Abstract

Objective

To examine trends over time in parents’ satisfaction with their children’s prior psychiatric hospitalization and whether such trends are related to postdischarge outcomes.

Study Design/Data Collection

Parents of 107 child inpatients completed a satisfaction survey at discharge. Satisfaction with the same inpatient stay was re-assessed 3, 6, and 12 months after discharge. Parents also provided ratings of behavioral symptoms at admission, discharge, and at postdischarge follow-ups.

Principal Findings

Random regression analyses indicated significant decline in satisfaction from discharge to follow-up. The proportion of parents reporting that they were not satisfied doubled between discharge and 3-month follow-up. Parents whose satisfaction appraisals shifted from satisfied at discharge to not satisfied at follow-up also provided mean ratings of their child’s disruptive behavioral problems at follow-up that were higher than those of parents who reported satisfaction with inpatient care at both times.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that appraisals of inpatient care are subject to change, and may become more negative when clinical improvement associated with hospitalization dissipates in the months following discharge.

Keywords: Psychiatric inpatient services, Children, Satisfaction, Outcomes

Introduction

Patient satisfaction is an obviously desirable result of health care (Kertesz, 1996). Under market conditions, economic concerns for patient satisfaction may supplement altruistic ones because providers compete partly on the basis of positive perceptions of care processes and outcomes (Seibert, Strohmeyer, & Carey, 1996). In addition, satisfaction with prior treatment may be an important ingredient in forming patients’ attitudes, beliefs, and expectations toward not only a specific provider but the care process for their condition in general. Although a direct relationship between satisfaction and clinical outcome in mental health treatment seems doubtful (Edlund, Young, Kung, Sherbourne, & Wells, 2003; Garland, Aarons, Hawley, & Hough, 2003; Kaplan, Busner, Chibnall, & Kang, 2001; Lambert, Salzer, & Bickman, 1998), patient satisfaction with an episode of care might influence their expectations of, and perhaps their engagement in, subsequent care (Carlson & Gabriel, 2001; Marquis, Davies, & Ware, 1983)

Psychiatric care may be particularly vulnerable to patients’ negative appraisals of treatment encounters. Psychiatric treatment often requires their tolerance for protracted therapy that may take months to provide significant relief, may fail to produce complete remission of symptoms, may entail periods of relapse, or may incur undesirable side effects. In this context, positive perceptions of providers, effectiveness of treatment and the overall care environment may be instrumental to buoy patients’ and families’ continued involvement in treatment, particularly when initial outcomes are not favorable.

Satisfaction with service is most often evaluated at the time of the encounter or soon after. Advantages of obtaining this information proximate to a service encounter include the freshness of patients’ impressions of their experience and the opportunity for providers to rectify problems the patient identifies (Ford, Bach, & Fottler, 1997). It is not known, however, whether patient or family satisfaction with psychiatric care remains stable or changes over time. A single assessment on the heels of the service may not adequately represent the respondent’s later appraisals, yet subsequent views toward the same service encounter may affect attitudes towards care in general and the provider in particular. Prior studies of adults seen for outpatient medical care suggest that, indeed, satisfaction judgments may change as time elapses from the service encounter (Jackson, Chamberlin, & Kroenke, 2001; Marshall, Hays, Sherbourne, & Wells, 1993). Jackson and colleagues reported that the rates of patients reporting they were fully satisfied with the index visit increased over subsequent inquiries occuring 2 weeks and 3 months later. Their analysis of correlates of reports at these times suggested that actual health outcomes influence reports in the later assessments. There are no reports to date of such longitudinal research on satisfaction with mental health care.

Changes in health status may in effect recalibrate one’s expectations and shift responses about quality of life and satisfaction to a new “set point” (Sprangers & Schwartz, 1999). Most of the literature on such response shift addresses the high quality of life people with chronic debilitating or terminal illness come to endorse over time (Breetvelt & Van Dam, 1991). By the same token, it seems possible that when clinical status markedly improves, a new set point with higher expectations may result.

