Abstract

Objective

We have previously reported that MAP kinase phosphatase-1 (MKP-1) is induced by thrombin and VEGF. We recently observed that EGF synergizes with thrombin to super induce MKP-1. The objective of the study was to determine the molecular mechanism underlying this synergistic response.

Methods and Results

MKP-1 induction by thrombin (~ 6 fold) was synergistically increased (~ 18 fold) by co-treatment with EGF in cultured EC. EGF alone did not induce MKP-1 substantially (< 2 fold). Synergistic induction of MKP-1 was not mediated by matrix metalloproteinases. The EGFR kinase inhibitor AG1478 blocked ~ 70% of MKP-1 induction by thrombin plus EGF (from 18 fold to 6 fold) but not the response to thrombin alone. An ERK-dependent PAR-1 signal was required for the thrombin alone effect; whereas, an ERK-independent PAR-1 signal was needed for the ~12 fold MKP-1 induction by thrombin plus EGF. VEGF-induction of MKP-1 was also ~12 fold, but JNK-dependent. Inhibitors of ERK and JNK activation blocked thrombin plus EGF-induced MKP-1 completely. Further, VEGFR-2 depletion blocked the synergistic response without affecting induction of MKP-1 by thrombin alone.

Conclusions

We have identified a novel signaling interaction between PAR-1 and EGFR that is mediated by VEGFR-2 and results in synergistic MKP-1 induction.

We have previously shown that MKP-1 is a key signaling mediator in thrombin- and vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF)-mediated activation of EC 1, 2. Further MKP-1 plays a positive role in atherogenesis in a mouse model 3. MKP-1 inactivates MAP kinases by the dephosphorylation of both threonine and tyrosine residues 4, but other substrates also exist. Recently, we have shown that MKP-1 dephosphorylates serine-10 of histone H3 5. MKP-1 has been shown to be stimulated under conditions that occur during inflammation and stress 6, 7, but multiple studies have also demonstrated MKP-1 to be an anti-inflammatory molecule 8, 9

Thrombin receptors couple to multiple G proteins and activate ERK, p38 and JNK in EC 10, 11. These signaling pathways ultimately lead to the activation of transcription factors that mediate the induction of variety of pathophysiologically important genes. Thrombin also causes transactivation of EGF receptor by tyrosine phosphorylation 12. Multiple studies have shown that thrombin and other G-protein-coupled receptors elicit their biological function, at least in part, via the transactivation of EGFR 13.

GPCRs and receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), such as EGF receptors, have been reported to be involved in the progression of a variety of diseases 14, 15. EC migration is an early event in inflammatory angiogenesis and normal vasculogenesis. Recently, we have demonstrated that MKP-1 is a key signaling mediator in VEGF-induced EC migration 2. Here we extended our study and demonstrate, for the first time, that thrombin or LPA induction of MKP-1 is synergistically increased by EGF in EC. We have elucidated the signaling mechanism responsible for the synergy and demonstrated that the VEGF receptor-2 activity is critical for the synergistic induction of MKP-1 by thrombin and EGF.

Methods

An expanded Methods section is available in the Online Data Supplement.

Methods for EC isolation and culture, Northern analysis, Real-time PCR, RNA interference and have been published previously 2, 16.

Real-time PCR assay to determine pre-mRNA of MKP-1

MKP-1-specific primers: Intron-specific forward primer (5’-AGT ACA TTT ATC TCT GGA AC-3’) and an exon-specific reverse primer (5’-CGT AGA GTG GGG TAC TGC AG-3’). Metalloproteinase inhibitor BB3103 was a kind gift from British Biotech Pharmaceuticals Ltd., U.K.

Results

Synergistic induction of MKP-1 by thrombin plus EGF

We have previously shown that thrombin induces MKP-1 in EC via protease-activated receptor-1 (PAR-1) - the predominant thrombin receptor present in human EC 1. Some PAR-1-mediated cellular events have been reported to be due to trans-activation of EGFR 17. We reasoned that if the induction of MKP-1 by thrombin was mediated by EGFR trans-activation, then EGF alone might also induce MKP-1 in EC. To test this hypothesis, we treated EC with EGF in the presence or absence of thrombin and measured MKP-1 mRNA by Northern blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 1a, EGF (16 ng/ml) treatment resulted in only a small fraction of the thrombin response; however, we observed a robust MKP-1 induction when EC were treated with thrombin and EGF in combination. We tested EGF at various concentrations ranging from 1 to 100 ng/ml and the MKP-1 expression reached a maximum response at 16 ng/ml (~2 fold, data not shown). This result ruled out the possibility that the minimal effect of EGF in MKP-1 induction in EC was due to a sub-optimal EGF concentration. As showed in Fig.1b, thrombin or EGF treatment resulted in ~ 4 or 2 fold increase, respectively, in MKP-1 message; whereas, thrombin plus EGF increased the MKP-1 message in a synergistic fashion (~12 fold). The kinetics of the response to the combined agonists was similar to that of either agonist alone (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1. Synergism in MKP-1 induction by thrombin plus EGF and Kinectics of ERK activation.

