Abstract

Purpose

The goals of this study were (1) to compare the injury at the basement membrane zone (BMZ) of rabbit corneal organ cultures exposed to half mustard (2 chloroethyl ethyl sulfide, CEES) and nitrogen mustard with that of in vivo rabbit eyes exposed to sulfur mustard (SM); (2) to test the efficacy of 4 tetracycline derivatives in attenuating vesicant-induced BMZ disruption in the 24-h period postexposure; and (3) to use the most effective tetracycline derivative to compare the improvement of injury when the drug is delivered as drops or hydrogels to eyes exposed in vivo to SM.

Methods

Histological analysis of hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections was performed; the ultrastructure of the corneal BMZ was evaluated by transmission electron microscopy; matrix metalloproteinase-9 was assessed by immunofluorescence; doxycycline as drops or a hydrogel was applied daily for 28 days to eyes exposed in vivo to SM. Corneal edema was assessed by pachymetry and the extent of neovascularization was graded by length of longest vessel in each quadrant.

Results

Injury to the BMZ was highly similar with all vesicants, but varied in degree of severity. The effectiveness of the 4 drugs in retaining BMZ integrity did not correlate with their ability to attenuate matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression at the epithelial–stromal border. Doxycycline was most effective on organ cultures; therefore, it was applied as drops or a hydrogel to rabbit corneas exposed in vivo to SM. Eyes were examined at 1, 3, 7, and 28 days after exposure. At 7 and 28 days after SM exposure, eyes treated with doxycycline were greatly improved over those that received no therapy. Corneal thickness decreased somewhat faster using doxycycline drops, whereas the hydrogel formulation decreased the incidence of neovascularization.

Conclusions

Corneal cultures exposed to 2-chloroethyl ethyl sulfide and nitrogen mustard were effective models to simulate in vivo SM exposures. Doxycycline as drops and hydrogels ameliorated vesicant injury. With in vivo exposed animals, the drops reduced edema faster than the hydrogels, but use of the hydrogels significantly reduced neovascularization. The data provide proof of principle that a hydrogel formulation of doxycycline as a daily therapy for ocular vesicant injury should be further investigated.

Introduction

Injuries from vesicants range from mild to severe, depending on the agent, its concentration, and the length of time the eyes, skin, or lungs are exposed. The effects of exposure are not felt immediately, but take 2–4 h to manifest (for reviews, see Smith and Dunn1 and Papirmeister et al.2). Sulfur mustard (2,2-dichlorodiethyl) sulfide is considered a likely agent to be used by terrorists.3 Components for its synthesis are inexpensive, and the synthetic protocol is relatively easy. In addition, as a warfare agent, SM is extremely effective because even mild ocular exposures cause visual disturbances, panic, and a fear of blindness that cannot be underestimated. Unlike the skin, the cornea does not blister after exposure to vesicants. Instead, microbullae are formed at the basement membrane zone (BMZ). These microbullae are focal separations between the epithelial and stromal cell layers, with disruption of the BMZ. Most of the research devoted to the search for therapies for SM injury has been directed toward skin exposures. However, the Iraqi use of SM in the 1985–1988 Iran-Iraq war prompted Iranian ophthalmologists to record the range of ocular injuries incurred by their exposed troops.4–12 This has highlighted the global need for ocular therapies against SM exposure. Even after 100 years of study, there are still no U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved countermeasures against vesicant exposures, whether to the eye, skin, or lung.

We have used a corneal organ culture model for 2-chloroethyl ethyl sulfide (CEES or half mustard) and mechlorethamine–HCl [nitrogen mustard (NM)] exposures, to induce a range of vesicant injuries and to evaluate whether the injuries sustained at the BMZ are similar to that induced by in vivo SM exposures. Our goal was to determine whether the organ cultures are useful as a tool for prescreening potential vesicant therapies. An air–liquid interface (air lifted) organ culture technique is the most appropriate model because it maintains the differentiated corneal epithelial phenotype, and by having both the epithelial and stromal cell layers, the organ culture retains a BMZ, a major target area for vesicant exposure. Such corneal organ culture models have been used for wound healing studies and have been tested for epithelial, endothelial, and stromal cell viability under a variety of conditions.13,14

The recent report evaluating healing of rabbit eyes exposed in vivo to SM followed by treatment with the tetracycline derivative doxycycline15 suggested that tetracyclines in general might be useful therapies. Here we show that corneal organ cultures can be used for the preliminary evaluations of drugs. Four tetracycline derivatives were applied to the organ-cultured corneas during the 24 h after a 2-h CEES or NM exposure, and then the corneas were analyzed for BMZ integrity. As doxycycline proved most effective in the cultures, and as we had previously demonstrated that hydrogel delivery was feasible in cultures,16 an animal study was performed. Rabbit eyes were exposed in vivo to SM, followed by the delivery of doxycycline as drops 3 times per day, or as a hydrogel formulation applied once daily. Rabbit eyes were analyzed at 24 h, but because of the greater extent of injury with SM, analyses were also done at 3, 7, and 28 days after exposure. Our data provide proof of principle that doxycycline drops or a once daily hydrogel containing doxycycline should be pursued as a potential therapy for ocular mustard exposure.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Rabbit eyes were purchased from Pel-Freez Biologicals. Agar, ciprofloxacin, HEPES buffer, RPMI 1640 vitamin solution, ascorbic acid, Mayer's hematoxylin, CEES (half mustard) liquid (cat. no. 242640), and NM powder (cat. no. 122564) were obtained from Sigma. High-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), 100 × MEM-NEAA, goat anti-mouse Alexa 488-tagged IGg, TRITC, DAPI, and Prolong Gold were obtained from Invitrogen. Pen-Fix was from Richard Allen Scientific. Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and MMP-9 antibodies were purchased from Millipore. Normal goat serum was obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch. Optimal cutting temperature (OCT) embedding medium was from TissueTek. Hematoxylin was from Fluka. Doxycycline hyclate was obtained from Greenpark Pharmacy. Sancycline was from Hovion Farma Ciencia SA. For hydrogels, the polymers 8-arm-poly ethylene glycol (PEG)-thiol (20 kDa) and 8-arm PEG-N-hydroxysuccinimide (20 kDa, 95.1% total activity by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) were custom synthesized by NOF Corporation.

Organ culture of corneas

Whole eyes from young adult rabbits (8–12 weeks old) were purchased from Pel-Freez and were shipped in DMEM with penicillin, streptomycin, gentamicin, and amphotericin B. Corneas and 2–3 mm of scleral rim were dissected from the eye, and the rest of the eye was discarded. Immediately after dissection, corneas were placed in DMEM and 20 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4). Corneas were placed endothelial side up into a spot plate containing 10 μL of DMEM, and a 55°C solution of 0.75% agar in DMEM was added to the cornea and allowed to solidify for 4 min. The cornea was then flipped over into a glass culture dish (Pyrex), then high-glucose DMEM containing 1 × MEM-NEAA, 1 × RPMI 1640 vitamin solution, 0.01 mg/mL ciprofloxacin, and 0.1 mg/mL ascorbic acid was added up to the corneal-scleral rim. Corneas were allowed to sit overnight in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator to equilibrate and were moistened with medium on the evening of dissection and the next morning before exposure to CEES or NM.

