Abstract

Myostatin is a TGF-β family member that normally acts to limit skeletal muscle mass. Follistatin is a myostatin-binding protein that can inhibit myostatin activity in vitro and promote muscle growth in vivo. Mice homozygous for a mutation in the Fst gene have been shown to die immediately after birth but have a reduced amount of muscle tissue, consistent with a role for follistatin in regulating myogenesis. Here, we show that Fst mutant mice exhibit haploinsufficiency, with muscles of Fst heterozygotes having significantly reduced size, a shift toward more oxidative fiber types, an impairment of muscle remodeling in response to cardiotoxin-induced injury, and a reduction in tetanic force production yet a maintenance of specific force. We show that the effect of heterozygous loss of Fst is at least partially retained in a Mstn-null background, implying that follistatin normally acts to inhibit other TGF-β family members in addition to myostatin to regulate muscle size. Finally, we present genetic evidence suggesting that activin A may be one of the ligands that is regulated by follistatin and that functions with myostatin to limit muscle mass. These findings potentially have important implications with respect to the development of therapeutics targeting this signaling pathway to preserve muscle mass and prevent muscle atrophy in a variety of inherited and acquired forms of muscle degeneration.

In this paper, we present genetic evidence that follistatin controls skeletal muscle mass and function by regulating the activities of myostatin and activin A.

Myostatin is a TGF-β family member that acts as a negative regulator of skeletal muscle mass (1). Mstn mRNA is first detectable in midgestation embryos in cells of the myotome compartment of developing somites and continues to be expressed in muscle throughout embryogenesis as well as in adult mice. Mice homozygous for a deletion of the Mstn gene exhibit dramatic and widespread increases in skeletal muscle mass, with individual muscles of Mstn-knockout mice weighing about twice as much as those of wild-type mice as a result of a combination of increased fiber number and muscle fiber hypertrophy. These findings suggested that myostatin plays two distinct roles to regulate muscle mass, one to regulate the number of muscle fibers that are formed during development and a second to regulate growth of those fibers. In this respect, selective postnatal loss of myostatin signaling as a result of either deletion of the Mstn gene (2,3) or pharmacological inhibition of myostatin activity (4,5,6,7) can cause significant muscle fiber hypertrophy, demonstrating that myostatin plays an important role in regulating muscle homeostasis in adult mice. Moreover, genetic studies in cattle (8,9,10,11), sheep (12), dogs (13), and humans (14) have all shown that the function of myostatin as a negative regulator of muscle mass is highly conserved across species.

The identification of myostatin and its biological function has raised the possibility that inhibition of myostatin activity may be an effective strategy for increasing muscle mass and strength in patients with inherited and acquired clinical conditions associated with debilitating muscle loss (for reviews, see Refs. 15,16,17). Indeed, studies employing mouse models of muscle diseases have suggested that loss of myostatin signaling has beneficial effects in a wide range of disease settings, including muscular dystrophy, spinal muscular atrophy, cachexia, steroid-induced myopathy, and age-related sarcopenia. Moreover, loss of myostatin signaling has been shown to decrease fat accumulation and improve glucose metabolism in models of metabolic diseases, raising the possibility that targeting myostatin may also have applications for diseases such as obesity and type II diabetes. As a result, there has been an extensive effort directed at understanding the mechanisms by which myostatin activity is normally regulated and on identifying the components of the myostatin-signaling pathway with the long-term goal of developing the most effective therapeutic strategies for targeting its actions.

In this regard, considerable progress has been made in terms of understanding how myostatin activity is regulated extracellularly by binding proteins (for review, see Ref. 15). One of these regulatory proteins is follistatin (FST), which is capable of acting as a potent myostatin antagonist. Follistatin has been shown to be capable of binding directly to myostatin and inhibiting its activity in receptor binding and reporter gene assays in vitro (18,19,20). Moreover, follistatin also appears to be capable of blocking endogenous myostatin activity in vivo, as transgenic mice overexpressing follistatin specifically in skeletal muscle have been shown to exhibit dramatic increases in muscle growth comparable to those seen in Mstn-knockout mice (18,21,22). Finally, mice homozygous for a targeted mutation in the Fst gene have reduced muscle mass at birth (23), consistent with a role for follistatin in inhibiting myostatin activity during embryonic development. The fact that Fst−/− mice die immediately after birth, however, has hampered a more detailed analysis of the role of follistatin in regulating muscle homeostasis. Here, we show that Fst mutant mice exhibit haploinsufficiency, with Fst+/− mice having significant reductions in muscle mass accompanied by corresponding decreases in muscle function and impaired muscle regeneration. Furthermore, we show that this muscle phenotype reflects a normal role for follistatin in regulating not only myostatin but also other TGF-β family members that cooperate with mysotatin to limit muscle growth, and we present genetic evidence that activin A may be one of these key cooperating ligands.

Results

Because mice homozygous for a deletion of Fst gene die immediately after birth (23) and because many components of the myostatin-regulatory system have shown dose-dependent effects when manipulated in vivo, we investigated the possibility that Fst mutant mice might exhibit haploinsufficiency with respect to muscle growth and function. We backcrossed the Fst loss-of-function mutation at least 10 times onto a C57BL/6 background and then analyzed muscle weights in Fst+/− mice at 10 wk of age. As shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1 (bottom panel), Fst+/− mice exhibited a clear muscle phenotype, with muscle weights in Fst+/− mice being lower by about 15–20% compared with those of wild-type mice. These reductions in muscle weights were highly statistically significant (P values ranged from 10−8 to 10−12), were seen in all four muscles that were analyzed (pectoralis, triceps, quadriceps, and gastrocnemius) as well as in both males and females, and were also apparent after normalizing for total body weights (Supplemental Table 1 and Supplemental Fig. 1 published on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org).

Table 1.

Muscle weights of mutant mice

| Body weight (g) | Muscle weights (mg)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pectoralis | Triceps | Quadriceps | Gastrocnemius | |||

| Males | ||||||

| Wild type | (n = 36) | 24.0 ± 0.3 | 74.5 ± 1.0 | 94.8 ± 1.2 | 193.3 ± 2.5 | 137.5 ± 1.7 |

| Fst+/− | (n = 15) | 23.3 ± 0.7 | 60.7 ± 1.0a | 78.3 ± 1.4a | 157.4 ± 3.0a | 118.2 ± 2.0a |

| Fstl3−/− | (n = 23) | 25.3 ± 0.6 | 77.2 ± 1.7 | 97.9 ± 1.6 | 200.7 ± 3.8 | 138.2 ± 2.1 |

| Mstn+/− | (n = 17) | 27.6 ± 0.4 | 97.4 ± 1.6 | 123.2 ± 2.4 | 252.6 ± 4.5 | 181.2 ± 3.9 |

| Mstn+/−, Fst+/− | (n = 12) | 26.0 ± 0.4b | 79.3 ± 1.5c | 100.0 ± 2.0c | 197.8 ± 5.3c | 147.4 ± 3.2c |

| Mstn−/− | (n = 8) | 33.8 ± 0.9 | 215.1 ± 7.9 | 231.8 ± 7.3 | 407.1 ± 12.1 | 302.0 ± 10.3 |

