Abstract

Early relaxation in the cardiac cycle is characterized by rapid torsional recoil of the left ventricular (LV) wall. To elucidate the contribution of the transmural arrangement of the myofiber to relaxation, we determined the time course of three-dimensional fiber-sheet strains in the anterior wall of five adult mongrel dogs in vivo during early relaxation with biplane cineangiography (125 Hz) of implanted transmural markers. Fiber-sheet strains were found from transmural fiber and sheet orientations directly measured in the heart tissue. The strain time course was determined during early relaxation in the epicardial, midwall, and endocardial layers referenced to the end-diastolic configuration. During early relaxation, significant circumferential stretch, wall thinning, and in-plane and transverse shear were observed (P < 0.05). We also observed significant stretch along myofibers in the epicardial layers and sheet shortening and shear in the endocardial layers (P < 0.01). Importantly, predominant epicardial stretch along the fiber direction and endocardial sheet shortening occurred during isovolumic relaxation (P < 0.05). We conclude that the LV mechanics during early relaxation involves substantial deformation of fiber and sheet structures with significant transmural heterogeneity. Predominant epicardial stretch along myofibers during isovolumic relaxation appears to drive global torsional recoil to aid early diastolic filling.

Keywords: restoring force, transmural deformation, fiber, sheet

The left ventricular (LV) myocardium is composed of intricately woven structures of myofibers that run parallel to the epicardial tangent plane (30, 35) and are arranged in radially oriented laminae or sheets (21). The principal fiber orientation presents a gradual counterclockwise rotation from the epicardium to the endocardium, resulting in a local helical architecture of myofibers with a transmural angle gradient spanning ~120°. The helical architecture of the LV myofibers is the mechanistic basis of global LV torsion, or twisting about the LV long axis (7, 16, 17), which facilitates homogeneous distribution of systolic shortening of the myofibers across the LV wall (2, 4). The laminar or sheet structure of the myocardium consists of a layered arrangement of branching myofiber bundles approximately four cells thick with extensive cleavage planes between the layers (21, 31). The myocardial sheet architecture exhibits a transmural and regional variation, and the sheet angles undergo a dynamic change during the cardiac cycle (37), whereas the muscle fiber angles do not (35). Sheet extension, thinning, and shear appear to be part of the mechanistic basis of systolic LV wall thickening, which contributes to minimizing end-systolic volume and thus maximizing stroke volume (11). The myocardial fiber and sheet structures therefore play an important role in LV contraction; however, the mechanistic significance of these structures during LV relaxation remains unknown.

Early relaxation in the cardiac cycle is a critical period for LV untwisting or torsional recoil, which releases energy stored during systole, likely contributing to ventricular suction during early filling (3, 4, 33, 36, 46). Torsional recoil is impaired in myocardial infarction (29), tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy (3, 38), and aortic stenosis (36), suggesting its importance in normal cardiac function.

In the present study, we reasoned that the structure(s) contributing to recoil (e.g., myofibers) would demonstrate the earliest and most prominent return to diastolic configuration during early relaxation. To investigate the contribution of the fiber and sheet structures to LV mechanics during early relaxation, we determined three-dimensional (3D) finite deformation in the LV anterior wall during early relaxation in normal dog hearts in vivo. Our strain analysis indicated complex fiber and sheet mechanics with transmural heterogeneity during early relaxation, represented by myofiber stretch in the epicardial layers, which confirms modeling predictions of a predominant role of epicardial fibers, and sheet shortening transverse to the fibers in the endocardial layers, all of which may aid early diastolic filling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All animal studies were performed according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All protocols were approved by the Animal Subjects Committee of the University of California, San Diego, which is accredited by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

Surgical preparation

Five adult mongrel dogs (19–28 kg) were anesthetized with intravenous thiopental sodium (8–10 mg/kg), intubated, and mechanically ventilated with isoflurane (0.5–2.5%), nitrous oxide (3 l/min), and medical oxygen (3 l/min) to maintain a surgical plane of anesthesia. A median sternotomy was performed to expose the heart, which was placed in a pericardial cradle. The surface ECG was recorded throughout the study. An 8-Fr pigtail micromanometer catheter (Millar Instruments, Houston, TX) was inserted through a 9-Fr arterial introducer placed in the left femoral artery, and the catheter tip was advanced into the LV. LV pressure was monitored with the pigtail micromanometer catheter, and the pressure was matched with that recorded from the side holes of the same catheter that was connected to a fluid-filled transducer. Central aortic pressure was monitored through another 8-Fr fluid-filled catheter placed in the left brachiocephalic artery.