Exposure of cultured corneas to vesicants

To induce mild injury, CEES was used. Twenty-four μL of 98% CEES liquid was initially dispersed into 76 μL of 100% ethanol (final concentration of CEES = 2 M). One microliter of this CEES/ethanol solution was added to 2 mL media, making the final ethanol concentration 0.05%, a level not harmful to cells, and the CEES concentration 1 mM. To the central cornea of each culture, 20 μL of the CEES solution was applied (i.e., 20 nmol/cornea). Control corneas received the same volume of medium.

To induce moderate-to-severe injury, NM was used. Milligram amounts of NM powder (98%; Sigma; cat. no. 122564) were added to amber vials for storage at −80°C until use. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was added to vials to make the NM concentration 100 mM. The NM solution was diluted 1:10 in medium for a working concentration of 10 mM; 10 μL of this (i.e., 100 nmol) was added dropwise over the central cornea. Control corneas received the same volume of medium.

Exposed corneas were incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Medium was then removed from the bottom of the culture dish, and either 0.5 mL fresh medium or 0.5 mL of a 200 μM tetracycline derivative (i.e., 100 nmol) in medium was added dropwise over the central cornea. Corneas were allowed to recover for 24 h at 37°C, receiving a total of 3 dropwise applications of medium or medium containing 100 nmol drug. Alternatively, 2 h postexposure, a single application of a hydrogel containing 300 μmol doxycycline was added to the cornea, as previously described,16 and allowed to incubate for 24 h at 37°C. Cultured corneas were then prepared for examination of the BMZ.

Histology

Corneas were embedded in OCT compound (TissueTek), held on ice for 15 min, then frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Before cutting 10-μm sections on a Microm HM505E cryostat, embedded corneas were equilibrated to −20°C for at least 0.5 h. Once sections were on slides, they were stored at −20°C. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of sections was done as follows: submersion for 1 min in Pen-Fix, 8 min in dH2O, 8 min in Mayer's hematoxylin, 16 min in running tap water, 2 s in eosin, 2 times for 2 min in 95% ethanol, 2 times for 2 min in 100% ethanol, and 2 times for 2 min in xylene. Permount was used to attach the coverslip, and slides were dried overnight in the fume hood. Corneas were viewed with a Leica Microscope DMLB Wetzlar GmbH with ProgRes software (Jenoptik).

Immunofluorescence

Slides of OCT frozen corneal sections were fixed in methanol at −20°C for 10 min and washed in PBS for 15 min. Nonspecific binding was blocked with 5% normal goat serum for 1 h. Primary mouse anti-human monoclonal antibody against MMP-9 was applied to the slides at a 1:400 dilution (5 μg/mL). After 1-h incubation, the slides were washed for 30 min in PBS with 0.05% Tween 20. Negative control slides received PBS/Tween instead of primary antibody. The secondary antibody was goat anti-mouse IgG AlexaFluor488, which was applied as a 1:1,000 dilution for a 1-h incubation. After washing with PBS/Tween for 15 min, 0.4 μg/mL DAPI was applied for 5 min to counterstain nuclei. Prolong Gold was used to coverslip the slides. Digital fluorescent images were captured at 10 × and 40 × magnifications on a Leica DMLB Wetzlar GmbH microscope at 494 nm excitation and 517 nm emission wavelengths.

Electron microscopy

Corneas were fixed in Karnovsky's fixative [2.5% glutaraldehyde, 4% formaldehyde, 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4), 8 mM CaCl2] for 24 h, then transferred to 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4), and stored at 4°C. The specimens were dehydrated in an acetone gradient series before embedding in Epon. Ninety-nanometer sections were cut and stained with uranyl acetate, followed by lead citrate. Grids were viewed on a JEOL 1200 EX electron microscope (UMDNJ-Pathology). An AMT XR41 camera and AMT-V600 software (Advanced Microscopy Techniques) were used to capture the digital images.

Tetracycline derivatives

Four tetracycline derivatives were employed in this study. Doxycycline and sancycline were purchased at the highest commercially available purity. The sancycline structure was confirmed by 1H NMR. 9-t-Butylsancycline (also known as t-BS or 9-t-butyl-6-demethyl-6-deoxytetracycline) was synthesized by the published method,18 and it possessed a purity of >95% (1H NMR: t-butyl resonance at 1.40 ppm = 9 H singlet; Ar-H at 6.53 and 7.33 ppm = 2 H doublets, ortho coupled with J = 8, spectrum obtained in CDCl3). Dedimethylamino tetracycline (DDMT) was synthesized by the published method19 with purity (>95%) and structure confirmed by 1H NMR [complete absence of N-methyl resonances at 2.44 ppm in d6 dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)].

For cultured corneas, the following steps were carried out: 10 nmol sancycline (414.42 g/mol), t-BS (470.53 g/mol), and DDMT (371.35 g/mol) were each vigorously vortexed in 100 μL DMSO until dissolved, and once dissolved, the drugs were brought up to 50 mL with medium, yielding a 200 μM solution of drug containing 0.2% DMSO. Doxycycline hyclate (512.94 g/mol) was used because of its greater solubility. It was first made as a 20 mM solution in water and then diluted to 200 μM. Each application of tetracycline derivative delivered 100 nmol, and applications were made 3 times per day. All tetracycline derivatives were put in solution no more than 2 days before use. Hydrogels for corneal cultures were made as described previously.16

For the in vivo animal studies described below, an ophthalmic solution of doxycycline hyclate was prepared by Greenpark Compounding Pharmacy at a concentration of 0.25 mg/mL in Teargen (Major Pharmaceuticals). One drop of solution containing 12.5 μg doxycycline was delivered 3 times per day to the eye, the same as an ophthalmologist might prescribe for an ocular injury. For doxycycline hydrogels, 2 vials were prepared for each animal in the hydrogel groups for every day of the study. One contained polymer [8-arm PEG thiol (20 kDa), 2.5 mg], and the other contained crosslinker [8-arm PEG N-hydroxysuccinimide (20 kDa), 5 mg] plus doxycycline (0.15 mg). When ready to carry out the treatment in the eyelid pocket, 50 μL sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) was added to the polymer vial and 50 μL to the crosslinker–drug vial. Both vials were shaken until the compounds dissolved (∼30 s). Dissolved polymer solution was then pipetted into the dissolved crosslinker/drug solution and shaken. Twenty-five μL of mixed solution was pipetted into the lower eyelid pocket under the center of the eye, where the hydrogel formed within 45 s. For hydrogel controls, the same procedure was used, except that no doxycycline was added to the crosslinker vial.

In vivo SM exposure of rabbit eyes and treatment with doxycycline as drops and hydrogels

SM exposures were performed at Battelle Biomedical Research Center as previously described.20 Sixty-four New Zealand white rabbits were randomized into groups. To the right eye of 12 anesthetized rabbits, 0.4 μL neat SM (5 mg = ∼30 nmol) was directly applied onto the central cornea. Eyelids of the exposed eye were held open for 5 min using an ocular speculum and then manually closed 3 times to spread any residual SM over the cornea. Of these animals, 3 were sacrificed on the following days: 1, 3, 7, 28 days postexposure. A second set of 12 animals was exposed to SM as described, but 4 h after exposure were treated with 1 drop of doxycycline (12.5 μg) applied 3 times per day to the central cornea until sacrifice. As described above, 3 rabbits were sacrificed at 1, 3, 7, and 28 days after exposure. A third set of 12 animals was exposed to SM as above, and then at 4 h postexposure, they received 25 μL of hydrogel plus doxycycline solution (37.5 μg), pipetted into the lower eyelid pocket under the center of the eye. A new hydrogel was applied daily. For this treatment group, 3 rabbits were sacrificed at 1, 3, 7, and 28 days postexposure. Controls included (1) unexposed animals receiving daily doxycycline drops 3 times per day to the central cornea, (2) unexposed animals receiving daily hydrogels without drug, and (3) unexposed animals receiving daily hydrogels containing doxycycline until the day of sacrifice. Naive rabbit corneas were also used for comparisons. Clinical assessments were performed at 7 days before exposure as well as at the time of sacrifice. In addition, animals to be euthanized at study day 28 were also assessed on study day 7, giving data for 6 animal eyes for this time point. Clinical assessments evaluated each eye for corneal thickness and neovascularization. Left eyes were unexposed and were used as internal controls.

