Abstract

Recent brain functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have shown that chronic back pain (CBP) alters brain dynamics beyond the feeling of pain. In particular, the response of the brain default mode network (DMN) during an attention task was found abnormal. In the present work similar alterations are demonstrated for spontaneous resting patterns of fMRI brain activity over a population of CBP patients (n=12, 29–67 years old, mean=51.2). Results show abnormal correlations of three out of four highly connected sites of the DMN with bilateral insular cortex and regions in the middle frontal gyrus (p<0.05), in comparison with a control group of healthy subjects (n=20, 21–60 years old, mean=38.4). The alterations were confirmed by the calculation of triggered averages, which demonstrated increased coactivation of the DMN and the former regions. These findings demonstrate that CBP disrupts normal activity in the DMN even during the brain resting state, highlighting the impact of enduring pain over brain structure and function.

Keywords: Brain, Default-mode network, Chronic pain, fMRI, resting state networks, functional connectivity

Chronic back pain (CBP) is increasingly viewed as a condition affecting normal brain function, causing cognitive impairments beyond the feeling of acute pain, including depression, sleeping disturbances and decision-making abnormalities [1,2,3]. Altered cortical dynamics in CBP have been demonstrated using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), both studying activation sites following external stimulation [10,24] and using seed based correlation analysis during the execution of simple attention demanding tasks [3]. The later study showed for the first time that CBP disrupts the dynamics of the default mode network (DMN), a set of cortical regions known to be more active at rest than during task performance [11,12,17,25,30].

The present study investigates the generality of the results described by Baliki et al., [3] by determining to what extent the DMN dynamical alterations are demonstrable by the spontaneous activity of brain resting state networks (RSN). To that aim the functional connectivity of eight well-established brain RSN [5] were fully characterized and compared in two groups: patients and healthy subjects. The strategy, in brief, consisted first in the identification of the most functionally connected sites (hubs) of each RSN, computing the cross correlation between the brain oxygen level dependent signals (BOLD). Then, correlations between the activity of these hubs and the rest of the brain were computed. Finally, triggered averages between key regions were computed to cross-validate the correlation findings. This double approach, which reduces the data sets’ dimensionality without assuming a previous anatomical parcellation, allowed the demonstration of broken correlation balance in CBP patients in three hubs belonging to the default mode network, caused by increased spontaneous coactivation of these regions with the insular cortices and decreased coactivation with regions in the middle frontal gyrus.

Participants were 12 chronic back pain patients (CBP) (29–67 years old, mean=51.2) and 20 healthy controls (HC) (21–60 years old, mean=38.4). All subjects were right-handed and all gave informed consent to procedures approved by Northwestern University (Chicago) IRB committee. The 12 patients and the respective 12 controls subjects participated in an earlier study where their clinical and demographic data, as well as pain related parameters, have been described [3]. Eight additional healthy subjects were used to test only the robustness of the method to identify connectivity hubs. Subjects were asked to lay still in the scanner and to keep their mind blank, eyes closed and avoid falling asleep [12]. fMRI data was acquired using a 3T Siemens Trio whole-body scanner with echo-planar imaging capability using the standard radio-frequency head coil. Multislice T2*-weighted echo-planar images were obtained with the following parameters: repetition time (TR) 2.5 s; echo time (TE) 70 ms; flip angle 90°; slice thickness, 3 mm; in-plane resolution, 3.437 × 3.437 mm. A T1-weighted anatomical MRI image was also acquired with TR, 22 ms; TE, 5.6 ms; flip angle, 20°; matrix 256 × 256; and a field of view of 240 mm; with 160 mm coverage in the slice direction.

BOLD signal was preprocessed using FMRIB Expert Analysis Tool [22] including motion correction using MCFLIRT, slice-timing correction using Fourier-space time-series phase-shifting, non-brain removal using BET, spatial smoothing using a Gaussian kernel of full-width-half-maximum 5 mm. Brain images were normalized to standard MNI 152 template using FLIRT and data was resampled to 4 mm × 4 mm × 4 mm resolution. A zero lag finite impulse response filter was applied to band pass filter (0.01 Hz – 0.1 Hz) the functional data (to avoid noise related to scanner drift and to eliminate high frequency artefacts related with physiological noise and head motion) [7]. An independent component (IC) based denoising procedure [4] consisting of edge and high frequency artefacts removal by linear regression was performed using the Melodic environment (http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl).

