Abstract

Background

Awareness of cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk has been linked to taking preventive action in women. The purpose of this study was to assess contemporary awareness of CVD risk and barriers to prevention in a nationally representative sample of women and to evaluate trends since 1997 from similar triennial surveys.

Methods and Results

A standardized survey about awareness of CVD risk was completed in 2009 by 1142 women ≥25 years of age, contacted through random digit dialing oversampled for racial/ethnic minorities, and by 1158 women contacted online. There was a significant increase in the proportion of women aware that CVD is the leading cause of death since 1997 (P for trend=<0.0001). Awareness among telephone participants was greater in 2009 compared with 1997 (54% versus 30%, P<0.0001) but not different from 2006 (57%). In multivariate analysis, African American and Hispanic women were significantly less aware than white women, although the gap has narrowed since 1997. Only 53% of women said they would call 9-1-1 if they thought they were having symptoms of a heart attack. The majority of women cited therapies to prevent CVD that are not evidence-based. Common barriers to prevention were family/caretaking responsibilities (51%) and confusion in the media (42%). Community-level changes women thought would be helpful were access to healthy foods (91%), public recreation facilities (80%), and nutrition information in restaurants (79%).

Conclusions

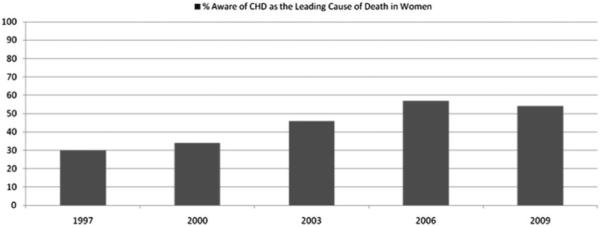

Awareness of CVD as the leading cause of death among women has nearly doubled since 1997 but is stabilizing and continues to lag in racial/ethnic minorities. Numerous misperceptions and barriers to prevention persist and women strongly favored environmental approaches to facilitate preventive action.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, prevention, women

American women continue to die of heart disease and stroke at a rate unparalleled by other diseases.1 The last decade has witnessed intensive public efforts to educate women about their risk of heart disease, and a recent national survey documented that awareness of heart disease among women nearly doubled in 10 years.2 Despite the progress, there remains a persistent racial and ethnic minority gap in awareness.2 Recent research has demonstrated a positive correlation between awareness that cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in women and recent action(s) taken to reduce CVD risk.3 These data suggest that continued educational campaigns, particularly those targeted to the highest-risk subgroups, could be important in reducing the burden of CVD among women.

Beginning in 1997, the American Heart Association (AHA) has conducted triennial surveys in random samples of women to track their awareness, knowledge, and perceptions related to heart disease and stroke according to race/ethnicity and age. The purpose of the present study was to assess the current level of awareness, knowledge, and perceptions in a nationally representative sample including an oversampling of black, Hispanic, and Asian women and to examine trends over time. An additional goal was to explore barriers to women taking preventive action.

Methods

Study Population and Survey Administration

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of 2300 women in the United States who were at least 25 years of age to assess their awareness, knowledge, and perceptions of CVD risk and prevention. The study was designed to result in a margin of error of approximately 2.0%. Survey data were compared with results from similar surveys conducted in 1997, 2000, 2003, and 20062,4-6 to examine trends in these parameters. In addition, characteristics of women surveyed by random digital dialing were compared with those of women surveyed online to develop a comparative framework for future online studies.

Potential participants were identified through 2 independent mechanisms: random-digit dialing (n=1142) similar to our previous surveys2,4-6 and a new online survey approach (n=1158). All surveys were conducted between July 1, 2009, and August 21, 2009, by representatives of Harris Interactive, New York, NY (telephone interviews) or via an online survey conducted through Harris Poll Online, a multimillion member panel of cooperative online respondents maintained by Harris Interactive. Both the telephone and online surveys consisted of the same 21 unique questions; 11 additional questions about health behaviors and changes were asked on the online survey. Both telephone and online surveys were administered in English and took approximately 18 minutes to complete.

Data were weighted based on age, race, education, income, and region to reflect the composition of the US population of women age 25 and older who speak English based on information from the US Census Bureau’s March 2008 Current Population Survey overall and within ethnic strata. Propensity weighting was used for the online survey to adjust for the respondents’ propensity to be online.

Using random-digit dialing, a total of 161 902 numbers were called. Of these, 48 625 (30%) were nonworking or government numbers, 5320 (3%) were unable to be completed due to privacy management equipment, and an additional 68 949 (43%) calls were unresolved due to the inability to talk directly with a person. Of the 39 008 calls successfully connected, a total of 19 464 were answered by individuals who declined to speak to an interviewer (50% refusal rate). An additional 3688 calls (9%) were not completed because of language barriers, and 6473 (17%) asked to be called back for an interview (5% of whom scheduled a specific call-back time). Screening interviews were completed in 9383 calls, with 4177 (45% of screened individuals) not eligible to participate either because of no woman ≥25 years of age in the household or refusal to allow contact with a woman ≥25 years of age in the household. Of the 5206 women who met criteria for participation, 1142 (22%) completed the survey.