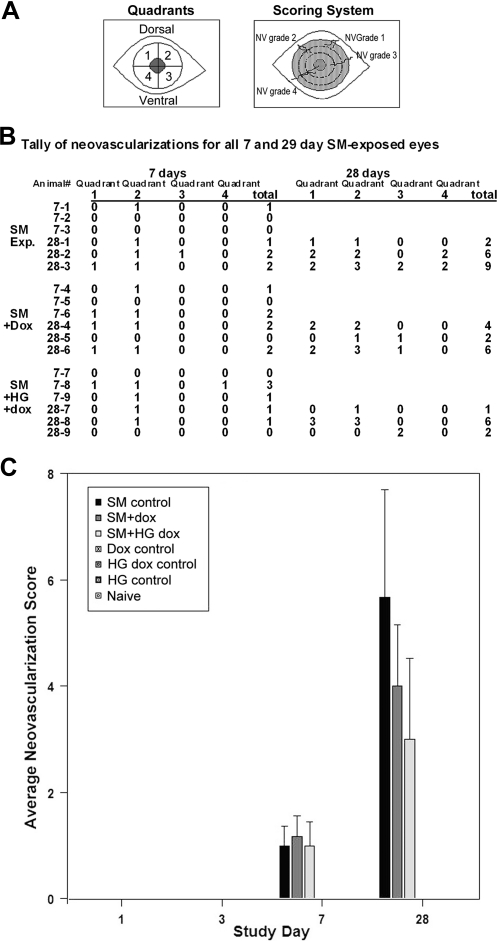

Assessment of corneal thickness and neovascularization

A standard method to calculate the corneal thickness index was used as an objective measure to assess differences between the treatment and control groups. Corneal thickness was measured on right and left eyes with ultrasonic pachymetry (PACSCAN™ 300P; Sonomed, Inc.) in accordance with instrument documentation. Measurements were obtained from 5 areas on each cornea: the center, dorsal, ventral, medial, and lateral aspects. Averaging these 5 values for thickness, the index value for changes in corneal thickness of the SM-exposed eye was calculated by taking the averaged thickness of the exposed eye minus the thickness of it measured preexposure and dividing the difference by the preexposure thickness. Index values were then graphed. To assess the extent of neovascularization, the corneas were analyzed as 4 quadrants. The extent of neovascularization in each of the 4 quadrants was assessed individually and was based on the invasive progression of the vessel(s) within individual quadrants and was attributed to the quadrant of origination, not termination. The individual scores were added together, to yield a single neovascularization assessment score. Scores were assigned as follows: 0 = no new vascularization present; 1 = the longest vessel's length is up to ∼25% of the radius of the cornea; 2 = the longest vessel's length is up to ∼26%–50% of the radius of the cornea; 3 = the longest vessel's length is up to ∼51%–75% of the radius of the cornea; 4 = the longest vessel's length is greater than ∼75% of the radius of the cornea.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was conducted for thickness index and neovasculariztion at each time point, first using all available data at that time point to see how exposures and treatments differed from naive and controls and then again using only the SM-challenged groups to see differences between no doxycycline treatment versus doxycycline treatment. Nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to evaluate total neovascularization scores. One-way analysis of variance models were used to evaluate corneal thickness index. All significant findings were noted at the 0.05 level, with no adjustments for multiple comparisons. The SAS (version 9.1.3) NPAR1WAY, FREQ, and MIXED procedures were used to perform the statistical analysis. P values are presented in the figure legends.

Results

Organ-cultured corneas

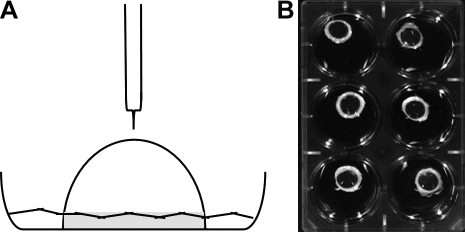

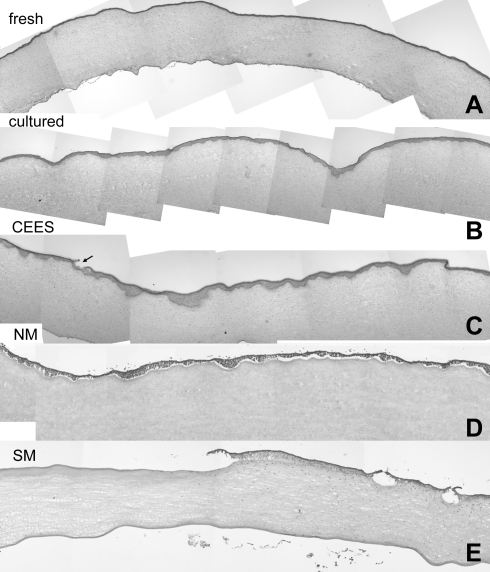

An organ culture model13 was adapted to allow for corneas to be exposed to mustards (Fig. 1A). Cultures were equilibrated overnight before being used in experiments. As a first step in evaluating these overnight cultures, sections of corneas stained with H&E were compared with sections from rabbit corneas prepared immediately after sacrifice. Overlapping low-magnification photographs of individual corneal sections were assembled into a montage to evaluate the entire width of the central corneas (Fig. 2). Two differences were apparent between the fresh cornea (Fig. 2A) and the organ-cultured corneas (Fig. 2B). The first was that in the fresh cornea the epithelial layer was mostly uniform in thickness, whereas that of the cultured corneas appeared to have areas where the epithelium was thicker. Close examination showed the epithelium “dipping” into the stroma. We estimated that ∼25% of the epithelial–stromal border showed this phenotype. The second difference between the fresh and cultured corneas was that culturing resulted in some stromal swelling. On average, this swelling increased the stromal depth by <15%. However, corneal transparency was not impaired (Fig. 1B). Even after 7 days in culture, corneas were completely transparent, indicating that the endothelium was functioning.

FIG. 1.

(A) Diagram of an organ culture with delivery to the central cornea. Gray indicates the scleral rim. (B) Photograph of cultures on a black background. The corneas remain transparent in culture as evidenced by the white scleral rim.

FIG. 2.

Comparison of composites of hematoxylin and eosin–stained corneas plus and minus vesicants. (A) Sections of a cornea freshly dissected from a rabbit eye; (B) a composite of a corneal culture equilibrated at 37°C overnight and then incubated 24 h at 37°C as an unexposed control; (C) sections from a corneal culture exposed to CEES for 2 h and then incubated 24 h before analysis; (D) a composite of a culture exposed to NM for 2 h and then incubated for 24 h; (E) a composite of sections from a rabbit eye at 24 h after exposure to SM in vivo. CEES, 2-chloroethyl ethyl sulfide; NM, nitrogen mustard; SM, sulfur mustard. The arrow in 2C indicates a focal area of epithelial detachment.

