Abstract

Psychosis has been associated with aberrant brain activity concurrent with both the anticipation and integration of monetary outcomes. The extent to which abnormal reward-related neural signals can be observed in chronic, medicated patients with schizophrenia (SZ), however, is not clear. In an fMRI study involving 17 chronic outpatients with SZ and 17 matched controls, we used a monetary incentive delay (MID) task, in which different-colored shapes predicted gains, losses, or neutral outcomes. Subjects needed to respond to a target within a time window in order to receive the indicated gain or avoid the indicated loss. Group differences in blood-oxygen-level-dependent responses to cues and outcomes were assessed through voxel-wise whole-brain analyses and regions-of-interest analyses in the neostriatum and prefrontal cortex (PFC). Significant group by outcome valence interactions were observed in the medial and lateral PFC, lateral temporal cortex, and amygdalae, such that controls, but not patients, showed greater activation for gains, relative to losses. In the striatum, neural activity was modulated by outcome magnitude in both groups. Additionally, we found that ratings of negative symptoms in patients correlated with sensitivity to obtained losses in medial PFC, obtained gains in lateral PFC, and anticipated gains in left ventral striatum. Sensitivity to obtained gains in lateral PFC also correlated with positive symptom scores in patients. Our findings of systematic relationships between clinical symptoms and neural responses to stimuli associated with rewards and punishments offer promise that reward-related neural responses may provide sensitive probes of the effectiveness of treatments for negative symptoms.

Keywords: schizophrenia, dopamine, reinforcement, basal ganglia, ventromedial prefrontal cortex

INTRODUCTION

Deficits in goal-directed behavior are well-documented in schizophrenia (SZ; Kerns et al, 2008; Pantelis et al, 1997), with some authors (Foussias and Remington, 2008) identifying avolition as the core negative symptom of SZ. Factor analyses of negative symptom scales (Blanchard and Cohen, 2006; Sayers et al, 1996) predominantly point to a close association between clinical ratings of avolition and those of anhedonia, suggesting that motivational deficits may be related to a reduced experience of pleasure in SZ. However, accumulated experimental findings (Cohen and Minor, 2010) have cast doubt on the idea that SZ patients actually demonstrate a reduced capacity to experience pleasure.

The fact that SZ patients often report normal experiences of pleasure suggests that motivational deficits in SZ have other sources. One possibility, based on support for a five-factor model of negative symptoms (Andreasen, 1989; Peralta and Cuesta, 1995), is that avolition emerges independently of hedonic experience in SZ. Alternately, aspects of hedonics aside from the experience of rewards (consummatory pleasure) may contribute to motivational deficits in SZ. For example, several groups (Gard et al, 2007; Kring and Neale, 1996) have suggested that the hedonic deficit in SZ involves an inability to anticipate pleasure, rather than a reduced ability to feel pleasure upon reward receipt. A second possibility is that there is a dissociation between reward-related neural activity and the reported subjective experience of reinforcement, leading patients to report an experience of pleasure similar to that of controls, despite aberrant physiological response to rewards. A third possibility is that, even though the majority of studies find that patients and controls do not differ in their self-reports of pleasure experienced when presented with positive stimuli (Cohen and Minor, 2010), a reduced ability to feel pleasure may contribute to motivational deficits in a subset of patients—particularly in those with severe negative symptoms.

Supportive, but inconclusive, evidence exists to support each of these accounts. The hypothesis that reward anticipation in SZ may be abnormal receives its greatest support from behavioral studies (Gard et al, 2007; Heerey and Gold, 2007), whereas neuroimaging results from studies using paradigms similar to the one used in the current study (Juckel et al, 2006b; Schlagenhauf et al, 2008) suggest that treatment with second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) may actually ‘normalize' neural activity in brain regions associated with reward anticipation. The idea that self-reports of normal hedonic experience may not reflect a normal physiological response to rewards has received indirect support from neuroimaging studies showing that neural activity associated with the experience of rewards, and other pleasant stimuli, is abnormal in SZ patients (Paradiso et al, 2003; Walter et al, 2009), even when the psychological experience of evocative stimuli (Takahashi et al, 2004) or reinforcers (Waltz et al, 2009) is reported by patients as normal. Finally, multiple recent studies (Polgar et al, 2008; Waltz et al, 2007) have, in fact, found that deficits on reward-driven learning tasks are most characteristic of SZ patients with severe negative symptoms. These results support the idea that reward-processing abnormalities may be characteristic of a subset of SZ patients, possibly leading to avolition in those patients.

In order to investigate brain activity associated with both outcome anticipation and receipt, we used an adaptation of the monetary incentive delay (MID) task. Using this task, Knutson et al (2001, 2003) produced evidence of a possible dissociation between the brain regions involved in reward anticipation (especially ventral striatum, VS) and consumption (especially medial prefrontal cortex, PFC).

The current study had three specific objectives. First, we wanted to determine whether patients with SZ show abnormal brain responses to monetary outcomes that varied in their valence and magnitude. Second, we sought to determine whether our patients, medicated almost exclusively with SGAs, would show abnormal neural activity associated with reward anticipation. Finally, we wanted to investigate relationships between negative symptoms in SZ and measures of neural responses to outcomes in PFC and outcome-predicting cues in the neostriatum.

Based on the results of previous neuroimaging studies of hedonic experience (Crespo-Facorro et al, 2001; Waltz et al, 2009), we hypothesized that neural responses in patients would show reduced differentiation according to the valence and magnitude of monetary outcomes, particularly in PFC regions. Based on behavioral results from our group (Heerey and Gold, 2007), we hypothesized that patients would show reduced differentiation according to the valence and magnitude of cues predicting monetary outcomes, especially in the VS. Finally, based on previous evidence of relationships between clinical ratings of negative symptoms and reward-related neural responses (Waltz et al, 2009), we hypothesized negative correlations between ratings of negative symptoms and gain-evoked responses in PFC, as well as cue-evoked responses in the striatum.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

In total, 17 patients and 17 demographically matched healthy controls participated in the study (Table 1; Supplementary Materials). All participants were right-handed, as determined by the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (Oldfield, 1971). All patients were on stable antipsychotic medication regimens (no changes for 4 weeks), almost all with SGAs. Participants were instructed to abstain from alcohol for 24 h prior to study visits (verified by a breathalyzer). The groups did not differ in their proportions of habitual cigarette smokers (4/17 NCs and 8/17 SZs; χ2(1)=2.061, p=0.282), and smokers were allowed to smoke prior to MRI scanning (last cigarette approximately 30 min before session), so as to avoid the potential effects of nicotine withdrawal.