Applying these findings from general medical care concerning (a) the relationship between outcomes and serial assessments of satisfaction and (b) the response shift phenomenon, there are several reasons to suspect that families’ satisfaction with their children’s inpatient care may be prone to changes over time. At discharge, families may appreciate the improvement in their child’s condition that occurred during hospitalization. Support and understanding of hospital staff may instill in parents optimism that they can cope effectively with their child’s symptoms and treatment needs. After discharge, however, positive feelings may dissipate if the child experiences significant relapse or the strain of caring for a psychiatrically ill youngster eclipses initial optimism. Families may feel that hospitalization had not adequately treated the youngster, or had only temporarily quelled a crisis without being a prelude to the more sustained improvement in functioning for which they may have hoped. Although such a downturn could indicate lapses or deficiencies in postdischarge care, families may nonetheless regard the hospital experience in a more negative light. In other instances, initial dissatisfaction with care may yield to a more positive appraisal if a child’s favorable postdischarge course leads parents to see hospitalization in retrospect as a beneficial turning point.

The measurement of satisfaction, however, has not proved especially straightforward (Crow et al., 2002). Overall global ratings may obscure important subdomains. On the other hand, inquiry about multiple dimensions of the care experience (facilities, specific staff, care environment, etc.) do consider such subdomains, but melding these factors into an unweighted summary score may give undue importance to super-ficial areas at the expense of those more pivotal to the goals of treatment. The pattern of correlation between global and multidimensional approaches has led to the current hierarchical view of patient satisfaction (Marshall et al., 1993), where a direct global measure can provide a valid index of overall attitudes, and domain-specific scales can better detect distinct areas needing improvement.

To examine potential trends in parental satisfaction with inpatient care over time, the present study examined reports of satisfaction obtained at four occasions, at discharge then 3, 6, and 12 months after discharge. The consistently high correlation between global measures of satisfaction and other indices led to focus on a global satisfaction measure for this purpose. A global measure is also more amenable to a parsimonious analytic approach than are the numerous domains of a multidimensional assessment.

Method

Subjects

Caregivers of 107 children discharged over a 14-month period from a 15-bed acute inpatient psychiatric service, housed within a general pediatric hospital, provided the satisfaction and clinical outcome data for this report. This clinical site drew patients from a major U.S. city and its adjacent suburbs. Derivation of the sample from the total number of patients admitted during this period is described elsewhere (Blader, 2004). The overall consent rate was 64%; 10% declined, 10% were discharged precipitously after very short stays (< 2 days), and 15% of the children were with foster care agencies that did not provide consent promptly enough to obtain follow-up data.

The children’s average age at admission was 9.50 years (SD 2.12, range 5.1–13.6 years), 78.5% were male, and ethnicity was diverse (50% white, 36% African-American, 10% Hispanic, and 4% mixed heritage). Informants were the biological parents of 67% of the children, adoptive parents of 13%, grandparents of 12%, and were unrelated foster parents for 8%. A disruptive behavior disorder along with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder was the most common principal diagnostic combination (80%), and occurred comorbidly with mood disorders among 34% of the sample, with anxiety disorders for 8%, and a pervasive developmental disorder (PDD) for 10%. Other principal diagnoses were major depression (10%), PDD (5%), and psychotic disorder for 4%. The only difference between participants and the total patient population during the recruitment period was the smaller proportion of children in foster care (9%) among participants than among the whole cohort of admittees (22%).

Measures and Data Sources

Satisfaction Ratings

At the time of discharge, inpatient staff asked the child’s caregiver to complete the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8 (CSQ-8) (Attkisson & Zwick, 1982), This instrument comprises eight items that respondents rate on a 1–5 scale. Item content addresses the quality and appropriateness of service received and the likelihood that the informant would return should the need arise. Principal components analysis of this sample’s responses on this questionnaire yielded a one-factor solution (eigenvalue = 5.90).