CEES and NM exposure altered corneal epithelial thickness and the BMZ

Corneal cultures that had been equilibrated for 24 h were exposed to CEES or NM to induce a range of injury. Agents were applied directly to the central cornea and then allowed to incubate at 37°C for 2 h before washing with medium. After washing, cultures were returned to the incubator, and 24 h after the exposure, the tissue was prepared for histologic examination by light microscopy. As expected, vesicant injury was variable, occurring in foci. For example, 24 h after the 2-h CEES exposure (20 nmol) there was an increase in the number and depth of dips into the stroma (Fig. 2C) that were clearly more extensive than the unexposed control cultured corneas. Foci of epithelial detachment from the stroma (Fig. 2C, arrow) were also present. At low magnification, the NM-exposed (100 nmol) samples (Fig. 2D) also showed an increase in the number and depth of areas displaying downward epithelial dipping into the stroma, but also showed that usually >50% of the epithelium was detached from the stroma. In fact it was not uncommon for ∼85% of the epithelial layer to be detached 24 h after NM exposure.

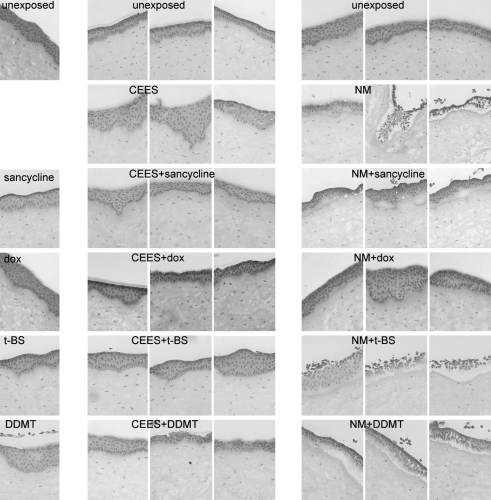

Comparison of the epithelial–stromal junctions of CEES-, NM-, and SM-exposed corneas

As our long-term goal was to use the organ culture system to evaluate drug candidates that would be ultimately tested on animal corneas exposed to SM, we compared the BMZ of cultured corneas with rabbit eyes exposed in vivo to 30 nmol SM. Many SM-exposed corneas had large regions of denuded stroma and several smaller areas where the epithelium had separated from the stroma (Fig. 2E). Higher magnifications are shown of the epithelial–stromal junction in corneas at 24 h after CEES, NM, or SM exposures (Fig. 3). These micrographs clearly show that the vesicants induce injuries of similar phenotype, but with increasing severity going from CEES to NM to SM. All 3 vesicants induced areas where the epithelium dipped into the stroma, areas where microbullae were apparent, and regions where the epithelium separated from the stroma. CEES damage was mildest, showing mostly epithelium depressions (Fig. 3D–F). NM damage was moderate with formation of microbullae and with areas where epithelia dipped into the stroma (Fig. 3G–I). However, there was also severe damage, with extensive epithelial detachment, or areas where the epithelia were tethered by thin cell processes. SM caused the most extensive damage, with many regions of total epithelial detachment, and few areas with microbullae and epithelial depressions into the stroma (Fig. 3J–L).

FIG. 3.

Variability of vesicant exposures. (A–C) High-magnification images of unexposed cultured corneal sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin; (D–F) corneas at 24 h post-CEES exposure; (G–I) corneas at 24 h after NM exposures; (J–L) corneas at 24 h after an in vivo exposure to SM.

The BMZs of corneas exposed to the 3 vesicants were examined using transmission electron microscopy. Unexposed cultured corneas (Fig. 4A and G) and a cornea freshly dissected from an unexposed rabbit eye (Fig. 4M) have well-developed basal lamina with a distinct lamina lucida and lamina densa. The basal epithelial cells have well-developed hemidesmosomes (HD) and anchoring fibrils (asterisks) in the anterior stroma, as well as anchoring filaments spanning the lamina lucida under the HD. A full range of similar BMZ phenotypes were observed 24 h after exposure to each of the vesicants. In all exposed corneas, some regions of the BMZ were largely undamaged (Fig. 4B, H, and N). In other regions, the HD became rounder and more pronounced, expanding into the epithelial cell cytoplasm (Fig. 4C, D, I, J, O, and P). Vesiculation was common (Fig. 4D, I, J, and P). In areas of greater damage, the BMZ was less distinct (Fig. 4E, H, K, N, and Q). In such areas, the beginning of epithelial separations became apparent (Fig. 4F, L, and R). Although the injury at the BMZ is similar with CEES, NM, and SM, the degree of injury varies. The milder phenotypes (Fig. 4B, H, and N) were more common to the BMZ of CEES-exposed corneas. NM-exposed corneas showed more of a moderately severe phenotype (Fig. 4I, J, and K), with many more regions of complete epithelial–stromal separation (Fig. 4F, L, and R). The SM-exposed corneas had the most severe phenotype with many areas of indistinct basement membrane (Fig. 4E, K, and Q), as well as large regions of complete epithelial detachment (Fig. 4F, L, and R).

FIG. 4.

Vesicants altered BMZ structures. TEM of unexposed (A, G, M) and exposed corneal BMZ. (A, G) Unexposed organ cultures; (M) freshly dissected rabbit cornea. The range of BMZ phenotypes at 24 h after CEES exposure (B–F), NM exposure (H–L), and SM exposure (N–R) are from nearly normal to extremely disrupted. BMZ features include LL, lamina lucida; LD, lamina densa; HD, hemidesmosome (A). Asterisks appear just under 2 bundles of anchoring fibrils. BMZ, basement membrane zone.

Evaluation of tetracycline derivatives as therapies for vesicant-induced corneal injuries

Although not a perfect therapy, the MMP inhibitor and antibiotic, doxycycline, improves healing of SM-exposed corneas15 and lungs.21 Therefore, we asked whether other tetracycline derivatives would be equally or more effective as corneal therapies for vesicants. One derivative chosen was sancycline, which is less lipophilic than doxycycline. Two others, t-BS and DDMT, are more lipophilic. As a series of drug controls, each 200 μM tetracycline derivative was applied dropwise 3 times over the course of 24 h onto unexposed corneas to deliver 100 nmol in each application. These are shown in the drug control panels in the left column of Fig. 5. Only 1 agent, DDMT, had a somewhat adverse effect on the cornea (Fig. 5, DDMT), with areas of paleness in the epithelium where the nuclei were undetectable. Other sections of corneas treated with this drug alone showed epithelial cells separating from each other, indicating they were losing cell–cell contacts (not shown). Because sancycline and t-BS were also in medium with 0.2% DMSO, this suggested that the effect was likely due to the DDMT itself and not due to the delivery vehicle. For vesicant-exposed corneas, 3 sections of each tetracycline derivative are shown in Fig. 5. CEES exposures are in the middle set of columns and NM exposures are in the right set of columns. The images demonstrate the variety of observed phenotypes. All treatments generally facilitated improvement in the appearance of the BMZ at 24 h after the mild CEES exposure, although the BMZ of DDMT-treated corneas was occasionally not improved. However, with moderate NM exposure, only doxycycline was effective (Fig. 5, NM + dox). Sancycline kept the epithelium attached to the stroma, but resulted in large areas of basal cell paling, indicating that cells were not completely healthy. Treatments of t-BS and DDMT displayed almost no lessening of epithelial detachment compared with NM-exposed corneas receiving no treatment. Therefore, with the exception of doxycycline, the tetracycline derivatives were not effective therapies for the first 24 h post-NM exposure (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Corneal epithelia are damaged by CEES and NM, and tetracycline derivatives decrease damage. Corneas that were treated for 24 h with tetracycline derivatives after a 2-h vesicant exposure were compared with unexposed and tetracycline derivative-only samples. Top row: sections from unexposed control corneas. Left column: unexposed corneas that received a 24-h treatment with tetracycline derivatives (drug-only controls). Middle column set: CEES exposure, untreated (row 2) or treated for 24 h with tetracycline derivatives (rows 3–6). Right column set: NM exposure, untreated (row 2) or treated for 24 h with tetracycline derivatives (rows 3–6). DDMT, dedimethylamino tetracycline; dox, doxycycline; t-BS, 9-t-butyl sancycline.

