Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Blood pressure (BP) control is frequently difficult to achieve in patients with predominantly elevated systolic BP. Consequently, these patients frequently require combination therapy including a thiazide diuretic such as hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) and an agent blocking the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Current clinical practice usually limits the daily dose of HCTZ to 25 mg. This often leads to the necessity of using additional antihypertensive agents to control BP in a high proportion of patients.

OBJECTIVES:

To compare the efficacy of two doses of losartan (LOS)/HCTZ combinations in patients with uncontrolled ambulatory systolic hypertension after six weeks of treatment with LOS 100 mg/HCTZ 25 mg (LOS100/HCTZ25).

METHODS:

Following a two- to four-week washout period, subjects with a mean clinic sitting systolic BP of 160 mmHg or higher and a mean ambulatory daytime systolic BP (MDSBP) of 135 mmHg or higher on LOS100/HCTZ25 (n=105; 33 women and 72 men) were randomly assigned to receive LOS 150 mg/HCTZ 25 mg (group 1; n=53) or LOS 150 mg/HCTZ 37.5 mg (LOS150/HCTZ37.5, group 2; n=52). The primary end point was the difference in MDSBP reductions.

RESULTS:

At the end of the six-week treatment period, the respective additional decreases in MDSBP were 1.2 mmHg (P=0.335) on LOS 150 mg/HCTZ 25 mg and 5.6 mmHg (P<0.0001) on LOS150/HCTZ37.5 (difference of 4.4 mmHg; P=0.011). Daytime systolic ambulatory BP goal (lower than 130 mmHg) achievement tended to be higher (25% versus 17%; P=0.313) with LOS150/HCTZ37.5, while it was significantly higher (65% versus 43%; P=0.024) for mean daytime diastolic BP (lower than 80 mmHg). No deleterious metabolic changes were observed.

CONCLUSIONS:

In patients with uncontrolled systolic ambulatory hypertension receiving LOS100/HCTZ25, increasing both HCTZ and LOS dosages simultaneously to LOS150/HCTZ37.5 may be an effective strategy that does not affect metabolic parameters.

Keywords: Ambulatory blood pressure, Angiotensin receptor antagonists, Combination therapy, Hypertension, Losartan/hydrochlorothiazide, Thiazides

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Les patients qui ont une tension artérielle (TA) élevée à prédominance systolique éprouvent souvent de la difficulté à contrôler leur TA. Par conséquent, ces patients ont souvent besoin d’une polythérapie, incluant un diurétique thiazidique comme l’hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) et un agent bloquant le système rénine-angiotensine-aldostérone. D’ordinaire, la pratique clinique limite la dose quotidienne d’HCTZ à 25 mg, ce qui oblige à utiliser d’autres agents antihypertensifs chez une forte proportion de patients afin de contrôler la TA.

OBJECTIFS :

Comparer l’efficacité de deux doses de losartan (LOS) associée à l’HCTZ chez des patients dont l’hypertension systolique ambulatoire n’est pas contrôlée après six semaines de traitement de 100 mg au LOS et de 25 mg à l’HCTZ (100LOS/25HCTZ).

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Après une période d’élimination de deux à quatre semaines, les sujets dont la TA systolique clinique moyenne en position assise était de 160 mmHg ou plus et la TA systolique ambulatoire moyenne de jour (TASMJ), de 135 mmHg ou plus et qui prenaient 100LOS/25HCTZ (n=105; 33 femmes et 72 hommes) ont été aléatoirement divisés pour recevoir 150 mg LOS/25 mg HCTZ (groupe 1; n=53) ou 150 mg LOS/37,5 mg HCTZ (150LOS/37,5HCTZ, groupe 2; n=52). Le paramètre ultime primaire était la différence de réductions de la TASMJ.

RÉSULTATS :

À la fin de la période de traitement de six semaines, les diminutions supplémentaires respectives de TASMJ étaient de 1,2 mmHg (P=0,335) chez les patients qui prenaient 150 mg LOS/25 mg HCTZ, et de 5,6 mmHg (P<0,0001) chez ceux qui prenaient 150LOS/37,5HCTZ (différence de 4,4 mmHg; P=0,011). L’objectif de TA systolique ambulatoire de jour (inférieure à 130 mmHg) tendait à être davantage atteint (25 % par rapport à 17 %; P=0,313) avec 150LOS/37,5HCTZ, mais l’était considérablement plus (65 % par rapport à 43 %; P=0,024) pour la TA diastolique moyenne de jour (inférieure à 80 mmHg). Aucune modification métabolique néfaste n’a été observée.

CONCLUSIONS :

Chez les patients dont l’hypertension systolique ambulatoire n’était pas contrôlée et qui recevaient 100LOS/25HCTZ, l’augmentation simultanée des doses d’HCTZ et de LOS à 150LOS/37,5HCTZ pourrait constituer une stratégie efficace qui n’influe pas sur les paramètres métaboliques.

According to two recent Canadian studies (1,2), control rates of hypertension are markedly increasing in middle-aged (61%) and elderly (67.7%) hypertensive patients, but are more difficult to achieve in patients with predominant systolic hypertension (3). In this regard, most patients may require multiple-drug therapy including a diuretic to achieve their blood pressure (BP) target. Two-drug therapy consisting of an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) and a thiazide diuretic provides additive efficacy through the different actions of the two drugs on the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) (4). Current practice usually limits the daily dose of hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) to 25 mg because of the belief that efficacy can be obtained and that deleterious metabolic effects are not frequent with such a dose.

