Abstract

Objective: to determine the clinical effectiveness of a day hospital-delivered multifactorial falls prevention programme, for community-dwelling older people at high risk of future falls identified through a screening process.

Design: multicentre randomised controlled trial.

Setting: eight general practices and three day hospitals based in the East Midlands, UK.

Participants: three hundred and sixty-four participants, mean age 79 years, with a median of three falls risk factors per person at baseline.

Interventions: a day hospital-delivered multifactorial falls prevention programme, consisting of strength and balance training, a medical review and a home hazards assessment.

Main outcome measure: rate of falls over 12 months of follow-up, recorded using self-completed monthly diaries.

Results: one hundred and seventy-two participants in each arm contributed to the primary outcome analysis. The overall falls rate during follow-up was 1.7 falls per person-year in the intervention arm compared with 2.0 falls per person-year in the control arm. The stratum-adjusted incidence rate ratio was 0.86 (95% CI 0.73–1.01), P = 0.08, and 0.73 (95% CI 0.51–1.03), P = 0.07 when adjusted for baseline characteristics. There were no significant differences between the intervention and control arms in any secondary outcomes.

Conclusion: this trial did not conclusively demonstrate the benefit of a day hospital-delivered multifactorial falls prevention programme, in a population of older people identified as being at high risk of a future fall.

Keywords: accidental falls, screening, primary care, comprehensive geriatric assessment, randomised controlled trial, elderly

Introduction

Falls are a common, serious and costly problem. Single and multi-factorial interventions can reduce the rate of falls by around 25% in high risk populations [1–3]. In the UK, most falls prevention programmes are delivered in day or community hospitals [4], and referral to such programmes is usually opportunistic rather than through a systematic screening process. The aim of this trial was to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of a process of systematically screening community-dwelling older people, identifying those at high risk of falls and intervening with a day hospital-based falls prevention programme.

Methods

We used a multi-centre randomised controlled trial to test the hypothesis that a day hospital-based falls prevention programme would reduce the rate of falls over 12 months in community-dwelling older people, identified through a screening programme as being at high risk of falls.

Participants

Older people (aged 70+) were identified from eight general practices, reflecting both rural and urban settings in the East Midlands, UK. The practices sent a written invitation and falls risk screening questionnaire to people aged 70+. The questionnaire was a self-completed, modified version of the Falls Risk Assessment Tool [5, 6]. This consisted of eight self-reported items—one or more falls in the previous year, taking more than four prescribed medications, previous stroke, Parkinson's disease, inability to stand from a chair without using arms to push up, symptoms of dizziness on standing, use of a mobility aid and being house-bound. A previous fall or two or more of the other falls risk factors were used to identify those at high risk of a future fall, and so eligible for inclusion in this trial. Potential participants were excluded by their general practitioner if they

lived in a care home

were in receipt of end of life care

or by researchers if they

were already attending a falls prevention programme

were unwilling or unable to attend a falls prevention programme

were unable to provide informed consent or assent

had interventions

Eligible participants in both arms received a falls prevention information leaflet (‘Avoiding slips, trips and broken hips’ [7]). No further intervention was offered to participants in the control arm, who had access to all usual services, including referral to a community or hospital-based falls prevention programme if indicated.

Participants in the intervention arm were invited to attend a falls prevention programme based in a geriatric day hospital closest to their home. The falls prevention programme consisted of a medical review, physiotherapy and occupational therapy treatments. The falls prevention programme was that used in routine local clinical practice and no additional resources or interventions beyond routine clinical practice were employed in the intervention arm. In all three settings, the medical assessment was carried out by, or under the direction of, a consultant geriatrician. It included a clinical history, physical examination including an orthostatic blood pressure measurement, laboratory tests where indicated, 12-lead ECG and where appropriate a neurovascular assessment. Medical interventions varied according to medical diagnoses made and could include a medication review, bone health assessment, referral to an optician or ophthalmologist or to other specialists. The physiotherapy assessment included assessment of gait, balance, mobility and muscle strength, and the intervention included provision of strength and balance training, tailored to individuals’ needs. The occupational therapy assessment included an interview to investigate home hazards and, when required, a home assessment was also performed. Occupational therapy interventions could include the provision of assistive technology and home adaptations. Finally, participants received a nursing review and an educational programme focusing on healthy ageing.

