Abstract

Gender-based violence rooted in norms, socialization practices, structural factors, and policies that underlie men's abusive practices against married women in India is exacerbated by alcohol. The intersection of domestic violence, childhood exposure to alcohol and frustration, which contribute to drinking and its consequences including forced sex is explored through analysis of data obtained from 486 married men living with their wives in a low-income area of Greater Mumbai. SEM shows pathways linking work-related stress, greater exposure to alcohol as a child, being a heavy drinker, and having more sexual partners (a proxy for HIV risk). In-depth ethnographic interviews with 44 married women in the study communities reveal the consequences of alcohol on women's lives showing how married women associate alcohol use and violence with different patterns of drinking. The study suggests ways alcohol use leads from physical and verbal abuse to emotional and sexual violence in marriage. Implications for gendered multi-level interventions addressing violence and HIV risk are explored.

Keywords: Domestic violence, Alcohol, HIV/AIDS

Introduction

The co-occurrence of alcohol abuse and domestic violence including forced sex within marriage in India is widely acknowledged [1, 2]. Domestic violence is widespread across classes and regions in India [3–5], although it is more prevalent among less well educated women [6], poor women, and women in situations that magnify gender inequalities such as income, age, or educational differentials [7–10]. Domestic violence is deeply rooted in gender-based norms, socialization practices, structural factors and policies that discriminate against women [11, 12] and which underlie and endorse or ignore men's abusive practices against women. It is a widely-held belief that alcohol contributes to disinhibition, mood enhancement, and alcohol myopia in men [13]. Specifically with respect to intimate partner violence, alcohol disinhibits men from engaging in restraint in contexts in which it is socially and culturally acceptable to engage in verbal or physical abuse against their spouse as well as to exhibit risky sexual behaviors such as inconsistent condom use and having multiple extramarital sexual partners [14, 15]. Indirectly, as a mood enhancer, alcohol can also increase existing feelings of anger and frustration. Thus, men's perception of women's failure to comply with gender-based norms around household practice and public performance can be exacerbated by alcohol myopia, which may focus attention on women as an immediate and vulnerable target. Intimate partner violence rises in the context of alcohol use [16]. Analysis of data from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS3) concluded that among married Indian women, husband's physical violence combined with sexual violence was associated with an increased prevalence of HIV infection [17]. While some studies indicate a direct link between intimate partner violence, alcohol and HIV risk [18, 19], others suggest that the relationship is more nuanced, impacted by number of sexual partners, childhood exposure to violence and substance use, and further complicated by gender and contextual sexual decision-making [20]. Women who are socially, culturally and economically dependent and subordinate to their sexual partners have limited ability to negotiate whether and when to have sex and/or use condoms or other forms of protection [21, 22].

Prevailing norms of masculinity and femininity reinforce risk behaviors [23]. Men wish to appear knowledgeable about sexual matters, while women often engage in a “culture of silence”, unwilling to express their needs and desires for fear that they might be perceived as too sexually aggressive. Finally, location of drinking has also been identified as a factor that affects behavior. Heavy drinking in bars is often associated with aggression and violence [24], which may shift later to the home which provides drinking men a cover for intimate partner violence [25]. These complexities call for an ecological framework to guide research design, qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis that seeks to understand how personal history, the micro-, exo- and macrosystem factors pattern and conspire in facilitating the initiation and continuation of acts of violence, alcohol abuse and consequent sex risk and HIV/AIDS exposure [26]. As previously mentioned, the literature suggests that childhood experiences, gender norms, alcohol use and violence increase the potential for HIV and other sex risk. This paper uses data from both married men and women concurrently to explore the linkages and associations among these variables.

Methods

Our study took place in three geographically proximate low-income communities in a western section of the Greater Mumbai metropolitan area known as Navi Mumbai. We use a mixed methods approach to examine the relationship among and potential pathways linking alcohol consumption, domestic violence and HIV/AIDS risk. ANOVAs and structural equation modeling are used to analyze survey data gathered from married men that includes their drinking patterns, reports of violence against family members, and sexual risk behavior. We combine results from our survey of men with content analysis of observational and interview data gathered from married women in the same communities who reported that their husbands' drinking affected them and their families. In this way we can provide deeper and more descriptive understanding about the context and pathways leading to alcohol abuse, sex risk and domestic violence.

ASHRA (Alcohol, Sexual Health Risk and AIDS prevention among men in low income communities, Mumbai) data were gathered by surveying randomized cluster sample of 1239 men ages 18–29 living in three low-income communities in Navi Mumbai (see papers by Singh et al., and Cromley et al. in this issue for a description of the sampling protocol). This sample included 492 unmarried men (including 19 who were widowed, separated or divorced), 486 married men living with their wives, and 261 married men living apart from their wives.

Measures

Table 1 presents a description of the scales, indices and variables used in these analyses including: (a) a work-related stress scale; (b) a scale measuring the respondent's relationship with his wife; (c) an index of childhood exposure to alcohol, and (d) a scale measuring the violence-related consequences of alcohol use on the respondent's relationships.

