Abstract

The Mixed Lineage Leukemia (MLL) gene is disrupted by chromosomal translocations in acute leukemia, producing a fusion oncogene with altered properties relative to the wild-type gene. Murine loss-of-function studies have demonstrated an essential role for Mll in developing the haematopoietic system, yet studies using different conditional knockout models have yielded conflicting results regarding the requirement for Mll during adult steady-state haematopoiesis. Here, we employ a loxP-flanked Mll allele (MllF) and a developmentally-regulated, haematopoietic-specific VavCre transgene to re-assess the consequences of Mll loss in the haematopoietic lineage, without the need for inducers of Cre recombinase. We show that VavCre;Mll mutants exhibit phenotypically normal fetal haematopoiesis, but rarely survive past 3 weeks of age. Surviving animals are anemic, thrombocytopenic and exhibit a significant reduction in bone marrow haematopoietic stem/progenitor populations, consistent with our previous findings using the inducible Mx1Cre transgene. Furthermore, the analysis of VavCre mutants revealed additional defects in B-lymphopoiesis that could not be assessed using Mx1Cre-mediated Mll deletion. Collectively, these data support the conclusion that Mll plays an essential role in sustaining postnatal haematopoiesis.

Keywords: haematopoiesis, MLL, Vav, leukemia, interferon, stem cells

Introduction

The treatment of childhood leukemia has improved dramatically in the last five decades. However, patients with certain cytogenetic abnormalities do not effectively respond to conventional chemotherapy, particularly those defined by translocations in the Mixed Lineage Leukemia (MLL) locus at 11q23. It remains unclear why this group has a particularly poor outcome independent from patient age.(1) Significant advances have been made in understanding the molecular consequences of 11q23 translocations using mouse models, but the need for new strategies to target this cytogenetically-defined group of leukemias justifies further investigation into molecular pathways regulated by MLL.(2)

The protein encoded by the MLL gene (Mll1 in mouse) is a large nuclear chromatin-modifying protein that encodes histone methyltransferase activity.(3, 4) In addition to its methyltransferase activity, MLL possesses sequence-nonspecific DNA recognition motifs(5–7) and chromatin recognition motifs.(8, 9) Much of the chromatin-targeting activity is retained in the N-terminus and is thus shared between MLL and oncogenic MLL fusion proteins. Therefore, it is not surprising that many genes identified as over-expressed in cells harboring MLL translocations are also natural MLL target genes.(10) The extent to which MLL fusion proteins simply hyper-activate a natural MLL-dependent haematopoietic program or alternatively, exhibit neomorphic activity (acquiring and deregulating new target genes), remains unclear, but this distinction is critical for the development of targeted therapeutics.

To understand the normal role of wild-type Mll gene in the haematopoietic system, our group and others have performed gene disruption experiments to generate loss-of-function alleles using a variety of strategies.(11–15) Due to the large and complex nature of the Mll1 locus, none of these gene disruptions produce null alleles, and all (with the exception of the SET domain deletion(14)) result in embryonic lethality when homozygous. The age of embryonic lethality varies amongst alleles, suggesting that residual function of the different alleles may cause the variable results reported. Furthermore, Mll expression in the embryo is dynamic and widespread and the cause of lethality has not been clearly elucidated. For these reasons, we and others(15) have developed conditional knockout alleles to more precisely assess the role of Mll in adult haematopoietic cell types and in other tissues.

To produce a conditional loss-of-function allele, our group generated an Mll allele in which exons 3 and 4 are loxP-flanked (MllF, reference (16)). We demonstrated that the excision of exons 3 and 4 (producing the MllΔN allele) results in an in-frame deletion and the resulting MLLΔN protein can not be imported into the nucleus due to the loss of nuclear localization motifs. The cytoplasmic localization was demonstrated in cells expressing an epitope tagged version of the MLLΔN protein as well as in Mll-deleted primary cells.(16) In addition, the AT hooks(5), methylation status-specific DNA recognition motifs(6, 7), and subnuclear targeting motifs(17) are lacking in the MLLΔN protein. These motifs are essential for transformation in the context of MLL-ENL fusion oncoproteins.(6) In an independent study, McMahon et al. generated an MllF allele in which exons 8 and 9 are excised, also resulting in an in-frame deletion. The protein produced from this allele is likely unstable; MLL is undetectable by immunoblot in mutant fetal liver extracts.(15) Interestingly, both gene disruption strategies result in several very similar phenotypes such as embryonic lethality of germline homozygotes beginning at ~E12.5, inefficient fetal liver haematopoiesis and adult bone marrow cells that fail to engraft secondary recipients. However, one significant phenotypic difference distinguished these two conditional knockout models. In the McMahon et al. study, the pan-haematopoietic, VavCre-mediated deletion resulted in efficient Mll excision in all haematopoietic cells, with no effect on steady-state haematopoietic populations. Despite normal steady-state haematopoiesis, bone marrow cells from these animals exhibited a severe defect in engrafting secondary recipients. Thus, based on this mouse model, the authors concluded that Mll is only required for the process of regenerating the haematopoietic system but not for steady-state haematopoiesis.(15) In contrast, our studies using the inducible Mx1Cre transgene(18) demonstrated an absolute requirement for Mll in steady-state as well as regenerative haematopoiesis. We observed a significant reduction in haematopoietic stem cell (HSC) function as early as 4 days after deletion of Mll followed by a rapid decline in most bone marrow cells and lethality 2–3 weeks after deletion.(16)

Two major differences between these mouse models may account for the different conclusions. First, the proteins encoded by the two different alleles may retain some quantitatively or qualitatively different residual functions. Second, the method of excision (Mx1Cre versus VavCre) may impact on the effects of Mll loss. The Mx1Cre transgene is widely used to evade embryonic lethality and introduce Cre-mediated gene manipulations into the haematopoietic system.(19) The induction of Cre expression is initiated in adult animals by the injection of polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (pI:pC), a double stranded (ds) RNA analog. Toll-like receptor 3 mediated recognition of ds RNA initiates the expression of type I interferons (IFNs), which result in the activation of the Mx1Cre transgene.(18) Systemic IFNs affect many developing and mature haematopoietic cell types, often limiting the use of the Mx1Cre model to periods after recovery from transient pI:pC-initiated nonspecific effects. Type I IFNs are potent inhibitors of normal haematopoietic cell progenitor growth including lymphoid,(20, 21) erythroid and myeloid cell types.(22, 23) In addition, a pro-proliferative role of IFNα on HSCs has been demonstrated recently.(24, 25) Therefore, any assessment of haematopoietic phenotypes using the Mx1Cre model should take into account the potential for combined effects of the engineered mutation and IFN signaling.

Since targeting MLL fusion oncoproteins may include strategies that inadvertently target endogenous MLL, it is important to determine whether the inhibition of endogenous MLL activity could be tolerated. Therefore, the objective of this study was to re-assess the role of Mll in adult and fetal haematopoiesis using a method not requiring induction of IFNs. To this end, we generated and analyzed animals in which haematopoietic-specific Mll excision is achieved using a VavCre transgene. Here we show that the developmentally-regulated excision of our MllF allele largely phenocopies the acute excision using the Mx1Cre transgene, supporting the conclusion that Mll is required to sustain adult steady-state haematopoiesis.