In a previous study (5), combinations of losartan (LOS) 50 mg with HCTZ 12.5 mg (LOS50/HCTZ12.5) and LOS 100 mg with HCTZ 25 mg (LOS100/HCTZ25) provided a significant systolic and diastolic ambulatory BP (ABP) reduction with a clear dose-response relationship. In contrast, increasing only the thiazide dose from 12.5 mg to 25 mg did not result in additional ABP reduction. In clinical practice, many patients do not attain systolic ABP control with a combination of LOS100/HCTZ25. It was, thus, important to determine whether using greater doses of both the ARB and the diuretic beyond the usual prescribed doses would improve systolic ABP-lowering efficacy compared with just increasing the dose of the ARB or the HCTZ.

The present trial was, thus, designed to evaluate the antihypertensive efficacy and safety of the combination of LOS 150 mg with HCTZ 25 mg (LOS150/HCTZ25) in patients with uncontrolled mean daytime (from 06:00 to 23:00) systolic BP (MDSBP) who were on LOS100/HCTZ25, compared with increasing both LOS and HCTZ (LOS 150 mg combined with HCTZ 37.5 mg [LOS150/HCTZ37.5]).

METHODS

Study population

Men and women 50 years of age or older with a history of uncontrolled moderate to severe systolic hypertension (clinic sitting systolic BP [SBP] of 140 mmHg to 200 mmHg when treated with a maximum of three antihypertensive agents) from three Canadian centres were candidates for enrollment in the trial. Exclusion criteria were as follows: severe hypertension (SBP higher than 200 mmHg and/or diastolic BP [DBP] higher than than 120 mmHg); history of myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass surgery or unstable angina within six months before randomization; history of heart failure, clinically significant atrioventricular conduction disturbances, atrial fibrillation and cerebrovascular accident; and poorly controlled diabetes with markedly elevated glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c; greater than 10%), renal impairment (serum creatinine level greater than 200 mmol/L) and kalemia outside the normal limit range (3.5 mmol/L to 5.5 mmol/L). The study was a prospective, randomized, open-label, blinded end point (PROBE), parallel-group design (6). All patients provided informed consent at enrollment before the washout period. The study protocol was approved by local ethical review boards.

Study design

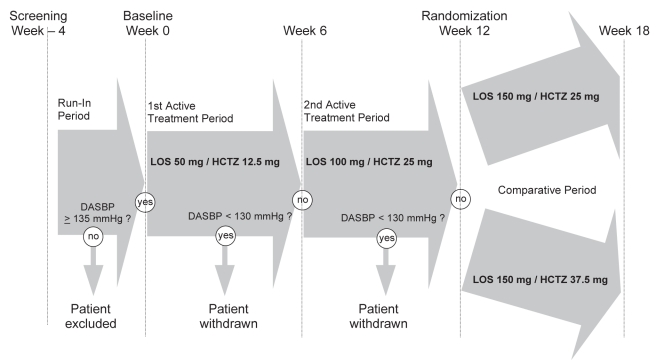

All patients were recruited from the sites’ hypertension clinics. A washout period of one to four weeks was used to identify patients with the enrollment criteria of having both a clinic sitting SBP of 160 mmHg to 200 mmHg and an MDSBP of 135 mmHg or higher. The decision to use ambulatory MDSBP as one criterion for randomization and for the primary end point was prespecified before the study was initiated. This decision was based on a previous study (5) and was made to select only truly hypertensive patients. Because patients in a Canadian study (7) that used a low-dose diuretic/ARB combination as initial therapy achieved BP control more quickly and more effectively (64%), subjects who fulfilled the enrollment criteria were selected to receive a combination of LOS50/HCTZ12.5 during the first six weeks of the study. Patients who did not reach the target MDSBP response of lower than 130 mmHg were titrated to a combination of LOS100/HCTZ25 during a second six-week treatment period. Patients who still did not reach an ambulatory MDSBP response of less than 130 mmHg regardless of their clinic BP after study week 12 were then randomly assigned to the comparison phase of the study; this constituted the baseline. Patients were randomly assigned to receive LOS150/HCTZ25 (group 1) or LOS150/HCTZ37.5 (group 2) for the remaining six weeks of the study (Figure 1).

Figure 1).

Design of the study comparing the effects of losartan (LOS) 150 mg plus hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) 25 mg versus LOS 150 mg plus HCTZ 37.5 mg in hypertension patients whose ambulatory systolic blood pressure remained inadequately controlled after six weeks of receiving LOS 50 mg plus HCTZ 12.5 mg followed by six weeks of LOS 100 mg plus HCTZ 25 mg. DASBP Daytime ambulatory systolic blood pressure

The study medications administered to the patients were given as commercially available drug formulations. Therefore, patients randomly assigned to group 1 received one tablet of LOS100/HCTZ25 and one tablet of LOS 50 mg (total LOS150/HCTZ25), while patients in group 2 were administered one tablet of LOS100/HCTZ25 and one tablet of LOS50/HCTZ12.5 (total LOS150/HCTZ37.5). Compliance was assessed by pill counting, which was performed at the end of each treatment phase.

Clinical evaluation

Patients attended the clinic between 07:00 and 09:00 without taking their medication. The clinic sitting and standing BPs were measured electronically using the OMRON monitor model HEM-705CP (Omron Industrial Automation, USA) with appropriate cuffs. Three BP measurements were made in the nondominant arm at 2 min intervals after 10 min of rest in the sitting position with the arm supported at heart level by an armrest. Twenty-four hour ABP was measured at 20 min intervals during the daytime, and at 30 min intervals during the nighttime using a Spacelabs monitor (model 90207; Spacelabs Healthcare, USA). ABP monitoring (ABPM) was performed four times on a working weekday during the study, at the end of the washout period and at the end of each six-week treatment period. Accuracy of the ABP monitor was validated as previously described (8). The ABP readings had to meet satisfactory criteria, which were defined as a monitoring period of at least 24 h with at least one valid reading per hour and at least 75% of valid readings.