Table 1. Subject Descriptive Information.

| SZs (N=17) | NCs (N=17) | p of Group diff. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Demographic information | |||

| Age | 37.8 (9.6) | 37.8 (8.1) | 0.977 |

| Gender | 13 M, 4 F | 12 M, 5 F | 1.000 |

| Race | 12 W, 5 NW | 7 W, 10 NW | 0.166 |

| Subject ed. (yrs.) | 12.7 (2.7) | 14.8 (2.3) | 0.030 |

| Father's ed. (yrs.) | 14.5 (3.8) | 14.2 (2.0) | 0.838 |

| Neuropsychological performance | |||

| WTAR—scaled | 103.8 (16.3) | 107.6 (12.7) | 0.474 |

| WASI—full | 104.9 (15.3) | 115.4 (12.2) | 0.050 |

| RBANS—total | 86.6 (16.5) | 101.8 (11.8) | 0.010 |

| Symptom ratings | |||

| BPRS | 28.9 (8.3) | ||

| SANS | 30.2 (22.7) | ||

| CDS | 0.7 (1.0) | ||

| Antipsychotic drug information | |||

| Haloperidol | 1 Patient | ||

| Olanzapine | 2 Patients | ||

| Risperidone | 7 Patients | ||

| Ziprasidone | 1 Patient | ||

| Clozapine only | 3 Patients | ||

| Clozapine+ | 3 Patients | ||

Abbreviations: SZs, schizophrenia patients; NCs, normal controls; diff., difference; M, male; F, female; W, white; NW, non-white; ed., education; yrs., years; WTAR, Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (Wechsler, 2001); WASI, Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (Wechsler, 1999); RBANS, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (Randolph et al, 1998; Wilk et al, 2005); BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; SANS, Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; CDS, Calgary Depression Scale.

Bold values indicate significant group difference.

Procedures

Outside of the MRI scanner, cognitive function was assessed in all participants using three standard measures (Table 1). In order to quantify the ability of study participants to experience pleasure both physically and in social contexts, we had all subjects complete the Scales for Physical and Social Anhedonia (Chapman et al, 1976). Standard symptom ratings were obtained for all patients using the 25-item Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS; Andreasen, 1984), the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS; Overall and Gorman, 1962), and the Calgary Depression Scale (Addington et al, 1992).

Modified MID paradigm

We used an adaptation of the MID paradigm developed by Knutson et al (2001, 2003) to ascertain the circuitry involved in the anticipation and receipt of monetary losses and gains. The aim of the task is for participants to achieve the best possible outcome on a given trial, and maximize their overall winnings, by responding to a target stimulus item within a dynamically adjusted temporal window. The task was designed to assess neural responses to the anticipation and experience of outcomes, based on cue–outcome associations that had been learned already, as subjects first learned the task in a practice session done in a mock scanner (performing 196 trials).

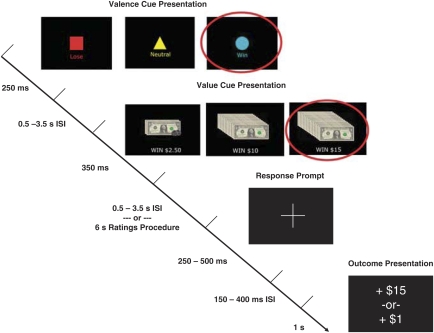

Our implementation of the MID task (see Figure 1, Supplementary Materials) differed from previous versions used, in that it involved compound cues (in which subjects first learned the valence of the outcome, and then, after an ISI of 0.5–3.5 s, the potential magnitude of the outcome), a dynamically adjusted response window, and asymmetric dollar amounts for potential gains and losses (derived from experimental work in decision making and motivation, indicating greater salience of losses in the general population; Breiter et al, 2001; Kahneman and Tversky, 1979). In our task, each of the loss values was equivalent to 60% of the corresponding win value (eg, the largest possible loss was $9 and the largest possible gain was $15). Our adaptation of the task also differed from previous versions used, in that it involved trials on which there were guaranteed gains, trials on which there were guaranteed losses, and neutral trials. If subjects responded to the target outside of the acceptable time window on gain trials, they received $1.25, which was half of the minimum win on successful gain trials; if subjects responded to the target within the acceptable time window on loss trials, they still lost $0.75, which was half of the minimum loss on unsuccessful loss trials. This was done to ensure that subjects never anticipated a neutral outcome on a gain or a loss trial.

Figure 1.

Schematic of a single trial from the experimental task. The subject was first presented with a single valence cue (eg, the ‘win' cue, circled in red) lasting 250 ms. Following an ISI of 0.5–3.5 s, the subject was then presented with a single value cue (eg, the $15 value cue, circled in red; there were three separate values of anticipated gains, three separate values of anticipated losses, and one neutral value) lasting 350 ms. For gain trials, the magnitude cue consisted of scanned images of exact dollar amounts ($2.50–15), whereas for loss trials the magnitude cue consisted of scanned images of exact dollar amounts ($1.50–9) with a large red ‘X' superimposed. Following another ISI of 0.5–3.5 s, a target stimulus (a white cross on a black background) appeared, prompting the participant to respond within the target time window. The target display time and corresponding response window ranged from 250 to 500 ms as a function of the participant's recent response history, and was followed by an ISI of 150–400 ms. Following this ISI, the actual outcome was displayed for 1 s. If a participant responded within the acceptable response window on a gain trial, the total amount of money incremented by the amount in the magnitude cue ($2.50–15.00); if not, the total incremented by $1.25 (half of the smallest gain magnitude cue). If a participant responded within the acceptable response window on a loss trial, the total amount of money decremented by 75 cents (half of the smallest loss magnitude cue); if not, the total decremented by the amount in the magnitude cue ($1.50–9.00).

Data Acquisition

In the MRI scanner, subjects completed 196 total trials (28 trials with each magnitude cue, and thus 84 total gain trials, 84 loss trials, and 28 neutral trials; see Supplementary Materials for details of MRI data acquisition), divided into 4 task runs of 9 min each, and received 10% of the money won in the task as a bonus payout (maximum of $53), in addition to their compensation for participation. In order to characterize participants' arousal levels throughout the task in the MRI scanner, subjects were prompted to enter ratings on a Likert-type scale, ranging from 0 to 8, with 0 representing maximal negative arousal (‘anxious') and 8 representing maximal positive arousal (‘excited'). These ratings were taken following the presentation of the magnitude cue on approximately 1/4 of the trials.

Data Analysis

Steps pertaining to behavioral data analysis and MRI data preprocessing are reported in Supplementary Materials.

Whole-brain analyses of MRI data

Regressors in general linear models (GLMs) of single-subject time series included: valence cues (three levels), magnitude cues (seven levels), responses, and outcomes (nine levels). Regressors were delta-functions time-locked to the onset of the aforementioned events, convolved with a model hemodynamic response function (HRF) and its temporal derivative, and events were identified separately for trials interrupted by the rating procedures and those that were not. The ratings procedure itself, which occurred on 25% of the trials and lasted 6 s, was modeled by a boxcar convolved with an idealized HRF. Further regressors included the motion–correction curves to help account for residual motion effects. For second-level analyses, we analyzed all trials not interrupted by ratings of stimuli (events from those trials were used to model single-subject time series, but beta values corresponding to those regressors were not considered for second-level analyses).

For analyses of neural responses to valence cues, parameter estimates were baseline-corrected by subtracting neutral cue responses from positive and negative cue responses. Then, baseline-corrected voxel-wise parameter estimates for positive and negative cue responses were submitted to a two-way linear mixed effect (LME) analysis, using the AFNI program 3dLME, with factors of group (patients vs controls) and cue valence (gain vs loss; see Supplementary Materials for details). For analyses of neural responses to magnitude cues, voxel-wise parameter estimates were baseline-corrected by subtracting responses to the $0 magnitude cue from all levels of positive and negative magnitude cues (three levels each) and then submitted to separate two-way LME analyses, each with factors of group and cue magnitude.