Compliance with the intervention was assessed using logs completed by health-care professionals working in the falls prevention programme who recorded the nature of interventions and the amount of time spent with each participant, as well as the number of attendances.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the rate of falls over 12 months, ascertained using prospective, participant-completed monthly falls diaries, mailed to the research team at the end of every month. The definition of a fall was ‘unintentionally coming to rest on the ground, floor or other lower level; excluding coming to rest against furniture, wall, or other structure’ [8].

Secondary outcomes included mortality and institutionalisation (ascertained from primary care records), the proportion of people reporting single or recurrent falls, self-reported injurious falls and time to first fall within 12 months. Additional secondary outcomes were fear of falling (Falls Efficacy Scale [9]) and disability (Barthel [10] and Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living [11] scales) which were collected using a questionnaire sent to participants at 12 months post-randomisation.

Sample size

The sample size estimate was based on an expected rate of two falls per person per year [12] in the control arm and a clinically important rate reduction of 25% to 1.5 falls per year, with a two-sided 5% significance level and power of 80%. Using an over-dispersion parameter of 1.5, 160 participants were needed in each arm, giving a trial size of 320. Allowing for an attrition rate of 20%, it was planned to recruit a total of 400 participants.

Randomisation

After obtaining written informed consent and collecting baseline data, participants were allocated into the intervention or control arm by research assistants using an internet-based randomisation service provided by the Nottingham Clinical Trials Unit. The randomisation list was computer generated using a random block size to maximise allocation concealment and was stratified by centre (Nottingham and Derby).

Blinding

Owing to the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to blind participants or researchers to allocation, but all analyses were performed blind to allocation.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was carried out according to a pre-specified plan using the intention-to-treat principle. Participants were analysed in the arm they were allocated to regardless of the intervention they actually received. The primary outcome (rate of falls) was compared between arms using negative binomial regression. Patients were included, assuming each completed diary covered 30 days, until they died, were admitted to a care home, withdrew from the trial or reached the end of the 12 months follow-up. The main analysis was adjusted for stratum (trial centre) and also for baseline characteristics considered to be strong prognostic factors for falls (age, sex and the screening items) [13–15]. Pre-specified subgroup analyses were carried out by age (70–85, 85+) and falls history in the year prior to randomisation (fall/no fall) using tests for interaction.

Time to first fall was analysed with a Cox proportional hazards model, and logistic regression was used to analyse mortality and institutionalisation within 12 months and the proportions of people reporting single or recurrent falls and injurious falls. The Barthel ADL, NEADL scale, fear of falling scale was compared between treatment arms using linear regression or logistic regression categorising the outcome at the median if the assumptions of linear regression were not met and adjusting for stratum and baseline characteristics. For the Falls Efficacy Scale, Barthel and NEADL scales, an additional sensitivity analysis was undertaken to explore the effect of missing data. We used multiple imputation to impute missing values for these outcomes, including all baseline variables, and imputed 10 data sets. We then combined the results using Rubin's rules [16]. Models were checked by examining residual plots.

Results

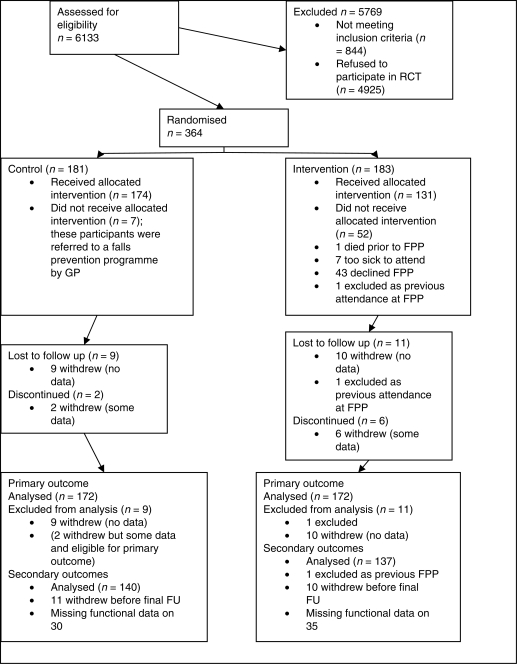

The trial started in February 2005 and the last follow-up was completed in March 2008. Of the 6133 individuals aged 70+, 844 were excluded by their GP prior to invitation to the trial; 2846/5289 (54%) responded to the postal invitation, 1481/2846 (52%) of whom were at high risk of falls; 364/1481 (25%) agreed to participate in the trial; 181 were randomised into the control arm and 183 into the intervention arm (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through the trial. FPP, falls prevention programme.

