Abstract

As much as 50% of cardiac output can be distributed to the skin in the hyperthermic human, and therefore the control of cutaneous vascular conductance (CVC) becomes critical for the maintenance of blood pressure. Little is known regarding the magnitude of cutaneous vasoconstriction in profoundly hypotensive individuals while heat stressed. This project investigated the hypothesis that leading up to and during syncopal symptoms associated with combined heat and orthostatic stress, reductions in CVC are inadequate to prevent syncope. Using a retrospective study design, we evaluated data from subjects who experienced syncopal symptoms during lower body negative pressure (N = 41) and head-up tilt (N = 5). Subjects were instrumented for measures of internal temperature, forearm skin blood flow, arterial pressure, and heart rate. CVC was calculated as skin blood flow/mean arterial pressure × 100. Data were obtained while subjects were normothermic, immediately before an orthostatic challenge while heat stressed, and at 5-s averages for the 2 min preceding the cessation of the orthostatic challenge due to syncopal symptoms. Whole body heat stress increased internal temperature (1.25 ± 0.3°C; P < 0.001) and CVC (29 ± 20 to 160 ± 58 CVC units; P < 0.001) without altering mean arterial pressure (83 ± 7 to 82 ± 6 mmHg). Mean arterial pressure was reduced to 57 ± 9 mmHg (P < 0.001) immediately before the termination of the orthostatic challenge. At test termination, CVC decreased to 138 ± 61 CVC units (P < 0.001) relative to before the orthostatic challenge but remained approximately fourfold greater than when subjects were normothermic. This negligible reduction in CVC during pronounced hypotension likely contributes to reduced orthostatic tolerance in heat-stressed humans. Given that lower body negative pressure and head-up tilt are models of acute hemorrhage, these findings have important implications with respect to mechanisms of compromised blood pressure control in the hemorrhagic individual who is also hyperthermic (e.g., military personnel, firefighters, etc.).

Keywords: skin blood flow, baroreceptors, hyperthermia, orthostasis

under heat stress conditions human skin blood flow is estimated to increase from ∼300 ml/min upward to 7.5 l/min, resulting in the capacity for 50% or more of cardiac output being directed to the skin (25, 27). To maintain blood pressure in the face of pronounced increases in systemic vascular conductance associated with cutaneous vasodilation, cardiac output increases whereas vascular conductance to many noncutaneous beds decreases. Based on these values and with the use of a normothermic cardiac output of 6 l/min, cutaneous vascular conductance (CVC) represents ∼5% of the systemic vascular conductance when subjects are normothermic, but with the capacity of being >50% of the systemic vascular conductance during heat stress conditions. Therefore, the neural control of CVC has minimal influence on blood pressure control in normothermic individuals but will significantly influence arterial pressure while heat stressed.

Combining heat and orthostatic stresses in humans leads to an increased incidence of hypotension associated with pronounced and consistent reductions in tolerance during upright tilt (18, 44), gravitational acceleration (1), and simulated hemorrhage via lower body negative pressure (LBNP) (5, 13, 14, 43). Highlighting these observations, ∼85% of heat-stressed subjects were not able to tolerate 3 min of 40 mmHg LBNP without symptoms of ensuing syncope, whereas 100% of these subjects were able to tolerate this LBNP when normothermic (14, 43).

Although while heat stressed the skin serves as a large reservoir whereby vascular conductance can be decreased, the extent to which baroreflexes modulate CVC is unclear with some studies identifying large decreases in CVC, whereas other studies observe little to no changes in CVC (3, 5, 13, 15, 17, 19, 23, 29, 36, 37). The reasons for these divergent responses are not forthcoming, although Vissing et al. (36) proposed that convective skin cooling during LBNP may be a source of nonbaroreceptor-medicated cutaneous vasoconstriction. Additionally, inter- and intrasubject heterogeneity of cutaneous vasoconstrictor responses to baroreceptor unload likely contributes to these varied responses (19, 23).

