Abstract

Objectives

To inform efforts aimed at reducing Medicare hospice expenditures by describing the longitudinal use of hospice care in nursing homes (NHs) and examining how hospice provider growth is associated with use.

Design

Longitudinal study using NH resident assessment (MDS) and Medicare denominator and claims data for years 1999 through 2006.

Setting

Nursing homes in the 50 U.S. states and District of Columbia

Participants

Persons dying in U.S. NHs

Measurements

We identified Medicare beneficiaries dying in NHs, receipt of NH hospice, and lengths of hospice stay. We also identified the number of hospices providing care in NHs and used a panel data fixed-effect (within) regression analysis to examine how growth in providers affected hospice use.

Results

Between 1999 and 2006 the number of hospices providing care in NHs rose from 1,850 to 2,768 and rates of NH hospice use more than doubled (14% to 33% respectively). With this growth came a doubling of mean lengths of stay (from 46 to 93 days) and a 10% increase in the proportion of NH hospice decedents with noncancer diagnoses (69%% in 1999 to 83% in 2006). Controlling for time trends, for every ten new hospice providers within a state there was an average state increase of 0.58% (95% confidence interval: 0.383, 0.782) in NH hospice use. Much state variation in NH hospice use and growth was observed.

Conclusion

Policy efforts to curb Medicare hospice expenditures (driven in part by provider growth) must consider the potentially negative impact of changes on access for dying (mostly noncancer) NH residents.

Keywords: hospice, nursing homes, end of life, Medicare, reimbursement policy

Introduction

A half million older adults die in U.S. nursing homes (NHs) each year.1 However, while NHs are increasingly sites of end-of-life care,1 there are concerns about the quality of that care. Pain assessment and management are often inadequate,2-8 and family members of dying residents report stress due to limited physician visits and insufficient staffing.9 The use of Medicare hospice care to augment end-of-life care in NHs is a viable option for addressing such concerns and there is a long history of NH-hospice collaborations;10 in fact, in 2004 78% of U.S. NHs contracted with hospice providers.11 Documented benefits of NH hospice care provided to NH residents include better pain management,12 fewer hospitalizations,13 greater family satisfaction with end-of-life care,14-16 and lower costs (at least in the last month of life).17, 18 However, the increasingly long lengths of hospice stay and their higher prevalence in NHs19 has resulted in closer scrutiny of NH hospice care20 and prompted consideration of policies that might jeopardize access. Also, some have advocated for NH hospice's dissolution with an argument in part based on the premise of underuse.21, 22

Concerns regarding increased Medicare hospice expenditures prevail and expenditure increases are believed in part to have been driven by the large growth in new Medicare-certified hospice providers.19, 23 Between 2000 and 2007 there was a five percent average annual growth of Medicare hospice providers and this growth was almost entirely attributable to growth among proprietary providers. This growth has been accompanied by a ten percent average annual growth in Medicare hospice beneficiaries and large increases in lengths of hospice stay.19, 23 Consequently, Medicare hospice expenditures have escalated with long lengths of hospice stays contributing substantially to this increase. Longer stays are believed to be driven in part by financially motivated provider behavior since, regardless of length of stay, hospices are paid the same daily rates for routine hospice home care (95% of all hospice care days) and a hospice's profit margin is greater when its stays are longer.19 Therefore, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) has speculated that some hospices selectively admit patients with higher probabilities of long stays, and these persons are more often persons with noncancer diagnoses.19 Given the high prevalence of noncancer diagnoses in NHs, the concern is that policy efforts to decrease long hospice stays may differentially affect access in NHs, even though hospice has been found to be beneficial and potentially cost-saving.2, 4, 9, 12-18

Both excessively short and long NH hospice stays are problematic (from a expenditure perspective); very short stays lose opportunities for Medicare savings by reducing end-of-life hospitalizations and very long stays increase overall Medicare costs.18, 19 The challenge in NHs is how to balance the need for hospice access with the timing of referral for NH residents in the last stages of (noncancer) chronic terminal illnesses for which predicted survival is poor, at best.24-26 From a policy perspective, the challenge is how to curb behavior by some providers who may be exploiting a payment system that results in higher profits for longer hospice stays19 without jeopardizing access in the NH setting altogether.

Missing from a recent MedPAC report19 and a related commentary23 on growth of Medicare hospice providers and hospice use is discussion and evidence documenting the longitudinal use of hospice by the half million older adults dying in NHs each year.1 Unknown is how growth in hospice providers and in hospice use and lengths of stay are different for care provided in NHs. The population-based longitudinal study presented here provides this information. Using national data from 1999 through 2006 this study describes growth in the rates of hospice use and in mean lengths of stay and it examines the effect of NH provider growth on rates of hospice use. Furthermore, this study presents data on the proportion of hospice care provided in NHs between 1999 and 2006 and contrasts the differing use of NH hospice across U.S. states.

