ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

There is a focus on integrating quality improvement with medical education and advancement of the American College of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) core competencies.

OBJECTIVE

To determine if audits of patients with unexpected admission to the medical intensive care unit using a self-assessment tool and a focused Morbidity and Mortality (M&M) conference improves patient care.

DESIGN

Charts from patients transferred from the general medical floor (GMF) to the medical intensive care unit (ICU) were reviewed by a multidisciplinary team. Physician and nursing self-assessment tools and a targeted monthly M&M conference were part of the educational component.

PARTICIPANTS

Physicians and nurses participated in root cause analysis.

MEASURES

Records of all patients transferred from a general medical floor (GMF) to the ICU were audited. One hundred ninety-four cases were reviewed over a 10-month period.

RESULTS

New policies regarding vital signs and house staff escalation of care were initiated. The percentage of calls for patients who met medical emergency response team/critical care consult criteria increased from 53% to 73%, nurse notification of a change in a patient’s condition increased from 65% to 100%, nursing documentation of the change in the patients condition and follow-up actions increased from 65% percent to a high of 90%, the number of cardiac arrests on a GMF decreased from 3.1/1,000 discharges to 0.6/1,000 discharges (p = 0.002), and deaths on the Medicine Service decreased from 34/1,000 discharges to 24/1,000 discharges (p = 0.024).

CONCLUSION

We describe an audit-based program that involves nurses, house staff, a self-assessment tool and a focused M&M conference. The program resulted in significant policy changes, more rapid assessment of unstable patients and improved hospital outcomes.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1427-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: house staff, Self-assessment, Audit-based quality improvement program

INTRODUCTION

Several approaches have been taken to involve house staff in quality initiatives including conferences and curriculum regarding quality improvement, attendance at hospital quality improvement committees, participation in quality improvement projects, and quality focused Morbidity and Mortality (M&M) conferences1–6. There is a continued focus on integrating medical education with efforts to improve the quality of patient care in teaching medical centers1–6. Two of the core competencies of the American Council of Graduate Medical Education, systems-based practice and practice-based learning and improvement, incorporate aspects of quality improvement both at an individual and institutional level7.

Audits of medical records are commonly used in quality improvement initiatives to assess hospital performance and effect change8–10. The medical record provides insight into specific components of patient care including physician and nursing care, ancillary support services, and if polices and procedures are being followed. Unexpected admissions to an intensive care unit (ICU) represent a particularly important group of patients for review. The care of these patients requires optimal integration of clinical responses in order to minimize adverse outcomes and frequently represents an opportunity for improved patient care. Indeed, the observation that 75% of patients with unexpected admission to the ICU have unstable vital signs for a median of 6.5 h prior to being admitted to the ICU illustrates this opportunity for improvement and was the basis for the development of medical response teams11. These issues led us to review all admissions to the medical intensive care unit from the general medical floors with a primary focus on events proximal to admission.

METHODS

Study Population Our goal was to identify areas where care could be improved by establishing a parallel process involving medical house staff and nursing. The process involved fellows, chief residents and junior house staff, nurse unit managers, and nurses; it also included self-assessment exercises along with a structured M&M conference. Saint Vincent’s Hospital is a university teaching hospital affiliated with New York Medical College. The medical service consists of 225 beds, and the Medical ICU has 12 beds with approximately 700 admissions per year.

