Summary

Objectives

Anatomical abnormalities associated with cleft lip and palate increase the risk of airway complications. The aim of this study was to determine the incidence of intra-operative airway and respiratory complications during cleft lip and palate repair and identify risk factors.

Design

Observational study in which fifty consecutive patients undergoing cleft lip or/ and palate repair (CL, CP, CLP) were prospectively studied in a teaching hospital in Nigeria. Anaesthesia was achieved by the inhalational or intravenous route. Tracheal intubation was performed under deep inhalational anaesthesia or muscle relaxation. All patients were ventilated. Demographic data, airway and respiratory complications were documented.

Results

The mean age of the patients was 26.62± 4.71(SEM) months (median 11.50). Nineteen airway complications occurred in 16 patients (incidence - 38%) as failed and difficult intubation (2% respectively) which only occurred in CP surgeries, Tube disconnection (6%), Tube compression (2%), Accidental extubation (2%) and Desaturation (14%). Laryngeal spasm (6%) and Bronchospasm (4%) occurred in surgeries for CP repair only. Some patients had more than one complication. Complications occurred in 38.4% of patients having CP repair, 15.8% having CL repair and 50% having CLP repair (p=0.185). This was not influenced by weight nor age group (p = 0.076 and 0.400 respectively).

Conclusion

Cleft repair had a high incidence of airway/ respiratory complications. More complications occurred with CP surgery. There is a need to ensure adequately skilled personnel and appropriate monitoring to minimise morbidity.

Keywords: anaesthesia, airway complications, cleft lip, cleft palate

Introduction

Children especially infants have a higher incidence of anaesthetic related complications.1,2 Due to their peculiar paediatric airway, they are prone to difficult airway management and laryngoscopy as well as other airway complications. Bordet3 demonstrated that airway complications occurred in 7.87% of children under anaesthesia and that the incidence varied with the type of airway device used with laryngeal mask airway(LMA) having the highest incidence of 10.2%, tracheal tube 7.4% and facemask 4.7%.

Patients for cleft repair are at increased risk of intraoperative airway and respiratory complications. The anatomical defects increase the risk of difficult laryngoscopy and intubation and the intra-oral site of surgery means problems with tracheal tubes occur more frequently. The documented incidence of difficult airway in cleft surgery ranges from 4.7% – 8.4%.4,5 Various researchers have enumerated factors associated with an increased risk of airway complications in these patients. They include anatomical difficulty in placement of laryngoscope blade6, the presence of associated facial deformities, for example, micrognathia4,7 and the degree of deformity with a higher risk occurring in combined bilateral clefts4. The difficulty in laryngoscopy and intubation seen in cleft palate patients is related to age, being higher in infants.4 The risk of perioperative respiratory adverse effects is less if tracheal intubation is facilitated by muscle relaxants8,9 and accidental extubation when positioning the head for surgery is minimised if the tube is placed 1.5 cm above the carina.10

Recurrent infections of the nasal cavity and respiratory tract due to constant irritation and aspiration increase airway reactivity and may result in laryngeal and bronchospasm.11 Takemura et al1 defined perioperative respiratory symptoms (PRC) as occurrence of laryngospasm or bronchospasm during induction; increased airway secretions and desaturation (<95%) during maintenance and respiratory symptoms observed immediately after extubation.

They observed that children with borderline common cold symptoms had a higher incidence of perioperative respiratory complications (23%) during cleft surgeries compared to healthy children with incidence of 4%.1

The purpose of this prospective study was to determine the incidence of intra-operative airway and respiratory related complications during cleft lip and palate repair and to identify risk factor for their occurrence.

