Abstract

We have been analyzing genes for reproductive isolation by replacing Drosophila melanogaster genes with homologs from Drosophila simulans by interspecific backcrossing. Among the introgressions established, we found that a segment of the left arm of chromosome 2, Int(2L)S, carried recessive genes for hybrid sterility and inviability. That nuclear pore protein 160 (Nup160) in the introgression region is involved in hybrid inviability, as suggested by others, was confirmed by the present analysis. Male hybrids carrying an X chromosome of D. melanogaster were not rescued by the Lethal hybrid rescue (Lhr) mutation when the D. simulans Nup160 allele was made homozygous or hemizygous. Furthermore, we uniquely found that Nup160 is also responsible for hybrid sterility. Females were sterile when D. simulans Nup160 was made homozygous or hemizygous in the D. melanogaster genetic background. Genetic analyses indicated that the D. simulans Nup160 introgression into D. melanogaster was sufficient to cause female sterility but that other autosomal genes of D. simulans were also necessary to cause lethality. The involvement of Nup160 in hybrid inviability and female sterility was confirmed by transgene experiment.

INVESTIGATING the genetic bases of reproductive isolation is important for understanding speciation (Sawamura and Tomaru 2002; Coyne and Orr 2004; Wu and Ting 2004; Noor and Feder 2006; Presgraves 2010). In fact, continued interest in this issue has led to the isolation of several genes that are responsible for hybrid sterility and inviability in Drosophila (Ting et al. 1998; Barbash et al. 2003; Presgraves et al. 2003; Brideau et al. 2006; Masly et al. 2006; Phadnis and Orr 2009; Prigent et al. 2009; Tang and Presgraves 2009). Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila simulans are the best pair for such genetic analyses (Sturtevant 1920). Hybrid male lethality in the cross between D. melanogaster females and D. simulans males is caused by incompatibility involving chromatin-binding proteins (Barbash et al. 2003; Brideau et al. 2006), and hybrid female lethality in the reciprocal cross is caused by incompatibility between a maternally supplied factor and a repetitive satellite DNA (Sawamura et al. 1993a; Sawamura and Yamamoto 1997; Ferree and Barbash 2009). Furthermore, individuals with the genotype equivalent to the backcrossed generation exhibit different incompatibilities (Pontecorvo 1943; Presgraves 2003), two components of which have been identified (Presgraves et al. 2003; Tang and Presgraves 2009). Because of the discovery of rescuing mutations that prevent hybrid inviability and sterility (Watanabe 1979; Hutter and Ashburner 1987; Sawamura et al. 1993a,b; Davis et al. 1996; Barbash and Ashburner 2003), chromosome segments from D. simulans can be introgressed into the D. melanogaster genome (Sawamura et al. 2000; Masly et al. 2006). For example, introgression of the D. simulans chromosome 4 or Y into D. melanogaster results in male sterility (Muller and Pontecorvo 1940; Orr 1992), and the recessive sterility by the chromosome 4 introgression is attributed to an interspecific gene transposition between chromosomes (Masly et al. 2006).

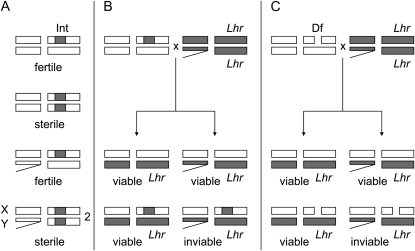

The other successful introgressions of this type are the tip and the middle regions of the left arm of chromosome 2, Int(2L)D and Int(2L)S, respectively (Sawamura et al. 2000). Both female and male Int(2L)S homozygotes are sterile (Figure 1A), and the recessive sterility genes have been mapped with recombination and complementation assays against deficiencies. The male sterility genes are polygenic and interact epistatically with each other (Sawamura and Yamamoto 2004; Sawamura et al. 2004b), but the female sterility gene has been mapped to a 170-kb region containing only 20 open reading frames (ORFs) (Sawamura et al. 2004a). Interestingly, Int(2L)S also carries a recessive lethal gene whose effect is detected only in a specific genotype (Figure 1B). Lethality in hybrid males from the cross between D. melanogaster females and D. simulans males is rescued by the Lethal hybrid rescue (Lhr) mutation in D. simulans (Watanabe 1979), but the hybrid males cannot be rescued if they carry the introgression, presumably because of incompatibility between an X-linked gene(s) of D. melanogaster and a homozygous D. simulans gene in the Int(2L)S region (Sawamura 2000). Because the female sterility gene and the lethal gene were not separated by recombination, Sawamura et al. (2004a) suggested that female sterility and lethality may be a consequence of the pleiotropic effects of a single gene.

Figure 1.—

Viability and fertility of flies with various genotypes. (A) Females and males that are heterozygous or homozygous for the D. simulans introgression Int(2L)S (Int) in the D. melanogaster genetic background. (B) Four genotypic classes from the cross between introgression heterozygote [Int(2L)S/CyO] females and D. simulans Lethal hybrid rescue (Lhr) males. (C) Four genotypic classes from the cross between D. melanogaster females with a deficiency (Df) [Df(2L)/CyO] and D. simulans Lhr males. Open chromosome regions are from D. melanogaster, and shaded ones are from D. simulans.

