Abstract

Therapies consisting of a combination of agents are an attractive proposition, especially in the context of diseases such as cancer, which can manifest with a variety of tumor types in a single case. However uncovering usable drug combinations is expensive both financially and temporally. By employing computational methods to identify candidate combinations with a greater likelihood of success we can avoid these problems, even when the amount of data is prohibitively large. Hitting Set is a combinatorial problem that has useful application across many fields, however as it is NP-complete it is traditionally considered hard to solve exactly. We introduce a more general version of the problem (α,β,d)-Hitting Set, which allows more precise control over how and what the hitting set targets. Employing the framework of Parameterized Complexity we show that despite being NP-complete, the (α,β,d)-Hitting Set problem is fixed-parameter tractable with a kernel of size O(αdkd) when we parameterize by the size k of the hitting set and the maximum number α of the minimum number of hits, and taking the maximum degree d of the target sets as a constant. We demonstrate the application of this problem to multiple drug selection for cancer therapy, showing the flexibility of the problem in tailoring such drug sets. The fixed-parameter tractability result indicates that for low values of the parameters the problem can be solved quickly using exact methods. We also demonstrate that the problem is indeed practical, with computation times on the order of 5 seconds, as compared to previous Hitting Set applications using the same dataset which exhibited times on the order of 1 day, even with relatively relaxed notions for what constitutes a low value for the parameters. Furthermore the existence of a kernelization for (α,β,d)-Hitting Set indicates that the problem is readily scalable to large datasets.

Introduction

Typically the selection of a drug therapy for a disease is limited to a single drug, however diseases such as cancer may present as a heterogeneous mix of subtypes of the general disease. In cases such as these multi-drug therapies may prove more effective than single drug therapies, and many trials have been conducted to this end [1]–[3]. Furthermore combinations of drugs may allow a more targeted approach for a selection of subtypes of a disease, while minimizing effects on unaffected cells. Unfortunately with the abundance of compounds available for the treatment of many conditions of interest, the time and expense in testing even all two drug combinations may be prohibitive. Therefore a smarter approach is needed. Vazquez [4] introduces the Hitting Set problem for this task in the context of oncological drug therapy. The Hitting Set problem is a combinatorial problem that proves extremely useful in modeling a large variety of problems in many domains including protein network discovery [5], metabolic network analysis [6], diagnostics [7]–[9], gene ontology [10] and gene expression analysis [11], [12].

The Hitting Set Problem

Hitting Set is a combinatorial problem that models the problem

of selecting a small group of elements to represent or cover a collection of

sets. Such a group that covers every set in the collection is called a hitting

set. Finding such a set without any constraint is simple, however if we required

that the size of the hitting set be relatively small, the problem becomes

computationally challenging ( -complete in a formal sense). This difficulty in obtaining

solutions with desirable qualities thus requires more thoughtful approaches.

-complete in a formal sense). This difficulty in obtaining

solutions with desirable qualities thus requires more thoughtful approaches.

We now give some technical details and formal definitions of the problems of interest.

Hitting Set is equivalent to the Set Cover

problem [13], and when otherwise unrestricted, is equivalent

to the Red/Blue Dominating Set

[14]

problem and is related to the  -Feature Set

[15]

problem.

-Feature Set

[15]

problem.

The decision version of the Hitting Set problem is defined as follows:

Hitting Set

Instance: A set

and a collection

and an integer

.

Question: Is there a set

with

such that for every

we have

?

The set  is called a hitting set for

is called a hitting set for

, or simply a hitting set. For an element

, or simply a hitting set. For an element  and an element

and an element  if

if  we say that

we say that  hits

hits

. This problem is

. This problem is  -complete even when the maximum size of each element of

-complete even when the maximum size of each element of  is two (by equivalence with Vertex Cover

[13])

and

is two (by equivalence with Vertex Cover

[13])

and  -complete for parameter

-complete for parameter  ; Cotta and Moscato [16] give a parameterized

proof via

; Cotta and Moscato [16] give a parameterized

proof via  -Feature Set and Paz and Moran [17] give a

proof which along with the equivalence of Hitting Set and

Set Cover leads to the same result, though predates the

parameterized complexity framework. However if we restrict the cardinality of

the elements of

-Feature Set and Paz and Moran [17] give a

proof which along with the equivalence of Hitting Set and

Set Cover leads to the same result, though predates the

parameterized complexity framework. However if we restrict the cardinality of

the elements of  to

to  the problem, while remaining

the problem, while remaining  -complete, becomes fixed-parameter tractable where

-complete, becomes fixed-parameter tractable where  is a constant and the parameter is

is a constant and the parameter is  [18]. In this case the problem is known as the

Hitting Set for Sets of Size

[18]. In this case the problem is known as the

Hitting Set for Sets of Size

or

or  -Hitting Set problem. We note that

Hitting Set has several equivalent formulations, in

particular we choose to use the bipartite graph representation where

-Hitting Set problem. We note that

Hitting Set has several equivalent formulations, in

particular we choose to use the bipartite graph representation where  and

and  form the two partite vertex sets of the graph and an edge

form the two partite vertex sets of the graph and an edge  corresponds to the element

corresponds to the element  being an element of

being an element of  . This allows us to employ some simplifying graph theoretic

terminology and techniques. We generalize this problem to include the case where

we may want the elements of

. This allows us to employ some simplifying graph theoretic

terminology and techniques. We generalize this problem to include the case where

we may want the elements of  to be hit more than once. In particular this includes the case

where we ask if all the sets of

to be hit more than once. In particular this includes the case

where we ask if all the sets of  can be hit

can be hit  times, but extends to the case where the elements of

times, but extends to the case where the elements of  can be hit up to

can be hit up to  times. We encode this by the use of a hitting function

times. We encode this by the use of a hitting function  . Our problem then becomes the

. Our problem then becomes the  -Multiple

-Multiple

-Hitting Set (or (

-Hitting Set (or ( )-Hitting Set):

)-Hitting Set):

-Hitting Set

Instance: A bipartite graph

where for all

we have

, a hitting function

and an integer

.

Question: Is there a set

with

such that for every

we have

?

When  for all

for all  , (

, ( )-Hitting Set can be

)-Hitting Set can be  -approximated in time

-approximated in time  [19], but cannot be approximated with a factor of

[19], but cannot be approximated with a factor of  for any

for any  unless

unless  [20].

[20].

Results and Discussion

The Fixed-Parameter Tractability of ( )-Hitting Set

)-Hitting Set

As we prove in the

Materials and Methods

section, the ( )-Hitting Set problem is fixed-parameter

tractable, and indeed a more general variant the (

)-Hitting Set problem is fixed-parameter

tractable, and indeed a more general variant the ( )-Hitting Set problem is also fixed parameter

tractable when we take the maximum degree

)-Hitting Set problem is also fixed parameter

tractable when we take the maximum degree  of the class vertices

of the class vertices  as a constant and the size

as a constant and the size  of the hitting set and the maximum desired coverage

of the hitting set and the maximum desired coverage  as a joint parameter. Though the problem is formally hard -

which would normally give the intuition that an exact solution would be too

expensive to compute - the fixed-parameter tractability indicates that it is

likely that we can obtain an exact solution efficiently. Armed with this

knowledge we proceed with the experiments of the following section, where we use

the drug response data of the NCI60 anti-tumor drug screening program to

determine a sets of drugs that hit cancerous cell lines multiple times. These

drug sets are than mathematically supportable candidates for combination

chemotherapies. Moreover we are able to tune the nature of the hitting sets via

the numbers

as a joint parameter. Though the problem is formally hard -

which would normally give the intuition that an exact solution would be too

expensive to compute - the fixed-parameter tractability indicates that it is

likely that we can obtain an exact solution efficiently. Armed with this

knowledge we proceed with the experiments of the following section, where we use

the drug response data of the NCI60 anti-tumor drug screening program to

determine a sets of drugs that hit cancerous cell lines multiple times. These

drug sets are than mathematically supportable candidates for combination

chemotherapies. Moreover we are able to tune the nature of the hitting sets via

the numbers  ,

,  and

and  , which allows us to control which cell lines are targetted

(and which are specifically not) and how much each cell line is hit in the

solution.