The baseline characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. There was evidence of some imbalance between treatment arms with intervention arm participants having a higher percentage of seven of the eight risk factors for falls than control arm participants.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants

| Characteristic | Control, n = 181 | Intervention, n = 183 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Centre/stratum | Nottingham | 120 (66%) | 121 (66%) |

| Derby | 61 (34%) | 62 (34%) | |

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 78.4 (5.6) | 79.1 (5.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 77.6 (73.5–82.9) | 78.3 (75.0–82.9) | |

| Range | 70–92 | 70–101 | |

| Female | Frequency (%) | 112 (62%) | 106 (58%) |

| At least one fall in previous 12 months | Frequency (%) | 102 (56%) | 108 (59%) |

| Taking more than four medications | Frequency (%) | 89 (49%) | 103 (56%) |

| History of stroke | Frequency (%) | 20 (11%) | 33 (18%) |

| Parkinson's disease | Frequency (%) | 2 (1%) | 4 (2%) |

| Inability to stand from a chair without using arms to push up | Frequency (%) | 115 (64%) | 125 (68%) |

| Symptoms of dizziness on standing | Frequency (%) | 115 (64%) | 103 (56%) |

| Use of a mobility aid | Frequency (%) | 86 (48%) | 96 (52%) |

| Housebound/not housebound (mobility impairment) | Frequency (%) | 39 (22%) | 44 (24%) |

Only 72% (131/183) of the intervention arm participants received the falls prevention programme, with only 68 (37%) attending six or more falls prevention programme sessions. Attendees received a median 60 (IQR 45–90) min of occupational therapy and 210 (IQR 60–362.5)-min physiotherapy in addition to a medical and nursing review.

One hundred and seventy-two participants in each arm completed at least one fall diary and so were eligible for the analysis of the primary outcome. There were 417 falls in 156.7 person-years (2.7 falls per person-year) in the control arm compared with 260 falls in 151.2 person-years (1.7 falls per person-year) in the intervention arm. The incidence rate ratio (IRR) adjusted for stratum was 0.64 (95% CI 0.43–0.95), P = 0.03. Model checking identified an extreme outlier in the control arm who had 107 falls over 11 months of follow-up. Sensitivity analyses indicated that results were not robust to excluding this participant as the control arm falls rate reduced to 2.0 per person-year and the difference in falls rates between the treatment arms no longer remained significant, with a stratum-adjusted IRR of 0.86 (95% CI 0.73–1.01, P = 0.08) and a baseline characteristics-adjusted IRR of 0.73 (95% CI 0.51–1.03, P = 0.07).

Pre-planned subgroup analyses did not show any significant differential effects by age or history of the previous fall. There were no significant differences between the treatment arms in any of the secondary outcomes (Table 2 and Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online).

Table 2.

Secondary outcomes for falls, institutionalisation and mortality, by treatment arm

| Secondary outcome measure | Control arm | Intervention arm | Effect size, adjusted for stratum (95% CI) | Effect size, adjusted for stratum and baseline characteristics (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion falling over 12 months (OR) | 73/138 (53%) | 69/136 (51%) | 0.9 (0.6–1.5), P = 0.67 | 0.9 (0.5–1.5), P = 0.73 |

| Proportion with two or more falls (OR) | 38/138 (28%) | 38/136 (28%) | 1.0 (0.6–1.7), P = 0.97 | 1.0 (0.5–1.8), P = 0.93 |

| Proportion with self-reported injurious falls (OR) | 55/138 (40%) | 56/136 (41%) | 1.1 (0.6–1.7), P = 0.86 | 1.1 (0.6–1.8), P = 0.78 |

| Time to first fall (HR) | 271 days (median) | 292 days (median) | 0.9 (0.7–1.3), P = 0.63 | 0.9 (0.7–1.3), P = 0.62 |

| Proportion institutionalised at 12 months (OR) | 1/170 (<1%) | 3/166 (2%) | 3.1 (0.3–30.2), P = 0.33 | 4.8 (0.3–73.1), P = 0.26 |

| Mortality at 12 months (OR) | 9/181 (5%) | 9/182 (5%) | 1.0 (0.4–2.6), P = 0.99 | 0.8 (0.3–2.4), P = 0.71 |

OR, odds ratio from logistic regression; HR, hazards ratio from Cox proportional hazards regression.