(a) Confluent cultures of umbilical vein EC (EC) were serum-starved for 2 h prior to thrombin (5 U/ml), EGF (16 ng/ml) or thrombin plus EGF at 37°C for 1 hour. Cells were lysed, and 10 μg of total RNA was subjected to Northern blot analysis using MKP-1 or ribosomal protein L-32 (RPL-32, loading control) probes. (b) Quantitative analysis of three independent experiments performed as described in (a). (c) Kinetics of MKP-1 mRNA induction by TRAP-1, EGF or TRAP-1 plus EGF was determined by quantitative real time PCR. The fold induction was quantified relative to the untreated control. (d) Kinetics of ERK activation. Western blotting was done either with phopho-ERK1/2-, ERK- or GAPDH-specific antibodies. (e) Quantification of the ERK activation from 3 separate immune blots, normalized to the GAPDH and expressed as fold induction in comparison to the untreated condition.

We also examined MKP-1 protein levels under these conditions. Since the commercial antibodies to MKP-1 were not sensitive enough to detect MKP-1 either by Western analysis or immunoprecipitation in human EC, we used mouse aortic EC. MKP-1 protein was increased by ~ 2 and 3 fold by EGF and thrombin, respectively, with an 8.0 fold increase by thrombin plus EGF (Online supplement, Fig. I). Similar to thrombin, agents such as LPA, LPC and endothelin-1 are pathophysiologically important agonists that elicit their biological effects via activation of their respective GPCRs. LPA, but not LPC or endothelin-1 increased, MKP-1 gene induction (Online supplement, Fig. II). Further, LPA plus EGF showed synergy in MKP-1 induction similar to the TRAP-1 plus EGF.

We then determined the effect of TRAP-1 alone or in combination with EGF on ERK activation (Fig. 1d & e). TRAP-1 induced a rapid but moderate activation of ERK. EGF treatment resulted in a robust activation of ERK within 5 min, peaking at 20 min (~3.7 fold) and persisting (>2 fold) for up to 180 min. The combination of TRAP-1 and EGF caused more rapid ERK dephosphorylation, as would be expected from the increased levels of MKP-1. The activation profiles of p38 and JNK by TRAP-1, EGF or EGF plus TRAP-1 were similar to ERK activation (data not shown).

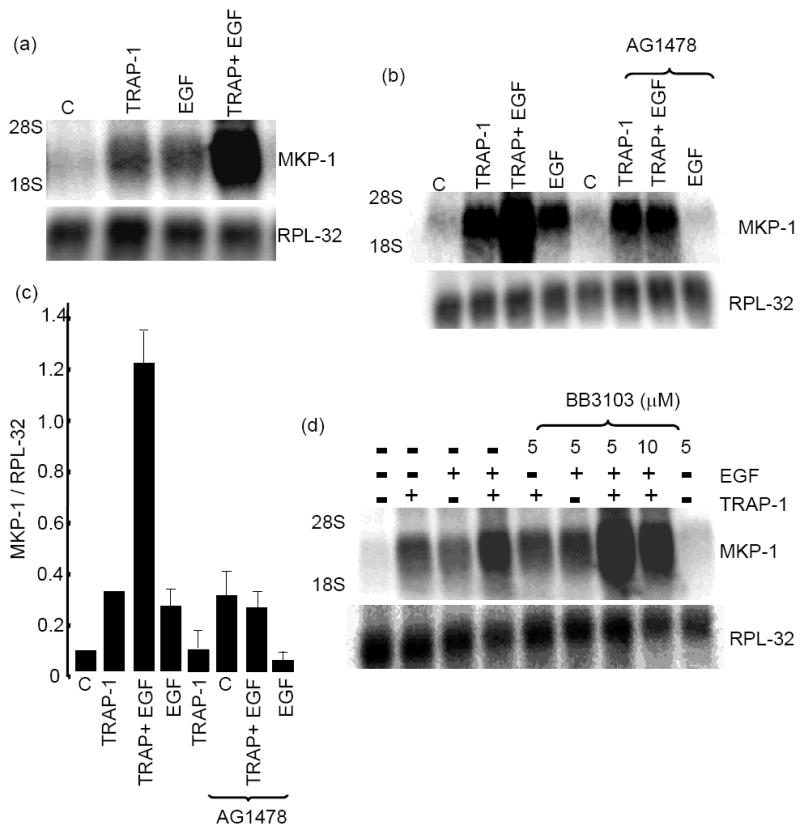

MKP-1 induction by thrombin plus EGF is protease activated receptor-1 (PAR-1)-dependent, EGF receptor kinase activity-dependent and matrix metalloproteinase independent

