Abstract

Background

Patients with chronic kidney disease have been reported to have increased concentrations of blood tryptase. Detection of tryptase in the urine of healthy subjects has been reported.

Objective

The objective is to determine whether tryptase is indeed cleared by the kidneys.

Methods

Blood and urine collections were performed in healthy and systemic mastocytosis subjects. Total and mature tryptase concentrations in blood and total tryptase concentrations in urine were determined.

Results

Total tryptase levels in urine were below the limit of detection in both healthy subjects and those with systemic mastocytosis, even after concentrating the urine 10-fold. Thus, both mature and protryptase levels in urine are <0.2 ng/ml.

Conclusion

Tryptase is not cleared by the kidneys into the urine.

Key Words: Tryptase, Renal clearance

Introduction

Tryptase is a 30–35-kDa glycoprotein produced primarily by mast cells and to a much lesser magnitude by basophils [1]. In serum, normal levels of total tryptase (mature and precursor forms of α- and β-tryptases) (<15 ng/ml) and mature tryptase (<1 ng/ml) have been established [1]. Increased serum/plasma concentrations of mature and total tryptase are present in patients with anaphylaxis, and of total tryptase in patients with systemic mastocytosis [1], a myoproliferative variant of the hypereosinophilic syndrome [1] and a subset of acute myelocytic leukemia [1]. Additionally, an association between increased serum total tryptase levels and decreased renal function has been noted in a preliminary report [2], and a correlation between elevated serum total tryptase levels and pruritis was reported in hemodialysis patients [3]. The presence of tryptase in the urine of healthy subjects has been reported [4].

We hypothesize that tryptase is not cleared by the kidneys in healthy subjects nor in those with systemic mastocytosis and idiopathic anaphylaxis.

Methods

In order to evaluate the possibility that tryptase is cleared from the blood by the kidneys into the urine, blood and urine tryptase concentrations were determined in 6 healthy subjects, in 2 subjects with systemic mastocytosis and in 1 subject with idiopathic anaphylaxis after Institutional Review Board approvals and informed consent. Tryptase was measured in a spot urine specimen collected at patients’ baseline without anaphylaxis in the latter 3 patients, all of whom had elevated serum tryptase levels. Tryptase was measured in 24-hour urine specimens in healthy subjects with normal baseline serum tryptase levels. Normal serum creatinine determinations in the subjects confirmed that they had normal renal function. Previously described immunoassays were employed to determine the concentrations of mature tryptase and total tryptase in the serum [5]. Because mature tryptase was not detected in serum, only the total tryptase assay was performed on urine samples. The mature tryptase assay measures mature α- and β-tryptases with the B12 capture and biotin-G5 detector monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), while the total tryptase assay measures mature and proforms of α- and β-tryptases with the B12 capture and either biotin-G4 or β-galactosidase-G4 detector mAbs. Assays were performed in duplicate. Urine specimens were assayed neat and after being concentrated 10-fold using a Centricon 10 concentrator (Millipore, Billerica, Mass., USA). Exogenously added tryptase was further analyzed in urine and buffer. Tryptase purified from lung (206 μg/ml; mature β-tryptase) was diluted either in HEPES buffer (0.01 M HEPES, pH 7.4, containing 0.5 M NaCl, 25 mM EDTA, 0.1% BSA and 0.05% sodium azide) or urine. A portion of the buffer and urine samples was each concentrated 10-fold in a Microcon-10 concentrator (Millipore). The neat and 10× samples were then assayed over the range of 0.01– 1 ng per microtiter well for the 1× samples, and 0.1–10 ng per microtiter well for the 10× samples.

Results

Total (3.3 ± 3.1 ng/ml; mean ± SD) and mature (<1 ng/ml) tryptase concentrations in serum were all within the expected range for healthy persons, whereas total tryptase levels were elevated in those with systemic mastocytosis and idiopathic anaphylaxis (table 1). Total tryptase levels in neat (<1.0 ng/ml) and 10-fold concentrated specimens of urine were undetectable (<0.2 ng/ml).

