Abstract

We have previously reported that preconditioning of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) with diazoxide (DZ) significantly improved cell survival via NF-κB signaling. Since micro-RNAs (miRNAs) are critical regulators of a wide variety of biological events, including apoptosis, proliferation, and differentiation, it is likely that DZ-induced survival is mediated by miRNAs. Here we show that miR-146a expressed during preconditioning with DZ is a key regulator of stem cell survival. Treatment of MSCs with DZ (200 μM) markedly increased miR-146a expression and promoted cell survival, as evaluated by lactate dehydrogenase release and transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling staining. Interestingly, blocking NF-κB by IKK-γ NEMO binding domain inhibitor peptide did not induce miR-146a expression, indicating NF-κB regulates miR-146a expression. Moreover, blockade of miR-146a expression by antisense miR-146a inhibitor abolished DZ-induced cytoprotective effects, suggesting a critical role of miR-146a in MSC survival. Computational analysis found a consensus putative target site of miR-146a relevant to apoptosis in the 3′ untranslated region of Fas mRNA. The role of Fas as a target gene was substantiated by abrogation of miR-146a, which markedly increased Fas protein expression. This was verified by luciferase reporter assay, which showed that forced expression of miR-146a downregulated Fas expression via targeting its 3′-UTR of this gene. Taken together, these data demonstrated that cytoprotection afforded by preconditioning of MSCs with DZ was regulated by miR-146a induction, which may be a novel therapeutic target in cardiac ischemic diseases.

Keywords: apoptosis, preconditioning

micro-rnas (mirnas) are small noncoding, single-stranded RNAs of 19–23 nucleotides that play critical roles in the coordination of a wide variety of processes, including differentiation, proliferation, death, and metabolism (13). miRNAs are transcribed from normal genes, and their precursor transcripts are enzymatically processed to a mature and active form by Drosha and Dicer enzyme complexes (14). miRNAs regulate more than 30% of the protein-coding genes by binding to partly complementary base pairs in 3′-untranslated regions (UTRs) of mRNAs and thereby interfering with translation. Recently, a number of studies have demonstrated that miRNAs are key regulators of stem cell function and involved in regulation of stem cell survival, as well as their differentiation into adipocyte, cardiac, neural, and hematopoietic lineages (8). Since miRNAs are involved in most major cellular functions, including stem cell apoptosis, they have been regarded as novel therapeutic targets for various diseases, such as cancer and ischemic heart diseases.

Preconditioning of stem cells has been regarded as a powerful approach for successful transplantation therapy, which can be duplicated with ischemic preconditioning, pharmacological preconditioning, and genetic modulation of stem cells (9). In particular, the mitoKATP channel opener, diazoxide (DZ), has been widely demonstrated to suppress cell apoptosis and promote cell survival (20, 21). DZ induces succinate dehydrogenase inhibition, mitochondrial depolarization, protein kinase C activation, and involvement of a potassium conductance-independent pathway for cellular protection (6, 27, 30). Our laboratory has previously reported that preconditioning with DZ promotes survival and angiomyogenic potential of mesenchymal stem cell (MSCs) in the infarcted heart via NF-κB signaling (1). It is noteworthy that miRNAs participate in hypoxic preconditioning of cardiomyocytes and hepatocytes (16, 23, 31), and our laboratory has also previously demonstrated that ischemic preconditioning significantly improved survival of bone marrow-derived MSC via upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and its downstream miR-210 expression (11). However, the involvement of miRNAs during preconditioning of stem cells with DZ remains to be investigated.

miR-146a has been previously reported as a key factor for innate immune system in balance toward cell survival (18). In addition, miR-146a appeared to modulate epithelial cell survival through upregulation of Bcl-xl and STAT3 (15) and is also associated with the risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (32). However, a functional role of miR-146a in survival and cytoprotection of stem cell is unknown. In the present study, we show NF-κB-dependent miR-146a is critically involved in cytoprotection of MSCs afforded by preconditioning with DZ, and it could be a novel therapeutic target for stem cell transplantation therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and culture of MSCs.

Bone marrow-derived MSCs were purified from young male Fischer-344 rats by flushing the cavity of femurs, as previously described (11). All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the standard human care guidelines of the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use of Committee of University of Cincinnati, which conforms to National Institutes of Health guideline.

