Abstract

γδ T cells are important for the early control of West Nile virus (WNV) dissemination. Here, we investigated the role of γδ T cells in regulation of CD4+ T cell response following WNV challenge. Splenic dendritic cells (DCs) of WNV-infected γδ T cell-deficient (TCRδ−/−) mice displayed lower levels of CD40, CD80, CD86 and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II expression and interleukin-12 (IL-12) production than those of wild- type mice. Naïve DCs co-cultured with WNV-infectedγδ T cells had enhanced levels of co- stimulatory molecules, MHC class II expression and IL-12 production. Further, co-culture of CD4+ T cells from OT II transgenic mice with DCs of WNV-infected TCRδ−/− mice induced less interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and IL-2 production than with those of wild-type controls. Viral antigens were detected in WNV-infected γδ T cells. WNV infection or toll-like receptor (TLR) agonist treatment of γδ T cells induced the production of IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and IL-6, which were known to promote DC maturation. Nevertheless, levels of TLRs 2, 3, 4 and 7 expression of WNV-infected γδ T cells were not different from those of non-infected cells. Overall, these data suggest that WNV-inducedγδ T cell activation promotes DC maturation and initiates CD4+ T cell priming.

Keywords: West Nile virus, Dendritic cell, γδ T cell

Introduction

West Nile virus (WNV), a mosquito-borne neurotropic flavivirus, has caused annual outbreaks of viral encephalitis in North America for nearly a decade (Campbell, et al., 2002, Pletnev, et al., 2006). Although most WNV infections in humans are asymptomatic, severe neurological disease (including encephalitis) and death have been observed with a higher frequency in the elderly and immunocompromised (Campbell, et al., 2002, Pletnev, et al., 2006). Human vaccines are not available yet.

The murine model has been used as an effective tool to investigate host immunity to WNV infection in humans. Type I interferon (IFN) and γδ T cells provide immediate control of virus dissemination (Anderson & Rahal, 2002, Wang, et al., 2003, Samuel & Diamond, 2005). B cells and specific antibodies are critical in the control of disseminated WNV infection, but are not sufficient to eliminate it from the host (Roehrig, et al., 2001, Diamond, et al., 2003). αβ T cells (Diamond, et al., 2003) provide long-lasting protective immunity and contribute to host survival following WNV infection. CD4+ T cells provide help for antibody responses and sustain WNV-specific CD8+ T cell responses in the central nervous system (CNS) (Sitati & Diamond, 2006), whereas CD8+ effector T cells are important in clearing WNV infection from tissues and preventing viral persistence (Wang, et al., 2003, Shrestha & Diamond, 2004). The development of memory T cells following WNV infection remains poorly understood.

Dendritic cells (DCs) represent the most important antigen presenting cells exhibiting the unique capacity to initiate primary T cell responses. Upon microbial infection, DC maturation is an innate response that leads to adaptive immunity to foreign antigens (De Smedt, et al., 1996, Bennett, et al., 1998). Maturation of DCs results in the expression of high levels of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and co-stimulatory molecules such as CD40, CD80 and CD86 and is often associated with the secretion of interleukin-12 (IL-12) (Inaba, et al., 2000, Fujii, et al., 2004). Proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and IFN-γ, promote this process (Dieli, et al., 2004, Conti, et al., 2005). Furthermore, increasing evidence suggests that the cross talk betweenγδ T cells and DCs contributes to DC maturation (Leslie, et al., 2002, Collins, et al., 2005, Munz, et al., 2005). Nevertheless, the in vivo mechanisms underlying this process are not clearly identified.

We have recently shown that γδ T cells expanded quickly in response to WNV infection and produced significant amount of IFN-γ (Wang, et al., 2003). γδ T cell-deficient (TCRδ−/−) mice had a reduced CD8+ T cell memory response and were more susceptible to secondary WNV infection, suggesting a role of γδ T cells in linkage of innate immunity to adaptive immune responses (Wang, et al., 2006). In this study, we investigate the role of γδ T cells in regulating DC maturation and initiating CD4+ T cell priming following WNV challenge.

Materials and Methods

Mice

6-10-week-old C57BL/6 (B6) mice and OT II transgenic mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory Bar Harbor, ME). TCRδ−/− mice were a kind gift from Dr. E. ( Fikrig (Yale University, New Haven). Groups were age and sex-matched for each experiment and were housed under identical conditions. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Colorado State University.

Infection in mice

WNV NY99-6480 was passaged three times in C6/36 Aedes albopictus cells to make a virus stock for both cell culture and in vivo studies. Mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 100 PFU of WNV NY99-6480 isolate.

Purification of DCs, CD4+, and γδ T cell subsets

DCs, CD4+ and γδ T cells were purified from pooled spleens of 3–5 mice by a positive selection method, using anti-CD11c, anti-mPDCA-1, anti-CD4 magnetic beads or FITC-conjugated anti-mouse TCRγδ BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) followed by anti-FITC magnetic beads according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). The purity of these cells is 82–95%. For FACS purification of γδ T cells, splenocytes were enriched for Tcells using anti-CD90 magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec), stained with FITC labeled anti-TCRγδ and sorted based on expression of TCRγδ (MoFlo, DakoCytomation). The purity of γδ T cells was 94.3%.

Flow cytometry

Antibodies for CD40, CD80, CD86, I-Ab and CD11c were purchased from BD Biosciences. Following staining, cells were fixed in PBS with 1% paraformaldehyde and examined using a Cyan flow cytometer (Dako Cytomation). Data were analyzed using Summit 4 software (Dako Cytomation). For intracellular cytokine staining, splenocytes were stimulated at 2 × 106 cells/well with 10μg/ml LPS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or 0.5 μg/ml CL097 (Invivogen, San Diego, CA) with Golgi-Plug for 4 h at 37°C. Cells were harvested, stained with FITC-anti-CD11c, fixed in Fixation/Permeabilization solution before adding PE- anti-IL-12 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) or rat IgG2a (BD Biosciences).

