Abstract

Modulation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK-1/2), a signaling pathway directly associated with cell proliferation, survival, and homeostasis, has been implicated in several pathologies, including alcoholic liver disease. However, the underlying mechanism of ethanol-induced ERK-1/2 modulation remains unknown. This investigation explored the effects of ethanol-associated oxidative stress on constitutive hepatic ERK-1/2 activity and assessed the contribution of the lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) to the observations made in vivo. Constitutive ERK-1/2 phosphorylation was suppressed in hepatocytes isolated from rats chronically consuming ethanol for 45 days. This observation was associated with an increase in 4-HNE-ERK monomer adduct concentration and a hepatic cellular and lobular redistribution of ERK-1/2 that correlated with 4-HNE-protein adduct accumulation. Chronic ethanol consumption was also associated with a decrease in hepatocyte nuclear ELK-1 phosphorylation, independent of changes in total nuclear ELK-1 protein. Primary hepatocytes treated with concentrations of 4-HNE consistent with those occurring during oxidative stress displayed a concentration-dependent decrease in constitutive ERK-1/2 phosphorylation, activity, and nuclear localization that negatively correlated with 4-HNE-ERK-1/2 monomer adduct accumulation. These data paralleled the decreased phosphorylation of the downstream kinase ELK-1. Molar ratios of purified ERK-2 to 4-HNE consistent with pathologic ratios found in vivo resulted in protein monomer-adduct formation across a range of concentrations. Collectively, these data demonstrate a novel association between ethanol-induced lipid peroxidation and the inhibition of constitutive ERK-1/2, and suggest an inhibitory mechanism mediated by the lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal.

Oxidative stress and the subsequent formation of reactive oxygen species have been correlated with a number of disease states in animal models and humans. It is well documented that chronic ethanol consumption results in hepatic oxidative stress (1, 2) causing the peroxidation of membrane lipids and the production of highly reactive α,β-unsaturated aldehydes (1, 3). Recent evidence suggests that the major lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE)2 is associated with several hepatic disease states, including alcoholic liver disease (ALD), hepatitis C, hepatic iron overload, and primary biliary cirrhosis (4).

The production of reactive oxygen species during cellular oxidative stress is thought to be the key event initiating the autocatalytic degradation of polyunsaturated fatty acids to yield electrophilic aldehyde species (1). These highly reactive lipid aldehydes are capable of diffusing from their point of origin to impose diverse effects on more distant cellular nucleophiles through covalent interactions (5). 4-HNE has been shown to affect a wide range of biological activities through its ability to react with nucleophiles on proteins and nucleic acids. In fact, the adduction of proteins by 4-HNE has been demonstrated in vitro using purified proteins (6), in cell culture (3), and in animal models of chronic ethanol and/or iron overload (7-9). Additionally, the presence of 4-HNE-protein adducts has been documented in patients with alcoholic liver disease, hepatitis C, primary biliary cirrhosis, and other chronic liver diseases (10, 11). These data support the presence of 4-HNE-protein adducts as reliable biomarkers of hepatic lipid peroxidation (12-14) and suggest a direct correlation between lipid peroxidation and several pathologic states associated with oxidative stress.

The diverse cellular effects of lipid aldehydes result from their diffusible nature and rapid reactivity. 4-HNE has been shown to preferentially modify cysteine (Cys), histidine (His), and lysine (Lys) residues via Michael addition and for Lys, Schiff base products (1, 15, 16). At high concentrations, 4-HNE is cytotoxic to several cell types (17), whereas micromolar and submicromolar concentrations of 4-HNE have been shown to induce various nontoxic, cell-specific effects. In this regard, 4-HNE is capable of the following: 1) stimulating proliferation and growth in some cell types (18-20) and apoptosis in others (21-23); 2) positively and negatively regulating cytokines (24, 25), kinases (26, 27), and transcription factors (28-30); 3) activating stress signaling pathways (31) and translational activities (32); and 4) inhibiting intracellular proteolysis and enzyme activities (6, 33). Although it has been routinely demonstrated that chronic ethanol consumption results in the hepatic accumulation of 4-HNE-modified proteins (3, 34-36), even in the early phases of ALD (9), the specific protein targets of aldehyde modification and the resulting changes in normal liver function remain largely unknown.

Although limited, in vivo and in vitro evidence suggest that ethanol-induced 4-HNE modification of hepatocellular proteins results in the inhibition of normal enzyme function (34-36). Additionally, it has been shown recently, using an animal model of chronic ethanol consumption, that hepatic extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 (ERK-1/2) activity is suppressed under similar chronic conditions (37, 38). These studies led to the hypothesis that ethanol-induced lipid peroxidation results in the inhibition of constitutive, hepatic ERK-1/2 activity via covalent adduct formation with 4-HNE. This hypothesis is consistent with recent in vivo and primary cell culture data that demonstrate a correlation between ethanol exposure and the inhibition of ERK-1/2 in neurological and vascular pathologies (39-41). This evidence suggests that ethanol-induced oxidative stress and the resulting lipid peroxidation products are predominantly inhibitory in nature. Consistent with this proposition, a series of combined in vivo/in vitro studies have demonstrated the adduction and inhibition of hepatic enzymes that are crucial for normal cell function and homeostasis, namely the cellular repair proteins heat shock protein-72 (Hsp-72), Hsp-90, and protein-disulfide isomerase (34-36). The anonymity of the vast number of 4-HNE-modified proteins demonstrated in the livers of ethanol-treated rats by Carbone et al. (34-36), using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, suggests that the attenuating nature of 4-HNE on the constitutive function of other liver enzymes associated with normal hepatic function and homeostasis requires further investigation.

The extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 are members of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family whose activation results in cell growth, proliferation, and survival (42-44). Because ERK-1 and ERK-2 are highly homologous (>83%) and are thought to carry out similar kinase functions within the cell, they are collectively referred to as ERK-1/2 (44). It is well documented that chronic ethanol consumption inhibits hepatic regeneration following partial hepatectomy or chemical-induced liver injury (45, 46), implicating the dysregulation of the hepatic proliferative ERK-1/2 signaling pathway in ethanol-related liver disease. It has been shown recently that 4-HNE-protein adduct accumulation is an early event in the progression of ethanol-induced liver injury (9). In this context, the research presented here set out to characterize the effects of chronic ethanol exposure and ethanol-induced lipid peroxidation on constitutive ERK-1/2 using a rat model of early ALD.

The results of this study demonstrate that in vivo ethanol-induced lipid peroxidation increased hepatic 4-HNE-ERK-1/2 monomer adduct formation and decreased constitutive ERK-1/2 phosphorylation and nuclear localization. These data correlated with the cytosolic accumulation and hepatolobular redistribution of ERK-1/2 that paralleled the cytosolic and lobular accumulation of 4-HNE-protein adducts. These observations are correlated with an ethanol-induced decrease in nuclear ELK-1 phosphorylation that was independent of changes in total ELK-1 in the nucleus. Furthermore, in experiments using primary hepatocyte cultures, 4-HNE was shown to be a potent inhibitor of constitutive ERK-1/2 phosphorylation, activity, and nuclear localization. These results establish a strong correlation between ethanol-induced lipid peroxidation and the dysregulation of hepatocellular ERK-1/2, and suggest a novel inhibitory mechanism of 4-HNE via adduction of inactive ERK-1/2 monomers that results in the loss of a crucial hepatocellular pathway required for homeostasis, proliferation, and survival.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sequence Analysis

The amino acid sequences for extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 (or Xenopus equivalent, myelin basic protein kinase) from Mus musculus, Rattus norvegicus, Xenopus laevis, and Homo sapiens were obtained from NCBI (P63085, P63086, P26696, and P28482, respectively). These sequences were manually aligned according to the human sequence to determine the extent of homology and conservation of potential 4-HNE-reactive sites across experimental species, when compared with the human ERK-2 sequence.

Animal Model

Twenty male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing ~250 g were obtained from Harlan Inc. (Indianapolis, IN). Ten ethanol-treated rats were fed a nutritionally fortified liquid diet (Dyets, Inc., Bethlehem, PA) containing 16% protein-derived calories, 45% fat-derived calories, 4% carbohydrate-derived calories, and 35% ethanol-derived calories. Ten pair-fed control rats were administered a similar diet containing carbohydrate-derived calories (39%) isocaloric to the amount of ethanol consumed by the alcohol-treated rats (34, 47). The animals received ethanol or control diets for 45 days, at which time they were subdivided into two groups of five control and five ethanol-treated rats, and subjected to the following procedures. 1) Group 1 animals were anesthetized, and their livers removed, weighed, and fixed in paraffin for immunohistochemical and pathological analysis. 2) Group 2 animals were anesthetized, and their hepatocytes were isolated, using established procedures described elsewhere (3, 48), and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with protease inhibitors (4 μl/ml; Sigma) for total cell protein analysis. Prior to euthanization, venous blood was collected from all animals for serum alanine aminotransferase and ammonia analysis.

Biochemical Assays

Hepatotoxicity resulting from chronic ethanol treatment was determined using appropriate biochemical assay kits measuring serum alanine aminotransferase activity and ammonia concentrations as per the manufacturer’s protocol (Sigma).

