Abstract

In anticipation of the impending revision of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, APA’s Publications and Communications Board formed the Working Group on Journal Article Reporting Standards (JARS) and charged it to provide the board with background and recommendations on information that should be included in manuscripts submitted to APA journals that report (a) new data collections and (b) meta-analyses. The JARS Group reviewed efforts in related fields to develop standards and sought input from other knowledgeable groups. The resulting recommendations contain (a) standards for all journal articles, (b) more specific standards for reports of studies with experimental manipulations or evaluations of interventions using research designs involving random or nonrandom assignment, and (c) standards for articles reporting meta-analyses. The JARS Group anticipated that standards for reporting other research designs (e.g., observational studies, longitudinal studies) would emerge over time. This report also (a) examines societal developments that have encouraged researchers to provide more details when reporting their studies, (b) notes important differences between requirements, standards, and recommendations for reporting, and (c) examines benefits and obstacles to the development and implementation of reporting standards.

Keywords: reporting standards, research methods, meta-analysis

The American Psychological Association (APA) Working Group on Journal Article Reporting Standards (the JARS Group) arose out of a request for information from the APA Publications and Communications Board. The Publications and Communications Board had previously allowed any APA journal editor to require that a submission labeled by an author as describing a randomized clinical trial conform to the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) reporting guidelines (Altman et al., 2001; Moher, Schulz, & Altman, 2001). In this context, and recognizing that APA was about to initiate a revision of its Publication Manual (American Psychological Association, 2001), the Publications and Communications Board formed the JARS Group to provide itself with input on how the newly developed reporting standards related to the material currently in its Publication Manual and to propose some related recommendations for the new edition.

The JARS Group was formed of five current and previous editors of APA journals. It divided its work into six stages:

establishing the need for more well-defined reporting standards,

gathering the standards developed by other related groups and professional organizations relating to both new data collections and meta-analyses,

drafting a set of standards for APA journals,

sharing the drafted standards with cognizant others,

refining the standards yet again, and

addressing additional and unresolved issues.

This article is the report of the JARS Group’s findings and recommendations. It was approved by the Publications and Communications Board in the summer of 2007 and again in the spring of 2008 and was transmitted to the task force charged with revising the Publication Manual for consideration as it did its work. The content of the report roughly follows the stages of the group’s work. Those wishing to move directly to the reporting standards can go to the sections titled Information for Inclusion in Manuscripts That Report New Data Collections and Information for Inclusion in Manuscripts That Report Meta-Analyses.

Why Are More Well-Defined Reporting Standards Needed?

The JARS Group members began their work by sharing with each other documents they knew of that related to reporting standards. The group found that the past decade had witnessed two developments in the social, behavioral, and medical sciences that encouraged researchers to provide more details when they reported their investigations. The first impetus for more detail came from the worlds of policy and practice. In these realms, the call for use of “evidence-based” decision making had placed a new emphasis on the importance of understanding how research was conducted and what it found. For example, in 2006, the APA Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice defined the term evidence-based practice to mean “the integration of the best available research with clinical expertise” (p. 273; italics added). The report went on to say that “evidence-based practice requires that psychologists recognize the strengths and limitations of evidence obtained from different types of research” (p. 275).

In medicine, the movement toward evidence-based practice is now so pervasive (see Sackett, Rosenberg, Muir Grey, Hayes & Richardson, 1996) that there exists an international consortium of researchers (the Cochrane Collaboration; http://www.cochrane.org/index.htm) producing thousands of papers examining the cumulative evidence on everything from public health initiatives to surgical procedures. Another example of accountability in medicine, and the importance of relating medical practice to solid medical science, comes from the member journals of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (2007), who adopted a policy requiring registration of all clinical trials in a public trials registry as a condition of consideration for publication.

In education, the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (2002) required that the policies and practices adopted by schools and school districts be “scientifically based,” a term that appears over 100 times in the legislation. In public policy, a consortium similar to that in medicine now exists (the Campbell Collaboration; http://www.campbellcollaboration.org), as do organizations meant to promote government policymaking based on rigorous evidence of program effectiveness (e.g., the Coalition for Evidence-Based Policy; http://www.excelgov.org/index.php?keyword=a432fbc34d71c7). Each of these efforts operates with a definition of what constitutes sound scientific evidence. The developers of previous reporting standards argued that new transparency in reporting is needed so that judgments can be made by users of evidence about the appropriate inferences and applications derivable from research findings.

The second impetus for more detail in research reporting has come from within the social and behavioral science disciplines. As evidence about specific hypotheses and theories accumulates, greater reliance is being placed on syntheses of research, especially meta-analyses (Cooper, 2009; Cooper, Hedges, & Valentine, 2009), to tell us what we know about the workings of the mind and the laws of behavior. Different findings relating to a specific question examined with various research designs are now mined by second users of the data for clues to the mediation of basic psychological, behavioral, and social processes. These clues emerge by clustering studies based on distinctions in their methods and then comparing their results. This synthesis-based evidence is then used to guide the next generation of problems and hypotheses studied in new data collections. Without complete reporting of methods and results, the utility of studies for purposes of research synthesis and meta-analysis is diminished.

The JARS Group viewed both of these stimulants to action as positive developments for the psychological sciences. The first provides an unprecedented opportunity for psychological research to play an important role in public and health policy. The second promises a sounder evidence base for explanations of psychological phenomena and a next generation of research that is more focused on resolving critical issues.