Discussion

In this study, we screened older people for the risk of falling and invited those at higher risk to enter a trial of a day hospital-based falls prevention programme. Only 25% of those invited agreed to take part. We observed a 27% reduction in the rate of falling in the intervention arm compared with the control arm, a difference which was no larger than could have occurred by chance. There were no significant differences in the proportion of fallers, recurrent fallers, injurious falls, time to first fall, institutionalisation, mortality, basic or extended activities of daily living or fear of falling.

Despite the lack of statistical significance, the reduction in the rate of falls was consistent with that seen in previous falls prevention trials [2, 3, 17–19], and compatible with the results of a meta-analysis which estimated that falls prevention services reduce falls by 9% (OR 0.9; 95% confidence interval 0.8 to 1.0) [20].

The UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance on falls prevention advises that clinicians should routinely ask about falls in the last year, but does not recommend actively screening patients for falls risk. In isolation, our results do not conclusively demonstrate the benefit of day hospital-based falls prevention programmes for a screened population of older people identified as being at high risk of a future fall. On the other hand, they do not exclude the possibility of a clinically important reduction in falls in this group and should not be interpreted as showing that day hospital falls prevention programmes, or that screening as a means of identifying patients for intervention programmes, are not effective in reducing falls.

The falls rate in the control arm of this trial shows that participants were at higher risk of falls than the general population (53% fell over a year, with a mean of 2.7 falls per person-year), and hence the screening process achieved its intended function. Even among this high-risk group, the participation rate was low. However, recruitment to a trial where consent, randomisation and outcome assessment are required may not reflect the uptake of a service in usual clinical practice, and it is possible that uptake of day hospital falls prevention programmes would be higher following professional advice in a service setting.

Some participants did not complete all falls diaries, so this trial was underpowered to detect a 25% reduction in falls rate in terms of the number of person-years of follow-up. We had insufficient power in our study to detect smaller rate reductions, such as a reduction of 10%. We chose a 25% reduction in the rate of falling as being clinically important for determining sample size, and a Cochrane meta-analysis for multifactorial interventions in older people living in the community found this reduction in rate of falls (rate ratio 0.75, 95% CI 0.65–0.86) based on 8141 participants from 15 trials [8] but they did not find a significant reduction in risk of falling (relative risk 0.95, 95% CI 0.88–1.02). Similarly, another meta-analysis of multifactorial assessment and intervention programmes to prevent falls and injuries among older adults reported a relative risk of 0.91 (95% confidence interval 0.82–1.02) [20].

The intensity of the intervention may have affected the ability of our trial to demonstrate a reduction in the rate of falls. The falls prevention programme was intended to comprise six or more sessions, reflecting routine practice in these day hospitals and similar to that reported elsewhere in England and Wales [4]. Only 37% of participants attended this many sessions. Median time spent on strength and balance training was 210 min per participant (excluding self-directed exercises done between sessions or after the programme finished). Other research suggests that the optimum amount of exercise is much greater than this, in the region of 50 h of strength and balance training. It is possible that community-based falls prevention programmes may have better compliance than the day hospital-based intervention used in this trial, and hence greater effectiveness [21]. Other approaches may improve uptake by emphasising the positive aspects of falls prevention services such as healthy ageing and improving the quality of life [22, 23].

Bias could have been introduced by the use of self-reported falls as the primary outcome, although this is the standard practice in falls research. Another potential problem could have arisen from missing data on secondary outcomes, but we included a sensitivity analysis using imputation to investigate this. It is also possible that a participation bias occurred whereby those who were less fit, and who may conceivably have benefited most, did not participate because of the need for travel to the day hospital.

The main strengths of this study are that as a randomised controlled trial, it would have been relatively little prone to bias. The broad inclusion criteria, use of a simple screening tool and use of existing NHS services as the intervention make our findings highly generalisable and applicable to clinical service provision.

The addition of our findings to recent meta-analysis of falls prevention programmes [1] will further strengthen the evidence in their favour. The question of the setting of the intervention requires further research. Similarly, the value for money of screening and the provision of the day hospital intervention needs estimating. Future falls prevention studies should take particular care to optimise intervention intensity and compliance.