Histopathology, Immunostaining, and Imaging

Liver samples were routinely processed, and paraffin-embedded sections of the livers were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E). Immunostaining was carried out as described elsewhere (49). Primary antibodies specific for 4-HNE-adducted protein epitopes (3), total and phosphorylated ERK-1/2, total and phosphorylated ELK-1 (Cell-Signaling Technologies, Beverly, MA), and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were incubated with liver sections at 4 °C overnight at 1:5000-, 1:1000-, 1:1000-, 1:50-, 1:50-, and 1:2500-fold dilutions, respectively. Immunopositive reactions were detected indirectly with a secondary biotinylated goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:200). Visualization of primary and secondary antibody interactions was accomplished by using an avidin/biotinylated horseradish peroxidase kit (Pierce) incorporating 3′,3′-diaminobenzidine as the chromogen. The absence of positive staining using this procedure in the absence of primary antibody established the lack of nonspecific staining because of the secondary antibody. Image-Pro Plus image acquisition and analysis software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD) integrating a Nikon Eclipse TE300 microscope equipped with a digital camera was used to capture and analyze representative images of the stained serial sections at ×10, ×40, and ×80 magnifications for each animal treatment group.

Primary Cell Culture and Treatment

Primary rat hepatocytes were isolated from naive, lab chow-fed male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Inc.) using identical procedures as described above and elsewhere (48). The isolated hepatocytes were resuspended in RPMI 1640 containing penicillin/streptomycin (100 IU/ml and 100 μg/ml, respectively), and the cells were plated onto extracellular matrix-coated (Sigma) 100-mm tissue culture plates (BD Biosciences) at a concentration of 3.5 million cells/plate. Adherent hepatocytes were allowed to acclimate to culture conditions at 37 °C, 5% CO2 overnight before treatment with aldehyde. 4-HNE was synthesized immediately prior to cell treatment as described previously (50). At the start of treatment, media from acclimatized, primary hepatocytes were removed and replaced with serum-free RPMI 1640 containing 0, 0.01, 0.1, 1.0, 10, and 100 μm 4-HNE for 4 h under normal cell culture conditions, a time point previously shown to be effective in similar experiments (51). At the end of each treatment, the primary hepatocytes were liberated from the extracellular matrix-coated plates with ice-cold PBS, 1 mm EDTA solution, and the cells were resuspended in PBS with protease inhibitor mixture (PBS/PI).

LDH Cytotoxicity Assay

The cytotoxicity of 4-HNE was determined using the in vitro cytotoxicity assay (Tox-7; Sigma) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cytotoxicity is indirectly quantified as the ratio of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity in the media (released) over the total cellular LDH activity. Media and an aliquot of cells were collected at the appropriate time points for each cell treatment group and used immediately to determine LDH activity. Naive media and PBS/PI served as negative controls. LDH conversion of NAD to NADH was indirectly measured using a Spectra Max 190 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) plate reader, and the data were collected using SOFTmax PRO 4.0. “Relative cytotoxicity” is reported as the ratio of absorbance corresponding to released LDH activity over the total cellular LDH activity when compared with untreated cells.

Cell Harvest and Protein Isolations

Total cell extracts were prepared by sonicating the hepatocyte suspensions four times for 5 s on ice using a Sonic Dismembrator (Fisher). Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation, and the total cell extract protein was quantified using a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce). Samples were diluted to 1 mg/ml and either used immediately for kinase activity assays or mixed with 6× SDS-PAGE loading buffer, heated to 100 °C for 5 min, and separated by SDS-PAGE for immunoblot analysis. Alternatively, nuclear protein fractions were isolated from cell treatment groups using a nuclear isolation kit (Active Motif, Inc.) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. The nuclear protein fractions were quantified and diluted in PBS/PI to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblot Analysis

Samples of total cell extracts (250 μg) were diluted in immunoprecipitation buffer (IP buffer: 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Igepal CA630) to a concentration of 1 mg/ml. Monoclonal antibodies against ERK-1/2 were added to this mixture at a dilution of 1:100 (Cell Signaling), and the samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C with gentle agitation. At the end of incubation, 50 μl of protein A/G-Sepharose bead suspension (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was added to each sample and gently mixed for 1 h at 4 °C. Samples were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 30 s; the supernatant was aspirated, and the beads were washed three times in 1 ml of IP buffer. The isolated beads were resuspended in 1× SDS-PAGE loading buffer, heated to 100 °C for 5 min, vortexed, and flash-centrifuged, and the supernatants were loaded onto a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel for electrophoretic separation.

For immunoblot analysis, immunoprecipitated protein, 15 μg of total cell extract, 7 μg of nuclear protein, or 250 ng of recombinant protein was denatured at 100 °C for 5 min in 1× SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Samples were separated on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel for 2 h (Bio-Rad) and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes as described previously (52). Membranes were blocked in 5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin in Tris-buffered saline with 0.2% Tween (TBS-T) at room temperature for 45 min. The primary antibodies used were as follows: rabbit anti-4-HNE-protein adducts (3); antibodies against total and phospho-specific ERK-1/2, total and phospho-specific ELK-1, and β-actin (Cell Signaling); and rabbit anti-GST-Ya (Oxford Biomedical Research, Oxford, MI). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Cell Signaling. ECL-Plus (Amersham Biosciences) enhanced chemiluminescence reagent was used to visualize antibody-reactive protein bands via film and a STORM 860 (GE Healthcare) and quantified using ImageQuant software (Amersham Biosciences). Because ethanol and 4-HNE influenced both ERK-1 and ERK-2 to nearly identical degrees, densitometry analyses for immunoblots were conducted on the combined ERK-1/2 bands.

ERK-1/2 Activity Assay

To determine the effects of chronic ethanol ingestion and 4-HNE exposure on ERK-1/2 activity toward its substrate Ets-like protein 1 (ELK-1), a nonradioactive kinase assay was used as described elsewhere (53). Monoclonal antibodies raised against phospho-ERK-1/2 conjugated to agarose beads were used to immunoprecipitate (IP) ERK-1/2 from 250 μg of total hepatocyte extracts from control and ethanol-treated animals or aldehyde-treated primary cultures. The immunopurified proteins were incubated with an ELK-1 fusion protein (2 μg/reaction) in the presence of 200 μm ATP for 30 min at 37 °C. Alternatively, ERK-1/2 immunopurified from control hepatocytes was incubated with increasing concentrations of 4-HNE, repurified to eliminate excess 4-HNE, and subjected to the kinase activity assay. The reaction was stopped by addition of 6× SDS-PAGE loading buffer, incubated at 100 °C for 5 min, vortexed, and centrifuged at room temperature. Immunoblot against phospho-ELK-1 was used to determine the ability of immunoprecipitated ERK to phosphorylate ELK-1 fusion protein. 4-HNE-ERK-1/2 adducts were determined using identical blots probed with antibodies raised against 4-HNE-protein adducts.

In Vitro Modification of ERK-2 by 4-HNE

Molar ratios of ERK/4-HNE were calculated to mimic in vivo conditions of oxidative stress according to the literature (1, 54). Mouse recombinant ERK-2 (250 ng, 0.2 μm) was incubated in the presence of 0, 0.01, 0.10, 1.00, 10.0, or 100 μm 4-HNE in 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, for 4 h at 37 °C, corresponding to 4-HNE/ERK-2 molar ratios of 0.05:1, 0.5:1, 5:1, 50:1, and 500:1, respectively. The reactions were stopped by the addition of 6× SDS-PAGE loading buffer, mixed thoroughly, and incubated at 100 °C for 5 min for immunoblot analysis.

Statistical Analysis

The numerical data associated with each blot are presented as relative abundance and normalized to that of control, which was given a value of 1. Comparisons were made between control and ethanol-treated animals or between control and 4-HNE-treated primary cultures and presented as fold increase from control values. The data are presented as the mean ± S.E. (n ≥ 3). Where applicable, statistically significant differences between ethanol-treated and pair-fed controls were determined using the paired t test, and differences between control and 4-HNE-treated cells were determined using the Student’s t test feature of SigmaPlot 6.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Sequence Analysis of ERK-2

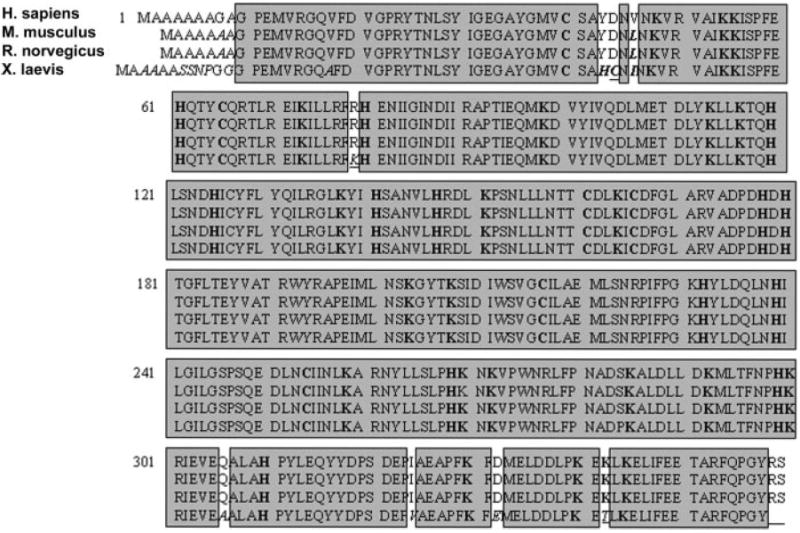

Amino acid sequence alignment of ERK-2 (or the ERK-2 homologue, myelin basic protein kinase) from H. sapiens, M. musculus, R. norvegicus, and X. laevis revealed a highly conserved core region across these species that was >96.5% identical to the human sequence (Fig. 1). Because 4-HNE preferentially modifies Cys, His, and Lys residues (15), these sequences were evaluated to establish the conservation of these target sites for each species of ERK-2 when compared with human. The total number of residues for human, mouse, rat, and Xenopus ERK-2 that are potential targets for 4-HNE modification are 43, 43, 43, and 45 per protein monomer, respectively (Table 1). As expected from the sequence alignment, these sites were also highly conserved. These results support the use of experimental variants of ERK-1/2 as appropriate alternatives to the human form.