Table 1.

Scales, indices, and variables used in the quantitative analyses

| Variable name | Number of items | Alpha | Description | Response categories |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work stressa,b,c | 6 | .68 | A scale measuring work-related stress which includes questions regarding time demands, tension, boredom, anger and frustration | Strongly disagree, disagree, agree, and strongly agree |

| Relationship with wifea,b,d | 6 | .72 | A scale measuring the respondent's relationship with his wife including questions about communications, understanding, sharing opinions and listening | Never, sometimes, and always |

| Childhood exposurea,b,e | 3 | An index measuring childhood exposure to alcohol which explored how often parents, siblings and other relatives drank | Never, rarely, sometimes, and often | |

| Violencea,b,f | 9 | .79 | A scale measuring violence-related consequences of alcohol use on relationships in the past three or 6 months. Questions focused on verbal and physical violence exhibited towards spouse and/or children | Never, sometimes, and often |

| Age difference | – | – | Used the difference in age between husband and wife at the time of marriage | |

| Partners | – | – | Indicated the number of sexual partners that a married man had in addition to his wife | |

| AlcTotal | – | – | The amount of alcohol consumed in the past 30 days measured in liters | |

| Social drinkers | – | – | Defined as individuals who typically have one or two drinks on days in which they drink | |

| Overindulgent drinkers | – | – | Defined as individuals who drink once a week or less and have three or four drinks or more on a typical day when they are drinking | |

| Heavy drinkers | – | – | Defined as individuals who drink two or three times a week or more and have three or four drinks or more on a typical day when they are drinking |

Scales and indices were transformed to range from 0 to 10. Higher scores represented greater levels of work-related stress, having a better relationship with wife, have more exposure to alcohol as a child, and having more severe violence-related consequences of alcohol use on relationships

For the following scales: Relationship with wife, Work stress, and Childhood exposure, less than four respondents had answered only some of the constituent questions. These respondents were coded as “missing” for these variables. The violence scale was initially calculated as the mean of all items, such that the denominator (total n) was equal to the total number of questions answered by the respondent. In this way, the total number of questions answered by the respondent was controlled for

This scale consisted of the following components: The work you do is very time demanding; The work you do makes you feel bored; The work you do demands a lot of physical hard work; The work you do involves lot of tension; The work you do makes you feel frustrated; The work you do makes you feel angry

This scale consisted of the following components: Your wife understands your moods; Your wife listens to your suggestions; Your wife is sympathetic to your problems; Your wife asks your opinions on different issues; You discuss freely about sex with your wife; You share your feelings freely with your wife

This index included the following components: Your parents used to drink alcohol; At least one of your brothers or sisters used to drink alcohol; At least one of your other relatives used to drink alcohol

This scale consisted of the following components: You yelled at a woman close to you; You yelled at your wife (or girlfriend); You hit a woman close to you; You hit your wife (or girlfriend); You hit a sibling, a parent or another member of your family; You yelled at a child in your family; You yelled at your child; You hit a child in your family; You beat/hit your child

Other variables included in the quantitative analyses include: (a) whether the respondent was born in or outside of Mumbai, (b) number of sexual partners, (c) age discordance between husband and wife (a proxy for power differential), and (d) drinking-related variables including: total amount of pure alcohol in liters drunk in the past 30 days; and pattern of drinking, defined as social drinking, overindulgent drinking, and heavy drinking.

The objective of our women's substudy which explores the intersection of alcohol and sex risk among married women in the study communities is to understand the many ways (e.g. economic, social/relational, emotional, physical) that alcohol affects the lives of women whose husbands use or abuse alcohol. By eliciting their stories and discovering the variety of ways that women cope and actively empower themselves by drawing on their own, family, peer, organizational, religious and political resources and mobilization, we seek to generate information and suggestions for culturally responsive intervention strategies.

Measures used to collect qualitative data include:

A chronological time line constructed to assist in gathering data that would allow for analysis of the progression of alcohol abuse and domestic violence both before and during marriage.

An ecological model that asked women to identify risk and protective factors at the individual, peer, family, community and policy levels.

Narratives of recent “critical events” defined as encounters that involved some form of force to engage in an activity, or verbal, emotional, physical or sexual abuse or violence. Two such critical events were gathered from each respondent, one in which alcohol was used by the man before or during the event and another where alcohol was not used by the man before or during the event. In those cases where the husband drank all the time, interviewers were instructed to discuss two different events when alcohol was used.

Data Analysis

For the analyses presented in this paper on the relationship between domestic violence, alcohol use and sexual risk we first focus on the subsample of married men living with their wives in the study communities. Data were analyzed quantitatively using ANOVA and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM).

Qualitative data were gathered through in-depth interviews with 44 women who came forward with stories of the effects of husband's alcohol use on their lives. These women were older than the wives of married men in the survey sample and had suffered for longer periods of time from the effects of their husbands' drinking. Their mean age was 29 and they had been married on average 14.4 years. Women were young when married ranging in age from 8 to 20 with the mean age at marriage being 14 years old,1 younger than the wives of men in the general sample by three years. They had less education (2.9 years) and more children (M = 3.5) than the wives of men in survey subsample. More than half of these women (52%) worked outside of the home. Comparable to the male sample, 32% lived in nuclear families; however, 68% lived in joint households rendering them more subject to influences from their husband's parents and relatives.

