Abstract

Objectives

A diagnosis of prostate cancer may distract attention from routine prevention and treatment of other diseases in older men. We assessed survival and cause of death in men aged 65 and older diagnosed with prostate cancer, and in a non-cancer control population.

Design

Retrospective cohort from population-based tumor registry linked to Medicare claims data.

Setting

Eleven regions of the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Tumor Registry.

Participants

208,601 men aged 65–84 diagnosed with prostate cancer from 1988 through 2002 formed the basis for different analytic cohorts.

Measurements

Survival as a function of stage and tumor grade (low, Gleason grade < 7; moderate, grade = 7; and high, grade = 8–10) compared to men without any cancer, was assessed with Cox proportional hazards regression. Cause of death by stage and tumor grade were compared using chi square statistics.

Results

Men with early stage prostate cancer and with low to moderate grade tumors (59.1% of the entire sample) experienced a survival not substantially worse than men without prostate cancer. In those men, cardiovascular disease and other cancers were the leading causes of death.

Conclusion

The excellent survival of older men with early stage, low to moderate grade prostate cancer, along with the patterns of causes of death, implies that this population would be well served by an ongoing focus on screening and prevention of cardiovascular disease and other cancers.

Keywords: Prostate Cancer, Mortality, Survival and comorbidities

INTRODUCTION

Once a diagnosis of cancer has been made it can become the sole focus of medical care. This is understandable, since cancer is typically life threatening and often requires dramatic therapy. However, earlier cancer diagnoses, due to screening, and improvements in treatment have been associated with reduced cancer mortality, such that in 2003, there were an estimated 10 million cancer survivors in the United States [1]. Thus patients are living longer after a diagnosis of cancer, to the point where existing co-morbidities may have a substantial impact on their overall survival.

This is particularly true for men diagnosed with prostate cancer. Prostate cancer is the most common form of non skin cancer diagnosed in men, with seventy five percent of cases of prostate cancer occurring in men aged 65 years and older [2,3]. Prostate cancer can cause early mortality, especially in African American men who get the disease at a younger age and often have more aggressive tumors [2,4]. However, for many men prostate cancer may have little impact on their overall survival, especially in those with well to moderately differentiated tumors, given the slow natural progression and competing risk of death from other causes [5].

In this study, we examined the primary cause of death in men after the diagnosis of prostate cancer, comparing mortality due to prostate cancer to causes other than prostate cancer. We also examined survival and factors predicting survival after a prostate cancer diagnosis.

METHODS

Data source

Data from the linked Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Medicare database were used. SEER is a population based cancer registry which currently encompasses an estimated 25% of the U.S. population [6]. It includes information on month/year of diagnosis, stage, histology, and cause of death [6]. The Medicare database covers approximately 97% of American age 65 and older, and linkage to the SEER database was approximately 93% complete [7]. The version of the SEER-Medicare database used for this study included incident cases of cancer through 2002, Medicare claims through 2004, and SEER cause of death information through 2003.

Study Subjects

All men aged 65–84 listed in Seer-Medicare who received a primary diagnosis of prostate cancer in the years 1988 through 2002 in 11 SEER regions (San Francisco, Connecticut, Detroit, Hawaii, Iowa, New Mexico, Seattle, Utah, Atlanta, San Jose, and Los Angeles) were selected, for a total of 208,601 subjects. From this population, three overlapping study cohorts were built for our analytical strategies. First, survival analyses with up to 17 years of follow-up included patients aged 65–69 (n=56,991), 70–74 (n=59,108), 75–79 (n=43,342) and 80–84 (n=21,779) with a known stage. Second, for analyses on cause of death, men aged 65–84 and clinically diagnosed with prostate cancer (not from autopsy or death certificate) in 1992–1998 were included (n=103,086), to allow for five years of follow-up. Last, for analyses focused on the impact of comorbidities and cancer characteristics on survival, the subjects were limited to those aged 66–84 diagnosed in 1992–2002 (n=151,415), because complete Medicare data were unavailable prior to 1992. To ensure complete information for the last cohort, we excluded patients who were not enrolled in both Part A and Part B Medicare for the 12 months before and the 6 months after diagnosis (16,526 cases) or who were members of a health maintenance organization (34,465 cases), or whose disease had been diagnosed at autopsy or on a death certificate (1,036 cases). Tumor characteristics such as grade (low, Gleason less than 7; moderate, Gleason = 7; un- or poorly differentiated, Gleason 8 to 10) and clinical stage (T1 through T4) were derived from the SEER Patient Entitlement and Diagnosis Summary file (PEDSF). Comorbidity including myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diabetes was based on the relevant ICD-9 diagnosis codes from Medicare claims in the 12 months prior to diagnosis of cancer (one inpatient claim or at least two outpatient or physician claims more than 30 days apart) [8,9]. Age and ethnicity were derived from Medicare files in order to have data comparable in patients and in the non-cancer controls.