Measures From May 2007 to February 2008, the same Critical Care attending physician and a critical care fellow reviewed the medical records of all patients transferred from the general medical floors to the ICU within 24 h of arrival to the ICU. A survey of 17 yes/no questions (Appendix A online) that attempted to identify factors contributing to preventable adverse events was used to assess each case. Weekly, for each chart where an error was identified (Table 1), a multidisciplinary team convened to review these records. This group included, in addition to the critical care attending and fellow, a clinical nursing director and a chief medical resident. The case was reviewed, and the errors identified by the survey were discussed. The need for further interventions was agreed upon such as an educational strategy for those involved, if there was a need for a new policy to be made, and if a case was to be presented in the monthly Morbidity and Mortality conference. The clinical nurse director then brought this information to the nurse unit manager and the nurse(s) involved in the case on the unit where the error occurred. The chief medical resident did the same with the house officers involved in the case. Upon their review of the case, a self-assessment form was then completed by the house staff and the nurse (Appendix B online and Appendix C online), and an attribution was assigned. The house staff self-assement tool was based on a previously described format6. Errors in judgment involved synthesis integration and prioritization in decision-making. Knowledge deficits were related to inadequate information. For each adverse event/error, root causes were identified, and a corrective action plan was instituted.

Table 1.

Contributing Causes of Error

| Knowledge | Judgment | Supervision | Workload | Systems error | Communication | Documentation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inadequate differential diagnosis; incorrect choice of therapeutic interventions | Inability to recognize critical illness; inadequate triage decision | Senior resident not involved in care of unstable patient | Patient volume limiting adequate follow-up | Escalation of care policy not followed; delay in repeat vital sign measurements | Inadequate “handoff;” nurse manager not notified of unstable patient | No documentation of findings or plans at time of event or at follow-up |

| 32% | 40% | 5% | 3% | 66% | 18% | 27% |

The monthly department of medicine M&M conferences were based on cases derived from the reviews. Attendance was mandatory. The critical care attending and chief medical residents chose specific cases based on their educational value. An average of two cases were presented at each meeting. A critical care medicine attending reviewed the presentation with the presenting resident and led the conference. Each case was presented by the involved resident, and sequential diagnostic and therapeutic decisions were discussed. Some of the issues addressed were assessment of perfusion failure, timely resuscitation from shock, assessment of acute respiratory insufficiency, complications of anticoagulant therapy and assessment of acute neurologic changes. There was a particular focus on errors of judgment, and where appropriate, relevant guidelines and hospital policies were discussed. The intent of the conference was education rather than criticism, and an important part of the moderators’ role was to set the appropriate tone.

Analysis Linear regression modeling (StatView, Acton, MA) was used to analyze the relationship between time (predictor variable) and event incidence or team calling percent as dependent variables over the study period. Tests for the significance of the regression coefficients were determined. Differences between groups were assessed by chi-square analysis for categorical variables and the Student's t-test for continuous variables. Data are presented as mean ± SE. A p value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

We reviewed 194 medical records of patients transferred from the general medical floor to the ICU from May 2007 through February 2008. At least one error was identified in 45% of the records, and of these records, 90% contained multiple errors. Isolated physician errors were identified in 33% of the cases, isolated nursing errors in 8% of cases, and combined nursing and physician errors in over 50% of cases. The nature of the errors is illustrated in the Table. The most common type of physician errors were an error in judgment followed by those related to knowledge deficits. The most common type of nursing error was a systems error such as not escalating care.

Errors in frequency and documentation of vital signs in unstable patients and lack of escalation of care when the intern did not respond appropriately to a nurses concern were classified as issues related to unclear or nonexistent hospital policy. These types of errors were classified as systems errors and were identified in 66% of the charts with any type of error. These chart reviews led to the development of new policies and procedures. These new policies addressed frequency and documentation of vital signs for an unstable patient and criteria for escalation of care for unstable patients on the general medical service. Early on in the study, patient criteria were incorporated into an escalation of care policy for unstable patients on the general medical service which required an intern to notify a senior resident when any of the following were found1: a change in respiratory status as defined by a respiratory rate <6 or >35 breaths/minute, oxygen saturation <90% despite a FiO2 >50%, inability to clear secretions and stridor2, a systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg despite 1 l of normal saline administered over 30 min, heart rate >130 beats/minute, an acute change in urine output <50 ml over 4 h,3 and an unexplained change in consciousness or a prolonged seizure. In addition, any nurse or physician who was caring for a patient who met any of these criteria was instructed to place an emergent call to the medical emergency team (MET) or critical care medicine (CCM) service for immediate consultation.