One item, Overall Satisfaction, asked parents to rate their response to the question, “In a general sense, how satisfied are you with the service you received?” as Very Satisfied (1), Satisfied (2), Neither (3), Dissatisfied (4) and Very Dissatisfied (5). This item had the highest loading on the scale’s unitary factor (0.90). We readministered this item during postdischarge follow-up interviews, adding the phrase “…during your child’s hospitalization?” at the end for clarity, to furnish a succinct measure of satisfaction with prior inpatient care at 3, 6, and 12 months after discharge. The high association between this item and the total score suggests that re-administration of the full CSQ-8 likely would have had minimal impact on the findings reported.

Because satisfaction ratings generally skew toward a high proportion of positive responses, we dichotomized responses on the Overall Satisfaction item by combining the neutral response (3) with the two levels of dissatisfaction (4 and 5), to yield Satisfied and Not Satisfied categories. Analysis of dichotomized satisfaction ratings focuses attention on qualitative shifts in attitude toward care, and precludes statistically significant but questionably important findings resulting from shifts between modifiers (e.g., from “Very Satisfied” to “Satisfied”).

Telephone interviews also inquired about current services, and we recorded utilization of psychotherapy (child and/or family) and pharmacotherapy.

Clinical Outcome

Interest in the relationship between temporal trends in satisfaction ratings and clinical outcomes necessitated measurement of the child’s symptom severity at admission and follow-up. Parents completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach, 1991) at the child’s admission, discharge, and postdischarge follow-ups. The CBCL Total Problems score provides a global measure of symptom severity. The Externalizing Problems score indicates severity of disruptive, aggressive and other dyscontrolled behavior, which is the chief reason for hospitalization in this patient group. The Internalizing Problems score reflects the magnitude of symptoms of anxiety, depression, and social withdrawal.

Procedures

Families or guardians obtained a written description of the study at admission. At discharge, research staff fully described the requirements of participation, answered questions, and offered families the opportunity to participate. If caregivers wished to do so and gave written informed consent, and children over age 8 gave their assent, the family was enrolled. Institutional review boards at the clinical site and the university that employed the researchers approved the study.

The child’s hospital record was the source for demographic data and CBCL scores from admission. A staff nurse routinely gave the CSQ-8 to all families, whether participants in this study or not, to complete privately. Research staff made a de-anonymized copy of those completed by study participants. Research staff asked parents enrolling in this study to complete the CBCL at discharge.

Participants were contacted for follow-up at 3, 6, and 12 months after discharge. Satisfaction ratings were obtained during a telephone interview that inquired about the child and family’s aftercare services. After this interview, parents received the CBCL by mail to complete and return by mail. In 17 instances, we did not receive questionnaire data within 1 month of the telephone interview, leading to missing data for the analyses examining outcome and satisfaction reports.

Data Analysis

The main effect of time on the dichotomous outcome of satisfaction (i.e., whether parents reported satisfaction or not with inpatient care) was evaluated by mixed-effects logistic (random) regression using the MIXNO program by Hedeker (Hedeker, 1999). Separate models assessed quadratic-plus-linear and linear-only functions for the time effect.

We then compared the demographics and clinical courses of children whose parents reported changes in their satisfaction from discharge to follow-up with those whose parental satisfaction was stable. χ2 tests evaluated differences between these parent groups for categorical variables, and analyses of variance evaluated differences between parent groups on continuous measures.

