Abstract

We present an annotation pipeline that accurately predicts exon–intron structures and protein-coding sequences (CDSs) on the basis of full-length cDNAs (FLcDNAs). This annotation pipeline was used to identify genes in 10 plant genomes. In particular, we show that interspecies mapping of FLcDNAs to genomes is of great value in fully utilizing FLcDNA resources whose availability is limited to several species. Because low sequence conservation at 5′- and 3′-ends of FLcDNAs between different species tends to result in truncated CDSs, we developed an improved algorithm to identify complete CDSs by the extension of both ends of truncated CDSs. Interspecies mapping of 71 801 monocot FLcDNAs to the Oryza sativa genome led to the detection of 22 142 protein-coding regions. Moreover, in comparing two mapping programs and three ab initio prediction programs, we found that our pipeline was more capable of identifying complete CDSs. As demonstrated by monocot interspecies mapping, in which nucleotide identity between FLcDNAs and the genome was ∼80%, the resultant inferred CDSs were sufficiently accurate. Finally, we applied both inter- and intraspecies mapping to 10 monocot and dicot genomes and identified genes in 210 551 loci. Interspecies mapping of FLcDNAs is expected to effectively predict genes and CDSs in newly sequenced genomes.

Keywords: interspecies mapping, full-length cDNA, CDS identification, plant genome

1. Introduction

Following the sequencing of the Arabidopsis thaliana genome in 20001 and the Oryza sativa genome in 2005,2 several complete or nearly complete flowering plant genomes have been released.3–10 In addition, large-scale sequencing projects of important cereal crops are currently being undertaken by international consortia, including the International Barley Sequencing Consortium (http://www.barleygenome.org) and the International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium (http://www.wheatgenome.org).11,12 It is expected that accelerating genome sequencing technologies, such as next-generation sequencing, will lead to a dramatic increase in the genomic DNA data to be annotated.13,14 Therefore, to cope with the deluge of emerging sequence information, the development of an efficient annotation system is needed.

Exon–intron structures and the protein-coding sequences (CDSs) in genome sequences can be predicted either by ab initio predictions or by sequence similarity methods. While ab initio gene prediction programs may produce erroneous exon–intron structures,15–17 sequence similarity approaches generally show better results, although the number of available sequences in the current databases limits the number of genes that can be predicted. Tens of thousands of full-length cDNAs (FLcDNAs), which can be used to accurately determine exon–intron structures,4,18–21 are available for O. sativa, Zea mays, and A. thaliana, and the quality of their genome annotations is generally thought to be high. In other species, however, sufficient numbers of FLcDNAs are not necessarily available for the corresponding genomes. To fully utilize FLcDNA resources, algorithms for interspecies mapping, which show better gene structure annotation than ab initio predictions, have been developed.22,23

Identification of CDS regions is a crucial step in genome annotation. However, low sequence conservation at the 5′- and 3′-ends of FLcDNAs between different species frequently results in truncated CDSs. To solve this problem, we present a pipeline that is based on interspecies FLcDNA mapping to genomes, which predicts exon–intron structures and the CDSs. In this pipeline, both ends of truncated CDSs are extended so that the complete CDSs are obtained. Our FLcDNA mapping pipeline was validated and compared with two other cDNA mapping programs—sim4cc23 and GeneSeqer24—as well as three ab initio gene prediction methods. In addition, we estimated how many sequences would be needed for exhaustive gene identification by interspecies mapping. Finally, for comprehensive gene identification, we applied our pipeline to the 10 genomes of the following flowering plants: O. sativa cv. Nipponbare, Z. mays, Sorghum bicolor, Brachypodium distachyon, A. thaliana, Lotus japonicus, Populus trichocarpa, Glycine max, Vitis vinifera, and Carica papaya.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. FLcDNAs, genome sequences, and reference data sets

We retrieved 179 991 FLcDNAs from A. thaliana,18,20,21 O. sativa,25,26 O. rufipogon,27 Hordeum vulgare,28 Z. mays,29–31 G. max,32 P. trichocarpa,33 Triticum aestivum,34 and Solanum lycopersicum35 from the sources listed in Supplementary Table S1. The genome sequences and annotations of O. sativa,2 S. bicolor,3 Z. mays,4 B. distachyon,5 A. thaliana,36 P. trichocarpa,6 V. vinifera,7 C. papaya,8 L. japonicus,9 and G. max10 were downloaded from the web sites listed in Supplementary Table S2. For validation of predicted exon–intron structures and the CDSs, reference data sets, based on the intraspecies mapping method of the Rice Annotation Project,19,37 were used (Supplementary Table S3). To enhance the accuracy of the validations, we used only the loci that had the same CDS structures as the corresponding CDSs from other sources: the MSU6.138 data set for O. sativa, the TAIR 9.0 representative CDSs36 for A. thaliana, and the B73 RefGen_v1 Filtered Gene Set4 for Z. mays. If more than one CDS was predicted in a locus of Z. mays, the longest one was selected.