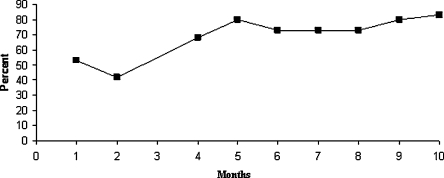

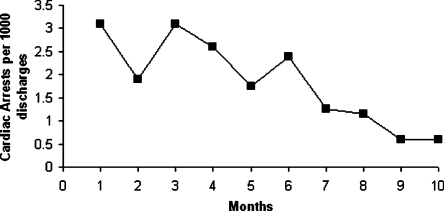

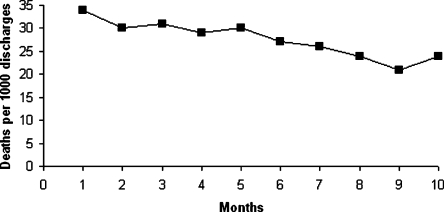

As a result of these audits and policy changes, the time to escalation of care, i.e., call to the MET/CCM from the time the patient had documented unstable vital signs and met calling criteria, decreased from a mean of 4.8 ± 1.0 h in May 2007 to 1.6 ± 0.5 h in February 2008 (p = 0.008). Nursing documentation of the change in the patients’ condition and follow-up actions increased from 65% percent to a high of 90% (p = 0.013). Nurse notification of a change in a patient’s condition increased from 65% to 100% (p = 0.011). The percent of MET/CCM calls for patients who met calling criteria increased from 53% to 80% (Fig. 1, p = 0.001). The number of patients in septic shock who had antibiotics administered within 2 h increased from 55% to 85% (p = 0.024). Repeat recording of vital signs in a timely manner in unstable patients on the medical floor increased from 35% to 85% (p = 0.001). The total number of errors decreased by 50% (p = 0.054). Errors in house staff judgment decreased by 60% (p = 0.03), while there was no change in the level of knowledge errors. The number of cardiac arrests on the medical service decreased from a peak of 3.1 per 1,000 patient discharges to 0.6 per 1,000 patient discharges in February (Fig. 2, p = 0.002). Hospital deaths on the Medicine Service decreased from 34 per 1,000 patient discharges to 24 per 1,000 patient discharges (Fig. 3, p = 0.0024). This was the death rate on all medical services including the ICU. During the same period the hospital case mix index (CMI) was unchanged.

Figure 1.

The percent of times the MET/CCM (medical emergency response team/critical care medicine) team was called when a patient met the calling criteria over consecutive months May 2007 through February 2008 (p = 0.001).

Figure 2.

The number of cardiac arrests on the medical service per 1,000 patient discharges over consecutive months May 2007 through February 2008 (p = 0.002).

Figure 3.

The number deaths on the medical service over consecutive months May 2007 through February 2008 (p = 0.024).

DISCUSSION

Integrating efforts to improve the quality of care with clinical training is a challenge in teaching hospitals1–6,12. Our approach involved the house staff at many different levels and in different ways. Fellows learned to evaluate delivery of care on an institutional level and critique not only the care of junior house staff and nurses, but also themselves and their peers. As part of the process, they also gained exposure into root cause analysis of individual cases. Chief residents were involved in interdisciplinary interactions with nursing and evaluation of house staff care. House staff had exposure to structured self-evaluation and a mentored detailed review of case-specific clinical decision making (M&M conference). This process advanced the goals of the core competencies of systems-based medical practice and practice-based learning and improvement while enhancing care on the general medical floors.