Methods

Data and Study Population

For years 1999 through 2006 we used NH resident assessment (MDS) data for the 50 U.S. states and District of Columbia, Medicare Part A claims data (i.e., for hospice, hospital, home health, outpatient and skilled nursing facility [SNF] care), and Medicare enrollment data (which includes vital statistics data) to create a patient history for all residents.27 We concatenated MDS and claims records to create a per resident history file to determine where study subjects were located and the care they received in the days and weeks prior to death.

The population of NH residents was first identified by using 1999-2006 MDS data from Medicare/Medicaid certified NHs (97% of US NHs). Then, to determine Medicare eligibility and if and when death occurred, these data were matched to the Medicare denominator files. Across study years residents' MDS/denominator match rate was over 90 percent. For 2006, there was a 93.3% match rate resulting in the identification of 3,090,244 NH residents in 2006. Also, to determine the proportion of Medicare beneficiaries who received hospice in NHs (see below) we retrieved data on the total number of Medicare hospice beneficiaries in a calendar year from Medicare and Medicaid Statistical Reports (2001-2008).28

Nursing Home Decedents and NH Hospice

Nursing home decedents were defined as Medicare beneficiaries whose deaths occurred within one day of an identified NH stay or within seven days of hospice transfer from a NH (as done in previous research).13, 29 In study year 1999, to enable capture of at least 180 days of a hospice stay, we only included NH residents who died in July through December. Nursing home hospice use was identified when dates on hospice claims overlapped with dates of NH stays, and decedents classified as receiving NH hospice did not necessarily die with hospice. For instance, in 2006 nine percent of NH decedents receiving hospice were discharged from hospice prior to death. The rates of NH hospice use (for the U.S. and individual states and DC) were determined by dividing the number of NH decedents in a calendar year receiving NH hospice care by the total number of NH decedents in that calendar year.

Decedent Characteristics

Data from the MDS prior to death were used to determine a resident's gender, race/ethnicity and age. Race was categorized as White (non-Hispanic) and Minority (including Hispanic). Age was categorized as less than 65, 65 to 84 and 85+. The principal diagnoses on hospice claims were used to determine hospice residents' diagnoses, and diagnoses were categorized as being noncancer or cancer (primary and secondary cancer codes as well as codes for lymphatic and hematopoietic neoplasms [from International Classifications of Diseases 9th Edition, Clinical Modification]). To determine the proportion of cancer and noncancer NH decedents accessing hospice we used the documentation of a cancer diagnosis on the MDS as evidence of a cancer diagnosis since the denominator included both residents with and without hospice claims.

Days of Hospice Care

For NH decedents receiving NH hospice care, dates on hospice claims were used to identify the hospice length of stay (i.e., total number of days on the Medicare hospice benefit). When more than one hospice episode occurred (i.e., individual was discharged and readmitted to hospice), the days from each episode were totaled. Hospice days prior to NH admission were included in totals when these days were part of a continuous hospice episode or when the episode(s) occurred within six months of the NH hospice episode. For 2006, 12,950 (7.6%) of the 172,015 NH hospice decedents received hospice care prior to NH admission, and of these, 10,763 (83%) had one continuous hospice episode.

Hospices Providing Care in NHs

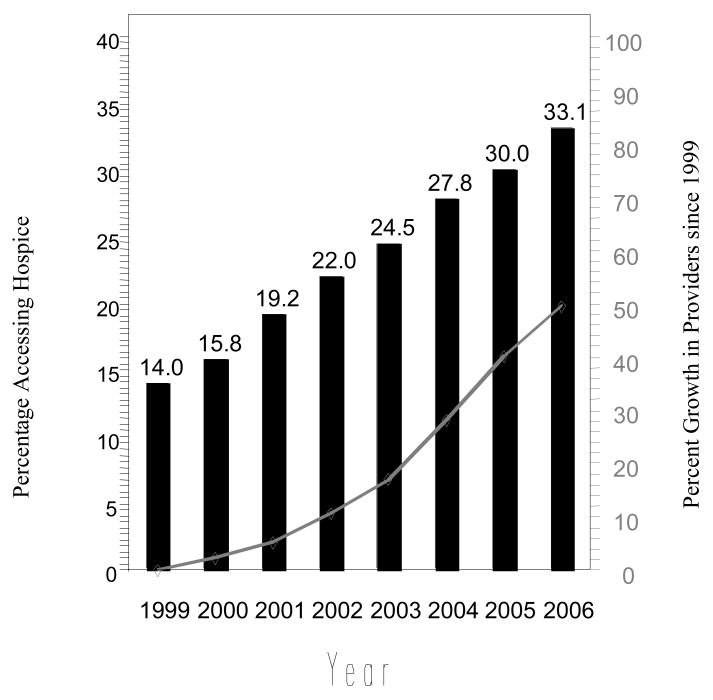

Using the hospice claims for NH residents, we identified the unique number of hospices providing care in NHs in 1999 through 2006. The provider's official address in the hospice provider of service file (or if unavailable, the first two digits of the provider number) were used to assign the hospice to a state. Through previous analysis we had determined the growth of providers in NHs to be different than the growth of all Medicare certified hospice providers. Specifically, using 1999 as the base year, growth in the number of hospices providing care in NHs began in 2000 and continued through 2006 (see Figure 1). However, growth in the number of all Medicare certified hospice providers did not occur until 2003.19

Figure 1. Percentage Growth in Hospices Providing Care in Nursing Homes and Rates of Nursing Home Decedent Hospice Use, 1999-2006.