| Mstn−/−, Fst+/− | (n = 10) | 31.0 ± 1.3 | 174.3 ± 10.0d | 206.7 ± 10.4 | 352.6 ± 17.3e | 274.4 ± 13.4 |

| inhβA+/− | (n = 21) | 25.0 ± 0.4f | 80.8 ± 1.2a | 104.0 ± 1.6a | 215.0 ± 3.8a | 152.3 ± 2.2a |

| inhβB+/− | (n = 13) | 24.3 ± 0.5 | 73.5 ± 1.7 | 95.8 ± 2.5 | 190.1 ± 3.9 | 134.6 ± 2.2 |

| inhβB−/− | (n = 15) | 24.7 ± 0.4 | 78.9 ± 1.7f | 100.4 ± 2.5f | 201.3 ± 5.0 | 139.1 ± 2.9 |

| inhβC+/−, βE+/− | (n = 12) | 24.8 ± 1.2 | 76.2 ± 3.3 | 95.8 ± 2.6 | 192.2 ± 8.3 | 133.9 ± 5.7 |

| inhβC−/−, βE−/− | (n = 18) | 25.0 ± 0.4f | 76.9 ± 1.3 | 96.8 ± 1.9 | 196.9 ± 3.3 | 138.6 ± 2.0 |

| Females | ||||||

| Wild type | (n = 22) | 19.0 ± 0.2 | 48.3 ± 0.8 | 69.5 ± 0.9 | 146.2 ± 1.8 | 102.5 ± 1.2 |

| Fst+/− | (n = 14) | 17.2 ± 0.4a | 39.1 ± 0.9a | 56.6 ± 1.0a | 115.2 ± 2.0a | 84.7 ± 1.7a |

| Fstl3−/− | (n = 29) | 19.1 ± 0.3 | 50.6 ± 0.8f | 72.5 ± 0.9f | 149.4 ± 1.8 | 100.7 ± 1.1 |

| Fst+/−, Fstl3+/− | (n = 9) | 16.3 ± 0.5a | 37.3 ± 1.6a | 57.0 ± 2.2a | 113.9 ± 4.6a | 82.9 ± 2.8a |

| Fst+/−, Fstl3−/− | (n = 7) | 16.9 ± 0.6g | 36.9 ± 1.4a | 57.3 ± 1.5a | 116.1 ± 4.0a | 80.3 ± 2.6a |

| Mstn+/− | (n = 13) | 22.0 ± 0.4 | 64.2 ± 1.0 | 90.5 ± 1.1 | 185.1 ± 2.3 | 130.5 ± 1.8 |

| Mstn+/−, Fst+/− | (n = 10) | 20.6 ± 0.4h | 52.3 ± 1.3c | 74.6 ± 2.0c | 152.6 ± 3.5c | 111.7 ± 2.2c |

| Mstn−/− | (n = 13) | 24.5 ± 0.4 | 111.0 ± 2.3 | 148.5 ± 1.8 | 276.8 ± 4.2 | 195.8 ± 2.4 |

| Mstn−/−, Fst+/− | (n = 17) | 24.3 ± 0.3 | 94.4 ± 1.6i | 139.2 ± 1.6i | 251.2 ± 3.4i | 186.9 ± 2.4e |

| inhβA+/− | (n = 20) | 19.4 ± 0.2 | 52.4 ± 0.9a | 73.3 ± 1.3f | 155.3 ± 2.2g | 109.3 ± 1.7g |

| inhβB+/− | (n = 15) | 19.8 ± 0.4 | 50.5 ± 0.8f | 70.0 ± 1.2 | 147.5 ± 2.7 | 100.8 ± 1.8 |

| inhβB−/− | (n = 12) | 20.0 ± 0.6 | 51.8 ± 1.4f | 69.9 ± 1.2 | 144.3 ± 3.3 | 100.8 ± 2.2 |

| inhβC+/−, βE+/− | (n = 15) | 18.5 ± 0.7 | 49.2 ± 1.5 | 69.4 ± 2.3 | 141.0 ± 5.5 | 97.5 ± 4.5 |

| inhβC−/−, βE−/− | (n = 25) | 19.1 ± 0.2 | 49.9 ± 0.9 | 70.5 ± 1.0 | 150.4 ± 2.1 | 103.0 ± 1.4 |

P < 0.001 vs. wild type;

P < 0.01 vs. Mstn+/−;

P < 0.001 vs. Mstn+/−;

P < 0.01 vs. Mstn−/−;

P < 0.05 vs. Mstn−/−;

P < 0.05 vs. wild-type;

P < 0.01 vs. wild type;

P < 0.05 vs. Mstn+/−;

P < 0.001 vs. Mstn−/−.

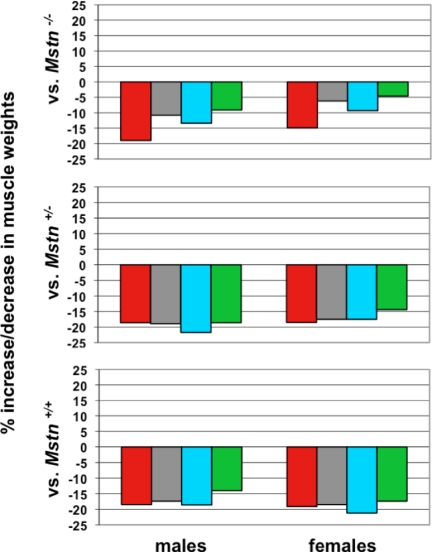

Figure 1.

Effect of heterozygous loss of Fst on muscle mass. Bottom panel shows percent decrease in muscle weights in Fst+/− mice compared with wild-type mice. Middle panel shows percent decrease in muscle weights in Fst+/−, Mstn+/− mice compared with Fst+/+, Mstn+/− mice. Top panel shows percent decrease in muscle weights in Fst+/−, Mstn−/− mice compared with Fst+/+, Mstn−/− mice. All calculations were made from the data shown in Table 1. Muscles analyzed were: pectoralis (red), triceps (gray), quadriceps (blue), and gastrocnemius (green).

