Abstract

Modulation of synaptic strength by γ-aminobutyric acid receptors (GABARs) is a common feature in sensory pathways that contain relay cell types. However, the functional impact of these receptors on information processing is not clear. We considered this issue at bushy cells (BCs) in the cochlear nucleus, which relay auditory nerve (AN) activity to higher centers. BCs express GABAARs, and synaptic inputs to BCs express GABABRs. We tested the effects of GABAR activation on the relaying of AN activity using patch-clamp recordings in mature mouse brain slices at 34°C. GABA affected BC firing in response to trains of AN activity at concentrations as low as 10 μM. GABAARs reduced firing primarily late in high-frequency trains, whereas GABABRs reduced firing early and in low-frequency trains. BC firing was significantly restored when two converging AN inputs were activated simultaneously, with maximal effect over a window of <0.5 ms. Thus GABA could adjust the function of BCs, to suppress the relaying of individual inputs and require coincident activity of multiple inputs.

INTRODUCTION

The endbulb of Held is a large, glutamatergic synapse made by auditory nerve (AN) fibers onto bushy cells (BCs) in the anteroventral cochlear nucleus (AVCN) (Brawer and Morest 1975; Ryugo and Fekete 1982). BCs play an important role in relaying the temporal information in AN spike trains on to higher centers involved in sound localization (Cant and Casseday 1986; Smith et al. 1991, 1993; Spirou et al. 1990).

Although BCs are often characterized as simple relay cells, several lines of evidence indicate that they modify information carried by AN fibers. First, not all BCs recorded in vivo show the monotonic rate-level functions stereotypical of AN fibers (Kopp-Scheinpflug et al. 2002; Winter and Palmer 1991). Second, the spikes elicited in response to sounds can be more temporally precise in BCs than in AN fibers, probably through the convergence of multiple AN inputs (Burkitt and Clark 1999; Joris et al. 1994; Rothman et al. 1993; Spirou et al. 2005; Xu-Friedman and Regehr 2005a,b). Third, in in vitro recordings, the endbulb depresses considerably during high-frequency firing of ANs (Bellingham and Walmsley 1999; Wang and Manis 2008; Yang and Xu-Friedman 2008; Zhang and Trussell 1994), which is expected to reduce the probability of BC firing at the later pulses of a train of activity and thus to reduce the fidelity of relaying (Yang and Xu-Friedman 2009).

An important mechanism for modulating the response properties of BCs is through activation of inhibitory receptors. BCs can have inhibitory regions in their tuning characteristics (Brownell 1975; Rhode and Greenberg 1994). Although glycinergic inputs have received the most attention, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) immunoreactivity has also been found around BCs (Adams and Mugnaini 1987; Juiz et al. 1996; Mahendrasingam et al. 2000; Saint Marie et al. 1989) and BCs express ionotropic GABAA receptors (GABAARs) (Lim et al. 2000). GABAARs change the temporal response properties of neurons in other systems (Kuba et al. 2002; Pouille and Scanziani 2001). GABAAR antagonists influence rate-level functions of BCs in vivo (Caspary et al. 1994; Gai and Carney 2008; Kopp-Scheinpflug et al. 2002), but GABAergic inhibitory postsynaptic currents and potentials (IPSC/Ps) are very reduced in juvenile and mature slices (Lim et al. 2000; Wu and Oertel 1986), which raises questions about their function. In the chick, metabotropic GABAB receptors (GABABRs) can restore relay-like firing during high-frequency AN stimulation (Brenowitz et al. 1998). These effects seem to be important primarily in immature synapses (Brenowitz and Trussell 2001a), so it is not clear whether these properties apply at the mature mammalian endbulb.

