Abstract

Phlegmonous gastritis is an acute and severe infectious disease that is occasionally fatal if the diagnosis is delayed. Alcohol consumption, an immunocompromised state (e.g., due to HIV infection, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus, or adult T-cell lymphoma), and mucosal injury of the stomach are reported to be predisposing factors. The main treatments for phlegmonous gastritis are antibiotics administration or surgery. In this case, the patient's stomach was markedly distended due to long-lasting gastric-outlet obstruction, which is thought to be the predisposing factor for phlegmonous gastritis. We inserted a metal stent at the obstructed site palliatively due to strong refusal by the patient for surgery. The patient recovered after stenting and antibiotic therapy.

Keywords: Phlegmonous gastritis, Gastric outlet obstruction

INTRODUCTION

Phlegmonous gastritis (PG) is a disease that is caused by bacterial infection of gastric wall.1,2 This condition is rare but when it occurs, it's prognosis seems to be poor. In the pre-antibiotic era, the treatment of choice was gastrectomy and then, the mortality of PG was high.1 Recently early diagnosis and aggressive antibiotic therapy are common, and these had improved the outcomes without surgery. The predisposing factors are diverse.3 Often previously healthy persons are affected. In this case, the patient with PG previously had marked distension of stomach due to duodenal stricture. So, we report this case and review English language publications.

CASE REPORT

A 73-year-old woman presented with abdominal distension, epigastric pain, vomiting and hypotension. Her initial blood pressure was 60/40 mm Hg and body temperature was 37.5℃. Her abdomen was markedly distended. Physical examination revealed tympanic sound and tenderness on epigastrium without muscle guarding or rebound tenderness. Dark-colored fluid was out through the Levin tube. She had suffered from gastric outlet narrowing for eighteen years. Duodenal malignancy was suspected at the beginning. However no evidence of malignancy was found during follow up. She refused surgery. Initial laboratory data were as followed. WBC 14,860/mm3, AST 1,074 IU/mL, ALT 4,444 IU/mL, albumin 2.6 g/dL, Amylase 557 IU/mL, p-amylase 129 IU/mL, Lipase 12 IU/mL, and CRP 18.91 mg/dL. Hepatitis B and C markers were negative. The simple abdominal X-ray showed remarkably distended gaseous stomach (Fig. 1). Our presumptive diagnosis was to rule out infection of gastrointestinal tract, and sepsis. Broad spectrum antibiotics and fluid infusion were administered. Initial non-enhanced computed tomography (CT) showed distended stomach and nonspecific liver and pancreas. Contrast enhanced CT after gastric decompression showed diffuse thickening of gastric wall (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Simple abdominal X-ray showing marked distension of the stomach.

Fig. 2.

Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography showing a thickened gastric wall.

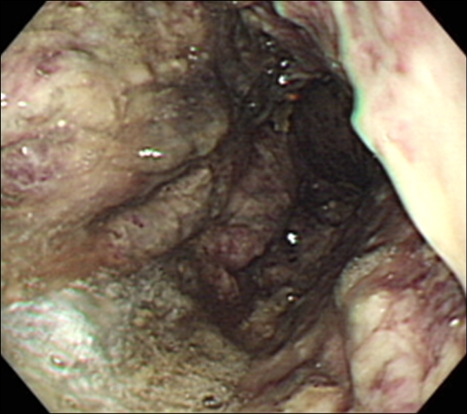

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy on the sixth hospital day showed dark-colored fluid retention in the stomach. The gastric mucosa was dark-purple colored, thick, and friable. Several ulcerations were noted (Fig. 3). The esophagus was normal. The pyloric ring showed pin-point narrowing. Because the patient refused surgery, we inserted metal stent to decompress the narrowed pyloric ring. The culture of several biopsy specimens taken from the endoscopic examinations revealed Escherichia coli and Acinetobacter calcoacet. Histopathologic examination revealed necrotic detritus, neutrophilic exudates, heavy infiltration of inflammatory cells and granulation tissues. Serial endoscopy showed improvement of gastric mucosa (Fig. 4). The patient had recovered and discharged on the 35th hospital day. Three months later, the patient was suffering from vomiting due to narrowing of the inserted stent, and anemia caused by continuous minimal bleeding from chronic ulceration. As a result, she took gastrojejunostomy and vagotomy.