2.2. Pipeline of interspecies mapping and CDS identification

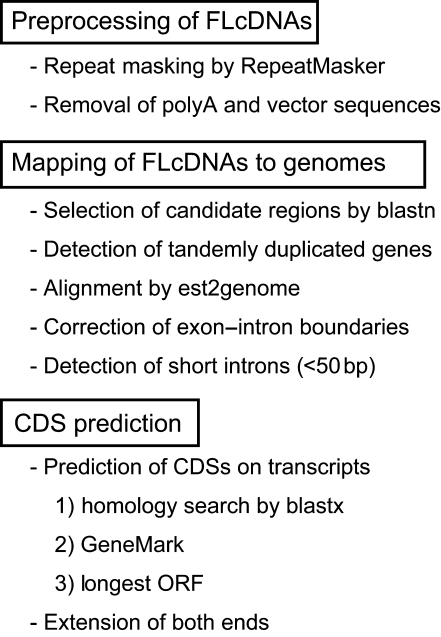

Figure 1 shows an overview of our new interspecies mapping pipeline that simultaneously identifies CDSs on predicted loci. Repetitive sequences on FLcDNAs were masked by RepeatMasker (http://www.repeatmasker.org) with the MIPS Repeat Element Database (mips-REdat 4.3)39 and the ‘complete set’ of the Triticeae Repeat Sequence Database release 10 (http://wheat.pw.usda.gov/ITMI/Repeats/). Vector sequences were removed by the cross_match program. PolyA stretches were discarded using a custom-made program. Sequences with total unmasked lengths of 30 bp or more were used.

Figure 1.

An overview of the interspecies mapping algorithm.

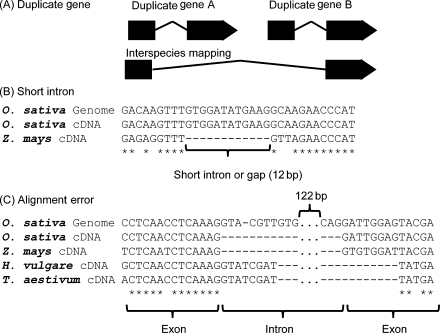

Before precise alignment between FLcDNAs and a genome, we first used blastn to approximately define genomic regions that correspond to FLcDNAs. We used est2genome40 to align FLcDNAs to the corresponding genomic regions selected by blastn. Next, we invented methods to solve three problems with interspecies alignment (Fig. 2). Because tandemly duplicated genes tended to be accidentally combined into one gene during alignments, we divided these regions such that each region contained only one candidate gene and aligned the FLcDNAs to each region (Supplementary Fig. S1). To improve the detection of exon–intron boundaries by est2genome, multiple lines of transcript evidence were employed as follows. We scored introns using linear discriminant analyses, based on a splice site model and alignments around the splice sites, such that the most probable intron is selected (for details, see Supplementary Methods). Finally, we also discarded short introns whose length was <50 bp because the percentage of such short introns identified by intraspecies mapping was 10 times smaller than that by interspecies mapping (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Figure 2.

Problems with interspecies mapping. Alignment errors between a given FLcDNA and genome sequence pair have three possible causes. (A) Multiple duplicated genes encompassed by a single cDNA. (B) Erroneously short introns. (C) Alignment errors around splice sites.

CDSs in predicted transcripts were determined on the basis of homology searches by blastx41 against the Uniprot42 and RefSeq43 databases. If no homologs were found in the protein databases, GeneMark44 was used, or the longest CDSs were employed. Either the 5′- or the 3′-end was frequently truncated after interspecies mapping because of the relatively low sequence conservation observed for CDS termini. Therefore, both ends of the mapped transcripts were extended so that predicted CDSs contained the start and the stop codons. Finally, from a set of overlapping transcripts in a given locus, a single representative transcript that had the longest CDS was selected.

2.3. Evaluation of gene predictions

To evaluate our methods, we compared the exon–intron structures and the CDSs derived from the interspecies mapping with the aforementioned reference sets of O. sativa, Z. mays, and A. thaliana. We evaluated only the predictions that overlapped with the reference set. Exon–intron boundaries, introns, all introns within a reference CDS (referred to as ‘all introns’ hereafter), and the entire CDSs were examined. We evaluated mapping results for each FLcDNA. Specificity (SP) was defined as TP/(TP + FP), and sensitivity (SN) was defined as TP/(TP + FN), where TP is the number of true positives, FP is the number of false positives, and FN is the number of false negatives. Single-exon genes were considered only in the CDS evaluation because they have no introns. To evaluate the CDS extension process, we examined whether the start and the stop codons of the reference set were included in the predictions. Reference CDSs that did not overlap with predictions were not used.