Results

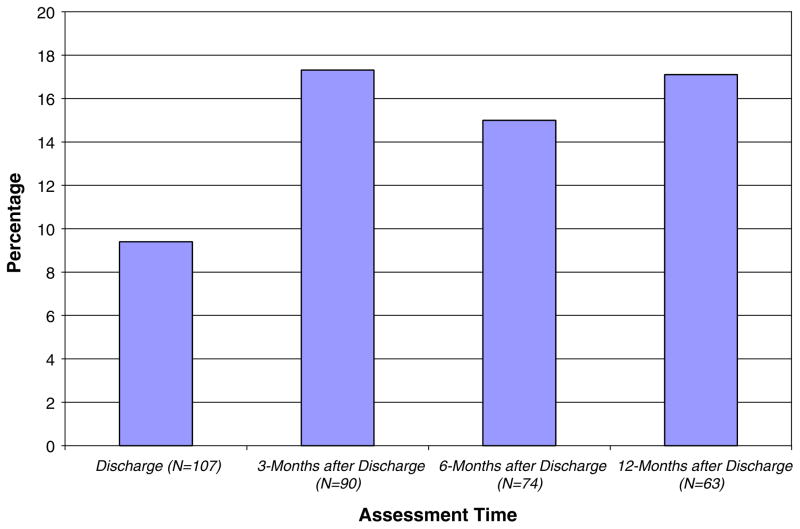

Figure 1 shows the proportion of parents who reported being not satisfied with their child’s inpatient stay across assessment times.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of parents not satisfied with inpatient care over time

Analyses of the effect of time revealed a significant quadratic effect (B = 1.15; z = 2.33, P < 0.02) along with a linear effect (B = −1.88; z = −3.97, P < 0.02). The model with a quadratic effect was superior to the model without it (change in log likelihood = 94.48, χ2Δ in log likelihood [1] = 94.48. P < 0.001). A steep increase in the rate of parent-reported being not satisfied occurred between the discharge assessment and the first postdischarge follow-up with little change at subsequent follow-ups. A number of parents who provided satisfaction ratings at discharge did not furnish ratings at the 3-month follow-up; however, the random-effects regression model enables inclusion of all available data to estimate trends over time (Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992).

Table 1 presents the prevalence in this sample of concordance and change between the satisfaction ratings obtained at discharge and those obtained at 3-month follow-up. Changes in satisfaction were almost exclusively in the direction of becoming more negative. Table 1 also shows the number of parents who provided satisfaction ratings at discharge but subsequently declined to participate in the follow-up, although they consented to be contacted. Of the total with missing follow-up data, 36% expressed nonsatisfaction at discharge, a proportion far in excess of the 5% nonsatisfied rate among parents who also provided follow-up data (Fisher’s two-tailed exact test = 0.002).

Table 1.

Prevalence of stability and changes in satisfaction between discharge and 3-month follow-up

| Satisfaction status |

Prevalence |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classification | Discharge | Follow-up | Proportion | N | |

| Remained satisfied | = | Satisfied | Satisfied | 63.73% | 68 |

| Remained not satisfied | = | Not satisfied | Not satisfied | 1.96% | 2 |

| Shifted to not satisfied | = | Satisfied | Not satisfied | 18.63% | 20 |

| Shifted to satisfied | = | Not satisfied | Satisfied | 1.96% | 2 |

| Satisfied at discharge, no follow-up | = | Satisfied | No follow-up | 8.82% | 9 |

| Not satisfied at discharge, no follow-up | = | Not satisfied | No follow-up | 4.90% | 5 |

