Abstract

Mutations in the aldolase B gene (ALDOB) impairing enzyme activity toward fructose-1-phosphate cleavage cause hereditary fructose intolerance (HFI). Diagnosis of the disease is possible by identifying known mutant ALDOB alleles in suspected patients; however, the frequencies of mutant alleles can differ by population. Here, 153 American HFI patients with 268 independent alleles were analyzed to identify the prevalence of seven known HFI-causing alleles (A149P, A174D, N334K, Δ4E4, R59Op, A337V, and L256P) in this population. Allele-specific oligonucleotide hybridization analysis was performed on polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-amplified genomic DNA from these patients. In the American population, the missense mutations A149P and A174D are the two most common alleles, with frequencies of 44% and 9%, respectively. In addition, the nonsense mutations Δ4E4 and R59Op are the next most common alleles, with each having a frequency of 4%. Together, the frequencies of all seven alleles make up 65% of HFI-causing alleles in this population. Worldwide, these same alleles make up 82% of HFI-causing mutations. This difference indicates that screening for common HFI alleles is more difficult in the American population. Nevertheless, a genetic screen for diagnosing HFI in America can be improved by including all seven alleles studied here. Lastly, identification of HFI patients presenting with classic symptoms and who have homozygous null genotypes indicates that aldolase B is not required for proper development or metabolic maintenance.

Introduction

Hereditary fructose intolerance (HFI) is an autosomal recessive metabolic disease caused by a deficiency of aldolase B (EC 4.1.2.13) activity in the liver, kidney, and small intestine (Hers and Joassin 1961), in which tissues this enzyme is crucial for metabolism of ingested fructose. The disease first appears in infancy after weaning when fructose-containing foods are introduced. The incidence rate of HFI is between 10−4 and 10−5 and varies among ethnic populations (Gitzelmann and Baerlocher 1973; James et al. 1996; Santer et al. 2005; Gruchota et al. 2006). Based on this, a carrier frequency is predicted between 1:55 and 1:120. A more accurate carrier frequency is difficult to estimate given that a large number of children and adults likely are living undiagnosed in the general population (Cox 1988). Symptoms vary and generally include abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea following fructose ingestion. Infants may present with a general failure to thrive. Heavy and/or persistent intake of the sugar can lead to hypoglycemia, jaundice, progressive cirrhosis of the liver, renal tubular failure, metabolic acidosis, seizures, coma, and eventually death (Morris 1968; Baerlocher et al. 1978; Laméire et al. 1978; Odiévre et al. 1978; Cox 1993; Steinmann et al. 2001). In order to treat the disease and alleviate symptoms, fructose must be removed from the diet. Complete exclusion of fructose is often difficult and a constant daily risk remains for fructose-intolerant individuals due to the widespread use of fructose as a commercial sweetener and as a component of some medicines, including parenteral infusions (Ali et al. 1993).

The consequences of fructose ingestion for HFI patients are most dire for the newborn infant whose parents are unaware of the disorder and may coerce the persistent ingestion of the sugar, making weaning during infancy the period of greatest risk. Those individuals that survive develop a permanent and powerful protective aversion to sweet-tasting foods (Odiévre et al. 1978). However, later in life, acute exposure to the noxious sugar can lead to liver failure and death (Heine et al. 1969; Schulte and Lenz 1977; Hackl et al. 1978; Cox 1993). It is therefore crucial to make an accurate diagnosis as early as possible.

HFI should not be confused with fructose malabsorption, an uncomfortable yet benign compilation of symptoms occurring in approximately a third of adults (Beyer et al. 2005). The underlying cause of the malabsorption is unclear. It was originally hypothesized that malabsorption was the result of mutations in glut5, the fructose-specific facultative transporter responsible for transporting fructose from the small intestine (Kayano et al. 1990). However, sequence analysis of glut5 in patients with fructose malabsorption failed to identify any mutations (Wasserman et al. 1996). Diagnosis of fructose malabsorption is often done using a hydrogen breath test (Choi et al. 2003; Gomara et al. 2008). It is important to emphasize that this test that can be dangerous to those suffering from HFI and should be used with caution only after a careful dietary history has been taken (Muller et al. 2003). The only relationship between HFI and fructose malabsorption is in the treatment, whereby exclusion of the offending sugar from the diet should alleviate symptoms. In fact, if mutations in the transporters (GLUT5 or GLUT2) did exist, this might protect people with HFI from any significant pathology.

There are two standard diagnostic methods for HFI. One is the direct assay of aldolase B activity in liver biopsy samples taken from suspected HFI patients. Another monitors the levels of specific metabolites in the blood following an intravenous fructose challenge in which HFI patients show a distinct profile (Laméire et al. 1978; Steinmann and Gitzelmann 1981). Although these two tests are diagnostic, they are relatively invasive and are often precluded by the severity of the presenting symptoms. It is important to note that the increased use of the hydrogen breath test following oral fructose ingestion is not diagnostic and may even be dangerous for those suffering from HFI (Muller et al. 2003).

A noninvasive genetic test has been developed to screen patient DNA for the most common and widespread alleles that are known to cause the disease. This test utilizes allele-specific oligonucleotide (ASO) hybridization of polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-amplified genomic DNA isolated from a small blood sample (Tolan and Brooks 1992). The missense mutation A149P was the first HFI allele reported (Cross et al. 1988) and accounts for the majority of HFI alleles (Tolan and Brooks 1992). Another mutation, A174D, was discovered shortly thereafter and is the second most common allele (Cross et al. 1990a; Tolan and Brooks 1992). Identified in 1992, the third most common allele is N334K (Cross et al. 1990b). Together, these three alleles comprised 68% of HFI alleles worldwide (Tolan and Brooks 1992) and have been included in a standard DNA-based genetic test for HFI (Caciotti et al. 2008). This genetic test is highly dependent, however, on the population being tested. Its diagnostic power is highest in the northern European population (Tolan 1995), for which allele frequencies have been the most commonly reported (Santer et al. 2005).