Fig. 3.

Upper endoscopy revealing a dark-purple-colored, thickened gastric mucosa.

Fig. 4.

Upper endoscopy after recovery showing a pink-colored gastric mucosa with healing ulcers.

DISCUSSION

Phlegmon means diffusely spreading inflammation of connective tissue. Gastric phlegmon shows variable clinical features such as acute PG,3-6 gastric gangrene (necrotizing gastritis),7,8 gastric intramural abscess (localized form),9-11 and infectious emphysema of gastric wall (by gas-forming bacteria).12-14 The common clinical features of PG is bacterial infection mainly at gastric submucosa.

PG is apparently related to septicemia or mucosal injury. Mucosal injury might be associated with alcohol consumption, chronic gastritis, trauma, and taking chemicals, drugs, and toxins.2,9,15 Gastric ulcer or cancer is also associated with PG in several cases.2 Septicemia related with bacterial endocarditis, erysipelas, furunculosis, staphylococcal osteomyelitis, tooth extraction, and puerperal sepsis were reported to be related with PG.3 And this condition is also reported to be common with immunocompromised patients.16,17 In some cases, no specific predisposing factors of PG were found. In this case, the overt enlargement of stomach due to duodenal obstruction is strongly suggested as the predisposition of stasis of gastric juice, bacterial growth, and infection of the gastric wall.

The usual clinical presentation of PG is severe and acute epigastric pain.1,3,4 Rebound tenderness or muscle guarding is rare except in advanced cases.5 Fever, vomiting, increased pulse rates are common findings.1 The condition is usually misdiagnosed as more common acute surgical problems such as perforated peptic ulcer or cholecystitis. Usually serum amylase level differentiates acute pancreatitis from other acute abdominal illness. However this case shows that serum amylase can be elevated in PG. Septic condition and gastrointestinal tract mucosal injury might cause the elevation of amylase and aminotransferases.

PG can be diagnosed by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, CT scan, or endoscopic ultrasound (EUS).3,9,13,18 It's endoscopic findings can show purple colored gastric mucosa covered with dirty necrotic materials,3 however, esophagus and duodenum are rarely involved.3,19-21 On CT scan, markedly thickened gastric wall can be seen in PG, and collection of air is seen in emphysematous cases.3,12,18,22 CT findings in the setting of an acute epigastric inflammatory condition, PG can be diagnosed and then, urgent antibiotic treatment is needed.

The pathogens are revealed by the culture of gastric aspirates or tissue.1 In Gerster's report, streptococci are the most frequently found organism (70%).2 Staphlyococci, pneumococci, Bacteroides coli, Bacteroides subtilis are also found.2,23

Usual pathologic findings are thickened submucosa due to infiltration by neutrophils and plasma cells.3 In advanced cases, there were intramural hemorrhage, necrosis, or thrombosis of the submucosal blood vessels.7 If the inflammation is localized, abscess formation is possible.

Starr et al.1 analyzed 25 cases with PG after 1945 when antibiotics were available. Overall mortality was 48%. Six of 8 patients died after subtotal gastrectomy. And reported mortality of the 8 patients who were treated with antibiotics only was 50%. The common factors in all of the survivors were the early recognition and the prompt antibiotic treatment or surgery. Kim et al.2 reviewed 36 cases of PG between 1973 and 2003. The mortality rate for surgically treated patients vs medically treated ones were 20% (2/10) and 50% (13/26). And that for localized disease vs diffuse one was 10% (1/10) and 54% (14/26). There was no correlation between mortality and age or gender. So PG can be treated conservatively with antibiotics and intravenous fluid infusion, if the disease is diagnosed in early phase. Otherwise, surgical management should be considered.