Given the large potential for the cutaneous vasculature to assist in blood pressure regulation in the hyperthermic human, insufficient cutaneous vasoconstriction during pronounced baroreceptor unloading may be a primary mechanism by which heat stress impairs blood pressure regulation leading to heat syncope. However, little is known regarding the extent to which the cutaneous vasculature constricts leading up to and at the onset of syncopal symptoms in heat-stressed subjects. Understanding the effect of acute hypotension under such conditions on neural control of the cutaneous vasculature has important implications with respect to the mechanisms of compromised blood pressure control in the hemorrhagic individual who is also hyperthermic (e.g., military personnel, firefighters, etc.). Thus the primary objective of this investigation was to test the hypothesis that under heat-stressed conditions, the magnitude of cutaneous vasoconstriction leading up to and during syncopal symptoms is inadequate relative to the hypotensive challenge.

METHODS

Previously, obtained data were queried to identify subjects who experienced signs and symptoms of syncope while heat stressed during either LBNP or head-up tilt, requiring a termination of the test. Data were analyzed from 41 subjects who were exposed to heat stress LBNP and from 5 subjects who were exposed to heat stress 70° head-up tilt. Subject characteristics of age, height, and weight (means ± SD) were 34 ± 10 yr, 173 ± 11 cm, and 73 ± 15 kg, respectively, and all subjects were free of any known cardiovascular, neurological, or metabolic diseases. The phase of the menstrual cycle was not controlled for in the 19 female subjects. The heat stress was imposed by perfusing warm water (46–50°C) through a two-piece tube-lined suit worn by each subject. The suit covered the entire body surface with the exception of the head and face, hands and feet, and one forearm. The two-piece design permitted the LBNP chamber to be sealed directly to the subject's skin, thereby reducing convective skin cooling during LBNP (36). The criteria for test termination during the orthostatic challenges were the following: continued self-reporting by the subject of feeling faint, sustained nausea, rapid and progressive decrease in blood pressure resulting in sustained systolic blood pressure being <80 mmHg, and/or relative bradycardia accompanied with a narrowing of pulse pressure. Each study protocol from which these data were obtained received institutional approval from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas, and/or the University of Copenhagen. All subjects signed an approved informed consent form.

Subject instrumentation.

The following variables were obtained while subjects were normothermic, during whole body heating, and during LBNP or upright tilt while heat stressed: forearm skin blood flow was indexed via laser-Doppler flowmetry using integrating probes (Moor Instruments, Devon, UK; or Perimed, North Royalton, OH), heart rate was obtained via a cardiotachometer from the ECG signal, and arterial pressure was obtained either via direct cannulation of the brachial artery (Baxter Healthcare, Irvine, CA) or via a Finometer (FMS, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), while internal temperature was measured from pulmonary artery blood temperature, esophagus temperature (probe inserted to one fourth subject's height), sublingual sulcus temperature, or via an ingestible telemetric temperature pill located in the intestines (HQ, Palmetto, FL). Mean arterial pressure was obtained by integration of the arterial pressure waveform. Finometer-derived arterial pressure data were corrected to arterial pressure obtained from auscultation of the brachial artery (Suntech, Tango, Morrisville, NC). If multiple laser-Doppler flow probes were place on the forearm skin, data from those probes were averaged. In all cases, including upright tilting, the location of the laser-Doppler probes and pressure transducers remained at heart level. CVC was calculated from the ratio of the index of skin blood flow and mean arterial pressure × 100.

Data analysis.

Data were obtained via 16-bit analog-to-digital conversion (Biopac MP150, Santa Barbara, CA) with a minimal sampling frequency of 50 Hz. The aforementioned data were analyzed while subjects were normothermic, during heat stress just before the onset of LBNP or head-up tilt, and during the final 2 min of LBNP or head-up tilt preceding test termination due to the onset of syncopal symptoms. Data during the final 2 min of the orthostatic challenge were averaged into 5-s segments, whereas data during normothermia and heat stress but before LBNP/head-up tilt were averaged into segments of at least 1 min. The differences in responses (e.g., CVC, arterial pressure, and heart rate, etc.) between normothermia, heat stress before the orthostatic challenge, and at presyncope were analyzed via one-way repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by a pairwise multiple comparison procedure (Holm-Sidak) if a significant main effect was identified. The α-level of statistical significance was set at 0.05. Data are presented as means ± SD.

