Abstract

Accumulation of continuous life stress (chronic stress) often causes gastric symptoms. Although central oxytocin has antistress effects, the role of central oxytocin in stress-induced gastric dysmotility remains unknown. Solid gastric emptying was measured in rats receiving acute restraint stress, 5 consecutive days of repeated restraint stress (chronic homotypic stress), and 7 consecutive days of varying types of stress (chronic heterotypic stress). Oxytocin and oxytocin receptor antagonist were administered intracerebroventricularly (icv). Expression of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) mRNA and oxytocin mRNA in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus was evaluated by real-time RT-PCR. The changes of oxytocinergic neurons in the PVN were evaluated by immunohistochemistry. Acute stress delayed gastric emptying, and the delayed gastric emptying was completely restored after 5 consecutive days of chronic homotypic stress. In contrast, delayed gastric emptying persisted following chronic heterotypic stress. The restored gastric emptying following chronic homotypic stress was antagonized by icv injection of an oxytocin antagonist. Icv injection of oxytocin restored delayed gastric emptying induced by chronic heterotypic stress. CRF mRNA expression, which was significantly increased in response to acute stress and chronic heterotypic stress, returned to the basal levels following chronic homotypic stress. In contrast, oxytocin mRNA expression was significantly increased following chronic homotypic stress. The number of oxytocin-immunoreactive cells was increased following chronic homotypic stress at the magnocellular part of the PVN. Icv injection of oxytocin reduced CRF mRNA expression induced by acute stress and chronic heterotypic stress. It is suggested that the adaptation mechanism to chronic stress may involve the upregulation of oxytocin expression in the hypothalamus, which in turn attenuates CRF expression.

Keywords: chronic homotypic stress, chronic heterotypic stress, corticotropin-releasing factor, hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis, paraventricular nucleus

functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorders are common in the general population. Functional GI disorders are multifactorial, since the pathophysiological mechanisms are variably combined in each patient. Stress is widely believed to play a major role in developing functional GI disorders. GI symptoms may develop because of the accumulation of continuous or repeated stress in some individuals; however, others are able to adapt to a stressful environment without developing GI symptoms. The mechanism by which the GI tract adapts to chronic stress remains unclear.

Previous animal studies demonstrated that solid meal gastric emptying is delayed by acute stress (10, 40). However, relatively few studies have been done under repeated chronic stress. Ochi et al. (31) showed that acute stress delays liquid gastric emptying, whereas repeated stress loading for 5 consecutive days accelerated liquid gastric emptying in rats. We have recently demonstrated that delayed solid gastric emptying observed in acute restraint stress was completely restored following chronic repeated stress (chronic homotypic stress) loading for 5 consecutive days in rats (53). This suggests that homeostatic adaptation may develop in response to chronic repeated stress.

We studied whether adaptation develops following chronic heterotypic (complicated) stress loading in rats. The rodents received different types of stress (water avoidance stress, force swimming stress, cold restraint stress, and restraint stress) for 7 consecutive days. The effects of different type of stress (acute restraint stress, chronic homotypic stress, and chronic heterotypic stress) on solid gastric emptying were studied. In contrast to chronic homotypic stress, gastric emptying was delayed following chronic heterotypic stress, suggesting that the rats failed to adapt to heterotypic stress.

Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) in the brain acts to influence motor function of the GI tract. Acute restraint stress delays solid gastric emptying via central CRF and peripheral autonomic nerves in rats (26, 39). Acute restraint stress stimulates CRF in the amygdala and paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus, resulting in activation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (8). CRF plays a dominant role to increase HPA axis activity and delays gastric emptying following acute stress in rats (20, 21). However, it remains unclear whether central CRF plays a major role in regulating HPA axis and gastric dysmotility following chronic stress.

Oxytocin is a cyclic nona-peptide hormone associated with female reproductive functions. Oxytocin is synthesized in the neurosecretory cells that are located in the PVN and supraoptic nucleus (SON) of the hypothalamus. The SON consists exclusively of magnocellular neurons. In contrast, the PVN consists of both magnocellular and parvocellular neurons. The magnocellular neurons are part of the hypothalamic-neurohypophysial system, whereas the parvocellular neurons constitute the central part of the HPA axis and project to the autonomic preganglionic neurons at the brain stem (11). Besides its well-known physiological functions like milk ejection and induction of labor, oxytocin plays an important role in regulating social behavior and positive social interactions in nonhuman mammals (27). In humans, intranasal administration of oxytocin was shown to have a substantial increase in trusting behavior (16).

Oxytocin is also known for its antistress and antianxiety effects. Oxytocin attenuates stress-induced activity of HPA axis and thus modulates the stress response in both males and females (28, 47). Oxytocin is released in the PVN in response to various stressors, such as shaker stress (30) and forced swimming stress (48) in rats. Restraint stress can induce c-fos expression in oxytocinergic magnocellular neuroendocrine cells in the SON and PVN in rats (24).

In response to psychological stressors, there is a dose-dependent effect of oxytocin in attenuating stress-induced HPA activation on neural circuits including the PVN and dorsal hippocampus. Oxytocin administration significantly attenuates both ACTH/corticosterone release and CRF mRNA expression in the PVN in response to acute restraint stress (46). This suggests that the anxiolytic and stress-attenuating effects of oxytocin are, at least in part, mediated by its inhibitory effects on CRF expression in the brain. A recent study demonstrated that water avoidance stress-induced stimulation of colonic motility is attenuated by central administration of oxytocin in rats (22).

We studied the role of central oxytocin in stress-induced gastric motor dysfunction following acute stress, chronic homotypic stress, and chronic heterotypic stress. PVN plays a major part in regulating stress responses in rats (43). To investigate the relationship between CRF and oxytocin in the PVN, we measured oxytocin mRNA and CRF mRNA expression in the PVN following acute, chronic homotypic, and heterotypic stress. We also studied the immunohistochemistry of oxytocin at the parvocellular and magnocellular subdivisions of the PVN following acute, chronic homotypic, and heterotypic stress. Our present study suggests that the central oxytocin may play an important role in regulating the adaptation mechanism to restore gastric motility following chronic stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats weighing 260–300 g. were housed in individual cages under conditions of controlled temperature (22–24°C) and illumination (12-h light cycle starting at 6:00 AM) for at least 7 days before the experiment. Rats were given ad libitum access to food and water. All experiments were started at 9:00 AM each day. Protocols describing the use of rats were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Zablocki Veterans Affairs Medical Center at Milwaukee and carried out in accordance with the National Institute of Health “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.” All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and to reduce the number of animal in experiments.