Because the hybrid lethal gene on Int(2L)S is recessive, the gene can be mapped by deficiencies instead of using introgression (Figure 1C) (Sawamura 2000; Sawamura et al. 2004a). In fact, hybrid males carrying a deficiency encompassing this region (hemizygous for the D. simulans genes) and the D. melanogaster X chromosome are lethal even if they carry the hybrid rescue mutation (see also Presgraves 2003). Tang and Presgraves (2009) subsequently narrowed down this region with multiple deficiencies and identified the hybrid lethal gene with a complementation test and transformation. We confirmed their conclusion and report our data here. In the transformation experiment, we used the natural promoter of the gene, instead of overexpressing the gene (Tang and Presgraves 2009), and we directly indicated, for the first time, that the hybrid lethal gene is also responsible for the female sterility of introgression homozygotes. The D. simulans allele of the gene seems to be nonfunctional on the genetic background of D. melanogaster. Moreover, our results indicated that this gene and chromosome X of D. melanogaster are not sufficient to explain the inviability and that another autosomal gene(s) in D. simulans is required.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly strains and crosses:

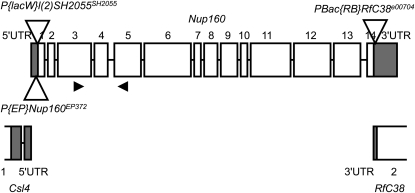

Int(2L)D+S was used for the D. simulans introgression to D. melanogaster (Sawamura et al. 2000). Because introgression homozygotes are sterile in both females and males, the introgression is maintained with a chromosome 2 balancer, CyO-CR2 (simply called CyO in the previous and current reports). The cytoplasm, which was originally from D. simulans, was substituted for D. melanogaster cytoplasm in the introgression line used in this report. Our preliminary analyses showed that Int(2L)D has an effect on male fertility but does not on viability or female fertility. We used deficiencies and insertion mutations (Figures 2 and 3). Three of them are the insertions in Nup160: P{EP}Nup160EP372 in the 5′ UTR, P{lacW}l(2)SH2055SH2055 in exon 1, and PBac{RB}RfC38e00704 in the 3′ UTR (see FlyBase, http://flybase.org/; Tweedie et al. 2009). The insertion site and the direction of the insert were determined by sequencing DNA around the right boundary of P{lacW}l(2)SH2055SH2055. These deficiencies and insertion mutations were originally balanced with CyO but were substituted with CyO-CR2 to easily recognize balancer carriers by the rough-eye phenotype. The curly-wing phenotype that is produced by CyO is not always reliable.

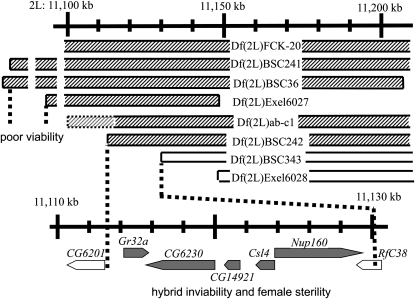

Figure 2.—

Mapping genes for hybrid inviability and female sterility. The region shown corresponds to cytological position 32C-E on chromosome 2. The scale at the top indicates the physical map (nucleotide position), and the extent of deficiencies used are shown by ribbons (hatched, not complemented for viability and fertility; open, complemented). The region enlarged at the bottom corresponds to 32D4, and seven ORFs are shown with arrows (the coded strand is indicated by the direction of the arrow). The solid ORFs are five candidates for hybrid inviability and female sterility. Also indicated is the region responsible for the poor viability of flies in which genes from D. simulans are hemizygous in the D. melanogaster genetic background.

Figure 3.—

Genetic structure (5′ and 3′ UTRs and numbered exons/introns) of Nup160 and the positions of transposon insertions (open triangles). P{lacW}l(2)SH2055SH2055 and PBac{RB}RfC38e00704 are on the forward strand, and P{EP}Nup160EP372 is on the reverse strand. The insertion site of P{lacW}l(2)SH2055SH2055 was determined to be just 5′ of the nucleotide position +16 of Nup160. The positions of PCR primers are indicated by arrowheads. Also shown are part of Csl4 and RfC38, which are encoded on the opposite strand.

The breakpoints of Df(2L)BSC and Df(2L)Exel deficiencies can be predicted at the nucleotide position level because they were made with site-specific recombination between different transposon insertions whose insertion sites had previously been determined (Parks et al. 2004; Ryder et al. 2004, 2007; Thibault et al. 2004). The left breakpoints of Df(2L)BSC242 and Df(2L)BSC343, which needed to be precisely determined for this study (Figure 2), were confirmed by polymerase chain reaction and restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR–RFLP). Df(2L)ab-c1 is a deficiency in the P{lacW}abk02807 chromosome that was newly induced by X-ray irradiation. We determined the right breakpoint to be to the right of cmet using complementation tests and the left breakpoint to be between Ge-1 and Gr32a using PCR–RFLP.

To examine female fertility, tester females were crossed to males from the Oregon-R (OR) strain of D. melanogaster. Eggs were collected for 8 hr, and their hatchability was examined 24 hr later. Sterile females produced normal-looking eggs (see Sawamura et al. 2004a). To examine hybrid viability, tester females were crossed to Lhr males of D. simulans. All flies were reared at 25° because hybrids are fully viable at this temperature when they have Lhr (Barbash et al. 2000).

