Abstract

Studies have indicated that the neurotransmitter nitric oxide (NO) mediates leptin’s effects in the neuroendocrine reproductive axis. However, the neurons involved in these effects and their regulation by leptin is still unknown. We aimed to determine whether NO neurons are direct targets of leptin and by which mechanisms leptin may influence neuronal NO synthase (nNOS) activity. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate diaphorase activity and leptin-induced phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 immunoreactivity were coexpressed in subsets of neurons of the medial preoptic area, the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus, the arcuate nucleus (Arc), the dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (DMH), the posterior hypothalamic area, the ventral premammillary nucleus (PMV), the parabrachial nucleus, and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve. Fasting blunted nNOS mRNA expression in the medial preoptic area, Arc, DMH, PMV, and posterior hypothalamic area, and this effect was not restored by acute leptin administration. No difference in the number of neurons expressing nNOS immunoreactivity was noticed comparing hypothalamic sections of fed (wild type and ob/ob), fasted, and fasted leptin-treated mice. However, we found that in states of low leptin levels, as in fasting, or lack of leptin, as in ob/ob mice, the number of neurons expressing the phosphorylated form of nNOS is decreased in the Arc, DMH, and PMV. Notably, acute leptin administration to fasted wild-type mice restored the number of phosphorylated form of nNOS neurons to that observed in fed wild-type mice. Herein we identified the first-order neurons potentially involved in NO-mediated effects of leptin and demonstrate that leptin regulates nNOS activity predominantly through posttranslational mechanisms.

Subsets of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) neurons are direct targets of leptin; leptin administration regulates nNOS activity through post-translational mechanisms.

The adipocyte-derived hormone leptin is a key component in the regulation of the long-term body weight and energy homeostasis (1,2). Mice and humans carrying loss-of-function mutations in the genes that encode leptin or leptin receptors (LepRs) are severely obese and diabetic and display a variety of autonomic dysfunctions (3,4,5,6,7,8). Leptin signaling deficiency also causes hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and infertility (9,10). Leptin treatment, but not weight loss alone, restores the metabolic and reproductive dysfunctions of mice and humans deficient to leptin (4,11,12,13).

Although the LepR is expressed in a variety of tissues (14,15), gene-targeting studies have indicated that the brain exerts a predominant role in leptin’s physiology (16,17). Therefore, studies have been focused on defining the specific brain sites and the neuronal populations that are major targets of leptin (18,19,20). For example, it is now well determined that the arcuate nucleus (Arc) neurons are important players relaying leptin’s effects in energy and glucose homeostases (1,2). The Arc contains two defined populations of leptin-targeted neurons with opposite effects on energy homeostasis. One population coexpresses proopiomelanocortin (POMC) and cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) and is stimulated by leptin, whereas the second population coexpresses neuropeptide Y and agouti-related peptide and is inhibited by leptin (21,22,23,24,25,26). Nevertheless, leptin action in these neurochemically defined populations of neurons explain only part of its physiological effects, indicating that other brain sites or other subsets of neurons also play a role (27,28,29). One of these extra-Arc sites is the ventromedial nucleus of hypothalamus (VMH), in which leptin-responsive neurons coexpress the steroidogenic factor-1 (30,31). Taking advantage of this colocalization, two independent groups used the steroidogenic factor-1 (SF-1) gene promoter to generate genetically engineered mice models with targeted deletion of LepRs selectively in VMH neurons. These mice displayed mild obese phenotype, comparable with that observed after disruption of LepR in POMC neurons (27,30,31).

Several studies have suggested that leptin’s effect in the reproductive neuroendocrine axis is mediated by the neurotransmitter nitric oxide (NO). Leptin stimulates GnRH secretion from hypothalamic explants, an effect that is blocked by NO inhibitors (32,33,34). Moreover, the leptin-induced preovulatory LH surge is also disrupted by coadministration of NO synthase inhibitors (35).

NO is a soluble gas that is generated from the amino acid arginine by the activity of NO synthases. Thus, the expression of NO-synthesizing enzymes [neuronal NO synthase (nNOS) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate diaphorase (NADPHd)] is a useful tool to identify potential NO-producing neurons (36,37,38). These NOergic neurons are distributed throughout the brain including areas that also express the LepR, such as the Arc, the lateral hypothalamic area (LHA), the VMH, the dorsomedial nucleus of hypothalamus (DMH), the ventral premammillary nucleus (PMV), and the nucleus of the solitary tract (38,39,40,41). However, the exact brain sites and the neuronal populations involved in NO-mediated leptin’s effects have not been revealed. Moreover, because these neurons have not been identified, it has been difficult to determine the mechanisms by which leptin induce NO production and ultimately affect the reproductive axis.

In the present study, we identified the subsets of leptin-responsive neurons that express NO-synthesizing enzymes. We determined whether conditions of low leptin levels, as in fasting, or lack of leptin, as in ob/ob mice, cause changes in nNOS mRNA expression, in the number of nNOS immunoreactive neurons and/or in the phosphorylated form of nNOS. We show that NOergic neurons responsive to leptin are located in several brain nuclei and that leptin modulates nNOS activity through posttranslational modifications.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Adult female C57BL/6 and ob/ob (C57BL/6-Lepob; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) mice were housed in the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center Animal Resource Center, in a light- (12 h on/12 h off) and temperature- (21–23 C) controlled environment. They were fed standard chow diet (Harlan Teklad Global Diet, Indianapolis, IN) unless otherwise mentioned and had free access to water. All experiments were carried out in accordance with the guidelines established by the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as well as with those established by the University of Texas Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Experimental design

Experiment 1: identification of NOergic neurons responsive to leptin

To identify the NOergic neurons directly responsive to leptin, we performed colocalization studies using the expression of NADPHd activity (NO synthesizing enzyme) as a marker for NO neurons and leptin-induced phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (pSTAT3). Adult female C57BL/6 mice were fasted for 24 h and received ip recombinant murine leptin (n = 7; 2.5 μg/g; provided by Dr. A. F. Parlow, Harbor-University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center, Torrance, CA; through the National Hormone and Peptide Program) or pyrogen free saline (n = 3; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Mice were perfused 40 min after injection and brains were collected for histological analysis. Preliminary experiments showed that 2.5 μg/g of ip leptin increased significantly serum leptin concentration in 24-h fasted adult C57BL/6 female mice, 40 min after the injection (0.88 ± 0.21 ng/ml in fasted saline treated mice vs. 25.95 ± 0.08 ng/ml in fasted leptin treated mice, P < 0.0001, n = 8; unpaired two tailed Student’s t test).

Experiment 2: assessment of changes in nNOS mRNA expression and nNOS immunoreactivity by fasting or leptin treatment

We initially assessed whether fasting induces changes in nNOS gene expression or in the number of nNOS immunoreactive neurons in hypothalamic sites in which we found coexpression of NADPHd and leptin-induced pSTAT3 immunoreactivity (ir). Subsequently we assessed whether acute leptin treatment restores or induce changes in nNOS gene expression or in the number of nNOS immunoreactive neurons in those sites. To do that, adult female C57BL/6 mice on diestrus I were fasted for 24 h and received ip recombinant murine leptin (2.5 μg/g) or saline (on diestrus II). Control groups consisted of ad libitum-fed wild-type mice perfused on diestrus II and ad libitum-fed ob/ob female mice, both treated with saline (n = 6/group). Mice were perfused 40 min after injections and brains were collected for histological analysis. One series of brain sections were submitted to in situ hybridization histochemistry to detect changes in nNOS mRNA expression, and another series were submitted to immunohistochemistry to detect changes in the number of nNOS immunoreactive neurons. The estrous cycle was monitored by analysis of the vaginal cytology.

