Abstract

Resveratrol is a natural phytophenol that exhibits cardioprotective effects. This study was designed to elucidate the mechanisms by which resveratrol protects against diabetes-induced cardiac dysfunction. Normal control (m-Leprdb) mice and type 2 diabetic (Leprdb) mice were treated with resveratrol orally for 4 wk. In vivo MRI showed that resveratrol improved cardiac function by increasing the left ventricular diastolic peak filling rate in Leprdb mice. This protective role is partially explained by resveratrol's effects in improving nitric oxide (NO) production and inhibiting oxidative/nitrative stress in cardiac tissue. Resveratrol increased NO production by enhancing endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) expression and reduced O2·− production by inhibiting NAD(P)H oxidase activity and gp91phox mRNA and protein expression. The increased nitrotyrosine (N-Tyr) protein expression in Leprdb mice was prevented by the inducible NO synthase (iNOS) inhibitor 1400W. Resveratrol reduced both N-Tyr and iNOS expression in Leprdb mice. Furthermore, TNF-α mRNA and protein expression, as well as NF-κB activation, were reduced in resveratrol-treated Leprdb mice. Both Leprdb mice null for TNF-α (dbTNF−/dbTNF− mice) and Leprdb mice treated with the NF-κB inhibitor MG-132 showed decreased NAD(P)H oxidase activity and iNOS expression as well as elevated eNOS expression, whereas m-Leprdb mice treated with TNF-α showed the opposite effects. Thus, resveratrol protects against cardiac dysfunction by inhibiting oxidative/nitrative stress and improving NO availability. This improvement is due to the role of resveratrol in inhibiting TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation, therefore subsequently inhibiting the expression and activation of NAD(P)H oxidase and iNOS as well as increasing eNOS expression in type 2 diabetes.

Keywords: cardiac diabetic complication, antioxidants and free radicals, anti-inflammation, nitric oxide, magnetic resonance spectroscopy

diabetes is associated with an excessive cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Diabetes is an independent risk factor for left ventricular (LV) dysfunction (17). Although one frequently associates cardiac dysfunction with enhanced coronary atherosclerosis in diabetic patients, evidence has accumulated for the existence of a specific “diabetic” cardiomyopathy, which has been shown even in the absence of hypertension and atherosclerosis in diabetic patients (47). The relative pathogenic significance of multiple factors that may alter myocardial performance in diabetic patients awaits further delineation (22). Furthermore, such delineation will aid in the discovery of effective therapies for diabetes-induced myocardial dysfunction.

Epidemiological studies (8, 18) have indicated that the Mediterranean diet is associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease. Resveratrol is an important dietary constituent in the Mediterranean diet (37). Previous studies have revealed that resveratrol exerts cardioprotective effects in fructose-fed rat (21) and rats with streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetes (41). However, the effects and mechanisms by which resveratrol protects against cardiac dysfunction in type 2 diabetes await elucidation.

MRI is a noninvasive technique that can assess both the systolic and diastolic function of the heart in vivo. Using this method, we aimed to assess cardiac function in control m-Leprdb and diabetic Leprdb mice treated with either resveratrol or vehicle. We hypothesized that resveratrol rescues cardiac dysfunction in type 2 diabetes by attenuating oxidative/nitrative stress as well as improving nitric oxide (NO) availability. To test this, we examined the effects of resveratrol on the production of NO, ROS, and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) in the cardiac tissue of Leprdb mice. We also investigated the effects of resveratrol on TNF-α-mediated NF-κB activation and the downstream signaling that contributes to the oxidative/nitrative stress and impaired NO availability to elucidate the mechanisms of resveratrol's cardioprotective effects in type 2 diabetes.

METHODS

Animals and Treatments

Experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Missouri-Columbia and conform to the current guidelines of the National Institutes of Health and the American Physiological Society for the care and use of laboratory animals. Heterozygote control (m-Leprdb) mice (background strain: C57BLKS/J), homozygous type 2 diabetic (Leprdb) mice (background strain: C57BLKS/J), and Leprdb mice null for TNF-α (dbTNF−/dbTNF−; background strain: C57BL/6J) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory and maintained on a normal rodent chow diet. Male m-Leprdb mice (weight: 20–35 g) as well as Leprdb (weight: 40–60 g) and dbTNF−/dbTNF− (weight: 40–60 g) mice of either sex were used in this study. These dbTNF−/dbTNF− mice show the phenotypes of hyperglycemia and obesity, the diabetic phenotype that is consistent with the penetrance of the leptin receptor (Lepr) mutation. Resveratrol (Cayman Chemical) was dispersed in 0.5% methylcellulose (Sigma) (9). At the age of 12 wk, male m-Leprdb and Leprdb mice were treated with either resveratrol (20 mg·kg−1·day−1) or methylcellulose vehicle for 4 wk by gastric gavages (34, 49).

In Vivo Cine MRI

Noninvasive MRI scans were performed on age-matched m-Leprdb and Leprdb mice with or without 4 wk of resveratrol treatment using a Varian 7-T horizontal-bore MRI (Varian, Palo Alto, CA) instrument equipped with a 38- and 60-mm quadrature-driven birdcage radiofrequency coil. ECG and respiratory monitoring and gating were done with a small animal monitoring system (SA Instruments, Stony Brook, NY). Warm air was circulated through the MRI bore to maintain the animal's body temperature. Induction of anesthesia was accomplished with 4% isoflurane and 1 l/min oxygen. The respiratory rate was monitored and used to manually calibrate the maintenance dose of isoflurane at 1.2–1.8%. Imaging protocols were similar to previously published procedures (42). Briefly, ECG/respiratory gated gradient echo sequences were acquired with 1-mm slice thickness and a 30 × 30-mm2 field of view for both long- and short-axis images. Wall thickness measurements were determined with Image J (NIH, Bethesda, MD) on the midventricular axial image immediately after the R wave and with averaging of 3 measurements/mouse. Ventricular length was determined on long-axis coronal images. LV mass (LVM) was derived from the sum of the differences between the epicardial and endocardial areas at the end of the diastolic phase from the apex to the base multiplied by slice thickness (1 mm) and the density of the myocardium (1.053 g/ml) (31). LV end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) and LV end-systolic volume (LVESV) were calculated as the sum of the endocardial areas of each slice from the apex to the mitral annulus plane at end diastole and end systole, respectively. LV ejection fraction (EF) was calculated as follows: LV EF = (LVEDV − LVESV)/LVEDV. Stroke volume (SV) was calculated as follows: SV = LVEDV − LVESV, and cardiac output (CO) was calculated as follows: CO = SV × HR, where HR is heart rate (44, 46). LV volume-time curves were plotted as LV volumes versus time in one cardiac cycle. The systolic peak ejection rate (PER) and diastolic peak filling rate (PFR) were defined as the maximal absolute value of the minimum and maximum derivatives of the LV volume-time curve, respectively. Image analysis was performed using VNMRJ (Varian), Image J (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/), and Segment (http://segment.heiberg.se) (15) software tools.

mRNA Expression of TNF-α and NAD(P)H Oxidase Subunit gp91phox by Real-Time PCR

We used quantitative real-time RT-PCR techniques to analyze the mRNA expression of TNF-α and gp91phox in murine LV cardiac tissue as previously reported (45, 48). Data were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method (where CT is threshold cycle) and are presented as fold changes of transcripts in Leprdb mice normalized to an internal control (β-actin) compared with m-Leprdb mice (defined as 1.0-fold).