Methods

Fifty patients undergoing cleft lip and or palate repair were prospectively studied after Institutional Ethical committee approval and informed parental consent were obtained. This study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Lagos, Nigeria between July and October 2008. The patients were seen in the pre-anaesthetic clinic by the Oral and maxillofacial surgeons and anaesthetists. Those suitable for surgery were admitted into hospital two days before surgery and all eligible children were included in the study. Patients with cardiac murmurs were referred to the paediatric cardiologists, while those with respiratory tract infection were treated with appropriate antibiotics and surgery deferred for two weeks in upper respiratory tract infection or four weeks in lower respiratory tract. Routine pre-operative fasting guidelines were instituted. No patient received sedative premedication.

Standard inhalational halothane induction or intravenous induction using thiopentone or propofol was employed. The trachea was intubated with a RAE tube (for cleft lip repair only) or armoured endotracheal tube (for palatal surgery) under deep inhalational anaesthesia or muscle relaxants. Standard intraoperative monitoring was employed. Surgical site was infiltrated with adrenaline 3 – 5 mcg/kg of 1:100,000 solution before the incision was made. Maintenance of anaesthesia was with isoflurane and a muscle relaxant and ventilation was controlled.

Appropriate analgesia was ensured. At the end of surgery, children were extubated when fully awake with protective airway reflexes. All intra-operative or immediate post-operative airway complications were documented. For the purpose of the study, the following definitions were used -Difficult intubation - ≥ three attempts at intubation -Desaturation - fall in oxygen saturation to < 90% - Bronchospasm - wheezing, with prolonged expiratory phase and increase in slope of plateau on capnography tracing. - Laryngospasm −SpO2 less than 90%, with partial or complete airway obstruction unrelieved by routine airway manoeuvres.

Data was analysed using the SPSS for Windows (version 10.1; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) statistical software package. Numerical data was expressed as mean ± SD while categorical data was expressed as frequencies. Tests of significance (t-test, chi-square or Fisher's exact test) were used as appropriate. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The mean age of patients studied was 26.62 ± 4.71 (SEM) months (Range 3 – 132 months) with a median of 11.50 months. Nineteen patients (38%) had primary cleft lip (CL) repair, 26 (52%) had primary cleft palate repair (CP), 2 (4%) had both lip and palate repair (CLP) and 3 (6%) had cleft lip revision and fistula repair. Demographic and intraoperative data is shown in Table 1. Thirty seven patients (74%) had Inhalational induction while 26% had intravenous induction. Muscle relaxants facilitated intubation in 80% of patients. Nineteen airway complications occurred in 16 patients (incidence - 38% of 50 procedures). Some patients developed more than one complication. The most common complication was desaturation (14%), followed by laryngeal spasm (6%) and tube disconnection (6%). The incidence of failed/difficult intubation was 4% (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographic and intraoperative data of cleft lip and palate patients

| Surgical procedure | Age (months) Mean ± SD |

Weight (Kg) Mean ± SD |

Duration of surgery (minutes) Mean ± SD |

Estimated Blood loss (mls) Mean ± SD |

No of patients transfused |

|

Cleft Lip repair (n = 19) |

10.52 ± 4.15 | 7.86 ± 4.68 | 91.37 ± 18.77 | 24.68 ± 5.79 | 1 |

|

Cleft Palate repair (n = 26) |

36.6 ± 9.03 | 13.31 ± 11.75 | 113.84 ± 53.97 | 82.00 ± 14.80 | 2 |

| p-value | 0.013 | 0.043 | 0.363 | 0.001 | 1.00 |

Table 2.

Different Types Of Airway Complications Observed

| Airway Complications | Number (% of study population) |

| Failed intubation | 1 (2%) |

| Difficult intubation | 1 (2%) |

| Tube Disconnection | 3 (6%) |

| Tube Compression | 1 (2%) |

| Accidental Extubation | 1 (2%) |

| Desaturation | 7 (14%) |

| Laryngeal spasm | 3 (6%) |

| Bronchospasm | 2 (4%) |

| None | 31(62%) |

| Total | 50 (100%) |

Table 3 displays the incidence of complications in relation to the surgical procedure. 38% of patients who had CP repair developed complications, 15.8% who had CL repair developed complications and 50% of patients who had CLP repair developed complications. (p=0.185). All Intubation problems, laryngeal spasm and bronchospasm occurred in CP or CLP patients only. All but one of the tube-related problems (disconnection, compression, extubation) occurred in patients for CP repair. There was a significant association between CP surgery and the occurrence of intubation, tube-related and spasm problems (p=0.048).

