Abstract

Objectives

The Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) is a self-report measure of risk for aberrant medication related behavior among persons with chronic pain who are prescribed opioids for pain. It was developed to complement predictive screeners of opioid misuse potential and improve a clinician's ability to periodically assess a patient's risk for opioid misuse. The aim of this study was to cross validate the COMM with a new sample of chronic noncancer pain patients.

Methods

Two hundred and twenty six (N=226) participants prescribed opioids for pain were recruited from five pain management centers in the US. Subjects completed the 17-item COMM and a series of self-report measures. Patients were rated by their treating physician, had a urine toxicology screen, and were classified on the Aberrant Drug Behavior index.

Results

The reliability and predictive validity in this cross validation as measured by the area under the curve (AUC) were found to be highly significant (AUC =.79) and not significantly different from the AUC obtained in the original validation study (AUC =.81). Reliability (coefficient α) was .83, which is comparable to the .86 obtained in the original sample.

Discussion

Results of the cross validation suggest that the psychometric parameters of the COMM are not based solely on unique characteristics of the initial validation sample. The COMM appears to be a reliable and valid screening tool to help detect current aberrant drug-related behavior among chronic pain patients.

Keywords: substance abuse, chronic pain, opioids, addiction, aberrant drug behaviors, cross validation

Introduction

While the use of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain is increasing, prescription opioid abuse as a negative consequence of opioid availability is also on the rise.1-2 Opioids can be an effective treatment for chronic pain, yet providers are reluctant to prescribe opioids because of concerns over tolerance, dependence, and addiction. Some pain centers where opioids are prescribed are overwhelmed with problem patients, and many physicians prescribing pain medication have little training in addiction or in dealing with aberrant medication-related behavior.3 Physicians are often faced with the difficult position of providing appropriate pain relief while minimizing the inappropriate use of pain medications4 and, in surveys of primary care physicians, a third of responders indicated that they would not, under any circumstance, prescribe opioids to patients with chronic noncancer pain.5-6 It is important for the successful treatment of chronic, noncancer pain to be able to identify patients on opioid regimens currently exhibiting abuse behavior.7-8 Clinicians continuously identify the need for additional opioid risk management tools and training to objectively assess and monitor chronic pain patients being considered for opioid therapy.

The Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM)9 was created to enhance the treatment of chronic pain patients and improve clinician comfort with opioid therapy. The COMM is different from measures that were created to identify patient characteristics that would likely lead to trouble with opioids (predicting misuse behaviors). Rather, the COMM helps to identify those patients prescribed opioids for pain who are currently misusing opioids. The aim of this study was to cross-validate the COMM in a new population of pain patients and to confirm the usefulness of this self-assessment to gauge who is currently misusing opioids.

Concise definitions of terms are important to minimize confusion and help to clarify the objectives of this study.10 For purposes of this investigation, substance misuse is defined as the use of any drug in a manner other than how it is indicated or prescribed. Substance abuse is defined as the use of any substance when such use is unlawful, or when such use is detrimental to the user or others. Prescription opioid addiction is a primary, chronic, neurobiologic disease that is characterized by behaviors that include one of more of the following: impaired control over drug use, compulsive use, continued use despite harm, and craving.11-12 Aberrant drug-related behaviors are any behaviors that suggest the presence of substance abuse or addiction. Determining an individual's potential for aberrant drug behaviors and preventing misuse of prescription opioids is important in the evaluation and management of patients with chronic pain.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited and followed for five months as part of a larger study intended to cross validate the predictive validity of another scale (SOAPP-R).13 The COMM cross validation study began only during the follow up assessment, five months following their recruitment. This study's procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Committee of the various participating centers. Chronic noncancer pain patients were recruited from pain management centers in Boston, MA, Toledo, OH, Allentown, PA, Indianapolis, IN, and Lebanon, NH. Patients prescribed opioids for their pain were informed about the study and invited to participate. This study took place with the cooperation of five different pain centers in five different states. Patients were recruited consecutively and flyers were available for the study in all of the centers. An inclusion criterion for participation in the study was that the subjects were taking prescription opioids at the time that they participated in the trial. All subjects signed an informed consent form and were assured that the information obtained through their questionnaire responses and from the urine toxicology screens would remain confidential and would not be part of their clinic record. Participant patients were paid with a $50 gift certificate for completing the measures.