Key points.

Screening and intervening for falls using a day hospital-based falls prevention programme is feasible, though participation and compliance are poor.

The benefit is similar to other falls prevention programmes, but this study did not conclusively show that screening and intervening using a day hospital-based falls prevention programme is effective.

Further work on optimising compliance or assessing alternative forms of falls prevention programmes is required, along with an assessment of the economic impact of such an approach.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data mentioned in the text is available to subscribers in Age and Ageing online.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub2. CD007146; doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell AJ, Robertson MC. Rethinking individual and community fall prevention strategies: a meta-regression comparing single and multifactorial interventions. Age Ageing. 2007;36:656–62. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm122. doi:10.1093/ageing/afm122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute of Clinical Excellence. Falls: The Assessment and Prevention of Falls in Older People. NICE, London; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamb S, Gates S, Fisher J, Cooke M, Carter Y, McCabe C. Scoping Exercise on Fallers’ Clinics: National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R & D (NCCSDO). 2007.

- 5.Nandy S, Parsons S, Cryer C, Underwood M. Development and preliminary examination of the predictive validity of the Falls Risk Assessment Tool (FRAT) for use in primary care. J Public Health. 2004;26:138–43. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdh132. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdh132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conroy S. Preventing Falls in Older People. Nottingham: University of Nottingham; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Department of Trade and Industry. Avoiding Slips, Trips and Broken Hips. HMSO, London; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillespie LD, Gillespie WJ, Robertson MC, Lamb SE, Cumming RG, Rowe BH. Interventions for preventing falls in elderly people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003. p. CD000340. [see comment; update of Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001; 3: CD000340; PMID: 11686957] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Parry SW, Steen N, Galloway SR, Kenny RA, Bond J. Falls and confidence related quality of life outcome measures in an older British cohort. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2001;77:103–8. doi: 10.1136/pmj.77.904.103. doi:10.1136/pmj.77.904.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wade D, Collin C. The Barthel ADL index: a standard measure of physical disability? Int Dis Stud. 1988;10:64–7. doi: 10.3109/09638288809164105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lincoln N, Gladman J. The extended activities of daily living scale: a further validation. Disabil Rehabil. 1992:41–3. doi: 10.3109/09638289209166426. doi:10.3109/09638289209166426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Close J, Ellis M, Hooper R, Glucksman E, Jackson S, Swift C. Prevention of falls in the elderly trial (PROFET): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 1999;353:93–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06119-4. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts C, Torgerson DJ. Understanding controlled trials: Baseline imbalance in randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 1999;319:185. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7203.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Senn SJ. Covariate imbalance and random allocation in clinical trials. Stat Med. 1989:467–75. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080410. doi:10.1002/sim.4780080410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products—Evaluation of Medicines for Human Use. London: 2003. Points to consider on adjustment for baseline covariates. Report No. CPMP/EWP/2863/99, [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubin D. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: J. Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreland J, Richardson J, Chan DH, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for the secondary prevention of falls in older adults. Gerontology. 2003;49:93–116. doi: 10.1159/000067948. doi:10.1159/000067948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clemson L, Cumming RG, Kendig H, Swann M, Heard R, Taylor K. The effectiveness of a community-based program for reducing the incidence of falls in the elderly: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1487–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52411.x. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weatherall M. Prevention of falls and fall-related fractures in community-dwelling older adults: a meta-analysis of estimates of effectiveness based on recent guidelines. Intern Med J. 2004;34:102–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0903.2004.t01-15-.x. doi:10.1111/j.1444-0903.2004.t01-15-.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gates S, Fisher JD, Cooke MW, Carter YH, Lamb SE. Multifactorial assessment and targeted intervention for preventing falls and injuries among older people in community and emergency care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336:130–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39412.525243.BE. doi:10.1136/bmj.39412.525243.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Layne JE, Sampson SE, Mallio CJ, et al. Successful dissemination of a community-based strength training program for older adults by peer and professional leaders: the people exercising program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:2323–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02010.x. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yardley L, Todd C. Encouraging positive attitudes to falls prevention in later life. London: Help the Aged; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horne M, Speed S, Skelton D, Todd C. What do community-dwelling Caucasian and South Asian 60-70 year olds think about exercise for fall prevention? Age Ageing. 2009;38:68–73. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn237. doi:10.1093/ageing/afn237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.