In vitro DC maturation and T cell priming assays

Naïve DCs were co-cultured with γδ T cells from non-infected or WNV-infected mice at 1: 1 ratio in 24-well plates at 37 °C for 24 h. Cells were harvested and stained with antibodies for cell surface markers. CD11c+ cells were gated for analysis. DCs were also co-cultured with in vitro WNV-infected γδ T cells. CD4+ T Cells and DCs were purified from splenocytes of OT II transgenic mice or WNV-infected mice at day 3 post-infection. CD4+ T Cells (1 × 105) were mixed with DCs at 1:1 ratio and treated with or without OVA residue 323–339 (10μg/ml, Genscript Corporation, Piscataway, NJ).

WNV infection or stimulation with TLR agonist in γδ T cells

γδ T cells (1 × 105 cells/well) were cultured for 2 days at 37 °C in RPMI-1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in 96-well plates coated with 5μg/ml anti-CD3 (eBioscience). Cells were infected with WNV at a MOI of 0.5 for 1 h, washed and incubated in the above medium containing 5 ng/ml recombinant human IL-2 (eBioscience). H36.12j cells (macrophage cell line, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were infected with WNV (MOI = 1) and harvested at day 4 post-infection. In some experiments, γδ T cells were stimulated with poly I: C (Amersham Pharmacia, New Jersey, 50μg/ml) or CL097 (Invivogen, 0.5μg/ml).

Quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) and PCR for determining viral load and TLR levels

RNA was extracted using RNAeasy extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and was used to synthesize complementary (c)DNA using the ProSTAR First-strand RT-PCR kit (Stratagene, Cedar Creek, TX). The sequences of the primersets for WNV envelope gene (WNE), Tlr2, Tlr3, Tlr4 and Tlr7 cDNA and PCR conditions were described previously (Lanciotti, et al., 2000, Schulz, et al., 2005, Chen, et al., 2006). Q-PCR analysis was performed with RT2 Real-Time SYBR Green / Fluorescein PCR master mix (Superarray, Frederick, MD) on an iCycler (Bio- Rad, Hercules, CA). The ratioof the amount of amplified gene compared with the amount of β-actin cDNA represented the relative levels in each sample. Regular PCR was performed as follows: 94°C for 2 min followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1.5 min, and final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The primer pairs used were: TLR2, 5’-CAG ACG TAG TGA GCG AGC TG-3’ and 5’-GGC ATC GGA TGA AAA GTG TT-3’; TLR3, 5’-CCC CCT TTG AAC TCC TCT TC-3’ and 5’-TTT CGG CTT CTT TTG ATG CT -3’; TLR4, 5’-GCT TTC ACC TCT GCC TTC AC-3’ and 5’-CGA GGC TTT TCC ATC CAA TA-3’; TLR7, 5’-CAT CAG AGG CTC CTG GAT GA-3’ and 5’-AGG CAT GTC CTA GGT GGT GA-3’. The sequences of the primersets for β-actin were described earlier (Farrar & Street, 1995).

Fluorescence microscopy with γδ T-cells

Cells were fixed in acetone at −20°C for 30 min, rehydrated in PBS and stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD3, Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-TCRβ (eBioscience) and the flavivirus E protein-specific monoclonal antibody 4G2 followed by Alexa Fluor 350-conjugated anti-mouse IgG2a (Invitrogen) at 37°C. Images were acquired on an Olympus IX71 Inverted Microscope at 20 × magnification.

Plaque assay

Vero cells were seeded in DMEM (Invitrogen) with 10% FBS and incubated with serial dilutions of culture supernatant for 2 h. DMEM containing 5% FBS and 1% low-melting-point agarose was added and incubated for 4 days. A second overlay of 1% agarose-medium containing 0.01% neutral red was added to visualize plaques.

Cytometric bead array and ELISA

Culture supernatant was measured for cytokine production using a mouse Th1/Th2 kit or an inflammation kit by a FACSArray analyzer (BD Biosciences). Cytokine levels were also measured by ELISAs (BD Biosciences & PBL Interferon Source).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using Prism software (Graph-Pad) statistical analysis. Values for phenotype analysis, viral burden, and cytokine production experiments were presented as means ± SEM. P values of these experiments were calculated with a non-paired Student’st test or Mann-Whitney test. Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

