Abstract

Unlike the growth factor-dependence of normal cells, cancer cells can maintain growth factor-independent glycolysis and survival through expression of oncogenic kinases, such as BCR-Abl. While targeted kinase inhibition can promote cancer cell death, therapeutic resistance develops frequently and further mechanistic understanding is needed. Cell metabolism may be central to this cell death pathway, as we have shown that growth factor deprivation leads to decreased glycolysis that promotes apoptosis via p53 activation and induction of the pro-apoptotic protein Puma. Here, we extend these findings to demonstrate that elevated glucose metabolism, characteristic of cancer cells, can suppress PKCδ-dependent p53 activation to maintain cell survival after growth factor withdrawal. In contrast, DNA damage-induced p53 activation was PKCδ-independent and was not metabolically sensitive. Both stresses required p53 serine 18 phosphorylation for maximal activity but led to unique patterns of p53 target gene expression, demonstrating distinct activation and response pathways for p53 that were differentially regulated by metabolism. Consistent with oncogenic kinases acting to replace growth factors, treatment of BCR-Abl-expressing cells with the kinase inhibitor imatinib led to reduced metabolism and p53- and Puma-dependent cell death. Accordingly, maintenance of glucose uptake inhibited p53 activation and promoted imatinib resistance. Furthermore, inhibition of glycolysis enhanced imatinib sensitivity in BCR-Abl-expressing cells with wild type p53 but had little effect on p53 null cells. These data demonstrate that distinct pathways regulate p53 after DNA damage and metabolic stress and that inhibiting glucose metabolism may enhance the efficacy of and overcome resistance to targeted molecular cancer therapies.

Keywords: Glucose, metabolism, p53, cytokine, imatinib

Introduction

Developing hematopoietic cells normally require input from growth factor signaling pathways to support basal glucose metabolism for cell survival and proliferation(1, 2). In contrast, cancer cells often become independent of cell extrinsic growth factors and gain autonomous control over metabolism and survival(3). In particular, cancer cells adopt the metabolic program of aerobic glycolysis(4) that is characterized by increased glucose uptake, glycolytic flux, and lactate production, and is reminiscent of growth factor-stimulated cells(5). It is now clear that aerobic glycolysis can be directly initiated by growth factor signals and oncogenes known to cause hematologic malignancies, including Notch(6), Akt(7, 8), and BCR-Abl(9, 10). The extent to which this metabolic phenotype impacts cell survival or oncogenesis, however, remains unclear.

Cancer cells can become growth factor-independent through the activation of pathways that mimic growth factor signaling and inhibition of these pathways has proven an effective way to eliminate cancer cells. The BCR-Abl fusion protein, for example, can maintain glucose uptake(9) and cell survival(11). The tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib, which is widely used to treat BCR-Abl-positive leukemias, blocks the survival signal in these cells, causing decreased glycolysis and cell death(10). Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are also used to treat a number of solid cancers, including breast, colorectal and lung cancer, but development of resistance to these small molecule inhibitors represents an obstacle to long-term remission(12–14). Further insight into how loss of growth signals leads to cell death may provide direction to improve these important clinical tools.

It is now clear that decreased metabolism may initiate cell death upon inhibition of growth signals. The AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and the lipid-sensitive Protein Kinase C (PKC) family of proteins are each sensitive to metabolic cues and may affect apoptosis(15, 16). Additionally, cellular metabolism can directly regulate the Bcl-2 family proteins, as loss of glucose uptake upon growth factor withdrawal(17) leads to degradation of the pro-survival Bcl-2 protein Mcl-1(16) and induction of the pro-apoptotic BH3-only protein Puma(17). Inhibition of glucose metabolism can lead to apoptosis, however, only when pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins Bax(5, 18) and Bim or Puma are present(17), indicating that metabolic pathways that influence cell death must converge on Bcl-2 family proteins.

We recently demonstrated that aerobic glycolysis can prevent p53 activation and Puma induction in growth factor withdrawal(17). We sought here to determine how p53 is metabolically regulated and how this pathway may contribute to imatinib-induced death of BCR-Abl expressing cells. While p53 was required for Puma induction and cell death in response to growth factor withdrawal and DNA damage, elevated glucose metabolism attenuated p53 activation and Puma induction only after cytokine withdrawal. Importantly, imatinib decreased glucose metabolism, but maintenance of aerobic glycolysis attenuated p53 activation and cell death whereas inhibition of glycolysis enhanced imatinib sensitivity via p53. Thus, glucose metabolism can itself suppress a specific pathway of p53 activation and may contribute to oncogenesis and sensitivity to targeted therapies.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Control, Glut1/HK1, and Bcl-xL-expressing FL5.12 cells were cultured as described in RPMI 1640 media (Mediatech) with 10% FetalClone III serum (Thermo Scientific) and 0.5 ng/ml recombinant murine IL-3 (eBioscience)(17). K562 cell were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gemini Bio-Products), 2 mM glutamine, 10 mM Hepes, and 55 nM 2-ME. Nalm-1 cells (ATCC) were cultured in RPMI 1640 with 15% FBS. Murine T cells were isolated via negative selection (StemSep) and cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS with 10 ng/mL recombinant murine IL-2 (eBioscience). T cells were activated on 5 μg/ml anti-CD3ε and anti-CD28 antibody-coated plates (BD Pharmingen) for 48 hours, followed by 24 hours in 10 ng/mL IL-2. For growth factor withdrawal, cells were washed three times with PBS and cultured in the presence or absence of IL-3 or IL-2. Some cells were resuspended in media containing 0.4 μM etoposide (Sigma), 10 μM Compound C (EMD Biosciences), 10 μM Rottlerin (Calbiochem), 1 μM imatinib (LC Laboratories), 5 mM 2-Deoxyglucose (Sigma), or an equal volume of vehicle control.