Bar = Percent of Nursing Home Decedents Accessing Hospice

Line = Percent Growth in Number of Hospice Providers Since 1999

Proportion of Medicare Hospice Care in NHs

This proportion was defined as the percentage of total Medicare hospice beneficiaries in a calendar year who received any hospice while in a NH. The numerator was the total number of NH residents in a calendar year with any NH hospice (not restricted to decedents) and the denominator was the total number of Medicare beneficiaries in a calendar year who received hospice (from the Medicare and Medicaid Statistical Reports).28

Analytic Approach

Descriptive statistics were used to show provider growth, hospice decedent characteristics, and the rate of NH hospice use (weighted by number of deaths in individual states and U.S.) over time and in 2006. T-test and chi square statistics were used to test the statistical significance of observed differences, and a Breslow-Day statistic was used to test for interactions (i.e., for changes between 1999 and 2006 by categories of U.S. states). To examine how the growth in hospice providers affected NH hospice use, we performed a panel data fixed-effect (within) regression analysis that controlled for differences across states (50 U.S. states and District of Columbia). This analysis included a year indicator to capture the secular trend (scaled to be zero in the first year [1999]) and the number of hospices (scaled to be zero in 1999 and representing an increase of ten providers per unit of change). State-level observations were weighted in the regression by their number of confirmed NH decedents to obtain nationally representative estimates.

Results

While the number of Medicare hospice beneficiaries in NHs doubled from 101,843 in 1999 to 233,844 in 2006, the proportion of beneficiaries who were in NHs largely mirrored the overall growth in the Medicare hospice program. In 1999, 21.7 percent of Medicare hospice beneficiaries resided in NHs; this rose to 24.2% in 2002 and remained constant through 2006, at approximately 25 percent (data not shown).

The number of Medicare-certified hospices providing care in US NHs was 1,850 in 1999 and 2,768 in 2006 (a 49.6% growth), and the rate of NH decedent hospice use was 14.0% in 1999 and 33.1% in 2006 (a growth of 137%; Figure 1). Using regression analysis that controlled for state differences and secular time trend, we found that for every ten new hospice providers within a state there was an average state increase of 0.58% in NH hospice use (95% confidence interval: 0.383, 0.782). Between 1999 through 2006 this effect represents, on average, an additional four percent increase in hospice use in the ten states with the largest provider growth, compared to the ten states with the lowest growth. Of note, NH hospice use increased significantly over time irrespective of provider growth. Controlling for hospice provider growth and differences across states, rates of hospice use grew each year by an average of 2.5% (AOR 2.50; 95% CI 2.375, 2.620).

The demographic characteristics of NH hospice decedents changed little across study years. Over time, most hospice decedents were female (about 67%), White (around 90%), and 50 to 55% were 85 years of age or older. However, the proportion of NH hospice decedents with noncancer diagnoses grew from 69.2% in 1999 to 82.6% in 2006 (p <.001) and there was significant growth in the proportion of cancer and noncancer decedents accessing hospice. In 1999, 11.9% of NH decedents with noncancer diagnosis and 23.0% with cancer diagnoses accessed hospice; in 2006, these rates rose to 31.4% and 51.3% respectively (p <.001).