Improving the genetic screen for American HFI patients by defining as many common alleles as possible among this group would aid in prompt and accurate diagnosis. Such an analysis of common alleles in an American population has not been reported for more than 15 years (Tolan and Brooks 1992). Analysis of 153 American HFI patients harboring 268 independent alleles is the largest study reported for any population. The updated allele frequencies revealed two nonsense mutations in the aldolase B gene (Δ4E4 and R59Op) that are more common than previously thought. It is recommended that a diagnostic test in the American population should include analysis of these alleles. Moreover, the identification of multiple patients with unremarkable phenotypes that are homozygous for these null alleles suggests that aldolase B is not critically required for proper development.

Materials and methods

Patients

This study involved 153 HFI patients from 131 families from Argentina, Brazil, Canada, and the United States. The fraction of families from the United States was 84%. HFI was diagnosed in all patients by either direct assay of aldolase B activity in the liver, intravenous fructose challenge, or an HFI genotype combined with clinical symptoms consistent with HFI. Specific genotypes of four probands are reported. One patient was Canadian of Iranian descent. This patient showed hepatomegaly and vomiting at weaning, with a positive test for HFI from a liver biopsy. A second Caucasian was from the USA and of Irish descent. This patient was diagnosed well into adulthood following a lifetime aversion to sweets. A third patient was from the USA and tested positive for HFI following a liver biopsy. A fourth patient was of Native American descent and was diagnosed by both a liver biopsy and fructose tolerance test. Informed consent was obtained from all patients, as approved by the Institutional Review Board.

DNA isolation and PCR

Genomic DNA was extracted from leukocytes isolated from whole blood, as described previously (Orkin et al. 1978). Aldolase B exons 3, 4, 5, 7, and 9 were amplified by PCR (Saiki et al. 1985) using the exon-specific primers, the optimized magnesium chloride (MgCl2) concentrations, and the annealing temperatures described in Table 1. Cycling conditions were as follows: 94°C for 5 min; (42–55°C for 1 min; 72°C for 1 min; 94°C for 1.5 min) repeated for five cycles; (94°C for 1.5 min, 42–55°C for 1 min; 72°C for 3 min) repeated for 25 cycles; 72°C for 10 min; hold at 4°C.

Table 1.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification conditions for aldolase B exons

| Exon | Direction | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′) | Expected size (bp) | Annealing temperature (°C) | [MgCl2] (mM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | F R |

CTAGCCACCTGAGAGCAACC TCTCTGTGGGAAGATGACG |

540 | 55 | 2.5 |

| 4 | F R |

GATGCAAACTGTTAGTTAG GCCTTCATTTCTAGCTTACA |

190 | 55 | 2.5 |

| 5 | F R |

ACTCCTTCCCTTTATTA GGTCCATTTGTAGTTATAGT |

330 | 42 | 4 |

| 7 | F R |

CTGCAGTGTAAATGTGCCAA GCTTGGTATTCTGAAGTG |

410 | 52 | 2.5 |

| 9 | F R |

TTCCCATGAGAGGCAGA GACCTTTACTGTTGAAACCC |

711 | 55 | 3.75 |

F sequence similar to messenger RNA (mRNA), R sequence complementary to mRNA

Control clones

Plasmids containing DNA inserts with either wild-type or mutant allele sequence were used as controls for screening. Each control insert was amplified from genotyped patient genomic DNA, and the appropriate PCR-amplified exons were cloned into the TOPO TA cloning vector (Invitrogen). All control clones were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Allele-specific oligonucleotide (ASO) hybridization

Amplified patient DNA (50–100 ng) and cloned control DNA were denatured and applied to a nylon membrane (Zeta Probe, BioRad), as per manufacturer’s instructions, using a dot-blot apparatus (BioRad). Blots were prehybridized at 37°C in prehybridization buffer [5× sodium saline citrate (SSC), 20 mM sodium phosphate (NaH2PO4), pH 7.2, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetate (EDTA), 7% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 10× Denhardt’s solution). Allele-specific ASO for wild-type and mutant sequences were radioactively labeled at the 5′-end with γ-[32P]adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and polynucleotide kinase (Sambrook et al. 1989). Individual ASOs were added to each blot and incubated at 30–37°C for >1 h. Low-stringency washes were performed in 5× SSC/0.1% SDS at room temperature, followed by autoradiography to confirm hybridization. High-stringency washes were performed in the aforementioned wash solution at the appropriate discriminatory temperatures, followed by autoradiography. Probe sequences and corresponding discriminatory temperatures are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Allele-specific oligo-nucleotides used for dot-blot analysis

| Exon | Mutationa | Allele | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Discriminatory temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | R59Op | wt | GGCAGTTCCGAGAAATCC | 66 |

| mut | GGCAGTTCTGAGAAATCC | 66 | ||

| 4 | Δ4E4 | wt | GCAGGAACAAACAAAGAAAC | 66 |

| mut | GCAGGAACAAAGAAACCACC | 66 | ||

| 5 | A149P | wt | AAGTGGCGTGCTGTGCTGA | 67 |

| mut | AAGTGGCGTCCTGTGCTGA | 67 | ||

| 5 | A174D | wt | TCGCTACGCCAGCATCT | 59 |

| mut | AGATGCTGTCGTAGCGA | 59 | ||

| 7 | L256P | wt | AACAGCTCTCCACCGTA | 58 |

| mut | AACAGCTCCCCACCGTA | 60 | ||

| 9 | N334K | wt | GCTAACTGCCAGGCGG | 64 |

| mut | GCTAAGTGCCAGGCGG | 64 | ||

| 9 | A337V | wt | ACTGCCAGGCGGCCAAAG | 67 |

| mut | ACTGCCAGGTGGCCAAAG | 65 |

wt wild-type DNA sequence, mut mutant DNA sequence

Trivial names (see Table 3)

Results and discussion

HFI alleles in the American population

The 153 American HFI patients included in this study were screened for mutations A149P, A174D, and N334K, which are the most common HFI alleles in the European population (Cox 1994). In 1992, the frequencies of these three alleles in 31 North American HFI individuals together accounted for 68% of the HFI alleles (Tolan and Brooks 1992). In this larger population of 153 unrelated American patients, these same three alleles accounted for only 55% (Table 3). The decrease in the overall frequency of these three mutations likely was due to a more appropriate sampling of the American population. Whereas individuals in the previous study were predominantly of northern European extraction, ethnicities of the individuals reported here were Caucasian (68%), Hispanic (18%), African American (14%), Asian American (3%), and Native American (2%). This cross-section accurately represents the ethnic demographic of the United States (American Community Survey 2006).