An e-mail invitation was sent to 22 426 women members of Harris Poll Online. Harris Poll Online includes several million members invited from multiple sources to ensure a representative sample. Diverse methods are used to recruit panelists including: targeted e-mail and postal mail invitations, TV advertisements, and telephone recruitment.

Of these, 3660 (16%) were undeliverable, and, of the 1622 who opened the survey link, 222 did not complete the screening section and 79 (5%) did not meet eligibility criteria. Of the 1158 women who were qualified, all 1158 (100%) completed the survey. The complete survey is available in the online-only Data Supplement. All telephone and online participants were asked about demographic information followed by open-ended questions regarding leading cause of death in women and the single greatest health problem facing women. These questions replicated methods and sampling in previous AHA surveys of women’s awareness.2,4-6 In 2009, new questions on caregiving responsibilities and the burden and impact on their health were added. Only the online respondents were given questions about reasons for improving their own health, preventive actions they have taken in the past year, and barriers to incorporating healthy lifestyle behaviors. If someone refused or did not know an answer, the response was coded as “not sure” or “decline to answer,” and these percentages are not excluded from the analysis. In the online survey, respondents were not able to move to the next question before providing an answer to the current question.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics generated for baseline characteristics and survey responses are presented as proportions. Univariate relationships of responses between each racial/ethnic and age group as well as online versus telephone surveys were analyzed using t tests with software designed for marketing research (Quantum, SPSS, Chicago, Ill). A trend analysis was conducted using linear regression to evaluate women’s awareness across all survey years. Statistical significance was declared for P<0.05. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons.

Results

Characteristics of Respondents

The demographic and clinical characteristics of telephone respondents (n=1142) are listed in Table 1, overall and by race/ethnicity. Characteristics including education level did not differ from those of respondents who completed the first survey in 1997, except that 2009 participants were less likely to be 25 to 44 years of age (37% versus 47%), more likely to be married/cohabitating (64% versus 59%), and more likely to have a household income ≥100 000 (18% versus 5%). Survey results for demographic and clinical characteristics of online respondents (n=1158) are also included in Table 1 and do not materially differ from telephone results except that online responders were less likely to be in the 45- to 55-year age range or have less than a high school education. Unless otherwise noted, the results that follow are from telephone respondents only, to allow comparison to results from previous survey years with similar methodology.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Respondents in the 2009 AHA Women’s Health Survey

| Characteristic | All |

Race/Ethnic Group Telephone Respondents* |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| On-Line (n=1158) |

Telephone† (n=1142) |

White (n=660) [a] |

Black (n=128) [b] |

Hispanic (n=200) [c] |

Asian (n=125) [d] |

Other (n=29) [e] |

|

| Age, y | |||||||

| 25–34 | 16 | 18 | 16 | 16 | 25a | 20 | 26 |

| 35–44 | 23 | 19 | 18 | 24 | 20 | 27a | 16 |

| 45–54 | 19 | 24† | 24 | 19 | 28 | 21 | 33 |

| 55–64 | 20 | 18 | 18 | 19 | 15 | 18 | 19 |

| ≥65 | 21 | 21 | 24c,d | 21 | 13 | 14 | 5 |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Single, never married | 15 | 12 | 7 | 29a,c | 16a | 17a | 41 |

| Married/cohabitating | 67 | 64 | 71b,c | 35 | 55b | 67b | 47 |

| Separated/divorced | 12 | 12 | 12 | 17 | 15 | 9 | 8 |

| Widowed | 6 | 11 | 10 | 16d | 13d | 4 | 3 |

| Education | |||||||

| ≤Some high school | 5 | 9† | 7 | 16a,d | 14a,d | 5 | 18 |

| High school graduate | 38 | 33 | 33d | 32d | 39d | 12 | 38 |

| Some college | 17 | 19 | 18 | 22 | 17 | 16 | 18 |

| 2-Year college graduate | 9 | 9 | 10 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 2 |

| 4-Year college graduate | 19 | 19 | 20 | 13 | 14 | 34a,b,c | 18 |

| Postgraduate study | 12 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 10 | 26a,b,c | 5 |

| Household income, $ | |||||||

| <25 000 | 17 | 18 | 14 | 30a,d | 23a,d | 11 | 37 |

| <25 000 to 49 999 | 20 | 18 | 18 | 23 | 22 | 14 | 6 |

| <50 000 to 99 999 | 27 | 25 | 25 | 23 | 24 | 26 | 28 |

| ≥100 000 | 18 | 18 | 20b,c | 10 | 12 | 25b,c | 18 |

| Refused | 17 | 21 | 23 | 14 | 20 | 24 | 11 |

| Personal history of disease | |||||||

| Diabetes | 10 | 14 | 12 | 21a,d | 18d | 6 | 9 |

| Heart attack | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Stroke | 2 | 5† | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

Telephone results are presented for comparability with previously published survey results.