FIGURE 1. Primary amino acid sequences of ERK-2 protein from human and common experimental animals showing greater than 96% homology across the species.

The primary sequences of ERK-2 from H. sapiens (top row), M. musculus (2nd row), R. norvegicus (3rd row), and X. laevis (4th row) were obtained from NCBI (P28482, P63085, P63086, and P26696, respectively) and aligned to the human primary sequence. Highlighted regions of these sequences indicate homologous sequences across the species that are greater than 98% identical to human for mouse and rat and greater than 96% identical to human for Xenopus, indicating that experimental alternatives to human are appropriate for studies focused on the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway.

TABLE 1. Conservation of nucleophilic amino acids (aa) preferentially reactive toward 4-HNE.

Primary amino acid sequences of ERK-2 from human, M. musculus, R. norvegicus, and X. laevis were examined to determine the number of potential residues reactive toward 4-HNE, namely cysteine, histidine, and lysine, and to establish that these sites are conserved across experimental species when compared with the human sequence. Despite subtle differences in their primary sequences, all species variants of ERK-2 possessed the 7 cysteine, 13 histidine, and 23 lysine residues that were observed within the human, primary ERK-2 sequence, indicating that the mechanistic modification of nucleophilic sites by 4-HNE would act through conserved residues.

| Cysteine residues | Histidine residues | Lysine residues | Total potential targets | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | 7 | 13 | 23 | 43/360 aa |

| M. musculus | 7 | 13 | 23 | 43/358 aa |

| R. norvegicus | 7 | 13 | 23 | 43/358 aa |

| X. laevis | 8 | 14 | 23 | 45/361 aa |

Chronic Ethanol Administration Results in 4-HNE Modification of Hepatic ERK-1/2 and Suppression of ERK-1/2 Phosphorylation

Oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, and 4-HNE production has been shown in patients associated with both acute and chronic ethanol consumption (55). Because we are interested in initiation and sensitizing events in ALD, a rat model of early ALD (34-36) utilizing a modified Lieber-De-Carli diet to produce blood-ethanol concentrations, lipid peroxidation, and pathologic liver changes consistent with early ALD in humans (56) was used to determine the ethanol-induced effects of chronic alcohol consumption on constitutive, hepatic ERK-1/2 activity and localization. Table 2 demonstrates that this model of ALD results in a moderate but significant increase in serum alanine aminotransferase and ammonia levels and liver to body weight ratios over control, indicative of mild liver damage. Consistent with the data in Table 2, the results in Fig. 2, B and B2, reveal the loss of normal liver structure associated with the accumulation of lipid in hepatocytes following chronic ethanol ingestion, when compared with control livers (Fig. 2A). The pathology associated with ethanol consumption in this study was limited to steatosis and lacked indices of progressive ALD, such as inflammation and/or necrotic foci. Although diffuse, pan-lobular staining for 4-HNE-adducts occurs in control livers (Fig. 2C), the chronic administration of alcohol resulted in the pronounced accumulation of 4-HNE-modified proteins that are most prominent in the mid-zonal and periportal regions of the lobule and conspicuously absent in the pericentral zones (Fig. 2D). Under higher magnification (Fig. 2D2, ×80) prominent cytosolic accumulation of proteinaldehyde adducts is apparent, indicating a cellular compartmentalization in addition to the lobular patterning observed at the ×10 magnification. Similar to the distribution of 4-HNE-protein adducts observed in Fig. 2C, Fig. 2E shows a mild, diffuse immunopositive staining for total ERK-1/2 in the livers of control animals that is pan-lobular in distribution. Surprisingly, the lobular localization of ERK-1/2 is redistributed resultant to prolonged ethanol exposure (Fig. 2F) in a manner that follows 4-HNE-protein adduct accumulation (Fig. 2D), demonstrating a prominent cytosolic accumulation (Fig. 2F2) in the midzonal and periportal regions, yet lacking in the centrilobular zones. Using antibodies against total ERK-1/2, ×40 magnification reveals that chronic ethanol treatment results in a 2.39 ± 0.06-fold decrease in positive staining hepatocyte nuclei (Fig. 2F2; n = 7, p < 0.0001) that was paralleled by a 2.59 ± 0.06-fold decrease in phospho-ERK-1/2 positive staining hepatocyte nuclei (Fig. 2H) when compared with control numbers (Fig. 2G; n = 13, p < 0.0001). Although the number of positive staining nuclei (per ×40 field) decrease for total and phospho-ERK-1/2 from control to ethanol groups, the ratio of positive phospho-ERK/Total-ERK nuclei is unchanged between the two groups, with control ratios of 1.01 ± 0.08 and ethanol ratios of 0.93 ± 0.12, indicating ERK-1/2 phosphorylation and nuclear localization are directly correlated in this model. Although the pattern of staining that was observed in the ethanol-treated group using anti-4-HNE and anti-total ERK-1/2 antibodies was inconspicuous under low magnification when liver sections were stained against total and phospho-ELK-1, under high magnification there is a 2.63 ± 0.23-fold decrease in the number of hepatocyte nuclei staining positive for phosphorylated ELK-1 (per ×40 field) when ethanol groups are compared with control (Fig. 2, L and K, respectively; n = 9, p < 0.0004). This effect is independent of significant changes between control and ethanol groups in the number of hepatocyte nuclei per ×40 field staining positive for total ELK-1 (Fig. 2, I and J; control = 50.71 ± 3.94, ethanol = 52.00 ± 6.99, p = 0.8757). Accordingly, the ratio of phospho-ELK-1/total-ELK-1 decreases from 0.93 ± 0.10 in control livers to 0.34 ± 0.10 in ethanol livers, demonstrating dissociation between ELK-1 phosphorylation and nuclear localization in the liver under the conditions described here. These data indicate a close correlation between hepatic lipid peroxidation and ERK-1/2 cytosolic accumulation in the liver following chronic ethanol exposure in vivo, which results in the loss of constitutive signal transduction to the nuclear ELK-1 substrate.

TABLE 2. Physiologic and pathologic analysis of control and ethanol-treated animals indicating the mild pathology associated with this model of early ALD.

Comparison of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, ammonia levels, and the liver to body weight ratios between control and ethanol-treated animals indicate a moderate yet significant increase in all parameters following ethanol exposure (1.8-, 1.28-, and 2.34-fold over control). These increases indicate mild liver damage associated with the model of ALD used here.

| Treatment | ALT | Ammonia | Body weight | Liver weight | Liver/body ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| units/liter | μm | g | g | ||

| Control | 19 ± 3 | 176.7 ± 22 | 402.9 ± 11.9 | 11.5 ± 0.4 | 2.87 ± 0.08 |

| Ethanol | 35 ± 5a | 226.2 ± 23a | 315.3 ± 7.3a | 10.6 ± 0.5 | 6.73 ± 0.27a |

Values are p < 0.05, n = 16.

FIGURE 2. Ethanol-induced differences in rat liver pathology and the lobular and cellular localization of 4-HNE-protein adducts and ERK-1/2.

