ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE

To examine the effects of advanced access (same-day physician appointments) on patient and provider satisfaction and to determine its association with other variables such as physician income and patient emergency department use.

DESIGN

Patient satisfaction survey and semistructured interviews with physicians and support staff; analysis of physician medical insurance billings and patient emergency department visits.

SETTING

Cape Breton, NS.

PARTICIPANTS

Patients, physicians, and support staff of 3 comparable family physician practices that had not implemented advanced access and an established advanced access practice.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

Self-reported provider and patient satisfaction, physician office income, and patients’ emergency department use.

RESULTS

The key benefits of implementation of advanced access were an increase in provider and patient satisfaction levels, same or greater physician office income, and fewer less urgent (triage level 4) and nonurgent (triage level 5) emergency department visits by patients.

CONCLUSION

Currently within the Central Cape Breton Region, 33% of patients wait 4 or more days for urgent appointments. Findings from this study can be used to enhance primary care physician practice redesign. This research supports many benefits of transitioning to an advanced access model of patient booking.

RÉSUMÉ

OBJECTIF

Examiner les effets d’un accès rapide (rendez-vous avec le médecin le jour même) sur la satisfaction des patients et des soignants, et déterminer si cela influence d’autres variables telles le revenu du médecin et le recours aux départements d’urgence.

TYPE D’ÉTUDE

Enquête sur la satisfaction des patients et entrevues semi-structurées avec les médecins et le personnel du bureau; analyse de la facturation du médecin à l’assurance maladie; et nombre de visites des patients aux services des urgences.

CONTEXTE

Cap Breton, Nouvelle-Écosse.

PARTICIPANTS

Patients, médecins et personnel de soutien de trois cliniques de médecine familiale comparables qui n’avaient pas instauré l’accès rapide et n’utilisaient pas déjà ce mode de pratique.

PRINCIPAUX PARAMÈTRES À L’ÉTUDE

Degré de satisfaction déclarée par les soignants et les patients, revenu de bureau des médecins et utilisation des services des urgences par les patients.

RÉSULTATS

Les avantages principaux de l’instauration d’un accès rapide au médecin étaient une augmentation du degré de satisfaction des soignants et des patients, un revenu égal ou augmenté pour le médecin et moins de visites des patients aux services des urgences pour des conditions moins urgentes (niveau 4 au triage) et non urgentes (niveau 5 au triage).

CONCLUSION

Présentement, dans la région centrale du Cap Breton, 33 % des patients attendent au moins 4 jours pour un rendez-vous urgent. Les données de cette étude devraient promouvoir des changements dans la pratique des médecins de première ligne. Cette étude indique qu’il y a beaucoup d’avantages à instaurer un tel mode d’accès rapide pour la prise de rendez-vous.

Wait times are a current concern for Canadians, with timely access to physicians becoming increasingly important from a system perspective. In many communities, patients are forced into emergency departments (EDs) for their primary care because of the long delay to see their physicians. Practice redesign holds promise for addressing the issue of wait times and access to high-quality primary care.1 Reports suggest that transitioning from traditional booking to advanced access patient booking systems can lead to elimination of patient backlog, fewer no-show appointments, patient satisfaction, stability in office income, and increased satisfaction for physicians, practice nurses, and other office staff.2–4

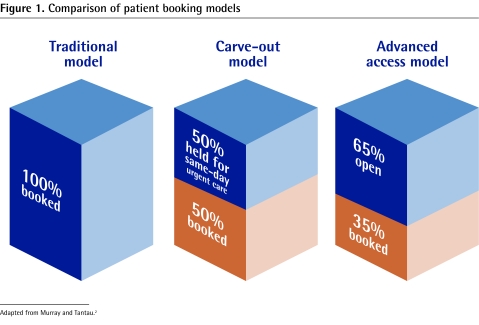

This research project aimed to examine the effects of same-day physician appointments on patient and provider satisfaction; physician income, as measured by quarterly physician office income; and nonurgent ED visits by patients, as reported by the Nova Scotia Health Information System.5 Practices can handle patient booking in a variety of ways, as illustrated in Figure 1.2 Advanced access patient booking shifts the balance so that most patients are booked the same day they call for appointments. This appointment scheme provides a patient-centred approach to appointment booking, with possible challenges and benefits to patients, office staff, and primary care physicians.6,7

Figure 1.