Table 1.

Serum and urine tryptase concentrations

| Serum | Urine (10-fold concentrated) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| subject-sample | mature tryptase ng/ml | total tryptase ng/ml | subject-sample | mature tryptase ng/ml | total tryptase ng/ml |

| Healthy controls | |||||

| 101-2 | 1 | 1.2 | 101-1 | NT | <0.2 |

| 101-3 | 1 | 1.1 | 101-2 | NT | <0.2 |

| 104-1 | <1 | 6.1 | 104-1 | NT | <0.2 |

| 104-4 | <1 | 5.8 | 104-2 | NT | <0.2 |

| 106-2 | <1 | 1.6 | 106-1 | NT | <0.2 |

| 106-3 | <1 | 1.6 | 106-2 | NT | <0.2 |

| 107-1 | <1 | 8.0 | 107-1 | NT | <0.2 |

| 107-2 | <1 | 8.5 | 107-2 | NT | <0.2 |

| 110-2 | <1 | 2.3 | 110-1 | NT | <0.2 |

| 110-4 | <1 | 2.4 | 110-2 | NT | <0.2 |

| 111-1 | <1 | 0.5 | 111-1 | NT | <0.2 |

| 111-2 | <1 | 0.4 | 111-2 | NT | <0.2 |

| Idiopathic anaphylaxis (121) and systemic mastocytosis (122, 123) | |||||

| 121-1 | NT | 22 | 121-1 | NT | <0.2 |

| 122-1 | NT | 49 | 122-1 | NT | <0.2 |

| 123-1 | NT | 315 | 123-1 | NT | <0.2 |

NT = Not tested.

Cross-reactive material prevents mature tryptase measurement.

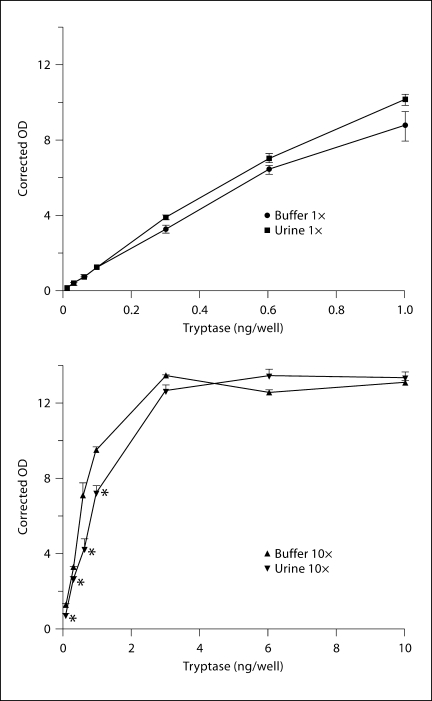

The dose-response values for tryptase added to the neat urine and buffer samples varied by less than 20% from one another. Mean values were not significantly different from one another across this dose-response range (fig. 1). When 10× urine and buffer samples were analyzed, the urine samples yielded significantly lower tryptase values from 0.1 to 1 ng per well, being anywhere from 17 to 40% lower. However, at tryptase doses greater than 1 ng per well, there were no significant differences between 10× buffer and 10× urine samples, probably because the dose-response curve had reached a plateau. Thus, concentrating urine by 10-fold increases the sensitivity to detect tryptase by 6- to 8-fold rather than 10-fold.

Fig. 1.

Effect of urine concentration on measurement of tryptase concentration. * p < 0.05 by t test corrected for number of comparisons.

Discussion

We were unable to detect the presence of tryptase in urine collected from healthy, systemic mastocytosis and idiopathic anaphylaxis subjects with normal renal function. The sensitivity of our method is 0.2 ng/ml, after 10-fold concentration of the urine, and detects both mature and proforms of α- and β-tryptases with comparable sensitivities [5]. Also, the current study did not examine urine from interstitial cystitis subjects, for whom tryptase might diffuse into the bladder lumen after being released by activated mast cells in the bladder wall nor from subjects with significant proteinuria, for whom impaired glomerular filtration may allow tryptase to pass into the urine.