Table 3.

Airway complications associated with different surgical procedures

| Surgical Procedures | Number of Airway complication (%) |

| Cleft Lip Repair (n=19) | 3 (15.8%) |

| Cleft palate repair (n=26) | 10 (38.4%) |

| Cleft lip and palate repair (n=2) | 1 (50%) |

| Others (n=3) | 2 (66.6%) |

p=0.185

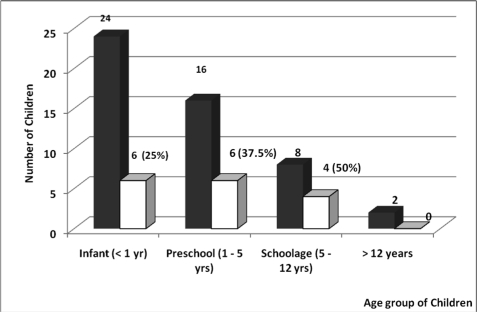

All episodes of bronchospasm, laryngeal spasm and desaturation occurred in patients who had inhalational induction of anaesthesia. Desaturation mostly occurred at intubation (86%) but one patient with accidental extubation also exhibited desaturation. All episodes of laryngeal spasms occurred at induction. The association between age and occurrence of airway complications is shown in Figure 1. Seven patients weighed less than 5kg, 29 weighed between 5 and 10 kg, while 9 patients weighed 10 – 20 kg and 5 more than 20 kg. Twenty-eight percent of patients weighing < 5 kg had complications while 20.7% of those weighing 5 – 10kg, 60% of children weighing 10–20 kg and 40% weighing > 20 kg developed complications (p = 0.076).

Figure 1.

Age range of patients who developed complications (■ Total number of patients □ Number of patients with complications)

All patients who developed complications were successfully discharged to the wards with no sequelae. There was no mortality recorded.

Discussion

This study has demonstrated a high incidence (38%) of airway and respiratory complications in cleft surgery. A study from Tokyo observed a 4% incidence of respiratory complications in cleft surgeries in infants < 6 months.1 That study however did not take into account tube-related factors and intubation difficulties. Filles7 demonstrated an 8.6% incidence of respiratory complications in their series of 174 infants. However, they administered atropine pre-induction which could have accounted for their reduced incidence. In addition oxygen saturation < 85% was taken as definition of desaturation compared to <90% used in the present study.

CL repair is recommended at the age of three months to improve cosmetic appearance and parent-child bonding while CP repair is performed from nine months to allow for facial growth and speech development. Stephen12 performed cleft lip repair in neonates and reported no evidence to prove that it was unsafe. A large proportion of our patients were older than one year because they are kept in hiding because of associated stigma as well as financial constraints. Other African authors have also documented this observation.13,14 The incidence of critical events in general paediatric anaesthesia is documented to be 8.6% in infants which improves to 2.1% in older patients with a statistically significant difference in children < 10 kg.2 Murat11 reiterated that intraoperative adverse events were more likely in infants < 12 months.

