Abstract

To ascertain the consequences of severe leukopenia and the tempo of recovery, we studied the immunity of 56 adult patients treated for multiple sclerosis or systemic sclerosis with autologous CD34 cell transplantation using extremely lymphoablative conditioning. NK cell, monocyte, and neutrophil counts recovered to normal by 1 month; dendritic cell and B cell counts by 6 months; and T cell counts by 2 years posttransplant, although CD4 T cell counts remained borderline low. Initial peripheral expansion was robust for CD8 T cells but only moderate for CD4 T cells. Subsequent thymopoiesis was slow, especially in older patients. Importantly, levels of antibodies, including autoantibodies, did not drop substantially. Infections were frequent during the first 6 months, when all immune cells were deficient, and surprisingly rare (0.21 per patient year) at 7–24 months posttransplant, when only T cells (particularly CD4 T cells) were deficient. In conclusion, peripheral expansion of CD8 but not CD4 T cells is highly efficient. Prolonged CD4 lymphopenia is associated with relatively few infections, possibly due to antibodies produced by persisting pretransplant plasma cells.

Keywords: Immunodeficiency, T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, Autoimmunity

Introduction

Autoimmune diseases may be caused by a one time failure of negative selection leading to the generation of an autoreactive T or B cell clone. This hypothesis lead to the development of clinical trials of extremely lymphoablative therapy, typically with autologous CD34 cell transplantation to minimize hematological toxicity [1]. The aim was to eliminate the autoreactive T or B cell clone and hope that the error in negative selection would not be repeated. The trials have provided a unique opportunity to study the consequences of severe leukopenia (in particular, lymphopenia) and homeostatic recovery in humans. The conditioning used in our trials [2,3] consisted of total body irradiation and cyclophosphamide administered from day 5 to day 2 and anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) administered from day 5 to day 5; this resulted in severe lymphopenia (significantly more severe than after autologous transplantation for cancer using radio/chemotherapy conditioning without ATG). In addition, contrary to other clinical settings used to study the homeostatic recovery of lymphocytes (e.g., in AIDS patients treated with antiretroviral drugs or allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant recipients), the recovery from lymphopenia was only minimally influenced by factors altering the homeostatic recovery. In AIDS patients, T lymphopoieses might be hampered by HIV or antiretroviral drugs [4,5]. In allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant recipients, T and B lymphopoiesis might be hampered by graft-vs.-host disease (GVHD) or its treatment with immunosuppressive drugs [6–8]. In contrast, the autologous transplant recipients presented here were HIV-negative, did not develop true GVHD by definition, and were treated typically (per protocol) with only low-dose prednisone (≤0.5 mg kg−1 day−1). As prednisone was typically discontinued by 2 months posttransplant, immune recovery after 2 months posttransplant should reflect “natural” homeostatic recovery.

Methods

Patients and donors

Fifty-six patients with diseases of presumed autoimmune etiology (30 patients with systemic sclerosis and 26 patients with multiple sclerosis) underwent autologous CD34 cell transplantation as described [2,3]. Median age at transplant was 43 years (range, 23–61 years). There were 22 males and 34 females. None of the patients had a history of splenectomy. Twenty-eight patients were CMV seropositive pretransplant, 26 were CMV seronegative, and CMV serostatus was unknown for two patients. Transplant conditioning consisted of cyclophosphamide (120 mg/kg), total body irradiation (8 Gy), and ATG (typically of equine origin, 90 mg/kg). The CD34 cell autografts contained median 261.3 × 106 CD34 cells, 10.5 × 106 monocytes, 1.0 × 106 NK cells, 0.1 × 106 dendritic cells, 2.0 × 106 CD4 T cells, 1.2 × 106 CD8 T cells, and 8.1 × 106 B cells (determined in 27 patients). Blood for immune assays was drawn pretransplant (before filgrastim treatment for CD34 cell harvest), on day 7, and at approximately 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 months posttransplant. Patients were followed for the assessment of immunity (by laboratory parameters and infection rates) for 2 years or until death, disease progression/relapse/pulmonary toxicity or last contact, whatever occurred first. The follow-up ended at the time of disease progression/relapse or pulmonary toxicity because at that time patients typically started treatment with corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive drugs. Thirty-seven patients were followed for 2 years and 19 patients were followed for <2 years. The numbers of blood samples analyzed at each time point are given in the legends to Figs. 1–4. Posttransplant infection prophylaxis and prednisone were administered as described in Table 1. During the 2-year follow-up, patients were not treated with immunoglobulin.

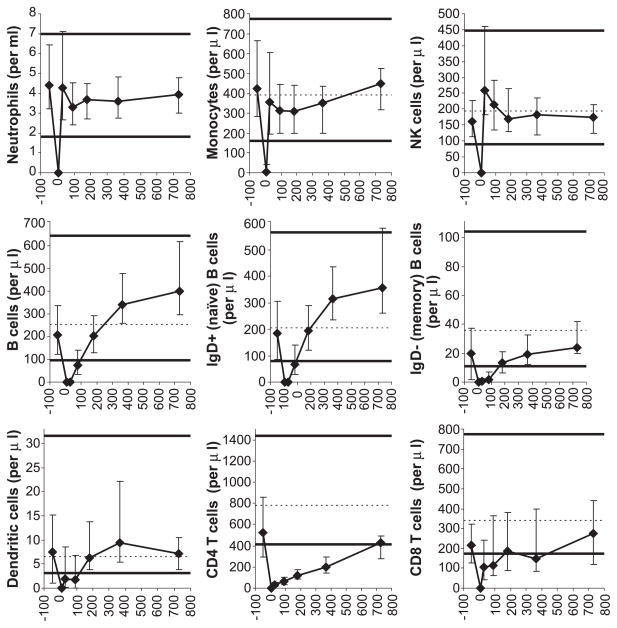

Fig. 1.

Recovery of leukocyte subsets. All horizontal axes display days posttransplant. Patient medians (diamonds) and 25th–75th percentiles (error bars) are shown. Normal medians are indicated by the dashed horizontal lines (except for neutrophils—not available). The thick horizontal lines denote the normal 5th and 95th percentiles (except for neutrophils—2.5th and 97.5th percentiles). Pretransplant studies are arbitrarily shown as day −50 studies. The following numbers of patient blood samples were analyzed: for neutrophils (by an automated hematology analyzer), 56 pretransplant, 49 on day 7, 49 at 1 month, 50 at 3 months, 34 at 6 months, 40 at 12 months, and 26 at 24 months posttransplant; for all other leukocyte subsets (by immunophenotyping), 47 pretransplant, 41 on day 7, 48 at 1 month, 41 at 3 months, 33 at 6 months, 36 at 12 months, and 17 at 24 months posttransplant.

