Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to determine the expressions of Rb, p16, and cyclin D1 in soft tissue sarcomas, and we also wanted to identify the prognostic factors according to the clinicalpathologic features.

Materials and Methods

We reviewed the charts and radiographic films of 66 sarcoma patients. Tissue samples were collected from these patients. Immunochemistry was performed using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue samples to examine the expressions of p16, Rb, and cyclin D1 proteins.

Results

The median duration of overall survival was 47.8 months (range, 20.0 to 70.7 months) and the 5 years survival rate was 39%. As for the correlation between the degree of immunohistochemical staining for Rb protein and the histological tumor grades, there was a significant difference with a p-value of 0.019. However, no significant correlation was shown for p16 and cyclin D1. The overall survival duration of the Rb negative group (staining cell <20%) and the heterogeneous group (cell staining 20 to 80%) was 53.5±6.6 months and the overall survival duration of the Rb homogeneous group was 18.3±6.4 months, and there was a significant difference with a p-value of 0.016. However, no significant difference was shown between the survival rate according to the p16 and cyclin D1 expressions. On the multivariate analysis that was done with Rb, p16, the tumor size, grade and site, and patient age, the Rb gene expression was the most significant independent prognostic factor with a risk ratio of 3.01 (p=0.04).

Conclusion

The expression of Rb protein was correlated with the histologic grade and overall survival of patients with soft tissue sarcomas.

Keywords: Sarcoma, Retinoblastoma protein, p16 protein, Cyclin D1

Introduction

Soft tissue sarcomas that develop in various soft tissues, including muscles, ligaments, fibrotic tissue, fat tissue and synovial tissue, are relatively rare tumors that account for only 1% of all malignant tumors (1). They are diverse not only for their pathology, but also for their prognosis and the body sites affected by these tumors, and they are basically considered as similar diseases that have many common characteristics. Although the etiology of soft tissue sarcoma has not been determined, factors such as genetic factors, repeated injuries and exposure to radiation and carcinogens are being considered. These tumors frequently affect adolescents and young adults. Even though the treatment outcome for these sarcomas is being improved with the recent development of histological grading, radiation therapy and chemotherapy, the reported 5 year survival rate for the patients with poorly differentiated tumor is less than 50% even though they are treated with wide resection. The histological type, grade, the size and location of the primary lesion, the degree of cellular differentiation and mitosis, invasion into lymph nodes and veins, perineural invasion and the presence of cancer cells in the resection margin significantly affect the clinical patterns and prognosis of soft tissue sarcomas (2). It is difficult to predict the prognosis using the clinical characteristics of soft tissue sarcomas because of the pathologic variations. Thus, the field of soft tissue sarcoma needs studies on their molecular profiles, and this has been previously done for other types of cancer.

It is known that an abnormal expression of cell cycle regulating molecules causes cancer by changing the cell cycle, which results in unlimited cellular proliferation. Usually, most cancers have problems in the G1→S phase transition of the cell cycle. It is known that this process is modulated by two pathways, i.e., the p16-cyclin D1/CDK4-pRb pathway and the p53 pathway. The first p16-cyclin D1/CDK4-pRb pathway is modulated by G1 cyclin (cyclin D1, E) and cyclin dependent kinases (CDKs; CDK2, CDK4). The activity of CDKs is controlled by specific proteins called cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors (CDKI) such as p21/Clip1/Wafl, p27/Kipl and p16/Ink4A. During the second p53 pathway, the Tp53 gene and protein, mdm2 protein and p21/Clip1/Wafl inhibit the activity of CDK to temporarily stop the cell cycle and induce DNA repair at the time of DNA injury.

Among the various genes participating in these two mechanisms, the focus of this study was the 3 genes, that is, the Rb, p16 and cyclin D1 genes. The gene for Rb protein is located in the 13th chromosome and Rb protein combines with DNA to inhibit the transition from the G1→S phase and so it affects cellular differentiation. Rb gene deletion is seen in retinoblastoma, bone sarcoma, soft tissue sarcoma, small cell lung carcinoma, breast cancer and prostate cancer, and it can be detected through immunohistochemical staining.