Transformation:

A genomic fragment of ∼9 kb, including three ORFs (Csl4, Nup160, and RfC38; see Figure 2), was PCR-amplified using the isogenic y; cn bw sp strain of D. melanogaster as the template. Amplification was conducted at 94° for 2 min followed by 30 cycles of 94° for 15 s, 61.8° for 30 s, and 68° for 9 min, using KOD –Plus– (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan) as the DNA polymerase. The primer pair used was 5′-AAAAGGCCTCTGCGACTGACAATAGGAAGG-3′ and 5′-AAAAGGCCTCTCCATGTTCCACTCCGTTC-3′ (the introduced StuI sites are underlined). The PCR product was digested by StuI and ligated into the EcoRV site of pBlueScript II SK+ (Stratagene). The cloned DNA segment was sequenced and confirmed not to carry mutations in the Nup160 ORF (we did find one synonymous substitution in Csl4 and another downstream of Csl4). The 9-kb fragment was subcloned into the EcoRI and KpnI sites of the pattB plasmid that carries the attB sequence and the mini-white (w+) gene (Groth et al. 2004). The construct was injected into embryos from the y sc v P{y+t7.7=nos-phiC31\int.NLS}X; P{y+t7.7=CaryP}attP2 strain of D. melanogaster to allow for ϕC31-targeted site-specific recombination into the attP landing site (68A4 on chromosome 3) (Groth et al. 2004; Bateman et al. 2006; Bischof et al. 2007). The resultant transgene is hereafter abbreviated as P{w+ Nup160mel}. Flies carrying both Int(2L)D+S and P{w+ Nup160mel} were produced by conventional crossings. Females heterozygous for P{w+ Nup160mel} were used for rescue experiments. Sibling females not carrying the transgene were used as the control.

RT–PCR:

Using the RNAlater RNA Stabilization Solution and an RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN, Tokyo), RNA was extracted from ovaries dissected from 8 to 10, 1- to 3-week-old virgin females. The samples were from Int(2L)D+S homozygotes, the OR strain of D. melanogaster, and the C167.4 strain of D. simulans. cDNA was reverse-transcribed from mRNA using SuperScript III (Invitrogen, Tokyo) after treatment with DNase I. PCR amplification was conducted at 94° for 2 min followed by 25 cycles of 98° for 10 s, 60° for 30 s, and 68° for 20 s, with a final extension reaction at 68° for 7 min using KOD plus ver. 2 (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan) as the DNA polymerase. The primer pair used for Nup160 was 5′-TCCCAGTCAGCCTACTTTGC-3′ and 5′-AACTCAGCTCGGGAATTGTG-3′ (see Figure 3 for primer positions). Our preliminary observations (of sequencing and RT–PCR for other parts of the ORF) indicated that the gene structure of Nup160 from D. simulans is the same as that from D. melanogaster. RpL32 (= rp49) was analyzed as an internal control in which the primer pair 5′-AGATCGTGAAGAAGCGCACCAAG-3′ and 5′-CACCAGGAACTTCTTGAATCCGG-3′ was used.

RESULTS

Nup160 causes hybrid inviability:

First, the hybrid lethal gene on Int(2L)S was mapped by deficiencies as shown in Table 1, some of which had also been used by Tang and Presgraves (2009). Male viability was complemented by Df(2L)BSC343 but not by Df(2L)BSC242, indicating that the gene is between the left breakpoints of the deficiencies (Figure 2). Thus, candidate genes for the inviability were Gr32a, CG6230, CG14921, Csl4, and Nup160. Next, we tested several transposon insertions to identify the gene and found an insertion mutation (PBac{RB}RfC38e00704) that did not complement the viability (Table 1). This piggyBac insertion carrying a splice acceptor sequence was located in the 3′ UTRs of RfC38 and Nup160 (Figure 3). Because RfC38 was excluded as a candidate by Df(2L)BSC343, we concluded that Nup160 is the causative gene. But two other insertion mutations in Nup160 (P{EP}Nup160EP372 and P{lacW}l(2)SH2055SH2055) complemented the viability [see also Tang and Presgraves (2009) for the former]. P{EP}Nup160EP372 and P{lacW}l(2)SH2055SH2055 homozygotes were weakly viable in D. melanogaster (viability 0.04 and 0.16, respectively), although hemizygotes were inviable. In contrast, both PBac{RB}RfC38e00704 homozygotes and hemizygotes were inviable.

TABLE 1.

Crosses of D. melanogaster females and D. simulans Lhr males

| Used in Tang and Presgraves (2009) | Females |

Males |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal genotypea | Cy | Cy+ | Viabilityb | Cy | Cy+ | Viabilityb | |

| Df(2L)FCK-20/CyOc | Yes | 321 | 325 | 1.01 | 168 | 0 | 0 |

| Df(2L)BSC241/CyO | No | 255 | 236d | 0.93 | 171 | 0 | 0 |

| Df(2L)BSC36/CyO | Yes | 427 | 383 | 0.90 | 358 | 0 | 0 |

| Df(2L)Exel6027/CyO | Yes | 378e | 316f | 0.84 | 316 | 0 | 0 |

| Df(2L)ab-c1/CyO | No | 194 | 237e | 1.22 | 66 | 1g | <0.02 |

| Df(2L)BSC242/CyO | No | 282 | 231e | 0.82 | 207 | 1g | <0.01 |

| Df(2L)BSC343/CyO | No | 240 | 230 | 0.96 | 197 | 187 | 0.95 |

| Df(2L)Exel6028/CyO | Yes | 222 | 174 | 0.78 | 187 | 179e | 0.96 |

| P{EP}Nup160EP372/CyO | Yes | 232 | 200 | 0.86 | 209 | 197 | 0.94 |

| P{lacW}l(2)SH2055SH2055/CyO | No | 355 | 333 | 0.94 | 133 | 194 | 1.46 |

| PBac{RB}RfC38e00704/CyO | Yes | 196 | 214 | 1.09 | 199 | 1h | 0 |

Only the second chromosomes are indicated. P{EP}Nup160EP372 is synonymous for P{EP}CG4738EP372.

Viability of Cy+ flies relative to Cy flies was calculated as the number of Cy+ flies divided by the number of Cy flies because the Cy:Cy+ ratio was expected to be 1:1.