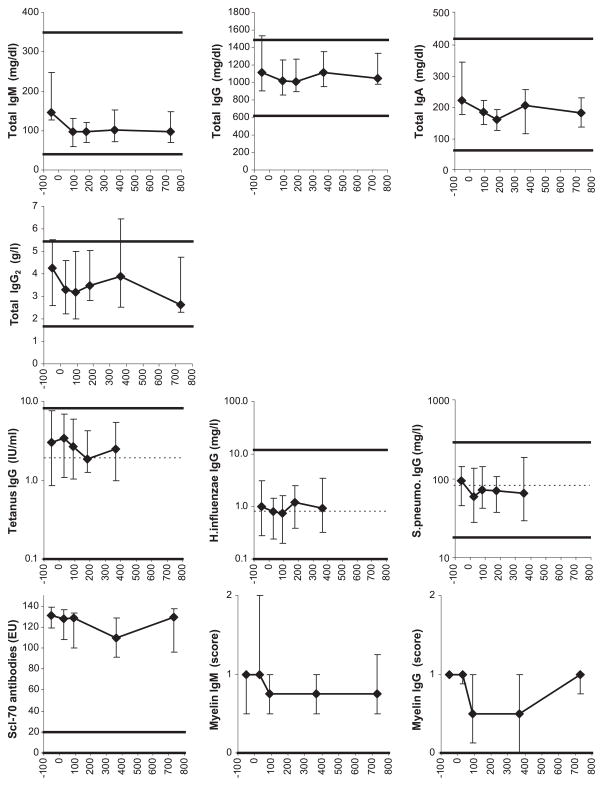

Fig. 4.

Serum antibody levels. For symbols, see Fig. 1 legend. For normal reference ranges, see Methods. Normal medians were not available for total IgM, IgG, IgA, and IgG2, and Scl-70 and myelin antibodies. The 24 months time point results are not displayed for the tetanus, H. influenzae, and S. pneumoniae-specific IgG levels because of inconsistent immunization between 12 and 24 months posttransplant. The numbers of patient serum samples analyzed were as follows: for total IgM, IgG and IgA, 23 pretransplant, 34 at 3 months, 18 at 6 months, 33 at 12 months, and 19 at 24 months posttransplant; for total IgG2 and tetanus/H. influenzae/S. pneumoniae-specific IgG, 42 pretransplant, 36 at 1 month, 38 at 3 months, 27 at 6 months, 37 at 12 months, and 14 at 24 months posttransplant; for Scl-70 antibodies, 6 pretransplant, 7 at 1 month, 7 at 3 months, 7 at 12 months, and 3 at 24 months posttransplant; for myelin IgM, 14 pretransplant, 11 at 1 month, 14 at 3 months, 10 at 12 months, and 4 at 24 months posttransplant; and for myelin IgG, 10 pretransplant, 8 at 1 month, 10 at 3 months, 9 at 12 months, and 4 at 24 months posttransplant.

Table 1.

Infection ratesa

| Time interval | Days 0–30 | Days 31–180 | Days 181–365 | Days 366–730 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substantially deficient components of immunity | Neutrophils, monocytes, NK cells, enterocytes (presumed), dendritic cells, B cells, CD8 T cells, CD4 T cells (median 0 on d7 and 33/μl on d30) | Dendritic cells, B cells, CD8 T cells, CD4 T cells (median 33/μl on d30 and 118/μl on d180) | CD4 T cells (median 118/μl on d180 and 194/μl on d365) | CD4 T cells (median 194/μl on d365 and 429/μl on d730) |

| Infection prophylaxis | Antiviralb, cephalosporin or Trim/sulfac, fluconazoled | Antiviralb, Trim/sulfac, Fluconazoled | Antiviralb, Trim/sulfac | None |

| Immuno-suppressive drugs | Prednisonee | Prednisone/Nonee | Nonee | None |

| Rate of total infections | 5.75 | 0.94 | 0.29 | 0.16 |

| Rate of severe infectionsf | 4.90 | 0.54 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| Rate of nonsevere infectionsg | 0.85 | 0.40 | 0.24 | 0.08 |

| Rate of documented infectionsh | 4.90 | 0.74 | 0.05 | 0.11 |

| Microorganisms causing the documented infectionsi | HSV (1) CMV (2) BKV (1) Gram+ (14) Gram-(5) |

HSV (1) VZV (3) EBV (2) Parainfl 3 (1) Gram+ (5) Gram− (3) |

VZV (1) | VZV (3) Gram+ (1) |

Each infection rate is expressed as the number of infections per 365 patient days, i.e., the number of infections in all patients occurring during the specified period divided by the number of days at risk and multiplied by 365. The numbers of days at risk (the sum of days at risk for each patient, i.e., the number of days from the beginning of the time period until the end of the time period or death, disease progression/relapse/pulmonary toxicity or loss to follow-up) were 1713 for days 0–30, 7407 for days 31–180, 7683 for days 181–365, and 13,514 for days 366–730. Presumed (clinical) respiratory tract infections were discounted (see Methods).

Typically acyclovir 800 mg twice a day orally or valacyclovir 500 mg twice a day orally until day 365. In addition, CMV pp65 antigenemia or plasma CMV DNAemia was monitored weekly until day 100 and then every other week until day 365. Ganciclovir was given to two patients without documented CMV disease preemptively. Documented CMV disease occurred in two patients (one had gastritis and one had gastritis+esophagitis+pneumonia).

Typically ceftazidime 2 g every 8 h intravenously during neutropenia <500/μl, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Trim/sulfa) 160/800 mg once a day orally from neutrophil engraftment until day 365.

Typically fluconazole 400 mg once a day orally until day 75.

Patients with systemic sclerosis typically received 0.5 mg kg−1 day−1 between days −6 and 30 with subsequent taper to day 60. Patients with multiple sclerosis typically received 0.5 mg kg−1 day−1 between days 7 and 21 with subsequent taper to day 30. One patient had a prolonged prednisone taper, reaching 10 mg/day at 6 months posttransplant. One patient restarted prednisone 85 mg/day at 5 months posttransplant for lymphocytic gastritis, and subsequently tapered, reaching 10 mg/day at 15 months posttransplant. One patient restarted prednisone 20 mg/day at 9 months posttransplant for pericarditis, and subsequently tapered, reaching 10 mg/day at 10 months posttransplant.

Treated inpatient.

Treated outpatient.

Infections with a known etiologic agent.

Numbers in parentheses denote the number of infections.

Abbreviations: HSV—herpes simplex virus; VZV—varicella-zoster virus; CMV—cytomegalovirus; EBV—Epstein–Barr virus; BKV—BK virus; Parainfl 3—parainfluenza 3 virus; Gram+—gram-positive bacteria; Gram− —gram negative bacteria.