Results

DC activation and maturation was reduced in TCRδ−/− mice during WNV infection

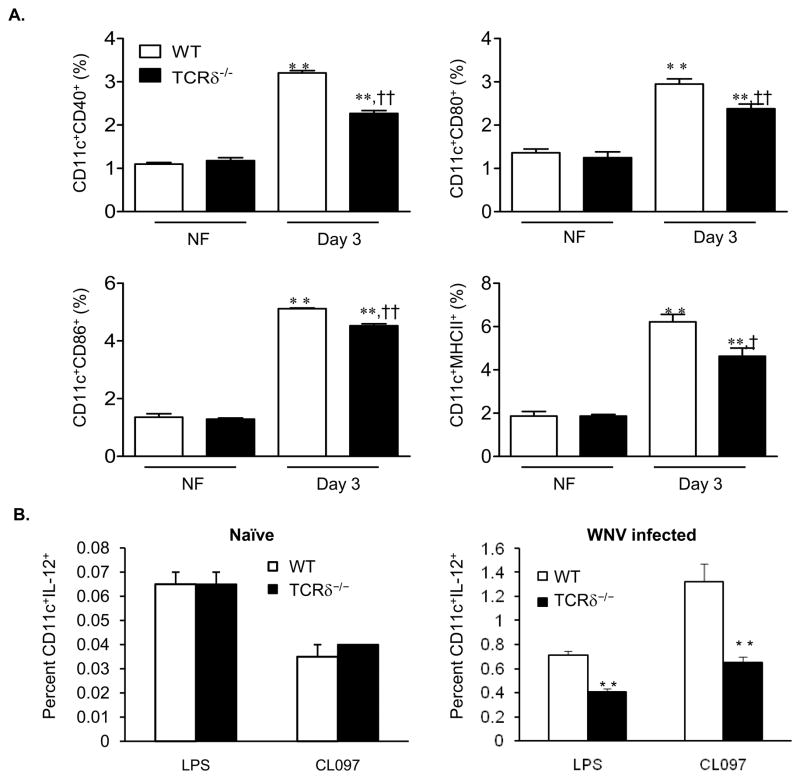

Our previous results have shown that TCRδ−/− mice were much more susceptible to a LD50 dose of WNV infection than wild-type controls (Wang, et al., 2003). Further, TCRδ−/− mice that survived a LD50 dose of WNV challenge were more susceptible to the secondary infection than wild-type mice (Wang, et al., 2006). To investigate the role of γδ T cells in regulating CD4+ T cell response, we assessed splenic DCs phenotype and functionality in wild-type and TCRδ−/− mice following infection with a LD50 dose of WNV. At day 3 post-infection, the expression of CD40, CD80, CD86, and MHC class II on CD11c+ splenocytes of wild-type mice was increased by percentage and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) (P < 0.05 or 0.01, Fig. 1A, Table 1 and Suppl. Fig. 1). In WNV-infected TCRδ−/− mice, percentage of CD80+CD11c+, CD86+CD11c+ splenocytes or MFI on these cells were also increased (P < 0.05 or 0.01); while CD40 and MHC class II expression were only elevated by percentage (P < 0.01, Fig. 1A, Table 1 & Suppl. Fig. 1). Interestingly, in comparison to wild-type mice, expression of all these surface molecules was significantly lower in CD11c+ splenocytes of WNV-infected TCRδ−/− mice by percentage (12–28%, Fig. 1A) or by MFI (16–32% except for CD80, Table 1 & Suppl. Fig. 1, P < 0.05 or 0.01). Similar results were observed at day 5 post-infection, though the magnitude of increase of these surface molecules expression was reduced in both groups of mice by 5–40% as compared to day 3 (data not shown). There were no differences in the expression of the above surface molecules in CD11c+ cells between naïve wild-type and TCRδ−/− mice (Fig. 1A & Table 1 and Suppl. Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

DC maturation in WNV-infected mice. A, The percentages of CD40+ CD11c+, CD80+CD11c+, CD86+CD11c+ or MHCII+CD11c+ in the spleens. Data are presented as means ± SEM, n = 4 or 5. ** P < 0.01 for WNV-infected (IF) vs. non-infected (NF). † P < 0.05 or †† P < 0.01 for wild-type (WT) vs. TCRδ−/− mice. B, The percentages of IL-12+ CD11c+ naïve (left panel) or day 2 WNV-infected (right panel) splenocytes after ex vivo stimulation with LPS or CL097. Data are presented as means ± SEM, n = 4 or 5. ** P < 0.01 for wild-type vs. TCRδ−/− mice. P values were calculated with a non-paired Student’st test.

Table 1.

Mean fluorescence intensity of CD40, CD80, CD86 and MHC class II expression on DCs from wild-type and TCRδ−/−mice following WNV infection:

| Cell surface marker |

Wild-type NF |

Wild-type IF |

TCRδ−/ − NF |

TCRδ−/− IF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD40 | 40.2 ± 3.1 | 65.2 ± 3.2* | 42.1 ± 1.6 | 44.6 ± 4.0†† |

| CD80 | 43.0 ± 2.2 | 56.0 ± 3.6* | 38.0 ± 2.5 | 52.9 ± 1.8* |

| CD86 | 41.3 ± 5.9 | 85.5 ± 1.1** | 39.7 ± 5.4 | 70.7 ± 0.6**, †† |

| MHC class II | 332.0 ± 53 | 517.0 ±12.2** | 338.7 ± 55 | 434.0 ± 12.3†† |

Values are means ± SEM, n = 4.

P < 0.05 or

P < 0.01 for WNV-infected (IF) vs. non-infected (NF).

P < 0.01 for wild-type vs. TCRδ−/− mice. Data shown were representative of two independent experiments.

P values were calculated with a non-paired Student’st test.

Proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-12, are important for DC maturation (Sallusto & Lanzavecchia, 1994, Inaba, et al., 2000, Le Bon, et al., 2001). We next measured cytokine production in CD11c+ DCs from wild-type and TCRδ−/− mice using ex vivo intracellular cytokine staining. There were no differences in the percentage of IL-12-producing DCs between naive wild-type and TCRδ−/− mice upon stimulation with the TLR4 agonist LPS or the TLR7 agonist CL097 (Fig. 1B left panel). However, the percentage of IL-12-producing DCs in WNV-infected TCRδ−/− mice stimulated with LPS or CL097 were 54% or 26% lower than those of WNV-infected wild-type mice (P < 0.01, Fig. 1B right panel). There were no significant differences in TNF-α and IFN-γ production in CD11c+ DCs between these two groups (data not shown). Overall, these data suggest that γδ T cells are involved in the process of DC maturation during WNV infection.

