Abstract

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is the leading cause of infertility in reproductive-aged women with the majority manifesting insulin resistance. To delineate the causes of insulin resistance in women with PCOS, we determined changes in the mRNA expression of insulin receptor (IR) isoforms and members of its signaling pathway in tissues of adult control (n = 7) and prenatal testosterone (T)-treated (n = 6) sheep (100 mg/kg twice a week from d 30–90 of gestation), the reproductive/metabolic characteristics of which are similar to women with PCOS. Findings revealed that prenatal T excess reduced (P < 0.05) expression of IR-B isoform (only isoform detected), insulin receptor substrate-2 (IRS-2), protein kinase B (AKt), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ), hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL), and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) but increased expression of rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR (rictor), and eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E) in the liver. Prenatal T excess increased (P < 0.05) the IR-A to IR-B isoform ratio and expression of IRS-1, glycogen synthase kinase-3α and -β (GSK-3α and -β), and rictor while reducing ERK1 in muscle. In the adipose tissue, prenatal T excess increased the expression of IRS-2, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), PPARγ, and mTOR mRNAs. These findings provide evidence that prenatal T excess modulates in a tissue-specific manner the expression levels of several genes involved in mediating insulin action. These changes are consistent with the hypothesis that prenatal T excess disrupts the insulin sensitivity of peripheral tissues, with liver and muscle being insulin resistant and adipose tissue insulin sensitive.

Prenatal testosterone excess has tissue-specific effects on the expression levels of members of insulin signaling pathway in liver, muscle, and adipose tissue suggestive of reduced insulin sensitivity in liver and muscle and increased sensitivity in adipose tissue.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common cause of infertility in reproductive-aged women (1,2). Approximately 70% of women with PCOS develop insulin resistance and hence are at risk of developing type 2 diabetes (3). Insulin resistance in PCOS appears to be selective, affecting metabolic, but not mitogenic, actions of insulin as shown in both cultured skin fibroblasts and skeletal muscle (4,5). Insulin resistance in skeletal muscle of women with PCOS has been suggested to result from a post-binding defect in the insulin signaling pathway (5). Available evidence does not point to similar intrinsic defects in insulin signaling in the PCOS adipose cell lineage (6). Pathological states of insulin resistance have also been found to be related to mutations in the primary sequence of the insulin receptor (IR) gene leading to a decreased number of IR and consequent effect on the IR signal cascade (7,8,9).

The mechanisms underlying insulin responsiveness of target tissues in women with PCOS have been investigated at a functional level in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue by focusing on phosphorylated forms of insulin signaling molecules after stimulation with insulin. These studies have found that activity of ERK and mitogen-activated ERK (MEK), which is involved in serine phosphorylation of IR substrate (IRS)-1 (10,11) and inhibition of its association with phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K) (12), are increased in skeletal muscle in response to insulin in women with PCOS compared with control subjects (13). Similar intrinsic defects in insulin signaling have not been found in adipose tissue of women with PCOS (6). For obvious reasons, such investigations have not been carried out at the level of the liver.

Several animal models have evolved to understand the etiology of PCOS (14), which provide a resource for undertaking detailed mechanistic studies at multiple tissue levels. Prenatal testosterone (T)-treated sheep, the model chosen for this study, recapitulates the reproductive and metabolic characteristics of women with PCOS (15,16,17); they manifest oligo-/anovulation, progressive loss of cyclicity, LH excess, neuroendocrine feedback defects, and polycystic ovarian morphology as well as functional ovarian hyperandrogenism at the reproductive level and insulin resistance at the metabolic level. Using prenatal T-treated sheep as a model and focusing on liver, muscle, and adipose tissue, we tested the hypothesis that prenatal T excess has divergent and tissue-specific effects upon gene expression of IR isoforms and members of its signaling pathway.

Materials and Methods

Breeding, prenatal treatment, and maintenance

All procedures were approved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Michigan and were in conformity with the National Institutes of Health Guide for Use and Care of Animals. The details of breeder ewe maintenance, breeding, and lambing have been described in detail elsewhere (18). Briefly, prenatal T treatment consisted of twice-weekly injections of 100 mg T propionate (∼1.2 mg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO) in cottonseed oil (2 ml) from d 30–90 of gestation (term = 147 d). The concentrations of T achieved in the mother and female fetus are comparable to that of adult males and the early T rise seen in male fetuses, respectively (19). All animals were ovariectomized at the end of the second breeding season and tissues (liver, skeletal muscle, and abdominal fat) harvested during an artificial luteal phase after insertion of controlled internal drug-releasing implants containing progesterone (CIDR: device type-G, CIDR-G; InterAg, Hamilton, New Zealand; implanted sc). Before ovariectomy, all controls were cycling and prenatal T-treated females were oligo- or anovulatory. Liver specimens were obtained from the tip of the left lobe. The skeletal muscle was obtained from the vastus lateralis, abdominal fat was from mesenteric fat surrounding the ventral sac of the rumen, and care was given to procure samples from the same region with each animal. All tissues were washed with PBS, quick frozen, and stored at −80 C until processing.