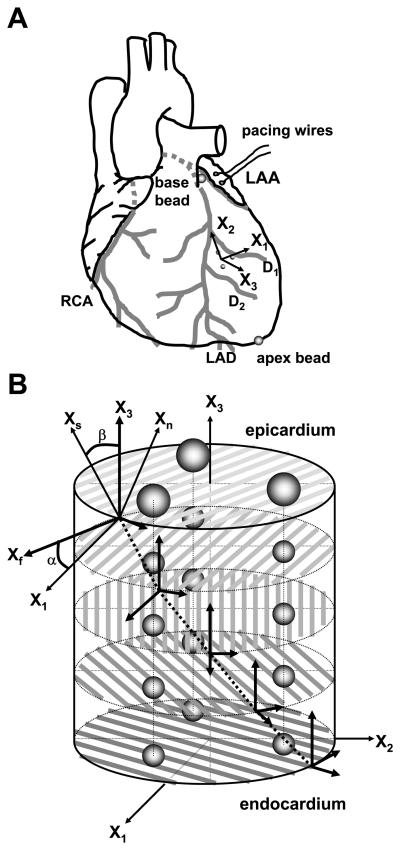

To measure 3D myocardial deformation in each heart, three transmural columns of four to six 0.8-mm-diameter gold beads were placed within the anterior wall between the first (D1) and second (D2) diagonal branches of the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) (Fig. 1A) with techniques described previously (40). Briefly, an 8-mm-thick Plexiglas template, with three holes drilled at the corners of a 10-mm equilateral triangle to act as guides for the bead insertion trocar, was sutured to the epicardium. After the bead insertion was complete, the platform was removed and a 1.7-mm-diameter surface gold bead was sewn onto the epicardium above each column. Gold beads (2 mm diameter) were sutured to the apical dimple (apex bead; Fig. 1A) and on the epicardium at the bifurcation of the LAD and left circumflex coronary artery (base bead; Fig. 1A) to provide end points for a LV long axis. The local epicardial tangent plane defined by the three epicardial surface gold beads and the LV long axis was used to define a local cardiac coordinate system aligned with the circumferential, longitudinal, and radial axes of the LV wall (26). A pair of pacing wires was sutured to the left atrial appendage (LAA; Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Sites of marker implantation. A: schematic representation of the heart. X1, circumferential axis; X2, longitudinal axis; X3, radial axis; LAA, left atrial appendage; RCA, right coronary artery; LAD, left anterior descending artery; D1, D2, first and second diagonal branch of LAD, respectively. B: schematic representation of excised tissue block containing the bead set. Fiber angle (α) was measured in the circumferential-longitudinal (X1-X2) plane at each transmural depth with reference to the positive circumferential axis (X1), with a positive angle defined as rotation toward the longitudinal axis (X2). Sheet angle (β) was measured in the plane perpendicular to the fiber angle at each transmural depth with reference to the radial axis (X3), with a positive angle defined as rotation towards the positive cross-fiber direction (Xcf). Xf, fiber axis; Xs, sheet axis; Xn, axis oriented normal to the sheet plane. The Xf, Xs, and Xn axes present a Cartesian system (see text for details).

Experimental protocol

Atrial pacing was performed by stimulating both atrial electrodes (Fig. 1A) with a square-wave, constant-voltage electronic stimulator at a frequency 20% above baseline heart rate to suppress native sinus rhythm. Stimulation parameters (voltage 10% above threshold, duration of 8 ms, and frequency) were kept constant in each animal. The animal was positioned in a biplane radiography system, with image planes adjusted such that all the bead markers were visible in both the anteroposterior (AP) and lateral (LAT) views. The image acquisition system for dual digital camera operation was based on two MegaPlus ES310/T cameras (Redlake, San Diego, CA) controlled by custom software (Forster System Engineering, Irvine, CA). With mechanical ventilation suspended at end expiration, synchronous biplane cineradiographic images of the bead markers were digitally acquired at 125 frames/s for a total of 4 s with simultaneous recording of ECG, LV pressure, and camera shutter markers for subsequent correlation of cine images with physiological events. At the end of the study, snares were placed around the lung hila and the inflow and outflow vessels of the heart. A 22- to 26-Fr cannula with side holes was inserted into the ascending aorta through a brachiocephalic artery. An overdose of pentobarbital sodium was administered, and the heart was brought to arrest by tightening the ligatures around the inflow vessels. The aortic cannula was perfused with normal saline at ~100–110 mmHg, which closed the aortic valve and perfused the coronary arteries. After coronary flow was established, the LV pressure was adjusted to the end-diastolic pressure observed in the study by injection of normal saline into the LV cavity, the right ventricle was vented, and the heart was fixed by switching the aortic cannula perfusate to buffered glutaraldehyde (2.5%) (44). Because the heart was fixed at end-diastolic pressure, fiber and sheet orientations in the fixed hearts were assumed to represent the fiber-sheet structure in the end-diastolic reference configuration (11). The heart was excised and stored in 2.5% buffered glutaraldehyde for 24 h and then transferred to 10% buffered formalin for 24–48 h.

Spherical correction and 3D reconstruction of cineradiographic images

The digital images obtained from the biplane X-ray intensifiers are spherically distorted because of the curved surface of the image intensifiers and the camera lenses. This spherical distortion was corrected in the AP and LAT views separately, by using cubic interpolation of the mapping of a planar, rectangular grid of reference beads attached to the front of the image intensifier without moving the X-ray tubes and image intensifiers from their positions during the study. Finally, images of a helical phantom were recorded to reconstruct the 3D coordinates of the gold bead markers in each frame from the spherically corrected biplane images (23).

Histology

To avoid the distortional effects of dehydration and shrinkage associated with embedding, histological measurements were obtained with freshly fixed heart tissue. A transmural rectangular block of tissue in the implanted bead set was carefully removed from the ventricular wall, with the edges of the block cut parallel to the local circumferential, longitudinal, and radial axes of the LV as determined from the same epicardial markers used for the strain analysis. The transmural thickness of the block was measured, and the block was sliced into 1-mm-thick sections parallel to the epicardial tangent plane, forming a series from the epicardium to the endocardium to measure the fiber angles across the LV wall. Fiber angle (α) was determined under a dissection microscope with reference to the positive circumferential axis (Fig. 1B). Mean α was calculated at each transmural depth as described previously (11). Each 1-mm slice of tissue was then embedded with Tissue-Tek OCT compound (Sakura Finetek USA, Torrance, CA) and quickly frozen in a 2-methylbutane bath cooled with dry ice. Multiple serial thin sections (5 μm) perpendicular to the mean fiber direction were made from each slice of tissue, transferred to a glass slide, and allowed to desiccate for 10 min. Digital images of the tissue section were acquired at low-power magnification (×20) with a digital camera (Coolpix 990; Nikon, Melville, NY) mounted on a light microscope (Optiphot-2; Nikon). The images were transferred to a Windows-based computer with image processing software (Image J version 1.30g; NIH). Myocardial laminae, or sheets, were directly visible with no further enhancement of the digital montage. Sheet angle (β) was measured with reference to the positive radial axis (Fig. 1B) as reported previously (11). Angle measurements were made for all visible cleavage planes in 3–9 sections to achieve ~100–300 measurements per slice of tissue, and mean β was calculated in each 1-mm slice of tissue. This process was repeated from the epicardial slice to the endocardial slice to yield transmural distribution of mean sheet angles.