Audit and feedback have been used to improve medical care with mixed results13,14. Several factors account for the variability in reported results such as the nature of the audits and the feedback, the intensity and relevance of the feedback, and the recipients motivation to improve. In our case, we were able to demonstrate significant improvements in patient care. Our success was dependent on several variables. The reviewers had the respect of the institution. The review itself was honest, including self-criticism where applicable. A multidisciplinary approach was utilized, and on-going audits enabled us to monitor our success or failure in effecting change. Nursing and departmental support were important, particularly in those areas requiring changes in policies. Although a non-punitive educational approach was critical to gaining widespread acceptance by both house staff and nursing, we think it was important to make an attribution and encourage accountability.

We chose to audit the charts of patients admitted to the ICU. These patients represent a more complex group of patients that are more dependent on optimum delivery of clinical care and present an opportunity for earlier intervention to improve care11. The heterogeneity of the ICU population also provides an insight into a wide spectrum of clinical care issues in a hospital. Other groups of patients have been used for audit purposes, including patients suffering from cardiac arrest, unexplained deaths, cases with known medical errors or complications, and more recently patients requiring medical emergency team responses15.

The departmental M&M conference was an important part of our effort. The format we used is similar to that reported in surveys of academic internal medicine departments16. One important consideration is that the focus in our M&M conference is not on error per se, but instead, on more optimal approaches to patient care. This emphasis is consistent with the concept of creating a non-punitive environment for the open discussion of errors and deficiencies in care5,6,17,18. The decision-by-decision approach we used in reviewing each case was important given our observation that 40% of the charts containing errors involved suboptimal judgment. A format that is more knowledge directed might not allow for the type of discussion that is necessary to correct the underlying thought processes involved in suboptimal clinical judgment.

Our program was associated with significant improvements in care, which included policy changes, increased notification of unstable patients, a decrease in number of cardiac arrests and decreased hospital mortality. The lack of change in CMI over the period of evaluation mitigates against changes in the severity of illness as being a factor contributing to our results. While other institutions have integrated education with quality improvement using curriculum and the M&M conference, we are not aware of comparable clinical outcome data5,6,18. A program was recently described that was aimed at quality improvement and was centered on a modified M&M conference5. A number of policy changes were effected; however, no clinical outcome data were reported. Our program differs in its scope, its ongoing audit process, and extent of house staff and nursing involvement, which is not limited to the cases presented in the M&M conference.

It is difficult to directly assess the educational impact of our program. The outcome measurements indicate an improvement in the level of care, which may reflect primarily policy changes and a greater propensity for nursing staff to be vigilant and proactive, rather than improved bedside care by individual house staff. We hope that the educational benefits extend beyond simply identifying unstable patients and escalating care. The decrease in house staff errors of judgment suggest that this might be the case. The lack of change in knowledge base deficits is difficult to explain, but requires greater focus on the relevant knowledge base during the M&M conference. Differences in the house staff on the general medical floors during the two intervals may also limit comparisons.

Our program evolved because the critical care service has existed at Saint Vincents for over 30 years and has always provided assistance in the care of more complicated patients outside the ICU. There are other supervisors and patients that could substitute for the critical care attendings and ICU admissions. Indeed, although the majority of our cases for the M&M conference still come from our audits, we now include others that the chief residents and house staff perceive to have educational value. Our audit tool is subjective and could be refined by adding specific criteria regarding timeliness and incorporating guidelines, where applicable, regarding the appropriateness of care. There also are actions that could be taken to enhance the educational impact of our program. For example, we are considering incorporating the individual resident assessment into their portfolios with some self-directed learning activity. The use of a more formalized curriculum in quality improvement and involvement of house staff in quality improvement projects, as we do with our fellows, could also enhance the educational value of our program.1,3,4

In summary, we describe an audit-based multidisciplinary process that involves house staff at several training levels, a self-assessment tool and a focused M&M conference. The use of this process has resulted in significant changes in policies, more rapid assessment of unstable patients, decreased hospital arrests and improved hospital outcomes.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Evaluation of Patient Care Prior to Admission to the ICU (DOC 25 kb) (DOC 25 kb)