The synergistic induction of MKP-1 by PAR-1-specific agonistic peptide (TRAP-1; SFLLRNP) and EGF is shown Fig 2a. Peptides specific to PAR-4 (AYPGKF) or PAR-2 (SLIGKV) independently or in combination with EGF failed to induce MKP-1 induction (data not shown). AG1478, a specific EGFR kinase inhibitor completely blocked EGF-induced MKP-1; whereas, it partially blocked TRAP-1 plus EGF response. Further, AG1478 did not inhibit TRAP-1-induced MKP-1 (Fig. 2b). Quantification of multiple Northern analyses revealed that MKP-1 mRNA levels in the EGF plus TRAP-1 treated EC in the presence of AG1478 were equivalent to MKP-1 mRNA in the presence of TRAP-1 alone (Fig.2c). In the presence of AG1478, TRAP-1 plus EGF-induced MKP-1 mRNA level (~ 12 fold) was reduced to ~ 3.5 fold and the latter was equivalent to the TRAP-1 alone-mediated MKP-1 induction. These results suggest that the synergy in MKP-1 induction by thrombin plus EGF is the result of convergence of two independent signaling pathways. The combination of an AG1478-insensitive PAR-1 signal, and an AG1478-sensitive EGF receptor pathway together resulted in the synergistic induction of MKP-1.

Fig 2. MKP-1 induction by thrombin plus EGF mediated by protease activated receptor-1 (PAR-1) but matrix metalloproteinase independent.

EC were incubated at 37°C with (a) 100 μM thrombin receptor activated peptide-1 (TRAP-1; SFLLRNP), EGF (16 ng/ml) or TRAP-1 plus EGF and performed Northern blot analysis using an MKP-1 probe. (b) Effect of EGF receptor kinase inhibitor AG1478 (10 μM, 30 min pre-treatment) on MKP-1 mRNA induction (c) Quantitative analysis of three independent experiments performed as described in (b). Quantification was performed using ImageQuant software. (d) EC were pretreated (30 min) with BB3103, a specific inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase and MKP-1 mRNA levels were determined by Northern blot analysis using MKP-1 or RPL-32 probe.

GPCR-mediated matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activation releases membrane-bound EGF family of ligands, which in turn activates the EGFR13. To determine whether MMPs are involved in the synergistic induction of MKP-1, we treated EC with TRAP-1 plus EGF in the presence of BB3103 (British Biotech Pharmaceuticals, UK), a specific inhibitor of MMPs and determined MKP-1 mRNA level by Northern blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 2d, BB3103 pretreatment did not block the MKP-1 induction by TRAP-1 or EGF individually or in combination. We verified the inhibitory activity of BB3103 independently by inhibiting MMP enzyme activity in thrombin-treated cell extracts using in-gel collagen degradation (data not shown). Taken together, our results suggest that an intracellular link between the PAR-1 and EGFR signaling pathways is responsible for thrombin plus EGF-mediated synergy in MKP-1 induction.

Two distinctive PAR-1 pathways are required for the synergy in MKP-1 induction by thrombin plus EGF

PAR-1 and EGFR are known to activate src family kinases and downstream MAP kinases 2, 17. We have demonstrated previously that the src family of kinases and ERK are critical for thrombin and VEGF induction of MKP-1 in EC 1, 2. The inhibitor of Src-family of kinases, PP1 blocked both TRAP-1 and TRAP-1 plus EGF induced MKP-1 in EC (Fig. 3a). We then determined the involvement of specific Src kinase family members in the synergistic induction of MKP-1. As shown in Fig. 3b, depletion of c-Src diminished considerably the synergy portion of the induction, without blocking TRAP-1-induced MKP-1; whereas, depletion of Fyn significantly reduced both the TRAP-1- and TRAP-1 plus EGF-mediated MKP-1 induction.