, which allows us to control which cell lines are targetted

(and which are specifically not) and how much each cell line is hit in the

solution.

A Comparative Application

The NCI60 human tumor anti-cancer drug screen dataset [21] was established

in the 1980s as an enabling tool for anti-cancer drug development. Included in

this dataset is response data for over  drugs against the

drugs against the  cell lines of the dataset. Vazquez [4] highlights the

utility of a hitting set approach in developing multi-drug therapies for

heterogeneous malignancies; given the plethora of available compounds, testing

multi-drug combinations exhaustively is prohibitive if not impossible. Applying

hitting set to efficacy data measured on an individual basis for each compound

allows us to determine possible drug combinations that would provide the best

chance of efficacy against many cancer types. Using the GI50 response NCI60

dataset (available from the DTP website [22]) Vazquez uncovers a

minimum hitting set with three compounds that cumulatively gives a good response

with all cell lines in the dataset, where a response is considered good if it is

more than two standard deviations above the mean of the z-transformed response

data. Vazquez uses first a greedy highest-degree-first approach to give an

estimate of the maximum size of a minimum hitting set, followed by either an

exhaustive search or simulated annealing, depending on the size of the hitting

set. Vazquez reports times for such approaches on the order of one day on a

desktop computer.

cell lines of the dataset. Vazquez [4] highlights the

utility of a hitting set approach in developing multi-drug therapies for

heterogeneous malignancies; given the plethora of available compounds, testing

multi-drug combinations exhaustively is prohibitive if not impossible. Applying

hitting set to efficacy data measured on an individual basis for each compound

allows us to determine possible drug combinations that would provide the best

chance of efficacy against many cancer types. Using the GI50 response NCI60

dataset (available from the DTP website [22]) Vazquez uncovers a

minimum hitting set with three compounds that cumulatively gives a good response

with all cell lines in the dataset, where a response is considered good if it is

more than two standard deviations above the mean of the z-transformed response

data. Vazquez uses first a greedy highest-degree-first approach to give an

estimate of the maximum size of a minimum hitting set, followed by either an

exhaustive search or simulated annealing, depending on the size of the hitting

set. Vazquez reports times for such approaches on the order of one day on a

desktop computer.

We revisit Vasquez's experiment, using data reduction (though it is not

necessary to employ the more complex rules given in the kernelization proof)

with IBM ILOG CPLEX [23] as the kernel solver by framing the problem

as a integer programming problem. We use the same threshold for the

z-transformation to identify significant response levels. Using this approach we

reduce the time to solve the instance to less than  seconds, where most of the time is spent loading and reducing

the data, with CPLEX solving the integer programming instance in approximately

seconds, where most of the time is spent loading and reducing

the data, with CPLEX solving the integer programming instance in approximately  milliseconds. Furthermore this approach guarantees optimality

in the size of the hitting set.

milliseconds. Furthermore this approach guarantees optimality

in the size of the hitting set.

From here we employ more a more recent version of the NCI60 dataset (2009 as

compared to Vazquez's 2006). At the time of writing, the latest NCI60

dataset includes 14 additional cell lines, however we remove these, as there is

insufficient response data in the dataset, leading to inflated hitting set

sizes. The latest data also includes a further  compounds. We note that employing the new GI50 response data

we are able to uncover

compounds. We note that employing the new GI50 response data

we are able to uncover  element hitting sets involving compounds not available in the

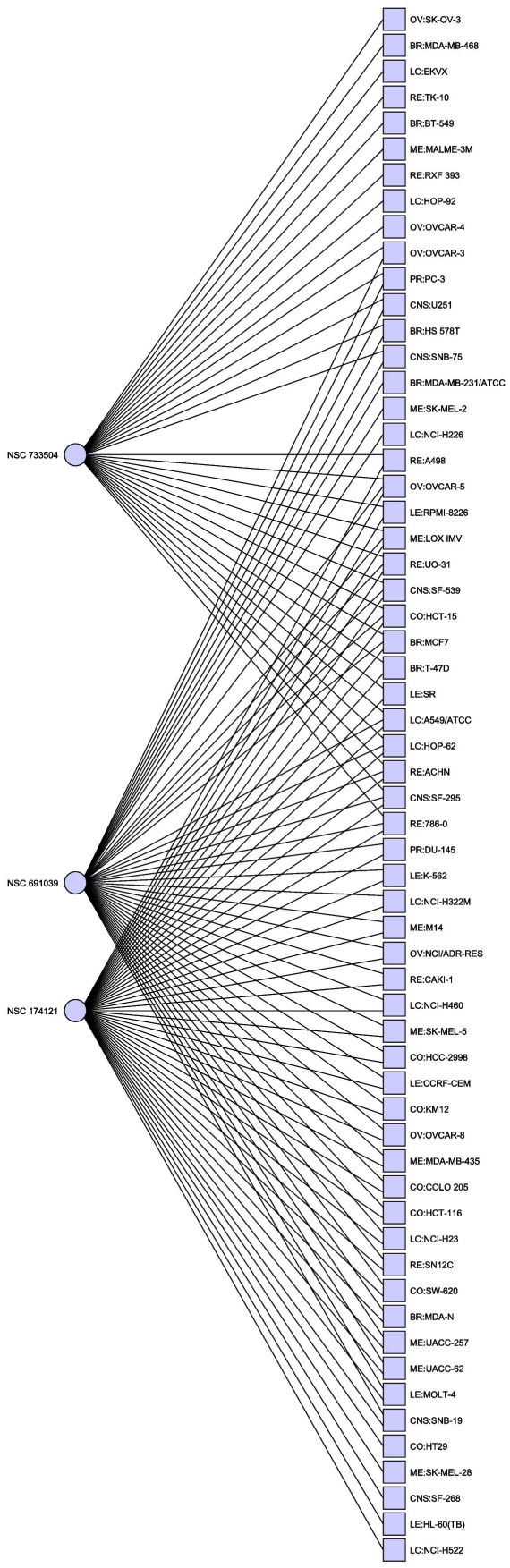

earlier dataset (an example is given in Table 1 and Figure 1), in particular Everolimus (NSC

733504) a drug now used for the treatment of advanced renal cancer which is also

giving positive results in phase II trials for metastatic melanoma [24], [25].

However there have recently been some concerns over the provenance of some of

the cell lines in the NCI60 dataset. In particular Lorenzi et al.

[26]

suggested that the MDA-N cell line, nominally a breast cancer cell line is in

fact similar the M14 and MDA-MB-435 cell lines, and thus should be is in fact a

melanoma cell line. Chambers [27] however suggests that although M14 and

MDA-MB-435 are identical cell lines, they may not in fact be melanoma cell

lines. We do not attempt to resolve this dispute, however with regard to this,

and as a indication of the flexibility of the method we employ we consider both

the case where MDA-N is a breast cancer cell line and the the case where MDA-N

is a melanoma cell line.

element hitting sets involving compounds not available in the

earlier dataset (an example is given in Table 1 and Figure 1), in particular Everolimus (NSC

733504) a drug now used for the treatment of advanced renal cancer which is also

giving positive results in phase II trials for metastatic melanoma [24], [25].

However there have recently been some concerns over the provenance of some of

the cell lines in the NCI60 dataset. In particular Lorenzi et al.

[26]

suggested that the MDA-N cell line, nominally a breast cancer cell line is in

fact similar the M14 and MDA-MB-435 cell lines, and thus should be is in fact a

melanoma cell line. Chambers [27] however suggests that although M14 and

MDA-MB-435 are identical cell lines, they may not in fact be melanoma cell

lines. We do not attempt to resolve this dispute, however with regard to this,

and as a indication of the flexibility of the method we employ we consider both

the case where MDA-N is a breast cancer cell line and the the case where MDA-N

is a melanoma cell line.