Data after Sawamura et al. (2004a).

Three M.

Three flies had the Minute phenotype (M, presumably haplo-4).

One M.

Presumably XO carrying a D. simulans X chromosome.

XO apparent from an X-linked marker.

Nup160 causes hybrid female sterility:

The same deficiencies and insertion mutations as above were used to identify the female sterility gene. First, we counted offspring to examine the fertility of females heterozygous for the introgression and the tester chromosomes (Table 2). As with male viability, female fertility was complemented by Df(2L)BSC343 but not by Df(2L)BSC242. Among the three insertion mutations for Nup160, P{EP}Nup160EP372 complemented the fertility, but PBac{RB}RfC38e00704 did not. P{lacW}l(2)SH2055SH2055 only partially complemented the fertility. The reduced fertility in P{lacW}l(2)SH2055SH2055/Int(2L)D+S was confirmed by measuring egg hatchability. In addition to PBac{RB}RfC38e00704, P{lacW}l(2)SH2055SH2055 showed a severe reduction of fertility (Table 3). The P{lacW}l(2)SH2055SH2055 insertion is adjacent to the 5′ UTR of Csl4 and may also affect the transcription of Csl4. It is, however, reasonable to assume that Nup160 is the female sterility gene because PBac{RB}RfC38e00704, whose insertion site is in the 3′ UTR of RfC38 and Nup160, also resulted in female sterility. In conclusion, Nup160 introgression from D. simulans causes not only hybrid inviability but also female sterility in introgression homozygotes.

TABLE 2.

Fertility of females crossed with D. melanogaster Oregon-R males

| Maternal genotypea | No. of offspring per femaleb |

|---|---|

| Df(2L)FCK-20/Int(2L)D+S | 0 |

| Df(2L)BSC241/Int(2L)D+S | 0 |

| Df(2L)BSC36/Int(2L)D+S | 0 |

| Df(2L)Exel6027/Int(2L)D+S | 0 |

| Df(2L)ab-c1/Int(2L)D+S | 0 |

| Df(2L)BSC242/Int(2L)D+S | 0 |

| Df(2L)BSC343/Int(2L)D+S | >100 |

| Df(2L)Exel6028/Int(2L)D+S | >100 |

| P{EP}Nup160EP372/Int(2L)D+S | >100 |

| P{lacW}l(2)SH2055SH2055/Int(2L)D+S | 29.1 |

| PBac{RB}RfC38e00704/Int(2L)D+S | 0 |

| Int(2L)D+S/Int(2L)D+S; +/+c | 0 |

| Int(2L)D+S/Int(2L)D+S; P{w+ Nup160mel}/+c | 89.2 |

Only the second and third chromosomes are indicated.

At least 20 females were tested (five pairs × four replicates). An exception is Df(2L)BSC36/Int(2L)D+S, in which only two females were tested because of their low viability.

Siblings from a cross (see materials and methods).

TABLE 3.

Hatchability of eggs from females crossed with D. melanogaster Oregon-R males

| No. of eggs |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal genotypea | Collected | Hatched | Hatchability (%) |

| P{EP}Nup160EP372/Int(2L)D+S | 520 | 408 | 78.5 |

| P{EP}Nup160EP372/CyO | 520 | 393 | 75.6 |

| P{lacW}l(2)SH2055SH2055/Int(2L)D+S | 520 | 22 | 4.2 |

| P{lacW}l(2)SH2055SH2055/CyO | 520 | 456 | 87.7 |

| PBac{RB}RfC38e00704/Int(2L)D+S | 520 | 0 | 0 |

| PBac{RB}RfC38e00704/CyO | 520 | 413 | 79.4 |

| Int(2L)D+S/CyO | 355 | 259 | 73.0 |

| Oregon-R | 480 | 383 | 79.8 |

| Int(2L)D+S/Int(2L)D+S; +/+b | 120 | 0 | 0 |

| Int(2L)D+S/Int(2L)D+S; P{w+ Nup160mel}/+b | 400 | 89 | 22.2 |

Only the second and third chromosomes are indicated.

Siblings from a cross (see materials and methods).

Nup160 transgene rescues hybrid inviability and female sterility:

In the cross between w/w; Int(2L)D+S/CyO; P{w+ Nup160mel}/+ females and D. simulans Lhr males, all the introgression-bearing (Cy+) sons carried the transgene (w+) (Table 4). Furthermore, w/w; Int(2L)D+S/Int(2L)D+S; +/+ females were sterile, but the sibling w/w; Int(2L)D+S/Int(2L)D+S; P{w+ Nup160mel}/+ females were fertile (Table 2). It should be noted here that fertility rescue by the transgene was incomplete (Table 3), presumably because of a position effect or a partial absence of a regulatory region of Nup160 in the transfomant. Thus, the hypothesis that Nup160 is responsible for both hybrid inviability and female sterility was confirmed.

TABLE 4.

A cross of w/w; Int(2L)D+S/CyO; P{w+ Nup160mel}/+ females and D. simulans Lhr males

| Presence of P{w+ Nup160mel} | Females |

Males |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cy | Cy+ | Viabilitya | Cy | Cy+ | Viabilitya | |

| Yes | — | — | — | 15 | 47 | 3.13b |

| No | — | — | — | 58 | 0 | 0c |

| Unknown | 149 | 175 | 1.17 | — | — | — |

Viability of Cy+ flies relative to Cy flies was calculated as the number of Cy+ flies divided by the number of Cy flies, because the Cy:Cy+ ratio is expected to be 1:1.