Second, p16 is a tumor suppressor gene located on chromosome 9p21 and it encodes p16INK4A (cyclin-CDK inhibitor). Damage of this gene has been detected in various cancers in recent years, including non-small cell lung cancer, neuroglioma, leukemia and bladder cancer. Third, the gene for cyclin D1 is located on chromosome 11q13 and the proliferation of this gene has been detected in breast cancer and esophagus cancer. Several recent studies about these gene abnormalities that affect the development and progression of various cancers are underway, including breast cancer, lung cancer and prostate cancer.

Yao et al. (3) reported that p16 gene mutation is seen in about 20% of soft tissue sarcomas and CDK4, the target protein of p16 gene, was overexpressed in about 60% of soft tissue sarcomas. Karpeh et al. (4) reported that Rb gene mutation is seen in 86% of liposarcomas, 76% of leiomyosarcomas and 75% of all soft tissue sarcomas. Kim et al. (5) reported the overexpression of cyclin D1, E and A in 29%, 33% and 11% of all soft tissue sarcomas, respectively, and this is related to poor differentiation and a poor prognosis. Meye et al. (6) reported a correlation between the p16 and p53 genes and between the p16 and Rb genes in soft tissue sarcomas.

This study was conducted to evaluate the expression of p16, cyclin D1, and pRb proteins, which are known to be involved in the carcinogenetic mechanism of soft tissue sarcomas, in tissue samples of soft tissue sarcomas and to determine their correlation with the clinical prognosis and survival of the patients with these tumors.

Materials and Methods

1. Subjects and the soft tissue sarcoma tissue samples

The paraffin-embedded tissues were collected from 66 patients who were diagnosed as soft tissue sarcomas.

2. Immunohistochemical staining

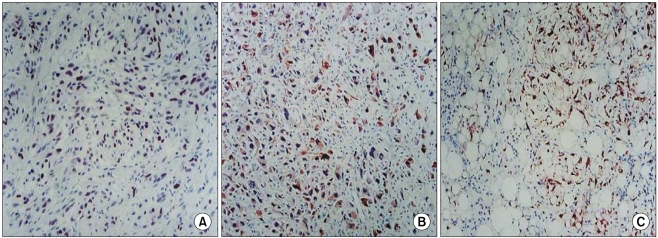

Immunohistochemical staining was performed on the formalin fixed, paraffin-embedded soft tissue sarcoma tissues for p16, cyclin D1, and Rb proteins (Fig. 1). After making 5 µm tissue slices by slicing the paraffin-embedded tissue sample using a sliding microtome (Labomedic, Switzerland) attached with microtome blades (S35 type, FEATHER, Japan), the tissue slices were attached to a plus slide. The sample slice on the slide had the paraffin removed by treating the sample at 80℃ for 5 minutes, washing it with alcohol at room temperature for dehydration and then it was reacted with blocking buffer at 40℃ for 4 minutes. After incubating the sample with the primary antibodies for p16, cyclin D1 and Rb (Zymed, San Francisco, CA) for 20 minutes at 40℃, the sample was washed, reacted with the secondary antibodies that were bound with biotin for 4 minutes and then reacted with streptavidin horseradish peroxidase (HRP), which has a strong affinity for biotin, for 4 minutes at 40℃. After reacting the sample with the chromogen, stable DAB for 5 minutes at 40℃, it was conterstained with hematoxylin for 20 seconds at room temperature.

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemical staining of Rb, (A) p16, (B) cyclin D1, (C) in soft tissue sarcoma, which shows strong positive reaction in most of their nuclei (×400).

3. Collecting the clinical data

The medical records, surgical findings, pathologic reports and radiological finding were analyzed to collect data that included the patients' age, gender, performance status at the time of diagnosis, the histological grade at the time of diagnosis, the presence/absence of metastasis, the metastatic organs, the size of the primary tumor, the surgery that was performed, the treatment outcomes, the patients' survival and the causes of death. Pathological reevaluation was performed to determine the histological differentiation, mitosis and invasion into lymphatics, veins and nerves.