Isolation of RNA and real-time PCR

RNA from the tissues under investigation (liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue) was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Purification of RNA was accomplished by deoxyribonuclease treatment and column clean-up (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). The purified RNA was evaluated spectrophotometrically and by denaturing formaldehyde gel electrophoresis. First-strand cDNA from RNA was prepared using iScript cDNA synthesis kit following the Bio-Rad protocol (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and column purified (QIAquick PCR purification kit; QIAGEN). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg total RNA. Concentrations of cDNA over a 1000-fold range (0.1, 0.01, 0.001, and 0.0001 μg of original cDNA) were amplified by real-time PCR (RT-PCR) using target genes and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)-specific primers as previously described (20). Gene-specific primers for total IR, IR-A and -B isoforms, IRS-1 and -2, PI3K, protein kinase B (AKt), glucose transport proteins 2 and 4 (Glut-2 and -4), glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)-3α and -β isoforms, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR (rictor), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ), ERK1, eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E), glucose-6-phosphatase (G6Pase), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK), and hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) genes for RT-PCR were designed according to sheep sequences using Lasergene Primer select software (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI) and were synthesized commercially (Invitrogen) (Table 1). All cDNA samples were processed in parallel, and cycle threshold (Ct) values obtained from three replicate runs. RT-PCR (50 μl) were run in deoxyribonuclease- and ribonuclease-free 96-well plates with IQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). The amplification conditions were: cycle 1, 95 C for 3 min; cycle 2 (35 times), step 1 denaturation at 95 C for 30 sec, step 2 annealing at 60.4 C for IR (A or B isoform), at 64 C for IRS-1and -2, at 64.9 C for ERK 1, at 61.4 C for AKt, at 61 C for GAPDH, PEPCK, mTOR, and HSL, at 50.7 C for PI3K, at 59 C for Glut-2 and Glut-4, at 56 C for PPARγ and rictor, at 55 C for eIF4E, at 54 C for GSK-3β, and at 52.4 C for GSK-3α and G6Pase for 30 sec, step 3 elongation at 72 C for 30 sec; cycle 3, final elongation at 72 C for 5 min; and cycle 4, hold at 4 C. PCR product specificity was evaluated by analysis of melt curves and agarose gel electrophoresis. In addition, expression levels of IR-A and -B isoforms were analyzed on 3% agarose gel and visualized with ethidium bromide staining. The ratio of IR-A/IR-B was quantified by scanning densitometry with Adobe Photoshop and Kodak Image software.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used for RT-PCR

| Gene | GenBank accession no. | Primers (5′–3′) | Location (bp) | Amplicon (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR | XM_590552.4 | 275 | ||

| Forward | GACGCAGGCCGGAGATGACCA | 2131-2111 | ||

| Reverse | GCTCCTGCCCGAAGACCGACTC | 1856-1877 | ||

| IR-A/B isoform | 326/290 | |||

| Forward | Y16093.1 | CCTCGGGGGAATCTTGGTTGC | 24-44 | |

| Reverse | Y16092.1 | GTGCTGGCGAATGCTGCTCCTG | 350-330 | |

| IRS-1 | XM_581382.3 | 293 | ||

| Forward | TGGCACTGGGCGTAGAGGAGAAGG | 3313-3290 | ||

| Reverse | CGCCCATCAGCTACGCCGACAT | 3020-3041 | ||

| IRS-2 | NM_003749.2 | 268 | ||

| Forward | CCCGAGAAGGTGGCCCGCATCA | 2334-2313 | ||

| Reverse | AGCAACACGCCCGAGTCCATC | 2066-2086 | ||

| PI3K | M_93252.1 | 391 | ||

| Forward | TATATGGCGTAGCTGTGGAGA | 952-932 | ||

| Reverse | AGGGCAAATAATAGTGGTGAT | 561-581 | ||

| Glut-2 | NM_001103222.1 | 268 | ||

| Forward | CATCCATCTTCCTCTTTGTCTG | 1246-1261 | ||

| Reverse | GATTTTCCTTTGGTTTCTGG | 1509-1490 | ||

| Glut-4 | NM_174604.1 | 324 | ||

| Forward | GCTTGGCTTCTTCATCTTCACCTT | 1564-1587 | ||

| Reverse | TGCTCAGACCACCCTTCCCTCCAG | 1888-1865 | ||

| AKt | NM_173986.2 | 168 | ||

| Forward | GACCACGCCCAGCCCCCACCAGT | 1095-1073 | ||

| Reverse | GGACAAGGACGGCCACATCAAGA | 972-949 | ||

| mTOR | XM_001788228.1 | 387 | ||

| Forward | ATCACCCTTGCTCTCCGAACTCTC | 1744-1767 | ||

| Reverse | CCAGCTCCCGGATCTCAAACACCT | 2131-2108 | ||

| PPARγ | BC116098.1 | 275 | ||

| Forward | GTGCAACTGGAAGAAGGAAGAT | 1615-1594 | ||

| Reverse | GTGAAGCCCATTGAGGACATAC | 1340-1361 | ||

| GAPDH | XM_001252511.1 | 416 | ||

| Forward | GGTGGCGCCAAGAGGGTCATCATC | 448-471 | ||

| Reverse | AGGTTTCTCCAGGCGGCAGGTCAG | 864-841 | ||

| GSK-3α | NM_001102192.1 | 250 | ||

| Forward | TGGCTTACACAGACATCAAA | 1050-1069 | ||

| Reverse | TCGGGCACATATTCCAGCAC | 1299-1280 | ||

| GSK-3β | NM_001101310.1 | 249 | ||

| Forward | AGACAAAGATGGCAGCAAGGTGAC | 520-543 | ||

| Reverse | ACGCAATCGGACTATGTTAC | 769-750 | ||

| ERK1 | NM_001110018.1 | 337 | ||

| Forward | TGGCCCCAAAGCAAATTCCC | 1333-1352 | ||

| Reverse | GCCCCCACCTCCACTTCTGTTCA | 1670-1648 | ||

| HSL | NM_001128154.1 | 308 | ||

| Forward | GGAGCACTACAAACGCAACGAGAC | 648-671 | ||

| Reverse | GTGTGGGCCAGCGGGGGTGAGAT | 956-934 | ||

| G6Pase | NM_001076124 | 350 | ||

| Forward | TCTGTAGTGGTGCTTTCGTATGTT | 2240-2263 | ||

| Reverse | TGCAAAGATGTTATGACCAGG | 2589-2566 | ||

| PEPCK | BC112664.1 | 308 | ||

| Forward | AGCTGACAGACTCGCCCTACG | 617-637 | ||

| Reverse | CCAGCCACCCCTCCTCCTTATG | 925-907 | ||

| eIF4E | AF257235.1 | 348 | ||

| Forward | TTTGTTTTGCTTAGTTTTTCTTTC | 1233-1256 | ||

| Reverse | AATGGGACCGCTTTTCTACTTGAG | 1581-1558 | ||

| Rictor | NM_001144096 | 284 | ||

| Forward | CACAGAGAAAACACAAGCCGAGAG | 3604-3627 | ||

| Reverse | AGGGACACTGAGTTTGATTTAGAG | 3884-3861 |

Genes specific for RT-PCR were designed by aligning against sheep sequences (https://isgcdata.agresearch.co.nz/).