We examined the possible effects of GABAR activation on the relay properties of the endbulb synapse using patch-clamp recordings in mature mouse AVCN (postnatal day 16 [P16] to P40) at near-physiological temperature. GABAAR activation hyperpolarized BCs, which decreased the probability of spiking late in trains of activity. GABABR activation decreased the probability of presynaptic neurotransmitter release, which decreased spike probability throughout trains of activity. This suppression of single inputs was overcome by precisely coincident activity of two independent endbulbs. This indicates that GABAR activation can modify the BC input–output relationship, so that single inputs would be filtered out and multiple coincident inputs would be necessary. This could enhance the timing information passed on by BCs.

METHODS

All procedures were approved by the University at Buffalo's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Parasagittal slices (160 μm) of the AVCN were cut into ice-cold solution containing (in mM): 76 NaCl, 75 sucrose, 25 NaHCO3, 25 glucose, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 7 MgCl2, and 0.5 CaCl2, from CBA/CaJ mice aged P16–P40. Slices were incubated at 34°C for 30 min in standard recording solution containing (in mM): 125 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 20 glucose, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1 MgCl2, 1.5 CaCl2, 4 Na l-lactate, 2 Na-pyruvate, 0.4 Na l-ascorbate, bubbled with 95% O2-5% CO2. Slices were maintained at room temperature until recording. BCs were patched under an Olympus BX51WI microscope with a Multiclamp 700B (Molecular Devices) controlled by a PCI-6221 (National Instruments) interface driven by custom-written software (mafPC) running in Igor (WaveMetrics). The bath was perfused at 3–4 ml/min using a pump (403U/VM2; Watson-Marlow, Wilmington, MA), with saline running through an in-line heater (SH-27B with TC-324B controller; Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT).

Pipettes pulled from 1.5-mm OD, 0.86-mm ID borosilicate glass (Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA) to a resistance of 1–2 MΩ, were filled with (for voltage-clamp, in mM) 35 CsF, 100 CsCl, 10 EGTA, 10 HEPES, and 1 QX-314 or (for current-clamp, in mM) 130 KMeSO3, 10 NaCl, 10 HEPES, 2 MgCl2, 0.5 EGTA, 0.16 CaCl2, 4 Na2ATP, 0.4 NaGTP, and 14 Tris-creatine phosphate (pH adjusted to 7.3, 310 mOsm). All recordings were made in the presence of 10 μM strychnine to block glycine receptors. We find that this concentration does not have much effect on GABAAR-mediated currents elicited by GABA puff onto BC somata (Supplemental Fig. S1).1

Single presynaptic AN fibers were stimulated using a glass micropipette placed 30–50 μm away from the cell being recorded, with currents of 6–14 μA through a stimulus isolator (WPI A360 or A365). Activation of single presynaptic AN fibers was verified in all experiments by slightly decreasing the stimulus amplitude or moving the pipette slightly to a different position on the slice, which resulted in failure. We stimulated individual inputs near their thresholds to avoid stimulation of another input. For voltage-clamp, the holding potential was −70 mV, with access resistance 3–7 MΩ, compensated to 70%; for current-clamp, the resting potential was adjusted to −60 mV after break-in, but was not controlled afterward. BCs were identified in current-clamp by their undershooting spikes in response to depolarizing current steps (Oertel 1983) and in voltage-clamp by paired-pulse depression and extremely rapid excitatory postsynaptic current (EPSC) kinetics (Chanda and Xu-Friedman 2010; Isaacson and Walmsley 1995). We could not distinguish between globular and spherical BCs in our slice recordings. All recordings were made at about 34°C. Puff application of GABA was done using a Picospritzer III (Parker Instrumentation). AN inputs were stimulated 0.3 to 1.5 s after puff onset.

The pharmacological agents used were baclofen (100 μM), (2S)-3-[[(1S)-1-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)ethyl]amino-2-hydroxypropyl](phenylmethyl)phosphinic acid hydrochloride (CGP55845, 2 μM), 3-[(R)-2-carboxypiperazine-4-yl]-propyl-1-phosphinic acid (CPP, 5 μM), muscimol (100 μM), and bicuculline (25 μM). Most chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO); CGP55845 and CPP were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO); muscimol and bicuculline were from Ascent Scientific (Princeton, NJ). Muscimol experiments were conducted in the presence of CGP55845, to avoid nonspecific effects of muscimol on GABABRs (Yamauchi et al. 2000).

