Abstract

Background: multifactorial falls prevention programmes for older people have been proved to reduce falls. However, evidence of their cost-effectiveness is mixed.

Design: economic evaluation alongside pragmatic randomised controlled trial.

Intervention: randomised trial of 364 people aged ≥70, living in the community, recruited via GP and identified as high risk of falling. Both arms received a falls prevention information leaflet. The intervention arm were also offered a (day hospital) multidisciplinary falls prevention programme, including physiotherapy, occupational therapy, nurse, medical review and referral to other specialists.

Measurements: self-reported falls, as collected in 12 monthly diaries. Levels of health resource use associated with the falls prevention programme, screening (both attributed to intervention arm only) and other health-care contacts were monitored. Mean NHS costs and falls per person per year were estimated for both arms, along with the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) and cost effectiveness acceptability curve.

Results: in the base-case analysis, the mean falls programme cost was £349 per person. This, coupled with higher screening and other health-care costs, resulted in a mean incremental cost of £578 for the intervention arm. The mean falls rate was lower in the intervention arm (2.07 per person/year), compared with the control arm (2.24). The estimated ICER was £3,320 per fall averted.

Conclusions: the estimated ICER was £3,320 per fall averted. Future research should focus on adherence to the intervention and an assessment of impact on quality of life.

Keywords: cost-effectiveness, accidental falls, screening, comprehensive geriatric assessment, randomised controlled trial, elderly

Background

Falls are a common and serious problem for older people. Multifactorial falls prevention programmes reduce the rate of falls in people presenting to health services with a fall [1]. However, the incidence of falls is sufficiently high and the risk factors for falls are sufficiently well known, for it to be feasible for falls programmes to be delivered to those identified through screening. In an accompanying paper, we tested such an approach in a multicentre randomised controlled trial of people found through screening to be at high risk of falls, which compared falls prevention delivered in a day hospital with routine primary care. We found that there was a non-statistically significant reduction in the rate of falls in the treatment arm. We argued that, when seen in the context of other positive trials of falls prevention, our trial showed that the provision of falls prevention to people identified by screening was plausible and could well be clinically effective. Evidence of the cost implications and cost-effectiveness of such programmes is mixed [2]. The aim of the present report is to provide a cost-effectiveness analysis of this approach.

Methods

The economic evaluation was conducted alongside a pragmatic randomised controlled trial (described elsewhere [3]) using cost and outcome data on individual patients.

Participants

Participants were community-dwelling older people (aged 70 and over), recruited from eight general practices in the East Midlands, United Kingdom. Potentially eligible participants were identified from a search of computerised general practice records and were sent a written invitation to participate in the study, which included a falls risk questionnaire. The risk questionnaire was a self-completed, modified version of the Falls Risk Assessment Tool [4]. Potential participants were excluded if they lived in a care home, were in receipt of end-of-life care, had already attended a falls prevention programme, were unwilling or unable to attend a falls prevention programme or were unable to provide consent. Consenting participants were allocated into the intervention or control arm by research assistants, using an internet-based randomisation service provided by the host institution's Clinical Trials Unit.

Intervention

Both arms received a falls prevention information leaflet (‘Avoiding Slips, Trips and Broken Hips’ [5]). No further intervention was offered to participants in the control arm, who had access to all usual services, including referral to a community or hospital-based falls prevention programme. The intervention, undertaken at 3-day hospitals in Leicester and Nottingham, was based on standard falls prevention programme, similar to many falls prevention programmes offered in similar settings throughout England and Wales [2]. The programme was tailored to individual needs, incorporating a medical assessment, strength and balance training, a home hazards assessment and referral to other specialists as necessary.

The primary outcome measure was the rate of self-reported falls per year, collected over 12 months using monthly diaries. Trial completion was defined as 360 days of follow-up from randomisation, time to institutionalisation or death. The trial started in February 2005 and the last follow-up was completed in March 2008.

Measuring costs

In line with NICE guidance [6], the economic evaluation was conducted from the viewpoint of the NHS and personal social services (PSS), focusing on costs to the health service.

Costs of screening and recruitment to the trial were collected using a top-down approach. One research secretary (1.0 full time equivalent) and one research associate (0.5 full time equivalent) were employed exclusively for screening, which took place over 20 months. Printing, postage and associated consumable costs were recorded. Research costs, including telephone contact by the study team to gain informed consent, were excluded. The total cost of screening was calculated, along with cost per recruited participant. In analysis, this was apportioned to participants in the intervention arm only.

