Abstract

Multiple voltage-gated Ca2+ channel (CaV) subtypes have been reported to participate in control of the juxtamedullary glomerular arterioles of the kidney. Using the patch-clamp technique, we examined whole cell CaV currents of pericytes that contract descending vasa recta (DVR). The dihydropyridine CaV agonist FPL64176 (FPL) stimulated inward Ca2+ and Ba2+ currents that activated with threshold depolarizations to −40 mV and maximized between −20 and −10 mV. These currents were blocked by nifedipine (1 μM) and Ni2+ (100 and 1,000 μM), exhibited slow inactivation, and conducted Ba2+ > Ca2+ at a ratio of 2.3:1, consistent with “long-lasting” L-type CaV. In FPL, with 1 mM Ca2+ as charge carrier, Boltzmann fits yielded half-maximal activation potential (V1/2) and slope factors of −57.9 mV and 11.0 for inactivation and −33.3 mV and 4.4 for activation. In the absence of FPL stimulation, higher concentrations of divalent charge carriers were needed to measure basal currents. In 10 mM Ba2+, pericyte CaV currents activated with threshold depolarizations to −30 mV, were blocked by nifedipine, exhibited voltage-dependent block by diltiazem (10 μM), and conducted Ba2+ > Ca2+ at a ratio of ∼2:1. In Ca2+, Boltzmann fits to the data yielded V1/2 and slope factors of −39.6 mV and 10.0 for inactivation and 2.8 mV and 7.7 for activation. In Ba2+, V1/2 and slope factors were −29.2 mV and 9.2 for inactivation and −5.6 mV and 6.1 for activation. Neither calciseptine (10 nM), mibefradil (1 μM), nor ω-agatoxin IVA (20 and 100 nM) blocked basal Ba2+ currents. Calciseptine (10 nM) and mibefradil (1 μM) also failed to reverse ANG II-induced DVR vasoconstriction, although raising mibefradil concentration to 10 μM was partially effective. We conclude that DVR pericytes predominantly express voltage-gated divalent currents that are carried by L-type channels.

Keywords: barium, calcium, ion channel, mibefradil, patch clamp

within the outer stripe of the outer medulla, juxtamedullary efferent arterioles divide to form descending vasa recta (DVR), which supply blood flow to the renal medulla. An increasing body of evidence has shown that voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (CaV) play an important role in the regulation of basal tone and agonist-induced contraction of the juxtamedullary efferent circulation (13–15, 22, 31). Consistent with this evidence, Ca2+ channel blockers (CCB) have been observed to enhance medullary perfusion (1, 8, 16, 19, 20, 36, 55). The relative roles of DVR vs. upstream juxtamedullary vascular segments in the actions of CCB cannot be easily discerned, because the overlying renal cortex prevents access in vivo. Cell culture models that replicate the behavior of the pericytes and endothelia that comprise the DVR wall are lacking. To permit ex vivo investigations, DVR have been explanted for microperfusion, microfluorescence, and patch-clamp studies (42, 44, 45), and behavior consistent with CaV-mediated regulation has been observed. ANG II, endothelin-1, and vasopressin depolarize DVR pericytes through a variable combination of Ca2+-dependent Cl− channel activation and K+ channel suppression (4, 43, 44, 59). In the absence of a specific ligand-receptor interaction, depolarization with high extracellular KCl elevates DVR pericyte cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca]CYT) and the L-type CCB diltiazem inhibits KCl-related contraction and [Ca]CYT elevation (48, 61). Recently, a search for voltage-gated cation entry routes into the pericyte led to surprising identification of a tetrodotoxin (TTX)-sensitive, rapidly inactivating Na+ conductance, traced to the voltage-gated Na+ channel NaV1.3, which, combined with Na+/Ca2+ exchange, might provide a surrogate Ca2+ entry mechanism (32, 58).

Motivated by the above-described evidence, functional expression of CaV in juxtamedullary efferent arterioles, and immunochemical evidence favoring their presence in DVR pericytes (21, 22, 31), we performed the present study to measure their signature currents. In series 1, we found that the dihydropyridine agonist FPL64176 (FPL) readily stimulates inward Ca2+ and Ba2+ currents, the characteristics of which are consistent with L-type channels. In the absence of FPL stimulation, otherwise small basal CaV currents were readily measured when intracellular Ca2+ was chelated and extracellular concentrations of Ca2+ or Ba2+ were raised to carry charge. Those basal CaV currents were blocked by nifedipine, Ni2+, and diltiazem, but not calciseptine, ω-agatoxin IVA, or low concentrations of mibefradil. Kinetics, activation and inactivation thresholds, and the ratio of Ba2+ to Ca2+ conductance are consistent with the predominance of L-type channels. We conclude that the channel architecture of explanted DVR pericytes most closely resembles that described for afferent smooth muscle, where Cl− channel activity and L-type CaV control membrane potential and Ca2+ entry, respectively (2, 5, 18, 29).

METHODS

Isolation of DVR.

Investigations involving animal use were performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee of the University of Maryland. Rats were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Under full anesthesia, the abdomen was opened and the kidneys were excised, so that euthanasia was induced by concomitant exsanguination. Tissue slices were stored at 4°C in a physiological saline solution (in mM: 155 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose, pH 7.4). As described previously (44), for patch-clamp studies, small wedges of renal medulla were dissected and transferred to Blendzyme 1 (Roche) at 0.27 mg/ml in high-glucose DMEM (Invitrogen, without serum), incubated at 37°C for 20 min, transferred to physiological saline solution, and stored at 4°C. Enzymatic tissue digestion was omitted when DVR were explanted for microperfusion (42).

Whole cell patch-clamp recording.

Gigaseals were directly formed on abluminal pericytes of isolated vessels as previously described (44, 48, 57) and studied by ruptured-patch whole cell recording (58). When pericytes showed evidence of open gap junction coupling (prolonged capacitance transients), the cells were abandoned (57); gap junction blockers were not employed in these studies. A two-stage vertical pipette puller (Narshige PP-830) was used to fabricate patch pipettes from borosilicate glass capillaries (1.5 mm OD, 1.0 mm ID; PG52151-4, World Precision Instruments); the patch pipettes were heat polished to a final resistance of 4–8 MΩ. Whole cell recording was performed with a CV201AU headstage and Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA; 10-kHz sampling) at room temperature. The following buffer, designed to minimize intracellular free Ca2+, was used in the electrode (in mM): 115 Cs methanesulfonate, 20 CsCl, 10 NaCl, 2 MgATP, 10 BAPTA or EGTA, and 10 HEPES, with pH adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH. The extracellular buffer, designed to suppress contaminating K+ and Cl− currents, consisted of (in mM) 115 NaCl, 30 tetraethylammonium Cl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose, with pH adjusted to 7.4 with niflumic acid (100 μM) and glibenclamide (10 μM). CaCl2 or BaCl2 was added to the extracellular buffer to carry divalent charge. In those cases where the L-type channel agonist FPL was not used to stimulate currents, TTX (100 nM) was included to inhibit the voltage-gated Na+ conductance of DVR pericytes (58). Results were corrected for junction potentials as previously described (37, 44). The cell capacitance observed in these studies [13.6 ± 0.5 pF (SE), n = 78] is similar to that previously observed (12.2 ± 0.5 pF, n = 94) in rat pericytes during study of voltage-gated Na+ currents (58).