Strain analysis

The 3D coordinates of the implanted markers were obtained as described in Spherical correction and 3D reconstruction of cineradiographic images for an entire cardiac cycle selected for each animal. In principle, continuous, nonhomogeneous transmural distributions of 3D finite strains were calculated with an approach developed in this laboratory by Waldman et al. (40), later by McCulloch and Omens (25), and most recently by Costa et al. (11). However, many of the fitting algorithms used in this study have been revised and the software was rewritten for a Windows-based system. Briefly, a continuous polynomial position field that mapped the beads in the undeformed reference configuration to those in the deformed configuration was determined. In essence, the deformed position of a bead was approximated by a polynomial function of its reference position. The degrees of freedom in the polynomial position field were optimized to give the best fit of the measured bead positions relative to the approximated or fit bead positions. The order of the polynomial is at most linear in circumferential and apex-base, and the maximum order in radius is typically quadratic. To eliminate oscillations in the fitting polynomial, the number of degrees of freedom was kept much smaller than the number of measurements, typically 10-fold fewer. With this continuous polynomial mapping from reference position to current position, differentiation with respect to reference position gives the deformation gradient tensor, F, which depends on position. The Lagrangian Green's strain tensor was then calculated as 0.5(FTF – I) at various values of reference wall depth, where FT is the transpose of F and I is the identity matrix.

Six independent finite strains were computed in the cardiac coordinate system (X1, X2, X3) (26). The three normal strain components reflect myocardial stretch or shortening along the circumferential (E11), longitudinal (E22), and radial (E33) cardiac axes, and the three shear strains (E12, E13, and E23) represent angle changes between pairs of the initially orthogonal coordinate axes. To relate the finite strains to the local 3D structure of the LV wall, a local fiber-sheet coordinate system (Xf, Xs, Xn) was constructed in each heart, which defines the muscle fiber axis (Xf), the sheet axis (Xs) that lies within the sheet plane and is perpendicular to Xf, and the orthogonal Xn axis oriented normal to the sheet plane (10). With the values of α and β at all depths, an orthogonal transformation was performed to convert the strain tensor from the cardiac coordinate system to the fiber-sheet coordinate system (10). This yields another set of six finite strains (“fiber-sheet strains”): the three normal strains represent stretch or shortening along the fiber direction (Eff), along the sheet direction (Ess), and normal to the fiber-sheet plane (Enn), whereas the three shear strains measure shear within the sheet plane (Efs) and shear that results from sliding of adjacent sheets parallel to the fiber direction (Efn) or transverse to the fiber axis (Esn) (37).

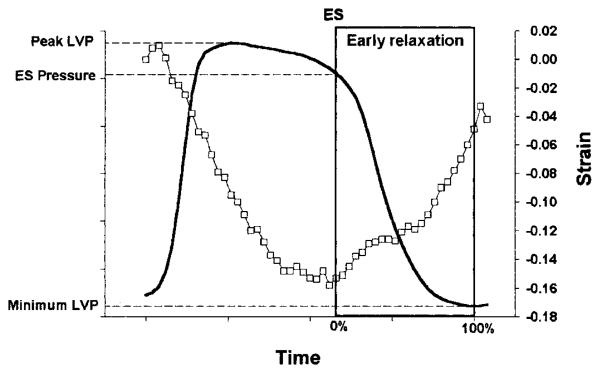

Transmural finite strains were calculated for each frame (125 frames/s) during early relaxation as a deformed configuration, with end diastole (defined at the time of the peak of the ECG R wave) as the reference state. The pressure at the nadir of the dicrotic notch of the central aortic pressure was used to estimate the time of end systole from the micromanometer tracing. Early relaxation was defined as the period beginning at end systole (time = 0%) and ending at minimum LV pressure (time = 100%; Fig. 2; Ref. 19). The strain data in each animal during the early relaxation period were linearly interpolated to determine finite strains at 10% increments in time. The strain time course was determined at three wall depths: 25% (epicardium), 50% (midwall), and 75% (endocardium) wall depth from the epicardial surface. Fiber-sheet strains deeper than 75% were not determined because of the presence of two separate populations of sheets in the inner 20% of the wall (see results).

Fig. 2.

Early relaxation. Early relaxation was defined as the period beginning at end systole (ES) and ending at minimum LV pressure (LVP, solid line). □, Circumferential strain (E11) at midwall.

Statistical analysis

Values are means ± SE unless otherwise specified. The effects of wall depth and time on each strain component were determined by two-factor repeated-measures ANOVA. The Student-Newman-Keuls method was used for ANOVA post hoc analysis. Statistical tests were performed with SigmaStat 3.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Hemodynamic parameters

Heart rate was 133 ± 12 beats/ min, LV end-diastolic pressure was 9 ± 1 mmHg, LV end-systolic pressure was 99 ± 6 mmHg, and LV pressure at the end of early relaxation was 3 ± 2 mmHg. The duration of early relaxation was 134 ± 15 ms, and early relaxation contained 17 ± 2 data sets before time interpolation. The time constant of LV isovolumic pressure decay (τ) was 23 ± 5 ms (logarithmic method) (32, 42). The bead set location was 65 ± 1% of the distance from base to apex along the LV long axis, in a region of the anterior LV free wall ~1–1.5 cm away from the LAD. Mean wall thickness at the bead set location was 10 ± 1 mm, and the deepest bead was located at 91 ± 2% wall depth.