As a comparison group, we developed a non-cancer cohort from the 5% sample of Medicare beneficiaries residing in the SEER areas who do not have any cancer diagnosis in SEER. For our analytical strategies, two overlapping non-cancer cohorts were built. First, for survival analyses with up to 17 years of follow-up, men who were residents in a SEER area in 1988–2002 were selected. The initial study entry year for these men was assigned randomly to match the distribution for age and years of diagnosis of cancer in men in the prostate cancer cohort. Only subjects aged 65–69 (n= 15,192), 70–74 (n=16,040), 75–79 (n=12,245), and 80–84 (n=6550) were included in the analyses. Next, for analyses of the impact of comorbidities on survival, we selected men aged 66–84 years who were residents in a SEER area in 1992–2002, and had continuous part A and part B Medicare coverage, and were not enrolled in an HMO, for at least 18 consecutive months. The initial study entry year for these men was assigned randomly to match the distribution for years of diagnosis of cancer in men in the prostate cancer cohort. In this way, we constructed a cohort of 47,435 men without cancer, with follow-up through 2004.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic characteristics of the prostate cancer and non-cancer cohorts were compared using chi square statistics. Based on cause of death recode on SEER PEDSF, five-year mortality from prostate cancer and other major causes of mortality were calculated for patients diagnosed in 1992–1998 stratified by stage. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to generate survival curves. Multivariate survival analyses including covariates of age, ethnicity, stage, grade, and comorbidity were performed with the use of Cox proportional-hazards regression. The dependent variable was time to death. Patients were censored at death or at the end of the study (12/31/2004). All analyses were performed with the use of SAS software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the 99,388 men aged 66 to 84 diagnosed with prostate cancer between 1992 and 2002 and age-matched non-cancer controls selected from the 5% Medicare non-cancer sample. Of the prostate cancer patients, 81.0% were diagnosed with clinical stage T1 or T2 tumors, and 71.8% with low to moderate grade tumors. The randomly matched non-cancer controls were slightly younger, with fewer Blacks, and with a higher prevalence of comorbidities.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 99,388 Men Aged 66 to 84 Diagnosed with Prostate Cancer in 1992–2002 Along with 47435 Men without a Cancer Diagnosis*

| Characteristics | Prostate Cancer | Controls | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n= 99388 | n= 47435 | p-value# | |||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 73.6 ± 4.8 | 73.0 ± 4.9 | <0.0001 | ||

| Ethnicity† | White | 83.0% | 82.1% | <0.0001 | |

| Black | 10.2% | 6.1% | |||

| Hispanic | 1.7% | 2.7% | |||

| Other/Unknown | 5.1% | 9.1% | |||

| Comorbidity‡ | MI | 1.7% | 1.9% | 0.0278 | |

| CHF | 3.7% | 4.9% | <0.0001 | ||

| PVD | 2.0% | 2.5% | a | <0.0001 | |

| Stroke | 3.2% | 4.3% | <0.0001 | ||

| COPD | 7.3% | 7.7% | 0.0044 | ||

| Diabetes | 9.8% | 10.9% | <0.0001 | ||

| Clinical Stage | T1 | 26.6% | - | ||

| T2 | 54.4% | - | |||

| T3 | 5.4% | - | |||

| T4 | 5.8% | - | |||

| Unknown | 7.8% | - | |||

| Cancer Grade | Well differentiated | 10.6% | - | ||

| Moderated differentiated | 61.2% | - | |||

| Poorly differentiated or undifferentiated | 21.3% | - | |||

| Unknown | 6.9% | - | |||

Both prostate cancer patients and controls had 18 months Medicare Part A & B without HMO.