Fig 3. src family of kinases and, an ERK-dependent and a second ERK-independent signal from the PAR-1 are required for thrombin plus EGF-mediated synergy in MKP-1 induction.

(a) EC were pretreated with the src kinase inhibitor PP1 (10 μM) for 30 min prior to TRAP-1 or EGF treatment and Northern blot analysis was performed using MKP-1 probe. (b) Fold change of MKP-1 mRNA (quantified by Q-PCR) in presence of c-Src-or Fyn-specific siRNA. Efficiency of the siRNAs is shown by Western blot using C-Src- or Fyn-specific antibodies. (c) Effect of ERK activity on MKP-1 induction measured by Northern analysis (d) Quantitative analysis of three independent experiments performed as described in (c) and normalized with the RPL-32 RNA signal.

ERK inhibitor PD98059 prevented TRAP-1 induction of MKP-1; whereas, it only partially inhibited TRAP-1 plus EGF induced MKP-1, and did not inhibit at all induction of MKP-1 by EGF (Fig. 3c). In the TRAP-1 plus EGF group, the reduction in the amount of MKP-1 mRNA by PD98059 (~12 fold induction was reduced to ~9 fold in presence of PD98059) was similar to the level of MKP-1 mRNA induced by TRAP-1 alone (~3.5 fold, Fig. 3d). These results suggest that two distinct signals, one ERK-dependent and one ERK-independent, from the PAR-1 receptor were required for the synergy in MKP-1 induction.

Synergy in MKP-1 induction by thrombin plus EGF is at the transcriptional level

We have shown earlier that thrombin induction of MKP-1 is at the transcriptional level 1. Synergistic induction of MKP-1 mRNA in the presence of EGF could be due to mRNA stabilization or increased transcription. We tested for a change in mRNA stability by treating EC either with vehicle, TRAP-1, EGF or TRAP-1 plus EGF for 1 h followed by treating actinomycin D. As shown in Fig 4 (a), compared to the control condition, TRAP-1, EGF or TRAP-1 plus EGF caused no significant change in the half-life of MKP-1 mRNA. In a complementary approach, we measured the un-spliced form of the MKP-1 transcript (MKP-1 pre-mRNA) by quantitative real-time PCR using an intron-specific forward primer and an exon-specific reverse primer. At one hour, TRAP-1 and EGF up-regulated MKP-1 pre-mRNA ~5-fold and 3-fold, respectively; whereas, TRAP-1 plus EGF showed a ~12-fold increase in MKP-1 pre-RNA (Fig. 4b). This relative increase in the abundance of pre-mRNA by TRAP-1 plus EGF points to an increase in the transcriptional rate.

Fig 4. Thrombin plus EGF did not stabilize MKP-1 mRNA but increased the MKP-1 pre-mRNA abundance.

(a) EC treated with either with vehicle, TRAP-1, EGF or EGF plus TRAP-1 for 1 h and then treated with actinomycin D (10 μg/ml) for an additional 3 h and MKP-1 mRNA level was measured after Northern blot analysis. (b) Relative MKP-1 pre-mRNA abundance was determined by real-time PCR as described in the “methods”.