Case Review and House Officer Self-Assessment Form (DOC 26 kb) (DOC 26 kb)

Case Review and Nurse Self-Assessment Form (DOC 25 kb) (DOC 25 kb)

Conflict of Interest

None disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weingart SN, Tess A, Aronson DJ, MD SK. Creating a quality improvement elective for medical house officers. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:861–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30127.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orgine G, Headrick LA, Morrison L, Foster T. Teaching and assessing resident competence in practice-based learning and improvement. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:496–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30102.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oyler J, Vinci L, Arora V, Johnson J. Teaching internal medicine residents quality improvement techniques using the ABIM’s practice improvement modules. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:927–30. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0549-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomolo A, Lawrence R, Aron DC. A case study of translating ACGME practice-based learning and improvement requirement into reality: systems quality improvement projects as the key component to a comprehensive review. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;8:217–24. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2007.024729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bechotold ML, Scott S, Dellsperger KC, Hall LW, Nelson K, Cox KR. Educational quality improvement report: outcomes for a revised morbidity and mortality format that emphasizes patient safety. Postgrad Med J. 2008;84:211–16. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2006.021139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lucey C, Winnger D, Shim, R. She was going to die anyway…toward a more effective morbidity and mortality conference. APDM Spring Meeting. Fostering Professionalism in the Face of Change. New Orleans, LA, April 2004.

- 7.ACGME Outcomes Project. Enhancing residency education through outcomes assessment. Available at: www.acgme.org/outcome/assess/toolbox.asp. Accessed June 1, 2010.

- 8.Ursprung R, Gray J, Edwards W, Horbar J, Nickerson J, Pisek P, Shiono P, Suresh G, Goldmann D. Real time safety audits: improving safety every day. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14:284–89. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.012542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berk M, Callaly T, Hyland M. The evolution of clinical audit as a tool for quality improvement. J Eval Clin Praact. 2003;9:251–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.2003.00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beckman U, Boehringer C, Carless R, Gilles D, Runciman W, Wu A, Pronovest P. Evaluation of two methods for quality improvement in intensive care: facilitated incidence monitoring and retrospective medical chart review. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1006–11. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000060016.21525.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buist MD, Jarnolowski F, Burton PR, Bernard SA, Waxman BP, Anderson J. Recognizing clinical instability in hospital patients before cardiac arrest or unplanned admission to intensive care. A pilot study in a tertiary care hospital. Med J Aust199;171:22-25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Aston CM. “Invisible doctors”: making a case for involving medical residents in hospital quality improvement plans. Acad Med. 1993;68:823–24. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199311000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamrvedt G, Young J, Kristoffersen D, O’Brien M, Oxman A. Audit an feedback: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev 2006 Apr 19; 2: CD000259. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Hearshaw H, Harker R, Baker R, Grimshaw G. Are audits wasting resources by measuring the wrong things? A survey of methods used to select audit review criteria. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:24–28. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braithwaite RS, Vita MA, Mahidhara R, Simmons RL, Stuart S. an members of the Medical Emergency Response Improvement Team (MERIT). Use of medical emergency team (MET) response to detect medical errors. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:255–59. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2003.009324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oralnder J, Fincke G. Morbidity and mortality conferecne. A Survey of academic internal medicine departments. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:656–58. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20824.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.VA National Center for Patient Safety Case Conference-Modified M&M. www.va.gov/.../curriculum/TeachingMethods/PtSafety_Case_Conference_Format/index.html Accessed June 1, 2010.

- 18.Kravet S, Howell E, Wright E. Morbidity and mortality conference, Grand Rounds, and the ACGME’s Core Competencies. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:1192–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00523.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Evaluation of Patient Care Prior to Admission to the ICU (DOC 25 kb) (DOC 25 kb)

Case Review and House Officer Self-Assessment Form (DOC 26 kb) (DOC 26 kb)

Case Review and Nurse Self-Assessment Form (DOC 25 kb) (DOC 25 kb)