In conclusion, we described a case of PG associated with gastric distension. Through early diagnosis and gastric decompression, this patient was treated successfully.

References

- 1.Starr A, Wilson JM. Phlegmonous gastritis. Ann Surg. 1957;145:88–93. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195701000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim GY, Ward J, Henessey B, et al. Phlegmonous gastritis: case report and review. Gastrointes Endosc. 2005;61:168–174. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02217-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerster JC. Phlegmonous gastritis. Ann Surg. 1927;85:668–682. doi: 10.1097/00000658-192705000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schultz MJ, van der Hulst RW, Tytgat GN. Acute phlegmonous gastritis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:80–83. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70236-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner MA, Beachley MC, Stanley D. Phlegmonous gastritis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1979;133:527–528. doi: 10.2214/ajr.133.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watson WL. Phlegmonous gastritis. Am J Surg. 1932;18:113–122. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strauss RJ, Friedman M, Platt N, Gassner W, Wise L. Gangrene of the stomach: a case of acute necrotizing gastritis. Am J Surg. 1978;135:253–257. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(78)90111-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franklin RG. Acute necrotizing phlegmonous gastritis. Calif Med. 1962;96:283–284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwakiri Y, Kabemura T, Yasuda D, et al. A case of acute phlegmonous gastritis successfully treated with antibiotics. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;28:175–177. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199903000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cruz FO, Soffia PS, Del Rio PM, Fava MP, Duarte IG. Acute phlegmonous gastritis with mural abscess: CT diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:767–768. doi: 10.2214/ajr.159.4.1529840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy JF, Graham DY, Frankel NB, Spjut HJ. Intramural gastric abscess. Am J Surg. 1976;131:618–621. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(76)90028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung JH, Choi HJ, Yoo J, Kang SJ, Lee KY. Emphysematous gastritis associated with invasive gastric mucormycosis: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22:923–927. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2007.22.5.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soon MS, Yen HH, Soon A, Lin OS. Endoscopic ultrasonographic appearance of gastric emphysema. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1719–1721. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i11.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sawyer RB, Sawyer KC, List JE. Infectious emphysema of the gastrointestinal tract in the adult. Am J Surg. 1970;120:579–583. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(70)80171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosen Y, Won OK. Phlegmonous enterocolitis. Am J Dig Dis. 1978;23:248–256. doi: 10.1007/BF01072325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rutherford PS, Berkeley JA. Phlegmonous gastritis in a cortisone-treated patient. Can Med Assoc J. 1953;69:68–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zazzo JF, Troché G, Millat B, Aubert A, Bedossa P, Kéros L. Phlegmonous gastritis associated with HIV-1 seroconversion. Endoscopic and microscopic evolution. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:1454–1459. doi: 10.1007/BF01296019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu DC, McGrath KM, Jowell PS, Killenberg PG. Phlegmonous gastritis: successful treatment with antibiotics and resolution documented by EUS. Gastrointes Endosc. 2000;52:793–795. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.108926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsu CY, Liu JS, Chen DF, Shih CC. Acute diffuse phlegmonous esophagogastritis: report of a survived case. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43:1347–1352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cordum NR, Dixon A, Campbell DR. Gastroduodenal pneumatosis: endoscopic and histological findings. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:692–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung C, Choi YW, Jeon SC, Chung WS. Acute diffuse phlegmonous esophagogastritis: radiologic diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:862–863. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.3.1800862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joko T, Tanaka H, Hirakata H, et al. Phlegmonous gastritis in a haemodialysis patient with secondary amyloidosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:196–198. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.1.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morton JJ, Stabins SJ. Phlegmonous gastritis: of Bacillus aerogenes capsulatus (B. Welchii) origin. Ann Surg. 1928;87:848–854. doi: 10.1097/00000658-192806000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]