Adverse events were investigated from spontaneously reported complaints and from direct nonleading questioning at the end of the washout period, as well as at each visit during the active treatment phase, and were graded as mild, moderate or severe in intensity. Metabolic parameters, including serum glucose, HbA1c, serum creatinine, uric acid and electrolytes, were measured during fasting and evaluated at baseline, before and at the end of the randomized period.

Statistical analysis

Mean changes from week 12 to week 18 in ambulatory MDSBP were compared between treatment groups as the primary end point using data from 24 h ABPM. Treatment differences were evaluated using ANOVA considering an ‘all-patient treated last-observation carried-forward’ approach. This was performed using SPSS PROC GLM (SPSS Inc, USA) Type III sums of squares and least square means. The ANOVA model included treatment group as a factor. The difference between baseline (week 0) and postdose values was evaluated at the end of the three treatment level periods for each study group using a one-sample t test. The between-week comparisons were evaluated using ANOVA. The ANOVA model included weeks and patients as factors. The assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test and Levene’s test, respectively. If the assumption of homogeneity of variance appeared to be violated, ANOVA of the log-transformed data was performed. If the homogeneity of variance could not be achieved using a log transformation, then a nonparametric approach was used. Proportions of patients who reached goal ambulatory MDSBP (lower than 130 mmHg) and DBP (lower than 80 mmHg) were compared between the treatment groups using Fisher’s exact test. Proportions of patients with adverse clinical and laboratory experiences were compared between the treatment groups using Fisher’s exact test. The clinical and laboratory safety measurements were compared between treatment groups using ANOVA. Differences were considered to be significant at P<0.05.

Role of the funding source

The present study was funded by Merck Frosst Canada Ltd. The trial was designed by the principal investigator in consultation with the two other investigators of the recruiting centres. The team of the principal investigator was involved in data collection, site monitoring, data management and data analysis. However, analysis was performed by a statistician who was unaware of the treatments received by the patients. The results were sorted into group 1 and group 2. In addition, the principal investigator and his team wrote the manuscript and made the decision to submit for publication. All authors took responsibility for its content.

RESULTS

Demographics

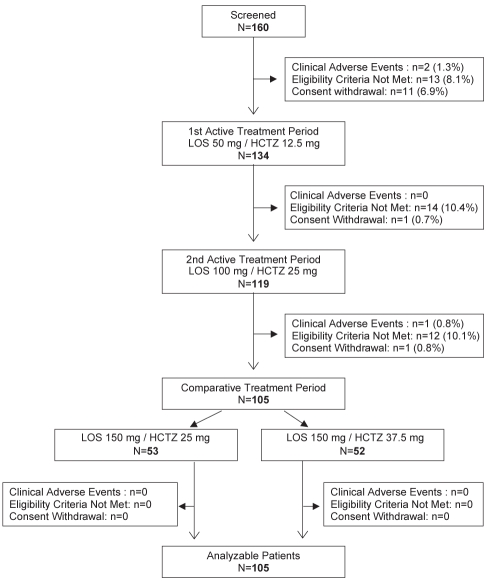

A total of 160 patients were screened for the study and included in the run-in period. At the end of the run-in period, 26 patients did not qualify for the active treatment period. Therefore, 134 patients entered the first active treatment phase of the study and received LOS50/HCTZ12.5 for six weeks. From these patients, 119 received LOS100/HCTZ25 during the second active treatment phase. At the end of this treatment phase, the 105 remaining patients with a mean clinic SBP of higher than 160 mmHg and an MDSBP of 130 mmHg or higher were randomized for the final six weeks of the study. The reasons for the withdrawal of the 55 nonrandomized patients are presented in Figure 2. Of the 105 remaining patients, 53 were allocated to receive LOS150/HCTZ25 (group 1) and 52 were allocated to receive LOS150/HCTZ37.5 (group 2). All of these patients completed the study and were deemed analyzable. The clinical characteristics included in the final analysis are presented in Table 1. Patients were mostly men and were approximately 65 years of age. Among the study’s population, 34 (32%) had type 2 diabetes mellitus and most had an HbA1c between 6% and 7%. Both treatment groups were comparable with regard to demographic characteristics such as age, sex, severity of hypertension, diabetes, clinic BP and ABP. During the trial, medication compliance was demonstrated to be adequate, with 100% of the patients having taken 95% of the tablets during each period and having an overall compliance of 98%.

Figure 2).