Acute Stress, Chronic Homotypic Stress, and Chronic Heterotypic Stress Loading

For acute stress loading, rats were placed on a wooden plate with their trunks wrapped in a confining harness for 90 min, as previously reported (53). The animal was able to move its limbs and head but not its trunk. This restraint stress has been used as a physical and psychogenic stress model in rodents (17, 45). For chronic homotypic stress, the rats received the same restraint stress loading for 5 consecutive days.

For chronic heterotypic stress, the rats received different types of stressors for 7 consecutive days, as previously reported (6). The stress paradigms used were water avoidance stress, force swimming stress, cold restraint stress, and restraint stress. Rodents were exposed to two different stressors each day for 7 days (Table 1). The specific conditions for each type of stress are as follows.

Table 1.

Chronic heterotypic stress protocol for 7 days comprising of different stressors

| Day | Stressor, AM | Stressor, PM |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | RS (90 min) | CRS (45 min) |

| 2 | FSS (20 min) | |

| 3 | RS (90 min) | WAS (60 min) |

| 4 | CRS (45 min) | |

| 5 | RS (90 min) | FSS (20 min) |

| 6 | WAS (60 min) | |

| 7 | RS (90 min) |

AM, ante meridiem; PM, post meridiem; RS, restraint stress; CRS, cold restraint stress; FSS, forced swimming stress; WAS, water avoidance stress.

Water avoidance stress.

Animals were placed on a platform (3 × 6 cm) in the middle of a plastic container (50 cm × 30 cm × 20 cm) filled with room temperature (RT) water to 1 cm below the height of the platform for 90 min. Control rats were placed on the same platform in a waterless container for 90 min.

Force swimming stress.

Animals were placed individually in a plastic tank (52 cm × 37 cm × 20 cm) filled with RT water to the depth of 15 cm for 20 min. The depth of the water forced the animal to swim or float without hindlimbs touching the bottom of the tank. Control rats were placed individually in a in a waterless container tank for 20 min.

Cold restraint stress.

Animals were kept restraint at 4°C for 45 min. Control rats were kept at RT for 45 min.

Measurement of Solid Gastric Emptying

Rats were fasted for 24 h prior to the measurement of gastric emptying. Preweighed pellets (1.6 g) were given, as previously reported (53). Immediately after finishing the feeding, the rats were subjected to restraint stress for 90 min. The rats that did not consume 1.6 g of food within 10 min were excluded from the study. After loading with restraint stress, the rats were euthanized by pentobarbital sodium (200 mg/kg ip). The stomach was surgically isolated and removed. The gastric contents were recovered from the stomach, dried, and weighed. Solid gastric emptying was calculated according to the following formula, as previously described (26, 53):

To evaluate gastric emptying in response to chronic stress, a similar emptying study was performed following restraint stress after the loading of 5 days of chronic homotypic stress and 7 days of chronic heterotypic stress.

Icv Administration of Oxytocin and Oxytocin Antagonist

Rats were placed in a stereotaxic apparatus and a 24-gauge guide cannula made from stainless steel tubing was implanted in the left ventricle, as previously reported (14). Rats were allowed to recover for 1 wk.

To investigate whether central oxytocin is involved in mediating gastric emptying, oxytocin (0.5 μg in 5 μl saline) was injected (icv) 30 min prior to stress loading via icv cannula by use of a microsyringe attached to polyethylene tubing. It has been shown that icv injection of oxytocin (0.3 μg) increases cardiovascular reactivity in response to some types of stressors in rats (34). Others showed that icv injection of oxytocin (500 pmol; 0.5 μg) inhibits accelerated colonic motility induced by water avoidance stress in rats (22). Oxytocin dissolved in isotonic saline was injected over a period of 10 s, as described previously (46, 47).

To investigate whether endogenous oxytocin is involved to restore gastric emptying following chronic homotypic stress, an oxytocin receptor antagonist, tocinoic acid (20 μg), was injected (icv) 30 min prior to stress loading. Icv injection of tocinoic acid (20 μg) has been shown to prevent the effect of oxytocin-induced social behavior in rats (42). Tocinoic acid (25 μg icv) antagonizes the inhibitory effect of oxytocin on colonic motility in rats (22). Saline (5 μl icv)-injected rats served as controls.

At the end of the experiment, rats were euthanized with pentobarbital sodium (200 mg/kg ip). The implantation site of icv cannula was confirmed by the presence of Evans blue (5%, 1 μl) after injection via the catheter, as previously reported (14).

Quantitative RT-PCR

The rat brain tissue micropunching technique (32) was applied for acquiring PVN tissue samples from specific regions with micropunchers. Briefly, rats were euthanized by decapitation. The brains were removed and cut into 450-μm coronal sections. Punches were collected from the left and right PVN (1.8 mm caudal to bregma; 0.4 mm lateral to midline; 7.6 mm ventral to the brain surface), as previously reported (51). All coordinates were based on the rat brain atlas (33).

Total RNA was extracted from the brain tissues using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer's instructions. Trace DNA contamination was removed by DNase digestion (Promega, Madison, WI). cDNA was synthesized from 3 μg total RNA by use of Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The following primers were designed to amplify rat CRF (81 bp; accession no. NM_031019), as previously reported (9): sense primer 5′-CCAGGGCAGAGCAGTTAGCT-3′, antisense primer 5′-CAAGCGCAACATTTCATTTCC-3′. The following primers were designed to amplify rat oxytocin (351 bp; accession no. M25649.1), as previously reported (50): sense primer 5′-GAACACCAACGCCATGGCCTGCCC-3′, antisense primer 5′-TCGGTGCGGCA GCCATCCGGGCTA-3′. For an internal control, the following primers were designed to amplify a rat β-actin fragment (106 bp; accession no. gi:118505324): sense primer 5′-TGGCACCACACCTTCTACAATGAG-3′, antisense primer 5′-GGGTCATCTTTTCACGGTTGG-3′, as previously reported (53).

Quantitative PCR was performed by using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TakaraBIO, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Amplification reactions were performed using a LightCycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics). Initial template denaturation was performed for 30 s at 95°C. The cycle profiles were programmed as follows: 5 s at 95°C (denaturation), 20 s at 60°C (annealing), and 15 s at 72°C (extension). Forty-five cycles of the profile were run, and the final cooling step was continued for 30 s at 40°C. Quantitative measurement of each mRNA sample was achieved by establishing a linear amplification curve from serial dilutions of each plasmid containing the amplicon sequence. Amplicon size and specificity were confirmed by melting curve analysis. The relative amount of each mRNA was normalized by the amount of β-actin mRNA, as previously reported (53).