Vasoactivity measurements.

Vasoactivity was studied by videomicroscopy using isolated, microperfused DVR (42). This preparation requires vessels to be explanted without enzymatic digestion, so that their walls withstand transmural pressure without rupturing. Isolated DVR were mounted on concentric pipettes, cannulated at one end, and held at the other end to permit flow into the collection pipette. The pipettes and vessels were positioned with micromanipulators (Instruments Technology and Machinery, Schertz, TX) near a thermocouple in the narrow entrance region of a custom-built chamber. Temperature was maintained with a feedback system (CN9000A, Omega Engineering, Bridgeport, NJ) at 37°C. The buffer used for dissection, perfusion, and bath was the same as that previously employed for similar experiments: 140 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na acetate, 5 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM NaHPO4/NaH2PO4, 1 mM CaCl2, 5 mM alanine, 0.1 mM l-arginine, 5 mM glucose, 5 mM HEPES, and 0.5 g/dl albumin, pH 7.4 at 37°C (41). DVR were observed through a ×40 objective to yield the final magnification of ×1,300, and images were captured with a Spot camera (Diagnostic Instruments). As in prior studies, constriction was quantified as percent reduction of internal diameter at the point of maximal constriction using National Institutes of Health ImageJ software for offline analysis (4, 41, 59). Diameter changes are expressed as percent constriction: [1 − (D/D0)] × 100, where D and D0 are the experimental and baseline diameters, respectively.

Reagents.

FPL and TTX were obtained from Tocris-Cookson (Ellisville, MO); calciseptine and ω-agatoxin IVA from Alomone (Jerusalem, Israel); Blendzyme 1 from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN); and ANG II, NiCl2, niflumic acid, mibefradil, nifedipine, diltiazem, and other chemicals from Sigma. Nifedipine, FPL, and niflumic acid were dissolved in DMSO. TTX was dissolved in aqueous 10 mM Na acetate buffer, pH 4.5. ANG II, mibefradil, and NiCl2 were dissolved in water. Reagents were stored frozen at −20°C, thawed, and diluted 1:1,000 on the day of the experiment. Excess reagents were discarded daily. Blendzyme was stored in 40-μl aliquots of 4.5 mg/ml in water and diluted into high-glucose DMEM on the day of the experiment.

Statistics.

Curve fits were performed with Clampfit 9.2 (Axon Instruments) using Levenberg-Marquardt algorithms. Values are means ± SE. The significance of differences was evaluated with SigmaStat 3.11 (Systat Software, Point Richmond, CA) using parametric or nonparametric tests as appropriate for the data. Comparisons between two groups were performed with Student's t-test (paired or unpaired, as appropriate) or the rank sum test (nonparametric). Comparisons between multiple groups employed one-way ANOVA, repeated-measures ANOVA, or repeated-measures ANOVA on ranks (nonparametric). P < 0.05 was used to reject the null hypothesis.

RESULTS

L-type CaV currents stimulated by FPL.

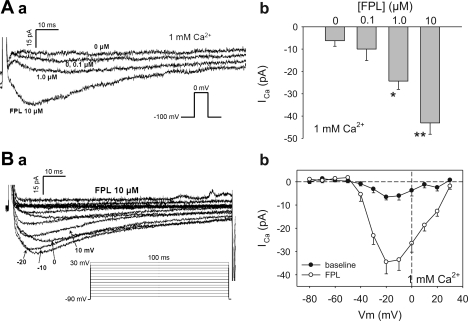

In the first series of experiments, we repeatedly depolarized pericytes from a holding level of −100 to 0 mV at 10-s intervals. Basal and FPL-stimulated currents were measured with EGTA as the Ca2+ chelator in the electrode and 1 mM Ca2+ as the extracellular charge carrier. As shown in Fig. 1, Aa and Ab, basal (no FPL) inward currents were nearly undetectable under these conditions. In contrast, when FPL was added to the extracellular buffer in sequentially increasing concentrations (0.1, 1.0, and 10 μM), a slowly inactivating inward current emerged when the cells were depolarized.

Fig. 1.

Stimulation of inward Ca2+ currents in descending vasa recta (DVR) pericytes by FPL64176 (FPL). Aa: inward currents elicited in 1 mM extracellular Ca2+ by sequential depolarizations from −100 to 0 mV in increasing concentrations of FPL. Ab: peak Ca2+ current (ICa) in DVR pericytes stimulated by 0–10 μM FPL. n = 7. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. 0 μM. Ba: voltage dependence of FPL-stimulated inward currents. Bb: peak ICa vs. depolarization potential (Vm). n = 9.

Voltage-dependent characteristics of the FPL (10 μM)-stimulated current were further studied using the protocol shown in the inset of Fig. 1Ba and are summarized in Fig. 1Bb. Basal inward current magnitude was <10 pA. In contrast, in FPL they activated at a threshold depolarization of about −40 mV, maximized between −10 and 0 mV, and reached ∼35 pA.

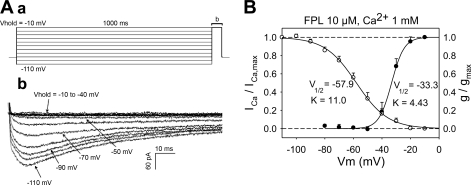

To study characteristics of inactivation of the FPL-induced current, the protocol illustrated in Fig. 2Aa (example in Fig. 2Ab) was executed. Pericytes were held at −110 to −10 mV for 1,000 ms and then depolarized to −10 mV. A summary of the voltage dependence of inactivation (ICa/ICa,max, where ICa is Ca2+ current) and activation (g/gmax, where g is conductance) is superimposed in Fig. 2B upon corresponding fits to the Boltzmann equation: y = 1/{1 + exp[s(Vm − V1/2)/K]}, where Vm is membrane potential, s = −1 or +1 for activation or inactivation, respectively, and V1/2 and K (slope factor) are constants. Activation was computed from the Ca2+ chord conductance (g), where g = ICa/(Vm − Carev) and Carev is the reversal potential. Values were normalized to maximum conductance (gmax). Inactivation of the FPL current commenced between −80 and −90 mV with V1/2 of −57.9 mV and slope factor of 11.0. Activation occurred between −30 and −40 mV with V1/2 of −33.3 mV and slope factor of 4.4, yielding an overlapping window current between −50 and −10 mV.

