Introduction

Dog allergy is a public health burden1 highly associated with both asthma and allergic rhinitis.2 Contributing to this disease burden is the presence of around 53 million domestic dogs in the United States residing in approximately 33% of US homes.3 The magnitude of this problem makes it important to identify factors related to the accumulation of the major dog allergen Canis familiaris 1 (Can f 1) in homes.

Several studies evaluating dog allergen levels in homes were identified from the literature; however, these studies had important limitations.4–10 Some publications presented dog allergen levels4–6 or “clinically relevant” thresholds7 where the authors stratified households by dog ownership, but they did not take into account whether the dogs could have been kept exclusively outdoors. Other publications did not present findings separately for homes with dogs,8–10 and none addressed whether the dog was allowed in the room from which the environmental sample was collected. The aim of our analyses was to identify environmental factors and dog-specific characteristics that influence the accumulation of Can f 1 in homes, specifically in children’s bedrooms.

Methods

The methodology for the Wayne County Health, Environment, Allergy, & Asthma Longitudinal Study (WHEALS), a population-based birth cohort, has been described fully elsewhere.11 Briefly, pregnant women who resided in urban and suburban Detroit areas were recruited during a second or third trimester prenatal visit to a Henry Ford Health System (HFHS) obstetrics clinic. Interviews were conducted at recruitment and at a one month post-partum home visit. Written consent was given by participants at the time of study recruitment.

Dust samples were collected from the baby’s bedroom floor at one month post-partum and processed thereafter using a standardized protocol.11–12 Dust was obtained by placing a closely fitting unbleached muslin collection sock on the nozzle of a vacuum and the nozzle was used to vacuum a 1m2 area of the floor along the side of the infant’s bed for two minutes. The collection sock, complete with dust specimen, was placed in a sterile plastic bag, frozen to −80 C and shipped to our collaborating laboratory at the Medical College of Georgia. Dust was analyzed by emptying the dust sample from the collection sock into a funnel fitted with a mesh filter (pore size: 292 nm) connected to a 10×75mm sample tube. The tube and its contents were then shaken on an orbital shaker for one hour allowing the crude dust sample to separate into coarse debris and fine dust. The filtered, fine dust was then weighed and extracted before being analyzed for Can f 1. The dust sample was assayed using standard monoclonal antibody assays (Indoor Biotechnologies, Ltd., Charlottesville, VA) with a lowest detectable limit of 0.50 nanograms of allergen per milliliter of saline. Samples with undetectable values were assigned half the value of the lowest detectable limit, or 0.25 ng/mL. Results were converted to micrograms of allergen per gram of dust (mcg/g) to make them comparable to the literature. Additional dust samples were collected from the home; however, due to financial constraints, only dust from the floor of the baby’s bedroom was analyzed for Can f 1.

Dog characteristics were based on maternal report during the personal interview in her home conducted one month post-delivery. Women were asked how many dogs were living in the home, and the following data were collected for each dog: breed or breeds, sex, reproductive status (neutered or spayed versus not), weight, number of months the dog lived in the home, average time indoors daily and whether the dog was allowed in the baby’s bedroom. Sex was determined by asking if the dog was male or female, and altered status clarified by asking whether the dog had been spayed or neutered. Flooring characteristics were collected by trained field staff at the time of the dust sample collection and urban/suburban classification was based on city of residence at the time of the collection (all those living in Detroit were considered to be living in an “urban” environment). If a dog was kept indoors one or more hours per day on average, that home had an “indoor” dog while dog-keeping households where dogs were not kept indoors were categorized as having “outdoor” dogs. In homes where multiple dogs were kept and allowed inside the home, the home was categorized as “dogs allowed in the baby’s bedroom” if any dog was allowed in the baby’s bedroom.

Homes with one dog were selected for additional dog characteristic analyses. These analyses included characterization of the dog based upon coat type (short, medium, long, thick, or wire), dander level (low, regular, or high), body hair status of dog (present or absent), whether the dog was single or double coated, and shedding amount (little, average, seasonal, or constant). Dogs were assigned to these categories based on their breed standards.13–14 Non-purebred dogs were not necessarily excluded from analyses. If a dog was listed as two separate breeds, the breed standards for these two types of dogs were compared and if any categorization was common between them, the shared trait was assigned to the dog in question. For dogs of more than two breeds or for dogs of unknown breeds, no values were assigned.