Comparison of patient booking models

Adapted from Murray and Tantau.2

Access to family physician office appointments and nonurgent use of EDs are important wait-time and chronic disease management concerns. Examples of advanced access redesigns from the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada demonstrate the effectiveness of the booking system.8–12 There are clear steps presented by the authors of these studies to the redesign of practice, and both qualitative and quantitative research findings support such redesign. There is some concern about potential risks in redesign. The shift to advanced access booking needs to consider the practice’s specific characteristics, such as patient load and demographic makeup.8,12 Some patients prefer booked appointments, and some cases require pre-booked management. These concerns highlight the importance of transitioning patient booking in ways that match the practice, guided by the primary care physician and the office staff.

A number of concerns might be addressed through an advanced access model of patient booking.13 The primary benefit reported is a reduction in wait times for access to primary care. But practical reviews suggest that advanced access models do more than reduce the amount of time spent waiting to see general practitioners. Transition to advanced access booking might also lead to improved productivity, care quality, and revenue.14,15 Even though many Canadian patients do prefer to see their family physicians during regular hours for routine care, large proportions of these patients visit EDs for minor emergent care. The use of emergency services for emergent care is higher in countries with lower access to same-day booking. Canada has higher rates of such ED use than the United Kingdom and the United States do.9

A recent study by the Cape Breton District Health Authority Primary Care Initiative demonstrated that among those patients expressing some difficulty in obtaining primary care services, trouble accessing the services of a general practitioner was identified most often. Forty-three percent of respondents indicated they had such difficulty booking appointments for primary care.10 Further, 74% of respondents within the Cape Breton Central Community Health Board reported that if they had a serious but not life-threatening condition they would go to the ED, whereas only 22% would call their family physicians. Most reported going to the ED because either their physicians did not set aside appointments for urgent needs or it was more convenient. Currently within Central Cape Breton Region, 33% of patients wait 4 or more days for an urgent appointment.10 Access to primary health care through a regular provider was identified by the Canadian Institute for Health Information in 2006 as a key indicator category in the measurement of primary care progress.16 Nationally and internationally, advanced access is under consideration or is being integrated. Accessibility is 1 of 4 national primary health care pillars.17 Advanced access to primary care has been pioneered in the United States and later adopted, refined, and studied in United Kingdom.11 In Canada the use of advanced access is emerging in community health centres and community clinics.12 It is unknown how many physicians in Canada are using an advanced access system of booking. This research initiates exploration of access to primary care through general practitioners. We hypothesized that an advanced access redesign would provide higher levels of provider and patient satisfaction, the same or greater office income, and a reduced number of nonurgent ED visits by practice patients.

METHODS

Practices included in this study were purposefully selected to be comparable. All physician offices included in this research were from the same geographic area. They were solo, fee-for-service, comprehensive practices with 1 to 4 staff; 3 used traditional booking models and 1 was an established advanced access practice. The patient populations of the practices surveyed were representative of the population of Cape Breton as presented in Table 1. Because this was action-based research with a qualitative component, it was not possible to blind researchers to the practices being reviewed. Mixed methods were used for this investigation. The variables of interest for quantitative investigation were office income, nonurgent ED use, and patient satisfaction.

Table 1.

Central Cape Breton County 2006 census data

| AGE GROUP | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Preschool (< 5 y) | 1872 (4.1) |

| Elementary (5–19 y) | 8016 (17.7) |

| 20–34 y | 6994 (15.5) |

| 35–54 y | 13 653 (30.2) |

| 55–64 y | 6650 (14.7) |

| 65–74 y | 4100 (9.1) |

| ≥75 y | 4188 (9.3) |

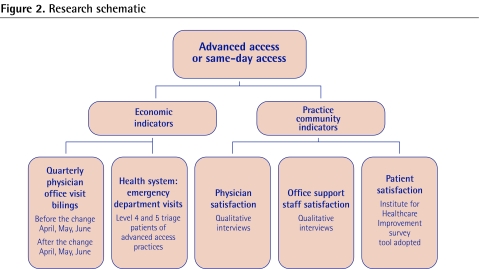

Qualitative variables of interest were office personnel satisfaction with and attitudes toward their appointment booking systems. Interviews were structured based on the theory of planned behaviour.18,19 The research structure is summarized in Figure 2. Interviews were developed from the perspective of action-based research, based on the experience of an advanced access physician. Support for this approach came from Ahluwalia and Offredy in 2005.20

Figure 2.

Research schematic

Patient satisfaction surveys were collected from 1 advanced access practice and 3 practices that were not advanced access, with the surveys distributed each month for a 3-month period. This procedure resulted in 117 surveys collected from patients in the advanced access booking practice and 207 from more traditional booking practices.

