Abstract

Study Objectives:

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of doxepin 1 mg and 3 mg in elderly subjects with chronic primary insomnia.

Design and Methods:

The study was a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial. Subjects meeting DSM-IV-TR criteria for primary insomnia were randomized to 12 weeks of nightly treatment with doxepin (DXP) 1 mg (n = 77) or 3 mg (n = 82), or placebo (PBO; n = 81). Efficacy was assessed using polysomnography (PSG), patient reports, and clinician ratings. Objective efficacy data are reported for Nights (N) 1, 29, and 85; subjective efficacy data during Weeks 1, 4, and 12; and Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale and Patient Global Impression (PGI) scale data after Weeks 2, 4, and 12 of treatment. Safety assessments were conducted throughout the study.

Results:

DXP 3 mg led to significant improvement versus PBO on N1 in wake time after sleep onset (WASO; P < 0.0001; primary endpoint), total sleep time (TST; P < 0.0001), overall sleep efficiency (SE; P < 0.0001), SE in the last quarter of the night (P < 0.0001), and SE in Hour 8 (P < 0.0001). These improvements were sustained at N85 for all variables, with significance maintained for WASO, TST, overall SE, and SE in the last quarter of the night. DXP 3 mg significantly improved patient-reported latency to sleep onset (Weeks 1, 4, and 12), subjective TST (Weeks 1, 4, and 12), and sleep quality (Weeks 1, 4, and 12). Several global outcome-related variables were significantly improved, including the severity and improvement items of the CGI (Weeks 2, 4, and 12), and all 5 items of the PGI (Week 12; 4 items after Weeks 2 and 4). Significant improvements were observed for DXP 1 mg for several measures including WASO, TST, overall SE, and SE in the last quarter of the night at several time points. Rates of discontinuation were low, and the safety profiles were comparable across the 3 treatment groups. There were no significant next-day residual effects; additionally, there were no reports of memory impairment, complex sleep behaviors, anticholinergic effects, weight gain, or increased appetite.

Conclusions:

DXP 1 mg and 3 mg administered nightly to elderly chronic insomnia patients for 12 weeks resulted in significant and sustained improvements in most endpoints. These improvements were not accompanied by evidence of next-day residual sedation or other significant adverse effects. DXP also demonstrated improvements in both patient- and physician-based ratings of global insomnia outcome. The efficacy of DXP at the doses used in this study is noteworthy with respect to sleep maintenance and early morning awakenings given that these are the primary sleep complaints of the elderly. This study, the longest placebo-controlled, double-blind, polysomnographic trial of nightly pharmacotherapy for insomnia in the elderly, provides the best evidence to date of the sustained efficacy and safety of an insomnia medication in older adults.

Citation:

Krystal AD; Durrence HH; Scharf M; Jochelson P; Rogowski R; Ludington E; Roth T. Efficacy and safety of doxepin 1 mg and 3 mg in a 12-week sleep laboratory and outpatient trial of elderly subjects with chronic primary insomnia. SLEEP 2010;33(11):1553-1561.

Keywords: Chronic insomnia, elderly adults, sleep maintenance insomnia, early morning awakenings, wake time after sleep onset

INSOMNIA IS DEFINED AS DIFFICULTY INITIATING SLEEP, MAINTAINING SLEEP, AND/OR NONRESTORATIVE SLEEP ACCOMPANIED BY DAYTIME impairments.1 Although, not found in all studies, many investigations have found that the risk of insomnia increases with age.2–6 Insomnia has also been reported to be more severe in the elderly.2 Older adults with insomnia awaken more frequently and spend a greater percentage of their nights awake than do non-elderly adults with insomnia.2 While insomnia is associated with decreased quality of life and impairment in function in general, there are some concerning consequences that are specific to the elderly, including increased risk of falls and nursing home placement.7–9

The greater severity and consequences of insomnia in older adults speak to the need for developing effective insomnia treatments for this population. Unfortunately, fewer studies of pharmacologic insomnia therapy have been conducted in this population relative to younger adults.10 In this regard, data are notably lacking on the benefit of insomnia treatment in the elderly.

Evidence to support extended treatment is especially important for older adults as they appear to be more susceptible to developing chronic insomnia.6,11,12 In a study of elderly general practice patients, 57% met diagnostic criteria for insomnia, with 80% of these patients reporting insomnia duration of greater than 1 year.13 However, there is a corresponding increase in the duration of pharmacotherapy for insomnia with age,14–16 and there are no studies which provide an indication of the safety or efficacy of this practice for any agents.10 Indeed, there have been only 3 large, double-blind, placebo-controlled published trials evaluating the efficacy of any insomnia agent for more than 5 weeks, and none of these trials were conducted in the elderly.17–19 Although the present study does not fully address this deficiency, it is of importance as it is the longest PSG trial of the efficacy and safety of insomnia pharmacotherapy in the elderly. The inclusion of PSG outcome assessment addresses concerns related to the adequacy of blinding and the effects of differential dropout that have been raised because of the lack of objective outcome measures in prior pharmacotherapy trials purporting to establish the sustained efficacy of insomnia medications.20

This study was carried out using doxepin, which has particular promise as a treatment for elderly insomnia patients. This agent appears to be a selective histamine antagonist (primarily at the H1 receptor) at low doses and has been found to have significant efficacy for improving sleep in doses as low as 1 mg, 3 mg, and 6 mg, with minimal adverse effects in 2 previous clinical trials of patients with primary insomnia.21,22 Data from these trials represent the only evidence of an insomnia therapy having a therapeutic effect on sleep maintenance in the last third of the night, while manifesting no evidence of morning impairment in careful assessments of next-day effects.21,22 It is important to note that sleep maintenance problems and sleep difficulties in the latter part of the night are especially common in the elderly. Difficulty maintaining sleep is reported by one-third of older adults and is the most frequent sleep complaint in the elderly.2,6 At the same time, one-fourth of elderly insomnia patients report waking too early with difficulty returning to sleep (early morning awakenings).6 The current study assesses the efficacy and safety of doxepin at doses of 1 mg and 3 mg in a 12-week trial of elderly subjects with chronic insomnia.

METHODS

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study was conducted in 31 sleep centers in the United States. An institutional review board approved the protocol for each study site and the study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonisation of Good Clinical Practices. All subjects signed an informed consent form prior to screening procedures.