Immunoblots

Samples were prepared as previously described(17). Primary antibodies were: Puma (Cell Signaling), p53 1C12 (Cell Signaling), Actin (Sigma), Bim (BD Pharmingen), phospho-p53 Ser15 (Cell Signaling), PKCδ (BD Pharmingen), HA (Roche), Lamin B2 (Invitrogen), GAPDH 6C5 (Santa Cruz), and C-terminal acetylated p53 (generously provided by Dr. Tso-Pang Yao, Duke University). Secondary antibodies were anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-labeled (Cell Signaling), anti-rat horseradish peroxidase-labeled (BD Pharmingen), and anti-mouse fluorescent-labeled (Licor) antibodies. Blots were imaged using Supersignal West Pico or Femto Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific) or the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LiCor). Images were uniformly contrasted and some were separated digitally for ease of viewing (indicated by white spaces).

Transfection and plasmids

Transient transfections were performed via nucleofection (Amaxa, Kit V, Lonza), and shRNA plasmids were constructed as previously described(17). p53, Puma and Bim were knocked down using previously reported shRNA sequences(17). The shRNA sequence for PKCδ was GAAGATGAAGGAGGCACTCAGCCTCGAGCCTGAGTGCCTCCTTCATCTTC. HA-tagged, wild type human pcDNA3.1-p53 was expressed for acetylation studies.

Cell viability analysis

Cell viability was assessed via propidium iodide (PI) exclusion on a FACScan flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) using FlowJo software (TreeStar), as described(17). Means +/− standard deviations are shown. Data are representative of three or more independent experiments.

Glycolysis assays

Rates of glycolysis were measured as previously described(5), and means plus standard deviations are shown.

Luciferase assays

Cells were cultured in the presence or absence of IL-3 or etoposide for eight hours or imatinib for ten hours. Luciferase activity was measured using a Dual Luciferase Assay kit (Promega), following the manufacturer’s instructions as previously described(17). Values are means plus standard deviations of triplicate samples. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

A p53 signaling RT-PCR SuperArray (SA Biosciences) was performed according to the manufacturers instructions. qRT-PCR was performed as previously described for Puma and beta-2-microglobulin(17). Additional primer sequences were: Gadd45: ATTTCACCCTCATCCGTGCGTTCT, ATGAATGTGGGTTCGTCACCAGCA; Mdm2: GTTGTTAAAGTCCGTTGGAGCGCA, CAATGTGCTGCTGCTTCTCGTCAT; Bax: CCGGCGAATTGGAGATGAACT, CCAGCCCATGATGGTTCTGAT; p21: AATCCTGGTGATGTCCGACCTGTT, GTGACGAAGTCAAAGTTCCACCGT; Zmat3: ATGACTACTGTAAGCTGTGCGA, GGCCACCATCTTAAATTCACTCC. Values are means plus standard deviations of three independent experiments.

Cell Fractionation

Cell fractionations were performed as previously described(19).

Results

p53 is required for efficient cell death after both cytokine withdrawal and DNA damage in activated T lymphocytes

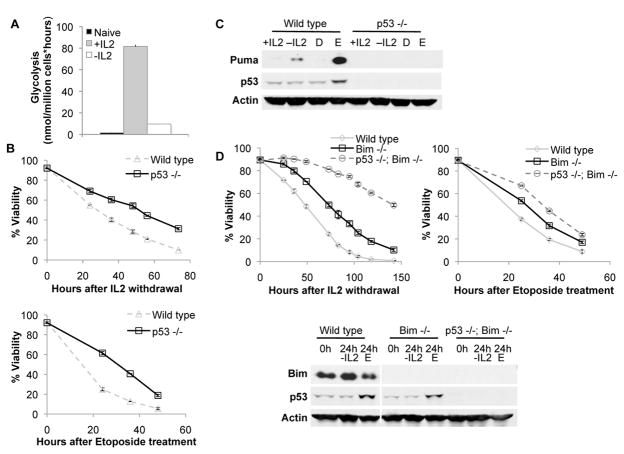

Inhibition of growth signals leads to decreased glucose metabolism and apoptosis via p53 activation and induction of Puma and Bim(2, 17, 20). It remained unclear how decreased glycolysis stimulated p53 and if this regulatory pathway was common to other p53-responsive stresses. We initially examined activated primary T lymphocytes, which undergo a dramatic increase in glycolytic metabolism upon activation that is characteristic of aerobic glycolysis and requires interleukin-2 (IL-2) (Figure 1A). Purified p53+/+ or p53−/− T cells were activated and cultured in IL-2, and cell death was observed after IL-2 withdrawal or treatment with the DNA-damaging chemotherapeutic agent etoposide (Figure 1B). In both cases, p53−/− T cells exhibited a persistent survival advantage over control cells, demonstrating a contribution by p53 to these cell death pathways.

Figure 1. p53 is required for Puma induction and cell death after growth factor withdrawal and etoposide treatment in activated T lymphocytes.

A, Glycolysis was measured in resting primary splenic T cells and in activated T cells cultured in the presence or absence of IL-2 for an additional 12 hours. B, C, T cells were isolated from wild type and p53−/− mice, activated, and cultured in the presence or absence of IL-2 or etoposide (D=DMSO control; E=Etoposide). (B) Cell viability was measured over time, and (C) Puma and p53 levels were analyzed by immunoblot after 12 hours. D, T cells from wild type, Bim−/− or Bim−/− p53−/− mice were activated and withdrawn from IL-2 or treated with etoposide as above. Viability was measured over time and levels of Bim and p53 were analyzed after 24 hours.

p53 likely regulated cell death by control of pro-apoptotic proteins, and activated wild type T cells upregulated Puma expression upon both IL-2 withdrawal and etoposide treatment (Figure 1C). In contrast, p53-deficient T cells failed to upregulate Puma in response to either IL-2 withdrawal or etoposide treatment. Bim has also been implicated in T cell apoptosis(20), and p53 may have regulated cell death through modification of Bim. To determine if p53 might also regulate cell death in the absence of Bim, activated Bim−/− and Bim−/− p53−/− T cells were analyzed (Figure 1D). Importantly, p53 deficiency provided protection from growth factor withdrawal and DNA damage, regardless of Bim expression, and Bim−/− p53−/− T cells were highly resistant to apoptosis upon IL-2 withdrawal. Thus, p53 is critical to the induction of apoptosis following growth factor deprivation or DNA damage, independent of Bim.