RESULTS

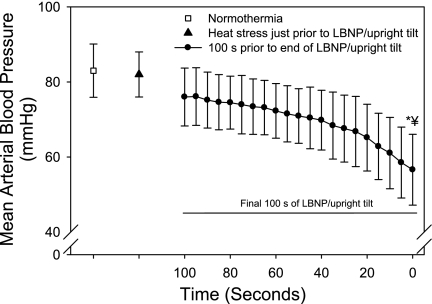

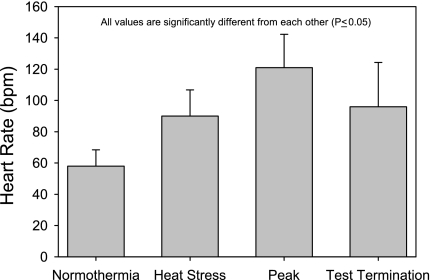

Whole body heat stress increased internal temperature 1.25 ± 0.3°C relative to when subjects were normothermic (range, 0.69 to 1.97°C; P < 0.001), resulting in an increased heart rate (58 ± 10 to 90 ± 16 beats/min; P < 0.001) without altering mean arterial pressure (83 ± 7 to 82 ± 6 mmHg). At the point of termination due to syncopal symptoms, mean arterial pressure was reduced to 57 ± 9 mmHg (Fig. 1). At this same time point, heart rate had decreased from a peak of 121 ± 21 beats/min during the orthostatic challenge to 96 ± 28 beats/min (P < 0.001; Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Mean arterial pressure at normothermia, heat stress, and the final 100 s before the end of the orthostatic challenge due to syncopal symptoms. Although data during the final 2 min of the orthostatic challenge were analyzed, 5 subjects experienced syncopal symptoms requiring test termination within a period of time between 100 and 120 s following the onset of the challenge. Thus only the final 100 s of data during the orthostatic challenge are presented to show average responses of all 46 subjects. Heat stress did not alter mean arterial pressure; however, blood pressure was reduced to 57 ± 9 mmHg at the termination of the orthostatic challenge. LBNP, lower body negative pressure. *Significantly different from normothermia; #significantly different from heat stress.

Fig. 2.

Heart rate at normothermia, heat stress, peak orthostatic challenge, and at test termination. Heat stress increased heart rate, while heart rate was further elevated during combined heat stress and LBNP/upright tilt. However, at test termination heart rate was reduced, indicative of a vagal response often accompanying a syncopal symptom limited orthostatic stress test. Peak represents the highest heart rate during combined heat and LBNP/upright tilt. Test termination represents heart rate immediately before ending LBNP or returning subject to the supine position due to syncopal symptoms. All values are significantly different from each other. bpm, Beats/min.

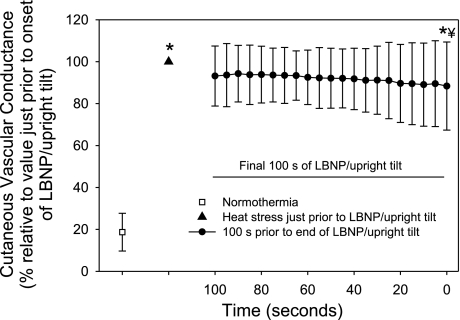

While normothermic, CVC was 29 ± 20 CVC units and increased approximately fivefold to 160 ± 58 CVC units (P < 0.001) during the heat stress but before the orthostatic challenge. At test termination due to syncopal symptoms, CVC decreased to 138 ± 61 CVC units relative to CVC just before the orthostatic challenge, representing a reduction of 15 ± 21% (Fig. 3). Importantly, CVC at the end of the orthostatic challenge was well above CVC when subjects were normothermic (P < 0.001). A visual analysis of CVC throughout the orthostatic challenge and a statistical analysis of CVC during the period just before ending the orthostatic challenge did not reveal evidence of paradoxical cutaneous vasodilation (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Cutaneous vascular conductance (CVC) at normothermia, heat stress, and the final 100 s before the end of the orthostatic challenge due to syncopal symptoms. Data are normalized relative to CVC just before the onset of the orthostatic challenge. Absolute CVC values are as follows: normothermia, 29 ± 20; heat stress, 160 ± 58; and end of orthostatic stress, 138 ± 61 CVC units. Heat stress increased CVC by ∼5-fold. LBNP/upright tilt caused relatively minor, but significant, reductions in CVC that persisted until the end of the orthostatic challenge, with CVC at test termination being 88 ± 21% of CVC before the orthostatic challenge. *Significantly different from normothermia; ¥significantly different from heat stress.