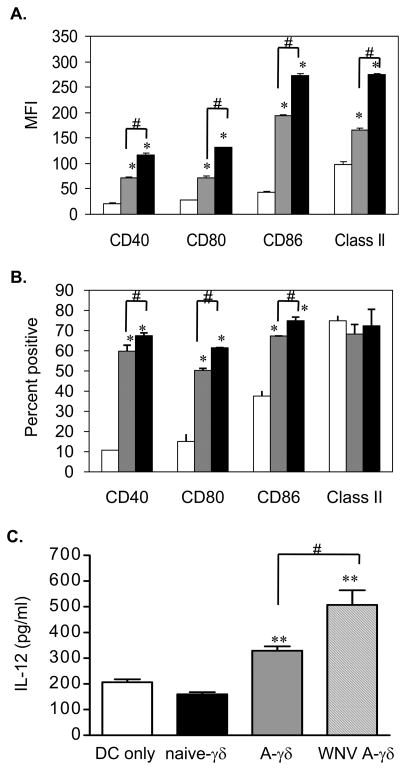

DCs exposed to WNV-infected γδ T cells acquire the functional and phenotypic characteristics of mature cells

To verify that γδ T cells are involved in DC activation during WNV infection, we performed ex vivo DC maturation assays. In this assay, CD11c+ DCs were purified from naïve B6 mice and co-cultured with γδ T cells from non-infected or day 2 post-infected mice. After 24 h co-culture, cells were harvested and gated on CD11c+ population for phenotypic analysis. Interestingly, CD40, CD80, CD86 and MHC class II expression on CD11c+ cells were enhanced after co-culture with naive γδ T cells by MFI and/or percentage (Figs. 2A & 2B, P < 0.05). Further, DCs co-cultured with γδ T cells from WNV-infected mice had a higher level of expression of these cell surface molecules than those co-cultured with naïve γδ T cells or DC alone (Figs. 2A & 2B, P < 0.05). We also co-cultured immature DCs with in vitro WNV-treated γδ T cells. At 24 h, IL-12 levels in co-culture of DCs with WNV-treated and anti-CD3 stimulated γδ T cells were about 150% higher than those of DCs alone (Fig. 2C, P < 0.05). DCs co-cultured with non-infected and anti-CD3-stimulated γδ T cells also induced higher levels of IL-12 (about 60%) than DCs alone (Fig. 2C, P < 0.05). γδ T cells, naive or activated by anti- CD3-stimulation and/ or WNV infection, did not produce IL-12 (data not shown).

Figure 2.

In vitro DC maturation assay. Cell surface molecule expression of CD11c+ cells alone (white bar) or co-culture with γδ T cells of naïve (grey bar) or WNV-infected (black bar) mice as determined by MFI (A) and the percentage (B). C, IL-12 production from co-culture of naïve DCs with in vitro WNV infected γδ T cells measured by ELISA. A-γδ: anti-CD3 activated γδ T cells. WNV A-γδ: anti-CD3 treated γδ T cells infected with WNV. Data are presented as means ± SEM, n = 6. *P < 0.05 or ** P < 0.01 for co-cultured vs. DC alone. #P < 0.05 for IF vs. NF. P values were calculated with a non-paired Student’st test. Results are representative of two independent experiments.

DCs from WNV-infected TCRδ−/− mice could not prime CD4+ T cells as efficiently as those of wild-type mice

To further understand the role of γδ T cells in regulating CD4+ T cell response during WNV infection, we tested the capability of DCs from WNV-infected mice to activate naïve CD4+ T cells in vitro. Purified naïve CD4+ T cells from OT II transgenic mice were co-cultured with DCs from WNV-infected wild-type or TCRδ−/− mice in the presence of OVA 323–339. At 24 h post co-culture, OT II CD4+ T cells co-cultured with DCs from wild-type mice produced about 46% more IFN-γ (P < 0.01) or 15% IL-2 (P < 0.05) respectively than those cocultured with DCs of TCRδ−/− mice (Table 2). At 72 h, IFN-γ but not IL-2 production remained higher in co-culture with wild-type DCs than TCRδ−/− DCs (data not shown). These data suggests that the antigen-presenting capacity of DCs might be reduced or impaired in the absence of γδ T cells.

Table 2.

In vitro T cell priming assay:

| Group |

IFN-γ(pg/ml) |

IL-2 (pg/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| Wild-type DCs + T cells | 48.0 ± 4.8 | 33.7 ± 5.7 |

| TCRδ−/− DCs + T cells | 43.3 ± 3.2 | 33.3 ± 5.8 |

| CD4+ T cells + OVA | 33.3 ± 8.4 | 33.3 ± 2.6 |

| Wild-type DCs + OVA + CD4+ T cells | 31,242 ± 1623 | 18,953 ± 759 |

| TCRδ−/− DCs + OVA + CD4+ T cells | 21,640 ± 835** | 16,543 ± 392* |

Purified naïve CD4+ T cells from OT II transgenic mice were co-cultured with DCs from WNV-infected wild-type or TCRδ−/ − mice in the presence or absence of OVA 323–339. At 24 h post coculture, supernatant was harvested and measured for cytokine production using mouse Th1/Th2 cytokine kit. Data are presented as means ± SEM, n = 3.

P < 0.05 or

P < 0.01 for wild-type vs. TCRδ−/ −.

P values were calculated with a non-paired Student’st test. Data shown were representative of two independent experiments.