Information on ethnicity is from Medicare data in order to allow comparison with the noncancer controls sample. Medicare data on ethnicity during the 1990's substantially under reported Hispanic and Asian ethnicity [13].

MI = miocardial infarction; CHF = congestive heart failure; PVD = peripheral vascular disease; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

p-values were from either t-test or Chi-square test for the comparisons of characteristics between patients with prostate cancer and controls.

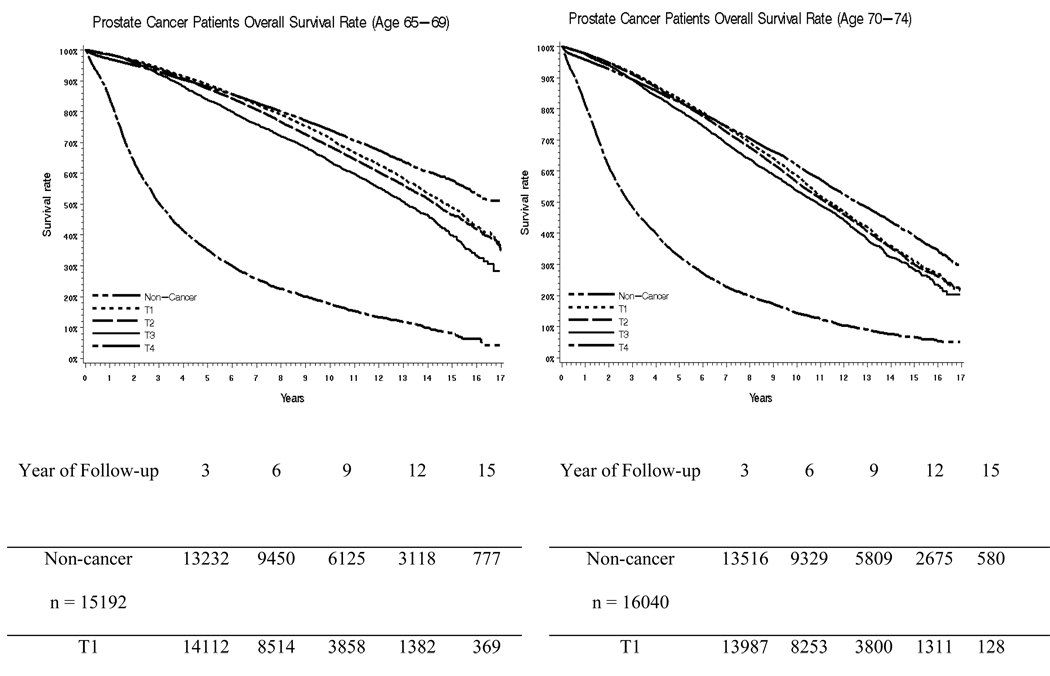

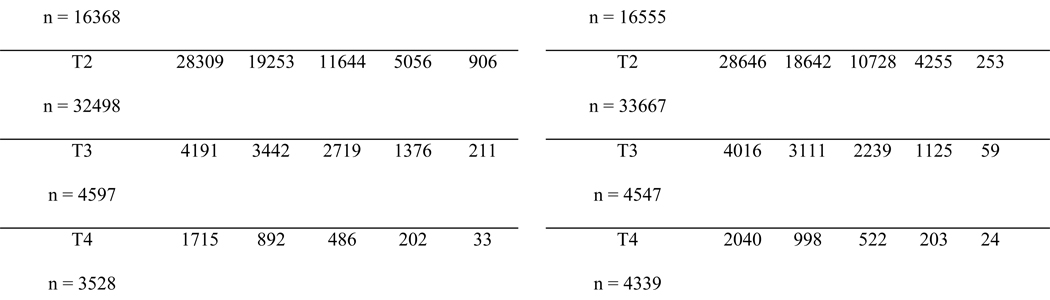

Figure 1a, 1b, 1c and 1d presents Kaplan Meier survival curves after a prostate cancer diagnosis for men aged 65–69,70–74,75–79 and 80–84, stratified by clinical stage. The cohort is split into four age groups in an attempt to take into account the impact of age. This was compared to age-matched men without cancer. For men aged 65–69 and 70–74, the survival of those with stage T1 or T2 tumors closely resembles the survival of patients without cancer for the first 7–8 years, and then becomes worse than the survival of men without cancer. For men aged 75–79 and 80–84, only stage T4 prostate cancers had a clear impact on survival rate. Men aged 75–79 and 80–84 with stage T1-T3 tumors had survival rates which closely overlapped each other and the non-cancer cohort.