Levels of resource use associated with the falls prevention programme were collected prospectively by day hospital staff, using a questionnaire to record the time spent by clinicians, nurses and allied health professionals at each attendance. Where these values were missing, we imputed the average from all other respondents. Information on referrals to other medical specialists and investigations ordered (e.g. blood tests, cardiology investigations, bone density scans) were also collected.

In line with guidance by the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) [6], we also collected resource use information on items that we considered could potentially relate to the intervention in question (this assesses the possibility that provision of falls programme averts costs that would otherwise have been incurred). Consequently, participants were also asked to complete questionnaires on health service resource use, including the frequency and duration of visits with health-care professionals, including primary care and details about the specific type of service used (e.g. outpatient, emergency). All self-reported health-care resource use was cross-referenced to hospital and primary-care records and unit costs ascribed, resulting in health service resource use data over the full 12-month study period.

Unit costs are presented in pounds sterling from the baseline year 2007–8 (PSSRU [7] and NHS Reference costs [8]; Supplementary data are available in Age and Ageing online). Neither health-care costs nor effects were discounted, as the study period did not exceed 1 year.

Measuring outcomes

The primary outcome measure was rate of falls per year, so the primary economic outcome was cost per fall averted. Last observation carried forward method [9] was used to impute missing monthly falls data.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

Cost-effectiveness of the falls prevention programme was calculated by estimating the incremental cost per fall averted [incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER)], relative to usual care. T-tests were used to test for incremental costs of the intervention compared with control, presenting results as arithmetic means and standard deviations.

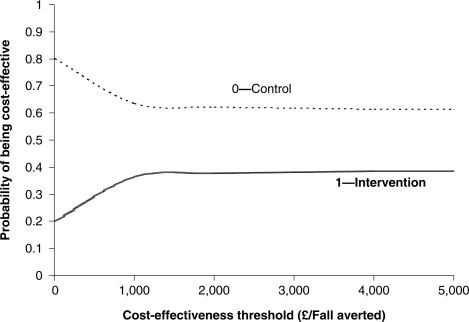

Uncertainty analysis

In order to estimate the level of uncertainty associated with the decision as to which intervention was most cost-effective, probabilistic methods were used to estimate the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC) for each intervention arm. The CEAC depicts the probability that an intervention is cost-effective at different levels of the cost-effectiveness threshold (in this case, how the probability of cost-effectiveness varies according to how much one is willing to pay to avert one fall) [10]. Bootstrapping methods were applied, which build up an empirical estimate of the sampling distribution of the statistic in question by re-sampling from the original data (in this case, 10,000 iterations).

Sensitivity analysis was used to assess the robustness of conclusions to key assumptions [11]. To investigate the effect of loss to follow-up, we examined cost-effectiveness using complete case data only. A sensitivity analysis was also performed eliminating extreme outlier values.

Results

Participants

There were 6,133 individuals aged over 70 registered with the eight participating general practices, 844 of whom were deemed unsuitable by their GP prior to invitation to the trial. The remaining 5,289 were invited to participate and 2846 (54%) responded. Of those who responded, 1481(52%) were deemed to be at high risk of falls and 364 (25%) agreed to participate in the trial. One hundred and eighty-one were randomised into the control arm and 183 into the intervention arm. Thus, 364/6133 (6%) of all people screened took up the offer of a trial of falls prevention.

One participant in the intervention arm had attended a falls prevention programme elsewhere in the year prior to randomisation and was subsequently excluded. There were 9 withdrawals in the control arm and 10 in the intervention arm, who provided no falls outcome data, so analyses were based on 172 participants in each arm.

The baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online. The two study arms were well balanced with respect to most characteristics, including age, previous falls history and aggregated falls risk.

Falls rates

There were 260 self-reported falls in the intervention arm and 417 falls among control participants. From 4140 available months (88.0% completion), 3644 falls diaries were returned. After imputing missing falls data (this was necessary for 91 participants: 47 intervention; 44 control), falls rates (per person-year) were 2.07 in intervention arm and 2.85 among controls.

One participant in the control arm reported 107 non-injurious falls over 11 months and was considered an extreme outlier. Although intention-to-treat analysis favours inclusion of all participants irrespective of exceptional circumstances experienced, this participant significantly distorted the level of falls averted between intervention and control arms. For this reason, analysis was performed with and without the outlier's cost and falls data, but base-case results were reported without this participant. Excluding this participant reduced the falls rate in the control arm to 2.24 per person-year. We found no significant differences between the arms in terms of rate of falls or injuries (Supplementary data are available in Age and Ageing online).