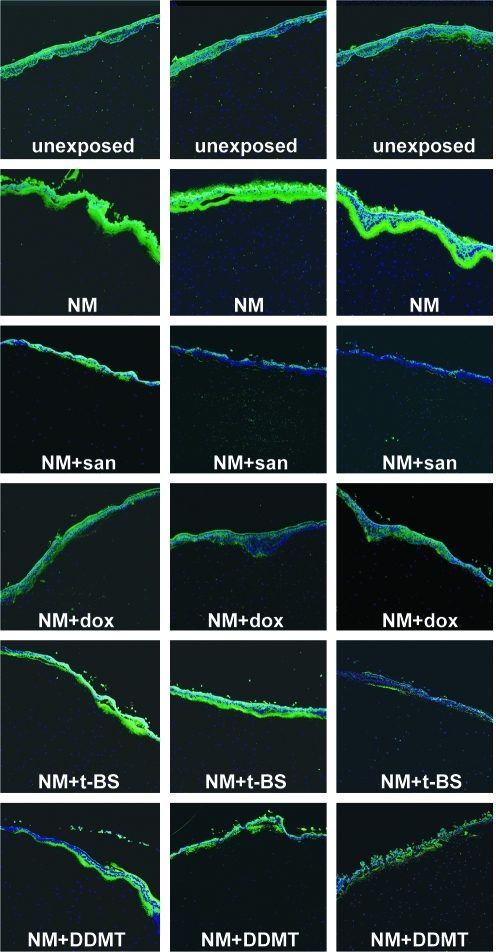

The effectiveness of doxycycline may be due to its ability to inhibit MMPs.21,22 We therefore examined if tetracycline treatments altered the immunofluorescence levels of MMP-9 in corneas exposed to NM (shown in Fig. 6 as 3 panels for each drug). Unexposed control corneas had low levels of MMP-9 immunofluorescent signal (green) just under the epithelium. Note that the apical cells of the epithelium commonly display nonspecific edge effect background autofluorescence. Twenty-four hours after NM exposure, the MMP-9 signal was greatly increased in the BMZ and anterior stroma (Fig. 6, NM). NM-exposed corneas treated for 24 h with the tetracycline derivatives demonstrated that all inhibited MMP-9 expression to some degree (Fig. 6). Sancycline appeared to have the greatest inhibitory effect (Fig. 6, NM + san), followed by doxycycline (Fig. 6, NM + dox). When compared with NM-exposed corneas that received no treatment, t-BS and DDMT were also inhibitory (Fig. 6, NM + t-BS and NM + DDMT), but not to the degree of sancycline and doxycycline. These data suggest that a property other than MMP inhibition may be responsible for the effectiveness of doxycycline in ameliorating the BMZ after NM exposure, as indicated in the H&E-stained sections (Fig. 5).

FIG. 6.

The increase in MMP-9 in the BMZ induced by NM is attenuated by tetracycline derivatives. Three sections illustrating MMP-9 distribution patterns in each treatment group from a typical NM exposure experiment. Top row: unexposed controls had low levels of MMP-9 and background staining in the epithelium; row 2: NM greatly increased MMP-9; rows 3–6: corneas exposed to NM, followed by treatment with a tetracycline derivative for 24 h. Green: MMP-9 antibody staining; blue: DAPI-stained nuclei. MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; san, sancycline.

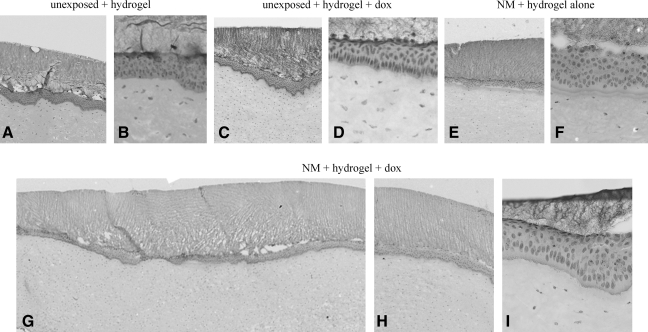

Doxycycline drops and hydrogels ameliorate SM injury of in vivo exposed rabbit corneas

We have previously reported on a hydrogel formulation for the 24-h delivery of doxycycline to organ cultures.16 Further work with the hydrogels in organ culture (Fig. 7A, B) demonstrated that they do not adversely affect the organ cultures. The addition of doxycycline to the hydrogels also does not adversely affect the corneas (Fig. 7C, D). Forming a hydrogel without drug on an NM-exposed cornea improved the 24-h outcome to some extent (Fig. 7E, F). This may simply be because in culture, where blinking is not an issue, the hydrogel assists in holding the epithelium on the basement membrane and stroma. However, despite being attached, the epithelial cells have lost organization and appear unhealthy. Applying doxycycline in the hydrogel to NM-exposed corneas improved the 24-h morphology of the BMZ (Fig. 7G–I) as effectively as administering drops 3 times per day (compare Fig. 6G–I with Fig. 5, NM + dox). Therefore, we moved forward to in vivo SM exposures followed by treatment with doxycycline as drops or a hydrogel. Rabbit eyes were exposed to 0.4 μL neat SM (30 nmol), and 4 h after off-gassing, doxycycline was applied to the eyes using a dose prescribed by ophthalmologists to patients in an off label use: 3 times per day at 12.5 μg per application. Other rabbit eyes exposed to SM were treated with 37.5 μg doxycycline delivered in the 24-h releasing hydrogel. As it was possible that blinking would remove a hydrogel formed on the eye, preventing a 24-h continuous delivery of drug, application to the rabbit eyes was done in a different manner than in the cultures. Effective delivery of pilocarpine to the eye had been accomplished by applying the hydrogel to the eyelid pocket.17 Therefore, as the hydrogel containing doxycycline was in its liquid form, it was added to the middle of the rabbit's lower eyelid pocket for formation in situ within 45 s. Both the dropwise and hydrogel therapies were given every day for 28 days, examining the eyes at 1, 3, 7, and 28 days.

FIG. 7.

Hydrogels designed to release doxycycline over 24 h improved the BMZ of NM-exposed corneal cultures. (A, B) Different magnifications of unexposed corneas, showing normal morphology after hydrogels treatment for 24 h; (C, D) low and high magnifications of corneas treated with hydrogel containing doxycycline; (E, F) low and high magnification of corneas treated with hydrogel for 24 h after a 2-h NM exposure; (G–I) low and high magnifications of corneas exposed to NM, followed by treatment with a hydrogel containing doxycycline, which have an improved BMZ phenotype compared with those that received hydrogel without the drug (E, F).