Figure 1.

Survival Curves for Men Aged 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, and 80–84 for 17 Years of Follow Up

Table 2 presents the results of Cox proportional hazards survival analyses for men aged 66–84 with prostate cancer, and non cancer controls. Three models are presented. All models control for ethnicity, age, and comorbidity. Model 1 shows the impact of tumor stage on survival without considering tumor grade. Men with stage T1 cancer had a hazard of death similar to that of the non cancer cohort. Those diagnosed with stage T3 prostate cancer experienced a 44% increase in their hazard of death. In comparison, a prior diagnosis of diabetes was associated with a 47% increase in hazard of death. Model 2 examines the impact of histologic grade on survival, independent of tumor stage. Compared to non cancer controls, men with low to moderate grade tumors experienced a 5% increase in hazard of death, while high grade tumors were associated with a 71% increase in the hazard of death. When stage and grade were included in the same model, there was significant interaction, shown in Model 3. In general, histologic grade has a greater impact on survival than does stage at diagnosis.

Table 2.

Hazard of Death from Any Cause after a Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer in Men Age 66 to 84, Compared to Men without Prostate Cancer.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |||

| Age (each year increment) | 1.10 | (1.10, 1.10) | 1.10 | (1.10,1.10) | 1.10 | (1.09, 1.10) | ||

| Ethnicity | White | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Black | 1.26 | (1.23, 1.30) | 1.28 | (1.25,1.32) | 1.25 | (1.21, 1.28) | ||

| Hispanic | 0.87 | (0.82, 0.93) | 0.87 | (0.82, 0.93) | 0.87 | (0.82, 0.93) | ||

| Other/Unknown | 0.81 | (0.78, 0.84) | 0.82 | (0.79, 0.85) | 0.80 | (0.77, 0.83) | ||

| Men without cancer | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Prostate cancer stage: | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.01 | (0.98, 1.03) | ||||||

| 2 | 1.09 | (1.06, 1.11) | ||||||

| 3 | 1.28 | (1.23, 1.33) | ||||||

| 4 | 3.93 | (3.80, 4.06) | ||||||

| Unknown | 1.50 | (1.45, 1.55) | ||||||

| Grade | low/mod grade | 1.05 | (1.03, 1.07) | |||||

| poor/undef grade | 1.71 | (1.67, 1.76) | ||||||

| unknown grade | 1.70 | (1.65, 1.76) | ||||||

| Stage & Grade | ||||||||

| Stage 1 | low/mod grade | 0.96 | (0.93, 0.99) | |||||

| Stage 2 | low/mod grade | 0.99 | (0.97, 1.02) | |||||

| Stage 3 | low/mod grade | 1.07 | (1.01, 1.13) | |||||

| Stage 4 | low/mod grade | 2.71 | (2.57, 2.87) | |||||

| Stage 1 | poor/undef grade | 1.32 | (1.25, 1.40) | |||||

| Stage 2 | poor/undef grade | 1.41 | (1.36, 1.45) | |||||

| Stage 3 | poor/undef grade | 1.61 | (1.52, 1.71) | |||||

| Stage 4 | poor/undef grade | 4.73 | (4.53, 4.95) | |||||

| Comorbidity* | Heart attack | 1.09 | (1.03, 1.15) | 1.09 | (1.03, 1.15) | 1.09 | (1.03, 1.15) | |

| Congestive heart failure | 2.28 | (2.21, 2.36) | 2.28 | (2.21, 2.36) | 2.27 | (2.19, 2.34) | ||

