Abstract

Background

A report of an anthrax outbreak was received at Gokwe district hospital from the Veterinary department on the 23rd January 2007. This study was therefore conducted to determine risk factors for contracting anthrax amongst residents of Kuwirirana ward.

Methods

We conducted a 1:1 unmatched case control study. A case was any person in Kuwirirana ward who developed a disease which manifested by itching of the affected area, followed by a painful lesion which became papular, then vesiculated and eventually developed into a depressed black eschar from 12 January to 20 February 2007. A control was a person resident of Kuwirirana ward without such diagnosis during the same period.

Results

Thirty-seven cases and 37 controls were interviewed. On univariate analysis, eating contaminated meat (OR = 7.7, 95% CI 2–29.8), belonging to a household with cattle deaths (OR= 9.7, 95% CI 2.9–33), assisting with skinning anthrax infected carcasses (OR= 5.4(95% CI 1.7–17), assisting with meat preparation for drying (OR = 5(95%CI 1.9–13.9), assisting with cutting contaminated meat (OR = 4.8(95% CI 1.7–13.2), having cuts or wounds during skinning (OR = 19.5, 95% CI 2.4–159) and belonging to a village with cattle deaths (OR = 6.5(95%CI 1.3–32) were significantly associated with anthrax.

Conclusion

Anthrax in Kuwirirana resulted from contact with and consumption of anthrax infected carcasses. We recommend that the district hold regular zoonotic committee meetings and conduct awareness campaign for the community and carry out annual cattle vaccinations.

Keywords: Zimbabwe, Gokwe, Outbreak, Anthrax, Bacillus anthracis

Introduction

Anthrax is primarily a disease of herbivorous mammals, although other mammals and some birds have been known to contract it. Humans generally acquire the disease directly or indirectly from infected animals or occupational exposure to infected or contaminated animal products. Control in livestock is therefore the key to reduced incidence. There are no documented cases of person to person transmission. The disease's impact on animal and human health can be devastating1,2,3.

The causative agent of anthrax is the bacterium, Bacillus anthracis, the spores of which can survive in the environment for years or decades, awaiting uptake by the next host.

The disease still exists in animals and humans in most countries of sub-Sahelian Africa and Asia, in several southern European countries, in the Americas, and certain areas of Australia. Disease outbreaks in animals also occur sporadically in other countries1,3.

There are three types of anthrax in humans: cutaneous anthrax, acquired when a spore enters the skin through a cut or an abrasion; gastrointestinal tract anthrax, contracted from eating contaminated food, primarily meat from an animal that died of the disease; and pulmonary (inhalation) anthrax from breathing in airborne anthrax spores. The cutaneous form accounts for 95% or more of human cases globally. All three types of anthrax are potentially fatal if not treated promptly1,3,4.

Outbreaks and epidemics do occur in humans; sometimes these are sizeable, such as the epidemic in Zimbabwe which began in 1979, was still smouldering in 1984–5 and had by that time affected many thousands of persons, albeit with a low case fatality rate4. In Zimbabwe anthrax is a notifiable disease in terms of the Public Health Act Chapter 15:09. One case of anthrax in Zimbabwe is an outbreak which calls for notification within 24hrs and quick response to control the outbreak.5

On the 23rd of January 2007, the Gokwe District Health Executive received a phone call from the Veterinary department notifying them of an anthrax outbreak in Kuwirirana ward. On the same date, a district team comprising of the District Environmental Health Officer (DEHO), Trainee Environmental Health Officer (TEHO), Community Health Sister (CHS), Health Promotion Officer (HPO) and a Principal Environmental Health Technician (PEHT) left for Kuwirirana on a mission to conduct a preliminary assessment of the outbreak. No cases had yet reported at Kuwirirana clinic seeking medical attention by then.

It was against this background that the investigation was conducted with the aim to control and establish factors associated with contracting anthrax in the affected area.

Methods

We used a 1:1 unmatched case control study design. A case was any person in Kuwirirana ward who developed a disease which manifested by itching of the affected area, followed by a painful lesion which became papular, then vesiculated and eventually developed into a depressed black eschar from 12 January to 20 February 2007. Cases were identified from the clinic line list and through active case finding in the community.