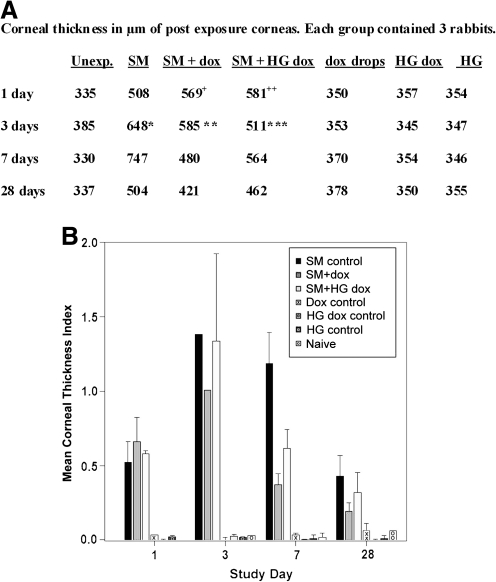

At 24 h postexposure, the ulcerated corneal tissue had not yet begun to heal from the severe SM challenge (Fig. 8). Gross examination of the rabbit eyes clearly demonstrated that corneal edema clouded some eyes by 3 days. However, with dropwise delivery of doxycycline for 7 days, a significant improvement was observed compared with eyes receiving no treatment (Fig. 8), as previously reported.15 The doxycycline hydrogels produced the same improvement in corneal clarity. Edema adversely affects transparency by increasing the corneal thickness, which was assessed by pachymetry. The average thickness of the 3 corneas in each group demonstrated that corneal thickness increased with SM exposure with a maximum thickness at 7 days (Fig. 9A). Treatment with doxycycline as drops or hydrogels decreased corneal thickness toward more normal values (Fig. 9A), with significant differences at 7 days postexposure. The pachymetry data were also used to calculate the mean corneal thickness index (Fig. 9B). This too showed that doxycycline treatment reduced corneal edema by day 3. Between the 2 doxycycline groups, the dropwise application resulted in less edema than the hydrogel application. Analysis indicated that the thickness differences promoted by both application methods were statistically significant for the 7 days postexposure time point.

FIG. 8.

Doxycycline in drops or hydrogels facilitate wound healing of rabbit corneas exposed in vivo to SM. Rows: representative unexposed eyes (row 1) and eyes taken at the indicated time after exposure to SM. Left column: unexposed eye compared with eyes exposed to SM, on days 1, 3, 7, and 28 postexposure. Middle column: unexposed eye and SM-exposed eyes that received 3 dropwise treatments of doxycycline over a 24-h period for every day until sacrifice. Right column: unexposed eye and eyes exposed to SM, followed by daily application of a hydrogel containing doxycycline for the number of days indicated.

FIG. 9.

Doxycycline ameliorated the increase in corneal thickness (measured by pachymetry) induced by SM exposure. Corneal thickness was read at 5 areas in each cornea (left, right, top, bottom, and center). Values were averaged to obtain the mean thickness for each cornea. (A) Preexposure, the average of the 64 corneas was 353.5 ± 19.3 μm (standard deviation). Mean values of exposed eye corneal thickness at indicated times postexposure without taking into account each cornea's preexposure thickness. When damage is severe, pachymetery cannot be read. Therefore, 5 readings were not possible in the 1 and 3 days postexposure samples. The value for the 1 day postexposure thickness for the SM + dox corneas (indicated by “ + ”) was calculated from 4 readings from 1 animal, 3 readings from the second, and 5 readings from the third; the SM + hydrogel containing dox (HG dox) value (indicated by “ + + ”) was averaged from 5 readings from the first animal, 4 from the second, and 4 from the third. The value for the 3 days postexposure thickness for the SM-exposed corneas (indicated by *) was calculated from 1 reading from the first animal, 0 readings from the second, and 4 readings from the third; the value for the thickness of SM + dox corneas (indicated by **) was calculated from 1 reading from the first animal, 4 readings from the second, and 1 readings from the third; the SM + HG dox value (indicated by ***) was averaged from 1 reading from the first animal, 1 from the second, and 2 from the third. (B) Mean corneal thickness index for each group, shown in histogram form, correcting for the initial thickness of corneas before exposure. The equation for this calculation is “right eye postexposure” minus “right eye preexposure” divided by “right eye preexposure” for individual corneas. Next, the mean of the 3 corneas in the group was determined. This removes bias in the postexposure thickness that might be due to individual variations in the thickness of the preexposed corneas. At day 3 the damage was severe, and thickness due to edema could be reliably determined for only 1 cornea in the SM group and 1 cornea in the SM + dox group, and thus these histograms have no error bars. The 3 days SM + HG dox group had edema measurable in 2 corneas; therefore, an error bar is shown. The P values from statistical analysis (analysis of variance) of all groups were 0.0049 for 1 day, 0.1029 for 3 days, <0.0001 for 7 days, and 0.1053 for 28 days. The 3-day value includes all corneas in the group, that is, those that were of larger than preexposure thickness from edema, and those thinner from other SM damage. With a Tukey analysis, there was a significant difference between SM-challenged groups at 7 days: the corneal thickness index in the SM group was significantly greater than that for the SM + dox group (difference = 0.81, P value = 0.0015) and the SM + HG dox group (difference = 0.57, P value = 0.0156). A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Doxycycline reduced but did not prevent neovascularization, as previously observed.15 However, the hydrogel delivery of doxycycline showed less neovascularization than the dropwise delivery (Fig. 10). Corneas with doxycycline in drops had ∼30% less-severe neovascularization than corneas exposed to SM without subsequent treatment (Fig. 10C). Doxycycline in the hydrogel formulation reduced the neovascular severity by ∼48% (Fig. 10C). Analysis of neovascularization showed that days 7 and 28 were statistically significant.

FIG. 10.

Neovascularization (NV) of corneas after SM with and without doxycycline. Neovascularizations were not seen in unexposed controls or in any SM-exposed corneas at days 1 and 3, but were present at days 7 and 28. (A) Quadrants and scoring criteria diagram. For scoring, 0 indicates no new vascularization present; 1 indicates the longest vessel's length is up to ∼25% of the radius of the cornea; 2, the longest vessel's length is up to ∼26%–50% of the radius of the cornea; 3, the longest vessel's length is up to ∼51%–75% of the radius of the cornea; and 4, the longest vessel's length is greater than ∼75% of the radius of the cornea. (B) Tally of days 7 and 28 neovascularizations for each SM-exposed eye. Note that there were 6 rabbits assessed at 7 days, 3 that were to be sacrificed at 7 days, and 3 that were to be sacrificed at 28 days. (C) Histogram depiction of the increase in neovascularization with time, showing that SM-exposed animals had the greatest extent of angiogenesis (black bars). Applying doxycycline drops 3 times/day for 28 days (dark gray bars) attenuated neovascularization by ∼30%, and applying hydrogels with doxycycline (light gray bars) daily for 28 days attenuated it by ∼48%. Statistics: Kruskal–Wallis analysis was performed on total neovascularization grade scores for each day. P values for preexposure corneas, as well as 1 and 3 days postexposure corneas were 1.0000 because of all values being the same for all animals at these time points. The 7 days P value was 0.0328 and for 28 days it was 0.0465. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Discussion

The eye is the most sensitive organ to SM,24,25 being irritated by an exposure 10 times less than that which would irritate the respiratory tract (for review, see Smith and Dunn1). The vesicant causes blistering of skin, whereas microseparations at the BMZ between the epithelium and stroma are observed in the cornea. SM exposure causes a range of injuries to the eye, from mild conjunctivitis to advanced corneal disease. The SM injuries from the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s recorded severe ocular damage in about 10% of those exposed,6,23,26 and this has emphasized the need for potential therapies. To date, there is no FDA-approved therapy. Further, the ease with which SM can be synthesized suggests that it should be taken very seriously as a potential terrorist agent.