Immunohistochemistry of Oxytocin

The rat brains were immediately removed following restraint stress loading. Tissue samples were fixed in 10% zinc formalin fixative for 2 days. The specimens were embedded in paraffin and mounted on standard cassettes and coronal paraffin sections (5 μm) were cut with a rotation-microtome at room temperature, transferred onto poly-l-lysine-coated slides (Fisher Scientific, Hanover, IL) and dried on a heating plate at 38°C, as previously reported (36, 41).

Brain sections were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated through descending concentrations of ethanol (52). The sections were treated with 0.5% sodium metaperiodate to block endogenous peroxidase for 15 min at room temperature. After washing with distilled water, the sections were incubated with trinitrobenzene sulfonate for 1 h and then washed thrice with phosphate-buffered saline, incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-oxytocin antibody (Peninsula Laboratories, San Carlos, CA; 1:5,000 dilution). After being washed, sections were incubated in biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Sections were then washed and placed in avidin-biotin peroxidase complex (Vector Laboratories). Immunoreactivity was visualized by incubation with 0.01% diaminobenzidine, 1% nickel chloride, and 0.0003% H2O2 for 10 min.

Oxytocin-immunoreactive cells in the PVN were counted at ×40 magnification by identifying them visually under Olympus CK40 microscope (Olympus America, Center Valley, PA). For quantitative assessment, the total number of oxytocin-immunoreactive cells was counted bilaterally in each subdivision of the PVN on the sections between −0.8 and −2.1 mm from the bregma identified with the Paxinos and Watson's atlas (33). The distinction between parvocellular and magnocellular subdivisions in the PVN was performed, as previously reported (15, 37).

Chemicals

Oxytocin and tocinoic acid were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO.

Statistical Analysis

Results were shown as means ± SE. One-way ANOVA and Student's t-test were used to determine the significance among groups. A P value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Pearson correlation analysis was performed for oxytocin and CRF mRNA expression.

RESULTS

Effect of Oxytocin and Oxytocin Antagonist on Solid Gastric Emptying in Response to Acute, Chronic Homotypic, and Chronic Heterotypic Stress

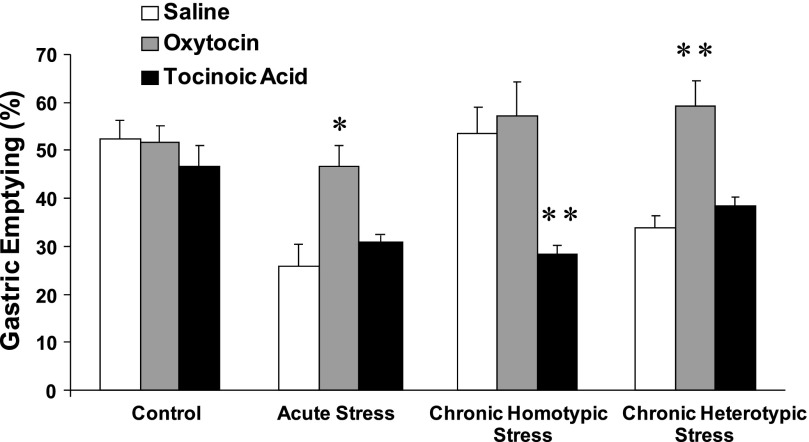

In nonrestrained rats, solid gastric emptying was 52.4 ± 3.1% (n = 6) 90 min after the feeding. Acute stress significantly delayed gastric emptying (25.2 ± 3.9%, n = 6, P < 0.01). Delayed gastric emptying was completely restored to 53.3 ± 3.6% (n = 6) after 5 consecutive days of chronic homotypic stress. In contrast, gastric emptying was still delayed (34.1 ± 4.3%, n = 6, P < 0.05) following chronic heterotypic stress.

Icv administration of oxytocin (0.5 μg) had no significant effect on solid gastric emptying in nonrestrained rats. In contrast, oxytocin (0.5 μg) significantly antagonized the inhibitory effects of acute stress on gastric emptying (46.1 ± 2.2%, n = 6), compared with that of saline (icv)-injected rats (25.6 ± 4.1%, n = 6, Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effect of intracerebroventricular (icv) injection of oxytocin and oxytocin antagonist on solid gastric emptying in response to acute, chronic homotypic, and heterotypic stress in rats. Acute restraint stress significantly delayed gastric emptying. Delayed gastric emptying observed in acute stress was restored by icv administration of oxytocin. Delayed gastric emptying was restored following chronic homotypic stress. Icv injection of tocinoic acid, which had no effects on gastric emptying in nonrestraint rats, significantly antagonized the restored gastric emptying following chronic homotypic stress. In contrast to chronic homotypic stress, gastric emptying was delayed following chronic heterotypic stress. Delayed gastric emptying was restored by icv administration of oxytocin following chronic heterotypic stress (n = 6, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with saline).

Icv injection of oxytocin (0.5 μg) also significantly improved the delayed solid gastric emptying induced by chronic heterotypic stress (59.4 ± 4.9%, n = 6), compared with that of saline (icv)-injected rats (33.6 ± 2.8%, n = 6, Fig. 1).

Icv injection of tocinoic acid (20 μg) had no significant effect on gastric emptying in nonrestrained rats. In contrast, icv injection of tocinoic acid significantly attenuated the restored gastric emptying following chronic homotypic stress (38.7 ± 2.4%, n = 6, P < 0.05), compared with that of saline-injected rats (52.8 ± 4.2%, Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