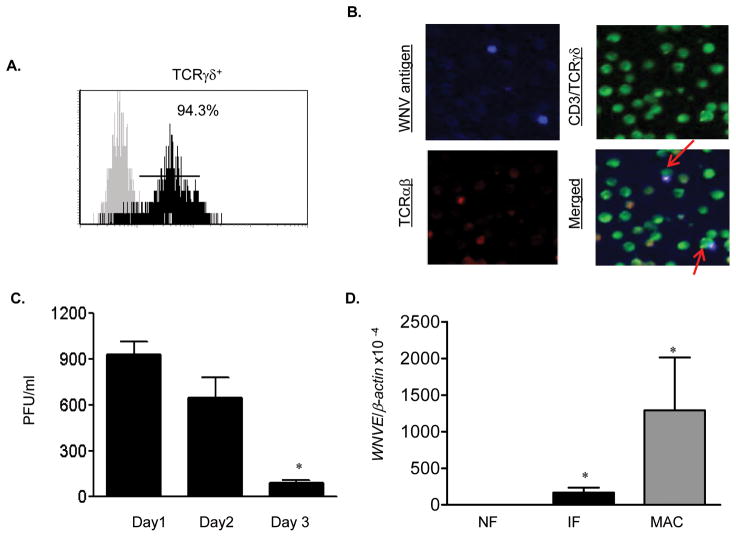

WNV antigens were detected in the infected γδ T cells

We have recently demonstrated that splenic T cells are permissive to WNV infection and support a short-term virus replication (Wang, et al., 2008). Here, we asked whether γδ T cells could be infected by WNV. Splenic γδ T cells were purified and stimulated in vitro with anti-CD3 for 2 days before WNV infection. The purity of γδ T cells was close to 94% as analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. 3A). Immunofluorescence staining demonstrated CD3+/TCRγδ+/WNV+ populations in these cells at day 2 post-infection (Fig. 3B). Plaque assay showed WNV replicated productively in purified γδ T cells at days 1 and 2 post-infection, but decreased at day 3 (P < 0.05, Fig. 3C). Further, Q-PCR analysis of day 4 post-infectedγδ T cells revealed a low but significant level of virus infection as compared to WNV-infected H36.12j cells (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

In vitro WNV infection of γδ T cells. A, Splenic γδ T cells were stained with antibody to γδ and analyzed by flow cytometer. Dark area represents cells stained with anti-γδ; gray area, unstained cells. B, Immunofluorescence photomicrographs of WNV-infected γδ T cells at day 2 post-infection. Infected cells were stained for WNV antigen (blue), CD3/TCRγδ (green) and TCRαβ (red). Arrows point to CD3+/γδ+WNV+ cells. C, Plaque assay of virus titer. *P < 0.05 for day 3 vs. day 1. D, WNV infection in splenic γδ T cells as measured by Q-PCR. Negative and positive controls represent uninfected γδ T cells and WNV-infected H36.12j cells (MAC), respectively. *P < 0.05 for non-infected vs. WNV-infected cells. P values were calculated with a non-paired Student’st test.

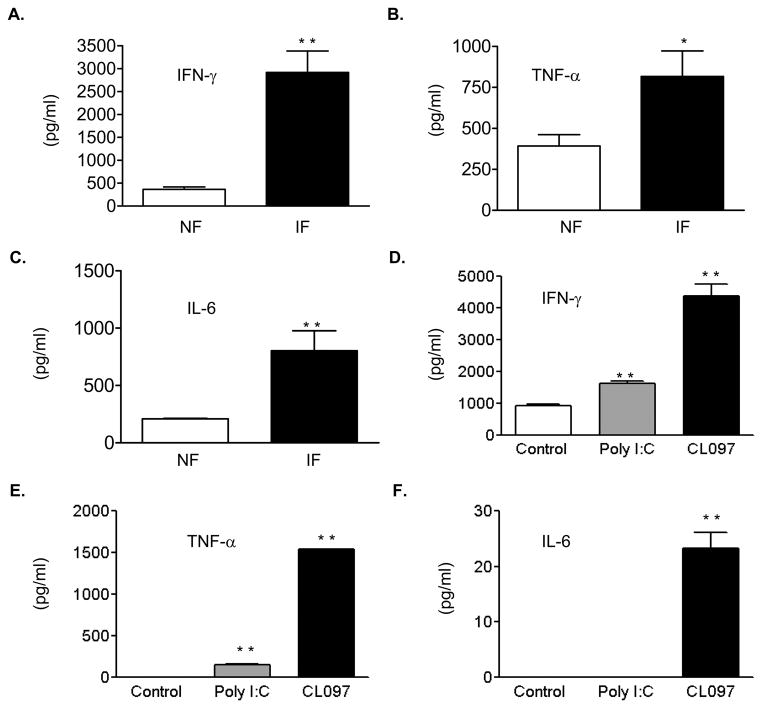

WNV infection or TLR agonist stimulation of γδ T cells induces proinflammatory cytokine production. However, the expression of TLRs on γδ T cells was not changed after infection

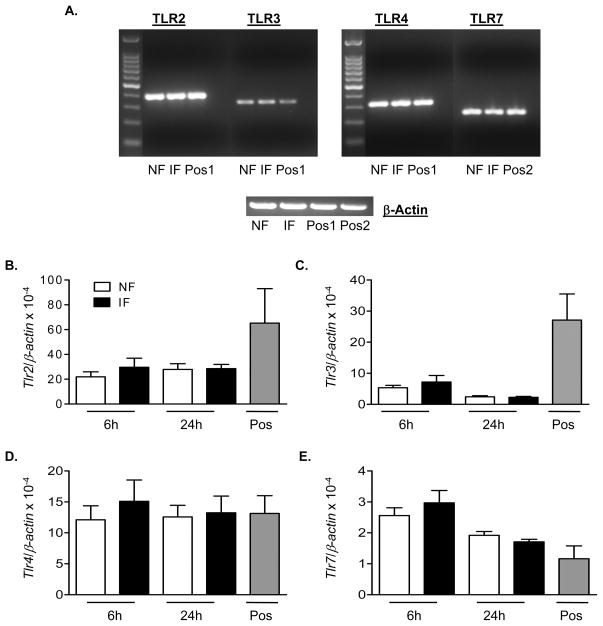

The production of proinflammatory cytokines, including IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-6 from γδ T cells was increased as early as day 2 post-infection (data not shown) and became more dramatically enhanced at day 4 post-infection (Fig. 4A–C, P < 0.05 or 0.01). The TLR family plays a fundamental role in host innate immunity by mounting a rapid and potent inflammatory response to pathogen infection via recognition of conserved structural patterns in diverse microbial molecules. The expression of TLR2, TLR3, TLR4 and TLR7/8 on γδ T cells has been reported (Shimura, et al., 2005, Beetz, et al., 2007, Peng, et al., 2007, Beetz, et al., 2008). Among them, TLR3 and TLR7-induced Type I IFNs and proinflammatory cytokine production are known to play important roles in host immunity following WNV infection (Wang, et al., 2004, Daffis, et al., 2008, Town, et al., 2009). Here, we found γδ T cells stimulated with TLR agonists such as CL097 (TLR7) or poly I: C (TLR3) also produced significant amount of IFN-γ, TNF-α, and/or IL-6 (Figs. 4D–F, P < 0.01). Nevertheless, there were no significant differences in the levels of TLR2, TLR3, TLR4 and TLR7 expression between WNV-infected γδ T cells and non-infected controls at 6 h (Figs. 5B–5E) or 24 h (Figs. 5A–5E) post-infection.