For the determination of the normal reference ranges displayed in Figs. 1–4, for most assays, we studied blood from healthy adult volunteers (n = 104 for surface immunophenotyping, 27 for Ki67 intracellular immunophenotyping, 64 for TREC determination, 27 for spectratyping, and 65 for tetanus, Hemophilus influenzae, and S. pneumoniae IgG). Their median ages were similar to the median age of the patients (43 years for surface immunophenotyping, 43 for Ki67 intracellular immunophenotyping, 44 for TREC determination, 43 for spectratyping, and 43 for tetanus, H. influenzae, and S. pneumoniae IgG). For neutrophil counts and IgM, IgA, IgG, and IgG2 levels, we displayed the normal adult 2.5th–97.5th percentile range determined by the manufacturer of the instrument or kit used. For autoantibody levels, see “Antibody levels”. For normal thymic size (index), we used 22 adult patients of median age, 43 years, who had chest computer tomogram (CT) done for various reasons. They had no acute illness, congenital T cell deficiency, HIV disease, myasthenia gravis, hyperthyroidism, or malignancy, and were not treated with chemotherapy, radiation, or immunosuppressive drugs/systemic steroids. The rationale for displaying normal reference ranges in Figs. 1–4 in addition to patient pretransplant values is that the pretransplant values may be artificially low due to previous chemotherapy/immunosuppressive therapy [2,3]. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Immunophenotyping

Enumeration of mononuclear cell (MNC) subsets was performed as described [9]. Naïve CD4 T cells were defined as CD45RAhigh CD4 T cells because this subset contains thymic emigrants, and nearly all cord blood CD4 T cells are CD45RAhigh [10–12]. Naïve CD8 T cells were defined as CD11alow CD8 T cells because virtually all cord blood CD8 T cells are CD11alow and become CD11ahigh after activation [13,14]. Moreover, after hematopoietic cell transplantation, CD45RAhigh CD4 T cell counts correlate with TREC+ CD4 T cell counts, and CD11alow CD8 T cell counts correlate with TREC+ CD8 T cell counts [15]. Naïve B cells were defined as IgD+ B cells as most IgD+ B cells lack somatic mutations [16]. Monocytes were defined as CD14+ MNCs. NK cells were defined as MNCs expressing CD16 or CD56 and not expressing CD3 or CD14. Dendritic cells were defined as HLADRhigh MNCs not expressing CD3, CD14, CD16, CD20, CD34, or CD56. For the enumeration of Ki67+ CD4 or CD8 T cells, FACS Lysing Solution (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), 2.5 ml, was added to a pellet of up to 2 million blood MNCs (cryopreserved, as opposed to the above surface-only staining and flow cytometry performed on fresh MNCs). The cells were resuspended and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. After centrifugation, the cells were resuspended in 500 μl of 1× FACS Permeabilizing Solution and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Cells were washed in flow cytometry buffer (PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin and 0.1% sodium azide). After centrifugation and removal of supernatant by tube inversion, the cells were resuspended in the residual buffer (approximately 100 μl) and incubated for 30 min at 4°C with the following monoclonal antibody–fluorochrome conjugates: CD3-FITC, Ki67-PE, CD11A-APC, CD8-APCCy7, CD4-PerCp5.5, and CD45RA-ECD, or CD3-FITC, isotype control-PE, CD11A-APC, CD8-APCCy7, CD4-PecCp 5.5, and CD45RA-ECD (negative control). After washing with flow cytometry buffer, analysis was done on LSR-II cytometer (BD Biosciences). A minor portion of the immunophenotyping results has been published (the counts of total CD4 and CD8 T cells, B cells, and NK cells) [2,3].

Thymic size

Patients with systemic sclerosis had chest CT performed routinely pretransplant and at 1, 3, 12 months and annually posttransplant. Thymic index (a semiquantitative determination of thymic size) was determined as described by McCune et al. [17] except that a scale of 1–5 was used (1 denotes 0 or 1 of McCune’s scale). The determination was done by one radiologist (E.L.) blinded to patient demographic and clinical data. The numbers of CT studies analyzed were 17 pretransplant, 12 at 1 month, 20 at 3 months, 19 at 1 year, and 12 at 2 years posttransplant.

TREC assay

CD3+CD4+CD8− and CD3+CD4−CD8+ cells were sorted to >98% purity from Ficoll-separated MNCs, using Vantage flow sorter (BD Biosciences). A total of 50,000 CD4 or CD8 T cells were sorted into an Eppendorf tube. After centrifugation, supernatant was removed and the “dry” cell pellet was stored frozen (−80°C). Real-time PCR of the αδ signal joint was performed directly from lysate of the cell pellet, which was lysed in 100 μg/ml proteinase K. The 5′-nuclease (Taqman) assay was performed on 5 μl of cell lysate (total volume of the lysate of 50,000 cells was 40 μl; thus, 5 μl of the lysate contained TRECs from 6250 cells), using primers CACATCCCTTTCAACCATGCT and GCCAGCTGCAGGGTTTAGG and probe FAM-ACACCTCTGGTTTTTGTAAAGGTGCCCACT-TAMRA (MegaBases, Chicago, IL). PCR reaction contained 0.5 U Taq polymerase, 3.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 400 nM each primer, 200 nM probe, and Blue-636 reference (MegaBases). The reactions were run at 95°C/5 min, then at 95°C/30 s, and 60°C/60 s for 40 cycles, using ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detector (PE Biosystems, Norwalk, CT). Samples were analyzed in triplicates. Plasmids containing the αδ signal joint region were used as standards. A standard curve was plotted and the TREC level (the number of TREC copies per 6250 CD4 or CD8 T cells) was calculated using the ABI7700 software. The absolute count of TREC+ CD4 (CD8) T cells (per microliter of blood) was calculated as the TREC level (per 6250 cells) multiplied by the absolute CD4 (CD8) T cell count (per microliter) and divided by 6250.

Spectratyping

To maximize the likelihood of finding a low number of spectratype peaks in samples with low T cell diversity, Vβ-Jβ instead of Vβ-Cβ spectratyping was done. Because of the limited number of T cells available early posttransplant, we focused on only one Vβ family (arbitrarily Vβ17). To maximize sensitivity and specificity of the downstream PCR, Vβ17+CD4+CD8− and Vβ17+CD4−CD8+ cells were first sorted to >95% purity from Ficoll-separated MNCs, using Vantage flow sorter (BD Biosciences). A total of 2000 Vβ17+CD4 or Vβ17+CD8 T cells were sorted into solution D, prepared by mixing 7 μl β-mercaptoethanol (14.2 M) with 100 μl Lysis Buffer from Absolutely RNA Nanoprep kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). RNA was extracted using the Absolutely RNA Nanoprep kit, and cDNA was synthesized using Superscript II RNase H− Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and Oligo(dT)12–18 primers (Invitrogen). Each reverse transcription yielded 20 μl cDNA. Vβ17-Jβ1.2, Vβ17-Jβ1.4 or Vβ17-Jβ1.5 segments were separately amplified by PCR, using forward primer FAM-CAGAAAGGAGATATAGCTGAA (Vβ17) and reverse primer GTTAACCTGGTCCCCGAAC (Jβ1.2), AGACAGAGAGCTGGGTTCCA (Jβ1.4), or GGAGAGTCGAGTCCCATCA (Jβ1.5). PCR reactions were carried out in a 20-μl volume. Each reaction contained 5 μl cDNA, 1 U Platinum-Taq polymerase (Invitrogen), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 500 μM dNTPs, and 500 nM each primer. The reactions were run at 95°C/9 min, then at 94°C/30 s, 58°C/30 s, and 72°C/30 s for 35 cycles, and finally at 72°C/9 min. The dye-labeled PCR products were detected on an ABI 3100 sequence analyzer and the number of peaks was determined visually using GeneScan software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Note: per the ImMunoGe-neTics nomenclature [18], Vβ17 is TRBV19, Jβ1.2 is TRBJ1-2, Jβ1.4 is TRBJ1-4, and Jβ1.5 is TRBJ1-5.