Protein Expression of TNF-α, IκB-α, Phospho-IκB-α, NF-κB, gp91phox, endothelial NO synthase, inducible NO synthase, and Nitrotyrosine by Western Blot Analyses

Protein expressions were detected using TNF-α, IκB-α, and phospho-IκB-α primary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), NF-κB, inducible NO synthase (iNOS), and nitrotyrosine (N-Tyr) primary antibodies (Abcam), and endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) and gp91phox primary antibodies (BD Science Pharmingen). Signals were scanned densitometrically using Fuji LAS3000 and quantified with Multigauge software (Fujifilm). The relative amounts of protein expression were quantified to those of the corresponding m-Leprdb control, which were set to a value of 1.0.

NAD(P)H Oxidase Activity

NAD(P)H oxidase activity was assayed in homogenized heart tissue extracts using a lucigenin (Sigma)-derived chemiluminescence assay as previous described (11, 49). Samples were read by Fluoroscan Ascent FL (Thermal Scientific), and NAD(P)H oxidase activity was normalized to the m-Leprdb control.

Immunofluorescence Staining

Immunohistochemistry was used to identify and localize gp91phox proteins in sections of vessels or myocardial tissue. Formalin-fixed hearts were sectioned at 5 μm. Primary antibodies to gp91phox (BD Biosciences Pharmingen), the endothelial cell marker von Willebrand factor (Abcam), the smooth muscle marker α-actin (Abcam), or the macrophage marker F4/80 (Serotec) were used for sequential double-immunofluorescence staining. Secondary fluorescent antibodies were either FITC or Texas red conjugated. Sections were mounted in an anti-fading agent (Slowfade gold with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, Invitrogen). Slides were observed and analyzed using a fluorescence microscope with a ×40 objective (Zeiss Axioplan Microscope).

Measurement of O2·− Using Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Spectroscopy

O2·− quantification from the electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra was determined in the heart tissue homogenate as previously described (48). In brief, a 10% tissue homogenate was prepared in 50 mmmol/l phosphate buffer containing 0.01 mmol/l EDTA. The supernatants containing 2 mmol/l 1-hydroxy-3-carboxypyrrolidine were incubated for 30 min at 37°C and quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen. Superoxide quantification from the EPR spectra was determined by double integration of the peaks, with reference to a standard curve generated from horseradish peroxidase generation of the anion from standard solutions of hydrogen peroxide, using p-acetamidophenol as the cosubstrate, and then normalized by protein concentration.

Measurement of Nitrite/Nitrate

Nitrite/nitrate levels in cardiac tissue were assessed using amerometric sensors (World Precision Instruments) as reported by Zhang et al. (49). Briefly, nitrate was converted to nitrite using Nitralyzer (World Precision Instruments). The currents (in pA) detected by the 2-mm sensor (ISO-NOP) represent the concentration of nitrite in the lysis of LV cardiac tissue.

Data Analysis

Results are reported as means ± SD except as specifically stated. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by a least-significant-difference post hoc test. Significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Effects of Resveratrol on Diabetes-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction

Morpholometric parameters.

LVM was lower in Leprdb mice, although there was no statistical difference. However, the LVM-to-body mass ratio was significantly lower in Leprdb mice. Resveratrol had no effect on LVM and the LVM-to-body mass ratio (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cardiac function parameters and morphological parameters

| m-Leprdb Mice | Leprdb Mice | Leprdb Mice + RSV | m-Leprdb Mice + RSV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV mass, mg | 89.91 ± 16.76 | 77.49 ± 9.25 | 88.92 ± 22.68 | 91.09 ± 15.85 |

| Body mass, g | 28.94 ± 1.55 | 49.79 ± 4.39* | 48.74 ± 4.50* | 33.93 ± 2.37† |

| LV mass-to-body mass ratio, mg/g | 3.11 ± 0.63 | 1.56 ± 0.11* | 1.81 ± 0.28* | 2.70 ± 0.52† |

| Respiratory rate, breaths/min | 31.50 ± 4.43 | 40.20 ± 8.49 | 38.75 ± 1.26 | 38.00 ± 4.97 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 381.89 ± 47.31 | 315.66 ± 14.27* | 322.48 ± 26.30* | 370.37 ± 25.49† |

| LV end-diastolic volume, μl | 49.10 ± 7.78 | 42.68 ± 7.75 | 49.26 ± 12.02 | 51.15 ± 8.38 |

| LV end-systolic volume, μl | 16.10 ± 5.15 | 11.90 ± 5.03 | 15.18 ± 7.68 | 15.28 ± 4.67 |

| Stroke volume, μl | 33.00 ± 2.98 | 30.77 ± 3.91 | 34.08 ± 5.23 | 35.88 ± 3.80 |

| Cardiac output, ml/min | 12.69 ± 2.55 | 9.76 ± 1.59* | 11.01 ± 1.95 | 13.30 ± 1.77† |

| Ejection fraction, % | 67.84 ± 5.60 | 72.90 ± 6.96 | 70.35 ± 8.37 | 70.60 ± 3.95 |

| Peak ejection rate, μl/ms | 0.71 ± 0.14 | 0.49 ± 0.10* | 0.56 ± 0.09 | 0.67 ± 0.07† |

| Peak filling rate, μl/ms | 0.75 ± 0.06 | 0.50 ± 0.09* | 0.71 ± 0.18† | 0.77 ± 0.13† |

Data are means ± SD; n = 4–7 mice/group. RSV, resveratrol; LV, left ventricular.

P < 0.05 vs. m-Leprdb mice;

P < 0.05 vs. Leprdb mice.

HR and respiratory rate.

Leprdb mice had lower HRs compared with m-Leprdb mice, although the respiratory rate was similar among groups. Resveratrol did not affect HR or respiratory rate in both Leprdb and m-Leprdb mice (Table 1).

Systolic function parameters.

LVEDV, LVESV, and SV were marginally decreased in Leprdb mice. CO was significantly diminished in Leprdb versus m-Leprdb mice. Resveratrol slightly increased LVEDV, LVESV, SV, and CO, although there were no statistical differences (Table 1). EF was comparable among all groups (Table 1).

LV volume-time curves and diastolic relaxation.