Increased glucose metabolism attenuates p53-dependent Puma induction and cell death after growth factor withdrawal but not DNA damage

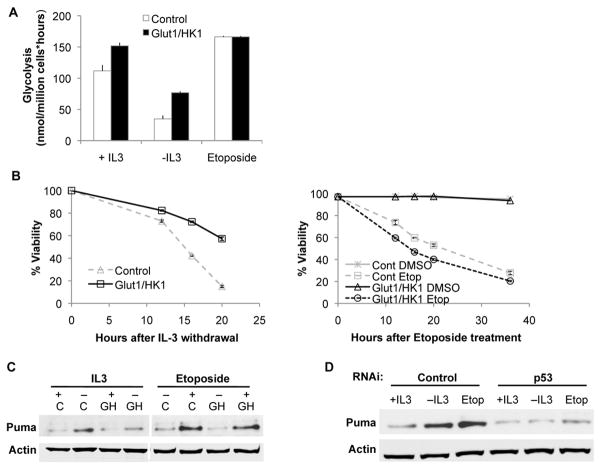

The IL-3 dependent and non-transformed hematopoietic precursor cell line FL5.12 also undergoes apoptosis following growth factor deprivation(17) or DNA damage(21). Importantly, these cells retain wild type p53(17), yet can be readily transformed to cause leukemias in vivo(22), and thus offer a model to examine p53 regulation. To address the effect of glucose metabolism on p53 directly, we established cells that stably co-express the glucose transporter Glut1 and hexokinase (HK1)(18). Elevated HK1 activity and exogenous Glut1, which localized largely to the cell surface even after IL-3 withdrawal(18), drove glucose uptake and metabolism even in the absence of growth factor (Figure 2A). DNA damage, however, did not reduce glucose metabolism and glycolytic rates were modestly elevated in control and Glut1/HK1-expressing cells. Importantly, maintenance of glucose metabolism delayed cell death upon growth factor withdrawal (Figure 2B) (16), but did not provide protection against DNA damage by etoposide (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Maintenance of glucose metabolism suppresses Puma induction and cell death after growth factor withdrawal but not after DNA damage.

A,B,C, Control cells and cells with stable expression of Glut1 and HK1 were grown in the presence of IL-3 or were withdrawn from IL-3 or treated with etoposide and (A) glycolysis was assessed after 8 hours, (B) cell viability was measured over time, and (C) Puma induction was assessed after 10 hours (C=Control; GH=Glut1/HK1). D, Control cells were transfected with control or p53 shRNA, and Puma induction was measured after 10 hours of IL-3 withdrawal or etoposide treatment.

Consistent with selective protection from apoptosis, Puma induction in Glut1/HK1 cells was largely suppressed upon growth factor withdrawal, but not following DNA damage (Figure 2C). This was mediated by p53, as shRNA knockdown of p53 suppressed Puma induction (Figure 2D) and attenuated cell death after both IL-3 deprivation and etoposide treatment (Supplementary Figure 1). These data support a role for p53 to promote apoptosis after multiple cell stresses and demonstrate selective metabolic regulation of p53 and Puma induction after cytokine withdrawal.

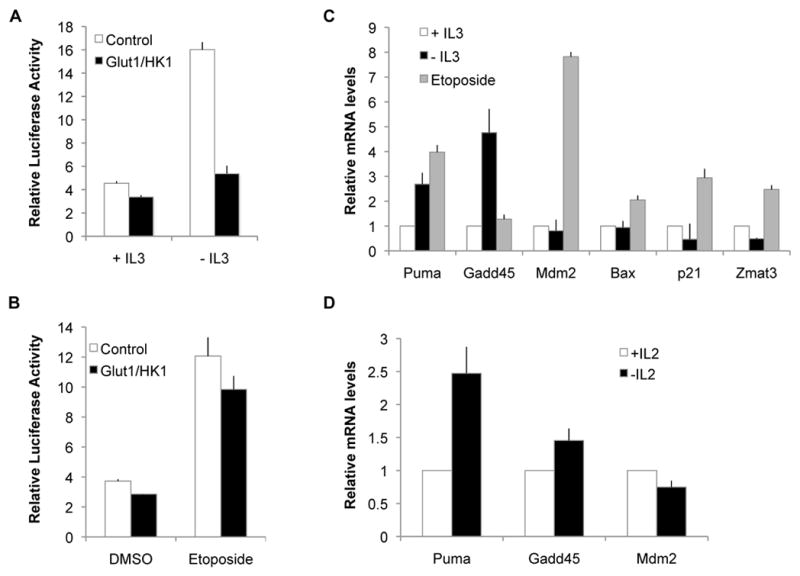

Glucose metabolism selectively regulates p53 transcriptional activity after cytokine withdrawal but not after DNA damage

The differential patterns of Puma induction shown above suggested distinct modes of p53 transcriptional regulation. Cells were therefore transfected with a p53 luciferase reporter construct to assess p53-dependent transcription. After cytokine withdrawal, p53 activity increased in control cells, but this was prevented by maintenance of glycolysis in Glut1/HK1-expressing cells (Figure 3A). In contrast, p53 transcriptional activity increased equivalently in both control and Glut1/HK1 cells after DNA damage (Figure 3B). p53 can upregulate different target genes in response to various stresses(23), and differential regulation might activate p53 to induce distinct sets of target genes. To examine this possibility, control cells were cultured in the presence or absence of IL-3 or the presence of etoposide, and mRNA levels for a panel of p53 target genes were analyzed using a quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR) array focused on p53 signaling pathways. Candidate genes were subsequently validated using qRT-PCR (Figure 3C). Treatment with etoposide led to increased levels of the p53 targets Puma, Mdm2, Bax, p21 and Zmat3, while IL-3 deprivation led to upregulation of Puma and Gadd45. Similarly, activated T cells deprived IL-2 also had increased Puma and Gadd45 mRNA levels, but unchanged or decreased levels of Mdm2 mRNA (Figure 3D). Thus, p53 activation pathways are differentially sensitive to metabolic status and can induce distinct sets of target genes.