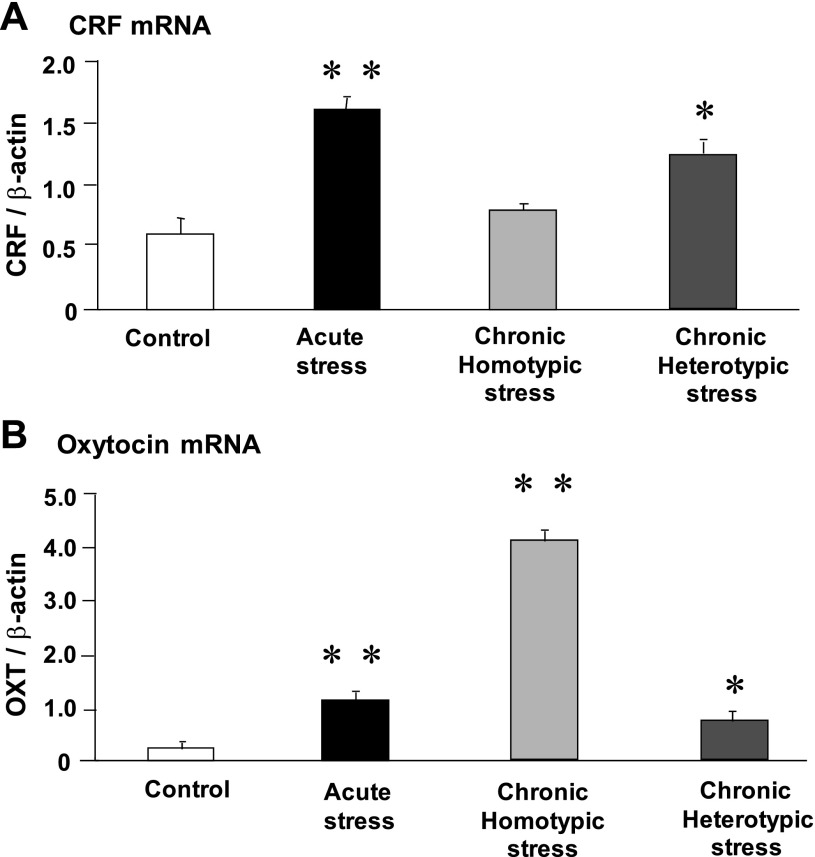

Effect of acute stress, chronic homotypic stress, and chronic heterotypic stress on corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF; A) and oxytocin (OXT; B) mRNA expression in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN). CRF mRNA expression showed a significant increase in response to acute stress. The increment of CRF mRNA was no longer observed following chronic homotypic stress. In contrast, chronic heterotypic stress significantly increased CRF mRNA expression. Oxytocin mRNA expression showed a significant increase in response to acute stress. Oxytocin mRNA expression at the PVN showed a more pronounced increase following chronic homotypic stress, compared with that of acute stress. The increase of oxytocin mRNA expression was much less following chronic complicated stress, compared with that of chronic homotypic stress. The mRNA expression was standardized with the ratio of internal control of β-actin (n = 6, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with controls).

Oxytocin and tocinoic acid were administered 30 min before the restraint stress loading. During 30-min observation, oxytocin and tocinoic acid did not evoke any significant changes in their general behavioral patterns including wakefulness and activity following chronic homotypic and heterotypic stress.

Effects of Acute Stress, Chronic Homotypic Stress, and Chronic Heterotypic Stress on Hypothalamic CRF mRNA Expression

CRF mRNA expression in the PVN was significantly increased in response to acute stress. In contrast, CRF mRNA expression was reduced to control levels by the 5th day of chronic homotypic stress. In contrast, CRF mRNA expression was significantly elevated following chronic heterotypic stress (Fig. 2A).

Effects of Acute, Chronic Homotypic, and Heterotypic Stress on Hypothalamic Oxytocin mRNA Expression

Oxytocin mRNA expression in the PVN of the hypothalamus was significantly increased following acute stress. The increase in oxytocin mRNA expression following chronic homotypic stress was much higher than that of acute stress. Following chronic heterotypic stress, oxytocin mRNA expression was significantly decreased, compared with that of chronic homotypic stress (Fig. 2B).

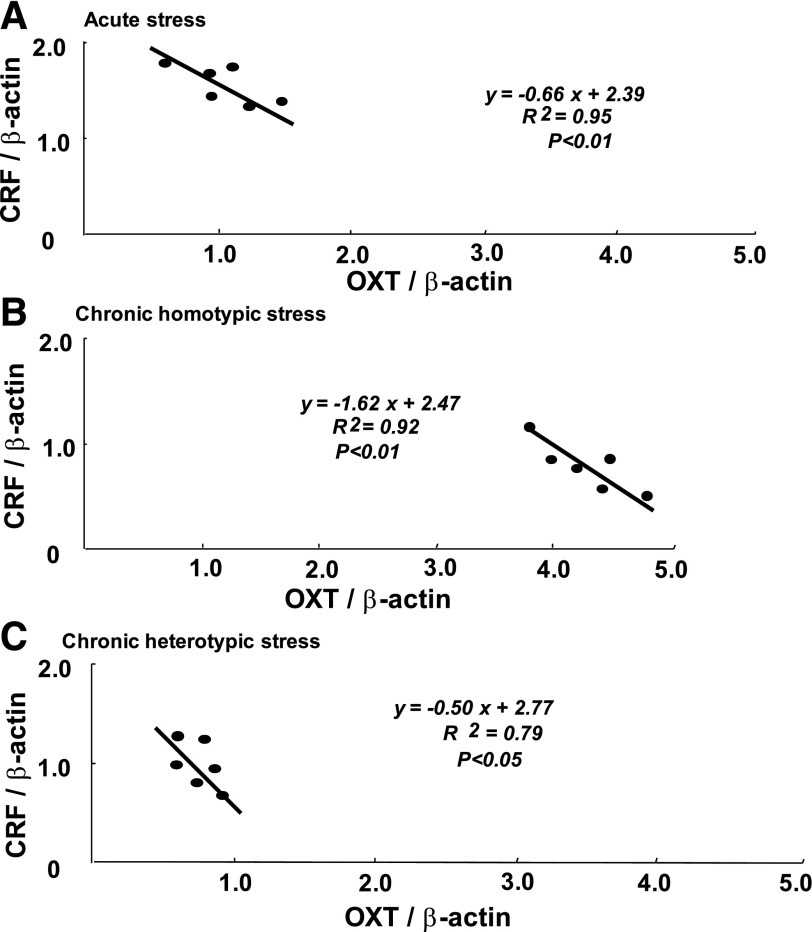

Correlation Between Oxytocin mRNA Expression and Gastric Emptying

There was a significant negative correlation observed between oxytocin mRNA and CRF mRNA expression in the PVN after acute stress (Fig. 3A), chronic homotypic stress (Fig. 3B), and chronic heterotypic stress groups (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Correlation between CRF mRNA and oxytocin mRNA expression in the PVN in response to acute stress (A), chronic homotypic stress (B), chronic heterotypic stress (C). There was a significant negative correlation observed between CRF mRNA and oxytocin mRNA expression in every stress loading (n = 6).