A control was any person resident of Kuwirirana ward who did not develop itchiness that was followed by a painful lesion which became popular, vesiculated with a black depressed eschar from 12 January to 20 February 2007.

All cases that could be located during the study period were recruited into the study. The controls were conveniently selected from the nearest household/s of each case to be matched with.

Children under the age of twelve were excluded from the interviews as they would not answer the questions properly. Those who were absent from home on two consecutive visits were left out of the study and those that had moved out of the area.

We collected data using a pre-tested interviewer administered questionnaire. Formal discussions were also held with RHC staff, District Health Executive staff and Veterinary department staff to assess how they detected and responded to the outbreak. We captured and analyzed data by using Epi-info Version 3.3.2, (Centres for Disease Control: 2005).

This software was used to generate frequencies, means, contingency tables, odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. A p-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant. Qualitative data was analyzed manually.

Permission to conduct the study was sought and obtained from the Director of Health Services, Provincial Medical Director Midlands, the District Medical Officer for Gokwe District and Health Studies Office. Informed verbal consent was obtained from all respondents and guardians of children that were under 18 years of age.

Results

Demographic characteristics of cases and controls

Thirty-seven cases and 37 controls were enrolled into the study. The median age for cases was 28(Q1=19; Q3=35) and for controls 25(Q1=19; Q2=41). A total of 42 males were interviewed twenty amongst cases and 22 amongst controls. The rest (32) were females, 17 amongst cases and 15 amongst the controls. Nineteen (51.4%) of the cases were married compared to 21(56.8%) amongst the controls. Twenty-nine (78.4%) of the cases were unemployed compared to 27 (73%) for controls. Nine (43%) cases had attained secondary education and above which was the case with 26 (62%) controls. With regards to religion, the majority of the respondents belonged to the Apostolic sect, that is 19 amongst the cases and 14 amongst the controls (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data

| Variable | Cases N=37 |

Controls N=37 |

| Gender | ||

| M | 20 | 22 |

| F | 17 | 15 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 19 | 21 |

| Single | 13 | 13 |

| Divorced | 2 | 0 |

| Widowed | 3 | 3 |

| Median Age | 28(Q1=19: Q3 = 35) |

25(Q1 = 19: Q3 = 41) |

| Level of Education | ||

| None | 3 | 1 |

| Primary upto grade 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Primary upto grade 7 | 10 | 6 |

| Secondary upto form 2 | 5 | 10 |

| Secondary upto form 4 | 17 | 16 |

| Tertiary | 0 | 1 |

| Religion | ||

| Apostolic | 19 | 14 |

| SDA | 3 | 2 |

| AFM | 0 | 2 |

| Anglican | 0 | 7 |

| Roman catholic | 7 | 3 |

| Methodist | 2 | 7 |

| Traditional | 4 | 1 |

| Atheist | 2 | 1 |

| Median H/H size | 6(Q1 = 4: Q3 = 7) |

5(Q1 = 4: Q3 = 8) |

| Occupation | ||

| Unemployed | 29 | 27 |

| Formally employed | 0 | 2 |

| Informally employed | 1 | 2 |

| Student | 7 | 6 |

Description of the outbreak by person

A total of 64 cases were line listed. The most affected age group was the above 12 years (57.8%) while the least affected were the under 5 years (1.6%). The most affected organ was the hand especially the fingers with 17 (23%) followed by the leg and buttock with 9(%) and 5(%) respectively. There were no deaths reported.

Description of the outbreak by place

Three villages were affected by the outbreak and these were Nhau (30 cases), Mateesanwa (5 cases) and Makwikwi (2 cases). The most affected areas had most of the cattle deaths. There is very limited grazing for the cattle in the area of Nhau and other surrounding areas.