4. Reading the immunohistochemical staining

Two pathologists evaluated the results of the immunohistochemical staining. The FNCLCC system (Federation National de Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer) was used to classify the results by dividing the degree of histological differentiation into scores of 1-3, the degree of mitosis into scores of 1-3 and the degree of tumor necrosis into scores of 1-3 (7). A positive result was seen for p16 and Rb in more than 80% of the samples. The positive controls we used were colon cancer tissue. The positive control used for cyclin D1 was breast cancer tissue, and the result was defined as positive when more than 10% staining was seen.

5. Statistical analysis

SPSS ver. 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for the statistical analysis. Univariate analysis was done using the log rank test, and multivariate analysis was done using the Cox regression model. Correlation analysis was done by Fisher's exact test.

Results

1. Clinical characteristics of the patients

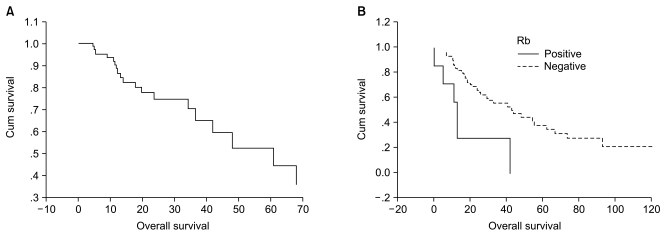

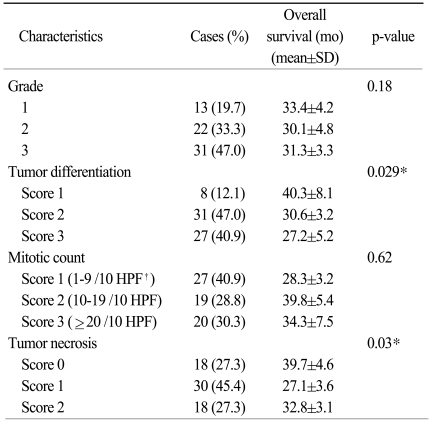

The patients included 37 men and 29 women. Their median age was 50 years old (range, 40 to 62 years). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the patients according to the histological type, the tumor location, tumor size and the presence of lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis. The average survival duration for all the patients was 47.8 months (range, 20.0 to 70.7 months). The 5-year survival rate was 39% (Fig. 2A). A significant difference was shown in the average survival duration according to the presence of distant metastasis (55.8±6.8 vs. 33.9±8.9, respectively, p=0.047). According to the histological grades, the average survival duration was 33.4±4.2 months for Grade 1 (19.7%), 30.1±4.8 months for Grade 2 (33.3%) and 31.3±3.3 months for Grade 3 (47.0%). Table 2 shows the prognosis according to the histological characteristics. The survival duration was significantly correlated with tumor differentiation and tumor necrosis, but not with the mitotic count.

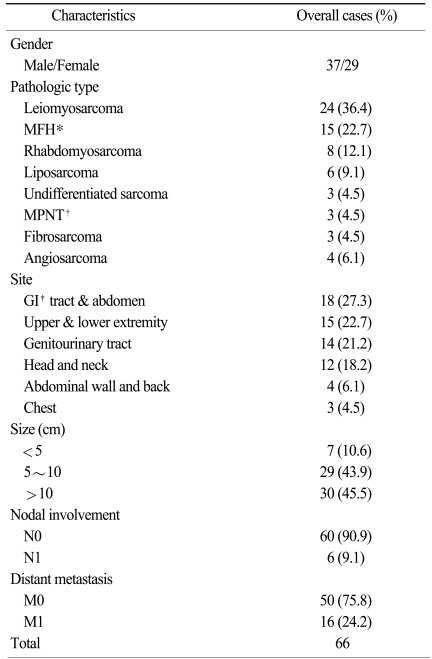

Table 1.

Patients' characteristics

*malignant fibrous histiocytoma, †malignant primitive neuroectodermal tumor, ‡gastrointestinal.

Fig. 2.

(A) Overall survival curve. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curve according to the expression level of Rb protein.

Table 2.

The correlation between the histologic grade and overall survival

*statistically significant, †high power field.