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 1.47 | (1.40, 1.54) | 1.47 | (1.40, 1.54) | 1.47 | (1.40, 1.54) | ||

| Stroke | 1.50 | (1.45, 1.56) | 1.50 | (1.45, 1.56) | 1.51 | (1.45, 1.56) | ||

| COPD | 1.67 | (1.62, 1.71) | 1.65 | (1.60, 1.69) | 1.67 | (1.63, 1.72) | ||

| Diabetes | 1.47 | (1.43, 1.51) | 1.46 | (1.43, 1.50) | 1.47 | (1.43, 1.51) | ||

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table 3 shows the underlying cause of death in the five years after a diagnosis of prostate cancer, stratified by stage at diagnosis and histologic grade. Of the 103,086 men diagnosed with incident prostate cancer between 1992 and 1998, 26,740 died between 1992 and 2003. For all men diagnosed with prostate cancer, the 5 year mortality from prostate cancer, 7.73%, was similar to mortality from cardiovascular disease, 7.16%. Mortality from prostate cancer increased with tumor stage and grade. For men with stage T1 or T2, low or moderate grade tumors (59.1% of all cases), mortality from prostate cancer was 2.12%, versus a 6.40% mortality rate from heart disease and 3.83% mortality from other cancers. Even with stage T3 cancer, men with low or moderate grade tumors (comprising 60.5% of men with stage 3 cancer) experienced higher rates of death from cardiovascular disease (5.15%) than from prostate cancer (4.04%).

Table 3.

Underlying Cause of Death 5 Years after the Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer.

| All patients | T1/T2 Stage | T3 Stage | T4 Stage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| low or moderate grade | Poorly differentiated or undifferentiated | low or moderate grade | Poorly differentiated or undifferentiated | low or moderate grade | Poorly differentiated or undifferentiated | ||

| Percent of all patients | 100% | 59.1% | 13.3% | 4.2% | 2.7% | 2.4% | 3.3% |

| Overall 5 year mortality | 25.94% | 18.66% | 28.33% | 16.85% | 30.06% | 56.50% | 74.48% |

| Cause of death | |||||||

| Prostate Cancer | 7.73% | 2.12% | 9.78% | 4.04% | 13.59% | 35.19% | 54.24% |

| Other Cancers | 3.83% | 3.70% | 3.77% | 3.03% | 4.01% | 5.01% | 3.83% |

| Cardiovascular Disease | 7.16% | 6.40% | 7.26% | 5.15% | 6.53% | 7.75% | 8.53% |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 1.27% | 1.15% | 1.36% | 0.99% | 0.89% | 0.91% | 1.56% |

| Hypertension | 0.13% | 0.11% | 0.12% | 0.05% | 0.14% | 0.16% | 0.09% |

| COPD | 1.17% | 1.03% | 1.30% | 0.58% | 0.85% | 1.39% | 1.09% |

| Diabetes | 0.45% | 0.40% | 0.56% | 0.30% | 0.39% | 0.52% | 0.44% |

| Renal Disease | 0.19% | 0.16% | 0.21% | 0.25% | 0.14% | 0.20% | 0.12% |

| Liver Disease | 0.12% | 0.11% | 0.15% | 0.07% | 0.04% | 0.20% | 0.03% |

| Influenza/Pneumonia | 0.74% | 0.60% | 0.72% | 0.32% | 0.67% | 1.03% | 1.29% |

| Other Infections | 0.24% | 0.21% | 0.24% | 0.16% | 0.18% | 0.48% | 0.35% |

| Alzheimer's | 0.17% | 0.14% | 0.17% | 0.09% | 0.04% | 0.08% | 0.12% |

| Accident | 0.36% | 0.37% | 0.30% | 0.16% | 0.28% | 0.28% | 0.24% |

| Suicide | 0.16% | 0.13% | 0.20% | 0.16% | 0.35% | 0.28% | 0.24% |

DISCUSSION

We found that, for the two thirds of men who present with early stage prostate cancer, death from heart disease and from other cancers are more common than death from prostate cancer. Men with a diagnosis of early stage (T1 or T2), low or moderate grade prostate cancer do remarkably well compared to the general population without cancer, with a mortality risk comparable to men without cancer. Comorbid illnesses such as diabetes and congestive heart failure were important predictors of mortality in these men, and the major causes of death were cardiovascular disease and other cancers, also the two leading causes of death in men without prostate cancer [10,11].