Table 1. Minimal hitting set using 2009 NCI60 data.

| NSC Number | Compound Name |

| 174121 | Methotrexate Derivative |

| 691039 | (S)-7-Hydroxy-1,2,3-trimethoxy-10-methylsulfanyl-6,7-dihydro-5H-benzo[a]heptalen-9-one |

| 733504 | Everolimus/Afinitor |

Minimal hitting set for NCI60 GI50 response data from 2009.

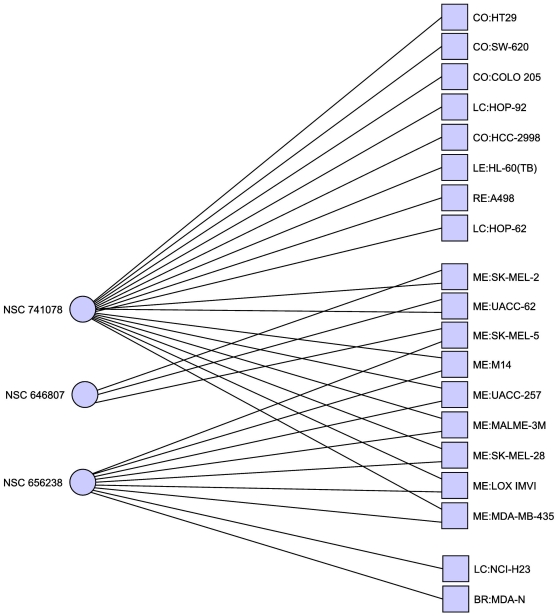

Figure 1. Minimal hitting set hitting for the NCI60 dataset.

This hitting set hits all cell lines at least once, but is further optimized to hit all target cell lines the maximal number of times. Of particular note are NSC 174121, a methotrexate derivative and NSC733504, Everolimus/Afinitor, both known anti-cancer agents.

Employing the ( )-Hitting Set model gives more flexibility in

what kind of therapy we would like to pursue. For instance, by choosing

)-Hitting Set model gives more flexibility in

what kind of therapy we would like to pursue. For instance, by choosing  for all vertices, we are able to find a hitting set that hits

every cell line at least twice (see Table 2). However the size of this hitting

set is

for all vertices, we are able to find a hitting set that hits

every cell line at least twice (see Table 2). However the size of this hitting

set is  , which is likely to be beyond the point where the trade off

between anti-cancer efficacy and side effects is acceptable. Fortunately we can

exploit (

, which is likely to be beyond the point where the trade off

between anti-cancer efficacy and side effects is acceptable. Fortunately we can

exploit ( )-Hitting Set more intelligently. For example

we may wish to find a hitting set that specifically targets breast cancer cell

lines – for which we set all breast cancer cell line vertices to have

)-Hitting Set more intelligently. For example

we may wish to find a hitting set that specifically targets breast cancer cell

lines – for which we set all breast cancer cell line vertices to have  and all other cell lines to have

and all other cell lines to have  . This gives a hitting set that hits only

breast cancer cell lines, which may be useful in minimizing unwanted peripheral

damage to non-breast cancer cells. This gives a hitting set with three elements.

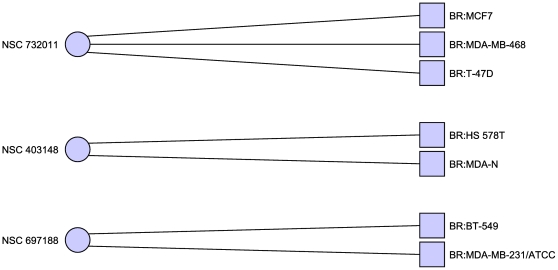

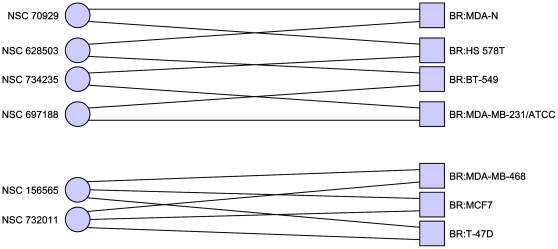

In the case where we considered MDA-N to be a breast cancer cell line (see Table 3 and Figure 2) this set includes

the compound deoxypodophyllotoxin, which is known to induce apoptosis [28]. If

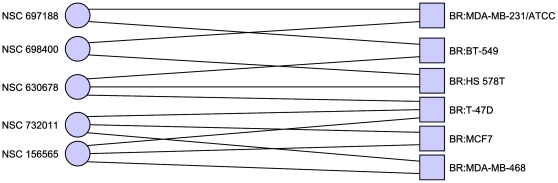

we consider MDA-N as a melanoma cell line we obtain a different hitting set (see

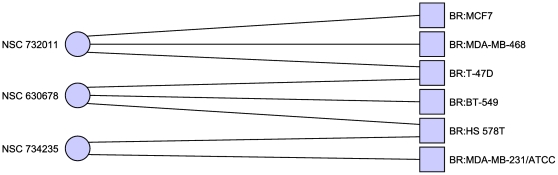

Table 4 and Figure 3). If we relax our

requirements an allow other cell lines to be hit at most once we can obtain a

hitting set that hits the breast cancer cell lines more (Table 5 and Figure 4). The results when we set

. This gives a hitting set that hits only

breast cancer cell lines, which may be useful in minimizing unwanted peripheral

damage to non-breast cancer cells. This gives a hitting set with three elements.

In the case where we considered MDA-N to be a breast cancer cell line (see Table 3 and Figure 2) this set includes

the compound deoxypodophyllotoxin, which is known to induce apoptosis [28]. If

we consider MDA-N as a melanoma cell line we obtain a different hitting set (see

Table 4 and Figure 3). If we relax our

requirements an allow other cell lines to be hit at most once we can obtain a

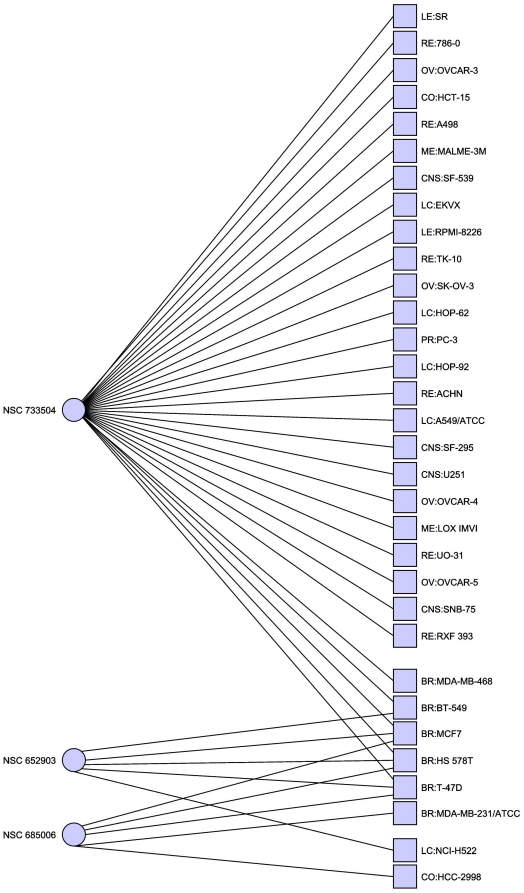

hitting set that hits the breast cancer cell lines more (Table 5 and Figure 4). The results when we set  to

to  for all breast cancer lines are given in Table 6 and Figure 5 (including MDA-N) and

Table 7 and Figure 6 (excluding MDA-N). We

note particularly that in the case where MDA-N is included, the optimal hitting

set uncovered includes Docetaxel, a well known anti-cancer agent [29] for several cancer types including breast cancer.

Interestingly Docetaxel is also currently included in several clinical trials

examining its potential as part of a multi-drug therapy [30]–[34].

for all breast cancer lines are given in Table 6 and Figure 5 (including MDA-N) and

Table 7 and Figure 6 (excluding MDA-N). We

note particularly that in the case where MDA-N is included, the optimal hitting

set uncovered includes Docetaxel, a well known anti-cancer agent [29] for several cancer types including breast cancer.