Antibody levels

Serum levels of total IgM, IgA, and IgG were determined in local clinical laboratories, typically by nephelometry (our clinical laboratory used a kit from Dade Behring, Marburg, Germany). Levels of total IgG2 and IgG specific for tetanus toxoid, H. influenzae capsular polysaccharide and pneumococcal polysaccharides were determined in our laboratory as described [19], using ELISA kits from The Binding Site (Birmingham, U.K.). Tetanus, H. influenzae, and S. pneumoniae IgG levels were not analyzed at 2 years because some patients were vaccinated against tetanus, H. influenzae and S. pneumoniae between 1 and 2 years posttransplant, and data on the timing of vaccination and the number of vaccine doses were not available. Scl-70 antibodies were analyzed only in patients who had these antibodies pretransplant, or, if the pretransplant sample was missing, in the first 3 months posttransplant (n = 6 pretransplant, 7 at 1 month, 7 at 3 months, 7 at 12 months, and 3 at 24 months posttransplant). Scl-70 antibodies were determined by ELISA using a kit from BioRad/Helix Diagnostics (West Sacramento, CA). The normal reference range in Fig. 4 is displayed as 0–20 enzyme units (EU) as per the manufacturer of the kit; levels >20 EU are defined as abnormal. Myelin antibodies (against either myelin basic protein or myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein) were determined in patients with multiple sclerosis who had these antibodies pretransplant, or, if the pretransplant sample was missing, in the first 3 months posttransplant (n = 14/10 [IgM/IgG] pretransplant, 11/8 at 1 month, 14/10 at 3 months, 10/9 at 12 months, and 4/4 at 24 months posttransplant) by Western blot as described [20,21]. As controls, monoclonal antibodies to myelin basic protein (MAB381, Chemicon, Temecula, CA) and myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (8.18-C5 [22]) and a positive and a negative human control sera were used. The levels were semiquantitatively scored by a blinded investigator as negative (0), marginally positive (0.5), weakly positive (1), moderately positive (2), or strongly positive (3). If a patient had antibodies against both myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein and myelin basic protein, the higher score (of the two antibodies) was used for analysis. The normal reference (5th–95th percentile) range displayed in Fig. 4 is 0–0, as 97% normal adults have undetectable myelin antibodies (Berger, unpublished).

Infections

Documented infection was defined as an illness with symptoms and signs consistent with an infection and microbiological documentation of a pathogen, except for dermatomal zoster where the clinical diagnosis was considered sufficient. Microbiological documentation included isolation of the pathogen by culture from a sterile site or a nonsterile site (if from a nonsterile site, the organism had to be clinically judged as pathogenic) or histological/immunohistological evidence. Presence of a microorganism in blood by culture (not by antigen or nucleic acid detection) was counted as a documented infection even in the absence of symptoms or signs of infection. Clinical (presumed) infection (without an identified microorganism) was defined as illness with symptoms and signs consistent with an infection; however, presumed respiratory tract infections were discounted because they could not be reliably distinguished from allergy; hemorrhagic cystitis was also discounted because it could not be differentiated from conditioning regimen-induced cystitis. Fever of presumed infectious etiology was counted only if >38.5°C and if it responded to antibiotics within 3 days. A chronic infection was counted as one infection. A recurrent infection was counted as multiple infections only if the episodes were clearly separated by >4-week asymptomatic period. A polymicrobial infection of one organ or several adjacent organs was counted as one infection (due to the organism that was considered the major pathogen). Infections with one microorganism in two nonadjacent organs were counted as two infections. Respiratory tract was considered adjacent to paranasal sinuses and lungs. Lungs and paranasal sinuses were considered nonadjacent. An organ infection with viremia/bacteremia/fungemia was counted as one infection. Severe infections were defined as infections treated in a hospital. Nonsevere infections were treated in an outpatient setting.

Statistics

Significance of differences in laboratory parameters of immunity between healthy volunteers and patients at each time point were tested using Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon rank sum test. In Figs. 1–4, whenever a patient median falls on or outside of the 5th–95th percentile range, the difference is significant (P < 0.05, two-tailed), except for thymic index pretransplant and at 1 and 3 months posttransplant (P > 0.05) and for neutrophil counts and IgM, IgG, IgA, and Scl-70 antibody levels (the significance was not tested because the individual reference group data were not available to us). The information on the significance of differences between patients and normals is not presented in Figs. 1–4 to avoid information congestion. Significance of differences in thymic size (index) between <43-year-old and ≥43-year-old patients at each time point was tested by the Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon rank sum test. Significance of the difference in the percentage of Ki67+ cells among CD4 vs. CD8 T cells was also tested by the Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon rank sum test. Significance of correlation between patient age and a laboratory parameter of immunity was tested by Spearman test. Significance of difference between <43- and ≥43-year-old patients in the infection rates (tabulated as the number of days at risk with and without a newly diagnosed infection) was tested by the χ2 test.

Results

Immune cells

Median leukocyte (WBC) count measured by an automated hematology analyzer reached a nadir of 20/μl on day 5. On day 7, it was 50/μl, and virtually all leukocytes were mononuclear cells (MNCs). By flow cytometry, median 75.6% of the MNCs were monocytes, 19.5% NK cells, 0.6% T cells, and 0.2% B cells.

Innate immune cell (neutrophil, monocyte, and NK cell) counts returned to the normal range by 1 month posttransplant. B cell counts recovered by 6 months posttransplant. Memory B cell counts recovered more slowly than naïve B cell counts. This may be because naïve B cells only differentiated into memory B cells after encountering their cognate antigens. Dendritic cell counts recovered by 6 months posttransplant. T cells showed the slowest recovery—CD8 T cell counts were borderline low at 6 and 12 months and returned back to normal by 2 years, and CD4 T cell counts reached borderline low normal levels only at 2 years posttransplant (Fig. 1).

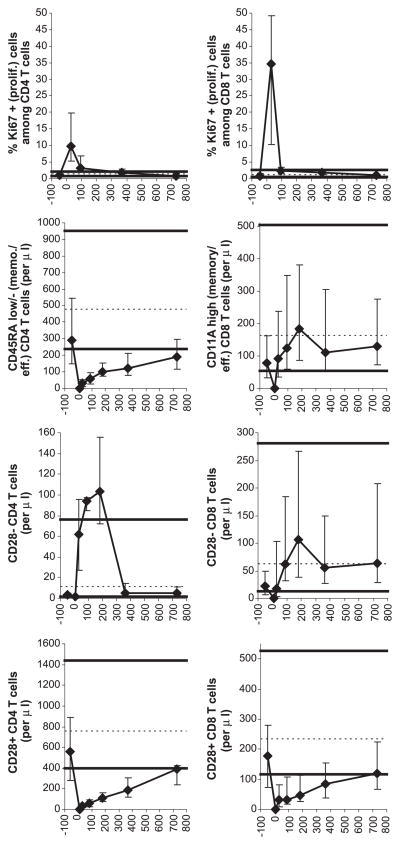

T cell recovery was studied in detail (Figs. 2 and 3). Peripheral expansion, assessed by the percentage of Ki67+ (proliferating) T cells, was robust early posttransplant, particularly for CD8 T cells. At 1 month posttransplant, median 10% CD4 T cells and 35% CD8 T cells were Ki67+ (normal ≤ 3%). The difference in the percentage of Ki67+ cells among CD4 vs. CD8 T cells at 1 month was statistically significant (P = 0.01). The difference was important as memory/effector CD8 T cell counts recovered to normal within 1 month posttransplant whereas memory/effector CD4 T cell counts remained low for at least 2 years (Fig. 2). The relative insufficiency of the peripheral expansion of CD4 T cells could be due not only to decreased proliferation (compared to that of CD8 T cells) but also shorter survival. Indirect evidence for a contribution of the latter mechanism is that abnormally high numbers of CD28− CD4 T cells were generated in the first several months posttransplant (Fig. 2). CD28− T cells have short telomeres and thus presumed short life span [23,24].