Description of the outbreak by time

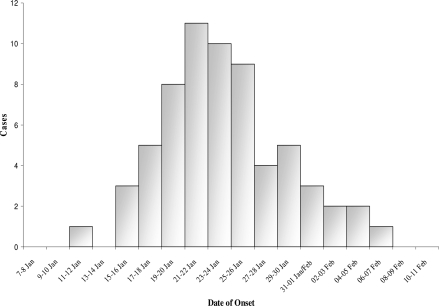

The first human case in the community occurred on the 12th of January 2007 after three cattle deaths in Nhau village. In total 15 cattle deaths occurred and 14 of these cattle were consumed by the villagers. Cases started rising gradually thereafter reaching the highest peak by the 25th of January which coincidentally was the day when the district started implementing intervention measures. The intervention measures included cattle vaccination, treatment of cases, health education to the community, burning and burying of infected meat and carcasses among others. The sequences of events of the outbreak from the beginning to the end are illustrated by the Epi Curve in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Kuwirirana Anthrax Outbreak Epidemic Curve January – February 2007

Risk factors for contracting anthrax

All the twenty one cases who participated in the study had handled the carcasses or their products during the different activities of processing the meat.

Univariate analysis

Eating meat from an infected beast was a risk factor OR = 7.7(95% CI 2–29.8), belonging to a household with cattle deaths was also a risk factor OR = 9.7(95% CI 2.9–33). Assisting with skinning anthrax infected carcasses was a risk factor OR = 5.4(95% CI 1.7–17). Assisting with preparation of meat for drying was another risk factor OR = 5(95%CI 1.9–13.9). Assisting with cutting meat from an infected animal was a risk factor OR = 4.8(95% CI 1.7–13.2). Having cuts or wounds during skinning was a significant risk factor OR = 19.5(95% CI 2.4–159). Belonging to a village with cattle deaths was a risk factor OR = 6.5(95%CI 1.3–32) (See Table 2).

Table 2.

Risk Factors for Contracting Anthrax in Kuwirirana

| Variable | Cases N | Controls | OR | 95% CI |

| (Col %) | N (Col %) | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 20(54.1) | 22(59.5) | 0.8 | 0.3 – 2.0 |

| Female | 17 | 15 | ||

| Habitation status (Marital status) | ||||

| Married | 13(35.1) | 13(35.1) | 1 | 0.4 – 2.6 |

| Single | 24 | 24 | ||

| Church (Religion) | ||||

| Apostolic | 19(51.4) | 14(37.8) | 1.7 | 0.7 – 4.4 |

| Non Apostolic | 18 | 23 | ||

| Occupation | ||||

| Unemployed | 36(97.3) | 33(89.2) | 4.4 | 0.4 – 41 |

| Employed | 1 | 4 | ||

| Education | ||||

| Primary | 15(40.5) | 10(27) | 1.8 | 0.7 – 4.9 |

| Secondary/Tertiary | 22 | 27 | ||

| Eating meat | ||||

| Yes | 34(91.9) | 22(59.5) | 7.7 | 2 –29.8 |

| No | 3 | 15 | ||

| Own cattle dying | ||||

| Yes | 20(54.1) | 4(10.8) | 9.7 | 2.9 – 33 |

| No | 17 | 33 | ||

| Assisting with skinning | ||||

| Yes | 16(43.2) | 6(16.2) | 5.4 | 1.7 – 17 |

| No | 20 | 32 | ||

| Assisting with preparation of hide | ||||

| Yes | ||||

| No | 3(8.1)34 | 3(8.1)34 | 1 | 0.2 – 5.3 |

| Assisting with drying meat | ||||

| Yes | 23(62.2) | 10(27) | 5 | 1.9 – 13.9 |

| No | 14 | 27 | ||

| Assisting with cutting & cooking meat | ||||

| Yes | 29(78.4) | 16(43.2) | 4.8 | 1.7 – 13.2 |

| No | 8 | 21 | ||

| Having cuts/wounds | ||||

| Yes | 13(35.1) | 1(2.7) | 19.5 | 2.4 – 159 |

| No | 24 | 36 | ||

| Cattle deaths in village | ||||

| Yes | 35(94.6) | 27(73) | 6.5 | 1.3–32 |

| No | 2 | 10 |

Multivariate analysis

Having cattle dying in one's household (AOR= 8.8 (95% CI 2.3–33.7), having cuts (AOR= 23 (95% CI 2.5–212), and assisting with cutting and cooking infected AOR= 3.7 (95% CI 1.03–13.2), meat were independent risk factors for contracting anthrax in Kuwirirana ward.