All values are weighted percentages.

Significant differences between online and telephone survey responses. Superscript letters denote significant differences at P<0.05 between racial/ethnic groups.

Awareness of and Perceptions Related to Heart Disease

The Figure illustrates trends in awareness of the leading cause of death among women surveyed from 1997 to 2009. In 2009, 54% of respondents correctly identified heart disease/heart attack as the leading cause of death among women. This was significantly higher than 1997 (30%; P for trend=<.0001) but not significantly different from the proportion aware in the survey administered in 2006 (57%; P=0.28). A majority of women surveyed online (65%) also correctly identified heart disease/heart attack as the leading cause of death.

Figure.

Overall trends in awareness that coronary heart disease is the leading cause of death in women.

Awareness that heart disease/heart attack is the leading cause of death has approximately doubled among white and Hispanic women and tripled among black women between the first survey in 1997 and the current 2009 survey. However a racial/ethnic disparity remains in the proportion aware by race/ethnic group (Table 2). In multivariate analysis adjusting for age and education level, African American, Hispanic, and Asian women were significantly less likely to be aware that heart disease/heart attack is the leading cause of death, compared with white women.

Table 2.

Awareness of Leading Cause of Death for Women and Perceived Greatest Health Problem Facing Women by Ethnic Group in 2009 Versus 1997

| Response (Unaided) | Overall 2009 |

Race/Ethnic Group* |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White [a] |

Black [b] |

Hispanic [c] |

Asian [d] 2009 |

||||||||

| 2009 | 1997 | P† | 2009 | 1997 | P† | 2009 | 1997 | P† | |||

| Leading cause of death | |||||||||||

| Breast cancer | 11 | 10 | 14 | 0.08 | 16 | 18 | 0.73 | 14 | 17 | 0.56 | 7 |

| Cancer (general) | 23 | 20 | 33 | <0.001 | 32a | 41 | 0.22 | 25 | 43a | 0.009 | 38 |

| Heart disease/heart attack | 54 | 60b,c,d | 33b,c | <0.001 | 43 | 15 | <0.001 | 44 | 20 | <0.001 | 34 |

| Other | 4 | 3 | 8 | 0.002 | 3 | 12 | 0.02 | 7a | 9 | 0.61 | 12a,b |

| Don’t know/no answer | 8 | 7 | 12 | 0.01 | 6 | 14 | 0.08 | 10 | 11 | 0.82 | 18a,b |

| Greatest health problem | |||||||||||

| Breast cancer | 28 | 25 | 34 | 0.005 | 32 | 38 | 0.41 | 31 | 34 | 0.66 | 25 |

| Cancer (general) | 18 | 18 | 27 | 0.002 | 19 | 28 | 0.16 | 24 | 25 | 0.87 | 17 |

| Heart disease/heart attack | 16 | 19c | 8 | <0.001 | 12 | 6 | 0.17 | 8 | 9 | 0.80 | 19c |

| Obesity | 8 | 8 | ... | ... | 7 | n/a | ... | 10 | ... | ... | 12 |

| Other | 20 | 20 | 16 | 0.14 | 20 | 15 | 0.39 | 18 | 16 | 0.71 | 13 |

| Don’t know/no answer | 9 | 8 | 15 | 0.002 | 9 | 13 | 0.40 | 10 | 16 | 0.22 | 14 |

Telephone results are presented for comparability between 1997 and 2009 surveys.

P values for tests of proportion between 1997 and 2009 telephone survey results. Ellipses indicate response not surveyed in 1997. All values are weighted percentages. Superscript letters denote significant differences at P<0.05 between racial/ethnic groups.

There were no differences in awareness of the leading cause of death in women by age group (Table 3). This differs from results from all previous survey years including 1997 in which younger women were significantly less aware compared with women in older age groups that heart disease/heart attack is the leading cause of death in women.4 Women 25 to 34 years of age were more likely than women ≥65 years of age to cite breast cancer as the greatest health problem facing women today (34% versus 22%; P<0.05).

Table 3.