Experiment 3: assessment of leptin-induced phosphorylation of nNOS in specific hypothalamic nuclei

Previous studies have shown that estrogen may change the phosphorylated state of nNOS (42). To equalize estrogen effects, female C57BL/6 mice were monitored for estrous cycle and, on diestrus I, they were fasted for 24 h before leptin or saline treatment. We assessed phosphorylation of nNOS (pnNOS) in the brains of mice treated with two different doses of leptin (2.5 or 5.0 μg/g) and perfused at three different time points after leptin administration (40, 60, and 120 min). Before conducting the experiments, we performed a test of specificity for the pnNOS antisera in histological sections. Brain sections of fed wild-type mice were submitted to preadsorption tests and analysis of the colocalization between NADPHd activity and pnNOS-ir. Then a series of sections from fasted wild-type mice treated with leptin or saline and those from fed wild-type and ob/ob mice were submitted to immunoperoxidase reaction to detect pnNOS-ir. Labeled neurons in specific hypothalamic nuclei were quantified.

Perfusion and histology

Mice were deeply anesthetized with ketamine (5 mg per 100 g) and xylazine (1 mg per 100 g) and perfused transcardially with saline followed by 10% buffered formalin. Brains were collected and postfixed in the same fixative for 2 h and cryoprotected overnight at 4 C in 0.1 m PBS (pH 7.4), containing 20% sucrose prepared with diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water. Brains were cut (25 μm sections) in the frontal plane in a freezing microtome. Five series were collected in antifreeze solution and stored at −20 C.

Histochemistry and immunohistochemistry

To investigate the distribution of neurons that coexpress NADPHd activity and leptin-induced pSTAT3-ir, brain sections from wild-type mice treated with leptin or saline were rinsed overnight in PBS and incubated in a solution containing 0.02% of β-NADPH (Sigma) and 0.02% of nitroblue tetrazolium (Sigma) in 1 m Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) with 0.1% Triton X-100 at 37 C, in the dark, as we have done before (43). After 2–5 h, the reaction was terminated with rinses in PBS. For pSTAT3-ir detection, sections were pretreated with 1% hydrogen peroxide containing 1% sodium hydroxide in water for 20 min. After rinses in PBS, sections were incubated in 0.3% glycine and 0.03% lauryl sulfate for 10 min each. Then sections were blocked in 3% normal donkey serum (Jackson Laboratories) for 1 h, followed by incubation in anti-pSTAT3 antisera raised in rabbit (1:2000; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) for 48 h. Subsequently sections were incubated for 1 h in biotin-conjugated IgG donkey antirabbit (1:1000; Jackson Laboratories) and for 1 h in avidin-biotin complex (1:500; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The peroxidase reaction was performed using 0.05% diaminobenzidine and 0.03% hydrogen peroxide. Sections were mounted onto gelatin-coated slides, dried overnight, dehydrated in ethanol, cleared in xylene, and coverslipped with DPX (Sigma-Aldrich).

The immunohistochemistry reactions to detect nNOS-ir or pnNOS-ir were performed as described, except that we used the anti-nNOS antisera (1:8000; ImmunoStar Inc., Hudson, WI; no. 24287) or anti-pnNOSS1416 antisera (1:500; Abcam, Cambridge, MA; ab5583), both raised in rabbit. The anti-nNOS antisera have been used and the specificity has been tested before (44). The anti-pnNOSS1416 antisera recognize the phosphorylation of a serine residue equivalent to S1416 of the human nNOS that is homologous to S1412 residue of the mouse nNOS. As a control for specificity of the anti-pnNOS antisera, we performed a preadsorption test using the immunogen synthetic peptide [CNRLRSE(pS)IAFIEESK], corresponding to amino acids 1411–1425 of the human nNOS that is homologous to amino acids 1406–1420 of the mouse nNOS (Abcam; ab41773). The preadsorption test was performed using the anti-pnNOS antisera (1:500, 2 μg/ml) pre-incubated overnight in three different concentrations of the blocking peptide (1.0, 0.5, and 0.25 μg/ml). A positive control was performed in parallel, using nonpreadsorbed anti-pnNOS antisera. These specificity tests were performed in brain sections of fed wild-type mice. As an additional control, we assessed the coexpression of NADPHd activity and pnNOS-ir in the brain of fed wild-type mice. For this purpose, we performed the NADPHd labeling reaction followed by immunoperoxidase to detect pnNOS-ir.

In situ hybridization histochemistry

The in situ hybridization procedure was a modification of that previously reported (39,45). Before hybridization, brain sections from fasted saline- or leptin-treated mice as well as from fed wild-type and fed ob/ob mice treated with saline were mounted onto SuperFrost plus slides (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ) and stored at −20 C. Before hybridization, sections were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 20 min, dehydrated in ascending concentrations of ethanol, cleared in xylene for 15 min, rehydrated in descending concentrations of ethanol, and placed in prewarmed 0.01 m sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Sections were pretreated for 10 min in a microwave, dehydrated in ethanol, and air dried. The nNOS riboprobe was generated by in vitro transcription with 35S-uridine 5-triphosphate. The 35S-labeled probe was diluted (106 dpm/ml) in hybridization solution containing 50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, and 1× Denhardt’s solution (Sigma). The hybridization solution (120 μl) was applied to each slide and they were incubated overnight at 56 C. Sections were then treated with 0.002% ribonuclease A solution and submitted to stringency washes in decreasing concentrations of sodium chloride/sodium citrate buffer. Sections were dehydrated and enclosed in x-ray film cassettes with BMR-2 film (Kodak, Rochester, NY) for 48 h. Slides were dipped in NTB2 autoradiographic emulsion (Kodak), dried, and stored at 4 C for 14 d. Slides were developed with a D-19 developer (Kodak).

The nNOS probe was produced from PCR fragments amplified with ExTaq DNA polymerase (Takara, Shiga, Japan) from cDNA generated with the SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for RT-PCR from total mouse hypothalamic RNA. Because Nos1 transcription generates a diversity of mRNAs (46), we designed the nNOS in situ hybridization probe to include part of the exon 26, which encodes the amino acids sequence containing the residue S1412 of the mouse nNOS. Our nNOS probe is equivalent to positions 3625–4136 of GenBank accession no. NM_008712.2, comprising exons 22–26 of the mouse Nos1 gene. Hybridization with the sense probe was performed as control.

Quantification of single- and dual-labeled neurons and hybridization signal

Dual-labeled neurons coexpressing NADPHd activity and pSTAT3-ir or NADPHd activity and pnNOS-ir as well as single labeled neurons expressing nNOS or pnNOS-ir were identified. Quantification of numbers of pnNOS-ir cells and percentage of colocalization between NADPHd activity and pSTAT3-ir were determined in the medial preoptic area (MPA), Arc, DMH, posterior hypothalamic area (PH), and PMV. Cells were counted in one side of a determined rostro-to-caudal level of each nucleus (47).

The hybridization signal was estimated by the analysis of the integrated OD (IOD) using the ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij), as we have done before (48). Dark-field photomicrographs were acquired using the same illumination and exposure time for every section. No image editing was processed before quantifications. The IOD values for nNOS mRNA were calculated as the total IOD of a constant area subtracting the background from adjacent nuclei that did not express nNOS.

Production of photomicrographs and data analysis

Brain sections were analyzed in a Zeiss Axioplan microscope (Carl Zeiss, New York, NY). Photomicrographs were produced by capturing images with a digital camera (Axiocam; Zeiss) mounted directly on the microscope. Adobe Photoshop CS3 image-editing software (San Jose, CA) was used to integrate photomicrographs into plates. Only sharpness, contrast, and brightness were adjusted. Drawings were produced using a camera lucida. The Adobe Illustrator CS3 software was used to incorporate drawings into plates.

Data are expressed as mean ± sem. One-way ANOVA followed by the pairwise Newman-Keuls test were used for the comparison among the experimental groups. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 5 software (San Diego, CA), and an α-value of 0.05 was considered in all analyses.