For confocal images in Fig. 3, three mice were perfused with 0.9% NaCl, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer. The brains were postfixed for 2 h before cryoprotecting overnight in 20% sucrose. Slices were cut at 30–40 μm on a sliding microtome (American Optical, Buffalo, NY), blocked in 5% goat serum, then incubated overnight in a 1:1,000 dilution of a rabbit anti-calretinin antibody (Sigma), followed by a goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa Fluor 594 from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) used at 1:200 dilution. Sections were mounted on slides and coverslipped under Fluoromount (Southern Biotech). Optical sections were made at 0.42 μm using a Zeiss Meta LSM 510 confocal microscope. Reconstructions were made using Reconstruct (Fiala 2005).

Fig. 3.

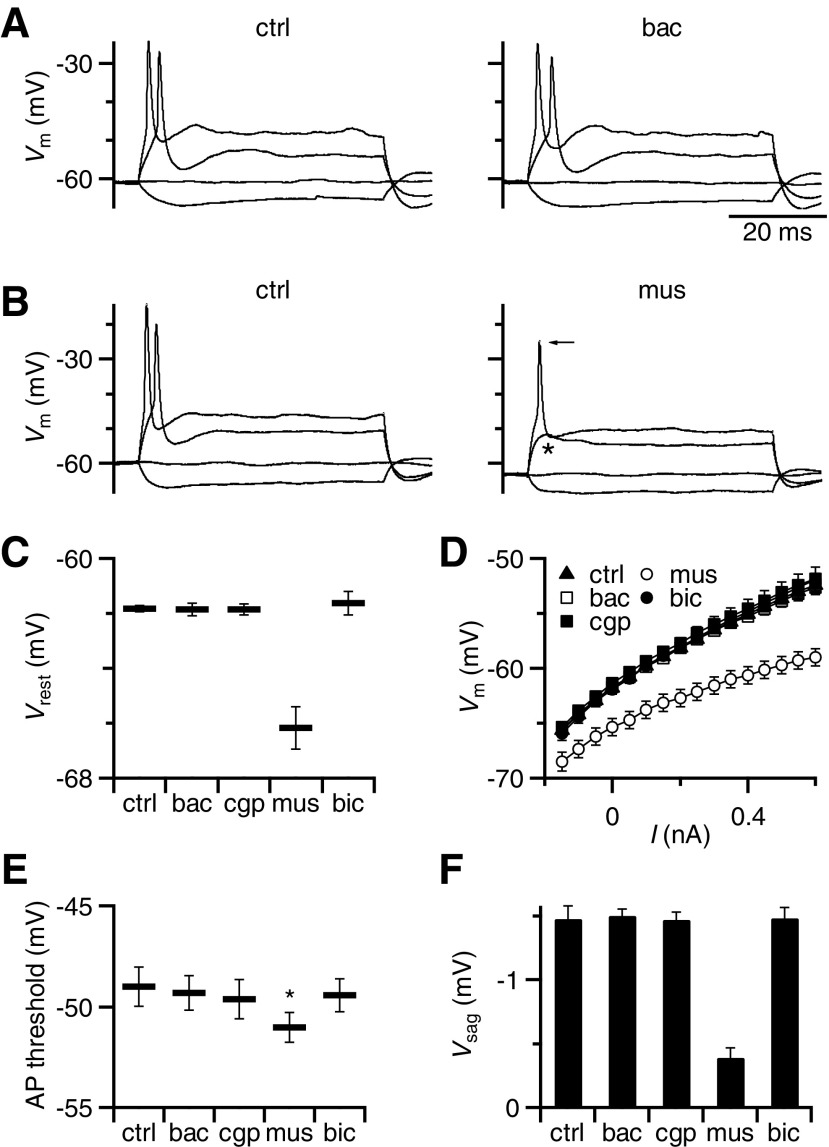

Postsynaptic effects of GABAR activation recorded in current-clamp. A: representative effects of baclofen on BC intrinsic properties. Family of responses to current injections ranging from −150 to 600 pA, showing no differences between control conditions (left) and in the presence of baclofen (right). The small depolarization that occurs during hyperpolarizing current pulses (the “sag” potential) reflects Ih activation (see results). B: same experiment as in A, but using muscimol application. Muscimol hyperpolarized the cell, increased the membrane conductance, blocked action potential (AP) firing (asterisk), and decreased the sag potential (Vsag) in response to hyperpolarization. There was also a small decrease in spike amplitude (arrow). C–F: average effects of GABAR agonists and antagonists on BC resting membrane potential (C), input resistance (D), AP threshold (E), and sag potential (F). Muscimol had a significant effect on each of these properties, but baclofen did not. Points are the averages of 8–9 experiments.

Average data are presented as means ± SE. Statistical significance was determined using the paired, one-tailed, Student's t-test, except where otherwise stated. Some effects are quantified as the relative change, which was calculated by subtracting the control value from the experimental and normalizing to the control, i.e., (test − control)/control.

RESULTS

Effect of GABAR activation on postsynaptic firing