As Can f 1 was not normally distributed, geometric means (GM) were used to summarize the data. Spearman correlations were used to assess association of Can f 1 and various dog characteristics such as time indoors. For two-group comparisons, Wilcoxon rank sum statistics were calculated. For comparisons of groups with three or more levels, Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for nominal variables and Jonckheere-Terpstra tests for trend for ordinal variables. For multivariable analyses, variables with a p<0.15 in univariate analyses were entered into the regression model. Can f 1 was log-transformed prior to inclusion in the regression models due to skewness of the data. This research was approved by the HFHS IRB.

Results

There were 992 families with dog allergen data available for the 1 month home visit. Of these 992, 384 (38.7%) had “non-detectable” Can f 1 levels. As shown in Table 1, these 384 homes are largely, but not exclusively, without dogs. Most homes with dogs (91.3%) and half of all homes without dogs (50.9%) had detectable Can f 1 levels in the home.

Table 1.

Detection rates of Can f 1 by household dog composition1, WHEALS cohort, Detroit, MI

| Number of dogs in household at 1 month interview | Detectable | Non-Detectable | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (row%) | n (row%) | n (col%) | |

| 0 | 376 (50.9%) | 362 (49.1%) | 738 (74.4%) |

| 1 | 175 (91.6%) | 16 (8.4%) | 191 (19.3%) |

| 2 | 45 (90.0%) | 5 (10.0%) | 50 (5.0%) |

| 3 | 12 (92.3%) | 1 (7.7%) | 13 (1.3%) |

| Total | 608 (61.3%) | 384 (38.7%) | 992 (100%) |

Mother reported

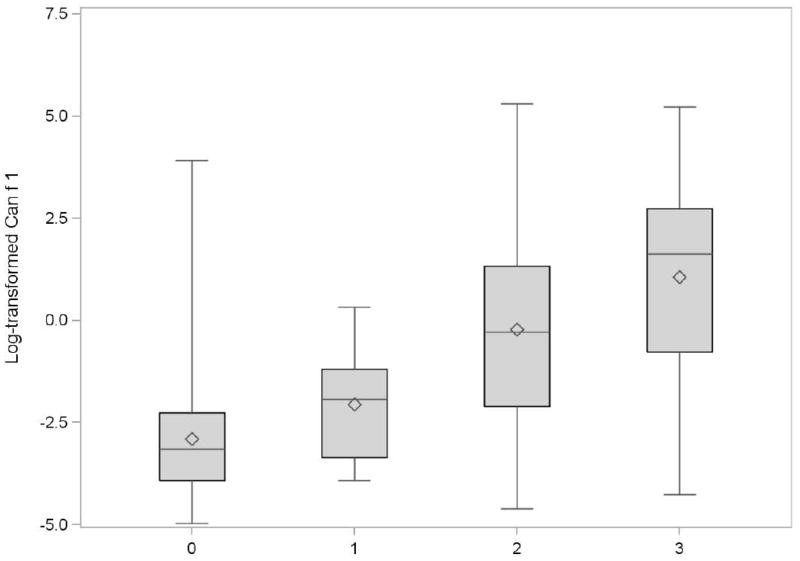

Table 2 provides Can f 1 levels by household dog ownership. Households with dogs were significantly more likely to have detectable Can f 1 levels as well as higher levels of dog allergen in the home as compared to households without dogs (both p<0.001). Homes with exclusively outdoor dogs with detectable allergen had significantly higher Can f 1 levels than homes without any dogs (p=0.004), but significantly lower levels than homes with indoor dogs (p<0.001); however, the percentage of homes with detectable Can f 1 levels was significantly different only between homes with indoor versus outdoor dogs. Figure 1 shows a significant trend of increasing dog allergen level associated with increased dog presence in the home over four levels of dog ownership (no dog, outdoor dog(s) only, indoor dog(s) not allowed in the baby’s bedroom and indoor dog(s) allowed in the baby’s bedroom) (test for trend p<0.001). One dog homes where the dog was allowed indoors were further assessed in Table 2. Homes where the dog was allowed run of the house, allowed in the mother’s bedroom or allowed in the baby’s bedroom all had significantly higher levels of Can f 1 than homes where they were not (p=0.003, p=0.001, p=0.001 respectively).