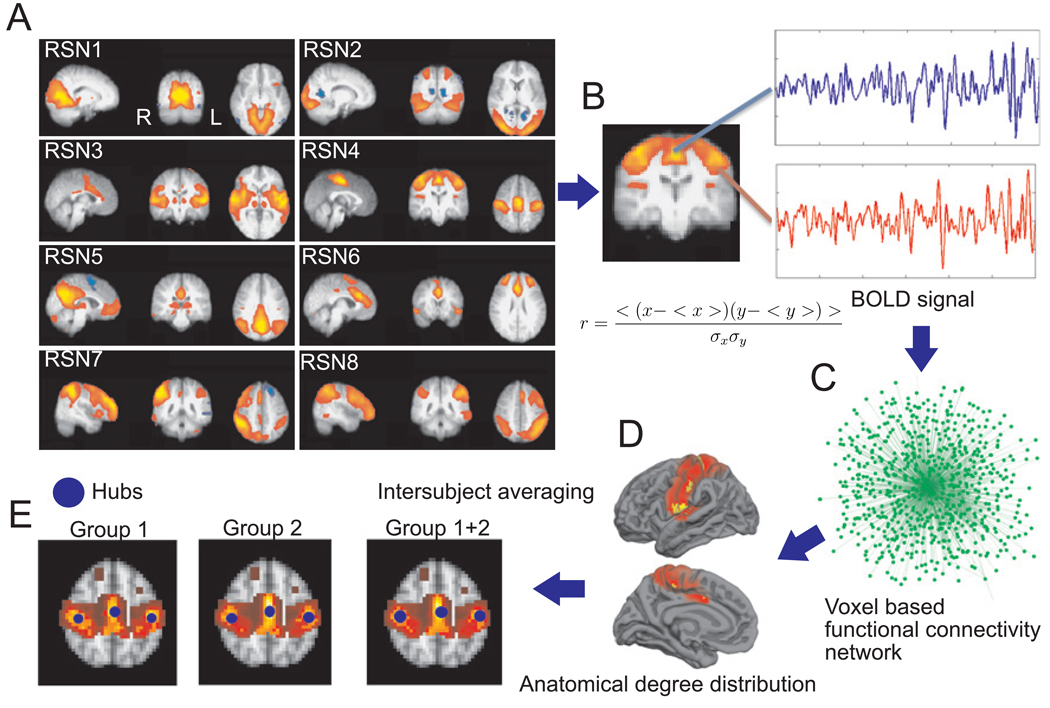

The most functionally connected seeds were selected first by identifying the voxels belonging to each of the eight IC components, previously obtained with PICA over a group of healthy subjects [5]. These regions, associated with specific cognitive functions, are labelled (see Fig. 1A) as follows: RSN1 (medial areas of the visual cortex), RSN2 (lateral areas of the visual cortex), RSN3 (auditory), RSN4 (sensory motor), RSN5 (default mode network), RSN6 (executive control), RSN7 (right dorsal visual stream), RSN8 (left dorsal visual stream). For each subject, the BOLD signal was extracted from all voxels comprising each RSN and from all gray matter voxels (Fig. 1B). The correlation coefficient r between a given pair of signals x and y was computed as:

| (1) |

where quantities between brackets represent the signal’s time averages and σ is the standard deviation of the signal. Functional connectivity networks were then constructed for every subject (Fig 1B) in each RSN using voxels as nodes of a graph and adding a link between two nodes if the lineal correlation r was greater than a positive threshold. Thresholds were chosen so that all constructed networks had the same link density δ, defined as: δ = 2L / [N(N - 1)]; where L is the total number of links in the network and N the total number of nodes. The link density δ thus reflects the proportion of all possible links in the network that are actually present. Networks were constructed for δ ranging from 0.01 to 0.5. The number of links of a given node is also called the degree of the node.

Figure 1.