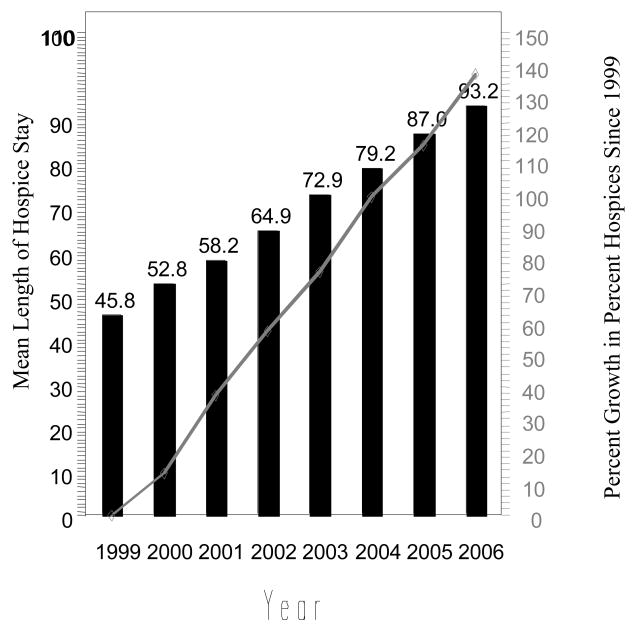

With the growth in NH hospice use came longer mean lengths of hospice stay (Figure 2). Nationwide, mean stays for NH decedents rose from 45.8 days in 1999 to 93.2 days in 2006 (p <.001), and this increase appears to have been driven by higher proportions of long hospice stays. For instance, the proportion of hospice stays over 180 days rose from 6.6% in 1999 to 15.6% in 2006 (p <.001) while the proportion of hospice stays of seven days or less remained relatively stable at around 30%.

Figure 2. Percentage Growth in Rates of Hospice Use and Mean Lengths of Hospice Stay for Nursing Home Decedents, 1999-2006.

Bar = Mean Length of Hospice Stay

Line = Percent Growth in Percent Hospice Since 1999

Table 1 presents the considerable state variation in the growth of NH hospice providers and in NH hospice use between 1999 and 2006. In 2006, the lowest rates of NH hospice use were in Alaska (2.3%) and Hawaii (7.9%), but rates were also low in several rural states such as Wyoming (9.0%) and Vermont (8.1%). Even in these low use states, however, the percent of growth in NH hospice use was high; for example, in Wyoming the increase in the rate of hospice use was 163 percent and in Vermont it was 96 percent. In the ten states with the most provider growth (Alabama, Georgia, Idaho, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Mexico, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee and Utah; see Table 1), there was a (weighted) 192% increase in rates of NH hospice use between 1999 and 2006 compared to a (weighted) 101% increase in the ten states with the least provider growth (Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky, Maryland, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New York, North Dakota, Minnesota, South Dakota and Washington; see Table 1). However, the proportion of Medicare hospice care in NHs differed little in 2006 for these states with the most versus least provider growth (21.6 versus 22.6 respectively).

Table 1. Growth in Nursing Home (NH) Hospice Use (1999-2006) and in NH Hospice Use in 2006 across 50 U.S. States and District of Columbia.

| Nursing Home Decedents in 2006 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent Growth in Hospice Providers | Percent Growth in Rates of Hospice Use by NH Decedents | Percent of Hospice Care Provided in NHs | Percent Hospice Use | Days of Hospice Stay Among Decedents with Hospice | |||

| State | 1999-2006 | 1999-2006 | 2006 | 2006 | Mean Days of Stay | Proportion ≥ 7 Days, % | Proportion ≥ 181 Days, % |

| United States | 49.6 | 137.1 | 25.0 | 33.1 | 93.2 | 30.6 | 15.6 |

| AK* | -- | -- | 2 | 2.3 | 44.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| AL | 137.2 | 161.1 | 16.9 | 34.2 | 152.6 | 20.9 | 27.0 |