Table 2.

| N | n (%) non-detectable | Chi-square p-value |

Homes with Detectable Can f 1 only |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Can f 1 Geometric mean (95% CI) | p-value | ||||

| Any dog in home | <0.001 | <0.0013 | ||||

| Yes | 254 | 22 (8.7%) | 232 | 1.24 (0.91, 1.71) | ||

| No | 738 | 362 (49.1%) | 376 | 0.055 (0.048, 0.063) | ||

| Outdoor only dog homes4 | 0.33 | 0.0043 | ||||

| Yes | 30 | 12 (40.0%) | 18 | 0.13 (0.07, 0.23) | ||

| No dog | 738 | 362 (49.1%) | 376 | 0.055 (0.048, 0.063) | ||

| Dog homes4 | <0.001 | <0.0013 | ||||

| Outdoors only | 30 | 12 (40.0%) | 18 | 0.13 (0.07, 0.23) | ||

| Indoors any hours | 219 | 10 (4.6%) | 209 | 1.59 (1.14, 2.21) | ||

| Number of dogs | 0.91 | 0.825 | ||||

| 1 | 191 | 16 (8.4%) | 175 | 1.21 (0.85, 1.74) | ||

| 2 | 50 | 5 (10.0%) | 45 | 1.23 (0.56, 2.69) | ||

| 3 | 13 | 1 (7.7%) | 12 | 1.86 (0.35, 9.99) | ||

| In one dog homes where dog allowed indoors | ||||||

| Hours dog indoors | 0.99 | 0.203 | ||||

| ≤12 hours | 31 | 2 (6.4%) | 29 | 0.82 (0.32, 2.07) | ||

| >12 hours | 142 | 8 (5.6%) | 134 | 1.60 (1.06, 2.42) | ||

| Allowed run of house | 0.18 | 0.0033 | ||||

| Yes | 120 | 5 (4.2%) | 115 | 2.02 (1.33, 3.07) | ||

| No | 53 | 5 (9.4%) | 48 | 0.61 (0.29, 1.29) | ||

| Allowed on furniture | 0.21 | 0.083 | ||||

| Yes | 70 | 2 (2.9%) | 68 | 2.11 (1.20, 3.72) | ||

| No | 103 | 8 (7.8%) | 95 | 1.07 (0.65, 1.76) | ||

| Allowed in mom’s bedroom | 0.74 | 0.0013 | ||||

| Yes | 102 | 5 (4.9%) | 97 | 2.36 (1.46, 3.79) | ||

| No | 71 | 5 (7.0%) | 66 | 0.68 (0.38, 1.20) | ||

| Allowed on mom’s bed | 0.06 | 0.0333 | ||||

| Yes | 48 | 0 (0.0%) | 48 | 2.66 (1.36, 5.22) | ||

| No | 125 | 10 (8.0%) | 115 | 1.09 (0.70, 1.71) | ||

| Allowed in baby’s bedroom | 0.95 | 0.0013 | ||||

| Yes | 88 | 5 (5.7%) | 83 | 2.56 (1.50, 4.37) | ||

| No | 85 | 5 (5.9%) | 80 | 0.77 (0.47, 1.27) | ||

| Allowed on baby’s bed | 0.99 | 0.743 | ||||

| Yes | 6 | 0 (0.0%) | 6 | 1.94 (0.13, 29.4) | ||

| No | 167 | 10 (6.0%) | 157 | 1.41 (0.96, 2.06) | ||

All Can f 1 units are in mcg/g

Mother reported

Wilcoxon rank sum test

5 homes were excluded because they had both inside and outside dogs

Jonckheere-Terpstra test for trend

Figure 1.

Box plot of detectable Can f 1 levels* on baby’s bedroom floor by household dog ownership†, WHEALS cohort, Detroit, MI‡

0 = No dogs (N=376)

1 = Outdoor dog(s) only (N=18)

2 = Dog(s) allowed indoors, but not in the baby’s bedroom (N=109)

3 = Dog(s) allowed in the baby’s bedroom (N=105)

* All Can f 1 units are in mcg/g

† Mother reported

‡ Jonckheere-Terpstra test for trend, p<0.001

Spearman correlations for homes with dogs and detectable levels of Can f 1 are shown in Table 3. Total dog months (p=0.005) and total number of hours the dogs were indoors daily (p<0.001) were positively, although modestly correlated with dog allergen in the home (r=0.19 and r=0.30, respectively). Dog owners in urban environments tended to keep their dog indoors for a shorter duration of time daily than their suburban counterparts (Wilcoxon Rank Sum (WRS) test p=0.004, data not shown). One dog homes were further assessed. In homes where the dog was allowed indoors, only number of months the dog lived at the home (p=0.07) and dog weight in homes where the dog was not allowed in the baby’s bedroom (p=0.052) flirted with statistical significance.