To identify therapies against SM is no minor task. This vesicant cannot be used except in designated restricted facilities in the United States. Using these facilities makes it difficult to do extensive drug screening because animal studies using the vesicant are costly. Because air–liquid interface corneal organ cultures have been used for a variety of experimental purposes,13,16,17,27–31 we adapted an organ culture model system and tested whether it could serve as a preliminary screening method for potential SM therapies. SM exposures cause variable injury according to the exposure time, concentration of the vesicant, and the exposed individual's susceptibility.32–34 By exposing the rabbit corneal organ cultures to CEES and NM, we were able to induce a range of 24-h postexposure injuries at the BMZ that resembled those occurring 24 h after in vivo exposure of rabbit eyes to SM. Both light and electron microscopic analyses highlighted the similarity of the injury at the BMZ with the 3 vesicants and suggested the organ cultures would serve our purpose. The rabbit corneal organ culture system allowed us to inexpensively test 4 tetracycline derivatives on several corneas for their ability to preserve the BMZ at 24 h after exposure. The most promising candidate was then transitioned to the New Zealand White rabbit eye model.

The decision of what drugs to test were based on data showing MMP activity at the BMZ after injury. Recurrent corneal erosions, where the corneal epithelium is loosely adherent and is able to separate from the stroma, express enhanced levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9.35 Tetracyclines have anti-MMP activity,36–38 and the antibiotic tetracycline derivative, doxycycline, was found to improve the outcome of recurrent corneal erosions.39 Doxycycline also improved the outcome of SM-exposed eyes.15 Therefore, we tested 4 tetracyclines as therapies against vesicants. Three tetracycline derivatives with antibiotic activity and one deaminated tetracycline, DDMT, which does not possess antibiotic activity, but does retain antimetalloproteinase activity,36,40 were employed. The same number of nanomoles of each drug was used in experiments because the goal of this pilot project was to identify the best drug in the group quickly and inexpensively. Our results showed that all of the tetracycline derivatives inhibited the NM-induced expression of corneal epithelial MMP-9. The surprise, however, was that only doxycycline was truly effective at the selected concentration for preserving the BMZ at 24 h after NM exposure. Therefore, doxycycline may not be effective against SM exposure because of its anti-MMP activity, but because of some other, as yet unidentified, activity.

Ocular exposure to SM is very painful and can persist from days to months. We reasoned that patients might not be compliant with delivering a drug dropwise to injured eyes 3–4 times per day. Because of this, we used vesicant-exposed organ cultures to test whether a hydrogel releasing doxycycline over a 24-h period worked as well at preserving the BMZ as dropwise application of the drug and we found that this was the case. Proceeding on to animal testing, hydrogel delivery of doxycycline was compared with dropwise delivery of the drug on rabbit eyes exposed to SM in vivo. Because of the severity of SM compared with CEES and NM, treatment was extended beyond 1 day. Based on the fact that a month is not an unreasonable healing time for a human ocular SM exposure, our experiment ran for 28 days. Our data demonstrated that the hydrogel was effective. Corneal thickness did not decrease as much with the hydrogel as it did with the drops, but by 7 days, animals in both treatment groups had transparent corneas, whereas the untreated SM-exposed corneas were still cloudy.

In SM-exposed humans, the delayed effects (1–2 weeks after exposure) often include neovascularization.41 Our experiments showed this also, detecting neovascularization at 7 and 28 days time points. Interestingly, the hydrogel formulation appeared to reduce the amount of neovascularization, although this must be studied further considering the small number of animals tested. However, the trend is apparent. Also, with our small sample size, it cannot be verified conclusively which delivery method for doxycycline permits a better recovery. Although our results suggest that corneas treated with doxycycline in hydrogels may correct edema more slowly than those treated with doxycycline drops, the reduction of neovascularization may make the hydrogel delivery more desirable. The corneal epithelium has a higher nerve density than skin and lung. A definite advantage of the hydrogel is that the patient needs to apply the treatment to a painful injury only once per day and to the eyelid pocket. Avoiding multiple daily applications should help with patient compliance. These issues need to be addressed in a large-scale study.

Hydrogels have been used in various biomaterial and biotechnology applications such as drug delivery.17,42–44 Our work employing doxycycline in a hydrogel is an attempt to identify a drug and a delivery method that might have a beneficial impact on the chronic effect of conjunctivalization of the cornea after ocular SM exposure. Blindness from conjuctivalization is attributed to limbal stem cell deficiency. When a large region of the corneal epithelium is lost, as in SM exposure, limbal epithelial stem cells must be used to replace it. We hypothesize that by preventing the loss of the entire corneal epithelium in the first 24 h after SM exposure with a drug such as doxycycline, the corneal epithelium has an opportunity to recover in situ and allows any remaining healthy basal epithelial cells to proliferate and repair the injury. If this is true, doxycycline treatment could prevent the depletion of the limbal stem cells. Ophthalmologists routinely prescribe doxycycline for ocular injuries, although it is not FDA approved for such use. We conclude that doxycycline as drops and hydrogels should be pursued as potential countermeasures against SM exposure. However, hydrogels may prove to be a better therapy because of the lower level of neovascularization. This may be due to the more continuous release of doxycycline over each 24-h period. A combination therapy with doxycycline and an antiangiogenic in a hydrogel also warrants investigation as a potential therapy.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the CounterACT Program, National Institutes of Health (NIAMSD U54AR055073), the National Eye Institute award EY09056, and the NIEHS-sponsored UMDNJ Center for Environmental Exposures and Disease (NIEHS P30ES005022). The authors thank Ken Hughes, RPh of Greenpark Compounding Pharmacy, for helpful suggestions, and Linda Everett for help with the manuscript.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Smith W.J. Dunn M.A. Medical defense against blistering chemical warfare agents. Arch. Dermatol. 1991;127:1207–1213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papirmeister B. Feister A. Robinson S., et al. Medical Defense Against Mustard Gas: Toxic Mechanisms and Pharmacological Implications. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wattana M. Bey T. Mustard gas or sulfur mustard: an old chemical agent as a new terrorist threat. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2009;24:19–29. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x0000649x. discussion 30–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balali-Mood M. Hefazi M. The pharmacology, toxicology, and medical treatment of sulphur mustard poisoning. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2005;19:297–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2005.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balali-Mood M. Hefazi M. Comparison of early and late toxic effects of sulfur mustard in Iranian veterans. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2006;99:273–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2006.pto_429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Etezad-Razavi M. Mahmoudi M. Hefazi M. Balali-Mood M. Delayed ocular complications of mustard gas poisoning and the relationship with respiratory and cutaneous complications. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2006;34:342–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghasemi H. Ghazanfari T. Babaei M., et al. Long-term ocular complications of sulfur mustard in the civilian victims of Sardasht, Iran. Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol. 2008;27:317–326. doi: 10.1080/15569520802404382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Javadi M.A. Baradaran-Rafii A. Living-related conjunctival-limbal allograft for chronic or delayed-onset mustard gas keratopathy. Cornea. 2009;28:51–57. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181852673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Javadi M.A. Yazdani S. Kanavi M.R., et al. Long-term outcomes of penetrating keratoplasty in chronic and delayed mustard gas keratitis. Cornea. 2007;26:1074–1078. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181334752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Javadi M.A. Yazdani S. Sajjadi H., et al. Chronic and delayed-onset mustard gas keratitis: report of 48 patients and review of literature. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:617–625. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Namazi S. Niknahad H. Razmkhah H. Long-term complications of sulphur mustard poisoning in intoxicated Iranian veterans. J. Med. Toxicol. 2009;5:191–195. doi: 10.1007/BF03178265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shohrati M. Peyman M. Peyman A. Davoudi M. Ghanei M. Cutaneous and ocular late complications of sulfur mustard in Iranian veterans. Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol. 2007;26:73–81. doi: 10.1080/15569520701212399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foreman D.M. Pancholi S. Jarvis-Evans J. McLeod D. Boulton M.E. A simple organ culture model for assessing the effects of growth factors on corneal re-epithelialization. Exp. Eye Res. 1996;62:555–564. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carrington L.M. Albon J. Anderson I. Kamma C. Boulton M. Differential regulation of key stages in early corneal wound healing by TGF-beta isoforms and their inhibitors. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis Sci. 2006;47:1886–1894. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kadar T. Dachir S. Cohen L., et al. Ocular injuries following sulfur mustard exposure—pathological mechanism and potential therapy. Toxicology. 2009;263:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anumolu S.S.N. DeSantis A.S. Menjoge A.R., et al. Doxycycline loaded poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels for healing vesicant-induced ocular wounds. Biomaterials. 2010;31:964–974. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anumolu S.S.N. Singh Y. Gao D. Stein S. Sinko P.J. Design and evaluation of novel fast forming pilocarpine-loaded ocular hydrogels for sustained pharmacological response. J Control Release. 2009;137:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernardi L. Colonna V. De Castiglione R. Masi P. Tetracycline Derivatives. Mar 18, 1974. Belgian Patent No. 804,913, issued.