As outlined in Figure 2, economic indicators included quarterly physician billing for the months of April, May, and June in the study year and in the previous year within the same practice. Most of these billings were for office visits and ED visits by practice patients at triage level 4 or 5, corresponding to less urgent and nonurgent need. Physicians consented to having this information released for analysis. The practice community was examined with qualitative interviews with physicians and the office staff. Quantitative information was collected directly from patients to assess their satisfaction with booking practices. Additional detail is provided on the quantitative and qualitative methods in the appropriate sections to follow. This research was approved by the Cape Breton University Research Ethics Board.

RESULTS

The results of this study are reported in 3 sections. The first section includes economic results, including both office income and ED visits. This is a case comparison within the advanced access practice before and after implementation of advanced access. These results affect the office economics directly or indirectly. Both of these categories also have possible effects on health care costs and service. Next, the qualitative results in terms of satisfaction are reported. These results are interpretations of the qualitative interviews of physicians and office staff. Finally, quantitative results from the satisfaction surveys are presented. These latter 2 sections report comparisons between the advanced access practice and the 3 more traditional booking practices.

Economics

Office revenue

After provincial fee increases were factored in, a 7% increase in revenue was reported in the 3-month period of April, May, and June in the year following transition to advanced access booking, compared with the same 3 months of the previous year. When asked about this more directly in qualitative follow-up, participants suggested that dealing with today’s health problems allowed for more efficient visits. Participants reported that there were fewer no-show appointments. Qualitative interpretations suggest that less physician time was spent triaging and prioritizing to determine which patients would be seen the same day. All of these factors allowed for the maintenance of office income with possible increases. Opportunities were opened up for enhanced chronic disease prevention and management. Staff resources could be redirected to high-quality, efficient patient care rather than the physician and staff triaging appointments and handling patient concerns and complaints.

Emergency department visits

Following transition to advanced access there was a 28% reduction in triage level 4 and 5 visits to the local EDs by patients of the practice. This resulted in less revenue being diverted from the practice. It was also suggested that this promoted continuity of care because patients were seen by their family physician rather than by ED physicians or walk-in clinic staff. Early presentation of illness was made to the family physician rather than to the ED. From a system perspective this also contributes to reduction in ED crowding because patients with minor ailments can and do get in to see their family doctors so are not forced to go to the ED.

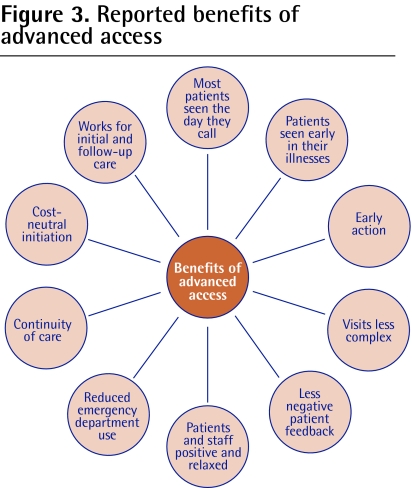

Qualitative satisfaction

Semistructured interviews were conducted in 4 general practices with physicians, practice nurses, and office staff. Benefits noted by informants are outlined in Figure 3. Minimal difficulties with transition were reported. In addition, comments on critical roles, the flexibility of advanced access booking, revenue, efficiency, and the transition from traditional booking to advanced access booking were revealed.

Figure 3.

Reported benefits of advanced access

Patient satisfaction surveys

Patient surveys in the practice that had transitioned to advanced access began with 2 questions comparing overall satisfaction before and after the transition to advanced access booking. The t test mean demonstrated close to a 1-point change in satisfaction measured on a 5-point scale. The significance level for change satisfaction was P < .05, which allows us to conclude that the change was not due to chance variation and can be attributed to the change in booking procedures.

Comparison between responses of patients from advanced access practices and traditional booking practices to 4 questions relevant to patient satisfaction was also conducted. These results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patient satisfaction results for the comparison between advanced access and traditional booking practices: Responses were based on a 5-point Likert scale.

| QUESTION | T | DF | P VALUE (2-TAILED) | MEAN DIFFERENCE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How satisfied are you with the current appointment booking at this office? | 4.136 | 158.985 | < .001 | 0.39 |

| How would you rate the length of time you waited to get this appointment? | 2.597 | 166.674 | .01 | 0.26 |

| How would you rate the length of time waiting during today’s visit? | 5.016 | 443 | < .001 | 0.51 |

| How would you rate a recent experience getting through to this office by telephone? | 3.298 | 444 | .001 | 0.34 |