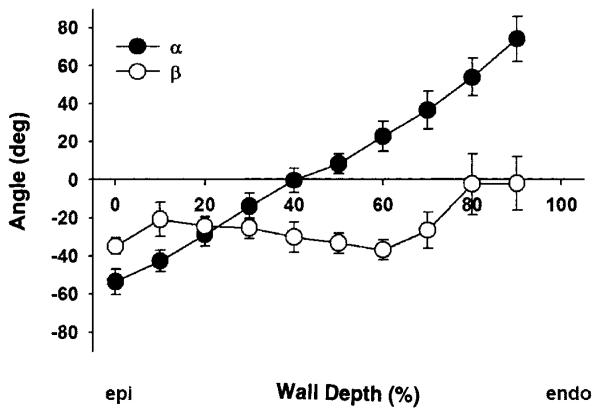

Fiber and sheet orientation

Figure 3 illustrates the transmural distribution of the measured fiber (α) and sheet (β) angles, which were consistent among all the animals studied. The mean fiber angles α ranged approximately from −60° to +60°, from epicardium to endocardium, resulting in a transmural gradient of ~120°. The mean sheet angles β were predominantly negative, with small variations across the wall (from approximately −36° to −2°). However, in four of five hearts, we observed an emergence of another sheet population ~70–90° apart within the endocardial 20% of the wall, resulting in a transition of the mean sheet orientation from negative to positive in each of these four hearts. One population remained relatively constant throughout the wall, whereas another population coexisted only in the inner wall.

Fig. 3.

Measured fiber angle (α) and sheet (β) angles vs. % wall depth (n = 5; means ± SE). Mean α ranged approximately from −60° to +60° from epicardium (epi) to endocardium (endo), resulting in a transmural gradient of ~120°. Mean β was predominantly negative, with small variations across the wall (approximately −36° to −2°).

Strains during early relaxation in cardiac coordinates

The time course of local cardiac strains during early relaxation is shown in Fig. 4. During early relaxation, significant myocardial stretch in the circumferential direction (E11, P < 0.001) and wall thinning (E33, P < 0.001) were observed (Table 1). Significant effects of depth were also observed in E11 (P = 0.002) and E33 (P < 0.001), with both circumferential stretch and wall thinning more pronounced in the endocardium than in the epicardium (Table 1). No significant change was observed in longitudinal stretch (E22) during early relaxation (P = 0.298). Mean circumferential-longitudinal shear strain (E12) was positive at end systole and decreased during early relaxation (P < 0.001). E12 exhibited a significant effect of depth (P = 0.046), more prominent in the epicardium (Table 1). Transverse shear strain (E13) also showed a significant change during early relaxation (P < 0.001).

Fig. 4.

Time course of finite strains during early relaxation in local cardiac coordinates. Note significant endocardial circumferential stretch (E11), endocardial wall thinning (E33), epicardial torsional recoil (E12), and transverse shear (E23, E13) during early relaxation (P < 0.05). Values are means ± SE. mid, Midwall; ER, early relaxation; ES, end systole, time = 0%; end of ER, time = 100%. Note different scales for each strain.

Table 1.

Two-factor repeated-measures analysis of variance during early relaxation

| Strain | ES | End of ER |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiac Coordinates | ||

| E11*†‡ | ||

| Epi | −0.079±0.019 | −0.023±0.007 |

| Endo | −0.214±0.036 | −0.108±0.027 |

| E22† | ||

| Epi | −0.019±0.013 | −0.031±0.009 |

| Endo | −0.047±0.012 | −0.051±0.010 |

| E33*†‡ | ||

| Epi | 0.090±0.020 | 0.055±0.014 |

| Endo | 0.346±0.033 | 0.144±0.028 |

| E12*† | ||

| Epi | 0.037±0.011 | 0.000±0.006 |

| Endo | 0.013±0.010 | −0.016±0.007 |

| E23*†‡ | ||

| Epi | 0.008±0.014 | 0.021±0.005 |

| Endo | 0.113±0.025 | 0.074±0.021 |

| E13* | ||

| Epi | 0.051±0.016 | 0.004±0.005 |

| Endo | 0.075±0.020 | 0.012±0.010 |

| Fiber-Sheet Coordinates | ||

| Eff*†‡ | ||

| Epi | −0.092±0.021 | −0.028±0.012 |

| Endo | −0.112±0.024 | −0.081±0.018 |

| Ess*†‡ | ||

| Epi | 0.053±0.010 | 0.026±0.007 |

| Endo | 0.189±0.034 | 0.063±0.031 |

| Enn‡ | ||

| Epi | 0.032±0.018 | 0.002±0.011 |

| Endo | 0.008±0.062 | 0.004±0.037 |

| Efs*†‡ | ||

| Epi | 0.042±0.017 | −0.003±0.008 |

| Endo | 0.111±0.037 | 0.058±0.026 |

| Esn | ||

| Epi | −0.050±0.016 | −0.044±0.008 |

| Endo | −0.019±0.113 | −0.012±0.054 |

| Efn* | ||

| Epi | −0.020±0.014 | −0.004±0.002 |

| Endo | −0.057±0.031 | −0.009±0.013 |

Values for epicardial (Epi) and endocardial (Endo) strains are means ± SE. E11, E22, E33, normal strains; E12, E23, E13, shear strains; Eff, Ess, Enn, fiber-sheet normal strains; Efs, Esn, Efn, fiber-sheet shear strains; ES, end systole; ER, early relaxation. Statistically significant (P<0.05) effects of

time,

depth,

interaction between time and depth are shown.