For second-level analyses of neural responses to outcomes, these trials were grouped into maximized gains (following in-time responses to gain cues; approx. 42 trials), minimal gains (following not-in-time responses to cues; approx. 21 trials), minimized losses (following in-time responses to loss cues; approx. 42 trials), and maximum losses (following not-in-time responses to cues; approx. 21 trials). Single-subject average parameter estimates in each of these conditions were contrasted with blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) responses to neutral outcomes, and submitted to three-way LME analyses, with factors of group (patients vs controls), outcome valence (gain vs loss), and trial success (in-time response vs not-in-time response).

We used a voxel-wise threshold of p<0.001 for F-values generated by the LME models. At this voxel-wise threshold, a Monte Carlo simulation indicated that a minimum cluster size of 11 voxels (297 μl) was required to achieve a significance level of p<0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons over the whole brain.

Analyses of group differences in regions c (ROIs)

Based on evidence that activity in the striatum is modulated by the magnitude of outcome-predicting cues (Knutson et al, 2001, 2003), we performed further analyses using parameter estimates from this area. Because no striatal regions emerged from the whole-brain analyses of cue responses, we selected ROIs in the left and right VS/nucleus accumbens, a priori, using the coordinates emerging from Knutson et al (2001), on which the current study was based. The left VS ROI had a center at (−8, 12, 0) and the right VS ROI had a center at (11, 11, 0). For both ROIs, we generated a spherical mask of radius 5 mm, resulting in a volume of 524 μl (19 voxels).

Based on evidence from previous work that medial (Knutson et al, 2001, 2003) and lateral PFC (Fletcher et al, 2001; Murray et al, 2007; Turner et al, 2004) play essential roles in outcome processing, we performed additional analyses using parameter estimates from these regions. Because areas of medial and lateral PFC emerged from the whole-brain analysis of neural responses to outcomes, we used these regions as sources of parameter estimates. The medial PFC/anterior cingulate ROI had a center at (−1, 41, 5) and had a spatial extent of 513 μl (19 voxels; see Table 2, Figure 3). The lateral PFC ROI had a center at (50, 43, 4) and had a spatial extent of 297 μl/11 voxels.

Table 2. Regions Showing Significant Group × Outcome Valence Interactions.

| Brain region | X | Y | Z | Vol | Vol | Mean F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (R+) | (A+) | (S+) | (μl) | (Vox) | |||

| Frontal cortex | |||||||

| L | Pregen. cingulate/BA 32 | −1 | 41 | 5 | 513 | 19 | 14.4 |

| L | Precentral G./BA 6 | −50 | −3 | 44 | 702 | 26 | 20.5 |

| R | Inf. frontal G./BA 46 | 50 | 43 | 4 | 297 | 11 | 15.7 |

| R | Sup. frontal G./BA 8 | 29 | 43 | 38 | 297 | 11 | 15.6 |

| R | Med. frontal G./BA 6 | 19 | 0 | 50 | 567 | 21 | 14.7 |

| Temporal cortex | |||||||

| R | Mid. temp. G./BA 21 | 52 | −6 | −12 | 1620 | 60 | 18.6 |

| L | Mid. temp. G./BA 21 | −62 | −6 | −10 | 567 | 21 | 16.3 |

| R | PHG/amygdala | 23 | −11 | −13 | 486 | 18 | 14.9 |

| L | PHG/amygdala | −23 | −13 | −15 | 594 | 22 | 13.8 |

| L | Sup. temp. G./BA 41 | −43 | −27 | 5 | 324 | 12 | 15.1 |

| L | Post. temp. Ctx./BA 22 | −62 | −31 | 2 | 702 | 26 | 17.4 |

| L | Post. temp. Ctx./BA 22 | −47 | −43 | 2 | 351 | 13 | 14.9 |

| L | PHG/BA 37 | −23 | −45 | −5 | 1053 | 39 | 15.6 |

| L | Post. temp. Ctx./BA 39 | −51 | −59 | 7 | 486 | 18 | 14.0 |

| Parietal/occipital cortex | |||||||

| L | Fusiform G. | −46 | −46 | −18 | 810 | 30 | 16.8 |

| R | Fusiform G. | 47 | −40 | −19 | 324 | 12 | 15.0 |

| Cerebellum | |||||||

| L | Culmen | −7 | −31 | −17 | 1188 | 44 | 16.1 |

| R | Culmen | 2 | −39 | −8 | 378 | 14 | 19.5 |

| R | Culmen | 33 | −50 | −16 | 297 | 11 | 15.0 |

| L | Cerebellar tonsil | −1 | −54 | −35 | 648 | 24 | 13.2 |

| R | Cerebellar tonsil | 14 | −51 | −39 | 702 | 26 | 14.8 |

Abbreviations: L, left; R, right; pregen., pregenual; BA, Brodmann area; G., gyrus; inf., inferior; sup., superior; med., medial; mid., middle; temp., temporal; PHG, parahippocampal gyrus; post., posterior; Ctx., cortex. Regions illustrated in Figure 3 are italicized.

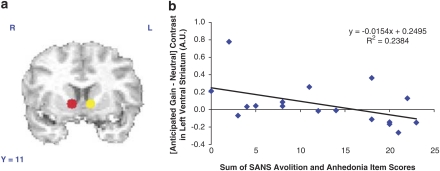

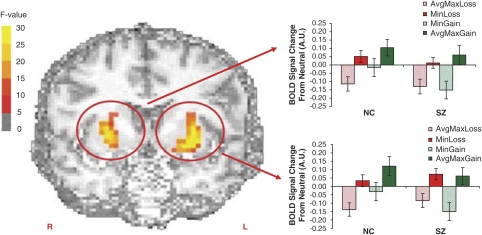

Figure 3.

Brain regions showing significant group × outcome valence interactions. In all areas, controls showed more positive responses to gains than to losses. Patients, by contrast, showed either similar activations to large gains and losses, or reduced responses to gains, relative to losses. Color scale shows voxel-wise F-value, with functional images thresholded at F=11.5 (p=0.001). (a) BOLD responses to negative and positive outcomes by patients (red lines) and controls (blue lines) shown in medial PFC/pregenual ACC (region 1, Talairach coordinates: −1, 41, 5). A similar pattern was observed in the left precentral gyrus (2: −50, −3, −44). Anatomical image cut at x=3, y=−7. (b) BOLD responses by patients and controls shown in the right inferior frontal gyrus (3: 50, 43, 4). A similar pattern was observed in the right superior frontal gyrus (4: 29, 43, 38). Anatomical image cut at y=41. (c) BOLD responses by patients and controls shown in the left amygdala (8: −23, −13, −15). Similar patterns were observed in the right amygdala (7) and middle temporal gyrus/BA 21, bilaterally (5 and 6; see Table 2 for coordinates). Anatomical image cut at y=−11, z=−7.

Correlation analyses

We used Spearman's correlation analyses to assess relationships among clinical ratings of symptoms in SZ patients from the SANS and BPRS, and BOLD responses to cues in a priori ROIs in left and right VS, and to outcomes in functionally defined ROIs in medial and lateral PFC. For the SANS, we computed a total score by summing all 20 item scores (excluding the five global scores), as well as an avolition score, by summing item scores from that subscale. For the BPRS, we computed the total score, by summing all 20 items, as well as scores for four symptom clusters (reality distortion/psychosis, negative symptoms, disorganization, and depression), based on McMahon et al (2002). We also performed analyses of correlations between BOLD responses in ROIs and scores on the Chapman scales for Physical and Social Anhedonia.