| AR | 10.8 | 179.1 | 22.3 | 26.6 | 109.0 | 31.7 | 17.5 |

| AZ | 56.3 | 70.2 | 14.1 | 43.5 | 109.8 | 29.9 | 19.5 |

| CA | 24.2 | 98.7 | 18.4 | 27.7 | 79.4 | 34.7 | 12.4 |

| CO | 32.3 | 47.2 | 28.7 | 45.5 | 86.2 | 33.2 | 15.0 |

| CT | 21.7 | 234.6 | 33.3 | 28.2 | 45.2 | 39.3 | 6.3 |

| DC | 50.0 | 195.8 | 14 | 18.6 | 70.5 | 23.4 | 12.8 |

| DE | 40.0 | 117.0 | 28.8 | 46.8 | 83.9 | 34.3 | 13.4 |

| FL | 7.9 | 98.6 | 21.1 | 41.5 | 126.1 | 27.6 | 21.0 |

| GA | 92.0 | 104.2 | 19.7 | 35.2 | 112.8 | 26.2 | 18.9 |

| HI | 66.7 | 497.2 | 7.3 | 7.9 | 62.2 | 31.7 | 12.5 |

| IA | 18.6 | 195.2 | 46.8 | 50.0 | 71.5 | 33.1 | 11.8 |

| ID | 93.8 | 146.8 | 15.9 | 17.1 | 94.8 | 26.1 | 17.3 |

| IL | 20.5 | 97.0 | 29.6 | 36.6 | 78.4 | 32.3 | 12.6 |

| IN | 53.1 | 217.0 | 32.6 | 33.0 | 103.9 | 28.5 | 17.9 |

| KS | 60.6 | 176.2 | 32.6 | 47.8 | 92.3 | 28.8 | 16.1 |

| KY | 9.5 | 100.2 | 22.7 | 23.6 | 88.9 | 31.1 | 15.0 |

| LA | 206.7 | 315.4 | 27.2 | 41.9 | 99.0 | 25.2 | 16.5 |

| MA | 39.5 | 246.3 | 38.1 | 31.6 | 70.3 | 33.8 | 11.6 |

| MD | 8.0 | 146.5 | 23.4 | 23.3 | 64.6 | 34.6 | 10.3 |

| ME | 45.5 | 786.9 | 30.4 | 23.8 | 81.0 | 30.7 | 14.2 |

| MI | 29.4 | 115.6 | 21.4 | 34.6 | 88.3 | 31.1 | 14.5 |

| MN | 3.6 | 107.4 | 33.9 | 30.0 | 71.5 | 31.2 | 12.1 |

| MO | 40.9 | 154.1 | 39.5 | 42.1 | 98.4 | 27.9 | 17.4 |

| MS | 252.6 | 621.8 | 11.8 | 24.6 | 147.5 | 21.1 | 25.7 |

| MT | 71.4 | 185.4 | 21.6 | 21.3 | 78.4 | 33.0 | 13.7 |

| NC | 33.9 | 281.0 | 19.6 | 26.5 | 96.9 | 27.4 | 16.7 |

| ND | 7.7 | 85.2 | 54.8 | 24.0 | 88.5 | 29.1 | 14.9 |

| NE | 32.0 | 128.3 | 45.4 | 38.1 | 69.8 | 36.0 | 11.5 |

| NH | 0.0 | 227.0 | 32.2 | 33.7 | 63.8 | 34.3 | 10.4 |

| NJ | 42.9 | 208.1 | 29.9 | 34.2 | 70.3 | 34.1 | 11.6 |

| NM | 190.9 | 125.7 | 18.1 | 37.3 | 141.3 | 26.7 | 22.5 |

| NV | 57.1 | 92.3 | 15.9 | 33.6 | 105.7 | 32.1 | 17.1 |

| NY | (2.0) | 106.6 | 20 | 17.1 | 77.6 | 29.3 | 13.2 |

| OH | 16.5 | 97.9 | 35.1 | 39.8 | 87.3 | 34.0 | 14.4 |

| OK | 108.8 | 119.2 | 34.5 | 56.6 | 188.4 | 19.3 | 31.2 |

| OR | 18.9 | 138.1 | 14.3 | 34.4 | 57.4 | 36.8 | 9.6 |

| PA | 34.0 | 163.3 | 31.1 | 33.8 | 81.3 | 32.9 | 13.9 |

| RI | 33.3 | 534.4 | 41.5 | 43.0 | 69.7 | 35.0 | 12.0 |

| SC | 111.5 | 192.1 | 17.4 | 28.7 | 131.3 | 24.3 | 23.4 |

| SD | 9.1 | 294.4 | 43.1 | 24.2 | 60.6 | 32.5 | 8.6 |

| TN | 100.0 | 580.1 | 26.5 | 27.4 | 97.9 | 26.0 | 15.9 |

| TX | 85.7 | 115.6 | 28.1 | 48.1 | 107.5 | 29.1 | 17.4 |

| UT | 253.3 | 309.5 | 24.2 | 47.2 | 125.7 | 31.0 | 21.9 |

| VA | 71.4 | 332.6 | 19.5 | 22.5 | 77.5 | 30.9 | 12.6 |

| VT | 33.3 | 96.4 | 12.5 | 8.1 | 74.2 | 36.4 | 15.0 |

| WA | 3.4 | 49.4 | 18.9 | 25.0 | 66.2 | 30.2 | 11.0 |

| WI | 19.6 | 165.4 | 25.4 | 24.6 | 83.8 | 31.2 | 14.0 |

| WV | 55.6 | 459.1 | 11.1 | 11.4 | 106.2 | 26.5 | 19.0 |

| WY | 77.8 | 163.2 | 14.6 | 9.0 | 87.0 | 33.3 | 15.6 |

Alaska had no NH hospice patients in 1999

Mean lengths of stay also differed in the ten states with the most versus the least provider growth, with mean stays being significantly longer in states with the most versus least growth (131 versus 95 days; p <.001). Additionally, increases in lengths of stay at the 90th percentile were greater in the ten states with the most versus the least provider growth. At the 90th percentile, hospice stays were 173 days in 1999 and 399 days in 2006 (a 131% increase) in states with the most provider growth while they were 141 and 276 days (respectively; a 96% increase) in states with the least growth. However, increases in the proportion of NH hospice decedents with noncancer diagnoses were similar for the ten states with the most versus the least provider growth (13.8% versus 13.0% increase).