Interestingly Docetaxel is also currently included in several clinical trials

examining its potential as part of a multi-drug therapy [30]–[34].

Table 2. Minimal double hitting set.

| NSC Number | Compound Name |

| 147340 | Anisomycin hydrochloride |

| 174121 | Methotrexate derivate |

| 314018 | Ansamitocin derivate TN-006 |

| 691039 | (7S)-7-hydroxy-1,2,3-trimethoxy-10-methylsulfanyl-6, 7-dihydro-5H-benzo[a]heptalen-9-one |

| 712807 | Capecitabine |

| 733504 | Everolimus/Afinitor |

Minimal hitting set hitting each cell line at least twice.

Table 3. Minimal hitting set targeting only breast cancer.

| NSC Number | Compound Name |

| 403148 | Deoxypodophyllotoxin |

| 697188 | 2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-5-[8-[5-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl]octyl]-1,3,4-oxadiazole |

| 732011 | 21-(2-N,N-Diethylaminoethyl)oxy-7.alpha.-methyl-19-norpregna-1,3,5(10)-triene-3-O-sulfamate |

Minimal hitting set hitting breast cancer cell lines at least once, and all other cell lines zero times.

Figure 2. Minimal hitting set hitting only breast cancer cell lines.

Including the disputed MDA-N cell line. This hitting set also reveals additional structure with each drug targeting a specific, disjoint subset of the breast cancer cell lines. Only cell lines with at least one adjacent compound are shown.

Table 4. Minimal hitting set targeting only breast cancer without MDA-N.

| NSC Number | Compound Name |

| 630678 | Streptomyces antibiotic |

| 732011 | 21-(2-N,N-Diethylaminoethyl)oxy-7.alpha.-methyl-19-norpregna-1,3,5(10)-triene-3-O-sulfamate |

| 734235 | isoindolo[1,2-a]quinoxalin-4(5H)-one |

Minimal hitting set hitting breast cancer cell lines at least once, and all other cell lines zero times.

Figure 3. Minimal hitting set hitting only breast cancer cell lines.

Excluding the disputed MDA-N cell line. In this case the hitting set is much less clearly separated, though two of the cell lines are now hit twice. Only cell lines with at least one adjacent compound are shown.

Table 5. Minimal hitting set targeting breast cancer but allowing other cell lines to be hit.

| NSC Number | Compound Name |

| 652903 | Saframycin AR1(AH2) |

| 685006 | 2-imino-8-methoxy-N-phenylchromene-3-carboxamide |

| 733504 | Everolimus/Afinitor |

Minimal hitting set hitting breast cancer cell lines at least once, and all other cell lines zero times.

Figure 4. Minimal hitting set hitting only breast cancer cell lines.

Excluding the disputed MDA-N cell line. In this case we allow non-breast cancer cell lines to be hit at most once. By relaxing the restriction on hitting non-breast cancer cell lines, we obtain a hitting set which hits more of the breast cancer cell lines repeatedly. The trade-off being that other cell lines are also affected, increasingly the likelihood that non-cancerous cells are also affected by the treatment, as the compounds are less specific to a particular genetic signature. Only cell lines with at least one adjacent compound are shown.

Table 6. Minimal hitting set hitting breast cancer twice, and no others, with MDA-N.

| 70929 | Hedamycin |

| 156565 | 1-hydroxy-4-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)anilino]anthracene-9,10-dione |

| 628503 | Docetaxel |

| 697188 | 2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-5-[8-[5-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl]octyl]-1,3,4-oxadiazole |

| 732011 | 21-(2-N,N-Diethylaminoethyl)oxy-7.alpha.-methyl-19-norpregna-1,3,5(10)-triene-3-O-sulfamate |

| 734235 | isoindolo[1,2-a]quinoxalin-4(5H)-one |

Minimal hitting set hitting breast cancer cell lines at least once, and all other cell lines zero times.

Figure 5. Minimal hitting set hitting breast cancer cell lines twice.

Including the disputed MDA-N cell line. In this case the breast cancer cell lines separate neatly into two groups, with the first group forming a cycle and the second group forming a complete bipartite graph. Only cell lines with at least one adjacent compound are shown.

Table 7. Minimal hitting set hitting breast cancer twice, and no others, without MDA-N.

| 156565 | 1-hydroxy-4-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)anilino]anthracene-9,10-dione |

| 630678 | Streptomyces antibiotic |

| 697188 | 2-(4-methoxyphenyl)-5-[8-[5-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazol-2-yl]octyl]-1,3,4-oxadiazole |

| 698400 | 5-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrobenzo[a]phenanthridine |

| 732011 | 21-(2-N,N-Diethylaminoethyl)oxy-7.alpha.-methyl-19-norpregna-1,3,5(10)-triene-3-O-sulfamate |

Minimal hitting set hitting breast cancer cell lines at least once, and all other cell lines zero times.

Figure 6. Minimal hitting set hitting breast cancer cell lines twice.

Excluding the disputed MDA-N cell line. Without the MDA-N cell line, the breast cancer cell lines do not separate, although the complete bipartite component is a subgraph of this graph, however we gain a greater number of hits per cell line in this case. Only cell lines with at least one adjacent compound are shown.

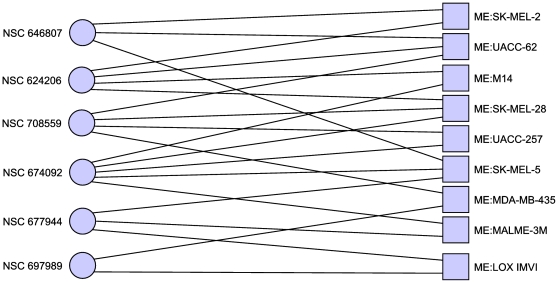

In another example, we may wish to target melanoma cell lines exclusively, and

furthermore, we may wish to attack each cell line with at least two drugs at

once. However in this case (where  for melanoma cell lines and

for melanoma cell lines and  for all others) the minimal hitting set size is

for all others) the minimal hitting set size is  (or

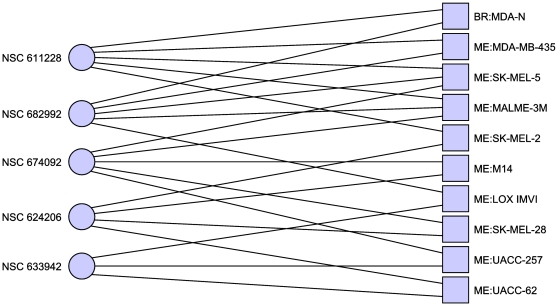

(or  if MDA-N is included as a melanoma cell line – Table 8 and Figures 7 & 8). Considering that a

therapeutic cocktail involving

if MDA-N is included as a melanoma cell line – Table 8 and Figures 7 & 8). Considering that a

therapeutic cocktail involving  compounds may have excessive side effects, we can relax the

requirements, and allow

compounds may have excessive side effects, we can relax the

requirements, and allow  for non-melanoma cell lines. In this case we find that the

smallest hitting set is of size

for non-melanoma cell lines. In this case we find that the

smallest hitting set is of size  . By altering the focus when solving the kernel by fixing the

hitting set size (

. By altering the focus when solving the kernel by fixing the

hitting set size ( ) at

) at  and maximizing the total degree of the vertices in the hitting

set, subject to the

and maximizing the total degree of the vertices in the hitting

set, subject to the  and

and  constraints, we can obtain the minimal size hitting set that

hits our targets as much as possible, within the bounds given by the

constraints. This results in the hitting sets in Tables 9 & 10 and Figures 9 & 10. Of note is AZD6244, which is currently

involved in

constraints, we can obtain the minimal size hitting set that

hits our targets as much as possible, within the bounds given by the

constraints. This results in the hitting sets in Tables 9 & 10 and Figures 9 & 10. Of note is AZD6244, which is currently

involved in  anti-cancer drug trials [35] and has

been identified as a potent kinase inhibitor [36], [37].

anti-cancer drug trials [35] and has

been identified as a potent kinase inhibitor [36], [37].