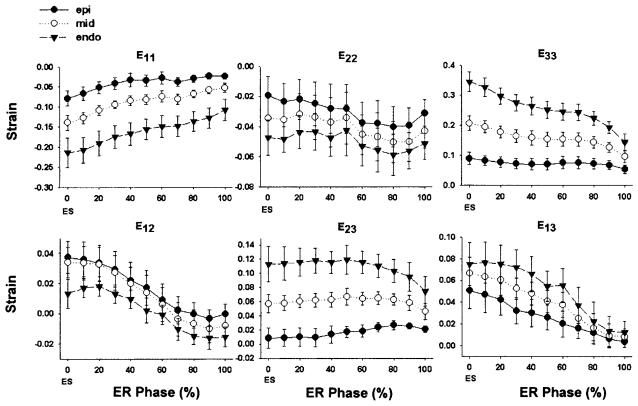

Strains during early relaxation in fiber-sheet coordinates

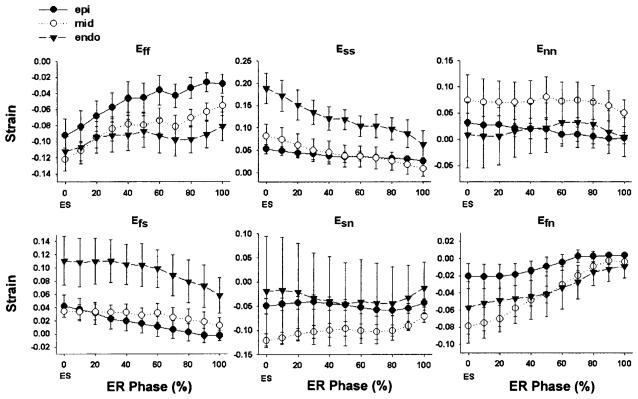

The time course of the fiber-sheet strains during early relaxation is shown in Fig. 5. Significant stretch along the fiber direction (Eff) was observed during early relaxation (P < 0.001), particularly in the epicardium (P = 0.005; Table 1). In addition, sheet strain (Ess) was positive at end systole and decreased significantly during early relaxation (P < 0.001), with a significant effect of depth (P = 0.007), indicating substantial shortening of the sheet plane perpendicular to the muscle fiber axis, particularly in the endocardium (P = 0.007; Table 1). No significant change was observed in the strain normal to the fiber-sheet plane (Enn, P = 0.775). Significant change during early relaxation was also observed in the fiber-sheet shear strain (Efs, P < 0.001) and the fiber-normal shear strain (Efn, P < 0.001), and Efs exhibited a significant effect of depth (P = 0.007). The sheet-normal shear strain (Esn) did not change significantly during early relaxation (Table 1).

Fig. 5.

Time course of finite strains during early relaxation in fiber-sheet coordinates. Note significant epicardial stretch along the fiber direction (Eff), endocardial sheet shortening (Ess), and fiber shear (Efs, Efn) during early relaxation (P < 0.05). Values are means ± SE. Note different scales for each strain.

Post hoc analysis revealed that both Eff and Ess achieved significant change from the end-systolic baselines (P < 0.05) as early as 20% into the early relaxation phase (Fig. 5). The LV pressure was 63 ± 6 mmHg at this time point, which was 27 ms (mean) after end systole. Therefore, significant change in both Eff and Ess occurred clearly before the mitral valve opening, namely, during isovolumic relaxation.

DISCUSSION

The objective of this study was to investigate the contribution of the fiber and sheet structures and their interaction during early relaxation. We defined early relaxation as the time period between end systole and the minimum LV pressure, which includes both isovolumic relaxation and early LV filling. Our results indicated that early relaxation involves dynamic fiber-sheet mechanics characterized by stretch along the myofibers (Eff) in the epicardial layers and shortening in the sheet plane transverse to the myofibers (Ess) in the endocardial layers as well as significant shears (Efs, Efn). Notably, the stretch along the myofibers and the shortening in the sheet plane occurred during isovolumic relaxation before mitral valve opening.

Fiber and sheet orientation

The fiber angle measurements exhibited a nearly symmetrical transmural distribution with circumferential fibers located near the midwall, consistent with the classic work of Streeter et al. (35). We also found an almost linear distribution of fiber angles transmurally (Fig. 3). Several lines of evidence suggest that both the symmetry and linearity of transmural fiber angle distribution have considerable regional variability. For example, Streeter et al. (35) showed a linear distribution of fiber angles transmurally in the apical regions and somewhat exponential distribution at the two surfaces (epicardium and endocardium) in the basal regions. On the other hand, the transmural distribution of fiber orientation found by Costa et al. (11) was increasingly nonsymmetrical from base to apex but was linear at both the basal and apical measurement sites. The symmetrical and linear nature of the transmural fiber distribution in this study is likely to reflect our measurement site at the midanterior wall.

Although the laminar architecture of the myocardium has been recognized for many years, transmural distributions of the sheet orientation have only been obtained indirectly from measured projections in orthogonal planes (11). Our direct sheet measurements revealed sheet populations that have not been documented previously: two distinct populations of sheets ~70–90° apart at the most endocardial sites. On basis of the hypothesis that the sheets are oriented along planes of maximum shear, Arts et al. (1) predicted two populations of sheets ~90° apart that occur in patches separated by distinct boundaries. Although those authors often noted transmural transition from one population to another, their measurements belonged to one population for a given transmural depth. In contrast, our measurements showed one population remaining relatively constant throughout the wall, with an emergence of another population in the inner wall. In the present study, we selected the deepest site of our fiber-sheet strain calculation (75% wall depth) above the layer where the second sheet population appears (80% wall depth), so that the coexistence of two separate families of sheet orientation would not affect our fiber-sheet mechanics data. The significance of this sheet structure near the endocardium is unknown.

LV mechanics during early relaxation

Finite strains at end systole (Figs. 4 and 5; early relaxation phase = 0%) are consistent with previous data in the literature, although significant regional variation is known (8, 11, 14, 20, 22, 27, 28, 40, 41, 45). Our strains during early relaxation in cardiac coordinates (Fig. 4) were in agreement with data in human hearts from MRI with tissue tagging (20). Although MRI is a promising tool that allows noninvasive strain measurements at multiple sites, its utility in describing cardiac mechanics during diastole has some drawbacks at present. Tagged MRI images do not provide an accurate estimate of the end-diastolic geometry, or the reference configuration, for the strain calculation because the first image after the ECG R wave does not show contrast between the blood pool and the LV wall (20). Furthermore, both the transmural and temporal resolution of MRI are still relatively low compared with the cineangiographic method. In addition, MRI determination of quantitative structural data is in its infancy (13, 39) and does not allow calculation of fiber and sheet dynamics (39).

