Summary

Introduction

Previous reports have indicated that open angle glaucoma is a major problem in the Upper East region of Ghana. Such reports have shown high prevalence among young patients under the age of 40 years. None has given enough details on the burden, pattern of distribution and extent of changes in the optic nerve head and intraocular pressures. This study aims at addressing these issues in order to highlight the situation.

Methods

Retrospective case series involving review of clinical records of all first-time attendants diagnosed with glaucoma at the Bawku Hospital between October 2003 and December 2005. Case definitions and diagnostic criteria were made to conform as much as possible to the ISGEO and EGS recommendations. Data analysis was done using the Epi-Info software.

Results

Records of 891 eyes of 446 patients were reviewed. Median age was 56 years with 23.6% below 40 years. POAG was diagnosed in 98.4% with 8.3% manifesting the NTG variant. One third (34.1%) of all the patients reported bilaterally blind while half were uniocularly blind. Nearly a third (70.2%) had CDRs>0.8 while more than half (54.9%) had CDRs measured at unity. Males were twice as many as females (65.5% and 34.5% respectively) but blindness sequelae among the latter was twice as much and this was statistically significant (p=0.0008;chi2 test)

Conclusion

late presentation of open angle glaucoma cases is a major problem in this part of Ghana. We recommend a more aggressive approach to tackle the disease and reduce its blindness sequelae.

Keywords: applanation, cupping, glaucoma, gonioscopy, tonometry

Introduction

Glaucoma ranks globally as the second most important cause of blindness, surpassed only by cataract. In 1996, Harry Quigley projected that by 2000, the number of people affected by the disease worldwide would reach 66.8 million with nearly equal proportions of open angle and angle closure variants; globally, approximately 6.7 million people were estimated as blind from glaucoma.1 this figure is currently projected to reach 79.6 million by the year 2020 with bilateral blindness burden of 11.2 million resulting from both open angle and closed angle glaucomas alone.1 In Ghana and indeed in most developing countries, it is the leading cause of irreversible blindness, and current reports show that the open angle form of the disease affects some 8.5% of people aged 40 years and above and 7.7% of those 30 years and above.2 These findings are among the highest in the world and only comparable to those estimated in the St. Lucia and the Barbados Eye Studies.3,4 In addition, previous studies have reported that between 22 and 26 percent of all patients operated for glaucoma at the Bawku Hospital in northeastern Ghana are below the age of 40 years.6–8 However, despite these disturbing figures there is currently no nation-wide program to tackle the disease in the country. The study aims at determining the burden and presentation patterns of primary open angle glaucoma, using hospital-based data to highlight the need to develop nationwide intervention strategies to tackle the disease.

Material and Methods

Study Design

This is a retrospective case series involving a review of the clinical records of all first-time attendants diagnosed with glaucoma at the Bawku Hospital between October 2003 and December 2005. Information collected included basic demographic data, measured intraocular pressures, anterior chamber angle configuration and optic disc measurements. In line with the ‘Opportunistic Glaucoma Screening Policy' of the hospital, all patients above the age of 15 years had glaucoma evaluation. Where indicated, (positive family history, history of chronic steroid use) patients younger than 15 also underwent screening.

Outcome Measures

The principal outcome measure, Glaucoma, was diagnosed using a two-stepped approach.

Initial screening phase was undertaken by experienced ophthalmic nurses using specific criteria for suspect glaucoma. These criteria included: intraocular pressure (IOP)>21, vertical cup to disc ration (vCDR)>0.3 and the presence of a relative afferent papillary defect (RAPD), either in combination or in single presentations all suspected cases were referred for further evaluation by the ophthalmologist who then performed applanation tonometry, gonioscopy and stereoscopic disc assessment. Visual fields evaluation was done using the Friedmann field Analyzer.

Definitions and Diagnosis Criteria

In this study, glaucoma case was defined to conform, as much as possible to the recommendations of the Working Group for Defining Glaucomas in Prevalence Studies (International Society of Geographical and Epidemiological Ophthalmology [ISGEO]). In specific cases of Gluacoma Suspects, the European Glaucoma Study (EGS) Guidelines were used and these two systems were complimentary. Simplified version of the ISGEO categorizations are shown in Box 1.

Box 1.