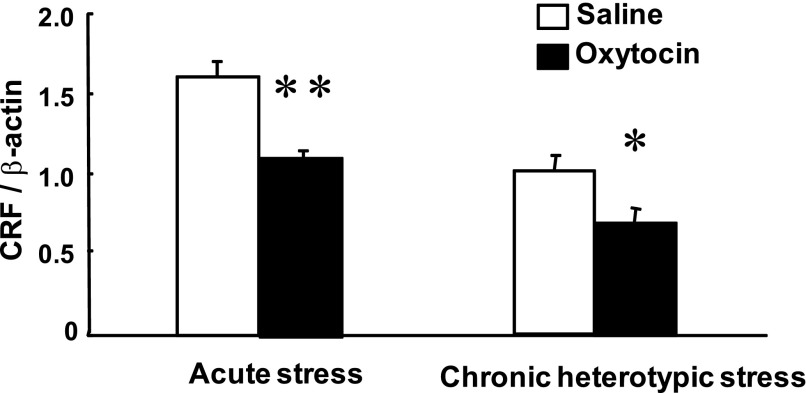

Effects of Oxytocin on Hypothalamic CRF mRNA Expression

Icv injection of oxytocin (0.5 μg) had no significant effect on CRF mRNA expression in the PVN in nonrestrained rats (data not shown). Icv injection of oxytocin significantly attenuated CRF mRNA expression in response to acute stress and chronic heterotypic stress (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Effects of icv injection of oxytocin on CRF mRNA expression in the PVN in response to acute stress and chronic heterotypic stress. Icv injection of oxytocin significantly attenuated the increase of CRF mRNA expression in response to acute stress and chronic heterotypic stress (n = 6, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with saline).

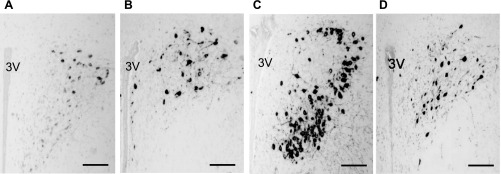

Immunohistochemistry of Oxytocin at the PVN Following Acute and Chronic Stress

The number of oxytocin-immunoreactive cells at the posterior magnocellular (PM) subdivisions of the PVN (−1.7 mm from bregma) was remarkably increased following chronic homotypic stress (Fig. 5C), compared with that of acute stress (Fig. 5B) and chronic heterotypic stress (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Immunohistochemistry of oxytocin in control (A), acute stress (B), chronic homotypic stress (C), and chronic heterotypic stress (D) at the PVN [3rd ventricle (3V); scale bar 250 μm].

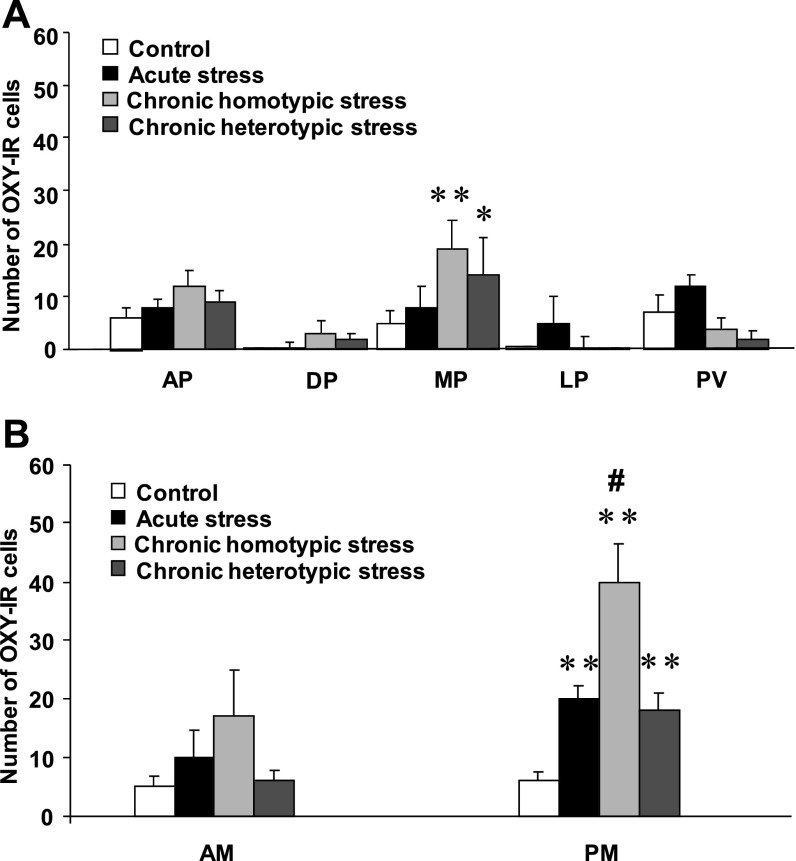

Statistical analysis showed that within the magnocellular subdivision of the PVN the number of oxytocin-immunoreactive cells in the PM part was significantly increased following acute stress (16.4 ± 1.9, n = 4), chronic homotypic stress (40.1 ± 6.2, n = 4), and chronic heterotypic stress (18.3 ± 3.4, n = 4) compared with the control (5.9 ± 1.5, n = 4 , P < 0.01) (Fig. 6B). The increase of oxytocin-immunoreactive cells at the PM subdivision was much more pronounced following chronic homotypic stress (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Number of oxytocin-immunoreactive (OXY-IR) cells in control, acute stress, chronic homotypic, and chronic heterotypic stress at the parvocellular subdivision (A) and magnocellular subdivision (B) of the PVN. AP, anterior parvocellular; MP, medial parvocellular; DP, dorsal parvocellular; LP, lateral parvocellular; PV, periventricular parvocellular; AM, anterior magnocellular; PM, posterior magnocellular; n = 4, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with control, #P < 0.01 compared with acute stress and chronic heterotypic stress.

Within the parvocellular subdivision of the PVN, medial parvocellular division showed an increase of the number of oxytocin-immunoreactive cells following chronic homotypic stress (18.6 ± 1.6, n = 4), compared with the control (5.2 ± 1.2, n = 4, P < 0.01). There were no significant differences in the number of oxytocin-immunoreactive cells at the other parvocellular subdivisions of the PVN (Fig. 6A).