To investigate relationships between the nucleotide identity and mapping ratio, the nucleotide identity between a given FLcDNA and the genomic locus to which it was assigned by est2genome was calculated. The mapping ratio represents the percentage of FLcDNAs that were mapped by est2genome divided by all FLcDNAs used. To investigate correlations between nucleotide identity and SP, we selected representative CDSs for each species and calculated the SP of gene predictions between species for genomes and FLcDNAs.

2.4. Comparison with other programs

The newly developed annotation pipeline described in the present work was compared with three ab initio gene prediction tools, including GeneZilla,45 GlimmerHMM,46 and GeneMark.hmm.47 The options for O. sativa gene predictions were employed in GlimmerHMM and GeneMark.hmm predictions. For GeneZilla, we randomly selected 5000 genes from the rice annotation37 and used 4124, which contained both the start and the stop codons, to create a training model. Our annotation pipeline also was compared with other cDNA mapping programs, including sim4cc23 and GeneSeqer.24,48 We mapped 71 801 monocot FLcDNAs to the O. sativa genome with the default parameters of sim4cc and GeneSeqer. Alignments that covered 40% or more of FLcDNAs were selected for comparison of prediction efficiency. For the GeneSeqer predictions, the longest representative CDS was selected if multiple transcripts were aligned to one locus.

2.5. Estimating the number of shared genes in monocots

If FLcDNAs are collected randomly, the number of FLcDNAs per locus obeys a Poisson distribution. We estimated the number of all loci (N) from the number of loci found (L) and the number of FLcDNAs mapped (M) using the following formula49:

Given L and M, N can be estimated. To cover 99% of the genomic loci, L/N = 0.99. Hence, the number of FLcDNAs needed to cover 99% of the loci is:

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Validation of interspecies mapping

To evaluate our pipeline, we aligned 71 801 FLcDNAs obtained from three monocots (H. vulgare, Z. mays, and T. aestivum) to the O. sativa genome. From this, a total of 54 004 (75.2%) non-rice monocot FLcDNAs were mapped and clustered into 22 500 loci, from which 22 142 CDSs were predicted in the O. sativa genome. If these CDSs overlapped with the reference CDSs, we examined SP and SN for exon–intron boundaries, introns, all introns, and the entire CDSs (Table 1). As expected,22 mapping-based methods, including our pipeline, generally showed higher SP and SN at the intron and all-introns levels than the ab initio methods; however, both the SP and the SN drastically dropped at the CDS level when using GeneSeqer. This is partly because the 5′- and 3′-ends of CDSs are poorly conserved and cannot be aligned in many cases. In fact, a significant number of O. sativa start or stop codons were not found in all the three mapping-based methods without extension of 5′- and 3′-ends (Table 2). In contrast, the extension of the start and the stop codons in our CDS identification led to the inclusion of more than 88 and 91% of these codons, respectively (Table 2), which were better than the other two methods. After the CDS extension process, the SP and SN of our pipeline increased by 12.2 and 9.8%, respectively, at the CDS level, which suggests that this extension step seems to be of great benefit for accurate CDS prediction.

Table 1.

Comparison of SP and SN in CDSs

| Method | Exon–intron boundaryb |

Intronb |

All intronsb |

Entire CDS |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SP | SN | SP | SN | SP | SN | SP | SN | |

| This study | 94.6 | 75.5 | 92.6 | 74.2 | 58.5 | 49.5 | 55.5 | 44.4 |

| GeneSeqer | 87.9 | 77.9 | 83.7 | 75.5 | 42.3 | 38.9 | 3.3 | 2.8 |

| Sim4cca | 90.8 | 74.3 | 87.9 | 73.0 | 40.5 | 47.2 | –c | –c |

| GeneMark.hmm | 87.6 | 87.6 | 76.2 | 80.7 | 22.1 | 25.6 | 24.0 | 25.1 |

| GeneZilla | 87.4 | 77.0 | 76.4 | 68.3 | 29.9 | 30.7 | 31.8 | 35.1 |

| GlimmerHMM | 91.3 | 75.5 | 81.7 | 69.1 | 36.3 | 35.8 | 39.4 | 38.7 |

All values are expressed as percentages (%).

aSim4cc does not report a representative transcript in a single locus, so each mapping result was evaluated separately.

bCDS regions of the reference set were evaluated.

cSim4cc does not predict CDS regions.