Figure 3. Activation of p53 is selectively inhibited by glucose metabolism after cytokine withdrawal.

A,B, p53 transcriptional activity was measured in control and Glut1/HK1 cells using a luciferase reporter construct driven by p53 binding elements in cells grown ± IL-3 (A) or in the presence of DMSO or etoposide (B). C,D, Induction of multiple p53 target genes was measured by RT-PCR in (C) control cells grown in the presence of IL-3 or withdrawn from IL-3 or treated with etoposide for 10 hours or (D) activated primary T cells cultured in the presence or absence of IL-2 for 12 hours.

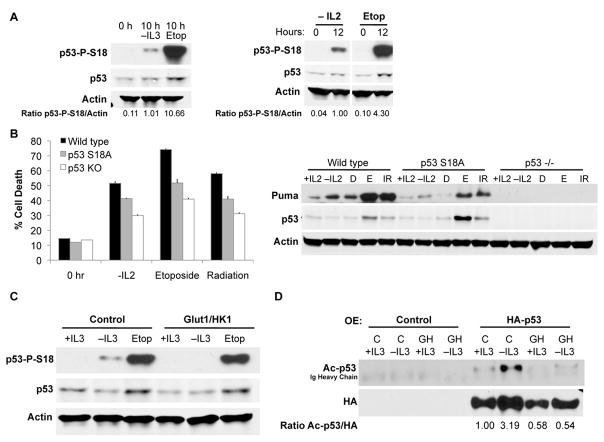

Glucose metabolism regulates post-translational modification of p53 after cytokine withdrawal but not DNA damage

To allow differential responses to growth factor withdrawal or DNA damage, p53 may be subject to distinct patterns of modification. In the DNA damage response pathway, phosphorylation dissociates p53 from the ubiquitin ligase Mdm2 to allow p53 stabilization. Despite increased p53 transcriptional activity, however, no increases in total p53 protein were observed in either FL5.12 cells or primary T cells after cytokine withdrawal (Supplementary Figure 2). As expected, p53 was stabilized in both cell types upon etoposide treatment (Supplementary Figure 2). We next examined whether cytokine withdrawal also induced p53 phosphorylation. Indeed, growth factor withdrawal led to phosphorylation of p53 on serine 18 (mSer18, corresponding to human Ser15), albeit to a lower level than that induced by DNA damage (Figure 4A). Similarly, p53 was phosphorylated on mSer18 after both cytokine withdrawal and DNA damage in activated primary T cells (Figure 4A). Phosphorylation was seen specifically at this site, but not at mSer23 (hSer20) or mSer389 (hS392), after cytokine withdrawal (Supplementary Figure 3). This was distinct from the pattern of p53 modification induced by DNA damage, where phosphorylation at these additional sites was readily detected.

Figure 4. Post-translational modification of p53 after cytokine withdrawal is suppressed by glucose metabolism.

A, Levels of mSer18 p53 phosphorylation were assessed via immunoblot in cells withdrawn from IL-3 or treated with etoposide for 10 hours or wild type primary T cells activated and cultured without IL-2 or with etoposide for 12 hours. B, T cells from p53+/+, p53 S18A/S18A, or p53−/− mice were activated and withdrawn from IL-2 or treated with etoposide or 8 Gy gamma irradiation for analysis of cell survival and immunoblot after one day. (C) Control and Glut1/HK1 cells cultured in the presence or absence of IL-3 or the presence of etoposide for 10 hours were examined for mSer18 p53 phosphorylation. D, Control and Glut1/HK1 cells were transfected with HA-tagged human p53 and cultured in the presence or absence or IL-3 for 10 hrs, and HA-p53 was immunoprecipitated and probed for acetylation.

To directly address the role of p53 S18 phosphorylation, T lymphocytes were examined from p53 S18A knock-in mice, in which S18 is mutated to alanine(24). Activated p53 S18A T cells were partially resistant to cell death after cytokine withdrawal or DNA damage induced by etoposide or gamma irradiation (Figure 4B). Importantly, Puma induction was also attenuated in activated S18A T cells after both cytokine withdrawal and DNA damage (Figure 4B). These data demonstrate that phosphorylation of p53 at Ser18 is required for maximal activation of p53 and Puma induction.

Cells that maintained glucose uptake and metabolism may have suppressed p53 transcriptional activity through inhibition of p53 modification. To examine this possibility, control and Glut1/HK1 cells were cultured in the presence or absence of IL-3 or the presence of etoposide, and phosphorylation at mSer18 of p53 was examined. While control cells showed p53 phosphorylation after IL-3 withdrawal, Glut1/HK1 expression strongly suppressed this phosphorylation (Figure 4C). In contrast, both control and Glut1/HK1 cells showed strong phosphorylation on mSer18 after etoposide treatment.

The intermediate phenotype of p53 S18A T cells suggested additional metabolically regulated mechanisms also contribute to p53 activation. C-terminal acetylation can also enhance p53 transcriptional activity(25). To examine p53 acetylation, cells were transfected with HA-tagged human p53 and cultured in the presence or absence of IL-3. HA-p53 was then immunoprecipitated and probed with anti-sera recognizing pan-C terminal-acetylated human p53(26). Control cells showed an increase in p53 C-terminal acetylation after IL-3 deprivation, consistent with p53 activation. However, Glut/HK1-expressing cells showed no increase in p53 acetylation (Figure 4D). Although the hierarchy of these modifications in regulating p53 remains unclear, these results demonstrate that p53 is phosphorylated and acetylated after cytokine withdrawal, and these modifications are prevented by aerobic glycolysis.