Previous studies have shown that, over time, the proportion of men with prostate cancer who died from their cancer has steadily declined [12,13]. In our study, which encompassed men within the PSA screening era, nearly three quarters of prostate cancer patients presented with localized tumors, and overall less than one third of deaths at five years after diagnosis were due to prostate cancer. Prostate cancer was responsible for a majority of deaths only in men with stage T4 tumors, and comprised 45% of deaths in men diagnosed with stage T3, high grade tumors. Cardiovascular disease was an important cause of death for all men. Having a diagnosis of congestive heart failure carried a hazard of death substantially greater than that associated with a diagnosis of stage T3, high grade prostate cancer.

The substantial effect of comorbid conditions on survival and the high rate of non-prostate cancer related mortality have important implications. First, as others have suggested, decisions about management of localized prostate cancer should incorporate not only life expectancy based on age, but the important contribution of specific comorbid conditions [14,15]. Second, the choice to use androgen deprivation therapy, now a very common treatment for even for early stage prostate cancer [16], should be made carefully in the presence of significant comorbidity. Recent studies suggest that such therapy can increase the risk of cardiovascular events and exacerbate diabetes [17–19]. Furthermore, a post-hoc analysis of a clinical trial demonstrating overall survival benefit for adjuvant androgen deprivation together with radiation showed a trend for higher mortality in the androgen deprivation arm in men who had moderate to severe pre-existing comorbidity [20]. Finally, a shared model of care, where patients are followed both by a cancer specialist and a primary care physician, may be most appropriate for older men diagnosed with prostate cancer.

A cancer diagnosis can dominate the medical dialogue, such that other important health problems are ignored. For example, Earle et al. reported that colorectal cancer survivors received suboptimal care for chronic conditions as compared to a population without cancer [21]. On the other hand, this same group of investigators found that breast cancer survivors tended to receive more preventive services than did women without cancer [22]. Of note, patients followed by both an oncologist and a primary care physician received the highest proportion of recommended care. Thus, urologists treating and managing men with prostate cancer should clearly define their role in the patient’s management and stress the importance of primary care visits to manage existing chronic conditions.

This study has a number of limitations. First, the study was restricted to men aged 65 years and older. The impact of a diagnosis of prostate cancer on overall survival may very well be different in younger men, where competing risks for death from other causes would be lower [23]. This would especially be the case for younger African American men, who are at risk for a more aggressive form of prostate cancer [24]. On the other hand, nearly three quarters of men with prostate cancer are aged 65 and older at the time of diagnosis, so these results are relevant to the majority of patients with the disease. Also, we specifically stratified some analyses into cohorts with men aged 65–69, 70–74, 75–79 and 80–84 years, and found that early stage prostate cancer had a relatively small impact on survival in all groups (see Figure 1).

A second limitation of this study is the use of clinical stage instead of American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging. Clinical staging does not take into consideration tumor histology, which is why we included it in the models. The accuracy of the underlying cause of death from death certificates is another limitation to the validity of disease specific mortality rates. However, Penson et al. [25] showed that there was a good correlation between cause of death obtained from death certificates and medical records in prostate cancer patients. Finally, we did not consider type of treatment in our analyses. This is because studies have shown survival to be good with early stage prostate cancer regardless of treatment [26]. In addition, strong selection biases linked to treatment decisions would render interpretation of the relationship of treatments to outcomes highly problematic in observational studies [27].

In conclusion, the diagnosis of localized, or low to moderate grade prostate cancer has a relatively small impact on life expectancy. Cardiovascular and other diseases are the major threat to life in these cases. For older men with prostate cancer, a focus on prevention and management of comorbid health conditions is an important aspect of their health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper.