2009 Awareness of Leading Cause of Death for Women and Perceived Greatest Health Problem Facing Women by Age Among Telephone Respondents

| Response (Unaided) | Age 25–34 y[a] |

Age 35–44 y[b] |

Age 45–64 y[c] |

Age ≥65 y[d] |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 (n=127) |

1997 (n=188) |

P | 2009 (n=159) |

1997 (n=294) |

P | 2009 (n=517) |

1997 (n=308) |

P | 2009 (n=338) |

1997 (n=195) |

P | |

| Leading cause of death | ||||||||||||

| Breast cancer | 14 | 19c,d | 0.37 | 10 | 17d | 0.10 | 12 | 12 | 0.99 | 7 | 9 | 0.47 |

| Cancer (general) | 27 | 38 | 0.12 | 18 | 33 | 0.006 | 24 | 36 | 0.004 | 24 | 34 | 0.03 |

| Heart disease/heart attack | 50 | 16 | <0.001 | 59 | 28a | <0.001 | 53 | 38a,b | 0.001 | 54 | 34a | <0.001 |

| Other | 2 | 12 | 0.009 | 6 | 10 | 0.24 | 4 | 7 | 0.14 | 5 | 9 | 0.12 |

| Don’t know/no answer | 7 | 15c | 0.09 | 7 | 12c | 0.17 | 8 | 7 | 0.68 | 11 | 14c | 0.38 |

| Greatest health problem | ||||||||||||

| Breast cancer | 34d | 41d | 0.34 | 29 | 40d | 0.06 | 28 | 34d | 0.15 | 22 | 20 | 0.64 |

| Cancer (general) | 9 | 19 | 0.05 | 15 | 26 | 0.03 | 21a | 26 | 0.19 | 26a,b | 37a,b,c | 0.02 |

| Heart disease/heart attack | 12 | 4 | 0.05 | 20 | 5 | <0.001 | 17 | 11a,b | 0.06 | 15 | 8 | 0.04 |

| Obesity | 9 | ... | ... | 7 | ... | ... | 8 | ... | ... | 8 | ... | ... |

| Other | 29c,d | 13 | 0.01 | 21 | 16 | 0.29 | 18 | 19 | 0.78 | 15 | 17 | 0.60 |

| Don’t know/no answer | 7 | 23b,c | 0.003 | 9 | 13 | 0.30 | 7 | 10 | 0.23 | 14c | 18c | 0.29 |

Telephone results are presented for comparability between 1997 and 2009 surveys.

All values are weighted percentages. Superscript letters denote significant differences at P<0.05 between age groups. P values are for tests of proportion between 1997 and 2009. Ellipses indicate response not surveyed in 1997.

Knowledge of Heart Disease

Forty-five percent of women surveyed in 2009 considered themselves to be very well or well informed about heart disease in women compared with 34% in 1997. Knowledge of heart attack warning signs did not appreciably differ from 1997.4 Fifty-six percent of women cited chest pain and neck, shoulder, and arm pain, 29% identified shortness of breath, and 17%, 15%, and 7% recognized chest tightness, nausea, and fatigue, respectively, as heart attack warning signs. When asked what they would do if they thought they were having signs of a heart attack, 53% of women reported that they would call 9-1-1 and 23% reported they would take an aspirin.

Perceived Heart Disease Risk Factors and Prevention Strategies

As in previous years, most participants recognized that lifestyle behaviors can prevent or reduce the risk of getting heart disease. Routine use of fish oil/omega-3 fatty acids (82%) and aspirin (78%) were also listed as top prevention strategies (Table 4). The proportion citing hormone replacement therapy as a prevention strategy was significantly less than in 1997 (19% versus 47%).4

Table 4.

Perception of Select Heart Disease Prevention Strategies

| Response (Aided) | All Subjects* |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 (n=1142) |

1997 (n=1000) |

P Value 2009 vs 1997 |

|

| Getting adequate sleep | 94 | ... | ... |

| Fish oil/omega-3 fatty acids | 82 | ... | ... |

| Take aspirin regularly | 78 | ... | ... |

| Fiber | 75 | ... | ... |

| Praying or meditating | 74 | ... | ... |

| Preventing gum disease | 74 | ... | ... |

| Antioxidants | 70 | ... | ... |

| Multivitamin | 69 | 50 | <0.001 |

| Special vitamins (eg, A, C, E) | 58 | 59 | 0.72 |

| Aromatherapy | 29 | 22 | 0.005 |

| Plant stanols and sterols | 24 | ... | ... |

| Hormone therapy | 19 | 47 | <0.001 |

All values are weighted percentages of telephone respondents who believe each activity can prevent or reduce the risk of getting heart disease. Ellipses indicate response not surveyed in 1997.

Sources of Information About Heart Disease

More than 85% of women reported that they had seen, heard, or read about women and heart disease in the past 12 months. These women were more likely to be aware that heart disease is the leading cause of death in women compared with their counterparts (58% versus 25%; P<0.0001). Women who had seen, heard, or read anything about the “red dress” symbol were more aware that heart disease is the leading cause of death in women compared with those who were not familiar with the “red dress” symbol (68% versus 43%; P<0.0001).

In 2009, more women reported television as their source of information about heart disease (45%) compared with magazines (32%), the newspaper (18%), or the Internet (14%). Additionally, 48% of women reported discussing heart disease with their doctor, an increase from 30% in 1997.