There were no significant changes observed in oxytocin-immunoreactive cells in the other brain regions including bed nucleus of stria terminalis and the amygdala (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of OXY-IR cells in BNST and amygdala

| Mean Number of OXY-IR cells |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Acute stress | Chronic homotypic stress | Chronic heterotypic stress | |

| BNST | 7 ± 1.4 | 8.5 ± 1.1 | 8.8 ± 1.4 | 4 ± 0.74 |

| Amygdala | ||||

| CeM | 0 | 0.8 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 0.9 ± 0.4 |

| CeC | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 |

| MeAD | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.2 |

OXY-IR, oxytocin-immunoreactive; BNST, bed nucleus of stria terminalis; CeM, central amygdala medial; CeC, central amygdala capsular; MeAD, medial amygdala anterior dorsal).

DISCUSSION

We have recently demonstrated that delayed gastric emptying induced by acute restraint stress is completely restored following 5 consecutive days of repeated stress loading in rats (53) and mice (4). This suggests that homeostatic adaptation may develop in response to chronic repeated stress. When animals are subjected to stress, CRF is secreted from the hypothalamus and activates the HPA axis, resulting in the secretion of corticosterone from the adrenal cortex to guard against stress disorders (8). Acute restraint stress delays gastric emptying via central CRF and peripheral parasympathetic and/or sympathetic neural pathways in rats (26, 39).

Gastric emptying is attenuated when CRF is exogenously applied to the central nervous system (17, 40). We have recently shown that central administration of CRF significantly attenuates the restored gastric emptying following chronic homotypic stress in rats (53). This suggests that the sensitivity to central CRF in mediating delayed gastric emptying is not altered following chronic homotypic stress. Plasma cortisol levels, which are significantly increased in response to acute stress, are no longer observed following chronic homotypic stress (53), suggesting the attenuation of HPA axis following chronic homotypic stress. Our present study demonstrated that CRF mRNA expression in the PVN was significantly increased following acute restraint stress, whereas there was no longer a pronounced increase in CRF mRNA expression following chronic homotypic stress in rats. These results suggest that attenuation of HPA axis following chronic homotypic stress (53) is, at least in part, due to reduced CRF expression in the hypothalamus.

Although rats seem to adapt easily to chronic homotypic stress, it remains unknown whether adaptation develops following chronic heterotypic stress. After receiving different types of stress (water avoidance stress, force swimming stress, cold restraint stress, as well as restraint stress) for 7 consecutive days, delayed gastric emptying did not return to normal. This suggests that homeostatic adaptation may not develop following chronic heterotypic stress in rats. A recent study showed that a 9-day heterotypic chronic stress enhances the contractile activity of the colonic smooth muscle in rats (6). Our present study shows that CRF mRNA expression in the PVN is significantly elevated following chronic heterotypic stress.

Oxytocin has antistress and antianxiety effects. Oxytocin attenuates stress-induced activity of the HPA axis and thus modulates the regulation of the stress response in rodents (28, 47). Peripheral and central administration of oxytocin shows an anxiolytic behavioral pattern in both male (35, 44) and female rodents (5, 23). In response to various stressors, there is a dose-dependent effect of oxytocin in attenuating stress-induced HPA activation of neural circuits in the brain. Oxytocin administration attenuates ACTH and corticosterone release in response to acute restraint stress. Oxytocin administration also attenuates the increase in CRF mRNA expression in the PVN in response to acute restraint in rats (46). This suggests that both the anxiolytic and stress-attenuating effects of oxytocin are mediated by its inhibitory effects on CRF expression in the brain.

Our present study showed that icv injection of oxytocin significantly antagonized the inhibitory effects of acute stress on gastric emptying. We also showed that increased CRF mRNA expression in response to acute stress was attenuated by icv injection of oxytocin. Thus it is conceivable that the stimulatory effects of central oxytocin on delayed gastric emptying are mediated via its inhibitory effect on CRF expression during acute stress loading in rats.

Previous studies have shown that oxytocin-immunoreactive cells are localized in the magnocellular division of the PVN (38) and that oxytocin receptors are expressed in the parvocellular and magnocellular division of the PVN (29). Forced swimming stress increases oxytocin mRNA expression in the magnocellular neurons, but not the parvocellular neurons, of the PVN in rats (49). Restraint stress induces c-fos expression in oxytocinergic magnocellular neurons in the SON and PVN in rats (24).

CRF immunoreactivity has been demonstrated in a subset of magnocellular oxytocin neurons (18). Furthermore, synaptic associations between CRF and magnocellular oxytocin neurons of the PVN have also been demonstrated (12). In the present study we performed immunohistochemistry of oxytocin at the PVN following acute, chronic homotypic, and heterotypic stress. The number of oxytocin-immunoreactive cells at the magnocellular subdivision of the PVN was significantly increased following chronic homotypic stress.

It remains unknown whether central oxytocin is involved in the adaptation mechanism of following chronic stress. In our present study, the restored gastric emptying following chronic homotypic stress was antagonized by icv injection of an oxytocin antagonist. We also found that oxytocin mRNA expression of the PVN was significantly increased following chronic homotypic stress. In contrast, CRF mRNA expression of the PVN was significantly reduced following chronic homotypic stress. Thus it is highly likely that chronic homotypic stress upregulates oxytocin expression in the hypothalamus, resulting in attenuation of CRF-HPA pathway. As far as we know, this is the first demonstration that chronic homotypic stress upregulates oxytocin mRNA expression at the hypothalamus in rats.

The mechanism of upregulation of hypothalamic oxytocin following chronic homotypic stress remains unknown. Our previous study suggests the possibility of involvement of gastric ghrelin in the adaptation process following chronic homotypic stress in rats (53). Ghrelin is mainly produced in the fundus of the stomach and plays an important role in mediating gastric emptying in rodents (2, 3). It has been shown that the expression of gastric ghrelin is upregulated following chronic repeated stress in rats (31, 53) and mice (19). Plasma ghrelin levels are increased by β-adrenergic agonists (13) and sympathetic nerve stimulation (25) in rats. We have previously shown that restraint stress stimulates sympathetic pathway in rats (26). Thus the upregulation of ghrelin expression might be explained by the activated sympathetic nerves following chronic homotypic stress (19). Ghrelin released from the stomach has been shown to activate various neuropeptides and neuronal circuits at the central nervous system (1, 7). We cannot exclude the possibility that increased gastric ghrelin expression may directly or indirectly upregulate oxytocin expression at the hypothalamus during the adaptation process following chronic homotypic stress. Further investigation is needed for the effects of ghrelin on central oxytocin expression at the hypothalamus.