Representative serial sections of rat liver from animals fed a control liquid diet or a diet containing 35% ethanol-derived calories for 60 days. A, hematoxylin and eosin staining of a control liver section showing normal hepatolobular architecture with chords of hepatocytes radiating out from the central vein (CV) to the portal triad (PV), with clear linear sinuses between the chords (×10 magnification). B, hematoxylin and eosin staining of a liver section from an ethanol-treated rat demonstrating the loss of normal hepatic architecture and the accumulation of lipid (steatosis) within hepatocytes surrounding the central vein (×10 magnification). B2, ×80 magnification of the ethanol-treated liver section from B, showing the cytosolic accumulation of lipid within hepatocytes (microvesicular = small arrowheads, macrovesicular = large arrowheads). C, control liver section stained against 4-HNE-modified proteins that demonstrate a faint, pan-lobular positive staining (×10 magnification). D, 4-HNE-adduct staining indicating the ethanol-induced accumulation of protein adducts within the central lobular and mid-zonal regions and clearly absent in areas proximal to the central veins (×10 magnification). D2, ×80 magnification of D indicating the cytosolic accumulation of 4-HNE-protein adducts and the relative lack of positive nuclear staining (hematoxylin counterstain). E, control liver section stained against total ERK-1/2, indicating a diffuse pan-lobular staining (×10 magnification). F, total ERK-1/2 staining indicating the ethanol-induced accumulation of ERK protein within the central lobular and mid-zonal regions and clearly absent in areas proximal to the central veins, similar to observations made for 4-HNE-adduct accumulation in D (×10 magnification). F2, ×80 magnification of F demonstrating the cytosolic accumulation of ERK-1/2 and the distinct lack of positive nuclear staining in most cells (27/×40 field compared with 63/×40 field in control liver sections), also similar to observations made for the cellular accumulation of 4-HNE adducts in D2. G, control liver section stained against phospho-ERK-1/2, showing distinct positive staining nuclei (64/×40 field) throughout the tissue and moderate cytosolic staining (×40 magnification). H, phospho-Erk-1/2 staining indicating the ethanol-induced loss of positive nuclear staining (25/×40 field) with moderate cytosolic staining absent in the midzonal region (center of image, ×40 magnification). I, control liver section stained against total ELK-1 showing distinct positive nuclear staining (51/×40 field) throughout the tissue and diffuse cytosolic staining (×40 magnification). J, total ELK-1 staining of liver from an ethanol-treated animal. Although there is obvious loss of structural organization within the tissue, the number of positive staining nuclei per ×40 field is maintained (52/×40 field) when compared with control I. K, control liver section stained against phosphorylated ELK-1 demonstrating distinct positive nuclei (47/×40 field) throughout the tissue and diffuse cytosolic staining (×40 magnification). L, phospho-ELK-1 staining of ethanol-treated animal liver showing a significant loss of positive staining nuclei per ×40 field (18/×40 field) when compared with control (×40 magnification).

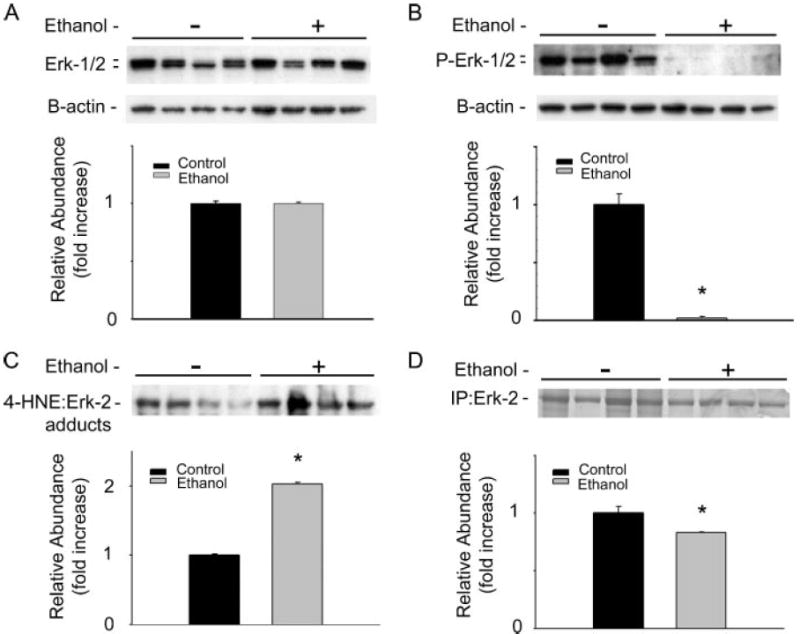

Immunoblot analysis was used to examine the consequences of chronic ethanol consumption on ERK-1/2 in total hepatocyte extracts from control and ethanol-treated animals. The data presented in Fig. 3A shows that no changes in total ERK-1/2 protein concentrations are observed in hepatocytes of ethanol-treated animals when compared with pair-fed controls. However, Fig. 3B demonstrates that chronic ethanol administration resulted in the ablation of constitutive ERK-1/2 phosphorylation. To evaluate the potential interactions of the lipid peroxidation product 4-HNE and ERK-1/2, ERK-2 was immunoprecipitated from hepatocyte extracts of control and ethanol-treated animals, and the extent of 4-HNE modification was determined using immunoblot analysis. Fig. 3C illustrates that chronic ethanol exposure significantly increased the amount of 4-HNE-ERK-2 protein monomer adducts in hepatocytes when compared with control animals (1.735-fold, ±0.295), which became increasingly greater when normalized to the total ERK protein immunoprecipitated (Fig. 3D, from p < 0.0244 to p < 0.0041). Fig. 3D shows the immunopurified ERK-2 band as a Coomassie-stained 42-kDa protein within the polyacrylamide gel, indicating a slightly greater amount of ERK-2 isolated from control animals when compared with ethanol-treated animals. The significant differences observed between the ethanol-treated groups for total ERK-1/2 immunoblot (Fig. 3A) and the immunoprecipitated ERK-2 (Fig. 3D) are likely due to differences in the polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies used, respectively. Collectively, these data suggest a mechanistic association between ethanol-induced lipid peroxidation and the inhibition of constitutive ERK-1/2 activity in the liver, and allude to the cytosolic accumulation of inactive 4-HNE-ERK-1/2 monomers.

FIGURE 3. Ethanol induces increased 4-HNE-ERK-1/2 adduct formation, which is inversely correlated with the loss of constitutive ERK-1/2 phosphorylation.

Immunoblot analysis using hepatocytes isolated from animals consuming control and ethanol-containing diets for 45 days is shown. A, immunoblot analysis of hepatocyte total ERK-1/2 concentrations, showing no effect of ethanol when compared with control (stripped blots reprobed for B-actin shows equal loading). B, immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated ERK-1/2 indicates that chronic ethanol ingestion ablates constitutive ERK-1/2 phosphorylation (stripped blots reprobed for B-actin shows equal loading). C, immunoblot and corresponding densitometry demonstrating chronic ethanol administration results in the significant increase in 4-HNE-ERK-2 adduct concentration as indicated by immunoprecipitated ERK-1/2, probed for 4-HNE-protein adducts. Corresponding densitometry analysis normalized to the total ERK-2 immunoprecipitated (D) indicates a significantly elevated level of adduct concentrations in ethanol-treated animals (p < 0.0042). D, total ERK-2 protein concentrations demonstrated by Coomassie Blue staining of immunoprecipitated ERK-2 and corresponding densitometry using hepatocyte lysates from control and ethanol-treated animals indicating increased concentrations of ERK-2 purified from control samples when compared with ethanol-treated samples (p < 0.05). (*, p < 0.05, n = 4.)

4-HNE Modulates ERK-1/2 Activity in Isolated Hepatocytes

To determine the effects of 4-HNE on ERK-1/2 signaling, primary rat hepatocyte cultures were exposed to concentrations of 4-HNE commonly associated with pro-oxidant-induced lipid peroxidation (57). To ensure that the effects of 4-HNE on ERK-1/2 signaling were not associated with cytotoxic hepatocyte responses to exogenous 4-HNE, cytotoxicity of 4-HNE over a range of physiologic concentrations was evaluated as the ratio of released LDH activity over total cellular LDH activity (Fig. 4A). These data show that, when compared with untreated controls (no cytotoxicity), 4-HNE concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 100 μm did not result in any significant cytotoxicity. Only at 1000 μm 4-HNE did a dramatic and significant increase in cytotoxicity occur, as determined by a 20-fold increase in LDH activity ratio (p < 0.0001). For subsequent experiments, nontoxic concentrations of 0.01–100 μm 4-HNE were used to investigate the effects of exogenous 4-HNE on hepatocyte ERK-1/2 signaling.

FIGURE 4. Sub-cytotoxic 4-HNE treatment of primary rat hepatocyte cultures results in a concentration-dependent decrease in ERK-1/2 phosphorylation and activity that is inversely correlated with the increase in 4-HNE-ERK-1/2 adduct concentration.

The cytotoxicity of 4-HNE after 4 h of treatment on primary rat hepatocytes was determined over a range of physiologic concentrations. A, cytotoxicity shown as the ratio of release LDH activity over total cellular LDH activity, indicating a lack of cytotoxicity from 0 to 100 μm 4-HNE. These sub-cytotoxic concentrations were used for subsequent primary culture experiments. B, immunoblot indicating a concentration-dependent decrease in ERK-1/2 phosphorylation when compared with constitutive control levels (lane 1, 0 μm 4-HNE) (B-actin reprobe of stripped blots confirms equal loading). C, immunoblot analysis of total ERK-1/2 protein indicating no change with increasing concentrations of 4-HNE treatment (B-actin reprobe of stripped blots indicates equal loading). D, ERK-1/2 activity assay demonstrating the concentration-dependent suppression of immunoprecipitated ERK-1/2 collected from primary cultures exposed to increasing levels of 4-HNE to phosphorylate the ELK-1 substrate. D, inset, active, phosphorylated IP-ERK-1/2 from control hepatocytes is not affected by increasing concentrations of 4-HNE, indicating 4-HNE-mediated effects on ERK-1/2 result from interactions with the inactive, unphosphorylated ERK monomers. E, Western blot analysis of activity assay components probed for 4-HNE-protein adducts indicating an inverse correlation between ERK-1/2 phosphorylation and activity and the concentration-dependent increase in 4-HNE-adducted ERK-1/2 levels in primary hepatocytes. (*, p < 0.05, n = 9.)