Materials and methods

Animals

Mice were maintained in compliance with the Dartmouth Animal Resources Center and I.A.C.U.C. policies. MllF alleles and gene targeting have been described.(13) MllΔN animals were generated by crossing EIIa-Cre transgenics (Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, ME) to MllF animals and selecting progeny that transmitted the deleted (MllΔN) version of the allele. VavCre mice were obtained from Hanna Mikkola (University of California, Los Angeles) with permission from Thomas Graf (Center for Genomic Regulation, Barcelona, Spain). Rosa26-YFP (RosaYFP) reporter mice were obtained from Jackson Labs (stock # 006148). Embryo age was defined as day 0.5 at 8 A.M. the day of plug observation. To screen out germline and mosaic expression of the VavCre transgene, embryos harboring the RosaYFP allele were imaged after dissection or non-haematopoietic tissues were assessed for Mll excision using a quantitative genomic PCR assay(16) using tail, limb bud, somite or head genomic DNA. A similar approach was used to screen adult VavCre animals, using ear, tail or liver genomic DNA.

Flow cytometry and differential blood counts

Bone marrow cells were prepared and lineage staining was performed as previously described(16) except that the F’ab2 anti-rat conjugate was a PE-Cy5.5 reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Splenocytes and thymocytes were prepared by trituration through a 40-micron nylon filter. For splenocytes and bone marrow, RBC lysis buffer (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) was used to remove red blood cells. For adult bone marrow, lineage cocktail consisted of unlabeled rat anti-Gr-1, Mac-1, IL7Rα, Ter119, CD3, CD4, CD8, B220 and CD19, all from Invitrogen except that IL-7Rα antibody was obtained from eBioscience. For the fetal liver analyses, lineage cocktail lacked the Mac-1 antibody. In some experiments, goat anti-rat APC (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) was used in conjunction with Sca-1 biotin, c-Kit PE, CD48 FITC and streptavidin-PECy5.5 all from BD Biosciences. T cell analyses utilized anti-CD3, CD4, CD8, CD25, CD44, CD45.1 and CD45.2 from BD Biosciences or eBioscience. Flow cytometry was performed with a FACSCalibur or FACSAria (BD Biosciences) and data was analyzed using FlowJo Software (TreeStar Inc., Ashland, OR). Peripheral blood collected from the peri-orbital sinus was analyzed using a Hemavet 950 blood analyzer (Drew Scientific, Inc., Dallas, TX).

In vitro colony assays and transplantation experiments

Colony assays to enumerate myelo-erythroid CFU were performed by plating unfractionated fetal liver or bone marrow cells in 1 mL M3434 (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) in duplicate. Total colonies were enumerated 6–7 days after plating. Competitive transplantation assays were performed using C57Bl/6 female mice irradiated with a split dose of 950 Rads. Each recipient received 2×105 protective C57Bl/6 bone marrow cells and either 5×104 or 5×105 fetal liver cells. Engraftment was assessed by the presence of Ly5.1+ (fetal donor) cells in the peripheral blood of recipients by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis and software

Unless otherwise indicated, unpaired Student’s T tests were used to calculate p values. All error bars represent 95% confidence intervals unless otherwise indicated in the figure legend. Graphs and statistical tests were performed using Prism (Graphpad, La Jolla, CA) or Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA).

Histology and imaging

For bone marrow sections, the sternum was removed, cleaned and transferred to Bouin’s fixative overnight at 4°C. Fixed samples were processed by the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Rodent Histopathology Core Facility. Samples were imaged on a Nikon Optiphot-2 microscope using 10× and 40× objectives for a total magnification of 100× and 400×. Images were manipulated using Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator software (Adobe Systems, Inc., San Jose, CA). Embryo images were acquired on a Leica MZFIII stereomicroscope using a GFP-470 filter (Chroma Technology, Bellows Falls, VT), Color Mosaic 11.2 camera and Spot Insight 4.0 software (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI). Total magnification was 6.3×–8×.

Results

VavCre-mediated gene deletion becomes fully penetrant by embryonic day (E) 13.5

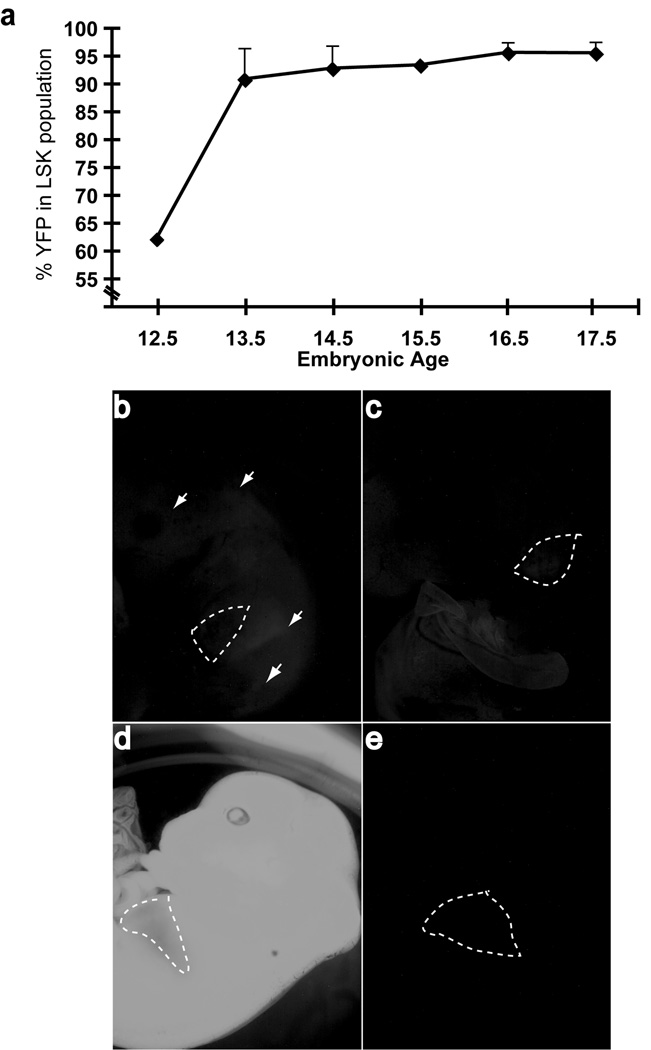

Several groups have generated Cre recombinase-expressing transgenic animals using regulatory elements of the vav1 gene.(26–29) To determine the first point at which VavCre-mediated excision becomes fully penetrant in an HSC-enriched population, we analyzed fetal livers from wild type VavCre embryos harboring the RosaYFP reporter gene. Excision of RosaYFP increased rapidly from E12.5 in lineage-negative, Sca-1+c-Kit+ (LSK) cells, approaching 100% at E13.5 (Fig. 1a). Depending on the regulatory elements used, vav transgenes have been observed to exhibit variegated or ectopic expression.(26, 28, 29) We observed that up to 20% of the progeny of VavCre;MllF/+ × MllF/F crosses had undergone either germline excision (most tissues had undergone Mll excision) or mosaic excision (patchy excision outside the haematopoietic system). The remaining animals exhibited faithful expression of the VavCre transgene exclusively in the fetal liver at E13.5. The aberrant excision was most apparent when embryos harbored the RosaYFP allele to visualize all tissues in which Cre expression had occurred (Fig. 1b–e). To reduce the mosaic and germline expression of the VavCre transgene, an alternative breeding strategy was also used (VavCre;MllΔN/+ × MllF/F). In this strategy, the animal that harbored the Vav transgene also had one “pre-deleted” Mll allele (MllΔN), thus avoiding Mll excision through ectopic VavCre activity in germ cells, as had been previously reported.(26, 28) This strategy increased the number of animals exhibiting haematopoietic-specific Mll excision and also increased the penetrance of the phenotypes observed.