Table 2.

Percentage of O. sativa start and stop codons included in the alignments

| Method | Before extension (%) |

After extension (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | Stop | Start | Stop | |

| This study | 67.3 | 72.1 | 88.9 | 91.2 |

| GeneSeqer | 49.8 | 55.1 | 79.7 | 82.5 |

| Sim4cca | 45.7 | 58.1 | 82.2 | 85.7 |

aLongest CDSs were selected.

Low sequence similarity in untranslated regions (UTRs) caused more serious problems. The SP of introns in UTRs was <33%, which was much lower than the above 90% SP of non-UTR-based CDSs (Supplementary Table S4). This result indicates that interspecies mapping should focus on CDSs rather than the entire transcripts.

Improvement of gene structure identification in three steps (detection of tandem duplications, removal of short introns, and exon–intron boundary corrections) of our pipeline was validated (Supplementary Table S5). The pipeline detected candidate regions of tandem duplication in 11 287 alignments (see Supplementary Methods), and they were consequently reflected in 3510 loci. In addition, 10 097 short introns (<50 bp) to be removed were found in 4480 loci. As a result, 7.5% SP and 2.5% SN at the all-introns level were increased in the three steps (Supplementary Table S5). In this way, without sacrificing SN, SP was largely improved.

3.2. Applicability of interspecies mapping

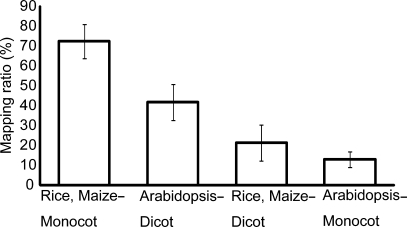

Although interspecies mapping is useful for detecting loci in related species, FLcDNAs from distantly related species may lead to incorrect predictions. To test the applicability of the interspecies mapping approach, we examined the relationship between species classification and mapping ratios. For this purpose, we used the O. sativa, Z. mays, and A. thaliana genomes because they had large numbers of FLcDNAs that could be used to create high-quality reference sets. We applied monocot FLcDNAs to the O. sativa and Z. mays genomes and dicot FLcDNAs to the A. thaliana genome. We also applied our algorithm to a monocot–dicot comparison. Figure 3 shows the relationship between the mapping ratio and the species classification. In general, mapping within both monocots and dicots yielded a higher mapping ratio than mapping between a monocot and a dicot. Therefore, comparisons between distantly related species, such as a monocot and a dicot, do not seem to be appropriate. Within-monocot comparisons displayed a higher ratio than within-dicot comparisons. In addition, monocot-to-Arabidopsis mapping showed a lower mapping ratio compared with dicot-to-rice/maize mapping, although evolutionary distances of these two comparisons were same. This difference of mapping ratios is possible because A. thaliana might have undergone genome reduction that led to a lineage-specific deletion of genes.

Figure 3.

Relationship between species classification and mapping ratio. The horizontal axis indicates the classification, and the vertical axis indicates the mapping ratio. We mapped FLcDNAs from three monocots and four dicots to the O. sativa (rice) and Z. mays (maize) genomes, and FLcDNAs from three dicots and six monocots to the A. thaliana (Arabidopsis) genome. Bars at the top of the boxes represent the standard deviations.

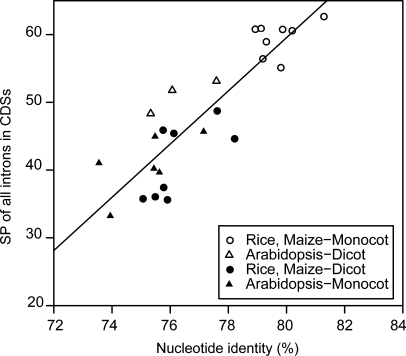

To further ascertain the degree to which nucleotide differences affect the accuracy of the exon–intron structure predictions generated by interspecies mapping, we examined the relationship between the nucleotide sequence identity and the SP of all introns in our representative CDSs (Fig. 4). The correlation coefficient for this relationship is 0.88 (P = 8.6 × 10−9). This suggests that interspecies mapping within closely related species should detect a significant number of true exon–intron structures. If the nucleotide identity is more than 80%, the SP of all introns in a given set of CDSs is expected to be ∼60% or more.

Figure 4.

Correlation between nucleotide identity and SP. The horizontal axis indicates the nucleotide identity, and the vertical axis indicates the SP of all introns in CDSs. Open circles and triangles indicate within-monocot and -dicot mapping, respectively, and filled circles and triangles indicate between-dicot and -monocot mapping, respectively. The straight line shows the linear regression for all data (r = 0.88).