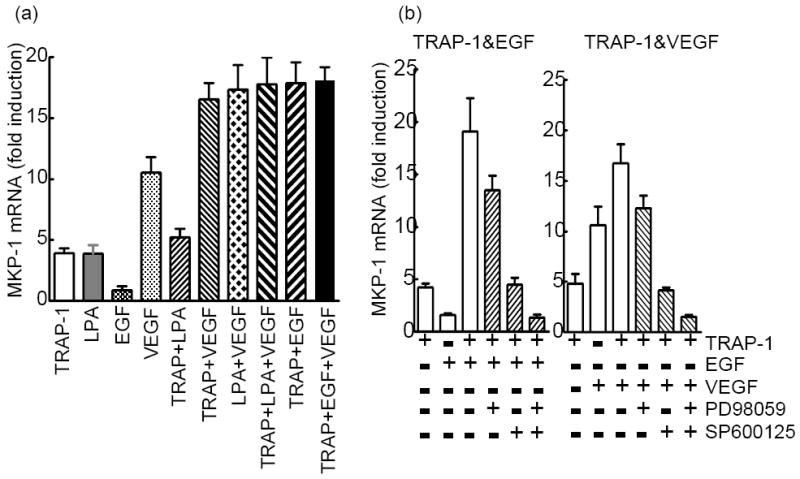

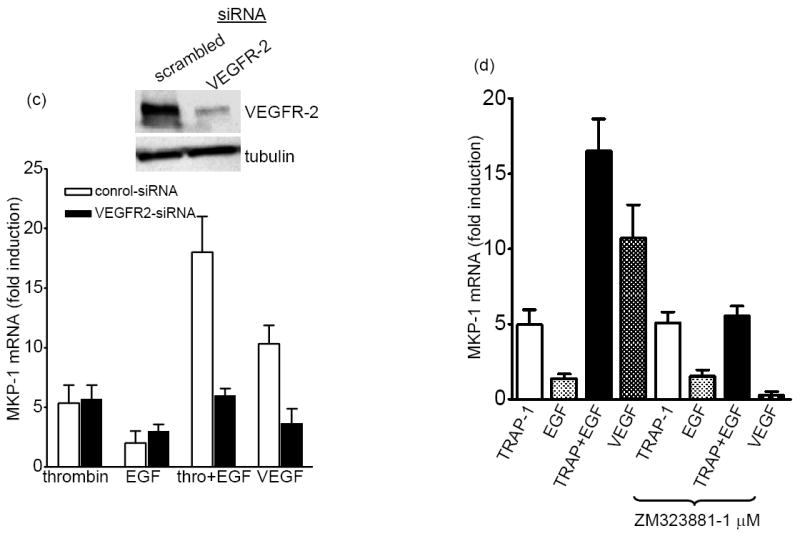

Synergistic induction of MKP-1 by thrombin plus EGF requires VEGF receptor- 2

Earlier we have reported that VEGF induces MKP-1 more effectively than thrombin in EC 2. Here we determined the effect of VEGF on TRAP-1, LPA and/or EGF on MKP-1 induction. We identified an additive effect in MKP-1 induction when cells where treated with TRAP-1 or LPA in the presence of VEGF (Fig. 5a). TRAP-1 or LPA induction of MKP-1 was ~ 5 fold, VEGF alone ~12 fold; whereas, thrombin or LPA plus VEGF induction was ~ 17 fold. Further, this additive effect was similar in quantity to the synergistic effect induced by TRAP-1 plus EGF (17 fold). VEGF did not augment TRAP-1 plus EGF induction of MKP-1. TRAP-1 plus LPA induction was similar to either of them alone suggesting overlapping signaling pathways from the thrombin receptor and the LPA receptor in MKP-1 induction.

Fig 5. Synergistic induction of MKP-1 by thrombin plus EGF requires VEGF receptor-2.

EC were treated with TRAP-1, EGF, LPA (50μM), or VEGF-A165 (10ng/ml) alone or in combinations without (a) or with (b) inhibitors of ERK or JNK activation. (c) EC were transfected with VEGFR-2-specific siRNA or scrambled siRNA (control siRNA). 36 h later cells were treated with agonists. (d) EC were pretreated with VEGFR-2 inhibitor ZM323881 (Tocris bioscience, MO), (e) pre-treated with control goat IgG or anti-VEGF antibody (0.2μg/ml) 30 min prior to agonists’ treatment and MKP-1 mRNA was measured by real-time PCR. Inset of Fig.1c shows the efficacy of VEGFR-2 depletion by a VEGFR-2-specific siRNA by immune blot.

JNK, not ERK, activation was critical for VEGF induction of MKP-12. Since VEGF induction was similar to the ERK-independent thrombin plus EGF-mediated MKP-1 induction (~12 fold), we next determined the role of JNK in thrombin plus EGF-induced MKP-1. As shown in Fig. 5b, a JNK inhibitor blocked most of the observed synergy, and the uninhibited portion was equivalent to the ERK-dependent thrombin induction. Simultaneous inhibition of both the ERK and JNK pathways blocked the synergistic effect almost completely. In a corollary experiment, TRAP-1 plus VEGF-induced MKP-1 was blocked completely by ERK and JNK inhibitors. ERK or JNK inhibitors brought the level of MKP-1 induction down to the thrombin or VEGF alone levels, respectively.