Costs

Falls Prevention Programme costs

Screening costs were substantial, estimated at £59,900 or £165 per participant eventually recruited into the study (Supplementary data are available in Age and Ageing online). In the analysis, this was apportioned to the intervention arm only. The cost of the falls prevention programme varied between subjects, reflecting the variability of attendance. The mean number of sessions was 2.2 (range 0–21), the average unit cost per session was £76.33 (range £3.35–469.36), and the average overall falls prevention programme cost per participant was £349.03 (Table 1). The level of missing data with regard to reported staff time associated with each session ranged from 21 to 24% in day hospital log sheets (data with regard to the number of sessions was completed for all participants). This was subsequently imputed using the mean visit time for all other participants with complete data.

Table 1.

Incremental costs of falls prevention programme

| Cost item | Number participants using resource at least once (% of 172 intervention participants) | Resource use for the intervention arm | Total cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical consultation (full clinical history and physical examination and referrals where appropriate) | 118 (68.6%) | 158 | £21,962 |

| Physiotherapy review (average 45 min) | 125 (72.7%) | 627 | £17,870 |

| Nurse review (average 28 min) | 124 (72.1%) | 535 | £9,987 |

| Occupational Therapy review (average 41 min) | 70 (40.7%) | 129 | £3,614 |

| Occupational therapy home visit | 12 (7.0%) | 13 | £507 |

| Falls-related diagnostic tests (including cardiac tests, blood tests, tilt test) | 80 (46.5%) | 170 | £3,198 |

| Other specialty consultation (e.g. dietician, continence clinic, orthotics) | 18 (10.5%) | 25 | £1,374 |

| Other investigations (e.g. DEXA scan, radiology) | 10 (5.8%) | 10 | £1,104 |

| Home modifications | 11 (6.4%) | 11 | £417 |

| Total cost of implementation | £60,033 | ||

| Average number of Falls sessions attended per participant (range) | 2.2 (0–21) | ||

| Average cost per falls session attended (range) | £76 (£3–469) | ||

| Average cost per participant over study period (range) | £349 (£0–1,746) | ||

Health resource use

Health resource use questionnaires were returned by 320 participants (93%). By combining self-reported data and data from medical records, the level of missing data for health-care resources was reduced to an average of 0.5% per variable (ranging between 0% for hospital outpatient visits and A&E visits to 19.5% for self-reported duration of GP visit). Table 2 shows the results of the cost analysis for health-care resource use. Excluding intervention costs, mean health-care costs in the intervention arm were £1,722, compared with £1,659 for the control arm. Participants randomised to the falls prevention programme had fewer GP consultations recorded than those receiving standard care; however, all other health resource use items were slightly higher in the intervention arm. None of the differences were statistically significant. When the additional cost of the falls screening and prevention programme was added, average health care costs in the intervention arm rose to £2,238.

Table 2.

Health service resource use, costs and mean difference in costs

| Resource use item | Resource use and mean cost per participant |

Mean incremental cost (95% CI) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention arm (n = 172) |

Control arm (n = 171)a |

||||||||

| Resource use (units) | Mean costs | SD | Resource use (units) | Mean costs | SD | Incremental cost | Lower | Upper | |

| GP consultations | 1,043 | £228 | 253 | 1,150 | £247 | 205 | −£19 | −£554 | £620 |

| A&E visit | 43 | £38 | 80 | 33 | £27 | 61 | £11 | −£189 | £215 |

| Outpatient first visit | 65 | £51 | 114 | 54 | £42 | 100 | £9 | −£179 | £313 |

| Inpatient bed days | 552 | £1,374 | 4769 | 529 | £1,317 | 4967 | £57 | −£8,158 | £9,465 |

| Practice nurse consultations | 816 | £31 | 78 | 748 | £26 | 57 | £5 | −£101 | £187 |

| Falls prevention programme costs | £349 | 316 | — | — | £349 | £0 | £1,057 | ||

| Screening costs | £165 | — | — | — | — | £165 | — | — | |

| Total costs per participant | £2,238 | 4957 | £1,659 | 5100 | £578 | −£12,593 | £17,264 | ||

Costs undiscounted (2007–8 UK £). SD, standard deviation.

aBase-case analysis excluded extreme outlier with 107 non-injurious falls.