Preconditioning of MSCs with DZ.

Native MSCs were seeded at 5 × 105 cells per 60-mm cell culture dish. The cells were starved overnight for serum and glucose before preconditioning. DZ at concentration of 200 μM was added to MSC for 1 h, or 3 h for preconditioning, and the cells either were harvested for molecular studies at the end of preconditioning, or were further subjected to lethal anoxia for 16 h to induce apoptosis for survival studies. Cell survival was evaluated by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay using conditioned medium and transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) of the apoptotic cells from each treatment group.

LDH release assay.

Intracellular LDH release was measured by using an LDH assay kit (Diagnostic Chemicals) per instructions of the manufacturer.

miRNA isolation and detection.

Total RNA, including miRNAs, was extracted by using mirVana miR isolation kit, and miR-146a was detected by using mirVana quantitative reverse transcription-PCR miRNA detection kit (Ambion). Specific miR-146a primers from Ambion were used for quantitative reverse transcription-PCR.

Western blot analysis.

Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation of MSCs was performed by using an NE-PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagent kit (Pierce), per the manufacturer's instruction. The protein samples (40 μg) were electrophoresed using SDS polyacrylamide gel and electro-immunoblotted. The antibodies for phospho-NF-κB p65 (Ser 468) and Fas were purchased from Cell Signaling and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, respectively, and IKK-γ NEMO binding domain (NBD) inhibitor peptide was obtained from IMGENEX.

TUNEL assay.

TUNEL-positive apoptotic cell death was analyzed by in situ cell death detection kit, according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Roche). For quantification, the number of TUNEL-positive nuclei were counted in at least five randomly selected high-power fields (magnification ×200) with three independent samples.

Transfection with miRNA inhibitor.

To knock down miR-146a, transfection was performed with anti-miR-146a (antisense miR specific inhibitor, Ambion) and siPORT NeoFx Transfection Agent (NeoFx; Ambion), as previously described (11).

Luciferase reporter assay.

Precursor miR-146a expression clone was constructed in a feline immunodeficiency virus-based lentiviral vector system (pEZX-miR-146a), and luciferase reporter construct containing the 3′-UTR of Fas (pEZX-Luc-Fas 3′-UTR) was designed to encompass the miR-146a binding sites (GeneCopoeia). Luciferase assay was performed by using the dual-luciferase reporter assay system kit (Promega), as previously described (11).

Statistical analysis.

All values were expressed as means ± SE. Comparison between two mean values was made by an unpaired Student two-tailed t-test, and between three or more groups was evaluated by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc analysis. Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Preconditioning with DZ enhances cytoprotection of MSCs.

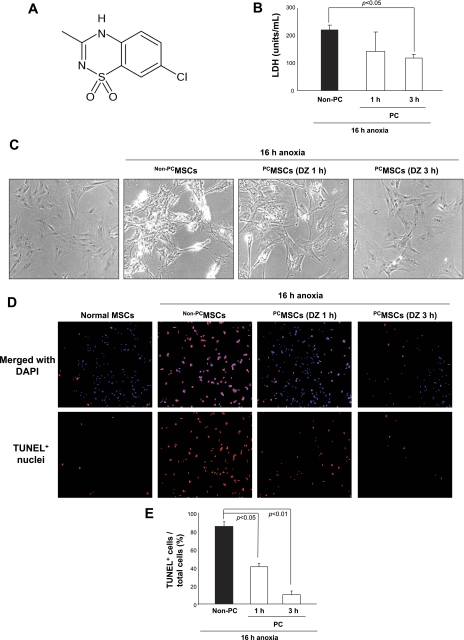

MSCs preconditioned by treatment with DZ for 1 or 3 h showed a significant level of protection upon subsequent exposure to 16-h lethal anoxia. Cellular injury, as evaluated by LDH release, was significantly reduced in preconditioned MSC (PCMSCs), both in 1- and 3-h treatment compared with non-preconditioned MSC (non-PCMSCs), as shown in Fig. 1A. Phase-contrast images showed hypercontracted morphology of non-PCMSCs when exposed to apoptosis for 16-h anoxia, whereas DZ pretreatment for 1 or 3 h prevented these morphological changes (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, the number of TUNEL-positive apoptotic nuclei was markedly reduced in PCMSCs (Fig. 1C), which was consistent with the LDH release data. These results indicate that preconditioning with DZ enhances cytoprotection of MSC survival against apoptosis.