Airway and respiratory complications occurring in cleft surgery repair are often due to intubation, tube-related problems, laryngeal and bronchospasm, desaturation and aspiration. The peculiarity of the infant airway commonly results in difficult airway management and intubation which is aggravated by the existence of cleft lip or palate. The cleft alveolus, protruding maxilla and high vaulted arch cause difficult placement of the laryngoscope blade because of loss of support which results in obstruction of the view needed for normal intubation. Our incidence of airway complications was more in patients having CP repair (38.4%) compared to CL repair (15.8%) though this was not statistically significant. This was also observed by Frilles.7

In the present study, a 4% incidence of difficult/failed intubation was recorded. This compares well to 4.77% obtained by Xue.4 Difficult intubation occurred in a 18 month old child scheduled for CLP surgery during attempts at intubation under deep inhalational anaesthesia. The child was subsequently intubated under muscle relaxation by a consultant grade anaesthetist. Failed intubation occurred in a 5 year old child for CLP and fistula repair and surgery was deferred. These two cases were probably due to difficulty in inserting the laryngoscope blade or the presence of micrognathia. The blade commonly falls into a left-sided cleft when the tongue is being swept to the left side during laryngoscopy and alters the line of vision posing intubation difficulties.6 Xue4 reported that difficulty in laryngoscopy and intubation seen with CP patients is related to age and is higher in children < 6 months. This was not observed in our study as our patients with failed/difficult intubation were 72 and 18 months respectively. Gunawardana5 obtained higher values of 7.38% difficult laryngoscopy, 8.38% of difficult intubation and 1% of failed intubation without the use of muscle relaxants. This also improved with increasing age.

The risk of perioperative respiratory adverse events is less if tracheal intubation is facilitated by muscle relaxation.8,9 We used muscle relaxants for intubation in majority of our patients, which may have accounted for our lower incidence. Muscle relaxants cause relaxation of the head and neck muscles and assist in obtaining a better laryngoscopic view. Positioning the patient in the optimal sniffing position by the use of a shoulder roll, routine use of external laryngeal manoeuvre, intubating stylet and having a senior anaesthetist intubate the patient are quoted as being contributory towards an easier intubation.4

Tracheal tube problems occurred in five patients (10%) in our study of which there was tube disconnection in three, compression in one and accidental extubation in one patient. All but one (disconnection) occurred in patients having CP repair. The introduction of a mouth gag necessary for palatal repair can compress or move the tube. This is easily detected by airway pressure monitoring and capnography tracing which emphasises the importance of adequate monitoring for early detection. The placement of the patient for surgery also contributes to tube movement. Neck extension causes backward movement of the tube away from the carina while flexion can result in endobronchial placement.

Poor nutrition and development which characterise CLP patients may influence the calculation for correct placement of the tracheal tube. Kohjitani10 demonstrated that if the tracheal tube is placed 1.5 cm above the carina in the neutral head position, it minimises the chance of accidental extubation when the head is extended. It is therefore imperative that the tube is firmly secured to prevent any movement and tube position is noted and checked after positioning. The use of an armoured tracheal tube as was done in this study minimises the risk of tube compression during surgery which accounted for low incidence. The incidence of laryngospasm and bronchospasm in our study was 10%. Tay2 reported that laryngospasm accounted for 36% of respiratory complications in paediatric anaesthesia and that it occurred most frequently post-induction. In Bordet's3 study, the incidence of bronchospasm and laryngeal spasm in intubated patients was 41%. The lower incidence of laryngospasm in the present series could have been due to our smaller sample size. All episodes of airway spasm occurred in patients who had an inhalational induction. This may reflect the younger age group of the children who had inhalational induction compared to those who had intravenous induction.

The administration of dry gases causes irritation to the airway which predisposes to spasm especially in patients with already hyper-active airway from recurrent infections.

The presence of symptoms of common cold pre-operatively significantly increases the risk of perioperative respiratory complications (PRC).1 We therefore ensured that all our patients were symptom-free, normothermic with normal white cell count and no recent history of cold symptoms. Mamie9 demonstrated a positive association between airway complications and age < 6 years and Murat11 observed that respiratory complications were greater in infants compared to children aged 1–7 years.