RESULTS

Self-Reports/Behavior

Importantly (given that the response window was dynamically adjusted to achieve approximately 2/3 in-time responses for each individual), a t-test revealed no group difference for the overall proportion of in-time responses (mean percentage of in-time responses=63.7% (SD=3.7%) for NCs, and 63.1% (3.7%) for SZs; t(32)=0.498). An ANOVA for target response times for in-time responses, with factors of cue valence and group, revealed a main effect of group (F(1,31)=5.80, p=0.02) and cue valence (F(1,31)=8.43, p<0.01), but no valence × group interaction (F(1,31)=2.06, p>0.10; Supplementary Figure 1A). As expected, patients showed overall slower response times relative to controls (mean RT=364.5 ms for SZs vs 308.2 ms for NCs), and paired t-tests revealed that the entire group of participants was faster to respond to gain cues (mean RT=321.8 ms) than to both loss cues (mean RT=331.6 ms; t(33)=2.865, p=0.007) and neutral cues (mean RT=355.7 ms; t(33)=5.65, p<0.001), as well as faster to respond to loss cues than to neutral cues (t(33)=3.830, p=0.001; Supplementary Figure 1B). Whereas subjects could obtain a better outcome with speeded responses on gain and loss trials, they received no money on neutral trials regardless of their response times, and were thus less motivated to speed their responses on these trials.

An ANOVA for subjective ratings of cues, with factors of cue valence and group, revealed a main effect of cue valence (F(1,31)=4.64, p=0.04), but no main effect of group (F(1,31)=0.04), and no valence × group interaction (F(1,31)=0.04; Supplementary Figure 1C). Paired t-tests revealed that the entire group of participants rated themselves as more anxious (less excited) after loss cues (mean rating=4.11) than after either gain cues (mean rating=4.32; t(33)=2.24, p=0.032) or neutral cues (mean rating=4.38; t(33)=2.52, p=0.017). Subjects did not differ in their ratings of neutral cues and gain cues (t(33)=0.485, p=0.631).

Anhedonia scores

There was a significant between-group difference in social anhedonia scores (t(32)=2.47, p=0.02), with SZ patients showing higher scores (mean=12.6, SD=7.1) than controls (mean=7.4, SD=5.0). Surprisingly, physical anhedonia scores did not differ between groups (t(32)=0.39).

Outcome-Predicting Cues: Whole-Brain Analyses

A two-factor LME model, with factors of group (patients vs controls) and valence cue (gain vs loss), revealed no group × valence interactions, and no main effects of group, although a main effect of valence was observed in the cuneus (BA 18; Talairach coordinates: 9, −78, 9). In this area, the entire sample of subjects showed significantly greater activation to gain cues than loss cues.

A two-factor LME model, with factors of group and gain cue magnitude ($2.50, $10, and $15) revealed a main effect of anticipated gain magnitude in the right cuneus (Talairach coordinates: 6, −78, 24). There were no main effects of group or anticipated outcome magnitude for loss trials, and no group by magnitude interactions.

Outcome-Predicting Cues: Regions-of-Interest Analyses

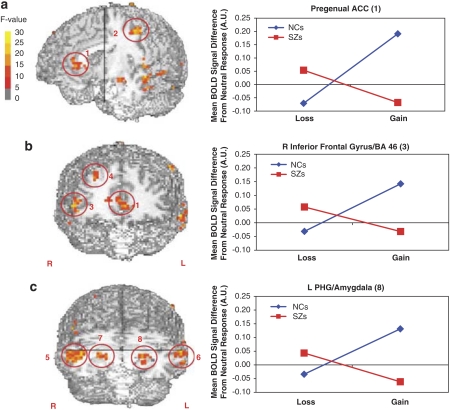

Because we had strong hypotheses regarding the role of the VS/nucleus accumbens in outcome anticipation, we analyzed single-subject parameter estimates from a priori bilateral ROIs in this region (Figure 2a; see Supplementary Data for details). We observed main effects of both cue valence and cue magnitude on activity in the left and right VS in the entire sample (Supplementary Figure 2A and B). Furthermore, the magnitudes of subjects' individual (Gain Cue−Neutral Cue) contrasts in the left VS showed a significant negative correlation with patients' summed avolition and anhedonia subscores from the SANS (Figure 2b; Supplementary Table 1), as well as both their total scores and depression symptom cluster score from the BPRS. That is, neural activity associated with the anticipation of monetary gains was most attenuated in patients with the most severe negative symptoms, and most normal in those with the least severe negative symptoms.

Figure 2.

ROI analyses of reward anticipation responses. (a) ROIs in left (yellow; −8, 12, 0) and right (red; 11, 11, 0) ventral striatum (VS), based on the work of Knutson et al (2001). (b) Scatter plot showing correlation between patients' summed avolition and anhedonia scores from the SANS and activity related to anticipated gains in left VS. Patients with higher ratings of negative symptoms showed more blunted activity related to anticipated gains.

To determine whether correlations between measures of neural responses and measures of symptom severity were attributable to medication dosage, rather than illness, we computed correlations between measures of brain activity and haloperidol-equivalent doses of antipsychotic drugs (computed according to the Expert Consensus Panel for Optimizing Pharmacologic Treatment of Psychotic Disorders, 2003). We observed no significant correlations between haloperidol-equivalent antipsychotic drug dose and any of the measures used in analyses of correlations between negative symptom ratings and neural responses to cues (Supplementary Table 1).

We also investigated correlations between cue-evoked neural responses and self-report measures of trait anhedonia from the Chapman scales, unexpectedly observing a significant positive correlation between social anhedonia scores and gain-cue-evoked activity in SZs in the right VS, reflecting, perhaps, increased sensitivity to reward-related cues in patients with high self-reported anhedonia (Supplementary Table 1).

Levels of Outcome: Whole-Brain Analyses

As shown in Table 2, a three-factor LME model, with factors of group (patients vs controls), outcome valence (gain vs loss), and trial success (in-time response vs not-in-time response) revealed group × valence interactions in multiple brain regions, including VMPFC/pregenual anterior cingulate cortex (ACC; BA 32), lateral PFC (BAs 6, 8, and 46), middle temporal gyrus, and parahippocampal gyrus/amygdala—all brain regions previously implicated in the neural processing of outcomes (Jensen et al, 2007; Nieuwenhuis et al, 2005). As can be seen in Figure 3, whereas controls showed more positive neural responses to gains, relative to losses, in all of these areas, patients showed either similar responses to gains and losses, or greater responses to losses.