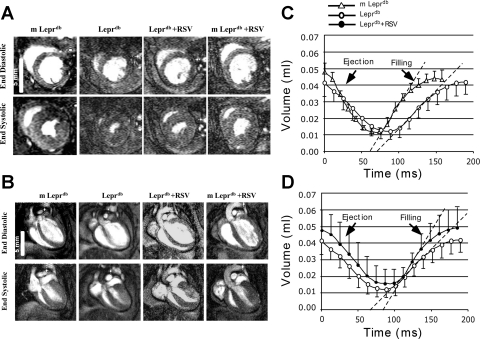

LV volume-time curves indicated that PER and PFR were reduced in Leprdb mice. Resveratrol greatly increased PFR without significantly affecting PER (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Resveratrol (RSV) alleviated cardiac dysfunction in Leprdb mice. A and B: representative MRI images at end diastole and end systole in a midventricular short-axis slice (A) and ventricular long-axis (B) acquired in m-Leprdb and Leprdb mice treated with either RSV (20 mg·kg−1·day−1, 4 wk, oral gavage) or vehicle. Note the lower left ventricular (LV) cavity area and shorter LV length in diabetic mice. C and D: summary data of LV volume-time curves, in which LV volumes are plotted against time within the cardiac cycle. Peak ejection rate (PER) and peak filling rate (PFR) were defined as the maximal absolute value of the minimum and maximum derivatives of the LV volume-time curve. C: PFR was higher in m-Leprdb versus Leprdb mice. D: RSV increased PFR in Leprdb mice without affecting PER.

Resveratrol Attenuated Protein and mRNA Expression of TNF-α and Protein Expression of Phospho-IκB-α and NF-κB p65 in Type 2 Diabetes

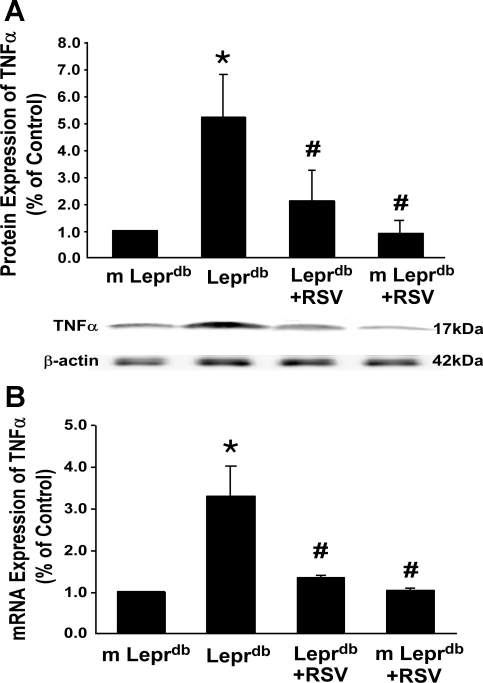

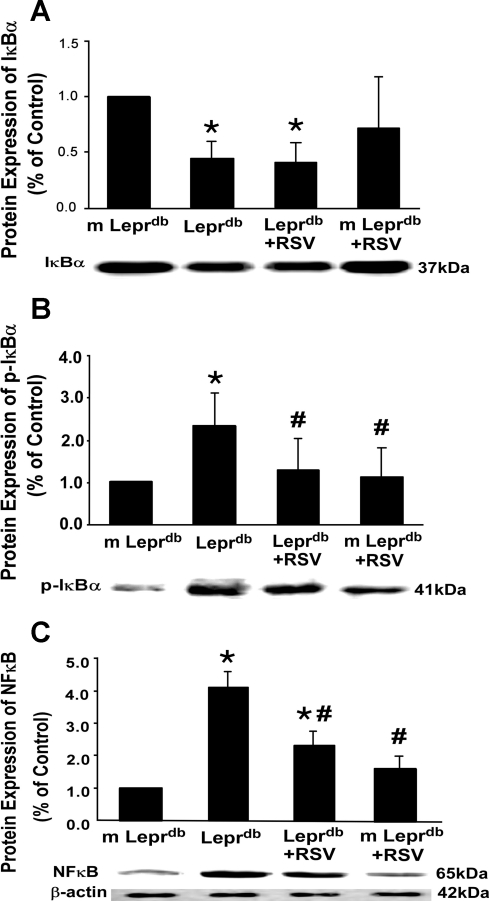

Protein and mRNA expression of TNF-α (Fig. 2) in Leprdb mice were significantly elevated compared with m-Leprdb mice. Resveratrol attenuated TNF-α expression in Leprdb mice. IκB-α expression was decreased in Leprdb mice, whereas IκB-α phosphorylation and NF-κB p65 expression were increased in Leprdb mice. Resveratrol attenuated IκB-α phosphorylation and NF-κB p65 protein expression without affecting total IκB-α expression (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

RSV decreased protein and mRNA expression of TNF-α in Leprdb mice. A and B: protein (A) and mRNA (B) expression of TNF-α were significantly higher in Leprdb mice than in m-Leprdb mice. The administration of RSV reduced TNF-α expression (protein and mRNA) in Leprdb mice. Data are means ± SD; n = 5 separate experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. m-Leprdb mice; #P < 0.05 vs. Leprdb mice.

Fig. 3.

RSV inhibited phospho-IκB-α and NF-κB p65 protein expression. A and B: total IκB-α expression was decreased in Leprdb mice (A), whereas phosphorylated (p-)IκB-α was greatly elevated (B). RSV inhibited IκB-α phosphorylation without affecting total IκB-α expression. C: NF-κB p65 protein expression in Leprdb mice was significantly increased. RSV decreased NF-κB protein expression. Data are means ± SD; n = 4 separate experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. m-Leprdb mice; #P < 0.05 vs. Leprdb mice.

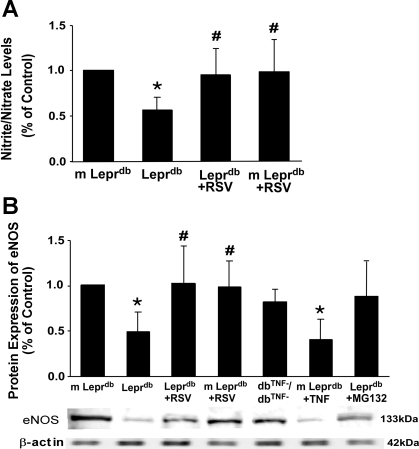

Resveratrol Increased eNOS Expression and Nitrite/Nitrate Levels in Type 2 Diabetic Mice

Cardiac nitrite/nitrate levels were reduced in diabetic mice, and resveratrol enhanced NO production (Fig. 4A). eNOS protein expression was downregulated in diabetic mice. Resveratrol increased eNOS expression (Fig. 4B). Protein expression of eNOS was greater in dbTNF−/dbTNF− and Leprdb mice treated with the NF-κB inhibitor MG-132 (10 mg·kg−1·day−1 ip, 5 days) compared with Leprdb mice, whereas m-Leprdb mice treated with TNF-α (10 μg·kg−1·day−1 ip, 3 days, R&D) showed reduced eNOS expression (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

RSV promoted nitric oxide (NO) production by increasing eNOS expression. A: nitrite/nitrate levels were markedly reduced in Leprdb mice, which were completely reversed by RSV treatment. Data are means ± SD; n = 5 mice. *P < 0.05 vs. m-Leprdb mice; #P < 0.05 vs. Leprdb mice. B: endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) expression was decreased in Leprdb mice, and RSV enhanced eNOS expression. Furthermore, protein expression of eNOS was greater in dbTNF−/dbTNF− and Leprdb mice treated with the NF-κB inhibitor MG-132 (10 mg·kg−1·day−1 ip, 5 days) than in Leprdb mice, whereas m-Leprdb mice treated with TNF-α (10 μg·kg−1·day−1 ip, 3 days, R&D) showed downregulated eNOS expression. Data are means ± SD; n = 4 separate experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. m-Leprdb mice; #P < 0.05 vs. Leprdb mice.