Icv injection of oxytocin significantly antagonized the inhibitory effects of chronic heterotypic stress on gastric emptying. Following chronic heterotypic stress, an increased CRF mRNA expression and attenuated oxytocin mRNA expression at the PVN were observed. The increased CRF mRNA expression in response to chronic heterotypic stress was significantly antagonized by icv injection of oxytocin. These results suggest that the effective pathway of central oxytocin in suppressing CRF expression is preserved following chronic heterotypic stress loading.

There was a significant negative correlation observed between hypothalamic CRF mRNA expression and oxytocin mRNA expression in response to acute stress, chronic homotypic stress, and chronic heterotypic stress. This indicates that oxytocin and CRF in the hypothalamus act to influence each other, like yin and yang, in mediating the responses to various type of stress under different conditions.

Functional GI disorders are frequently associated with continuous life stressors (chronic stress). In modern society, most individuals encounter both mental and social stress on a daily basis. In some individuals GI symptoms may develop as a result of the accumulation of daily stress, whereas others adapt to the stressful environment without developing GI symptoms. Our present study revealed that delayed gastric emptying observed in acute stress loading was completely restored following repeated chronic stress in rats. The adaptation mechanism involves upregulation of oxytocin expression and downregulation of CRF expression. Our study contributes to the better understanding of the mechanism of stress-induced functional GI disorders. How adaptation to stress takes place may lead to better treatments for functional GI disorders in humans.