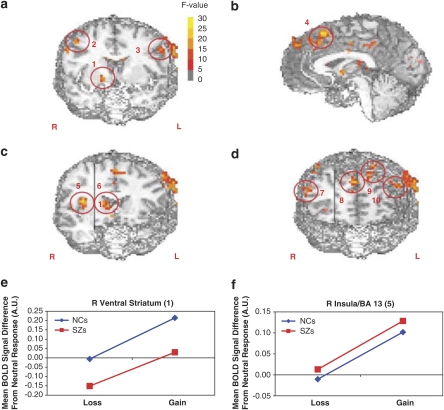

We observed a main effect of outcome valence on the BOLD signal (irrespective of the success of the trial) in the putamen, caudate, insula, and thalamus, on the right, as well as multiple medial and lateral PFC regions (Table 3; Figure 4). Further, we observed a main effect of trial success (which determined the outcome magnitude) in the left and right putamen for the entire sample (Table 4). That is, both groups showed greater activation in the putamen, bilaterally, for in-time responses, when compared with not-in-time responses, regardless of whether the trial involved a gain or a loss (Figure 5). The main effect of trial success/outcome magnitude was not modulated by group; that is, we observed no group × trial success interactions, valence × trial success interactions, or group × trial success × valence interactions.

Table 3. Regions Showing a Significant Main Effect Outcome Valence.

| Brain region | X | Y | Z | Vol | Vol | Mean F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (R+) | (A+) | (S+) | (ìl) | (Vox) | |||

| Basal ganglia/frontal cortex | |||||||

| R | Ventral striatum | 14 | 3 | −5 | 432 | 16 | 17.0 |

| R | Caudate body | 12 | 17 | 7 | 378 | 14 | 14.3 |

| R | Mid. frontal G./BA 8 | 47 | 11 | 38 | 810 | 30 | 15.1 |

| L | Precentral G./BA 6 | −51 | 3 | 34 | 567 | 21 | 15.9 |

| L | Med. frontal G./BA 8 | −6 | 29 | 42 | 3753 | 139 | 16.3 |

| R | Insula/BA 13 | 38 | −1 | 12 | 648 | 24 | 17.9 |

| R | Mid. frontal G./BA 46 | 57 | 24 | 24 | 459 | 17 | 13.7 |

| R | Sup. frontal G./BA 8 | 6 | 52 | 36 | 1215 | 45 | 14.9 |

| L | Sup. frontal G./BA 8 | −13 | 56 | 43 | 378 | 14 | 13.9 |

| L | Sup. frontal G./BA 46 | −46 | 40 | 31 | 297 | 11 | 13.9 |

| Temporal cortex | |||||||

| L | Sup. temp. G. | −64 | −44 | 10 | 324 | 12 | 15.1 |

| R | Sup. temp. G. | 37 | −47 | 18 | 324 | 12 | 16.7 |

| Parietal/occipital cortex | |||||||

| L | Cingulate G. | 0 | −7 | 31 | 405 | 15 | 14.1 |

| L | Cingulate G. | −26 | −14 | 37 | 351 | 13 | 14.7 |

| L | Cingulate G. | −10 | −15 | 29 | 594 | 22 | 17.1 |

| R | Cingulate G. | 1 | −34 | 37 | 540 | 20 | 13.7 |

| L | Postcentral G. | −65 | −24 | 35 | 324 | 12 | 14.8 |

| L | Postcentral G. | −64 | −15 | 25 | 459 | 17 | 16.8 |

| R | Cuneus/BA 18 | 9 | −77 | 19 | 972 | 36 | 15.5 |

| L | Fusiform G. | −36 | −47 | −18 | 351 | 13 | 15.4 |

| L | Inf. parietal lobule/BA 40 | −41 | −44 | 47 | 405 | 15 | 15.5 |

| R | Inf. parietal lobule/BA 40 | 32 | −36 | 43 | 297 | 11 | 14.9 |

| Thalamus | |||||||

| R | VL nucleus | 12 | −13 | 18 | 378 | 14 | 15.1 |

| Cerebellum | |||||||

| R | Culmen | 29 | −35 | −21 | 378 | 14 | 18.4 |

Abbreviations: L, left; R, right; Mid., middle; G., gyrus; BA, Brodmann area; med., medial; sup., superior; temp., temporal; PHG, parahippocampal gyrus; Inf., inferior. Regions illustrated in Figure 4 are italicized.

Figure 4.

Brain regions showing main effects of outcome valence. In all areas, the entire sample of subjects showed more positive responses to gains than to losses. Color scale shows voxel-wise F-value, with functional images thresholded at F=11.5 (p=0.001). (a) 1: right ventral striatum (Talairach coordinates: 14, 3, −5); 2: right middle frontal gyrus/BA 8 (47, 11, 38); 3: left precentral gyrus, BA 6 (−51, 3, 34). Anatomical image cut at y=3. (b) 4: dorsal ACC (−6, 29, 42). Anatomical image cut at x=−5. (c) 5: right insula (38, −1, 12); 6: right caudate (12, 17, 7). Anatomical image cut at y=−3 (right of x=22) and y=19 (left of x=22). (d) Four regions of PFC. 7: right BA 46 (57, 24, 24); 8: right BA 8 (6, 52, 36); 9: left BA 8 (−13, 56, 43); 10: left BA 46 (−46, 40, 31). Anatomical image cut at y=24 (right of x=25) and y=54 (left of x=25). (e) BOLD responses to negative and positive outcomes by patients (red lines) and controls (blue lines) shown in the right ventral striatum (region 1). (f) BOLD responses by patients and controls shown in the right insula (region 5).

Table 4. Regions Showing Significant Main Effects Outcome Magnitude.

| Brain region | X | Y | Z | Vol | Vol | Mean F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

|

(R+) |

(A+) |

(S+) |

(μl) |

(Vox) |

|

| L | Putamen | −25 | 4 | 1 | 6939 | 257 | 20.2 |

| R | Putamen | 22 | 8 | 3 | 5940 | 220 | 19.4 |

Regions illustrated in Figure 5 are italicized.

Figure 5.

BOLD responses in SZ patients and controls in the striatum, bilaterally, to large losses (hatched red; $9, $6, $1.50), successfully minimized losses (solid red; $0.75), minimum gains (hatched green; $1.25), and successfully maximized gains (solid green; $15, $10, $2.50). Both patients and controls showed differentiation between successful and unsuccessful trials in the striatum, bilaterally. Talairach coordinates in Table 4. Color scale shows voxel-wise F-value, with functional images thresholded at F=11.5 (p=0.001).

Thus, while numerous cortical and subcortical structures distinguished, by their responses, positive outcomes from negative ones, only the right ventral putamen showed sensitivity to both the valence and magnitude of outcomes (see Figures 4 and 5).

Levels of Outcome: Region-of-Interest Analyses

Based on recent work from several other groups (Knutson et al, 2001; Murray et al, 2007), we examined relationships between responses to monetary outcomes in medial and lateral aspects of PFC and ratings of clinical symptoms. Clusters in both medial (−1, 41, 5) and lateral (50, 43, 4) aspects of PFC, in fact, showed group × outcome valence interactions, and we performed correlation analyses using these functionally defined ROIs (Supplementary Table 2). In medial PFC/pregenual ACC, we observed significant positive Spearman's correlations between patients' (maximum loss−Neutral) contrasts and total scores from the SANS, as well as patients' summed avolition and anhedonia subscores, such that patients with more severe negative symptoms showed greater deactivations in MPFC to losses (Supplementary Figure 3A). In the right inferior frontal gyrus (BA 46), we observed significant negative Spearman's correlations between patients' (maximum gain−Neutral) contrasts and total scores from the SANS (Supplementary Figure 3B), as well as negative symptom cluster scores from the BPRS. These results support our hypothesis that responses to outcomes may be most aberrant in SZ patients with the most severe negative symptoms.