Patient Completed Measures

The same self-report measures used to initially evaluate the COMM were administered to this cohort of patients.

The Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM)9

The COMM contains 17 items rated from 0=”never” to 4=”very often” (see Table 1). The COMM was developed to track patient status over time, so items included in the COMM can be used repeatedly and provide an estimate of the patients “current” status. Thus, items capture a 30-day time period (i.e., “in the past 30 days,”), and only behaviors that could change from time to time were included (i.e., historical items were excluded). The 17 items are summed to create a total score.

TABLE 1.

List of COMM questions

| In the past 30 days. . . |

| 1. How often have you had trouble with thinking clearly or had memory problems? |

| 2. How often do people complain that you are not completing necessary tasks? (i.e., doing things that need to be done, such as going to class, work, or appointments) |

| 3. How often have you had to go to someone other than your prescribing physician to get sufficient pain relief from your medications? (i.e. another doctor, the Emergency Room) |

| 4. How often have you taken your medications differently from how they are prescribed? |

| 5. How often have you seriously thought about hurting yourself? |

| 6. How much of your time was spent thinking about opioid medications (having enough, taking them, dosing schedule, etc.)? |

| 7. How often have you been in an argument? |

| 8. How often have you had trouble controlling your anger (e.g., road rage, screaming, etc)? |

| 9. How often have you needed to take pain medications belonging to someone else? |

| 10. How often have you been worried about how you're handling your medications? |

| 11. How often have others been worried about how you're handling your medications? |

| 12. How often have you had to make an emergency phone call or show up at the clinic without an appointment? |

| 13. How often have you gotten angry with people? |

| 14. How often have you had to take more of your medication than prescribed? |

| 15. How often have you borrowed pain medication from someone else? |

| 16. How often have you used your pain medicine for symptoms other than for pain (e.g. to help you sleep, improve your mood, or relieve stress)? |

| 17. How often have you had to visit the Emergency Room? |

The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI)14

The BPI is a well-known, self-report, multidimensional pain questionnaire. The BPI provides information about pain history, intensity, and location as well as the degree to which the pain interferes with daily activities, mood, and influences enjoyment of life. Scales (rated from 1 to 10) indicate the intensity of pain at its worst, at its least, average pain, and pain “right now.” Testretest reliability for the BPI reveals correlations of .93 for worst pain, .78 for usual pain, and .59 for pain now. Research suggests the BPI has adequate validity and has been adopted in many countries for clinical pain assessment, epidemiological studies, and in studies of the effectiveness of pain treatment. Although originally developed to assess cancer pain, the BPI has been validated for use for patients with chronic noncancer pain.15

Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire (PDUQ)16

Self-report of patient status at follow-up was obtained using the PDUQ. This 42-item structured interview is probably the most well-developed abuse-misuse assessment instrument for pain patients at this time.17 The PDUQ is a 20-minute interview during which the patient is asked about his or her pain condition, opioid use patterns, social and family factors, family history of pain and substance abuse, and psychiatric history. In an initial test of the psychometric properties of the PDUQ, the standardized Cronbach's alpha was 0.79, suggesting acceptable internal consistency. Compton and her colleagues suggested that subjects who scored below 11 did not meet criteria for a substance use disorder, while whose with a score of 11 or greater showed signs of a substance use disorder. For purposes of this study we used scores greater than 11 on the PDUQ as a positive indicator for the Aberrant Drug Behavior Index.

Prescription Opioid Therapy Questionnaire (POTQ)18

Each patient's physician was asked to complete the POTQ. This 11-item scale, adapted from the Physician Questionnaire of Aberrant Drug Behavior,19 was completed by the treating clinician to assess misuse of opioids. The items reflect the behaviors outlined by Chabal and colleagues20 that were indicative of substance abuse. The participant patient's chart was made available to the treating physician to facilitate accurate recall of information. Providers answered yes or no to eleven questions indicative of misuse of opioids, including multiple unsanctioned dose escalations, episodes of lost or stolen prescriptions, frequent unscheduled visits to the pain center or emergency room, excessive phone calls, and inflexibility around treatment options. The POTQ has been found to be significantly correlated with the PDUQ and abnormal urine screens (p<0.01) as an external measure of its validity.21 Patients’ ratings of craving opioid medication has also been found to be significantly correlated with physicians ratings on the POTQ.21 Patients who were positively rated on two or more of the items met criteria for prescription opioid misuse, as indicated in previous investigations.22-23