The magnitude by which LBNP or head-up tilt reduced CVC was not related to the increase in internal temperature (range of 0.65 to 1.97°C) when the cutaneous vascular response was expressed either as an absolute (r = 0.04; P = 0.77) or a relative change in CVC (r = 0.1; P = 0.52).

A subsequent analysis was performed to evaluate CVC responses in six subjects (1 female) who had a high tolerance to LBNP (final LBNP of at least 50 mmHg; average, 60 ± 9 mmHg) with seven subjects (4 females) who had a low tolerance to LBNP (final LBNP was not >20 mmHg). Immediately before LBNP, there were no differences between groups in the elevation in internal temperature (low tolerant, 1.3 ± 0.3°C; and high tolerant, 1.5 ± 0.1°C; P = 0.2), skin blood flow, CVC, or heart rate to the heat stress. At the highest common LBNP between groups (20 mmHg), the reduction in mean arterial pressure, and thus baroreceptor unloading stimulus, was greater in the low-tolerant group (−26 ± 8 mmHg) relative to the high-tolerant group (−2 ± 9 mmHg; P < 0.001). Consistent with this greater baroreceptor unloading stimulus, the decrease in CVC at 20 mmHg was also greater for the low-tolerant group (−18 ± 22 CVC units) relative to the high-tolerant group (+1 ± 13 CVC units; P = 0.05). However, at the point of test termination due to syncopal symptoms, when the reduction in arterial pressure and thus baroreceptor unloading status were similar between groups, regardless of LBNP, the magnitude of the reduction in CVC was not different (low tolerant, −18 ± 22 CVC units; and high tolerant, −12 ± 38 CVC units; P = 0.3).

DISCUSSION

The present findings are in agreement with most prior studies that report reductions in CVC in heat-stressed subjects during hypotensive gravitational stress but in the absence of syncopal symptoms (3, 5, 13, 17, 29). In the present study, leading up to and during syncopal symptoms, the magnitude of cutaneous vasoconstriction was quite small, with a CVC reduction of only 15 ± 21% relative to peak cutaneous vasodilation just before the orthostatic challenge. Finally, there was no evidence of paradoxical cutaneous vasodilation associated with the onset of syncopal symptoms, unlike what is often identified in the limbs (likely muscle) of normothermic subjects (7, 11). Given that an upward to 50% of cardiac output can be directed toward the skin in heat-stressed subjects (25, 27), coupled with the relatively small reduction in CVC leading up to and during presyncope, suggests that an inadequate cutaneous vasoconstriction may be a primary mechanism by which heat stress compromises the control of blood pressure during a hypotensive stimulus.

The present approach is in contrast to prior experimental designs in which the assessment of cutaneous vascular responses associated with syncopal symptoms was not the objective of the investigation (2–4, 12, 13, 17, 20, 29, 35). That said, one study reported data from three individuals who experienced syncopal symptoms during LBNP while heat stressed (13). In these individuals venous occlusion plethysmography measures of forearm vascular conductance (inclusive of muscle and skin vascular beds), at the point of presyncope, remained well above pre-heat stress vascular conductance. This observation is consistent with the present findings, although the magnitude of the reduction in forearm vascular conductance in the cited study was greater than that observed in the skin of the present study.