Fig. 1.

Preconditioning with diazoxide (DZ) improves cytoprotection of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). A: chemical structure of DZ. B: DZ pretreatment attenuated cellular injury, as examined by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release subsequent to 16-h lethal anoxia. PC, preconditioned; non-PC, non-preconditioned. C: morphological changes of MSCs by 16-h anoxia included rounding off and shrinkage of cells, which was prevented by DZ treatment (magnification, ×200). PCMSCs, PC MSCs; non-PCMSCs, non-PC MSCs. D and E: representative fluorescence images and quantitative analysis of transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL)-positive nuclei, respectively, showing decreased number of apoptotic cells in PCMSCs [magnification ×200, green = TUNEL+ nuclei; blue = 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)].

Induction of miR-146a during preconditioning and its role in cytoprotection.

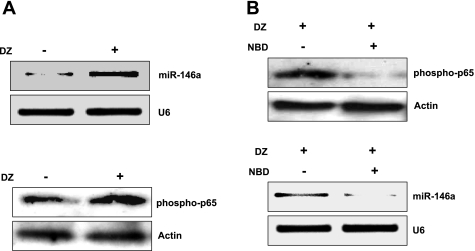

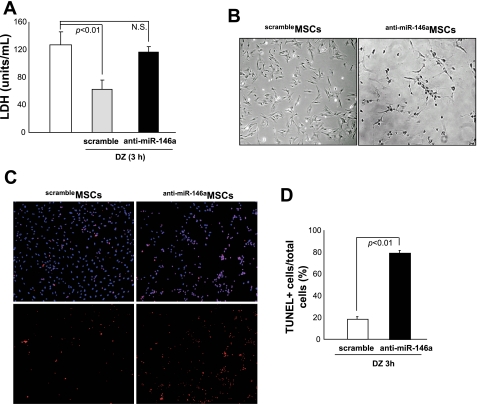

Since we previously observed a significant upregulation of NF-κB expression in PCMSCs by DZ treatment, we next examined a possible link between upregulation of NF-κB and miR-146a expression in PCMSCs. As shown in Fig. 2A, DZ preconditioning markedly increased miR-146a expression compared with non-PCMSCs. We also observed a parallel increase of nuclear NF-κB expression in PCMSC. To examine whether miR-146a expression is dependent on NF-κB, we blocked NF-κB expression by pretreatment of PCMSCs with NBD inhibitor peptide. NBD at a concentration of 100 μM effectively blocked NF-κB expression in PCMSCs, and, accordingly, inhibition of NF-κB suppressed miR-146a expression, suggesting miR-146a is downstream of NF-κB (Fig. 2B). To investigate the mechanistic participation of miR-146a in cytoprotection of MSCs, we performed loss-of-function study by transfection of MSCs with antisense miR-146a-specific inhibitor. Abrogation of miR-146a resulted in significant increase in cell damage after 16-h anoxia, as evaluated by LDH release assay, phase-contrast image analysis, and TUNEL staining (Fig. 3, A–C). These results clearly indicate that DZ-induced miR-146a plays an important role in cytoprotection of MSCs by prevention of apoptosis.

Fig. 2.

Preconditioning with DZ increases miR-146a expression via NF-κB. A: DZ pretreatment shows an increased miR-146a expression (quantitative RT-PCR) and phospho-p65 (Western blot) of MSCs. B: NEMO binding domain (NBD; inhibitor of p65) pretreatment blocked expression of both miR-146a and phospho-p65.

Fig. 3.

miR-146a is involved in cytoprotection of MSCs. MSCs were transfected with antisense miR-146a-specific inhibitor to block miR-146a expression (anti-miR-146aMSCs). anti-miR-146aMSCs abolished the DZ-induced cytoprotective effects under anoxic conditions, as examined by LDH release assay (A), morphological analysis (B), and TUNEL staining (C and D). scrambleMSCs, scramble MSCs.

Fas is the target of miR-146a for inhibition of apoptosis.