Results

Leptin induces pSTAT3-ir in neurons expressing NADPHd activity

To identify the NOergic neurons directly responsive to leptin, we assessed coexpression of NADPHd activity as a marker for NO production (36,37,38,43) and leptin-induced pSTAT3-ir as a maker for direct leptin action (40,48,49). We have chosen to use NADPHd activity in this experiment because the best available and validated antisera against nNOS and pSTAT3 are both made in rabbit, yielding potential cross-reactivity and unspecific labeling. We assessed the number of single- and dual-labeled neurons that express NADPHd activity and leptin-induced pSTAT3-ir. In the hypothalamus, we found colocalization of NADPHd and pSTAT3-ir in various nuclei. Considering the total number of NADPHd positive neurons, we found that 30–40% of those neurons localized in the lateral aspects of the MPA (MPAl), the Arc, the posterior part of the ventral subdivision of the DMH (DMHv), and the PH coexpressed pSTAT3-ir (Table 1 and Figs. 1, A–D and 2, A–C). In addition, approximately 65% of NADPHd positive neurons in the PMV also expressed pSTAT3-ir (Figs. 1E and 2C).

Table 1.

Quantification of neurons that coexpress NADPHd activity and leptin-induced pSTAT3-ir in hypothalamic nuclei

| Nuclei | Atlas levels | NADPHd cells | pSTAT3-ir cells | Dual-labeled cells | NADPHd cells expressing pSTAT3-ir (%) | pSTAT3-ir cells expressing NADPHd (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPAl | 18 | 62.8 ± 11.3 | 43.0 ± 6.3 | 19.4 ± 3.0 | 34.0% ± 6.9 | 46.0% ± 5.5 |

| Arc | 31 | 31.7 ± 1.9 | 129.3 ± 13.3 | 9.3 ± 2.0 | 29.5% ± 5.9 | 7.2% ± 1.3 |

| DMHv | 31 | 142.3 ± 23.5 | 127.5 ± 10.4 | 46.7 ± 5.5 | 35.0% ± 5.1 | 36.2% ± 2.0 |

| PH | 33 | 80.7 ± 8.2 | 39.7 ± 5.0 | 30.4 ± 3.5 | 39.6% ± 4.7 | 78.8% ± 5.4 |

| PMV | 33 | 209.4 ± 8.0 | 186.8 ± 4.9 | 136.2 ± 4.4 | 65.2% ± 1.6 | 73.0% ± 2.4 |

We quantified the number of cells that express NADPHd activity, pSTAT3-ir, and both (dual labeled cells). Percentage of NADPHd cells that coexpress pSTAT3-ir and the percentage of pSTAT3-ir cells that coexpress NADPHd activity (n = 3–7 cases/nucleus) was estimated. Data are expressed as mean ± sem. The atlas level designation corresponds to those described by Paxinos and Franklin (47).

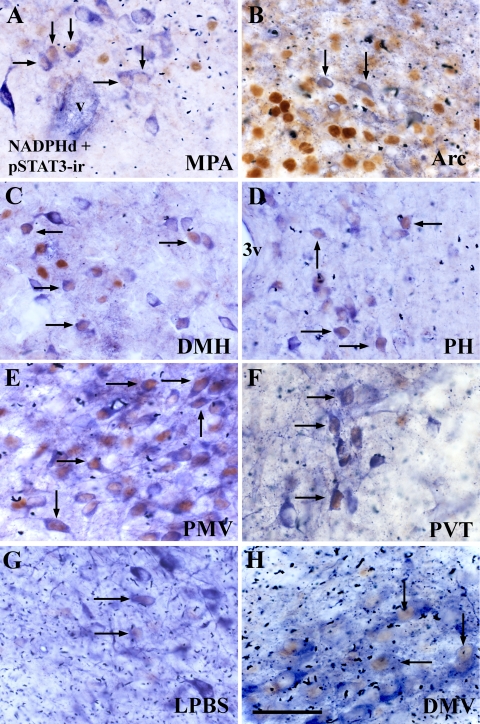

Figure 1.

Colocalization of NADPHd activity (a NO synthase) and leptin-induced pSTAT3-ir in the female mouse brain. Adult female wild-type mice were fasted for 24 h and perfused 40 min after ip injection of leptin (2.5 μg/g). A–H, Bright-field photomicrographs showing neurons that coexpress NADPHd (blue cytoplasm) and pSTAT3-ir (brown nuclei) in the MPA (A), the Arc (B), the DMH (C), the PH (D), the PMV (E), i the paraventricular nucleus of thalamus (PVT, F), the LPBS (G), the DMV (H). Arrows indicate double-labeled neurons. 3v, Third ventricle; v, blood vessel. Scale bar, 40 μm.

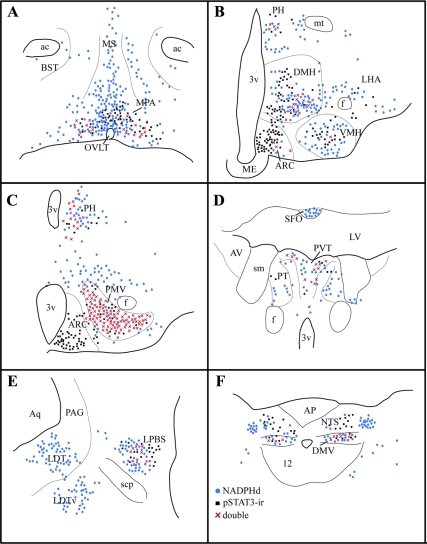

Figure 2.

Schematic drawings illustrating the distribution of cells that coexpress NADPHd activity and leptin-induced pSTAT3-ir. A–F, Distribution of single- and dual-labeled neurons in the MPA (A), the Arc (B), the DMH (B), the PH (C), the PMV (C), the paraventricular nucleus of thalamus (PVT, D), the LPBS (E), and the DMV (F). Single-labeled neurons are represented with blue circles (NADPHd) or black squares (STAT3-ir), and dual-labeled neurons are represented with red crosses. 12, Hypoglossal nucleus; 3v, third ventricle; ac, anterior commissure; AP, area postrema; Aq, aqueduct; AV, anteroventral nucleus of thalamus; BST, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis; f, fornix; LDT, laterodorsal tegmental nucleus; LHA, lateral hypothalamic area; LV, lateral ventricle; ME, medial eminence; MS, medial septal nucleus; mt, mammillothalamic tract; NTS, nucleus of the solitary tract; OVLT, vascular organ of laminae terminalis; PAG, periaqueductal gray; PT, parataenial nucleus; SFO, subfornical organ; scp, superior cerebellar peduncle; sm, stria medullaris; VMH, ventromedial nucleus of hypothalamus.

We also estimated the percentage of pSTAT3-ir neurons that coexpressed NADPHd activity. We found that approximately 46% of pSTAT3-positive neurons in the MPAl, 7% in the Arc, 36% in the DMHv, and 73–79% in the PH and the PMV also expressed NADPHd (Table 1). Furthermore, we observed some degree of colocalization between NADPHd activity and pSTAT3-ir outside the hypothalamus. These included the anterior subdivision of the paraventricular nucleus of thalamus (Figs. 1F and 2D), the superior lateral subdivision of parabrachial nucleus (LPBS; Figs. 1G and 2E), and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve (DMV; Figs. 1H and 2F). Few occasional cells coexpressing NADPHd activity and pSTAT3-ir were found in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH), the retrochiasmatic area, the ventrolateral subdivision of the VMH, the LHA, the dorsal nucleus of raphe, the periaqueductal gray matter, and the nucleus of the solitary tract (data not shown).

Fasted mice treated with saline showed very few pSTAT3-ir neurons in the Arc and virtually no coexpression with NADPHd activity in any of the sites described above.