The extent of the reduction in CVC during syncopal symptoms is comparable with CVC responses during moderate LBNP in heat-stressed subjects not experiencing syncopal symptoms (3, 17, 19). For example, in the present study CVC decreased ∼15%, whereas Crandall et al. (3) reported ∼17% reduction in CVC to 30 mmHg LBNP (3) and Kellogg et al. (17) reported a 23% reduction in CVC during 40 mmHg LBNP in heat-stressed subjects. Nevertheless, reductions in CVC during orthostatic stress in heat-stressed subjects are not consistently observed (19, 23). In the present study, despite an overall significant reduction in CVC to LBNP or head-up tilt, CVC in six subjects increased 5% or more at the end of LBNP (data not shown), indicating there is some heterogeneity in this response.

Prior studies report reductions in muscle sympathetic nerve activity along with parallel increases in limb vascular conductance leading up to and at the point of vasovagal presyncope/syncope (7, 11). Typically, these responses occur near the final minute or two before the onset of syncopal symptoms (11). However, it was unknown whether paradoxical cutaneous vasodilation contributed to the rapid reduction in blood pressure leading up to syncopal symptoms in the heat-stressed subjects. To evaluate this question, CVC responses were analyzed at 5-s increments during the 2-min period preceding the cessation of the orthostatic challenge. Counter to the proposed hypothesis, and unlike that observed in the whole limb of normothermic subjects (7, 11), the evidence does not support a generalized increase in CVC leading up to and during syncopal symptoms (Fig. 3).

Orthostatic stress decreases cardiac output in both normothermic and heat stress conditions. If, for example, cardiac output increased from 6 to 10 l/min because of a heat stress, which is a typical increase in cardiac output for the present level of heating (22, 39), and then was reduced during an orthostatic stress back to 6 l/min, despite cardiac output being “normal” relative to when the subject was normothermic (i.e., at 6 l/min), to maintain blood pressure, the systemic vascular conductance would need to decrease by 40% to appropriately respond to the orthostatic challenge. However, because the renal, splanchnic, and perhaps muscle vascular beds are already in a vasoconstricted state due to the heat stress before the orthostatic challenge (21, 25–28), there is a limited reserve by which these beds can further vasoconstrict to accommodate this needed reduction in systemic vascular conductance. Thus, to accommodate a 40% reduction in cardiac output in the heat-stressed human during an orthostatic challenge, whole body CVC would need to decrease ∼30–40% (depending on the vasoconstrictor reserve of the splanchnic, renal, and muscle vascular beds) to maintain blood pressure. Given the relatively small reduction in CVC leading up to and at the onset of syncopal symptoms, the present data suggest that inadequate cutaneous vasoconstriction and/or inadequate reductions in cutaneous active vasodilation are primary mechanisms by which heat stress impairs blood pressure control during an orthostatic challenge.

What is the mechanism(s) resulting in inadequate reductions in CVC during the imposed orthostatic challenges? With one exception (8), we and others have not observed changes in skin sympathetic nerve activity during brief or sustained reductions in blood pressure in heat stressed individuals (5, 6, 36, 40, 42). Consistent with this observation, electrical stimulation of the carotid sinus nerve (innervating the carotid baroreceptors) in normothermic subjects did not change skin sympathetic nerve activity, despite appropriate decreases in muscle sympathetic nerve activity (38). Thus one possibility for relatively minor cutaneous vasoconstriction during baroreceptor unloading may be an inadequate neural response to the skin relative to the hypotensive perturbation. However, one has to be cognizant that the multiunit skin sympathetic recordings likely contain neural signals leading to cutaneous vasoconstriction, sweating, and perhaps cutaneous active vasodilation, and thus it may be that one is unable to distinguish changes in the particular component of the integrated skin sympathetic nerve recording responsible for the slight reductions in CVC.

Substances associated with active cutaneous vasodilation may attenuate the responsiveness of the cutaneous vasoconstrictor system, analogous to functional sympatholysis observed in the exercising muscle (24, 30). In support of this possibility, we showed attenuated cutaneous vasoconstrictor responsiveness to exogenous norepinephrine when subjects were moderately heat stressed, relative to when they were normothermic (41). Consistent with that observation, when the cutaneous active vasodilator limb was blocked via intradermal botulinum toxin administration, the reduction in CVC to LBNP and whole body cooling were significantly greater relative to unblocked sites (32, 33). Further studies suggest that nitric oxide, which is purported to be involved in cutaneous active vasodilation (16, 31), may be one of the factors that attenuate cutaneous vasoconstriction (9, 10, 33, 34). Finally, minimal cutaneous vasoconstriction leading up to and during syncopal symptoms in heat-stressed subjects may be due to an interaction, or perhaps competition, between cutaneous vasodilation for heat dissipation and cutaneous vasoconstriction for blood pressure control, with the former taking precedent over the latter. These, and perhaps other mechanisms, may be responsible for a relatively small reduction in CVC during profound hypotension.