Procedure to extract hubs of the RSN. A. One of the eight RSNs obtained with PICA is selected (in this case, RSN4). B. BOLD signals are extracted from all voxels belonging to the RSN and linear correlations computed between each pair of voxels. C. Functional connectivity networks are constructed for each subject, choosing thresholds so that all networks have the same degree density δ. D. Normalized degree distributions are mapped into the cortex anatomy for all subjects and RSNs. E. Maps are averaged for different groups of subjects and seeds are defined by the regions with the greatest connectivity.

To identify the most functionally connected hubs, the normalized degree was computed as the ratio between the degree of the node and the greatest degree in the network. Then, for each subject, the anatomical distribution of the normalized degree in each RSN and the whole gray matter was computed (Fig.1D) and averaged between all subjects (Fig. 1E). From this data, the most connected hubs were selected as the voxels with the highest normalized degree. (Since the spatial smoothing implies that close voxels have similar degree, only one seed was selected for each spatial cluster of high connectivity voxels).

The robustness of the method used to identify hubs was contrasted by segmenting (and comparing) 20 healthy subjects into three subgroups, one consisting of 12 healthy subjects (group 1) already studied in [3], one consisting of 8 additional healthy subjects (group 2) and a third group consisting of the entire 20 subjects (group 3) (a similar approach as in Buckner et al. [6]).

Seed based correlation analysis and correlation balance

The fMRI BOLD signal was averaged over a 3 × 3 × 3 voxels cube centred at the coordinates of each seed (see supplementary Table S1, abbreviations as in Salvador et al., [26]) The correlation coefficient (Eq. 1) between the seed and the rest of gray matter voxels in the brain was computed, resulting in a distribution of correlation values Ci (linear correlation between the seed and the ith voxel time series). This distribution of correlations is converted to z-scores as:

| (2) |

The resulting distribution z has zero mean and unity standard deviation. Finally, to parametrize and compare the spatial distribution of these seed’ correlations, the ratio between the number of positively correlated voxels (beyond a threshold ζ) and the number of negatively correlated voxels (beyond a threshold −ζ) was computed as in [3].

The most functionally connected seeds for each of the RSNs’ were identified following the procedure outlined above (see Fig. 1). Also, for comparison, seeds were extracted from four different groups (groups 1 to 3 of healthy subjects above and group 4 of CBP patients). In all groups the seeds locations resulted almost identical, even under changes in the link density δ used to construct the networks (δ ranging from 0.01 to 0.5, see supplementary figures S2 and S3). All seeds had normalized degree above 0.4 and the majority of them had normalized degree of approximately 0.6 with standard deviations of less than 0.15. Despite inter-subject variability in the location of the high degree sites the same results emerge very robustly in the average over different populations. This is consistent with recent results of van den Heuvel et al., [29] who have found similar values for average normalized degree distribution of the most connected brain sites.