Discussion

There was substantial growth in the number of hospices providing care in NHs and this growth was significantly associated with increased rates of hospice use. Furthermore, increased rates of hospice use were accompanied by dramatic increases in mean hospice stays. Herein lays the concern. While increased access to hospice care in NHs had been promoted,30 increased access appears to come at a cost of longer stays and these have resulted in increased Medicare hospice expenditures.19 Furthermore, although increases in hospice use are a likely response to unmet needs,24, 25 greater growth in long stays were observed in the ten states with the most versus the least provider growth even though both groups had similar increases in noncancer patients. Further study is needed to understand the provider and/or healthcare market factors influencing these differences.

In the US, 67% of older persons with dementia-related diagnoses and 28% of persons with other noncancer diagnoses die in NHs, while only 21% of those with cancer diagnoses die in NHs.1 Therefore, to provide hospice care to all but a very small proportion of dying NH residents means substantial care will be provided to persons with noncancer diagnoses, a high proportion of who will have dementia-related diagnoses. We observed this firsthand since the proportion of hospice NH decedents with noncancer diagnoses was sizable (at 69%) even prior to the substantial growth of hospice providers, when only 14% of decedents accessed hospice. However, while 83% of NH decedents had noncancer diagnoses in 2006, only 31% percent accessed hospice. In contrast, 51% of NH decedents with cancer diagnoses accessed hospice in 2006. This large discrepancy in access reflects the continuing barriers to Medicare hospice for persons with (noncancer) chronic terminal illnesses in NH and non-NH settings.24-26

Mean hospice stays for NH decedents more than doubled, from 46 days in 1999 to 93 days in 2006. Additionally, in 2006 the 93 day mean hospice stay for NH decedents is estimated to be at least 20 days longer than the mean stay for non-NH hospice decedents (based on the proportion of all Medicare hospice provided in NHs, the mean NH stay and on MedPAC length of stay data for all hospice decedents).19 This longer mean stay for NH decedents is consistent with NH case-mix differences (as discussed above) and with the more bimodal distribution of hospice lengths of stay for persons with noncancer diagnosis.31 Still, as discussed above, it appears differing provider and/or healthcare market behavior may influence the presence of longer long stays (days of stay at 90th percentile) since increases in these days were significantly greater in the ten states with the greatest versus least provider growth.

Our study provides new information showing almost a third of Medicare beneficiaries dying in NHs accessed Medicare hospice in 2006, and given the observed trends this growth in use is likely continuing. Additionally, other recent research has shown 40% of NH decedents with end-stage dementia and 35% of those with a co-morbid dementia diagnoses accessed hospice in 2006.32 Therefore, calls for elimination of Medicare hospice in NHs based on its underuse appear unfounded,21, 22 especially considering our finding that use in the NH mirrored the overall growth in Medicare hospice use. Additionally, the notion that the complexity of NH-hospice collaborations is a major obstacle to the viability of hospice care in NHs22 also appears unfounded given the high proportion of U.S. NHs contracting with hospice providers and the documented outcomes resulting from this collaborative care.4, 9, 12-16 Nevertheless, the argument that the design of the Medicare hospice benefit creates barriers to its access21, 22 is undeniable.

There are major shortcomings in the Medicare hospice benefit that appear to influence the timing of referral (resulting in very short and long stays),33 and that may limit further increases in access for NH residents. First, the need for a physician-certified six-month terminal prognosis creates substantial barriers for persons with (noncancer) chronic terminal illnesses for whom a six-month prognosis is difficult.24, 25 While this barrier affects persons dying in NHs and in other settings (and 72% of persons with non-dementia chronic terminal illnesses die in non-NH settings),1 the barrier is particularly important in NHs given the high proportion of NH residents with chronic terminal illnesses. Another major barrier arising from the Medicare hospice benefit is the requirement that beneficiaries enrolling in hospice must forgo other Medicare-Part A care (when such care is related to the terminal illness). For beneficiaries in the community or in NHs this means hospital care and curative treatment must be abandoned, but it often also means abandonment of expensive treatments such as blood transfusions or palliative radiation (when hospices lack financial resources to support such care).24-26 Additionally, in NHs the Medicare Part A forfeiture requirement creates a system-wide barrier since dying NH residents routinely receive Medicare Part-A skilled nursing facility (SNF) care (after hospitalizations),34 and its forfeiture is financially disadvantageous for NHs and families.35 Even given these barriers, we did find a third of NH decedents in 2006 enrolled in Medicare hospice. However, as expected, a high proportion of hospice stays were seven days or less (30.6% in 2006) or over 181 days (15.6% in 2006; Table 2).