Caregiving and Preventive Action

Current caregiving (ie, providing care to an adult family member or friend) was reported by 29% of telephone respondents and 24% of women who completed the online survey. Among current caregivers, more than half reported spending 6 or more hours per week caregiving. When current caregivers were asked how they felt caregiving responsibilities have affected their heath, 22% of telephone respondents and 31% of online respondents reported a negative health impact. Among those reporting a negative impact, the primary ways caregiving negatively affected their health were (1) increased stress, (2) more exhaustion, (3) less time for one’s self, (4) trouble sleeping, and (5) not enough time to spend with other friends/family members.

Preventive Actions Taken in the Past Year

Preventive actions taken in the past year are presented in Table 5. Checking blood pressure (84%), trying to better manage stress (74%), and going to see a doctor or other health care professional (73%) were the top 3 preventive actions reported. Women 50 years of age and older were significantly more likely to take these preventive actions as well as to decrease consumption of unhealthy foods, have blood cholesterol levels checked, start taking vitamins or dietary supplements, quit using tobacco, or get a diagnostic test for heart disease compared with women under 50 years of age (P<0.001 for all comparisons). When asked what prompted them to take preventive actions, a majority of women responded that they wanted to improve their health and feel better (Table 5). Compared with younger women, those ≥50 years of age were more likely to be prompted to take action because they wanted to live longer, because they read, saw, or heard information related to heart disease, or because they had symptoms related to heart disease. Hispanic women were more likely than African American, Asian, or white women to report that they took preventive actions for their family (38% versus 19%, 19%, and 20%, respectively; P<0.05).

Table 5.

Preventive Actions Taken in the Past Year According to Race/Ethnicity and Age Group

| Preventive Action (Aided) | Overall (n=1158) |

White (n=634) |

Nonwhite | P* | Age <50 y (n=683) |

Age >50 y (n=475) |

P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Had blood pressure checked | 84 | 85 | 82 | 0.32 | 72 | 97 | <0.001 |

| Tried to better manage stress | 74 | 74 | 73 | 0.78 | 67 | 82 | <0.001 |

| Went to see a doctor or other health care professional | 73 | 74 | 71 | 0.41 | 60 | 87 | <0.001 |

| Decreased consumption of unhealthy foods | 71 | 74 | 65 | 0.02 | 64 | 79 | <0.001 |

| Had cholesterol checked | 66 | 68 | 63 | 0.20 | 47 | 87 | <0.001 |

| Increased physical activity | 63 | 63 | 63 | 0.99 | 61 | 65 | 0.33 |

| Started taking vitamins or dietary supplements | 56 | 58 | 53 | 0.22 | 46 | 68 | <0.001 |

| Lost weight | 51 | 51 | 53 | 0.63 | 50 | 53 | 0.48 |

| Quit smoking/using tobacco products | 29 | 25 | 38 | <0.001 | 16 | 44 | <0.001 |

| Got a diagnostic test for heart disease such as a stress test or heart scan |

26 | 26 | 26 | 0.99 | 12 | 42 | <0.001 |

| Prompt to take preventive action (aided) | |||||||

| I wanted to improve my health | 71 | 70 | 75 | 0.18 | 71 | 72 | 0.79 |

| I wanted to feel better | 63 | 62 | 64 | 0.61 | 64 | 61 | 0.46 |

| I wanted to live longer | 53 | 54 | 51 | 0.46 | 44 | 62 | <0.001 |

| I wanted to avoid taking medications | 29 | 27 | 33 | 0.11 | 26 | 31 | 0.19 |

| My healthcare provider encouraged me to | 28 | 30 | 23 | 0.06 | 17 | 38 | <0.001 |

| I did it for my family | 22 | 20 | 27 | 0.04 | 23 | 21 | 0.57 |

| A family member/relative developed heart disease, got sick, or died |

17 | 16 | 18 | 0.51 | 18 | 16 | 0.53 |

| Saw/heard/read information related to heart disease |

17 | 17 | 17 | 0.99 | 10 | 24 | <0.001 |

| I experienced symptoms related to heart disease | 15 | 15 | 16 | 0.74 | 12 | 19 | 0.02 |

| A family member encouraged me to | 7 | 7 | 8 | 0.64 | 8 | 7 | 0.65 |

| A friend developed heart disease, got sick, or died | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.99 | 1 | 3 | 0.09 |

| A friend encouraged me to | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0.42 | 4 | 1 | 0.02 |

Values represent the weighed percent of women surveyed online who reported taking each preventive action to improve her health in the past year.

P value for difference in proportion by race/ethnic group or by age group.