Table 8. Minimal hitting set targeting melanoma twice, without MDA-N.

| 624206 | N-[2-[(4-chlorophenyl)methyldisulfanyl]ethyl]decan-1-amine hydrochloride |

| 646807 | 2-(2-Isonicotinoylhydrazino)-N-(3-methyl-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydro-2-naphthalenyl)-2-oxoacetamide |

| 674092 | 2-phenyl-N-[3-[4-[3-[(2-phenylquinoline-4-carbonyl)amino]propyl]piperazin-1-yl]propyl]quinoline-4-carboxamide hydrochloride |

| 677944 | 6-[2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)ethylamino]quinoline-5,8-dione |

| 697989 | dicopper 2-acetyloxy-3,5-di(propan-2-yl)benzoate |

| 708559 | 2-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-N-methyl-N-[3-[methyl(3-pyrrolidin-1-ylpropyl)amino]propyl]acetamide |

Minimal hitting set hitting melanoma cell lines at least twice and no others. This result does not include MDA-N as a melanoma cell line.

Figure 7. Minimal hitting set hitting melanoma cell lines at least 2 and no other cell lines.

This hitting set also maximizes the number of hits on the melanoma cell lines. Only cell lines with at least one adjacent compound are shown.

Figure 8. Minimal hitting set hitting melanoma cell lines at least 2 and no other cell lines.

Including the disputed MDA-N cell line. It is interesting to note that

including MDA-N as a melanoma cell line rather than a breast cancer cell

line reduces the size of the minimal hitting set from  to

to  . This hitting set also maximizes the number of hits on

the melanoma cell lines. Only cell lines with at least one adjacent

compound are shown.

. This hitting set also maximizes the number of hits on

the melanoma cell lines. Only cell lines with at least one adjacent

compound are shown.

Table 9. Minimal hitting set targeting melanoma, without MDA-N.

| NSC Number | Compound Name |

| 646807 | 2-(2-Isonicotinoylhydrazino)-N-(3-methyl-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydro-2-naphthalenyl)-2-oxoacetamide |

| 656238 | 2-Methyl-4,8-dihydrobenzo[1,2-b:5,4-b′]dithiophene-4,8-dione |

| 741078 | AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) |

Minimal hitting set hitting melanoma cell lines at least twice, all others at most once, maximizing the degree of the melanoma cell line vertices.

Table 10. Minimal hitting set targeting melanoma, with MDA-N.

| NSC Number | Compound Name |

| 361127 | Destruxin E |

| 624206 | N-[2-[(4-chlorophenyl)methyldisulfanyl]ethyl]decan-1-amine hydrochloride |

| 656238 | 2-Methyl-4,8-dihydrobenzo[1,2-b:5,4-b′]dithiophene-4,8-dione |

Minimal hitting set hitting melanoma cell lines at least twice, all others at most once, maximizing the degree of the melanoma cell line vertices.

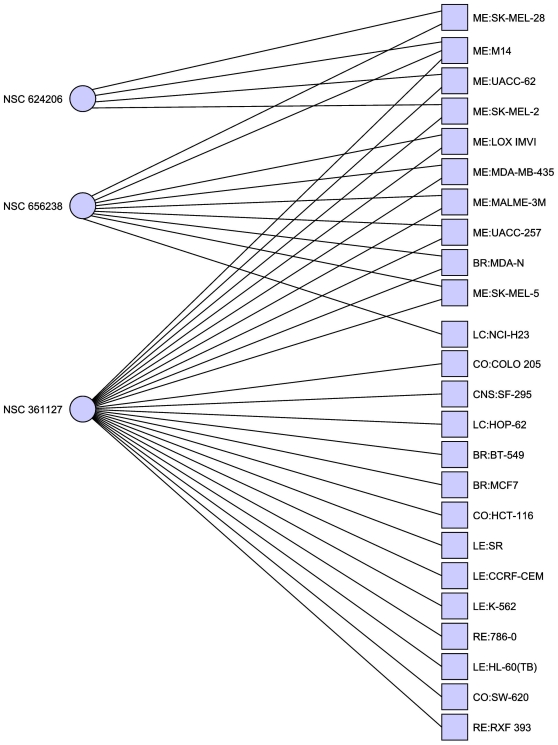

Figure 9. Minimal hitting set hitting melanoma cell lines at least 2 and all other cell lines at most once.

For this we consider MDA-N as a non-melanoma cell line, however it is also hit by the hitting set, though only once. This hitting set also maximizes the number of hits on the melanoma cell lines. Only cell lines with at least one adjacent compound are shown.

Figure 10. Minimal hitting set hitting melanoma cell lines at least 2 and all other cell lines at most once.

Including MDA-N as a melanoma cell line. The key difference with the case where we consider MDA-N to be a non-melanoma cell line is that in this case we obtain a hitting set that hits the melanoma cell lines slightly more. Only cell lines with at least one adjacent compound are shown.

Conclusion

Given the size of modern datasets, and the expectation that they will only get

larger, it is clear that we require efficient approaches to solving important

computational biology problems. The first phase of any such approach is simply

defining the problem at hand. Unfortunately once clearly stated, many such

problems are  -hard or worse. However this need not mean that we must resort

to inexact or approximate approaches, which could be undesirable in a field such

as drug selection. Parameterized Complexity provides a toolkit for dealing with

nominally hard problems, and identifying cases where despite super-polynomial

running times, we may still expect good performance.

-hard or worse. However this need not mean that we must resort

to inexact or approximate approaches, which could be undesirable in a field such

as drug selection. Parameterized Complexity provides a toolkit for dealing with

nominally hard problems, and identifying cases where despite super-polynomial

running times, we may still expect good performance.

The drug selection problem as examined here is one such problem. It is modeled

well by the  -Hitting Set problem, which is

fixed-parameter tractable when parameterized by the maximum size of the hitting

set. Therefore we can expect that despite being

-Hitting Set problem, which is

fixed-parameter tractable when parameterized by the maximum size of the hitting

set. Therefore we can expect that despite being  -complete, it would be relatively quick to solve when these

parameters are small. However we demonstrate that the much more flexible variant (

-complete, it would be relatively quick to solve when these

parameters are small. However we demonstrate that the much more flexible variant ( )-Hitting Set is also fixed-parameter

tractable, with only the addition of a single parameter - the maximum of the

minimum number of times any vertex should be hit. With (

)-Hitting Set is also fixed-parameter

tractable, with only the addition of a single parameter - the maximum of the

minimum number of times any vertex should be hit. With ( )-Hitting Set we are able to better control

the nature of the hitting set uncovered, and thus tailor any such hitting set to

a useful set of constraints, such as limits on which cell lines are to be hit,

the maximum any of these can be hit and of course the minimum number of times

any cell line should be hit. Moreover we can solve this problem quickly, and

guarantee optimality - without any notable restrictions on the parameters and

constants. This allows the quick generation of possible drug combinations for

testing, with guarantees of a certain baseline performance, eliminating the need

to exhaustively test all possible combinations, which would be financially and

temporally prohibitive.

)-Hitting Set we are able to better control

the nature of the hitting set uncovered, and thus tailor any such hitting set to

a useful set of constraints, such as limits on which cell lines are to be hit,

the maximum any of these can be hit and of course the minimum number of times

any cell line should be hit. Moreover we can solve this problem quickly, and

guarantee optimality - without any notable restrictions on the parameters and

constants. This allows the quick generation of possible drug combinations for

testing, with guarantees of a certain baseline performance, eliminating the need

to exhaustively test all possible combinations, which would be financially and

temporally prohibitive.