Participants and Screening Procedures

Men and women 65 years of age and older with a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of primary insomnia who reported difficulty sleeping were eligible for inclusion in the study. Patient screening for general eligibility and sleep history was conducted during an initial clinic visit and involved a medical history, physical examination, vital sign measurements, clinical laboratory tests, and an electrocardiogram. Subjects meeting initial screening criteria were asked to record their sleep patterns onto a daily sleep diary prior to PSG screening (minimum of 7 days of assessment). The initial screening results and sleep diary data were used to verify a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of primary insomnia for ≥ 3 months.

Primary reasons for patient exclusion from the study were as follows: (1) excessive use of alcohol, nicotine, or caffeinated beverages; (2) intentional napping > twice per week; (3) having a variation in bedtime > 2 h for 5 of 7 nights; or (4) use of a hypnotic or any other medication known to affect sleep. A number of these criteria were employed to prevent including subjects in the study whose sleep problems might have been likely to improve as a result of making sleep/wake related scheduling changes through participating in the study protocol and who would have been expected to improve in response to behavioral insomnia interventions.

Subjects meeting eligibility criteria began one week of single-blind placebo dosing. Subjects spent the first 2 nights in a sleep laboratory to determine whether they met PSG screening criteria. Subjects were required to have a latency to persistent sleep (LPS) > 10 minutes, a wake time during sleep (WTDS) ≥ 60 minutes, and a TST > 240 and ≤ 390 minutes to be eligible for randomization. WTDS was used for screening in the present trial to ensure that middle-of-the-night sleep problems were the predominant symptom in this sample. Subjects were excluded from the study if they had ≥ 15 apnea/hypopnea events per hour. Subjects who remained eligible continued to take single-blind placebo for 5 consecutive nights at home.

Procedures

Eligible subjects were randomly assigned to one of 3 treatment groups (doxepin 1 mg, 3 mg, or placebo) in a 1:1:1 ratio. Subsequently, subjects began the 12-week double-blind treatment period, which included supervised administration of study drug in a sleep laboratory on N1, N15, N29, N57, and N85 and nightly self-administration of study drug at home between visits. While in the sleep laboratory, subjects took a single dose of study drug with 100 mL of water in the presence of study center personnel 30 min before bedtime on each PSG recording night. Subjects were instructed to self-administer study drug 30 min prior to bedtime when dosing at home. Starting on the day prior to double-blind treatment and every 7 days thereafter, subjects were instructed to phone in to the Interactive Voice Response System (IVRS) from home to provide subjective efficacy assessments.

Subjects were instructed to arrive at the study center on sleep laboratory nights for 8 h of continuous PSG recording. The following morning, approximately 1 h after completion of PSG recording, subjects filled out a questionnaire assessing subjective sleep characteristics and completed a battery of tests evaluating next-day residual effects. Safety assessments were performed pre- and post-dose.

Study Assessments

The PSG recordings were conducted in accordance with Rechtschaffen and Kales criteria,23 and were scored by a PSG technologist at a central PSG facility in a blinded fashion. The prospectively defined primary efficacy endpoint was WASO on N1. Other prospectively defined PSG efficacy variables included WASO at other time points, LPS (defined as min from lights out to the first 10 min of consecutive sleep), number of awakenings after sleep onset (NAW), TST, SE, and wake time after sleep (WTAS). SE was further analyzed prospectively by quarter of the night and by hour of the night. Patient-reported IVRS measures included latency to sleep onset (LSO), sTST, and sleep quality.

Several global insomnia measures were used to assess overall treatment outcome and aspects of daytime function by evaluating both the subject's and clinician's perception of symptom improvement and severity. The measures were the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale,24 the Patient Global Impression (PGI) scale, and the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI).25 The CGI scale, completed by the patient's clinician, assessed the severity of insomnia (CGI-Severity) and the therapeutic effect (CGI-Improvement) of the study drug. The patient-rated PGI scale included 5 questions pertaining to the therapeutic effect of the study drug. The ISI consisted of 7 questions related to subject's self-assessment of the severity of their insomnia. Additionally there were two 6-point Likert scales administered the evening prior to PSG assessing daytime function (1 = extremely poor to 6 = excellent) and drowsiness (1 = extremely drowsy to 6 = extremely alert) during the preceding day.

All efficacy measures were assessed for up to 12 weeks. Results are provided for objective efficacy assessments on N1, N29, and N85, and for subjective efficacy assessments on Weeks 1, 4, and 12. CGI, PGI, and ISI results are provided after Weeks 2, 4, and 12 of treatment.

Next-day hangover/residual effects were assessed objectively with the Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST)26 and Symbol Copying Test (SCT),26 and subjectively with a 100 mm visual analog scale (VAS) for sleepiness. Safety was assessed by monitoring adverse events (AEs) and by examining the changes from baseline in laboratory test values (hematology, serum chemistry, and urinalysis), vital signs, 12-lead electrocardiograms, and physical examinations.

Statistical Analysis

Efficacy analyses were conducted using the intent-to-treat analysis set. This dataset included all randomized subjects who received at least one dose of double-blind study drug. Patient-reported IVRS data were available for a subset of subjects (62 placebo; 63 doxepin 1 mg; 66 doxepin 3 mg). For IVRS data, missing values at baseline were imputed using the overall mean value at baseline. For the remainder of the variables, the observed data were used with no imputations conducted. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) methods were used to compare WASO values from N1 between placebo and each doxepin group (1 mg and 3 mg), using a model that included main effects for treatment and study center with baseline WASO as a covariate. Each pairwise comparison of doxepin to placebo was performed using a linear contrast. The same methods were used to analyze all other continuous efficacy variables. In order to determine if treatment was maintained across time, a one-sample (paired) t-test was used to assess whether the change from Night 1 to Night 85 was significantly different from zero for WASO and LSO for each treatment group. For LPS, latency to REM sleep, latency to stage 2 sleep, and LSO, data were analyzed using log-transformed values (natural log). Scores obtained from the CGI-Improvement and PGI scales were assessed categorically. Comparison of each doxepin group to placebo was conducted using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel χ2 (row mean score) test stratified by center.

Funding for this study was provided by Somaxon Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Data and statistical analyses for this study were fully available to all authors. The randomization sequence and statistical analyses were performed with the sponsor's approval by a representative. All authors were involved with the preparation of the manuscript and vouch for the completeness and accuracy of the data and analyses presented.