Based on the Levene test for equity of variance and the above t test for equity of means, we can conclude that there is a significant difference in satisfaction among the patients of the advanced access practice compared with those from traditional booking practices.21

DISCUSSION

In this study we made efforts to include both practices with traditional booking systems and advanced access practices. Reflecting on the study practices suggests that these 2 categories are not dichotomous. Individual practices have individual solutions for creating efficient booking of patient visits. The qualitative interviews strongly supported an advanced access model for solo practices. Concerns about the transition to advanced access booking that were expressed by traditional practice providers were not identified by advanced access practitioners. Advance access booking provides both economic and satisfaction benefits with few drawbacks. The transition time, which was referred to by some informants as “Boot Camp,” deserves further investigation. Discovering ways to facilitate this with minimal stress could reduce this as a barrier to change. The tendency to slide back to pre-booking is a second possible drawback. Awareness of this possibility and provision of the support to avoid such reversal also deserve further investigation.

The roles of the physician, practice nurses, and office staff in relation to appointment booking processes were a specific focus of this research. The physician was the initiator and maintainer of the change. In addition, physicians believed they had a responsibility to monitor the medical consequences of booking practices. Practice nurses suggested that advanced access booking allowed them to focus on nursing rather than the booking of patients and time on the telephone.

Both the qualitative and quantitative data support advance access booking as a flexible structure allowing patients, office staff, and physicians to balance the demands on their professional and personal time. This research also supports economic advantages to advanced access booking. Reductions in ED use following a transition to advanced access booking were suggested in both qualitative and quantitative analysis. Following transition, office income is expected to increase or at least remain neutral. This study demonstrates a trend in a single practice that is supported by study in different situations indicating positive economic indicators following transition to advanced access booking.

Limitations

This research has limitations. The practices that engaged in interviews and patient satisfaction surveys were already motivated to provide high-quality patient care. In this research it was challenging to involve practices with long wait times. In addition, the number of practices involved was small. A good next step would be to involve practices interested in transitioning to advanced access booking. Understanding the motivation to change booking practices or to stay with a traditional booking model would also provide valuable information.

Conclusion

Further research should consider exploring incentives in the Canadian context to change office booking practices. Patient-centred booking systems such as advanced access are driven by the needs of patients. It is difficult to determine what type of patients might benefit most from advanced access booking. Such booking practices might have a tendency to balance the playing field for patients. This perception should be looked at in more detail. Also, examination of what facilitators can be put in place to assist physician office appointment redesign is warranted. Offices that have transitioned to advance access booking have high levels of satisfaction among both the office staff and patients. Dissemination of such findings to the medical community and decision makers is a critical next step to promoting transition to what seems to be an efficient patient-centred gateway to primary care. Good sources of information for physicians or practice managers considering practice redesign are available for review.12,22 Such change might be well worth the investment of time and effort.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Cape Breton Health Research Centre for the funding that assisted with this research.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Wait times are a current concern for Canadians, with timely access to physicians becoming increasingly important from a system perspective. In many communities, patients are forced into emergency departments for their primary care because of the long delay to see their physicians.

Reports suggest that transitioning from traditional booking to advanced access booking can lead to elimination of patient backlog, fewer no-show appointments, patient satisfaction, stability in office income, and increased satisfaction for physicians, practice nurses, and other office staff. This project sought to examine the effects of same-day physician appointments on patient and provider satisfaction, physician income as measured by quarterly physician office visit income, and nonurgent emergency department visits by patients.

Advance access booking provides both economic and satisfaction benefits with few drawbacks. Both the qualitative and quantitative data support advance access booking as a flexible structure allowing patients, office staff, and physicians to balance the demands on their professional and personal time.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Le temps d’attente est un problème courant au Canada, l’accès aux médecins en temps opportun étant une question de plus en plus importante pour le système de santé. Dans plusieurs collectivités, les patients doivent recourir aux services des urgences pour des soins primaires en raison des longs délais pour voir leur médecin.

Certains rapports suggèrent qu’en passant du mode habituel de prise de rendez-vous à un accès rapide (rendez-vous le jour même), on pourrait éliminer l’accumulation des patients en attente, réduire le nombre de rendez-vous manqués, stabiliser le revenu du bureau et augmenter la satisfaction des patients, des médecins, des infirmières praticiennes et des autres membres du personnel. Ce projet voulait vérifier les effets d’un accès au médecin le jour même sur la satisfaction du patient et du soignant, sur le revenu du médecin mesuré par le revenu trimestriel provenant des visites à son bureau et sur le nombre de visites non urgentes des patients aux services des urgences.