In brief this paper provides a robust and flexible methodology for multiple drug

selection, which can easily be applied to other domains that are modeled by the  -Hitting Set problem, with a sound

theoretical background as to why and how the problem can be solved efficiently,

despite its

-Hitting Set problem, with a sound

theoretical background as to why and how the problem can be solved efficiently,

despite its  -completeness. Moreover the existence of a kernelization for (

-completeness. Moreover the existence of a kernelization for ( )-Hitting Set indicates that even without

using a specialized commercial solver such as CPLEX, the problem is readily

scalable to large datasets. Given the speed at which we are able to solve

instances with on the order of

)-Hitting Set indicates that even without

using a specialized commercial solver such as CPLEX, the problem is readily

scalable to large datasets. Given the speed at which we are able to solve

instances with on the order of  vertices, we can expect that much larger datasets are also

solvable in a reasonable time.

vertices, we can expect that much larger datasets are also

solvable in a reasonable time.

A future extension that may be of interest would be to somehow encode in the problem the notion that some hitting vertices are incompatible, e.g., two compound may have severe adverse interactions, and thus can never be used together as a therapy, regardless of their individual usefulness.

Materials and Methods

Dataset and Computational Method

The dataset primarily employed is the NCI60 DTP Human Tumor Cell Line Screen, available from [22]. We use the version released in October 2009, and downloaded in April 2010. The raw dataset is presented as a series of cell line and compound pairs, along with the GI50 response measurement (the method for producing the measurements is also detailed by [22]) for that pair plus concentration information and statistical information. Where there are multiple entries for the same compound-cell line pair, we select the entry resulting from the experiment using the highest concentration of the compound. We extract this data into a matrix cross indexed by the NSC number of the compound and the name of the cell line. Where an entry does not exist for a given compound-cell line pair, we enter “NA” for that entry in the matrix.

Once the data is in this matrix format we threshold the data according to the

method used by Vazquez [4] whereby the raw data is subject to a

z-transformation over a logarithmic scale and then any value above a certain

threshold expressed in terms of the standard deviation to  , and anything below, including “NA”

values, to

, and anything below, including “NA”

values, to  . In line with Vazquez we choose two standard deviations as our

particular threshold for this paper, though this is adjustable.

. In line with Vazquez we choose two standard deviations as our

particular threshold for this paper, though this is adjustable.

We then construct a graph for the hitting set instance using the Java Universal

Network/Graph Framework (JUNG) [38] with the SetHypergraph class, representing

each compound with a vertex and each cell line with a (hyper)edge which carries

a weight indicating the number of times that edge is to be hit. This graph is

then reduced to remove vertices of zero degree, edges with no incident vertices

(which are noted as technically this would indicate a no instance unless that

edge does not require hitting) and vertices that are only adjacent to edges that

require zero hits. This basic reduction alone typically reduces the number of

vertices significantly, bringing the graph within a reasonable size for

immediate processing. From a theoretical standpoint the constant  is of importance, for the graph constructed as stated,

is of importance, for the graph constructed as stated,  (as we allow the natural value, rather than imposing an

external limit). In practice a

(as we allow the natural value, rather than imposing an

external limit). In practice a  value of this magnitude proves perfectly workable, and

returning to the theoretical viewpoint indicates that the instance is in a sense

already kernelized.

value of this magnitude proves perfectly workable, and

returning to the theoretical viewpoint indicates that the instance is in a sense

already kernelized.

Once the graph is reduced, we construct an integer programming instance

equivalent of the problem given the graph, and pass this instance to CPLEX [23]

(version 11.200) and search for an optimal solution to one of two objective

functions, given the constraints of the number of hits for each cell line (given

by the  value). The first objective function simply minimizes the size

of the hitting set (

value). The first objective function simply minimizes the size

of the hitting set ( ), for the second objective function we fix the size of the

hitting set, and maximize the number of hits on vertices where no maximum number

of hits has been set (the

), for the second objective function we fix the size of the

hitting set, and maximize the number of hits on vertices where no maximum number

of hits has been set (the  value). As part of this search CPLEX may apply some

unspecified proprietary reduction process.

value). As part of this search CPLEX may apply some

unspecified proprietary reduction process.

The figures were created using yEd Graph Editor [39].

The computer hardware employed is a Dell PowerEdge III Dual Xeon 5550 server with 32Gb of RAM, operating Red Hat Linux 64 bit EL 4 Server.

Theoretical Background and Kernelization Proof

Graph Theory and Notation

A (simple undirected) graph consists of a set  (the vertices), and a set

(the vertices), and a set  of two element subsets of

of two element subsets of  (the edges). A bipartite graph is a graph

where the vertices are partitioned into two partite sets, where all edges

have one endpoint in one set and the other endpoint in the other set, i.e.,

(the edges). A bipartite graph is a graph

where the vertices are partitioned into two partite sets, where all edges

have one endpoint in one set and the other endpoint in the other set, i.e.,  and

and  .

.

Given a graph  and two vertices

and two vertices  , we denote the edge between

, we denote the edge between  and

and  by

by  or equivalently

or equivalently  . Given two vertices

. Given two vertices  in

in  , if there is an edge

, if there is an edge  we say that

we say that  and

and  are adjacent and the

are adjacent and the  and

and  are incident on

are incident on  . Given a vertex

. Given a vertex  , the set

, the set  is the (open) neighborhood of

is the (open) neighborhood of  and consists off all vertices adjacent to

and consists off all vertices adjacent to  in

in  , we extend this notion in the natural way to sets of

vertices.

, we extend this notion in the natural way to sets of

vertices.

Parameterized Complexity

A parameterized (decision) problem is a formally defined

computational problem consisting of three components; the input, a special

part of the input called the parameter, and the question. Following Flum and

Grohe's [40] definition we may assume that the

parameter is derived from a polynomial time computable mapping from the

input to the natural numbers. A parameterized problem  is fixed-parameter tractable if there is

an algorithm

is fixed-parameter tractable if there is

an algorithm  such that for every instance

such that for every instance  where

where  is the input,

is the input,  is the parameter and

is the parameter and  ,

,  correctly answers Yes or No in time

bounded by

correctly answers Yes or No in time

bounded by  where

where  is a polynomial and

is a polynomial and  is a computable function.

is a computable function.

A polynomial time kernelization (or just

kernelization) is a polynomial time mapping that given

an instance  of a parameterized problem produces a new instance

of a parameterized problem produces a new instance  of the problem such that:

of the problem such that:

is a Yes-instance if and only if

is a Yes-instance if and only if  is a Yes-instance,

is a Yes-instance, and

and for some computable function

for some computable function  .

.

It is easy to see that if a problem has kernelization, then it is fixed-parameter tractable. It is also easy to prove that if a problem is fixed-parameter tractable, then it has a kernelization [41].

Parameterized complexity has a fully developed theory for determining when a

problem is unlikely to be fixed-parameter tractable, but as this is not

necessary for this work, we refer the reader to the monographs of Flum and

Grohe [40] and Downey and Fellows [42] for full

discussion, and simply state that if a problem is  -hard or

-hard or  -complete for any

-complete for any  , then the problem is not fixed-parameter tractable unless

certain complexity theoretic assumptions are false, which seems

unlikely.

, then the problem is not fixed-parameter tractable unless

certain complexity theoretic assumptions are false, which seems

unlikely.

The Fixed-Parameter Tractability of ( )-Hitting Set

)-Hitting Set

Our kernelization for ( )-Hitting Set follows the basic format of

Abu-Khzam's kernelization for

)-Hitting Set follows the basic format of

Abu-Khzam's kernelization for  -Hitting Set

[18].

-Hitting Set

[18].

Let  be an instance of (

be an instance of ( )-Hitting Set which we assume to have been

preprocessed for nonsense input such as vertices

)-Hitting Set which we assume to have been

preprocessed for nonsense input such as vertices  with

with  or

or  . Therefore we may assume that for all

. Therefore we may assume that for all  we have

we have  and that for all vertices

and that for all vertices  we have

we have  .

.

We first apply Reduction Rules 1 to 3 exhaustively, before applying Rules 4 and 5.:

Reduction Rule 1: If there is a vertex  with

with  then for every vertex

then for every vertex  for every vertex

for every vertex  reduce

reduce  by

by  , delete

, delete  from

from  and reduce

and reduce  by

by  . Finally, delete

. Finally, delete  from

from  .