Figure 1. History of VavCre transgene expression in fetal liver LSK cells.

a) Embryos resulting from VavCre X RosaYFP crosses were collected at the embryonic days indicated on the x-axis and the YFP+ percentage within the LSK population of the fetal liver was determined by flow cytometry. Each point represents the average of individual embryos (n=1–4, error bars represent standard deviation). Lower panels, three distinct patterns for VavCre expression were observed: b) mosaic expression, characterized by the lack of liver-specific YFP signal in conjunction with patches of YFP signal throughout the embryo, c) true, haematopoietic-specific expression of VavCre, exemplified by a bright YFP signal in the fetal liver only, obscuring the normally red liver, d) germline excision was clearly visible as a completely bright YFP+ embryo, and e) an embryo that did not inherit the VavCre transgene is shown as a negative control. The liver is outlined by dashed white lines. Embryos between E13.5 and E16.5 are used as examples.

Normal fetal haematopoietic expansion in VavCre;Mll mutant embryos

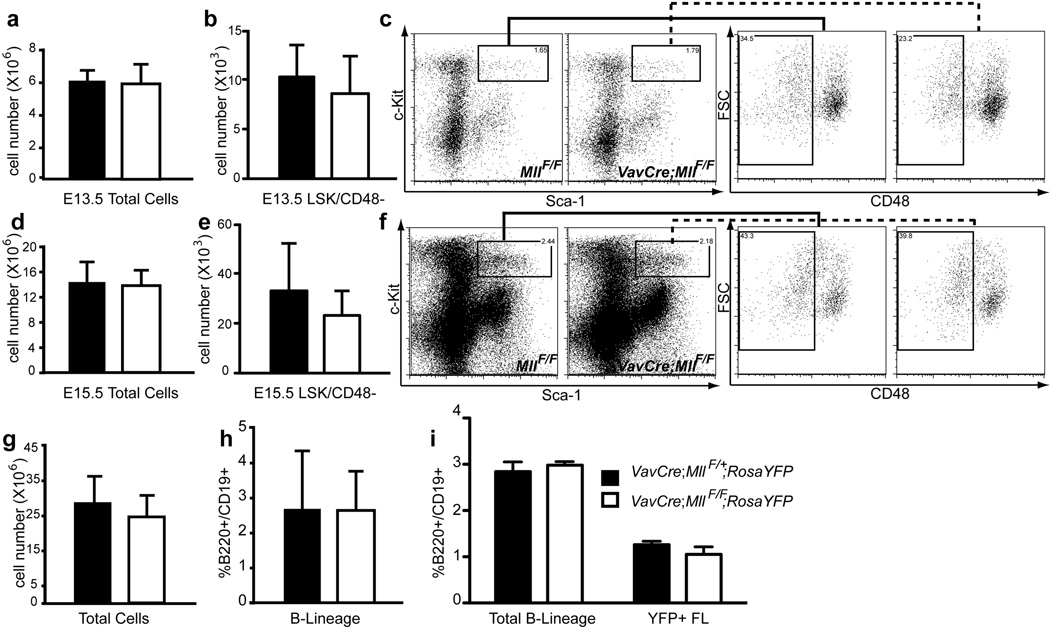

Using germline Mll alleles, several groups have reported inefficient fetal liver haematopoiesis.(15, 30) To determine whether the loss of Mll exclusively in developing haematopoietic cells results in a similar effect on fetal liver cellularity, we analyzed fetal haematopoiesis in VavCre;MllF/F embryos from E13.5 to E17.5, with and without the RosaYFP allele. Although full penetrance of Cre excision in the fetal liver is achieved by E13.5, no reduction in cellularity was observed, even by E15.5 in either VavCre;MllF/F or VavCre;MllΔN/F embryos (Fig. 2a, d, g). Furthermore, the HSC-enriched LSK/CD48-negative population(31) was also not reduced (Fig. 2b, c, e, f). In contrast to the significant decrease in B cells in adult mutant mice (see Fig. 5–6), a comparable number of B220+CD19+ cells were observed in VavCre;Mll mutant relative to wild type fetal livers (Fig. 2h). This was also true within the YFP-gated population, further demonstrating that cells that had expressed Cre recombinase were equally able to generate B-lineage cells in vivo (Fig. 2i). Thus, haematopoietic-specific loss of Mll during development does not hinder haematopoietic expansion or the generation of B-lineage cells in the fetal liver.

Figure 2. Normal cell expansion in Mll-deficient fetal livers.

Fetal liver cells were analyzed at E13.5 (a–c), 14.5 (i) E15.5 (d–f, g–h, j). One of three breeding strategies was used to produce Mll-deficient embryos: VavCre;MllΔN/+ X MllF/F (panels a–f), VavCre;MllF/+ X MllF/F (panels g–h) or VavCre;MllF/+ X MllF/F;RosaYFP (panel i). a) Average total number of fetal liver cells per E13.5 embryo. Black bars represent control littermates (Cre negative and VavCre;MllF/+ animals) and white bars represent VavCre;MllΔN/F embryos in panels a–f or VavCre;MllF/F embryos in panels g–i. b) Average number of LSK/CD48-negative cells in E13.5 fetal livers. c) Representative example of LSK/CD48 FACS data used in panel b. Cells displayed in the first plot are gated as lineage-negative and the solid or dashed lines indicate the gate for the second plots (forward scatter versus CD48). d) Average number of total fetal liver cells per E15.5 embryo. e) Average number of fetal LSK/CD48-negative cells per E15.5 fetal liver. f) Representative example of LSK/CD48 FACS data used in panel e. Gating strategy is the same as in panel c. g) Average total number of E15.5 fetal liver cells. h) Average percentage of B220+/CD19+ cells within the E15.5 fetal livers shown in g. i) Average percentages of B220+/CD19+ cells in E14.5 fetal livers, or within YFP-gated fetal liver cells (YFP+ FL). For experiments in panels a–i, n=3–7 embryos and p>0.1.