Figure 4 also shows that, for the monocot genomes examined, monocot FLcDNAs provided accurate results, whereas the dicot exon–intron structures that were inferred were relatively inaccurate because the dicot genomes used were derived from diverse species. Because all monocots employed in the present study belong to Poaceae (the grass family), their divergence time is relatively short (50–70 million years or less).50 In contrast, the available dicot FLcDNAs belong to multiple families that are more divergent: A. thaliana is in Brassicaceae, S. lycopersicum in Solanaceae, G. max in Fabaceae, and P. trichocarpa in Salicaceae. For example, A. thaliana and P. trichocarpa probably split around 100–120 million years ago.6 In fact, nucleotide identities among the dicots A. thaliana, P. trichocarpa, S. lycopersicum, and G. max ranged from 75% to 78%, which is lower than the ∼80% identity detected among monocots. To accurately determine the exon–intron structures within genomes, FLcDNAs from the same family would be preferable.

3.3. How many FLcDNAs are necessary for genome annotation?

A genome is composed of regions that are conserved among species and regions that are specific to a lineage, but interspecies mapping can identify only conserved genes. Here, on the basis of the interspecies mapping results, we estimated the numbers of conserved genes in monocots. If random sampling of FLcDNAs is assumed, the number of loci inferred from the number of mapped FLcDNAs obeys a Poisson distribution (see the ‘Materials and methods’ section). We estimated the number of loci shared between O. sativa and the other monocots to be ∼18 000 because 17 402 loci were identified among 54 004 transcripts. Zea mays and S. bicolor seem to contain ∼21 000 and ∼24 000 conserved loci, respectively. Note that, for this estimation, a single genomic region was selected if an FLcDNA was homologous to multiple regions. We also should note that, because the sampling of FLcDNAs was not completely random, the estimated numbers should be the lower limits. In addition, to more accurately estimate the total number of loci, we must consider lineage-specific genes that are undetectable by sequence similarity.

Next, we estimated the number of FLcDNAs needed to annotate homologous CDSs among monocot species. Assuming that ∼83 000 FLcDNAs would need to be used to cover 99% of the ∼18 000 loci in O. sativa, with a mapping ratio of 0.75, a total of ∼110 000 FLcDNAs obtained from closely related species would be necessary for prediction of CDSs in O. sativa. This number may be an underestimate if FLcDNAs are not randomly cloned, but most of the genes should be included if more than 100 000 clones are collected from closely related species. Therefore, because there are more than 120 000 FLcDNAs in monocots, new genomes of monocots, such as wheat and barley, would be effectively annotated by using interspecies mapping.