.

Lemma 1 Reduction Rule 1 is sound.

Proof. If such a vertex  exists, then all its neighbors in

exists, then all its neighbors in  must be in the hitting set, and we can remove them from the

graph after suitably noting the effect for the vertices of

must be in the hitting set, and we can remove them from the

graph after suitably noting the effect for the vertices of  .

.

Note in particular that this rule effectively allows us to assume that  is at most

is at most  . This will be used implicitly in Reduction Rule 4.

. This will be used implicitly in Reduction Rule 4.

Reduction Rule 2: If there is a vertex  with

with  , delete

, delete  from

from  .

.

Lemma 2 Reduction Rule 2 is sound.

Proof. Clearly  requires no vertices to hit it, so may be ignored.

requires no vertices to hit it, so may be ignored.

Reduction Rule 3: If there are two vertices  such that

such that  and

and  , delete

, delete  from

from  .

.

Lemma 3 Reduction Rule 3 is sound.

Proof. If two such vertices  and

and  exist, then any hitting set that hits

exist, then any hitting set that hits  at least

at least  times will hit

times will hit  at least

at least  times.

times.

Let  be a set of size

be a set of size  vertices such that

vertices such that  is the pairwise intersection of the neighborhoods of a vertex

set

is the pairwise intersection of the neighborhoods of a vertex

set  . Let

. Let  .

.

Reduction Rule 4: Let  and

and  be vertex sets as described. For each

be vertex sets as described. For each  such that

such that  add a vertex

add a vertex  to

to  with

with  and edges such that

and edges such that  and delete

and delete  from

from  .

.

Lemma 4 Reduction Rule 4 is sound.

Proof. Let  be a Yes-instance of (

be a Yes-instance of ( )-Hitting Set. Then there is a set

)-Hitting Set. Then there is a set  with

with  that hits each element

that hits each element  of

of  at least

at least  times. Assume that there are sets

times. Assume that there are sets  and

and  as described in the reduction rule and that for some

as described in the reduction rule and that for some  we have that

we have that  . Let

. Let  be the subset of

be the subset of  that hits

that hits  . Assume further that

. Assume further that  , then for each

, then for each  there is at least one other vertex in

there is at least one other vertex in  , but then

, but then  , which contradicts the assumption that

, which contradicts the assumption that  is a Yes-instance.

is a Yes-instance.

Therefore the set  must be hit by

must be hit by  , so we may restrict our search to the intersection.

, so we may restrict our search to the intersection.

Lemma 5 Reduction Rule 4 can be computed in polynomial time.

Proof. Given a set of vertices  for some

for some  with

with  , we construct an auxiliary graph

, we construct an auxiliary graph  by taking for each

by taking for each  the subgraph of

the subgraph of  induced by the vertices

induced by the vertices  . If there is a maximum matching in

. If there is a maximum matching in  of size greater than

of size greater than  , then the matched vertices from

, then the matched vertices from  form the required set with pairwise neighbohood intersection

form the required set with pairwise neighbohood intersection  .

.

As  is a constant, we can iterate over all sets of vertices of

size

is a constant, we can iterate over all sets of vertices of

size  in time

in time  . The matchings can be computed in time

. The matchings can be computed in time  .

.

Definition 6 (Weakly Related Vertices) Given two vertices  ,

,  and

and  are weakly related if

are weakly related if  , and both

, and both  and

and  .

.

Let  be a maximal set of pairwise weakly related vertices. Let

be a maximal set of pairwise weakly related vertices. Let  be a set of vertices, and denote by

be a set of vertices, and denote by  the set of vertices of

the set of vertices of  whose neighborhood is a superset of

whose neighborhood is a superset of  . Further denote by

. Further denote by  the subset of

the subset of  where for each

where for each  we have

we have  .

.

Reduction Rule 5: Compute a maximal collection  of pairwise weakly related vertices. If

of pairwise weakly related vertices. If  apply the following algorithm:

apply the following algorithm:

for

downto

downto

do

do

for

downto

downto

do

do

for each set  where

where  and

and  do

do

if

then

then

Add a vertex  to

to  , edges such that

, edges such that  and set

and set  .

.

Delete  from

from  .

.

Lemma 7 Reduction Rule 5 is sound.

Proof. We defer the proof of the bound on the size of  until the proof of Lemma 8.

until the proof of Lemma 8.

Let  be a Yes-instance of (

be a Yes-instance of ( )-Hitting Set. Then there is a set

)-Hitting Set. Then there is a set  that hits

that hits  sufficiently. For sets of size

sufficiently. For sets of size  , Reduction Rule 4 proves the soundness of the first iteration

of the outer loop.

, Reduction Rule 4 proves the soundness of the first iteration

of the outer loop.

For each other iteration, assume that the iteration for sets of size  holds, then let

holds, then let  be set of size

be set of size  where

where  for some

for some  . If

. If  then by the pigeon hole principle there is some vertex

then by the pigeon hole principle there is some vertex  that is in at least

that is in at least  neighborhoods of vertices in

neighborhoods of vertices in  , but then

, but then  is a set that is the intersection of at least

is a set that is the intersection of at least  neighborhoods of vertices in some subset of

neighborhoods of vertices in some subset of  , contradicting the correctness of the previous iteration.

Therefore the entire set of vertices hitting each

, contradicting the correctness of the previous iteration.

Therefore the entire set of vertices hitting each  vertex is contained within

vertex is contained within  if

if  , so we may replace

, so we may replace  with a single vertex.

with a single vertex.

Note also that for each element of  there is at most

there is at most  sets

sets  , so we may iterate through all sets in time

, so we may iterate through all sets in time  , so we can perform the replacements in polynomial time.

, so we can perform the replacements in polynomial time.

Lemma 8

If

is a Yes-instance

of (

is a Yes-instance

of ( )-Hitting Set, reduced under

Reduction Rules 1 to 5, then

)-Hitting Set, reduced under

Reduction Rules 1 to 5, then

.

.

Proof. If  is a Yes-instance of (

is a Yes-instance of ( )-Hitting Set, then there is a set

)-Hitting Set, then there is a set  such that for every

such that for every  we have

we have  with

with  .

.

Claim 9

.

.

By construction, every vertex in  with degree at most

with degree at most  is in

is in  . Assume there is some

. Assume there is some  with

with  and

and  , then there must be some vertex

, then there must be some vertex  such that

such that  , but then as the degree of any vertex in

, but then as the degree of any vertex in  is at most

is at most  ,

,  , and Reduction Rule 3 would apply. Therefore there are no

vertices from

, and Reduction Rule 3 would apply. Therefore there are no

vertices from  not in

not in  .

.

Claim 10

.

.

As  hits each vertex of

hits each vertex of  at least once, by Reduction Rule 5 each element of

at least once, by Reduction Rule 5 each element of  as a singleton is in the neighborhood of at most

as a singleton is in the neighborhood of at most  vertices from

vertices from  . Therefore

. Therefore  .

.

Combining Claims 9 and 10 we have  . As each vertex of

. As each vertex of  has degree at most

has degree at most  , there are at most

, there are at most  vertices in

vertices in  , and the bound follows.

, and the bound follows.

Theorem 11 ( )-Hitting Set

is fixed-parameter tractable with parameter

)-Hitting Set

is fixed-parameter tractable with parameter

and has a kernel of size at most

and has a kernel of size at most

.

.

We note that although  must be a constant to obtain a polynomial time kernelization,

must be a constant to obtain a polynomial time kernelization,  may be alternatively given as an additional parameter, without

change to the kernelization.

may be alternatively given as an additional parameter, without

change to the kernelization.

This kernelization may be extended to an even more general version of the problem, where we not only specify lower bounds for the number of hits, but also upper bounds:

-Hitting Set

Instance: A bipartite graph

where for all

we have

, two hitting functions

and

and an integer

.

Question: Is there a set

with

such that for every

we have

?