ISGEO Categorizations used in Glaucoma prevalence studies

| Category | Structural Abnormality | Visual Fields Abnormality |

| 1 | Eyes with a CDR or CDR asymmetry ≥97.5th percentile for the normal population, or NRR width reduced to ≤0.1CDR (between 11 to 1 o'clock or 5 to 7 o'clock). | Present |

| 2 | Advanced structural damage with CDR or CDR asymmetry ≥99.5th percentile for the normal population | Not proven |

| 3 | Optic disc not seen but visual acuity <3/60 and IOP>99.5th percentile or visual acuity <3/60 with evidence of glaucoma filtering surgery or medical records of glaucomatous visual morbidity | Not possible |

A Gluacoma patient herein was defined as a person who met any of the ISGEO categorizations in either one or both eyes. In each case classification into open or closed angle type was based on recorded gonioscopic findings. Where gonioscopy was neither done nor recorded the case was taked as open angle glaucoma. Normal Tension Glaucoma (NTG) on the other hand was defined as a case of open angle glaucoma in which the IOP was measured consistently below 22mmHg in the absence of ocular hypotensive medications.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients who had undergone cataract surgery or glaucoma filtering procedures, or those already on glaucoma medication were excluded from this study. Also excluded were patients with congenital glaucomas.

Standardization of the Age Structure

We were unable to capture the complete age structure of all new patients who attended the clinic. However, since most of these patients were from the UER we elected to use the regions population structure to standardize that of the visiting glaucoma cohort. To do this we applied the computed age structure of the population of the UER in the Ghana 2000 Population and Housing Census Report to this cohort. Using this structure we extracted the population of each of the nine age groups for which the glaucoma cases were distributed. Figure 1 shows the age-specific distribution of glaucoma among the visiting population.

Statistical Analysis

All the required information was entered onto a pre-designed Microsoft Excel template and analysis done using the Epi Info Software (Revision 2, January 30 2003 Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta Georgia). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics of the studied subjects. Ages of the patients were summarized using the mean, standard deviation and the median was also reported. Comparison of strength of associations was done using Chi2 test of significance. All statistical tests were two-sided with an alpha level of <0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Distribution of Glaucoma Types

In all 446 records of patients (891 eyes) who had been diagnosed with open angle glaucoma and met the set of inclusion criteria were included in the study. Nearly all the patients (98.4%) diagnosed with glaucoma in this referral centre had a primary form of the disease with 77.8% presenting with the ‘classical’ open angle type (POAG). Nearly one out of every ten persons (8.3%) seen was found to have the normal tension variant of POAG while 1.1% presented with a combination of NTG in one eye and POAG in the other. All the secondary glaucomas were unilateral and made up of uvetic glaucoma (2), aphakic glaucoma (1) and phacolytic glaucoma (2). Causes of glaucoma in two cases could not be identified (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of glaucoma cases among subtypes

| Glaucoma Type | Unilateral | Bilateral | Total | |||

| No | % | No | % | No | % | |

| POAG | 16 | 3.6 | 331 | 74.2 | 347 | 77.8 |

| POAG ‘Suspect’ | - | - | 30 | 6.7 | 30 | 6.7 |

| NTG | - | - | 37 | 8.3 | 37 | 8.3 |

| NTG ‘Suspect’ | - | - | 20 | 4.5 | 20 | 4.5 |

| Mixed Presentations | - | - | 5 | 1.1 | 5 | 1.1 |

| Secondary Glaucoma | 7 | 1.7 | - | - | 7 | 1.7 |

| Total | 23 | 5.3 | 423 | 94.8 | 446 | 100 |

POAG: Primary Open Angle Glaucoma

NTG: Normal Tension Glaucoma

Glaucoma and Blindness

About one third, 34.1% (n=152) of the patients were bilaterally blind (defined as best corrected visual acuity <3/60 in the better eye) at presentation while approximately half were uniocularly blind. The right eye was recorded blind in 51.3% of cases and the left eye in 52.2% cases at presentation. This difference was not statistically significant. (p=0.84 chi2 test).

Age and Sex Distribution

The mean age of the studied population was 53.2 years (median of 56) and a standard deviation of 16.3. The youngest patient was 9 years and the oldest 87. About a quarter (23.6%) of subjects identified with glaucoma were below the age of 40years. There were nearly twice as many males (n=292[65.5%]) diagnosed with glaucoma compared to females (n=154 [34.5%]. There were, however, twice the risk of women becoming blind from glaucoma than men, and this association was statistically significant (p-value=0.0008; odds Ration 2.04; 95%CI 1.36–7.07). Table 2 shows the age and sex distribution patterns of the subjects studied.

Table 2.