To evaluate the contribution of 4-HNE to the altered hepatic ERK phosphorylation state observed in vivo, primary rat hepatocyte cultures were exposed to subtoxic concentrations of 4-HNE over a 4-h period. Similar to the data from chronic ethanol treatment in vivo (Fig. 3A), the immunoblot and densitometry in Fig. 4B reveal that 4-HNE treatment of primary hepatocytes across a broad range of physiologic concentrations does not result in changes in total ERK-1/2 protein concentrations in total hepatocyte extracts. However, Fig. 4C illustrates a representative immunoblot with corresponding densitometry analysis for phosphorylated ERK-1/2 using total cell extracts from identical cells treated for 4 h with 0.00–100.0 μm 4-HNE. These data show that treatment of primary hepatocytes with 4-HNE leads to a marked concentration-dependent decrease in constitutive ERK-1/2 phosphorylation (50% at 100 μm), which becomes significant at aldehyde concentrations of 0.10 μm.

A nonradioactive IP kinase activity assay was used to determine whether 4-HNE-mediated inhibition of ERK-1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 4C) results in a correlative decrease in ERK-1/2 activity toward its substrate ELK-1. Initially, IP-phospho-ERK-1/2 from control hepatocytes was incubated with increasing concentrations of 4-HNE prior to analysis via kinase activity assay. Surprisingly, the immunoblot shown in the inset of Fig. 4D reveals that 4-HNE is incapable of affecting the activity of phosphorylated, active ERK-1/2 toward an ELK-1 fusion protein. Conversely, the immunoblot and densitometry in Fig. 4D represent the ability of IP-ERK-1/2 from cells treated with increasing concentrations of 4-HNE to phosphorylate ELK-1 fusion protein. Densitometry analysis of these data demonstrates that the decrease in ERK-1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 4C) correlates with a loss in ERK-1/2 kinase activity (Fig. 4D) and indicates that 4-HNE affects ERK-1/2 prior to activation in the cell. To establish that 4-HNE modification of ERK-1/2 was associated with the observed loss of ERK-1/2 activity, ERK-1/2 immunoprecipitated from hepatocytes exposed to increasing concentrations of 4-HNE was probed with the antibodies specific for 4-HNE-protein adducts. Fig. 4E demonstrates a significant concentration-dependent increase in adduct formation with aldehyde exposure that correlates with the loss of ERK-1/2 phosphorylation and activity shown in Fig. 4, C and D, respectively. These results show that in primary hepatocytes, the decrease in ERK-1/2 phosphorylation and activity resulting from increased 4-HNE treatment inversely correlate with the level of 4-HNE-ERK-1/2 monomer adduct concentration, which is consistent with observations made in vivo (Fig. 3, B and C).

4-HNE Attenuates Nuclear Concentrations of Total and Phospho-ERK-1/2 and Phospho-ELK-1

The activation of ERK-1/2 has been shown to affect various transcriptional and translational activities; however, the nuclear localization of ERK-1/2 is largely responsible for the transcriptional effects mediated by ELK-1 (42, 53, 58). Although the 4-HNE responses described above establish the aldehyde-mediated modulation of ERK-1/2 activation, it was important to determine whether these results parallel the modulation of active, nuclear ERK-1/2. The 4-HNE effects on ERK-1/2-mediated transcription were explored by comparing the activation state of nuclear ERK-1/2 with the cellular observations previously mentioned (Fig. 4, C and D) using primary hepatocytes treated with aldehyde as before. Nuclear proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE separation and immunoblot analysis using antibodies against total or phospho-specific ERK-1/2. The purity of nuclear proteins was determined by the absence of positive band staining on these nuclear blots when stripped and re-probed for the cytosolic marker GST-Ya (data not shown). Contrary to the studies using total cell extracts (Fig. 4, B and C), Fig. 5A shows a representative immunoblot, and corresponding densitometry analysis demonstrating incubation of hepatocytes with increasing 4-HNE leads to a concentration-dependent decrease in total nuclear ERK-1/2 concentrations, which are similar to ethanol-induced observations made in vivo (Fig. 2, E and F2). These results are associated with a corresponding decrease in phosphorylated, nuclear ERK-1/2, as demonstrated in Fig. 5B, which also correlate with ethanol-induced effects observed in the rat liver (Fig. 2, G and H). Because double phosphorylation and activation of ERK-1/2 are required for nuclear localization (44), these data indicate that adduction and inhibition via 4-HNE occur in the cytosolic compartment, resulting in the cytosolic accumulation of inactive, unphosphorylated 4-HNE-ERK-1/2 adducts.

FIGURE 5. Sub-cytotoxic 4-HNE treatment of primary rat hepatocyte cultures results in a concentration-dependent decrease in the in situ activity of ERK-1/2 that correlates with aldehyde-dependent decreases in phosphorylated and total ERK-1/2 in the nucleus.

A, Western blot analysis of nuclear phosphorylated ERK-1/2 shows a loss of positive staining with increasing 4-HNE concentrations used to treat primary hepatocytes. B, unlike the analysis of total cell lysates, analysis of total nuclear ERK-1/2 indicates that the loss of nuclear phospho-ERK-1/2 results from the 4-HNE-mediated decrease in total ERK-1/2 protein concentrations, a change indicative of cytosolic modification and inhibition. C, immunoblot analysis of total hepatocyte lysates probed against the ERK-1/2 substrate, ELK-1, shows no effect of 4-HNE on total nuclear ELK-1 concentrations. D, immunoblot analysis and densitometry of nuclear phosphorylated ELK-1 demonstrating a concentration-dependent inhibition of ERK-1/2 activity in situ as shown by a loss of phosphorylated substrate with increasing 4-HNE concentrations. (*, p < 0.05, n = 5.)

Immunoblot analysis of nuclear protein fractions from aldehyde-treated cells was used to determine the activity of nuclear ERK-1/2, by blotting against the ERK-1/2 substrate ELK-1. Fig. 5C shows that the concentration of total nuclear ELK-1 is unaffected by increasing concentrations of 4-HNE, an observation consistent with ethanol-related effects on total nuclear ELK-1 observed in vivo (Fig. 2, I and J). However, like the rat studies (Fig. 2, K and L), the phosphorylation state of nuclear ELK-1 decreases with increasing 4-HNE concentrations, which is indicative of a concentration-dependent loss of ERK-1/2 activity in the nucleus (Fig. 5D). These data further support the cytosolic adduction and inhibition of ERK-1/2, which renders the kinase pathway impotent toward the intermediate kinase and transcription factor ELK-1.

In Vitro Modification of ERK-2 by 4-HNE

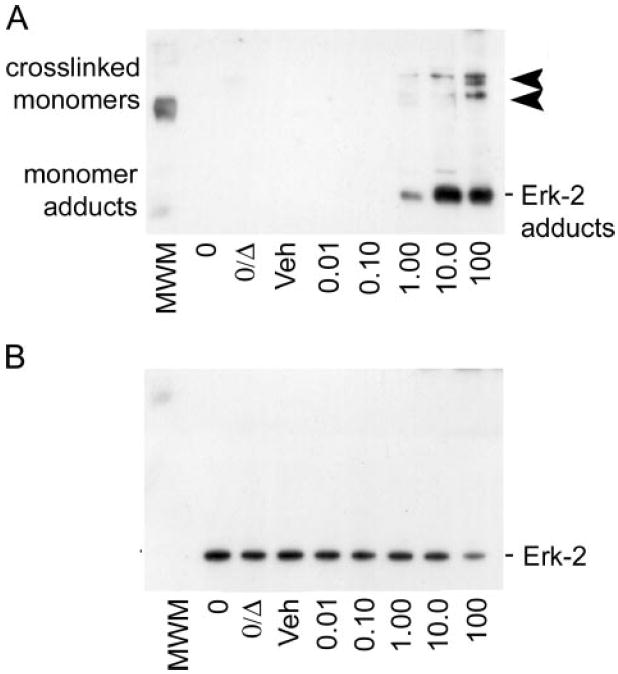

Because the evidence presented above suggests 4-HNE inhibits ERK-1/2 by forming adducts with the inactive, unphosphorylated ERK monomers, in vitro conditions were defined to test this hypothesis. Purified, recombinant ERK-2 from M. musculus (Cell Signaling) was incubated with concentrations of 4-HNE ranging from 0.01 to 100 μm, simulating molar ratios present during mild to marked oxidative stress. Fig. 6A is a representative immunoblot demonstrating 4-HNE-ERK-2 adducts using antibodies raised against 4-HNE-modified protein epitopes (3). This image indicates that stable adducts are formed at 42 kDa over 1–100 μm 4-HNE (5:1–500:1 molar ratios of 4-HNE to ERK-2). At the highest concentration evaluated, 4-HNE forms adducts resulting in cross-linked ERK-2 monomers as indicated by a partial band shift from 42-kDa at 1–100 μm 4-HNE to ~84 and 126-kDa at 100 μm 4-HNE (Fig. 6A, arrowheads). Concurrent with the formation of 4-HNE-ERK-2 cross-links, Fig. 6B shows a loss of a positive signal at 100 μm 4-HNE that occurs using identical blots probed for total ERK-1/2. This is likely due to the masking of epitopes that results from the formation of cross-linked monomers and/or the adduction of a different residue than that which results in monomer adducts. These experiments confirm that 4-HNE is capable of forming covalent adducts with inactive ERK protein monomers at molar ratios consistent with the formation of 4-HNE-ERK-1/2 monomer adducts observed in vivo following chronic ethanol exposure, and in primary cultures exposed to aldehyde. Because our rat model of early ALD and the subsequent primary hepatocyte experiments yield only the monomer adduct species, it appears that the formation of 4-HNE-ERK monomer adducts is responsible for the loss of ERK-1/2 phosphorylation and activity observed in the studies described here.