Corollary 12 ( )-Hitting Set

is fixed-parameter tractable with parameter

)-Hitting Set

is fixed-parameter tractable with parameter

and has a kernel of size at most

and has a kernel of size at most

.

.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: The authors acknowledge the support of the Hunter Medical Research Institute, The University of Newcastle, and ARC Discovery Project DP0773279 (Application of novel exact combinatorial optimisation techniques and metaheuristic methods for problems in cancer research). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Albain KS, Crowley JJ, LeBlanc M, Livingston RB. Determinants of improved outcome in small-cell lung cancer: an analysis of the 2,580-patient southwest oncology group data base. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1990;8:1563–1574. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.9.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flamant F, Schwartz L, Delons E, Caillaud JM, Hartmann O, et al. Nonseminomatous malignant germ cell tumors in children. Multidrug therapy in stages III and IV. Cancer. 1984;54:1687–1691. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19841015)54:8<1687::aid-cncr2820540833>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fu KK, Silverberg IJ, Phillips TL, Friedman MA. Combined radiotherapy and multidrug chemotherapy for advanced head and neck cancer: results of a radiation therapy oncology group pilot study. Cancer Treatment Reports. 1979;63:351–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vazquez A. Optimal drug combinations and minimal hitting sets. BMC Systems Biology. 2009;3:81–86. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-3-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berman P, DasGupta B, Sontag ED. Randomized approximation algorithms for set multicover problems with applications to reverse engineering of protein and gene networks. Discrete Applied Mathematics. 2007;155:733–749. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haus UU, Klamt S, Stephen T. Computing knock-out strategies in metabolic networks. Journal of Computational Biology. 2008;15:259–268. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2007.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Kleer J, Mackworth AK, Reiter R. Characterizing diagnoses and systems. Artificial Intelligence. 1992;56:197–222. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leipins GE, Potter WD. A genetic algorithm approach to multiple-fault diagnosis. In: Davis L, editor. Handbook of Genetic Algorithms, Van Nostrand Reinhold Company; 1991. pp. 237–250. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reiter R. A theory of diagnosis from first principles. Artificial Intelligence. 1987;32:57–95. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hvidsten TR, Lægreid A, Komorowski HJ. Learning rule-based models of biological process from gene expression time profiles using gene ontology. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1116–1123. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruchkys D, Song S. A parallel approximation hitting set algorithm for gene expression analysis. 2002. pp. 75–81. In: 14th Symposium on Computer Architecture and High Performance Computing (SBAC-PAD 2002). Vitoria, Espirito Santo, Brazil.

- 12.Vinterbo SA, Kim EY, Ohno-Machado L. Small, fuzzy and interpretable gene expression based classifiers. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:1964–1970. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garey MR, Johnson DS. Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness. New York: W. H. Freeman & Co; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernau H. Parameterized Algorithmics: A Graph-Theoretic Approach. Germany: Habilitationsschrift, Universität Tübingen; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davies S, Russell S. NP-completeness of searches for smallest possible feature sets. In: Greiner R, Subramanian D, editors. AAAI Symposium on Intelligent Relevance. New Orleans: 1994. pp. 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cotta C, Moscato P. The k-feature set problem is W[2]-complete. Journal of Computer and System Sciences. 2003;67:686–690. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paz A, Moran S. Non deterministic polynomial optimization problems and their approximations. Theoretical Computer Science. 1981;15:251–277. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abu-Khzam FN. A kernelization algorithm for d-hitting set. Journal of Computer and Systems Sciences. 2010;76:524–531. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vazirani V. Approximation Algorithms. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2001. 380 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feige U. A threshold of ln n for approximating set cover. Journal of the ACM. 1998;45:634–652. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shoemaker RH. The NCI60 human tumour cell line anticancer drug screen. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2006;6:813–823. doi: 10.1038/nrc1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.NCI/NIH Website (Accessed 2010). Developmental Theraputics Program. http://dtp.nci.nih.gov/

- 23.IBM Website (Accessed 2010). ILOG CPLEX. http://www-01.ibm.com/software/integration/optimization/cplex/

- 24.Rao RD, Windschitl HE, Allred JB, Lowe VJ, Maples WJ, et al. Phase II trial of the mTOR inhibitor everolimus (RAD-001) in metastatic melanoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:8043. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peyton JD, Spigel DR, Burris HA, Lane C, Rubin M, et al. Phase II trial of bevacizumab and everolimus in the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma: Preliminary results. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:9027. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lorenzi PL, Reinhold WC, Varma S, Hutchinson AA, Pommier Y, et al. DNA fingerprinting of the NCI-60 cell line panel. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2009;8:713–724. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chambers AF. MDA-MB-435 and M14 cell lines: Identical but not M14 melanoma? Cancer Research. 2009;69:5292–5293. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shin SY, Yong Y, Kim CG, Lee YH, Lim Y. Deoxypodophyllotoxin induces G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in HeLa cells. Cancer Letters. 2010;287:231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lyseng-Williamson KA, Fenton C. Docetaxel: A review of its use in metastatic breast cancer. Drugs. 2005;65:2513–2531. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slamon D, Eiermann W, Robert N, Pienkowski T, Martin M, et al. Phase III randomized trial comparing doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by docetaxel (AC-¿T) with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide followed by docetaxel and trastuzumab (AC-¿TH) with docetaxel, carboplatin and trastuzumab (TCH) in Her2neu positive early breast cancer patients: BCIRG 006 study. Cancer Research. 2009;69:62. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perez EA, Hillman DW, Dentchev T, Le-Lindqwister NA, Geeraerts LH, et al. North central cancer treatment group (NCCTG) N0432: phase II trial of docetaxel with capecitabine and bevacizumab as first-line chemotherapy for patients with metastatic breast cancer. Annals of Oncology. 2010;21:269–274. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polyzos A, Malamos N, Boukovinas I, Adamou A, Ziras N, et al. FEC versus sequential docetaxel followed by epirubicin/cyclophosphamide as adjuvant chemotherapy in women with axillary node-positive early breast cancer: a randomized study of the Hellenic Oncology Research Group (HORG). Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2010;119:95–104. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0468-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joensuu H, Bono P, Kataja V, Alanko T, Kokko R, et al. Fluorouracil, Epirubicin, and Cyclophosphamide With Either Docetaxel or Vinorelbine, With or Without Trastuzumab, As Adjuvant Treatments of Breast Cancer: Final Results of the FinHer Trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:5685–5692. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.4577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sparano JA, Makhson AN, Semiglazov VF, Tjulandin SA, Balashova OI, et al. Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin Plus Docetaxel Significantly Improves Time to Progression Without Additive Cardiotoxicity Compared With Docetaxel Monotherapy in Patients With Advanced Breast Cancer Previously Treated With Neoadjuvant-Adjuvant Anthracycline Therapy: Results From a Randomized Phase III Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4522–4529. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.ClinicalTrialsgov Website (Accessed 2010). U.S. clinical trial registry. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home.

- 36.Davies B, Logie A, McKay JS, Martin P, Steele S, et al. AZD6244 (ARRY-142886), a potent inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase 1/2 kinases: mechanism of action in vivo, pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship, and potential for combination in preclinical models. Molecular Cancer Theraputics. 2007;6:2209–2219. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yeh TC, Marsh V, Bernat BA, Ballard J, Colwell H, et al. Biological characterization of ARRY-142886 (AZD6244), a potent, highly selective mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2 inhibitor. Clinical Cancer Research. 2007;13:1576. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Java Universal Network/Graph Framework Website (Accessed 2010). JUNG. http://jung.sourceforge.net/

- 39.yWorks Website (Accessed 2010). yEd. http://www.yworks.com/en/products_yed_about.html.

- 40.Flum J, Grohe M. Parameterized Complexity Theory. Berlin: Springer; 2006. 493 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niedermeier R. Invitation to Fixed-Parameter Algorithms. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. 316 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Downey RG, Fellows MR. Parameterized Complexity. Berlin: Springer; 1999. 533 [Google Scholar]