Causes of discontinuation before and after randomization. HCTZ Hydrochlorothiazide; LOS Losartan

TABLE 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study population included in the final analysis

| Characteristics |

Drug combination |

Total (n=105) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| L150/H25 (n=53) | L150/H37.5 (n=52) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 14 (26) | 19 (37) | 33 (31) |

| Male | 39 (74) | 33 (63) | 72 (69) |

| Age, years | 64.2±7.7 | 65.2±6.8 | 64.7±7.2 |

| ≥65, n (%) | 20 (38) | 25 (48) | 45 (43) |

| Weight, kg | 86.4±17.8 | 86.9±14.8 | 86.7±16.3 |

| Body mass index | 28.7±4.9 | 30.9±6.8 | 30.5±5.9 |

| ≥30 kg/m2, n (%) | 24 (45) | 22 (42) | 46 (44) |

| Diabetic status, n (%) | 16 (30) | 18 (35) | 34 (32) |

| Sitting SBP, mmHg | 170.8±14.5 | 171.1±12.2 | 170.9±13.4 |

| Sitting DBP, mmHg | 93.4±11.2 | 90.2±8.0 | 91.8±9.8 |

| Sitting heart rate, beats/min | 70.7±9.4 | 72.7±11.8 | 71.7±10.7 |

| Daytime ambulatory SBP, mmHg | 161.5±10.5 | 160.2±10.8 | 160.9±10.6 |

| Daytime ambulatory DBP, mmHg | 90.0±9.9 | 86.3±8.0 | 88.1±9.2 |

Data presented as mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated. DBP Diastolic blood pressure; H25 Hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg; H37.5 Hydrochlorothiazide 37.5 mg; L150 Losartan 150 mg; SBP Systolic blood pressure. P>0.05 for all between-group comparisons

Ambulatory and clinic BPs

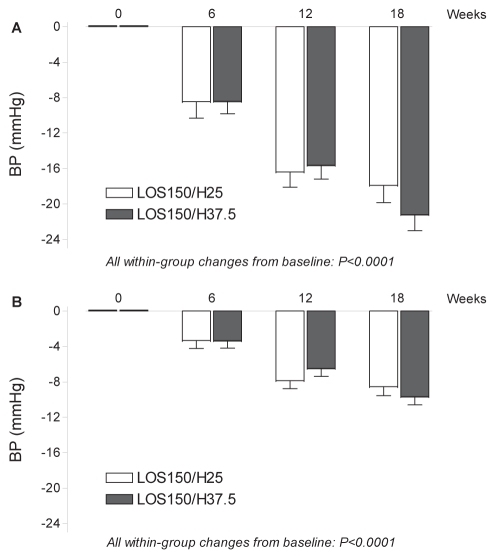

As illustrated in Figure 3, patients from group 1 randomly assigned to LOS150/HCTZ25 and patients from group 2 randomly assigned to LOS150/HCTZ37.5 achieved significant and similar MDSBP/mean daytime DBP (MDDBP) decreases after both six-week consecutive treatment periods with LOS50/HCTZ12.5 (−8.6/−3.4 mmHg and −8.5/−3.4 mmHg, respectively) and LOS100/HCTZ25 (−16.5/−8.0 mmHg and −15.7/−6.6 mmHg, respectively).

Figure 3).

Mean changes from baseline in mean daytime ambulatory systolic (A) and diastolic (B) blood pressure (BP) per study period, with 95% CIs. H25 Hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg; H37.5 Hydrochlorothiazide 37.5 mg; LOS150 Losartan 150 mg

Mean (± SD) BP reductions in the different periods of the 24 h ambulatory period after treatment with LOS100/HCTZ25 (baseline) are summarized in Table 2. The BP reductions were statistically significant but not different between groups. Reduction in MDSBP at week 18 revealed that group 2 (LOS150/HCTZ37.5) achieved a significant additional BP decrease of 5.5 mmHg (144.5 mmHg versus 139.0 mmHg, P<0.0001) compared with LOS100/HCTZ25, while patients from group 1 (LOS150/HCTZ25) experienced a nonsignificant additional BP decrease of 1.1 mmHg (145.0 mmHg versus 143.9 mmHg, P=0.335) compared with LOS100/HCTZ25. As illustrated in Figure 3, the mean treatment difference of MDSBP (primary end point) in favour of group 2 was −4.4 mmHg (P=0.011). The same pattern was observed for MDDBP with an additional and significant BP decrease of −3.2 mmHg in group 2 (79.7 mmHg versus 76.5 mmHg, P<0.0001), but a nonsignificant additional BP decrease of −0.7 mmHg in group 1 (82.0 mmHg versus 81.3 mmHg, P=0.325). The mean treatment difference (−2.5 mmHg) in MDDBP between group 2 and group 1 was statistically significant (P=0.013). Significant treatment differences in favour of group 2 were also present for both systolic (−3.3 mmHg; P=0.03) and diastolic (−2.19 mmHg; P=0.016) mean 24 h ABP. There were nonsignificant additional reductions in favour of group 2 for both systolic (−3.80 mmHg versus −2.85 mmHg, P=0.62) and diastolic (−2.56 mmHg versus −1.02 mmHg, P=0.21) nighttime ABP, with nonsignificant between-group differences for systolic/diastolic (−0.95/−1.55 mmHg) 24 h ABPs.

TABLE 2.

Decreases in clinic and ambulatory blood pressures (BPs) from enrollment to baseline and after six weeks of randomized therapy in groups 1 and 2

|

LOS 150 mg/HCTZ 25 mg (group 1) |

LOS 150 mg/HCTZ 37.5 mg (group 2) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrollment | Baseline week 12 | Treatment week 18 | Enrollment | Baseline week 12 | Treatment week 18 | |

| MDABP | ||||||

| Systolic | 161.5±10.6 | 145.0±10.3* (−16.5) | 143.9±12.8 (−17.6) | 160.3±10.8 | 144.5±9.6* (−15.8) | 139.0±12.0†‡ (−21.3) |

| Diastolic | 90.0±9.9 | 82.0±9.1* (−8.0) | 81.3±10.5 (−8.7) | 86.3±8.0 | 79.7±8.2* (−6.6) | 76.5±9.1†‡ (−9.8) |