The Current State of the Art

Next, the JARS Group collected efforts of other social and health organizations that had recently developed reporting standards. Three recent efforts quickly came to the group’s attention. Two efforts had been undertaken in the medical and health sciences to improve the quality of reporting of primary studies and to make reports more useful for the next users of the data. The first effort is called CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials; Altman et al., 2001; Moher et al., 2001). The CONSORT standards were developed by an ad hoc group primarily composed of biostatisticians and medical researchers. CONSORT relates to the reporting of studies that carried out random assignment of participants to conditions. It comprises a checklist of study characteristics that should be included in research reports and a flow diagram that provides readers with a description of the number of participants as they progress through the study—and by implication the number who drop out—from the time they are deemed eligible for inclusion until the end of the investigation. These guidelines are now required by the top-tier medical journals and many other biomedical journals. Some APA journals also use the CONSORT guidelines.

The second effort is called TREND (Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonexperimental Designs; Des Jarlais, Lyles, Crepaz, & the TREND Group, 2004). TREND was developed under the initiative of the Centers for Disease Control, which brought together a group of editors of journals related to public health, including several journals in psychology. TREND contains a 22-item checklist, similar to CONSORT, but with a specific focus on reporting standards for studies that use quasi-experimental designs, that is, group comparisons in which the groups were established using procedures other than random assignment to place participants in conditions.

In the social sciences, the American Educational Research Association (2006) recently published “Standards for Reporting on Empirical Social Science Research in AERA Publications.” These standards encompass a broad range of research designs, including both quantitative and qualitative approaches, and are divided into eight general areas, including problem formulation; design and logic of the study; sources of evidence; measurement and classification; analysis and interpretation; generalization; ethics in reporting; and title, abstract, and headings. They contain about two dozen general prescriptions for the reporting of studies as well as separate prescriptions for quantitative and qualitative studies.

Relation to the APA Publication Manual

The JARS Group also examined previous editions of the APA Publication Manual and discovered that for the last half century it has played an important role in the establishment of reporting standards. The first edition of the APA Publication Manual, published in 1952 as a supplement to Psychological Bulletin (American Psychological Association, Council of Editors, 1952), was 61 pages long, printed on 6-in. by 9-in. paper, and cost $1. The principal divisions of manuscripts were titled Problem, Method, Results, Discussion, and Summary (now the Abstract). According to the first Publication Manual, the section titled Problem was to include the questions asked and the reasons for asking them. When experiments were theory-driven, the theoretical propositions that generated the hypotheses were to be given, along with the logic of the derivation and a summary of the relevant arguments. The method was to be “described in enough detail to permit the reader to repeat the experiment unless portions of it have been described in other reports which can be cited” (p. 9). This section was to describe the design and the logic of relating the empirical data to theoretical propositions, the subjects, sampling and control devices, techniques of measurement, and any apparatus used. Interestingly, the 1952 Manual also stated, “Sometimes space limitations dictate that the method be described synoptically in a journal, and a more detailed description be given in auxiliary publication” (p. 25). The Results section was to include enough data to justify the conclusions, with special attention given to tests of statistical significance and the logic of inference and generalization. The Discussion section was to point out limitations of the conclusions, relate them to other findings and widely accepted points of view, and give implications for theory or practice. Negative or unexpected results were not to be accompanied by extended discussions; the editors wrote, “Long ‘alibis,’ unsupported by evidence or sound theory, add nothing to the usefulness of the report” (p. 9). Also, authors were encouraged to use good grammar and to avoid jargon, as “some writing in psychology gives the impression that long words and obscure expressions are regarded as evidence of scientific status” (pp. 25–26).

Through the following editions, the recommendations became more detailed and specific. Of special note was the Report of the Task Force on Statistical Inference (Wilkinson & the Task Force on Statistical Inference, 1999), which presented guidelines for statistical reporting in APA journals that informed the content of the 4th edition of the Publication Manual. Although the 5th edition of the Manual does not contain a clearly delineated set of reporting standards, this does not mean the Manual is devoid of standards. Instead, recommendations, standards, and requirements for reporting are embedded in various sections of the text. Most notably, statements regarding the method and results that should be included in a research report (as well as how this information should be reported) appear in the Manual’s description of the parts of a manuscript (pp. 10–29). For example, when discussing who participated in a study, the Manual states, “When humans participated as the subjects of the study, report the procedures for selecting and assigning them and the agreements and payments made” (p. 18). With regard to the Results section, the Manual states, “Mention all relevant results, including those that run counter to the hypothesis” (p. 20), and it provides descriptions of “sufficient statistics” (p. 23) that need to be reported.

Thus, although reporting standards and requirements are not highlighted in the most recent edition of the Manual, they appear nonetheless. In that context, then, the proposals offered by the JARS Group can be viewed not as breaking new ground for psychological research but rather as a systematization, clarification, and—to a lesser extent than might at first appear—an expansion of standards that already exist. The intended contribution of the current effort, then, becomes as much one of increased emphasis as increased content.