GRANTS

This study was supported in part by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (RO1 DK62768, T. Takahashi).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1. Abizaid A, Liu ZW, Andrews ZB, Shanabrough M, Borok E, Elsworth JD, Roth RH, Sleeman MW, Picciotto MR, Tschop MH, Gao XB, Horvath TL. Ghrelin modulates the activity and synaptic input organization of midbrain dopamine neurons while promoting appetite. J Clin Invest 116: 3229–3239, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ariga H, Nakade Y, Tsukamoto K, Imai K, Chen C, Mantyh C, Pappas TN, Takahashi T. Ghrelin accelerates gastric emptying via early manifestation of antro-pyloric coordination in conscious rats. Regul Pept 146: 112–116, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ariga H, Tsukamoto K, Chen C, Mantyh C, Pappas TN, Takahashi T. Endogenous acyl ghrelin is involved in mediating spontaneous phase III-like contractions of the rat stomach. Neurogastroenterol Motil 19: 675–680, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Babygirija R, Zheng J, Ludwig K, Takahashi T. Central oxytocin is involved in restoring impaired gastric motility following chronic repeated stress in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 298: R157–R165, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bale TL, Davis AM, Auger AP, Dorsa DM, McCarthy MM. CNS region-specific oxytocin receptor expression: importance in regulation of anxiety and sex behavior. J Neurosci 21: 2546–2552, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Choudhury BK, Shi XZ, Sarna SK. Norepinephrine mediates the transcriptional effects of heterotypic chronic stress on colonic motor function. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 296: G1238–G1247, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Date Y, Shimbara T, Koda S, Toshinai K, Ida T, Murakami N, Miyazato M, Kokame K, Ishizuka Y, Ishida Y, Kageyama H, Shioda S, Kangawa K, Nakazato M. Peripheral ghrelin transmits orexigenic signals through the noradrenergic pathway from the hindbrain to the hypothalamus. Cell Metab 4: 323–331, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gomez F, Manalo S, Dallman MF. Androgen-sensitive changes in regulation of restraint-induced adrenocorticotropin secretion between early and late puberty in male rats. Endocrinology 145: 59–70, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gourcerol G, Gallas S, Mounien L, Leblanc I, Bizet P, Boutelet I, Leroi AM, Ducrotte P, Vaudry H, Jegou S. Gastric electrical stimulation modulates hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing factor-producing neurons during post-operative ileus in rat. Neuroscience 148: 775–781, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gue M, Peeters T, Depoortere I, Vantrappen G, Bueno L. Stress-induced changes in gastric emptying, postprandial motility, and plasma gut hormone levels in dogs. Gastroenterology 97: 1101–1107, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Herman JP, Flak J, Jankord R. Chronic stress plasticity in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Prog Brain Res 170: 353–364, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hisano S, Li S, Kagotani Y, Daikoku S. Synaptic associations between oxytocin-containing magnocellular neurons and neurons containing corticotropin-releasing factor in the rat magnocellular paraventricular nucleus. Brain Res 576: 311–318, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hosoda H, Kangawa K. The autonomic nervous system regulates gastric ghrelin secretion in rats. Regul Pept 146: 12–18, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ishiguchi T, Amano T, Matsubayashi H, Tada H, Fujita M, Takahashi T. Centrally administered neuropeptide Y delays gastric emptying via Y2 receptors in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 281: R1522–R1530, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kita I, Seki Y, Nakatani Y, Fumoto M, Oguri M, Sato-Suzuki I, Arita H. Corticotropin-releasing factor neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus are involved in arousal/yawning response of rats. Behav Brain Res 169: 48–56, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kosfeld M, Heinrichs M, Zak PJ, Fischbacher U, Fehr E. Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature 435: 673–676, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lenz HJ, Raedler A, Greten H, Vale WW, Rivier JE. Stress-induced gastrointestinal secretory and motor responses in rats are mediated by endogenous corticotropin-releasing factor. Gastroenterology 95: 1510–1517, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Levin MC, Sawchenko PE. Neuropeptide co-expression in the magnocellular neurosecretory system of the female rat: evidence for differential modulation by estrogen. Neuroscience 54: 1001–1018, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lutter M, Sakata I, Osborne-Lawrence S, Rovinsky SA, Anderson JG, Jung S, Birnbaum S, Yanagisawa M, Elmquist JK, Nestler EJ, Zigman JM. The orexigenic hormone ghrelin defends against depressive symptoms of chronic stress. Nat Neurosci 11: 752–753, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martinez V, Rivier J, Wang L, Tache Y. Central injection of a new corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) antagonist, astressin, blocks CRF- and stress-related alterations of gastric and colonic motor function. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 280: 754–760, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Martinez V, Wang L, Rivier J, Grigoriadis D, Tache Y. Central CRF, urocortins and stress increase colonic transit via CRF1 receptors while activation of CRF2 receptors delays gastric transit in mice. J Physiol 556: 221–234, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Matsunaga M, Konagaya T, Nogimori T, Yoneda M, Kasugai K, Ohira H, Kaneko H. Inhibitory effect of oxytocin on accelerated colonic motility induced by water-avoidance stress in rats. Neurogastroenterol Motil 21: 856–e59, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McCarthy MM, McDonald CH, Brooks PJ, Goldman D. An anxiolytic action of oxytocin is enhanced by estrogen in the mouse. Physiol Behav 60: 1209–1215, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Miyata S, Itoh T, Lin SH, Ishiyama M, Nakashima T, Kiyohara T. Temporal changes of c-fos expression in oxytocinergic magnocellular neuroendocrine cells of the rat hypothalamus with restraint stress. Brain Res Bull 37: 391–395, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mundinger TO, Cummings DE, Taborsky GJ., Jr Direct stimulation of ghrelin secretion by sympathetic nerves. Endocrinology 147: 2893–2901, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nakade Y, Tsuchida D, Fukuda H, Iwa M, Pappas TN, Takahashi T. Restraint stress delays solid gastric emptying via a central CRF and peripheral sympathetic neuron in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R427–R432, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Neumann ID. Brain oxytocin: a key regulator of emotional and social behaviours in both females and males. J Neuroendocrinol 20: 858–865, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Neumann ID. Involvement of the brain oxytocin system in stress coping: interactions with the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Prog Brain Res 139: 147–162, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Neumann ID, Torner L, Wigger A. Brain oxytocin: differential inhibition of neuroendocrine stress responses and anxiety-related behaviour in virgin, pregnant and lactating rats. Neuroscience 95: 567–575, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nishioka T, Anselmo-Franci JA, Li P, Callahan MF, Morris M. Stress increases oxytocin release within the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Brain Res 781: 56–60, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ochi M, Tominaga K, Tanaka F, Tanigawa T, Shiba M, Watanabe T, Fujiwara Y, Oshitani N, Higuchi K, Arakawa T. Effect of chronic stress on gastric emptying and plasma ghrelin levels in rats. Life Sci 82: 862–868, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Palkovits M. Isolated removal of hypothalamic or other brain nuclei of the rat. Brain Res 59: 449–450, 1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates (3rd ed.) San Francisco, CA: Academic, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Petersson M, Uvnas-Moberg K. Effects of an acute stressor on blood pressure and heart rate in rats pretreated with intracerebroventricular oxytocin injections. Psychoneuroendocrinology 32: 959–965, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ring RH, Malberg JE, Potestio L, Ping J, Boikess S, Luo B, Schechter LE, Rizzo S, Rahman Z, Rosenzweig-Lipson S. Anxiolytic-like activity of oxytocin in male mice: behavioral and autonomic evidence, therapeutic implications. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 185: 218–225, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sakata I, Tanaka T, Yamazaki M, Tanizaki T, Zheng Z, Sakai T. Gastric estrogen directly induces ghrelin expression and production in the rat stomach. J Endocrinol 190: 749–757, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sawchenko PE, Swanson LW. Immunohistochemical identification of neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus that project to the medulla or to the spinal cord in the rat. J Comp Neurol 205: 260–272, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sawchenko PE, Swanson LW, Vale WW. Corticotropin-releasing factor: co-expression within distinct subsets of oxytocin-, vasopressin-, and neurotensin-immunoreactive neurons in the hypothalamus of the male rat. J Neurosci 4: 1118–1129, 1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tache Y, Bonaz B. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptors and stress-related alterations of gut motor function. J Clin Invest 117: 33–40, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tache Y, Maeda-Hagiwara M, Turkelson CM. Central nervous system action of corticotropin-releasing factor to inhibit gastric emptying in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 253: G241–G245, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Thomas MA, Lemmer B. The use of heat-induced hydrolysis in immunohistochemistry on angiotensin II (AT1) receptors enhances the immunoreactivity in paraformaldehyde-fixed brain tissue of normotensive Sprague-Dawley rats. Brain Res 1119: 150–164, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Thompson MR, Callaghan PD, Hunt GE, Cornish JL, McGregor IS. A role for oxytocin and 5-HT(1A) receptors in the prosocial effects of 3,4 methylenedioxymethamphetamine (“ecstasy”). Neuroscience 146: 509–514, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ulrich-Lai YM, Herman JP. Neural regulation of endocrine and autonomic stress responses. Nat Rev Neurosci 10: 397–409, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Waldherr M, Neumann ID. Centrally released oxytocin mediates mating-induced anxiolysis in male rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 16681–16684, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Williams CL, Villar RG, Peterson JM, Burks TF. Stress-induced changes in intestinal transit in the rat: a model for irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 94: 611–621, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Windle RJ, Kershaw YM, Shanks N, Wood SA, Lightman SL, Ingram CD. Oxytocin attenuates stress-induced c-fos mRNA expression in specific forebrain regions associated with modulation of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal activity. J Neurosci 24: 2974–2982, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Windle RJ, Shanks N, Lightman SL, Ingram CD. Central oxytocin administration reduces stress-induced corticosterone release and anxiety behavior in rats. Endocrinology 138: 2829–2834, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wotjak CT, Ganster J, Kohl G, Holsboer F, Landgraf R, Engelmann M. Dissociated central and peripheral release of vasopressin, but not oxytocin, in response to repeated swim stress: new insights into the secretory capacities of peptidergic neurons. Neuroscience 85: 1209–1222, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wotjak CT, Naruo T, Muraoka S, Simchen R, Landgraf R, Engelmann M. Forced swimming stimulates the expression of vasopressin and oxytocin in magnocellular neurons of the rat hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Eur J Neurosci 13: 2273–2281, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Xi D, Kusano K, Gainer H. Quantitative analysis of oxytocin and vasopressin messenger ribonucleic acids in single magnocellular neurons isolated from supraoptic nucleus of rat hypothalamus. Endocrinology 140: 4677–4682, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhang ZH, Kang YM, Yu Y, Wei SG, Schmidt TJ, Johnson AK, Felder RB. 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 activity in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus modulates sympathetic excitation. Hypertension 48: 127–133, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhao Z, Sakata I, Okubo Y, Koike K, Kangawa K, Sakai T. Gastric leptin, but not estrogen and somatostatin, contributes to the elevation of ghrelin mRNA expression level in fasted rats. J Endocrinol 196: 529–538, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zheng J, Dobner A, Babygirija R, Ludwig K, Takahashi T. Effects of repeated restraint stress on gastric motility in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R1358–R1365, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]