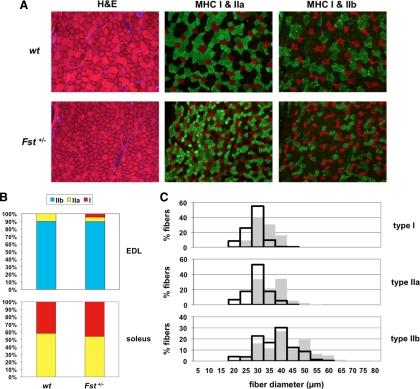

These effects on muscle mass were the converse of what has been observed in mice with mutations in the Mstn gene and were therefore consistent with a normal role for follistatin in inhibiting myostatin activity in vivo. We showed previously that the higher muscle mass seen in Mstn−/− mice results from effects on both fiber numbers and fiber sizes (1). To determine whether both fiber numbers and fiber sizes are also affected by the Fst mutation, we carried out morphometric analysis of sections of the gastrocnemius muscle. As shown in Table 2, total fiber number in the gastrocnemius appeared to be unaffected in Fst+/− mice compared with wild-type controls. One difference clearly evident in hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections, however, was the increased proportion of smaller, more darkly stained fibers in muscles of Fst+/− mice (Fig. 2A), raising the possibility that heterozygous loss of Fst might affect fiber type distribution. In this respect, previous studies have shown that loss of myostatin affects the relative proportions of the different fiber types, with Mstn−/− mice having a decreased number of type I fibers and an increased number of type II fibers in the soleus as well as a shift in the distribution of type II fibers toward more of the glycolytic type IIb fibers in the extensor digitorum longus (EDL) (24,25,26,27). Fiber type analysis of the gastrocnemius muscle of Fst+/− mice revealed an opposite shift toward more oxidative fibers. In particular, the number of oxidative type I fibers was increased significantly in the gastrocnemius muscle of Fst+/− mice (Table 2), and most of the small darkly stained fibers that appeared to be increased in number in Fst+/− mice corresponded to mixed glycolytic/oxidative type IIa fibers, representing a further shift away from glycolytic type IIb fibers (Fig. 2A). We observed similar trends toward more oxidative fibers in other muscles as well, with the appearance of a significant percentage of type I fibers in the EDL (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2B) and an approximately 5% shift from type IIa fibers to type I fibers in the soleus, although these latter data did not reach statistical significance.

Table 2.

Analysis of gastrocnemius/plantaris muscles

| Wild type (n = 3) | Fst+/− (n = 3) | % Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total fiber number | 8340 ± 323 | 8260 ± 521 | −1.0 |

| Type I fiber number | 124 ± 30 | 206 ± 21 | +66.1 |

| Percentage type I fibers | 1.47 ± 0.3 | 2.50 ± 0.2a | +69.7 |

| Mean fiber diameters (μm) | |||

| Type I fibers | 32.8 ± 1.0 | 28.5 ± 1.2a | −13.0 |

| Type IIa fibers | 35.6 ± 2.4 | 29.9 ± 1.2b | −16.1 |

| Type IIb fibers | 41.9 ± 0.1 | 37.3 ± 1.3a | −11.0 |

| All fiber types | 41.0 ± 0.6 | 36.0 ± 1.5a | −12.2 |

P < 0.05 vs. wild type;

P = 0.08 vs. wild type.

Figure 2.

Fiber type analysis. A, Sections of gastrocnemius muscles either stained with hematoxylin and eosin or incubated with antibodies against type I (red), type IIa (green), or type IIb (green) MHC isoforms. Note that muscles of Fst+/− mice had increased numbers of small, darkly stained fibers, which corresponded to type IIa fibers, as well as increased numbers of type I fibers. B, Fiber type distributions in the EDL and soleus muscles. Note the appearance of type I fibers and the decrease in proportion of type IIa fibers in Fst+/− EDL muscle. C, Distribution of type I, IIa, and IIb fiber diameters in the gastrocnemius muscle. Solid gray bars represent muscle fibers from wild-type mice, and open black bars represent muscle fibers from Fst+/− mice. Note the shift in the distributions toward fibers with smaller diameters in muscles of Fst+/− mice. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; wt, wild type.

To determine whether differences in fiber sizes could account for the differences in muscle weights between Fst+/− and wild-type mice, we measured fiber diameters in representative sections of the gastrocnemius muscle. As shown in Fig. 2C and Table 2, the distribution of fiber diameters was shifted toward smaller fibers in the gastrocnemius muscle of Fst+/− mice compared with that of wild-type mice. Significantly, the shift in the distribution toward smaller fibers was observed not only in type II fibers but also in type I fibers. Hence, the overall decrease in the weight of the gastrocnemius muscle of Fst+/− mice appeared to result from a combination of an increase in the proportion of fiber types that are generally smaller in size and a decrease in mean fiber diameter for each fiber type.

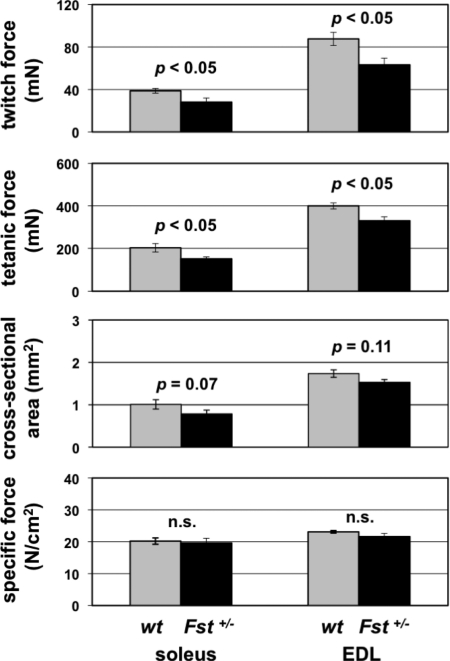

We also analyzed the effects of heterozygous loss of Fst on muscle function. Previous studies have shown that inhibition of myostatin activity in mice results in increased muscle force (4). To determine whether the lower muscle mass seen in Fst+/− mice results in lower muscle force production, we carried out force measurements on isolated muscles. As shown in Fig. 3, twitch and tetanic force were lower in Fst+/− mice by 27% and 26%, respectively, in the soleus and by 28% and 17%, respectively, in the EDL, which was commensurate with the reduction in cross-sectional area. Hence, the lower muscle weights seen in Fst+/− mice appear to result in corresponding decreases in tetanic force production, with no statistically significant changes in specific force.

Figure 3.

Force measurements in the soleus and EDL muscles of wild-type and Fst+/− mice. Note the decreased twitch and tetanic force with no change in specific force in muscles of Fst+/− mice. n.s., Nonsignificant; P > 0.20 wt, wild type.

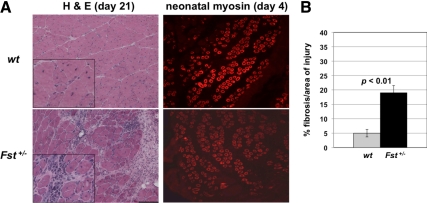

Loss of myostatin has been shown to affect not only muscle mass and strength but also the ability of the muscle to regenerate. In particular, loss of myostatin activity has been shown to result in an enhanced regenerative response to both chronic (for reviews, see Refs. 15,16,17) and acute (28,29,30) injury. We investigated the possibility that heterozygous loss of Fst might have the opposite effect on muscle regeneration by examining the response of the gastrocnemius muscle to cardiotoxin-induced injury. Indeed, 21 d after induction of injury, Fst heterozygous mice showed clear deficits in muscle remodeling (Fig. 4A) with an almost 4-fold increase in the amount of muscle fibrosis as compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, at 4 d after cardiotoxin-induced injury, Fst heterozygous mice showed no obvious difference in neonatal myosin-positive fibers compared with wild-type mice (Fig. 4A), suggesting that the defects in muscle remodeling may result from failed muscle maturation rather than impaired satellite cell function.

Figure 4.

Impaired muscle regeneration in Fst+/− mice. A, Sections of gastrocnemius muscles of wild-type and Fst+/− mice after cardiotoxin-induced injury. At 21 d after injury, note the centrally located nuclei characteristic of regenerating fibers in the wild-type injured muscle (see inset) and the significantly increased extent of fibrosis in the Fst+/− muscle. At 4 d after injury, note the presence of neonatal myosin in both wild type and Fst+/− muscle. B, Quantification of amount of fibrosis at 21 d after cardiotoxin-induced injury as assessed by measurement of percent fibrotic area relative to total injured area. H&E, Hematoxylin and eosin; wt, wild type.