Fig. 2.

Recovery of T cell subsets. For symbols and the numbers of patient samples analyzed, see Fig. 1 legend.

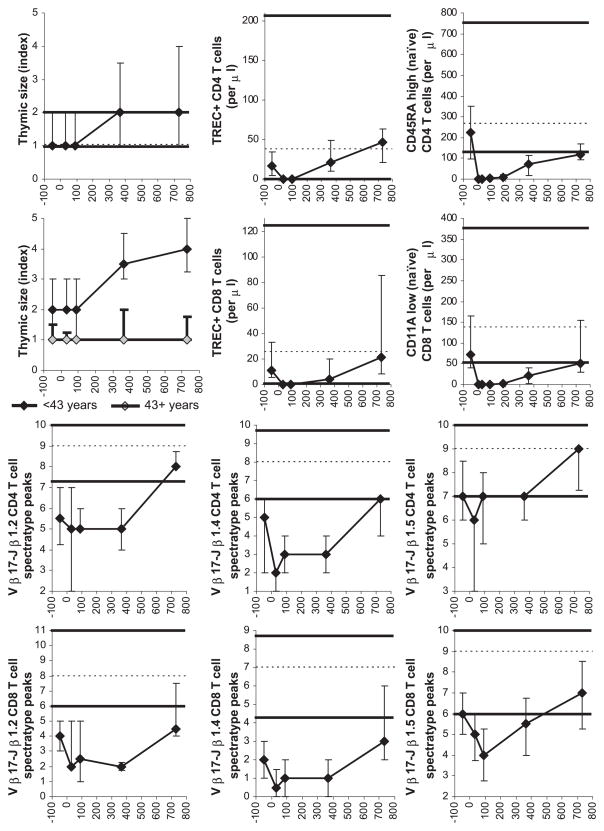

Fig. 3.

Thymic size and recovery of T cell subsets and diversity. For symbols, see Fig. 1 legend. The numbers of patient CT studies and blood samples analyzed were as follows: for the thymic index, 17 pretransplant, 12 at 1 month, 20 at 3 months, 19 at 1 year, and 12 at 2 years posttransplant; for TRECs, 28 pretransplant, 33 at 1 month, 22 at 3 months, 23 at 12 months, and 9 at 24 months posttransplant; for phenotypically naïve T cells, 47 pretransplant, 41 on day 7, 48 at 1 month, 41 at 3 months, 33 at 6 months, 36 at 12 months, and 17 at 24 months posttransplant; and for spectratyping, 27 pretransplant, 21 at 1 month, 21 at 3 months, 17 at 12 months, and 10 at 24 months posttransplant. In the top left graph on thymic size, both the low normal limit (5th percentile) and the median are 1 (for clarity, the low normal limit is displayed as 0.97 and the median as 1.03).

De novo generation (thymopoiesis) contributed significantly to increasing T cell counts at >3 months posttransplant. An increase in thymic size from baseline and an increase in TREC+ T cells from a median of zero were first detected between 3 and 12 months, and TREC+ T cell counts continued to rise between 1 and 2 years posttransplant (Fig. 3). This coincided with increasing numbers of phenotypically naïve T cells and increasing T cell diversity assessed by the number of T cell receptor β-chain spectratyping peaks (Fig. 3). De novo generation was age-dependent. Thymic hypertrophy was detectable by CT at 1 and 2 years posttransplant in <43-year-old but not in ≥ 43-year-old patients [Fig. 3; the difference in thymic size was statistically significant at 1 year (P = 0.01) and 2 years (P = 0.03) posttransplant]. There were also trends toward an inverse correlation between patient age and the counts of TREC+ CD4 and CD8 T cells, phenotypically naïve CD4 and CD8 T cells, and total CD4 (but not CD8) T cells at 1 and 2 years posttransplant and the number of spectratyping peaks at 2 years posttransplant (data not shown). Statistical significance of the inverse correlation was reached for phenotypically naïve CD4 (R = −0.45, P = 0.007) and phenotypically naïve CD8 (R = −0.38, P = 0.02) T cells at 1 year posttransplant and for Vβ17-Jβ1.5 CD8 spectratyping peaks at 2 years posttransplant (R = −0.71, P = 0.02). Interestingly, although thymic hypertrophy was not detected by CT in most ≥ 43-year-old patients, an increase in TREC+ CD4 and CD8 T cell counts, though smaller than in <43-year-old patients, occurred after 3 months posttransplant in all ≥43-year-old patients measured (data not shown).

Antibodies

Even though B cell and CD4 T cell counts were very low in the first 3 months posttransplant, median serum levels of total IgM, IgA, IgG, IgG2 as well as IgG specific for tetanus toxoid, H. influenzae, and S. pneumoniae remained normal (Fig. 4). Median levels of autoantibodies against Scl-70 and myelin continued to be abnormally high throughout the 2-year follow-up (Fig. 4).

Infections

As expected, infections were frequent in the first month, when multiple components of immunity were abnormal. Surprisingly, infections between day 31 and 730 were infrequent in spite of the profound initial lymphopenia (in particular CD4 lymphopenia) (Table 1). Two fatal infections occurred, both due to Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-associated lymphoproliferation at approximately 2 months posttransplant. These occurred in two patients who at 1 month posttransplant had undetectable T cells (at that time point, 4/48 patients analyzed by immunophenotyping had undetectable T cells whereas the remaining 44 patients had detectable T cells). Details on these two patients were previously reported [25].

Day 181–730 infections attributable to T-lymphopenia (as counts of other immune cells have recovered by day180) occurred with a low frequency of 0.21 total infections per patient year (0.07 severe infections and 0.09 documented infections per patient year). The day 181–730 total infections were less frequent in <43-year-old patients than in ≥43-year-old patients (0.07 vs. 0.36 per patient year, P = 0.03). There were no statistically significant differences in the day 181–730 total infection rates between patients with above vs. below median values of CD4 or CD8 T cell counts, naïve CD4 or CD8 T cell counts, TREC+ CD4 or CD8 T cell counts, or numbers of CD4 or CD8 spectratype peaks (average of the 3 families measured) at 1 year posttransplant. However, the power to detect these differences at a statistically significant level was lower than the power to detect the difference in infection rates between the <43- and ≥43-year-old patients—the laboratory parameters at 1 year posttransplant were available for only ≤36 patients, whereas the data on infections and age were available for all 44 patients surviving without relapse/disease progression/pulmonary toxicity beyond day 180.