Age and Sex Distribution of Subjects Examined

| Age (years) |

Male | Females | Total | |||

| No. | % | No | % | No | % | |

| 1–20 | 11 | 3.7 | 8 | 5.2 | 19 | 4.3 |

| 21–40 | 60 | 20.5 | 24 | 15.7 | 84 | 18.8 |

| 41–60 | 118 | 40.3 | 66 | 43.1 | 184 | 41.3 |

| 61–80 | 102 | 34.9 | 54 | 35.3 | 156 | 35.0 |

| >80 | 2 | 0.68 | 1 | 0.65 | 3 | 0.67 |

| All ages | 293 | 100 | 153 | 100 | 446 | 100 |

Glaucoma pattern and age structure

The prevalence of glaucoma increased exponentially from the age of nine years peaking between the ages of 51 and 60 years (24.7%) and tapering off thereafter. Using the standardized age distribution similar trend was observed with peak incidence between the ages of 60 and 69 years. Prevalence among patients aged 40 years and above was computed at 5.1% and that of patients aged 30 years and above at 4.0%. Figure 1 shows the prevalence pattern among the various age groups.

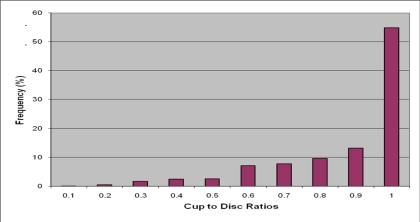

Glaucomatous Optic Disc Abnormalities

More than seventy percent (70.2%) eyes had cup to disc ratio greater than 0.8 while 54.9% had a CDR of 1. Chart 2 shows the distribution patterns.

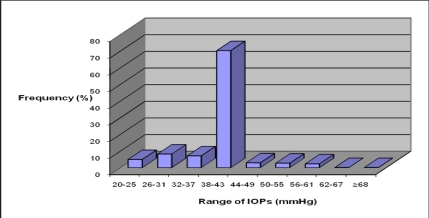

Intraocular Pressure

The arithmetic mean Goldman IOP for the right eye was measured at 34.7 mm Hg (SD=10.9) with a range of 10.0–68 mmHg. That of the left eye was measured at 35.0 mmHg (SD=10.9) with a range of 4.5–69mmHg. In addition 59.8% of measured IOPs in the right eye were above 40mmHg while 60.1% measured in the left eye were above same.

When the POAG cases were analyzed separately, mean IOP for the right eye was 39.4mmHg (SD=6.9) with a range of 22.4 to 68.0mmHg while that of the left eye was 39.7mmHg (SD=6.7) with a range of 22.4 to 69.0mmHg. with the two eyes put together, the mean Goldmann IOP for (all the eyes was 39.5mmHg with Standard Deviation of 6.9mmHg. The relationship between high intraocular pressure (IOP>30mmHg) and end stage disc excavation (vCDR=1.0) was found to be statistically significant (p=0.0001; 95% CL: 0.09–0.17). Figure 3 shows the distribution patterns of the measured IOPs in both eyes (n=681 eyes).

Figure 3.

Distribution of Intraocular Pressures in eyes diagnosed with POAG

Discussion

The manifestation of glaucoma in Black populations is different from that in Caucasians: predominantly open angle in nature, early onset, high IOP at the time of presentation and relatively more aggressive course leading to early blindness. Lack of glaucoma awareness and education as well as poor access to care is largely responsible for the high blindness sequelae. In this study 34.1% of the patients were bilaterally blind at presentation, between 51.3 and 52.2% were blind in one eye while 69.7% had vertical CDR>0.8. These findings are similar to others reported in Black African population's elsewhere. In a hospital-based study in Nigeria 53% of eyes treated for glaucoma were blind at the time of first presentation while 63% had vertical CDR greater than 0.8 in the better eye. In a similar study in Tanzania, 29% of patients were diagnosed blind at presentation while 70% had vertical CDR greater than 0.8 in the better eye.

The mean age of onset of POAG is usually lower in African populations than in Causcasians. In this study the mean age of 53.2 years is similar to those reported in other hospital-based studies in Nigeria (52.7years), Cameroun (53.3 years) and Ethiopia (51.9 years). The high prevalence of POAG among young patients in this population has also been reported in previous studies. The 23.6% prevalence measured in patients 40 years or younger is similar to those reported by Wormald and Foster (1991), Verrey et al (1991) 7 and Gyasi et al (006) in patients who underwent filtering procedures for glaucoma in the region. These findings underscore the burden of disease in the region, and highlight the necessity of including patients younger than 30 in glaucoma screening programmes.