| M24ABP | ||||||

| Systolic | 156.8±11.0 | 141.1±10.1* (−15.7) | 139.4±12.4 (−17.4) | 155.1±10.5 | 139.8±10.1* (−15.3) | 134.8±11.6†‡ (−20.3) |

| Diastolic | 86.3±9.2 | 78.7±8.4* (−7.6) | 77.9±9.7 (−8.4) | 82.8±7.9 | 76.3±7.9* (−6.5) | 73.3±8.6†‡ (−9.5) |

| MNABP | ||||||

| Systolic | 144.8±14.9 | 131.2±12.1* (−13.6) | 128.4±14.3§ (−16.4) | 142.5±14.0 | 128.4±14.1* (−14.1) | 124.7±13.9§ (−17.8) |

| Diastolic | 76.9±8.8 | 70.5±8.1* (−6.4) | 69.5±9.5 (−7.4) | 74.0±9.1 | 68.0±8.7* (−6.0) | 65.5±9.0¶ (−8.5) |

| Clinic BP | ||||||

| Systolic | 170.8±14.5 | 152.7±20.4* (−18.1) | 149.7±19.5 (−21.1) | 171.1±12.2 | 150.8±16.9* (−20.3) | 144.2±14.7¶ (−26.9) |

| Diastolic | 93.4±11.1 | 88.8±11.6* (−4.6) | 86.9±10.9 (−6.5) | 90.2±8.0 | 85.2±9.7* (−5.0) | 82.3±9.5 (−7.9) |

Data presented as mean ± SD. Data in parentheses show the reduction in BP from enrollment to baseline and after six weeks of treatment.

P<0.0001, results from baseline compared with enrollment;

P<0.05, group 2 versus group 1 at week 18, compared with baseline;

P<0.0001 compared with baseline;

P<0.05 compared with baseline;

P<0.01 compared with baseline. HCTZ Hydrochlorothiazide; LOS Losartan; M24ABP Mean 24 h ambulatory BP; MDABP Mean daytime ambulatory BP; MNABP Mean nighttime ambulatory BP

The efficacy of study treatments on clinic SBP and DBP is also presented in Table 2. Treatment with LOS 100 mg/HCTZ 25 mg provided significant and similar decreases in SBP and DBP in both groups. Six weeks later, patients in the LOS 150 mg/HCTZ 37.5 mg group experienced significant additional decreases in BP compared with LOS100/HCTZ25 for both clinic SBP (−6.58 mmHg; P=0.002) and DBP (−2.95 mmHg; P=0.001). In contrast, patients in the LOS150/HCTZ25 group did not demonstrate additional BP decreases in both clinic SBP and DBP versus baseline BP (−2.97/−1.94 mmHg; P value nonsignificant). However, the additional decreases in BP in favour of group 2 for SBP (−3.61 mmHg, P=0.18) and DBP (−1.01 mmHg, P=0.44) were also nonsignificant.

Attaining goal BP

At week 18, the goal daytime MDSBP of lower than 130 mmHg was not statistically significantly greater in group 2 (LOS150/HCTZ37.5) compared with patients in group 1 (25% versus 17%; P=0.313). However, the percentage of patients who attained a goal MDDBP of lower than 80 mmHg was significantly different in favour of group 2 (65.4% versus 43.4%; P=0.024).

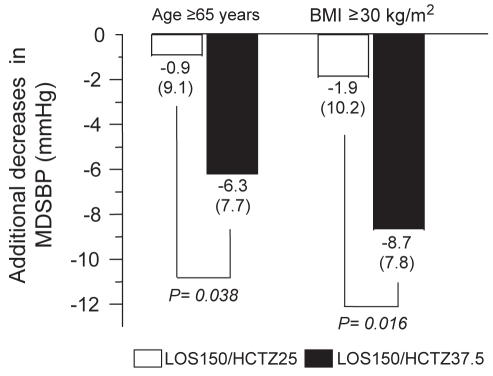

Subgroup analyses

Determinants of BP response are included in Figure 4. Mean reductions from baseline in MDSBP at week 18 were significantly greater in the LOS150/HCTZ37.5 arm than in the LOS150/HCTZ25 arm in patients 65 years of age and older, and in patients with a body mass index (BMI) of greater than 30 kg/m2. Regarding the patients with diabetes, a post hoc analysis showed a trend toward a more pronounced reduction in MDSBP with the LOS150/HCTZ37.5 dose versus the LOS150/HCTZ25 dose (−3.8 mmHg versus −2.1 mmHg, respectively).

Figure 4).

Additional decreases in mean (± SD) daytime systolic blood pressure (MDSBP) produced by losartan 150 mg/hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg (LOS150/HCTZ25) and losartan 150 mg/hydrochlorothiazide 37.5 mg (LOS150/HCTZ37.5) for elderly (65 years of age or older) and obese (body mass index [BMI] 30 kg/m2 or older) patient subgroups

Safety of study treatments

The effects of randomized treatments from baseline (LOS100/HCTZ25) on different metabolic parameters are summarized in Table 3. Overall, no significant alterations in these parameters were induced by any of the randomized treatments. The proportion of patients reporting clinical adverse experiences was not statistically different between group 1 (n=27; 50.9%) and group 2 (n=30; 50.7%). Likewise, the proportion of clinical adverse experiences possibly, probably or definitely related to the study drugs were similar between group 1 (n=17; 32.1%) and group 2 (n=17; 32.7%). Those events were of mild (n=22) to moderate (n=12) intensity, and were generally related to headache (n=7), dizziness (n=6) and fatigue (n=5). Two patients receiving active treatment experienced a serious clinical adverse event before random assignment. One patient had gynecological problems when treated with LOS50/HCTZ12.5, while the other patient on LOS100/HCTZ25 was hospitalized for breast cancer. These events were not related to study medication, although patient withdrawal was required in both cases.