Statistical analysis

A comparative Ct was used to determine the expression level of mRNA. Each target gene Ct value for control and prenatal T-treated female was normalized using the formula ΔCt (Ct for target gene − Ct for GAPDH gene). Data were analyzed following the 2−ΔΔCt method (21). This method allows the exponential Ct values to be converted into linear values of fold change in mRNA amounts. It also allows accounting for subtle variations in the amount of RNA used in the first-strand synthesis and the amount of cDNA used for PCR. Relative expression levels were determined using the formula ΔΔCt = ΔCtT-treated − ΔCtcontrol, and the relative target gene mRNA level was calculated using the expression 2−ΔΔCt. Results are presented as mean 2−ΔΔCt ± sem. For each gene, the difference between control and prenatal T-treated females was determined using Student’s t test. A P value <0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Body weight at the time of tissue harvest (control, 63.7 ± 3.4 kg; prenatal T-treated, 69.6 ± 4.5 kg) and liver weights (control, 0.68 ± 0.04 kg; prenatal T-treated, 0.75 ± 0.07 kg) did not differ between the two groups. Results of iv glucose tolerance tests from the larger cohort of control and prenatal T-treated females (of which these were a subset) have been published (22) and showed that prenatal T excess leads to insulin resistance. Blood glucose levels for the subset of control and for prenatal T-treated females used in this study averaged 50.4 ± 0.8 and 56.2 ± 2.8 mg/dl, respectively. Basal insulin concentrations (micro-units per liter) tended to be higher in this subset of prenatal T-treated (18.31 ± 7.29) compared with the control (7.11 ± 0.95) animals.

