gene expression in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002 Jan 25;290(3):1084–9. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fasshauer M, Kralisch S, Klier M, Lossner U, Bluher M, Klein J, et al. Adiponectin gene expression and secretion is inhibited by interleukin-6 in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003 Feb 21;301(4):1045–50. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gustafson B, Jack MM, Cushman SW, Smith U. Adiponectin gene activation by thiazolidinediones requires PPAR gamma 2, but not C/EBP alpha-evidence for differential regulation of the aP2 and adiponectin genes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003 Sep 5;308(4):933–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01518-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Park SK, Oh SY, Lee MY, Yoon S, Kim KS, Kim JW. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein and nuclear factor-Y regulate adiponectin gene expression in adipose tissue. Diabetes. 2004 Nov;53(11):2757–66. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.11.2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kim HB, Kong M, Kim TM, Suh YH, Kim WH, Lim JH, et al. NFATc4 and ATF3 negatively regulate adiponectin gene expression in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Diabetes. 2006 May;55(5):1342–52. doi: 10.2337/db05-1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Seo JB, Moon HM, Noh MJ, Lee YS, Jeong HW, Yoo EJ, et al. Adipocyte determination- and differentiation-dependent factor 1/sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c regulates mouse adiponectin expression. J Biol Chem. 2004 May 21;279(21):22108–17. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400238200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Doran AC, Meller N, Cutchins A, Deliri H, Slayton RP, Oldham SN, et al. The helix-loop-helix factors Id3 and E47 are novel regulators of adiponectin. Circ Res. 2008 Sep 12;103(6):624–34. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.175893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Iwaki M, Matsuda M, Maeda N, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y, Makishima M, et al. Induction of adiponectin, a fat-derived antidiabetic and antiatherogenic factor, by nuclear receptors. Diabetes. 2003 Jul;52(7):1655–63. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.7.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yang Q, Graham TE, Mody N, Preitner F, Peroni OD, Zabolotny JM, et al. Serum retinol binding protein 4 contributes to insulin resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2005 Jul 21;436(7049):356–62. doi: 10.1038/nature03711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Graham TE, Yang Q, Bluher M, Hammarstedt A, Ciaraldi TP, Henry RR, et al. Retinol-binding protein 4 and insulin resistance in lean, obese, and diabetic subjects. N Engl J Med. 2006 Jun 15;354(24):2552–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.von Eynatten M, Humpert PM. Retinol-binding protein-4 in experimental and clinical metabolic disease. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2008 May;8(3):289–99. doi: 10.1586/14737159.8.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Graham TE, Wason CJ, Bluher M, Kahn BB. Shortcomings in methodology complicate measurements of serum retinol binding protein (RBP4) in insulin-resistant human subjects. Diabetologia. 2007 Apr;50(4):814–23. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0557-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mercader J, Granados N, Bonet ML, Palou A. All-trans retinoic acid decreases murine adipose retinol binding protein 4 production. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2008;22(1-4):363–72. doi: 10.1159/000149815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wu H, Wei L, Bao Y, Lu J, Huang P, Liu Y, et al. Fenofibrate Reduces Serum Retinol Binding Protein 4 by Suppressing its Expression in Adipose Tissue. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Dec 16; doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90526.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kajimura S, Seale P, Tomaru T, Erdjument-Bromage H, Cooper MP, Ruas JL, et al. Regulation of the brown and white fat gene programs through a PRDM16/CtBP transcriptional complex. Genes Dev. 2008 May 15;22(10):1397–409. doi: 10.1101/gad.1666108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Seale P, Kajimura S, Yang W, Chin S, Rohas LM, Uldry M, et al. Transcriptional control of brown fat determination by PRDM16. Cell Metab. 2007 Jul;6(1):38–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Seale P, Bjork B, Yang W, Kajimura S, Chin S, Kuang S, et al. PRDM16 controls a brown fat/skeletal muscle switch. Nature. 2008 Aug 21;454(7207):961–7. doi: 10.1038/nature07182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hansen JB, Jorgensen C, Petersen RK, Hallenborg P, De Matteis R, Boye HA, et al. Retinoblastoma protein functions as a molecular switch determining white versus brown adipocyte differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Mar 23;101(12):4112–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0301964101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Puigserver P. Tissue-specific regulation of metabolic pathways through the transcriptional coactivator PGC1-alpha. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005 Mar;29(Suppl 1):S5–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hayes SA, Miller JM, Hoshizaki DK. serpent, a GATA-like transcription factor gene, induces fat-cell development in Drosophila melanogaster. Development. 2001 Apr;128(7):1193–200. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.7.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Leonardsson G, Steel JH, Christian M, Pocock V, Milligan S, Bell J, et al. Nuclear receptor corepressor RIP140 regulates fat accumulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Jun 1;101(22):8437–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401013101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Puri V, Virbasius JV, Guilherme A, Czech MP. RNAi screens reveal novel metabolic regulators: RIP140, MAP4k4 and the lipid droplet associated fat specific protein (FSP) 27. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2008 Jan;192(1):103–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2007.01786.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Waki H, Park KW, Mitro N, Pei L, Damoiseaux R, Wilpitz DC, et al. The small molecule harmine is an antidiabetic cell-type-specific regulator of PPARgamma expression. Cell Metab. 2007 May;5(5):357–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Graves RA, Tontonoz P, Platt KA, Ross SR, Spiegelman BM. Identification of a fat cell enhancer: analysis of requirements for adipose tissue-specific gene expression. J Cell Biochem. 1992 Jul;49(3):219–24. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240490303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bernstein BE, Meissner A, Lander ES. The mammalian epigenome. Cell. 2007 Feb 23;128(4):669–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yu H, Zhu S, Zhou B, Xue H, Han JD. Inferring causal relationships among different histone modifications and gene expression. Genome Res. 2008 Aug;18(8):1314–24. doi: 10.1101/gr.073080.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Melillo RM, Pierantoni GM, Scala S, Battista S, Fedele M, Stella A, et al. Critical role of the HMGI(Y) proteins in adipocytic cell growth and differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2001 Apr;21(7):2485–95. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.7.2485-2495.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 105.Xu Z, Yu S, Hsu CH, Eguchi J, Rosen ED. The orphan nuclear receptor chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription factor II is a critical regulator of adipogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Feb 19;105(7):2421–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707082105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Matys V, Kel-Margoulis OV, Fricke E, Liebich I, Land S, Barre-Dirrie A, et al. TRANSFAC and its module TRANSCompel: transcriptional gene regulation in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006 Jan 1;34(Database issue):D108–10. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]