Table 3.

Correlation of Can f 1 levels to dog and home characteristics among homes with dogs1 having detectable Can f 1 levels2, WHEALS cohort, Detroit, MI

| n | Spearman correlation (r) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of dogs | 232 | 0.03 | 0.69 |

| Total dog weight3 | 230 | −0.03 | 0.70 |

| Total dog months | 232 | 0.19 | 0.005 |

| Total dog hours indoors | 232 | 0.30 | <0.001 |

|

In one dog homes where the dog was allowed indoors | |||

| Dog weight3 | 161 | 0.05 | 0.53 |

| Allowed in baby’s bedroom | 82 | 0.22 | 0.052 |

| Not allowed in baby’s bedroom | 79 | −0.14 | 0.21 |

| Dog months | 163 | 0.14 | 0.07 |

| Allowed in baby’s bedroom | 83 | 0.11 | 0.33 |

| Not allowed in baby’s bedroom | 80 | 0.14 | 0.23 |

| Dog hours indoors | 163 | 0.10 | 0.18 |

| Allowed in baby’s bedroom | 83 | −0.06 | 0.62 |

| Not allowed in baby’s bedroom | 80 | 0.11 | 0.35 |

Mother reported

All Can f 1 units are in mcg/g

Missing data

Table 4 addresses whether urban environment or flooring type at the site of sampling affected Can f 1 levels. Among homes with one or more inside dogs, higher levels of Can f 1 were found in suburban homes (GM 2.72 vs. 0.53, p<0.001) with a similar pattern evident when restricted to one dog homes, whether or not the dog was allowed in the room sampled. Flooring type was also assessed and as shown in Table 4, was not significantly related to Can f 1 levels in the home; although, the means for carpeted floors were consistently higher than those for smooth floors. Neither type of carpet (plush pile versus Berber) nor amount of bedroom carpeted (rug versus wall-to-wall carpet) were associated with Can f 1 levels in homes with indoor dogs where dogs were allowed in the baby’s bedroom (WRS test: type of carpet p=0.36, amount of carpet p=0.75; data not shown).

Table 4.

Can f 1 levels1 in homes with detectable levels only by residential characteristics, WHEALS cohort, Detroit, MI

| Any dogs in the home | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | GM2 | Yes Range | p-value3 | N | GM2 | No Range | p-value3 | |

| Environment | <0.001 | 0.97 | ||||||

| Suburban | 113 | 2.72 | 1.75 – 4.24 | 155 | 0.057 | 0.046 – 0.070 | ||

| Urban | 107 | 0.53 | 0.35 – 0.80 | 148 | 0.057 | 0.046 – 0.070 | ||

| Flooring type | 0.69 | 0.46 | ||||||

| Carpeted | 172 | 1.31 | 0.89 – 1.91 | 308 | 0.057 | 0.049 – 0.067 | ||

| Bare | 57 | 1.09 | 0.60 – 1.99 | 64 | 0.045 | 0.035 – 0.058 | ||

| 1 dog homes (homes with detectable levels only) where dog is ever allowed inside | ||||||||

| Dog allowed in baby’s bedroom | Dog not allowed in baby’s bedroom | |||||||

| N | GM2 | Range | p-value3 | N | GM2 | Range | p-value3 | |

| Environment | 0.08 | 0.02 | ||||||

| Suburban | 61 | 3.45 | 1.88 – 6.33 | 30 | 1.66 | 0.71 – 3.84 | ||

| Urban | 22 | 1.13 | 0.37 – 3.42 | 50 | 0.49 | 0.27 – 0.89 | ||

| Flooring type | 0.46 | 0.08 | ||||||

| Carpeted | 54 | 2.84 | 1.39 – 5.80 | 60 | 1.00 | 0.56 – 1.80 | ||

| Bare | 28 | 2.07 | 0.90 – 4.72 | 18 | 0.34 | 0.12 – 0.95 | ||

All Can f 1 units are in mcg/g

Geometric Mean

Wilcoxon rank sum test

Characteristics specific to dogs are shown in Table 5. No canine characteristic was significantly associated with Can f 1 levels in one dog homes with detectable levels of Can f 1 when the dog was allowed in the baby’s bedroom. In homes with detectable Can f 1 levels where their one dog was allowed indoors but not in the baby’s bedroom, only the dog’s altered status was significantly associated with Can f 1 levels, with spayed or neutered dogs having higher levels of Can f 1 than their unaltered counterparts (p<0.001).