Drafting, Vetting, and Refinement of the JARS

Next, the JARS Group canvassed the APA Council of Editors to ascertain the degree to which the CONSORT and TREND standards were already in use by APA journals and to make us aware of other reporting standards. Also, the JARS Group requested from the APA Publications Office data it had on the use of auxiliary websites by authors of APA journal articles. With this information in hand, the JARS Group compared the CONSORT, TREND, and AERA standards to one another and developed a combined list of nonredundant elements contained in any or all of the three sets of standards. The JARS Group then examined the combined list, rewrote some items for clarity and ease of comprehension by an audience of psychologists and other social and behavioral scientists, and added a few suggestions of its own.

This combined list was then shared with the APA Council of Editors, the APA Publication Manual Revision Task Force, and the Publications and Communications Board. These groups were requested to react to it. After receiving these reactions and anonymous reactions from reviewers chosen by the American Psychologist, the JARS Group revised its report and arrived at the list of recommendations contained in Tables 1, 2, and 3 and Figure 1. The report was then approved again by the Publications and Communications Board.

Table 1.

Journal Article Reporting Standards (JARS): Information Recommended for Inclusion in Manuscripts That Report New Data Collections Regardless of Research Design

| Paper section and topic | Description |

|---|---|

| Title and title page | Identify variables and theoretical issues under investigation and the relationship between them Author note contains acknowledgment of special circumstances: Use of data also appearing in previous publications, dissertations, or conference papers Sources of funding or other support Relationships that may be perceived as conflicts of interest |

| Abstract | Problem under investigation Participants or subjects; specifying pertinent characteristics; in animal research, include genus and species Study method, including: Sample size Any apparatus used Outcome measures Data-gathering procedures Research design (e.g., experiment, observational study) Findings, including effect sizes and confidence intervals and/or statistical significance levels Conclusions and the implications or applications |

| Introduction | The importance of the problem: Theoretical or practical implications Review of relevant scholarship: Relation to previous work If other aspects of this study have been reported on previously, how the current report differs from these earlier reports Specific hypotheses and objectives: Theories or other means used to derive hypotheses Primary and secondary hypotheses, other planned analyses How hypotheses and research design relate to one another |

| Method | |

| Participant characteristics | Eligibility and exclusion criteria, including any restrictions based on demographic characteristics Major demographic characteristics as well as important topic-specific characteristics (e.g., achievement level in studies of educational interventions), or in the case of animal research, genus and species |

| Sampling procedures | Procedures for selecting participants, including: The sampling method if a systematic sampling plan was implemented Percentage of sample approached that participated Self-selection (either by individuals or units, such as schools or clinics) Settings and locations where data were collected Agreements and payments made to participants Institutional review board agreements, ethical standards met, safety monitoring |

| Sample size, power, and precision | Intended sample size Actual sample size, if different from intended sample size How sample size was determined: Power analysis, or methods used to determine precision of parameter estimates Explanation of any interim analyses and stopping rules |

| Measures and covariates | Definitions of all primary and secondary measures and covariates: Include measures collected but not included in this report Methods used to collect data Methods used to enhance the quality of measurements: Training and reliability of data collectors Use of multiple observations Information on validated or ad hoc instruments created for individual studies, for example, psychometric and biometric properties |

| Research design | Whether conditions were manipulated or naturally observed Type of research design; provided in Table 3 are modules for: Randomized experiments (Module A1) Quasi-experiments (Module A2) Other designs would have different reporting needs associated with them |

| Results | |

| Participant flow | Total number of participants Flow of participants through each stage of the study |

| Recruitment Statistics and data analysis | Dates defining the periods of recruitment and repeated measurements or follow-up Information concerning problems with statistical assumptions and/or data distributions that could affect the validity of findings Missing data: Frequency or percentages of missing data Empirical evidence and/or theoretical arguments for the causes of data that are missing, for example, missing completely at random (MCAR), missing at random (MAR), or missing not at random (MNAR) Methods for addressing missing data, if used For each primary and secondary outcome and for each subgroup, a summary of: Cases deleted from each analysis Subgroup or cell sample sizes, cell means, standard deviations, or other estimates of precision, and other descriptive statistics Effect sizes and confidence intervals For inferential statistics (null hypothesis significance testing), information about: The a priori Type I error rate adopted Direction, magnitude, degrees of freedom, and exact p level, even if no significant effect is reported For multivariable analytic systems (e.g., multivariate analyses of variance, regression analyses, structural equation modeling analyses, and hierarchical linear modeling) also include the associated variance–covariance (or correlation) matrix or matrices Estimation problems (e.g., failure to converge, bad solution spaces), anomalous data points Statistical software program, if specialized procedures were used Report any other analyses performed, including adjusted analyses, indicating those that were prespecified and those that were exploratory (though not necessarily in level of detail of primary analyses) |

| Ancillary analyses | Discussion of implications of ancillary analyses for statistical error rates |

| Discussion | Statement of support or nonsupport for all original hypotheses: Distinguished by primary and secondary hypotheses Post hoc explanations Similarities and differences between results and work of others Interpretation of the results, taking into account: Sources of potential bias and other threats to internal validity Imprecision of measures The overall number of tests or overlap among tests, and Other limitations or weaknesses of the study Generalizability (external validity) of the findings, taking into account: The target population Other contextual issues Discussion of implications for future research, program, or policy |

Table 2.