In the present study, diastolic LV deformation involved complex fiber-sheet mechanics, which exhibited substantial transmural heterogeneity (Table 1). The wall thinning process (E33) during early relaxation, which is likely to aid early ventricular filling, provided an example of intricate fiber-sheet mechanics. Costa et al. (11) discovered that both sheet extension (Ess) and shear (Esn) contribute equally to systolic wall thickening (E33), which exhibits a transmural gradient with progressively increasing strain toward the endocardium. We found that wall thinning (E33) during early relaxation was also greatest in the endocardium. Significant reduction in endocardial E33 was accompanied by reduction in endocardial Ess, or sheet shortening, whereas Esn remained unchanged. This finding implies that wall thinning during early relaxation results mainly from sheet shortening and sheet shear Esn returns to baseline later in diastole and further promotes wall thinning. This temporal sequence of sheet mechanics raises the important implication that diastolic sheet shear (Esn) restoration may require substantial wall expansion resulting from ventricular filling.

E12 during early relaxation was most prominent in the epicardium, returning nearly to baseline at the end of early relaxation (Table 1 and Fig. 4). This is consistent with the observation that the majority of torsional recoil takes place during early relaxation (3, 5, 33, 36). Although change in global LV torsion about the LV central axis usually accompanies change in E12 (45), these two parameters are not equivalent. Global torsion is calculated as an angle change measured from the displacement of markers or tags about the LV central axis system and may be most closely associated with local circumferential-radial shear (E13). MRI tagging studies have provided important clues as to the relationship between these two parameters. Global LV torsion is higher in magnitude in the endocardial layers than in the epicardial layers (8, 12, 24, 33, 45), and this transmural gradient produces the E13 shear (45). In contrast, epicardial E12 is significantly greater than endocardial E12 in the apical and midregions, whereas endocardial E12 is the greater in the basal regions (6). This may be related to the change in global LV torsion sense from counterclockwise at the apex to clockwise at the base, which is also supported by the change in sign of E13 from positive at the apex to negative at the base (45). Because our bead sets were located between mid- and apical regions, our E12 and E13 measurements are consistent with MRI tagging data.

Our data indicate significant epicardial stretch along myofibers (Eff) during early relaxation (Table 1 and Fig. 5). This finding is consistent with the previous work of Rodriguez et al. (34), who observed almost complete restitution of the sarcomere length during early relaxation in epicardial layers but not in the endocardial layers. Epicardial predominance of fiber stretch (Eff) during early relaxation supports a proposed mechanism of global torsional deformation (18). Spirally aligned myofibers in the heart convert one-dimensional fiber deformation into global LV torsional deformation. Both positive (systolic torsion) and negative (diastolic torsional recoil) torsional deformations primarily result from the sum of torque forces developed by shortening of epicardial and endocardial fibers, and because myofibers in these two surfaces are wrapped in helices of opposite sense, they develop counterrotating torques. The epicardial fiber torque exceeds the endocardial counterpart and drives global LV torsional deformation during the bulk of systole, because epicardial fibers are at a greater radius from the LV central long axis and thus have longer lever arms than endocardial fibers to produce a greater moment. Furthermore, the epicardium contains more fibers in a given epicardial volume shell than an endocardial volume shell of the same thickness. Therefore, global LV torsional deformation appears to be controlled by the epicardial myocardium (18).

The predominance of epicardial Eff during early relaxation may also be facilitated by electrical heterogeneity of the normal heart. Epicardial fibers repolarize earlier than endocardial fibers (43), and the greater stretch of epicardial than endocardial fibers during early relaxation (Eff; Fig. 5) alters the balance of epicardial/endocardial moments, leading to torsional recoil. The critical role of epicardial myofibers during diastole is also supported by a transmural gradient in several molecular components of the myofibers. Torsional recoil is driven by restoring forces likely deriving from systolic deformation of the fiber structure, such as sarcomeric components (e.g., titin) and extracellular matrix (e.g., perimysial collagen fibers along myofibers), below slack length (15). The canine myocardium coexpresses, at the level of the half-sarcomere, two main classes of cardiac titin isoforms, N2B and N2BA (9). N2B is smaller and stiffer than N2BA, and a transmural gradient in ratios of N2BA to N2B exists, decreasing from endocardium to epicardium (3). Thus titin-based stiffness is largest at the epicardium and progressively decreases toward the endocardium. Because there is little transmural gradient in fiber shortening (Eff) at end systole (11), the stiffer properties of titin at the epicardium would be expected to produce a greater restoring force in the epicardium than in the endocardium. In addition, a transmural gradient of myosin light chain (MLC) phosphorylation allows epicardial fibers to generate a greater force than endocardial fibers during systole, facilitating LV systolic torsional deformation (12). The MLC phosphorylation gradient produces greater systolic tension in the epicardium, possibly resulting in a greater restoring force development in the epicardium than in the endocardium. All of these transmurally heterogeneous factors (timing of repolarization, titin isoforms, and MLC phosphorylation) likely contribute to the predominance of epicardial Eff observed in the current study.

Another potential source of restoring force to drive diastolic torsional recoil is systolic deformation within the sheet structure. During systole, there is significant shearing of the fibers within the sheet plane. This fiber-sheet shear (Efs) exhibited a significant transmural gradient, being greater in the endocardium than in the epicardium, and decreased significantly during early relaxation (Table 1 and Fig. 5). Such systolic fiber-sheet shearing is likely to accumulate energy in the deforming extracellular matrix (e.g., collagen struts connecting myofibers). Release of this energy during early relaxation could facilitate the restoration of the end-diastolic configuration of the fibers in the sheet plane, contracts the sheets (Ess) to cause wall thinning (E33), and contributes to torsional recoil in collaboration with epicardial fiber stretch.