Toxicology Screen

Participating patients were requested to provide a urine sample during their follow-up visit and to inform staff of their current medications. Patients were informed that information from the toxicology screen would remain confidential and not be part of their medical record. Each patient was given a specimen cup and instructed to provide a urine sample (~30 –75 ml of urine) without supervision in the clinic bathroom. The RA at each center collected and shipped the sample to a central Quest Diagnostics lab (www.questdiagnostics.com). The results of the urine toxicology were sent directly to the research team. The treating physician and the clinic did not have access to the results. The report included evidence of 6-MAM (heroin), codeine, dihydrocodeine, morphine, oxycodone, oxymorphone, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, meperidine, methadone, propoxyphene, buprenophine, fentanyl, tramadol, amphetamines, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, cannabinoids, cocaine, phencyclidine, and ethyl alcohol.

Aberrant Drug Behavior Index (ADBI)

Patients were classified as to whether they engaged in aberrant medication-related behavior. Aberrant medication use incorporates a variety of behaviors commonly believed to be associated with opioid medication misuse, abuse, and addiction.10 Since there is no gold standard for identifying which patients are and which are not abusing their prescription medications,24 we classified patients into categories of aberrant medication-related behavior by triangulating three perspectives; self-report via structured interview, physician report, and urine toxicology results. The ADBI is based on positive scores on 1) the self-reported PDUQ, 2) the physician-reported POTQ, and 3) the urine toxicology results. A positive rating on the PDUQ is an accumulated score higher than 11. A positive rating on the POTQ is given to anyone who has two or more physician-rated aberrant behaviors.13 A positive rating from the urine screens is given to anyone with evidence of having taken an illicit substance (e.g., cocaine) or an additional opioid medication that was not prescribed. We chose not to count the omission of a prescribed opioid medication from the urine screen results as a positive rating because of multiple factors that can contribute to this result (e.g., subject ran out the medication before the urine screen). We also did not classify urines that were rejected by the lab. Urine screen results were confirmed based on chart review of prescription history and a comparison between self-report at the time of the urine screen and the toxicology report. Those with positive scores on the PDUQ were given a positive ADBI. If this score was negative, then positive scores on both the urine toxicology screen and on the POTQ (≥2) contributed to a positive ADBI. This allowed for triangulation of data to identify those patients who admitted to aberrant medication-related behavior and those who underreported aberrant behavior (e.g., low PDUQ scores, but positive POTQ and abnormal urine screen results). For those patients who did not have results of urine toxicology screens, ADBI classification was based on results of the PDUQ and POTQ.

We believe that self-report, when positive, is the most direct measure of a substance use disorder, since false positives (i.e., patients reporting the presence of a substance use disorder when none is present) are presumably quite rare. Thus, those participants who met criteria for a substance use disorder based on the interviewer-administered Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire (PDUQ > 11) were given a positive score on the ADBI. If not, then we scored the ADBI as positive if there were positive urine screen results and 2 or more physician-rated aberrant behaviors (POTQ > 1). We decided this after considerable discussion because urine screens can be problematic (e.g., mistakes can be made with urine screen results based on variable drug metabolites and different cutoffs used in detecting a drug). We also know from experience that physician ratings of aberrant behavior can be unreliable.7, 25 An analysis of past data found that those with the most problematic urine screen results (e.g., tested positive for cocaine) also were positive on the PDUQ, which lent support for the reliability of this classification method.21

Procedures

The 17-item COMM was administered to a new group of chronic pain patients from the participating pain centers. All procedures for the cross validation were identical to those used in the validation stage.26 All patients completed the PDUQ, BPI, a urine sample for toxicology screening was collected. Chart reviews were conducted to confirm prescriptions.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed with SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences; Chicago, IL) v.18.0. Comparisons of the original and cross validation demographic and pain characteristics data were analyzed using t-test comparisons for independent samples for percentages and means. In addition, coefficient alpha and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were conducted. Comparison of the original and cross validation ROC curves was made using MedCalc software (v. 9.5.2).