Fasting-induced decrease in nNOS mRNA expression is not restored by leptin treatment

Acute leptin treatment induces an increase in NO production from hypothalamic neurons (33). Thus, we performed a series of experiments to evaluate the mechanisms by which leptin exerts this acute effect. Initially we analyzed the distribution of nNOS mRNA in the mouse brain by in situ hybridization to test the specificity of our probe. As observed in the rat brain (41), nNOS is expressed in many neuronal populations including the cerebral cortex, striatum, amygdala, and various hypothalamic and hindbrain nuclei. Specifically for the purpose of the present study, we found an identical pattern of distribution between nNOS mRNA (riboprobe signal) and NADPHd activity. This includes the MPA, the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, the supraoptic nucleus, the Arc, the VMH, the DMH, the lateral hypothalamic area, the PMV, the PH, and the dorsal premammillary nucleus. No hybridization signal was observed after hybridization with the sense probe (data not shown).

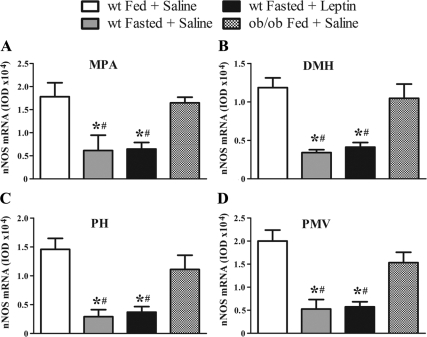

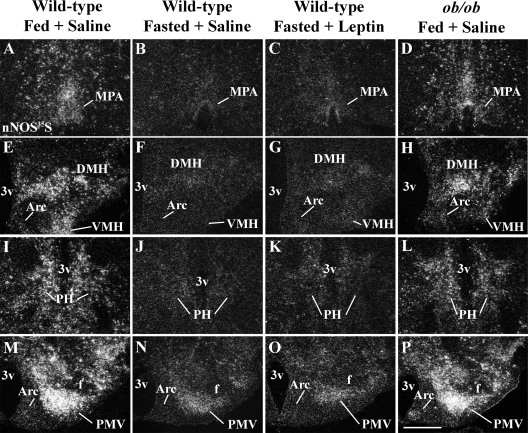

We next assessed whether fasting (a state of low circulating levels of leptin) induces changes in nNOS mRNA expression in hypothalamic areas in which we found coexpression of NAPDHd activity and leptin-induced pSTAT3-ir. We observed that 24 h of food restriction caused a strong suppression (P < 0.001) of nNOS mRNA expression in the MPA (Figs. 3A and 4, A and B), in the Arc (data not shown), the DMH (Figs. 3B and 4, E and F), the PH (Figs. 3C and 4, I and J), and the PMV (Figs. 3D and 4, M and N) when compared with ad libitum-fed saline-treated mice. Acute leptin administration (40 min before perfusion) to fasted mice did not restore nNOS mRNA levels in any of these nuclei (Figs. 3 and 4, C, G, K, and O). Notably, we observed that leptin-deficient ad libitum-fed ob/ob mice showed a comparable amount of nNOS mRNA expression with that found in control fed wild-type mice, which was also statistically higher when compared with fasted (saline treated or leptin treated) wild-type mice (Figs. 3 and 4, D, H, L, and P). Our findings suggest that the blunted expression of nNOS mRNA observed in food-restricted mice was not caused by changes in circulating leptin levels.

Figure 3.

Bar graphs showing the quantification of hybridization signal (nNOS mRNA) by IOD of fed saline-treated, fasted saline-treated, and fasted leptin-treated (2.5 μg/g) wild-type mice as well as fed ob/ob saline-treated mice (n = 4–6/group). Observe that fasting reduced nNOS mRNA expression in the MPA (A), the DMH (B), the PH (C), and the PMV (D), compared with fed wild-type (wt) mice. This reduction was not restored by acute leptin treatment. Fed leptin deficient (ob/ob) saline-treated mice showed a comparable expression of nNOS mRNA with fed saline-treated wild-type mice. Data in bar graphs are expressed as mean ± sem. *, Statistically different (P < 0.001) from fed saline-treated wild-type mice; #, statistically different (P < 0.001) from fed saline-treated ob/ob mice. We used one-way ANOVA followed by the pairwise Newman-Keuls test.

Figure 4.

Fasting-induced suppression of nNOS mRNA is not restored by leptin treatment. Dark-field photomicrographs showing nNOS mRNA expression by in situ hybridization (nNOS35S ribroprobe, silver grains) in the MPA (A–D), the DMH (E–H), the PH (I-L), and the PMV (M-P) of fed saline-treated, fasted saline-treated, and fasted leptin-treated (2.5 μg/g) wild-type mice as well as fed ob/ob saline-treated mice (n = 4–6/group). 3v, Third ventricle; f, fornix. Scale bar, 400 μm.

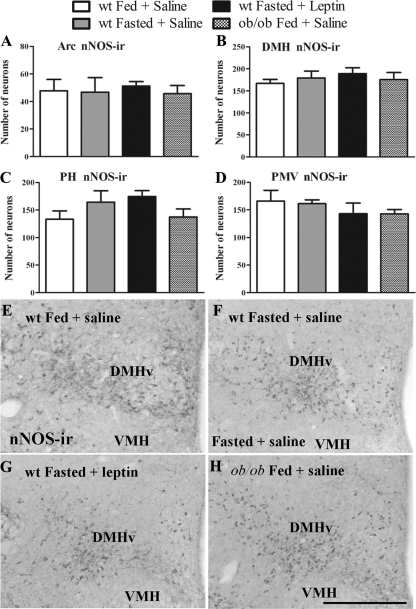

Fasting does not change the number of hypothalamic neurons expressing nNOS-ir

Because we found that 24-h-fasted mice showed a decrease in nNOS mRNA expression in several hypothalamic nuclei, we assessed whether these changes in gene expression could result in decreased number of neurons expressing nNOS-ir in those hypothalamic nuclei. We found no difference in the numbers of nNOS-immunoreactive neurons in all sites analyzed comparing fed, fasted (saline treated and leptin treated) wild-type and ob/ob mice (Fig. 5, A–D). These include the MPAl (data not shown), the Arc (Fig. 5A), the DMHv (Fig. 5, B and E-H), the PH (Fig. 5C), and the PMV (Fig. 5D). In accordance, we also found that the number of neurons expressing NADPHd activity in these same areas was similar between fasted and fed wild-type mice (data not shown).

Figure 5.

States of low leptin levels cause no change in the number of neurons expressing nNOS-ir. A–D, Bar graphs showing the number of nNOS-ir neurons in the Arc (A), the DMHv (B), the PH (C), and the PMV (D) of fed, fasted saline-treated, fasted leptin-treated wild-type mice, and ob/ob mice. E–H, Bright-field photomicrographs showing the distribution of nNOS-ir neurons in the DMHv of fed (E), fasted saline-treated (F), fasted leptin-treated (G) wild types, and fed ob/ob mice (H). Data in bar graphs are expressed as mean ± sem. Scale bar (E and F), 400 mm.

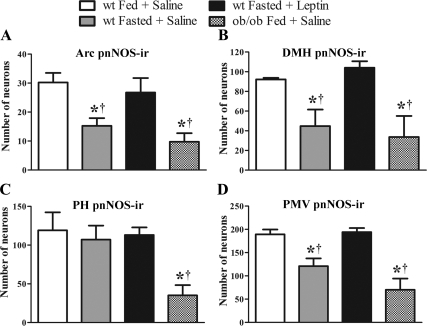

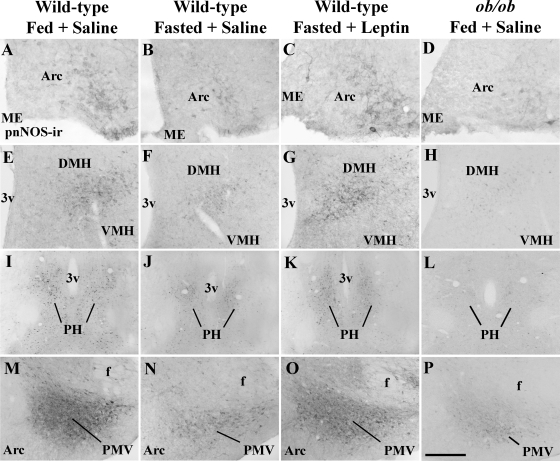

Increased pnNOS-ir after leptin treatment

The activity of nNOS is regulated by posttranslational modifications, such as phosphorylation of amino acid residues (42,50). Therefore, we assessed whether phosphorylation of nNOS is modulated by changing levels of leptin. We used the pnNOS antisera previously described (50) to identify alterations in the localization and number of pnNOS-ir neurons in fed and fasted conditions.