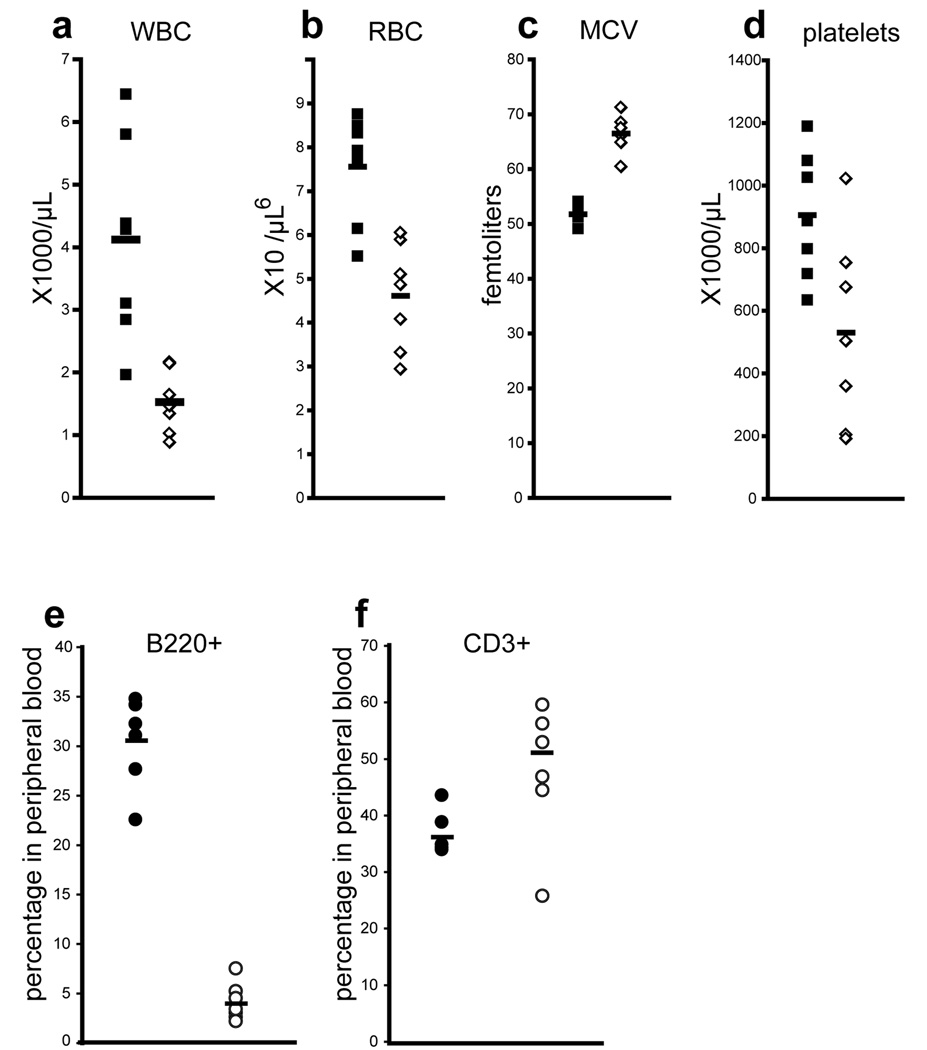

Figure 5. Adult VavCre;MllF/F mice exhibit multi-lineage defects in steady-state haematopoiesis.

Peripheral blood cell counts were determined for 3–5 week old control MllF/F animals (black symbols) and littermate VavCre;MllF/F animals (white symbols). Mosaic animals were excluded from this analysis as described in the Methods. White blood cells, WBC; red blood cells, RBC; mean corpuscular volume, MCV; and platelets are represented. e–f) Flow cytometry analysis was performed to quantify e) B (B220+) and f) T cells (CD3+) in the peripheral blood. At least seven animals of each genotype were analyzed. Averages are represented by horizontal bars.

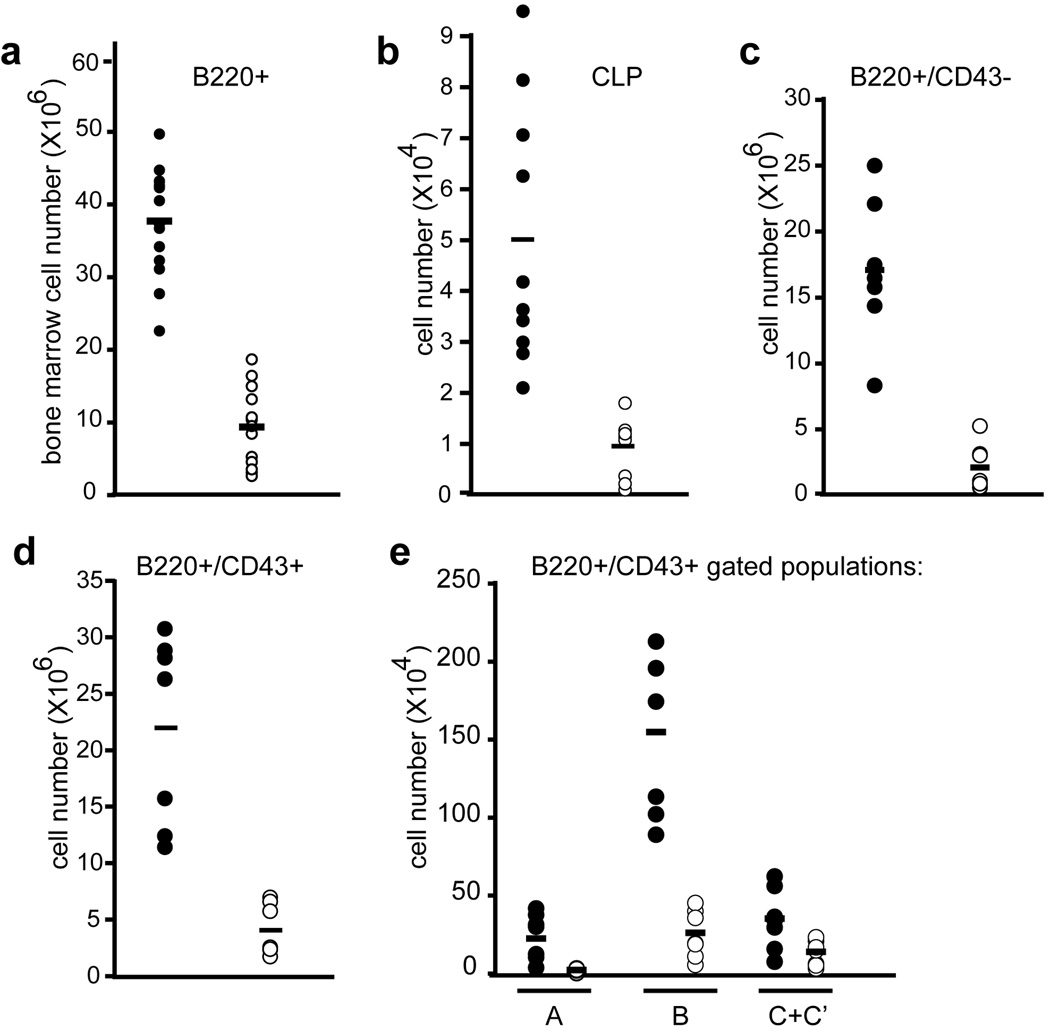

Figure 6. Developing and peripheral lymphoid populations are reduced in VavCre;MllF/F animals.

a) Quantification of developing B cells in the bone marrow; total number of B220+ cells in both hind limbs is shown. b) Common lymphoid progenitor (CLP; lineage-negative, IL7Rα+, c-Kit+, Sca-1+) absolute number per 2 hindlimbs is shown. c–e) B cell populations indicated below each graph are shown as absolute cell number per 2 hindlimbs. Hardy fractions A–C’ are defined by BP1 and CD24 staining as indicated in Supplementary Figure 5. All data was obtained using control MllF/F animals (filled symbols) and littermate VavCre;MllF/F animals (open symbols) with 6–15 animals representing each genotype. The average values are represented by horizontal bars.