The most influential cost in our study was due to overnight hospital stays, with 34 participants in each arm receiving inpatient care during the follow-up period. Inpatient admissions due to falls were particularly resource-intensive, with a mean length of stay 29.4 days, compared with 10.9 days for non-falls-related admissions. Seven participants in intervention arm were admitted to hospital with falls, in comparison to six in the control arm (see Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online).

Cost-effectiveness

In the base-case using patient-level data, compared with usual care, the falls prevention programme was both more costly [mean incremental cost = £578 (95% confidence interval −£8188 to +£13,212)] and more effective [mean incremental effect = 0.17 falls averted per person-year (95% confidence interval −8.00 to +8.00)], with an incremental cost per fall averted (ICER) of £3,320 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cost-effectiveness at base case and various sensitivity analyses

| Falls prevention intervention (95% CI) |

Usual care (95% CI) |

Incremental costs (95% CI) | Incremental falls (averted) (95% CI) | ICER incremental cost per fall averted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost to NHS | Falls rate | Cost to NHS | Falls rate | ||||

| Base case (excludes outlier with 107 falls) intervention, n = 172; control n = 171 | £2,238 (£250–18,510) | 2.07 (0–12) | £1,659 (£16–16,917) | 2.24 (0–16) | £578 (−£8,118 to 13.212) | −0.17 (−8 to 8) | £3,320 |

| Including outlier intervention, n = 172; control n = 172 | £2,238 (£250–18,510) | 2.07 (0–12) | £1, 660 (£16–16,752) | 2.85 (0–19) | £578 (−£8,118 to 13.212) | −0.78 (−12.5 to 8) | £738 |

| Complete case analysis intervention, n = 125; control n = 128 | £1,495 (£278–9,015) | 1.51 (0–8) | £1,045 (£16–5,667) | 1.66 (£16-£5,667) | £450 (−£4,186 to 8,298) | −0.14 (−8 to 7.9) | £3,118 |

As part of the sensitivity analysis, when the participant with 107 reported falls was included, the overall rate of falls in the control arm was raised considerably, which may misleadingly suggest increased cost-effectiveness of the falls prevention programme, as a lower ICER value of £738 per fall averted is generated, compared with usual care. The second sensitivity analysis, including only participants who completed all 12 monthly falls diaries, resulted in ICER result much closer to the base case (£3,118 per fall averted, compared with £3,320).

Decision uncertainty

A CEAC is plotted in Figure 1. A CEAC provides information about the probability that an intervention is cost-effective, given a decision-maker's willingness to pay for each additional health improvement (e.g. per fall averted). Compared with usual care, the probability that the intervention was cost-effective was always less than 40%, even if decision-makers were willing to pay more than £5,000 per fall averted.

Figure 1.

CEAC: cost per fall averted.

Discussion

This study tested a ‘screen and intervene’ approach to prevent future falls for at risk community-dwelling older people. The incremental falls averted per person-year was 0.17 (from 2.24 to 2.07 standardised falls rate). The falls prevention programme was more costly than usual care, yet neither incremental costs nor differences in effectiveness were significant.

The incremental cost per fall averted was £3,320. The decision to implement a falls prevention programme for a screened population would thus depend upon whether the health-care funder would put the value of averting accidental falls at a threshold value greater than £3,320 per fall averted.

Three limitations of the availability of economic data in this study warrant discussion. First, contrary to the hypothesis that costs of implementing an intervention may be offset by a decrease in the use of other health services, we found health-care resource use was slightly higher in the intervention arm (Table 2). Baseline costs were not measured and hence it is unclear if previous falls had resulted in high levels of health resource use or whether there were significant baseline cost differences between study arms. Costs incurred after randomisation constitute the cost outcome of interest in the trial. However, costs incurred prior to randomisation are a potential predictor of costs after randomisation and may explain variability in this cost.

Secondly, our economic evaluation took the perspective of the NHS, as opposed to social care or a patient perspective. Although data on PSS costs were collected, this was by self-report only and the proportion of missing data was high. Similarly, we did not include the cost of lost productivity in our comparative analysis. Further investigation of patient costs and societal factors may be justified.

Finally, cost-effectiveness analysis was adopted, measuring cost per fall averted. It is important to note that the results presented here will only be relevant to decisions concerning how best to allocate a specific ‘falls-prevention’ budget. To enable comparison of different health-care interventions on a common scale, cost-utility analyses would need to be conducted. Cost-utility analysis would allow greater comparative value with competing health-care packages, including those unrelated to falls. In addition, our analysis was limited to a 12-month follow-up period, which may have led to an underestimation of long-term costs and effects associated with the intervention.