Potential limitations to the interpretation of the findings.

The purpose of the study was to evaluate CVC responses leading up to and during syncopal symptoms, and thus only subjects who experienced syncopal symptoms during the gravitational stress were included in the analysis. This study design may be viewed as being biased toward intolerant subjects, despite that every individual will experience syncopal symptoms if a sufficient gravitational challenge is imposed. To address the possibility that differences in individual tolerance may affect these data, the magnitude of the reduction in CVC between seven low-tolerant subjects (unable to complete more than 20 mmHg during a ramped LBNP while heat stressed) were compared with six high-tolerant subjects (able to asymptomatically withstand 50+ mmHg LBNP while heat stressed). At 20 mmHg LBNP, the reduction in arterial pressure and CVC was greater for the low-tolerant group compared with the high-tolerant group. However, at test termination because of the onset of syncopal symptoms, regardless of the level of LBNP, there were no differences in the magnitude of the reduction in arterial pressure or CVC between low- and high-tolerant groups. Similar reductions in CVC at the onset of syncopal symptoms between groups, regardless of LBNP, suggest that the mechanism by which the high-tolerant group was better able to withstand greater LBNPs was unlikely due to greater cutaneous vasoconstriction; thus other mechanisms are likely responsible for these individuals' ability to withstand this hypotensive challenge. Nevertheless, these observations do not discount the hypothesis that should the skin constrict to a greater extent during a hypotensive challenge while heat stressed, that the capacity to withstand that hypotensive challenge would be improved.

With the level of heating used in the present study, mean skin temperature under the water-perfused suit is typically ∼38°C. This is in contrast to skin temperature at the uncovered sites where skin blood flow was evaluated. It is possible that cutaneous vascular responses to the hypotensive challenges may be different between skin covered by the water-perfused suit relative to uncovered skin. However, given that local heating impairs cutaneous vasoconstriction (41), perhaps through a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism (34, 45), the magnitude of cutaneous vasoconstriction would be even more attenuated under the water-perfused suit relative to at the exposed forearm where skin blood flow measurements were made.

Because these data were obtained from differing protocols (i.e., LBNP and head-up tilt), with the starting LBNP and duration of each LBNP stage not controlled, the value of reporting the average LBNP associated with syncopal symptoms, which was 34 ± 8 mmHg, is questionable. However, this does not adversely affect the interpretation of the data, given that the purpose of the study was to evaluate the reduction in CVC leading up to and during syncopal symptoms, regardless of the mode of the syncopal stimulus.

In conclusion, the present data demonstrate minimal cutaneous vasoconstriction during pronounced baroreceptor unloading in the heat-stressed human. Given the importance of the control of CVC for blood pressure regulation during heat stress, inadequate cutaneous vasoconstriction to a hypotensive challenge likely contributes to heat-induced orthostatic intolerance. These findings may be beneficial toward the medical treatment of hemorrhagic individuals who are also heat stressed, as can occur in military combat or industrial accidents. Based on the present observations, it is expected that treatment to stabilize blood pressure will be more challenging relative to if the injury occurred while the individual was normothermic or in a cooled state.