These demographic data indicate that the women who experience severe negative effects of alcohol use and violence are older and further along the continuum of living with the effects of their husband's problem drinking behavior than the majority of the wives of married men in the survey sample. Nonetheless, they come from the same communities and their histories and stories provide insight into the way drinking, violence and sexual risk emerge, develop and intersect over time.

Most interviews required several meetings with the women. This reflected both the trust-building process and the constraints of interviewing in the community environment. For example, we could not identify an acceptable community location for confidential interviewing so interviews were conducted in women's homes, which also afforded limited privacy. In several instances interviews were interrupted or cut short due to the presence of children or other family members, work obligations or the need to care for children or family members and had to be continued at other times when women were less burdened or less likely to be interrupted.

Field notes, key informant interviews and individual level interviews were transcribed, translated into English and entered into ATLAS Ti for analysis. Using codes developed by the Indo–U.S. research team, the Indian field researchers completed first level coding. Codes were then combined and reorganized to examine the interrelationships among variables such as patterns of alcohol use and various forms of violence in order to develop groupings or clusters of similar cases based on combinations of these variables.

Results

Results of Survey Data Analysis with Male Respondents

Demographic data indicate that the average age of married men living with their wives was 25.9 years old and the mean age of the wife was 22.5 years. The average age of marriage was 21 for men, and 17 for women. The education levels of both husbands and wives were low: 6.2 years and 4.6 years of education respectively. Only 12% of women worked, and of this small group most (82%) worked outside of the home. Of the 747 currently married men in the survey including both those living with their wives and those living apart, 265 (35.5%) lived in nuclear families; 267 lived in extended families (35.7%) and 215 (28.8%) lived in all male households. These married couples, relatively young and in the early stages of their family careers, had an average of 1.6 children per couple.

ANOVA was used to identify differences in domestic violence by pattern of drinking. The level of domestic violence varies significantly by pattern of drinking, F(2,424) = 25.881, p < .001, with heavy drinkers being more apt to engage in domestic violence than social or overindulgent drinkers. Significant differences in the mean level of domestic violence were found between social drinkers (M = .399) and heavy drinkers (M = 2.578), p < .01, as well as between overindulgent drinkers (M = .732) and heavy drinkers (M = 2.578), p < .01.2 Mean scores on the domestic violence scale, which measures verbal and physical abuse towards wives and children as a consequence of drinking, were 3.5 times higher for heavy drinkers compared to overindulgent drinkers and 6.5 times higher for heavy drinkers when compared to social drinkers.

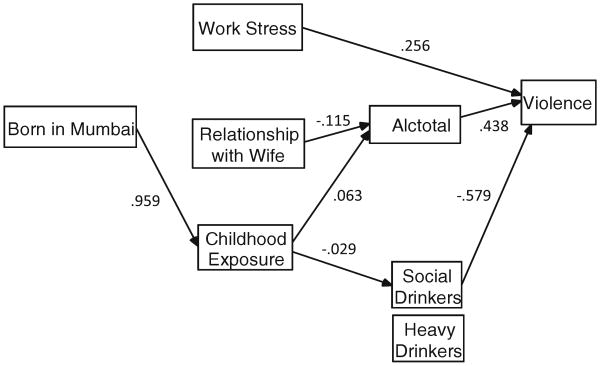

Although the severity of domestic violence did not vary by whether men drank at home or in more public settings [F(1,422) = .105, p = .746], we predicted that location of drinking would be an important mediator of domestic violence. We used structural equation modeling (SEM) to explore this issue. An initial multiple group comparison was run comparing respondents who primarily drank at home with respondents who drank at other locations, including bars, restaurants, friend's homes, and other public places.3 After the initial model was run, it was trimmed by removing paths that were not significant at the .05 alpha level and the model was rerun. Next, variables that did not have a significant direct or indirect effect on domestic violence were removed and correlations between errors were added to improve model fit.4 This finalized model was found to have excellent model fit with Chi-square/df of 1.090, CFI of .995, and RMSEA of .021. The structural equation model shown in Fig. 1 illustrates the findings for respondents who primarily drink at home.

Fig. 1.

Pathways among risk factors, alcohol and violence for respondents who drink at home

Three variables: (1) amount of alcohol consumed, (2) stress and (3) being a social drinker had a significant direct effect5 upon domestic violence among respondents who drank primarily at home. Here the total effect of each of these variables on level of domestic violence is equal to the direct effect. Each additional liter of alcohol consumed predicted an increase of .438 on the domestic violence scale. Similarly, an increase of one unit on the work-related stress scale predicted a .256 increase on the domestic violence scale. Conversely, being a social drinker predicted a lower score on the domestic violence scale (−.579) as compared to being an overindulgent drinker.