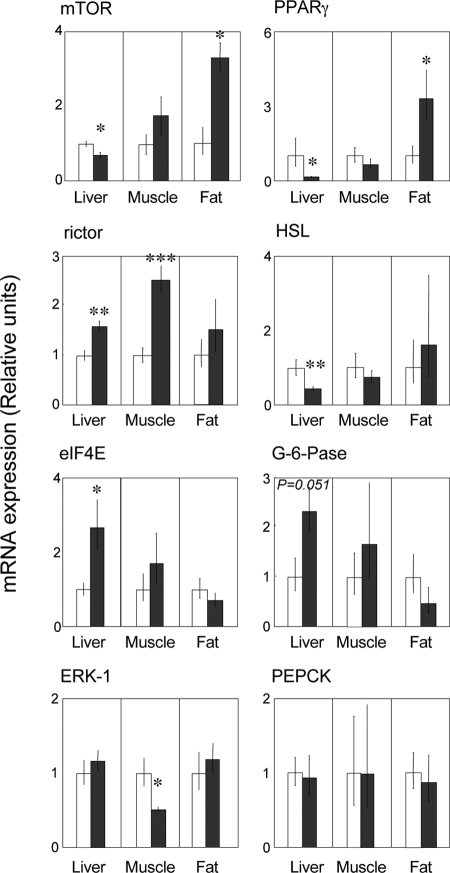

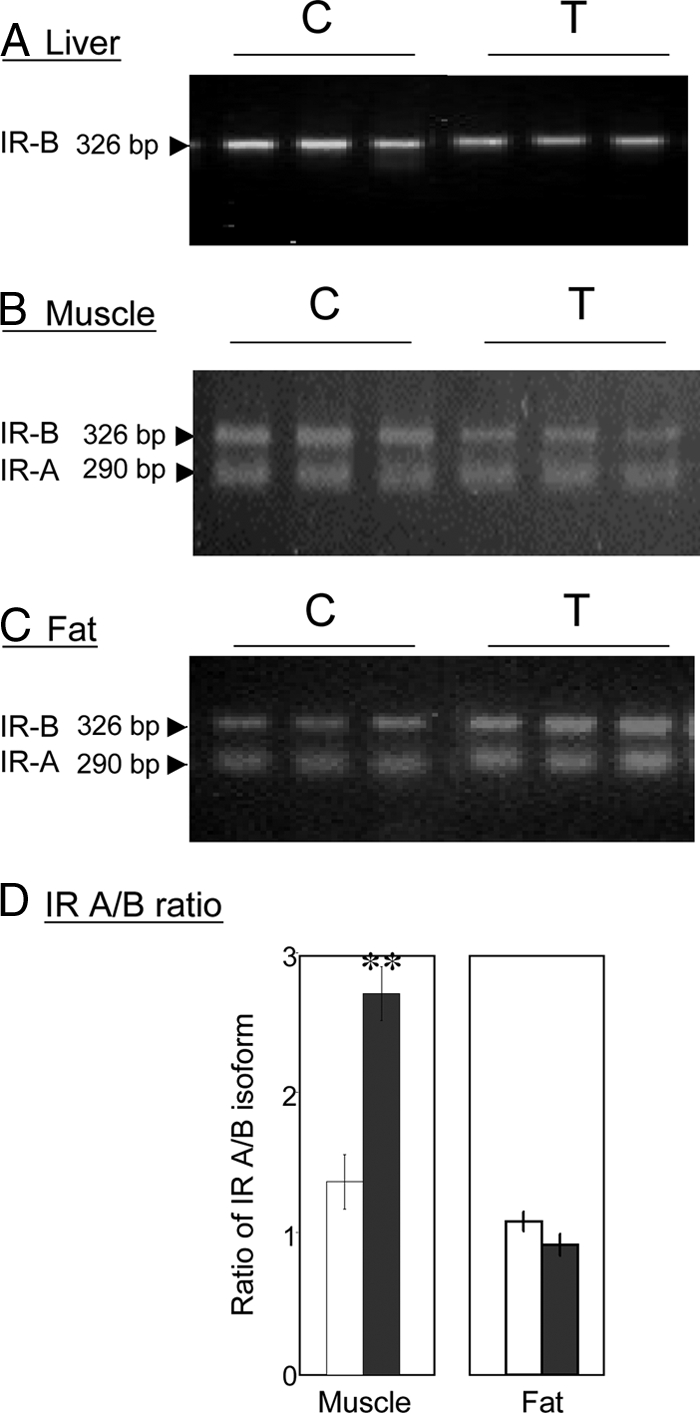

Changes in insulin signaling cascade in the liver

Total IR mRNA expression in the liver was significantly down-regulated in prenatal T-treated sheep in comparison with the control (P = 0.036) (Fig. 1). Only IR-B isoform was detected in the liver (Fig. 2). Although IRS-1 gene expression was similar between control and prenatal T-treated sheep, IRS-2 mRNA expression was significantly reduced in prenatal T-treated sheep compared with controls (P = 0.018) (Fig. 1). Also, the expression levels of AKt (P = 0.039), mTOR (P = 0.028), PPARγ (P = 0.008), and HSL (P = 0.008) mRNAs were reduced in prenatal T-treated sheep compared with controls (Figs. 1 and 3). Expression levels of PI3K and Glut-2 as well as Glut-4, GSK-3β, and PEPCK mRNAs did not differ between treatment groups (Figs. 1 and 3). In contrast, rictor (P = 0.004) and eIF4E (P = 0.009) mRNA expression levels were significantly increased in prenatal T-treated sheep compared with controls (Fig. 3). A tendency for increased expression of G6Pase (P = 0.051) was also evident in prenatal T-treated sheep (Fig. 3).

Figure 1.

Mean ± sem of IR, IRS-1 and -2, PI3K, AKt, Glut-2 and -4, and GSK-3α and -3β mRNA expression in the liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue. Asterisks indicate significant treatment differences. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. C, Control (n = 7); T, prenatal T-treated (n = 6).

Figure 2.

RT-PCR analysis for detection and determination of the relative abundance of IR-A and IR-B isoforms in the liver (panel A), muscle (panel B), and fat tissue (panel C). The amplified products of RT-PCR were analyzed on 3% agarose gel and visualized under UV light. The ratio of IR-A to IR-B was determined by scanning densitometry (panel D). C, Control (n = 7); T, prenatal T-treated (n = 6). All samples were run in triplicate.

Figure 3.

Mean ± sem of mTOR, rictor, eIF4E, ERK1, PPARγ, HSL, G6Pase, and PEPCK mRNA expression in the liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue. Asterisks indicate significant treatment differences. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. C, Control (n = 7); T, prenatal T-treated (n = 6).

Changes in insulin signaling cascade in the skeletal muscle

Prenatal T treatment did not alter total IR but significantly increased (P = 0.001) the ratio of IR-A/IR-B gene expression (Figs. 1 and 2). Prenatal T treatment significantly increased the mRNA expression levels of IRS-1 (P = 0.023), GSK-3α (P = 0.044), GSK-3β (P = 0.002), and rictor (P < 0.001) (Figs. 1 and 3). In contrast, ERK 1 mRNA level was lower (P = 0.01) in prenatal T-treated sheep compared with controls (Fig. 3). No changes in mRNA expression of AKt, Glut-4, eIF4E, PPARγ, HSL, G6Pase, and PEPCK were found between control and prenatal T-treated sheep (Figs. 1 and 3).

Changes in insulin signaling cascade in the adipose tissue

The expression levels of total IR, ratio of IR-A/IR-B isoforms, IRS-1, Glut-4, GSK-3α, GSK-3β, eIF4E, ERK 1, HSL, G6Pase, and PEPCK mRNAs did not differ significantly between prenatal T-treated and control animals (Figs. 1–3). On the other hand, prenatal T treatment increased the gene expression levels of IRS-2 (P = 0.03), PI3K (P = 0.027), mTOR (P = 0.027), AKt (P = 0.005), and PPARγ (P = 0.035) (Figs. 1 and 3).

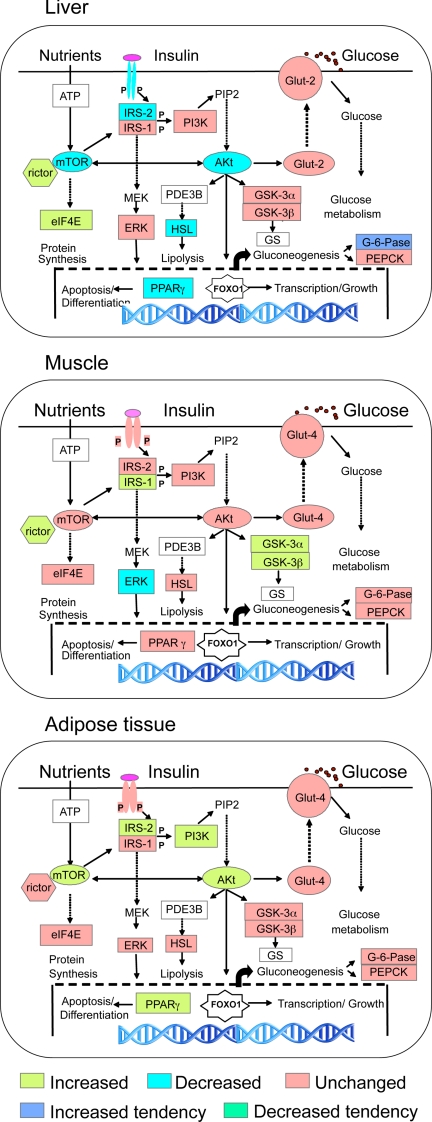

Comparative tissue-specific changes in expression

Comparative tissue-specific changes are shown in Fig. 4, which summarizes the direction of changes in mRNA expression of various members of insulin signaling pathway in the different tissues used in this study. In the liver, prenatal T excess decreased the mRNA expression of many members of the insulin signaling cascade (IR, IRS-2, AKt, mTOR, PPARγ, and HSL). In the muscle, except for decreased ERK1 expression, prenatal T excess had an opposite effect in that the gene expression levels of many members of insulin signaling pathway (IRS-1, GSK-3α and -β, and rictor) were increased. Prenatal T excess also increased expression levels of IRS-2, PI3K, AKt, PPARγ, and rictor genes in the adipose tissue.