Module A: Reporting Standards for Studies With an Experimental Manipulation or Intervention (in Addition to Material Presented in Table 1)

| Paper section and topic | Description |

|---|---|

| Method | |

| Experimental manipulations or interventions | Details of the interventions or experimental manipulations intended for each study condition, including control groups, and how and when manipulations or interventions were actually administered, specifically including: Content of the interventions or specific experimental manipulations Summary or paraphrasing of instructions, unless they are unusual or compose the experimental manipulation, in which case they may be presented verbatim Method of intervention or manipulation delivery Description of apparatus and materials used and their function in the experiment Specialized equipment by model and supplier Deliverer: who delivered the manipulations or interventions Level of professional training Level of training in specific interventions or manipulations Number of deliverers and, in the case of interventions, the M, SD, and range of number of individuals/units treated by each Setting: where the manipulations or interventions occurred Exposure quantity and duration: how many sessions, episodes, or events were intended to be delivered, how long they were intended to last Time span: how long it took to deliver the intervention or manipulation to each unit Activities to increase compliance or adherence (e.g., incentives) Use of language other than English and the translation method |

| Units of delivery and analysis | Unit of delivery: How participants were grouped during delivery Description of the smallest unit that was analyzed (and in the case of experiments, that was randomly assigned to conditions) to assess manipulation or intervention effects (e.g., individuals, work groups, classes) If the unit of analysis differed from the unit of delivery, description of the analytical method used to account for this (e.g., adjusting the standard error estimates by the design effect or using multilevel analysis) |

| Results | |

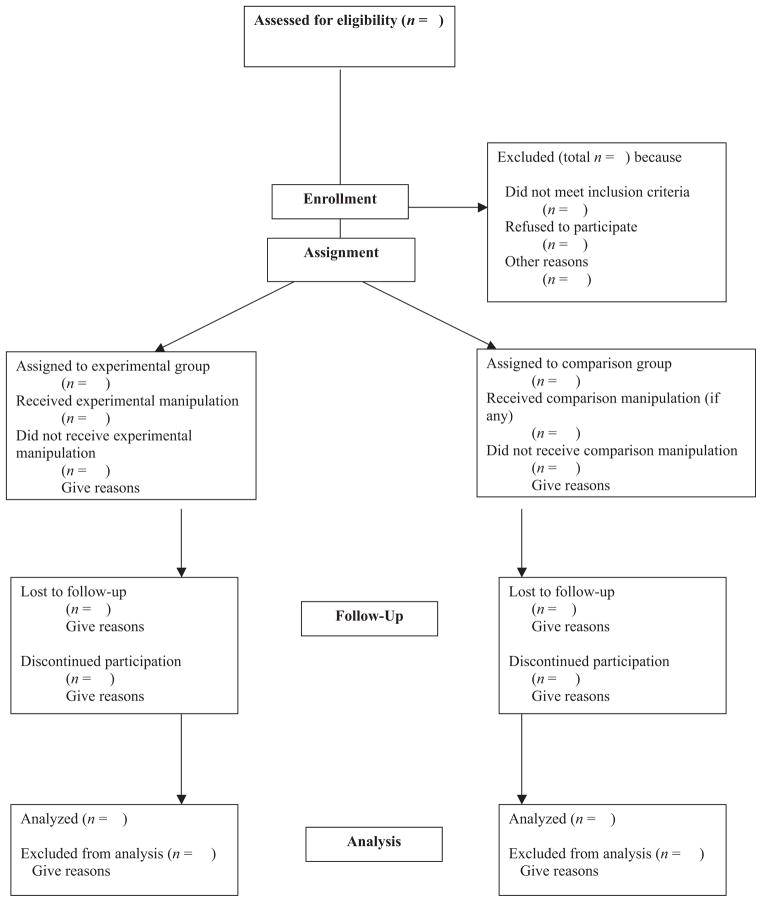

| Participant flow | Total number of groups (if intervention was administered at the group level) and the number of participants assigned to each group: Number of participants who did not complete the experiment or crossed over to other conditions, explain why Number of participants used in primary analyses Flow of participants through each stage of the study (see Figure 1) |

| Treatment fidelity | Evidence on whether the treatment was delivered as intended |

| Baseline data | Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of each group |

| Statistics and data analysis | Whether the analysis was by intent-to-treat, complier average causal effect, other or multiple ways |

| Adverse events and side effects | All important adverse events or side effects in each intervention group |

| Discussion | Discussion of results taking into account the mechanism by which the manipulation or intervention was intended to work (causal pathways) or alternative mechanisms If an intervention is involved, discussion of the success of and barriers to implementing the intervention, fidelity of implementation Generalizability (external validity) of the findings, taking into account: The characteristics of the intervention How, what outcomes were measured Length of follow-up Incentives Compliance rates The “clinical or practical significance” of outcomes and the basis for these interpretations |

Table 3.