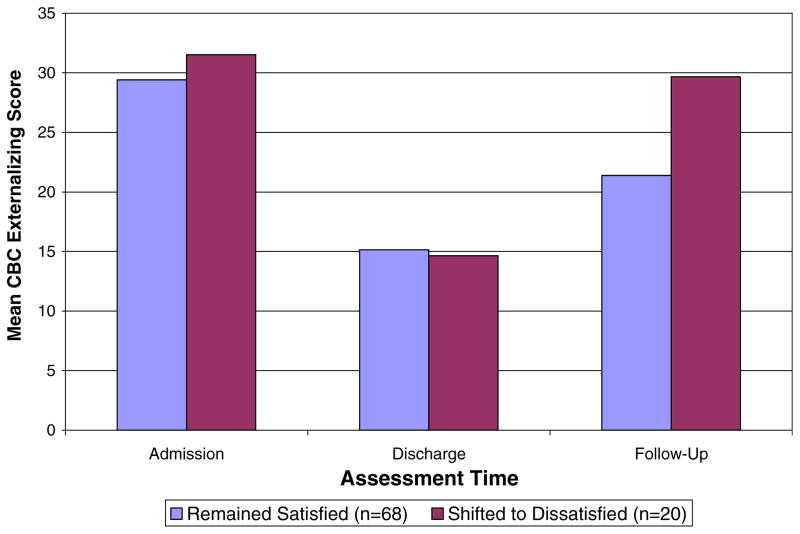

To examine if outcomes differed between parents whose satisfaction remained positive and parents whose satisfaction report converted to negative in the follow-up period, mixed-model regression compared CBCL scores at 3-month follow-up between these groups. As depicted in Fig. 2, parents who shifted from satisfied at discharge to nonsatisfied at follow-up provided significantly higher ratings of their children’s externalizing behavioral problems at 3-month follow-up (F [1, 70] = 4.25, P < 0.05). The reduction in CBCL Externalizing scores from admission to discharge for the entire group is highly significant when tested with repeated-measures analysis of variance (F [1, 79] = 72.9, P < 0.001). Internalizing and CBCL Total Problem scores were not significantly different between the groups.

Fig. 2.

CBCL externalizing behavior raw scores from parents reporting satisfaction with inpatient care at discharge and 3-month follow-up and from parents whose satisfaction report became negative at follow-up

There were no significant differences between satisfied and not satisfied parents at discharge or follow-up assessments with respect to their children’s age, ethnicity, length of stay, previous hospitalization, placement prior to admission (in or out of home), or payer (commercial insurer vs. Medicaid).

With respect to postdischarge psychiatric care, 61% of the sample reported current involvement in both family therapy and individual psychotherapy for their child at 3-month follow-up, 19% reported child individual psychotherapy only, and 8% family therapy only. A total of 91% reported receipt of pharmacotherapy at follow-up. Use of these services bore no association with satisfaction ratings or with their change over time.

Discussion

This study’s findings indicate the importance of longitudinal assessments as a potential key to understanding the relationships between families’ appraisals of clinical care and outcomes. In this study, parents reported high rates of satisfaction toward care providers after a service that culminated in their child’s improved condition. However, for an appreciable number of parents, the sheen tarnished, and parents who changed their appraisal from satisfied at discharge to not satisfied at follow-up reported, on average, higher ratings of child behavioral difficulties at follow-up.

It is not surprising that externalizing behavior was the principal outcome to show deterioration among children whose parents’ satisfaction ratings shifted from satisfied at discharge to not satisfied at follow-up. Aggressive behavior is the most common chief complaint and reason for hospitalization in this age group, cutting across specific diagnoses, and is strongly linked to risk for further admissions (Blader, 2004; Gutterman, 1998).

Previous research on patient satisfaction and outcomes in mental health, while extensive, has not taken a longitudinal approach. However, repeated assessments can clarify some of the associations that cross-sectional measurement of patient-reported satisfaction and outcomes reveal. A survey of hospitalized adults assessed satisfaction with inpatient care during the trimester after discharge (Druss, Rosenheck, & Stolar, 1999). Higher satisfaction with inpatient services correlated with involvement in postdischarge treatment and fewer readmissions. One could infer from these findings that positive perceptions of inpatient experience increase the likelihood of favorable outcomes. The present study would have furnished similar results if satisfaction ratings at discharge were not available. However, the fact that parents who shifted from satisfied at discharge to not satisfied at follow-up reported more behavioral disturbance at follow-up suggests that outcomes may influence perceptions of prior service, in this case toward a less favorable view of the inpatient care setting.

Similarly, an examination of satisfaction and outcomes for the mental health care of the dependents of U.S. armed service members revealed significant correlations between parent-reported improvement and satisfaction (Lambert et al., 1998). However, because there was no association between parental satisfaction and a composite index of clinical improvement which incorporated a rater, the authors concluded that parental assessments of improvement are actually byproduct of their overall satisfaction with care encounters. This study’s use of serial assessments raises the possibility that satisfaction may track symptomatic change, particularly when initially good outcome shows subsequent decline. This pattern is consistent with the ‘response shift’ phenomenon (Sprangers & Schwartz, 1999), in which changes in health status can modify one’s reference point for subsequent appraisals of well-being or satisfaction.