RESULTS

Study Population

A total of 923 subjects were screened for participation. Of these subjects, 240 met all entry criteria and were randomized to doxepin 1 mg (n = 77), doxepin 3 mg (n = 82), or placebo (n = 81), with 214 (89%) completing the study. Early discontinuation rates and baseline characteristics were comparable across treatment groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study disposition and demographics

| Parameter | Placebo (n = 81) | Doxepin 1 mg (n = 77) | Doxepin 3 mg (n = 82) | Total (n = 240) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completed study | 86% | 91% | 90% | 89% |

| Discontinued from study | 14% | 9% | 10% | 11% |

| Adverse Event | 4% | 1% | 4% | 3% |

| Consent Withdrawn | 7% | 0% | 2% | 3% |

| Protocol Violation | 2% | 3% | 1% | 2% |

| Noncompliance | 0% | 4% | 0% | 1% |

| Other | 0% | 1% | 2% | 1% |

| Age (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 71.5 (5.5) | 71.3 (5.2) | 71.4 (4.9) | 71.4 (5.2) |

| Range | 65-93 | 64-85 | 65-88 | 64-93 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 59% | 65% | 70% | 65% |

| Male | 41% | 35% | 30% | 35% |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 83% | 82% | 77% | 80% |

| African American | 7% | 6% | 12% | 9% |

| Hispanic | 5% | 10% | 11% | 9% |

| Other | 5% | 1% | 0% | 2% |

Sleep Efficacy

Sleep maintenance and duration

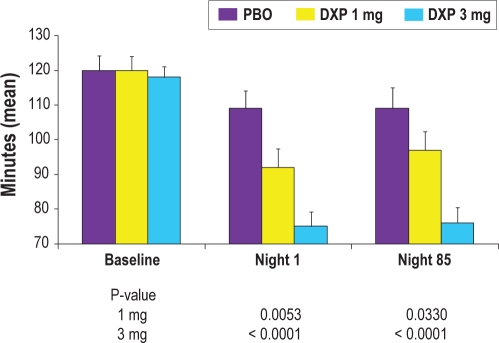

All of the following comparisons were versus placebo unless otherwise noted. WASO was significantly improved on N1 (primary efficacy endpoint) for doxepin 3 mg (P < 0.0001; Figure 1) and 1 mg (P = 0.0053). WASO was also significantly improved on N29 (P = 0.0005) and N85 (P < 0.0001) for doxepin 3 mg, and on N85 (P = 0.0330) for doxepin 1 mg. The t-test test to examine WASO efficacy across time determined that N1 data were not significantly different from N85 data for all 3 groups. Mean change from N1 to N85 (P-values in parentheses) were: PBO = 0.4 (0.96); DXP 1 mg = 3.0 (0.57); DXP 3 mg = 0.9 (0.62). TST and overall SE were significantly improved on N1 (P < 0.0001), N29 (P = 0.0161), and N85 (P = 0.0007) for doxepin 3 mg, and on N1 (P = 0.0119) and N85 (P = 0.0257) for doxepin 1 mg. PSG results for WASO and other sleep maintenance and duration parameters are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Effects of doxepin 1 mg and 3 mg versus placebo on 8-h wake after sleep onset (WASO) at Baseline, Night 1, and Night 85; data are in minutes (mean), with standard error bars included.

Table 2.

Effect of doxepin and placebo on PSG sleep onset, sleep maintenance, and early morning awakening parameters

| Measure | Baseline |

Night 1 |

Night 29 |

Night 85 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | |

| WASO (min) | ||||||||

| Placebo | 119.5 | (37.7) | 108.9 | (46.0) | 104.6 | (53.5) | 109.2 | (50.8) |

| DXP 1 mg | 120.1 | (35.0) | 91.8** | (47.1) | 96.4 | (45.3) | 97.0* | (44.2) |

| DXP 3 mg | 117.9 | (28.2) | 74.5*** | (37.9) | 84.3*** | (40.9) | 75.7*** | (37.6) |

| TST (min) | ||||||||

| Placebo | 320.6 | (40.3) | 339.7 | (54.4) | 345.0 | (59.1) | 343.7 | (57.7) |

| DXP 1 mg | 322.4 | (39.9) | 359.1* | (53.1) | 344.4 | (55.1) | 360.5* | (47.2) |

| DXP 3 mg | 326.9 | (33.2) | 382.9*** | (44.2) | 363.9* | (54.0) | 373.7*** | (42.2) |

| SE %, Last Quarter | ||||||||

| Placebo | 64.7 | (17.0) | 62.1 | (24.3) | 64.7 | (24.9) | 65.0 | (25.7) |

| DXP 1 mg | 64.4 | (18.6) | 72.5** | (19.4) | 68.2 | (22.5) | 69.4 | (23.3) |

| DXP 3 mg | 65.0 | (15.3) | 76.6*** | (16.7) | 75.7*** | (18.6) | 76.1** | (17.8) |

| NAW | ||||||||

| Placebo | 13.6 | (4.8) | 13.2 | (5.5) | 12.6 | (5.0) | 11.9 | (5.3) |

| DXP 1 mg | 14.4 | (4.6) | 14.3 | (6.4) | 14.9* | (5.9) | 14.9** | (6.6) |

| DXP 3 mg | 13.3 | (4.3) | 14.0 | (6.2) | 13.3 | (5.2) | 12.9 | (5.6) |

| LPS (min) | ||||||||

| Placebo | 49.0 | (27.3) | 39.6 | (29.3) | 39.1 | (42.4) | 34.9 | (33.0) |

| DXP 1 mg | 45.4 | (25.3) | 38.8 | (29.6) | 49.2 | (51.2) | 29.0 | (26.5) |

| DXP 3 mg | 41.9 | (22.7) | 28.6 | (20.5) | 39.6 | (40.0) | 37.5 | (32.7) |

SD, standard deviation; DXP, doxepin; WASO, wake after sleep onset; TST, total sleep time; SE, sleep efficiency; WTAS, wake time after sleep; NAW, number of awakenings after sleep onset; LPS, latency to persistent sleep;