Table 3.

Allele frequencies in the American hereditary fructose intolerance (HFI) population

| Trivial namea | Systematic name (cDNA based) | Independent alleles | Frequency in 268 allelesb | Frequency in 47 allelesc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A149P | c.448G>C | 117 | 44% | 55% |

| A174D | c.524C>A | 23 | 9% | 11% |

| N334K | c.1005C>G | 5 | 2% | 2% |

| Δ4E4 | c.360-363delCAAA | 12 | 4% | nd |

| R59Op | c.178C>T | 10 | 4% | nd |

| L256P | c.770T>C | 4 | 1% | nd |

| A337V | c.1013C>T | 3 | 1% | nd |

| Other | 3 | 1% | 4% | |

| Unknown | 91 | 34% | 28% |

nd not determined

Trivial names based on nomenclature in original publications;

this report;

Given that 46% of the alleles in this population were still unidentified, screening for four additional known HFI mutations was undertaken (Δ4E4, R59Op, A337V, and L256P). There were indications from the literature that these four alleles may be more common than previously thought. The nonsense mutation Δ4E4 was first identified as a private mutation in a British patient (Dazzo and Tolan 1990) but was later identified in many reports from Italian (Santamaria et al. 1993, 1996), North American (Ali and Cox 1995), German (Santer et al. 2005), and Chinese (Chi et al. 2007) patients. Another nonsense mutation, R59Op, was initially described as widespread (Brooks and Tolan 1994), which was confirmed by reports of patients from Germany (Ali et al. 1994b; Santer et al. 2005) and France (Davit-Spraul et al. 2008). In this same report from France, A337V had a frequency of 3% among a cohort of 92 French HFI families. Lastly, L256P has been reported in the Italian population (Ali et al. 1994a; Santamaria et al. 1999; Stormon et al. 2003). Analysis for these four mutations was performed on the 153 American HFI patients using ASO hybridization. These four mutations occurred in 30 alleles, accounting for a combined frequency of 10% (Table 3).

One important finding in the American population is that the frequencies of both the Δ4E4 and R59Op alleles were greater than that of N334K. These two mutations are now the third and fourth most common alleles, respectively. Whereas A149P and A174D remain the major HFI-causing mutations in the American population, their frequency was less than previously reported (Tolan and Brooks 1992). The N334K allele, on the other hand, showed no change. Combined, the prevalence of these seven mutations in this American population equaled 65%. Despite this larger number of widespread mutations, 34% of alleles remain unknown, which is similar to what was seen by Tolan and Brooks (1992) (28%). Clearly, more work is required for a complete picture of the mutational spectrum for HFI in this diverse American population.

HFI alleles worldwide

This analysis of 268 alleles in American HFI patients represents the largest report of its kind on any single population. Table 4 enumerates the alleles from this study and other reports in the literature in the American population and compares them with studies in other populations worldwide compiled from published reports on HFI genotypes. Whereas A149P remains the most common HFI allele across all populations, there were differences in the distribution of other alleles. Overall, A174D and N334K remained the second and third most common alleles worldwide, except in the American population, where the Δ4E4 and R59Op alleles were the third and fourth most common alleles. Interestingly, Δ4E4 was the second most common allele in Spain (surpassing both A174D and N334K), and N334K was the second most common allele in Yugoslavia.

Table 4.

Worldwide distribution of HFI alleles

| Country | Alleles | A149P | A174D | N334K | Δ4E4 | R59Op | L256P | A337V | Other | Unknown | D.I.a | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| America | 275 | 119 | 25 | 5 | 13 | 10 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 92 | 79 | b |

| France | 268 | 179 | 39 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 17 | 12 | 98 | c | |

| Germany | 150 | 97 | 16 | 11 | 4 | 2 | 13 | 7 | 97 | d | ||

| Italy | 119 | 48 | 27 | 8 | 7 | 2 | 19 | 8 | 91 | e | ||

| UK | 60 | 43 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 100 | f | |||

| Poland | 52 | 35 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 93 | Gruchota et al. 2006 | ||||

| Spain | 43 | 29 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 96 | Sanchez-Gutierrez et al. 2002 | ||||

| Switzerland | 33 | 20 | 10 | 3 | 99 | g | ||||||

| Turkey | 16 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 98 | h | ||||

| Yugoslavia | 14 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 100 | i | ||||||

| Austria | 6 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 90 | j | |||||

| Norway | 4 | 4 | 100 | Larsen et al. 1994 | ||||||||

| Israel | 4 | 3 | 1 | 94 | Cox 1994 | |||||||

| Finland | 2 | 1 | 1 | 100 | Ali et al. 1998 | |||||||

| Middle East | 2 | 1 | 1 | 100 | k | |||||||

| Australia | 2 | 2 | 100 | Wilson et al. 1995 | ||||||||

| N. Zealand | 2 | 1 | 1 | 75 | Ali et al. 1996 | |||||||

| Portugal | 2 | 1 | 1 | 75 | Lopes et al. 1997 | |||||||

| India | 2 | 1 | 1 | - | l | |||||||

| China | 1 | 1 | 100 | Chi et al. 2007 | ||||||||

| Japan | 1 | 1 | - | Kajihara et al. 1990 | ||||||||

| Totals | 1058 | 601 | 137 | 50 | 37 | 19 | 6 | 10 | 72 | 126 | ||

| Frequency | 0.57 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 94 |

Diagnostic index calculated for three alleles (A149P, A174D, N334K) and expressed as a percentage;