Figure 4.

Composite changes in gene expression of members of the insulin signaling pathway in the liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue in response to prenatal T excess: IR, IRS-1 and -2, PI3K, AKt, Glut-2 and -4, GSK-3α and -3β), mTOR, rictor, eIF4E, ERK1, PPARγ, HSL, G6Pase), and PEPCK.

Discussion

The findings from this study provide evidence that prenatal T treatment leads to differential and target-specific changes in the expression of several genes encoding proteins responsible for glucose homeostasis and actions of insulin in the peripheral tissues: liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue. For the most part, the findings in prenatal T-treated females at 21 months of age are consistent with the liver and skeletal muscle being insulin resistant and adipose tissue not. The target-specific findings as they relate to phenotypic expression of peripheral insulin sensitivity in the prenatal T-treated sheep as well as the translational significance of these findings to women with PCOS, the reproductive and metabolic characteristics of whom the prenatal T-treated sheep recapitulate (15,16,17), are discussed below.

Changes in insulin signaling pathway members in the liver

Considering that the liver is a major metabolic regulatory organ (23,24), a defect in IR or any of the members of insulin signaling pathway will cause the liver to become insulin resistant and lead to downstream consequences. The finding that prenatal T treatment down-regulated mRNA expression of IR-B, a predominant isoform in the liver (25) and several members of insulin signaling cascade (IRS-2, AKt, HSL, PPARγ, and mTOR) is consistent with this premise. The involvement of several of these regulators in mediating insulin resistance is supported by findings of similar phenotype in liver-specific IR knockout mice (26), mice with genetic deficiency of IRS-2 (27,28), and HSL knockout mice (29). Because AKt mediates several cellular functions including glucose transport, glycogenesis, DNA synthesis, antiapoptotic activity, and cell proliferation (30,31,32), the reduction in AKt levels in prenatal T-treated females may have an impact on liver function at several levels. Similarly, because mTOR plays a central role in integrating signals from growth factors, hormones, nutrients, and cellular energy levels for regulation of protein translation, cell growth, proliferation, and survival (33,34,35), reduced mTOR levels would likely lead to reduced cellular responses to insulin.

The tendency of increased mRNA expression level of G6Pase, an enzyme that catalyzes the final step of gluconeogenesis leading to production of glucose from glucose-6-phosphate (36), seen in the prenatal T-treated sheep also parallels the increase seen in the liver of Zucker diabetic fatty rats (37). Because PPARγ up-regulates the transcription of HSL (38), the reduced expression of PPARγ and HSL mRNAs in the prenatal T-treated females would likely increase fat content and decrease insulin sensitivity in the liver. These outcomes are similar to the decrease in PPARγ gene and protein expression found in the livers of Zucker diabetic fatty rats (37). Considering that rictor binds mTOR to form an active complex (39), its increased expression in prenatal T-treated females may not lead to functional consequences in the face of reduced mTOR expression. The increase in mRNA expression of eIF4E in prenatal T-treated females may represent a compensatory mechanism to overcome possible decreases in protein levels. To what extent these liver-specific findings relate to women with PCOS is unclear because such studies have not been performed in these women. The effect of prenatal T excess was, however, not seen at the level of Glut-2 expression, the liver-specific glucose transporter (40). Our finding that the insulin-responsive Glut-4 is expressed in the sheep liver is consistent with findings in cattle (41), pigs (42), and baboons (43) and suggestive of a role for this transporter in the liver.

Changes in insulin signaling pathway members in the skeletal muscle

Skeletal muscle plays a significant role in glucose homeostasis mainly through the synthesis of glycogen. Therefore, defects in muscle glycogen synthesis have been proposed to be a leading cause for insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes (44). Our findings show that the ratio of IR-A/IR-B mRNA expression and expression patterns of IRS-1, rictor, GSK-3α, and GSK-3β mRNAs were all increased in the muscle of prenatal T-treated female sheep. The predominance of IR-A isoform over that of IR-B isoform may contribute to insulin resistance in the muscle similar to the unusual form of insulin resistance seen in patients with myotonic dystrophy type 1(45). In support of this premise, other studies have shown that IR-A isoform internalizes at a higher rate and is less efficient in transmitting insulin signals than isoform B (46,47,48). In addition, the increase in mRNA expression of GSK-3β seen in prenatal T-treated females may be a contributory factor in inducing the muscle to become insulin resistant. Increased GSK-3β gene expression has been found to be associated with glucose intolerance, hyperinsulinemia, reduced glycogen content, and impaired glycogen synthase activity in the skeletal muscle of type 2 diabetes subjects (49) and mice overexpressing GSK-3β (50). Studies in rats also found no differences in the expression lervels of IR, IRS-1, and AKt proteins in response to prenatal T excess (51). Overall, the increased expression levels of IR-A isoform and GSK-3β are supportive of skeletal muscle of T-treated female sheep being insulin resistant.

The majority of studies in skeletal muscle of women with PCOS were conducted at a functional level after stimulation with insulin. These studies found that skeletal muscle of women with PCOS have an intrinsic defect in the insulin signaling pathway (4). Assuming changes in mRNA expression would be reflected at the protein level of prenatal T-treated sheep, the increased expression of the IRS-1 gene in skeletal muscle of prenatal T-treated sheep parallel increases in IRS-1 protein seen in the skeletal muscle of women with PCOS (4,52). Similarly, increases in GSK-3β mRNA in prenatal T-treated sheep parallel increased GSK-3 activity in PCOS women (53). Lack of effect of prenatal T treatment on the expression of AKt and Glut-4 mRNAs also parallel a lack of changes in these proteins in the skeletal muscle of women with PCOS (4,54). Although ERK1 mRNA expression was decreased in the prenatal T-treated female sheep, ERK1 protein in the skeletal muscle of women with PCOS (13) showed no such changes.