Results

As part of another cross validation study,27 302 chronic pain patients were recruited and followed for five months. At the five-month follow-up, 226 individuals (75%) completed the 17-item COMM. Table 2 presents demographic and descriptive data on the cross validation sample as well as the original COMM validation sample reported by Butler and colleagues.26 As the analyses presented in Table 2 suggest, the two samples were not significantly different for age, race (percent Caucasian versus percent minority), or percent holding at least a high school education. Significant differences were observed for the gender makeup of the two samples, with the cross validation having 48.2% women which was significantly fewer than the 61.7% in the original COMM validation sample (t = 2.8, df = 450, p = .005) and marital status, with 56.5% married in the cross validation sample and only 43% married in the original sample (t = 2.9, df = 450, p = .004). Characteristics of the two pain patient samples were not different on most measured variables, with the exception of rated amount of pain relief from medications, which was greater in the original validation sample and pain interference with general activity which was greater in the original validation sample. Patients recruited in the initial study came from two hospital-based pain management centers and a private pain management treatment center and inclusion criteria were identical in both studies. Although four out of 19 variables examined were statistically significantly different, the two samples appeared to be generally similar.

TABLE 2.

Patient demographics and descriptive characteristics for original and cross validation samples

| Variable | Original COMM Validation Study (Butler et. al., 2007) | Cross validation Study | t value | df | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| | |||||

| N = 227 | N=226 | ||||

| Age | 50.8 (SD = 12.4; range 21-89) | 51.5 (SD = 13.8; range 22-83) | 0.6 | 450 | NS |

| Gender (% female) | 61.7 | 48.4 | 2.8 | 450 | .005 |

| Married (% yes) | 43.0 | 56.5 | 2.9 | 450 | .004 |

| Race (% Caucasian) | 83.3 | 87.1 | 1.1 | 450 | NS |

| High school graduate (% yes) | 87.3 | 88.8 | 0.5 | 448 | NS |

| Pain site (% low back) | 67.9 | 59.7 | 1.8 | 451 | NS |

| Yrs taking opioids | 5.7 (SD = 9.2; range 5 mos to 66 yrs) | 5.4 (SD = 5.8; range 1 mo to 38 yrs) | 0.6 | 439 | NS |

| Pain;† | |||||

| Worst (24 hrs; 0-10) | 7.3 (SD = 2.1; range 0-10) | 7.0 (SD = 2.3; range 0-10) | 1.5 | 451 | NS |

| Least (24 hrs; 0-10) | 4.5 (SD = 2.2; range 0-10) | 4.5 (SD = 2.4; range 0-10) | 0 | 450 | NS |

| Average (24 hrs; 0-10) | 5.9 (SD = 1.8; range 0-10) | 5.9 (SD = 1.9; range 0-10) | 0 | 451 | NS |

| Now (0-10) | 5.8 (SD = 2.2; range 0-10) | 5.5 (SD = 2.3; range 0-10) | 1.4 | 451 | NS |

| Pain relief from meds* (0-10) | 6.3 (SD = 2.3; range 0-10) | 5.7 (SD = 2.3; range 0-10) | 2.8 | 451 | .006 |

| Pain interference with:‡ | |||||

| General activity | 6.5 (SD = 2.6; range 0-10) | 5.9 (SD = 2.6; range 0-10) | 2.5 | 450 | .01 |

| Mood | 5.1 (SD = 2.7; range 0-10) | 4.6 (SD = 2.9; range 0-10) | 1.9 | 450 | NS |

| Walking | 6.1 (SD = 3.0; range 0-10) | 5.9 (SD = 3.1; range 0-10) | 0.7 | 450 | NS |

| Normal work | 7.2 (SD = 2.6; range 0-10) | 6.7 (SD = 2.9; range 0-10) | 1.9 | 449 | NS |

| Relations with others | 4.0 (SD = 3.2; range 0-10) | 3.8 (SD = 3.1; range 0-10) | 0.7 | 450 | NS |

| Sleep | 6.3 (SD = 3.1; range 0-10) | 5.9 (SD = 3.0; range 0-10) | 1.4 | 450 | NS |

| Enjoyment of life | 6.2 (SD = 3.0; range 0-10) | 6.0 (SD = 3.1; range 0-10) | .07 | 450 | NS |