Table 5.

| 1 dog homes (homes with detectable levels only) where dog is ever allowed inside |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dog allowed in baby’s bedroom | Dog not allowed in baby’s bedroom | |||||||

| N | GM3 | Range | p-value | N | GM3 | Range | p-value | |

| Dander level | 0.994 | 0.444 | ||||||

| Low | 5 | 2.58 | 0.05 – 130.2 | 5 | 1.77 | 0.22 – 14.5 | ||

| Regular | 44 | 2.40 | 1.18 – 4.88 | 53 | 0.54 | 0.30 – 0.97 | ||

| High | 7 | 2.41 | 0.31 – 18.5 | 6 | 0.66 | 0.03 – 13.7 | ||

| Shedding | 0.274 | 0.424 | ||||||

| Little | 12 | 2.09 | 0.38 – 11.3 | 12 | 1.99 | 0.55 – 7.21 | ||

| Average | 34 | 1.59 | 0.74 – 3.43 | 43 | 0.58 | 0.29 – 1.18 | ||

| Seasonal | 1 | 2.45 | --- | 5 | 0.57 | 0.07 – 4.47 | ||

| Constant | 8 | 9.32 | 1.04 – 83.8 | 5 | 0.42 | 0.02 – 11.2 | ||

| Single vs. double coat | 0.835 | 0.185 | ||||||

| Single | 5 | 2.56 | 0.05 – 130.2 | 6 | 1.91 | 0.39 – 9.50 | ||

| Double | 64 | 3.04 | 1.73 – 5.34 | 64 | 0.66 | 0.38 – 1.15 | ||

| Coat type | 0.094 | 0.414 | ||||||

| Short | 34 | 1.80 | 0.85 – 3.80 | 39 | 0.53 | 0.27 – 1.04 | ||

| Medium | 12 | 8.03 | 1.64 – 39.3 | 8 | 1.68 | 0.27 – 10.3 | ||

| Long | 8 | 0.53 | 0.08 – 3.59 | 6 | 2.95 | 0.19 – 45.8 | ||

| Thick | 0 | --- | --- | 3 | 0.49 | 0.004 – 56.5 | ||

| Wire | 1 | 3.72 | --- | 2 | 1.16 | 0.001 – 935.8 | ||

| All dogs | 0.385 | 0.715 | ||||||

| Female | 36 | 1.88 | 0.77 – 4.56 | 30 | 0.84 | 0.38 – 1.39 | ||

| Male | 47 | 3.26 | 1.66 – 6.38 | 50 | 0.73 | 0.37 – 1.94 | ||

| Altered status | 0.165 | <0.0015 | ||||||

| Fixed | 62 | 3.19 | 1.75 – 5.84 | 30 | 3.09 | 1.39 – 6.87 | ||

| Unaltered | 21 | 1.34 | 0.41 – 4.36 | 50 | 0.34 | 0.20 – 0.57 | ||

| Altered dogs only | 0.105 | 0.975 | ||||||

| Female | 30 | 1.89 | 0.74 – 4.81 | 13 | 3.02 | 0.85 – 10.7 | ||

| Male | 32 | 5.23 | 2.40 – 11.4 | 17 | 3.15 | 1.00 – 9.94 | ||

| Unaltered dogs only | 0.615 | 0.825 | ||||||

| Female | 6 | 1.82 | 0.05 – 69.0 | 17 | 0.32 | 0.12 – 0.82 | ||

| Male | 15 | 1.19 | 0.33 – 4.22 | 33 | 0.35 | 0.18 – 0.68 | ||

All Can f 1 units are in mcg/g

Not all characteristics are known for each dog, therefore there are missing data

Geometric Mean

Kruskal-Wallis test

Wilcoxon rank sum test

Multivariable analyses showed that, on average, in households with detectable Can f 1 levels where the dog was allowed indoors but not in the baby’s bedroom, only whether the dog was spayed or neutered was related to Can f 1 levels (p<0.001, data not shown). There were no factors in the multivariable analysis predictive of Can f 1 levels where the dog was allowed in the baby’s bedroom (all p>0.05, data not shown).