Resveratrol Inhibited Increased NAD(P)H Oxidase Activity and Subsequent O2·− Production in Type 2 Diabetes

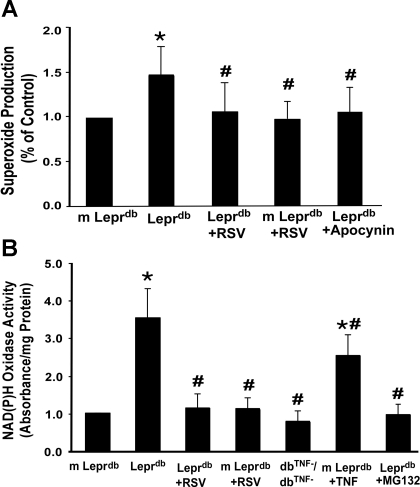

Figure 5A shows that O2·− production was significantly increased in Leprdb mice Resveratrol reduced O2·− production in Leprdb mice but not in m-Leprdb mice. The NAD(P)H oxidase inhibitor apocynin (20 mg·kg−1·day−1 ip, 3 days) attenuated O2·− production in Leprdb mice to levels not significantly different from normal control mice. NAD(P)H oxidase activity was higher in Leprdb mice than in m-Leprdb mice (Fig. 5B). Resveratrol significantly decreased NAD(P)H oxidase activity in Leprdb mice. Furthermore, dbTNF−/dbTNF− and Leprdb mice treated with the NF-κB inhibitor MG-132 showed reduced NAD(P)H oxidase activity, whereas m-Leprdb mice treated with recombinant TNF-α exhibited enhanced NAD(P)H oxidase activation.

Fig. 5.

RSV inhibited NAD(P)H oxidase-derived O2·− production. A: O2·− production was higher in Leprdb versus m-Leprdb mice. RSV and the NAD(P)H oxidase inhibitor apocynin (20 mg·kg−1·day−1 ip, 3 days) reversed O2·− production back to the level of m-Leprdb control mice. Data are means ± SD; n = 5 mice. *P < 0.05 vs. m-Leprdb mice; #P < 0.05 vs. Leprdb mice. B: NAD(P)H oxidase activity was higher in Leprdb mice than in m-Leprdb mice. RSV significantly decreased NAD(P)H oxidase activity in Leprdb mice without affecting that in m-Leprdb mice. Furthermore, dbTNF−/dbTNF− and Leprdb mice treated with the NF-κB inhibitor MG-132 showed decreased NAD(P)H oxidase activity, whereas m-Leprdb mice treated with recombinant TNF-α exhibited enhanced NAD(P)H oxidase activation. Data are means ± SD; n = 6 mice. *P < 0.05 vs. m-Leprdb mice; #P < 0.05 vs. Leprdb mice.

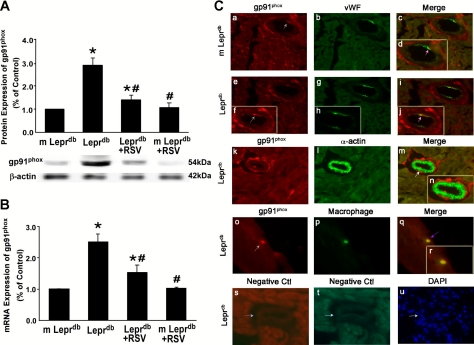

Resveratrol Decreased Protein and mRNA Expression of gp91phox in Type 2 Diabetes and Cellular Sources of gp91phox

We studied the expression of NAD(P)H oxidase subunits p22phox, gp91phox, and p67phox. Figure 6, A and B, show that protein and mRNA expression of gp91phox were significantly higher in Leprdb mice. Resveratrol decreased gp91phox protein and mRNA expression in Leprdb mice. In contrast, protein expression of p22phox and p67phox showed no significant differences among groups (data not shown). Markers for endothelial cells (von Willebrand factor), vascular smooth muscle cells (α-actin), or macrophages (F4/80) along with gp91phox to establish the cell type expressing gp91phox suggested that gp91phox was localized in endothelial cells and macrophages in heart tissue (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

RSV diminished protein and mRNA expression of NAD(P)H oxidase subunit gp91phox. A and B: gp91phox protein and mRNA expression were enhanced in Leprdb mice. RSV decreased gp91phox expression in Leprdb mice. Data are means ± SD; n = 4 separate experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. m-Leprdb mice; #P < 0.05 vs. Leprdb mice. C: dual fluorescence combining gp91phox with markers for endothelial cells [von Willebrand Factor (vWF)], vascular smooth muscle (α-actin), and macrophages (F4/80) with the use of specific antibodies followed by fluorescent-labeled secondary antibodies. a–c, Dual labeling of gp91phox (red) and vWF (green) in m-Leprdb heart tissue. d, Higher magnification view of c. e, g, and i, Dual labeling of gp91phox (red) and vWF (green) in Leprdb heart tissue. f, h, and j, Higher magnification views of e, g, and i, respectively. The gray arrow in f shows the staining of gp91phox (red), and the pink arrows in d and j show the colocalization of gp91phox and endothelial cells (yellow). k–m, Dual labeling of gp91phox (red) and α-actin (green) in Leprdb heart tissue. The white arrow in m shows specific α-actin staining with an absence of gp91phox staining. n, Higher magnification view of m. o–q, Dual labeling of gp91phox (red) and F4/80 (green) in Leprdb heart tissue. The purple arrow in q shows colocalization of gp91phox and F4/80 (yellow). r, Higher magnication view of q. s and t, negative controls (Ctl). The blue arrow shows an absence of staining in vessels with the secondary antibodies. u, Nuclear staining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue) in Leprdb heart tissue. Magnification: ×40. Data shown are representative of 4 separate experiments.