Changes in insulin signaling pathway members in the adipose tissue

Adipose tissue has a vital role in energy homeostasis, contributes to systemic glucose and lipid metabolism, and also functions as an endocrine organ (55,56). Excessive formation of fat in the adipose tissue would lead to excess free fatty acids being released into the circulation and accumulation in extra-adipose tissue depots such as muscle and liver, thus contributing to development of dyslipidemia and insulin resistance (57). The increases in the expression of IRS-2, PI3K, mTOR, Akt, and PPAR-γ genes observed in this study in prenatal T-treated females are consistent with increased insulin sensitivity of adipose tissue. A change in mTOR expression is also consistent with its role as a regulator of adipogenesis (58,59). Because PPARγ plays a key role in adipogenesis and influences insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis (60,61) and activation of PPARγ in both humans and mice is associated with an enhanced ability of sc fat to take up and store fatty acids (57,59,60,61), the increase in PPARγ seen in adipose tissue of prenatal T females would likely result in increased fat deposition. The impact of prenatal T excess on visceral adiposity remains to be investigated in sheep.

At the adipocyte level, increases in mRNA expression of the PI3K gene seen in prenatal T-treated sheep parallel increases in PI3K protein expression in obese PCOS subjects (62). Similarly, the lack of change in mRNA expression of IR (this study) is consistent with the lack of change in IR protein expression in adipose tissue of women with PCOS (6,63). Although prenatal T excess had no effect on mRNA expression of HSL in sheep, the protein level of HSL was decreased in the adipose tissue of women with PCOS (64).

The differences in direction of the changes in gene expression of insulin signaling members in the liver, skeletal muscle, and adipose tissue of prenatal T-treated sheep and what is seen at the protein level in women with PCOS may reflect species differences, time of procurement of tissue samples relative to developmental milestones, mixed etiology of women with PCOS, and differences between the phenocopy and the likely genetic contribution to the disorder in PCOS women.

Specificity of responses of insulin target tissues to prenatal T excess

Figure 4 summarizes the target-specific changes in the expression of mRNAs of several key members of the insulin-signaling pathway induced by prenatal T excess. In the liver, the decreased expression of mRNAs of several members of the insulin signaling pathway (Fig. 4A) is suggestive of the liver being insulin resistant and less capable of using and storing glucose normally in prenatal T-treated females. Prenatal T-treated females followed a different trajectory in the skeletal muscle with increased expression levels of mRNAs encoding GSK-3α and -β and decreased expression of ERK1 (Fig. 4B) supportive of glucose homeostasis in muscle being regulated differently from that of the liver. The increased mRNA expression of several members of the insulin signaling pathway involved in lipogenesis, adipocyte differentiation, and morphogenesis at the adipose tissue level is supportive of increased insulin sensitivity (Fig. 4C).

To place these findings in functional context, findings from these gene expression studies should be followed up with documentation of changes in phosphorylated proteins. Lack of availability of sensitive species-specific antibodies that detect phosphorylated forms of the insulin signaling members in sheep restricts such investigation at the present time. Irrespective of this limitation, documentation of tissue-specific but coordinated changes induced by prenatal T excess in gene expression of several members of the insulin signaling pathway in itself is an important contribution considering that the direction of these changes are biologically meaningful relative to the phenotype.

In summary, the findings of this study show that prenatal T excess induces tissue-specific changes in the expression of mRNA of several key members of the insulin signaling pathway that are consistent with liver and muscle being insulin resistant and adipose tissue to be more insulin sensitive. The vast majority of these changes appear to parallel changes in protein expression seen in diabetic animals and women with PCOS and hence likely to be of translational relevance.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mr. Douglas D. Doop for producing as well as providing quality care and maintenance of the sheep used in this study; Drs. Mohan Manikkam, Hirenrda Sarma, and Teresa Steckler, Mr. James Lee, and Ms. Carol Herkimer for assistance with prenatal testosterone treatment and tissue harvest; and Dr. Wen Ye, Research Assistant Professor in Biostatistics, School of Public Health for performing the statistical analyses.

Footnotes

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service Grant P01 HD 44234 (to V.P.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online September 15, 2010

Abbreviations: Ct, Cycle threshold; eIF4e, eukaryotic initiation factor 4E; G6Pase, glucose-6-phosphatase; GSK, glycogen synthase kinase; HSL, hormone-sensitive lipase; IR, insulin receptor; IRS, IR substrate; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; PEPCK, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ; RT-PCR, real-time PCR; T, testosterone.