Similar findings have been reported in an Ethiopian study in which 22% of the patients were reported to be 40 years or younger with a peak incidence between the ages of 51 to 60 years. This peak incidence is similar to that measured in our current study (51–60 years group) and strikingly different from the seventh decade peak measured by Omoti et al in a Benin City study. In our study the incidences tapered dramatically in the 7th decade. These variations may partly be explained by demographic and health care delivery system variations in the various settings.

The influence of gender on glaucoma has not been as straightforward as may be expected from the generally skewed elevation in IOP among women after 40years of age. Results from different prevalence studies have not been conclusive in showing gender preponderance as some studies report male prevalence of POAG to be twice as high as females or vice versa, while others report no sex association at all. Our findings parallel similar hospital-based studies in Nigeria and Ethiopia where rations of 2:1 in favour of men were measured.

In a Tanzanian study this ration went as high as 2:6:1. In a population-based study in Southern Ghana, Ntim Amponsah et al (2004) found slight risk preponderance towards males for advanced glaucoma; these were however not significant at both the invariant and multivariate levels. The striking feature of this present study, however, is that despite the higher preponderance of male patients with POAG, the females were more than twice likely to become blind from the disease. These findings probably reflect the socio-cultural aspects of male dominance in a many African societies where men control the family wealth and are more likely to have the upper hand in assessing ‘pay —for-health’ care services.

Intraocular pressure remains the most significant risk factor for the glaucomas and indeed the only one that can currently be modulated. The mean intraocular pressure among Ghanaians has been measured at 14.41mmHg. In this study 60% of eyes have IOPs measured 25 units above this normative Ghanaian, mean (above 40mmHg) and this is disturbing as it does not only give a poor indication of our glaucoma status but also a worrisome delay in seeking help.

The relationship between IOPs and the common pathway to nerve damage in glaucoma is no longer a subject of dispute. In a risk factor analysis on glaucomatous eyes from the Akwapim South district of Ghana, the authors found a significant correlation between high IOPs and advanced glaucoma. In this study advanced glaucoma was prosy-measured with ‘absolute’ disc excavation and similar relationships were also noted (p=0.0001; 95% cl:0.9–0.17) and these findings bring into sharp focus the need to develop a comprehensive, safe and effective IOP reduction intervention programme for one of the largest glaucoma burdens in the world.

How this should be done would however become clearer when the on-going Tema Eye Survey and the medical management of glaucoma studies are completed.

The high incidence of blindness from glaucomas in Ghana has been extensively discussed in Peter Egbert's Paper. The reasons are not only due to the aggressive nature of the disease and late presentation among Black patients but also the woefully inadequate number and distribution of ophthalmologists who can perform trabeculectomies (the most effective intervention) as a regular treatment option. In a recently published mid- Volta blindness prevalence study in Ghana, Guzek et al (2005) estimated that glaucoma accounted for a fifth (20.6%) of all causes of blindness. In this report more than a third of the patients were bilaterally blind at presentation whilst more than half uniocularly blind. The high incidence of absolute disc excavations (55%) only compounds the situation as many of these would have been measured blind had visual fields been included in defining blindness. As such the blindness estimates from this study represent an underestimation of the problem.

This study did not look at the effects of rural dwelling on the blinding sequelae of glaucoma nor did it look into the possibility of other potentially blinding conditions like onchocerciasis complicating the course of the glaucomas. There are reports supporting the fact that glaucoma presentation is usually worse in rural people compared to urban folds in Ghana. In one of such studies the author measured blindness in newly diagnosed glaucoma patients from rural areas to be worse than those from urban areas and this was attributed to local factors such as better access to health care among urban populations. In the Upper East region however, excellent eye care services have been available since 1975 and this is evidenced in our recent reports on barriers to cataract services uptake in which knowledge of eye care services was almost 100% among the respondents. It appears that more work, especially in glaucoma awareness creation, needs to be done.

There is also growing evidence supporting the association between onchocerciasis and glaucoma. In a recently published works from Ghana, the authors reported glaucoma subjects to have more than three times the odds of testing positive for onchocerciasis compared to controls after adjusting for variables like age, sex and location (OR, 3.50(95%CI 1.10 to 11.18). This study did not look into this phenomenon but given the facts that the studied subjects lived in one of the major onchocerciasis zones in West Africa the need to have look into this cannot be over-emphasized especially in the light of high prevalence of blindness sequelae among the subjects.

Limitations

In this study we were unable to determine what proportion of the large number of cases aged less than forty years are due to classical juvenile glaucomas and this needs to be looked at in further studies due to their more aggressive course and genetic implications.

This study most likely has underestimated the prevalence of glaucoma in the region as patients previously on glaucoma treatment were excluded. This is supported by the slightly lower prevalence figures in this study compared to results from population based studies elsewhere in the country. Perhaps similar population-based surveys may throw more light onto the exact glaucoma prevalence situation in this part of Ghana.