Fig. 2.

Voltage dependence of inactivation and activation of FPL-stimulated ICa. Aa: protocol used to study inactivation. Pericytes were held at various potentials (Vhold) for 1,000 ms and then depolarized to −10 mV. Ab: effects of various holding potentials on ICa. B: inactivation (ICa/ICa,max, n = 16) and activation [g/gmax (where g is conductance), n = 9] characteristics with 1 mM extracellular Ca2+ and 10 mM FPL as agonist. Half-maximal activation poential (V1/2) and slope factor (K) for Boltzmann fits were −57.9 mV and 11.0 for inactivation and −33.3 mV and 4.4 for activation, respectively.

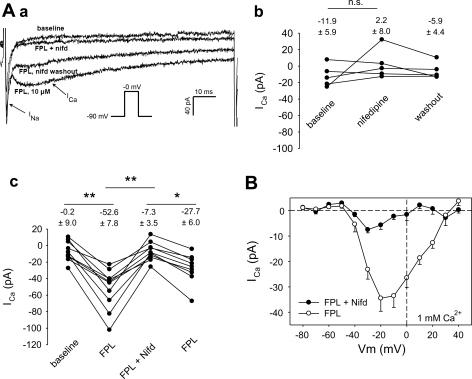

Blockade of FPL current with nifedipine and Ni2+.

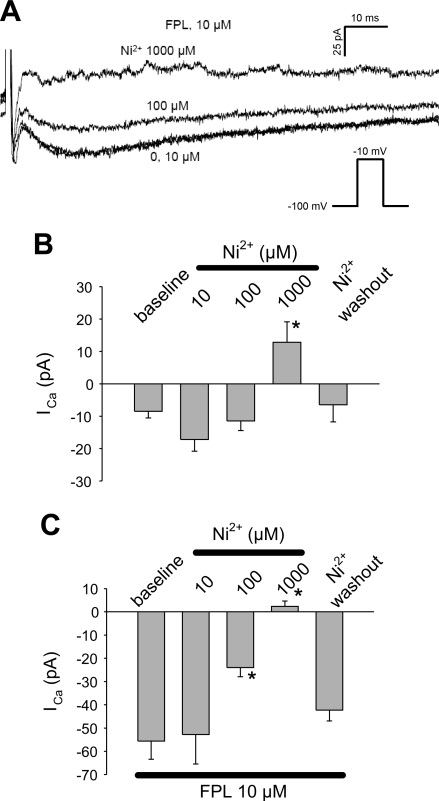

The FPL-stimulated inward current was sensitive to nifedipine (1 μM; Fig. 3) and Ni2+ (Fig. 4). Representative traces are provided in Fig. 3Aa, where, at baseline, only a rapidly inactivating “fast” inward Na+ current is present (58). Subsequently, FPL (10 μM) was introduced to elicit the slowly inactivating component of inward current. This was followed by addition and washout of nifedipine. In similar experiments without FPL, nifedipine failed to affect basal current (Fig. 3Ab). In contrast, it reversibly blocked the FPL-stimulated current (Fig. 3Ac) over the entire range of depolarization potentials (Vm; Fig. 3B). We also tested the effectiveness of Ni2+. At baseline, Ni2+ (1,000 μM) blocked a very small, depolarization-induced inward current (Fig. 4B). Between 100 and 1,000 μM, Ni2+ potently and reversibly inhibited the FPL-stimulated inward currents (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 3.

Nifedipine (Nifd) sensitivity of FPL-stimulated ICa. Aa: inward currents elicited in 1 mM extracellular Ca2+ by sequential depolarizations from −90 to 0 mV at baseline, in FPL (10 μM), in FPL + nifedipine (1 μM), and after nifedipine washout. Note prominent, rapidly inactivating Na+ current (INa) followed by slowly inactivating FPL-stimulated ICa. Nifedipine blocks ICa. Ab: ICa at baseline (without FPL), in nifedipine (1 μM), and during nifedipine washout. n = 5. Ac: in experiments similar to example in Aa, FPL increased ICa from −0.2 ± 9.0 to −52.6 ± 7.8 pA and nifedipine (1 μM) inhibited ICa to −7.3 ± 3.5 pA in a reversible manner. n = 10. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. B: voltage dependence of ICa in the presence and absence of nifedipine (reproduced from Fig. 1Bb).

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of FPL-stimulated ICa by Ni2+. A: inward currents elicited by sequential depolarizations from −100 to −10 mV in 1 mM extracellular Ca2+ + FPL (10 μM) in increasing concentrations of Ni2+ (0, 10, 100, 1,000 μM). B: effects of Ni2+ on unstimulated ICa. Ni2+ had a small, but significant, effect at 1,000 μM. n = 9. *P < 0.05 vs. 0 μM. C: effects of Ni2+ on FPL-stimulated ICa. Ni2+ achieved effective blockade at 100 and 1,000 μM. n = 13. *P < 0.05 vs. 0 μM.

Relative conductance of pericyte CaV currents to Ca2+ and Ba2+.

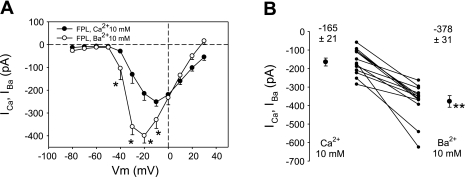

Conductance of L-type channels to Ba2+ generally exceeds that to Ca2+ by a factor of ∼2:1, whereas conductance of T-type channels to Ca2+ and Ba2+ is nearly equal (51, 56). To increase overall inward current to examine that characteristic, we increased the concentration of divalent charge carriers to 10 mM. As shown in Fig. 5A, large FPL-stimulated Ba2+ currents (peak −399 pA at −20 mV) exceeded Ca2+ currents (peak −251 pA at −10 mV). In a separate series of experiments, we repetitively depolarized individual cells from −110 to −10 mV and exchanged extracellular buffer to contain Ca2+ or Ba2+ (10 mM) in random order to yield a more rigorous paired comparison of their conductances. Mean currents for Ba2+ and Ca2+ in FPL were −378 ± 31 and −165 ± 21 pA (P < 0.01), respectively (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of relative conductance of FPL-stimulated pericytes to Ba2+ and Ca2+. A: voltage dependence of peak inward IBa and ICa in FPL (10 μM) with 10 mM extracellular Ba2+ and Ca2+. IBa exceeded ICa, and its activation threshold was shifted toward more negative potentials. n = 9 and 12 for IBa and ICa, respectively. *P < 0.05, IBa vs. ICa. B: paired comparison of IBa and ICa in FPL (10 μM) and extracellular Ca2+ or Ba2+ (10 mM) exchanged into the bath in random order. n = 10. **P < 0.01, IBa vs. ICa.