Knowledge of Signs and Symptoms of Anthrax in Humans

A larger proportion of the controls 31(83.8%) compared to cases 21(58.3) had heard about anthrax prior to the outbreak. With regards to signs and symptoms again a larger proportion of the controls 32(86.5) as compared to the cases 29(78.4) knew about the typical anthrax skin lesion.

Symptoms experienced and the treatment seeking behaviors of respondents

The majority of the cases 30(40.5%) presented with a typical anthrax skin lesion. The median days of treatment seeking was 6days (Q1=3; Q3=7). The majority 23(62.2%) of the cases sought treatment from the outreach team that had visited the affected area. All cases were treated with doxycycline.

Attitude and practices likely to fuel the outbreak

There were no major statistical differences between cases and controls with regards to attitudes and practices likely to fuel the outbreak. Both cases 31(83.8%) and controls 36(97.3%) agreed that killing of moribund animals was a common practice in that community. It was interesting to note that both cases and controls overwhelmingly disagreed with the statements that overcooking infected meat as well as roasting infected meat can kill anthrax germs.

Eighteen cases (48.6%) and 17 (45.9%) controls agreed that there were some local herbs capable of curing anthrax namely murumanyama and mukundanyoka. The local name for anthrax is Chibhabha.

Discussion

The epi curve depicts a common source type of outbreak. Cases rose gradually from the 12th of January and as soon as intervention strategies were put into place from the 25th of January, there was a sudden decrease in the number of cases reaching zero by the 8th of February.

The study came up with six statistically significant risk factors for contracting anthrax in Kuwirirana inclusive of, eating meat from an infected carcass, belonging to a household with cattle deaths, assisting with skinning anthrax infected carcasses, assisting with drying infected meat, assisting with cutting and cooking infected meat as well as having cuts or wounds during skinning.

Contrary to the findings of a number of studies with regards to religion, belonging to a restrictive religion was not protective. This can be explained by the practice of killing moribund animals which was quite rampant in the affected community. This was done so as to circumvent their religious requirement which does not allow consumption of meat from an animal that die on its own.

Our findings on risk factors are consistent with those of Mwenye KS, Siziya S, Peterson D. in a similar study in Murewa district of Mashonaland West Province as well as Kumar A et al in India.6,7

Having cuts or open wound during processing in areas likely to come into contact with infected material increased the risk of contracting anthrax. This was so because these areas were unobstructed routes of entry for large numbers of bacteria compared with an intact skin. This was consistent with what Woods CW et al found out in an anthrax outbreak in Kazakhstan8. According to the study presence of visible cuts on the hands were associated with anthrax (RR = 3.0, 95% Cl = 0.9–9.6).

Having cattle deaths in the household was found to be a risk factor for contracting anthrax. This was because the chances of coming in contact with infected meat or products were increased since members would be actively be involved in skinning and cutting of carcasses for sale and consumption unlike the household where cattle deaths did not occur.

The position of the majority of anthrax lesions was on the fingers. This is consistent with Mwenye et al findings of a study in Murehwa9. Fingers are involved in handling the infected meat and have higher risk of having cuts or open wounds which increases the likelihood of infection in that part of the body.

Knowledge levels were quite high. This can be explained by the fact that health education had already been given prior to the investigation. However the high levels of knowledge are consistent with those found by Opare C et al in Ghana where there were as high as 96% 10.

No case fatality was recorded in this outbreak. This is consistent with findings of Lakshmi N et al in India11. Other literature confirm very low case fatality rates are recorded with treatment of cases.12, 13

Our study demonstrated that the anthrax in Kuwirirana resulted from contact with and consumption of anthrax infected carcasses. Risk factors for contracting anthrax included eating meat from an infected carcass, belonging to a household with cattle deaths, assisting with skinning anthrax infected carcasses, assisting with drying infected meat, assisting with cutting and cooking infected meat as well as having cuts or wounds during skinning.