0=no pain; 10=pain as bad as you can imagine

0=no relief; 10=complete relief

0=does not interfere; 10=completely interferes

COMM scores for patients in the cross validation sample averaged 8.96 (SD = 7.0) and ranged between 0 and 44. Of the 226 patients, 216 were rated on the ADBI and were classified as either positive (34.2%) or negative for aberrant medication-related behaviors. Of those with positive ADBIs, 95.5% had a positive PDUQ. The remaining individuals were identified based on the POTQ and urine tox data. Ten subjects could not be classified because of missing data. No differences were found between the ten subjects with missing data and the 216 who were classified. The original validation of the COMM suggested a cutoff score of 9 would be suggestive of aberrant medication-related behaviors. Using this cutoff, 41.6% of the subjects had a positive COMM score, while 58.4% had a negative score (below 9).

Cross Validation of COMM Reliability

The cross validation revealed good replication of the reliability (internal consistency) statistics of the COMM. Internal consistency for the cross validation was also excellent with a coefficient α was .83. This value compares well with the coefficient α obtained in the original study (.86) suggesting the COMM has stable reliability parameters.

Cross Validation of Validity

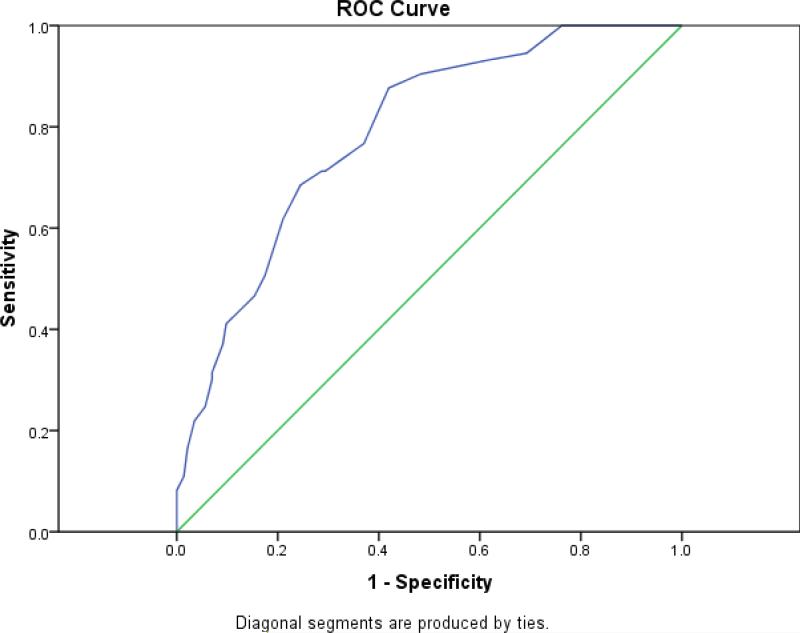

As in the original validation, the validity test evaluated the COMM in relation to patients’ ADBI scores after five months. Repetition of the ROC analysis revealed an AUC of .79 (Standard error = .031; 95% CI: .73 to .85; p < .001). Figure 1 presents the ROC curve and Table 3 presents the sensitivity and specificity cutoff estimates for the range of the COMM Prediction Scores gauged against the Aberrant Drug Behavior Index. As expected, there was some shrinkage observed in the AUC value when tested in an entirely new population, although the shrinkage was minimal. The original ROC curve analysis yielded an AUC of .81 (Standard error = .031; 95% CI: .74 to 86; p < .001). A test of independent ROC curves was not significant (z = .456, NS).

FIGURE 1.

Cross validation receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve COMM prediction score sensitivity and specificity estimates gauged against the aberrant drug behavior index. (Note: Diagonal line represents chance prediction)

TABLE 3.