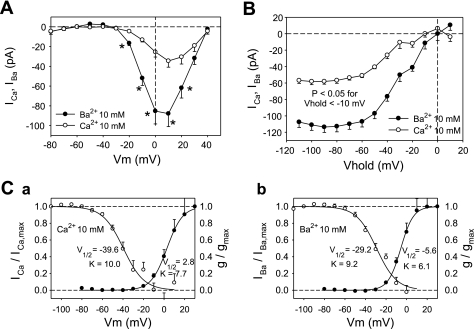

Since unstimulated CaV currents in 1 mM Ca2+ are too small to study (Fig. 1), we further optimized our conditions for measurement of basal currents by substituting BAPTA (10 mM) for EGTA to rapidly chelate Ca2+, thereby reducing any Ca2+-dependent inhibition (46). Moreover, we maintained extracellular concentrations of Ca2+ and Ba2+ at 10 mM (rather than 1 mM) to increase whole cell current and included TTX in the extracellular buffer to prevent the fast voltage-gated Na+ current from contaminating any rapidly inactivating T-type currents that might exist. Under those conditions, the basal inward currents were large enough to be measured without use of FPL as an agonist. Where seals were stable, activation and inactivation characteristics for Ba2+ and Ca2+ (Fig. 6) were examined in random order in the same cells. As shown in Fig. 6A, between test potentials of −10 and 20 mV, basal Ba2+ currents consistently exceeded those of Ca2+ by >2. Both activated at a threshold of about −30 mV, a somewhat higher potential than observed in FPL (−50 to −40 mV; Fig. 5A). These collective findings are consistent with predominance of L-type CaV basal conductance under these experimental conditions. Examination of the voltage dependence of inactivation of basal currents by use of a protocol similar to that used in Fig. 2Aa reinforced this relationship (Fig. 6B) and yielded the Boltzmann fits illustrated in Fig. 6, Ca and Cb. Window currents for both divalent ions are between −40 and +10 mV.

Fig. 6.

Voltage dependence of inactivation and activation in unstimulated DVR pericytes. A: voltage dependence of peak inward IBa and ICa with 10 mM extracellular Ba2+ and Ca2+ and BAPTA as electrode chelator. n = 9 and 19 for ICa and IBa, respectively. *P < 0.05, IBa vs. ICa. B: voltage dependence of inactivation for Ba2+ and Ca2+. n = 13 and 21 for ICa and IBa, respectively. P < 0.05 for all holding potentials less than −10 mV. Ca: Boltzmann fits to activation and inactivation for ICa yielded V1/2 and slope factor of −39.6 mV and 10 for inactivation and 2.8 mV and 7.7 for activation. Cb: Boltzmann fits to activation and inactivation for IBa yielded V1/2 and slope factor of −29.2 mV and 9.2 for inactivation and −5.6 mV and 6.1 for activation.

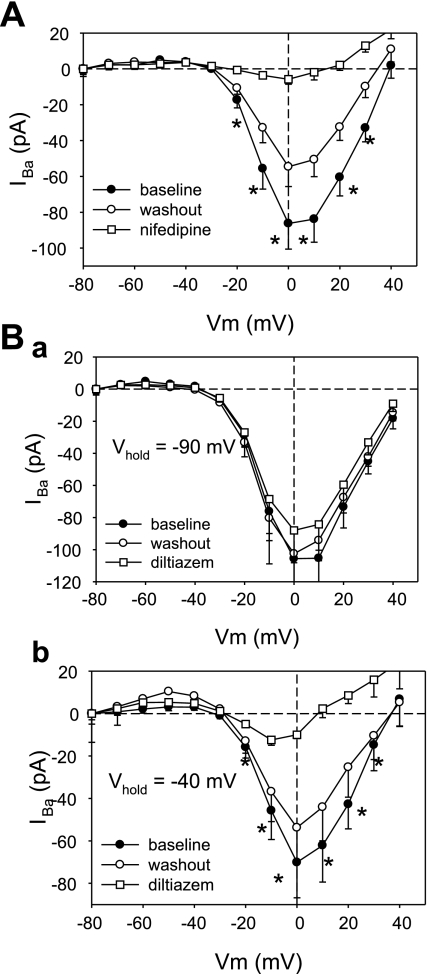

Sensitivity of pericyte Ba2+ currents to L-type channel blockade.

Using the same electrode buffer (BAPTA) and 10 mM Ba2+ as charge carrier, we explored the sensitivity of the basal pericyte inward currents to the classical L-type CCB nifedipine and diltiazem. As shown in Fig. 7A, nifedipine (1 μM) was highly effective in eliminating the Ba2+ currents. Diltiazem (10 μM) was also effective but exhibited voltage dependence; it was ineffective when cells were held at −90 mV (Fig. 7Ba) but highly effective when the holding potential was raised to −40 mV (Fig. 7Bb). This suggests improvement of access of diltiazem to its binding site with increases in membrane potential (53). The effectiveness of diltiazem in Fig. 7B is consistent with our previous observation that it blocks ANG II-induced vasoconstriction and KCl-induced pericyte [Ca]CYT elevation (61).

Fig. 7.

Inhibition of IBa by nifedipine and diltiazem. A: peak IBa in pericytes held at −90 mV and depolarized to test potentials (Vm) in 10 mM Ba2+. Inward currents are at baseline, in nifedipine (1 μM), and after washout. n = 8. *P < 0.05, baseline vs. nifedipine. B: peak IBa in pericytes held at −90 mV and depolarized to test potentials in 10 mM Ba2+ at baseline, in diltiazem (10 μM), and after washout (n = 5). C: peak IBa in pericytes held at −40 mV and depolarized to test potentials in 10 mM Ba2+ at baseline, in diltiazem, and after washout. n = 5. *P < 0.05, baseline vs. diltiazem.

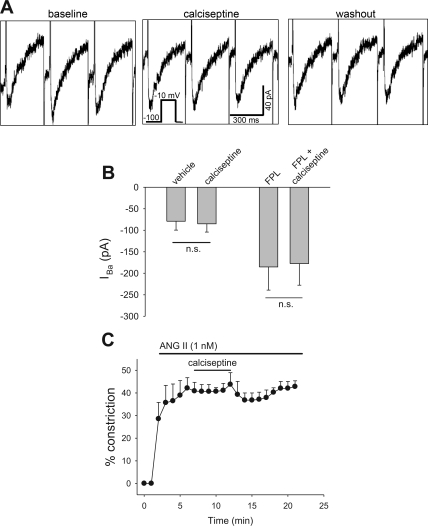

In view of the exquisite sensitivity of inhibition of rabbit afferent arteriolar KCl constriction to the black mamba toxin calciseptine (EC50 = 80 fM) (22), we also examined its ability to block Ba2+ currents in DVR pericytes. Surprisingly, at a 105-fold greater concentration (10 nM), it affected neither basal nor FPL-stimulated Ba2+ current (Fig. 8, A and B). Similarly, at the higher concentration of 30 nM, it failed to reverse ANG II (1 nM)-induced contraction of microperfused vessels (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8.