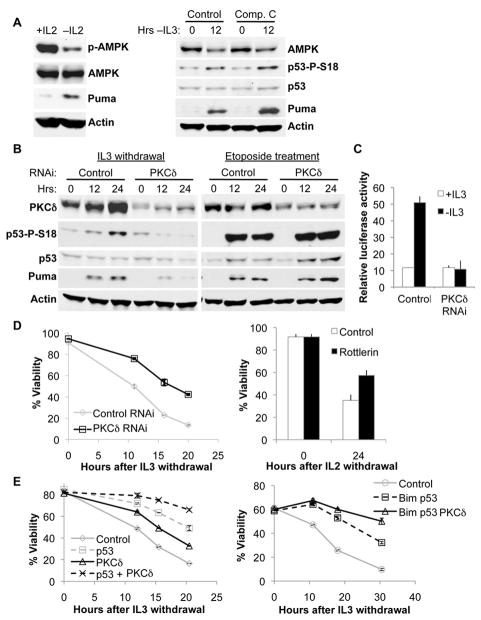

Protein Kinase C delta is required for p53 phosphorylation after cytokine withdrawal

Selective regulation of p53 modification suggested that nutrient-sensitive kinases mediate p53 activation when cells are deprived growth signals through a pathway distinct from the DNA damage response of ATM and ATR. Of likely candidates, AMPK has been characterized as a glucose-sensitive kinase and can phosphorylate p53 at mSer18 in the context of glucose limitation(27). However, we failed to detect an increase in activating phosphorylation of AMPK after cytokine withdrawal (Figure 5A). Furthermore, pharmacologic inhibition of AMPK with Compound C had no effect on p53 phosphorylation or Puma induction upon growth factor withdrawal (Figure 5A). These findings suggested that an AMPK-independent pathway may sense altered metabolism in growth factor deprivation.

Figure 5. PKCδ is required for cytokine withdrawal-induced p53 phosphorylation.

A, Primary T lymphocytes were activated and withdrawn from IL-2 for 12 hrs (left panel), and FL5.12 cells expressing Bcl-xL were treated with 10 μM Compound C or vehicle control and withdrawn from IL-3 (right panel). B-E, FL5.12 cells were transfected with control, PKCδ, p53 or Bim shRNA, as indicated. B, FL5.12 cells expressing Bcl-xL were withdrawn from IL-3 or treated with etoposide. Bcl-xL-expressing cells were used to prevent loss of cell viability over the treatment time course. C. FL5.12 cells were transfected with a p53 transcriptional activity luciferase reporter and cultured ± IL-3 for 8 hours. D, E, Control and CTLL-2 cells were withdrawn from IL-3 and IL-2, respectively and viability was measured over time.

Members of the PKC family can also respond to changes in glucose metabolism (15, 16), and recent work has implicated PKCδ in cytokine withdrawal-induced cell death(28). Indeed, cells transiently transfected with PKCδ shRNA demonstrated markedly reduced p53 phosphorylation and Puma induction (Figure 5B) and failed to increase p53 transcriptional activity (Figure 5C) upon growth factor withdrawal. In contrast, PKCδ was dispensable for p53 phosphorylation and Puma induction after DNA damage (Figure 5B). PKCδ may have promoted cell death indirectly by suppressing glucose metabolism upon cytokine withdrawal, which Glut1/HK1 cells could overcome. However, knock-down of PKCδ did not significantly effect glycolytic rate (Supplementary Figure 4). Importantly, PKCδ contributed to cell death, as PKCδ shRNA protected FL5.12 cells against IL-3 withdrawal, and the PKCδ inhibitor Rottlerin attenuated the death of IL-2-dependent CTLL-2 T cells after cytokine deprivation (Figure 5D).

PKCδ may have phosphorylated p53 directly(29, 30), or through indirect regulation of metabolic stress pathways. However, we were unable to detect direct phosphorylation in vitro, and fractionation experiments demonstrated that PKCδ and p53 resided primarily in different cellular compartments (Supplementary Figure 5). Furthermore, PKCδ deficiency provided further protection beyond that observed with knock-down of p53 alone or in combination with Bim knock-down (Figure 5E, Supplementary Figure 6). This suggested that PKCδ contributed to cell death after cytokine withdrawal through additional, p53-independent mechanisms. Thus, PKCδ is essential, possibly as a nutrient sensor and signal initiator, to promote cell death after growth factor withdrawal through both p53-dependent and p53-independent pathways.

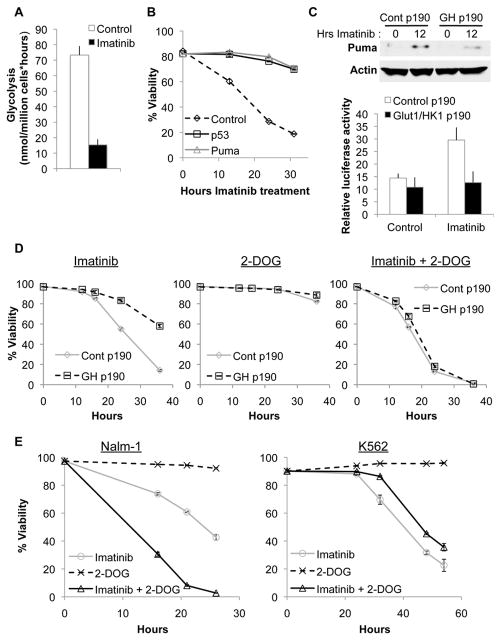

Increased glucose metabolism confers resistance to imatinib

Oncogenic kinases can render cells growth factor-independent(11) and expression of the p190 isoform of BCR-Abl in FL5.12 cells allowed cells to survive and proliferate in the absence of IL-3 (Supplementary Figure 7). Like growth factor withdrawal, the BCR-Abl kinase inhibitor imatinib decreased glycolysis (Figure 6A) and induced apoptosis in control cells expressing p190 (Figure 6B). Similar to growth factor withdrawal, shRNA-mediated knockdown of p53 or Puma (Supplementary Figure 8) dramatically reduced cell death after imatinib treatment (Figure 6B). In addition, while control p190 cells induced Puma in response to imatinib, Glut1/HK1 p190 cells suppressed Puma upregulation and showed no increase in p53 transcriptional activity after imatinib treatment (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. Glucose metabolism promotes imatinib resistance.