Respondents' relationship with their wives was also related to domestic violence indirectly through the amount of alcohol consumed. Having a more positive relationship with one's wife was related to a lower level of alcohol use, which in turn was related to a decreased impact of alcohol use on domestic violence. Overall, a positive relationship with wife was negatively related to domestic violence; with each unit increase on the “relationship with wife scale” (indicating a more positive relationship), there was a corresponding .05 unit decrease in domestic violence. A second indirect path was found related to place of birth, which was related to domestic violence indirectly through childhood exposure to alcohol, amount of alcohol consumed, and a pattern of social drinking. Being born in Mumbai was associated with a .042 unit increase in the domestic violence scale. Next, childhood exposure to alcohol was found to be related to domestic violence indirectly through alcohol consumption and social drinking. In calculating the overall impact of childhood exposure, we found a one-unit increase in childhood exposure to alcohol to be associated with a .044 unit increase in the domestic violence scale.

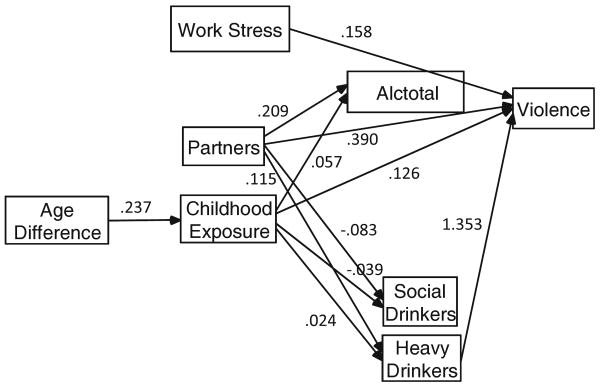

A second structural equation model includes only respondents who reported drinking in locations other than their home most of the time (see Fig. 2). Again the initial model was run and trimmed by removing non-significant paths. Correlations between some of the errors were added to improve model fit. The finalized model, shown below, has an excellent model fit with a Chi-square/df of 1.372, CFI of .983, and RMSEA of .041.

Fig. 2.

Pathways among risk factors, alcohol and violence for respondents who drink in public places

Direct effects, which were associated with higher scores on the domestic violence scale, included: (1) higher work-related stress, (2) greater exposure to alcohol as a child, (3) being a heavy drinker as compared to an overindulgent drinker, and (4) having a greater number of partners over and above that of one's wife (a proxy for HIV risk). A one-unit increase in the work stress scale was associated with a .158 unit increase in domestic violence. A one-unit increase in the childhood exposure index to alcohol was associated with a .126 unit increase in the domestic violence scale, while each additional sexual partner was associated with a .390 unit increase in the domestic violence scale. Finally, being a heavy drinker was the strongest directly associated variable, yielding a 1.353 unit increase in domestic violence.

An analysis of the total effects, which incorporate both direct and indirect effects, reveals that, in addition to having a direct effect on violence, the number of partners also indirectly affects violence through pattern of drinking (i.e. being a heavy drinker). Overall, each additional partner that a man has combines with being a heavy drinker and is associated with a .546 unit total increase in the domestic violence scale. The age difference between respondents and their wives was found to indirectly affect domestic violence through childhood exposure and through both childhood exposure and heavy drinking. Overall, a one year increase in the age difference between the respondent and their wife was associated with a .038 increase in domestic violence. Childhood exposure to alcohol was found to have both a direct effect upon domestic violence as well as an indirect effect through heavy drinkers. The total effect of a one-unit increase in the childhood exposure to alcohol scale was associated with a .158 unit increase in domestic violence. In summary, work-related stress contributes to the level of domestic violence regardless of where one drinks.

Stress is a more influential factor for those who drink at home than for men who drink in more public places. A one-unit increase in the work-related stress scale was associated with a .256 unit increase in domestic violence for home drinkers as compared to a .158 unit increase in domestic violence for public drinkers. The number of partners and the difference in age between husband and wife, a proxy measure for power differential, are factors that contribute to domestic violence for men who drink in public places but not for men who drink at home. More sexual partners and a greater difference in age between husband and wife increase the level of domestic violence reported. And finally, for those who drink at home, a one liter increase in the amount of pure alcohol consumed in one month was associated with a .438 unit increase in the level of domestic violence; while for those who drink in public places, the pattern of drinking appears to be more influential. For men who drink in public places heavy drinking (consistently drinking a lot and often) is associated with a higher level of domestic violence as compared with overindulgent drinking (i.e. drinking less often but consuming more alcohol in a single sitting).

Results of Qualitative Data Analysis with Wives Whose Husbands Drink

In-depth interviews allow us to explore the trajectory of drinking and domestic violence and to better understand the relationship of different patterns of drinking to levels and types of abuse including sexual abuse and forced risk. Women in our study provided evidence that, overall, violence is progressive and women who experience one form of violence are likely to experience other, more severe, violence over time. Table 2 clusters cases by the co-occurrence of verbal, physical, psychological and sexual violence.

Table 2.