Lack of effect of calciseptine to reverse IBa or ANG II-induced vasoconstriction. A: pericytes were held at −100 mV and depolarized to −10 mV for 300 ms at 10-s intervals. Concatenated responses before (baseline), during (calciseptine), and after (washout) introduction of calciseptine (10 nM) are shown. B: basal (n = 6) and FPL (10 μM, n = 9)-stimulated peak IBa using protocol described in A. Calciseptine was without effect. NS, not significant. C: percent reduction of luminal diameter vs. time in microperfused DVR exposed to abluminal ANG II (1 nM) followed by addition and removal of calciseptine (30 nM). Calciseptine failed to reverse ANG II-induced vasoconstriction.

Sensitivity of pericyte Ba2+ currents to mibefradil.

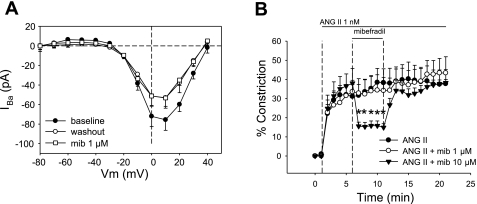

Given the growing literature concerning the role of T-type channels in the efferent circulation of the kidney (13, 22, 24, 26, 27, 31), we tested the ability of mibefradil to block DVR pericyte Ba2+ currents and vasoconstriction. Perfectly selective T-type CaV blockers do not exist; however, it is generally accepted that mibefradil inhibits T-type over L-type CaV when it is used at low concentrations, between 10 and 1,000 nM, which blocked efferent arteriolar constriction in other settings (13, 22, 25, 28, 31). In our hands, mibefradil (1 μM) affected neither Ba2+ currents nor ANG II-induced DVR vasoconstriction (Fig. 9, A and B). At higher concentration (10 μM), where mibefradil is likely to block L- and T-type CaV, it was an effective vasodilator (Fig. 9B).

Fig. 9.

Inhibition of IBa- and ANG II-induced vasoconstriction by mibefradil. A: peak IBa in pericytes held at −90 mV and depolarized to test potentials (Vm) in 10 mM Ba2+. Inward currents are shown at baseline, in mibefradil (1 μM, n = 7), and after washout. Mibefradil was without effect. B: microperfused DVR were exposed to abluminal ANG II followed by addition and removal of mibefradil at 0 μM (sham exchange, n = 6), 1 μM (n = 6), or 10 μM (n = 5). *P < 0.05 vs. sham exchange.

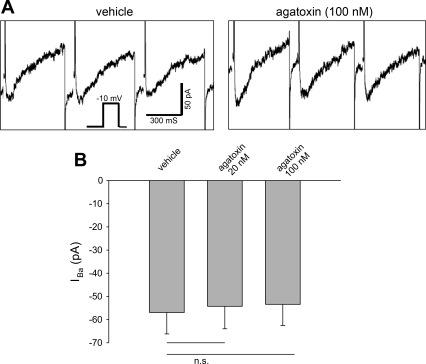

Sensitivity of pericyte Ba2+ currents to ω-agatoxin IVA.

Expression of CaV2.x in DVR pericytes has been observed by immunostaining, and the P/Q-type CaV inhibitor ω-agatoxin IVA (10 nM) is a potent blocker of afferent arteriolar constriction to KCl in the rabbit (2, 21). Since the Ba2+ > Ca2+ current and slow inactivation observed above might hypothetically contain a component of P/Q-type CaV conductance, we tested whether ω-agatoxin IVA provides any blockade. At ≤100 nM, ω-agatoxin IVA was ineffective (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Lack of effect of ω-agatoxin IVA to reverse IBa. A: pericytes were held at −100 mV and depolarized to −10 mV for 300 ms at 10-s intervals. Concatenated responses before (vehicle) and during and after introduction of ω-agatoxin IVA are shown. B: peak inward IBa using the protocol described in A with ω-agatoxin IVA at 20 nM (n = 9) or 100 nM (n = 10). ω-Agatoxin IVA was without effect.

DISCUSSION

Ca2+ influx through CaV facilitates elevation of [Ca]CYT during myocyte contraction. CaV are the product of 10 genes, the splice variants of which form the pore-forming α1a- to α1l-subunits of the channels. When combined with α2-, β-, and δ-subunits, they yield an array of properties characterized by variable kinetic behavior, voltage dependence, and sensitivity to toxins and pharmaceuticals (7, 11, 12, 27, 28, 31, 33, 38, 40, 52, 54, 56). Many CaV classification schemes exist. One durable approach has been to designate them L-type (CaV1.x), T-type (CaV2.x), P/Q-type (CaV2.1), N-type (CaV2.2), and R-type (CaV2.3). L-type CaV, so designated to describe their long opening and slow rate of inactivation, are common therapeutic targets in the treatment of hypertension, angina, and arrhythmias via dihydropyridine (e.g., nifedipine), phenylalkylamine (verapamil), and benzothiazepine (diltiazem) antagonists. T-type CaV, so designated to describe their transient opening and rapid inactivation, are also widely expressed in the cardiovascular system and have become a therapeutic target of less selective antagonists, such as mibefradil, pimozide, and efonidipine, that block L- and T-type channels (27, 28, 38, 40, 56). That therapeutic class may provide additive antihypertensive efficacy, because T-type channels are expressed in smooth muscle of small-resistance vessels (3).

The actions of CCB in the renal circulation have been intensively investigated, and the results point to heterogeneity of expression and action in the cortex and medulla. CCB classes vary in their ability to reverse contraction of and Ca2+ entry into vascular smooth muscle of the glomerular afferent and efferent arteriole. Evidence also has shown that their efficacy to block efferent contraction may vary with location of the vessel in the superficial vs. juxtamedullary cortex (21, 22, 27, 31).

Despite reducing the electrochemical driving force for Ca2+ entry, membrane depolarization increases [Ca]CYT of smooth muscle by gating CaV conductance. To achieve depolarization without use of vasoactive agonists, a popular maneuver has been to raise the Nernst potential of K+ from −90 to ∼0 mV by increasing its extracellular concentration. The ability of CCB to prevent the resultant contraction and rise in [Ca]CYT is interpreted as evidence for CaV expression. In the hydronephrotic kidney preparation, KCl caused nifedipine-sensitive constriction of afferent arterioles that exceeded constriction of the efferent arteriole (35). Similarly, diltiazem preferentially blocked KCl-induced vasoconstriction of isolated perfused afferent arterioles (9). Examination of [Ca]CYT responses yielded similar results: depolarization increased [Ca]CYT of afferent, but not efferent, arteriolar smooth muscle (6).