The present study did not identify any correlation between airway complication and age as the incidence was similar in both infant and preschool children. Fillies7 on the other hand demonstrated a direct correlation between weight and complications with children weighing 4 – 6 kg having the highest complication rate. We investigated weight as an influencing factor and observed that patients weighing < 5 kg and 5 – 10kg, had similar complication rates which were less than those of heavier children.

Possible explanation could be the inclusion of older children with CP due to late presentation who had their airway managed by trainee anaesthetists who are often permitted to perform anaesthetic techniques on these groups of patients as they are deemed less likely to develop anaesthetic related problems. One limitation of this study was that the grade of anaesthetist who performed tracheal intubation was not investigated. It is however the practice in our institution to have a consultant or senior registrar grade anaesthetist on every elective surgical list.

Our study has emphasised the importance of having skilled personnel, appropriate monitoring equipment and airway devices available during cleft surgeries to minimise morbidity. The use of muscle relaxation for intubation should be advocated after it has been confirmed that the patient can be manually ventilated by facemask as this would provide adequate intubating conditions and prevent laryngeal spasm. A RAE or armoured tube during CP repair would avoid tube compression due to introduction of a mouth gag.

Conclusion

Airway complications are relatively common during cleft surgeries. The incidence of airway complication in the present study was 38% and occurred mostly commonly in patients undergoing cleft palate repair. The most common complication was desaturation, followed by laryngeal spasm and tube disconnection.

References

- 1.Takemura H, Yasumoto K, Toi T, Hosoyamada A. Correlation of cleft type with incidence of perioperative respiratory complications in infants with cleft lip and palate. Pediatr Anesth. 2002;12:585–588. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2002.00906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tay CLM, Tan GM, Ng SBA. Critical incidents in paediatric anaesthesia: an audit of 10 000 anaesthetics in Singapore. Pediatr Anesth. 2001;11:711–718. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2001.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bordet F, Allaouchiche B, Lansiaux S, et al. Risk factors for airway complications during general anaesthesia in paediatric patients. Pediatr Anesth. 2002;12:762–769. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2002.00987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xue FS, Zhang GH, Li P, et al. The clinical observation of difficult laryngoscopy and difficult intubation in infants with cleft lip and palate. Pediatr Anesth. 2006;16:283–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2005.01762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gunawardana RH. Difficult laryngoscopy in cleft lip and palate surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1996;76:757–759. doi: 10.1093/bja/76.6.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nargozian C. The airway in patients with craniofacial abnormalities. Pediatr Anesth. 2004;14:53–59. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.01200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frilles T, Homann C, Meyer U, et al. Perioperative complications in infant cleft repair. Head & Face Medicine. 2007;3:9. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hatch DJ. Airway management in cleft lip and palate surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1996;76:755–756. doi: 10.1093/bja/76.6.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mamie C, Habre W, Delhumeau C, et al. Incidence and risk factors of perioperative respiratory adverse events in children undergoing elective surgery. Pediatr Anesth. 2004;14:218–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2004.01169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kohjitani A, Iwase Y, Sugiyama K. Sizes and depths of endotracheal tubes for cleft lip and palate children undergoing primary cheiloplasty and palatoplasty. Pediatr Anesth. 2008;18:845–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2008.02668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murat I, Constant I, Maud'Huy H. Perioperative anaesthetic morbidity in children: a database of 24 165 anaesthetics over a 30-month period. Pediatr Anesth. 2004;14:158–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2004.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stephen P, Saunders P, Bingham R. Neonatal cleft lip repair: a retrospective review of anaesthetic complications. Pediatr Anesth. 1997;7:33–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.1997.d01-37.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donkor P, Bankas DO, Agbenorku P, et al. Cleft lip and palate surgery in Kumasi, Ghana: 2001–2005. J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18(6):1376–1379. doi: 10.1097/01.scs.0000246504.09593.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hodges SC, Hodges AM. A protocol for safe anaesthesia for cleft lip and palate surgery in developing countries. Anaesthesia. 2000;55(5):436–441. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2000.01371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]