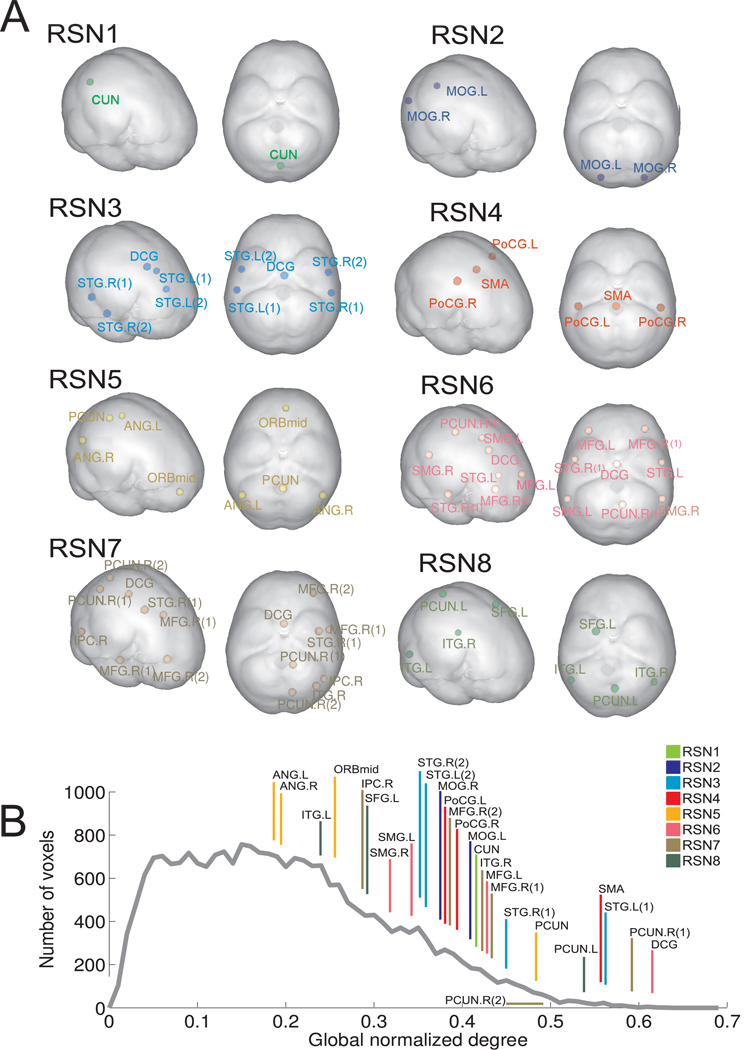

A total of 27 seeds were selected (see Supplementary Table S1 and Figure S1). The seeds’ location is shown in Fig. 2A. Notice that some seeds have high normalized degree in more than one of the RSNs, most notably, seeds in the median cingulate and paracingulate gyri (DCG) and the superior temporal gyrus (STG) are present in three of the RSNs. A natural question is whether these seeds only have high normalized degree within each RSN or they are also hubs of the global functional connectivity network (constructed over all gray matter voxels of the brain). In Fig 2B we show the average normalized degree distribution for group 1 (12 healthy subjects) and δ = 0.05, with the ranking of the 27 local hubs (labels are those of Table 1, the colour code is the same as in Fig. 2A). Seeds with the greatest connectivity were located in the cingulate cortex, the precuneus, supplementary motor area, and the superior temporal gyrus, consistent with previous identification of well- connected sites in whole brain functional and anatomical connectivity networks [6,16,19,20,29]. Note that all high degree seeds belonging to more than one RSN have also high global degree. This might reflect an important role for these sites in the coordination of activity between RSNs corresponding to different cognitive functions. Also note that many seeds have low global normalized degree and can only be regarded as well connected inside the RSN of which they are members, implying that seed selection using global normalized degree as a measure of importance in the global functional connectivity networks will overlook sites in many RSNs, including the DMN.

Figure 2.

A. Position of the 27 seeds classified by RSN's membership. Note that some seeds belong to more than one RSN. B. Ranking of seeds according to their global normalized degree (gray line: average normalized degree distribution for group 1, formed by 12 healthy controls and δ = 0.05). Colour code of the line segments indicates RSN membership (if a seed belongs to more than one RSN the colour indicates the RSN in which the seed has the greatest degree).