We also observed strong relationships between outcome-evoked responses in lateral PFC and total scores from the BPRS, as well as cluster scores for positive symptoms from the BPRS (Supplementary Table 2; Supplementary Figure 3C and D). Thus, our results suggest that outcome-evoked responses in lateral PFC are also modulated by positive symptoms, consistent with previous findings (Corlett et al, 2007; Murray et al, 2007).

For outcome-related neural responses, we also sought to determine whether group differences were attributable to the medication, rather than illness, again computing correlations between measures of brain activity and haloperidol-equivalent doses of antipsychotic drugs. No significant correlations were observed between outcome-related neural responses in medial or lateral PFC and standardized APD doses (Supplementary Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we observed that ventromedial PFC, dorsolateral PFC, anterior temporal cortex, and amygdala all show aberrant responses to monetary outcomes in patients with SZ, whereas VS showed similar tracking of the valence and magnitude of outcomes in SZ patients and controls. This observation suggests that brain areas sensitive to rewards and punishments may appropriately signal the occurrence of worse-than-expected outcomes in SZ, although cortical regions involved in interpreting these signals and updating value representations appear to be dysfunctional.

Furthermore, we found that ratings of negative symptoms in SZ correlated with both PFC responses to obtained gains and losses and activity in the left VS associated with the anticipation of monetary gains. These findings provide evidence that negative symptoms in SZ relate closely to neural signals associated with the representation of expected value, as well as the updation of these value representations. Each of these main findings will be discussed in turn.

Neural activity associated with outcome experience

Our finding that SZ patients show abnormal sensitivity to the value of monetary outcomes in PFC is consistent with the results of several recent neuroimaging studies in SZ. Aberrant responses in the medial aspect of PFC have been observed in medicated SZ patients in response to unsuccessful gains (negative prediction errors; Walter et al, 2009), as well aversive pictures from the International Affective Pictures Set (Taylor et al, 2007). Abnormal responses in medial and dorsal aspects of PFC have been exhibited by unmedicated SZ patients (especially those with severe positive symptoms; Corlett et al, 2007; Murray et al, 2007; Schlagenhauf et al, 2009). Based on evidence that medial and ventral aspects of PFC are critical for representing the value of stimuli and actions (Rudebeck et al, 2006; Rushworth, 2008; Schoenbaum and Roesch, 2005), our observation of PFC abnormalities, linked with monetary outcome processing in SZ, suggests that patients' difficulties in reward processing may relate to using outcomes to update associations between actions and anticipated outcomes in PFC regions.

Abnormal responses to positively and negatively valenced stimuli in the amygdala are consistent with previous findings from neuroimaging studies using emotional stimuli with SZ patients (Dowd and Barch, 2009; Gur et al, 2002; Taylor et al, 2005), possibility reflecting a disruption of the amygdala's purported role in the attribution of salience to emotional stimuli (Dowd and Barch, 2009; Zald, 2003). The current finding of aberrant neural responses to outcomes in temporal cortex in SZ are consistent with previous results from Paulus et al (2002). This region has been implicated in decision-making processes under conditions of uncertainty (Paulus et al, 2005). It is plausible that outcome-related activity in this region is aberrant in SZ, because abnormal responses to outcomes likely impact the updating of value representations in the service of future decisions.

It is noteworthy that all of the observed group differences in neural responses were in brain areas showing greater activations for positive than negative outcomes in controls. Although SZ patients showed normal sensitivity to valence in regions such as VS, caudate, dorsomedial PFC, and insula, they showed a lack of sensitivity in VMPFC/pregenual ACC, an area known to be selectively activated for rewards (as opposed to punishments; Dillon et al, 2008; Knutson et al, 2003).

At first blush, our finding that the putamen showed intact sensitivity to both the magnitude and valence of monetary outcomes in SZ patients was somewhat surprising, based on our own previous results (Waltz et al, 2009). There are, however, multiple possible explanations for this apparent discrepancy. One possible explanation for the finding in the current study of intact BG responses to outcome magnitude is the nature of the reinforcer: a blunted response in the striatum to positive outcomes may be specific to primary reinforcers, like juice. However, this explanation is unlikely, based on recent findings from the literature showing blunted BG responses to positive prediction errors in tasks involving monetary rewards (see eg, Koch et al, 2010).

An alternative explanation is that, in the case of the current study, as with most adaptations of MID paradigms, subjects received the best outcome in roughly 2/3 of the trials, as designed (because they made in-time responses), and may have generally been surprised only by non-optimal outcomes (small gains or large losses). That is, the typical MID paradigm may not be ideally suited for evoked responses to positive reward prediction errors (RPEs), because positive RPEs in this task may generally be small. In the previous study, in which we used juice as a primary reinforcer (juice; Waltz et al, 2009), we, in fact, observed that responses to negative prediction errors appeared largely intact in the striatum in patients with SZ, despite evidence that the striatum showed an abnormal neural response to positive prediction errors. Using a monetary prediction error paradigm, Koch and colleagues (2010) also found that, despite observed group difference in responses to positive RPEs in the striatum, responses to negative RPEs did not differ between SZ patients and controls in the VS (though group differences were observed elsewhere).

Other recent neuroimaging studies have provided additional evidence that responses to negative outcomes in the BG may be intact in most patients with SZ. For example, Walter et al (2009) used an MID paradigm similar to ours and found that the BOLD response in left VS showed an even steeper slope, when plotted against reward magnitude, in medicated SZ patients, relative to controls. Simon et al (2009) also found that SZ patients and controls did not differ in their responses to outcomes in VS, although these authors found that a subgroup of the most depressed SZ patients did have blunted neural responses in the VS. Abnormal sensitivity to negative outcomes in the BG may still contribute to psychopathology in unmedicated psychotic patients, as Schlagenhauf and colleagues (2009) have shown.

Behavior and neural activity associated with outcome anticipation

No regions emerged from the whole-brain analysis showing significant group differences in the magnitude of the (anticipated gain—anticipated loss) contrast when comparing controls with patients, although main effects of both cue valence and anticipated gain magnitude were observed in primary visual cortex (BA 18) in the entire sample. These effects may reflect a greater allocation of visual attention to upcoming stimuli, following certain cues.

In our analysis of a priori ROIs, we observed no significant interactions between group and either cue valence or cue magnitude. However, anticipated large gains were associated with greater activation than anticipated small gains in the entire sample in both left and right VS, and the (anticipated gain—anticipated loss) contrast was significantly different from zero in the entire sample in the left VS. Furthermore, we found significant correlations between the magnitude of the (anticipated gain—neutral) contrast and measures of negative symptoms in both the left and right VS, such that reduced differentiation between responses to the gain cue and the loss cue in reward-sensitive brain areas was most characteristic of SZ patients with severe negative symptoms. Thus, the current results provide some additional support for the idea that striatal activity is modulated by the valence and magnitude of anticipated rewards, and they bolster our hypothesis that neural activity associated with the anticipation of rewards and punishments is reflected in observable clinical characteristics of SZ, such as avolition and anhedonia.