Rescued. Irregularly high, presumably because of low viability of Cy males.

Control.

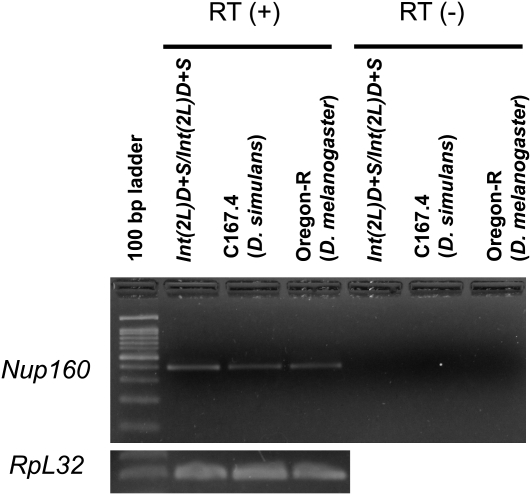

Nup160 gene expression in sterile females:

We next addressed the question of whether D. simulans Nup160 (Nup160sim) is transcribed in sterile females (introgression homozygotes in the D. melanogaster genetic background). RT–PCR (Figure 4) indicated that Nup160sim is expressed, at least in the ovary, as in wild-type D. melanogaster and D. simulans.

Figure 4.—

RT–PCR for Nup160. The gene is transcribed in the ovary of introgression homozygotes. RT–PCR for RpL32 is shown as an internal control.

Other potential sites for hybrid incompatibility:

When Int(2L)D+S was made heterozygous with deficiencies, several irregular morphological abnormalities were found in some flies: notched wing margins, shortening of vein L5, irregular reduction in abdominal tergites, and erect or missing postscutellars (Table 5). Pure D. melanogaster flies heterozygous for the deficiencies did not show such abnormalities other than missing postscutellars, which were seen at a low frequency. Because flies heterozygous for the Nup160 mutations and Int(2L)D+S did not exhibit these phenotypes, these abnormalities may not be attributable to the single gene Nup160.

TABLE 5.

Crosses of Int(2L)D+S/CyO females and D. melanogaster males

| Females |

Males |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paternal genotype | Cy | Cy+ | Viabilitya | Cy | Cy+ | Viabilitya | Effect on Cy+ fliesb |

| Df(2L)FCK-20/CyO | 164 | 14 | 0.17 | 177 | 59 | 0.67 | Yes |

| Df(2L)BSC241/CyO | 1215 | 1 | <0.01 | 1242 | 10 | 0.02 | Yes |

| Df(2L)BSC36/CyO | 2000 | 2 | <0.01 | 1929 | 5 | <0.01 | Yes |

| Df(2L)Exel6027/CyO | 195 | 36 | 0.37 | 185 | 52 | 0.56 | Yes |

| Df(2L)ab-c1/CyO | 127 | 31 | 0.49 | 149 | 71 | 0.95 | Yes |

| Df(2L)BSC242/CyO | 218 | 7 | 0.06 | 209 | 44 | 0.42 | Yes |

| Df(2L)BSC343/CyO | 199 | 120 | 1.21 | 225 | 114 | 1.01 | No |

| Df(2L)Exel6028/CyO | 152 | 103 | 1.36 | 179 | 95 | 1.06 | No |

| P{EP}Nup160EP372/CyO | 133 | 92 | 1.38 | 172 | 105 | 1.22 | No |

| P{lacW}l(2)SH2055SH2055/CyO | 248 | 127 | 1.02 | 247 | 131 | 1.06 | No |

| PBac{RB}RfC38e00704/CyO | 195 | 103 | 1.06 | 201 | 123 | 1.22 | No |

Viability of Cy+ flies relative to Cy flies was calculated as two times the number of Cy+ flies divided by the number of Cy flies because the Cy:Cy+ ratio is expected to be 2:1.

See text under Other potential sites for hybrid incompatibility for the phenotype.

The other unexpected result was poor viability of flies that were heterozygous for Int(2L)D+S and some deficiencies (Table 5). No haplo-insufficiency locus was included in the region tested; hemizygotes were fully viable in D. melanogaster. The poor viability may be partially due to the pleiotropic effects of the gene(s) responsible for irregular morphologies. The viability was generally lower (<1) when accompanied by an irregular phenotype. Interestingly, females were affected more than males (female viability < male viability in all six genotypes). Extremely poor viability (∼0.02) was seen in Df(2L)BSC241/Int(2L)D+S and Df(2L)BSC36/Int(2L)D+S. Some of the D. simulans genes (Nup154, Art8, dUTPase, Samuel, Acp32CD, CG14913, and CG18666) in the 62-kb region (Figure 2; Tweedie et al. 2009) are required to be hemizygous for the poor viability.

DISCUSSION

We first confirmed the conclusion of Tang and Presgraves (2009) that D. simulans Nup160 (Nup160sim) causes hybrid inviability. Male hybrids from the cross between D. melanogaster females and D. simulans males were rescued from inviability by the Lhr mutation but were not rescued if they were hemizygous for Nup160sim (Table 1). Furthermore, the lethality was rescued by the D. melanogaster Nup160 (Nup160mel) transgene (Table 4). The genotypic difference between homozygotes (Sawamura 2000) and hemizygotes (Tang and Presgraves 2009) also suggests that the hybrid male lethality was not due to haplo-insufficiency of the locus. Tang and Presgraves (2009) complemented the hybrid male lethality by overexpressing Nup160mel in hybrids but did not test the reciprocal genotype (i.e., overexpression of Nup160sim). Here the introgression directly showed that a hybrid homozygous for Nup160sim is still lethal, whereas a hybrid with the Nup160mel/Nup160sim genotype is viable.