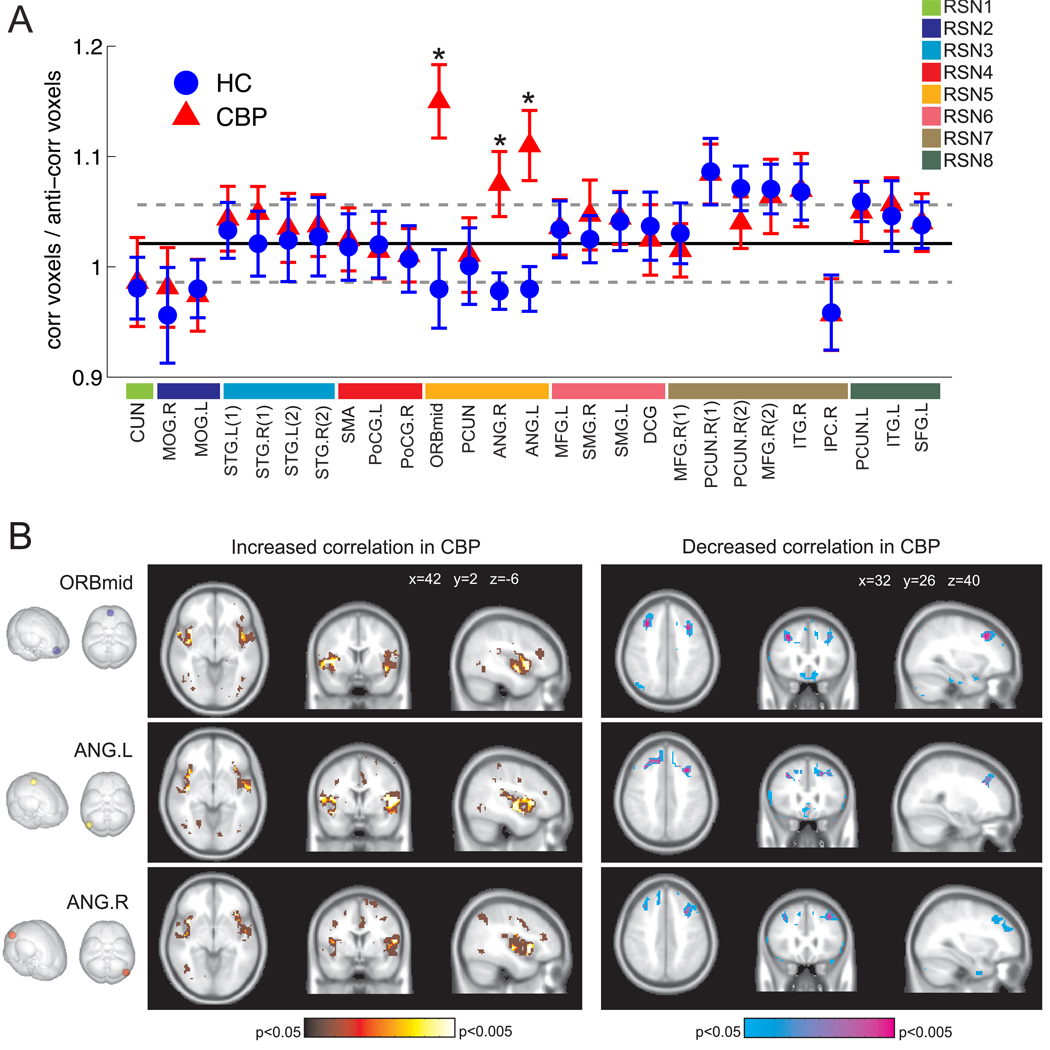

Following Baliki et al. [3] the ratio of positive and negative correlated voxels was computed for all 27 seeds. Using thresholds ranging from ζ = 0.3 to ζ = 1 we found that in the healthy controls all seeds exhibit a correlation ratio equal to 1 with a 10% deviation from unity. However, as depicted in Fig 3A for three of the four sites belonging to the DMN, the correlation balance is significantly increased in the CBP subjects (t-test, p<0.005). These sites are located in orbital part of the middle frontal gyrus (ORBmid) and the right and left angular gyri (ANG.R and ANG.L). The fourth DMN high connectivity site located at the precuneus showed no alteration.

Figure 3.

A. Ratio of positive and negative correlated voxels for all 27 seeds. (*) Indicates significant differences (t-test, p<0.005). B. Spatial maps showing increased (left) and decreased (right) correlations with seeds in ORBmid, ANG.R and ANG.L in CBP (t-test, p<0.05 in red (left) and blue (right), p<0.001 in yellow (left) and purple (right).

To further understand the origin of these alterations in the correlation balance of CBP subjects we computed the maps of those voxels that exhibit increased correlations and decreased correlations in CBP in comparison to the healthy controls (see Fig. 3B). The most notable alterations are significant increases in correlation between ORBmid, ANG.R and ANG.L and the right and left insular cortex in the CBP subjects and decreases in correlation between these three seeds and regions in the middle frontal gyrus. Less significant increases are found for the poles of the superior and middle temporal gyri. (See supplementary figures S4 and S5 for a comparison of the numerical correlations between both groups).