2. Clinical characteristics and the expressions of Rb, p16 and cyclin D1 proteins

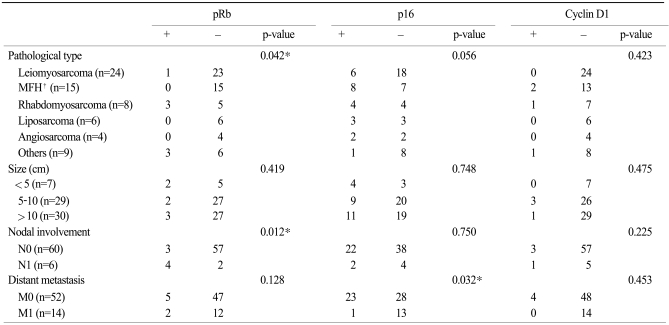

Table 3 shows clinical characteristics of the patients and the distributions of Rb, p16, and cyclin D1 proteins according to the immunohistochemical staining. Rb protein showed a significant correlation with the histological type and lymph node metastasis. The rate of distant metastasis was significantly higher in the patients who showed a p16 protein expression compared with p16 protein-negative patients.

Table 3.

Correlation between Rb, p16 and cyclin D1 oncoprotein and the clinical factors of soft tissue sarcoma

*statistically significant, †malignant fibrous histiocytoma.

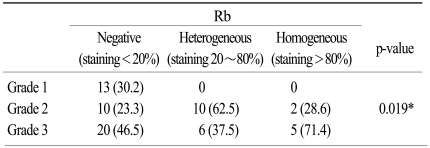

3. Histological grades and the expressions of Rb, p16 and cyclin D1 proteins

As for the relationship between the Rb protein expression and the histological differentiation, an increased Rb protein expression was related to poor histological differentiation with a statistically significant difference (p=0.019). On the other hand, p16 and cyclin D1 had no statistically significant correlation with the histological differentiation. Table 4 shows the relationship between histological differentiation and Rb protein.

Table 4.

Correlation between the histologic grade and Rb protein

Values are presented as number (%). *statistically significant.

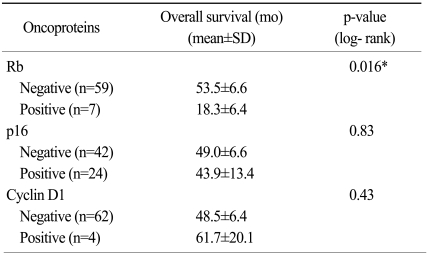

4. The expressions of Rb, p16 and cyclin D1 proteins and overall survival

The average survival duration in the Rb negative and heterogeneous patients (0% to 80% positive staining for Rb expression) was 53.5±6.6 months and that in the Rb homogeneous patients (more than 80% positive staining for Rb expression) was 18.3±6.4 months. There was a statistically significant difference between two groups (p=0.016). There was no significant difference of the survival duration according to p16 and cyclin D1 (Table 5, Fig. 2B).

Table 5.

Overall survival according to the expression of Rb, p16 and cyclin D1

*statistically significant.

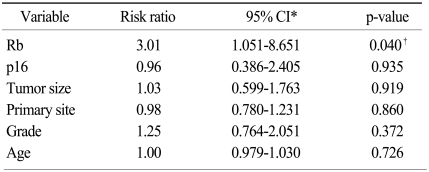

5. Multivariate analysis using Cox regression analysis

According to the multivariate analysis of Rb, p16, the tumor size and location, age and the histological grades, Rb protein was a statistically significant prognostic factor for patient survival (p=0.04) (Table 6).

Table 6.

The prognostic factors of soft tissue sarcoma (Cox regression analysis)

*confidence interval, †statistically significant.

Discussion

Soft tissue sarcomas develop in various soft tissues, including muscles, ligaments, fibrotic tissue, fat tissue and synovial tissue, and these are relatively rare tumors that account for only 1% of all malignant tumors. Soft tissue sarcomas are not a single disease, but rather, they are a collection of 60 different tumors having similar histopathological and clinical characteristics. It is very difficult to predict the prognosis of patients with these tumors and to conduct clinical trials for soft tissue sarcoma due to the various diseases and their rare incidence. Generally, they are locally invasive tumors. It is known that regional lymph node metastasis is rare at less than 10% and they mostly undergo hematogenous metastasis that includes the lungs, bone and liver.