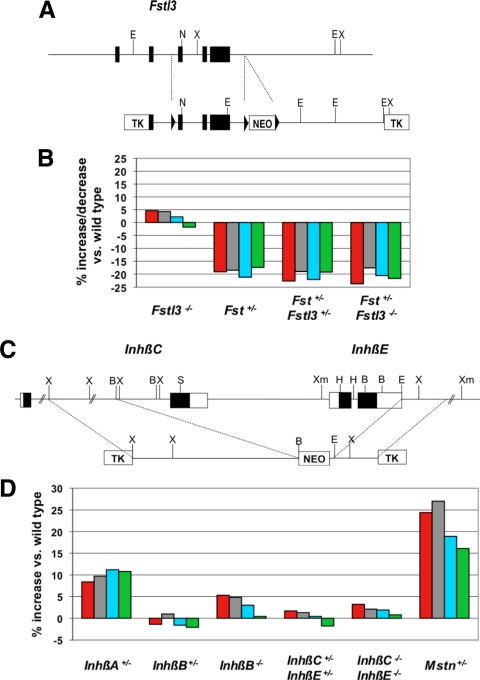

The fact that we could observe reductions in muscle mass in Fst+/− mice opened up the possibility of looking at genetic interactions between Fst and other genes encoding components of this regulatory system. We first looked at genetic interactions between Fst and Fstl3, which is another member of the follistatin gene family. Previous studies had shown that like follistatin, FSTL-3 (follistatin-like 3; also called FLRG) is capable of blocking myostatin activity in vitro (31) and promoting muscle growth when overexpressed in vivo (21,22). What role FSTL-3 normally plays in regulating myostatin activity in vivo is unclear, however, as homozygous Fstl3 mutant mice have been reported to have normal muscle mass (32). We investigated the possibility that the lack of a clear muscle phenotype in Fstl3 mutant mice might reflect functional redundancy between FSTL-3 and follistatin. For these studies, we used a line of mice that we independently generated carrying a targeted deletion of Fstl3. As shown in Fig. 5A, we generated mice in which we deleted exons 3–5, which contains most of the protein-coding region, including both of the follistatin domains of FSTL-3. We then backcrossed this deletion allele at least seven times onto a C57BL/6 background for analysis.

Figure 5.

Effect of a mutation in Fstl3 and in genes encoding inhibin β-subunits on muscle mass. A, Diagram of Fstl3-targeting strategy. Mice carrying the targeted allele were crossed to EIIa-cre transgenic mice (33) to generate mice in which recombination had occurred between the outside LoxP sites (denoted by triangles), thereby resulting in a mutant allele in which exons 3–5 were completely deleted in the germline. B, Effects of the deletion mutation in Fstl3 either alone or in combination with heterozygous loss of Fst. C, Diagram of InhβC/InhβE-targeting strategy. D, Effect of Inhβ mutations in male mice. In the bar graphs shown in Panels b and d, numbers represent percent increase or decrease in muscle mass relative to wild-type mice and were calculated from the data shown in Table 1. Data from Mstn+/− mice (21) are shown for comparison. Muscles analyzed were: pectoralis (red), triceps (gray), quadriceps (blue), and gastrocnemius (green). TK, Thymidine kinase.

Consistent with findings previously reported by others (32), mice homozygous for a deletion of Fstl3 were viable and had relatively normal muscle weights (Table 1). To investigate possible functional redundancy, we analyzed the effect of crossing the Fst loss-of-function mutation onto an Fstl3 mutant background. As shown in Table 1 and Fig. 5B, we observed no additive effects of the Fst and Fstl3 mutations in terms of reducing muscle mass; that is, neither Fst+/−, Fstl3+/− nor Fst+/−, Fstl3−/− mice showed further reductions in muscle weights compared with Fst+/−, Fstl3+/+ mice. Although we have not ruled out the possibility that we might see effects of FSTL-3 loss in mice completely lacking follistatin, our data suggest that these two proteins are not functionally redundant in terms of regulating muscle growth. Hence, despite all of the evidence implicating FSTL-3 as a key regulator of myostatin activity in vivo, we were unable to uncover any effects of genetic loss of Fstl3 on muscle mass in these studies.

We also took advantage of the muscle phenotype in Fst+/− mice to investigate genetic interactions between Fst and Mstn. Our rationale for these studies was that two lines of investigation had demonstrated that other members of the TGF-β family, in addition to myostatin, seem to play important roles in limiting muscle growth. In particular, both overexpression of follistatin as a muscle-specific transgene and systemic administration of a soluble form of one of the known myostatin receptors (ACVR2B) had been shown to cause increases in muscle mass not only in wild-type mice but also in Mstn−/− mice, implying that these inhibitors were exerting their effects by targeting other TGF-β family members in addition to myostatin (7,18,21). Hence, we sought to determine whether the reductions in muscle weights seen in Fst+/− mice result entirely from increased levels of myostatin signaling.

Our approach was to look for genetic interactions between Fst and Mstn by examining the effect of introducing the Fst mutation onto a Mstn mutant background. If the sole role for follistatin in regulating muscle mass in vivo is to block myostatin signaling, then the Fst mutation would be predicted to have no effect in the complete absence of myostatin. If, on the other hand, follistatin normally acts to block multiple ligands to regulate muscle mass, then the Fst mutation might be expected to have at least some effect on muscle mass even in a Mstn mutant background. As shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1, we found the latter to be the case. Specifically, heterozygous loss of Fst caused reductions in muscle mass in both Mstn+/− and Mstn−/− mutant backgrounds in both male and female mice. The effects of the Fst mutation were somewhat attenuated in the complete Mstn-null background, implying that part of the effect of follistatin loss in Mstn+/+ mice likely results from loss of inhibition of myostatin signaling. Nevertheless, the fact that the Fst mutation had at least some effect on muscle weights even in the Mstn-null background implies that this residual effect resulted from loss of inhibition of other TGF-β family members in these mutant mice. Hence, these studies suggest that follistatin normally acts in vivo to inhibit multiple TGF-β family members, including myostatin, that function to limit muscle mass.

In the final set of experiments, we used genetic approaches to attempt to determine the identity of the ligand (or ligands) that cooperates with myostatin to suppress muscle growth. The TGF-β superfamily consists of almost 40 proteins (for reviews, see Refs 34 and 35), and many could be eliminated as possible candidates based on their known binding properties, because the key ligand can be blocked both by follistatin and by the soluble ACVR2B receptor. The most obvious candidate was growth/differentiation factor (GDF)-11, which is highly related to myostatin and is also expressed in skeletal muscle; genetic studies to date, however, have not revealed any role for GDF-11 in regulating muscle (26). As a result, we decided to extend our genetic analysis to other candidate ligands. The activins, which are dimers of inhibin-β subunits, were attractive as candidates because they had been shown to have in vitro activities on muscle cells (36,37,38,39). Moreover, a recent study showed that activin A is capable of inducing atrophy when overexpressed in muscle (40).