P < 0.05 vs placebo;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001

Patient-reported weekly IVRS data were consistent with PSG data, with significant improvement in sTST at Weeks 1 (P = 0.0043), 4 (P = 0.0035), and 12 (P = 0.0001) for doxepin 3 mg, and at Weeks 4 (P = 0.0343) and 12 (P = 0.0027) for doxepin 1 mg (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of doxepin and placebo on subjective sleep and global outcomes parameters

| Measure | Baseline |

Week 1 |

Week 4 |

Week 12 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | |

| LSO (min)1 | ||||||||

| Placebo | 56.3 | (32.4) | 59.7 | (47.2) | 56.5 | (36.8) | 55.5 | (39.5) |

| DXP 1 mg | 60.8 | (51.2) | 54.2 | (34.6) | 45.2* | (30.0) | 37.5** | (22.8) |

| DXP 3 mg | 48.0 | (25.7) | 40.0** | (28.2) | 48.6* | (48.7) | 39.9* | (30.3) |

| sTST (min)1 | ||||||||

| Placebo | 280.2 | (87.9) | 316.2 | (68.3) | 317.5 | (83.2) | 326.0 | (77.9) |

| DXP 1 mg | 297.6 | (73.3) | 319.7 | (84.6) | 348.8* | (60.3) | 371.5** | (59.8) |

| DXP 3 mg | 308.7 | (80.9) | 356.8** | (61.1) | 362.5** | (65.4) | 389.4*** | (65.9) |

| Sleep Quality1 | ||||||||

| Placebo | −0.1 | (1.0) | 0.0 | (1.2) | 0.1 | (1.2) | 0.2 | (1.0) |

| DXP 1 mg | 0.0 | (0.8) | 0.2 | (1.1) | 0.5* | (1.0) | 0.8* | (0.9) |

| DXP 3 mg | 0.1 | (0.8) | 0.6** | (0.9) | 0.7** | (0.9) | 0.9** | (0.9) |

| CGI-Improvement2 | ||||||||

| Placebo | 3.6 | (0.8) | 3.2 | (1.0) | 3.2 | (1.1) | 3.1 | (1.1) |

| DXP 1 mg | 3.7 | (0.7) | 3.2 | (0.9) | 3.0 | (1.0) | 2.6** | (1.2) |

| DXP 3 mg | 3.7 | (0.9) | 2.7** | (1.1) | 2.8* | (1.2) | 2.4*** | (1.1) |

| Insomnia Severity Index2 | ||||||||

| Placebo | 15.4 | (3.8) | 14.0 | (4.2) | 13.5 | (4.0) | 13.0 | (4.9) |

| DXP 1 mg | 14.3 | (4.4) | 12.9 | (4.4) | 12.0 | (4.3) | 10.9 | (4.9) |

| DXP 3 mg | 15.1 | (3.8) | 12.5* | (4.6) | 11.6** | (4.9) | 10.6** | (4.7) |

SD, standard deviation; DXP, doxepin; LSO, latency to sleep onset; sTST, subjective total sleep time; sleep quality scale from −3 to 3; −3 = extremely poor to 3 = excellent;

these data were obtained from the IVRS analysis set;

assessments occurred after Weeks 2, 4, and 12;

P < 0.05 vs placebo;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001

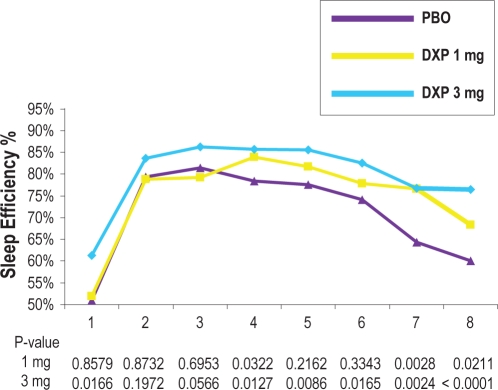

Early morning awakenings

SE in the last quarter of the night was significantly increased on N1 (P < 0.0001), N29 (P = 0.0004), and N85 (P = 0.0014) for doxepin 3 mg (Table 2). For doxepin 1 mg, SE in the last quarter of the night was significantly increased on N1 (P = 0.0011). SE in Hour 8 was significantly increased on N1 (P < 0.0001; Figure 2) and N29 (P = 0.0029) for doxepin 3 mg. For doxepin 1 mg, SE in Hour 8 was significantly increased on N1 (P = 0.0211). WTAS was significantly decreased on N85 (P = 0.0284) for doxepin 3 mg.

Figure 2.

Effects of doxepin 1 mg and 3 mg versus placebo across the 8-hour night: sleep efficiency % by Hour on Night 1.

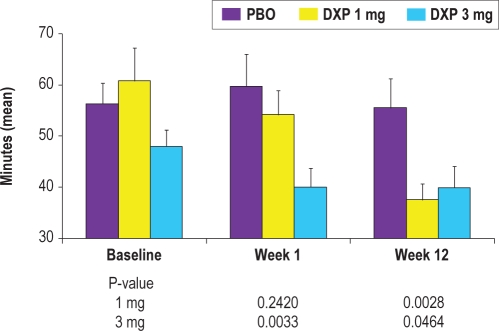

Sleep onset

LPS was not significantly reduced at any time point when compared to placebo (Table 2). Patient-reported IVRS data, however, revealed sleep onset improvements. LSO was significantly decreased at Weeks 1 (P = 0.0033; Figure 3), 4 (P = 0.0397), and 12 (P = 0.0464) for doxepin 3 mg, and at Weeks 4 (P = 0.0116) and 12 (P = 0.0028) for doxepin 1 mg. The t-test test to examine LSO efficacy across time determined that Week 1 data were not significantly different from Week 12 data for PBO and DXP 3 mg; LSO for DXP 1 mg was significantly better at Week 12 compared to Week 1. Mean change from Week 1 to Week 12 (P-values in parentheses) are: PBO = −4.1 (0.56); DXP 1 mg = −15.2 (0.0029; DXP 3 mg = 0.7 (0.83).

Figure 3.

Effects of doxepin 1 mg and 3 mg versus placebo on subjective latency to sleep onset (LSO) at Baseline, Week 1, and Week 12; data were obtained from the IVRS analysis set and are in minutes (mean), with standard error bars included.

Sleep quality

Sleep quality was significantly increased at Weeks 1 (P = 0.0039), 4 (P = 0.0049), and 12 (P = 0.0100) for doxepin 3 mg, and at Weeks 4 (P = 0.0464) and 12 (P = 0.0107) for doxepin 1 mg.