FIGURE 6. Pathologic molar ratios of 4-HNE to unphosphorylated ERK-2 protein result in the accumulation of aldehyde-monomer adducts similar to observations in vivo and in primary culture.

A, immunoblot analysis of inactive ERK-2 protein incubated with increasing physiologic concentrations of 4-HNE and probed for 4-HNE-protein adducts shows the formation of the 4-HNE-ERK-2 monomer adducts as the predominant adducted species (lower, 42-kDa bands). At the highest concentration (100 μm), 4-HNE adduction of unphosphorylated ERK-2 results in chemical cross-linking, as demonstrated by the partial shift from 42 to 82 and 126 kDa (arrowheads) for 4-HNE-adduct-positive staining bands. B, immunoblot analysis of the blot in A, when stripped and reprobed for total ERK-1/2 protein, that shows a partial loss of positive signal that correlates with the cross-linking of ERK-2 monomers at 100 μm 4-HNE. These data suggest that two distinct adduct species exist, where only the 100 μm 4-HNE treatment results in cross-linked adducts that preclude the recognition of the epitope by the total ERK-1/2 antibody.

DISCUSSION

4-HNE is the prototypic toxic end product of lipid peroxidation that results from oxidative stress (1), and lipid-aldehydes like 4-HNE are thought to be the major bioactive molecules that mediate the pathomechanisms associated with chronic alcoholic liver disease (3, 10, 11, 16, 34-36, 52, 54, 59, 60). Although this notion permeates a broad range of disease research, insufficient data are available to explain the mechanisms fundamental to 4-HNE-mediated disease progression in vivo. The present studies indicate that hepatic 4-HNE-protein adducts co-localize with ERK-1/2 following chronic ethanol consumption at the cellular and hepatolobular levels, and they demonstrate an increase in ethanol-induced 4-HNE-ERK-1/2 adduct concentration that inversely correlates with a loss of constitutive ERK-1/2 phosphorylation and nuclear localization in hepatocytes from ethanol-treated animals. These results are supported by observations showing a concentration-dependent decrease in ERK-1/2 phosphorylation, activity, and nuclear localization in primary hepatocytes following 4-HNE treatment. This mode of action by 4-HNE on ERK-1/2 activity is consistent with recent reports that demonstrate decreased phosphorylation of ERK-1/2 associated with neurological and vascular manifestations of chronic ethanol exposure in in vivo and primary culture (39-41), and the loss of hepatic ERK-1/2 sensitivity to chemical activation (ex vivo) following chronic ethanol ingestion (61). Although these published studies fail to demonstrate a specific mechanism of inhibition, ethanol-induced oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation have been demonstrated in hepatic and extra-hepatic tissues (62).

Because lipid peroxidation and the presence of 4-hydroxynonenal has been demonstrated within the liver using experimental models of ALD (9, 57, 63, 64) and clinically in human alcoholics (10, 11), it is facile to hypothesize that 4-HNE is involved in the dynamic evolution of ALD. Although there are many factors that converge to dictate the onset and severity of the pathogenesis related to ALD, the identification of 4-HNE as the most abundant and cytotoxic of the aldehydes resulting from lipid peroxidation indicates its importance in the etiology of the disease (65). In addition to the formation of reactive aldehydes through lipid peroxidation, ALD is also associated with the subsequent formation of covalent aldehyde-protein adducts (66-69). It is well known that ERK-1/2 is linked with cellular homeostasis in differentiated cells, such as hepatocytes (42, 44). In this study, the adduction of ERK monomers and corresponding inhibition of constitutive ERK-1/2 activity in hepatocytes in vivo and in primary culture represent a novel mechanism for ethanol-induced homeostatic imbalance in the liver that is mediated by 4-HNE. It is important to emphasize, given the nature of the early model of ALD used in this study, that these changes in normal ERK-1/2 signaling represent potential initiating and/or sensitizing mechanisms that are early events in the development of ALD. Recent research demonstrating that inhibition of ERK-1/2 signaling sensitizes cells to chemotoxic insult supports this hypothesis (70). This notion is important in the context of ALD, where cells can become sensitized early in the progression of a chronic disease where subsequent toxic insults are likely. Although others have suggested an association between 4-HNE and an increase in ERK-1/2 activity in immortalized cell lines (32, 71), the concurrent discovery that cell lines possess vastly different metabolic dispositions and sensitivities toward 4-HNE when compared with their primary counterparts, even when derived from cells of normal origin (72), makes them suspect in the context of in vivo relevance and further highlights potential cell-specific effects of reactive aldehydes. In addition to aberrations in normal ERK-associated homeostasis, inhibition of the ERK-1/2 pathway also implicates chronic ethanol exposure in alterations of normal hepatic gene transcription (43, 44).

Previous research has established the role of ERK-1/2 in mediating transcriptional gene regulation through the ERK-ELK-AP-1 signal transduction pathway (42-44). These published reports indicate that ERK-1/2 activity is responsible for the activation of the transcription factor ELK-1, and subsequently the AP-1 component c-Fos, and to a lesser extent c-Jun. Our research shows that ethanol-induced inhibition of ERK-1/2 results in the suppression of constitutive ELK-1 phosphorylation that is independent of changes in nuclear ELK-1 protein levels. Similarly, primary cells challenged with physiologic levels of 4-HNE demonstrate a concentration-dependent loss of constitutive ERK-1/2 phosphorylation, activity toward ELK-1, and nuclear localization resulting in a concentration-dependent suppression of nuclear ELK-1 phosphorylation that is indicative of 4-HNE modulation of normal hepatocyte gene expression. Activation of AP-1 through the upstream ERK-ELK kinase mediators results in gene expression associated with cell homeostasis, proliferation, and cell survival (42, 53, 58). Indeed, much effort has been expended to identify inhibitors of ERK-1/2 in cancerous cells for use as novel chemotherapeutic agents (53, 70) that negatively impact cell proliferation and/or induce apoptosis. In light of previous experimental data that demonstrate the ethanol-driven inhibition and/or delay of hepatic regeneration following surgical and chemical liver damage (45, 46), this study implicates the involvement of ethanol-induced lipid peroxidation and the subsequent inhibition of the proliferative/pro-survival ERK-1/2 signaling pathway by 4-HNE in this phenomenon. This hypothesis is substantiated by the data presented here, showing a loss of nuclear ERK-1/2 in vivo and in primary hepatocytes and the 4-HNE-mediated decrease of ERK-1/2 activity and ELK-1 phosphorylation.