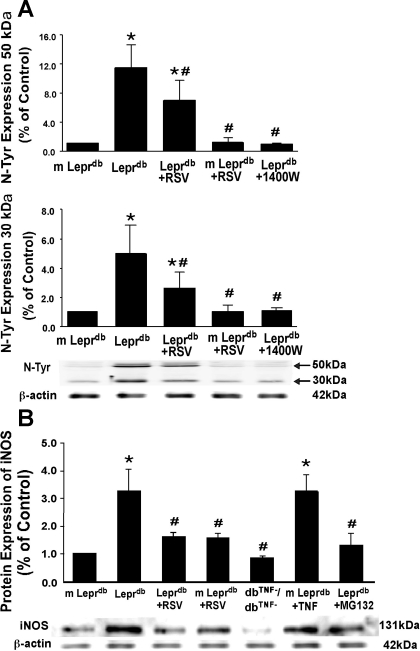

Resveratrol Downregulated Protein Expression of iNOS and N-Tyr in Type 2 Diabetes

Western Blot analysis (Fig. 7A) for N-Tyr revealed significantly higher levels of N-Tyr in Leprdb mice, which were reduced by resveratrol and treatment with the iNOS inhibitor 1400W (10 mg·kg−1·day−1 ip, 4 days). Protein expression of iNOS was higher in Leprdb mice compared with m-Leprdb mice. The administration of resveratrol reduced iNOS expression in Leprdb mice. Moreover, dbTNF−/dbTNF− and Leprdb mice treated with the NF-κB inhibitor MG-132 showed decreased iNOS protein expression, whereas m-Leprdb mice treated with recombinant TNF-α exhibited elevated iNOS expression (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

RSV reduced nitrotyrosine (N-Tyr) and inducible NO synthase (iNOS) protein expression. A: both 50- and 30-kDa bands of N-Tyr expression were higher in Leprdb mice than in m-Leprdb mice. Treatment with RSV and the iNOS inhibitor (10 mg·kg−1·day−1 ip, 4 days) decreased N-Tyr expression in Leprdb mice. Data are means ± SD; n = 4 separate experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. m-Leprdb mice; #P < 0.05 vs. Leprdb mice. B: effects of RSV on iNOS protein expression. Protein expression of iNOS was higher in Leprdb versus m-Leprdb mice. The administration of resveratrol reduced iNOS expression in Leprdb mice. dbTNF−/dbTNF− and Leprdb mice treated with the NF-κB inhibitor MG-132 showed reduced iNOS expression, whereas iNOS expression was markedly elevated in m-Leprdb mice treated with recombinant TNF-α. Data are means ± SE; n = 4 separate experiments. *P < 0.05 vs. m-Leprdb mice; #P < 0.05 vs. Leprdb mice.

DISCUSSION

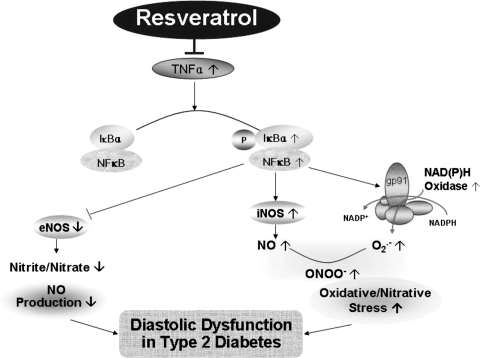

The major finding of this study is that resveratrol is cardioprotective in mice with diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cardiomyopathy in this model is manifested as impaired diastolic relaxation measured by a reduction in the early filling phase of diastole. In addition, during systole, we measured reduced peak ejection. Despite reduced PER, LV EF was not impaired. We found that the resveratrol-treated diabetic mice showed lower levels of oxidative/nitrative stress with an improvement of NO availability. This suggests that the mechanisms responsible for the improvement in LV diastolic relaxation with resveratrol were due to the inhibition of oxidative/nitrative stress and improvement of NO availability in this model (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

RSV protects against diastolic dysfunction by inhibiting oxidative/nitrative stress and improving NO availability. This improvement is due to the role of RSV in inhibiting TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation, therefore subsequently inhibiting the expression and activation of NAD(P)H oxidase and iNOS as well as increasing eNOS expression in type 2 diabetes.

Cardioprotective Effects of Resveratrol in Type 2 Diabetes

The cardioprotective effects of resveratrol have been studied in various disease models. Echocardiographic analyses showed that resveratrol reduced isovolumic relaxation time, a parameter of diastolic function, in aging (3) and pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy (aortic banded rat model) (16). In a rat model of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, in vivo LV catheterization showed that resveratrol pretreatment increased LV maximum systolic pressures and dP/dtmax and decreased myocardial infarct size (35). Using in vivo MRI, we demonstrated that resveratrol improved cardiac function in type 2 diabetic mice. The results suggested that at 16 wk old, although SV was only marginally decreased in male Leprdb mice, CO was significantly diminished (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Both PER and PFR were significantly lower in Leprdb mice, suggesting the early impairment of systolic and diastolic function. Systolic dysfunction is more likely dependent on the degree of myocyte loss and myocyte injury, which account for reduced contractility, decreased pump function, and EF (10). Resveratrol did not exhibit significant benefits in improving SV, CO, or PER, but greatly increased PFR (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Therefore, we posit that resveratrol exerts a beneficial role in diabetic cardiomyopathy mainly by improving diastolic function. Although resveratrol prevented diet-induced obesity and alleviated insulin resistance in high-fat diet-fed mice and streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetic rats, in Leprdb mice, resveratrol did not alter body weight or reduce hyperinsulinemic hyperglycemia (49). Thus, the therapeutic effects of resveratrol, especially on cardiac dysfunction, can also occur independently of weight loss and hyperglycemic status.

Furthermore, Leprdb mice had a lower LVM-to-body mass ratio compared with m-Leprdb mice (Table 1). These results are consistent with a previous investigation of hearts using MRI in type 2 diabetic mice by Panagia et al. (28). Although resveratrol improved diastolic function, it showed no marked effect via a morphological change of the heart in both m-Leprdb and Leprdb mice. Therefore, early intervention by resveratrol supplementation might be a promising approach to prevent or delay the onset of diabetic cardiomyopathy.

Resveratrol Reduced Cardiac TNF-α Expression and NF-κB Activation

Resveratrol inhibited TNF-α production by the LPS-activated brain macrophage, the microglia (4). It also abrogated cigarette smoking-induced upregulation of TNF-α in rat carotid arteries (7). We demonstrated that TNF-α mRNA and protein expression were elevated in type 2 diabetic mouse cardiac tissue and that resveratrol inhibited TNF-α expression in type 2 diabetes (Fig. 2). The TNF-α inhibitory effects of resveratrol may contribute to its cardioprotective benefits since TNF-α has been shown to be a prognostic marker in patients with heart failure. Etanercept, a soluble TNF-α receptor antagonist, attenuated LV dilatation and restored EF in progressive LV dysfunction in a pacing-induced heart failure dog model (23). There is a controversial role of TNF-α antagonists in the clinical treatment of heart failure. A clinical study (20) has shown a lack of benefits of anti-TNF-α treatment in patients with chronic heart failure in a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Despite these findings, further investigation is needed to determine if individualized dosing of anti-TNF-α therapy will exhibit beneficial effects by treating patients with early-stage cardiac dysfunction before any final conclusions can be made (24).

Resveratrol not only inhibits TNF-α expression but also inhibits NF-κB activation. Our study suggests that total IκB-α expression was decreased in Leprdb mice, whereas IκB-α phosphorylation and NF-κB p65 expression were elevated (Fig. 3). Resveratrol inhibited phospho-IκB-α and NFκB p65 expression without affecting total IκB-α expression in Leprdb mice (Fig. 3). These results suggest that resveratrol inhibits NF-κB activation by preventing the phosphorylation of IκB-α, therefore abolishing the downstream signaling induced by NF-κB activation.