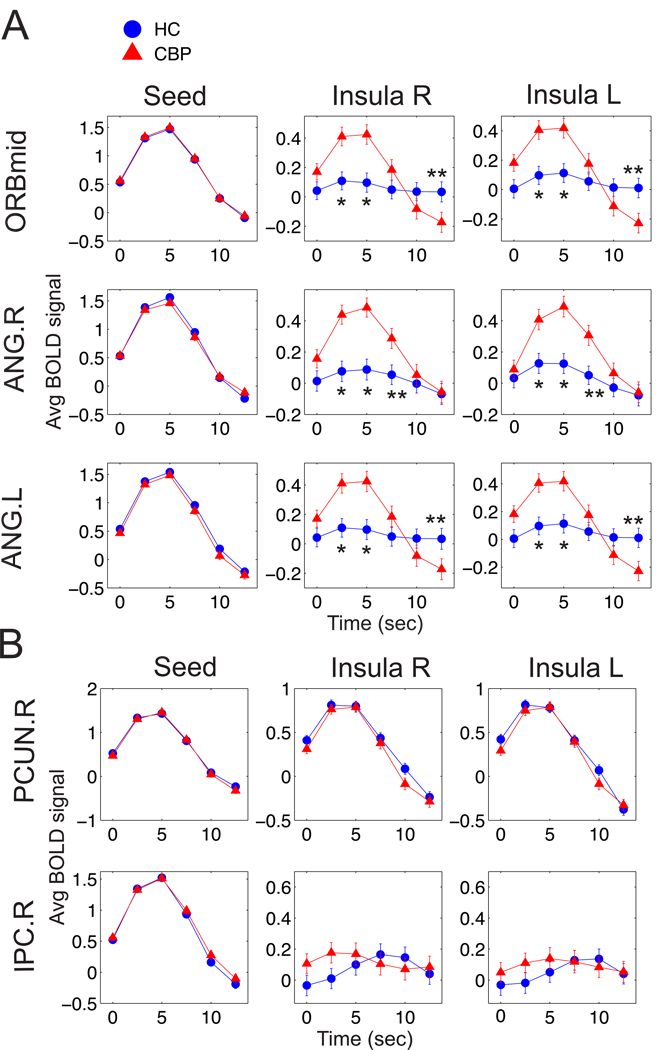

The results so far demonstrate that increases of activity in the seeds located in ORBmid, ANG.R and ANG.L are correlated with the insular cortex in CBP more than in healthy subjects. To gain deeper insight into the nature of these abnormal correlations we computed the average response of the BOLD signal in the insula after significant spontaneous activity increases in selected seeds. This approach is similar to that used for event-triggered average [9], but here the BOLD signal is averaged for a time window (12.5 sec) after it crosses an arbitrary positive threshold (here set at one standard deviation). The triggered averages shown in Fig. 4A for the three seeds which exhibited broken correlation balance present striking differences for CBP while the one for the fourth DMN’ seed (PCUN) -which preserved correlation balance- behaved as the control. As an additional control we show here the result for a site located outside the DMN (IPC).

Figure 4.

BOLD signal averages triggered by spontaneous increases in the BOLD signal at ORBmid, ANG.R and ANG.L. (approx. 250 events) A. Triggered averages computed in the seeds and in the insular cortices (columns indicate the brain regions where the average is computed, and rows the regions where the events triggering the averaging occur). B. Similar analysis for two sites which do not exhibit broken correlation balance (PCUN.R and IPC). Asterisks indicate t-test significant differences: (*) for p<0.05 and (**) for p<0.005.

The triggered averages show that the CBP patients population exhibit significant spontaneous coactivation between the seeds and the insula, while for the healthy controls remains close to zero for all the three DMN' seeds (see Fig. 4A). The insula coactivation is only observed for the three regions shown previously in Fig. 3A to exhibit correlations ratios larger than unity. As a control, Fig. 4B illustrates the case of two regions which have similar correlation balance and consequently exhibit similar triggered averages (a full analysis is presented as Supp. Material).