Although the district managed to control the outbreak Quality and timeliness of detection, notification and responding to the outbreak was below the national Emergency Preparedness and Response (EPR) set targets.

In view of the foregone, Midlands Provincial Director's office should develop a strategic framework aiming at reducing the incidence of anthrax in the province. The District Health Executive should in liaison with the community develop relevant IEC material targeting those attitudes and practices that are likely to promote the spread of anthrax for example butchering of moribund animals. The District Health Executive in conjunction with other stakeholders particularly the Veterinary Department should conduct annual anthrax awareness campaigns targeting the population at risk.

Conclusion

In order to avert future outbreaks the Veterinary department should conduct annual cattle vaccination campaigns. In the event of cattle deaths the community should be encouraged to report to the Veterinary Department as well Ministry of Health. There is need to improve surveillance through strengthening of the communication system. In view of dwindling resources there is need to set up community based surveillance structures to enable early detection of zoonotic diseases.

Acknowledgements

I wish to express my gratitude to all those who made this project a success in one way or the other. These include the following: The Director of Health Services, Dr. Z. Hwalima and her Assistant Director, Dr. BMM Nkomo, The MPH Field Coordinator, Dr. M. Tshimanga, The Midlands Provincial Medical Director, Dr. A. Chimusoro, The Gokwe North District Health Executive led by Dr. Venge, The Public Health Officer for Midlands, Mr. A. Chadambuka, The Provincial Physiotherapist, Mr. Kaseke and indeed the community of Kuwirirana. Thank you all and God bless.

References

- 1.World Health Organization, author. Anthrax. [17/02/07]. Available from URL: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs264/en/

- 2.PHLS-CDSC, author. Anthrax : Interim PHLS Guidelines for Action in the Event of a Deliberate Release. [12/07/2010]. http://www.firstaidcafe.co.uk/Medical/Anthrax_guidelines.pdf.

- 3.Hugh-Jones M. Global Anthrax Report 1996–97. [19/02/07];Journal of Applied Microbiology. 1999 87:189–191. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00867.x. Available from URL: http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/pdf/10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization, author. Guidelines for the Surveillance and Control of Anthrax in Humans and Animals. 3rd Edition. PCB Turnbull. World Health Organisation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Government Printers, author. Zimbabwe Public Health Act, CAP 15:09, Revised Edition. Harare: Government Printers; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mwenye KS, Siziya S, Peterson D. Factors associated with human anthrax outbreak in the Chikupo and Ngandu villages of Murewa District, Mashonaland East. Central African Medical Journal. 1996 Nov;42(11):312–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woods CW, Ospanov K, Myrzabekov A, Favorov M, Plikaytis B, Ashford DA. Risk factors for human anthrax among contacts of anthrax-infected livestock in Kazakhstan. American Journal Tropical Medicine Hygiene. 2004 Jul;71(1):48–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lakshmi N, Kumar AG. An epidemic of human anthrax—a study. Indian Journal Pathology and Microbiology. 1992 Jan;35(1):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization, author. Guidance on anthrax: frequently asked questions. [17/02/07]. Available from URL: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/Anthrax/anthraxfaq/en/

- 10.Chin J. Control of Communicable Diseases Manual: American Public Health Association. 17th Edition. (20) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar A, Kanungo R, Bhattacharya S, Badrinath S, Dutta TK, Swaminathan RP. Human anthrax in India: urgent need for effective prevention. Journal of Communicable Diseases. 2000 Dec;32(4):240–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Opare C, Nsiire A, Awumbilla B, Akanmori BD. Human behavioural factors implicated in outbreaks of human anthrax in the Tamale municipality of northern Ghana. Acta Tropica. 2000 Jul 21;76(1):49–52. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(00)00089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takawira E, Charimari L, Tshimanga M. An outbreak investigation of Anthrax in Rushinga District of Mashonaland Central Province in Zimbabwe; 2004. Abstracts of research projects and Field reports by Masters in Public Health Officers. [Google Scholar]