Using specific neutralizing antibodies to various VEGF receptors, we have previously demonstrated that VEGF receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) is responsible for VEGF-induced MKP-1 induction 2. Therefore next we tested the role of VEGFR-2, if any, in MKP-1 induction by thrombin plus EGF. The synergistic induction of MKP-1 by TRAP-1 plus EGF was substantially reduced in the VEGFR-2-depleted cells, using VEGFR-2-specific siRNA (Fig.5c). VEGFR-2 depletion did not alter MKP-1 induction by TRAP-1 alone. Further, the VEGFR-2 kinase inhibitor ZM323881 showed similar results as it blocked the synergistic MKP-1 induction, but not the TRAP-1 alone induction (Fig. 5d). Taken together, our results indicate that VEGFR activation is one of the downs stream events to our identified ERK-independent pathway. Previous studies in other cell types have demonstrated vegf gene expression by EGF and, the secreted VEGF activated the VEGFR in an autocrine fashion 18. Earlier we have shown that among the various VEGF isotypes only VEGF-A induces MKP-12. In Fig. 5e, a neutralizing antibody specific to VEGF-A did not block thrombin plus EGF-induced MKP-1, suggesting that the mechanism of VEGFR activation is not due to secreted VEGF-A and the subsequent autocrine activation of VEGFR. We failed to co-immunoprecipitate EGFR and VEGFR-2 in the presence or absence of agonists, though we believe our conditions were appropriate because we successfully co-immunoprecipitated a different heterologous membrane receptor pair – EGFR and HER2 (not shown). These results suggest that the synergistic induction of MKP-1 was not the result of EGFR and VEGFR-2 heterodimerization.

TRAP-1 plus EGF-mediated gene regulation and EC migration

We have previously reported that ERK activation is required for thrombin induction of PDGFA, E-selectin and VCAM-1; whereas, PDGFB induction was negatively regulated by ERK activity1. We now demonstrate that the combination of TRAP-1 and EGF results in a lesser level of induction of PDGFA, E-selectin and VCAM-1 in comparison to TRAP-1 alone; whereas, PDGFB induction was further increased when EC were treated with TRAP-1 in combination with EGF (Online supplement data, Table I). The changes were largely unaffected by ERK inhibition, which is likely due to the fact that the increased MKP-1 has already reduced ERK activity.

Recently, using in vitro assays, we have demonstrated a positive role of MKP-1 in VEGF-induced EC migration and angiogenesis 2. In a trans-well assay system, TRAP-1 plus EGF caused a greater level of EC migration compared to either agonist alone. (Fig. 6a). The average increase in EC migration induced by TRAP-1 alone was moderate (< 2 fold) and EGF alone yielded ~ 4 fold increase (p < 0.05, Fig. 6b); whereas, TRAP-1 plus EGF treatment resulted in an ~ 8 fold increase (p < 0.01). MKP-1 depletion using a specific siRNA blunted TRAP-1-stimulated EC migration, but had no significant effect on the response to EGF (Fig. 6c). MKP-1-specific siRNA diminished TRAP-1 plus EGF-induced cell migration to the level equivalent to that of EGF alone (from ~ 8 to ~ 4 fold, p < 0.01). Thus, PAR-1 or PAR-1 plus EGFR-mediated EC migration is critically dependent on MKP-1 activity; whereas, EGF alone-induced migration is MKP-1-independent.

Fig 6.

EC were seeded at (on the upper chamber of an 8.0-micron diameter pore membrane chamber (104 cells/membrane). Agonists’ were added to the bottom well of the appropriate chambers and incubated at 37°C overnight in a CO2 incubator and processed as described in the “methods”. (a) The white small circles are the pores and the migrated cells are seen as multi-shaped black structures. (b) Fold increase in EC migration induced by TRAP-1, EGF or TRAP plus EGF. Migrated cells in the controls were 105 ± 17. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, relative to the control. (c) Effect of MKP-1-specific siRNA on EC migration. The assays were performed in triplicates. Statistical significance *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Discussion

We have recently reported on the induction of MKP-1 by thrombin or VEGF by distinct pathways and the role of this dual-specificity phosphatase in EC gene expression and migration 1, 2. Here, we report that thrombin or LPA treatment with EGF resulted in the synergistic induction of MKP-1 in EC. This strong induction of MKP-1 has significant implications in vascular homeostasis and diseases since MKP-1 and such agonists as thrombin, LPA, VEGF or EGF and their cognate receptors are known to be present in the vessel wall during development and under various injury or chronic disease conditions, such as atherosclerosis 3, 19-22.

The receptors for thrombin, LPA, LPC and endothelin-1 are GPCRs and have been shown to induce both in common and distinct signaling pathways and elicit sometimes similar and sometimes distinctive biological end points23. Here, we have demonstrated that MKP-1 induction was restricted to thrombin and LPA, and not LPC or endothelin-1. Furthermore, signaling pathways to induce MKP-1 by thrombin or LPA and either one of them with EGF were similar (Online supplement, Table II) suggesting that MKP-1 is a prototypical example of common signaling end points of the thrombin and LPA receptors.