References

- Franks S 1995 Polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med 333:853–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azziz R, Woods KS, Reyna R, Key TJ, Knochenhauer ES, Yildiz BO 2004 The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:2745–2749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legro RS, Kunselman AR, Dodson WC, Dunaif A 1999 Prevalence and predictors of risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in polycystic ovary syndrome: a prospective, controlled study in 254 affected women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:165–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbould A, Kim YB, Youngren JF, Pender C, Kahn BB, Lee A, Dunaif A 2005 Insulin resistance in the skeletal muscle of women with PCOS involves intrinsic and acquired defects in insulin signaling. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 288:E1047–E1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Book CB, Dunaif A 1999 Selective insulin resistance in the polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:3110–3116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbould A, Dunaif A 2007 The adipose cell lineage is not intrinsically insulin resistant in polycystic ovary syndrome. Metabolism 56:716–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SI, Kadowaki T, Kadowaki H, Accili D, Cama A, McKeon C 1990 Mutations in insulin receptor gene in insulin-resistant patients. Diabetes Care 13:257–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Wieland D, Taub R, Tewari DS, Kriauciunas KM, Sethu S, Reddy K, Kahn CR 1989 Insulin-receptor gene and its expression in patients with insulin resistance. Diabetes 38:31–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imano E, Kadowaki H, Kadowaki T, Iwama N, Watarai T, Kawamori R, Kamada T, Taylor SI 1991 Two patients with insulin resistance due to decreased levels of insulin-receptor mRNA. Diabetes 40:548–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Fea K, Roth RA 1997 Modulation of insulin receptor substrate-1 tyrosine phosphorylation and function by mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem 272:31400–31406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gual P, Grémeaux T, Gonzalez T, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Tanti JF 2003 MAP kinases and mTOR mediated insulin-induced phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 on serine residues 307, 612 and 632. Diabetologia 46:1532–1542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanti JF, Grémeaux T, van Obberghen E, Le Marchand-Brustel Y 1994 Serine/threonine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate 1 modulates insulin receptor signaling. J Biol Chem 269:605–6057 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbould A, Zhao H, Mirzoeva S, Aird F, Dunaif A 2006 Enhanced mitogenic signaling in skeletal muscle of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Diabetes 55:751–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbott DH, Dumesic DA, Levine JE, Dunaif A, Padmanabhan V 2006 Animal models and fetal programming of PCOS. In: Azziz R, Nestler JE, Dewailly D, eds. Contemporary endocrinology. Androgen excess disorders in women: polycystic ovary syndrome and other disorders. 2nd ed. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 259–272 [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan V, Manikkam, Recabarren S, Foster DL 2006 Prenatal Testosterone Programs Reproductive and Metabolic Dysfunction in the Female. Mol Cell Endocrinology 246:165–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan V, Veiga-Lopez, Abbott DH, Dumesic DA 2007 Developmental programming of ovarian disruption. In: Gonzalez-Bulnes A, ed. Novel concepts in ovarian endocrinology. Kerala, India: Research Signpost; 329–352 [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan V, Sarma HN, Savabieasfahani M, Steckler TL, Veiga-Lopez A 2010 Developmental reprogramming of reproductive and metabolic dysfunction in sheep: native steroids vs. environmental steroid receptor modulators. Int J Androl 33:394–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manikkam M, Crespi EJ, Doop DD, Herkimer C, Lee JS, Yu S, Brown MB, Foster DL, Padmanabhan V 2004 Fetal programming: prenatal testosterone excess leads to fetal growth retardation and postnatal catch-up growth in sheep. Endocrinology 145:790–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiga-Lopez A, Steckler TL, Abbott DH, Welch K, MohanKumar PS, Phillips DJ, Refsal K, Padmanabhan V 25 August 2010 Developmental programming: impact of prenatal testosterone excess on maternal and fetal steroid milieu. Biol Reprod 10.1095/biolreprod.110.086686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manikkam M, Thompson RC, Herkimer C, Welch KB, Flak J, Karsch FJ, Padmanabhan V 2008 Developmental programming: impact of prenatal testosterone excess on pre- and postnatal gonadotropin regulation in sheep. Biol Reprod 78:648–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD 2001 Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan V, Veiga-Lopez A, Abbott DH, Recabarren SE, Herkimer C 2010 Developmental programming: Impact of prenatal testosterone excess and postnatal weight gain on insulin sensitivity index and transfer of traits to offspring of overweight females. Endocrinology 151:595–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherrington AD 1999 Banting Lecture 1997. Control of glucose uptake and release by the liver in vivo. Diabetes 48:1198–1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordlie RC, Foster JD, Lange AJ 1999 Regulation of glucose production by the liver. Annu Rev Nutr 19:379–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrattan PD, Wylie AR, Bjourson AJ 1998 A partial cDNA sequence of the ovine insulin receptor gene: evidence for alternative splicing of an exon 11 region and for tissue-specific regulation of receptor isoform expression in sheep muscle, adipose tissue and liver. J Endocrinol 159:381–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael MD, Kulkarni RN, Postic C, Previs SF, Shulman GI, Magnuson MA, Kahn CR 2000 Loss of insulin signaling in hepatocytes leads to severe insulin resistance and progressive hepatic dysfunction. Mol Cell 6:87–97 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Withers DJ, Gutierrez JS, Towery H, Burks DJ, Ren JM, Previs S, Zhang Y, Bernal D, Pons S, Shulman GI, Bonner-Weir S, White MF 1998 Disruption of IRS-2 causes type 2 diabetes in mice. Nature 391:900–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Previs SF, Withers DJ, Ren JM, White MF, Shulman GI 2000 Contrasting effects of IRS-1 versus IRS-2 gene disruption on carbohydrate and lipid metabolism in vivo. J Biol Chem 275:38990–38994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roduit R, Masiello P, Wang SP, Li H, Mitchell GA, Prentki M 2001 A role for hormone-sensitive lipase in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion: a study in hormone-sensitive lipase-deficient mice. Diabetes 50:197–1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman EL, Cho H, Birnbaum MJ 2002 Role of Akt/protein kinase B in metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab 13:444–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Monks B, Ge Q, Birnbaum MJ 2007 Akt/PKB regulates hepatic metabolism by directly inhibiting PGC-1α transcription coactivator. Nature 447:1012–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Mu J, Kim JK, Thorvaldsen JL, Chu Q, Crenshaw 3rd EB, Kaestner KH, Bartolomei MS, Shulman GI, Birnbaum MJ 2001 Insulin resistance and a diabetes mellitus-like syndrome in mice lacking the protein kinase Akt2 (PKBβ). Science 292:1728–1731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingar DC, Blenis J 2004 Target of rapamycin (TOR): an integrator of nutrient and growth factor signals