Patterns of violence (N = 44)

| Total number in each row | Types of violence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verbal (N = 39) |

Physical (N = 36) |

Sexual (N = 18) |

Psychological (N = 17) |

|

| N = 39 | X | |||

| N = 32 | X | X | ||

| N = 13 | X | X | X | |

| N = 10 | X | X | X | |

The most common form of violence women reported is verbal (89% of all cases); but verbal violence often co-occurs with physical violence which was present in 82% of all cases. When queried about the factors that produce verbal and/or physical violence, women offered responses that suggest that similar situations are triggers for both including: (a) asking husband about his drinking; (b) refusing to give husband money for alcohol; (c) peer influence; (d) suspicion that wife is seeing other men; (e) issues around food and or cooking; (f) not having children at the expected time; and (g) working outside the home. In addition to these, physical violence was also reported to occur when families experienced financial pressure, the wife refused to have sex, and when the husband blamed his wife for the children's misbehaviors or illnesses. The following quote illustrates how financial strain and dissatisfaction with the way wives performed domestic tasks produce violent responses.

His anger became increased with time. At that time I can't understand what should I do about all this. The one day when we came back home he told me to cook chicken but we do not have money to buy chicken. I told him that we do not have chicken. He told me that then go and buy it. I told him that we do not have money to buy it. Then he became furious and start shouted at me that what I do with the money which I got by work. I told him that this is the end of month and it is finished. But then he starts abusing me and when I reply him he slaps me. I got shocked at that time. I couldn't understand what will I do?

Psychological and sexual violence were reported less frequently, though both were quite common, appearing in 39% and 41% of all cases respectively. Psychological violence includes instances of husbands humiliating or controlling their wives as illustrated in the following excerpt:

He did not allow me to go anywhere. He never takes me for outing or anything. Whenever he have holiday he go alone but never take me with him. Interviewer: Did you ever tell him that you want to go? In the beginning I told him but after that I never talk about this. When I told him, he shouted at me and abused me. So after that I never told him about this.

Women often reported being forced to engage in sex against their will.

That day he went to some party and when he came back he was very much drunk. He came very late…Whenever he came I never sleep with him since I did not like smell of alcohol. So that day also when he came in room to sleep and lay on the bed I put mat on the other side of the room and laid on it. Then he came to me laid besides me and started to kissing me from my back. But I stopped him and told him I do not feel well and I don't like smell of alcohol. But he did not listens me and forcefully make relation with me.

Husbands claimed sex in marriage as a basic right. This view was endorsed and reinforced by family members who expressed the concern that if women refused sex to their husbands, men would seek other partners outside the marriage to meet their needs.

Sometimes when he wants to make relationship and I was tired then he forces me. But after sometime I also get ready for this. You know my sister-in-law and my mother also told me that men go to other women when his wife did not satisfy him. So when he wants to do I make myself ready…at that day he came late at night. And I was very tired. My children were sleeping at that time. He came to me, and start touching me. When I told him that I am tired but he did not listen and he forced me. I couldn't say anything because I afraid that because of voice children may awake.

Although most of the women in our survey did not know the extent to which their husbands engaged in sex outside of marriage, or how that engagement put them at risk, a few did:

He told that he doesn't bother for me. He doesn't have any feelings for me even. If he will pay Rs 50/ 100–200, he can get variety of girls at Naka. He used to go and he will ever go to satisfy him he doesn't need me. He gives them money he gets from me….otherwise he snatches it from me, he beats me by pulling my hairs, beating by hot wooden slab which I use for cooking. He doesn't have any heart. He says that if ever those girls say no to him then he used to slap them even saying that he is paying them enough.

Clustering Based on Husband's Frequency of Alcohol Use and Daily Violence

Further examination revealed three distinct groups6 within the sample of forty-four women:

Those whose husbands drink daily, and engage in daily violence (12 cases).

Those whose husbands drink daily and are sometimes violent (11 cases).

Those whose husbands drink sometimes and are sometimes/daily violent (14).

A relatively high proportion of women in our sample (52%) worked outside of the house and those whose husbands were routinely drinking and violent were even more apt to work outside the house (75%). Women revealed that they often began working in response to family financial stress caused by drinking and over time had become the primary source of family financial support.

After examining these differences across clusters, next we considered differences in progression of drinking and violence over time in association with each cluster. In 9 of the 12 cases of husbands who drank daily and engaged in daily violence, we found that drinking began before marriage (8) or shortly after marriage (1). Women in this group explained their husbands' violence as a consequence of their drinking or as a response to their criticism and attempts to persuade him to stop drinking, stop forcing sex, or other disagreements.

That night when I was alone in the room, he came near to me and told that he want to do sex. I didn't understand. Then he holds me and forced me. When I resisted he scolded me and abused me verbally. …he went outside––he consumed alcohol. And when he drank fully he came inside. At that time I was sleeping. He came to me and put one of his hands on my mouth and then he did sex with me. When I tried to come out of his capture, he slapped me a lot and then he continued doing sex with me.