Blockade of responsiveness to agonists such as ANG II has provided an alternate means to assess participation of CaV in intrarenal microvessel contraction. When ANG II-stimulated Ca2+ entry into interlobular and afferent arteriolar smooth muscle was examined using fura 2, it was found that ANG II-induced increases in [Ca]CYT were dihydropyridine sensitive (30). Parallel studies found greater sensitivity of ANG II-stimulated [Ca]CYT increases to nifedipine in the afferent than efferent arteriole (34). L-type signature currents have been elegantly described by electrophysiology in myocytes of the afferent circulation (2, 18). These and other studies have consistently established that L-type voltage-gated channels provide a functionally important route for Ca2+ entry into preglomerular smooth muscle.

More recent investigations have expanded the known roles of CaV in the kidney by documenting multiple subtype expression and the variable efficacy of pharmacological blockade in the afferent and efferent circulation. In particular, Hansen and colleagues (21, 22) described L-, T-, and P/Q-type channel expression in afferent smooth muscle, as well as both T- and L-type channel expression in efferent arterioles. Efferent CaV expression was confined to the juxtamedullary cortex. Those immunochemical observations were reinforced by demonstration of sensitivity of KCl-induced efferent contraction to blockade with calciseptine (an L-type channel antagonist) and mibefradil (a T-type channel blocker) (2, 21, 22, 31). Feng and colleagues (13–15) used the juxtamedullary nephron preparation to examine the roles of arteriolar CaV. Pimozide and mibefradil (T-type channel blockers) reduced basal tone of afferent and efferent arterioles. In contrast, successful blockade with diltiazem (L-type channel blocker) occurred only in afferent arterioles, except when generation of nitric oxide was prevented by nitric oxide synthase inhibition. In their hands, T-type channel blockade with pimozide reversed afferent and efferent contraction by ANG II (13–15). Elegant studies in the renal cortex, performed in vivo using a pencil lens camera, also documented that efferent arterioles are dilated by nonselective CCB, such as efonidipine and mibefradil (28). Taken together, a role for CaV, particularly T-type channels, in myogenic tone and agonist-induced contraction of juxtamedullary efferent arterioles is well supported, and the ability of combined T- and L-type channel blockade to provide renoprotection through efferent dilation has thus become the subject of clinical investigation (23, 49, 50).

Investigation of the role of CaV in the microcirculation of the medulla has lagged behind that of the cortex. Interstitial infusion of diltiazem and intravenous infusion of verapamil selectively raised medullary blood flow (19, 20, 36). Using single-vessel videomicroscopy, Yagil and colleagues (55) observed an increase in papillary vasa recta blood flow by the dihydropyridine blocker CS-905. The effects of CCB on medullary blood flow have also been examined in pathological models. Papillary plasma flow increased when verapamil was infused into the renal artery of dogs subjected to caval constriction (8). Treatment of the spontaneously hypertensive rat with nisoldipine enhanced medullary blood flow and Na+ excretion (16). Taken together, the ability of L-type CCB to increase renal medullary blood flow has been a consistent finding. DVR are contractile branches of the juxtamedullary cortical circulation; therefore, it is uncertain whether the effects of L-type channel blockade are attributable to DVR vs. upstream segments.

Because of the relative inaccessibility of outer medullary DVR in vivo, their properties have been studied in isolated vessels (41, 42) or tissue preparations (10). The first evidence favoring participation of CaV in vasa recta was the consistency of ANG II-induced pericyte depolarization (44) and the ability of L-type blockade with diltiazem to vasodilate preconstricted vessels and block [Ca]CYT responses to ANG II, KCl, and PKC activation (60, 61). Robust ability of vasoactive agonists to depolarize pericytes through variable combination of Ca2+-dependent Cl− channel activation and K+ channel suppression has been a consistent finding (4, 43, 44). Motivated by the associated studies that clearly show CaV in juxtamedullary glomerular arterioles (27, 31), we performed the present study of signature CaV currents in DVR pericytes. Our initial studies revealed a surprising voltage-gated Na+ (NaV) conductance (32, 58). CaV currents, under the conditions used in those studies, were too small to measure. Here, we revised the experimental protocols to enhance the divalent currents, enabling examination of their properties.

In a first series of experiments, we used the dihydropyridine agonist FPL to increase conductance of putative L-type CaV. FPL elicited small, but detectable, inward current when 1 mM extracellular Ca2+ was the charge carrier (Fig. 1). The slow inactivation, threshold for activation near −40 mV (Fig. 2), and high conductance to Ba2+ over Ca2+ is consistent with L-type channel behavior (17, 51). Thus the FPL-based studies strongly support CaV1.x expression in DVR pericytes but do not rule out conductance by other isoforms.

In an effort to study CaV currents in the absence of agonist stimulation, we altered the experimental regimen to increase their magnitude. Since some classes of CaV are inhibited by Ca2+, we employed BAPTA in place of EGTA to achieve rapid chelation in the vicinity of the channel pore (46). Additionally, we increased the concentration of the extracellular charge carrier from 1 to 10 mM. Those changes yielded the desired effect, such that basal Ba2+ and Ca2+ currents became readily detectable (Fig. 6). L-type currents peak much later than voltage-gated Na+ currents (Fig. 3Aa), so that there is little risk of an error in quantifying CaV and NaV currents when both are present. In contrast, T-type currents typically activate and deactivate more quickly, leading us to use TTX to block NaV when quantifying basal CaV currents of the pericytes. In the absence of FPL, the voltage dependence of the currents shifted by about +10 mV, i.e., stronger depolarizations (to −30 vs. −40 mV in FPL; cf. Fig. 5A with Fig. 6A) were needed to activate the channels. That threshold is more consistent with an L- than a T-type current, which typically activates at lower potentials (56). For specific contrast, the results in Fig. 6, can be compared with the elegant studies of Gordienko et al. (Figs. 7 and 8 in Ref. 18) in which low- and high-threshold T- and L-type currents coexist in isolated preglomerular smooth muscle cells. As discussed above, much other evidence favoring roles for T-type channels has been obtained through pharmacological inhibition of vasoconstriction and immunostaining (13, 15, 22, 26, 28, 31, 47). Evidence that basal DVR pericyte currents are also largely conducted by CaV1.x, L-type channels is provided by their near elimination with nifedipine and diltiazem (Fig. 7) and twofold greater conductance to Ba2+ over Ca2+ (Fig. 6A).