TABLE 3.

Effects of treatments on metabolic parameters

| Treatment |

Drug combination |

|

|---|---|---|

| L150/H25 (n=53) | L150/H37.5 (n=52) | |

| Glucose, mmol/L | ||

| Week 12 | 6.8±2.4 | 6.8±2.2 |

| Week 18 | 6.6±2.1 | 6.7±2.0 |

| Glycated hemoglobin, % | ||

| Week 12 | 6.00±1.00 | 6.00±1.00 |

| Week 18 | 6.00±1.00 | 6.00±1.00 |

| Creatinine, mmol/L | ||

| Week 12 | 94.4±21.0 | 86.9±17.3 |

| Week 18 | 98.9±28.5 | 89.6±18.4 |

| Potassium, mmol/L | ||

| Week 12 | 4.21±0.43 | 4.18±0.41 |

| Week 18 | 4.23±0.39 | 4.19±0.40 |

| Sodium, mmol/L | ||

| Week 12 | 139.7±2.7 | 139.2±2.4 |

| Week 18 | 139.7±4.6 | 138.8±2.9 |

| Chloride, mmol/L | ||

| Week 12 | 98.7±3.2 | 98.6±2.4 |

| Week 18 | 99.1±3.0 | 98.0±4.6 |

| Uric acid, μmol/L | ||

| Week 12 | 358.0±79.5 | 352.7±66.4 |

| Week 18 | 347.8±70.3 | 356.9±73.7 |

Data presented as mean ± SD. P>0.05 for all comparisons. H25 Hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg; H37.5 Hydrochlorothiazide 37.5 mg; L150 Losartan 150 mg

DISCUSSION

The present study determined the changes in BP on a standard dose of LOS/HCTZ, and compared the antihypertensive efficacy and tolerability of increasing only the dose of LOS (LOS150/HCTZ25) with increasing the doses of both LOS and HCTZ simultaneously (LOS150/HCTZ37.5). Ambulatory MDSBP was chosen because after 50 years of age, SBP is predominant and more difficult to control (3). In addition, most of these patients have lower than normal DBP together with high pulse pressure. Furthermore, mean daytime BP (135/85 mmHg or higher) is now the criterion for the diagnosis of hypertension based on ABPM (9).

The ABPM data from the present study not only showed that LOS100/HCTZ25 decreases BP, but demonstrated that the LOS150/HCTZ37.5 combination was significantly more effective than LOS150/HCTZ25 in reducing MDSBP and MDDBP, as well as mean 24 h systolic and diastolic ABP. The percentage of patients reaching the goal MDSBP (lower than 130 mmHg) was not statistically significantly different in patients treated with LOS150/HCTZ37.5. The percentage of patients attaining the MDDBP target (lower than 80 mmHg) was, however, significantly greater with LOS150/HCTZ37.5.

Of note, our results are comparable with those achieved in our previous study (5), showing a greater dose-dependent reduction in ambulatory SBP and DBP by increasing the dose of both an ARB and HCTZ. These data provide a substantial argument against the fact that the greater benefit observed with the LOS150/HCTZ37.5 combination might solely be due to increasing the dose of HCTZ from 25 mg to 37.5 mg (5). Indeed, increasing HCTZ monotherapy from 12.5 mg to 25 mg in patients with systolic hypertension established by ABPM has not resulted in any significantly greater reduction in both systolic and diastolic ABP (5). Our results, which revealed a greater reduction in BP when increasing both antihypertensive agents, are not in agreement with the results of Izzo et al (10), who showed a greater reduction in SBP when increasing only HCTZ from 25 mg to a dose of 50 mg combined with olmesartan 40 mg. However, the design of their study differs from ours because there was no ABP evaluation and it is possible that nontruly hypertensive patients were included. Their results are also different from those of the present study. Indeed, doubling the HCTZ dose from 25 mg to 50 mg provided a mean additional reduction in clinic SBP of only 3.6 mmHg compared with an additional and meaningful decrease in MDSBP of 4.4 mmHg in our study, suggesting a much greater reduction in SBP when increasing the dosage of both HCTZ and the ARB. The greater BP reductions when increasing the dosages of both the diuretic and the ARB as seen in the present study can most likely be attributed to the complementary mechanisms of action of HCTZ with agents that block the RAAS. Increasing the dose of HCTZ activates the RAAS, leading to enhanced responsiveness to angiotensin receptor blockade (11,12).

Our study using LOS150/HCTZ37.5 and showing an additional BP reduction of 4.4/2.5 mmHg in patients with severe and uncontrolled hypertension may be of clinical relevance mostly in elderly patients. Indeed, they represent the majority of patients with refractory systolic hypertension (13), even when managed with two or more antihypertensive agents (14,15). Furthermore, the increased BP reduction seen with higher dosages of both HCTZ and the ARB may preclude the need to add a third (16) or even a fourth antihypertensive agent, and may also normalize BP in many patients who are resistant and already treated with three antihypertensive agents. The reduction and control of SBP is of importance because it is a strong variable in mediating target organ effects (17–19). The importance of significant differences in BP control, as in our study, has been demonstrated in the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) (20) and the Valsartan Antihypertensive Long-term Use Evaluation (VALUE) trial (21). Indeed, a sustained reduction in BP between two treatments maintained over time was associated with reduction in the risk of cardiovascular events in these studies. Of note, these studies have not used ABPM for BP inclusion and evaluation. Consequently, this may render our results using ABPM more powerful because of the superiority of ABPM over clinic BP evaluations (22). Another major advantage of a higher fixed-dose combination may be the reduction in the number of pills, which could decrease the psychological burden of being sicker. However, this would only be possible if such combinations are commercially available in the future.