Reporting Standards for Studies Using Random and Nonrandom Assignment of Participants to Experimental Groups

| Paper section and topic | Description |

|---|---|

| Module A1: Studies using random assignment | |

| Method | |

| Random assignment method | Procedure used to generate the random assignment sequence, including details of any restriction (e.g., blocking, stratification) |

| Random assignment concealment | Whether sequence was concealed until interventions were assigned |

| Random assignment implementation | Who generated the assignment sequence Who enrolled participants Who assigned participants to groups |

| Masking | Whether participants, those administering the interventions, and those assessing the outcomes were unaware of condition assignments If masking took place, statement regarding how it was accomplished and how the success of masking was evaluated |

| Statistical methods | Statistical methods used to compare groups on primary outcome(s) Statistical methods used for additional analyses, such as subgroup analyses and adjusted analysis Statistical methods used for mediation analyses |

| Module A2: Studies using nonrandom assignment | |

| Method | |

| Assignment method | Unit of assignment (the unit being assigned to study conditions, e.g., individual, group, community) Method used to assign units to study conditions, including details of any restriction (e.g., blocking, stratification, minimization) Procedures employed to help minimize potential bias due to nonrandomization (e.g., matching, propensity score matching) |

| Masking | Whether participants, those administering the interventions, and those assessing the outcomes were unaware of condition assignments If masking took place, statement regarding how it was accomplished and how the success of masking was evaluated |

| Statistical methods | Statistical methods used to compare study groups on primary outcome(s), including complex methods for correlated data Statistical methods used for additional analyses, such as subgroup analyses and adjusted analysis (e.g., methods for modeling pretest differences and adjusting for them) Statistical methods used for mediation analyses |

Figure 1. Flow of Participants Through Each Stage of an Experiment or Quasi-Experiment.

Note. This flowchart is an adaptation of the flowchart offered by the CONSORT Group (Altman et al., 2001; Moher, Schulz, & Altman, 2001). Journals publishing the original CONSORT flowchart have waived copyright protection.

Information for Inclusion in Manuscripts That Report New Data Collections

The entries in Tables 1 through 3 and Figure 1 divide the reporting standards into three parts. First, Table 1 presents information recommended for inclusion in all reports submitted for publication in APA journals. Note that these recommendations contain only a brief entry regarding the type of research design. Along with these general standards, then, the JARS Group also recommended that specific standards be developed for different types of research designs. Thus, Table 2 provides standards for research designs involving experimental manipulations or evaluations of interventions (Module A). Next, Table 3 provides standards for reporting either (a) a study involving random assignment of participants to experimental or intervention conditions (Module A1) or (b) quasi-experiments, in which different groups of participants receive different experimental manipulations or interventions but the groups are formed (and perhaps equated) using a procedure other than random assignment (Module A2). Using this modular approach, the JARS Group was able to incorporate the general recommendations from the current APA Publication Manual and both the CONSORT and TREND standards into a single set of standards. This approach also makes it possible for other research designs (e.g., observational studies, longitudinal designs) to be added to the standards by adding new modules.

The standards are categorized into the sections of a research report used by APA journals. To illustrate how the tables would be used, note that the Method section in Table 1 is divided into subsections regarding participant characteristics, sampling procedures, sample size, measures and covariates, and an overall categorization of the research design. Then, if the design being described involved an experimental manipulation or intervention, Table 2 presents additional information about the research design that should be reported, including a description of the manipulation or intervention itself and the units of delivery and analysis. Next, Table 3 presents two separate sets of reporting standards to be used depending on whether the participants in the study were assigned to conditions using a random or nonrandom procedure. Figure 1, an adaptation of the chart recommended in the CONSORT guidelines, presents a chart that should be used to present the flow of participants through the stages of either an experiment or a quasi-experiment. It details the amount and cause of participant attrition at each stage of the research.

In the future, new modules and flowcharts regarding other research designs could be added to the standards to be used in conjunction with Table 1. For example, tables could be constructed to replace Table 2 for the reporting of observational studies (e.g., studies with no manipulations as part of the data collection), longitudinal studies, structural equation models, regression discontinuity designs, single-case designs, or real-time data capture designs (Stone & Shiffman, 2002), to name just a few.

Additional standards could be adopted for any of the parts of a report. For example, the Evidence-Based Behavioral Medicine Committee (Davidson et al., 2003) examined each of the 22 items on the CONSORT checklist and described for each special considerations for reporting of research on behavioral medicine interventions. Also, this group proposed an additional 5 items, not included in the CONSORT list, that they felt should be included in reports on behavioral medicine interventions: (a) training of treatment providers, (b) supervision of treatment providers, (c) patient and provider treatment allegiance, (d) manner of testing and success of treatment delivery by the provider, and (e) treatment adherence. The JARS Group encourages other authoritative groups of interested researchers, practitioners, and journal editorial teams to use Table 1 as similar starting point in their efforts, adding and deleting items and modules to fit the information needs dictated by research designs that are prominent in specific subdisciplines and topic areas. These revisions could then be in corporated into future iterations of the JARS.

Information for Inclusion in Manuscripts That Report Meta-Analyses

The same pressures that have led to proposals for reporting - standards for manuscripts that report new data collections have led to similar efforts to establish standards for the reporting of other types of research. Particular attention has been focused on the reporting of meta-analyses.

With regard to reporting standards for meta-analysis, the JARS Group began by contacting the members of the Society for Research Synthesis Methodology and asking them to share with the group what they felt were the critical aspects of meta-analysis conceptualization, methodology, and results that need to be reported so that readers (and manuscript reviewers) can make informed, critical judgments about the appropriateness of the methods used for the inferences drawn. This query led to the identification of four other efforts to establish reporting standards for meta-analysis. These included the QUOROM Statement (Quality of Reporting of Meta-analysis; Moher et al., 1999) and its revision, PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & the PRISMA Group, 2008), MOOSE (Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology; Stroup et al., 2000), and the Potsdam Consultation on Meta-Analysis (Cook, Sackett, & Spitzer, 1995).