Initially, to further validate the pnNOS antisera in histological sections, we performed colocalization studies in brain sections of female wild-type mice and compared the pattern of distribution of NADPHd activity and pnNOS-ir. We found that virtually all pnNOS-ir neurons coexpressed NADPHd activity (Supplemental Fig. 1, published on The Endocrine Society’s Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org), but only subsets of neurons expressing NADPHd coexpressed pnNOS-ir. The degree of coexpression was variable in different brain areas, but it was consistent among all mice analyzed (Supplemental Results and Supplemental Table 1). In addition, the preadsorption test resulted in complete neutralization of the anti-pnNOS by its immunogen synthetic peptide (Supplemental Fig. 2). These results confirm the specificity of the pnNOS antisera.

Subsequently we compared the number of nNOS-immunoreactive neurons in hypothalamic sections of fed saline-treated, fasted saline-treated, and fasted leptin-treated wild-type mice as well as fed saline-treated ob/ob mice. Fasted saline-treated wild-type mice showed a significant (P < 0.05) reduction in the number of neurons expressing pnNOS-ir in the Arc (Figs. 6A and 7, A–D), the DMH (Figs. 6B and 7, E–H), and the PMV (Figs. 6D and 7, M–P) when compared with fed saline-treated wild-type mice. No difference in the number of pnNOS-ir neurons was noticed in the PH (Figs. 6C and 7, I–L). We also found that ob/ob mice showed a significant reduction in the number of neurons expressing pnNOS-ir in the Arc, DMH, PH, and PMV when compared with fed saline-treated wild-type mice (Figs. 6 and 7). Notably, acute leptin infusion in fasted wild-type mice (40 min before perfusion) restored the number of cells expressing pnNOS-ir in the Arc, DMH, and PMV to the levels found in fed wild-type mice (Figs. 6 and 7). The same results were obtained in brain sections of mice perfused 60 and 120 min after leptin treatment, except for the Arc neurons that did not reach statistical significance (Supplemental Fig. 3). No difference in the number of pnNOS-ir neurons was observed in the MPAl comparing all groups (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Bar graphs showing the number of neurons expressing pnNOS-ir in hypothalamic nuclei. Note that fasting in wild-type mice reduced the number of neurons expressing pnNOS-ir in the Arc (A), the DMH (B), and the PMV (D) but not the PH (C), compared with fed wild-type mice. Leptin treatment (2.5 μg/g, 40 min before perfusion) restored the reduced pnNOS-ir expression in the Arc (A), the DMH (B), and the PMV (D). Leptin deficiency in ob/ob mice caused a similar reduction in pnNOS-ir to that observed in fasted wild-type mice. Data in the bar graphs are expressed as mean ± sem. *, Statistically different (P < 0.05) from fed saline-treated wild-type mice; †, statistically different (P < 0.05) from fasted leptin-treated wild-type mice. We used one-way ANOVA followed by the pairwise Newman-Keuls test.

Figure 7.

Acute leptin treatment increases the number of neurons expressing pnNOS-ir in hypothalamic nuclei. Bright-field photomicrographs showing the expression of pnNOS-ir in the Arc (A–D), the DMH (E–H), the PH (I–L), and the PMV (M–P) in brain sections of fed saline-treated, fasted saline-treated, and fasted leptin-treated (2.5 μg/g, 40 min before perfusion) wild-type mice as well as fed ob/ob saline-treated mice (n = 4–5/group). 3v, Third ventricle; f, fornix; ME, median eminence. Scale bar (A-D), 100 μm; (E-L), 200 μm; (M–P), 400 μm.

Discussion

In the present study, we identified the NOergic neurons directly responsive to leptin. These neurons are not located in a specific nucleus but rather comprise subsets of NO-producing neurons in various brain sites. In the hypothalamus, we found moderate to high coexpression of NO synthases and leptin-induced pSTAT3 in the MPAl, the Arc, the DMHv, the PH, and the PMV. We also showed that 24 h of food restriction decreased nNOS mRNA expression in these hypothalamic nuclei. Acute leptin administration did not restore nNOS mRNA levels to that found in fed control mice. Moreover, this decrease in nNOS gene expression did not alter the numbers of neurons expressing nNOS-ir. Nevertheless, 24 h of fasting caused a decrease in the number of hypothalamic neurons expressing pnNOS in the Arc, the DMHv, and the PMV. Leptin administration restored pnNOS-ir in these sites.

NO-mediated effects of leptin

The role played by NO as a neurotransmitter was investigated in vivo by knocking out the gene that encodes the nNOS (Nos1) (51,52). These studies in association with others that used pharmacological manipulations established that NO neurotransmission is associated with behavioral responses to environmental cues and with the regulation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonad axis (51,52,53,54,55,56). Loss-of-function mutation of the Nos1 gene causes hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and infertility in mice (52). The downstream mechanisms underlying this phenotype have not been revealed. One possibility is a deficient release of GnRH in these mice as a dense plexus of nNOS immunoreactive fibers is located in the median eminence and NO directly regulates GnRH secretion from the terminals (57,58). In line with this, several studies have suggested that NO action relaying leptin’s effect on GnRH secretion is attained by direct stimulation of GnRH terminals in the mediobasal hypothalamus (32,33). However, whether leptin acts directly on NO-producing neurons or engage interneurons that in turn impinge on NOergic neurons has not been determined. We observed that leptin directly targets subsets of NOergic neurons in several brain sites. Of those, the Arc and the PMV have been explored as potential sites of leptin action on reproduction (28,29,43,48,59,60,61,62).

The role played by Arc neurons linking leptin and reproduction has been controversial. Stereotaxic delivery of LepR into the Arc of LepR-deficient obese Koletsky rats normalized their estrous cycle (63). In contrast, endogenous reactivation of LepR only in the Arc of mice null for LepR did not rescue their infertility phenotype (28). Both studies relied on stereotaxic injections and therefore may have targeted different population of neurons. Thus, more selective studies in chemically defined populations of neurons that express POMC/CART or neuropeptide Y/agouti-related peptide have been performed, but no compelling evidences have been offered demonstrating that these Arc neurons are required for leptin’s effects on reproduction (27,29,59). Recently a population of leptin-responsive neurons that expresses Kiss1), a potent regulator of the reproductive function, has been described (60). Leptin-deficient ob/ob male mice display decreased Kiss1 mRNA in the Arc, a condition that is partially restored by leptin administration (60). However, the action of these leptin-responsive Kiss1 neurons in mediating leptin action in the reproductive neuroendocrine axis has not been directly tested. Here we show that subsets of NO-positive neurons in the Arc are also direct targets of leptin. These NOergic neurons comprise a segregated population of leptin-responsive neurons (Donato, J. and C. F. Elias, personal observations). Although they consist of a small group of neurons, studies will be necessary to determine whether they are part of the circuitry controlling leptin’s effect on GnRH secretion.

Studies from our and other groups have suggested that the PMV is a key site linking leptin and the reproductive neuroendocrine axis (48,61,62,64). The PMV expresses a large population of leptin-responsive neurons and innervate areas involved in reproductive control (20,39,40,48,61,62,65,66,67). We recently showed that bilateral lesions of the PMV precluded leptin stimulatory effects on LH secretion during fasting (48). Of note, NO-positive neurons of the PMV of male rats express androgen receptors, CART-ir and are stimulated by opposite sex odor exposure (43,68). Our present data also demonstrates that high numbers of NOergic neurons of the PMV are direct targets of leptin. Thus, collectively these findings support the concept that NO-positive neurons in the PMV are well located to integrate signals from sexually relevant environmental cues (odor), steroid milieu, and energy reserves. Our findings further suggest that the PMV is a prime candidate to relay NO-mediated effects of leptin on GnRH secretion.