Other studies of children’s services that examined satisfaction among parents of impatient (Bradley & Clark, 1993; Kaplan et al., 2001) and outpatient youth (Garland et al., 2003) also reported modest relationships between single measurements of satisfaction and outcome. The current study extends this line of research considering longitudinal trends in both satisfaction and clinical outcome.

Although this study asked parents to reflect on their child’s earlier inpatient treatment, outpatient treatment after discharge seems likely to exert a more proximal effect on outcome than prior hospitalization. Parents’ reports of their use of child psychiatric out-patient services did not correlate with satisfaction ratings. However, more refined assessment of postdischarge services could enable analyses of the relationship between outpatient care and re-appraisals of the prior inpatient stay.

Limited power may have diminished this study’s ability to detect an association between demographic, clinical, or service use factors that may be relevant to satisfaction. However, similar or larger samples involving both youth and adults have not reported such effects either (Bradley & Clark, 1993; Edlund et al., 2003; Garland et al., 2003; Gerber & Prince, 1999; Kaplan et al., 2001; Kotsopoulos, Elwood, & Oke, 1989). At least one adult study, though, adjusted for such variables but did not specify the impact they may have had on satisfaction ratings (Druss et al., 1999).

About one-third of parents who did not provide follow-up data (5 of 14) expressed nonsatisfaction with care at discharge. Although small numbers caution against overinterpretation, displeased parents may be less likely to participate in subsequent efforts to assess children’s outcomes and family’s views toward care. Another 10% of the total group of children admitted left hospital soon after admission. The most common reason for precipitous discharge involved insurers’ declining further care, but some parents may have withdrawn their children because of displeasure with the unit. Fully taking these possibilities into account represents an important methodological hurdle to examining trends in attitudes and outcomes over time.

This study ascertained satisfaction ratings under different conditions at discharge compared with the postdischarge assessments. A nurse requested ratings at discharge via questionnaire, while a researcher obtained ratings at follow-up via telephone. This leaves open the possibility that apparent shifts in satisfaction were just the “unmasking” of sentiments present at discharge but which parents found easier to express later on to someone uninvolved in their child’s care. On the other hand, interviews tend to yield more positively biased data relative to questionnaires (Crow et al., 2002, p. 31), which militates somewhat against the interpretation that our findings of greater negativity during telephone interview represent method artifact. Nonetheless, these possibilities have implications for the measurement of satisfaction more broadly in mental health that have not yet been examined, and, in any case, would have been much more difficult to detect without longitudinal data.

The changes over time we found here may not readily generalize to other mental health settings, especially where adults are reporting on their own care. Family members are more apt to disclose less satisfaction with medical care than are patients themselves (Crow et al., 2002, p. 25), so a different pattern of results may well emerge when the patient is the informant.

In addition to its longitudinal methodology, this study has two other noteworthy features. It provides data on parental appraisals of the inpatient care of children, an area of little prior study relative to the larger literature on adult satisfaction with mental health care. Second, while previous studies analyzed satisfaction ratings as a continuous measure, this study categorized responses as satisfied or not satisfied. Doing so enabled a more straightforward interpretation of the data than a change in means of a continuous scale might have afforded, and avoided the pitfalls of parametric analyses with a variable whose distribution is usually highly skewed. On the other hand, our use of a single question may represent a shortcoming to the extent that satisfaction may have subdomains that could warrant attention. Assessment of satisfaction with specific aspects of services may have differentiated elements most likely to shows changes in appraisal over time, such as satisfaction with treatment effectiveness, provider competence, the care environment, etc. (Holcomb, Parker, Leong, Thiele, & Higdon, 1998). However, overall satisfaction appears to be the best predictor of the likelihood that one will re-use or recommend a service (Fisk, Brown, Cannizzaro, & Naftal, 1990; Kolb, Race, & Seibert, 2000).