Barriers to Preventive Action

Top barriers to taking preventive action included family/caregiving responsibilities (51%) and too much confusion in the media about what to do (42%) (Table 6). There were no differences in barriers to preventive action reported by race/ethnic group except that white women and Asian women were more likely than African American and Hispanic women to report that there is too much confusion in the media. African American women were more likely than Asian, Hispanic, or white women to agree that God or some higher power ultimately determines their health.

Table 6.

Barriers to Living a Heart-Healthy Lifestyle by Race/Ethnicity and Age Group

| Barriers (Aided) | Overall (n=1158) |

White (n=634) |

Nonwhite (n=524) |

P* | Age <50 y (n=683) |

Age >50 y (n=475) |

P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I have family obligations and other people to take care of | 51 | 53 | 45 | 0.05 | 51 | 50 | 0.81 |

| There is too much confusion in the media about what to do | 42 | 44 | 36 | 0.048 | 43 | 41 | 0.63 |

| God or some higher power ultimately determines my health | 37 | 35 | 44 | 0.02 | 33 | 42 | 0.03 |

| I am not confident that I can successfully change my behavior | 33 | 33 | 34 | 0.80 | 36 | 30 | 0.13 |

| I do not have the money or insurance coverage to do what needs to be done |

32 | 31 | 35 | 0.30 | 35 | 29 | 0.13 |

| I do not perceive myself to be at risk for heart disease | 32 | 33 | 30 | 0.43 | 36 | 28 | 0.04 |

| I am to stressed to do the things that need to be done | 28 | 28 | 27 | 0.79 | 33 | 21 | 0.002 |

| I do not want to change my lifestyle | 28 | 30 | 25 | 0.18 | 32 | 24 | 0.04 |

| My health care professional does not think I need to worry about heart disease |

27 | 26 | 28 | 0.58 | 29 | 24 | 0.18 |

| I do not have time to take care of myself | 25 | 24 | 27 | 0.40 | 33 | 15 | <0.001 |

| I do not know what I should do | 25 | 24 | 27 | 0.40 | 30 | 20 | 0.007 |

| I am fearful of change | 22 | 22 | 20 | 0.55 | 25 | 18 | 0.04 |

| I am confused by what I am supposed to do to change my lifestyle |

21 | 22 | 18 | 0.23 | 24 | 17 | 0.04 |

| I feel the changes required are too complicated | 20 | 20 | 22 | 0.55 | 23 | 17 | 0.08 |

| My health care professional does not explain clearly what I should do |

19 | 18 | 21 | 0.35 | 21 | 17 | 0.23 |

| My friends/family have told me that I do not need to change | 16 | 17 | 15 | 0.51 | 18 | 15 | 0.34 |

| I do not think changing my behavior will reduce my risk of developing heart disease |

13 | 14 | 10 | 0.15 | 12 | 14 | 0.48 |

| I am too ill/old to make changes | 8 | 8 | 8 | 0.99 | 6 | 10 | 0.08 |

| My health care professional does not speak my language | 8 | 8 | 9 | 0.66 | 9 | 8 | 0.67 |

Values represent the weighted percent of women surveyed online who strongly or somewhat agreed that they experienced each barrier to living a heart healthy lifestyle.

P value for difference in proportion by race/ethnic group or by age group.

Online respondents were given a list of environmental/community level changes and asked whether they thought each one would be helpful or not helpful in leading them to follow a more heart-healthy lifestyle. A response of “helpful” was given by 91% of participants for access to better fruits, vegetables, and other healthy foods, 80% for greater access to indoor and outdoor public recreation facilities, 79% for requiring all restaurants to post nutrition information for menu items, 75% for smoking bans, 74% for stricter regulations on pollution, 73% for bans on trans fats in restaurants, and 62% for increased public safety in public recreation areas.

Discussion

Current data suggest that the level of awareness of heart disease as a leading cause of death among women has nearly doubled since 1997 and has remained steady for 3 years. Awareness among racial and ethnic minorities has significantly increased (though remains lower compared with whites), whereas the awareness gap among younger versus older women has narrowed. These data support the success of national educational programs to raise awareness of heart disease risk among women and highlight the need to sustain efforts to raise awareness, particularly among racial/ethnic minorities and young women, in whom the majority of women are unaware. In addition, programs to assist women in taking action steps to lower their risk may be prudent, given the substantial increased awareness that appears to have reached a plateau.