Discussion

In agreement with published reports on recovery from moderate leukopenia (reviewed in Refs. [26–29]), we found that following severe leukopenia (particularly lymphopenia) induced by cyclophosphamide, total body irradiation, and ATG, cells of innate immunity recovered first, followed by B cells, and then T cells. T cell recovery was biphasic. Peripheral expansion dominated in the first 3 months, whereas thymopoiesis contributed to increasing T cell counts and diversity later posttransplant. The novel findings of this study (discussed below) are that the severe lymphopenia was not associated with a substantial decline in antibody levels, and that infections attributable to CD4 T lymphopenia were rare.

This study highlighted an important difference between CD4 and CD8 T cells in their ability to undergo homeostatic peripheral expansion. For CD8 T cells, the expansion was so robust that normal memory/effector CD8 T cell counts were reached by 1 month. For CD4 T cells, the expansion was only moderate, and normal memory/effector CD4 T cell counts were not reached by 2 years. The fact that CD8 T cell counts recover faster than CD4 T cell counts has been known [26,27,29]; the novel finding of our study is that the faster CD8 T cell recovery is due to the robust peripheral expansion. Viral infections typically result in a far greater expansion of CD8 than CD4 T cells [30]. Perhaps, reactivating endogenous pathogens (e.g., herpesviruses) or exogenous pathogens stimulate the preferential expansion of CD8 cells. Consistent with that, in â2microglobulin-deficient mice whose CD8 T cells cannot be stimulated by cognate antigens (peptides), expansion of CD8 T cells after radiation-induced lymphopenia did not occur [31].

The peripherally expanded T cells early posttransplant likely originated from the few pretransplant T cells that survived the conditioning or were infused with the graft rather than from de novo generation. Though low in number, T cells were typically detectable in the blood on day 7 (median 0.3/μl), indicating that some T cells survived or were reinfused. T cells generated de novo from the grafted CD34 cells were not expected to exist on day 7 as thymocyte precursor to T cell differentiation takes at least 12 days [32]. Moreover, at 1 month posttransplant, 82% patients had undetectable TRECs.

Our study more closely reflects the “natural” homeostatic recovery of lymphocytes. Unlike in other studies, our patients were not influenced by HIV, cancer, GVHD, or drugs potentially influencing the immune recovery (except for low-dose prednisone in the first 2 months posttransplant). However, it is theoretically possible that our patients had an autoimmune disease-associated defect of a lymphopoietic organ. Such a defect has not been described in humans with multiple sclerosis or systemic sclerosis, but thymic histological abnormalities have been described in an avian model of systemic sclerosis [33]. To minimize the potential impact of the underlying disease on the immune recovery, we censored our patients at the time of disease progression/relapse. Moreover, there was no significant difference in the counts of TREC+ CD4 or CD8 T cells at 1 or 2 years posttransplant between patients with multiple sclerosis and those with systemic sclerosis (median 14 vs. 38/ìl at 1 year and 21 vs. 59 at 2 years for CD4 cells, and 3 vs. 7/ìl at 1 year and 7 vs. 23 at 2 years for CD8 cells), suggesting against a thymic defect in patients with systemic sclerosis. Also, a substantial impact of the underlying disease in our study is unlikely as the tempo of recovery of lymphocyte subsets in our patients recovering from extreme (radiochemotherapy and ATG-induced) lymphopenia was similar to the tempo of recovery in patients recovering from moderate (radio/chemotherapy-induced) lymphopenia [26,27,29,34–36].

Surprisingly, antibody levels did not drop substantially, in spite of the severe CD4 T and B lymphopenia during the first several months posttransplant. Consistent with that, oligoclonal immunoglobulins in the cerebrospinal fluid of most multiple sclerosis patients treated with autologous transplantation did not disappear [3,37,38]. As the half life of IgM and IgA is only ~5 days and that of IgG only ~23 days [39], the antibodies detected in the sera of our patients were continuously produced, presumably by plasma cells generated pretransplant. Plasma cells are radiation-resistant and long-lived [40–42]. The persistent antibody production does not appear to require posttransplant exposure of patients to the cognate antigens. Tetanus IgG levels in the first posttransplant year remained stable, even though the patients were not vaccinated in the first year and natural exposure to tetanus toxin in developed countries is extremely unlikely [43]. However, it is unclear whether this applies to other autologous transplant settings. In three studies presenting tetanus antibody levels after autologous transplantation for malignancies, the levels appeared to drop between pretransplant and 1 year posttransplant [44–46].

From the infectious disease point of view, the persistent production of antibodies by plasma cells generated before the autologous transplantation may be beneficial, as most frequent pathogens are likely encountered pretransplant. Unfortunately, from the point of view of autoimmune diseases caused by autoantibodies like pemphigus (anti-desmoglein) or Lambert–Eaton myasthenic syndrome (anti-voltage gated calcium channel), the persistent production of autoantibodies may be deleterious. This may not apply to systemic sclerosis or multiple sclerosis in which the role of autoantibodies is uncertain. It is unlikely that the diseases caused by autoantibodies would be cured by autologous transplantation. In contrast, allogeneic transplantation might cure such diseases as it is associated with graft-vs.-host plasma cell reaction [47–49]. However, attempts to treat such diseases with autologous transplantation may still be warranted for the following two reasons: First, contrary to our observation, in five of six systemic lupus patients, double-stranded DNA antibodies became undetectable after autologous transplantation [50]. Second, clinical improvement may occur even if the autoantibody thought to cause the disease persists. In two of two myasthenia gravis patients, symptoms markedly improved after high-dose chemotherapy in spite of persisting acetylcholine receptor antibodies [51].

Clinical manifestations of the lymphopenia following the extreme lymphoablation were surprisingly mild, when compared to other settings of a similar degree of lymphopenia. In the first 6 months after transplant, when median CD4 T cell counts ranged from <1 to 118/μl, infections that were not covered by prophylactic antimicrobial drugs and would be expected to occur in AIDS patients with a similar degree of lymphopenia (cryptosporidiosis, Kaposi sarcoma, mycobacteriosis [52]) did not occur. Between 1 and 2 years posttransplant, when no prophylactic antimicrobial drugs were given, the incidence of infections (excluding presumed respiratory tract infections) was 16% (Table 1), whereas in HIV-seropositive individuals with similar CD4 T cell counts (200–450/μl) not receiving antimicrobial drugs, the annual incidence of oral candidiasis alone was 16–26% and that of other infections (excluding respiratory tract infections) was 16–19% [53–55]. This may be attributed to the fact that HIV infects not only CD4 T cells but also other immune cells (e.g., monocytes/macrophages, dendritic cells) [56]. The infection rates in the autologous transplant recipients presented here were also markedly lower than in allogeneic transplant recipients. Between day 30 and 365 after allogeneic marrow transplantation, when median CD4 counts ranged between 76 and 185/μl, the infection rate was 3.17 per patient year [9] compared to 0.94 per patient year between day 31 and 180 (median CD4 counts 33–118/μl) or 0.29 per patient year between day 181 and 365 (median CD4 counts 118–193/μl) in the autologous transplant recipients (Table 1), using similar definitions of infections and similar infection prophylaxis. This may be because after allogeneic transplantation T and B cells are not only quantitatively deficient but also dysfunctional due to GVHD or its treatment [57]. Congenital severe T cell deficiency with or without B cell deficiency is fatal (unless cured with allogeneic transplantation or gene therapy) [58], whereas only 2 of the 56 autologous transplant recipients died due to an infection (EBV lymphoproliferation). This may be because in contrast to the patients with congenital severe lymphopenia, in our autologous transplant recipients, the severe lymphopenia was only transient and that the patients had normal levels of antibodies against recall antigens (presumably against most frequent pathogens, which they had encountered before transplantation). Collectively, iatrogenic transient severe lymphopenia is relatively well tolerated (using the prophylactic antimicrobial strategy described in Table 1). Thus, attempts to treat autoimmune diseases with therapies causing short-term severe lymphoablation are relatively safe, at least from the infectious disease point of view. In the future, the severe lymphopenia may be even better tolerated if EBV DNAemia and EBV-specific T cell counts are monitored and rituximab is given preemptively (however, antibody responses to bacteria encountered posttransplant may be impaired in the patients treated with rituximab) [59,60].