Effects of Resveratrol on NO Production and eNOS Expression

Agonist-stimulated release of NO from eNOS in the coronary endothelium exerts paracrine effects on cardiomyocytes, predominantly affecting the timing of relaxation as well as myocardial O2 consumption (32). The autocrine role of eNOS within cardiomyocytes may include the modulation of basal inotropy and relaxation, β-adrenergic responsiveness, and the force-frequency relationship (32). eNOS−/− mice are not only hypertensive but also characterized by enhanced systolic function and depressed diastolic function without LV hypertrophy (30). Moreover, inhibition of basal NO production by the NOS inhibitor NG-monomethyl-l-arginine significantly impaired LV diastolic filling (6). This suggests that NO derived from eNOS contributes to myocardial relaxation (29).

In a pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy rat model, eNOS and redox factor-1 expression were significantly reduced. Resveratrol increased eNOS and redox factor-1 expression and improved diastolic relaxation (16). Our results suggest that resveratrol at a dose of 20 mg·kg−1·day−1 increased eNOS protein expression in Leprdb mice (Fig. 4B), which was associated with enhanced myocardial nitrite/nitrate levels, a parameter of NO production (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, dbTNF−/dbTNF− and Leprdb mice treated with MG-132 exhibited elevated eNOS protein expression, whereas eNOS expression was reduced in m-Leprdb mice with recombinant TNF-α treatment (Fig. 4B), suggesting that resveratrol may affect eNOS expression by inhibiting TNF-α-NF-κB signaling. Thus, resveratrol's benefits in improving cardiac filling of diabetic mice may ameliorate cardiomyopathy by enhancing eNOS-derived NO production.

Effects of Resveratrol on NAD(P)H Oxidase Subunit Expression, NAD(P)H Oxidase Activation, and Subsequent O2·− Production

NO production by eNOS does not accurately reflect NO availability since inactivation of NO by ROS is recognized to be a key mechanism underlying reduced NO bioavailability (5). A previous study (36) suggested that LV diastolic function is correlated with oxidative stress. Therefore, we evaluated oxidative stress in cardiac tissue of diabetic mice. Despite the presence of multiple ROS sources, studies (13, 14) in the last decade have indicated that the major cardiovascular source of ROS, particularly in the vasculature, originates from a family of NADPH oxidases.

Our previous studies (11, 12) have indicated that dbTNF−/dbTNF− and MG-132-treated Leprdb mice exhibit reduced NAD(P)H oxidase activity in coronary arterioles. The present study showed that NAD(P)H oxidase activity was elevated in the cardiac tissue of Leprdb mice, whereas dbTNF−/dbTNF− and MG132-treated Leprdb mice revealed ameliorated NAD(P)H oxidase activation (Fig. 5B). O2·− production was elevated in Leprdb mice, and the NAD(P)H oxidase inhibitor apocynin reduced O2·− production back to the level of the m-Leprdb control, suggesting that NAD(P)H oxidase may be one of the main sources of O2·− production in diabetic mouse cardiac tissue (Fig. 5A). Resveratrol inhibited NAD(P)H oxidase activity and subsequent O2·− production, possibly by inhibiting TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation.

The classical NADPH oxidase complex comprises membrane-bound cytochrome b558 (composed of one gp91phox subunit and one p22phox subunit), which forms the catalytic core of the enzyme, and four cytosolic regulatory subunits (p47phox, p67phox, p40phox, and Rac) (19). gp91phox is one of the most important subunits in NAD(P)H oxidase-mediated oxidative stress since deletion of gp91phox severely inhibits activated O2·− production (1). We determined that gp91phox protein and mRNA expression were elevated in diabetic mice (Fig. 6, A and B), whereas p22phox and p67phox protein expression showed no significant differences between m-Leprdb and Leprdb mice (data not shown). Resveratrol greatly reduced gp91phox mRNA and protein expression, suggesting that resveratrol may abrogate NAD(P)H oxidase activation by interrupting NAD(P)H oxidase subunit gp91phox expression. Immunofluorescence staining suggested that gp91phox is mainly colocalized with endothelial cells and macrophages in cardiac tissue (Fig. 6C). Thus, the antioxidative effects may contribute to the cardioprotective effects by resveratrol via LV relaxation.

Effects of Resveratrol on iNOS Expression and Subsequent Nitrative Stress

iNOS is induced by inflammatory cytokines and produces a much higher level of NO compared with constitutive NOS (43). Cardiac myocytes, as well as a number of other parenchymal cells within the myocardium, including the endothelium of the coronary microvasculature, endocardium, and infiltrating inflammatory cells, are all able to express iNOS in response to soluble inflammatory mediators (2). A recent study (43) demonstrated that pathological concentrations of NO produced by iNOS may result in nitrative stress and tissue injury by generating the powerful nitrative molecule peroxynitrite (ONOO−). A transgenic mouse model conditionally targeting the expression of human iNOS cDNA to the myocardium displayed upregulation of iNOS, which led to an increased production of ONOO−. Those mice infrequently developed overt heart failure but displayed a high incidence of sudden cardiac death due to bradyarrhythmia (25). Myocardial reperfusion injury increased iNOS expression and subsequent generation of RNS (N-Tyr), which was prevented by pretreatment with 1400W, a selective iNOS inhibitor, or M-40401, an ONOO− scavenger (39). Thus, nitrative stress and peroxynitrite play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of diabetic cardiomyopathy (26, 27). Our study reveals that iNOS expression was enhanced in the cardiac tissue of Leprdb mice, concurrent with elevated N-Tyr expression in the presence of excessive O2·−. The iNOS inhibitor 1400W reversed the increased N-Tyr expression, suggesting a role for iNOS in the increased RNS production in the diabetic cardiomyocyte (Fig. 7A). Therefore, we postulate that the effects of resveratrol on reducing cardiac N-Tyr expression might be partially explained by its role in inhibiting iNOS expression (Fig. 7B). Although iNOS expression was increased in the cardiac tissue of diabetic mice versus control mice, iNOS protein expression in aortas was not different between control and diabetic mice (data not shown). Moreover, 50-kDa N-Tyr protein expression was over 10 times higher in the heart of diabetic mice compared with control mice, whereas it was only 3 times higher in the aorta of diabetic mice versus control mice (49), supporting the view of more marked nitrative stress in the cardiac tissue of type 2 diabetic mice.

NF-κB activation is required for TNF-α-induced iNOS gene expression in both human liver (AKN-1) and human lung (A549) epithelial cell lines (40). We found that dbTNF−/dbTNF− and Leprdb mice treated with MG-132 exhibited decreased iNOS expression, whereas iNOS expression was elevated in m-Leprdb mice treated with anti-TNF-α versus control m-Leprdb mice (Fig. 7B). These findings suggest that TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation may upregulate iNOS expression in diabetic mouse cardiac tissue.