We decided to focus our initial analysis on mice carrying mutations in genes encoding the inhibin-β subunits. In mice, four genes encoding inhibin-β subunits have been identified, InhβA, InhβB, InhβC, and InhβE (for review, see Ref. 34). Mice carrying targeted mutations in each of these genes have been generated and characterized previously (41,42,43,44), and for InhβA and InhβB, we analyzed the existing mutant mouse lines. For InhβC and InhβE, however, we analyzed a double-mutant mouse line that we generated independently in which the exon encoding the C-terminal domain of InhβC and the entire coding sequence of InhβE were deleted in the same mutant allele (Fig. 5C). All of these Inhβ mutant alleles were backcrossed at least six times onto a C57BL/6 genetic background before analysis.

For the InhβB and InhβC/βE mutations, we were able to analyze the effect of complete loss of function, as the homozygous mutants are viable as adults. In the case of InhβA, however, homozygous loss has been shown to lead to embryonic lethality (43); therefore, we were only able to analyze the effect of heterozygous loss of InhβA. As shown in Table 1 and Fig. 5D, the most significant effect that we observed was, in fact, in mice heterozygous for the InhβA loss-of-function mutation, which exhibited statistically significant increases in weights of all four muscles that were examined. The effects seen in InhβA+/− mice were most pronounced in males, which had increases ranging from about 8–11%, with P values ranging from 2 × 10−4 to 2 × 10−6 depending on the specific muscle. The effects in females were generally lower, with increases ranging from about 5–8%. These trends were also present after normalizing muscle weights to total body weights (Supplemental Table 1 and Supplemental Fig. 1). Mutations in each of the other genes had little or no effect, except in the case of InhβB homozygous mutants, in which two muscles (pectoralis and triceps) also showed statistically significant increases, although the magnitude of the effects was lower than that seen in InhβA+/− mice. These data provide the first loss-of-function genetic evidence that activin A may be one of the key ligands that functions with myostatin to limit muscle mass.

Discussion

Follistatin is a potent myostatin inhibitor that can cause dramatic increases in muscle mass when overexpressed as a transgene in mice (18,21,22). Follistatin is known to play an important role in regulating muscle development, because newborn Fst mutant mice have a reduced amount of muscle tissue, which is readily discernible by histological analysis (23). Because homozygous Fst mutants die immediately after birth, however, little is known about the role that follistatin normally plays in regulating muscle homeostasis. Here, we have shown that the Fst loss-of-function mutation exhibits haploinsufficiency, with Fst+/− mice having lower overall muscle mass by about 15–20%. These reductions in muscle mass were highly statistically significant and resulted from a shift toward smaller diameter fibers with little or no apparent effect on total fiber number. This shift toward smaller fibers could be attributed to two distinct effects of the Fst mutation. First, there was a shift in the distribution of fiber types resulting in an increased proportion of smaller, more oxidative fibers in muscles of Fst+/− mice compared with those of wild-type mice. Second, for each fiber type that was examined, there was a shift toward fibers with smaller diameters in muscles of Fst+/− mice compared with those of wild-type mice. All of these effects are the opposite of what has been described in mice with absent or reduced myostatin activity, which exhibit increased muscle mass, a shift in fiber types toward more glycolytic fibers, and hypertrophy of both type I and type II fibers (1,24,25,26,27,45). We also found that Fst+/− mice exhibit an impaired muscle remodeling response to chemical injury, which also contrasts with the enhanced muscle regeneration seen in Mstn−/− mice (for reviews, see Refs. 15,16,17).

All of these findings demonstrate that follistatin normally functions to suppress activity of this signaling pathway in muscle. In this respect, an important point is that we were able to document significant effects of follistatin loss even though these mice still retained one normal copy of the Fst gene. Hence, the effect of follistatin is almost certainly dose dependent, as has been shown for many other components of this regulatory system, and we presume that complete loss of follistatin activity in muscle would lead to much more dramatic effects. We also investigated the possibility that the effects of follistatin loss might have been attenuated by functional compensation by the related protein, FSTL-3. FSTL-3 (also called FLRG) contains two follistatin domains (vs. three for follistatin itself), and like follistatin, FSTL-3 is capable of binding and inhibiting both activin and myostatin in vitro (31,46,47,48) and increasing muscle mass when overexpressed in vivo (21,22). FSTL-3 has been further implicated in the regulation of myostatin based on the fact that FSTL-3 could be detected in a complex with myostatin in both mouse and human blood samples (31). Gene-targeting studies, however, demonstrated that complete loss of FSTL-3 had no effects on muscle mass (32). Using an independently generated Fstl3-knockout line, we also observed no effect of homozygous loss of Fstl3 on muscle mass, and furthermore, we were unable to detect any additive effects of the Fst and Fstl3 loss-of-function mutations. Hence, we were unable to detect any evidence that follistatin and FSTL-3 are functionally redundant with respect to the regulation of muscle mass by myostatin and related proteins.

We also examined genetic interactions between Fst and Mstn. In particular, we showed that the effects of follistatin loss are seen even in mice null for Mstn, implying that myostatin cannot be the sole target for follistatin and that follistatin normally acts to block the activities of multiple TGF-β family members that function to limit muscle mass. These findings are consistent with the results of two prior studies. One set of experiments was the analysis of mice treated with a soluble form of ACVR2B, which has been shown to be one of the activin type II receptors involved in mediating myostatin signaling (7,18,49). The soluble form of ACVR2B (ACVR2B/Fc) was shown to be capable of blocking myostatin activity in vitro, and administration of ACVR2B/Fc to adult mice was shown to cause dramatic muscle growth (up to 40–60% in 2 wk). Significantly, this effect was attenuated, but not eliminated, in Mstn−/− mice, implying that ACVR2B/Fc was targeting at least one additional ligand that also functions to block muscle growth (7). A second set of experiments was the analysis of transgenic mice overexpressing follistatin in muscle (18). As expected, based on the ability of follistatin to inhibit myostatin, these transgenic mice exhibited significant increases in muscle mass. As in the studies with the soluble ACVR2B receptor, however, the follistatin transgene could also cause increases in muscle growth even in mice lacking myostatin (21); in fact, the follistatin transgene could cause yet another doubling of muscle mass on top of the doubling seen in the absence of myostatin (i.e. an overall quadrupling).

All of these studies demonstrate that at least one other TGF-β family member, in addition to myostatin, also functions to limit muscle mass in vivo. Thus, the capacity for increasing muscle growth by targeting this signaling pathway is much more substantial than previously appreciated. We have been using a genetic approach to determining the identity of this other ligand. An obvious candidate was GDF-11, which is highly related to myostatin (1,50). Initial gene-knockout studies demonstrated that mice completely lacking GDF-11 exhibit multiple developmental defects and die during the perinatal period (51), which precluded a detailed analysis of the role of GDF-11 in muscle. Subsequent studies utilizing a floxed Gdf11 allele, however, revealed no effect of Gdf11 deletion specifically in skeletal muscle either alone or in combination with a Mstn-knockout mutation (26).