Limitations

In the present study, we examined 3-D finite deformation of the LV wall in open-chest, anesthetized dogs at higher than normal heart rates. Therefore, the fiber-sheet dynamics that we observed may not precisely reflect the cardiac mechanics in closed-chest, awake animals. We also used intravenous thiopental for induction anesthesia. Thiopental has cardiodepressant effects, which may have affected the local mechanics that we measured. Species difference (canine vs. human) is another factor to consider when these results are clinically extrapolated, because little is known about species variations in fiber-sheet structures. However, regional variations in cardiac strains in human are very similar, and a recent study by Bogaert and Rademakers (6) estimated Eff in humans that showed a similar transmural gradient. The fiber-sheet dynamics may also exhibit regional variations, considering substantial regional variations in the fiber and sheet distributions (11, 21, 35). Our data represent the fiber-sheet mechanics in the LV midanterior wall, and further study will be needed to clarify this point. In addition, we did not determine the fiber-sheet mechanics at the very endocardial layers because of the presence of two distinct sheet populations. How these two perpendicular sheet structures participate in normal cardiac mechanics at a given depth will require further study.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that normal LV mechanics during early relaxation involves substantial deformation of fiber and sheet structures of the myocardium. Fiber-sheet mechanics exhibit significant transmural heterogeneity during this part of the cardiac cycle, characterized by significant stretch along myofibers in the epicardial layers and sheet shortening and shear in the endocardial layers. Importantly, predominant epicardial stretch along the fiber direction occurred during isovolumic relaxation, which appears to drive global torsional recoil. These findings suggest that epicardial myofibers and extracellular structures along myofibers as well as the sheet structure between the fibers are potential sources of restoring forces during early relaxation, which control the myocardial deformation to aid early ventricular filling.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Henk Granzier (Washington State University, Pullman, WA) for valuable input on titin isoforms. We also thank Jeff Carroll for developing the strain calculation software and Rish Pavelec and Rachel Alexander for managerial and technical assistance.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R01-HL-29589 (N. B. Ingels, Jr.) and R01-HL-32583 (J. W. Covell). H. Ashikaga is the recipient of a American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship (Western States Affiliate).