A,B, Control cells stably expressing BCR-Abl cultured without IL-3 were analyzed. A, Glycolysis was measured after 10 hours imatinib treatment. B, Cells were transfected with control, p53, or Puma shRNA and treated with imatinib, and viability was assessed over time. C,D, Control p190 and Glut1/HK1 p190 cells cultured without IL-3 were (C) treated with imatinib for 12 hours and Puma induction was measured via immunoblot (top panel), transfected with a p53 transcriptional activity luciferase reporter and treated with imatinib for 10 hours(bottom panel), or (D) treated with imatinib, 2-deoxyglucose, or both in combination, and viability was assessed over time. E, Nalm-1 and K562 cells were treated with imatinib, 2-deoxyglucose, or both, and viability was assessed over time.

These data suggested that imatinib utilized a metabolically-sensitive apoptotic mechanism similar to withdrawal from extrinsic growth factors. Consistent with this notion, Glut1/HK1 p190 cells were protected from imatinib-induced cell death (Figure 6D). To examine whether this resistance was dependent on increased glycolysis, control and Glut1/HK1 cells were treated with imatinib together with the glycolysis inhibitor 2-deoxyglucose (2-DOG). While 2-DOG treatment at this concentration alone had little effect on cell viability in either cell type, combination treatment with imatinib and 2-DOG increased cell death in both cell types and eliminated the resistance to imatinib seen in Glut1/HK1 p190 cells (Figure 6D). Importantly, inhibition of glycolysis enhanced sensitivity to kinase inhibition even in control p190 cells. Thus, imatinib leads to p53-dependent apoptosis that can be attenuated by glucose metabolism.

Loss of p53 is clinically associated with imatinib resistance(31, 32), and our data demonstrated a key role for metabolism in both p53 regulation and imatinib sensitivity. Therefore, we examined the response to 2-DOG and imatinb in p53 wild type (Nalm-1)(33) and null (K562)(34) human CML cell lines (Figure 6E, Supplemental Figure 9). Consistent with findings from BCR-Abl-expressing murine cells, Nalm-1 cells underwent apoptosis in response to imatinib that was enhanced by addition of a sub-lethal dose of 2-DOG. In contrast, K562 were more resistant to imatinib and addition of 2-DOG did not augment cell death. These findings demonstrate that manipulation of metabolism can enhance the response to targeted therapy in human cancer cells, and this appears to depend on p53.

Discussion

Oncogenic kinases can provide signals to allow cancer cells to persist independent of growth factors. Recently developed targeted therapies can block these signaling pathways to suppress glucose uptake(9, 10) and elicit apoptosis(9, 35). We previously showed that activation of p53 and induction of Puma to promote apoptosis after growth factor withdrawal could be prevented by maintenance of aerobic glycolysis. However, it remained unclear how p53 was activated and whether p53 inhibition by glucose metabolism was specific to cytokine deprivation or was applicable to other apoptotic stresses. Here, we show that growth factor deprivation of normal cells or treatment of BCR-Abl-expressing cells with imatinib lead to a metabolic stress pathway that activates p53 and elicits Puma-dependent apoptosis. This pathway was distinct from the DNA damage pathway regarding the mechanism of p53 activation and target gene regulation. While multiple pro-apoptotic proteins, such as the BH3-only proteins Bim and Bad can contribute to cell death after imatinib treatment(36), our data indicate a clear role for Puma in cell death that is uniquely sensitive to cell metabolism. Together, these data show that metabolic control of p53-mediated Puma induction is a critical determinant of imatinib sensitivity.

These distinct types of cell stress appear to utilize specific mechanisms of p53 activation, with differential stabilization of p53 and reliance on unique upstream kinases. Unlike the DNA damage response pathway, in which p53 stabilization was apparent and considered important for p53 activity(37), the phosphorylation and activation of p53 in the context of cytokine deprivation occurred in the absence of any observable changes in p53 protein levels. In addition, distinct from the well-described ATM/ATR-mediated DNA damage pathway or AMPK-dependent glucose deprivation pathway, the loss of metabolism caused by suppression of growth signals required PKCδ to elicit cell death, through both p53-dependent and p53-independent mechanisms.

While PKCδ-dependent phosphorylation of p53 did not appear to be direct, PKCδ may serve as a metabolic sensor to initiate a pathway that culminates in p53 activation. Indeed, glucose metabolism can regulate several PKC isoforms in response to altered lipid metabolism caused by hyperglycemia(38, 39). Cells with intrinsically high rates of glucose uptake, such as growth factor-stimulated or cancerous cells, may utilize similar mechanisms to regulate PKCs. Consistent with this notion, we have found that PKCμ and PKCε localization are altered in Glut1/HK1-expressing cells(16) (and data not shown). It remains unclear, however, how PKCδ is regulated by glucose metabolism following cytokine withdrawal and why this is essential for p53 activation.

Transcriptionally, p53 can regulate the expression of numerous target genes. However, the mechanisms governing which p53 target genes are induced in response to particular stresses remain unclear. Here, we show that despite shared phosphorylation on mSer18, distinct pathways of p53 activation induced unique sets of target genes. This disparity could be explained by differences in the degree of phosphorylation or by the modification of other residues of p53 by phosphorylation or acetylation. These variations in modification likely affected recruitment of coactivators and/or corepressors of p53 activity, which could promote differential target gene selection.

Specific regulation of transcriptional cofactors may also contribute to the increase in Puma levels after cytokine withdrawal. Indeed, the multi-stress transcription factor CHOP can contribute to Puma upregulation following cytokine withdrawal(40) and could cooperate with p53 to induce Puma in this context. FoxO3a has also been implicated in Puma induction following cytokine withdrawal(41). While FoxO3a may regulate Puma in certain contexts, the lack of Puma induction in p53−/− T lymphocytes and the reduced Puma induction in p53 S18A T lymphocytes suggests that p53 is essential for the majority of Puma induction in this cell type.