Among those 11 women with husbands who drank daily and were sometimes violent, five men (45%) had started drinking before marriage, but six men (55%) did not begin drinking until several years into the marriage. Women explained that when their husbands drank, they became violent as a reaction to their talking back or expressed frustration that wives were working outside of the home, which often corresponded with suspicion that the woman was being unfaithful. This pattern of drinking was repeated in the third group of 14 cases where drinking was more sporadic and violence was either sporadic or daily. Reasons that wives felt their husbands were violent towards them were similar: distrust, wives failing to ask for permission and issues around food readiness and cooking.

The case examples of women in our sample reflect the prevalence and acceptability of domestic violence in India. Violence is especially common when alcohol problems are present. Norms held by both men and women regarding the acceptability of domestic violence for many household reasons, as revealed through data from NFHS-3 suggest that bringing about change may be quite difficult. Similar proportions of men and women in Mumbai (overall, approximately 20%) and in Mumbai Slums (30–40%) agree that a husband is justified in hitting or beating his wife for at least one of the following reasons: (a) going out without informing husband, (b) neglecting the house or children, (c) arguing with the husband, (d) refusing to have sex, (e) not cooking food to his liking, (f) showing disrespect for in-laws, and/or g) being suspected of being unfaithful [29].

Coping with Alcohol and Violence and Sex Risk

Women in our study were asked about how they responded or coped with the violence and drinking behaviors including unwanted sex from husbands who had been drinking. For the most part women suffered without seeking help, making significant efforts to be self reliant by seeking employment in and outside of the home to address the financial needs of their families. Unfortunately employment oftentimes seemed to result in further negative consequences when husbands took their wives' income for alcohol or accused them of cheating with other men because they worked outside of the home. As situations grew more intolerable, women sometimes turned to family and neighbors for help; but all too often responses from family members reflected the dominant cultural norms and re-enforced negative situations.

They say that now I am married and I should take all his responsibilities. They say that they have not seen him with anyone by their eyes, rather they have only heard from the neighbours. So how can they believe on them more than his own son? Or in another case he often used to beat me in his family. But whenever he beat me, all family members went outside. Even my father-in-law also went outside and didn't tell him anything ever.

In several instances, by the time support from family and neighbors had been offered, the situation had badly deteriorated:

But when his tortures increased, then I had to tell to my family. He once had beaten me when I was pregnant first time. Then also I suffered and didn't tell anyone. But when I had given birth to three children then also he didn't change and his beating was on hike.

Discussion

With respect to men, when comparing the findings from the two SEM models, we find some similarities as well as differences. With respect to similarities, work stress and childhood exposure to alcohol were found to have a direct and significant effect, being associated with an increased probability of domestic violence in both models. However, the two models showed more differences than similarities. Birthplace, relationship with wife, being a social drinker, and higher amounts of alcohol consumption were found to predict domestic violence for home drinkers, but not for those who drank outside of home environments. Furthermore, while age discordance, number of partners, and heavy drinking was associated with domestic violence among those who drank at other locations, these factors did not predict domestic violence among those who drank at home. A comparison of these two models strongly suggests that the processes that lead to domestic violence are substantially different based upon location of drinking. One main reason may be that public places offer more access to women for extramarital affairs.

Men who engage in domestic violence and who drink in public places are also more apt to drink a lot and drink often (heavy drinkers). Based on these findings, one can infer that husbands who engage in heavy drinking in public places are more apt to have access to alcohol and women than those who drink at home and that both the pattern and location of husband's drinking increase the probability of sexual risk and HIV for married women who experience domestic violence.

Not surprisingly, women were not very knowledgeable about their husbands' involvement in sex outside of marriage. From their interviews alone, it is therefore difficult to assess the actual relationship between sexual abuse and increased HIV risk. However we can infer a relationship by considering the quantitative and qualitative analyses together. As our second model suggests married men who have multiple partners, are heavy drinkers and who drink in public places are a third more likely to engage in domestic violence than social drinkers. Moreover, our survey data indicates that married men who drink outside of the home earn more than those who drink at home. These associations suggest a need for further work to understand how the drinking patterns of married men who drink outside the home might be associated with social influence, alcohol myopia, the availability of women at the site or in locations nearby. These factors increase the likelihood of men's sexual risk behaviors and at the same time, increase the potential for increased domestic violence and sexual abuse. This combination of factors together with gender norms permitting and endorsing forced sex within marriage exacerbates the risk of spreading STIs/HIV from husbands to wives who live with the continual threat of alcohol-related violence.

The data also suggest that strategies designed to reduce violence and sex risk that result from alcohol abuse, such as women's economic development and empowerment must be designed both to challenge dominant gender norms and be culturally acceptable, in order to avoid producing more violent responses from men. This is no small task in a society with limited living alternatives for women where divorce is generally not considered a viable option.