Grant Support: 5P50CA105631, 5P30AG024824 and 5R01CA116758 from the US Public Health Service. Ms. Ketchandji, a third year medical student, was supported by a T-35 training grant (5T35AG026778) from the NIA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: This study used the linked SEER-Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, National Cancer Institute; the Office of Research, Development and Information, Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Information Management Services Inc.; and the SEER Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carver JR, Shapiro CL, Ng A, et al. Review on the Ongoing Care of Adult Cancer Survivors: Cardiac and Pulmonary Late Effects. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3991–4008. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.9777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleming ST, Pearce KA, McDavid K, et al. The development and validation of a comorbidity index for prostate cancer among black men. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:1064–1075. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00213-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babb P, Quinn M. Patterns and trends in prostate cancer incidence, survival, prevalence and mortality. BJU Int. 2002;90:174–184. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.02823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Potosky AL, Merill RM, Riley GF, et al. Prostate Cancer Treatment and Ten-Year Survival Among Group/Staff HMO and Fee-for-Service Medicare Patients. Health Serv Res. 1999;34:1683–1691. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson D, Aus G, Bak J, et al. Long-term follow-up of conservatively managed incidental carcinoma of the prostate: A multivariate analysis of prognostic factors. Scand J Urol and Nephrol. 2007;41:103–109. doi: 10.1080/00365590600991268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong YN, Mitra N, Hudes G, et al. Survival Associated with Treatment vs Observation of Localized Prostate Cancer in Elderly Men. JAMA. 2006;296:2683–2693. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.22.2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potosky AL, Riley GF, Lubitz JD, et al. Potential for Cancer Health Services Research Using a Linked Medicare-Tumor Registry Database. Med Care. 1993;31:732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sox HC, Mulrow C. An editorial update: Should benefits of radical prostatectomy affect the decision to screen for early prostate cancer? Ann Int Med. 2005;143:232–233. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-3-200508020-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, et al. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1258–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Satariano WA, Ragland KE, Van Den Eden SK. Cause of death in men diagnosed with prostate cancinoma. Cancer. 1998;83:1179–1184. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980915)83:6<1180::aid-cncr18>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deaths: Leading causes for 2004. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2007 Nov 20;56:1–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newschaffer CJ, Otani K, McDonald MK, et al. Causes of death in elderly prostate cancer patients and in a comparison nonprostate cancer cohort. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:613–621. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.8.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu-Yao G, Stukel TA, Yao SL. Changing Patterns in Competing Causes of Death in Men with Prostate Cancer: A Population Based Study. J Urol. 2004;171:2285–2290. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000127740.96006.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzpatrick JM. Management of localized prostate cancer in senior adults: The crucial role of comorbidity. BJU Int. 2008;101(Suppl 2):16–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tewari A, Johnson CC, Divine G, et al. Long-term survival probability in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: A case-control, propensity modeling study stratified by race, age, treatment and comorbidities. J Urol. 2004;171:1513–1519. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000117975.40782.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shahinian VB, Kuo YF, Freeman JL, et al. Increasing use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists for the treatment of localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103:1615–1624. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'Amico AV, Denham JW, Crook J, et al. Influence of androgen suppression therapy for prostate cancer on the frequency and timing of fatal myocardial infarctions. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2420–2425. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.3369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keating NL, O'Malley AJ, Smith MR. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease during androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4448–4456. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haidar A, Yassin A, Saad F, et al. Effects of androgen deprivation on glycaemic control and on cardiovascular biochemical risk factors in men with advanced prostate cancer with diabetes. Aging Male. 2007;10:189–196. doi: 10.1080/13685530701653538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D'Amico AV, Chen MH, Renshaw AA, et al. Androgen suppression and radiation vs radiation alone for prostate cancer: A randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;299:289–295. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Earle C, Neville B. Under Use of Necessary Care among Cancer Survivors. Cancer. 2004;101:1712–1719. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Earle CC, Burstein EP, et al. Quality of non-breast cancer health maintenance among elderly breast Cancer Survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1447–1451. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Welch HG, Albertsen PC, Nease RF, et al. Estimating treatment benefits for the elderly: The effect of competing risks. Ann Int Med. 1996;124:577–584. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-6-199603150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jemal A, Clegg LX, Ward E, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2001, with a special feature regarding survival. Cancer. 2004;101:3–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Penson D, Albertsen PC, Nelson PS, et al. Determining Cause of Death in Prostate Cancer: Are Death Certificates Valid? J Nat Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1822–1823. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.23.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albertsen PC, Hanley JA, Fine J. 20-Year Outcomes Following Conservative Management of Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer. JAMA. 2005;293:2095–2101. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.17.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Girodano SH, Kuo YF, Duan Z, et al. Limits of observational data in determining outcomes from cancer therapy. Cancer. 2008;112:2456–2466. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]