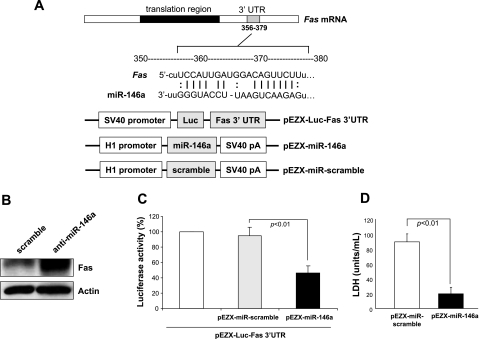

To search for the potential targets of miR-146a in prosurvival signaling in PCMSCs, we extensively examined databases for predicted miRNA targets and found a consensus putative target site of miR-146a relevant to apoptosis in the 3′-UTR of Fas mRNA (Fig. 4A). Fas (CD95) is a prototypic representative of the death receptor subgroup that belongs to the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor family. Since Fas has a critical role in apoptosis, we assessed its functional involvement in DZ-induced survival of MSCs. The results showed that abrogation of miR-146a in DZ-treated MSCs significantly increased Fas protein expression (Fig. 4B). Importantly, overexpression by precursor miR-146a expression plasmid (pEZX-miR-146a) reduced luciferase activity when cotransfected with the plasmid containing the 3′-UTR of the Fas gene (pEZX-Luc-Fas 3′-UTR), indicating that forced expression of miR-146a downregulates Fas expression via targeting its 3′-UTR (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, forced expression of miR-146a in native MSCs by transient transfection with pEZX-miR-146a markedly reduced LDH release (Fig. 4D), indicating a pivotal role of miR-146a in MSC survival induced by DZ preconditioning. Taken together, these results demonstrated that Fas is the major target of DZ-induced miR-146a expression for inhibition of apoptosis.

Fig. 4.

miR-146a targets Fas, a positive regulator of apoptosis. A: a putative target site of miR-146a highly conserved in the Fas mRNA 3′-untranslated region (UTR). B: Fas protein expression was upregulated by transfection with anti-miR-146a and the construction of pEZX-Luc-Fas 3′-UTR luciferase reporter plasmid and precursor miR-146a expression clone. C: cotransfection of MSCs with pEZX-Luc vector containing Fas 3′-UTR, together with a plasmid encoding miR-146a, showed decreased luciferase activity. D: LDH release assay indicated significantly reduced cytotoxicity in MSCs transfected with pEZX-miR-146a plasmid compared with that of pEZX-miR-scramble.

DISCUSSION

Stem cell transplantation therapy has emerged as an alternative strategy to recover the injured myocardium (2, 24). However, massive donor cell death is a great impediment for transplantation therapy (9, 17, 28). To overcome this obstacle, preconditioning of stem cell has been regarded as a powerful option to improve donor cell survival when transplanted into the infarcted heart (9, 11, 33). DZ has been widely used as a pharmacological preconditioning agent, and we have previously reported that preconditioning of MSCs with DZ significantly improved cell survival and angiomyogenic potential through NF-κB activation, thereby promoting myocardial recovery in the infarcted heart (1). In the present study, we demonstrated that miR-146a is involved in DZ-induced survival of MSCs through NF-κB activation.

miRNAs participate in a wide variety of physiological and pathological cellular processes. Currently, more than 600 miRNAs have been identified by molecular cloning and bioinformatics approaches (4). miRNAs regulate >30% of the genes in a cell, and an individual miRNA is capable of regulating the expression of multiple target genes (3). Previous studies have shown that miR-146a expression is altered in the inflammatory milieu, epithelial cells, and cancer cells (15, 18, 32). Furthermore, miR-146a was also upregulated by TNF-α and IL-1β in synovial fibroblasts from rheumatoid arthritis (19, 25), and introduction of miR-146a into a cervical cancer cell line promoted cell proliferation (29). In addition, miR-146a protects bronchial epithelial cells from apoptosis and promotes proliferation, which may be mediated by STAT3 signaling (15). In this study, we showed preconditioning with DZ significantly enhanced MSCs survival by upregulation of NF-κB activation and its downstream miR-146a. Consistent with our results, Taganov et al. (26) have shown that NF-κB positively regulates miR-146a/b expression, and miR-146a/b targets the TNF receptor-associated factor 6 and IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 genes, which encode adapter molecules downstream of Toll-like and cytokine receptors. Furthermore, it has recently been reported that NF-κB binding sites are required for the induction of miR-146a transcription in human T lympocytes, and an apoptotic factor, Fas-associated death domain, is a target gene of miR-146a (5). These studies, including our data, indicate that NF-κB is one of the transcription factors for miR-146a induction that plays a role in immune responses, as well as apoptotic processes.