We showed here that homozygous (or hemizygous) Nup160sim also resulted in female sterility in the D. melanogaster genetic background (Tables 2 and 3) and that female sterility was also rescued by the Nup160mel transgene (Table 3). Thus, the same gene is responsible for hybrid inviability and female sterility in different genetic backgrounds, which was previously suggested by Sawamura et al. (2004a). Barbash and Ashburner (2003) have suggested that the Hybrid male rescue (Hmr) mutation of D. melanogaster rescues not only lethal hybrids but also sterile female hybrids. Thus, the same hybrid incompatibility genes can affect more than one component of hybrid fitness.

On the basis of their results using the compound X chromosomes of D. melanogaster, Tang and Presgraves (2009) suggested that one of the partners of the Nup160sim-related incompatibility must be encoded on chromosome X because male hybrids carrying the D. simulans X chromosome are viable. If the incompatibility resulted from the effect of a single pair of genes, Nup160sim homozygotes (or hemizygotes) in the D. melanogaster genetic background would be inviable. In fact, these flies were viable (although females were sterile), which is especially informative because they are different from the lethal genotype only in the autosomal (and the Y) chromosome (Figure 1, A and B). These findings clearly indicate that Nup160sim and a gene(s) on the D. melanogaster X chromosome are not sufficient to cause inviability. Another autosomal factor(s) of D. simulans is required. Although compound X chromosomes are powerful tools for studying X chromosome effects, and the D. melanogaster X chromosome was required for inviability (Tang and Presgraves 2009), the introgression analyzed here revealed a further complication underlying the incompatibility leading to inviability.

Nup160 encodes a 160-kD nuclear pore complex (NPC) scaffold protein. NPC contains ∼30 protein components, and the scaffold proteins (i.e., the Nup107-160 subcomplex) allow the transport of macromolecules between the nucleus and the cytoplasm (for recent reviews see Antonin et al. 2008; D'Angelo and Hetzer 2008; Capelson and Hetzer 2009; Mason and Goldfarb 2009; Köhler and Hurt 2010). Hybrid lethality revealed here may result from mRNA accumulation in the nucleus. Recent investigations have also indicated broader functions for the NPC in kinetochore formation and transcriptional regulation, including dosage compensation (Mendjan et al. 2006; Orjalo et al. 2006; Zuccolo et al. 2007; Capelson et al. 2010; Mishra et al. 2010; Vaquerizas et al. 2010). Therefore, the mechanism of female sterility, i.e., karyogamy failure (Sawamura et al. 2004a), in the introgression homozygotes may be different from that of the hybrid lethality.

What are the mechanisms of Nup160 incompatibility? RT–PCR indicated that Nup160sim is expressed in the D. melanogaster genetic background in the ovary, and this has been confirmed by a microarray analysis (A. Ogura, J. Ranz and D. Hartl, personal communication). The incompatibility may be attributable to abnormal protein–protein interactions rather than to failure of transcriptional regulation. Nup96, which encodes another protein of the Nup107-160 subcomplex, is one of the candidates for the partners of the interaction. Interestingly, D. simulans Nup96 (Nup96sim), which is located on chromosome 3, behaves similarly to Nup160sim in the hybrid cross: male hybrids from the cross between D. melanogaster females and D. simulans Lhr males are not rescued if they are hemizygous for Nup96sim (Presgraves et al. 2003). The other partner of the incompatibility must be encoded on chromosome X, and only one NPC peripheral protein gene, Nup153, has been identified on that chromosome (Tweedie et al. 2009). Thus, D. melanogaster Nup153 (Nup153mel) is the candidate, as was suggested by Tang and Presgraves (2009). Because some restrictive Nup mutations lead to synthetic lethality in yeast (Fabre and Hurt 1997), it is not surprising that certain NPC protein interactions result in hybrid lethality in Drosophila.

Presgraves and co-workers detected recurrent adaptive evolution of NPC proteins in the D. melanogaster and D. simulans lineages by population genetic analysis and suggested selection-driven coevolution among the molecular interactors within species (Presgraves et al. 2003; Presgraves and Stephan 2007; Tang and Presgraves 2009). Why do NPC protein genes evolve so quickly at the molecular level? The nuclear entry of retroviruses and retrotransposons is mediated by NPC (e.g., Dang and Levin 2000; Petersen et al. 2000; von Kobbe et al. 2000; Gustin and Sarnow 2001; Sistla et al. 2007; Beliakova-Bethell et al. 2009), and this host–pathogen interaction may have accelerated the evolution of NPC proteins. Alternatively, the NPC proteins may have evolved so quickly to interact properly with rapidly evolving sequences of the centromere and its surrounding heterochromatin (Sawamura et al. 1993b; Henikoff et al. 2001; Bayes and Malik 2009; Ferree and Barbash 2009).

In summary, we reported the finding of Nup160 as a hybrid female sterility gene. While the hybrid lethality effect of Nup160 is well established, nobody had predicted the female sterility effect. We also showed that Nup160 from D. simulans in the D. melanogaster genetic background by itself did not cause lethality when homozygous and that other autosomal partners were required. Thus, this study raises interesting questions about the molecular nature of the defect that causes female sterility and whether more parts of the incompatibility network (in addition to Nup160) might be shared between the hybrid female sterility and lethality phenotypes.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Bloomington, Exelixis, Kyoto, and Szeged Drosophila stock centers for providing fly strains. We thank A. Ogura and J. Ranz for sharing unpublished data and members of the N. Imamoto lab for discussion. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (21570001) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science to K.S.