Function of Mll-deficient fetal haematopoietic cells

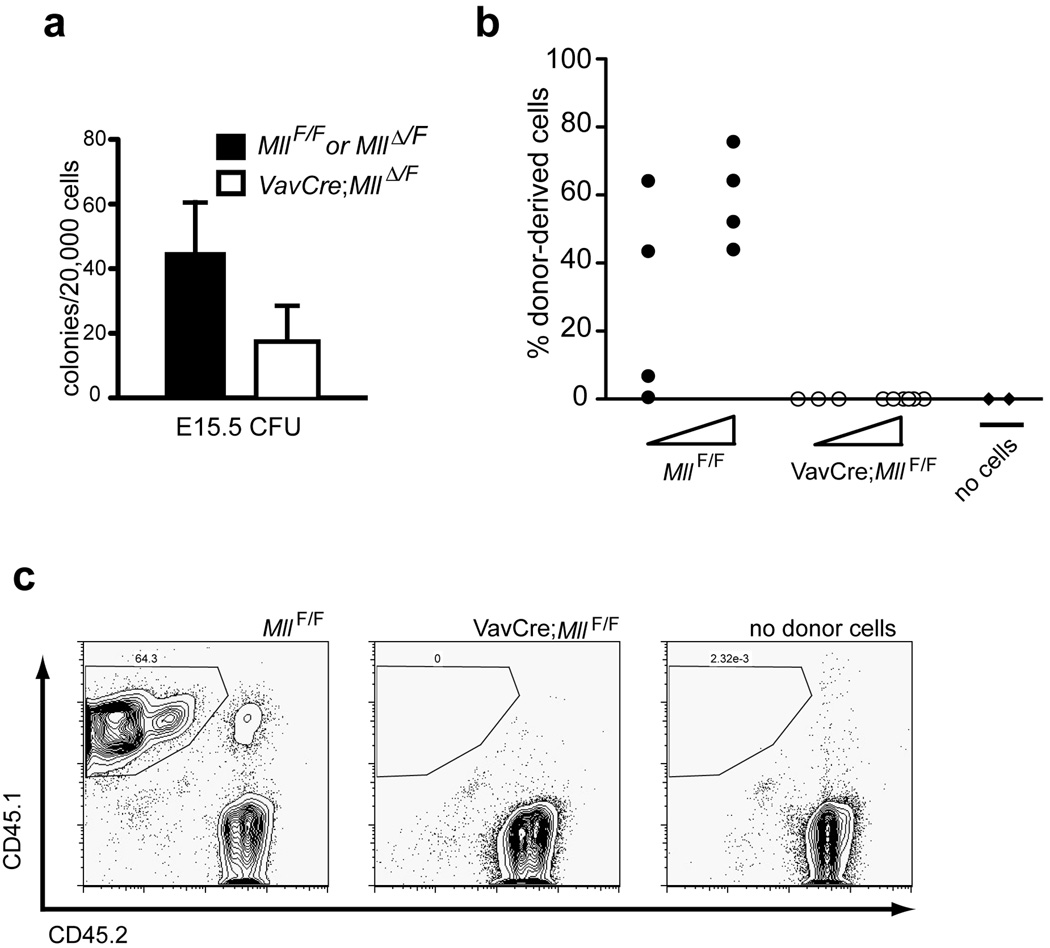

The surprisingly normal fetal haematopoietic development in VavCre;Mll mutants prompted us to test these cells in several quantitative functional assays, including myelo-erythroid colony assays (colony-forming units, CFU) and competitive transplantation assays. Similar to our observations using adult bone marrow(16), we found that Mll-deficient fetal liver cells yielded 2.6-fold reduced CFU relative to littermate controls (Fig. 3a). We also performed competitive engraftment assays using VavCre;MllF/F fetal liver cells. In these experiments, we could not detect VavCre;MllF/F embryo-derived cells in the peripheral blood of recipients, even as early as 4 weeks post-transplant (Fig. 3b–c). These data illustrate that despite the normal phenotype and developmental expansion of fetal haematopoietic cells, Mll-deficient stem and progenitor cells are functionally impaired, particularly in their ability to engraft into an adult environment.

Figure 3. Defects in VavCre;Mll mutant fetal haematopoietic cells.

a) Haematopoietic colonies obtained by plating 2×104 total E15.5 fetal liver cells from control or VavCre;MllΔN/F embryos as indicated in the legend. Cells were plated in methylcellulose supplemented with cytokines to support myelo-erythroid cell types (M3434) and colonies were counted 7 days after plating. Averages represent duplicate plates per embryo and 3 embryos per genotype. The p value is 0.005 for this comparison. Mosaic and germline embryos were excluded from all analyses as indicated in the Methods. b) Results of competitive transplantation experiments using VavCre;MllF/F E16.5 embryo fetal liver cells. Donor fetal liver cells (CD45.1+) were transplanted into lethally irradiated C57Bl/6 (CD45.2+) recipients at two doses (5×104 or 5×105) indicated by the triangle below each set of data points. Fetal liver cells were transplanted together with 2×105 protective C57Bl/6 bone marrow cells, and each donor was transplanted into 4–8 recipients. The data shown represents percentage of donor-derived (CD45.1+) cells in the peripheral blood of individual recipient animals at 4 weeks post-engraftment as determined by flow cytometry. c) Representative example of flow cytometry results used in panel b. Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments representing 4 individual donor embryos and 40 recipients. No cells represents animals transplanted with protective C57Bl/6 bone marrow only.

Postnatal multi-lineage haematopoietic defects in VavCre;Mll mutants

In contrast to the embryonic lethality observed in germline Mll mutants(11, 13, 15) VavCre;Mll mutants were born (Table 1), but postnatal differences between these mutants and their littermates became immediately apparent. Our first attempts to produce adult mutant animals utilized the VavCre;MllF/+ × MllF/F breeding strategy. The genotypes of 3-week old animals revealed less than half the expected Mendelian ratio of VavCre;MllF/F animals (Table 1). The surviving mutant animals were smaller than their littermates (Supplementary Figure S1) and exhibited incomplete gene excision in bone marrow and thymocyte populations (Supplementary Figure S2–S3), suggesting that cells escaping Mll deletion contributed to animal survival. Close observation of pups born from this breeding strategy demonstrated that most mutants were moribund or died between 2–3 weeks of age (unpublished data).

Table 1.

Survival of VavCre;Mll mutant animals.

| Genotype | Observed | Expected | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| VavCre;MllF/F | 33 | 64 | 52% |

| VavCre;MllDN/F | 8 | 16 | 50% |

In the first row, the progeny of crosses consisting of VavCre;MllF/+ animals mated to MllF/F animals (with or without the RosaYFP allele) were genotyped at 21 days of age (Observed) and compared to the number based on Mendelian inheritance (Expected). The second line represents the same analyses for the breeding strategy using one germline excised Mll allele (MllΔN) in the female, VavCre;MllΔN/+, crossed to MllF/F males. The percentage of homozygous mutant animals genotyped at 21 days is indicated.