Figure 4.

WNV infection or TLR agonist stimulation of γδ T cells induces proinflammatory cytokines. A–C, Supernatant was collected at day 4 post-infection. D–F, Supernatant was collected 24 h post-treatment. Data are presented as means ± SEM, n = 6. * P < 0.05 or ** P < 0.01 for non-infected or non-treated vs. WNV-infected or treated. P values were calculated with a non-paired Student’st test.

Figure 5.

Levels of TLR expression on WNV-infectedγδ T cells. Splenic γδ T cells were infected with WNV and harvested at indicated time points. A, PCR amplification of TLRs (top panel) or β-actin (bottom panel) of WNV-infected or non-infected γδ T cells harvested at 24 h post-infection. B–E, Q-PCR analysis of TLRs. B, TLR2. C, TLR3. D, TLR4. E, TLR7. cDNA of CD11c+ cells or plasmacytoid DCs were used as positive control 1 & 2. Data are presented as means ± SEM, n = 7 or 8. P values were calculated with a Mann-Whitney test.

Discussion

Although several important immune factors have been recognized to be critical for immediate control of WNV dissemination, the development of long-lasting protective immunity against WNV is not well understood. In the present study, we investigated the role of γδ T cells in regulating DC maturation and CD4+ T cell priming following WNV challenge. We found that DC activation and maturation was reduced in TCRδ−/− mice during WNV infection. Immature DCs co-cultured with γδ T cells of WNV-infected mice or in vitro infection had enhanced levels of co-stimulatory molecule expression and IL-12 production. Co-culture of CD4+ T cells of OT II mice with DCs of WNV-infected wild-type mice induced more IFN-γ and IL-2 production than with DCs of TCRδ−/− mice. Moreover, WNV infection of γδ T cells induces proinflammatory cytokine production without changes on TLR expression levels. Collectively, our data suggest that γδ T cells are involved in DC maturation and CD4+ T cell priming following WNV challenge.

Increasing evidence suggests that both the crosstalk between γδ T cells and DCs and proinflammatory cytokines contribute to DC maturation (Ismaili, et al., 2002, Leslie, et al., 2002, Collins, et al., 2005, Munz, et al., 2005, Conti, et al., 2005). Here, we have observed that naïve DCs co-cultured with non-infectedγδ T cells have enhanced levels of co-stimulatory molecules and MHC class II expression. This suggests that crosstalk between γδ T cell and DC is necessary for DC maturation. WNV-infected γδ T cells produce proinflammatory cytokines, including IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-6. Upregulation of co-stimulatory molecules and MHC class II expression was significantly higher on DCs that were co-cultured with WNV-infectedγδ T cells than with naïve γδ T cells. These data further demonstrates that the secreting factors from WNV-infected γδ T cells are also important for promoting DC maturation.

Current understanding of the biological role of γδ T cell receptors during pathogen infection remains elusive. Unlike αβ T cells, there are few antigens that are recognized by γδ T cell receptor (Born & O'Brien, 2009). Although γδ T cells support a short-term WNV replication and are activated after infection, it is not clear whether any viral antigen is recognized by T cell receptor. TLR3 and TLR7-induced Type I IFNs and proinflammatory cytokine production play important roles in host immunity, following WNV infection (Wang, et al., 2004, Daffis, et al., 2008, Town, et al., 2009). It is likely that γδ T cells are induced by WNV infection via the innate immune receptors, such as TLRs (Peng, et al., 2007, Beetz, et al., 2008). This is further supported by the fact that both WNV infection and TLR agonist stimulation induce γδ T cells to produce IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-6 cytokines. Expression of TLRs on γδ T cells has been shown to be upregulated after microbial infection or burn injury followed by activation (Mokuno, et al., 2000, Shibata, et al., 2007, Schwacha & Daniel, 2008). Nevertheless, we noted no differences in the levels of expression of TLRs after WNV infection. While the direct role of TLRs in γδ T cell activation upon WNV infection is still under investigation, it is also possible that WNV infection of γδ T cells induces the non-TLR innate immune receptors, such as RIG-I and MDA5, which have been reported to be involved in WNV recognition (Fredericksen & Gale, 2006, Fredericksen, et al., 2008). Alternatively, γδ T cells and DCs are also known to exert regulatory influences on each other. For example, induction of human γδ T cells by poly I:C, a ligand for TLR3, depends on DCs mediated by Type-I IFNs (Kunzmann, et al., 2004). Thus, TLR signaling might be involved in γδ T cell activation indirectly through induction of WNV permissive DCs in a three-way process.