We noted at the outset that satisfaction with care may be an important influence on engagement with treatment and perhaps on optimism about coping with a chronic psychiatric disorder. This study suggests that further research to address this issue could be optimized by a longitudinal perspective which recognizes that appraisal of care may not be static.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants to the author from the National Institutes of Health (R03MH058456 and K23MH064975).

References

- Achenbach TM. Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR and TRF profiles. Burlington VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Attkisson C, Zwick R. The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire. Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1982;5:233–237. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(82)90074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blader JC. Symptom, family, and service predictors of children’s psychiatric rehospitalization within one year of discharge. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:440–451. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley E, Clark B. Patients’ characteristics and consumer satisfaction on an inpatient child psychiatric unit. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;38:175–180. doi: 10.1177/070674379303800304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breetvelt IS, Van Dam FS. Underreporting by cancer patients: The case of response shift. Social Science and Medicine. 1991;32:981–987. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical linear models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M, Gabriel R. Patient satisfaction, use of services, and one-year outcomes in publicly funded substance abuse treatment. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:1230–1236. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.9.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow R, Gage H, Hampson S, Hart J, Kimber A, Storey L, et al. The measurement of satisfaction with healthcare: Implications for practice from a systematic review of the literature. Health Technology Assessment. 2002;6(32):1–244. doi: 10.3310/hta6320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Stolar M. Patient satisfaction and administrative measures as indicators of the quality of mental health care. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50:1053–1058. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.8.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlund MJ, Young AS, Kung FY, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. Does satisfaction reflect the technical quality of mental health care? Health Services Research. 2003;38(2):631–645. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisk TA, Brown CJ, Cannizzaro KG, Naftal B. Creating patient satisfaction and loyalty. Journal of Health Care Marketing. 1990;10:5–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford RC, Bach SA, Fottler MD. Methods of measuring patient satisfaction in health care organizations. Health Care Management Review. 1997;22(2):74–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Aarons GA, Hawley KM, Hough RL. Relationship of youth satisfaction with mental health services and changes in symptoms and functioning. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54:1544–1546. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.11.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber G, Prince P. Measuring client satisfaction with assertive community treatment. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50:546–550. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.4.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutterman EM. Is diagnosis relevant in the hospitalization of potentially dangerous children and adolescents? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:1030–1037. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199810000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D. MIXNO: A computer program for mixed-effects nominal logistic regression. Journal of Statistical Software. 1999;4(5):1–92. [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb W, Parker J, Leong G, Thiele J, Higdon J. Customer satisfaction and self-reported treatment outcomes among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatric Services. 1998;49:929–934. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.7.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JL, Chamberlin J, Kroenke K. Predictors of patient satisfaction. Social Science and Medicine. 2001;52:609–620. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan S, Busner J, Chibnall J, Kang G. Consumer satisfaction at a child and adolescent state psychiatric hospital. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:202–206. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz L. Patient is king. Studies define customers’ satisfaction and the means to improve it. Modern Healthcare. 1996;26(18):107–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb SJ, Race KEH, Seibert JH. Psychometric evaluation of an inpatient psychiatric care consumer satisfaction survey. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 2000;27:75–86. doi: 10.1007/BF02287805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotsopoulos S, Elwood S, Oke L. Parent satisfaction in a child psychiatric service. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1989;34:530–533. doi: 10.1177/070674378903400609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert W, Salzer MS, Bickman L. Clinical outcome, consumer satisfaction, and ad hoc ratings of improvement in children’s mental health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:270–279. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquis MS, Davies AR, Ware JE. Patient satisfaction and change in medical care provider: A longitudinal study. Medical Care. 1983;21:821–829. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198308000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall GN, Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. The structure of patient satisfaction with outpatient medical care. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5:477–483. [Google Scholar]

- Seibert JH, Strohmeyer JM, Carey RG. Evaluating the physician office visit: In pursuit of a valid and reliable measure of quality improvement efforts. Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 1996;19:17–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprangers MAG, Schwartz C. Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: A theoretical model. Social Science and Medicine. 1999;48:1507–1515. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]