References

- Antonin, W., J. Ellenberg and E. Dultz, 2008. Nuclear pore complex assembly through the cell cycle: regulation and membrane organization. FEBS Lett. 582 2004–2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbash, D. A., and M. Ashburner, 2003. A novel system of fertility rescue in Drosophila hybrids reveals a link between hybrid lethality and female sterility. Genetics 163 217–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbash, D. A., J. Roote and M. Ashburner, 2000. The Drosophila melanogaster Hybrid male rescue gene causes inviability in male and female species hybrids. Genetics 154 1747–1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbash, D. A., D. F. Siino, A. M. Tarone and J. Roote, 2003. A rapidly evolving MYB-related protein causes species isolation in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100 5302–5307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, J. R., A. M. Lee and C. T. Wu, 2006. Site-specific transformation of Drosophila via ϕC31 integrase-mediated cassette exchange. Genetics 173 769–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayes, J. J., and H. S. Malik, 2009. Altered heterochromatin binding by a hybrid sterility protein in Drosophila sibling species. Science 326 1538–1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beliakova-Bethell, N., L. J. Terry, V. Bilanchone, R. DaSilva, K. Nagashima et al., 2009. Ty3 nuclear entry is initiated by viruslike particle docking on GLFG nucleoporins. J. Virol. 83 11914–11925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof, J., R. K. Maeda, M. Hediger, F. Karch and K. Basler, 2007. An optimized transgenesis system for Drosophila using germ-line specific ϕC31 integrases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104 3312–3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brideau, N. J., H. A. Flore, J. Wang, S. Maheshwari, X. Wang et al., 2006. Two Dobzhansky-Muller genes interact to cause hybrid lethality in Drosophila. Science 314 1292–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capelson, M., and M. W. Hetzer, 2009. The role of nuclear pores in gene regulation, development and disease. EMBO Rep. 10 697–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capelson, M., Y. Liang, R. Schulte, W. Mair, U. Wagner et al., 2010. Chromatin-bound nuclear pore components regulate gene expression in higher eukaryotes. Cell 140 327–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne, J. A., and H. A. Orr, 2004. Speciation. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA.

- Dang, V. D., and H. L. Levin, 2000. Nuclear import of the retrotransposon Tf1 is governed by a nuclear localization signal that possesses a unique requirement for the FXFG nuclear pore factor Nup124p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20 7798–7812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Angelo, M. A., and M. W. Hetzer, 2008. Structure, dynamics and function of nuclear pore complexes. Trends Cell Biol. 18 456–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, A. W., J. Roote, T. Morley, K. Sawamura, S. Herrmann et al., 1996. Rescue of hybrid sterility in crosses between D. melanogaster and D. simulans. Nature 380 157–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabre, E., and E. Hurt, 1997. Yeast genetics to dissect the nuclear pore complex and nucleocytoplasmic trafficking. Annu. Rev. Genet. 31 277–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferree, P. M., and D. A. Barbash, 2009. Species-specific heterochromatin prevents mitotic chromosome segregation to cause hybrid lethality in Drosophila. PLoS Biol. 7 e1000234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustin, K. E., and P. Sarnow, 2001. Effects of poliovirus infection on nucleo-cytoplasmic trafficking and nuclear pore complex composition. EMBO J. 20 240–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth, A. C., M. Fish, R. Nusse and M. P. Calos, 2004. Construction of transgenic Drosophila by using the site-specific integrase from phage ϕC31. Genetics 166 1775–1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henikoff, S., K. Ahmad and H. S. Malik, 2001. The centromere paradox: stable inheritance with rapidly evolving DNA. Science 293 1098–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutter, P., and M. Ashburner, 1987. Genetic rescue of inviable hybrids between Drosophila melanogaster and its sibling species. Nature 327 331–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler, A., and E. Hurt, 2010. Gene regulation by nucleoporins and links to cancer. Mol. Cell 38 6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masly, J. P., C. D. Jones, M. A. F. Noor, J. Locke and H. A. Orr, 2006. Gene transposition as a cause of hybrid sterility in Drosophila. Science 313 1448–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason, D. A., and D. S. Goldfarb, 2009. The nuclear transport machinery as a regulator of Drosophila development. Sem. Cell Dev. Biol. 20 582–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendjan, S., M. Taipale, J. Kind, H. Holz, P. Gebhardt et al., 2006. Nuclear pore components are involved in the transcriptional regulation of dosage compensation in Drosophila. Mol. Cell 21 811–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, R. K., P. Chakroborty, A. Arnaoutov, B. M. A. Fontoura and M. Dasso, 2010. The Nup107–160 complex and γ-TuRC regulate microtubule polymerization at kinetochores. Nat. Cell Biol. 12 164–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller, H. J., and G. Pontecorvo, 1940. Recombinants between Drosophila species the F1 hybrids of which are sterile. Nature 146 199–200. [Google Scholar]