The role of T cells in protecting the host against WNV infection has been the subject of recent investigations. CD4+ T cells are known to provide help for antibody responses and to sustain WNV-specific CD8+ T cell responses in the CNS, enabling viral clearance (Sitati & Diamond, 2006). CD8+ T cells have important functions in clearing infection from peripheral tissues and CNS, and in preventing viral persistence (Shrestha & Diamond, 2004, Brien, et al., 2007). Therefore, enhancement of memory T cell response is an important strategy for future flavivirus vaccine development. Although human and mouse γδ T cells differ in the subsets and ligand recognition, they share substantial similarity in effector function and the protective role in pathogen infection (Girardi, 2006). The exploration of parallel activities mediated by murine γδ T cells will continue to provide insights into immunosurveillance and immune regulation in human diseases. γδ T cells are also known to display numerical and functional alteration in the elderly (Cardillo, et al., 1993, Argentati, et al., 2002), which are the potentially susceptible population for WNV encephalitis. Information gained from this study will possibly enhance our understanding of host immunity against WNV, and provide critical insights for new strategies for future flavivirus vaccine development.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Upregulation of cell surface molecules on CD11c+ splenocytes after WNV infection. A. CD11c+ cells were gated for analysis of the percentage of CD40+, CD80+, CD86+ and MHC class II+. Data are presented as means ± SEM, n = 4 or 5. ** P < 0.01 for WNV-infected (IF) vs. non-infected (NF). † P < 0.05 or †† P < 0.01 for wild-type (WT) vs. TCRδ−/− mice. P values were calculated with a non-paired Student’st test. B, Surface expression of CD40, CD80, CD86 and MHC class II in splenic CD11c+ cells of non-infected and WNV-infected mice. Results are representative of three experiments.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Anne Avery for helpful discussions and Diego Vargas-Inchaustegui, Sara Woodson, Yingwei Wang, Terry Juelich and Alexander Freiberg for kind help in setting up the in vitro cell culture for WNV infection and fluorescence microscopy studies. This work was supported by grants from NIH/NIAID Western Regional Center of Excellence award U54 AI-057156 (to M.R.H), R01AI043003 (to L.S.), and R01AI072060 (to T.W.).