Most previous reports of neural responses to cues predictive of monetary outcomes in medicated SZs have described intact responses to cues in the VS in patients (Juckel et al, 2006b; Schlagenhauf et al, 2008; Walter et al, 2009), although studies have found evidence of attenuated MRI responses to reward-predicting cues in the VS in unmedicated SZ patients (Juckel et al, 2006a), as well as those medicated with first-generation antipsychotics (Juckel et al, 2006b). The current result fits especially with the recent findings of Simon et al (2009), who showed that abnormal VS activity associated with reward anticipation may be characteristic of only a subset of medicated SZ patients.

Limitations of the study

The interpretations of our results could be limited by several characteristics of our patient sample. First, the 17 SZ patients included in this study were stable outpatients, with an unusually high overall level of cognitive function (mean estimated IQ was 104.9). Because of this high level of function, we were also interested in potential sources of inter-individual variability. The fact that total scores on the SANS (sum of all items, excepting global scores) in our patients ranged from 2 to 60, and that total scores on the BPRS in our patients ranged from 21 to 58, enabled us to examine relationships between neural responses in patients and symptom severity, leading to findings, described above, that certain abnormalities in reward-related neural responses were most characteristic of SZ patients with either severe negative or severe positive symptoms, whereas other examples of attenuated neural signals were characteristic of the sample as a whole.

Secondly, because all of our subjects were outpatients stably medicated with antipsychotic drugs, we needed to consider the possible impact of dopamine receptor blockade on reward-related neural responses. However, the fact that we observed no significant correlations between haloperidol-equivalent antipsychotic drug dose, and any of the neural measures used in analyses of correlations between negative symptom ratings and neural responses to cues and outcomes, argues against this possibility.

Finally, one aspect of our design may have limited the interpretation of our findings regarding cue-evoked brain activity. Specifically, an effect of the magnitude of reward-predicting cues on striatal activity, even in controls, was evident only in ROI analyses and may not have been as robust as in previous reports (Knutson et al, 2001). The limited number of brain regions showing the effects of cue valence or magnitude may have been due to the fact that we used two cues, separated in time. This may have had the effect of spreading the neural response across time points, increasing variability, and making it more difficult to detect.

General conclusions and future directions

Our findings support emerging ideas describing roles for subregions of the basal ganglia, as well as prefrontal, temporal, and parietal cortices in outcome processing, uncertainty resolution, and motivation (Bush et al, 2002; Montague and Berns, 2002; Paulus et al, 2005; Rushworth, 2008; Weber and Huettel, 2008). In particular, the current results support a role for VMPFC in the representation of outcome valence and point to a disruption of this function in SZ.

Returning to our discussion of possible sources of avolition in SZ, our data suggest that the neural response to outcomes is not normal in patients despite the fact that patients often report experiencing similar emotional states in response to outcomes as healthy controls. This observed dissociation between reported experience and reinforcement-related neural activity is consistent with previous findings in the SZ neuroimaging literature of differences in measures of neural activity accompanying apparently normal performance (Murray et al, 2007; Reiss et al, 2006) and normal subjective experience (Takahashi et al, 2004). It is of note that reward-related neural responses (to cues in the VS and to outcomes in PFC) were most aberrant in patients with the highest ratings for negative symptoms (such as avolition and anhedonia), consistent with previous reports (eg, Simon et al, 2009).

In sum, our findings suggest possible neural substrates for deficits in outcome processing and motivated behavior in SZ, providing evidence of a potential link between clinically assessed negative symptoms and physiological responses to rewards and punishments. Given that reduced goal-directed behavior is nonetheless viewed as a common characteristic of SZ patients (Foussias and Remington, 2008; Kerns et al, 2008), future studies should examine potential sources of avolition in SZ, including factors beyond neural responses to reward experience and anticipation, such as a reduced willingness to expend effort in order to achieve anticipated rewards (Walton et al, 2006). A better understanding of the neural basis of negative symptoms in SZ is an important step in developing more effective treatments for them, and in improving functional outcomes in patients.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible by Grant Nos. 1 K12 RR023250-01, P30 MH068580-01, and 1 R24 MH72647-01A1 from the National Institutes of Mental Health and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Sharon August and Kimberly Warren assisted with screening and neuropsychological assessments. These data were presented, in part, at the 38th annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, in Washington, DC.

James M Gold receives royalty payments from sales of the BACS (Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia) battery (Keefe et al, 2004). He has had consulting relationships with Merck Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, and GlaxoSmithKline. None of these relationships represent a conflict of interest, regarding this work. All other authors declare that, except for income received from their primary employer, no financial support or compensation has been received from any individual or corporate entity over the past 3 years for research or professional service and there are no personal financial holdings that could be perceived as constituting a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Neuropsychopharmacology website (http://www.nature.com/npp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Addington D, Addington J, Maticka-Tyndale E, Joyce J. Reliability and validity of a depression rating scale for schizophrenics. Schizophr Res. 1992;6:201–208. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(92)90003-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC. The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) University of Iowa: Iowa City, IA; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC. The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS): conceptual and theoretical foundations. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;155 (Suppl 7:49–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard JJ, Cohen AS. The structure of negative symptoms within schizophrenia: implications for assessment. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:238–245. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiter HC, Aharon I, Kahneman D, Dale A, Shizgal P. Functional imaging of neural responses to expectancy and experience of monetary gains and losses. Neuron. 2001;30:619–639. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00303-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush G, Vogt BA, Holmes J, Dale AM, Greve D, Jenike MA, et al. Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex: a role in reward-based decision making. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:523–528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012470999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman LJ, Chapman JP, Raulin ML. Scales for physical and social anhedonia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1976;85:374–382. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.85.4.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AS, Minor KS. Emotional experience in patients with schizophrenia revisited: meta-analysis of laboratory studies. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:143–150. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corlett PR, Murray GK, Honey GD, Aitken MR, Shanks DR, Robbins TW, et al. Disrupted prediction-error signal in psychosis: evidence for an associative account of delusions. Brain. 2007;130 (Part 9:2387–2400. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo-Facorro B, Paradiso S, Andreasen NC, O'Leary DS, Watkins GL, Ponto LL, et al. Neural mechanisms of anhedonia in schizophrenia: a PET study of response to unpleasant and pleasant odors. JAMA. 2001;286:427–435. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon DG, Holmes AJ, Jahn AL, Bogdan R, Wald LL, Pizzagalli DA. Dissociation of neural regions associated with anticipatory versus consummatory phases of incentive processing. Psychophysiology. 2008;45:36–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd EC, Barch DM. Anhedonia and emotional experience in schizophrenia: neural and behavioral indicators. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;67:902–911. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PC, Anderson JM, Shanks DR, Honey R, Carpenter TA, Donovan T, et al. Responses of human frontal cortex to surprising events are predicted by formal associative learning theory. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:1043–1048. doi: 10.1038/nn733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foussias G, Remington G. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: avolition and Occam's razor. Schizophr Bull. 2008;36:359–369. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gard DE, Kring AM, Gard MG, Horan WP, Green MF. Anhedonia in schizophrenia: distinctions between anticipatory and consummatory pleasure. Schizophr Res. 2007;93:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur RE, McGrath C, Chan RM, Schroeder L, Turner T, Turetsky BI, et al. An fMRI study of facial emotion processing in patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1992–1999. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heerey EA, Gold JM. Patients with schizophrenia demonstrate dissociation between affective experience and motivated behavior. J Abnorm Psychol. 2007;116:268–278. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen J, Smith AJ, Willeit M, Crawley AP, Mikulis DJ, Vitcu I, et al. Separate brain regions code for salience vs. valence during reward prediction in humans. Hum Brain Mapp. 2007;28:294–302. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juckel G, Schlagenhauf F, Koslowski M, Wüstenberg T, Villringer A, Knutson B, et al. Dysfunction of ventral striatal reward prediction in schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2006a;29:409–416. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juckel G, Schlagenhauf F, Koslowski M, Filonov D, Wüstenberg T, Villringer A, et al. Dysfunction of ventral striatal reward prediction in schizophrenic patients treated with typical, not atypical, neuroleptics. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006b;187:222–228. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0405-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica. 1979;47:263–291. [Google Scholar]