In conclusion, peripheral expansion is highly efficient for CD8 but not CD4 T cells. The prolonged CD4 lymphopenia is associated with few infections, possibly due to antibodies produced by plasma cells persisting from pretransplant, suggesting that autologous transplantation using extremely lymphoablative conditioning is relatively safe. The persistent antibody production raises a concern that autoimmune diseases caused by autoantibodies may not be cured by autologous transplantation.

Acknowledgments

We thank other investigators participating in the study of autografting for autoimmune diseases for facilitating the blood draws and shipments, including Drs. Steven Pavletic, Man-soo Park, Jinan Al-Omaishi, John Corboy, John DiPersio, Fred LeMaistre, Harry Openshaw, Leslie Crofford, Roger Dansey, Maureen Mayes, Kevin McDonagh, C.S. Chen, Ken Russel, and John Rambharose. We greatly acknowledge research nurses and coordinators involved in this study, especially Kathy Prather, Julie Lee, and Gretchen Henstorf. We are grateful to Roxanne Velez and Dr. Ansamma Joseph for excellent technical assistance.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants no. AI46108, CA18029, AI33484, CA15704, and HL36444, and contract no. AI05419.

References

- 1.McSweeney PA. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for severe autoimmune diseases. In: Broudy VC, Prchal JT, Tricot GJ, editors. Hematology 2003 (Education Program Book of the American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting) American Society of Hematology; San Diego: 2003. pp. 379–387. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McSweeney PA, Nash RA, Sullivan KM, et al. High-dose immunosuppressive therapy for severe systemic sclerosis: initial outcomes. Blood. 2002;100:1602–1610. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nash RA, Bowen JD, McSweeney PA, et al. High-dose immunosuppressive therapy and autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for severe multiple sclerosis. Blood. 2003;102:2364–2372. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonyhadi ML, Rabin L, Salimi S, et al. HIV induces thymus depletion in vivo. Nature. 1993;363:728–732. doi: 10.1038/363728a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKallip RJ, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti PS. Immunotoxicity of AZT: inhibitory effect on thymocyte differentiation and peripheral T cell responsiveness to gp120 of human immunodeficiency virus. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1995;131:53–62. doi: 10.1006/taap.1995.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukushi N, Arase H, Wang B, et al. Thymus: a direct target tissue in graft-versus-host reaction after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation that results in abrogation of induction of self-tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:6301–6305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ritter MA, Ladyman HM. The effects of cyclosporine on the thymic microenvironment and T cell development. In: Kendall MD, editor. Thymus Update 4 The Thymus in Immunotoxicology. Harwood Academic Press; Chur: 1991. pp. 157–176. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Storek J, Wells D, Dawson MA, Storer B, Maloney DG. Factors influencing B lymphopoiesis after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2001;98:489–491. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.2.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Storek J, Dawson MA, Storer B, et al. Immune reconstitution after allogeneic marrow transplantation compared with blood stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2001;97:3380–3389. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Douek DC, McFarland RD, Keiser PH, et al. Changes in thymic function with age and during the treatment of HIV infection. Nature. 1998;396:690–695. doi: 10.1038/25374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dumont-Girard F, Roux E, van Lier RA, et al. Reconstitution of the T-cell compartment after bone marrow transplantation: restoration of the repertoire by thymic emigrants [In Process Citation] Blood. 1998;92:4464–4471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Storek J, Witherspoon RP, Storb R. T cell reconstitution after bone marrow transplantation into adult patients does not resemble T cell development in early life. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;16:413–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okumura M, Fujii Y, Inada K, Nakahara K, Matsuda H. Both CD45RA+ and CD45RA−subpopulations of CD8+T cells contain cells with high levels of lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 expression, a phenotype of primed T cells. J Immunol. 1993;150:429–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okumura M, Fujii Y, Takeuchi Y, Inada K, Nakahara K, Matsuda H. Age-related accumulation of LFA-1high cells in a CD8+CD45RA high T cell population. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:1057–1063. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Storek J, Joseph A, Dawson MA, Douek DC, Storer B, Maloney DG. Factors influencing T-lymphopoiesis after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;73:1154–1158. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200204150-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein U, Kuppers R, Rajewsky K. Human IgM+IgD+ B cells, the major B cell subset in the peripheral blood, express V-kappa genes with no or little somatic mutation throughout life. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:3272–3277. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830231232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCune JM, Loftus R, Schmidt DK, et al. High prevalence of thymic tissue in adults with human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2301–2308. doi: 10.1172/JCI2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lefranc MP, Lefranc G. The T Cell Receptor Facts Book. Academic Press; San Diego: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Storek J, Viganego F, Dawson MA, et al. Factors affecting antibody levels after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2003;101:3319–3324. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berger T, Rubner P, Schautzer F, et al. Antimyelin antibodies as a predictor of clinically definite multiple sclerosis after a first demyelinating event. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:139–145. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reindl M, Linington C, Brehm U, et al. Antibodies against the myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein and the myelin basic protein in multiple sclerosis and other neurological diseases: a comparative study. Brain. 1999;122(Pt 11):2047–2056. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.11.2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linington C, Bradl M, Lassmann H, Brunner C, Vass K. Augmentation of demyelination in rat acute allergic encephalomyelitis by circulating mouse monoclonal antibodies directed against a myelin/oligodendrocyte glycoprotein. Am J Pathol. 1988;130:443–454. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monteiro J, Batliwalla F, Ostrer H, Gregersen PK. Shortened telomeres in clonally expanded CD28−CD8+ T cells imply a replicative history that is distinct from their CD28+CD8+ counterparts. J Immunol. 1996;156:3587–3590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee WW, Nam KH, Terao K, Yoshikawa Y. Age-related telomere length dynamics in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of healthy cynomolgus monkeys measured by Flow FISH. Immunology. 2002;105:458–465. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nash RA, Dansey R, Storek J, et al. Epstein–Barr virus-associated posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder after high-dose immunosuppressive therapy and autologous CD34-selected hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for severe autoimmune diseases. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003;9:583–591. doi: 10.1016/s1083-8791(03)00228-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parkman R, Weinberg KI. Immunological reconstitution following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. In: Blume KG, Forman SJ, Appelbaum FR, editors. Thomas’s Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Blackwell Science; Malden: 2003. pp. 853–861. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Storek J, Witherspoon RP. Immunological reconstitution after hemopoietic stem cell transplantation. In: Atkinson K, Champlin R, Ritz J, Fibbe WE, Ljungman P, Brenner MK, editors. Clinical Bone Marrow and Blood Stem Cell Transplantation. Cambridge Univ. Press; Cambridge: 2003. pp. 194–226. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sempowski GD, Haynes BF. Immune reconstitution in patients with HIV infection. Annu Rev Med. 2002;53:269–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.104032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mackall CL. T-cell immunodeficiency following cytotoxic antineoplastic therapy: a review. Stem Cells. 