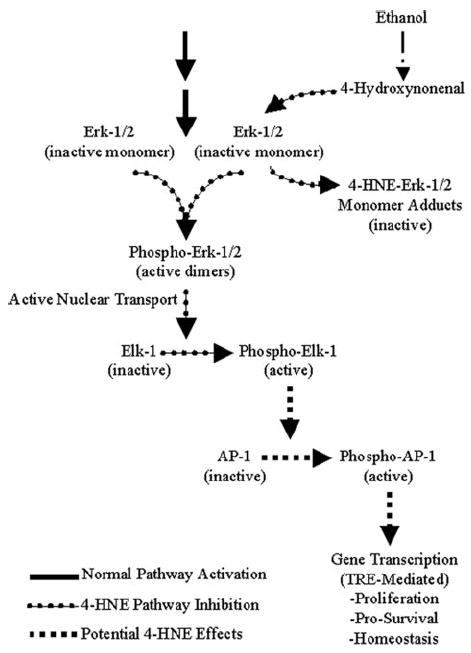

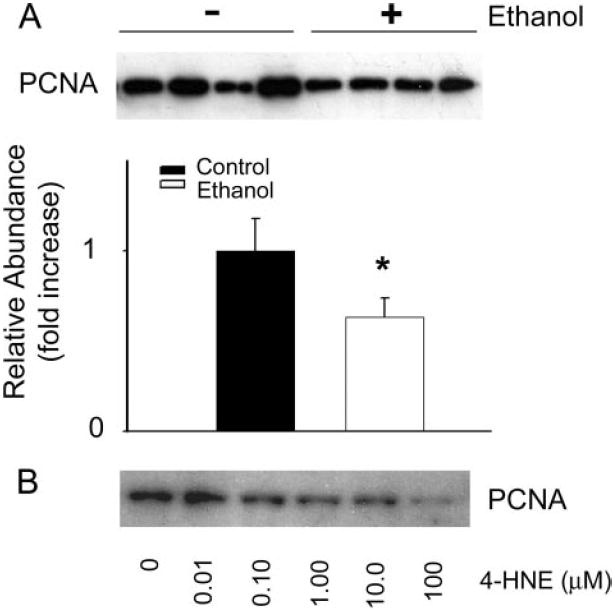

Under conditions of homeostatic balance, divergent MAPK pathways control the juxtaposed expression of pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic transcription factors such as c-Fos and c-Jun (58, 73, 74). Here we have shown that the repeated chemical insults associated with ALD result in the 4-HNE-mediated impairment of constitutive ERK-1/2 signaling through ELK-1 in hepatocytes (Fig. 7, dotted arrows). This event could lead to the loss of constitutive AP-1 transcriptional activity, resulting in a decrease in proliferative/anti-apoptotic gene expression (Fig. 7, dashed arrows). Although the liver is typically considered a quiescent organ, the average turnover rate of hepatocytes is know to be ~300 days. Given that there are roughly 300–600 million hepatocytes in the rat liver (data based on current hepatocyte isolation protocols used in this study), statistically there should be an approximate daily turnover of 1–2 million cells. Consequently, hepatocyte nuclear extracts from the animals used in this study were evaluated for changes in PCNA levels, which demonstrate a significant decrease in PCNA staining in ethanol liver extracts when compared with controls (Fig. 8A; n = 12, p > 0.005). Preliminary investigations into the role of 4-HNE in the decreased hepatocyte proliferation observed following chronic ethanol ingestion indicates that increasing concentrations of exogenous 4-HNE added to primary control rat hepatocytes decrease PCNA levels and therefore basal hepatocyte proliferation. Although these data are preliminary and warrant further investigation, these observations suggest that decreases in constitutive levels of hepatocyte proliferation following chronic ethanol intake may also be mediated by the effects of 4-HNE on ERK-1/2 signaling shown in the studies presented here. Additionally, research by Parola and co-workers (26, 31) demonstrates the ability of 4-HNE to increase the activity of the MAPK c-Jun amino-terminal kinase (JNK), a known pro-apoptotic pathway, which could further affect the apoptotic balance in hepatocytes. Although studies by Parola and co-workers (26, 31) suggest that 4-HNE has no effect on ERK-1/2 activity in hepatic stellate cell cultures, recent evidence indicates that chemical inhibitors of ERK-1/2 are capable of concurrently inducing the JNK signaling pathway, disrupting the apoptotic balance in favor of programmed cell death (53). Additional evidence indicates the ability of 4-HNE to induce apoptosis in several other cell types (75-79). Although major functional diversity exists among the MAPK family members, the highly conserved nature of MAPK sequences (43, 44) suggest that numerous 4-HNE target residues likely exist for all family members. It is therefore probable, under conditions of chronic ethanol insult and repeated situations of lipid peroxidation, that the production of 4-HNE simultaneously decreases the pro-survival ERK-1/2 signaling pathway while increasing the pro-apoptotic JNK signaling pathway through aldehyde-protein adduct formation at different functionally sensitive residues. Although this seems a likely hypothesis, terminal dUTP nick-end labeling staining of liver sections from control and ethanol-treated animals used in this study revealed no change in apoptotic incidence (data not shown; TACS TdT 3′,3′-diaminobenzidine kit, R & D Systems), indicating that the inhibition of ERK-1/2 signaling observed here effects homeostasis and proliferation without affecting the apoptotic balance of the hepatocyte.

FIGURE 7. Alterations to ERK-1/2 signaling pathway imposed by 4-HNE.

In normal non-ethanol-exposed and non-aldehyde-exposed hepatocytes, upstream kinase events (solid arrows) cascade down through ERK-1/2 to phosphorylate and activate this signaling intermediate, resulting in the active transport of ERK-1/2 into the nucleus where phosphorylation of downstream ELK-1 and subsequently AP-1 (c-Fos, and to a lesser extent c-Jun) result in transcriptional activity. During ethanol-induced lipid peroxidation, 4-HNE forms covalent adducts with inactive ERK-1/2 in the cytosol, preventing its phosphorylation, activation, and nuclear translocation, which results in the loss of downstream ELK-1 activity (dotted arrows). The 4-HNE-mediated inactivation of ERK-1/2 and the subsequent loss of ELK-1 activity could potentially result in the loss of normal transcriptional activity through the c-Fos and c-Jun AP-1 transcription factors associated with proliferation, cell survival, and homeostasis (dashed arrows).

FIGURE 8. Ethanol and 4-HNE suppress basal hepatocyte proliferation.

A, representative immunoblot analysis and corresponding densitometry analysis of PCNA using nuclear extracts of hepatocytes isolated from control animals (1st to 4th lanes, left to right) and animals consuming ethanol for 45 days (5th to 8th lanes, left to right) showing a 36.7% ethanol-dependent decrease in constitutive cell proliferation when compared with control levels (n = 12, p < 0.005). B, preliminary data showing an immunoblot for PCNA using nuclear extracts from primary hepatocytes treated with increasing concentrations of 4-HNE, suggesting a concentration-dependent decrease in cell proliferation with increasing 4-HNE.

Interestingly, the treatment of primary hepatocytes with concentrations of 4-HNE up to 100 μm resulted in a substantial yet incomplete inhibition of constitutive ERK-1/2 phosphorylation. At the origin of lipid peroxidation within membranes, cellular concentrations of 4-HNE have been estimated to exceed 1 mm (54). Subsequent experiments have shown that treatment with 1 mm 4-HNE results in the complete ablation of ERK-1/2 phosphorylation in primary hepatocyte cultures (data not shown). However, this concentration of aldehyde was determined to be significantly cytotoxic under these conditions and therefore outside the scope of this investigation. Additionally, it is conceivable that other toxic mediators associated with ethanol-induced lipid peroxidation elicit synergistic effects resulting in the complete inhibition of this pathway, as seen in vivo. Previous studies supporting this concept show that the ethanol metabolite acetaldehyde enhances the covalent modification of cellular molecules by the lipid peroxidation product malondialdehyde (68, 80, 81). It must also be acknowledged that the loss of ERK-1/2 phosphorylation observed in this study may be confounded by 4-HNE modification and inhibition of upstream kinases (i.e. MEK-1/2) or stimulation of MAPK phosphatases, although a significant accumulation of inactive nuclear ERK-1/2 would be anticipated for this latter explanation as reported elsewhere (82). Ultimately, these novel findings illustrated in Fig. 7 suggest that 4-HNE is capable of modulating the homeostatic, proliferative, and pro-survival ERK-1/2 signal transduction pathway in hepatocytes, resulting in the loss of signaling through ELK-1 and potentially through the family of AP-1 transcription factors.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AA009300.

The abbreviations used are: 4-HNE, 4-hydroxynonenal; ALD, alcoholic liver disease; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; ERK-1/2, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; ELK-1, Ets-like protein; AP-1, activating protein 1; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; JNK, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PI, protease inhibitor; IP, immunoprecipitate.