COMM score sensitivity and specificity estimates gauged against the aberrant drug behavior index (ADBI)

| COMM score positive if greater than or equal to |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| 1.00 | 1.000 | .077 |

| 2.00 | 1.000 | .154 |

| 3.00 | 1.000 | .238 |

| 4.00 | .945 | .308 |

| 5.00 | .932 | .385 |

| 6.00 | .904 | .517 |

| 7.00 | .877 | .580 |

| 8.00 | .767 | .629 |

| 8.25 | .712 | .706 |

| 9.00 | .712 | .713 |

| 10.00 | .685 | .755 |

| 11.00 | .616 | .790 |

| 12.00 | .507 | .825 |

| 13.00 | .466 | .846 |

| 14.00 | .438 | .874 |

| 15.00 | .411 | .902 |

| 16.00 | .370 | .909 |

| 16.25 | .315 | .930 |

| 17.00 | .301 | .930 |

| 18.00 | .247 | .944 |

| 19.00 | .219 | .965 |

| 20.00 | .192 | .972 |

| 21.00 | .164 | .979 |

| 22.00 | .110 | .986 |

| 23.00 | .082 | .000 |

| 25.00 | .068 | .000 |

| 27.00 | .055 | .000 |

| 29.00 | .041 | .000 |

| 34.00 | .027 | .000 |

| 41.00 | .014 | .000 |

| 45.00 | .000 | .000 |

Discussion

The present study reports on an effort to cross-validate the COMM. The COMM is a self-report measure of current risk for aberrant medication-related behavior among persons with chronic pain. In an original validation study,18 the COMM was found to be a reliable and valid measure. Cross validation of a scale on a new sample of respondents is a rigorous psychometric step that is necessary, since scale development efforts like the one used to create the COMM selected items based on their correlation with the target construct. Cross validation ensures that the psychometric coefficients observed during construction are not inordinately based on chance relationships to the target construct in the original sample. Results of the cross validation effort reported here suggest that the psychometric parameters of the COMM are not based solely on unique characteristics of the initial validation sample.

While the COMM requires additional research, this study suggests that it may be a better screening tool than other measures (e.g., the CAGE28 that has no empirical base with a chronic pain population). At a minimum, the COMM can be used to alert the physician to potential risks and avert future problems. Patients’ responses to the COMM questions access information not necessarily obtained during a follow-up evaluation, especially by a non-specialist. Documentation of these responses might prove helpful in a medical/legal context by providing a basis upon which to decide whether to request more frequent office visits, pill counts, urine toxicology screens, or discontinuation of therapy. Patients taking opioids for pain identified with high COMM scores may also benefit from motivational counseling focused on managing thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, (e.g., coping with urges, making lifestyle changes, avoiding drug use triggers), and education about the appropriate use of opioids and avoiding relapse.29

The COMM should be used only with chronic pain patients being prescribed opioid therapy. Broad-based administration of the COMM for all patients with chronic pain would not be appropriate. The COMM may help the provider determine the level of monitoring appropriate for a particular patient. It also has the potential to be used to help modify patient behavior in collaboration with behavioral health professionals to directly address problems identified on the COMM (e.g., overusing of medication and borrowing medication from others) and to implement lower risk therapies. COMM scores are based upon the willing and direct responses of patients. While the COMM contains items for which the “correct” response may not be immediately transparent, patients determined to “look good” on the COMM will not find it difficult to do so. In our initial clinical work with similar self-report questionnaires (SOAPP v.1, and SOAPP-R) we found that many patients are truthful in their responses. Yet, it is critical for providers to consider the COMM results in the context of information from other sources, including history and physical examination, the clinical interview, discussions with family members, laboratory findings, and review of medical records.

The COMM was devised as a self-report measure to predict current aberrant medication-related behavior based on past behavior and/or cognition. The COMM has been designed and validated to pick up a variety of problematic behaviors that may increase risk of opioid misuse but which may have different causes (e.g. mood disorders, general problems with prescription non-adherence, addiction) and thus may warrant different clinical responses. The intent of this scale is to document current behavior on a periodic basis in order to continue to justify chronic opioid therapy and to help detect ongoing difficulties. It is our belief that the SOAPP-R and COMM will work in tandem to help identify problems associated with the use of prescription opioids for pain.