Next the JARS Group compared the content of each of the four sets of standards with the others and developed a combined list of nonredundant elements contained in any or all of them. The JARS Group then examined the combined list, rewrote some items for clarity and ease of comprehension by an audience of psychologists, and added a few suggestions of its own. Then the resulting recommendations were shared with a subgroup of members of the Society for Research Synthesis Methodology who had experience writing and reviewing research syntheses in the discipline of psychology. After these suggestions were incorporated into the list, it was shared with members of the Publications and Communications Board, who were requested to react to it. After receiving these reactions, the JARS Group arrived at the list of recommendations contained in Table 4, titled Meta-Analysis Reporting Standards (MARS). These were then approved by the Publications and Communications Board.

Table 4.

Meta-Analysis Reporting Standards (MARS): Information Recommended for Inclusion in Manuscripts Reporting Meta-Analyses

| Paper section and topic | Description |

|---|---|

| Title | Make it clear that the report describes a research synthesis and include “meta-analysis,” if applicable Footnote funding source(s) |

| Abstract | The problem or relation(s) under investigation Study eligibility criteria Type(s) of participants included in primary studies Meta-analysis methods (indicating whether a fixed or random model was used) Main results (including the more important effect sizes and any important moderators of these effect sizes) Conclusions (including limitations) Implications for theory, policy, and/or practice |

| Introduction | Clear statement of the question or relation(s) under investigation: Historical background Theoretical, policy, and/or practical issues related to the question or relation(s) of interest Rationale for the selection and coding of potential moderators and mediators of results Types of study designs used in the primary research, their strengths and weaknesses Types of predictor and outcome measures used, their psychometric characteristics Populations to which the question or relation is relevant Hypotheses, if any |

| Method | |

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria | Operational characteristics of independent (predictor) and dependent (outcome) variable(s) Eligible participant populations Eligible research design features (e.g., random assignment only, minimal sample size) Time period in which studies needed to be conducted Geographical and/or cultural restrictions |

| Moderator and mediator analyses | Definition of all coding categories used to test moderators or mediators of the relation(s) of interest |

| Search strategies | Reference and citation databases searched Registries (including prospective registries) searched: Keywords used to enter databases and registries Search software used and version Time period in which studies needed to be conducted, if applicable Other efforts to retrieve all available studies: Listservs queried Contacts made with authors (and how authors were chosen) Reference lists of reports examined Method of addressing reports in languages other than English Process for determining study eligibility: Aspects of reports were examined (i.e, title, abstract, and/or full text) Number and qualifications of relevance judges Indication of agreement How disagreements were resolved Treatment of unpublished studies |

| Coding procedures | Number and qualifications of coders (e.g., level of expertise in the area, training) Intercoder reliability or agreement Whether each report was coded by more than one coder and if so, how disagreements were resolved Assessment of study quality: If a quality scale was employed, a description of criteria and the procedures for application If study design features were coded, what these were How missing data were handled |

| Statistical methods | Effect size metric(s): Effect sizes calculating formulas (e.g., Ms and SDs, use of univariate F to r transform) Corrections made to effect sizes (e.g., small sample bias, correction for unequal ns) Effect size averaging and/or weighting method(s) How effect size confidence intervals (or standard errors) were calculated How effect size credibility intervals were calculated, if used How studies with more than one effect size were handled Whether fixed and/or random effects models were used and the model choice justification How heterogeneity in effect sizes was assessed or estimated Ms and SDs for measurement artifacts, if construct-level relationships were the focus Tests and any adjustments for data censoring (e.g., publication bias, selective reporting) Tests for statistical outliers Statistical power of the meta-analysis Statistical programs or software packages used to conduct statistical analyses |

| Results | Number of citations examined for relevance List of citations included in the synthesis Number of citations relevant on many but not all inclusion criteria excluded from the meta-analysis Number of exclusions for each exclusion criterion (e.g., effect size could not be calculated), with examples Table giving descriptive information for each included study, including effect size and sample size Assessment of study quality, if any Tables and/or graphic summaries: Overall characteristics of the database (e.g., number of studies with different research designs) Overall effect size estimates, including measures of uncertainty (e.g., confidence and/or credibility intervals) Results of moderator and mediator analyses (analyses of subsets of studies): Number of studies and total sample sizes for each moderator analysis Assessment of interrelations among variables used for moderator and mediator analyses Assessment of bias including possible data censoring |

| Discussion | Statement of major findings Consideration of alternative explanations for observed results: Impact of data censoring Generalizability of conclusions: Relevant populations Treatment variations Dependent (outcome) variables Research designs General limitations (including assessment of the quality of studies included) Implications and interpretation for theory, policy, or practice Guidelines for future research |

Other Issues Related to Reporting Standards

A Definition of “Reporting Standards”

The JARS Group recognized that there are three related terms that need definition when one speaks about journal article reporting standards: recommendations, standards, and requirements. According to Merriam-Webster’s Online Dictionary (n.d.), to recommend is “to present as worthy of acceptance or trial … to endorse as fit, worthy, or competent.” In contrast, a standard is more specific and should carry more influence: “something set up and established by authority as a rule for the measure of quantity, weight, extent, value, or quality.” And finally, a requirement goes further still by dictating a course of action—“something wanted or needed”—and to require is “to claim or ask for by right and authority … to call for as suitable or appropriate … to demand as necessary or essential.”