Overall, this is the first report demonstrating abnormal DMN dynamics in CBP patients derived from resting state functional data. Despite the different settings, the results match those previously reported in Baliki et al., [3] during a task. Thus, correlation balance is broken in the DMN both at rest and during the execution of a simple task, implying that large areas of the brain show increased coactivation with the DMN in CBP, while others show decreased coactivation. This new observation is consistent with previous data showing that functional connectivity during attention demanding tasks resembles that of the resting state [11,17]. Additionally, a strong correspondence between patterns of brain activity seen during activation (performance of normal cognitive functions) and rest has been recently reported [27]. The present results provide independent evidence about this correspondence by identifying similar changes in a chronic condition, during rest and during an attention task [3].

The use of the same cohort than in a previous study [3] limits the results generalization calling for a replication on another population. Another concern could be a possible "bleed through” effect [28] by which the resting brain could be primed by a previous task. Although the task/rest sequence here was randomized these factors need to be accounted in future studies.

A possible interpretation of the present results is that long-term pain alters anatomical brain connectivity and these changes are reflected in the spontaneous fluctuations of brain activity a hypothesis that has received experimental support by recent imaging studies of chronic pain patients [14,23]. The observed increase of correlation between sites in the DMN, the insular cortices and poles of the middle and superior temporal gyri are consistent with previous findings linking these regions with the processing of persistent pain [2] and the emotional modulation of pain [15]. In particular, there is extensive evidence supporting the hypothesis that insula plays a prominent role in the evaluation of pain intensity and introspection in general [8]. It is thus reasonable that enduring pain behaviour reinforces connectivity between these cortical areas and the DMN, linked to introspection and self-referential thought.