We also identified several other sites in which leptin may directly induce NO production. Of those, the MPA, the DMH, and particularly the PH displayed moderate to high numbers of NO neurons responsive to leptin. The role played by the DMH and PH neurons in leptin physiology or leptin stimulation of GnRH secretion is unclear. However, several studies have indicated that NO neurons of the preoptic area are part of the circuitry controlling male sexual behavior and female cyclicity (69,70,71,72). Whether these are the same neurons that are targeted by leptin is not known.

Changing levels of leptin modulates nNOS activity by posttranslational modifications

To identify the mechanisms by which acute leptin administration may induce NO production/secretion from hypothalamic explants (32,33), we assessed alterations in nNOS mRNA levels, nNOS-ir, and the pnNOS in identified neurons. NO is produced by the activity of NO synthase, which uses NADPHd as a cofactor (37). The NOS is, ultimately, the enzyme responsible for NO production, whereas the NADPH is a cofactor in many different enzymatic process (e.g. in various NADPH dependent enzymes) and therefore may be influenced by factors independent from NO production or nNOS activity. In our study, we used NADPHd as a maker for NOergic neurons (shown by others and validated in the present manuscript) to avoid cross-reactivity of the antisera (as mentioned). However, changes in nNOS mRNA, number of nNOS-ir neurons as well as the pnNOS was used to detect direct alterations of the NO system. We found that fasting reduced nNOS mRNA expression in all hypothalamic nuclei in which NO synthase is coexpressed with leptin-induce pSTAT3. However, acute leptin administration did not restore nNOS mRNA in these sites, suggesting that if leptin exerts any effect on nNOS mRNA levels, it is not attained through a rapid response. Curiously, nNOS mRNA expression was not significantly different between fed wild-type mice and fed leptin-deficient ob/ob mice, suggesting that the decrease in nNOS mRNA after fasting is not related to changes in circulating levels of leptin.

In the present study, food restriction was used as a condition of low leptin levels (9,73). However, fasting also affects several other hormones (e.g. insulin, catecholamines) and nutrients (e.g. glucose, free fatty acids, amino acids) (9,10,74) that could account for the changes in nNOS expression observed. Thus, additional studies will be necessary to isolate the factor(s) that may lead to the suppression of nNOS mRNA expression in those areas. Of note, previous studies have reported that 48-h fasted male rats showed decreased nNOS mRNA expression in the PVH and supraoptic nucleus, which was prevented by daily intracerebroventricular infusion of leptin (75). That study and the present one are not directly comparable because experimental designs, species, gender, route of leptin administration, and hypothalamic sites assessed are all different. However, the PVH contains leptin’s second-order neurons, which mediate part of its effects in feeding behavior and autonomic and neuroendocrine regulation (1,2). Thus, it is reasonable to consider that leptin may also regulate nNOS activity via indirect pathways.

A recent work showed that phosphorylation of the S1412 nNOS residue increases nNOS activity and NO production (42). In that study, the authors showed that nNOS phosphorylation increases significantly during the afternoon of proestrus, which coincides with the preovulatory LH surge (42). Interestingly, the decrease of leptin levels during fasting is thought to be the main cause of suppression of LH secretion observed in this condition because fasting-induced decrease in the LH is restored by leptin administration (9,10). Our results demonstrate that although fasting has not altered the number of nNOS-ir neurons, it did reduce the number of pnNOS-ir cells in the Arc, the DMH, and the PMV. Notably, acute leptin administration to fasted wild-type mice restored the number of pnNOS-ir cells, suggesting that leptin induces phosphorylation of nNOS in specific hypothalamic sites. The physiological effects resulted from this event still need to be directly assessed, but our findings indicate that leptin may potentially induce NO production by increasing the phosphorylation of nNOS in defined hypothalamic neurons. Because subsets of NO-positive neurons in these nuclei are direct targets of leptin, our data also support the model that leptin exert this effect by direct signaling onto these NOergic neurons.

The intracellular pathways by which leptin exerts this effect is not clear. Previous studies reported that insulin-induced phosphorylation of nNOS in the nucleus of the solitary tract is a function of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling pathways (50). This is of interest because LepR signaling also recruits the PI3K intracellular pathway (76,77). Moreover, studies have suggested that rapid (acute) effects of leptin are dependent on the PI3K activity as pharmacological or genetic disruption of the PI3K pathway prevents leptin-induced depolarization of POMC neurons and leptin-induced changes in food intake (76,77). This is worth mentioning because leptin stimulation of LH secretion in vivo is a rapid effect (32,48,78). Thus, it will be of interest to assess whether NO-mediated leptin effects to induce GnRH and, ultimately, LH secretion are dependent on phosphorylation of nNOS by activation of PI3K-Akt signaling pathways. In this regard, the present study will be of great value because it identifies the specific NO-positive neuron populations directly responsive to leptin and therefore highlights potential hypothalamic sites in which this effect may take place.

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Dunning, C. Lee, and L. Brule for technical support. Leptin assays were performed by the Metabolic Core at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, TX) (National Institutes of Health Grant 1PL1DK081182-01). C.F.E. is the Distinguished Scholar in Medical Research (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX).

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant HD061539 (to C.F.E.), the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifico e Tecnológico, Brazil) Grant 201804/2008-5 (to R.F.), and the Regent’s Scholar Research Award and the President’s Council Research Award from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (to C.F.E.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online September 29, 2010

Abbreviations: Arc, Arcuate nucleus; CART, cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript; DMH, dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus; DMHv, ventral subdivision of the DMH; DMV, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve; IOD, integrated OD; ir, immunoreactivity; LepR, leptin receptor; LHA, lateral hypothalamic area; LPBS, superior lateral subdivision of parabrachial nucleus; MPA, medial preoptic area; MPAl, lateral aspects of the MPA; NADPH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; NADPHd, NADPH diaphorase; nNOS, neuronal NO synthase; NO, nitric oxide; PH, posterior hypothalamic area; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PMV, ventral premammillary nucleus; pnNOS, phosphorylation of nNOS; POMC, proopiomelanocortin; pSTAT3, phosphorylation of signal transducer and activator of transcription-3; PVH, paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus; VMH, ventromedial nucleus of hypothalamus.