Higher doses of diuretics, such as doses of HCTZ or chlorthalidone over 50 mg (23), have been shown to induce metabolic changes that are usually prevented by increasing the dose of RAAS inhibitors. This may be explained in part by these drugs offsetting some of the potential metabolic effects of HCTZ (24,25). One of the most important metabolic disorders observed with HCTZ is the decrease in kalemia (25,26). The incremental mean reductions in both SBP and DBP with higher than average doses of LOS and HCTZ achieved in the present study without adverse metabolic events confirm that increasing HCTZ and an inhibitor of the RAAS together helps to offset the metabolic effects associated with higher doses of diuretic therapy. Our results, which showed no deleterious effects on glucose and HbA1c, are in contrast with those of Bakris et al (27), which showed that LOS fails to protect against worsening of glycemic control by diuretics. However, their population was different because every one of their 220 patients had glucose intolerance, while only 34 (32%) of our patients had proven type 2 diabetes mellitus. In addition, most of the diabetic patients had normal HbA1c at the beginning of the study and there was no overall change at the end of the trial. In our study, 32% of patients had proven and treated type 2 diabetes mellitus. Otherwise, a glucose tolerance test was not performed in nondiabetic patients. However, it is important to mention that treatment for six weeks may be too short to detect major, significant metabolic changes usually seen in long-term studies. Finally, our primary end point is quite different because it deals with the changes of ambulatory SBP versus the change from baseline of an oral glucose tolerance test. In the present study, possible drug-related adverse events occurred in fewer than 20% of subjects. No dose-response relationship was observed.

The mean reductions in MDSBP favoured LOS150/HCTZ37.5 in patients 65 years of age or older and in those with a BMI of greater than 30 kg/m2. As mentioned earlier, because these patients are at substantial risk for developing organ damage, achievement of goal BP in these populations may be particularly relevant.

Strengths and limitations

The major strength of the present study was the use of ABP as one of the inclusion criteria (MDSBP of 135 mmHg or higher), and for randomization and drug titration. ABPM and mean daytime BP provided an accurate assessment of patients’ hypertension (28), and enabled clinicians to exclude subjects with white coat hypertension (29,30).

The limitations of the present study should be noted. First, a PROBE design was used. Patients’ and pharmacists’ awareness of treatment assignment can consequently be considered as a limitation of the study’s design, although potential investigator bias was minimized because the primary end point data were gathered in a blinded manner with ABPM. A meta-analysis found the PROBE design to be valid for assessing anti-hypertensive efficacy based on blinded ABPM measurements compared with a double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial (6). Second, by only including patients with established hypertension measured by ABPM, the present study may have introduced potential differences between our population and the patients with hypertension in general. Moreover, only including patients with confirmed ambulatory hypertension (MDSBP of 135 mmHg or higher), as in the present trial, permits a more accurate assessment of patients’ hypertension and avoids the dilution of the antihypertensive effects of study drugs produced by the inclusion of patients with white coat hypertension in the trials (31). Third, although subgroup analyses were prespecified, the sample sizes of patients older than 65 years of age and of patients with elevated BMI were relatively small, representing 43% and 44%, respectively, of the efficacy cohort. In addition, of the 105 patients randomized, 30% in the LOS150/HCTZ25 arm and 35% in the LOS150/HCTZ37.5 arm had diabetes. Although there was a trend toward a better reduction in MDSBP with the higher dose in these patients, such a conclusion is not strong because it was derived from a post hoc analysis.

Finally, we decided a priori not to include a group receiving the higher dose of HCTZ along with the lower dose of LOS. This decision was based on a previous study (5) that showed no additional BP decrease when increasing the thiazide dose.

CONCLUSION

Although the proportion of patients achieving the MDSBP target was not statistically different in the two groups, the present study of patients with uncontrolled systolic hypertension using ABPM demonstrated that a combination of LOS150/HCTZ37.5 provides reductions in systolic and diastolic ABP that are superior to those achieved with usual doses of LOS100/HCTZ25 and with those of LOS150/HCTZ25. This confirms the advantages of simultaneously increasing the dose of both the ARB and HCTZ. Of clinical relevance, the higher dose combination of LOS150/HCTZ37.5 did not induce untoward metabolic effects. Thus, the results of the present study suggest that an LOS150/HCTZ37.5 combination represents an effective strategy that may help in the management of patients with uncontrolled and resistant systolic hypertension who require several antihypertensive agents to control their hypertension.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE: This research was supported by a grant from Merck Frosst Canada Ltd and its affiliates, and by Fondation Hypertension Laurier, Québec, Québec.