Resveratrol Regulates the Imbalance of NO and O2·− in Type 2 Diabetes

A complex paracrine interaction exists between endothelial cells and cardiac myocytes in the heart. Cardiac endothelial cells release (or metabolize) several diffusible agents that exert direct effects on myocyte function, independent of changes in coronary flow (33). The role of NO in this paracrine/autocrine pathway is active due to the short diffusion distance between cardiac microvessel endothelial cells and ventricular cardiomyocyte (<1 μm) (38). In pathological situations, the beneficial effects of NO resulting from eNOS-derived NO were diminished by either reduced production or enhanced inactivation by ROS. There can also be deleterious effects of NO that result from excessive NO production by iNOS, usually with concurrent ROS production and ONOO− formation (33). Thus, the balance between NO and ROS production is a major factor in the pathophysiological state of the cardiovasculature.

Resveratrol inhibits NAD(P)H oxidase-derived O2·− as well as iNOS-derived NO but stimulates eNOS-derived NO production. This prevents cardiac oxidative/nitrative stress and improves NO availability. Therefore, by regulating the imbalance between NO and ROS, resveratrol is postulated to be efficient in ameliorating oxidative/nitrative stress and subsequent tissue damage in the diabetic heart.

Conclusions

In conclusion, MRI assessment of cardiac function in diabetic mice supports the existence of diabetic cardiomyopathy in this animal model of type 2 diabetes. Reduced systolic function and abnormal diastolic function were evident in 16-wk-old diabetic mice. Importantly, systolic and diastolic dysfunction in the diabetic hearts were not associated with cardiac hypertrophy because the measured wall thickness (data not shown) and calculated LVM were not increased (Table 1). This alteration coexisted with enhanced TNF-α expression, NF-κB activation, and NF-κB downstream signaling, which contributed to the perpetuation of oxidative/nitrative stress as well as decreased NO availability. Our results in resveratrol-treated Leprdb mice showed normalized diastolic function, suggesting that pharmacological interventions to promote NO availability and suppress oxidative/nitrative stress may reduce diabetes-induced cardiac dysfunction. We suggest that resveratrol has a potential role as a novel pharmacological agent in restoring cardiac function during the early stages of diabetic cardiomyopathy.

GRANTS

This work was supported by Pfizer Atorvastatin Research Award 2004-37, American Heart Association Scientific Development Grant 110350047A, and National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants RO1-HL-077566 and RO1-HL-085119 (to C. Zhang). L. Ma was supported by NIH Grant P50-CA-10313 and United States Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Research Program Grant PC081264. H. Zhang was supported by NIH Clinical Biodetectives Training Grant R90-DK-70105. B. Morgan was supported by NIH Clinical Biodetectives Training Grant T90-DK-071510.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge Ashley Brown for technical assistance as well as the MRI facility support provided by the Veterans Affairs Biomolecular Imaging Center at the Harry S. Truman Memorial Veterans Hospital and the University of Missouri (Columbia, MO).