La prise de rendez-vous pour le jour même est avantageuse sur le plan économique et améliore la satisfaction, avec peu d’inconvénients. Les données tant qualitatives que quantitatives indiquent que l’accès rapide au médecin est une mesure flexible qui permet au patient, au personnel du bureau et au médecin de mieux partager leur temps entre les activités professionnelles et personnelles.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributors

All the authors contributed to concept and design of the study; data gathering, analysis, and interpretation; and preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.College of Family Physicians of Canada . When the clock starts ticking. Wait times in primary care. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2006. Available from: www.cfpc.ca/local/files/Communications/Wait_Times_Oct06_Eng.pdf. Accessed 2009 Oct 27. [Discussion paper] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray M, Tantau C. Same-day appointments: exploding the access paradigm. Fam Pract Manag. 2000;7(8):45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell V. Same-day booking. Success in a Canadian family practice. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:379–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canadian Health Services Research Foundation . How advanced access is reducing wait times in Cape Breton. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Health Services Research Foundation; 2009. Available from: http://28784.vws.magma.ca/promising/html/pp25_e.php. Accessed 2009 Oct 27. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nova Scotia Hospital Information System [website] Halifax, NS: Government of Nova Scotia; 2006. Available from: www.gov.ns.ca/health/nshis/. Accessed 2009 Oct 27. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murray M, Berwick DM. Advanced-access scheduling in primary care [Letter] JAMA. 2003;290(3):333. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.3.333-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray M, Berwick DM. Advanced access: reducing waiting and delays in primary care. JAMA. 2003;289(8):1035–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.8.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pickin M, O’Cathain A, Sampson FC, Dixon S. Evaluation of advanced access in the national primary care collaborative. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(502):334–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoen C, Osborn R, Huynh PT, Doty M, Davis K, Zapert K, et al. Primary care and health system performance: adults’ experiences in five countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004. pp. W4-487–503. Suppl Web Exclusives. Available from: http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/full/hlthaff.w4.487/DC1. Accessed 2009 Oct 27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Intelligence Consulting Group Inc . Primary Care Initiative final report for Cape Breton District Health Authority. Cape Breton, NS: Cape Breton District Health Authority; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Primary Care Development Team . The National Primary Care Collaborative. The first two years. Manchester, UK: National Primary Care Development Team; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Health Quality Council . Clinical practice redesign. Improving office processes. Saskatoon, SK: Health Quality Council; 2007. Available from: www.hqc.sk.ca/download.jsp?jYi4iAbg39oF80OzfoR7EjBIzBf0QfLQkUwK4QBZaJu9/LRqTXv+Wg==. Accessed 2009 Oct 27. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones W, Elwyn G, Edwards P, Edwards A, Emmerson M, Hibbs R. Measuring access to primary care appointments: a review of methods. BMC Fam Pract. 2003;4:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-4-8. Epub 2003 Jul 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray M. Answers to your questions about same-day scheduling. Fam Pract Manag. 2005;12(3):59–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dixon S, Sampson FC, O’Cathain A, Pickin M. Advanced access: more than just GP waiting times? Fam Pract. 2006;23(2):233–9. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi104. Epub 2005 Dec 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valenti WM, Bookhardt-Murray LJ. Advanced access scheduling boosts quality productivity and revenue. Drug Benefit Trends. 2004;16(10):510, 513–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan-Canadian Primary Health Care Indicator Development Project . Pan-Canadian primary health care indicators. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2006. Available from: http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/products/PHC_Indicator_Report_1-Volume_2_Final_E.pdf. Accessed 2009 Oct 27. Report 1, Vol 2. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ajzen I, Manstead ASR. Changing health-related behaviors: an approach based on the theory of planned behavior. In: van den Bos K, Hewstone M, de Wit J, Schut H, Stroebe M, editors. The scope of social psychology: theory and applications. New York, NY: Psychology Press; 2007. pp. 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahluwalia S, Offredy M. A qualitative study of the impact of the implementation of advanced access in primary healthcare on the working of general practice staff. BMC Fam Pract. 2005;6:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-6-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peat J, Barton B. Medical statistics: a guide to data analysis and critical appraisal. Toronto, ON: Wiley-Blackwell; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ontario Health Quality Council . Improvement guide. Module 1. Access. Toronto, ON: Ontario Health Quality Council; 2009. Available from: www.ohqc.ca/pdfs/access.pdf. Accessed 2009 Oct 27. [Google Scholar]