In contrast, Boucher et al. [4] reported tryptase concentrations of 1.4 ± 0.7 ng/ml in spot urine samples and 0.9 ± 0.7 ng/ml in 24-hour urine specimens from healthy controls. The immunoassay used in the Boucher study is no longer available, but included G5 anti-mature tryptase mAb for capture and 125I-labeled G4 anti-tryptase mAb for detection (Tryptase RIACT; Kabi-Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J., USA). This immunoassay detects primarily mature tryptase with a sensitivity of 0.5 ng/ml. The source of the putative mature tryptase in the urine of healthy subjects in that study remains uncertain.

Degradation pathways for tryptase, particularly in the extracellular environment, are not known. Degradation products of tryptase might not be detected if the 2 epitopes being recognized in the ELISA are on separate fragments. On the other hand, a fragment that contained both epitopes would likely be detected. We have no data as to whether tryptase degradation fragments are produced in the circulation and cleared through the glomeruli. The possibility of tryptase degradation in the urine by bacteria was unlikely because tryptase was measured in spot urine collection specimens in the patients with elevated baseline serum tryptase levels. These specimens were kept frozen until analysis, thereby minimizing the likelihood of bacterial contamination which otherwise might have degraded the tryptase molecule. A possible weakness of our study is that although tryptase added to urine was shown to be detectable, we did not rule out the possibility that the integrity of the tryptase molecule might be impaired by passage through the kidney, thereby making it undetectable with the ELISA employed.

Thus, our data indicate that tryptase is not cleared from the blood into the urine in healthy subjects and in those with elevated serum tryptase levels due to underlying systemic mastocytosis or idiopathic anaphylaxis. Consequently, decreased urinary elimination of tryptase is not a likely mechanism responsible for increased serum tryptase levels in anuric persons with end-stage kidney disease [2,3]. However, it remains possible that the kidneys influence tryptase levels in the plasma by another mechanism. For example, perhaps renal insufficiency is associated with a decreased clearance of stem cell factor [2,6]. Stem cell factor is important in mast cell differentiation and survival [7], and administration of stem cell factor to human subjects causes mast cell hyperplasia and elevated levels of serum tryptase [8]. Additional work is needed to fully understand the mechanism(s) by which tryptase levels in the circulation are modulated.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by an NIH grant (AI20487) and by the Henry Ford Hospital.

References

- 1.Schwartz LB. Diagnostic value of tryptase in anaphylaxis and mastocytosis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2006;26:451–463. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brezin AL, Brezin JH, Raible DG, Schwartz LB, Schulman ES. Elevated stem cell factor and α-protryptase levels in uremia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103:S233. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dugas-Breit S, Schopf P, Dugas M, Schiffl H, Rueff F, Przybilla B. Baseline serum levels of mast cell tryptase are raised in hemodialysis patients and associated with severity of pruritus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:343–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2005.05706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boucher W, el-Mansoury M, Pang X, Sant GR, Theoharides TC. Elevated mast cell tryptase in the urine of patients with interstitial cystitis. Br J Urol. 1995;76:94–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1995.tb07840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz LB, Min HK, Ren S, Xia HZ, Hu J, Zhao W, Moxley G, Fukuoka Y. Tryptase precursors are preferentially and spontaneously released, whereas mature tryptase is retained by HMC-1 cells, Mono-Mac-6 cells, and human skin-derived mast cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:5667–5673. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitoh T, Ishikawa H, Ishii T, Nakagawa S. Elevated SCF levels in the serum of patients with chronic renal failure. Br J Haematol. 1998;102:1151–1156. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Metcalfe DD. Mast cells and mastocytosis. Blood. 2008;112:946–956. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-078097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costa JJ, Demetri GD, Harrist TJ, Dvorak AM, Hayes DF, Merica EA, Menchaca DM, Gringeri AJ, Schwartz LB, Galli SJ. Recombinant human stem cell factor (kit ligand) promotes human mast cell and melanocyte hyperplasia and functional activation in vivo. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2681–2686. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]