Discussion

Dog ownership was related to higher Can f 1 levels in the home. Even homeowners who kept their dogs outdoors had significantly higher levels of Can f 1 than did homes with no dogs. Increasing time of the dog in the home corresponded with increased levels of Can f 1. In homes with a single dog, we found that if the dog was allowed in the baby’s bedroom then that floor surface had higher Can f 1 levels compared to homes where the dog was allowed indoors, but not in the baby’s bedroom. Although Can f 1 levels did not differ significantly between carpeted and non-carpeted bedrooms, there was generally higher levels of allergen detected from carpeted samples with this difference almost achieving statistical significance in one-dog homes where the dog was not allowed in the baby’s bedroom.

Our study had a higher percentage of homes in which Can f 1 was not detectable (38.7%) compared to the study of Arbes et al who analyzed the NHANES data (4.4% from bedroom floors).8 There are many possible reasons for a higher prevalence of undetectable Can f 1 in our study. The two most likely reasons are that we only measured Can f 1 in samples from the floor of the baby’s bedroom in contrast to measuring allergen from parental bedrooms and that our sample of homes we studied may have contained a higher percentage of urban dwellings where dogs are much less likely than in suburban homes (information on Can f 1 levels by urban environment was not presented in NHANES summary). Since Arbes et al did not present data on percentage of homes with detectable Can f 1 levels separately for homes with and without dogs, we are not able to directly compare our rates of Can f 1 detection. However, it is interesting to note that just over half of all zero-dog homes in our study had detectable Can f 1 levels suggesting that Can f 1 may last longer in the environment than is commonly thought.

Multivariable models suggested that whether the dog was spayed or neutered was most strongly associated with dog allergen levels in homes with detectable dog allergen levels where the dog was allowed indoors but not in the baby’s bedroom. Since the length of time the dog was in the home was assessed as opposed to recording the age of the dog (which is often related to altered status), taking into account dog age may clarify the relationship between a dog’s hormone level and its allergen production. In homes with detectable dog allergen levels where the dog was allowed in the baby’s bedroom, there were no factors, other than the presence of a dog, related to dog allergen levels. Since Can f 1 levels were significantly different in our study homes dependent on both whether the dog was allowed in the baby’s bedroom and duration of time the dog spent indoors daily, it would be reasonable that if time the dog was allowed in the baby’s bedroom had been captured, specific dog characteristics in our model such as dander level or shedding status might have been found to significantly influence Can f 1 levels.

There are some important clinical implications from our findings. The fact that we found lower Can f 1 levels in urban versus suburban homes is not surprising given that dogs in urban environments spent less time inside our study homes. However, confirming such a relationship has clinical relevance in that it implies that some degree of environmental control may be achieved by instructing allergic patients to have their dog spend more time outdoors if this is feasible and safe for the pet. We also found that Can f 1 levels were higher in homes with dogs that were spayed or neutered. To our knowledge, this relationship has not been previously reported. If such a relationship is confirmed in dogs, this may be clinically useful information that patients and their physicians should discuss. Lastly, although not quite statistically significant (p=0.08), there was a pattern of lowered dog allergen in homes with bare floors where the dog was not allowed in the bedroom. Future studies should further investigate this preliminary evidence that bare floors may be better in households with both dogs and allergy sufferers.

A limitation for this analysis included having a relatively small sample size for dog characteristic analyses. Also, age of the dog was not captured which may have influenced Can f 1 levels. Further, dog breed was based on maternal report rather than being assessed by our study staff; however, it was beyond the scope of the study to personally assess dog characteristics. Quantifying Can f 1 levels directly from the dog may have made our study more comparable to some others in the literature, but since the study focuses on determinants of allergic risk from the home environment, our quantification of dog allergen levels from the indoor environment may be more directly related to health outcomes. Despite these potential limitations, our study had numerous strengths. Our study is an unselected, population-based birth cohort study with a large sample size. Furthermore, our study homes were evenly divided between urban and suburban homes and had varying numbers of dogs, dog-keeping practices and a diverse collection of breeds between them.