This study, Kaiser and Hegele 1991; Ali and Cox 1995;

Cross and Cox 1990; Cross et al. 1990a; Ali et al. 1994b; Cox 1994; Costa et al. 1998; Davit-Spraul et al. 2008;

Cross et al. 1990a; Sebastio et al. 1991; Ali et al. 1993; Santamaria et al. 1993; Ali et al. 1994a; Santamaria et al. 1996; Santamaria et al. 1999; Esposito et al. 2004; Caciotti et al. 2008;

Cross et al. 1988; Cox 1990b; Cross et al. 1990a; Dazzo and Tolan 1990; de Souza et al. 1990; Cox 1994; Ali et al. 1998; Kullberg-Lindh et al. 2002; Kriegshauser et al. 2007;

D. Tolan, unpublished data.

Diagnosis of HFI based on allele frequencies

Genetic testing is a valuable, noninvasive method for diagnosing HFI, and establishing the prevalence of known alleles for any given population can aid in accurate diagnosis. A “diagnostic index” can be defined as the probability of finding at least one HFI allele in a symptomatic individual in a given screen. If a 90% chance of finding at least one HFI allele in a genetic screen is used as the definition of a diagnostic test, then the value of genetic screening for HFI diagnosis in different countries can be assessed. For example, in the United Kingdom, the single A149P mutation made up 72% of the HFI alleles, and screening for this one mutant allele gives a diagnostic index of 92% (p=0.72; p2+2pq=0.722+2×0.72×0.28= 0.92). Therefore, screening for only this single allele would be diagnostic in this population. Worldwide, however, A149P represented only 57% of alleles known to cause the disease, and screening for only this allele gives a diagnostic index of 82%, which would culminate in numerous false-negative results. Diagnosis can be improved to more than 90% in most populations, except in America, by routinely including two other common alleles, A174D and N334K, in the genetic screen. Table 4 calculates the diagnostic index when screening for the three most common alleles worldwide (A149P, A174D, and N334K) for each country. America was the only population in which screening for these alleles, or even for the seven most common alleles (see Table 3), results in a diagnostic index of <90% (88%). Perhaps identification of other common HFI alleles in this population and their inclusion in an expanded genetic screen would improve diagnosis in the Americas. Countries such as New Zealand, Portugal, India, and Japan did not have enough published reports to accurately define alleles common to these populations.

Furthermore, this analysis revealed several alleles that were specific to certain populations (Table 4). The L256P and A337V alleles seem more specific to Italy and France, respectively, which is consistent with previous reports (Santamaria et al. 1996; Davit-Spraul et al. 2008). In contrast, the Δ4E4 and R59Op alleles were very widespread, as they have appeared in a number of populations across the world. Defining an accurate mutational spectrum for different populations can aid in diagnosis using targeted mutation analysis. When a clinician suspects a patient with HFI by clinical/dietary history, consideration of their ethnic background should be incorporated for diagnosing the disease by a DNA-based test. The clinician can send the blood sample to a lab that has established a screen for alleles common to that population. For example, if the patient’s ancestry originates from the UK, screening for A149P would be sufficient; however, for a patient with Italian ancestry, screening for at least three to five of the most common alleles would be more beneficial.

As mentioned above, some countries had very few reports of HFI genotypes, with none having been reported in Africa. This was likely either due to a decrease in the incidence of HFI in these populations or the lack of overall diagnosis. Perhaps in some countries, where the consumption of sugars in the diet is less than that in Western diets, the disease symptoms do not manifest (Cox 1990a, 2002).

Identification of null genotypes

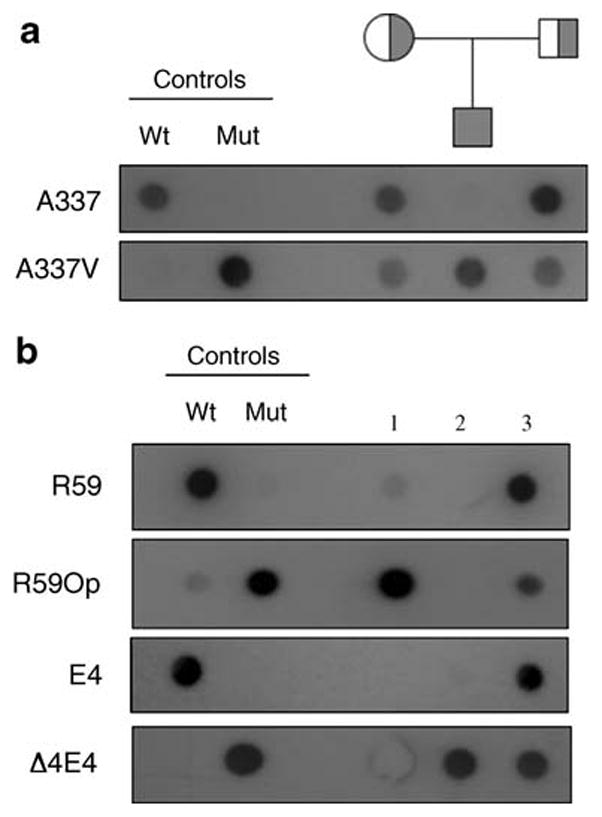

Of particular interest was the identification of patients homozygous for three of the once-considered rare mutations screened in this study (Δ4E4, R59Op, and A337V) (Fig. 1). ASO hybridization analysis of exon 9 with ASO primers for A337V (Tables 1 and 2) identified an A337V homozygous patient from a nonconsanguineous lineage (Fig. 1a). Similar ASO analysis was done for R59Op and Δ4E4. Two patients were identified as homozygous for these null alleles, and one was a compound heterozygote for these two alleles (Fig. 1b). The presence of these two relatively uncommon alleles in one patient suggests that they may be more prevalent in the American HFI population than observed in this study. This hypothesis can be tested by calculating carrier frequencies based on number of homozygote genotypes for these alleles. Predicted number of genotypes based on the frequencies of homozygotes was compared with the observed genotype frequency to predict carriers and homozygotes for each of the common American HFI alleles (Table 5). The expected versus observed genotype frequency for all Americans in which homozygotes appear indicated that whereas the less common alleles (Δ4E4, N334K, and R59Op) are in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p>0.05), the A149P and A174D alleles are not in equilibrium (p<0.05). For these two alleles, far fewer heterozygotes and far more homozygotes were observed than predicted by Hardy-Weinberg. This loss of heterozygosity could suggest heterozygotes are selected against, although this is not likely, as even null homozygotes have the same phenotype as all other HFI patients (see below). However, some dominant negative effects cannot be ruled out. The observed increase in A149P and A174D homozygotes is likely due to positive assortive mating in ethnic groups where there are cultural preferences in which the choice of mates is not random.