2000;18:10–18. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.18-1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rouse T, Ahmed R. Immune response to viruses. In: Rich RR, Fleisher TA, Shearer WT, Kotzin BL, Schroeder HWJ, editors. Clinical Immunology. Mosby; London: 2001. pp. 28.10–28.21. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mackall CL, Bare CV, Granger LA, Sharrow SO, Titus JA, Gress RE. Thymic-independent T cell regeneration occurs via antigen-driven expansion of peripheral T cells resulting in a repertoire that is limited in diversity and prone to skewing. J Immunol. 1996;156:4609–4616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scollay R, Godfrey DI. Thymic emigration: conveyor belts or lucky dips? Immunol Today. 1995;16:268–273. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80179-0. (discussion 273–264) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boyd RL, Wilson TJ, Van de Water J, Haapanen LA, Gershwin ME. Selective abnormalities in the thymic microenvironment associated with avian scleroderma, an inherited fibrotic disease. J Autoimmun. 1991;4:369–380. doi: 10.1016/0896-8411(91)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malphettes M, Carcelain G, Saint-Mezard P, et al. Evidence for naive T-cell repopulation despite thymus irradiation after autologous transplantation in adults with multiple myeloma: role of ex vivo CD34+ selection and age. Blood. 2003;101:1891–1897. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Douek DC, Vescio RA, Betts MR, et al. Assessment of thymic output in adults after haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation and prediction of T-cell reconstitution [see comments] Lancet. 2000;355:1875–1881. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02293-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mackall CL, Stein D, Fleisher TA, et al. Prolonged CD4 depletion after sequential autologous peripheral blood progenitor cell infusions in children and young adults. Blood. 2000;96:754–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saiz A, Carreras E, Berenguer J, et al. MRI and CSF oligoclonal bands after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in MS. Neurology. 2001;56:1084–1089. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.8.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Openshaw H, Lund BT, Kashyap A, et al. Peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in multiple sclerosis with busulfan and cyclophosphamide conditioning: report of toxicity and immunological monitoring. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2000;6:563–575. doi: 10.1016/s1083-8791(00)70066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schroeder HWJ, Torres RM. B-cell antigen receptor genes, gene products and coreceptors. In: Rich RR, Fleisher TA, Shearer WT, Kotzin BL, Schroeder HWJ, editors. Clinical Immunology. Mosby; London: 2001. pp. 4.1–4.10. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller JJ, Cole LJ. The radiation resistance of long-lived lymphocytes and plasma cells in mouse and rat lymph nodes. J Immunol. 1967;98:982–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ochs HD, Storb R, Thomas ED, et al. Immunologic reactivity in canine marrow graft recipients. J Immunol. 1974;113:1039–1053. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Slifka MK, Antia R, Whitmire JK, Ahmed R. Humoral immunity due to long-lived plasma cells. Immunity. 1998;8:363–372. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80541-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takahashi M, Komiya T, Fukuda T, et al. A comparison of young and aged populations for the diphtheria and tetanus antitoxin titers in Japan. Jpn J Med Sci Biol. 1997;50:87–95. doi: 10.7883/yoken1952.50.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hammarstrom V, Pauksen K, Svensson H, et al. Serum immunoglobulin levels in relation to levels of specific antibodies in allogeneic and autologous bone marrow transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2000;69:1582–1586. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200004270-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hammarstrom V, Pauksen K, Bjorkstrand B, Simonsson B, Oberg G, Ljungman P. Tetanus immunity in autologous bone marrow and blood stem cell transplant recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;22:67–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gandhi MK, Egner W, Sizer L, et al. Antibody responses to vaccinations given within the first two years after transplant are similar between autologous peripheral blood stem cell and bone marrow transplant recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;28:775–781. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Badros A, Tricot G, Toor A, et al. ABO mismatch may affect engraftment in multiple myeloma patients receiving nonmyeloablative conditioning. Transfusion. 2002;42:205–209. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2002.00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee JH, Choi SJ, Kim S, et al. Changes of isoagglutinin titres after ABO-incompatible allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Br J Haematol. 2003;120:702–710. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mielcarek M, Leisenring W, Torok-Storb B, Storb R. Graft-versus-host disease and donor-directed hemagglutinin titers after ABO-mismatched related and unrelated marrow allografts: evidence for a graft-versus-plasma cell effect. Blood. 2000;96:1150–1156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Traynor AE, Schroeder J, Rosa RM, et al. Treatment of severe systemic lupus erythematosus with high-dose chemotherapy and haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation: a phase I study. Lancet. 2000;356:701–707. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02627-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Drachman DB, Jones RJ, Brodsky RA. Treatment of refractory myasthenia: “rebooting” with high-dose cyclophosphamide. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:29–34. doi: 10.1002/ana.10400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crowe SM, Carlin JB, Stewart KI, Lucas CR, Hoy JF. Predictive value of CD4 lymphocyte numbers for the development of opportunistic infections and malignancies in HIV-infected persons. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1991;4:770–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaslow RA, Phair JP, Friedman HB, et al. Infection with the human immunodeficiency virus: clinical manifestations and their relationship to immune deficiency. A report from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107:474–480. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-4-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moss AR, Bacchetti P, Osmond D, et al. Seropositivity for HIV and the development of AIDS or AIDS related condition: three year follow up of the San Francisco General Hospital cohort. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988;296:745–750. doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6624.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Selwyn PA, Alcabes P, Hartel D, et al. Clinical manifestations and predictors of disease progression in drug users with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1697–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212103272401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.D’Souza MP, Fauci AS. Immunopathogenesis. In: Merigan TCJ, Bartlett JG, Bolognesi D, editors. Textbook of AIDS Medicine. Williams and Wilkins; Baltimore: 1999. pp. 59–85. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hakim FT, Mackall CL. The immune system: effector and target of GVHD. In: Ferrara JLM, Deeg HJ, Burakoff SJ, editors. Graft-vs-Host Disease. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1997. pp. 257–289. [Google Scholar]

- 58.LeDeist F, Fisher A. Primary T-cell Immunodeficiencies. In: Rich RR, Fleisher TA, Whearer WT, Kotzin BL, Schroeder HWJ, editors. Clinical Immunology. Mosby; London: 2001. pp. 35.25–35.31. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meij P, van Esser JW, Niesters HG, et al. Impaired recovery of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-specific CD8+T lymphocytes after partially T-depleted allogeneic stem cell transplantation may identify patients at very high risk for progressive EBV reactivation and lymphoproliferative disease. Blood. 2003;101:4290–4297. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Esser JW, Niesters HG, van der Holt B, et al. Prevention of Epstein–Barr virus-lymphoproliferative disease by molecular monitoring and preemptive rituximab in high-risk patients after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2002;99:4364–4369. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]