While most U.S. NHs approach the provision of end-of-life palliative care by referring residents to hospice, many NHs also invest in developing internal palliative care programs/expertise (with or without hospice care).11 The few studies that have tested the integration of (nonhospice) palliative care expertise and processes into NHs have shown improvement in care processes,36-40 and when combined with a quality improvement program, a reduction in pain prevalence.41 However, there has been no widespread dissemination of any of these efforts. In 2004, 27 % of U.S. nursing homes reported having special programs and (specially) trained staff for hospice or palliative/end-of-life care but information on the scope of practices included in these programs was not reported.11 More study is needed to understand the extent and breadth of nonhospice palliative care provision and expertise in U.S. NHs, the resulting quality outcomes, and the feasibility of its widespread implementation. Without a more in-depth understanding of what NH practices and investments result in higher quality palliative care outcomes and whether the few small-scale studies can be replicated across a broad range of NHs, paying NHs more to provide “palliative care” in lieu of paying Medicare-certified hospices21 is ill-advised. At present, given our current understanding of NH end-of-life care and of the benefits and use of hospice care in NHs, 5-8, 14, 16 the provision of NH-hospice collaborative care appears to be the most feasible option for widespread improvement of dying residents' quality of care and life.10 Notwithstanding this, increased palliative care knowledge and (availability to) expertise in NHs and in other healthcare settings continues to be needed to ensure high-quality symptom management to persons who do not qualify for or choose hospice, and payment or quality indicator oversight efforts to incentivize such symptom management are desirable.

The MedPAC has recommended changing the Medicare payment system so the per diem rate for hospice routine home care (95% of all hospice care days) better reflects the intensity of hospice service provision.19 Since research has shown hospice visits to be more frequent at time periods closer to the beginning and end of hospice episodes,42-44 it is reasonable to have higher payment rates around the time of hospice admission and around the time a patient is dying. The MedPAC has also recommended closer scrutiny of recertification of hospice patients after the 180th day of stay, specifically, they propose requiring patient visits by physicians or advanced practice nurses to evaluate their continued eligibility and need for care.19 Together, these recommended approaches to curbing Medicare costs appear to be a viable option for both retaining access while reducing the number of long (costly) hospice stays (some of which appear to result from perverse financial incentives). However, evaluation of such a payment option must include consideration of variations in hospice use in NHs (as shown here) and the probable greater impact of changes on hospice access for dying NH residents, given the high proportion of persons with noncancer diagnoses in NHs.

In conclusion, given the increasingly high proportion of Medicare beneficiaries who die in NHs and their entitlement to and benefit from the Medicare hospice benefit, denying them access to NH hospice is not desirable. Our analyses provide new information on the increased use of hospice care in NHs and show substantial increases in very long hospice stays. As such, our data support the need for a modification in the current Medicare hospice reimbursement systems which would vary payments as a function of length of stay.19 However, it is important for any new policy to explicitly acknowledge the challenges inherent in the timing of hospice referral for NH residents in the last stages of (noncancer) chronic terminal illnesses24-26 by recognizing “early” referrals will occur and deeming them “acceptable” in the presence of well-documented physician evaluations and eligibility determinations. Without such explicit acknowledgement the fear is that undue scrutiny may occur, resulting in decreasing enrollments and a higher prevalence of very short stays.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Mr. Venkatesh Nathilvar, MS who merged the datasets and assembled the study's analytic database.

This study was supported by a grant from the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (R03HS016918) and by the Shaping Long Term Care in American Project funded by the National Institute on Aging (P01AG027296).

This paper was presented at the 2010 Annual Meeting of the American Association of Hospice and Palliative Medicine.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Miller, Gozalo and Mor are funded by the National Hospice Foundation to design and simulate modifications to the Medicare hospice benefit payment system

Author Contributions: Miller contributed to the concept and drafting of the manuscript and Miller and Mor contributed to the acquisition of data. All authors contributed to the design, analysis and interpretation of data, and to the critical review of the manuscript.