3.4. CDS prediction in 10 species

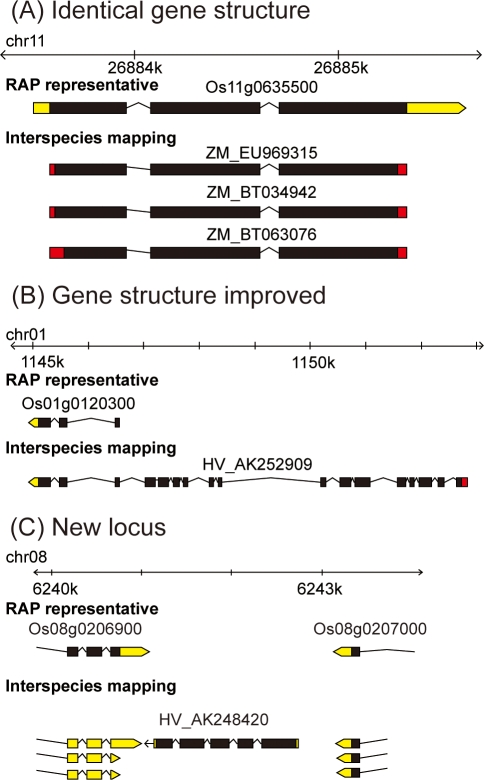

We applied the interspecies mapping procedure to predict exon–intron structures and CDSs in 10 plant genomes: O. sativa, Z. mays, A. thaliana, S. bicolor, B. distachyon, P. trichocarpa, G. max, V. vinifera, L. japonicus, and C. papaya. Table 3 shows the number of the FLcDNAs used, the mapped FLcDNAs, and the CDS loci. Three examples of our interspecies mapping results for O. sativa were compared with the exon–intron structures of annotation release 2 of the rice genome (RAP2), which was based on an intraspecies mapping procedure37 (Fig. 5). First, three FLcDNAs derived from Z. mays were mapped to the Os11g0635500 locus of RAP2, and their 5′- and 3′-ends were extended. These predicted CDSs displayed exon–intron structures that were identical to those determined by an O. sativa FLcDNA with a CDS and UTRs (Fig. 5A). Second, the representative structure at the Os01g0120300 locus determined by an FLcDNA (Fig. 5B) was apparently truncated at the 5′-end. In contrast, the interspecies mapping results predicted the complete exon–intron structures including the start and the stop codons. Finally, a H. vulgare FLcDNA (AK248420) predicted a novel transcribed locus candidate between Os08g0206900 and Os08g0207000 that had not yet been detected (Fig. 5C). In total, we identified 492 new loci that were missing in release 2 of the rice annotation. The numbers of new loci found in the 10 plant species examined are shown in Table 3. In addition, we provide exon–intron structure and CDS data that were created by a combination of interspecies and intraspecies mapping methods (Supplementary Table S6). This comprehensive data set, which contains 210 551 genes from 10 species, will be useful for a large-scale sequence analysis of these flowering plants.

Table 3.

Interspecies mapping results in 10 genomes

| Species | O. sativa | Z. mays | S. bicolor | B. distachyon | A. thaliana | P. trichocarpa | V. vinifera | G. max | L. japonicus | C. papaya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLcDNA | 71 801 | 60 068 | 120 722 | 120 722 | 22 594 | 53 875 | 58 534 | 53 823 | 58 534 | 58 534 |

| Mapped FLcDNAs | 54 004 (75.2%) | 40 343 (67.2%) | 96 142 (79.6%) | 87 174 (72.2%) | 8461 (37.4%) | 24 502 (49.2%) | 27 031 (46.2%) | 22 738 (42.2%) | 22 729 (38.8%) | 26 717 (45.6%) |

| CDS loci | 22 142 | 29 001 | 28 446 | 24 522 | 5564 | 15 039 | 11 002 | 17 953 | 12 083 | 8212 |

| New loci | 492 | 718 | 1992 | 1638 | 45 | 392 | 496 | 245 | – | – |

Figure 5.

Examples of interspecies mapping to the O. sativa genome. Oryza sativa exon–intron structures (RAP representative) were retrieved from RAP-DB.37 The two characters before the FLcDNA accession numbers indicate the species names: HV for H. vulgare and ZM for Z. mays. Black, red, and yellow regions represent CDSs, extended CDSs, and UTR regions, respectively. (A) The same exon–intron structures between an O. sativa FLcDNA (INSDC: AK067543) and Z. mays FLcDNAs with extended CDS regions. (B) A truncated FLcDNA of O. sativa (INSDC: AK106806) and a complete structure predicted by an H. vulgare FLcDNA. (C) A new locus identified by a H. vulgare FLcDNA (INSDC: AK248420) in a region between Os08g0206900 and Os08g0207000.

Because more than 120 000 monocot FLcDNAs are currently available, this FLcDNA data set seems to be large enough to annotate conserved genes in monocot genomes. We could provide relatively a high-quality CDS annotation using intraspecies and interspecies mapping. However, for dicot genomes, the 58 534 dicot FLcDNAs currently available do not seem to be sufficient to predict most of the gene structures. We expect that 50 000 more FLcDNAs from any dicots might improve the coverage of gene prediction in dicot genomes. To complement the shortage of FLcDNAs and explore lineage-specific genes, ab initio prediction programs can be used in combination with interspecies and intraspecies mapping. Interspecies FLcDNA mapping, partly supported by ab initio predictions, will be of great use for cost-effective annotation of newly released agronomically important plant genomes, such as those of wheat and barley.

4. Availability

A web service for the mapping of FLcDNAs to genomic DNA sequences is available (http://fpgp.dna.affrc.go.jp/index.html). Users can submit a sequence of up to 1 Mb and can specify dicot or monocot FLcDNAs to be mapped. After completion of the requested prediction, an URL indicating the prediction results is sent by e-mail. The CDS identification results of 10 plant genomes are available at our web site (http://fpgp.dna.affrc.go.jp/download.html).