A novel aspect of the present study was to identify Fas as a major target gene regulated by miR-146a during preconditioning by DZ. Fas (CD95) is the prototypic representative of the death receptor subgroup that belongs to the TNF receptor family, and interactions between Fas and Fas ligand (FasL, CD178) induces apoptosis and maintain immunological self-tolerance (7, 22). Apoptosis-inducing function of Fas is regulated by a number of mechanisms, including its submembrane localization, efficiency of receptor signaling complex assembly and activation, and bcl-2 family members in some circumstances (10). Activation of the Fas signaling pathway is initiated by binding of FasL or other receptor agonists, resulting in recruitment of the adaptor protein Fas-associated death domain, and the cysteinyl aspartic proteases, caspase-8 (and caspase-10 in humans) forms a proximal signaling platform called the death inducing signaling complex, which can be detected within seconds of receptor engagement and activates caspase-8/10, an essential step in the initiation of programmed cell death (12). The results of this study clearly indicated that miR-146a expression during preconditioning by DZ enhances survival of MSCs by directly targeting 3′-UTR of Fas, and its effect can be duplicated by overexpression of miR-146a, which could simulate the effect of DZ preconditioning, suggesting miR-146a plays a critical role in anti-apoptosis. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to identify miR-146a as a negative regulator of Fas gene.