The open probability of CaV is determined by a balance of states in which the channels can be opened in response to elevation of membrane potential and inactivation in which the channels cannot respond. Electrophysiologically, that is controlled by holding cells at low potential to remove inactivation and then rapidly shifting to higher potentials to achieve activation; subsequently, closure to the inactivated state occurs spontaneously to limit Ca2+ conductance. The range of membrane potentials at which channels can activate without becoming fully inactivated defines the physiological range for function, i.e., the window current. As shown in Figs. 2B and 6C, the window current lies between −40 and +10 mV for basal Ca2+ and Ba2+ conductance but is shifted toward more negative values (by ∼10 mV) in the presence of FPL. Our prior examination of resting membrane potentials in DVR pericytes and its depolarization in response to agonists (ANG II and endothelin) has shown a shift from −50 to −70 mV to −40 to −20 mV, within the window current range defined here (4, 44).

We extended our studies by testing the effects of other classical CaV blockers, calciseptine, mibefradil, and ω-agatoxin IVA. Calciseptine is a toxin derived from the black mamba that purportedly blocks L- over T- or N-type channels (39, 56). Despite the high sensitivity of isolated rabbit arterioles to calciseptine (22, 56), in a separate series of experiments, we could not demonstrate blockade of FPL-stimulated or unstimulated (basal) Ba2+ currents with that agent (Fig. 8, A and B). Calciseptine also failed to reverse ANG II-induced vasoconstriction, mitigating against an effect attributable to ruptured-patch methods (Fig. 8C). Given the otherwise strong evidence for L-type channels in this preparation (Figs. 1–7), we speculate that a calciseptine-insensitive CaV1.x splice variant exists in the renal medulla of the rat, possibly conferring some resistance to snake venoms. At 1 μM, mibefradil failed to block Ba2+ currents or ANG II-induced vasoconstriction (Fig. 9), providing evidence against T-type currents contaminating the results of prior protocols (Fig. 6) and also against participation of T-type channels in ANG II-induced vasoconstriction. At 10 μM, mibefradil dilated microperfused DVR, but that may well be attributable to L-type channel blockade at that concentration. Finally, despite the description of their expression in medullary vascular bundles, P/Q-type channel blockade with ω-agatoxin IVA failed to affect depolarization-induced inward Ba2+ currents (Fig. 10). We recognize that the failure to observe signature T- or P/Q-type currents does not rule out participation of such channels in DVR vasoactivity under other physiological conditions. Those channels may be present, but they may be dormant because of posttranslational modifications, internalization, or other inhibitory signaling processes that we have yet to define.