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at www.dnaresearch.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries of Japan (Genomics for Agricultural Innovation, GIR-1001).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Edited by Katsumi Isono

References

- 1.Arabidopsis Genome Initiative. Analysis of the genome sequence of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 2000;408:796–815. doi: 10.1038/35048692. doi:10.1038/35048692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Rice Genome Sequencing Project. The map-based sequence of the rice genome. Nature. 2005;436:793–800. doi: 10.1038/nature03895. doi:10.1038/nature03895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paterson A.H., Bowers J.E., Bruggmann R., et al. The Sorghum bicolor genome and the diversification of grasses. Nature. 2009;457:551–6. doi: 10.1038/nature07723. doi:10.1038/nature07723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schnable P.S., Ware D., Fulton R.S., et al. The B73 maize genome: complexity, diversity, and dynamics. Science. 2009;326:1112–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1178534. doi:10.1126/science.1178534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The International Brachypodium Initiative. Genome sequencing and analysis of the model grass Brachypodium distachyon. Nature. 2010;463:763–8. doi: 10.1038/nature08747. doi:10.1038/nature08747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tuskan G.A., Difazio S., Jansson S., et al. The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray) Science. 2006;313:1596–604. doi: 10.1126/science.1128691. doi:10.1126/science.1128691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaillon O., Aury J.M., Noel B., et al. The grapevine genome sequence suggests ancestral hexaploidization in major angiosperm phyla. Nature. 2007;449:463–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06148. doi:10.1038/nature06148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ming R., Hou S., Feng Y., et al. The draft genome of the transgenic tropical fruit tree papaya (Carica papaya Linnaeus) Nature. 2008;452:991–6. doi: 10.1038/nature06856. doi:10.1038/nature06856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sato S., Nakamura Y., Kaneko T., et al. Genome structure of the legume, Lotus japonicus. DNA Res. 2008;15:227–39. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsn008. doi:10.1093/dnares/dsn008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmutz J., Cannon S.B., Schlueter J., et al. Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature. 463:178–83. doi: 10.1038/nature08670. doi:10.1038/nature08670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schulte D., Close T.J., Graner A., et al. The international barley sequencing consortium—at the threshold of efficient access to the barley genome. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:142–7. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.128967. doi:10.1104/pp.108.128967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paux E., Sourdille P., Salse J., et al. A physical map of the 1-gigabase bread wheat chromosome 3B. Science. 2008;322:101–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1161847. doi:10.1126/science.1161847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quinn N.L., Levenkova N., Chow W., et al. Assessing the feasibility of GS FLX pyrosequencing for sequencing the Atlantic salmon genome. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:404. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-404. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-9-404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wicker T., Schlagenhauf E., Graner A., Close T.J., Keller B., Stein N. 454 sequencing put to the test using the complex genome of barley. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:275. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-275. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-7-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bennetzen J.L., Coleman C., Liu R., Ma J., Ramakrishna W. Consistent over-estimation of gene number in complex plant genomes. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2004;7:732–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.09.003. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cruveiller S., Jabbari K., Clay O., Bernardi G. Incorrectly predicted genes in rice? Gene. 2004;333:187–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.02.039. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2004.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jabbari K., Cruveiller S., Clay O., Le Saux J., Bernardi G. The new genes of rice: a closer look. Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9:281–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.04.006. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexandrov N.N., Troukhan M.E., Brover V.V., Tatarinova T., Flavell R.B., Feldmann K.A. Features of Arabidopsis genes and genome discovered using full-length cDNAs. Plant Mol. Biol. 2006;60:69–85. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-2564-9. doi:10.1007/s11103-005-2564-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Itoh T., Tanaka T., Barrero R.A., et al. Curated genome annotation of Oryza sativa ssp. japonica and comparative genome analysis with Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Res. 2007;17:175–83. doi: 10.1101/gr.5509507. doi:10.1101/gr.5509507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seki M., Narusaka M., Kamiya A., et al. Functional annotation of a full-length Arabidopsis cDNA collection. Science. 2002;296:141–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1071006. doi:10.1126/science.1071006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seki M., Satou M., Sakurai T., et al. RIKEN Arabidopsis full-length (RAFL) cDNA and its applications for expression profiling under abiotic stress conditions. J. Exp. Bot. 2004;55:213–23. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh007. doi:10.1093/jxb/erh007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang C., Mao L., Ware D., Stein L. Evidence-based gene predictions in plant genomes. Genome Res. 2009;19:1912–23. doi: 10.1101/gr.088997.108. doi:10.1101/gr.088997.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou L., Pertea M., Delcher A.L., Florea L. Sim4cc: a cross-species spliced alignment program. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e80. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp319. doi:10.1093/nar/gkp319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brendel V., Xing L., Zhu W. Gene structure prediction from consensus spliced alignment of multiple ESTs matching the same genomic locus. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1157–69. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth058. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bth058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kikuchi S., Satoh K., Nagata T., et al. Collection, mapping, and annotation of over 28,000 cDNA clones from japonica rice. Science. 