- Keefe RS, Goldberg TE, Harvey PD, Gold JM, Poe MP, Coughenour L. The brief assessment of cognition in schizophrenia: reliability, sensitivity, and comparison with a standard neurocognitive battery. Schizophr Res. 2004;68:283–297. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns JG, Nuechterlein KH, Braver TS, Barch DM. Executive functioning component mechanisms and schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Fong GW, Adams CM, Varner JL, Hommer D. Dissociation of reward anticipation and outcome with event-related fMRI. Neuroreport. 2001;12:3683–3687. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200112040-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B, Fong GW, Adams CM, Varner JL, Hommer D. A region of mesial prefrontal cortex tracks monetarily rewarding outcomes: characterization with rapid event-related fMRI. Neuroimage. 2003;18:263–272. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)00057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch K, Schachtzabel C, Wagner G, Schikora J, Schultz C, Reichenbach JR, et al. Altered activation in association with reward-related trial-and-error learning in patients with schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2010;50:223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kring AM, Neale JM. Do schizophrenic patients show a disjunctive relationship among expressive, experiential, and psychophysiological components of emotion. J Abnorm Psychol. 1996;105:249–257. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon RP, Kelly DL, Kreyenbuhl J, Kirkpatrick B, Love RC, Conley RR. Novel factor-based symptom scores in treatment resistant schizophrenia: implications for clinical trials. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:537–545. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00387-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague PR, Berns GS. Neural economics and the biological substrates of valuation. Neuron. 2002;36:265–284. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00974-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray GK, Corlett PR, Clark L, Pessiglione M, Blackwell AD, Honey G, et al. Substantia nigra/ventral tegmental reward prediction error disruption in psychosis. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;13:267–276. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuis S, Slagter HA, von Geusau NJ, Heslenfeld DJ, Holroyd CB. Knowing good from bad: differential activation of human cortical areas by positive and negative outcomes. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:3161–3168. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overall JE, Gorman DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- Pantelis C, Barnes TR, Nelson HE, Tanner S, Weatherley L, Owen AM, et al. Frontal-striatal cognitive deficits in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Brain. 1997;120 (Part 10:1823–1843. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.10.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradiso S, Andreasen NC, Crespo-Facorro B, O'Leary DS, Watkins GL, Boles Ponto LL, et al. Emotions in unmedicated patients with schizophrenia during evaluation with positron emission tomography. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1775–1783. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus MP, Feinstein JS, Leland D, Simmons AN. Superior temporal gyrus and insula provide response and outcome-dependent information during assessment and action selection in a decision-making situation. Neuroimage. 2005;25:607–615. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus MP, Hozack NE, Zauscher BE, Frank L, Brown GG, McDowell J, et al. Parietal dysfunction is associated with increased outcome-related decision-making in schizophrenia patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:995–1004. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01358-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peralta V, Cuesta MJ. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: a confirmatory factor analysis of competing models. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1450–1457. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.10.1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polgar P, Farkas M, Nagy O, Kelemen O, Réthelyi J, Bitter I, et al. How to find the way out from four rooms? The learning of ‘chaining' associations may shed light on the neuropsychology of the deficit syndrome of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;99:200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randolph C, Tierney MC, Mohr E, Chase TN. The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): preliminary clinical validity. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1998;20:310–319. doi: 10.1076/jcen.20.3.310.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss JP, Campbell DW, Leslie WD, Paulus MP, Ryner LN, Polimeni JO, et al. Deficit in schizophrenia to recruit the striatum in implicit learning: a functional magnetic resonance imaging investigation. Schizophr Res. 2006;87:127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudebeck PH, Walton ME, Smyth AN, Bannerman DM, Rushworth MF. Separate neural pathways process different decision costs. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1161–1168. doi: 10.1038/nn1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushworth MFS. Intention, choice, and the medial frontal cortex. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1124:181–207. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayers SL, Curran PJ, Mueser KT. Factor structure and construct validity of the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms. Psychol Assess. 1996;8:269–280. [Google Scholar]

- Schlagenhauf F, Juckel G, Koslowski M, Kahnt T, Knutson B, Dembler T, et al. Reward system activation in schizophrenic patients switched from typical neuroleptics to olanzapine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;196:673–684. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlagenhauf F, Sterzer P, Schmack K, Ballmaier M, Rapp M, Wrase J, et al. Reward feedback alterations in unmedicated schizophrenia patients: relevance for delusions. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:1032–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenbaum G, Roesch M. Orbitofrontal cortex, associative learning, and expectancies. Neuron. 2005;47:633–636. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon JJ, Biller A, Walther S, Roesch-Ely D, Stippich C, Weisbrod M, et al. Neural correlates of reward processing in schizophrenia - relationship to apathy and depression. Schizophr Res. 2009;118:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Koeda M, Oda K, Matsuda T, Matsushima E, Matsuura M, et al. An fMRI study of differential neural response to affective pictures in schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2004;22:1247–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SF, Phan KL, Britton JC, Liberzon I. Neural response to emotional salience in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:984–995. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SF, Welsh RC, Chen AC, Velander AJ, Liberzon I. Medial frontal hyperactivity in reality distortion. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:1171–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner DC, Aitken MR, Shanks DR, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW, Schwarzbauer C, et al. The role of the lateral frontal cortex in causal associative learning: exploring preventative and super-learning. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14:872–880. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter H, Kammerer H, Frasch K, Spitzer M, Abler B. Altered reward functions in patients on atypical antipsychotic medication in line with the revised dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;206:121–132. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1586-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton ME, Kennerley SW, Bannerman DM, Phillips PE, Rushworth MF. Weighing up the benefits of work: behavioral and neural analyses of effort-related decision making. Neural Netw. 2006;19:1302–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltz JA, Frank MJ, Robinson BM, Gold JM. Selective reinforcement learning deficits in schizophrenia support predictions from computational models of striatal-cortical dysfunction. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:756–764. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltz JA, Schweitzer JB, Gold JM, Kurup PK, Ross TJ, Salmeron BJ, et al. Patients with schizophrenia have a reduced neural response to both unpredictable and predictable primary reinforcers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1567–1577. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber BJ, Huettel SA. The neural substrates of probabilistic and intertemporal decision making. Brain Res. 2008;1234:104–115. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR) The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wilk CM, Gold JM, McMahon RP, Humber K, Iannone VN, Buchanan RW. No, it is not possible to be schizophrenic yet neuropsychologically normal. Neuropsychology. 2005;19:778–786. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.19.6.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zald DH. The human amygdala and the emotional evaluation of sensory stimuli. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2003;41:88–123. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.