References

- Schwartz MW, Porte Jr D 2005 Diabetes, obesity, and the brain. Science 307:375–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmquist JK, Coppari R, Balthasar N, Ichinose M, Lowell BB 2005 Identifying hypothalamic pathways controlling food intake, body weight, and glucose homeostasis. J Comp Neurol 493:63–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM 1994 Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature 372:425–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campfield LA, Smith FJ, Guisez Y, Devos R, Burn P 1995 Recombinant mouse OB protein: evidence for a peripheral signal linking adiposity and central neural networks. Science 269:546–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halaas JL, Gajiwala KS, Maffei M, Cohen SL, Chait BT, Rabinowitz D, Lallone RL, Burley SK, Friedman JM 1995 Weight-reducing effects of the plasma protein encoded by the obese gene. Science 269:543–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tartaglia LA, Dembski M, Weng X, Deng N, Culpepper J, Devos R, Richards GJ, Campfield LA, Clark FT, Deeds J, Muir C, Sanker S, Moriarty A, Moore KJ, Smutko JS, Mays GG, Wool EA, Monroe CA, Tepper RI 1995 Identification and expression cloning of a leptin receptor, OB-R. Cell 83:1263–1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague CT, Farooqi IS, Whitehead JP, Soos MA, Rau H, Wareham NJ, Sewter CP, Digby JE, Mohammed SN, Hurst JA, Cheetham CH, Earley AR, Barnett AH, Prins JB, O'Rahilly S 1997 Congenital leptin deficiency is associated with severe early-onset obesity in humans. Nature 387:903–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clément K, Vaisse C, Lahlou N, Cabrol S, Pelloux V, Cassuto D, Gourmelen M, Dina C, Chambaz J, Lacorte JM, Basdevant A, Bougnères P, Lebouc Y, Froguel P, Guy-Grand B 1998 A mutation in the human leptin receptor gene causes obesity and pituitary dysfunction. Nature 392:398–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahima RS, Prabakaran D, Mantzoros C, Qu D, Lowell B, Maratos-Flier E, Flier JS 1996 Role of leptin in the neuroendocrine response to fasting. Nature 382:250–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan JL, Heist K, DePaoli AM, Veldhuis JD, Mantzoros CS 2003 The role of falling leptin levels in the neuroendocrine and metabolic adaptation to short-term starvation in healthy men. J Clin Invest 111:1409–1421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chehab FF, Lim ME, Lu R 1996 Correction of the sterility defect in homozygous obese female mice by treatment with the human recombinant leptin. Nat Genet 12:318–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barash IA, Cheung CC, Weigle DS, Ren H, Kabigting EB, Kuijper JL, Clifton DK, Steiner RA 1996 Leptin is a metabolic signal to the reproductive system. Endocrinology 137:3144–3147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooqi IS, Matarese G, Lord GM, Keogh JM, Lawrence E, Agwu C, Sanna V, Jebb SA, Perna F, Fontana S, Lechler RI, DePaoli AM, O'Rahilly S 2002 Beneficial effects of leptin on obesity, T cell hyporesponsiveness, and neuroendocrine/metabolic dysfunction of human congenital leptin deficiency. J Clin Invest 110:1093–1103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamorano PL, Mahesh VB, De Sevilla LM, Chorich LP, Bhat GK, Brann DW 1997 Expression and localization of the leptin receptor in endocrine and neuroendocrine tissues of the rat. Neuroendocrinology 65:223–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei H, Okano HJ, Li C, Lee GH, Zhao C, Darnell R, Friedman JM 1997 Anatomic localization of alternatively spliced leptin receptors (Ob-R) in mouse brain and other tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:7001–7005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Zhao C, Cai X, Montez JM, Rohani SC, Feinstein P, Mombaerts P, Friedman JM 2001 Selective deletion of leptin receptor in neurons leads to obesity. J Clin Invest 108:1113–1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Luca C, Kowalski TJ, Zhang Y, Elmquist JK, Lee C, Kilimann MW, Ludwig T, Liu SM, Chua Jr SC 2005 Complete rescue of obesity, diabetes, and infertility in db/db mice by neuron-specific LEPR-B transgenes. J Clin Invest 115:3484–3493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MW, Seeley RJ, Campfield LA, Burn P, Baskin DG 1996 Identification of targets of leptin action in rat hypothalamus. J Clin Invest 98:1101–1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmquist JK, Elias CF, Saper CB 1999 From lesions to leptin: hypothalamic control of food intake and body weight. Neuron 22:221–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias CF, Kelly JF, Lee CE, Ahima RS, Drucker DJ, Saper CB, Elmquist JK 2000 Chemical characterization of leptin-activated neurons in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol 423:261–281 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias CF, Aschkenasi C, Lee C, Kelly J, Ahima RS, Bjorbaek C, Flier JS, Saper CB, Elmquist JK 1999 Leptin differentially regulates NPY and POMC neurons projecting to the lateral hypothalamic area. Neuron 23:775–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung CC, Clifton DK, Steiner RA 1997 Proopiomelanocortin neurons are direct targets for leptin in the hypothalamus. Endocrinology 138:4489–4492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin DG, Breininger JF, Schwartz MW 1999 Leptin receptor mRNA identifies a subpopulation of neuropeptide Y neurons activated by fasting in rat hypothalamus. Diabetes 48:828–833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias CF, Lee C, Kelly J, Aschkenasi C, Ahima RS, Couceyro PR, Kuhar MJ, Saper CB, Elmquist JK 1998 Leptin activates hypothalamic CART neurons projecting to the spinal cord. Neuron 21:1375–1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn TM, Breininger JF, Baskin DG, Schwartz MW 1998 Coexpression of Agrp and NPY in fasting-activated hypothalamic neurons. Nat Neurosci 1:271–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley MA, Smart JL, Rubinstein M, Cerdán MG, Diano S, Horvath TL, Cone RD, Low MJ 2001 Leptin activates anorexigenic POMC neurons through a neural network in the arcuate nucleus. Nature 411:480–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthasar N, Coppari R, McMinn J, Liu SM, Lee CE, Tang V, Kenny CD, McGovern RA, Chua Jr SC, Elmquist JK, Lowell BB 2004 Leptin receptor signaling in POMC neurons is required for normal body weight homeostasis. Neuron 42:983–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppari R, Ichinose M, Lee CE, Pullen AE, Kenny CD, McGovern RA, Tang V, Liu SM, Ludwig T, Chua Jr SC, Lowell BB, Elmquist JK 2005 The hypothalamic arcuate nucleus: a key site for mediating leptin’s effects on glucose homeostasis and locomotor activity. Cell Metab 1:63–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson JC, Hollopeter G, Palmiter RD 1996 Attenuation of the obesity syndrome of ob/ob mice by the loss of neuropeptide Y. Science 274:1704–1707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon H, Zigman JM, Ye C, Lee CE, McGovern RA, Tang V, Kenny CD, Christiansen LM, White RD, Edelstein EA, Coppari R, Balthasar N, Cowley MA, Chua Jr S, Elmquist JK, Lowell BB 2006 Leptin directly activates SF1 neurons in the VMH, and this action by leptin is required for normal body-weight homeostasis. Neuron 49:191–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham NC, Anderson KK, Reuter AL, Stallings NR, Parker KL 2008 Selective loss of leptin receptors in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus results in increased adiposity and a metabolic syndrome. Endocrinology 149:2138–2148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu WH, Kimura M, Walczewska A, Karanth S, McCann SM 1997 Role of leptin in hypothalamic-pituitary function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:1023–1028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu WH, Walczewska A, Karanth S, McCann SM 1997 Nitric oxide mediates leptin-induced luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) and LHRH and leptin-induced LH release from the pituitary gland. Endocrinology 138:5055–5058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynoso R, Cardoso N, Szwarcfarb B, Carbone S, Ponzo O, Moguilevsky JA, Scacchi P 2007 Nitric oxide synthase inhibition prevents leptin induced Gn-RH release in prepubertal and peripubertal female rats. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 115:423–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanobe H, Schiöth HB 2001 Nitric oxide mediates leptin-induced preovulatory luteinizing hormone and prolactin surges in rats. Brain Res 923:193–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson TM, Bredt DS, Fotuhi M, Hwang PM, Snyder SH 1991 Nitric oxide synthase and neuronal NADPH diaphorase are identical in brain and peripheral tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88:7797–7801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope BT, Michael GJ, Knigge KM, Vincent SR 1991 Neuronal NADPH diaphorase is a nitric oxide synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88:2811–2814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent SR, Kimura H 1992 Histochemical mapping of nitric oxide synthase in the rat brain. Neuroscience 46:755–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmquist JK, Bjørbaek C, Ahima RS, Flier JS, Saper CB 1998 Distributions of leptin receptor mRNA isoforms in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol 395:535–547 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott MM, Lachey JL, Sternson SM, Lee CE, Elias CF, Friedman JM, Elmquist JK 2009 Leptin targets in the mouse brain. J Comp Neurol 514:518–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwase K, Iyama K, Akagi K, Yano S, Fukunaga K, Miyamoto E, Mori M, Takiguchi M 1998 Precise distribution of neuronal nitric oxide synthase mRNA in the rat brain revealed by non-radioisotopic in situ hybridization. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 53:1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkash J, d'Anglemont de Tassigny X, Bellefontaine N, Campagne C, Mazure D, Buée-Scherrer V, Prevot V 2010 Phosphorylation of N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor-associated neuronal nitric oxide synthase depends on estrogens and modulates hypothalamic nitric oxide production during the ovarian cycle. Endocrinology 151:2723–2735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato Jr J, Cavalcante JC, Silva RJ, Teixeira AS, Bittencourt JC, Elias CF 2010 Male and female odors induce Fos expression in chemically defined neuronal population. Physiol Behav 99:67–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip YP, Capriotti C, Drill E, Tsai LH, Yip JW 2007 Cdk5 selectively affects the migration of different populations of neurons in the developing spinal cord. J Comp Neurol 503:297–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi T, Aschkenasi CJ, Lee CE, Mountjoy KG, Saper CB, Elmquist JK 2003 Expression of melanocortin 4 receptor mRNA in the central nervous system of the rat. J Comp Neurol 457:213–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Newton DC, Robb GB, Kau CL, Miller TL, Cheung AH, Hall AV, VanDamme S, Wilcox JN, Marsden PA 1999 RNA diversity has profound effects on the translation of neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:12150–12155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ 2001 The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 2nd ed. San Diego: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- Donato Jr J, Silva RJ, Sita LV, Lee S, Lee C, Lacchini S, Bittencourt JC, Franci CR, Canteras NS, Elias CF 2009 The ventral premammillary nucleus links fasting-induced changes in leptin levels and coordinated luteinizing hormone secretion. J Neurosci 29:5240–5250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates SH, Stearns WH, Dundon TA, Schubert M, Tso AW, Wang Y, Banks AS, Lavery HJ, Haq AK, Maratos-Flier E, Neel BG, Schwartz MW, Myers Jr MG 2003 STAT3 signalling is required for leptin regulation of energy balance but not reproduction. Nature 421:856–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang HT, Cheng WH, Lu PJ, Huang HN, Lo WC, Tseng YC, Wang JL, Hsiao M, Tseng CJ 2009 Neuronal nitric oxide synthase activation is involved in insulin-mediated cardiovascular effects in the nucleus tractus solitarii of rats. Neuroscience 159:727–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson RJ, Demas GE, Huang PL, Fishman MC, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Snyder SH 1995 Behavioural abnormalities in male mice lacking neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Nature 378:383–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyurko R, Leupen S, Huang PL 2002 Deletion of exon 6 of the neuronal nitric oxide synthase gene in mice results in hypogonadism and infertility. Endocrinology 143:2767–2774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretto M, López FJ, Negro-Vilar A 1993 Nitric oxide regulates luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone secretion. Endocrinology 133:2399–2402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceccatelli S, Hulting AL, Zhang X, Gustafsson L, Villar M, Hökfelt T 1993 Nitric oxide synthase in the rat anterior pituitary gland and the role of nitric oxide in regulation of luteinizing hormone secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:11292–11296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettori V, Belova N, Dees WL, Nyberg CL, Gimeno M, McCann SM 1993 Role of nitric oxide in the control of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone release in vivo and in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:10130–10134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettori V, Kamat A, McCann SM 1994 Nitric oxide mediates the stimulation of luteinizing-hormone releasing hormone release induced by glutamic acid in vitro. Brain Res Bull 33:501–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami S, Ichikawa M, Yokosuka M, Tsukamura H, Maeda K 1998 Glial and neuronal localization of neuronal nitric oxide synthase immunoreactivity in the median eminence of female rats. Brain Res 789:322–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevot V, Dehouck B, Poulain P, Beauvillain JC, Buée-Scherrer V, Bouret S 2007 Neuronal-glial-endothelial interactions and cell plasticity in the postnatal hypothalamus: implications for the neuroendocrine control of reproduction. Psychoneuroendocrinology 32:S46–S51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann JG, Teal TH, Clifton DK, Davis J, Hruby VJ, Han G, Steiner RA 2000 Differential role of melanocortins in mediating leptin’s central effects on feeding and reproduction. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 278:R50–R59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JT, Acohido BV, Clifton DK, Steiner RA 2006 KiSS-1 neurones are direct targets for leptin in the ob/ob mouse. J Neuroendocrinol 18:298–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rondini TA, Baddini SP, Sousa LF, Bittencourt JC, Elias CF 2004 Hypothalamic cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript neurons project to areas expressing gonadotropin releasing hormone immunoreactivity and to the anteroventral periventricular nucleus in male and female rats. Neuroscience 125:735–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leshan RL, Louis GW, Jo YH, Rhodes CJ, Münzberg H, Myers Jr MG 2009 Direct innervation of GnRH neurons by metabolic- and sexual odorant-sensing leptin receptor neurons in the hypothalamic ventral premammillary nucleus. J Neurosci 29:3138–3147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keen-Rhinehart E, Kalra SP, Kalra PS 2005 AAV-mediated leptin receptor installation improves energy balance and the reproductive status of obese female Koletsky rats. Peptides 26:2567–2578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcante JC, Bittencourt JC, Elias CF 2006 Female odors stimulate CART neurons in the ventral premammillary nucleus of male rats. Physiol Behav 88:160–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm U, Zou Z, Buck LB 2005 Feedback loops link odor and pheromone signaling with reproduction. Cell 123:683–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron E, Sachot C, Prevot V, Bouret SG 2010 Distribution of leptin-sensitive cells in the postnatal and adult mouse brain. J Comp Neurol 518:459–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canteras NS, Simerly RB, Swanson LW 1992 Projections of the ventral premammillary nucleus. J Comp Neurol 324:195–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokosuka M, Hayashi S 1996 Colocalization of neuronal nitric oxide synthase and androgen receptor immunoreactivity in the premammillary nucleus in rats. Neurosci Res 26:309–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull EM, Dominguez JM 2006 Getting his act together: roles of glutamate, nitric oxide, and dopamine in the medial preoptic area. Brain Res 1126:66–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu S, Kalra PS, Kalra SP 1998 Diurnal rhythm in cyclic GMP/nitric oxide efflux in the medial preoptic area of male rats. Brain Res 808:310–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima FB, Szawka RE, Anselmo-Franci JA, Franci CR 2007 Pargyline effect on luteinizing hormone secretion throughout the rat estrous cycle: correlation with serotonin, catecholamines and nitric oxide in the medial preoptic area. Brain Res 1142:37–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clasadonte J, Poulain P, Beauvillain JC, Prevot V 2008 Activation of neuronal nitric oxide release inhibits spontaneous firing in adult gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons: a possible local synchronizing signal. Endocrinology 149:587–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maffei M, Halaas J, Ravussin E, Pratley RE, Lee GH, Zhang Y, Fei H, Kim S, Lallone R, Ranganathan S, Kern PA, Friedman JM 1995 Leptin levels in human and rodent: measurement of plasma leptin and ob RNA in obese and weight-reduced subjects. Nat Med 1:1155–1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher TJ, Glaeser BS, Wurtman RJ 1984 Diurnal variations in plasma concentrations of basic and neutral amino acids and in red cell concentrations of aspartate and glutamate: effects of dietary protein intake. Am J Clin Nutr 39:722–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isse T, Ueta Y, Serino R, Noguchi J, Yamamoto Y, Nomura M, Shibuya I, Lightman SL, Yamashita H 1999 Effects of leptin on fasting-induced inhibition of neuronal nitric oxide synthase mRNA in the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of rats. Brain Res 846:229–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niswender KD, Morton GJ, Stearns WH, Rhodes CJ, Myers Jr MG, Schwartz MW 2001 Intracellular signalling. Key enzyme in leptin-induced anorexia. Nature 413:794–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JW, Williams KW, Ye C, Luo J, Balthasar N, Coppari R, Cowley MA, Cantley LC, Lowell BB, Elmquist JK 2008 Acute effects of leptin require PI3K signaling in hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin neurons in mice. J Clin Invest 118:1796–1805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walczewska A, Yu WH, Karanth S, McCann SM 1999 Estrogen and leptin have differential effects on FSH and LH release in female rats. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 222:170–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]