Sponsor's Role: None

References

- 1.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Miller SC, Mor V. A national study of the location of death for older persons with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:299–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004;291:88–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen-Mansfield J, Lipson S. Pain in cognitively impaired nursing home residents: How well are physicians diagnosing it? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1039–1044. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller SC, Mor V, Teno J. Hospice enrollment and pain assessment and management in nursing homes. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;26:791–799. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(03)00284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanson LC, Eckert KJ, Dobbs D, et al. Symptom experience of dying long-term care residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:91–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1529–1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernabei R, Gambassi G, Lapane K, et al. Management of pain in elderly patients with cancer. SAGE Study Group. Systematic Assessment of Geriatric Drug Use via Epidemiology. JAMA. 1998;279:1877–1882. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.23.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrell BR, Dean GE, Grant M, Coluzzi P. An institutional commitment to pain management. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2158–2165. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.9.2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shield R, Wetle T, Teno J, et al. Physicians “missing in action”: Family perspectives on physician and staffing problems in end-of-life care in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1651–1657. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller SC. A model for successful nursing home-hospice partnerships. J Palliat Med. 2010 Apr 9; doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0296. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller SC, Han B. End-of-life care in U.S. nursing homes: Nursing homes with special programs and trained staff for hospice or palliative/end-of-life care. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:866–877. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller SC, Mor V, Wu N, et al. Does receipt of hospice care in nursing homes improve the management of pain at the end of life? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:507–515. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gozalo P, Miller S. Hospice enrollment and evaluation of its causal effect on hospitalization of dying nursing home patients. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:587–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00623.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baer WM, Hanson LC. Families' perception of the added value of hospice in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:879–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb06883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munn JC, Dobbs D, Meier A, et al. The end-of-life experience in long-term care: Five themes identified from focus groups with residents, family members, and staff. The Gerontologist. 2008;48:485–494. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.4.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wetle T, Teno J, Shield R, Welch LC, Miller SC. End of Life in Nursing Homes: Experiences and Policy Recommendations. Washington, D.C.: AARP Public Policy Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gozalo P, Miller S, Intrator O, et al. Hospice effect on government expenditures among nursing home residents. Health Serv Res. 2008;43:134–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00746.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller SC, Intrator O, Gozalo P, et al. Government expenditures at the end of life for short- and long-stay nursing home residents: Differences by hospice enrollment status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1284–1292. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. Washington, DC: 2009. Reforming Medicare's Hospice Benefit; pp. 347–376. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Office of Inspector General. Medicare Hospice Care for Beneficiaries in Nursing Facilities: Compliance with Medicare Coverage Requirements. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huskamp HA, Stevenson DG, Chernew ME, et al. A new medicare end-of-life benefit for nursing home residents. Health Affairs. 2010;29:130–135. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meier DE, Lim B, Carlson MD. Raising the standard: palliative care in nursing homes. Health Affairs. 2010;29:136–140. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iglehart JK. A new era of for-profit hospice care--the Medicare benefit. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2701–2703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0902437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright A, Katz I. Letting go of the rope--aggressive treatment, hospice care, and open access. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:324–327. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gazelle G. Understanding hospice--an underutilized option for life's final chapter. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:321–324. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp078067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Welch LC, Miller SC, Martin EW, et al. Referral and timing of referral to hospice care in nursing homes: The significant role of staff members. The Gerontologist. 2008;48:477–484. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Intrator O, Berg K, Hiris V, et al. Development and validation of the Medicare MDS Residential History File. Gerontologist. 2003;43:30–31. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare & Medicaid Statistical Supplement. 2001-2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller S, Mor V, Wu N, et al. Does receipt of hospice care in nursing homes improve the management of pain at the end of life? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:507–515. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zerzan J, Stearns S, Hanson L. Access to palliative care and hospice in nursing homes. JAMA. 2000;284:2489–2494. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller SC, Mor V. The emergence of Medicare hospice care in US nursing homes. PalliatMed. 2001;15:471–480. doi: 10.1191/026921601682553950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller S, Lima J, Mitchell S, et al. Gerontologist. Trends in Hospice use among Nursing Home Decedents with Dementia: 1999 to 2006. Annual Meeting of Gerontological Society of America; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller SC, Weitzen S, Kinzbrunner B. Factors associated with the high prevalence of short hospice stays. JPalliatMed. 2003;6:725–736. doi: 10.1089/109662103322515239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levy CR, Fish R, Kramer AM. Site of death in the hospital versus nursing home of medicare skilled nursing facility residents admitted under Medicare's Part A benefit. J Am Geriatri Soc. 2004;52:1247–1254. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller SC, Teno JM, Mor V. Hospice and palliative care in nursing homes. Clin Geriatr Med. 2004;20:717–734. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanson LC, Reynolds KS, Henderson M, et al. A quality improvement intervention to increase palliative care in nursing homes. J Palliat Med. 2005;8:576–584. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keay TJ, Alexander C, McNally K, et al. Nursing home physician educational intervention improves end-of-life outcomes. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:205–213. doi: 10.1089/109662103764978452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rochon T, Evans B, Dexter C, et al. Initial development and evaluation of a nurse practitioner palliative care consultation service. Poster abstract #75617. Las Vegas, NV. AGS Annual Scientific Meeting; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tuch H, Parrish P, Romer AL. Integrating palliative care into nursing homes. J Palliat Med. 2003;6:297–309. doi: 10.1089/109662103764978623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weissman DE, Griffie J, Muchka S, et al. Improving pain management in long-term care facilities. J Palliat Med. 2001;4:567–573. doi: 10.1089/109662101753381755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baier RR, Gifford DR, Patry G, et al. Ameliorating pain in nursing homes: A collaborative quality-improvement project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1988–1995. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller SC. Hospice care in nursing homes: Is site of care associated with visit volume? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1331–1336. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to Congress: Reforming the Delivery System. Washington, DC: 2008. Evaluating Medicare's Hospice Benefit; pp. 203–240. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gruneir A, Miller S. Hospice care in the nursing home: Changes in visit volume from enrollment to discharge among longer-stay residents. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32:478–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]