- 19.Angusti A. Hou S.T. Jiang X.S. Komatsu H. Kubo T. Lertvorachon J. Roman G. Tetracyclines and their use as calpain inhibitors. Feb 25, 2005. WO/2005/082860, Internatioal Appl. No. PCT/CA2005/000279, filed.

- 20.Babin M.C. Ricketts K.M. Gazaway M.Y., et al. A combination drug treatment against ocular sulfur mustard injury. J. Toxicol. Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol. 2004;23:65–75. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guignabert C. Taysse L. Calvet J.H., et al. Effect of doxycycline on sulfur mustard-induced respiratory lesions in guinea pigs. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2005;289:L67–L74. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00475.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Petrinec D. Liao S. Holmes D.R., et al. Doxycycline inhibition of aneurysmal degeneration in an elastase-induced rat model of abdominal aortic aneurysm: preservation of aortic elastin associated with suppressed production of 92 kD gelatinase. J. Vasc. Surg. 1996;23:336–346. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(96)70279-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghassemi-Broumand M. Agin K. Kangari H. The delayed ocular and pulmonary complications of mustard gas. J. Toxicol. Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol. 2004;23:293–302. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papirmeister B. Gross C.L. Meier H.L. Petrali J.P. Johnson J.B. Molecular basis for mustard-induced vesication. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 1985;5:S134–S149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kadar T. Turetz J. Fishbine E., et al. Characterization of acute and delayed ocular lesions induced by sulfur mustard in rabbits. Curr. Eye Res. 2001;22:42–53. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.22.1.42.6975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Safarinejad M.R. Moosavi S.A. Montazeri B. Ocular injuries caused by mustard gas: diagnosis, treatment, and medical defense. Mil. Med. 2001;166:67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kabosova A. Kramerov A.A. Aoki A.M., et al. Human diabetic corneas preserve wound healing, basement membrane, integrin and MMP-10 differences from normal corneas in organ culture. Exp. Eye Res. 2003;77:211–217. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(03)00111-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piehl M. Gilotti A. Donovan A. DeGeorge G. Cerven D. Novel cultured porcine corneal irritancy assay with reversibility endpoint. Toxicol. In Vitro. 2010;24:231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2009.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richard N.R. Anderson J.A. Weiss J.L. Binder P.S. Air/liquid corneal organ culture: a light microscopic study. Curr. Eye Res. 1991;10:739–749. doi: 10.3109/02713689109013868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saghizadeh M. Kramerov A.A. Yu F.S. Castro M.G. Ljubimov A.V. Normalization of wound healing and diabetic markers in organ cultured human diabetic corneas by adenoviral delivery of c-Met gene. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010;51:1970–1980. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao B. Cooper L.J. Brahma A., et al. Development of a three-dimensional organ culture model for corneal wound healing and corneal transplantation. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006;47:2840–2846. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Derby G.S. Ocular manifestations following exposure to various types of poisonous gases. Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 1919;17:90–105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Derby G.S. Medical-social service and follow-up work in the eye hospital. Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 1920;18:41–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ireland M. Medical Aspects of Gas Warfare, the Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1926. pp. 1–769. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garrana R.M. Zieske J.D. Assouline M. Gipson I.K. Matrix metalloproteinases in epithelia from human recurrent corneal erosion. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1999;40:1266–1270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Curci J.A. Petrinec D. Liao S. Golub L.M. Thompson R.W. Pharmacologic suppression of experimental abdominal aortic aneurysms: a comparison of doxycycline and four chemically modified tetracyclines. J. Vasc. Surg. 1998;28:1082–1093. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(98)70035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Golub L.M. Lee H.M. Lehrer G., et al. Minocycline reduces gingival collagenolytic activity during diabetes. Preliminary observations and a proposed new mechanism of action. J. Periodontal Res. 1983;18:516–526. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1983.tb00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Golub L.M. McNamara T.F. D'Angelo G. Greenwald R.A. Ramamurthy N.S. A non-antibacterial chemically-modified tetracycline inhibits mammalian collagenase activity. J. Dent. Res. 1987;66:1310–1314. doi: 10.1177/00220345870660080401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dursun D. Kim M.C. Solomon A. Pflugfelder S.C. Treatment of recalcitrant recurrent corneal erosions with inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinase-9, doxycycline and corticosteroids. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2001;132:8–13. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)00913-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Y. Ryan M.E. Lee H.M., et al. A chemically modified tetracycline (CMT-3) is a new antifungal agent. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002;46:1447–1454. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.5.1447-1454.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amir A. Turetz J. Chapman S., et al. Beneficial effects of topical anti-inflammatory drugs against sulfur mustard-induced ocular lesions in rabbits. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2000;20(Suppl 1):S109–S114. doi: 10.1002/1099-1263(200012)20:1+<::aid-jat669>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deshmukh M. Singh Y. Gunaseelan S. Gao D. Stein S. Sinko P.J. Biodegradable poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels based on a self-elimination degradation mechanism. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6675–6684. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lalloo A. Chao P. Hu P. Stein S. Sinko P.J. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluation of a novel in situ forming poly(ethylene glycol)-based hydrogel for the controlled delivery of the camptothecins. J Control Release. 2006;112:333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qiu B. Stefanos S. Ma J. Lalloo A. Perry B.A. Leibowitz M.J. Sinko P.J. Stein S. A hydrogel prepared by in situ cross-linking of a thiol-containing poly(ethylene glycol)-based copolymer: a new biomaterial for protein drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2003;24:11–18. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00227-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]