Perhaps the next most likely candidates were the activins, which have been shown to be capable of regulating differentiation of muscle cells in culture (36,37,38,39) and share a common receptor with myostatin (for reviews, see Refs. 15 and 34). Moreover, a recent study also suggested the possibility that activins may be involved in regulating muscle mass based on their ability to induce muscle atrophy when overexpressed in vivo and based on differential effects seen in vivo between follistatin and a follistatin variant with reduced affinity for activin (40). Finally, another recent study implicated activins as well as a number of other ligands, including GDF-11, BMP-9, and BMP-10, as possible candidates based on the fact that these could be affinity purified from serum using the ACVR2B/Fc ligand trap (38). Indeed, by analyzing mouse strains carrying targeted deletions in each of the genes encoding the inhibin β-subunits, we observed increases in muscle mass in mice heterozygous for the InhβA mutation, consistent with an important role for activin A in regulating muscle mass. Although further characterization of the muscles of these mice will be required to demonstrate that these effects on muscle mass result from muscle fiber hypertrophy, these data provide the first genetic loss-of-function evidence that activin A may be one of the key ligands that function with myostatin to limit muscle mass.

Although the increases in muscle mass that we observed in InhβA mutants were relatively modest, we believe that the overall role that activin A may play is potentially much more substantial for several reasons. First, this phenotype was observed in mice that still retained one functional copy of the InhβA gene. By comparison, male mice heterozygous for a mutation in Mstn exhibit increases in muscle weights ranging from 16–27% (21); hence, the magnitude of the effects seen in male InhβA+/− mice was approximately half that seen in Mstn+/− mice. Homozygous loss of Mstn results in increases in muscle weights of 100–150%, and we presume that greater loss of activin A signaling would similarly result in a significantly enhanced effect. Second, the existence of multiple Inhβ genes raises the possibility of functional redundancy, and in this respect, we did see some effect, albeit quite small, in InhβB homozygous mutants. Third, a mutation in the InhβA gene affects the production of both activin A (as well as activin AB) and inhibin A, which share the βA-subunit. Given that activins and inhibins generally have counteracting activities, it is perhaps fortuitous that we were able to see any phenotype at all in InhβA+/− mice, because the mutation would lead to decreases in both activin A and an inhibitor of activin signaling. We believe that the likely explanation is that whereas activins are believed to act mostly via a paracrine mechanism, inhibins appear to be capable of regulating signaling in an endocrine manner (for reviews, see Refs. 52,53,54), and the predominant circulating form of inhibin is known to be inhibin B (for reviews, see Refs. 55 and 56). Hence, the InhβA mutation would be predicted to reduce levels of activin A but have only a minimal effect on circulating inhibin levels.

Clearly, additional studies will be required to elucidate the precise roles that all of the activin isoforms may play in regulating muscle growth and function in different physiological states. It is interesting to note, however, that circulating levels of activin A in humans have been shown to increase during aging, and conversely, circulating levels of inhibin B have been shown to decrease during aging (57,58,59,60,61), raising the intriguing possibility that enhanced activin signaling during aging may be a key contributing factor in the etiology of age-related sarcopenia. Understanding how muscle homeostasis is coordinately regulated by myostatin and by activins under both normal and pathological conditions will be essential for developing the most optimal strategies to tap the full potential of targeting this general signaling pathway to preserve muscle mass and prevent muscle atrophy in a variety of clinical settings associated with debilitating loss of muscle function.

Materials and Methods

Targeting constructs were generated from 129 SvJ genomic clones and used to transfect R1 embryonic stem cells (kindly provided by A. Nagy, R. Nagy, and W. Abramow-Newerly). Blastocyst injections of targeted clones were carried out by the Johns Hopkins Transgenic Core Facility. All mice were backcrossed at least six times onto a C57BL/6 background before analysis. All analysis was carried out on 10-wk-old mice, except for the force measurements and cardiotoxin studies, which were carried out on 14-wk-old mice. All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with protocols that were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine.

For measurement of muscle weights, muscles were dissected from both sides of the animal and weighed, and the average weight was used. For morphometric analysis, the gastrocnemius muscle was sectioned to its widest point using a cryostat, and fiber diameters were measured as the shortest width passing through the center of the fiber. Measurements were carried out on 84 type I fibers, 150 type IIa fibers, and 150 type IIb fibers per muscle, and mean fiber diameters for each type were calculated for each animal. For plotting the distribution of fiber sizes, data from all three mice in each group were pooled. Measurements were also carried out on 250 fibers of mixed types randomly selected from five representative areas of each section (every attempt was made to analyze the same five regions from muscle to muscle) to estimate overall mean fiber diameters.

For isolated muscle mechanics, mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine. Muscles were removed and placed in a bath of Ringers solution gas equilibrated with 95% O2/5% CO2. Sutures were attached to the distal and proximal tendons of the EDL and soleus muscles. Muscles were subjected to isolated mechanical measurements using a previously described apparatus (Aurora Scientific, Ontario, Canada) (62). After optimal length (Lo) was determined by supramaximal twitch stimulation, maximal isometric tetanus was measured in the muscles during a 500-msec stimulation. For histological analysis, samples were rinsed in PBS, blotted, weighed, covered in mounting medium before freezing in melting isopentane, and then stored at −80 C. Muscle cross-sectional areas were determined using the following formula: cross-sectional area = m/(Lo × L/Lo × 1.06 g/cm3), where m is muscle mass, Lo is muscle length, L/Lo is the ratio of fiber length to muscle length, and 1.06 is the density of muscle (63). L/Lo was 0.45 for EDL and 0.69 for soleus.

For muscle fiber typing, 10-μm frozen cross-sections taken from the midbelly of each muscle were subjected to immunohistochemistry for laminin (rabbit antilaminin Ab-1; Neomarkers, Fremont, CA) to outline the muscle fibers. Fiber typing was performed with antibodies recognizing myosin heavy chain (MHC)2a (SC-71), MHC 2b (BF-F3), and MHC 1 (BAF-8) as previously described (64). Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Images were acquired on an epifluorescence microscope (Leica, Deerfield, IL) and analyzed for the proportion of myosin-positive fibers using image analysis software (OpenLab, Improvision; Coventry, UK).

For skeletal muscle injury studies, 250 μl of cardiotoxin (10 μm Naja nigricollis; Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA) were injected into the gastrocnemius, and muscles were harvested 4 d or 21 d after induction of injury. Quantification of areas of fibrosis per area of muscle injury was performed using Nikon’s NIS elements BR3.0 software (Laboratory Imaging; Nikon, Melville, NY).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Charles Hawkins and Ann Lawler (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine) for carrying out the blastocyst injections and embryo transfers and Zuozhen Tian and Magdalena Sikora (University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine) for performing the isolated muscle functional tests.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01AR059685 (to S.-J.L.), R01AR060636 (to S.-J.L.), DP2OD004515 (to R.D.C.), K08NS055879 (to R.D.C.), R01HD32067 (to M.M.M.), and U54AR052646 (to S.-J.L. and E.R.B.); Muscular Dystrophy Association Grants MDA10065 (to S.-J.L.) and MDA101938 (to R.D.C.), and a gift from Merck Research Laboratories (to S.-J.L.).