Morbidity from POAG in this population appears to be very high. The high prevalence among the economically productive age groups gives a course for concern and this situation is likely to be worse in many parts of Ghana as the Upper East region has much better eye care services than many other parts of the country. It is therefore recommended that health care planners in the country develop a structured and effective control measures to reduce the high level of blindness from the glaucomas. This is likely to be effective only when glaucoma is put on the National Vision 2020, the Right to Sight programmes and given the needed push.

Figure 2.

Distribution of Cup to Disc Ratios across the study population

References

- 1.Quigley HA. Number of people with glaucoma worldwide. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80:389. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.5.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(3):262–267. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.081224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ntim-Amponsah CT, Amoaku WM, Ofosu-Amaah S, Ewusi RK, Idirisuriya—Khair R, Nyatepe-Coo E, Adu-Darko M. Prevalence of glaucoma in an African population. Eye. 2004;18:491–497. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mason RP, Kosoko O, Wilson MR, et al. National Survey of the prevalence and risk factors of glaucoma in St. Lucia, West Indies. Part 1. Prevalence findinfs. Ophthalmology. 1996;96:1363–1368. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32708-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leske MC, Connell AMS, Schacht AP, et al. The Barbados Eye Study. Prevalence of open angle glaucoma. Arch Ophtalmol. 1994;112:821–829. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090180121046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wormald R, Foster A. Clinical and pathological features of chronic glaucoma in north-east Ghana. Eye. 1990;4:107–114. doi: 10.1038/eye.1990.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verrey J D, Foster A, Wormald R, Akuamoah C. Chronic Glaucoma in Northern Ghana - a Retrospective study of 397 patients. Eye. 1990;4:115–120. doi: 10.1038/eye.1990.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gyasi ME, Amoaku WMK, Debrah OA, Awini E, Abugri P. Outcome of trabeculectomies without adjunctive antimetabolites. Ghana Med J. 2006;40(2):39–44. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v40i2.35986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster PJ, Burhmann R, Quigley HA, Johnson GJ. The definition and classification of glaucoma in prevalence studies. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;(86):238–242. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.2.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.European Glaucoma Society, author. Terminology and guidelines for Glaucoma. 11th ed. European Glaucoma Society; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowman JC, Subramaniam K. How to manage a patient with glaucoma in Africa. J Comm Eye Health. 2006;19(59):38–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mafwiri M, Bowman RJ, Kabiru J. Primary open-angle glaucoma presentation at a tertiary unit in Africa: intraocular pressure levels and visual status. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2005;12(5):299–302. doi: 10.1080/09286580500180572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Omoti AE, Osahon AI, Waziri-Erameh MJ. Pattern of presentation of primary open-angle glaucoma in Benin City, Nigeria. Trop Doc. 2006;36(2):97–100. doi: 10.1258/004947506776593323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellong A, Mvogo CE, Bella-Hiag AL, Mouney EN, Ngosso A, Litumbe CN. Prevalence of glaucomas in a Black Cameroonian population. Sante. 2006;16(2):83–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melka F, Alemu B. The pattern of glaucoma in Menelik II Hospital Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2006;44(2):159–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Epidemiology of Eye Disease. Gordon Johnson and Darwin C. Minassian and Robert Weale; Chapman and Hall Medicine. p. 175. Primary Open Angle Glaucoma: Demographic Risk Factors. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ntim-Amponsah CT. Mean intraocular pressure in Ghanaians. East Afr Med J. 1996;73(8):516–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ntim-Amponsah CT, Amoaku WM, Ofosu-Amaah S, Ewusi RK, Idirisuriya-Khair R, Nyatepe-Coo E. Evaluation of risk factors for advanced glaucoma in Ghanaian patients. Eye. 2004:1–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701533. 00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egbert PR. Glaucoma in West Africa; a neglected problem. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86(2):131–132. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.2.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guzek JP, Anyomi FK, Fiadoyor S, Nyonator F. Prevalence of blindness in people over 50 years in the Volta Region of Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2005;39 doi: 10.4314/gmj.v39i2.35983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gyasi ME, Amoaku WMK, Asamany DK. Barriers to cataract surgical uptake in the Upper East Region of Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2007;41:167–170. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v41i4.55285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Egbert PR, Jacobson DW, Fiadoyor S, Dadzie P, Ellingson KD. Onchocerciasis: a potential risk factor for glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005 Jul;89(7):789–790. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.061895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]