Fig. 1.

Allele-specific oligonucleotide dot-blot analysis performed on four American HFI patients. Panel A: The proband and parents denoted by the pedigree and control DNAs were screened for the presence of the A337V mutant allele. Wild-type (A337) and mutant (A337V) ASOs (10 ng) were 5′-end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and hybridized to blots containing 100 ng of exon 9 PCR-amplified genomic or control plasmid (Wt and Mut) DNA. Blots were washed at 67°C and 65°C, respectively, and exposed for 1 d and 7 d, respectively. Panel B: Three patients were screened for the presence of the R59Op and Δ4E4 mutant alleles. Wild-type and mutant ASOs for each allele as noted on the left were 5′-end labeled with [γ-32P] ATP and hybridized to 100 ng of exon 3 (patients 1 and 3) or exon 4 (patients 2 and 3) PCR-amplified genomic or control plasmid (Wt and Mut) DNA. Blots were washed at 66°C and blots exposed for 1 d (R59, R59Op, E4) or 5 h (Δ4E4)

Table 5.

Genotype frequencies for common alleles in the American hereditary fructose intolerance (HFI) populationa

| Allele | Genotype | Expected frequencyb | Observed frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| A149P | p2 | 26 | 42 |

| 2pq | 67 | 36 | |

| q2 | 44 | 59 | |

| A174D | p2 | 1 | 3 |

| 2pq | 22 | 18 | |

| q2 | 114 | 116 | |

| Δ4E4 | p2 | 0 | 1 |

| 2pq | 12 | 10 | |

| q2 | 125 | 126 | |

| N334K | p2 | 0 | 0 |

| 2pq | 5 | 7 | |

| q2 | 132 | 130 | |

| R59Op | p2 | 0 | 1 |

| 2pq | 10 | 8 | |

| q2 | 127 | 128 |

Genotypes calculated using the number of probands (n=137);

Calculation based on allele frequencies from Table 3, for example A149P, p=117/268=0.437, q=1−p=0.563. These frequencies are then multiplied by the number of independent genotypes (137).

In addition, this loss of heterozygosity in the A149P and A174D alleles can be demonstrated by calculating allele frequencies based on the number of homozygotes and determining a value for the heterozygotes (2pq), again using Hardy-Weinberg (Table 6). This calculation showed that the A149P and A174D heterozygotes were not as common as expected (p>0.05), thus confirming the observation shown in Table 5. However, analysis of heterozygotes with Δ4E4, R59Op, and A337V alleles based on allele frequencies (Table 6) predicted more heterozygotes than was observed. This could also be a result of positive assortive mating, but a lack of sufficient screening for HFI genotypes among some American ethnic groups would also explain this difference.

Table 6.

Expected versus observed number of heterozygote genotypes

| Allele | Frequency | p2 | p | q | 2pq | Calculateda | Observed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A149P | 42/137 | 0.3066 | 0.554 | 0.446 | 0.495 | 68±4 | 36 |

| A174D | 3/137 | 0.022 | 0.148 | 0.852 | 0.252 | 35±7 | 18 |

| R59Op/Δ4E4/A337V | 1/137 | 0.0073 | 0.0854 | 0.9146 | 0.156 | 21±8 | 12/10/1 |

Errors in calculated values determined by two standard deviations

Aldolase B is not critical for development

The identification of three unrelated patients harboring homozygous null alleles, Δ4E4 and R59Op, was unexpected (Fig. 1). The Δ4E4 mutation is caused by deletion of four base pairs in exon 4 that results in a frameshift and subsequent insertion of a premature stop codon. This produces a truncated form of aldolase B that is only 132 amino acid residues. The R59Op mutation inserts a premature stop codon in the open reading frame, resulting in a truncated protein of only 59 amino acid residues. Patients harboring two null alleles are essentially human “knock-outs.” The implication of the increased number of patients containing null alleles of ALDOB is twofold. Finding these alleles segregating independently across populations (see Table 4) suggests that these mutations arose from a single common ancestor and have spread throughout multiple populations. It does not appear that evolution has selected against these null mutations. The Δ4E4 allele was widely distributed around the world and has become the third most common HFI mutation in the American population. In addition to the homozygous null patients reported here, other cases of individuals with null genotypes have been reported (Table 7). This list shows homozygous genotypes are more common than compound heterozygous genotypes. Therefore, some selection cannot be ruled out.

Table 7.

Phenotypes of null genotypes

| Genotype | Phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| C239Op/C239Op | Vomiting, appetite loss, abdominal fullness, hepatic dysfunction, death at 4 months old | Kajihara et al. 1990 |

| IVS2-1Δ4/IVS2-1Δ4 | Death reported in proband’s family | Cross and Cox 1990 |

| M-1T/Y203Oc | Nausea and vomiting following fructose ingestion; fructose infusion following surgery caused coma, hepatic failure, and death | Ali et al. 1993 |

| R3Op/R3Op | Death reported in proband’s family | Ali et al. 1994b |

| Δ4E4/Δ4E4 | No phenotype reported | Santamaria et al. 1996 |

| Y203X/IVS3sas | No phenotype reported | Esposito et al. 2004 |

| Δ4E4/Δ4E4 | No phenotype reported | Santer et al. 2005 |

| IVS7+2/IVS7+2 | No phenotype reported | Santer et al. 2005 |

| E8Δ2/E8Δ2 | No phenotype reported | Santer et al. 2005 |

| L83ΔC/Y173X | No phenotype reported | Gruchota et al. 2006 |

| Δ4E4/Δ4E4 | Nausea, vomiting, gastrointestinal discomfort, and palpitation and cold sweat following fructose ingestion | Chi et al. 2007 |

| R59Op/R59Op | Nausea and diarrhea following fructose ingestion; aversion to sweets | This study |

| Δ4E4/Δ4E4 | Classic hereditary fructose intolerance symptoms | This study |

| R59Op/Δ4E4 | Deterioration following weaning, including lethargy and hepatomegaly | This study |