In conclusion, this study strongly suggests that miR-146a induced by preconditioning with DZ is a potent and promising target to enhance stem cell survival under ischemic condition. Approaches to elevate miR-146a would accelerate stem cell viability of engraftment in the infarcted myocardium, and it would be a potential target in cardiac ischemic diseases.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R37-HL074272, HL-080686, HL087246 (M. Ashraf), HL087288, and HL089535 (K. H. Haider).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1.Afzal MR, Haider KH, Idris NM, Jiang S, Ahmed RP, Ashraf M. Preconditioning promotes survival and angiomyogenic potential of mesenchymal stem cells in the infarcted heart via NF-kappaB signaling. Antioxid Redox Signal 12: 693–702, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anversa P, Leri A, Rota M, Hosoda T, Bearzi C, Urbanek K, Urbanek J, Bolli R. Stem cells, myocardial regeneration, and methodological artifacts. Stem Cells 25: 589–601, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136: 215–233, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berezikov E, Cuppen E, Plasterk RH. Approached to microRNA discovery. Nat Genet 38, Suppl: S2–S7, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curtale G, Citarella F, Carissimi C, Goldoni M, Carucci N, Fulci V, Franceschini D, Meloni F, Barnaba V, Macino G. An emerging player in the adaptive immune response: microRNA-146a is a modulator of IL-2 expression and AICD in T lymphocytes. Blood 115: 265–273, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dzeja PP, Bast P, Ozcan C, Valverde A, Holmuhamedov EL, Van Wylen DG, Terzic A. Targeting nucleotide-requiring enzymes: implications for diazoxide-induced cardioprotection. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284: H1048–H1056, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fulda S, Meyer E, Friesen C, Susin SA, Kroemer G, Debatin KM. Cell type specific involvement of death receptor and mitochondrial pathways in drug-induced apoptosis. Oncogene 20: 1063–1075, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gangaraju VK, Lin H. MicroRNAs: key regulators of stem cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10: 116–125, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haider KH, Ashraf M. Strategies to promote donor cell survival: combining preconditioning approach with stem cell transplantation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 45: 554–566, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hengartner MO. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature 407: 770–776, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim HW, Haider KH, Jiang S, Ashraf M. Ischemic preconditioning augments survival of stem cells via miR-210 expression by targeting caspase-8-associated protein 2. J Biol Chem 284: 33161–33168, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kischkel FC, Hellbardt S, Behrmann I, Germer M, Pawlita M, Krammer PH, Peter ME. Cytotoxicity-dependent APO-1 (Fas/CD95)-associated proteins form a death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) with the receptor. EMBO J 14: 5579–5588, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science 294: 853–858, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lau NC, Lim LP, Weinstein EG, Bartel DP. An abundant class of tiny RNAs with probable regulatory roles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 294: 858–862, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu X, Nelson A, Wang X, Kanaji N, Kim M, Sato T, Nakanishi M, Li Y, Sun J, Michalski J, Patil A, Basma H, Rennard SI. MicroRNA-146a modulates human bronchial epithelial cell survival in response to the cytokine-induced apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 380: 177–182, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lusardi TA, Farr CD, Faulkner CL, Pignataro G, Yang T, Lan J, Simon RP, Saugstad JA. Ischemic preconditioning regulates expression of microRNAs and a predicted target, MeCP2, in mouse cortex. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 30: 744–756, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muller-Ehmsen J, Whittaker P, Kloner RA, Dow JS, Sakoda T, Long TI, Laird PW, Kedes L. Survival and development of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes transplanted into adult myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol 34: 107–116, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nahid MA, Pauley KM, Satoh M, Chan EK. miR-146a is critical for endotoxin-induced tolerance: implication in innate immunity. J Biol Chem 284: 34590–34599, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakasa T, Miyaki S, Okubo A, Hashimoto M, Nishida K, Ochi M, Asahara H. Expression of microRNA-146 in rheumatoid arthritis synovial tissue. Arthritis Rheum 58: 1284–1292, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niagara MI, Haider KH, Jiang S, Ashraf M. Pharmacologically preconditioned skeletal myoblasts are resistant to oxidative stress and promote angiomyogenesis via release of paracrine factors in the infarcted heart. Circ Res 100: 545–555, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rajapakse N, Kis B, Horiguchi T, Snipes J, Busija D. Diazoxide pretreatment induces delayed preconditioning in astrocytes against oxygen glucose deprivation and hydrogen peroxide-induced toxicity. J Neurosci Res 73: 206–214, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramaswamy M, Cleland SY, Cruz AC, Siegel RM. Many checkpoints on the road to cell death: regulation of Fas-FasL interactions and Fas signaling in peripheral immune responses. Results Probl Cell Differ 49: 17–47, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rane S, He M, Sayed D, Vashistha H, Malhotra A, Sadoshima J, Vatner DE, Vatner SF, Abdellatif M. Downregulation of miR-199a derepresses hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha and sirtuin 1 and recapitulates hypoxia preconditioning in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res 104: 879–886, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanchez A, Garcia-Sancho J. Cardiac repair by stem cells. Cell Death Differ 14: 1258–1261, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stanczyk J, Pedrioli DM, Brentano F, Sanchez-Pernaute O, Kolling C, Gay RE, Detmar M, Gay S, Kyburz D. Altered expression of microRNA in synovial fibroblasts and synovial tissue in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 58: 1001–1009, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Chang KJ, Baltimore D. NF-kappaB-dependent induction of microRNA miR-146, an inhibitor targeted to signaling proteins of innate immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 12481–12486, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takashi E, Wang Y, Ashraf M. Activation of mitochondrial K(ATP) channel elicits late preconditioning against myocardial infarction via protein kinase C signaling pathway. Circ Res 85: 1146–1153, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toma C, Pittenger MF, Cahill KS, Byrne BJ, Kessler PD. Human mesenchymal stem cells differentiate to a cardiomyocyte phenotype in the adult murine heart. Circulation 105: 93–98, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang X, Tang S, Le SY, Lu R, Rader JS, Meyers C, Zheng ZM. Aberrant expression of oncogenic and tumor-suppressive microRNAs in cervical cancer is required for cancer cell growth. PLoS One 3: e2557, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Takashi E, Xu M, Ayub A, Ashraf M. Downregulation of protein kinase C inhibits activation of mitochondrial K(ATP) channels by diazoxide. Circulation 104: 85–90, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu CF, Yu CH, Li YM. Regulation of hepatic microRNA expression in response to ischemic preconditioning following ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. OMICS 13: 513–520, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu T, Zhu Y, Wei QK, Yuan Y, Zhou F, Ge YY, Yang JR, Su H, Zhuang SM. A functional polymorphism in the miR-146a gene is associated with the risk for hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis 29: 2126–2131, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang M, Methot D, Poppa V, Fujio Y, Walsh K, Murry CE. Cardiomyocyte grafting for cardiac repair: graft cell death and anti-death strategies. J Mol Cell Cardiol 33: 907–921, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]