Two mechanisms have been put forward to explain the signaling cross-talk between GPCRs and receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs). Prenzel, et al; showed evidence that GPCR activation led to metalloproteinase-mediated EGFR ligand release from the EC surface, leading to activation of the EGFR in an autocrine or paracrine manner 24. Alternatively, upon GPCR activation, src family of proteins or G-protein subunits may physically interact with the cytosolic domain of EGFR resulting in the triggering of the downstream EGFR signaling cascade 25, 26. In this study, we have shown, a novel, metalloproteinase activity-independent, but EGF-dependent, signaling interaction between the thrombin or the LPA receptor and EGFR resulting in MKP-1 induction in EC. We identified a requirement for both ERK-dependent and an ERK-independent pathways originating from the activated GPCR for the full induction of MKP-1 when EC are treated with thrombin or LPA plus EGF. The synergy in MKP-1 induction by thrombin/LPA plus EGF is due to the net effect of such converging signals. In the classical MAP kinase pathway, the src family of kinases are upstream to Raf, Ras, MEK and ERK and our inhibitor studies suggest this pathway is responsible for the thrombin or LPA induction of MKP-1 27. The ERK-independent pathway responsible for the synergy is more complex. We determined that JNK activity and VEGFR-2 are involved in the ERK-independent pathway. We have previously shown that JNK is a downstream signaling intermediate in VEGF-induced MKP-1 induction 2. EGFR activation was shown to induce vegf gene expression and secretion 28. However, a neutralizing antibody to VEGF-A, the only VEGFR-ligand capable of inducing MKP-1 2 in EC, did not prevent thrombin plus EGF-induced MKP-1. Further, the ERK-independent pathway from thrombin receptor alone is not sufficient to induce MKP-1; a signaling component from EGFR is also required. Taken together, we believe, the ERK-independent pathway induced by thrombin plus EGF converges at VEGFR intracellularly resulting in MKP-1 induction. Signaling interactions between GPCRs and various RTKs and are well known. Recently, Greenberg et al have demonstrated that activated VEGFR blocks PDGFB receptor activity and PDGF-induced neovascularization 29. To our knowledge, signaling interactions between a GPCR, EGFR and VEGFR resulting in the transcriptional activation of a gene has not been reported. Further, our results emphasize the significance of interplay among the bioactive molecules in the vascular microenvironment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Lori Mavrakis, Angela Money, Emily Tillmaand and Lisa Dechert for technical assistance.

Sources of funding - NIH Grant HL29582 (PED) supported this study. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells were harvested through the Birthing Services Department at the Cleveland Clinic and the Perinatal Clinical Research Center (NIH Research Center award RR-00080) at the Cleveland Metrohealth Hospital.