Similar to other studies, we found that homes with dogs had higher Can f 1 levels than homes without dogs;4–6 however, our research found that there are additional factors that influence dog allergen levels that are often not measured. Whether the dog was allowed in the home or allowed in the area from which the environmental sample was collected and the amount of time the dog was indoors mattered. Consideration of these factors is essential to accurately assessing factors influencing dog allergen (and its abatement) in the home.

Acknowledgments

NIAID R01 AI50681

The authors thank the Wayne County Health, Environment, Allergy & Asthma Longitudinal Study families for their continued participation in WHEALS as well as Henry Ford Health System field and laboratory staff for their dedication to this project.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions: Ms. Nicholas had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Wegienka, Zoratti, Ownby, Johnson

Acquisition of data: Wegienka, Zoratti, Ownby, Johnson

Analysis and interpretation of data: Nicholas, Wegienka, Havstad

Drafting of the manuscript: Nicholas

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Nicholas, Wegienka, Havstad, Zoratti, Ownby, Johnson

Statistical analysis: Nicholas, Havstad

Obtaining funding: Wegienka, Zoratti, Ownby, Johnson

Administrative, technical, or material support: Nicholas, Wegienka, Havstad, Zoratti, Ownby, Johnson

Supervision: Wegienka, Zoratti, Ownby, Johnson

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Charlotte Nicholas, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, MI, USA.

Ganesa Wegienka, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, MI, USA.

Suzanne Havstad, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, MI, USA.

Edward Zoratti, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, MI, USA.

Dennis Ownby, Medical College of Georgia, Augusta, GA, USA.

Christine Cole Johnson, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, MI, USA.

References

- 1.Battling Pet Allergies. [Cited 2010 May 07.] Available from http://www.aaaai.org/patients/just4kids/pet_allergies.asp.

- 2.Abraham CM, Ownby DR, Peterson EL, et al. The relationship between seroatopy and symptoms of either allergic rhinitis or asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1099–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.A community approach to dog bite prevention. American Veterinary Medical Association Task Force on Canine Aggression and Human-Canine Interactions. doi: 10.2460/javma.2001.218.1732. [Cited 2010 May 07.] Available from http://www.avma.org/public_health/dogbite/dogbite.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Bufford JD, Reardon CL, Li Z, et al. Effects of dog ownership in early childhood on immune development and atopic diseases. Clinical and Experimental Allergy. 2008;38:1635–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egmar A-C, Emenius G, Almqvist C, Wickman M. Can and dog allergen in mattresses and textile-covered floors of homes which do or do not have pets, either in the past or currently. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1998;9:31–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.1998.tb00297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perry TT, Wood RA, Matsui EC, Curtin-Brosnan JRC, Eggleston PA. Room-specific characteristics of suburban homes as predictors of indoor allergen concentrations. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97:628–35. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curtin-Brosnan J, Matsui EC, Breysse P, et al. Parent report of pests and pets and indoor allergen levels in inner-city homes. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101:517–23. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60291-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arbes SJ, Cohn RD, Yin M, Muilenberg ML, Friedman W, Zeldin DC. Dog allergen (Can f 1) and cat allergen (Fel d 1) in US homes: Results from the National Survey of Lead and Allergens in Housing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:111–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabito FA, Iqbal S, Holt E, Grimsley LF, Islam TMS, Scott SK. Prevalence of indoor allergen exposures among New Orleans Children with Asthma. J Urban Health. 2007;84(6):782–92. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9216-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheehan WJ, Rangsithienchai PA, Muilenberg ML, et al. Mouse allergens in urban elementary schools and homes of children with asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;102:125–30. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60242-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams LK, McPhee RA, Ownby DR, et al. Gene-environment interactions with CD14 C-260T and their relationship to total serum IgE levels in adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:851–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicholas C, Wegienka G, Havstad S, Ownby D, Johnson C. Influence of cat characteristics on Fel d 1 levels in the home. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101:47–50. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60834-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palmer Joan. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dog Breeds. Edison (NJ): Wellfleet Press; 1994. (reprinted in 2008) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breeds: Information on over 150 breeds. [Cited 2010 May 07.] Available from http://www.akc.org/breeds/index.cfm?nav_area=breeds.