In order to evaluate the prognostic factors of soft tissue sarcomas, Li et al. (2) examined the histologic grades, gender, diagnosis, anatomical location and size, treatment factors, the ploidic data, age and resection margin invasion after surgery as the prognostic factors, they reported that the size of the primary lesion is the most important prognostic factor than other factors. However, it is difficult to identify general prognostic factors due to the tumors' histological diversity and the diversity of tumor location, and attempts are currently being made to find new prognostic factors. According to the histological types of tumor in the present study, a relatively good prognosis was seen for fibrosarcoma and liposarcoma, and a relatively poor prognosis was seen for malignant primitive neuroectodermal tumor (MPNT) and rhabdomyosarcoma. Furthermore, tumors located in the abdomen, back and the upper and lower extremities showed a better prognosis compared to those located in the chest. However, no significant difference of the prognosis was shown for tumor size, and this is probably due to the diversity of the patients' tumor locations and histology.

According to the FNCLCC system of histological grade classification, three factors were determined, i.e., differentiation, the mitotic count and necrosis. Among these three, differentiation (p=0.003) and tumor necrosis (p=0.03) were directly related with the survival rate, but no statistical significance was found according to the mitotic count. Furthermore, the histological grading also did not show significant correlation with the prognosis and probably because of the weak relationship of the prognosis with the mitotic count. Other histological grading systems should be considered in the future in order to confirm the correlation between the prognosis and the histological grading of soft tissue sarcomas.

It is known that the three genes (Rb, p16 and cyclin D1) that modulate the cell cycle are closely related. Rb inactivation, p16 (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor) inactivation and cyclin D1 activation are mutually related. The expressions of these proteins are increased when these genes change and this increases the number of cells that are stained immunohistologically. These genes that modulate the G1 phase of the cell cycle are closely related to the prognosis of patients with various malignant tumors. Brambilla et al. (8) reported that a negative Rb protein expression and a positive p16 protein expression showed a poor prognosis for patients with non-small cell lung cancer, but they found no correlation with cyclin D1 and the prognosis. In addition, Huang et al. (9), Kawabuchi et al. (10) and Hommura et al. (11) reported that the loss of the p16 expression is related to a poor prognosis and lost p53 and Rb expressions are also factors for a poor prognosis, suggesting that mutations in various tumor suppressor genes, including Rb and p16, are not necessarily related to a poor prognosis. However, controversy still exists since different studies have reported different results. As for other cancers, Kusume et al. (12) reported that the abnormal expressions of p16, cyclin D1, CDK4 and pRb are related to a poor prognosis for patients with ovarian cancer. Salvesen et al. (13) reported that loss of the p16 expression is related to a poor prognosis for patients with endometrial cancer. Takeuchi et al. (14) reported that the loss of the p16 expression and cyclin D1 overexpression are related to a poor prognosis for patients with squamous epithelial carcinoma of the esophagus.

Many previous studies have focused on the relationship between sarcomagenesis and G1 arrest change in soft tissue sarcomas. Cohen and Geradts (15) reported that p16 and pRb are related to sarcomagenesis and Meye et al. (6) also reported that p16/CDKN2/MTS1 and p53 related to development of soft tissue sarcoma. Kim et al. (16) found that cyclin D1 is a poor prognostic factor for patients with soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities and within the retroperitoneum, and Wurl et al. (17) stated that positive Rb and p53 expressions are related to a poor prognosis and the prognosis is the worst when genetic abnormality is present in both of these genes.

As for the relationship between Rb and histological differentiation in this study, the histological grades were Grade 1 (29.2%), Grade 2 (24.3%) and Grade 3 (46.3%) in the negative group (less than a 20% positive staining for Rb expression). The histological grades were Grade 2 (60.0%) and Grade 3 (40.0%) in the heterogeneous group (a 20 to 80% positive staining for Rb expression), and Grade 2 (28.6%) and Grade 3 (71.4%) in the homogeneous group (more than 80% positive staining for Rb expression), and this showed a significant difference with a p-value of 0.018. It was shown that Rb mutation was directly related with the histological grades. As for the relationship of Rb with the prognosis, homogeneous group of Rb protiens had poor prognosis (p=0.016). According to the multivariate analysis using Cox's regression analysis, the risk ratio was 3.01, showing a significant difference. The limitation of this study is small number of positive cases of Rb and cyclin D1 mutation. In the future, additional studies with a larger number of samples need to be conducted on the molecular changes related with G1 arrest.