and coordinator of cell growth and cell cycle progression. Oncogene 23:3151–3171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingar DC, Salama S, Tsou C, Harlow E, Blenis J 2002 Mammalian cell size is controlled by mTOR and its downstream targets S6K1 and 4EBP1/eIF4E. Genes Dev 16:1472–1487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN 2006 TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell 124:471–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthel A, Schmoll D 2003 Novel concepts in insulin regulation of hepatic gluconeogenesis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 285:E685–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh YH, Kim Y, Bang JH, Choi KS, Lee JW, Kim WH, Oh TJ, An S, Jung MH 2005 Analysis of gene expression profiles in insulin-sensitive tissues from pre-diabetic and diabetic Zucker diabetic fatty rats. J Mol Endocrinol 34:299–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng T, Shan S, Li PP, Shen ZF, Lu XP, Cheng J, Ning ZQ 2006 Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma transcriptionally up-regulates hormone-sensitive lipase via the involvement of specificity protein-1. Endocrinology 147:875–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Kim DH, Guertin DA, Latek RR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Sabatini DM 2004 Rictor, a novel binding partner of mTOR, defines a rapamycin-insensitive and raptor-independent pathway that regulates the cytoskeleton. Curr Biol 14:1296–1302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postic C, Leturque A, Printz RL, Maulard P, Loizeau M, Granner DK. Girard J 1994 Development and regulation of glucose transporter and hexokinase expression in rat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 266:E548–E55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimoto H, Matsutani R, Yamamoto S, Takahashi T, Hayashi KG, Miyamoto A, Hamano S, Tetsuka M 2006 Gene expression of glucose transporter (GLUT) 1, 3 and 4 in bovine follicle and corpus luteum. J Endocrinol 188:111–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschenbach JR, Steglich K, Gäbel G, Honscha KU 2009 Expression of mRNA for glucose transport proteins in jejunum, liver, kidney and skeletal muscle of pigs. J Physiol Biochem 65:251–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco CL, Liang H, Joya-Galeana J, DeFronzo RA, McCurnin D, Musi N 2010 The ontogeny of insulin signaling in the preterm baboon model. Endocrinology 151:1990–1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen KF, Shulman GI 2002 Pathogenesis of skeletal muscle insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol 90:11G–18G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savkur RS, Philips AV, Cooper TA 2001 Aberrant regulation of insulin receptor alternative splicing is associated with insulin resistance in myotonic dystrophy. Nat Genet 29:40–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellerer M, Lammers R, Ermel B, Tippmer S, Vogt B, Obermaier-Kusser B, Ullrich A, Häring HU 1992 Distinct alpha-subunit structures of human insulin receptor A and B variants determine differences in tyrosine kinase activities. Biochemistry 31:4588–4596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosaki A, Pillay TS, Xu L, Webster NJ 1995 The B isoform of the insulin receptor signals more efficiently than the A isoform in HepG2 cells. J Biol Chem 270:20816–20823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belfiore A, Frasca F, Pandini G, Sciacca L, Vigneri R 2009 Insulin receptor isoforms and insulin receptor/insulin-like growth factor receptor hybrids in physiology and disease. Endocr Rev 30:586–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikoulina SE, Ciaraldi TP, Mudaliar S, Mohideen P, Carter L, Henry RR 2000 Potential role of glycogen synthase kinase-3 in skeletal muscle insulin resistance of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 49:263–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce NJ, Arch JR, Clapham JC, Coghlan MP, Corcoran SL, Lister CA, Llano A, Moore GB, Murphy GJ, Smith SA, Taylor CM, Yates JW, Morrison AD, Harper AJ, Roxbee-Cox L, Abuin A, Wargent E, Holder JC 2004 Development of glucose intolerance in male transgenic mice overexpressing human glycogen synthase kinase-3 on a muscle-specific promoter. Metabolism 53:1322–1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demissie M, Lazic M, Foecking EM, Aird F, Dunaif A, Levine JE 2008 Transient prenatal androgen exposure produces metabolic syndrome in adult female rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295:E262–E268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunaif A, Wu X, Lee A, Diamanti-Kandarakis E 2001 Defects in insulin receptor signaling in vivo in the polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 281:E392–E399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glintborg D, Højlund K, Andersen NR, Hansen BF, Beck-Nielsen H, Wojtaszewski JF 2008 Impaired insulin activation and dephosphorylation of glycogen synthase in skeletal muscle of women with polycystic ovary syndrome is reversed by pioglitazone treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:3618–3626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Højlund K, Glintborg D, Andersen NR, Birk JB, Treebak JT, Frøsig C, Beck-Nielsen H, Wojtaszewski JF 2008 Impaired insulin-stimulated phosphorylation of Akt and AS160 in skeletal muscle of women with polycystic ovary syndrome is reversed by pioglitazone treatment. Diabetes 57:357–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu YH, Ginsberg HN 2005 Adipocyte signaling and lipid homeostasis: sequelae of insulin-resistant adipose tissue. Circ Res 96:1042–1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw EE, Flier JS 2004 Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:2548–2556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bays H, Mandarino L, DeFronzo RA 2004 Role of the adipocyte, free fatty acids, and ectopic fat in pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus: peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor agonists provide a rational therapeutic approach. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:463–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM 2005 Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the Rictor-mTOR complex. Science 307:1098–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HJ, Park J, Lee HW, Lee YS, Kim JB 2004 Regulation of adipocyte differentiation and insulin action with rapamycin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 321:942–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argmann CA, Cock TA, Auwerx J 2005 Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ: the more the merrier? Eur J Clin Invest 35:82–92; discussion 80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard F, Auwerx J 2002 PPARγ and glucose homeostasis. Annu Rev Nutr 22:167–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortón M, Botella-Carretero JI, Benguría A, Villuendas G, Zaballos A, San Millán JL, Escobar-Morreale HF, Peral B 2007 Differential gene expression profile in omental adipose tissue in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:328–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seow KM, Juan CC, Hsu YP, Hwang JL, Huang LW, Ho LT 2007 Amelioration of insulin resistance in women with PCOS via reduced insulin receptor substrate-1 Ser312 phosphorylation following laparoscopic ovarian electrocautery. Hum Reprod 22:1003–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seow KM, Tsai YL, Hwang JL, Hsu WY, Ho LT, Juan CC 2009 Omental adipose tissue overexpression of fatty acid transporter CD36 and decreased expression of hormone-sensitive lipase in insulin-resistant women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod 24:1982–1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]