A key finding was that glycolytic metabolism provided protection against cell death after inhibition of growth signals but not DNA damage. These specific modes of p53 and apoptotic regulation by glucose metabolism may allow cells to adjust their response to stress based on nutrient availability. The high glucose uptake of activated lymphocytes or BCR-Abl transformed cells may suppress stress pathways during transient reductions in signaling. In contrast, initiating cell cycle arrest or apoptosis in response to damaged DNA is likely critical in nutrient-replete conditions, which may otherwise favor cell proliferation. These findings imply that inhibition of glucose metabolism may be central to the pro-apoptotic effect of kinase inhibitors and that further inhibition of glycolysis may augment these therapies to increase effectiveness and reduce resistance. Additionally, glycolysis inhibition failed to enhance imatinib sensitivity in p53-null K562, suggesting that the outcome of metabolic manipulation may depend on the p53 status of a given tumor.

Imatinib is highly effective in inducing durable responses in patients with newly diagnosed CML in the chronic phase(42, 43). Resistance to imatinib can arise from BCR-Abl kinase mutations(44). However, a notable percentage of CML patients with no kinase domain mutations fail to respond to imatinib(13, 45, 46), and recent work demonstrated elevated glucose metabolism in imatinib-resistant cells(47), supporting a connection between metabolism and drug resistance. Together, our findings suggest that targeted therapies may be particularly sensitive to cell metabolism, and metabolic manipulation may provide a novel means to enhance the efficacy of molecular targeted cancer treatments and overcome therapeutic resistance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Rathmell lab, Dr. Tso-Pang Yao (Duke University), and Dr. Kimryn Rathmell (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill) for constructive comments and suggestions. p53−/− mice were generously provided by Dr. David Kirsch (Duke University), and reagents were provided by Dr. Tso-Pang Yao.

This work was supported by NIH R01 CA123350 (J.C.R.), NIH F30 HL094044 (E.F.M.), RO1CA077735 (S.N.J.), the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Scholar Award (J.C.R.), Alex’s Lemonade Stand (J.C.R). J.C.R. is the Bernard Osher Fellow of the American Asthma Foundation.