Conclusion

Rb mutation was found to be a significant clinical prognostic factor in this study and we concluded that Rb mutation could be clinically assessed and used as a prognostic factor for soft tissue sarcomas.

References

- 1.Enzinger FM, Weiss SW. Soft tissue tumors. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li XQ, Parkekh SG, Rosenberg AE, Mankin HJ. Assessing prognosis for high-grade soft-tissue sarcomas: search for a marker. Ann Surg Oncol. 1996;3:550–557. doi: 10.1007/BF02306088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yao J, Pollock RE, Lang A, Tan M, Pisters PW, Goodrich D, et al. Infrequent mutation of the p16/MTS1 gene and overexpression of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 in human primary soft-tissue sarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:1065–1070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karpeh MS, Brennan MF, Cance WG, Woodruff JM, Pollack D, Casper ES, et al. Altered patterns of retinoblastoma gene product expression in adult soft-tissue sarcomas. Br J Cancer. 1995;72:986–991. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SH, Lewis JJ, Brennan MF, Woodruff JM, Dudas M, Cordon-Cardo C. Overexpression of cyclin D1 is associated with poor prognosis in extremity soft-tissue sarcomas. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:2377–2382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meye A, Würl P, Hinze R, Berger D, Bache M, Schmidt H, et al. No p16INK4A/CDKN2/MTS1 mutations independent of p53 status in soft tissue sarcomas. J Pathol. 1998;184:14–17. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199801)184:1<14::AID-PATH957>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coindre JM, Trojani M, Contesso G, David M, Rouesse J, Bui NB, et al. Reproducibility of a histopathologic grading system for adult soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer. 1986;58:306–309. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860715)58:2<306::aid-cncr2820580216>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brambilla E, Moro D, Gazzeri S, Brambilla C. Alterations of expression of Rb, p16(INK4A) and cyclin D1 in non-small cell lung carcinoma and their clinical significance. J Pathol. 1999;188:351–360. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199908)188:4<351::AID-PATH385>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang CI, Taki T, Higashiyama M, Kohno N, Miyake M. p16 protein expression is associated with a poor prognosis in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:374–380. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawabuchi B, Moriyama S, Hironaka M, Fujii T, Koike M, Moriyama H, et al. p16 inactivation in small-sized lung adenocarcinoma: its association with poor prognosis. Int J Cancer. 1999;84:49–53. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990219)84:1<49::aid-ijc10>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hommura F, Dosaka-Akita H, Kinoshita I, Mishina T, Hiroumi H, Ogura S, et al. Predictive value of expression of p16INK4A, retinoblastoma and p53 proteins for the prognosis of non-small-cell lung cancers. Br J Cancer. 1999;81:696–701. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kusume T, Tsuda H, Kawabata M, Inoue T, Umesaki N, Suzuki T, et al. The p16-cyclin D1/CDK4-pRb pathway and clinical outcome in epithelial ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:4152–4157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salvesen HB, Das S, Akslen LA. Loss of nuclear p16 protein expression is not associated with promoter methylation but defines a subgroup of aggressive endometrial carcinomas with poor prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:153–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takeuchi H, Ozawa S, Ando N, Shih CH, Koyanagi K, Ueda M, et al. Altered p16/MTS1/CDKN2 and cyclin D1/PRAD-1 gene expression is associated with the prognosis of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:2229–2236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen JA, Geradts J. Loss of RB and MTS1/CDKN2 (p16) expression in human sarcomas. Hum Pathol. 1997;28:893–898. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(97)90003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim SH, Cho NH, Tallini G, Dudas M, Lewis JJ, Cordon-Cardo C. Prognostic role of cyclin D1 in retroperitoneal sarcomas. Cancer. 2001;91:428–434. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010115)91:2<428::aid-cncr1018>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wurl P, Meye A, Lautenschläger C, Schmidt H, Bache M, Kalthoff H, et al. Clinical relevance of pRb and p53 co-overexpression in soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer Lett. 1999;139:159–165. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(99)00034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]