REFERENCES

- 1.Leenen FH, Dumais J, McInnis NH, et al. Results of the Ontario survey on the prevalence and control of hypertension. CMAJ. 2008;178:1441–9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McInnis NH, Fodor G, Moy Lum-Kwong M, Leenen FH. Antihypertensive medication use and blood pressure control: A community-based cross-sectional survey (ON-BP) Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:1210–5. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hyman DJ, Pavlik VN. Characteristics of patients with uncontrolled hypertension in the United States. N Eng J Med. 2001;345:479–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mackay JH, Arcuri KE, Golberg AI, et al. Losartan and low dose hydrochlorothiazide in patients with essential hypertension. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of concomitant administration compared with individual components. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:278–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lacourcière Y, Poirier L. Antihypertensive effects of two fixed-dose combinations of losartan and hydrochlorothiazide versus hydrochlorothiazide monotherapy in subjects with ambulatory hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2003;16:1036–42. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2003.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith DH, Neutel JM, Lacourcière Y, Kempthorne-Rawson J. Prospective, randomized, open-label, blinded-endpoint (PROBE) designed trials yield the same results as double-blind, placebo-controlled trials with respect to ABPM measurements. J Hypertens. 2003;21:1291–8. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200307000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feldman RD, Zou GY, Vandervoort MK, et al. A simplified approach to the treatment of uncomplicated hypertension: A cluster randomized, controlled trial. Hypertension. 2009;53:646–53. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.123455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graettinger WF, Lipson JL, Cheung DG, Weber MA. Validation of portable noninvasive blood pressure monitoring devices: Comparisons with intra-arterial and sphygmomanometer measurements. Am Heart J. 1988;116:1155–60. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(88)90181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Padwal RS, Hemmelgarn BR, Khan NA, et al. Canadian Hypertension Education Program The 2009 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: Part 1 – blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25:279–86. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(09)70491-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Izzo JL, Neutel JM, Silfani T, et al. Titration of HCTZ to 50 mg daily in individuals with stage 2 systolic hypertension pretreated with an angiotensin receptor blocker. J Clin Hypertens. 2007;9:45–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2007.05714.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soffer BA, Wright JT, Jr, Pratt JH, Wiens B, Goldberg AI, Sweet CS. Effects of losartan on a background of hydrochlorothiazide in patients with hypertension. Hypertension. 1995;26:112–7. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.26.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azizi M, Chatellier G, Guyene TT, Murieta-Geoffroy D, Ménard J. Additive effects of combined angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II antagonism on blood pressure and renin release in sodium-depleted normotensives. Circulation. 1995;92:825–34. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.4.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perry HM, Jr, Bingham S, Horney A, et al. Antihypertensive efficacy of treatment regimens used in Veterans Administration hypertension clinics. Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents. Hypertension. 1998;31:771–9. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.3.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mancia G, Bombelli M, Lanzarotti A, et al. Systolic vs diastolic blood pressure control in the hypertensive patients of the PAMELA population. Pressioni Arteriose Monitorate E Loro Associazioni. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:582–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.5.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swales JD. Current clinical practice in hypertension: The EISBERG (Evaluation and Interventions for Systolic Blood pressure Elevation-Regional and Global) project. Am Heart J. 1999;138:231–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70315-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calhoun DA, Lacourcière Y, Chiang YT, Glazer RD. Triple antihypertensive therapy with amlodipine, valsartan, and hydrochlorothiazide: A randomized clinical trial. Hypertension. 2009;54:32–9. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.131300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacMahon S, Peto R, Cutler J, et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 1, Prolonged differences in blood pressure: Prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet. 1990;335:765–74. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90878-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Collins R, Peto R, MacMahon S, et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 2, Short-term reductions in blood pressure: Overview of randomised drug trials in their epidemiological context. Lancet. 1990;335:827–38. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90944-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flack JM, Neaton J, Grimm R, Jr, et al. Blood pressure and mortality among men with prior myocardial infarction. Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research Group. Circulation. 1995;92:2437–45. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.9.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) JAMA. 2002;288:2981–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, Weber M, et al. VALUE trial group Outcomes in hypertensive patients at high cardiovascular risk treated with regimens based on valsartan or amlodipine: The VALUE randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363:2022–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16451-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith DH, Dubiel R, Jones M. Use of 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring to assess antihypertensive efficacy: A comparison of olmesartan medoxomil, losartan potassium, valsartan, and irbesartan. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2005;5:41–50. doi: 10.2165/00129784-200505010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bakris GL, Weir MR, Sowers JR. Therapeutic challenges in the obese diabetic patient with hypertension. Am J Med. 1996;101(3A):33S–46S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neutel JM. Metabolic manifestations of low-dose diuretics. Am J Med. 1996;101(3A):71S–82S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00270-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papademetriou V. Diuretics in hypertension: Clinical experiences. Eur Heart J. 1992;13(Suppl G):92–5. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/13.suppl_g.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Unwin RJ, Ligueros M, Shackleton CR, Wilcox CS. Diuretics in the management of hypertension. In: Laragh JH, Breneer BM, editors. Hypertension, Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management. 2nd edn. New York: Raven Press Ltd; 1995. pp. 2785–99. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bakris G, Molitch M, Hewkin A, et al. Difference in glucose tolerance between fixed-dose antihypertensive drug combination in people with metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2592–7. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clement DL, De Buyzere ML, De Bacquer DA, et al. Office versus Ambulatory Pressure Study Investigators. Prognostic value of ambulatory blood-pressure recordings in patients with treated hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2407–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veglio F, Rabbia F, Riva P, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and clinical characteristics of the true and white-coat resistant hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2001;23:203–11. doi: 10.1081/ceh-100102660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gibbs CR, Murray S, Beevers DG. The clinical value of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Heart. 1998;79:115–7. doi: 10.1136/hrt.79.2.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lacourcière Y, Poirier L, Dion D, Provencher P. Antihypertensive effect of isradipine administered once or twice daily on ambulatory blood pressure. Am J Cardiol. 1990;65:467–72. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90812-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]