REFERENCES

- 1.Archer SL, Reeve HL, Michelakis E, Puttagunta L, Waite R, Nelson DP, Dinauer MC, Weir EK. O2 sensing is preserved in mice lacking the gp91phox subunit of NADPH oxidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 7944–7949, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arstall MA, Sawyer DB, Fukazawa R, Kelly RA. Cytokine-mediated apoptosis in cardiac myocytes: the role of inducible nitric oxide synthase induction and peroxynitrite generation. Circ Res 85: 829–840, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barger JL, Kayo T, Vann JM, Arias EB, Wang J, Hacker TA, Wang Y, Raederstorff D, Morrow JD, Leeuwenburgh C, Allison DB, Saupe KW, Cartee GD, Weindruch R, Prolla TA. A low dose of dietary resveratrol partially mimics caloric restriction and retards aging parameters in mice. PLoS ONE 3: e2264, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bi XL, Yang JY, Dong YX, Wang JM, Cui YH, Ikeshima T, Zhao YQ, Wu CF. Resveratrol inhibits nitric oxide and TNF-α production by lipopolysaccharide-activated microglia. Int Immunopharmacol 5: 185–193, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai H, Harrison DG. Endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases: the role of oxidant stress. Circ Res 87: 840–844, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarkson PB, Lim PO, MacDonald TM. Influence of basal nitric oxide secretion on cardiac function in man. Br J Clin Pharmacol 40: 299–305, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Csiszar A, Labinskyy N, Podlutsky A, Kaminski PM, Wolin MS, Zhang C, Mukhopadhyay P, Pacher P, Hu F, de Cabo R, Ballabh P, Ungvari Z. Vasoprotective effects of resveratrol and SIRT1: attenuation of cigarette smoke-induced oxidative stress and proinflammatory phenotypic alterations. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H2721–H2735, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Lorgeril M, Salen P, Martin JL, Monjaud I, Delaye J, Mamelle N. Mediterranean diet, traditional risk factors, and the rate of cardiovascular complications after myocardial infarction: final report of the Lyon Diet Heart Study. Circulation 99: 779–785, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eybl V, Kotyzova D, Koutensky J. Comparative study of natural antioxidants–curcumin, resveratrol and melatonin–in cadmium-induced oxidative damage in mice. Toxicology 225: 150–156, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fang ZY, Prins JB, Marwick TH. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: evidence, mechanisms, and therapeutic implications. Endocr Rev 25: 543–567, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao X, Belmadani S, Picchi A, Xu X, Potter BJ, Tewari-Singh N, Capobianco S, Chilian WM, Zhang C. Tumor necrosis factor-α induces endothelial dysfunction in Leprdb mice. Circulation 115: 245–254, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao X, Zhang H, Schmidt AM, Zhang C. AGE/RAGE produces endothelial dysfunction in coronary arterioles in type 2 diabetic mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295: H491–H498, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griendling KK, Sorescu D, Lassegue B, Ushio-Fukai M. Modulation of protein kinase activity and gene expression by reactive oxygen species and their role in vascular physiology and pathophysiology. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 20: 2175–2183, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griendling KK, Sorescu D, Ushio-Fukai M. NAD(P)H oxidase: role in cardiovascular biology and disease. Circ Res 86: 494–501, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heiberg E, Wigstrom L, Carlsson M, Bolger AF, Karlsson M. Time resolved three-dimensional automated segmentation of the left ventricle. Computers Cardiol 32: 599–602, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juric D, Wojciechowski P, Das DK, Netticadan T. Prevention of concentric hypertrophy and diastolic impairment in aortic-banded rats treated with resveratrol. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H2138–H2143, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kannel WB, Hjortland M, Castelli WP. Role of diabetes in congestive heart failure: the Framingham study. Am J Cardiol 34: 29–34, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keys A, Menotti A, Karvonen MJ, Aravanis C, Blackburn H, Buzina R, Djordjevic BS, Dontas AS, Fidanza F, Keys MH, et al. The diet and 15-year death rate in the seven countries study. Am J Epidemiol 124: 903–915, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lassegue B, Clempus RE. Vascular NAD(P)H oxidases: specific features, expression, and regulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 285: R277–R297, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mann DL, McMurray JJ, Packer M, Swedberg K, Borer JS, Colucci WS, Djian J, Drexler H, Feldman A, Kober L, Krum H, Liu P, Nieminen M, Tavazzi L, van Veldhuisen DJ, Waldenstrom A, Warren M, Westheim A, Zannad F, Fleming T. Targeted anticytokine therapy in patients with chronic heart failure: results of the Randomized Etanercept Worldwide Evaluation (RENEWAL). Circulation 109: 1594–1602, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miatello R, Vazquez M, Renna N, Cruzado M, Zumino AP, Risler N. Chronic administration of resveratrol prevents biochemical cardiovascular changes in fructose-fed rats. Am J Hypertens 18: 864–870, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mizushige K, Yao L, Noma T, Kiyomoto H, Yu Y, Hosomi N, Ohmori K, Matsuo H. Alteration in left ventricular diastolic filling and accumulation of myocardial collagen at insulin-resistant prediabetic stage of a type II diabetic rat model. Circulation 101: 899–907, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moe GW, Marin-Garcia J, Konig A, Goldenthal M, Lu X, Feng Q. In vivo TNF-α inhibition ameliorates cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in experimental heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H1813–H1820, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mousa SA, Goncharuk O, Miller D. Recent advances of TNF-α antagonists in rheumatoid arthritis and chronic heart failure. Expert Opin Biol Ther 7: 617–625, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mungrue IN, Gros R, You X, Pirani A, Azad A, Csont T, Schulz R, Butany J, Stewart DJ, Husain M. Cardiomyocyte overexpression of iNOS in mice results in peroxynitrite generation, heart block, and sudden death. J Clin Invest 109: 735–743, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pacher P, Beckman JS, Liaudet L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol Rev 87: 315–424, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pacher P, Szabo C. Role of peroxynitrite in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular complications of diabetes. Curr Opin Pharmacol 6: 136–141, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Panagia M, Schneider JE, Brown B, Cole MA, Clarke K. Abnormal function and glucose metabolism in the type-2 diabetic db/db mouse heart. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 85: 289–294, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paulus WJ, Vantrimpont PJ, Shah AM. Acute effects of nitric oxide on left ventricular relaxation and diastolic distensibility in humans. Assessment by bicoronary sodium nitroprusside infusion. Circulation 89: 2070–2078, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruetten H, Dimmeler S, Gehring D, Ihling C, Zeiher AM. Concentric left ventricular remodeling in endothelial nitric oxide synthase knockout mice by chronic pressure overload. Cardiovasc Res 66: 444–453, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schneider JE, Wiesmann F, Lygate CA, Neubauer S. How to perform an accurate assessment of cardiac function in mice using high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 8: 693–701, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seddon M, Shah AM, Casadei B. Cardiomyocytes as effectors of nitric oxide signalling. Cardiovasc Res 75: 315–326, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shah AM, MacCarthy PA. Paracrine and autocrine effects of nitric oxide on myocardial function. Pharmacol Ther 86: 49–86, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma S, Kulkarni SK, Chopra K. Effect of resveratrol, a polyphenolic phytoalexin, on thermal hyperalgesia in a mouse model of diabetic neuropathic pain. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 21: 89–94, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen M, Jia GL, Wang YM, Ma H. Cardioprotective effect of resvaratrol pretreatment on myocardial ischemia-reperfusion induced injury in rats. Vascul Pharmacol 45: 122–126, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shizukuda Y, Bolan CD, Tripodi DJ, Sachdev V, Nguyen TT, Botello G, Yau YY, Sidenko S, Inez E, Ali MI, Waclawiw MA, Leitman SF, Rosing DR. Does oxidative stress modulate left ventricular diastolic function in asymptomatic subjects with hereditary hemochromatosis? Echocardiography 26: 1153–1158, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simopoulos AP. The Mediterranean diets: what is so special about the diet of Greece? The scientific evidence. J Nutr 131: 3065S–3073S, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strijdom H, Jacobs S, Hattingh S, Page C, Lochner A. Nitric oxide production is higher in rat cardiac microvessel endothelial cells than ventricular cardiomyocytes in baseline and hypoxic conditions: a comparative study. FASEB J 20: 314–316, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tao L, Gao E, Jiao X, Yuan Y, Li S, Christopher TA, Lopez BL, Koch W, Chan L, Goldstein BJ, Ma XL. Adiponectin cardioprotection after myocardial ischemia/reperfusion involves the reduction of oxidative/nitrative stress. Circulation 115: 1408–1416, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor BS, de Vera ME, Ganster RW, Wang Q, Shapiro RA, Morris SM, Jr, Billiar TR, Geller DA. Multiple NF-κB enhancer elements regulate cytokine induction of the human inducible nitric oxide synthase gene. J Biol Chem 273: 15148–15156, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thirunavukkarasu M, Penumathsa SV, Koneru S, Juhasz B, Zhan L, Otani H, Bagchi D, Das DK, Maulik N. Resveratrol alleviates cardiac dysfunction in streptozotocin-induced diabetes: role of nitric oxide, thioredoxin, and heme oxygenase. Free Radic Biol Med 43: 720–729, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsika RW, Ma L, Kehat I, Schramm C, Simmer G, Morgan B, Fine DM, Hanft LM, McDonald KS, Molkentin JD, Krenz M, Yang S, Ji J. TEAD-1 overexpression in the mouse heart promotes an age-dependent heart dysfunction. J Biol Chem 285: 13721–13735, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang XL, Liu HR, Tao L, Liang F, Yan L, Zhao RR, Lopez BL, Christopher TA, Ma XL. Role of iNOS-derived reactive nitrogen species and resultant nitrative stress in leukocytes-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis after myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. Apoptosis 12: 1209–1217, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Whaley-Connell A, Govindarajan G, Habibi J, Hayden MR, Cooper SA, Wei Y, Ma L, Qazi M, Link D, Karuparthi PR, Stump C, Ferrario C, Sowers JR. Angiotensin II-mediated oxidative stress promotes myocardial tissue remodeling in the transgenic (mRen2) 27 Ren2 rat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E355–E363, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu X, Gao X, Potter BJ, Cao JM, Zhang C. Anti-LOX-1 rescues endothelial function in coronary arterioles in atherosclerotic ApoE knockout mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 871–877, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yue P, Arai T, Terashima M, Sheikh AY, Cao F, Charo D, Hoyt G, Robbins RC, Ashley EA, Wu J, Yang PC, Tsao PS. Magnetic resonance imaging of progressive cardiomyopathic changes in the db/db mouse. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H2106–H2118, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zarich SW, Nesto RW. Diabetic cardiomyopathy. Am Heart J 118: 1000–1012, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang C, Xu X, Potter BJ, Wang W, Kuo L, Michael L, Bagby GJ, Chilian WM. TNF-α contributes to endothelial dysfunction in ischemia/reperfusion injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26: 475–480, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang H, Zhang J, Ungvari Z, Zhang C. Resveratrol improves endothelial function: role of TNFα and vascular oxidative stress. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 29: 1164–1171, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]