It should be noted that the falls rates reported in this study are different from those reported in the clinical paper, as the economic study used imputation to generate a complete data set for falls and allow the maximum use of the economic data.

As detailed in a recent systematic review [2], studies have previously estimated the cost-effectiveness of multifactorial falls prevention strategies, but none in a UK population. The absence of strong conclusions of cost-effectiveness in this study mirrors recent research on falls prevention in the Netherlands [12], which found the intervention to be more expensive, but with additional health benefits—neither of which were statistically significant. We report higher costs and lower falls rates compared with usual care, but neither were greater than could have occurred by chance

Overall, we conclude there is a lack of evidence to suggest targeted screening in primary care and multifactorial falls prevention programmes in a day hospital setting is cost-effective. Although a reduction in the rate of falls occurred, costs were higher. More research into factors underlying uptake to screening, adherence to such programmes, health-related outcomes and personal and social cost consequences of falls and falls prevention is warranted.

Key point.

•A day hospital-based falls prevention programme delivered to a screened population of older people at risk of future falls was associated with fewer falls, but was more costly than usual care.

Contributors

Dr Rob Morris, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust, Dr Pradeep Kumar, Royal Lancaster Infirmary, Dr Jane Youde, Derbyshire Hospitals, Ms Rachel Taylor, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust and Dr Judi Edmans, School of Community Health Sciences, University of Nottingham Medical School.

T.M. conceived the idea and coordinated the initial successful pump priming funding application. T.S./S.P.C. helped with trial design, managed the trial and revised the paper. L.I./G.B. carried out the analysis, prepared the paper and edited comments. D.K., C.C., R.H.H., J.R.F.G., A.D. and T.M. all contributed to the trial design, trial delivery, interpretation of analyses and revision of the paper. All authors had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the trial and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. S.P.C. acts as guarantor.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data mentioned in the text is available to subscribers in Age and Ageing online.

Funding

Funding for the trial was obtained from Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and Lincolnshire research alliance, Research into Ageing, the British Geriatrics Society and Nottingham University Hospitals NHS trust. The funders had no role in the trial design, analysis or preparation of the publication. The main trial sponsor was the University of Nottingham, with Nottingham University Hospitals NHS trust and Derbyshire hospitals NHS trust acting as co-sponsors.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for the trial was obtained from Nottingham 2 ethics committee (reference 04/Q2404/93). All trial participants gave fully informed, written consent.

Trial registration

The trial was registered with Current Controlled Trials Ltd (reference number ISRCTN46584556) and the trial protocol published 27.2.6 (http://www.trialsjournal.com/content/7/1/5).

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Gillespie LD, Gillespie WJ, Robertson MC, Lamb SE, Cumming RG, Rowe BH. Interventions for preventing falls in elderly people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001:CD000340. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lamb SE. Scoping Exercise on Fallers’ Clinics, 2007.

- 3.Masud T, Coupland C, Drummond A, et al. Multifactorial day hospital intervention to reduce falls in high risk older people in primary care: a multi-centre randomised controlled trial [ISRCTN46584556] Trials. 2006;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-7-5. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conroy S. 2009. Preventing Falls in Older People. University of Nottingham. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anon. Avoiding Slips, Trips and Broken Hips. Department of Trade and Industry, ed. HMSO; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.NICE. London: National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence; 2008. Guide to the Methods of Technology Appraisal. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curtis L, Netten A. University of Kent at Canterbury. Personal Social Services Research U. Unit costs of health and social care 2008. Canterbury: University of Kent at Canterbury, Personal Social Services Research Unit; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Executive NHS. The New NHS 2008 Reference Costs. 2008. Department of Health.

- 9.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. 2nd edition. Hoboken, NJ, Chichester: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fenwick E, Claxton K, Sculpher M. Representing uncertainty: the role of cost-effectiveness acceptability curves. Health Econ. 2001;10:779–87. doi: 10.1002/hec.635. doi:10.1002/hec.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drummond MF. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 3rd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hendriks MR, Evers SM, Bleijlevens MH, van Haastregt JC, Crebolder HF, van Eijk JT. Cost-effectiveness of a multidisciplinary fall prevention program in community-dwelling elderly people: a randomized controlled trial (ISRCTN 64716113) Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2008;24:193–202. doi: 10.1017/S0266462308080276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.