In summary, using two self-consistent approaches we found that resting brain dynamics exhibit altered coactivation of the DMN with regions in the middle frontal gyrus (located in the RSN associated with executive control). This is consistent with previous descriptions of decision-making and executive disabilities in CBP patients [1,3]. Additionally, the study of the correlation balance in the most connected sites of a standard independent component decomposition of brain activity, reveals that in CBP patients is disrupted the correlation balance between hubs of the DMN but other hubs in the rest of the RSNs are spared. This result provides further characterization of CBP as a condition affecting the DMN and helps to narrow the search of a single mechanism behind the chronic pain impact over the brain function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Work supported by NIH of USA, grant NS58661 and by CONICET. E.T. was supported by an Estimulo Fellowship from the University of Buenos Aires. Data collection was funded by grant NS35115 (awarded to A.V. Apkarian) by NIH. We thank P. Montoya, O. Scremin, M. Zirovich, T. Victor and P. Bharath for comments.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Apkarian AV, Sosa Y, Krauss BR, Thomas PS, Fredrickson BE, Levy RE, Harden R, Chialvo DR. Chronic pain patients are impaired on an emotional decision-making task. Pain. 2004;108:129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apkarian AV, Bushnell MC, Treede RD, Zubieta JK. Human brain mechanisms of pain perception and regulation in health and disease. Eur J Pain. 2005;9:463–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baliki MN, Geha PY, Apkarian AV, Chialvo DR. Beyond feeling: chronic pain hurts the brain, disrupting the default-mode network dynamics. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1398–1403. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4123-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beckmann CF, Smith SM. Probabilistic independent component analysis for functional magnetic resonance imaging. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 2004;23:137–152. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2003.822821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beckmann CF, DeLuca M, Devlin JT, Smith SM. Investigations into resting-state connectivity using independent component analysis. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2005;360:1001–1013. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buckner RL, Sepulcre J, Talukdar T, Krienen FM, Liu H, Hedden T, Andrews-Hanna JR, Sperling RA, Johnson KA. Cortical hubs revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity: mapping, assessment of stability, and relation to Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1860–1873. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5062-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cordes D, Haughton VM, Arfanakis K, Carew JD, Turski PA, Moritz CH, Quigley MA, Meyerand ME. Frequencies contributing to functional connectivity in the cerebral cortex in “resting-state” data. Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:1326–1333. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Critchley HD, Wiens S, Rotshtein P, Ohman A, Dolan RJ. Neural systems supporting interoceptive awareness. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:189–195. doi: 10.1038/nn1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Boer, Kuyper Triggered Correlation. IEEE Transact Biomed Eng. 1968;15:169–179. doi: 10.1109/tbme.1968.4502561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Derbyshire SW. Meta-analysis of thirty-four independent samples studied using PET reveals a significantly attenuated central response to noxious stimulation in clinical pain patients. Curr Rev Pain. 1999;3:265–280. doi: 10.1007/s11916-999-0044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fox MD, Raichle ME. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9673–9678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504136102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fox MD, Raichle ME. Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Rev Neurosc. 2007;8:700–711. doi: 10.1038/nrn2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fransson P, Marrelec G. The precuneus/posterior cingulate cortex plays a pivotal role in the default mode network: Evidence from a partial correlation network analysis. Neuroimage. 2008;42:1178–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geha PY, Baliki MN, Harden RN, Bauer WR, Parrish TB, Apkarian AV. The brain in chronic CRPS pain: abnormal gray-white matter interactions in emotional and autonomic regions. Neuron. 2008;60:570–581. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Godinho F, Magnin M, Frot M, Perchet C, García-Larrea L. Emotional modulation of pain: Is it the sensation or what we recall? J Neurosci. 2006;26:11454–11461. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2260-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong G, He Y, Concha L, Lebel C, Gross DW, Evans AC, Beaulieu C. Mapping anatomical connectivity patterns of human cerebral cortex using in vivo diffusion tensor imaging tractography. Cerebral Cortex. 2009;19:524–536. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greicius MD, Krasnow B, Reiss AL, Menon V. Functional connectivity in the resting state brain: a network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:253–258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135058100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greicius MD, Flores BH, Menon V, Glover GH, Solvason HB, Kenna H, Reiss AL, Schatzberg AF. Resting-state functional connectivity in major depression: abnormally increased contributions from subgenual cingulate cortex and thalamus. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hagmann P, Cammoun L, Gigandet X, Meuli R, Honey CJ, Wedeen VJ, Sporns O. Mapping the structural core of human cerebral cortex. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iturria-Medina Y, Sotero RC, Canales-Rodriguez EJ, Aleman-Gomez Y, Melie-García L. Studying the human brain anatomical network via diffusion-weighted MRI and graph theory. Neuroimage. 2008;40:1064–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jezzard P, Mathews P, Smith SM. Functional MRI: An introduction to methods. Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malinen S, Vartiainen N, Hlushchuk Y, Koskinen M, Ramkumar P, Forss N, Kalso E, Hari R. Aberrant temporal and spatial brain activity during rest in patients with chronic pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:6493–6497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001504107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.May A. Chronic pain may change the structure of the brain. Pain. 2009;137:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peyron R, Laurent B, García-Larrea L. Functional imaging of brain responses to pain. A review and meta-analysis (2000) Neurophysiol Clin. 2000;30:263–288. doi: 10.1016/s0987-7053(00)00227-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, Shulman GL. A default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:676–682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salvador R, Suckling J, Coleman MR, Pickard JD, Menon D, Bullmore ET. Neurophysiological architecture of functional magnetic resonance images of human brain. Cerebral Cortex. 2005;15:1332–1342. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith SM, Fox PT, Miller KL, Glahn DC, Fox PM, Mackay CE, Filippini N, Watkins KE, Toro R, Laird AR, Beckmann CF. Correspondence of the brain's functional architecture during activation and rest. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13040–13045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905267106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stevens WD, Buckner RL, Schacter DL. Correlated Low-Frequency BOLD Fluctuations in the Resting Human Brain Are Modulated by Recent Experience in Category-Preferential Visual Regions. Cerebral Cortex. 2009 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp270. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhp270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van den Heuvel MP, Stam CJ, Boersma M, Hulshoff Pol HE. Small-world and scale-free organization of voxel-based resting-state functional connectivity in the human brain. Neuroimage. 2008;43:528–539. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vincent JL, Patel GH, Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Baker JT, Van Essen DC, Zempel JM, Snyder LH, Corbetta M, Raichle ME. Intrinsic functional architecture in the anesthetized monkey brain. Nature. 2007;447:83–85. doi: 10.1038/nature05758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.