- Noor, M. A. F., and J. L. Feder, 2006. Speciation genetics: evolving approaches. Nat. Rev. Genet. 7 851–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orjalo, A. V., A. Arnaoutov, Z. Shen, Y. Boyarchuk, S. G. Zeitlin et al., 2006. The Nup107–160 nucleoporin complex is required for correct bipolar spindle assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell 17 3806–3818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr, H. A., 1992. Mapping and characterization of a ‘speciation gene’ in Drosophila. Genet. Res. 59 73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks, A. L., K. R. Cook, M. Belvin, N. A. Dompe, R. Fawcett et al., 2004. Systematic generation of high-resolution deletion coverage of the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Nat. Genet. 36 288–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, J. M., L. S. Her, V. Varvel, E. Lund and J. E. Dahlberg, 2000. The matrix protein of vesicular stomatitis virus inhibits nucleocytoplasmic transport when it is in the nucleus and associated with nuclear pore complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20 8590–8601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phadnis, N., and H. A. Orr, 2009. A single gene causes both male sterility and segregation distortion in Drosophila hybrids. Science 323 376–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontecorvo, G., 1943. Viability interactions between chromosomes of Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila simulans. J. Genet. 45 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Presgraves, D. C., 2003. A fine-scale genetic analisis of hybrid incompatibilities in Drosophila. Genetics 163 955–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presgraves, D. C., 2010. The molecular evolutionary basis of species formation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11 175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presgraves, D. C., and W. Stephan, 2007. Pervasive adaptive evolution among interactors of the Drosophila hybrid inviability gene, Nup96. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24 306–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presgraves, D. C., L. Balagopalan, S. M. Abmayr and H. A. Orr, 2003. Adaptive evolution drives divergence of a hybrid inviability gene between two species of Drosophila. Nature 423 715–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigent, S., H. Matsubayashi and M. T. Yamamoto, 2009. Transgenic Drosophila simulans strains prove the identity of the speciation gene Lethal hybrid rescue. Genes Genet. Syst. 84 353–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder, E., F. Blows, M. Ashburner, R. Bautista-Llacer, D. Coulson et al., 2004. The DrosDel collection: a set of P-element insertions for generating custom chromosomal aberrations in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 167 797–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder, E., M. Ashburner, R. Bautista-Llacer, J. Drummond, J. Webster et al., 2007. The DrosDel deletion collection: a Drosophila genomewide chromosomal deficiency resource. Genetics 177 615–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura, K., 2000. Genetics of hybrid inviability and sterility in Drosophila: Drosophila melanogaster-Drosophila simulans case. Plant Species Biol. 15 237–247. [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura, K., and M. Tomaru, 2002. Biology of reproductive isolation in Drosophila: toward a better understanding of speciation. Popul. Ecol. 44 209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura, K., and M. T. Yamamoto, 1997. Characterization of a reproductive isolation gene, zygotic hybrid rescue, of Drosophila melanogaster by using minichromosomes. Heredity 79 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura, K., and M. T. Yamamoto, 2004. The minimal interspecific introgression resulting in male sterility in Drosophila. Genet. Res. 84 81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura, K., T. Taira and T. K. Watanabe, 1993. a Hybrid lethal systems in the Drosophila melanogaster species complex. I. The maternal hybrid rescue (mhr) gene of Drosophila simulans. Genetics 133 299–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura, K., M. T. Yamamoto and T. K. Watanabe, 1993. b Hybrid lethal systems in the Drosophila melanogaster species complex. II. The Zygotic hybrid rescue (Zhr) gene of D. melanogaster. Genetics 133 307–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura, K., A. W. Davis and C. I. Wu, 2000. Genetic analysis of speciation by means of introgression into Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97 2652–2655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura, K., T. L. Karr and M. T. Yamamoto, 2004. a Genetics of hybrid inviability and sterility in Drosophila: dissection of introgression of D. simulans genes in D. melanogaster genome. Genetica 120 253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura, K., J. Roote, C. I. Wu and M. T. Yamamoto, 2004. b Genetic complexity underlying hybrid male sterility in Drosophila. Genetics 166 789–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sistla, S., P. J. Vincent, W. C. Xia and D. Balasundaram, 2007. Multiple conserved domains of the nucleoporin Nup124p and its orthologs Nup1p and Nup153 are critical for nuclear import and activity of the fission yeast Tf1 retrotransposon. Mol. Biol. Cell 18 3692–3708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant, A. H., 1920. Genetic studies on Drosophila simulans. I. Introduction. Hybrids with Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 5 488–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, S., and D. C. Presgraves, 2009. Evolution of the Drosophila nuclear pore complex results in multiple hybrid incompatibilities. Science 323 779–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibault, S. T., M. A. Singer, W. Y. Miyazaki, B. Milash, N. A. Dompe et al., 2004. A complementary transposon tool kit for Drosophila melanogaster using P and piggyBac. Nat. Genet. 36 283–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting, C. T., S. C. Tsaur, M. L. Wu and C. I. Wu, 1998. A rapidly evolving homeobox at the site of a hybrid sterility gene. Science 282 1501–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tweedie, S., M. Ashburner, K. Falls, P. Leyland, P. McQuilton et al., 2009. FlyBase: enhancing Drosophila gene ontology annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 37 D555–D559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaquerizas, J. M., R. Suyama, J. Kind, K. Miura, N. M. Luscombe et al., 2010. Nuclear pore protein Nup153 and Megator define transcriptionally active regions in the Drosophila genome. PLoS Genet. 6 e1000846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Kobbe, C., J. M. A. van Deursen, J. P. Rodrigues, D. Sitterlin, A. Bachi et al., 2000. Vesicular stomatitis virus matrix protein inhibits host cell gene expression by targeting the nucleoporin Nup98. Mol. Cell 6 1243–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, T. K., 1979. A gene that rescues the lethal hybrids between Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans. Jpn. J. Genet. 54 325–331. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C. I., and C. T. Ting, 2004. Genes and speciation. Nature Rev. Genet. 5 114–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuccolo, M., A. Alves, V. Galy, S. Bolhy, E. Formstecher et al., 2007. The human Nup107–160 nuclear pore subcomplex contributes to proper kinetochore functions. EMBO J. 26 1853–1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]