GRANTS

This research project was funded in part by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-61388, HL-84072, and GM-68865.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the following individuals who assisted in data collection over a number of years that resulted in the acquisition of the presented data: Drs. Jian Cui, Sylvain Durand, Scott Davis, David Keller, David Low, Jonathan Wingo, M. Robert Brothers, and Niels Secher.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allan JR, Crossley RJ. Effect of controlled elevation of body temperature on human tolerance to +G z acceleration. J Appl Physiol 33: 418–420, 1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beiser GD, Zelis R, Epstein SE, Mason DT, Braunwald E. The role of skin and muscle resistance vessels in reflexes mediated by the baroreceptor system. J Clin Invest 49: 225–231, 1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crandall CG, Johnson JM, Kosiba WA, Kellogg DL., Jr Baroreceptor control of the cutaneous active vasodilator system. J Appl Physiol 81: 2192–2198, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crossley RJ, Greenfield AD, Plassaras GC, Stephens D. The interrelation of thermoregulatory and baroreceptor reflexes in the control of blood vessels in the human forearm. J Physiol 183: 628–636, 1966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cui J, Wilson TE, Crandall CG. Orthostatic challenge does not alter skin sympathetic nerve activity in heat-stressed humans. Auton Neurosci 116: 54–61, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delius W, Hagbarth KE, Hongell A, Wallin BG. Manoeuvres affecting sympathetic outflow in human skin nerves. Acta Physiol Scand 84: 177–186, 1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dietz NM, Halliwill JR, Spielmann JM, Lawler LA, Papouchado BG, Eickhoff TJ, Joyner MJ. Sympathetic withdrawal and forearm vasodilation during vasovagal syncope in humans. J Appl Physiol 82: 1785–1793, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dodt C, Gunnarsson T, Elam M, Karlsson T, Wallin BG. Central blood volume influences sympathetic sudomotor nerve traffic in warm humans. Acta Physiol Scand 155: 41–51, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durand S, Davis SL, Cui J, Crandall CG. Exogenous nitric oxide inhibits sympathetically mediated vasoconstriction in human skin. J Physiol 562: 629–634, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hodges GJ, Kosiba WA, Zhao K, Alvarez GE, Johnson JM. The role of baseline in the cutaneous vasoconstrictor responses during combined local and whole body cooling in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H3187–H3192, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jardine DL, Ikram H, Frampton CM, Frethey R, Bennett SI, Crozier IG. Autonomic control of vasovagal syncope. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 274: H2110–H2115, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson JM, Brengelmann GL, Rowell LB. Interactions between local and reflex influences on human forearm skin blood flow. J Appl Physiol 41: 826–831, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson JM, Niederberger M, Rowell LB, Eisman MM, Brengelmann GL. Competition between cutaneous vasodilator and vasoconstrictor reflexes in man. J Appl Physiol 35: 798–803, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keller D, Low DA, Wingto J, Brothers RM, Hastings J, Davis SL, Crandall CG. Acute volume expansion preserves orthostatic tolerance during whole-body heat stress in humans. J Physiol 587: 1131–1139, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keller DM, Davis SL, Low DA, Shibasaki M, Raven PB, Crandall CG. Carotid baroreceptor stimulation alters cutaneous vascular conductance during whole-body heating in humans. J Physiol 577: 925–933, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kellogg DL, Jr, Crandall CG, Liu Y, Charkoudian N, Johnson JM. Nitric oxide and cutaneous active vasodilation during heat stress in humans. J Appl Physiol 85: 824–829, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kellogg DL, Jr, Johnson JM, Kosiba WA. Baroreflex control of the cutaneous active vasodilator system in humans. Circ Res 66: 1420–1426, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lind AR, Leithead CS, McNicol GW. Cardiovascular changes during syncope induced by tilting men in the heat. J Appl Physiol 25: 268–276, 1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mack GW. Assessment of cutaneous blood flow by using topographical perfusion mapping techniques. J Appl Physiol 85: 353–359, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mack G, Nishiyasu T, Shi X. Baroreceptor modulation of cutaneous vasodilator and sudomotor responses to thermal stress in humans. J Physiol 483: 537–547, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minson CT, Wladkowski SL, Pawelczyk JA, Kenney WL. Age, splanchnic vasoconstriction, and heat stress during tilting. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 276: R203–R212, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson MD, Haykowsky MJ, Petersen SR, Delorey DS, Cheng-Baron J, Thompson RB. Increased left ventricular twist, untwisting rates, and suction maintain global diastolic function during passive heat stress in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H930–H937, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peters JK, Nishiyasu T, Mack GW. Reflex control of the cutaneous circulation during passive body core heating in humans. J Appl Physiol 88: 1756–1764, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Remensnyder JP, Mitchell JH, Sarnoff SJ. Functional sympatholysis during muscular activity. Observations on influence of carotid sinus on oxygen uptake. Circ Res 11: 370–380, 1962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rowell LB. Thermal stress. In: Human Circulation Regulation During Physical Stress. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986, p. 174–212 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rowell LB, Brengelmann GL, Blackmon JR, Murray JA. Redistribution of blood flow during sustained high skin temperature in resting man. J Appl Physiol 28: 415–420, 1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rowell LB, Brengelmann GL, Murray JA. Cardiovascular responses to sustained high skin temperature in resting man. J Appl Physiol 27: 673–680, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rowell LB, Detry JR, Profant GR, Wyss C. Spanchnic vasoconstriction in hyperthermic man—role of falling blood pressure. J Appl Physiol 31: 864–869, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rowell LB, Wyss CR, Brengelmann GL. Sustained human skin and muscle vasoconstriction with reduced baroreceptor activity. J Appl Physiol 34: 639–643, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saltin B, Radegran G, Koskolou MD, Roach RC. Skeletal muscle blood flow in humans and its regulation during exercise. Acta Physiol Scand 162: 421–436, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shastry S, Minson CT, Wilson SA, Dietz NM, Joyner MJ. Effects of atropine and l-NAME on cutaneous blood flow during body heating in humans. J Appl Physiol 88: 467–472, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shibasaki M, Davis SL, Cui J, Low DA, Keller DM, Durand S, Crandall CG. Neurally mediated vasoconstriction is capable of decreasing skin blood flow during orthostasis in the heat-stressed human. J Physiol 575: 953–959, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shibasaki M, Durand S, Davis SL, Cui J, Low DA, Keller DM, Crandall CG. Endogenous nitric oxide attenuates neutrally mediated cutaneous vasoconstriction. J Physiol 585: 627–634, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shibasaki M, Low DA, Davis SL, Crandall CG. Nitric oxide inhibits cutaneous vasoconstriction to exogenous norepinephrine. J Appl Physiol 105: 1504–1508, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tripathi A, Nadel ER. Forearm skin and muscle vasoconstriction during lower body negative pressure. J Appl Physiol 60: 1535–1541, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vissing SF, Scherrer U, Victor RG. Increase of sympathetic discharge to skeletal muscle but not to skin during mild lower body negative pressure in humans. J Physiol 481: 233–241, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vissing SF, Secher NH, Victor RG. Mechanisms of cutaneous vasoconstriction during upright posture. Acta Physiol Scand 159: 131–138, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wallin BG, Sundlof G, Delius W. The effect of carotid sinus nerve stimulation on muscle and skin nerve sympathetic activity in man. Pflügers Arch 358: 101–110, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson TE, Brothers RM, Tollund C, Dawson EA, Nissen P, Yoshiga CC, Jons C, Secher NH, Crandall CG. Effect of thermal stress on Frank-Starling relations in humans. J Physiol 587: 3383–3392, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilson TE, Cui J, Crandall CG. Absence of arterial baroreflex modulation of skin sympathetic activity and sweat rate during whole-body heating in humans. J Physiol 536: 615–623, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson TE, Cui J, Crandall CG. Effect of whole-body and local heating on cutaneous vasoconstrictor responses in humans. Auton Neurosci 97: 122–128, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson TE, Cui J, Crandall CG. Mean body temperature does not modulate eccrine sweat rate during upright tilt. J Appl Physiol 98: 1207–1212, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson TE, Cui J, Zhang R, Crandall CG. Heat stress reduces cerebral blood velocity and markedly impairs orthostatic tolerance in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291: R1443–R1448, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson TE, Cui J, Zhang R, Witkowski S, Crandall CG. Skin cooling maintains cerebral blood flow velocity and orthostatic tolerance during tilting in heated humans. J Appl Physiol 93: 85–91, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wingo JE, Low DA, Keller DM, Brothers RM, Shibasaki M, Crandall CG. Effect of elevated local temperature on cutaneous vasoconstrictor responsiveness in humans. J Appl Physiol 106: 571–575, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]