References

- 1.Esterbauer H, Schaur RJ, Zollner H. Free Radic Biol Med. 1991;11:81–128. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(91)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ishii H. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:A162–A167. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartley DP, Kroll DJ, Petersen DR. Chem Res Toxicol. 1997;10:895–905. doi: 10.1021/tx960181b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poli G, Schaur RJ. IUBMB Life. 2000;50:315–321. doi: 10.1080/713803726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benedetti A, Casini AF, Ferrali F, Comporti M. Biochem J. 1979;180:303–312. doi: 10.1042/bj1800303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uchida K, Stadtman ER. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6388–6393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kono H, Arteel GE, Rusyn I, Sies H, Thurman RG. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30:403–411. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00490-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsukamoto H, Horne W, Kamimura S, Niemela O, Parkkila S, Ylaherttuala S, Brittenham GM. J Clin Investig. 1995;96:620–630. doi: 10.1172/JCI118077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sampey BP, Korourian S, Ronis MJ, Badger TM, Petersen DR. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1015–1022. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000071928.16732.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paradis V, Kollinger M, Fabre M, Holstege A, Poynard T, Bedossa P. Hepatology. 1997;26:135–142. doi: 10.1053/jhep.1997.v26.pm0009214462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paradis V, Mathurin P, Kollinger M, ImbertBismut F, Charlotte F, Piton A, Opolon P, Holstege A, Poynard T, Bedossa P. J Clin Pathol. 1997;50:401–406. doi: 10.1136/jcp.50.5.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poli G, Dianzani MU, Cheeseman KH, Slater TF, Lang J, Esterbauer H. Biochem J. 1985;227:629–638. doi: 10.1042/bj2270629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grune T, Siems WG, Schneider W. Free Radic Biol Med. 1993;15:125–132. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(93)90051-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teare JP, Greenfield SM, Watson D, Punchard NA, Miller N, Rice-Evans CA, Thompson RPH. Gut. 1994;35:1644–1647. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.11.1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doorn JA, Petersen DR. Chem Res Toxicol. 2002;15:1445–1450. doi: 10.1021/tx025590o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishii T, Tatsuda E, Kumazawa S, Nakayama T, Uchida K. Biochemistry. 2003;42:3474–3480. doi: 10.1021/bi027172o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaur RJ, Zollner H, Esterbauer H. Membrane Lipid Peroxidation. Vol. 3. CRC Press, Inc.; Boca Raton, FL: 1990. pp. 141–163. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watanabe T, Pakala R, Katagiri T, Benedict CR. Atherosclerosis. 2001;155:37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00526-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruef J, Rao GN, Li FZ, Bode C, Patterson C, Bhatnagar A, Runge MS. Circulation. 1998;97:1071–1078. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.11.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zarkovic N, Ilic Z, Jurin M, Schaur RJ, Puhl H, Esterbauer H. Cell Biochem Funct. 1993;11:279–286. doi: 10.1002/cbf.290110409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bae MA, Soh Y, Pie JE, Song BJ. FASEB J. 2000;14:A1516. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malecki A, Garrido R, Mattson MP, Hennig B, Toborek M. J Neurochem. 2000;74:2278–2287. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0742278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li L, Hamilton RF, Kirichenko A, Holian A. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1996;139:135–143. doi: 10.1006/taap.1996.0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leonarduzzi G, Scavazza A, Biasi F, Chiarpotto E, Camandola S, Vogl S, Dargel R, Poli G. FASEB J. 1997;11:851–857. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.11.9285483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamilton RF, Hazbun ME, Jumper CA, Eschenbacher WL, Holian A. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1996;15:275–282. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.15.2.8703485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parola M, Robino G, Marra F, Pinzani M, Bellomo G, Leonarduzzi G, Chiarugi P, Camandola S, Poli G, Waeg G, Gentilini P, Dianzani MU. J Clin Investig. 1998;102:1942–1950. doi: 10.1172/JCI1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ji C, Kozak KR, Marnett LJ. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:18223–18228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101266200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Camandola S, Scavazza A, Leonarduzzi G, Biasi F, Chiarpotto E, Azzi A, Poli G. Biofactors. 1997;6:173–179. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520060211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Camandola S, Poli G, Mattson MP. J Neurochem. 2000;74:159–168. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0740159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Page S, Fischer C, Haas M, Baumgartner B, Loidl G, Hayn M, Neumeier D, Brand K. Atherosclerosis. 1999;144:10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robino G, Parola M, Marra F, Pinzani M, Bellomo G, Leonarduzzi G, Camandola S, Gentilini P, Dianzani MU. Hepatology. 1997;26:973. doi: 10.1172/JCI1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iles KE, Dickinson DA, Wigley AF, Welty NE, Forman HJ. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35:S67. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okada K, Wangpoengtrakul C, Osawa T, Toyokuni S, Tanaka K, Uchida K. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23787–23793. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.23787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carbone DL, Doorn JA, Kiebler Z, Sampey BP, Petersen DR. Chem Res Toxicol. 2004;17:1459–1467. doi: 10.1021/tx049838g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carbone DL, Doorn JA, Kiebler Z, Petersen DR. Chem Res Toxicol. 2005;18:1324–1331. doi: 10.1021/tx050078z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carbone DL, Doorn JA, Kiebler Z, Ickes BR, Petersen DR. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:8–15. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.088088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aroor AR, Shukla SD. Life Sci. 2004;74:2339–2364. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen JP, Ishac EJN, Dent P, Kunos G, Gao B. Biochem J. 1998;334:669–676. doi: 10.1042/bj3340669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davis MI, Szarowski D, Turner JN, Morrisett RA, Shain W. Neurosci Lett. 1999;272:95–98. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00572-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chandler LJ, Sutton G. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:672–682. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000158935.53360.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hendrickson RJ, Cahill PA, McKillop IH, Sitzmann JV, Redmond EM. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;362:251–259. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00771-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cobb MH, Hepler JE, Cheng MG, Robbins D. Semin Cancer Biol. 1994;5:261–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pearson G, Robinson F, Gibson TB, Xu BE, Karandikar M, Berman K, Cobb MH. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:153–183. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.2.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Z, Gibson TB, Robinson F, Silvestro L, Pearson G, Xu BE, Wright A, Vanderbilt C, Cobb MH. Chem Rev. 2001;101:2449–2476. doi: 10.1021/cr000241p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duguay L, Coutu D, Hetu C, Joly JG. Gut. 1982;23:8–13. doi: 10.1136/gut.23.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wands JR, Carter EA, Bucher NLR, Isselbacher KJ. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:528–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lindros KO, Jarvelainen HA. Alcohol Alcohol. 1998;33:347–353. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a008403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hartley DP, Petersen DR. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:298–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hartley DP, Kolaja KL, Reichard J, Petersen DR. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1999;161:23–33. doi: 10.1006/taap.1999.8788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mitchell DY, Petersen DR. Hepatology. 1991;13:728–734. doi: 10.1016/0270-9139(91)92572-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tjalkens RB, Luckey SW, Kroll DJ, Petersen DR. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;359:42–50. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Luckey SW, Taylor M, Sampey BP, Scheinman RI, Petersen DR. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:296–303. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.033522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tyagi A, Agarwal R, Agarwal C. Oncogene. 2003;22:1302–1316. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Benedetti A, Comporti M, Esterbauer H. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980;620:281–296. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(80)90209-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meagher EA, Barry OP, Burke A, Lucey MR, Lawson JA, Rokach J, FitzGerald GA. J Clin Investig. 1999;104:805–813. doi: 10.1172/JCI5584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hall PM, Lieber CS, DeCarli LM, French SW, Lindros KO, Jarvelainen HA, Bode C, Parlesak A, Bode JC. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:S254–S261. doi: 10.1097/00000374-200105051-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kamimura S, Gaal K, Britton RS, Bacon BR, Triadafilopoulos G, Tsukamoto H. Hepatology. 1992;16:448–453. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840160225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Karin M. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16483–16486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luckey SW, Tjalkens RB, Petersen DR. Enzymol Mol Biol Carbonyl Metab. 1999;463:71–77. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4735-8_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carbone DL, Doorn JA, Petersen DR. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:1430–1439. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weng Y-I, Shukla SD. Alcohol. 2003;29:83–90. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(02)00325-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nordmann R, Rigiere C, Rouach H. Alcohol Alcohol. 1990;25:231–237. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a044996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Niemela O, Parkkila S, Ylaherttuala S, Villanueva J, Ruebner B, Halsted CH. Hepatology. 1995;22:1208–1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ronis MJJ, Butura A, Sampey BP, Shankar K, Prior RL, Korourian S, Albano E, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Petersen DR, Badger TM. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39:619–630. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Esterbauer H, Benedetti A, Lang J, Fulceri R, Fauler G, Comporti M. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;876:154–166. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(86)90329-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Niemela O. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;31:1533–1538. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00744-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Niemela O, Parkkila S, Bradford B, Iimuro Y, Thurman RG. Hepatology. 2001;34:694A. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tuma DJ, Thiele GM, Xu DS, Klassen LW, Sorrell MF. Hepatology. 1995;22:479. doi: 10.1002/hep.510230431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tuma DJ. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32:303–308. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00742-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jazirehi AR, Vega MI, Chatterjee D, Goodglick L, Bonavida B. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7117–7126. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Iles KE, Liu RM. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:547–556. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Canuto RA, Ferro M, Muzio G, Bassi AM, Leonarduzzi G, Maggiora M, Adamo D, Poli G, Lindahl R. Carcinogenesis. 1994;15:1359–1364. doi: 10.1093/carcin/15.7.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Karin M, Smeal T. Trends Biochem Sci. 1992;17:418–422. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Karin M, Liu ZG, Zandi E. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:240–246. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kruman I, BruceKeller AJ, Bredesen D, Waeg G, Mattson MP. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5089–5100. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-05089.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Herbst U, Toborek M, Kaiser S, Mattson MP, Hennig B. J Cell Physiol. 1999;181:295–303. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199911)181:2<295::AID-JCP11>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu W, Kato M, Akhand AA, Hayakawa A, Suzuki H, Miyata T, Kurokawa K, Hotta Y, Ishikawa N, Nakashima I. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:635–641. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.4.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ji C, Amarnath V, Pietenpol JA, Marnett LJ. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001;14:1090–1096. doi: 10.1021/tx000186f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bruckner SR, Estus S. J Neurosci Res. 2002;70:665–670. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ohya T. Biol Pharm Bull. 1994;17:1411–1413. doi: 10.1248/bpb.17.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mooradian AD, Reinacher D, Li JP, Pinnas JL. Nutrition. 2001;17:619–622. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(01)00580-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liu W, Akhand AA, Kato M, Yokoyama I, Miyata T, Kurokawa K, Uchida K, Nakashima I. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:2409–2417. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.14.2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]