Footnotes

Disclosure - None

References

- 1.Chandrasekharan UM, Yang L, Walters A, Howe P, DiCorleto PE. Role of CL-100, a dual specificity phosphatase, in thrombin-induced endothelial cell activation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:46678–46685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406441200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinney CM, Chandrasekharan UM, Mavrakis L, DiCorleto PE. VEGF and thrombin induce MKP-1 through distinct signaling pathways: role for MKP-1 in endothelial cell migration. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C241–250. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00187.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen J, Chandrasekharan UM, Ashraf MZ, Long E, Morton RE, Liu Y, Smith JD, DiCorleto PE. Lack of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 protects ApoE-null mice against atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 106:902–910. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.198069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keyse SM. Protein phosphatases and the regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:186–192. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kinney CM, Chandrasekharan UM, Yang L, Shen J, Kinter M, McDermott MS, Dicorleto PE. Histone H3 as a novel substrate for MAP kinase phosphatase-1. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;296:C242–249. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00492.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lasa M, Abraham SM, Boucheron C, Saklatvala J, Clark AR. Dexamethasone causes sustained expression of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) phosphatase 1 and phosphatase-mediated inhibition of MAPK p38. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7802–7811. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.7802-7811.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Y, Gorospe M, Yang C, Holbrook NJ. Role of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase during the cellular response to genotoxic stress. Inhibition of c-Jun N-terminal kinase activity and AP-1-dependent gene activation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:8377–8380. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao Q, Wang X, Nelin LD, Yao Y, Matta R, Manson ME, Baliga RS, Meng X, Smith CV, Bauer JA, Chang CH, Liu Y. MAP kinase phosphatase 1 controls innate immune responses and suppresses endotoxic shock. J Exp Med. 2006;203:131–140. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammer M, Mages J, Dietrich H, Servatius A, Howells N, Cato AC, Lang R. Dual specificity phosphatase 1 (DUSP1) regulates a subset of LPS-induced genes and protects mice from lethal endotoxin shock. J Exp Med. 2006;203:15–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coughlin SR. Thrombin signalling and protease-activated receptors. Nature. 2000;407:258–264. doi: 10.1038/35025229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moolenaar WH, van Meeteren LA, Giepmans BN. The ins and outs of lysophosphatidic acid signaling. Bioessays. 2004;26:870–881. doi: 10.1002/bies.20081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daub H, Weiss FU, Wallasch C, Ullrich A. Role of transactivation of the EGF receptor in signalling by G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. 1996;379:557–560. doi: 10.1038/379557a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Natarajan K, Berk BC. Crosstalk coregulation mechanisms of G protein-coupled receptors and receptor tyrosine kinases. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;332:51–77. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-048-0:51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohtsu H, Dempsey PJ, Frank GD, Brailoiu E, Higuchi S, Suzuki H, Nakashima H, Eguchi K, Eguchi S. ADAM17 mediates epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation and vascular smooth muscle cell hypertrophy induced by angiotensin II. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:e133–137. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000236203.90331.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pai R, Soreghan B, Szabo IL, Pavelka M, Baatar D, Tarnawski AS. Prostaglandin E2 transactivates EGF receptor: a novel mechanism for promoting colon cancer growth and gastrointestinal hypertrophy. Nat Med. 2002;8:289–293. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu W, Chandrasekharan UM, Bandyopadhyay S, Morris SM, Jr, DiCorleto PE, Kashyap VS. Thrombin induces endothelial arginase through AP-1 activation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 298:C952–960. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00466.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prenzel N, Fischer OM, Streit S, Hart S, Ullrich A. The epidermal growth factor receptor family as a central element for cellular signal transduction and diversification. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2001;8:11–31. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0080011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakai K, Yoneda K, Moriue T, Igarashi J, Kosaka H, Kubota Y. HB-EGF-induced VEGF production and eNOS activation depend on both PI3 kinase and MAP kinase in HaCaT cells. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;55:170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rother E, Brandl R, Baker DL, Goyal P, Gebhard H, Tigyi G, Siess W. Subtype-selective antagonists of lysophosphatidic Acid receptors inhibit platelet activation triggered by the lipid core of atherosclerotic plaques. Circulation. 2003;108:741–747. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000083715.37658.C4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Major CD, Santulli RJ, Derian CK, Andrade-Gordon P. Extracellular mediators in atherosclerosis and thrombosis: lessons from thrombin receptor knockout mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:931–939. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000070100.47907.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dreux AC, Lamb DJ, Modjtahedi H, Ferns GA. The epidermal growth factor receptors and their family of ligands: their putative role in atherogenesis. Atherosclerosis. 2006;186:38–53. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holm PW, Slart RH, Zeebregts CJ, Hillebrands JL, Tio RA. Atherosclerotic plaque development and instability: a dual role for VEGF. Ann Med. 2009;41:257–264. doi: 10.1080/07853890802516507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.New DC, Wong YH. Molecular mechanisms mediating the G protein-coupled receptor regulation of cell cycle progression. J Mol Signal. 2007;2:2. doi: 10.1186/1750-2187-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prenzel N, Zwick E, Daub H, Leserer M, Abraham R, Wallasch C, Ullrich A. EGF receptor transactivation by G-protein-coupled receptors requires metalloproteinase cleavage of proHB-EGF. Nature. 1999;402:884–888. doi: 10.1038/47260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dhanasekaran DN. Transducing the signals: a G protein takes a new identity. Sci STKE. 2006;2006:31. doi: 10.1126/stke.3472006pe31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schauwienold D, Sastre AP, Genzel N, Schaefer M, Reusch HP. The transactivated epidermal growth factor receptor recruits Pyk2 to regulate Src kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:27748–27756. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801431200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marshall CJ. Specificity of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling: transient versus sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Cell. 1995;80:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Redondo P, Jimenez E, Perez A, Garcia-Foncillas J. N-acetylcysteine downregulates vascular endothelial growth factor production by human keratinocytes in vitro. Arch Dermatol Res. 2000;292:621–628. doi: 10.1007/s004030000187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greenberg JI, Shields DJ, Barillas SG, Acevedo LM, Murphy E, Huang J, Scheppke L, Stockmann C, Johnson RS, Angle N, Cheresh DA. A role for VEGF as a negative regulator of pericyte function and vessel maturation. Nature. 2008;456:809–813. doi: 10.1038/nature07424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.