GRANTS

Studies in our laboratory were supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK-42495, DK-67621, and HL-68686.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe Y, Komori T, Miura K, Takada T, Imanishi M, Okahara T, Yamamoto K. Effects of the calcium antagonist nicardipine on renal function and renin release in dogs. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 5: 254–259, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreasen D, Friis UG, Uhrenholt TR, Jensen BL, Skott O, Hansen PB. Coexpression of voltage-dependent calcium channels Cav1.2, 21a, and 21b in vascular myocytes. Hypertension 47: 735–741, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ball CJ, Wilson DP, Turner SP, Saint DA, Beltrame JF. Heterogeneity of L- and T-channels in the vasculature: rationale for the efficacy of combined L- and T-blockade. Hypertension 53: 654–660, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao C, Lee-Kwon W, Silldorff EP, Pallone TL. KATP channel conductance of descending vasa recta pericytes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F1235–F1245, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carmines PK. Segment-specific effect of chloride channel blockade on rat renal arteriolar contractile responses to angiotensin II. Am J Hypertens 8: 90–94, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carmines PK, Fowler BC, Bell PD. Segmentally distinct effects of depolarization on intracellular [Ca2+] in renal arterioles. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 265: F677–F685, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Catterall WA, Striessnig J, Snutch TP, Perez-Reyes E. International Union of Pharmacology. XL. Compendium of voltage-gated ion channels: calcium channels. Pharmacol Rev 55: 579–581, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chou SY, Reiser I, Porush JG. Reversal of Na+ retention in chronic caval dogs by verapamil: contribution of medullary circulation. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 263: F642–F648, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conger JD, Falk SA. KCl and angiotensin responses in isolated rat renal arterioles: effects of diltiazem and low-calcium medium. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 264: F134–F140, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dickhout JG, Mori T, Cowley AW., Jr Tubulovascular nitric oxide crosstalk: buffering of angiotensin II-induced medullary vasoconstriction. Circ Res 91: 487–493, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dolphin AC. Calcium channel diversity: multiple roles of calcium channel subunits. Curr Opin Neurobiol 19: 237–244, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ertel EA, Campbell KP, Harpold MM, Hofmann F, Mori Y, Perez-Reyes E, Schwartz A, Snutch TP, Tanabe T, Birnbaumer L, Tsien RW, Catterall WA. Nomenclature of voltage-gated calcium channels. Neuron 25: 533–535, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng MG, Li M, Navar LG. T-type calcium channels in the regulation of afferent and efferent arterioles in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F331–F337, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feng MG, Navar LG. Angiotensin II-mediated constriction of afferent and efferent arterioles involves T-type Ca2+ channel activation. Am J Nephrol 24: 641–648, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng MG, Navar LG. Nitric oxide synthase inhibition activates L- and T-type Ca2+ channels in afferent and efferent arterioles. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F873–F879, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fenoy FJ, Kauker ML, Milicic I, Roman RJ. Normalization of pressure-natriuresis by nisoldipine in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 19: 49–55, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Findlay I. Physiological modulation of inactivation in L-type Ca2+ channels: one switch. J Physiol 554: 275–283, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordienko DV, Clausen C, Goligorsky MS. Ionic currents and endothelin signaling in smooth muscle cells from rat renal resistance arteries. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 266: F325–F341, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansell P, Nygren A, Ueda J. Influence of verapamil on regional renal blood flow: a study using multichannel laser-Doppler flowmetry. Acta Physiol Scand 139: 15–20, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hansell P, Sjoquist M, Ulfendahl HR. The calcium entry blocker verapamil increases red cell flux in the vasa recta of the exposed renal papilla. Acta Physiol Scand 134: 9–15, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansen PB, Jensen BL, Andreasen D, Friis UG, Skott O. Vascular smooth muscle cells express the α1A-subunit of a P/Q-type voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel, and it is functionally important in renal afferent arterioles. Circ Res 87: 896–902, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hansen PB, Jensen BL, Andreasen D, Skott O. Differential expression of T- and L-type voltage-dependent calcium channels in renal resistance vessels. Circ Res 89: 630–638, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hart P, Bakris GL. Calcium antagonists: do they equally protect against kidney injury? Kidney Int 73: 795–796, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayashi K, Nagahama T, Oka K, Epstein M, Saruta T. Disparate effects of calcium antagonists on renal microcirculation. Hypertens Res 19: 31–36, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayashi K, Ozawa Y, Wakino S, Kanda T, Homma K, Takamatsu I, Tatematsu S, Saruta T. Cellular mechanism for mibefradil-induced vasodilation of renal microcirculation: studies in the isolated perfused hydronephrotic kidney. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 42: 697–702, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayashi K, Wakino S, Homma K, Sugano N, Saruta T. Pathophysiological significance of T-type Ca2+ channels: role of T-type Ca2+ channels in renal microcirculation. J Pharm Sci 99: 221–227, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayashi K, Wakino S, Sugano N, Ozawa Y, Homma K, Saruta T. Ca2+ channel subtypes and pharmacology in the kidney. Circ Res 100: 342–353, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Honda M, Hayashi K, Matsuda H, Kubota E, Tokuyama H, Okubo K, Takamatsu I, Ozawa Y, Saruta T. Divergent renal vasodilator action of L- and T-type calcium antagonists in vivo. J Hypertens 19: 2031–2037, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inscho EW, Mason MJ, Schroeder AC, Deichmann PC, Stiegler KD, Imig JD. Agonist-induced calcium regulation in freshly isolated renal microvascular smooth muscle cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 569–579, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iversen BM, Arendshorst WJ. ANG II and vasopressin stimulate calcium entry in dispersed smooth muscle cells of preglomerular arterioles. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 274: F498–F508, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jensen BL, Friis UG, Hansen PB, Andreasen D, Uhrenholt T, Schjerning J, Skott O. Voltage-dependent calcium channels in the renal microcirculation. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 1368–1373, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee-Kwon W, Goo JH, Zhang Z, Silldorff EP, Pallone TL. Vasa recta voltage-gated Na+ channel Nav1.3 is regulated by calmodulin. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F404–F414, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li J, Stevens L, Klugbauer N, Wray D. Roles of molecular regions in determining differences between voltage dependence of activation of CaV3.1 and CaV12 calcium channels. J Biol Chem 279: 26858–26867, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loutzenhiser K, Loutzenhiser R. Angiotensin II-induced Ca2+ influx in renal afferent and efferent arterioles: differing roles of voltage-gated and store-operated Ca2+ entry. Circ Res 87: 551–557, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loutzenhiser R, Hayashi K, Epstein M. Divergent effects of KCl-induced depolarization on afferent and efferent arterioles. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 257: F561–F564, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu S, Roman RJ, Mattson DL, Cowley AW., Jr Renal medullary interstitial infusion of diltiazem alters sodium and water excretion in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 263: R1064–R1070, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neher E. Correction for liquid junction potentials in patch clamp experiments. Methods Enzymol 207: 123–131, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohishi M, Takagi T, Ito N, Terai M, Tatara Y, Hayashi N, Shiota A, Katsuya T, Rakugi H, Ogihara T. Renal-protective effect of T- and L-type calcium channel blockers in hypertensive patients: an amlodipine-to-benidipine changeover (ABC) study. Hypertens Res 30: 797–806, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohizumi Y. Application of physiologically active substances isolated from natural resources to pharmacological studies. Jpn J Pharmacol 73: 263–289, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ozawa Y, Hayashi K, Nagahama T, Fujiwara K, Saruta T. Effect of T-type selective calcium antagonist on renal microcirculation: studies in the isolated perfused hydronephrotic kidney. Hypertension 38: 343–347, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pallone TL. Vasoconstriction of outer medullary vasa recta by angiotensin II is modulated by prostaglandin E2. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 266: F850–F857, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pallone TL. Microdissected perfused vessels. Methods Mol Med 86: 443–456, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pallone TL, Cao C, Zhang Z. Inhibition of K+ conductance in descending vasa recta pericytes by ANG II. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F1213–F1222, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pallone TL, Huang JM. Control of descending vasa recta pericyte membrane potential by angiotensin II. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 282: F1064–F1074, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pallone TL, Work J, Myers RL, Jamison RL. Transport of sodium and urea in outer medullary descending vasa recta. J Clin Invest 93: 212–222, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parekh AB. Ca2+ microdomains near plasma membrane Ca2+ channels: impact on cell function. J Physiol 586: 3043–3054, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perez-Reyes E. Molecular physiology of low-voltage-activated T-type calcium channels. Physiol Rev 83: 117–161, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rhinehart K, Zhang Z, Pallone TL. Ca2+ signaling and membrane potential in descending vasa recta pericytes and endothelia. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F852–F860, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saruta T, Kanno Y, Hayashi K, Konishi K. Antihypertensive agents and renal protection: calcium channel blockers. Kidney Int Suppl 55: S52–S56, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sasaki H, Saiki A, Endo K, Ban N, Yamaguchi T, Kawana H, Nagayama D, Ohhira M, Oyama T, Miyashita Y, Shirai K. Protective effects of efonidipine, a T- and L-type calcium channel blocker, on renal function and arterial stiffness in type 2 diabetic patients with hypertension and nephropathy. J Atheroscler Thromb 16: 568–575, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sather WA, McCleskey EW. Permeation and selectivity in calcium channels. Annu Rev Physiol 65: 133–159, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Talavera K, Nilius B. Biophysics and structure-function relationship of T-type Ca2+ channels. Cell Calcium 40: 97–114, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Triggle DJ. Sites, mechanisms of action, and differentiation of calcium channel antagonists. Am J Hypertens 4: 422S–429S, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Turner MR, Pallone TL. Ion channel architecture of the renal microcirculation. Curr Hypertens Rev 2: 69–81, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yagil Y, Miyamoto M, Frasier L, Oizumi K, Koike H. Effects of CS-905, a novel dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker, on arterial pressure, renal excretory function, and inner medullary blood flow in the rat. Am J Hypertens 7: 637–646, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yunker AM, McEnery MW. Low-voltage-activated (“T-type”) calcium channels in review. J Bioenerg Biomembr 35: 533–575, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Q, Cao C, Mangano M, Zhang Z, Silldorff EP, Lee-Kwon W, Payne K, Pallone TL. Descending vasa recta endothelium is an electrical syncytium. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291: R1688–R1699, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Z, Cao C, Lee-Kwon W, Pallone TL. Descending vasa recta pericytes express voltage operated Na+ conductance in the rat. J Physiol 567: 445–457, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang Z, Huang JM, Turner MR, Rhinehart KL, Pallone TL. Role of chloride in constriction of descending vasa recta by angiotensin II. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 280: R1878–R1886, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang Z, Rhinehart K, Kwon W, Weinman E, Pallone TL. ANG II signaling in vasa recta pericytes by PKC and reactive oxygen species. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H773–H781, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang Z, Rhinehart K, Pallone TL. Membrane potential controls calcium entry into descending vasa recta pericytes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 283: R949–R957, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]