It is important to emphasize the limitations of this study. First, this study was conducted in anesthesia-based pain centers and included a volunteer sample of patients. The urine samples were collected unobserved and not all patients gave a urine sample for a toxicology screening. This raises the potential for selection bias because of missing data. When urine samples were not collected two other sources of patient status were used, but risk of selection bias remains. Continued efforts are needed to validate the COMM in other settings. Second, as with any study seeking consent, patients needed to agree to participate and some selected not to take part in this study. We recognize that the participants in this study represent only a subset of patients prescribed opioids for their pain and that differences were found between the subjects in the original validation study and this cross validation study, although the differences in the AUC were minimal. Third, usefulness of the present measure in a primary care clinic with patients with shorter duration of pain particularly needs to be determined. Attempts were made to include minorities, but further information on the usefulness of the COMM among different ethnic groups and pain populations is needed. Bayes Theorem30 postulates that the predictive value of diagnostic or laboratory tests is not constant but must change with the proportion of patients who actually have the target disorder among those who undergo the diagnostic evaluation. Thus, it is critical that the COMM not be used as a general screener in a primary care practice. It should be used instead only with chronic pain patients prescribed long-term opioid therapy, regardless of the setting. Also, use of the COMM repeatedly over a longer period of time has yet to be assessed.

Finally, shrinkage of coefficients obtained during cross validation of the ROC analyses is acknowledged. Although such shrinkage is expected, the AUCs for the cross validation and original validation samples were quite close (2 points difference; .79 and .81 respectively), both AUCs were well within each other's 95% CIs, and the AUCs were not significantly different. These results suggest a successful cross validation. While the sensitivity of the COMM at a cutoff of 9 was acceptable and comparable to the original validation, specificity was lower than desired in the cross validation. In this context sensitivity of a screener may be most important, as it may be most critical to ensure identification of those who later evidence problems with their medications. Lower specificity means that some patients will be mislabeled as having problems managing their medications when they do not in fact have such problems. Since any screening device has false positives and false negatives, it is up the provider to determine the level of tolerance for these types of errors with which he or she is comfortable.31 Finally, it should be noted that it is not well established how to operationally define the target (i.e., aberrant medication-related behavior). Such factors add noise to the data used to validate and cross-validate a scale like the COMM. Nevertheless, this cross validation effort demonstrates that identification of patients having problems with their opioid medications is significantly better than chance. And, as noted above, the COMM score should always be considered in light of other clinical data before medication decisions are made.

Conclusions

Cross validation of the COMM yielded promising results. While there was “shrinkage” in the values, which is expected when moving to a completely new sample of patients, the predictive validity as measured by the AUC remained highly significant. The COMM may offer clinicians a way to monitor misuse behaviors and to develop treatment strategies designed to minimize continued misuse. The COMM may serve as a useful tool for those providers who need to document their patients’ continued compliance and appropriate use of opioids for pain. The results of this measure may have the added benefit of reducing physicians’ concerns related to prescribing opioids and may keep patients more cognizant of their need to be responsible with these medications.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are extended to Matthew Bair, MaryJane Cerrone, Li Qing Chen, David Janfaza, Nathaniel Katz, Carla Krichbaum, Edward Michna, Leslie Morey, Sanjeet Narang, Srdjan Nedeljkovic, Bruce Nicholson, Kathryn Nyland, Sarah O'Shea, Edgar Ross, Carol Santa Maria, Glenn Swimmer, Ajay Wasan, Mary Ann Yakabonis and staff members of Brigham and Women's Hospital, Lehigh Valley Hospital, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Indiana University Hospital, and PainCare of Northwest Ohio for their participation in this study. This research was supported in part by grants (DA015617, Butler PI; DA024298, Jamison, PI) from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD and by an unrestricted grant to Inflexxion, Inc. from Endo Pharmaceuticals, Chadds Ford, PA.

Sources of Support: This research was supported in part by grants (DA015617, Butler PI; DA024298, Jamison, PI) from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD and by an unrestricted grant to Inflexxion, Inc. from Endo Pharmaceuticals, Chadds Ford, PA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Joransson DE, Ryan KM, Gilson AM, Dahl JL. Trends in medical use and abuse of opioid analgesics. JAMA. 2000;283:1710–1714. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.13.1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Office of Applied Studies Overview of findings from the 2002 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. DHHS publication No SMA 03-3774, NHSDA Series H-21. 2003.