References

- Anderson JF, Rahal JJ. Efficacy of interferon alpha-2b and ribavirin against West Nile virus in vitro. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:107–108. doi: 10.3201/eid0801.010252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argentati K, Re F, Donnini A, et al. Numerical and functional alterations of circulating gammadelta T lymphocytes in aged people and centenarians. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72:65–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beetz S, Marischen L, Kabelitz D, Wesch D. Human gamma delta T cells: candidates for the development of immunotherapeutic strategies. Immunol Res. 2007;37:97–111. doi: 10.1007/BF02685893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beetz S, Wesch D, Marischen L, Welte S, Oberg HH, Kabelitz D. Innate immune functions of human gammadelta T cells. Immunobiology. 2008;213:173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett SR, Carbone FR, Karamalis F, Flavell RA, Miller JF, Heath WR. Help for cytotoxic-T-cell responses is mediated by CD40 signalling. Nature. 1998;393:478–480. doi: 10.1038/30996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Born WK, O'Brien RL. Antigen-restricted gammadelta T-cell receptors? Arch Immunol Ther Exp. 2009;57:129–135. doi: 10.1007/s00005-009-0017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brien JD, Uhrlaub JL, Nikolich-Zugich J. Protective capacity and epitope specificity of CD8(+) T cells responding to lethal West Nile virus infection. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1855–1863. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell GL, Marfin AA, Lanciotti RS, Gubler DJ. West Nile virus. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:519–529. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardillo F, Falcao RP, Rossi MA, Mengel J. An age-related gamma delta T cell suppressor activity correlates with the outcome of autoimmunity in experimental Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2597–2605. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830231033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Wang YH, Wang Y, Huang L, Sandoval H, Liu YJ, Wang J. Dendritic cell apoptosis in the maintenance of immune tolerance. Science. 2006;311:1160–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.1122545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins C, Wolfe J, Roessner K, Shi C, Sigal LH, Budd RC. Lyme arthritis synovial gammadelta T cells instruct dendritic cells via fas ligand. J Immunol. 2005;175:5656–5665. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.5656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti L, Casetti R, Cardone M, et al. Reciprocal activating interaction between dendritic cells and pamidronate-stimulated gammadelta T cells: role of CD86 and inflammatory cytokines. J Immunol. 2005;174:252–260. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daffis S, Samuel MA, Suthar MS, Gale M, Jr, Diamond MS. Toll-like receptor 3 has a protective role against West Nile virus infection. J Virol. 2008;82:10349–10358. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00935-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smedt T, Pajak B, Muraille E, et al. Regulation of dendritic cell numbers and maturation by lipopolysaccharide in vivo. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1413–1424. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond MS, Shrestha B, Mehlhop E, Sitati E, Engle M. Innate and adaptive immune responses determine protection against disseminated infection by West Nile encephalitis virus. Viral Immunol. 2003;16:259–278. doi: 10.1089/088282403322396082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond MS, Sitati EM, Friend LD, Higgs S, Shrestha B, Engle M. A critical role for induced IgM in the protection against West Nile virus infection. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1853–1862. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieli F, Caccamo N, Meraviglia S, et al. Reciprocal stimulation of gammadelta T cells and dendritic cells during the anti-mycobacterial immune response. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:3227–3235. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrar JD, Street NE. A synthetic standard DNA construct for use in quantification of murine cytokine mRNA molecules. Mol Immunol. 1995;32:991–1000. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(95)00061-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredericksen BL, Gale M., Jr West Nile virus evades activation of interferon regulatory factor 3 through RIG-I-dependent and -independent pathways without antagonizing host defense signaling. J Virol. 2006;80:2913–2923. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.6.2913-2923.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredericksen BL, Keller BC, Fornek J, Katze MG, Gale M., Jr Establishment and maintenance of the innate antiviral response to West Nile Virus involves both RIG-I and MDA5 signaling through IPS-1. J Virol. 2008;82:609–616. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01305-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii S, Liu K, Smith C, Bonito AJ, Steinman RM. The linkage of innate to adaptive immunity via maturing dendritic cells in vivo requires CD40 ligation in addition to antigen presentation and CD80/86 costimulation. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1607–1618. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardi M. Immunosurveillance and immunoregulation by gammadelta T cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:25–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba K, Turley S, Iyoda T, et al. The formation of immunogenic major histocompatibility complex class II-peptide ligands in lysosomal compartments of dendritic cells is regulated by inflammatory stimuli. J Exp Med. 2000;191:927–936. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.6.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismaili J, Olislagers V, Poupot R, Fournie JJ, Goldman M. Human gamma delta T cells induce dendritic cell maturation. Clin Immunol. 2002;103:296–302. doi: 10.1006/clim.2002.5218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzmann V, Kretzschmar E, Herrmann T, Wilhelm M. Polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid-mediated stimulation of human gammadelta T cells via CD11c dendritic cell-derived type I interferons. Immunology. 2004;112:369–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01908.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanciotti RS, Kerst AJ, Nasci RS, et al. Rapid detection of West Nile virus from human clinical specimens, field- collected mosquitoes, and avian samples by a TaqMan reverse transcriptase-PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4066–4071. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.11.4066-4071.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bon A, Schiavoni G, D'Agostino G, Gresser I, Belardelli F, Tough DF. Type i interferons potently enhance humoral immunity and can promote isotype switching by stimulating dendritic cells in vivo. Immunity. 2001;14:461–470. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie DS, Vincent MS, Spada FM, Das H, Sugita M, Morita CT, Brenner MB. CD1-mediated gamma/delta T cell maturation of dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1575–1584. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokuno Y, Matsuguchi T, Takano M, et al. Expression of toll-like receptor 2 on gamma delta T cells bearing invariant V gamma 6/V delta 1 induced by Escherichia coli infection in mice. J Immunol. 2000;165:931–940. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munz C, Steinman RM, Fujii S. Dendritic cell maturation by innate lymphocytes: coordinated stimulation of innate and adaptive immunity. J Exp Med. 2005;202:203–207. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng G, Wang HY, Peng W, Kiniwa Y, Seo KH, Wang RF. Tumor-infiltrating gammadelta T cells suppress T and dendritic cell function via mechanisms controlled by a unique toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Immunity. 2007;27:334–348. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletnev AG, Swayne DE, Speicher J, Rumyantsev AA, Murphy BR. Chimeric West Nile/dengue virus vaccine candidate: Preclinical evaluation in mice, geese and monkeys for safety and immunogenicity. Vaccine. 2006;24:6392–6404. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roehrig JT, Staudinger LA, Hunt AR, Mathews JH, Blair CD. Antibody prophylaxis and therapy for flavivirus encephalitis infections. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;951:286–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb02704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Efficient presentation of soluble antigen by cultured human dendritic cells is maintained by granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor plus interleukin 4 and downregulated by tumor necrosis factor alpha. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1109–1118. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel MA, Diamond MS. Alpha/beta interferon protects against lethal West Nile virus infection by restricting cellular tropism and enhancing neuronal survival. J Virol. 2005;79:13350–13361. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13350-13361.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz O, Diebold SS, Chen M, et al. Toll-like receptor 3 promotes cross-priming to virus-infected cells. Nature. 2005;433:887–892. doi: 10.1038/nature03326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwacha MG, Daniel T. Up-regulation of cell surface Toll-like receptors on circulating gammadelta T-cells following burn injury. Cytokine. 2008;44:328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata K, Yamada H, Hara H, Kishihara K, Yoshikai Y. Resident Vdelta1+ gammadelta T cells control early infiltration of neutrophils after Escherichia coli infection via IL-17 production. J Immunol. 2007;178:4466–4472. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimura H, Nitahara A, Ito A, Tomiyama K, Ito M, Kawai K. Up-regulation of cell surface Toll-like receptor 4-MD2 expression on dendritic epidermal T cells after the emigration from epidermis during cutaneous inflammation. J Dermatol Sci. 2005;37:101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha B, Diamond MS. Role of CD8+ T cells in control of West Nile virus infection. J Virol. 2004;78:8312–8321. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.15.8312-8321.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitati EM, Diamond MS. CD4+ T-cell responses are required for clearance of West Nile virus from the central nervous system. J Virol. 2006;80:12060–12069. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01650-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Town T, Bai F, Wang T, et al. Toll-like receptor 7 mitigates lethal West Nile encephalitis via interleukin 23-dependent immune cell infiltration and homing. Immunity. 2009;30:242–253. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Welte T, McGargill M, et al. Drak2 contributes to West Nile virus entry into the brain and lethal encephalitis. J Immunol. 2008;181:2084–2091. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Town T, Alexopoulou L, Anderson JF, Fikrig E, Flavell RA. Toll-like receptor 3 mediates West Nile virus entry into the brain causing lethal encephalitis. Nat Med. 2004;10:1366–1373. doi: 10.1038/nm1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Scully E, Yin Z, et al. IFN-gamma-producing gammadelta T cells help control murine West Nile virus infection. J Immunol. 2003;171:2524–2531. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Gao Y, Scully E, et al. Gammadelta T cells facilitate adaptive immunity against West Nile virus infection in mice. J Immunol. 2006;177:1825–1832. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Lobigs M, Lee E, Mullbacher A. CD8+ T cells mediate recovery and immunopathology in West Nile virus encephalitis. J Virol. 2003;77:13323–13334. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.24.13323-13334.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Upregulation of cell surface molecules on CD11c+ splenocytes after WNV infection. A. CD11c+ cells were gated for analysis of the percentage of CD40+, CD80+, CD86+ and MHC class II+. Data are presented as means ± SEM, n = 4 or 5. ** P < 0.01 for WNV-infected (IF) vs. non-infected (NF). † P < 0.05 or †† P < 0.01 for wild-type (WT) vs. TCRδ−/− mice. P values were calculated with a non-paired Student’st test. B, Surface expression of CD40, CD80, CD86 and MHC class II in splenic CD11c+ cells of non-infected and WNV-infected mice. Results are representative of three experiments.