Disclosure Summary: Under a licensing agreement between MetaMorphix, Inc. (MMI) and the Johns Hopkins University, S.-J.L. is entitled to a share of royalty received by the University on sales of the factors described in this paper. S.J.L. and the University own MMI stock, which is subject to certain restrictions under University policy. S-J.L., who is the scientific founder of MMI, is a consultant to MMI on research areas related to the study described in this paper. The terms of these arrangements are being managed by the University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies. Y.-.S.L., T.Z., A.S., M.M., K.T., R.D., and E.B. have nothing to declare.

First Published Online September 1, 2010

Abbreviations: EDL, Extensor digitorum longus; FSTL-3, follistatin-like 3; GDF, growth differentiation factor; MHC, myosin heavy chain.

References

- McPherron AC, Lawler AM, Lee SJ 1997 Regulation of skeletal muscle mass in mice by a new TGF-β superfamily member. Nature 387:83–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grobet L, Pirottin D, Farnir F, Poncelet D, Royo LJ, Brouwers B, Christians D, Desmecht D, Coignoul F, Kahn R, Georges M 2003 Modulating skeletal muscle mass by postnatal, muscle-specific inactivation gene. Genesis 35:227–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welle S, Bhatt K, Pinkert CA, Tawil R, Thornton CA 2007 Muscle growth after postdevelopmental myostatin gene knockout. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292:E985–E991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanovich S, Krag TO, Barton ER, Morris LD, Whittemore LA, Ahima RS, Khurana TS 2002 Functional improvement of dystrophic muscle by myostatin blockade. Nature 420:418–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore LA, Song K, Li X, Aghajanian J, Davies MV, Girgenrath S, Hill JJ, Jalenak M, Kelley P, Knight A, Maylor R, O'Hara D, Pearson A, Quazi A, Ryerson S, Tan XY, Tomkinson KN, Veldman GM, Widom A, Wright JF, Wudyka S, Zhao L, Wolfman NM 2003 Inhibition of myostatin in adult mice increases skeletal muscle mass and strength. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 300:965–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfman NM, McPherron AC, Pappano WN, Davies MV, Song K, Tomkinson KN, Wright JF, Zhao L, Sebald SM, Greenspan DS, Lee SJ 2003 Activation of latent myostatin by the BMP-1/tolloid family of metalloproteinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:15842–15846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Reed LA, Davies MV, Girgenrath S, Goad ME, Tomkinson KN, Wright JF, Barker C, Ehrmantraut G, Holmstrom J, Trowell B, Gertz B, Jiang MS, Sebald SM, Matzuk M, Li E, Liang LF, Quattlebaum E, Stotish RL, Wolfman NM 2005 Regulation of muscle growth by multiple ligands signaling through activin type II receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:18117–18122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grobet L, Martin LJ, Poncelet D, Pirottin D, Brouwers B, Riquet J, Schoeberlein A, Dunner S, Ménissier F, Massabanda J, Fries R, Hanset R, Georges M 1997 A deletion in the bovine myostatin gene causes the double-muscled phenotype in cattle. Nat Genet 17:71–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambadur R, Sharma M, Smith TP, Bass JJ 1997 Mutations in myostatin (GDF8) in double-muscled Belgian Blue and Piedmontese cattle. Genome Res 7:910–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherron AC, Lee SJ 1997 Double muscling in cattle due to mutations in the myostatin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:12457–12461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grobet L, Poncelet D, Royo LJ, Brouwers B, Pirottin D, Michaux C, Ménissier F, Zanotti M, Dunner S, Georges M 1998 Molecular definition of an allelic series of mutations disrupting the myostatin function and causing double-muscling in cattle. Mamm Genome 9:210–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clop A, Marcq F, Takeda H, Pirottin D, Tordoir X, Bibé B, Bouix J, Caiment F, Elsen JM, Eychenne F, Larzul C, Laville E, Meish F, Milenkovic D, Tobin J, Charlier C, Georges M 2006 A mutation creating a potential illegitimate microRNA target site in the myostatin gene affects muscularity in sheep. Nat Genet 38:813–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher DS, Quignon P, Bustamante CD, Sutter NB, Mellersh CS, Parker HG, Ostrander EA 2007 A mutation in the myostatin gene increases muscle mass and enhances racing performance in heterozygote dogs. PLoS Genet 3:779–786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuelke M, Wagner KR, Stolz LE, Hübner C, Riebel T, Kömen W, Braun T, Tobin JF, Lee SJ 2004 Myostatin mutation associated with gross muscle hypertrophy in a child. N Engl J Med 350:2682–2688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ 2004 Regulation of muscle mass by myostatin. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 20:61–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchida K 2008 Targeting myostatin for therapies against muscle-wasting disorders. Curr Opin Drug Discov Dev 11:487–494 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodino-Klapac LR, Haidet AM, Kota J, Handy C, Kaspar BK, Mendell JR 2009 Inhibition of myostatin with emphasis on follistatin as a therapy for muscle disease. Muscle Nerve 39:283–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, McPherron AC 2001 Regulation of myostatin activity and muscle growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:9306–9311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmers TA, Davies MV, Koniaris LG, Haynes P, Esquela AF, Tomkinson KN, McPherron AC, Wolfman NM, Lee SJ 2002 Induction of cachexia in mice by systemically administered myostatin. Science 296:1486–1488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amthor H, Nicholas G, McKinnell I, Kemp CF, Sharma M, Kambadur R, Patel K 2004 Follistatin complexes myostatin and antagonises myostatin-mediated inhibition of myogenesis. Dev Biol 270:19–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ 2007 Quadrupling muscle mass in mice by targeting TGF-β signaling pathways. PLoS One 2:e789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidet AM, Rizo L, Handy C, Umapathi P, Eagle A, Shilling C, Boue D, Martin PT, Sahenk Z, Mendell JR, Kaspar BK 2008 Long-term enhancement of skeletal muscle mass and strength by single gene administration of myostatin inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:4318–4322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzuk MM, Lu N, Vogel H, Sellheyer K, Roop DR, Bradley A 1995 Multiple defects and perinatal death in mice deficient in follistatin. Nature 374:360–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girgenrath S, Song K, Whittemore LA 2005 Loss of myostatin expression alters fiber-type distribution and expression of myosin heavy chain isoforms in slow- and fast-type skeletal muscle. Muscle Nerve 31:34–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amthor H, Macharia R, Navarrete R, Schuelke M, Brown SC, Otto A, Voit T, Muntoni F, Vrbóva G, Partridge T, Zammit P, Bunger L, Patel K 2007 Lack of myostatin results in excessive muscle growth but impaired force generation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:1835–1840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherron AC, Huynh TV, Lee SJ 2009 Redundancy of myostatin and growth/differentiation factor 11. BMC Dev Biol 9:24–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morine KJ, Bish LT, Pendrak K, Sleeper MM, Barton ER, Sweeney HL 2010 Systemic myostatin inhibition via liver-targeted gene transfer in normal and dystrophic mice. PLoS One 5:e9176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCroskery S, Thomas M, Platt L, Hennebry A, Nishimura T, McLeay L, Sharma M, Kambadur R 2005 Improved muscle healing through enhanced regeneration and reduce fibrosis in myostatin-null mice. J Cell Sci 118:3531–3541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner KR, Liu X, Chang X, Allen RE 2005 Muscle regeneration in the prolonged absence of myostatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:2519–2524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Li Y, Shen W, Qiao C, Ambrosio F, Lavasani M, Nozaki M, Branca MF, Huard J 2007 Relationships between transforming growth factor-β1, myostatin, and decorin. J Biol Chem 282:25852–25863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JJ, Davies MV, Pearson AA, Wang JH, Hewick RM, Wolfman NM, Qiu Y 2002 The myostatin propeptide and the follistatin-related gene are inhibitory binding proteins of myostatin in normal serum. J Biol Chem 277:40735–40741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A, Sidis Y, Mahan A, Raher MJ, Xia Y, Rosen ED, Bloch KD, Thomas MK, Schneyer AL 2007 FSTL3 deletion reveals roles for TGF-β family ligands in glucose and fat homeostasis in adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:1348–1353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakso M, Pichel JG, Gorman JR, Sauer B, Okamoto Y, Lee E, Alt FW, Westphal H 1996 Efficient in vivo manipulation of mouse genomic sequences at the zygote stage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:5860–5865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H, Brown CW, Matzuk MM 2002 Genetic analysis of the mammalian transforming growth factor-β superfamily. Endocr Rev 23:787–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas A, Heldin CH 2009 The regulation of TGFβ signal transduction. Development 136:3699–3714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BA, Nishi R 1997 Opposing effects of activin A and follistatin on developing skeletal muscle cells. Exp Cell Res 233:350–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Vichev K, Macharia R, Huang R, Christ B, Patel K, Amthor H 2005 Activin A inhibits formation of skeletal muscle during chick development. Anat Embryol (Berl) 209:401–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza TA, Chen X, Guo Y, Sava P, Zhang J, Hill JJ, Yaworsky PJ, Qiu Y 2008 Proteomic identification and functional validation of activins and bone morphogenetic 11 as candidate novel muscle mass regulators. Mol Endocrinol 22:2689–2702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trendelenburg AU, Meyer A, Rohner D, Boyle J, Hatakeyama S, Glass DJ 2009 Myostatin reduces Akt/TORC1/p70S6K signaling, inhibiting myoblast differentiation and myotube size. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 296:C1258–C1270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson H, Schakman O, Kalista S, Lause P, Tsuchida K, Thissen JP 2009 Follistatin induces muscle hypertrophy through satellite cell proliferation and inhibition of both myostatin and activin. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 297:E157–E164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrewe H, Gendron-Maguire M, Harbison ML, Gridley T 1994 Mice homozygous for a null mutation of activin βB are viable and fertile. Mech Dev 47:43–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassalli A, Matzuk MM, Gardner HA, Lee KF, Jaenisch R 1994 Activin/inhibin βB subunit gene disruption leads to defects in eyelid development and female reproduction. Genes Dev 8:414–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzuk MM, Kumar TR, Vassalli A, Bickenbach JR, Roop DR, Jaenisch R, Bradley A 1995 Functional analysis of activins during development. Nature 374:354–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AL, Kumar TR, Nishimori K, Bonadio J, Matzuk MM 2000 Activin βC and βE genes are not essential for mouse liver growth, differentiation, and regeneration. Mol Cell Biol 20:6127–6137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadena SM, Tomkinson KN, Monnell TE, Spaits MS, Kumar R, Underwood KW, Pearsall RS, and Lachey JL 13 May 2010 Administration of a soluble activin type IIB receptor promotes skeletal muscle growth independent of fiber type. J Appl Physiol 10.1152/japplphysiol.00866.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchida K, Arai KY, Kuramoto Y, Yamakawa N, Hasegawa Y, Sugino H 2000 Identification and characterization of a novel follistatin-like protein as a binding protein for the TGF-β family. J Biol Chem 275:40788–40796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguer-Satta V, Bartholin L, Jeanpierre S, Gadoux M, Bertrand S, Martel S, Magaud JP, Rimokh R 2001 Expression of FLRG, a novel activin A ligand, is regulated by TGF-β and during hematopoiesis [corrected]. Exp Hematol 29:301–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneyer A, Schoen A, Quigg A, Sidis Y 2003 Differential binding and neutralization of activins A and B by follistatin and follistatin like-3 (FSTL-3/FSRP/FLRG). Endocrinology 144:1671–1674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebbapragada A, Benchabane H, Wrana JL, Celeste AJ, Attisano L 2003 Myostatin signals through a transforming growth factor β-like signaling pathway to block adipogenesis. Mol Cell Biol 23:7230–7242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamer LW, Wolfman NM, Celeste AJ, Hattersley G, Hewick R, Rosen V 1999 A novel BMP expressed in developing mouse limb, spinal cord, and tail bud is a potent mesoderm inducer in Xenopus embryos. Dev Biol 208:222–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherron AC, Lawler AM, Lee SJ 1999 Regulation of anterior/posterior patterning of the axial skeleton by growth/differentiation factor 11. Nat Genet 22:260–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kretser DM, Hedger MP, Loveland KL, Phillips DJ 2002 Inhibins, activins and follistatin in reproduction. Hum Reprod Update 8:529–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilezikjian LM, Blount AL, Donaldson CJ, Vale WW 2006 Pituitary actions of ligands of the TGF-β family: activins and inhibins. Reproduction 132:207–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y, Schneyer AL 2009 The biology of activin: recent advances in structure, regulation and function. J Endocrinol 202:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson DM, Burger HG 2002 Reproductive hormones: ageing and the perimenopause. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 81:612–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz JM, Santoro N 2004 Inhibins, activins, and follistatin in the aging female and male. Semin Reprod Med 22:209–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenover JS, McLachlan RI, Dahl KD, Burger HG, de Kretser DM, Bremner WJ 1988 Decreased serum inhibin levels in normal elderly men: evidence for a decline in Sertoli cell function with aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 67:455–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNaughton JA, Bangah ML, McCloud PI, Burger HG 1991 Inhibin and age in men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 35:341–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loria P, Petraglia F, Concari M, Bertolotti M, Martella P, Luisi S, Grisolia C, Foresta C, Volpe A, Genazzani AR, Carulli N 1998 Influence of age and sex on serum concentrations of total dimeric activin A. Eur J Endocrinol 139:487–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccarelli A, Morpurgo PS, Corsi A, Vaghi I, Fanelli M, Cremonesi G, Vaninetti S, Beck-Peccoz P, Spada A 2001 Activin A serum levels and aging of the pituitary-gonadal axis: a cross-sectional study in middle-aged and elderly healthy subjects. Exp Gerontol 36:1403–1412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohring C, Krause W 2003 Serum levels of inhibin B in men of different age groups. The Aging Male 6:73–78 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton ER, Morris L, Kawana M, Bish LT, Toursel T 2005 Systemic administration of L-arginine benefits mdx skeletal muscle function. Muscle Nerve 32:751–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SV, Faulkner JA 1988 Contractile properties of skeletal muscles from young, adult and aged mice. J Physiol 404:71–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiaffino S, Salviati G 1997 Molecular diversity of myofibrillar proteins: isoforms analysis at the protein and mRNA level. Methods Cell Biol 52:349–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.