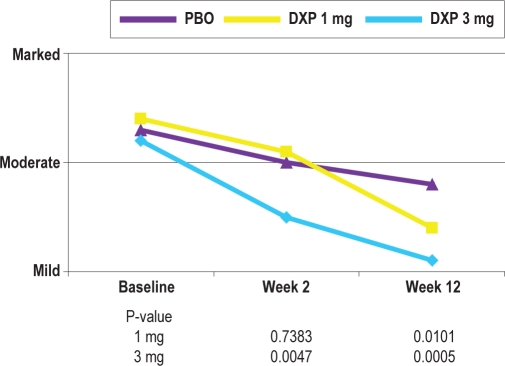

Global Insomnia Outcomes and Daytime Function

There was significant improvement after 2 weeks (P = 0.0047), after 4 weeks (P = 0.0356), and after 12 weeks (P = 0.0005) on the CGI-Severity scale score for doxepin 3 mg, and after 12 weeks (P = 0.0101) for doxepin 1 mg. There was significant improvement after 2 weeks (P = 0.0060), after 4 weeks (P = 0.0334), and after 12 weeks (P = 0.0008) on the CGI-Improvement scale score for doxepin 3 mg, and after 12 weeks (P = 0.0082) for doxepin 1 mg. A summary of IVRS and CGI data is shown in Table 3.

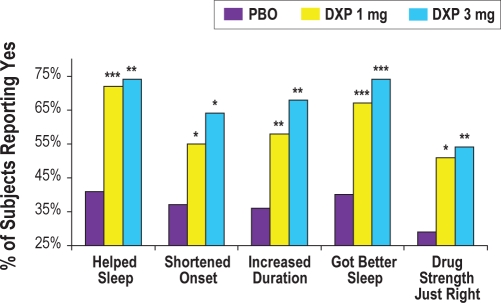

There was significant improvement on 4 of the 5 PGI items after 2 weeks and after 4 weeks for doxepin 3 mg (all P-values < 0.01; time to fall asleep not significantly different). For doxepin 1 mg, one of the items (lengthened total amount of sleep) was significantly improved after 2 weeks, and 2 items (helped them get better sleep and drug strength “just right”) were significantly improved after 4 weeks. After 12 weeks, there were significant improvements for both doxepin groups (all P-values < 0.05; Figure 4) on all 5 items of the PGI. These results indicate that at the end of the 12-week trial significantly more subjects in the doxepin 1 mg and 3 mg groups reported that the study drug: (1) helped them sleep, (2) shortened the time it took to fall asleep, (3) lengthened the total amount of time asleep, (4) helped them get a better night's sleep, and (5) had a strength that was “just right.”

Figure 4.

Effects of doxepin 1 mg and 3 mg versus placebo on PGI scores after 85 nights of treatment; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 001.

There was significant improvement on the ISI total score at N15 (P = 0.0216), N29 (P = 0.0068), and N85 (P = 0.0056) for doxepin 3 mg. Additionally, daytime function ratings were significantly improved on N1 for doxepin 3 mg (P = 0.0282) and 1 mg (P = 0.0192) and on N85 for doxepin 3 mg (P = 0.0028) and 1 mg (P = 0.0102).

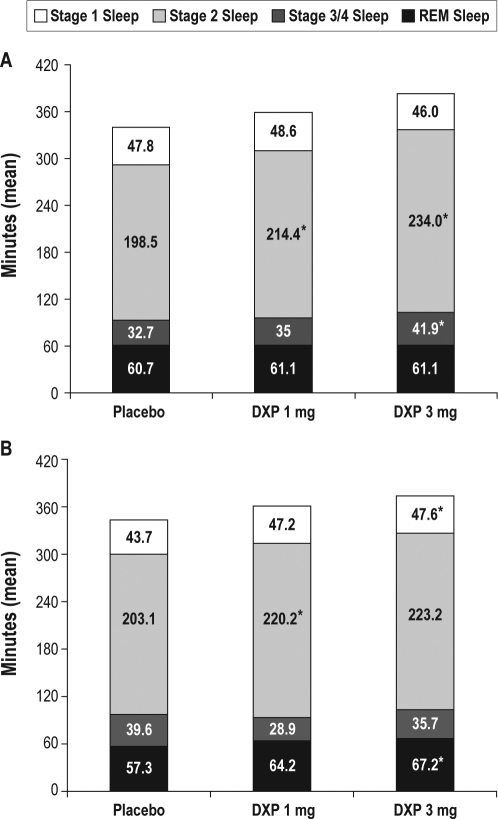

Sleep Architecture

In general, sleep stages were preserved compared with placebo, with no apparent evidence of suppression of REM duration (Figure 5). Across the trial, there were increases in the duration of stage 2 sleep for both doses of doxepin, which were significant at most time points. There were minimal to no changes in either stage 1 or stage 3/4 sleep. With regards to percentages within each sleep stage, there were minimal to no changes in any of these parameters across the trial. There were no significant differences in latency to REM sleep in either doxepin group compared with placebo, with the exception of N1 for doxepin 3 mg (placebo = 74.6; doxepin 1 mg = 83.6; doxepin 3 mg = 94.8; P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Effects of doxepin 1 mg and 3 mg on sleep stages in Night 1 (panel A) and Night 85 (panel B). Mean number of minutes spent in each sleep stage on Night 1 and Night 85; *P < 0.05.

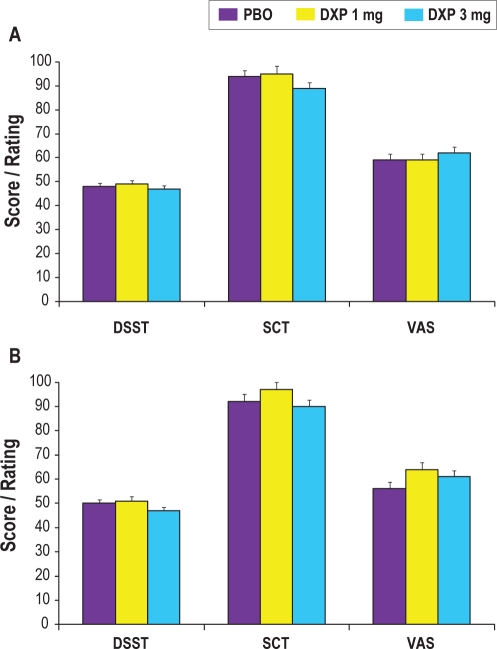

Next-Day Residual Effects

There were no significant differences between placebo and either dose of doxepin on any of the measures assessing objective psychomotor function (DSST and SCT; Figure 6) or subjective next-day alertness (VAS) or drowsiness at any time point during the trial.