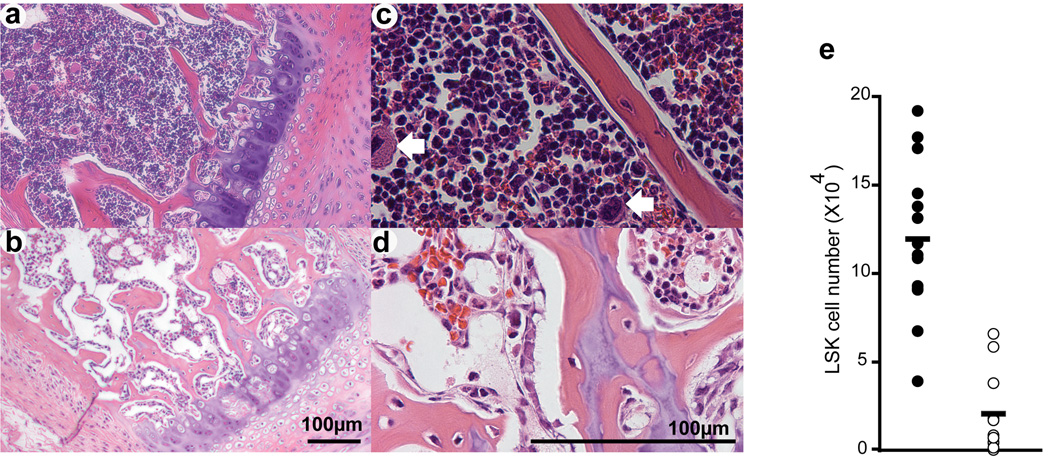

Histological analysis of bone marrow sections illustrated the overall reduced cellularity and also the paucity of megakaryocytes in VavCre;MllF/F animals (Fig. 4a–d, arrows), similar to what we had observed after inducing Mll deletion in adult bone marrow.(16) Enumerating LSK cells in the bone marrow revealed a 6-fold reduction in VavCre;MllF/F animals (Fig. 4e). Examination of the more penetrant VavCre;MllΔN/F animals revealed a >100 fold reduction in all lin−/c-Kit+ cells (Supplementary Figure 4). As a result, all stem and progenitor populations defined by c-Kit expression were severely reduced, and these animals did not survive beyond 3 weeks age. In contrast, some VavCre;MllF/F animals survived beyond this age. Despite the incomplete excision of Mll in these surviving VavCre;MllF/F animals, they afforded an opportunity to assess the effects of Mll loss on multiple lineages in the haematopoietic system without the potentially confounding effects of pI:pC, as had limited our previous studies using Mx1Cre;Mll inducible mutants.

Figure 4. Severe reduction in haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in Mll-deficient bone marrow.

Representative hematoxylin and eosin stained sternum sections of 3 week-old control (a, c; MllF/F) and mutant (b, d; VavCre;MllF/F) animals. Sections are shown at 100× (a, b) and 400× total magnification (c, d). White arrows indicate megakaryocytes in panel c. e) Lineage-negative, c-Kit+, Sca-1+ (LSK) cells in absolute number per 2 hindlimbs is shown. Filled circles represent littermate controls (MllF/F) and mutants (VavCre;MllF/F) are represented by open circles.

Analysis of the peripheral blood of surviving 3–5 week old VavCre;MllF/F mice showed significant deficiencies in white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets, as well as an increased mean red blood cell corpuscular volume (MCV, Fig. 5). These defects were also observed in pI:pC-induced Mx1Cre;MllF/F mice approximately two weeks after inducing Mll deletion (unpublished data and reference (16)). Interestingly, analysis of the peripheral blood of VavCre;MllF/F animals demonstrated a significant decrease in the percentage of circulating B cells, with a slightly elevated percentage of circulating T cells (Fig. 5e–f).

To determine the consequences of VavCre-mediated Mll deletion on developing lymphocytes and lymphocyte progenitors, populations in the bone marrow and thymus were analyzed in the same surviving animals as described above. Total B220+ in the bone marrow were reduced 9-fold (Fig. 6a). Common lymphoid progenitors (CLP, lin−/IL7Rα+/c-Kit+/Sca-1+) were also reduced over 5-fold in VavCre;MllF/F animals (Fig. 6b). More detailed analysis of developing B cells revealed consistent reductions throughout B cell development (Fig. 6c–e, Supplementary Figure 5). However, these data likely underestimate the severity of haematopoietic phenotypes due the poor and variable penetrance of the VavCre transgene particularly in the B cell lineage of VavCre;Mll mutants (Supplementary Fig. 2).

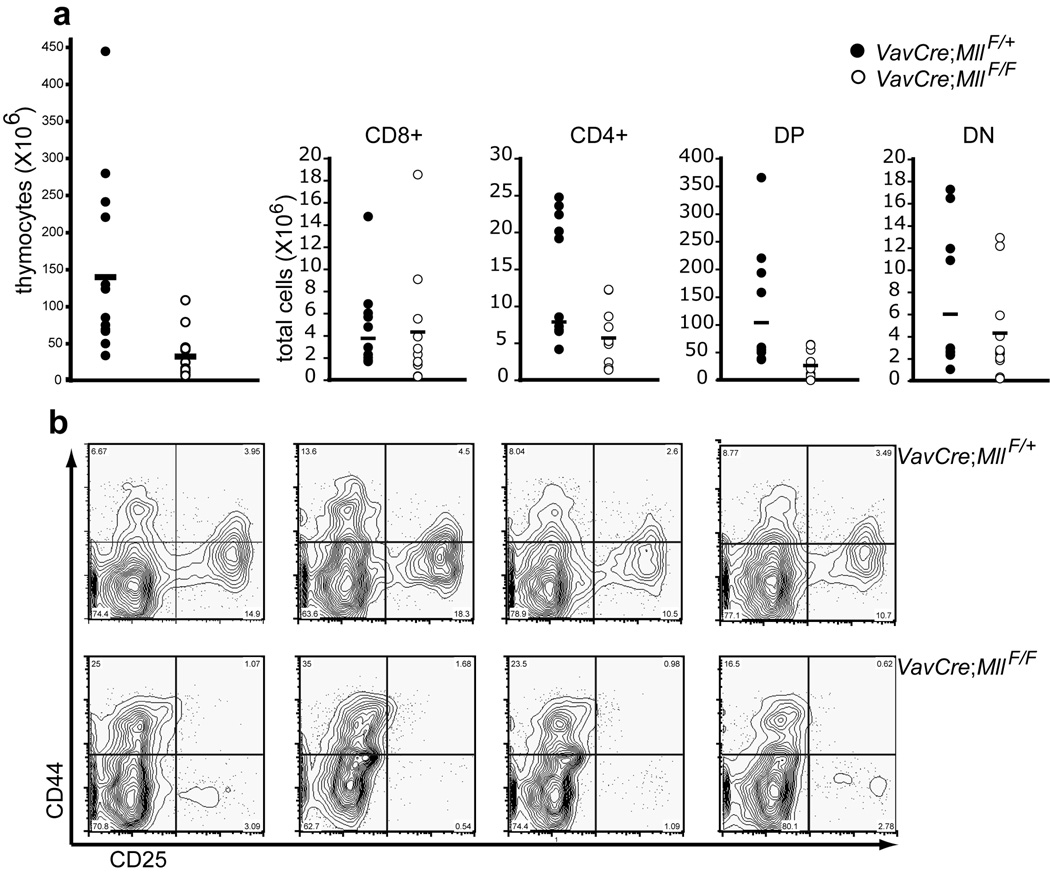

Within the thymus, the reduction in thymocyte number (4.6-fold) was largely attributable to the CD4+/CD8+ double positive population (Fig. 7a). In contrast to B-lineage cells, thymocytes consistently demonstrated high levels of Mll excision (unpublished data) and RosaYFP excision (Supplementary Figure 3). Within the double negative (DN) population, a specific reduction in CD25+ cells was observed (Fig. 7b). Since thymus-seeding cells are within the bone marrow LSK population(32) and this population is significantly reduced in VavCre;MllF/F animals, (Fig. 4e) it is likely that input of progenitors from the bone marrow limits T cell development. In support of this hypothesis, excision of Mll at the DN3–DN4 transition with an LckCre transgene(16) or with a Rag1Cre knock-in (Gan et al. in prep.) had no effect on thymocyte numbers.