The first reports of patients harboring two null alleles suggested that these individuals exhibited more severe phenotypes, which may have resulted in a higher incidence of death because they retained no functional aldolase B activity (Cross and Cox 1990; Kajihara et al. 1990; Ali et al. 1993, 1994b). However, subsequent reports of such genotypes make no mention of any unusual phenotypes (Table 7). This has been confirmed in this study where a clear phenotype for three patients with homozygous null alleles indicated typical HFI symptoms. It seems that aldolase B null persons do not exhibit more severe phenotypes, and these earlier reports that included deaths are more likely due to untimely diagnosis of the disease.

The increased number of individuals unable to synthesize aldolase B calls into question its biochemical role outside of fructose metabolism. It is known that the major causes of HFI are due to missense mutations in ALDOB (Tolan 1995). Much work has been done to characterize the activity (or lack thereof) of the resulting proteins, in particular, A149P (Malay et al. 2002, 2005). Surprisingly, some recombinantly expressed HFI-mutant proteins have activities toward fructose-1-phosphate cleavage and are no more than twofold less than the wild-type aldolase B enzyme. L256P and A337V, in particular, have approximately half the activity of wild type toward fructose-1-phosphate cleavage (Rellos et al. 1999; Esposito et al. 2002). It is clear that some HFI mutant proteins containing amino acid substitutions maintain significant levels of residual activity. This could explain the wide range of symptoms reported by HFI patients harboring missense mutations (Davit-Spraul et al. 2008). Whereas A337V retains enzyme activity at 37°C, A149P is catalytically inactive (Malay et al. 2002). This highlights the range of effects that various amino acid substitutions have on enzyme activity. It is interesting that patients with null alleles, who are essentially knock-outs synthesizing no aldolase B, do not exhibit phenotypes any more severe than their counterparts with missense mutations. It seems clear from these HFI patients producing conceivably no aldolase B or severely truncated, nonfunctional forms of the enzyme, that this protein is not required for proper development or metabolic maintenance in the absence of fructose.

Conclusions

HFI is a rare but serious metabolic disease, with patients having an improved quality of life once an accurate diagnosis is made. Toward this end, this study identifies the frequencies of known HFI alleles in the American population. The five most common alleles are A149P, A174D, Δ4E4, R59Op, and N334K. Unique to this population is the high prevalence of two nonsense mutations (Δ4E4 and R59Op). In contrast to other populations worldwide, work remains for a complete description of HFI mutant alleles common to the American population. Furthermore, the frequency of null alleles, including homozygous individuals, confirms that aldolase B is not critically required for proper development. There remains a number of unidentified HFI-causing mutations in ALDOB, and work toward uncovering them is required to improve genetic-based diagnosis of this disease in the American population.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sarah Kampert, Miho Teruya, Christine Foster, Janet Lau, and Sheri Procious for their technical assistance in the genetic screening and Dr. John Celenza for many helpful discussions.

Abbreviations

- HFI

hereditary fructose intolerance

- ASO

allele-specific oligonucleotide

Contributor Information

Erin M. Coffee, Email: erin@bu.edu, Biology Department, Boston University, 5 Cummington Street, Boston, MA 02215, USA

Laura Yerkes, Email: laurayerkes@gmail.com, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Program, Boston University, Boston, MA 02215, USA.

Elizabeth P. Ewen, Email: ebrave@bu.edu, Biology Department, Boston University, 5 Cummington Street, Boston, MA 02215, USA

Tiffany Zee, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Program, Boston University, Boston, MA 02215, USA.

Dean R. Tolan, Email: tolan@bu.edu, Biology Department, Boston University, 5 Cummington Street, Boston, MA 02215, USA, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Program, Boston University, Boston, MA 02215, USA

References

- Ali M, Cox TM. Diverse mutations in the aldolase B gene that underlie the prevalence of hereditary fructose intolerance [letter] Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56:1002–1005. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M, Rosien U, Cox TM. DNA diagnosis of fatal fructose intolerance from archival tissue. Quart J Med. 1993;86:25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M, Sebastio G, Cox TM. Identification of a novel mutation (Leu 256 -> Pro) in the human aldolase B gene associated with hereditary fructose intolerance. Hum Mol Genet. 1994a;3:203–204. 684. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.1.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M, Tunçman G, Cross N, et al. Null alleles of the aldolase B gene in patients with hereditary fructose intolerance. J Med Genet. 1994b;31:499–503. doi: 10.1136/jmg.31.6.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M, James CL, Cox TM. A newly identified aldolase B splicing mutation (G–>C, 5′ intron 5) in hereditary fructose intolerance from New Zealand. Hum Mutat. 1996;7:155–157. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1996)7:2<155::AID-HUMU11>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M, Rellos P, Cox TM. Hereditary fructose intolerance. J Med Genet. 1998;35:353–365. doi: 10.1136/jmg.35.5.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Community Survey. Demographic and Housing Estimates: (2006–2008) United States Census Bureau. Retrieved from http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/SAFFFacts on 12-15-09.