Figure 6.

Effects of doxepin 1 mg and 3 mg on next-day residual sedation parameters in Night 1 (panel A) and Night 85 (panel B). VAS data are inverted for consistency with DSST and SCT results and data reflect the mean score (on the DSST and SCT) or rating of alertness (VAS).

Safety and Tolerability

Rates of treatment-emergent AEs were lower in subjects treated with doxepin compared with placebo, with 52% of subjects in the placebo group, 40% of subjects in the doxepin 1 mg group, and 38% of subjects in the doxepin 3 mg group experiencing an AE (Table 4). The most common AEs were headache and somnolence. Though there was an increased incidence of hypertension AEs in the doxepin 3 mg group, none of these events were considered to be related to study drug. Four subjects (2 [3%] in the doxepin 1 mg group and 2 [2%] in the doxepin 3 mg group) reported a total of 5 serious adverse events during the trial. None of these events were considered to be related to study drug.

Table 4.

Summary of adverse events reported by more than 2% of subjects in any treatment group

| Parameter | Placebo | Doxepin 1 mg | Doxepin 3 mg |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects with any adverse event | 52% | 40% | 38% |

| Headache | 14% | 3% | 6% |

| Somnolence | 5% | 5% | 2% |

| Diarrhea | 2% | 3% | 0% |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 1% | 3% | 1% |

| Urinary tract infection | 2% | 3% | 0% |

| Sinusitis | 1% | 4% | 0% |

| Hypertension | 0% | 1% | 4% |

| Gastroenteritis | 0% | 0% | 4% |

Overall, rates of study discontinuation were lower in the 2 doxepin groups compared with placebo (placebo = 14%; doxepin 1 mg = 9%; doxepin 3 mg = 10%). Additionally, there were either the same or fewer subjects who withdrew from the study due to an AE in the doxepin groups compared with placebo (placebo = 4%; doxepin 1 mg = 1%; doxepin 3 mg = 4%). None of the AEs leading to discontinuation in the doxepin groups were considered to be related to study drug.

There were no reports of complex sleep behaviors, memory impairment, or cognitive disorder in any doxepin-treated subject. Adverse events potentially associated with anticholinergic effects (e.g., dry mouth, blurred vision) were rare and occurred at a similar incidence across treatment groups.

No clinically meaningful changes were observed in mean laboratory values, ECGs, vital sign measurements, body weight, or physical examination findings. Overall, doxepin was well tolerated, with no apparent dose-related effects on safety and a lower overall rate of AEs and study discontinuations as compared to placebo.

DISCUSSION

Though insomnia is common and often associated with important consequences in elderly adults, data regarding the use of sleep agents in this population are relatively limited. There have been only four controlled trials of hypnotic agents in older adults including PSG assessment, and all were limited in duration.27–30 The present placebo-controlled study assessed the 12-week efficacy and safety of doxepin 1 mg and 3 mg in generally healthy elderly adults with chronic primary insomnia using both PSG and self-report measures. Twelve weeks of nightly use of doxepin 1 mg and 3 mg resulted in significant improvements in PSG-defined sleep maintenance (WASO) and early morning awakening (WTAS, SE % Last Quarter) endpoints that persisted through the final hour of assessment. There also were significant improvements in several patient-reported measures of sleep onset (LSO, PGI) and sleep duration (sTST). Improvements in sleep were evident on the first night of treatment and were sustained at 12 weeks for most parameters. In addition to these sleep effects, treatment with doxepin 1 mg and 3 mg resulted in significant improvement on clinician-rated assessments of insomnia severity and therapeutic effect and patient-rated measures of therapeutic effect, beginning as early as the first assessment time point (3 mg dose), with continued improvement at the final assessment time point (both doses). In terms of safety, both doses of doxepin were well tolerated, with no apparent dose-related adverse effects, including no evidence of next-day residual impairment (based on the measures used in the study) and a lower overall rate of AEs and study discontinuations compared to placebo.

The sleep maintenance efficacy seen in the present study is intriguing, in part because the significant improvements in WASO were not accompanied by reductions in NAW. In virtually all previous insomnia trials there was a strong positive relationship between these two variables, with either both being significant or both not being signficant.31–36 Results from this study suggest that doxepin 1 mg and 3 mg reduce the duration of time spent awake after an arousal without suppressing arousability. This pattern of WASO improvement with no change to NAW is consistent with the results from two previous primary insomnia trials of doxepin 1 mg, 3 mg, and 6 mg—one in the elderly and one in younger adults.21,22

The significance of the effect on wake time without a change in number of awakenings and the basis for this finding is unclear. This finding does, however, suggest that low-dose doxepin has some specificity in terms of clinical effects. Perhaps this reflects that, in contrast to the majority of agents used in practice that act via the GABA receptor complex, low-dose doxepin does not globally suppress wake-promoting systems, but appears to selectively block one of a number of parallel wake promoting systems.

In the present study, the sleep effects that lasted through the final hour of the night were not accompanied by evidence of next-day residual impairment, based on data from the DSST, SCT, and VAS. Upon awakening, subjects treated with doxepin 1 mg or 3 mg had DSST and SCT scores comparable to placebo, and reported comparable levels of alertness on the VAS. There also appeared to be no clinical evidence of drug accumulation across the assessment period, with similar results on all residual effect measures at the initial and final assessment time points. These findings replicate the prior finding in older insomnia patients in a smaller study of doxepin at doses of 1 mg, 3 mg, and 6 mg.22 Together these studies provide the best evidence available that a medication can effectively address the sleep maintenance and early morning sleep problems in older adults without impairing their function the following morning. The mechanism by which this occurs has not been established. However, we speculate this reflects that the blockade of histamine receptors by low-dose doxepin does not globally suppress wake-promoting systems, as occurs with GABA-ergic agents, but selectively blocks one of a number of parallel wake promoting systems. It is important that future research better test this hypothesis of no next-day residual effects with doxepin use by explicitly assessing the occurrence of falls and by including a larger battery of psychomotor assessments.

The findings of this study suggest that doxepin led to significant overall improvement in insomnia compared with placebo. This was evident on a number of global measures of insomnia syndrome severity including the ISI, the CGI severity and improvement scales and the PGI.