Figure 7. Developing T cell populations in the thymus of VavCre;MllF/F animals.

a) Populations of thymocytes were resolved by flow cytometry using CD4 and CD8 antibodies and the absolute number of each subset is shown for control (filled circles) or Mll mutants (open circles). Single-positive CD4 (CD4+) or CD8 (CD8+) are indicated, as are CD4/CD8 double positive (DP) and CD4/CD8 double negative (DN) cells. b) Resolution of DN1–4 populations. CD4 or CD8 expressing thymocytes were excluded from the analysis and CD44 versus CD25 expression is shown on the remaining DN cells. Data from 4 representative animals is shown for the genotypes indicated at the right of each row.

In summary, the developmental excision of Mll in haematopoietic cells results in substantial multi-lineage haematopoietic defects that only become apparent after birth, or by transplanting cells into an adult animal. Using a breeding strategy that results in the more penetrant phenotypes (VavCre;MllΔ/F), most animals succumb to bone marrow failure between birth and 3 weeks of age. However, examination of adult animals harboring a less penetrant allele combination (VavCre;MllF/F) revealed additional defects in B cell development. Collectively, these data support the conclusion that Mll1 is essential for the establishment and maintenance of adult haematopoiesis.

Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to re-assess the severity of Mll deficiency in the absence of the potential confounding effects of systemic IFNs. Using the developmentally regulated VavCre transgene, we demonstrate that animals lacking Mll specifically in haematopoietic cells exhibit a range of haematopoietic phenotypes very similar to those we observed upon acute excision of Mll using the Mx1Cre transgene. These include hypocellular bone marrow, a dramatic reduction in the number of primitive (c-Kit+, lineage negative) haematopoietic cells, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and reduced numbers of developing lymphocytes. The consistency between these two conditional knockout approaches indicates that the haematopoietic failure observed in Mx1Cre;MllF/F mutants was likely due to Mll loss and not the combined effect of Mll loss and IFN signaling. Therefore, we conclude that Mll plays an essential, non-redundant role during the establishment of adult steady-state haematopoiesis.

In this study, we found that the in vivo expansion of VavCre;MllF/F fetal haematopoietic cells proceeds normally. However, Mll-deficient fetal liver haematopoietic cells exhibit reduced colony-forming potential and competitive engraftment capability, revealing an inherent functional deficit in these cells. The fact that we find no haematopoietic-intrinsic defect in fetal liver cellularity or phenotype is consistent with the results of McMahon et al., who also reported defects in fetal haematopoiesis only in the context of their germline knockout of Mll and not their VavCre conditional knockout.(15) Therefore, the reduction in fetal liver cellularity observed using traditional germline knockouts may be due to cell-extrinsic contributions of Mll loss in non-haematopoietic tissues such as endothelial or other stromal support cells. Alternatively, the severity of germline mutants may be due to an early developmental role for Mll such as in the hemangioblast, which would be affected in germline but not VavCre Mll mutants. This VavCre transgene is not expressed in endothelial cells or hemangioblasts, making it a valuable tool to exclude contributions from these tissues.(29, 33) More detailed analyses using endothelial-specific and temporally regulated transgenes will be necessary to account for the differences between germline and VavCre mutants.

The differences between our results and those of McMahon et al. with respect to the role of Mll in steady-state adult haematopoiesis are most easily explained by differences in the severity of the knockout allele, not the method of deletion. Both mutant alleles are associated with loss-of-function Mll phenotypes, yet the MllΔN allele exhibits more severe defects in haematopoiesis. The molecular mechanism behind the severity of the MllΔN allele likely lies in the fact that it is not only retained outside of the nucleus but also lacks important functional motifs for targeting chromatin. Although the allele used in the McMahon et al. study is thought to produce no protein, given the technical challenges of detecting MLL by immunoblot in primary cell types, it is possible that this approach produces a low level of partially active protein that can access the nucleus.

An important observation from our VavCre;MllF/F animals that was obscured using the Mx1Cre inducible transgenic model is the selective reduction in developing and peripheral B cells. A nonspecific reduction in B cells persists up to 15 days after pI:pC injection using our experimental conditions (unpublished data), thus it is likely that the effect of Mll loss was obscured by the global B cell reduction in pI:pC injected animals. The selective reduction in B-lymphopoiesis observed in VavCre mutants recalls the clinical observation that MLL-rearranged acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) is predominantly precursor-B cell ALL and is rarely T cell ALL.(34, 35) In fact, among patients with MLL translocations, the T-ALL group has a much more favorable outcome than the B-ALL group.(36) Therefore, the selective and persistent reduction in B lymphocytes observed in VavCre;MllF/F mutants suggests that MLL controls unique and important pathways in developing B cells that may be deregulated by MLL fusion oncoproteins. Future studies in which Cre recombinase is expressed specifically in early lymphocyte populations, thus sparing all other Mll-dependent cell types in the bone marrow, will be essential for dissecting a potential B-lymphocyte specific function of MLL.

Our data have important implications for the development of strategies to target MLL associated leukemia. First, the results presented here further support our conclusion(16) that targeting oncogenic MLL fusion proteins through direct inhibition of the N-terminus, which is shared with endogenous wild-type MLL may have the undesirable effect of suppressing ongoing normal haematopoiesis. This is particularly problematic, because structure-function relationships in the N-terminus have been extensively interrogated, and molecules that directly target the N-terminus of MLL could be used against a wide variety of MLL fusions differing in C-terminal fusion partner. An ideal targeted therapeutic would act exclusively on the aberrant activity of the oncogenic fusion protein, yet this degree of selectivity is difficult to achieve. Thus the viability of an MLL N-terminal targeting molecule may depend on identifying a therapeutic index distinguishing the activities of MLL fusion proteins from that of endogenous MLL. Mll loss-of-function models will help define the pathways required for normal haematopoiesis relative to those deregulated by MLL fusion proteins, perhaps guiding alternative strategies for selectively targeting the actions of leukemogenic MLL fusion proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank our lab members, David Traver and Christopher Dant for insightful comments and suggestions, Drs. Roderick Bronson, Benjamin Lee and Glen Raffel for histolology advice, and Drs. Hanna Mikkola, Matthias Stadtfeld and Thomas Graf for VavCre mice and advice for breeding and analyzing this strain. We are grateful to Nancy Speck for advice and use of her microscopes. This work was supported by N.I.H. grant HL090036 to P.E. and NCRR COBRE grant P20RR016437 to William Green.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary information accompanies the paper on the Leukemia website (http://www.nature.com/leu)