- 3.Wasan AD, Wootton J, Jamison RN. Dealing with difficult patients in your pain practice. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2005;30:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hampton T. Physicians advised on how to offer pain relief while preventing opioid abuse. JAMA. 2004;292:1164–1166. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.10.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morley-Forster PK, Clark AJ, Speechley M, Moulin DE. Attitudes towards Opioid Use for Chronic Pain in Canada- A Canadian Physician Survey. Pain Res Manag. 2003;8:189–194. doi: 10.1155/2003/184247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Potter M, Schafer S, Gonzalez-Mendea E, Gjeltema K, et al. Opioids for chronic nonmalignant pain. Attitudes and practices of primary care physicians in the UCSF/Stanford Collaborative Research Network. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:145–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Passik S, Kirsh K. The need to identify predictors of aberrant drug-related behavior and addiction in patients being treated with opioids for pain. Pain Med. 2003;4:186–189. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman R, Li V, Mehrotra D. Treating pain patients at risk: evaluation of a screening tool in opioid-treated pain patients with and without addiction. Pain Med. 2003;4:181–184. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez KC, et al. Development and validation of the current opioid misuse measure. Pain. 2007;130:144–156. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savage SR, Joranson DE, Covington EC, et al. Definitions related to the medical use of opioids: Evolution towards universal agreement. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;26:655–667. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(03)00219-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Academy of Pain Medicine. The American Pain Society. The American Society of Addiction Medicine . Definitions related to the use of opioids for the treatment of pain: a consensus document from the American Academy of Pain Medicine, the American Pain Society, and the American Society of Addiction Medicine. ASAM; Chevy Chase, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Webster LR, Dove B. Avoiding Opioid Abuse While Managing Pain: A Guide for Practitioners. Sunrise River Press; North Branch, MN: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez K, Jamison RN. Validation of a screener and opioid assessment measure for patients with chronic pain. Pain. 2004;112:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23:129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan G, Jensen MP, Thornby JI, Shanti BF. Validation of the Brief Pain Inventory for chronic nonmalignant pain. J Pain. 2004;5:133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Compton P, Darakjian J, Miotto K. Screening for addiction in patients with chronic pain and “problematic” substance use: evaluations of a pilot assessment tool. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998;16:355–363. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(98)00110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Savage SR. Assessment for addiction in pain treatment settings. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:S28–38. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200207001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Butler SF, Fernandez K, Benoit C, et al. Validation of the revised Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPP-R). J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;9:360–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michna E, Ross EL, Hynes WL, et al. Predicting aberrant drug behavior in patients treated for chronic pain: importance of abuse history. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:250–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chabal C, Erjavec MK, Jacobson L, et al. Prescription opiate abuse in chronic pain patients: clinical criteria, incidence, and predictors. Clin J Pain. 1997;13:150–155. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199706000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wasan AD, Butler SF, Budman SH, et al. Does report of craving opioid medication predict aberrant drug behavior among chronic pain patients? Clin J Pain. 2009;25:193–198. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318193a6c4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez K, Jamison RN. Validation of a screener and opioid assessment measure for patients with chronic pain. Pain. 2004;112:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wasan AD, Butler SF, Budman SH, et al. Psychiatric history and psychologic adjustment as risk factors for aberrant drug-related behavior among patients with chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2007;23:307–315. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3180330dc5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Savage SR. Assessment for addiction in pain-treatment settings. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:S28–38. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200207001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michna E, Jamison RN, Pham LD, et al. Urine toxicology screening among chronic pain patients on opioid therapy: frequency and predictability of abnormal findings. Clin J Pain. 2007;23:173–179. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31802b4f95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez KC, et al. Development and validation of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure. Pain. 2007;130:144–156. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez KC, et al. Cross-Validation of a Screener to Predict Opioid Misuse in Chronic Pain Patients (SOAPP-R). J Addiction Med. 2009;3:66–73. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31818e41da. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayfield D, McLeod G, Hall P. The CAGE questionnaire: validation of a new alcoholism screening instrument. Am J Psychiatry. 1974;131:1121–1123. doi: 10.1176/ajp.131.10.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jamison RN, Ross EL, Michna E, et al. Substance misuse treatment for high-risk chronic pain patients on opioid therapy: a randomized trial. Pain. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.02.033. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meehl PE, Rosen A. Antecedent probability and the efficiency of psychometric signs, patterns or cutting scores. Psychol Bull. 1955;52:194–216. doi: 10.1037/h0048070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sackett DL, Haynes RB, Guyatt GH, Tugwell P. Clinical epidemiology: a basic science for clinical medicine. 2nd ed. Little, Brown & Co; Boston: 1991. [Google Scholar]