The goal of insomnia treatment is two-fold. The first is to reduce night time insomnia symptoms and the second is to reduce insomnia-related daytime impairment. Although the current study did not include objective measures of daytime function, several patient- and clinician-rated scales were used that assessed various aspects of perceived daytime effects. These included the ISI, the CGI-Severity and Improvement scales, a patient-rated Likert scale assessing daytime function, and the PGI scale. There were significant improvements to the ISI at the 3 mg dose at Weeks 2, 4, and 12. Additionally, there were significant improvements on the CGI-Severity and the CGI-Improvement scales beginning as early as the first assessment time point (3 mg dose), with continued improvement at the final assessment time point (both doses). By the end of the trial, clinicians rated insomnia symptoms as nearly one category less severe in the doxepin 3 mg group than in the placebo group (Figure 7). These data were supported by significant improvements for both doses in all PGI items by the end of the trial. Taken together, these results indicate that both patients and clinicians perceived clear sleep benefits following 12 weeks of therapy, and suggest improvement in daytime function. The efficacy in this study on these parameters speaks to the clinical relevance of the sleep effects.

Figure 7.

Effects of doxepin 1 mg and 3 mg versus placebo on CGI-Severity scores at Baseline, Week 2, and Week 12; the data reflect the mean clinician rating.

Doxepin 1 mg and 3 mg were well tolerated in this 12-week trial. Overall, AEs were infrequent and the incidence of individual AEs in the doxepin groups was comparable to placebo, with low study withdrawal rates. In contrast to previous trials using higher doses of doxepin for insomnia,37,38 the adverse event profile did not suggest the presence of weight gain/increased appetite, anticholinergic effects or somnolence. Other safety results (e.g., vital signs, electrocardiograms, physical examinations, and clinical laboratory values) were comparable across the three groups, and there was no evidence of significant REM suppression.

A recent review of the safety and tolerability data in elderly insomnia clinical trials identified a triad of frequently reported AEs: headache, somnolence, and dizziness.39 Examination of the same AEs in the present study indicates that patients in the highest doxepin dose group (3 mg) had lower rates of headache and somnolence compared with placebo, with no reported dizziness. This side-effect profile may reflect the selective H1 antagonism of low-dose doxepin, however, further research will be needed to determine if this is the case.40

The safety profile seen in the current trial is important considering the concerns that many physicians have about prescribing sedative-hypnotics to elderly adults with insomnia. These patients represent a vulnerable population for which sleep aids with a low risk/benefit ratio are desirable. The data from the study reported here provide strong evidence that doxepin 1 mg and 3 mg have a favorable risk/benefit ratio that is sustained over at least 12 weeks of nightly treatment, and suggest that these doses may represent a desirable alternative in this population because of the overall lack of evidence of CNS effects, and because there has been no evidence thus far of cognitive, psychomotor, and memory impairment.