2003;301:376–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1081288. doi:10.1126/science.1081288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu X., Lu T., Yu S., et al. A collection of 10,096 indica rice full-length cDNAs reveals highly expressed sequence divergence between Oryza sativa indica and japonica subspecies. Plant Mol. Biol. 2007;65:403–15. doi: 10.1007/s11103-007-9174-7. doi:10.1007/s11103-007-9174-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu T., Yu S., Fan D., et al. Collection and comparative analysis of 1888 full-length cDNAs from wild rice Oryza rufipogon Griff. W1943. DNA Res. 2008;15:285–95. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsn018. doi:10.1093/dnares/dsn018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sato K., Shin I.T., Seki M., et al. Development of 5006 full-length CDNAs in barley: a tool for accessing cereal genomics resources. DNA Res. 2009;16:81–9. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsn034. doi:10.1093/dnares/dsn034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alexandrov N.N., Brover V.V., Freidin S., et al. Insights into corn genes derived from large-scale cDNA sequencing. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009;69:179–94. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9415-4. doi:10.1007/s11103-008-9415-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jia J., Fu J., Zheng J., et al. Annotation and expression profile analysis of 2073 full-length cDNAs from stress-induced maize (Zea mays L.) seedlings. Plant J. 2006;48:710–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02905.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soderlund C., Descour A., Kudrna D., et al. Sequencing, mapping, and analysis of 27,455 maize full-length cDNAs. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000740. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000740. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Umezawa T., Sakurai T., Totoki Y., et al. Sequencing and analysis of approximately 40,000 soybean cDNA clones from a full-length-enriched cDNA library. DNA Res. 2008;15:333–46. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsn024. doi:10.1093/dnares/dsn024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ralph S.G., Chun H.J., Cooper D., et al. Analysis of 4,664 high-quality sequence-finished poplar full-length cDNA clones and their utility for the discovery of genes responding to insect feeding. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-57. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-9-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mochida K., Yoshida T., Sakurai T., Ogihara Y., Shinozaki K. TriFLDB: a database of clustered full-length coding sequences from Triticeae with applications to comparative grass genomics. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:1135–46. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.138214. doi:10.1104/pp.109.138214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aoki K., Yano K., Suzuki A., et al. Large-scale analysis of full-length cDNAs from the tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) cultivar Micro-Tom, a reference system for the Solanaceae genomics. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:210. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-210. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-11-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swarbreck D., Wilks C., Lamesch P., et al. The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): gene structure and function annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D1009–14. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm965. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tanaka T., Antonio B.A., Kikuchi S., et al. The Rice Annotation Project Database (RAP-DB): 2008 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D1028–33. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ouyang S., Zhu W., Hamilton J., et al. The TIGR rice genome annotation resource: improvements and new features. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D883–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl976. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spannagl M., Noubibou O., Haase D., et al. MIPSPlantsDB–plant database resource for integrative and comparative plant genome research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D834–40. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl945. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mott R. EST_GENOME: a program to align spliced DNA sequences to unspliced genomic DNA. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1997;13:477–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/13.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altschul S.F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E.W., Lipman D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–10. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uniprot Consortium. The Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) 2009. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D169–74. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn664. doi:10.1093/nar/gkn664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pruitt K.D., Tatusova T., Klimke W., Maglott D.R. NCBI reference sequences: current status, policy and new initiatives. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D32–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn721. doi:10.1093/nar/gkn721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Borodovsky M., McIninch J. Recognition of genes in DNA sequence with ambiguities. Biosystems. 1993;30:161–71. doi: 10.1016/0303-2647(93)90068-n. doi:10.1016/0303-2647(93)90068-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Majoros W.H., Pertea M., Delcher A.L., Salzberg S.L. Efficient decoding algorithms for generalized hidden Markov model gene finders. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-16. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-6-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Majoros W.H., Pertea M., Salzberg S.L. TigrScan and GlimmerHMM: two open source ab initio eukaryotic gene-finders. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:2878–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth315. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bth315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lomsadze A., Ter-Hovhannisyan V., Chernoff Y.O., Borodovsky M. Gene identification in novel eukaryotic genomes by self-training algorithm. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:6494–506. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki937. doi:10.1093/nar/gki937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Usuka J., Zhu W., Brendel V. Optimal spliced alignment of homologous cDNA to a genomic DNA template. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:203–11. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.3.203. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/16.3.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lander E.S., Waterman M.S. Genomic mapping by fingerprinting random clones: a mathematical analysis. Genomics. 1988;2:231–9. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(88)90007-9. doi:10.1016/0888-7543(88)90007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salse J., Bolot S., Throude M., et al. Identification and characterization of shared duplications between rice and wheat provide new insight into grass genome evolution. Plant Cell. 2008;20:11–24. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.056309. doi:10.1105/tpc.107.056309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.