References

- 1.Behm FG, Raimondi SC, Frestedt JL, Liu Q, Crist WM, Downing JR, et al. Rearrangement of the MLL gene confers a poor prognosis in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia, regardless of presenting age. Blood. 1996 Apr 1;87(7):2870–2877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liedtke M, Cleary ML. Therapeutic targeting of MLL. Blood. 2009 Jun 11;113(24):6061–6068. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-197061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milne TA, Briggs SD, Brock HW, Martin ME, Gibbs D, Allis CD, et al. MLL targets SET domain methyltransferase activity to Hox gene promoters. Mol Cell. 2002 Nov;10(5):1107–1117. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00741-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakamura T, Mori T, Tada S, Krajewski W, Rozovskaia T, Wassell R, et al. ALL-1 is a histone methyltransferase that assembles a supercomplex of proteins involved in transcriptional regulation. Mol Cell. 2002 Nov;10(5):1119–1128. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00740-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeleznik-Le NJ, Harden AM, Rowley JD. 11q23 translocations split the "AT-hook" cruciform DNA-binding region and the transcriptional repression domain from the activation domain of the mixed-lineage leukemia (MLL) gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 Oct 25;91(22):10610–10614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slany RK, Lavau C, Cleary ML. The oncogenic capacity of HRX-ENL requires the transcriptional transactivation activity of ENL and the DNA binding motifs of HRX. Mol Cell Biol. 1998 Jan;18(1):122–129. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayton PM, Chen EH, Cleary ML. Binding to nonmethylated CpG DNA is essential for target recognition, transactivation, and myeloid transformation by an MLL oncoprotein. Mol Cell Biol. 2004 Dec;24(23):10470–10478. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.23.10470-10478.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yokoyama A, Cleary ML. Menin critically links MLL proteins with LEDGF on cancer-associated target genes. Cancer Cell. 2008 Jul 8;14(1):36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bach C, Mueller D, Buhl S, Garcia-Cuellar MP, Slany RK. Alterations of the CxxC domain preclude oncogenic activation of mixed-lineage leukemia 2. Oncogene. 2009 Feb 12;28(6):815–823. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daser A, Rabbitts TH. Extending the repertoire of the mixed-lineage leukemia gene MLL in leukemogenesis. Genes Dev. 2004 May 1;18(9):965–974. doi: 10.1101/gad.1195504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu BD, Hess JL, Horning SE, Brown GA, Korsmeyer SJ. Altered Hox expression and segmental identity in Mll-mutant mice. Nature. 1995 Nov 30;378(6556):505–508. doi: 10.1038/378505a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayton P, Sneddon SF, Palmer DB, Rosewell IR, Owen MJ, Young B, et al. Truncation of the Mll gene in exon 5 by gene targeting leads to early preimplantation lethality of homozygous embryos. Genesis. 2001 Aug;30(4):201–212. doi: 10.1002/gene.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ernst P, Fisher JK, Avery W, Wade S, Foy D, Korsmeyer SJ. Definitive hematopoiesis requires the mixed-lineage leukemia gene. Dev Cell. 2004 Mar;6(3):437–443. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terranova R, Agherbi H, Boned A, Meresse S, Djabali M. Histone and DNA methylation defects at Hox genes in mice expressing a SET domain-truncated form of Mll. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 Apr 25;103(17):6629–6634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507425103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McMahon KA, Hiew SY, Hadjur S, Veiga-Fernandes H, Menzel U, Price AJ, et al. Mll has a critical role in fetal and adult hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell. 2007 Sep 13;1(3):338–345. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jude CD, Climer L, Xu D, Artinger E, Fisher JK, Ernst P. Unique and Independent Roles for MLL in Adult Hematopoietic Stem Cells and Progenitors. Cell Stem Cell. 2007 Sep;1(3):324–337. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yano T, Nakamura T, Blechman J, Sorio C, Dang CV, Geiger B, et al. Nuclear punctate distribution of ALL-1 is conferred by distinct elements at the N terminus of the protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997 Jul 8;94(14):7286–7291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuhn R, Schwenk F, Aguet M, Rajewsky K. Inducible gene targeting in mice. Science. 1995 Sep 8;269(5229):1427–1429. doi: 10.1126/science.7660125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jude CD, Gaudet JJ, Speck NA, Ernst P. Leukemia and hematopoietic stem cells: balancing proliferation and quiescence. Cell Cycle. 2008 Mar;7(5):586–591. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.5.5549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baron ML, Gauchat D, La Motte-Mohs R, Kettaf N, Abdallah A, Michiels T, et al. TLR Ligand-Induced Type I IFNs Affect Thymopoiesis. J Immunol. 2008 Jun 1;180(11):7134–7146. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Demoulins T, Abdallah A, Kettaf N, Baron ML, Gerarduzzi C, Gauchat D, et al. Reversible blockade of thymic output: an inherent part of TLR ligand-mediated immune response. J Immunol. 2008 Nov 15;181(10):6757–6769. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.6757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Despres D, Goldschmitt J, Aulitzky WE, Huber C, Peschel C. Differential effect of type I interferons on hematopoietic progenitor cells: failure of interferons to inhibit IL-3-stimulated normal and CML myeloid progenitors. Exp Hematol. 1995 Dec;23(14):1431–1438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mizutani T, Tsuji K, Ebihara Y, Taki S, Ohba Y, Taniguchi T, et al. Homeostatic erythropoiesis by the transcription factor IRF2 through attenuation of type I interferon signaling. Exp Hematol. 2008 Mar;36(3):255–264. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Essers MA, Offner S, Blanco-Bose WE, Waibler Z, Kalinke U, Duchosal MA, et al. IFNalpha activates dormant haematopoietic stem cells in vivo. Nature. 2009 Apr 16;458(7240):904–908. doi: 10.1038/nature07815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato T, Onai N, Yoshihara H, Arai F, Suda T, Ohteki T. Interferon regulatory factor-2 protects quiescent hematopoietic stem cells from type I interferon-dependent exhaustion. Nat Med. 2009 Jun;15(6):696–700. doi: 10.1038/nm.1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogilvy S, Metcalf D, Gibson L, Bath ML, Harris AW. Adams JM. Promoter elements of vav drive transgene expression in vivo throughout the hematopoietic compartment. Blood. 1999 Sep 15;94(6):1855–1863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Boer J, Williams A, Skavdis G, Harker N, Coles M, Tolaini M, et al. Transgenic mice with hematopoietic and lymphoid specific expression of Cre. Eur J Immunol. 2003 Feb;33(2):314–325. doi: 10.1002/immu.200310005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Georgiades P, Ogilvy S, Duval H, Licence DR, Charnock-Jones DS, Smith SK, et al. VavCre transgenic mice: a tool for mutagenesis in hematopoietic and endothelial lineages. Genesis. 2002 Dec;34(4):251–256. doi: 10.1002/gene.10161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stadtfeld M, Graf T. Assessing the role of hematopoietic plasticity for endothelial and hepatocyte development by non-invasive lineage tracing. Development. 2005 Jan;132(1):203–213. doi: 10.1242/dev.01558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yagi H, Deguchi K, Aono A, Tani Y, Kishimoto T, Komori T. Growth disturbance in fetal liver hematopoiesis of Mll-mutant mice. Blood. 1998 Jul 1;92(1):108–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim I, He S, Yilmaz OH, Kiel MJ, Morrison SJ. Enhanced purification of fetal liver hematopoietic stem cells using SLAM family receptors. Blood. 2006 Jul 15;108(2):737–744. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhandoola A, Sambandam A. From stem cell to T cell: one route or many? Nature Immunology. 2006;6(2):117–126. doi: 10.1038/nri1778. [review] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen MJ, Yokomizo T, Zeigler BM, Dzierzak E, Speck NA. Runx1 is required for the endothelial to haematopoietic cell transition but not thereafter. Nature. 2009 Feb 12;457(7231):887–891. doi: 10.1038/nature07619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abshire TC, Buchanan GR, Jackson JF, Shuster JJ, Brock B, Head D, et al. Morphologic, immunologic and cytogenetic studies in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia at diagnosis and relapse: a Pediatric Oncology Group study. Leukemia. 1992 May;6(5):357–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huret JL, Brizard A, Slater R, Charrin C, Bertheas MF, Guilhot F, et al. Cytogenetic heterogeneity in t(11;19) acute leukemia: clinical, hematological and cytogenetic analyses of 48 patients--updated published cases and 16 new observations. Leukemia. 1993 Feb;7(2):152–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pui CH, Chessells JM, Camitta B, Baruchel A, Biondi A, Boyett JM, et al. Clinical heterogeneity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia with 11q23 rearrangements. Leukemia. 2003 Apr;17(4):700–706. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.