With these definitions in mind, the JARS Group felt it was providing recommendations regarding what information should be reported in the write-up of a psychological investigation and that these recommendations could also be viewed as standards or at least as a beginning effort at developing standards. The JARS Group felt this characterization was appropriate because the information it was proposing for inclusion in reports was based on an integration of efforts by authoritative groups of researchers and editors. However, the proposed standards are not offered as requirements. The methods used in the subdisciplines of psychology are so varied that the critical information needed to assess the quality of research and to integrate it successfully with other related studies varies considerably from method to method in the context of the topic under consideration. By not calling them “requirements,” the JARS Group felt the standards would be given the weight of authority while retaining for authors and editors the flexibility to use the standards in the most efficacious fashion (see below).

The Tension Between Complete Reporting and Space Limitations

There is an innate tension between transparency in reporting and the space limitations imposed by the print medium. As descriptions of research expand, so does the space needed to report them. However, recent improvements in the capacity of and access to electronic storage of information suggest that this trade-off could someday disappear. For example, the journals of the APA, among others, now make available to authors auxiliary websites that can be used to store supplemental materials associated with the articles that appear in print. Similarly, it is possible for electronic journals to contain short reports of research with hot links to websites containing supplementary files.

The JARS Group recommends an increased use and standardization of supplemental websites by APA journals and authors. Some of the information contained in the reporting standards might not appear in the published article itself but rather in a supplemental website. For example, if the instructions in an investigation are lengthy but critical to understanding what was done, they may be presented verbatim in a supplemental website. Supplemental materials might include the flowchart of participants through the study. It might include oversized tables of results (especially those associated with meta-analyses involving many studies), audio or video clips, computer programs, and even primary or supplementary data sets. Of course, all such supplemental materials should be subject to peer review and should be submitted with the initial manuscript. Editors and reviewers can assist authors in determining what material is supplemental and what needs to be presented in the article proper.

Other Benefits of Reporting Standards

The general principle that guided the establishment of the JARS for psychological research was the promotion of sufficient and transparent descriptions of how a study was conducted and what the researcher(s) found. Complete reporting allows clearer determination of the strengths and weaknesses of a study. This permits the users of the evidence to judge more accurately the appropriate inferences and applications derivable from research findings.

Related to quality assessments, it could be argued as well that the existence of reporting standards will have a salutary effect on the way research is conducted. For example, by setting a standard that rates of loss of participants should be reported (see Figure 1), researchers may begin considering more concretely what acceptable levels of attrition are and may come to employ more effective procedures meant to maximize the number of participants who complete a study. Or standards that specify reporting a confidence interval along with an effect size might motivate researchers to plan their studies so as to ensure that the confidence intervals surrounding point estimates will be appropriately narrow.

Also, as noted above, reporting standards can improve secondary use of data by making studies more useful for meta-analysis. More broadly, if standards are similar across disciplines, a consistency in reporting could promote interdisciplinary dialogue by making it clearer to researchers how their efforts relate to one another.

And finally, reporting standards can make it easier for other researchers to design and conduct replications and related studies by providing more complete descriptions of what has been done before. Without complete reporting of the critical aspects of design and results, the value of the next generation of research may be compromised.

Possible Disadvantages of Standards

It is important to point out that reporting standards also can lead to excessive standardization with negative implications. For example, standardized reporting could fill articles with details of methods and results that are inconsequential to interpretation. The critical facts about a study can get lost in an excess of minutiae. Further, a forced consistency can lead to ignoring important uniqueness. Reporting standards that appear comprehensive might lead researchers to believe that “If it’s not asked for or does not conform to criteria specified in the standards, it’s not necessary to report.” In rare instances, then, the setting of reporting standards might lead to the omission of information critical to understanding what was done in a study and what was found.

Also, as noted above, different methods are required for studying different psychological phenomena. What needs to be reported in order to evaluate the correspondence between methods and inferences is highly dependent on the research question and empirical approach. Inferences about the effectiveness of psychotherapy, for example, require attention to aspects of research design and analysis that are different from those important for inferences in the neuroscience of text processing. This context dependency pertains not only to topic-specific considerations but also to research designs. Thus, an experimental study of the determinants of well-being analyzed via analysis of variance engenders different reporting needs than a study on the same topic that employs a passive longitudinal design and structural equation modeling. Indeed, the variations in substantive topics and research designs are factorial in this regard. So experiments in psychotherapy and neuroscience could share some reporting standards, even though studies employing structural equation models investigating well-being would have little in common with experiments in neuroscience.