The present study represents the longest placebo-controlled, double-blind study of an insomnia treatment in older adults diagnosed with primary insomnia. To date, it is also the longest study carried out in the elderly where PSG outcome measures were employed. Doxepin 1 mg and 3 mg significantly improved measures of sleep onset (patient reported), sleep duration, sleep quality, and global treatment outcomes over the 12-week study period. These doses of doxepin were well tolerated, with low discontinuation rates across the trial, no evidence of REM suppression or anticholinergic effects, and no reports of complex sleep behaviors or amnesia. Most relevant for this patient population, doxepin 1 mg and 3 mg significantly improved endpoints associated with sleep maintenance and early morning awakenings, the primary sleep complaints among elderly adults,41 without evidence of next-day residual effects. In summary, these data suggest that doxepin 1 mg and 3 mg are effective and appear to be well-tolerated in elderly subjects with chronic primary insomnia.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This study was fully-funded and supported by Somaxon Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (San Diego, CA), which markets doxepin for insomnia. Dr. Krystal has received research support from NIH, Sanofi-Aventis, Cephalon, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Neurocrine, Pfizer, Sepracor, Somaxon, Takeda, Transcept, Respironics, Neurogen, Evotec, Astellas, and Neuronetics and has consulted for Actelion, Arena, Astellas, Axiom, AstraZeneca, BMS, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Jazz, Johnson and Johnson, King, Merck, Neurocrine, Neurogen, Novartis, Organon, Ortho-McNeil-Janssen, Pfizer, Respironics, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Sepracor, Somaxon, Takeda, Transcept, Astellas, Research Triangle Institute, and Kingsdown Inc. Dr. Durrence is a previous employee of Somaxon Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Sharf has participated in clinical studies sponsored by Organon, Merck, Eli Lilly, Cephalon, and Sepracor. Dr. Jochelson is a previous employee of and consultant to Somaxon Pharmaceuticals. Ms. Rogowski is a previous employee of Somaxon Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Ludington is an employee of Somaxon Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Roth has received grants from Aventis, Cephalon, GlaxoSmithKline, Neurocrine, Pfizer, Sanofi, Schering-Plough, Sepracor, Somaxon, Syrex, Takeda, TransOral, Wyeth, and Xenoport. He has served as a consultant for Abbott, Acadia, Acoglix, Actelion, Alchemers, Alza, Ancil, Arena, AstraZeneca, Aventis, AVER, BMS, BTG, Cephalon, Cypress, Dove, élan, Eli Lilly, Evotec, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Hypnion, Impax, Intec, Intra-Ceullular, Jazz, Johnson and Johnson, King, Lundbeck McNeil, MediciNova, Merck, Neurim, Neurocrine, Neurogen, Novartis, Orexo, Organon, Prestwick, Proctor and Gamble, Pfizer, Purdue, Resteva, Roche, Sanofi, Schering Plough, Sepracor, Servier, Shire, Somaxon, Syrex, Takeda, TransOral, Vanda, Vivometrics, Wyeth, Yamanuchi, and Xenoport. Additionally, Dr. Roth has served as a speaker for Cephalon, Sanofi, and Takeda.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. pp. 599–604. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lichstein KL, Durrence HH, Taylor DJ, et al. Epidemiology of sleep: age, gender, and ethnicity. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbam; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drake CL, Roehrs T, Roth T. Insomnia causes, consequences, and therapeutics: an overview. Depress Anxiety. 2003;18:163–76. doi: 10.1002/da.10151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Janson C, Lindberg E, Gislason T, Elmasry A, Boman G. Insomnia in men-a 10-year prospective population based study. Sleep. 2001;24:425–30. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.4.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:97–111. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2002.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foley D, Ancoli-Israel S, Britz P, et al. Sleep disturbances and chronic disease in older adults – Results of the 2003 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Survey. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:497–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hart RP, Morin CM, Best AM. Neuropsychological performance in elderly insomnia patients. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 1995;2:268–78. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reynolds CF, 3rd, Buysse DJ, Kupfer DJ. Treating insomnia in older adults: taking a long-term view. JAMA. 1999;281:1034–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.11.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roth T, Ancoli-Israel S. Daytime consequences and correlates of insomnia in the United States: results of the 1991 National Sleep Foundation Survey. II. Sleep. 1999;22(Suppl 2):S354–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krystal A. A compendium of placebo-controlled trials of the risks/benefits of pharmacological treatments for insomnia: the empirical basis for U.Sclinical practice. Sleep Med Rev. 2009;13(4):265–274. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCrae CS, Rowe MA, Tierney CG, et al. Sleep complaints, subjective and objective sleep patterns, health, psychological adjustment, and daytime functioning in community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol. 2005;60B:182–9. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.4.p182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCrae CS, Wilson NM, Durrence HH, et al. ‘Young old’ and ‘old old’ poor sleepers with and without insomnia insomnia complaints. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54:11–19. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00543-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hohagen F, Kappler C, Schramm E, et al. Sleep onset insomnia, sleep maintaining insomnia and insomnia with early morning awakening – temporal stability of subtypes in a longitudinal study on general practice attenders. Sleep. 1994;17:551–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balter MB, Uhlenhuth EH. New epidemiologic findings about insomnia and its treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 1992;53(Suppl):34–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kramer M. Hypnotic medication in the treatment of chronic insomnia: non nocere!Doesn't anyone care? Sleep Med Rev. 2000;4:529–41. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2000.0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohayon M. Epidemiological study of insomnia in the general population. Sleep. 1996;19(suppl):S7–S15. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.suppl_3.s7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krystal AD, Walsh JK, Laska E, et al. Sustained efficacy of eszopiclone over 6 months of nightly treatment: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in adults with chronic insomnia. Sleep. 2003;26:793–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.7.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krystal AD, Erman M, Zammit GK, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of zolpidem extended-release 12.5 mg, administered 3 to 7 nights per week for 24 weeks, in patients with chronic primary insomnia: a 6-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicenter study. Sleep. 2008;31:79–89. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walsh JK, Krystal AD, Amato DA, et al. Nightly treatment of primary insomnia with eszopiclone for six months: effect on sleep, quality of life, and work limitations. Sleep. 2007;30:959–68. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.8.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buysse DJ. Opening up new avenues for insomnia treatment research: Comment on Krystal AD, Walsh JK; Laska E, et al: sustained efficacy of eszopiclone over 6 months of nightly treatment: Results of a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled study in adults with chronic insomnia. Sleep. 2003;26:786–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.7.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roth T, Rogowski R, Hull S, et al. Efficacy and safety of doxepin 1, 3 and 6 mg in adults with primary insomnia. Sleep. 2007;30:1555–61. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.11.1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scharf M, Rogowski R, Hull S, et al. Efficacy and safety of doxepin 1, 3 and 6 mg in elderly patients with primary insomnia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1557–64. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rechtschaffen A, Kales A, editors. A manual of standardized terminology, techniques and scoring system for sleep stages of human subjects. Los Angeles, CA: Brain Information Service/Brain Research Institute, UCLA; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Institute of Mental Health. 028 CGI. Clinical Global Impressions. In: Guy W, editor. Rockville, MD: ECDEU Assessment for psychopharmacology rev. ed.; 1976. pp. 217–22. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morin CM. Insomnia: psychological assessment and management. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wechsler DA. Manual for the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roth TG, Roehrs TA, Koshorek GL, et al. Hypnotic effects of low doses of quazepam in older insomniacs. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;17:401–6. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199710000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roehrs T, Zorick F, Wittig R, et al. Efficacy of a reduced triazolam dose in elderly insomniacs. Neurobiol Aging. 1985;6:293–6. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(85)90006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCall VW, Erman M, Krystal AD, et al. A polysomnography study of eszopiclone in elderly patients with insomnia. Curr Med Res Opinion. 2006;22:1633–42. doi: 10.1185/030079906X112741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walsh JK, Soubrane C, Roth T. Efficacy and safety of zolpidem extended release in elderly primary insomnia patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:44–57. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181256b01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ware JC, Walsh JK, Scharf MB, et al. Minimal rebound insomnia after treatment with 10-mg zolpidem. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1997;20:116–25. doi: 10.1097/00002826-199704000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walsh JK, Erman M, Erwin CW, et al. Subjective hypnotic efficacy of trazodone and zolpidem in DSMIII-R primary insomnia. Hum Psychopharmacol. 1998;13:191–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scharf MB, Roth T, Vogel GW, et al. A multicenter, placebo-controlled study evaluating zolpidem in the treatment of chronic insomnia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55:192–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hedner J, Yaeche R, Emilien G, et al. Zaleplon shortens subjective sleep latency and improves subjective sleep quality in elderly patients with insomnia. The Zaleplon Clinical Investigator Study Group. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15:704–12. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200008)15:8<704::aid-gps183>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elie R, Ruther E, Farr I, et al. Sleep latency is shortened during 4 weeks of treatment with zaleplon, a novel nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic [Zaleplon Clinical Study Group] J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:536–44. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n0806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walsh JK, Vogel GW, Scharf M, et al. A five week, polysomnographic assessment of zaleplon 10 mg for the treatment of primary insomnia. Sleep Med. 2000;1:41–9. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(99)00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hajak G, Rodenbeck A, Voderholzer U, et al. Doxepin in the treatment of primary insomnia: A placebo-controlled, double-blind, polysomnographic study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:453–63. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n0609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roth T, Zorick F, Wittig R, et al. The effects of doxepin HCl on sleep and depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1982;43:366–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dolder C, Nelson M, McKinsey J. Use of non-benzodiazepine hypnotics in the elderly: are all agents the same? CNS Drugs. 2007;21:389–405. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200721050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stahl S. Selective histamine h1 antagonism: novel hypnotic and pharmacologic actions challenge classical notions of antihistamines. CNS Spectrums. 2008 doi: 10.1017/s1092852900017089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Sleep Foundation. 2002 Sleep in America poll. [Accessed December 10]. Last update: 2002. Available at: www/sleepfoundation.org/_content/hottopics/2002SleepInAmericaPoll.pdf.