Implications for Intervention and Future Research

Domestic violence is common and widespread and crosses all classes even when alcohol is not present. However our data along with other sources show clearly that domestic violence is exacerbated by alcohol abuse and it may well be more prevalent in poor communities where factors such as financial and work-related stress often are used to rationalize domestic violence. However, despite the growing awareness of the intersection of alcohol, domestic violence and sex risk, which is acknowledged in a number of research and government reports [27], the experience of poor women who are living with these realities on a daily basis suggests that little is actually being done to effectively address the problem. Interventions are required that operate on multiple levels simultaneously, requiring attention to marital stress and the structural constraints that contribute to it, as well as much better enforcement of existing policies regarding domestic violence. Nevertheless, enforcement will be meaningless unless women have real protection including alternative places to live, and sufficient support systems, both short and longer-term.

In addition, specific to our study communities, it is important to provide places for women to gather to talk and provide mutual support to one another–perhaps these could be linked to health care facilities or could be located in places of worship/spiritual support. Potential options for intervention sites and support might include temples/religious organizations, hospitals, traditional health care providers and health clinics, children's school, and special cells for women experiencing abuse located in nearby police stations.

Finally there must be an increase in educational and economic development opportunities for low-income women with limited education that would increase their employability. But economic self-sufficiency approaches must be pro-active and empowering rather than merely a response to deteriorated economic circumstance caused by alcohol abuse. Outside income generated by women in response to their husbands' drinking problems too often merely fans the flames of distrust and abuse.

The accumulated research on the associations among alcohol, violence and sexual risk through forced sex and multiple sexual partners is convincing. Called for now are intervention studies that focus on a better understanding of how to effectively create and organize helping networks for women as well as interventions that work with married couples, address gender norms, and are tailored to address different stages in the progression of alcohol use and violence.

Limitations

While serving to advance the body of literature on the relationship between alcohol use and relationship violence, the study contained several limitations. First, in regard to the quantitative analyses, the dependent variable, violence related to alcohol use, focused specifically on relationship violence as a consequence of alcohol use. Some bias may have been presented into the study here, as it is assumed that respondents correctly attributed violence to alcohol use itself, as opposed to any other possible causal factors. Another limitation is that only cross-sectional data was collected. This prevents the true estimation of direct causal effects among variables which could be better estimated using panel data. Longitudinal approaches could be used in future studies in order to model more accurately the relationships between the precursors of domestic violence and the incidence or level of domestic violence itself. The women interviewed for the qualitative component of this study were not linked directly to the men who participated in the survey. Future studies should focus on data collection from married couples to obtain the experiences and perspectives of both, and to lead to better intervention strategies. Alternatively, studies of men's drinking could include a subsample of wives. Finally, this study was not focused explicitly on violence. Better and more direct measures of violence would improve future study outcomes.

Footnotes

Child marriage in India, while prohibited by law since 1929, and steadily declining is still a reality in India particularly in rural and semi-urban areas. UNICEF recognizes child marriage as a violation of human rights as young girls are not yet-physically, mentally and emotionally ready to perform the obligations of marriage and are often unprepared to protect themselves against violence and exploitation (www.unicef.org/india/child_protection.Feb.2010_1536.htm).

As Levine's test of the homogeneity of variances was found to be significant at the .05 alpha level, the Games-Howell post hoc test was used, as it does not assume the equality of variances.

Chi-square difference tests were used to make the determination of whether the unconstrained or a constrained model would be used. Here, the unconstrained model refers to a model in which all parameters are estimated separately for both groups, while in the constrained model, one or more sets of parameters are constrained to be equal between the two groups. If a constrained model does not have significantly worse model fit, it is preferred over an unconstrained or less constrained model as constrained models are simpler, or more parsimonious. A chi-square difference test revealed the unconstrained model to be preferred over any of the constrained models, suggesting the use of two separate structural equation models, one including respondents who drink at home, the other including respondents who primarily drink at other locations.

Initially, the following variables were included in the model predicting violence: region of residence, religion, the difference in education between husband and wife, the difference in age between husband and wife, the hypermasculinity scale, the work related stress scale, number of partners, relationship with wife scale, years married, whether the respondent has children, the index of childhood exposure to alcohol, alcohol total, and pattern of drinking. The finalized models, presented in this paper, were determined after a series of revisions. The majority of the variables removed from the model were removed as they were not found to directly or indirectly affect violence.

Direct effects are defined as those influences (factors/independent variables) that are unmediated by any other variable in the model. They are specified as coefficients in the SEM matrix and displayed on the line linking one variable to another in the figure depicting the model. Indirect effects are mediated by at least one intervening variable. They are determined by subtracting the direct effects from the total effects [28].

In the remaining seven cases violence had ended; in two instances the women had fled the situation through divorce or separation; in one case the husband had stopped drinking; in another instance the intervention of friends and neighbors resulted in an end to the violence and in the remaining three cases the violence ended although the drinking did not.

Contributor Information

Marlene J. Berg, Email: marlene.berg@icrweb.org, Institute for Community Research, 2 Hartford Square West, Ste. 100, Hartford, CT 06106, USA.

David Kremelberg, Institute for Community Research, 2 Hartford Square West, Ste. 100, Hartford, CT 06106, USA.

Purva Dwivedi, International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India.

Supriya Verma, International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India.