The finding that awareness among racial and ethnic minorities lags behind white women is consistent with several other studies that showed demographics and acculturation status was significantly associated with awareness and knowledge of CVD.7-11 African American women have a significantly higher rate of CVD compared with Caucasian women, yet their rate of awareness was substantially lower. This may impede risk reduction efforts because awareness of CVD has been linked to preventive action.6 In the current study, Asian women had the lowest rate of awareness of CVD risk; however, the sample size within subpopulations was small, so definitive conclusion cannot be drawn. Heart disease is now the leading cause of death in Chinese women, and rates of awareness are low.10 A recent study showed that Chinese-Canadians were less likely to receive heart disease education compared with other ethnic groups.12 In addition, less acculturated minorities have health beliefs that might impede prevention; these findings suggest that providers and public campaigns should be more aggressive in reaching out to racial and ethnic minorities.11

Of concern was the finding that only 53% of women stated they would call 9-1-1 if they thought they were having symptoms of a heart attack, and awareness of atypical symptoms of heart disease was low. There has been an emphasis on raising awareness of the range of symptoms of heart disease in women over the past decade.13 Women have been shown to have a significant time delay in receiving diagnostic and interventional procedures, which may contribute to a worse 30-day mortality rate compared with men.14,15 Educating women about early symptom recognition and calling 9-1-1 sooner may be an important strategy to reduce disparities in outcomes.

Notable in the current survey was the finding that a majority of women perceived that several unproven methods would reduce risk of heart disease, including use of multivitamins, antioxidants, and special vitamins (eg, vitamin C). This is a concern because recent randomized clinical trials showed no benefit of antioxidant vitamins in women.16 The AHA 2007 Evidence-Based Guidelines for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Women recommend against the use of aspirin in young women as a strategy to lower heart disease risk, yet the majority of women in this survey perceived it would benefit their heart.17

Several barriers to prevention were noted including caregiving responsibilities. Caregiving has been linked to an increased risk of CVD in women, possibly through suboptimal lifestyle habits and psychosocial risk factors.18,19 Future research should evaluate the influence of programs to educate and support caregivers on reducing their CVD risk.

There was an overwhelming response from women surveyed that environmental approaches such as increasing access to healthy foods, recreational facilities and nutrition labeling would be helpful for women to lower CVD risk. Health promotion approaches that focus on improving the environment have shown the potential to improve health behavior among those living in underserved areas.20 The WISEWOMEN project also showed that an intervention to increase use of community resources could help to overcome environmental barriers to a healthy lifestyle in low-income, underinsured women in midlife.21 Policymakers should take into consideration these findings in current national efforts to reduce the burden and costs associated with CVD.

This study was a cross-sectional sample of English-speaking women who were willing to complete a telephone interview or online survey and were relatively well-educated, so the results may not be generalizable to all women and may represent a best-case scenario. Trends observed are not likely caused by artifact because similar selection bias applied to prior surveys. Data in subpopulations, although oversampled, may not have been sufficient to draw definitive conclusions. We did not adjust for multiple comparisons, and some of the significant findings could be due to chance.

In conclusion, awareness of the leading cause of death among women has not significantly increased since 2006, but there has been a significant trend for improvement since 1997. Overall knowledge of this fact has doubled in white women since 1997 and tripled in black women, suggesting that the gap is beginning to close but still persists. The survey responses suggest that sustained educational efforts are needed to raise awareness, particularly among vulnerable populations. More emphasis should be placed on raising awareness of the symptoms of heart disease and informing women of the importance of calling 9-1-1. Many misperceptions remain about how to lower CVD risk; programs are needed to help women take action and should incorporate evidence-based prevention education.

WHAT IS KNOWN

Awareness of heart disease as the leading cause of death among women is suboptimal and a gap in awareness exists between whites and racial/ethnic minorities.

It is well established that delay in seeking emergency services is associated with greater cardiac mortality rates.

Clinical trials have demonstrated that some interventions (eg, antioxidant vitamin supplementation) do not prevent heart disease.

Environmental factors (such as limited availability of fresh fruits and vegetables, have been cited as barriers to heart-healthy living.

WHAT THE STUDY ADDS

Although levels of heart disease awareness have improved since 1997, almost half of women remain unaware that coronary heart disease is the leading cause of death among women, and the gap in awareness among minorities is closing.

The present study documents that only about one half of women would call 9-1-1 if they thought they were having symptoms of a heart attack.

A substantial percentage of women perceive that unproven preventive therapies will reduce their risk of heart disease.

Women support environmental approaches such as increased access to healthy foods, recreational facilities, and enhanced nutrition labeling to lower risk.

Acknowledgments

We thank Harris Interactive for their assistance with survey design and data analysis and Lisa Rehm, MPA, for assisting with the preparation of the manuscript.

Sources of Funding

The survey was funded by the American Heart Association through a grant from Macy’s Go Red For Women Multicultural Fund. Dr Mosca was supported in part by an NIH Research Career Award (K24 HL076346).

Footnotes

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at http://circoutcomes.ahajournals.org/cgi/content/full/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.915538/DC1.

Disclosures

K.J. Robb is an employee of the American Heart Association. Relationships with industry for Dr Newby are publically available at: http://www.dcri.duke.edu/research/coi.jsp.