REFERENCES

- 1.Arts T, Costa KD, Covell JW, McCulloch AD. Relating myocardial laminar architecture to shear strain and muscle fiber orientation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H2222–H2229. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.5.H2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arts T, Reneman RS. Dynamics of left ventricular wall and mitral valve mechanics—a model study. J Biomech. 1989;22:261–271. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(89)90093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell SP, Nyland L, Tischler MD, McNabb M, Granzier H, LeWinter MM. Alterations in the determinants of diastolic suction during pacing tachycardia. Circ Res. 2000;87:235–240. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beyar R, Sideman S. The dynamic twisting of the left ventricle: a computer study. Ann Biomed Eng. 1986;14:547–562. doi: 10.1007/BF02484472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beyar R, Yin FC, Hausknecht M, Weisfeldt ML, Kass DA. Dependence of left ventricular twist-radial shortening relations on cardiac cycle phase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1989;257:H1119–H1126. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.4.H1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bogaert J, Rademakers FE. Regional nonuniformity of normal adult human left ventricle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H610–H620. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.2.H610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchalter MB, Rademakers FE, Weiss JL, Rogers WJ, Weisfeldt ML, Shapiro EP. Rotational deformation of the canine left ventricle measured by magnetic resonance tagging: effects of catecholamines, ischaemia, and pacing. Cardiovasc Res. 1994;28:629–635. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.5.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchalter MB, Weiss JL, Rogers WJ, Zerhouni EA, Weisfeldt ML, Beyar R, Shapiro EP. Noninvasive quantification of left ventricular rotational deformation in normal humans using magnetic resonance imaging myocardial tagging. Circulation. 1990;81:1236–1244. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.4.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cazorla O, Freiburg A, Helmes M, Centner T, McNabb M, Wu Y, Trombitas K, Labeit S, Granzier H. Differential expression of cardiac titin isoforms and modulation of cellular stiffness. Circ Res. 2000;86:59–67. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costa KD, May-Newman K, Farr D, O'Dell WG, McCulloch AD, Omens JH. Three-dimensional residual strain in midanterior canine left ventricle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1997;273:H1968–H1976. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.4.h1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costa KD, Takayama Y, McCulloch AD, Covell JW. Laminar fiber architecture and three-dimensional systolic mechanics in canine ventricular myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;276:H595–H607. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.2.H595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis JS, Hassanzadeh S, Winitsky S, Lin H, Satorius C, Vemuri R, Aletras AH, Wen H, Epstein ND. The overall pattern of cardiac contraction depends on a spatial gradient of myosin regulatory light chain phosphorylation. Cell. 2001;107:631–641. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00586-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dou J, Tseng WY, Reese TG, Wedeen VJ. Combined diffusion and strain MRI reveals structure and function of human myocardial laminar sheets in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:107–113. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fann JI, Sarris GE, Ingels NB, Jr, Niczyporuk MA, Yun KL, Daughters GT, 2nd, Derby GC, Miller DC. Regional epicardial and endocardial two-dimensional finite deformations in canine left ventricle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1991;261:H1402–H1410. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.5.H1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helmes M, Trombitas K, Granzier H. Titin develops restoring force in rat cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 1996;79:619–626. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.3.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ingels NB., Jr Myocardial fiber architecture and left ventricular function. Technol Health Care. 1997;5:45–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ingels NB, Jr, Daughters GT, 2nd, Stinson EB, Alderman EL. Measurement of midwall myocardial dynamics in intact man by radiography of surgically implanted markers. Circulation. 1975;52:859–867. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.52.5.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ingels NB, Jr, Hansen DE, Daughters GT, 2nd, Stinson EB, Alderman EL, Miller DC. Relation between longitudinal, circumferential, and oblique shortening and torsional deformation in the left ventricle of the transplanted human heart. Circ Res. 1989;64:915–927. doi: 10.1161/01.res.64.5.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karlsson MO, Glasson JR, Bolger AF, Daughters GT, Komeda M, Foppiano LE, Miller DC, Ingels NB., Jr Mitral valve opening in the ovine heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1998;274:H552–H563. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.2.H552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuijer JP, Marcus JT, Gotte MJ, van Rossum AC, Heethaar RM. Three-dimensional myocardial strains at end-systole and during diastole in the left ventricle of normal humans. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2002;4:341–351. doi: 10.1081/jcmr-120013299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LeGrice IJ, Smaill BH, Chai LZ, Edgar SG, Gavin JB, Hunter PJ. Laminar structure of the heart: ventricular myocyte arrangement and connective tissue architecture in the dog. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1995;269:H571–H582. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.2.H571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LeGrice IJ, Takayama Y, Covell JW. Transverse shear along myocardial cleavage planes provides a mechanism for normal systolic wall thickening. Circ Res. 1995;77:182–193. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.1.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacKay SA, Potel MJ, Rubin JM. Graphics methods for tracking three-dimensional heart wall motion. Comput Biomed Res. 1982;15:455–473. doi: 10.1016/0010-4809(82)90027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maier SE, Fischer SE, McKinnon GC, Hess OM, Krayenbuehl HP, Boesiger P. Evaluation of left ventricular segmental wall motion in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with myocardial tagging. Circulation. 1992;86:1919–1928. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.6.1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCulloch AD, Omens JH. Non-homogeneous analysis of three-dimensional transmural finite deformation in canine ventricular myocardium. J Biomech. 1991;24:539–548. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(91)90287-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meier GD, Ziskin MC, Santamore WP, Bove AA. Kinematics of the beating heart. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1980;27:319–329. doi: 10.1109/TBME.1980.326740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore CC, Lugo-Olivieri CH, McVeigh ER, Zerhouni EA. Three-dimensional systolic strain patterns in the normal human left ventricle: characterization with tagged MR imaging. Radiology. 2000;214:453–466. doi: 10.1148/radiology.214.2.r00fe17453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore CC, O'Dell WG, McVeigh ER, Zerhouni EA. Calculation of three-dimensional left ventricular strains from biplanar tagged MR images. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1992;2:165–175. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880020209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagel E, Stuber M, Lakatos M, Scheidegger MB, Boesiger P, Hess OM. Cardiac rotation and relaxation after anterolateral myocardial infarction. Coron Artery Dis. 2000;11:261–267. doi: 10.1097/00019501-200005000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nielsen PM, Le Grice IJ, Smaill BH, Hunter PJ. Mathematical model of geometry and fibrous structure of the heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1991;260:H1365–H1378. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.260.4.H1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Dell WG, McCulloch AD. Imaging three-dimensional cardiac function. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2000;2:431–456. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.2.1.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pouleur H, Rousseau MF, van Eyll C, Brasseur LA, Charlier AA. Force-velocity-length relations in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: evidence of normal or depressed myocardial contractility. Am J Cardiol. 1983;52:813–817. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(83)90420-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rademakers FE, Buchalter MB, Rogers WJ, Zerhouni EA, Weisfeldt ML, Weiss JL, Shapiro EP. Dissociation between left ventricular untwisting and filling. Accentuation by catecholamines. Circulation. 1992;85:1572–1581. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.4.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodriguez EK, Hunter WC, Royce MJ, Leppo MK, Douglas AS, Weisman HF. A method to reconstruct myocardial sarcomere lengths and orientations at transmural sites in beating canine hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1992;263:H293–H306. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.1.H293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Streeter DD, Jr, Spotnitz HM, Patel DP, Ross J, Jr, Sonnenblick EH. Fiber orientation in the canine left ventricle during diastole and systole. Circ Res. 1969;24:339–347. doi: 10.1161/01.res.24.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stuber M, Scheidegger MB, Fischer SE, Nagel E, Steinemann F, Hess OM, Boesiger P. Alterations in the local myocardial motion pattern in patients suffering from pressure overload due to aortic stenosis. Circulation. 1999;100:361–368. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takayama Y, Costa KD, Covell JW. Contribution of laminar myofiber architecture to load-dependent changes in mechanics of LV myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H1510–H1520. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00261.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tibayan FA, Lai DT, Timek TA, Dagum P, Liang D, Daughters GT, Ingels NB, Miller DC. Alterations in left ventricular torsion in tachycardia-induced dilated cardiomyopathy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;124:43–49. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.121299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tseng WY, Wedeen VJ, Reese TG, Smith RN, Halpern EF. Diffusion tensor MRI of myocardial fibers and sheets: correspondence with visible cut-face texture. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2003;17:31–42. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Waldman LK, Fung YC, Covell JW. Transmural myocardial deformation in the canine left ventricle. Normal in vivo three-dimensional finite strains. Circ Res. 1985;57:152–163. doi: 10.1161/01.res.57.1.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waldman LK, Nosan D, Villarreal F, Covell JW. Relation between transmural deformation and local myofiber direction in canine left ventricle. Circ Res. 1988;63:550–562. doi: 10.1161/01.res.63.3.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weiss JL, Frederiksen JW, Weisfeldt ML. Hemodynamic determinants of the time-course of fall in canine left ventricular pressure. J Clin Invest. 1976;58:751–760. doi: 10.1172/JCI108522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yan GX, Antzelevitch C. Cellular basis for the normal T wave and the electrocardiographic manifestations of the long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 1998;98:1928–1936. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.18.1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoran C, Covell JW, Ross J., Jr Rapid fixation of the left ventricle: continuous angiographic and dynamic recordings. J Appl Physiol. 1973;35:155–157. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1973.35.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Young AA, Kramer CM, Ferrari VA, Axel L, Reichek N. Three-dimensional left ventricular deformation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1994;90:854–867. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.2.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yun KL, Niczyporuk MA, Daughters GT, 2nd, Ingels NB, Jr, Stinson EB, Alderman EL, Hansen DE, Miller DC. Alterations in left ventricular diastolic twist mechanics during acute human cardiac allograft rejection. Circulation. 1991;83:962–973. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.3.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]