References

- 1.Raff MC. Social controls on cell survival and cell death. Nature. 1992;356(6368):397–400. doi: 10.1038/356397a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rathmell JC, Vander Heiden MG, Harris MH, Frauwirth KA, Thompson CB. In the absence of extrinsic signals, nutrient utilization by lymphocytes is insufficient to maintain either cell size or viability. Mol Cell. 2000;6(3):683–92. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100(1):57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123(3191):309–14. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vander Heiden MG, Plas DR, Rathmell JC, Fox CJ, Harris MH, Thompson CB. Growth factors can influence cell growth and survival through effects on glucose metabolism. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(17):5899–912. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.17.5899-5912.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciofani M, Zuniga-Pflucker JC. Notch promotes survival of pre-T cells at the beta-selection checkpoint by regulating cellular metabolism. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(9):881–8. doi: 10.1038/ni1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wieman HL, Wofford JA, Rathmell JC. Cytokine stimulation promotes glucose uptake via phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/Akt regulation of Glut1 activity and trafficking. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(4):1437–46. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-07-0593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gottlob K, Majewski N, Kennedy S, Kandel E, Robey RB, Hay N. Inhibition of early apoptotic events by Akt/PKB is dependent on the first committed step of glycolysis and mitochondrial hexokinase. Genes Dev. 2001;15(11):1406–18. doi: 10.1101/gad.889901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnes K, McIntosh E, Whetton AD, Daley GQ, Bentley J, Baldwin SA. Chronic myeloid leukaemia: an investigation into the role of Bcr-Abl-induced abnormalities in glucose transport regulation. Oncogene. 2005;24(20):3257–67. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gottschalk S, Anderson N, Hainz C, Eckhardt SG, Serkova NJ. Imatinib (STI571)-mediated changes in glucose metabolism in human leukemia BCR-ABL-positive cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(19):6661–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cambier N, Chopra R, Strasser A, Metcalf D, Elefanty AG. BCR-ABL activates pathways mediating cytokine independence and protection against apoptosis in murine hematopoietic cells in a dose-dependent manner. Oncogene. 1998;16(3):335–48. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kruser TJ, Wheeler DL. Mechanisms of resistance to HER family targeting antibodies. Exp Cell Res. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mauro MJ. Defining and managing imatinib resistance. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2006:219–25. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2006.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wendel HG, de Stanchina E, Cepero E, Ray S, Emig M, Fridman JS, et al. Loss of p53 impedes the antileukemic response to BCR-ABL inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(19):7444–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602402103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whiteside CI, Dlugosz JA. Mesangial cell protein kinase C isozyme activation in the diabetic milieu. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002;282(6):F975–80. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00014.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao Y, Altman BJ, Coloff JL, Herman CE, Jacobs SR, Wieman HL, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase 3alpha and 3beta mediate a glucose-sensitive antiapoptotic signaling pathway to stabilize Mcl-1. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(12):4328–39. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00153-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao Y, Coloff JL, Ferguson EC, Jacobs SR, Cui K, Rathmell JC. Glucose metabolism attenuates p53 and Puma-dependent cell death upon growth factor deprivation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(52):36344–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803580200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rathmell JC, Fox CJ, Plas DR, Hammerman PS, Cinalli RM, Thompson CB. Akt-directed glucose metabolism can prevent Bax conformation change and promote growth factor-independent survival. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(20):7315–28. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.20.7315-7328.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kajino T, Omori E, Ishii S, Matsumoto K, Ninomiya-Tsuji J. TAK1 MAPK kinase kinase mediates transforming growth factor-beta signaling by targeting SnoN oncoprotein for degradation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(13):9475–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700875200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erlacher M, Labi V, Manzl C, Bock G, Tzankov A, Hacker G, et al. Puma cooperates with Bim, the rate-limiting BH3-only protein in cell death during lymphocyte development, in apoptosis induction. J Exp Med. 2006;203(13):2939–51. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simonian PL, Grillot DA, Nunez G. Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL can differentially block chemotherapy-induced cell death. Blood. 1997;90(3):1208–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karnauskas R, Niu Q, Talapatra S, Plas DR, Greene ME, Crispino JD, et al. Bcl-x(L) and Akt cooperate to promote leukemogenesis in vivo. Oncogene. 2003;22(5):688–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vousden KH. Outcomes of p53 activation--spoilt for choice. J Cell Sci. 2006;119(Pt 24):5015–20. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sluss HK, Armata H, Gallant J, Jones SN. Phosphorylation of serine 18 regulates distinct p53 functions in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(3):976–84. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.3.976-984.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang Y, Zhao W, Chen Y, Zhao Y, Gu W. Acetylation is indispensable for p53 activation. Cell. 2008;133(4):612–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito A, Lai CH, Zhao X, Saito S, Hamilton MH, Appella E, et al. p300/CBP-mediated p53 acetylation is commonly induced by p53-activating agents and inhibited by MDM2. EMBO J. 2001;20(6):1331–40. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones RG, Plas DR, Kubek S, Buzzai M, Mu J, Xu Y, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase induces a p53-dependent metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2005;18(3):283–93. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romero Rosales K, Peralta ER, Guenther GG, Wong SY, Edinger AL. Rab7 activation by growth factor withdrawal contributes to the induction of apoptosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20(12):2831–40. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-09-0911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee SJ, Kim DC, Choi BH, Ha H, Kim KT. Regulation of p53 by activated protein kinase C-delta during nitric oxide-induced dopaminergic cell death. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(4):2215–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509509200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoshida K, Liu H, Miki Y. Protein kinase C delta regulates Ser46 phosphorylation of p53 tumor suppressor in the apoptotic response to DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(9):5734–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512074200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calabretta B, Perrotti D. The biology of CML blast crisis. Blood. 2004;103(11):4010–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamamoto K, Yakushijin K, Nishikawa S, Minagawa K, Katayama Y, Shimoyama M, et al. Imatinib resistance in a novel translocation der(17)t(1;17)(q25;p13) with loss of TP53 but without BCR/ABL kinase domain mutation in chronic myelogenous leukemia. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2008;183(1):77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minowada J, Tsubota T, Greaves MF, Walters TR. A non-T, non-B human leukemia cell line (NALM-1): establishment of the cell line and presence of leukemia-associated antigens. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1977;59(1):83–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/59.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Law JC, Ritke MK, Yalowich JC, Leder GH, Ferrell RE. Mutational inactivation of the p53 gene in the human erythroid leukemic K562 cell line. Leuk Res. 1993;17(12):1045–50. doi: 10.1016/0145-2126(93)90161-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takeuchi K, Ito F. EGF receptor in relation to tumor development: molecular basis of responsiveness of cancer cells to EGFR-targeting tyrosine kinase inhibitors. FEBS J. 2010;277(2):316–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuroda J, Puthalakath H, Cragg MS, Kelly PN, Bouillet P, Huang DC, et al. Bim and Bad mediate imatinib-induced killing of Bcr/Abl+ leukemic cells, and resistance due to their loss is overcome by a BH3 mimetic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(40):14907–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606176103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kruse JP, Gu W. Modes of p53 regulation. Cell. 2009;137(4):609–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu D, Peng F, Zhang B, Ingram AJ, Kelly DJ, Gilbert RE, et al. PKC-beta1 mediates glucose-induced Akt activation and TGF-beta1 upregulation in mesangial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(3):554–66. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008040445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cosentino F, Eto M, De Paolis P, van der Loo B, Bachschmid M, Ullrich V, et al. High glucose causes upregulation of cyclooxygenase-2 and alters prostanoid profile in human endothelial cells: role of protein kinase C and reactive oxygen species. Circulation. 2003;107(7):1017–23. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000051367.92927.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Altman BJ, Wofford JA, Zhao Y, Coloff JL, Ferguson EC, Wieman HL, et al. Autophagy provides nutrients but can lead to Chop-dependent induction of Bim to sensitize growth factor-deprived cells to apoptosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20(4):1180–91. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-08-0829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.You H, Pellegrini M, Tsuchihara K, Yamamoto K, Hacker G, Erlacher M, et al. FOXO3a-dependent regulation of Puma in response to cytokine/growth factor withdrawal. J Exp Med. 2006;203(7):1657–63. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Lavallade H, Apperley JF, Khorashad JS, Milojkovic D, Reid AG, Bua M, et al. Imatinib for newly diagnosed patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: incidence of sustained responses in an intention-to-treat analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(20):3358–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Druker BJ, Guilhot F, O’Brien SG, Gathmann I, Kantarjian H, Gattermann N, et al. Five-year follow-up of patients receiving imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(23):2408–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gorre ME, Mohammed M, Ellwood K, Hsu N, Paquette R, Rao PN, et al. Clinical resistance to STI-571 cancer therapy caused by BCR-ABL gene mutation or amplification. Science. 2001;293(5531):876–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1062538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Lavallade H, Finetti P, Carbuccia N, Khorashad JS, Charbonnier A, Foroni L, et al. A gene expression signature of primary resistance to imatinib in chronic myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soverini S, Colarossi S, Gnani A, Rosti G, Castagnetti F, Poerio A, et al. Contribution of ABL kinase domain mutations to imatinib resistance in different subsets of Philadelphia-positive patients: by the GIMEMA Working Party on Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(24):7374–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kominsky DJ, Klawitter J, Brown JL, Boros LG, Melo JV, Eckhardt SG, et al. Abnormalities in glucose uptake and metabolism in imatinib-resistant human BCR-ABL-positive cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(10):3442–50. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.