References

- 1.American Heart Association . Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics: 2009 Update. American Heart Association; Dallas, Tex: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christian AH, Rosamond W, White AR, Mosca L. Nine-year trends and racial and ethnic disparities in women’s awareness of heart disease and stroke: an American Heart Association national study. J Womens Health. 2007;16:68–81. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.M072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mosca L, Mochari H, Berra K, Taubert K, Mills T, Burdick KA, Simpson SL. National study of women’s awareness, action, and barriers to cardiovascular health. Circulation. 2006;113:525. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.588103. AH. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mosca L, Jones WK, King KB, Ouyang P, Redberg RF, Hill MN, American Heart Association’s Women’s Heart Disease and Stroke Campaign Task Force Awareness, perception, and knowledge of heart disease risk and prevention among women. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:506–515. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.6.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robertson RM. Women and cardiovascular disease. the risks of misperception and the need for action. Circulation. 2001;103:2318–2320. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.19.2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosca L, Ferris A, Fabunmi R, Robertson RM, American Heart Association Tracking women’s awareness of heart disease: an American Heart Association national study. Circulation. 2004;109:573–579. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000115222.69428.C9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams RA. Cardiovascular disease in African American women: a health care disparities issue. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101:536–540. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30938-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Homko CJ, Santamore WP, Zamora L, Shirk G, Gaughan J, Cross R, Kashem A, Petersen S, Bove AA. Cardiovascular disease knowledge and risk perception among underserved individuals at increased risk of cardiovascular disease. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008;23:332–337. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000317432.44586.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamner J, Wilder B. Knowledge and risk of cardiovascular disease in rural Alabama women. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20:333–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao Y, DiGiacomo M, Du HY, Ollerton E, Davidson P. Cardiovascular disease in Chinese women: an emerging high-risk population and implications for nursing practice. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008;23:386–394. doi: 10.1097/01.JCN.0000317446.97951.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edelman D, Christian A, Mosca L. Association of acculturation status with beliefs, barriers, and perceptions related to cardiovascular disease prevention among racial and ethnic minorities. J Transcult Nurs. 2009;20:278–285. doi: 10.1177/1043659609334852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grunau GL, Ratner PA, Gaidas PM, Hossain S. Ethnic and gender differences in patient education about heart disease risk and prevention. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zbierajewski-Eischeid SJ, Loeb SJ. Myocardial infarction in women: promoting symptom recognition, early diagnosis, and risk assessment. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2009;28:1–6. doi: 10.1097/01.DCC.0000325090.93411.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berger JS, Elliott L, Gallup D, Roe M, Granger CB, Armstron PW, Simes RJ, White HD, Van de Werf F, Topol EJ, Hochman JS, Newby LK, Harrington RA, Califf RM, Becker RC, Douglas PS. Sex differences in mortality following acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2009;302:874–882. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nichol G, Thomas E, Callaway CW, Hedges J, Powell JL, Aufderheide TP, Rea T, Lowe R, Brown T, Dreyer J, Davis D, Idris A, Stiell I, Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium Investigators Regional variation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest incidence and outcome. JAMA. 2008;300:1423–1431. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.12.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cook NR, Albert CM, Gaziano M, Zaharris E, MacFadyen J, Danielson E, Buring JE, Manson JE. A randomized factorial trial of vitamins C and E and beta carotene in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular events in women: results from the Women’s Antioxidant Cardiovascular Study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1610–1618. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mosca L, Banka CL, Benjamin EJ, Berr K, Bushnell C, Ganiats T, Gomes AS, Gornick H, Gracia C, Gulati M, Haan CK, Judelson DR, Keenan N, Kelepouris E, Michos E, Oparil S, Ouyang P, Oz MC, Petitti D, Pinn VW, Redberg R, Scott R, Sherif K, Smith S, Jr, Sopko G, Steinhorn R, Stone NJ, Taubert K, Todd BA, Urbina E, Wenger N. 2007 Update: American Heart Association Evidence-Based Guidelines for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Women. Circulation. 2007;115:1481–1501. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.181546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee S, Colditz GA, Berkman LF, Kawachi I. Caregiving and risk of coronary heart disease in US women: a prospective study. Am J Prev Med. 2009;24:113–119. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00582-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aggarwal B, Liao M, Christian A, Mosca L. Influence of caregiving on lifestyle and psychosocial risk factors among family members of patients hospitalized with cardiovascular disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:93–98. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0852-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amuzu A, Carson C, Watt HC, Lawlor DA, Ebrahim S. Influence of area and individual lifecourse deprivation on health behaviours: findings from the British Women’s Heart and Health Study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 16:169–173. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e328325d64d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jilcott SB, Keyserling TC, Samuel-Hodge CD, Rosamond W, Garcia B, Will JC, Farris RP, Ammerman AS. Linking clinical care to community resources for cardiovascular disease prevention: the North Carolina Enhanced WISEWOMAN Project. J Women’s Health. 2006;15:569–583. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]