Jean J. Schensul, Institute for Community Research, 2 Hartford Square West, Ste. 100, Hartford, CT 06106, USA

Kamla Gupta, International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India.

Devyani Chandran, St. Olaf's College, Northfield, MI, USA.

S. K. Singh, International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India

References

- 1.Jeyaseelan L, Kumar S, Neelakantan N, Peedicayil A, Pillai RND. Physical spousal violence against women in India: some risk factors. J Biosoc Sci. 2007;39(5):657–70. doi: 10.1017/S0021932007001836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duvvury N, Nayak MB, Allendorf K. Links between masculinity and violence: aggregate analysis. Domestic violence in India: exploring strategies, promoting dialogue. Men, masculinity and domestic violence in India. Summary report of four studies. Emeryville, CA: Alcohol Research Group at the Public Health Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ackerson LK, Subramanian SV. Domestic violence and chronic malnutrition among women and children in India. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(10):1188–96. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solomon S, Subbaraman R, Solomon SS, et al. Domestic violence and forced sex among the urban poor in South India: implications for HIV prevention. Violence Against Women. 2009;15(7):753–73. doi: 10.1177/1077801209334602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poonacha V. Exploring differences: an analysis of the complexity and diversity of the contemporary Indian women's movement. Aust Feminist Stud. 1999;14(29):195–206. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ackerson LK, Subramanian SV. Domestic violence and chronic malnutrition among women and children in India. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(10):1188–96. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agarwal B, Panda P. Toward freedom from domestic violence: the neglected obvious. J Human Develop. 2007;8(3):359–88. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dworkin SL, Ehrhardt AA. Going beyond “ABC” to include “GEM”: critical reflections on progress in the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):13–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.074591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta GR. Globalization, women and the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Peace Rev. 2004;16(1):79–83. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parker RG, Easton D, Klein CH. Structural barriers and facilitators in HIV prevention: a review of international research. AIDS. 2000;14:S22–32. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Go VF, Sethulakshmi CJ, Bentley ME, et al. When HIV-prevention messages and gender norms clash: the impact of domestic violence on women's HIV risk in slums of Chennai, India. AIDS Behav. 2003;7(3):263–72. doi: 10.1023/a:1025443719490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krishnan S. Do structural inequalities contribute to marital violence? Ethnographic evidence from rural South India. Violence Against Women. 2005;11(6):759–75. doi: 10.1177/1077801205276078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.George WH, Stoner SA. Understanding acute alcohol effects on sexual behavior. Ann Rev Sex Res. 2000;11:92–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolezal C, Carballo-Diéguez A, Nieves-Rosa L, Díaz F. Substance use and sexual risk behavior: understanding their association among four ethnic groups of Latino men who have sex with men. J Subst Abuse. 2000;11(4):323–36. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Windle M. The trading of sex for money or drugs, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), and HIV-related risk behaviors among multisubstance using alcoholic inpatients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;49(1):33–8. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stanley S. Interpersonal violence in alcohol complicated marital relationships (a study from India) J Fam Violence. 2008;23(8):767–76. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silverman JG, Decker MR, Saggurti N, Balaiah D, Raj A. Intimate partner violence and HIV infection among married indian women. JAMA. 2008;300(6):703–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.6.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chandrasekaran V, Krupp K, George R, Madhivanan P. Determinants of domestic violence among women attending and human immunodeficiency virus voluntary counseling and testing center in Bangalore, India. Indian J Med Sci. 2007;61(5):253–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Go VF, Johnson SC, Bentley ME, et al. Crossing the threshold: engendered definitions of socially acceptable domestic violence in Chennai, India. Cult Health Sex. 2003;5(5) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell JC, Baty ML, Ghandour RM, Stockman JK, Francisco L, Wagman J. The intersection of intimate partner violence against women and HIV/AIDS: a review. Int J Injury Control Safety Promotion. 2008;15(4):221–31. doi: 10.1080/17457300802423224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.George A, Jaswal S. Understanding sexuality: an ethnographic study of poor women in Bombay, India. Washington, DC: International Center for Research on Women; 1995. p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santhya KG, Dasvarma GL. Spousal communication on reproductive illness among rural women in southern India. Cult, Health & Sex. 2002;4(2):223–36. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jejeebhoy SJ, Koenig MA, Elias C, NetLibrary I. Investigating reproductive tract infections and other gynaecological disorders a multidisciplinary research approach. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green J, Plant MA. Bad bars: a review of risk factors. J Subst Use. 2007;12(3):157–89. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma K. Behind closed doors: domestic violence in India. Feminist Review. 2006;83(1):169–71. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heise LL. Violence against women: an integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women. 1998;4(3):262–90. doi: 10.1177/1077801298004003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saggurti N, Malviya A. HIV transmission in intimate partner relationships in India. New Delhi, India: UNAIDS; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bollen KA. Total, direct, and indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociol Methodol. 1987;17:37–69. [Google Scholar]

- 29.International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International. National family health survey (NFHS-3), 2005–2006: India, Domestic violence Vol, 1, Chap. 15. Mumbai: IIPS; 2007. [Google Scholar]