- Baerlocher K, Gitzelmann R, Steinmann B, Gitzelmann-Cumarumsay N. Hereditary fructose intolerance in early childhood: a major diagnostic challenge. Helv Paediat Acta. 1978;33:465–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer PL, Caviar EM, McCallum RW. Fructose intake at current levels in the United States may cause gastrointestinal distress in normal adults. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:1559–1566. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks CC, Tolan DR. A partially active mutant aldolase B from a patient with hereditary fructose intolerance. FASEB J. 1994;8:107–113. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.1.8299883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caciotti A, Donati MA, Adami A, Guerrini R, Zammarchi E, Morrone A. Different genotypes in a large Italian family with recurrent hereditary fructose intolerance. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:118–121. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f172e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi ZN, Hong J, Yang J, et al. Clinical and genetic analysis for a Chinese family with hereditary fructose intolerance. Endocrine. 2007;32:122–126. doi: 10.1007/s12020-007-9013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YK, Johlin FC, Jr, Summers RW, Jackson M, Rao SS. Fructose intolerance: an under-recognized problem. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1348–1353. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa C, Costa JM, Deleuze JF, Legrand A, Hadchouel M, Baussan C. Simple, rapid nonradioactive method to detect the three most prevalent hereditary fructose intolerance mutations. Clin Chem. 1998;44:1041–1043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox TM. Hereditary fructose intolerance. Quart J Med. 1988;68:585–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox TM. Fructose intolerance: heredity and the environment. In: Randle PJ, Bell JI, Scott J, editors. Genetics and human nutrition. John Libbey; London: 1990a. pp. 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Cox TM. Hereditary fructose intolerance. Baillier Clin Gastroenterol. 1990b;4:61–78. doi: 10.1016/0950-3528(90)90039-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox TM. Iatrogenic deaths in hereditary fructose intolerance. Arch Dis Childhood. 1993;69:423–415. doi: 10.1136/adc.69.4.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox TM. Aldolase B and fructose intolerance. FASEB J. 1994;8:62–71. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.1.8299892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox TM. The genetic consequences of our sweet tooth. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:481–487. doi: 10.1038/nrg815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross NC, Cox TM. Partial aldolase B gene deletions in hereditary fructose intolerance. Am J Hum Genet. 1990;47:101–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross NCP, Tolan DR, Cox TM. Catalytic deficiency of human aldolase B in hereditary fructose intolerance caused by a common missense mutation. Cell. 1988;53:881–885. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)90349-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross NC, de Franchis R, Sebastio G, et al. Molecular analysis of aldolase B genes in hereditary fructose intolerance. Lancet. 1990a;335:306–309. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90603-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross NCP, Stojanov LM, Cox TM. A new aldolase B variant, N334K, is a common cause of hereditary fructose intolerance in Yugoslavia. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990b;18:1925. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.7.1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davit-Spraul A, Costa C, Zater M, et al. Hereditary fructose intolerance: frequency and spectrum mutations of the aldolase B gene in a large patients cohort from France–identification of eight new mutations. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;94:443–447. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dazzo C, Tolan DR. Molecular evidence for compound heterozygosity in hereditary fructose intolerance. Am J Hum Genet. 1990;46:1194–1199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza M, Lindeman R, Volpato F, Trent RJ, Kamath R. Mutation of aldolase B genes in hereditary fructose intolerance. Lancet. 1990;335:856. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90969-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dursun A, Kalkanoglu HS, Coskun T, et al. Mutation analysis in Turkish patients with hereditary fructose intolerance. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2001;24:523–526. doi: 10.1023/a:1012423624993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito G, Vitagliano L, Santamaria R, Viola A, Zagari A, Salvatore F. Structural and functional analysis of aldolase B mutants related to hereditary fructose intolerance. FEBS Lett. 2002;531:152–156. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03451-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito G, Santamaria R, Vitagliano L, et al. Six novel alleles identified in Italian hereditary fructose intolerance patients enlarge the mutation spectrum of the aldolase B gene. Hum Mutat. 2004;24:534. doi: 10.1002/humu.9290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitzelmann R, Baerlocher K. Vorteile und Nachteile der Frucosein der Nahrung. Padiat Fortbildk Prxis. 1973;37:40–55. [Google Scholar]