Obstacles to Developing Standards

One obstacle to developing reporting standards encountered by the JARS Group was that differing taxonomies of research approaches exist and different terms are used within different subdisciplines to describe the same operational research variations. As simple examples, researchers in health psychology typically refer to studies that use experimental manipulations of treatments conducted in naturalistic settings as randomized clinical trials, whereas similar designs are referred to as randomized field trials in educational psychology. Some research areas refer to the use of random assignment of participants, whereas others use the term random allocation. Another example involves the terms multilevel model, hierarchical linear model, and mixed effects model, all of which are used to identify a similar approach to data analysis. There have been, from time to time, calls for standardized terminology to describe commonly but inconsistently used scientific terms, such as Kraemer et al.’s (1997) distinctions among words commonly used to denote risk. To address this problem, the JARS Group attempted to use the simplest descriptions possible and to avoid jargon and recommended that the new Publication Manual include some explanatory text.

A second obstacle was that certain research topics and methods will reveal different levels of consensus regarding what is and is not important to report. Generally, the newer and more complex the technique, the less agreement there will be about reporting standards. For example, although there are many benefits to reporting effect sizes, there are certain situations (e.g., multilevel designs) where no clear consensus exists on how best to conceptualize and/or calculate effect size measures. In a related vein, reporting a confidence interval with an effect size is sound advice, but calculating confidence intervals for effect sizes is often difficult given the current state of software. For this reason, the JARS Group avoided developing reporting standards for research designs about which a professional consensus had not yet emerged. As consensus emerges, the JARS can be expanded by adding modules.

Finally, the rapid pace of developments in methodology dictates that any standards would have to be updated frequently in order to retain currency. For example, the state of the art for reporting various analytic techniques is in a constant state of flux. Although some general principles (e.g., reporting the estimation procedure used in a structural equation model) can incorporate new developments easily, other developments can involve fundamentally new types of data for which standards must, by necessity, evolve rapidly. Nascent and emerging areas, such as functional neuroimaging and molecular genetics, may require developers of standards to be on constant vigil to ensure that new research areas are appropriately covered.

Questions for the Future

It has been mentioned several times that the setting of standards for reporting of research in psychology involves both general considerations and considerations specific to separate subdisciplines. And, as the brief history of standards in the APA Publication Manual suggests, standards evolve over time. The JARS Group expects refinements to the contents of its tables. Further, in the spirit of evidence-based decision making that is one impetus for the renewed emphasis on reporting standards, we encourage the empirical examination of the effects that standards have on reporting practices. Not unlike the issues many psychologists study, the proposal and adoption of reporting standards is itself an intervention. It can be studied for its effects on the contents of research reports and, most important, its impact on the uses of psychological research by decision makers in various spheres of public and health policy and by scholars seeking to understand the human mind and behavior.

Footnotes

The Working Group on Journal Article Reporting Standards was composed of Mark Appelbaum, Harris Cooper (Chair), Scott Maxwell, Arthur Stone, and Kenneth J. Sher. The working group wishes to thank members of the American Psychological Association’s (APA’s) Publications and Communications Board, the APA Council of Editors, and the Society for Research Synthesis Methodology for comments on this report and the standards contained herein.

References

- Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D, Gotzsche PC, Lang T. The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: Explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2001;134(8):663–694. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00012. Retrieved April 20, 2007, from http://www.consort-statement.org/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- American Educational Research Association. Standards for reporting on empirical social science research in AERA publications. Educational Researcher. 2006;35(6):33–40. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Publication manual of the American Psychological Association. 5. Washington, DC: Author; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association, Council of Editors. Publication manual of the American Psychological Association. Psychological Bulletin. 1952;49(Suppl, Pt 2) [Google Scholar]

- APA Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice. Evidence-based practice in psychology. American Psychologist. 2006;61:271–283. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook DJ, Sackett DL, Spitzer WO. Methodologic guidelines for systematic reviews of randomized control trials in health care from the Potsdam Consultation on Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1995;48:167–171. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00172-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H. Research synthesis and meta-analysis: A step-by-step approach. 4. Thousand, Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JC, editors. The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis. 2. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson KW, Goldstein M, Kaplan RM, Kaufmann PG, Knatterud GL, Orleans TC, et al. Evidence-based behavioral medicine: What is it and how do we achieve it? Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26:161–171. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2603_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Lyles C, Crepaz N the TREND Group. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: The TREND statement. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:361–366. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.361. Retrieved April 20, 2007, from http://www.trend-statement.org/asp/documents/statements/AJPH_Mar2004_Trendstatement.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals: Writing and editing for biomedical publication. 2007 Retrieved April 9, 2008, from http://www.icmje.org/#clin_trials. [PubMed]

- Kraemer HC, Kazdin AE, Offord DR, Kessler RC, Jensen PS, Kupfer DJ. Coming to terms with the terms of risk. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:337–343. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160065009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary. nd Retrieved April 20, 2007, from http://www.m-w.com/dictionary/

- Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup D for the QUOROM group. Improving the quality of reporting of meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials: The QUOROM statement. Lancet. 1999;354:1896–1900. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)04149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: Revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2001;134(8):657–662. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00011. Retrieved April 20, 2007 from http://www.consort-statement.org. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG the PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis: The PRISMA statement. 2008. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, Pub. L. 107–110, 115 Stat. 1425 (2002, January 8).

- Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Muir Grey JA, Hayes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t. British Medical Journal. 1996;312:71–72. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, Shiffman S. Capturing momentary, self-report data: A proposal for reporting guidelines. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;24:236–243. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2403_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson L the Task Force on Statistical Inference. Statistical methods in psychology journals: Guidelines and explanations. American Psychologist. 1999;54:594–604. [Google Scholar]