- Gomara RE, Halata MS, Newman LJ, et al. Fructose intolerance in children presenting with abdominal pain. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47:303–308. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318166cbe4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruchota J, Pronicka E, Korniszewski L, et al. Aldolase B mutations and prevalence of hereditary fructose intolerance in a Polish population. Mol Genet Metab. 2006;87:376–378. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackl JM, Balogh D, Kunz F, et al. Postoperative Fruktoseintoleranz. Weiner Klin Wschrift. 1978;90:237–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine W, Schill H, Tessman D, Kupatz H. Letale Leberdystrophie bei drei Geschwistern mit hereditärer Fruktoseintoleranz nach Dauertropfinfusionen mit sorbitolhaltigen Infusionslösungen. Dtsch Gesundheitsw. 1969;24:2325–2329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hers H-G, Joassin G. Anomalie de l’aldolase hepatique dans l’intolerance au fructose. Enzymol Biol Clin. 1961;1:4–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillebrand G, Schneppenheim R, Oldigs HD, Santer R. Hereditary fructose intolerance and alpha(1) antitrypsin deficiency. Arch Dis Childhood. 2000;83:72–73. doi: 10.1136/adc.83.1.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James CL, Rellos P, Ali M, Heeley AF, Cox TM. Neonatal screening for hereditary fructose intolerance: frequency of the most common mutant aldolase B allele (A149P) in the British population. J Med Genet. 1996;33:837–841. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.10.837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser UB, Hegele RA. Case report: Heterogeneity of aldolase B in hereditary fructose intolerance. Am J Med Sci. 1991;302:364–368. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199112000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajihara S, Mukai T, Arai Y, Owada M, Kitagawa T, Hori K. Hereditary fructose intolerance caused by a nonsense mutation of the aldolase B gene. Am J Hum Genet. 1990;47:562–567. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karabulut HG, Halsall D, Sayin BD, Tonyukuk V, Cox TM, Bokesoy I. Aldolase B mutations in Turkish families from central Anatolia. Genet Couns. 2006;17:457–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayano T, Burant CF, Fukumoto H, et al. Human facilitative glucose transporters. Isolation, functional characterization, and gene localization of cDNAs encoding an isoform (GLUT5) expressed in small intestine, kidney, muscle, and adipose tissue and an unusual glucose transporter pseudogene-like sequence (GLUT6) J Biol Chem. 1990;265:13276–13282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegshauser G, Halsall D, Rauscher B, Oberkanins C. Semiautomated, reverse-hybridization detection of multiple mutations causing hereditary fructose intolerance. Molec Cell Probes. 2007;21:226–228. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullberg-Lindh C, Hannoun C, Lindh M. Simple method for detection of mutations causing hereditary fructose intolerance. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2002;25:571–575. doi: 10.1023/a:1022043307569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laméire N, Mussche M, Baele G, Kint J, Ringoir S. Hereditary fructose intolerance: A difficult diagnosis in the adult. Am J Med. 1978;65:416–423. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(78)90767-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen K, Adnanes O, Aarskog NK, Runde I, Ogreid D. Congenital fructose intolerance. New molecular aspects. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 1994;114:3312–3314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes AI, Alameida AG, Costa AE, Costa A, Leite M. Intolerância hereditária á fructose. Acta Méd Port. 1997;11:1121–1125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malay AD, Procious SL, Tolan DR. The temperature dependence of activity and structure for the most prevalent mutant aldolase B associated with hereditary fructose intolerance. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;408:295–304. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00546-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malay AD, Allen KN, Tolan DR. Structure of the thermolabile mutant aldolase B, A149P: molecular basis of hereditary fructose intolerance. J Mol Biol. 2005;347:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RCJ. An experimental renal acidification defect in patients with hereditary fructose intolerance. II. Its distinction from classic renal tubular acidosis: its resemblance to the renal acidification defect associated with the Fanconi syndrome of children with cystinosis. J Clin Invest. 1968;47:1648–1663. doi: 10.1172/JCI105856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller P, Meier C, Bohme HJ, Richter T. Fructose breath hydrogen test–is it really a harmless diagnostic procedure? Dig Dis. 2003;21:276–278. doi: 10.1159/000073348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odiévre M, Gentil C, Gautier M, Alagille D. Hereditary fructose intolerance in childhood: diagnosis, management and course in 55 patients. Am J Dis Child. 1978;132:605–608. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1978.02120310069014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orkin SH, Alter BP, Altay C, et al. Application of endonuclease mapping to the analysis and prenatal diagnosis of thalassemias caused by globin-gene deletion. New Engl J Med. 1978;299:166–172. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197807272990403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rellos P, Ali M, Vidailhet M, Sygusch J, Cox TM. Alteration of substrate specificity by a naturally-occurring aldolase B mutation (Ala337–>Val) in fructose intolerance. Biochem J. 1999;340:321–327. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saiki RK, Scharf S, Faloona F, et al. Enzymatic amplification of b-globin genomic sequences and restriction analysis for diagnosis of sickle cell anemia. Science. 1985;230:1350–1354. doi: 10.1126/science.2999980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; New York: 1989. Pages. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Gutierrez JC, Benlloch T, Leal MA, Samper B, Garcia-Ripoll I, Feliu JE. Molecular analysis of the aldolase B gene in patients with hereditary fructose intolerance from Spain. J Med Genet. 2002;39:e56. doi: 10.1136/jmg.39.9.e56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santamaria R, Scarano MI, Esposito G, Chiandetti L, Izzo P, Salvatore F. The molecular basis of hereditary fructose intolerance in Italian children. Eur J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1993;31:675–678. doi: 10.1515/cclm.1993.31.10.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santamaria R, Tamasi S, Del Piano G, et al. Molecular basis of hereditary fructose intolerance in Italy: identification of two novel mutations in the aldolase B gene. J Med Genet. 1996;33:786–788. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.9.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santamaria R, Vitagliano L, Tamasi S, et al. Novel six-nucleotide deletion in the hepatic fructose-1, 6-bisphosphate aldolase gene in a patient with hereditary fructose intolerance and enzyme structure-function implications. Eur J Hum Genet. 1999;7:409–414. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santer R, Rischewski J, von Weihe M, et al. The spectrum of aldolase B (ALDOB) mutations and the prevalence of hereditary fructose intolerance in Central Europe. Hum Mutat. 2005;25:594. doi: 10.1002/humu.9343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte MJ, Lenz W. Fatal sorbitol infusion in patient with fructose-sorbitol intolerance. Lancet. 1977;2:188. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)90197-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastio G, de Franchis R, Strisciuglio P, et al. Aldolase B mutations in Italian families affected by hereditary fructose intolerance. J Med Genet. 1991;28:241–243. doi: 10.1136/jmg.28.4.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann B, Gitzelmann R. The diagnosis of hereditary fructose intolerance. Helv Paediat Acta. 1981;36:297–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann B, Gitzelmann R, Van den Berghe G. Disorders of fructose metabolism. In: Scriver C, Beaudet A, Sly W, Valle D, editors. The metabolic and molecular basis of inherited disease. McGraw-Hill, Inc; New York: 2001. pp. 1489–1520. [Google Scholar]

- Stormon MO, Cutz E, Furuya K, et al. A six month old infant with steatohepatitis. J Ped. 2003;144:258–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan DR. Molecular basis of hereditary fructose intolerance: mutations and polymorphisms in the human aldolase B gene. Hum Mutat. 1995;6:210–218. doi: 10.1002/humu.1380060303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan DR, Brooks CC. Molecular analysis of common aldolase B alleles for hereditary fructose intolerance in North Americans. Biochem Molec Med. 1992;48:19–25. doi: 10.1016/0885-4505(92)90043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman D, Hoekstra JH, Tolia V, et al. Molecular analysis of the fructose transporter gene (GLUT5) in isolated fructose malabsorption. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2398–2402. doi: 10.1172/JCI119053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JD, Robertson T, Whiley M. Hereditary fructose intolerance in an adult. Austral N Zeal J Med. 1995;25:259–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1995.tb01541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]