As a first step toward understanding the functional impact of GABAR activation on BC firing, we stimulated single presynaptic AN fibers while recording from the postsynaptic BC in current-clamp. We used trains of 20 stimuli at frequencies similar to normal AN firing activity (i.e., 100, 200, and 333 Hz). In control conditions, a train of AN activation at 100 Hz usually leads to highly reliable firing in the BC (Fig. 1Ai, left trace). At higher activation rates, BC spiking becomes somewhat less reliable (Fig. 1Bi, left trace), presumably because of short-term synaptic depression, as has been shown in voltage-clamp recordings (Isaacson and Walmsley 1995; Wang and Manis 2008; Xu-Friedman and Regehr 2005a,b; Yang and Xu-Friedman 2008).

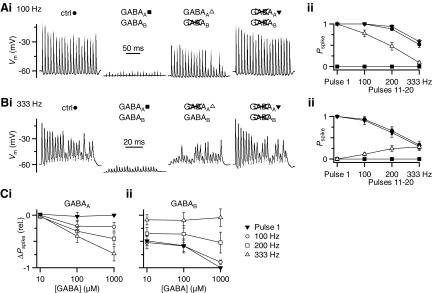

Fig. 1.

Effects of γ-aminobutyric acid receptor (GABAR) activation on bushy cell (BC) firing. Ai: example BC firing pattern for 100-Hz stimulation in control (left), with GABA puff (left, middle), with GABA puff in the presence of CGP55845 (right middle), and with GABA puff in the presence of CGP55845 + bicuculline (right). ii: average effects from 8 experiments similar to i and at different frequencies. BC spike probability (Pspike) is quantified separately for the first pulse in the train (pulse 1) and pulses 11–20 for trains of different frequencies. Symbols match the pharmacological conditions in i. GABA application alone decreases the firing probability throughout the train. CGP55845 completely restores spiking for the first pulse and also significantly increases the spike probability for pulses 11–20 at lower frequencies of stimulation. Bi: similar experiment to A, but showing example traces at 333-Hz stimulation and with the effects of GABA in the presence of bicuculline (right middle) applied before CGP55845. ii: average effects from 8 experiments, similar to i. Bicuculline application restores spiking to control levels for pulses 11–20 at 333 Hz, but has no effect on the first pulse and a weaker effect at 100- and 200-Hz stimulation. C: change in spike probability (ΔPspike) for the experiments in A and B calculated relative to control for GABA application in the presence of (i) CGP55845 to evaluate the contribution of GABAARs or (ii) bicuculline to evaluate the contribution of GABABRs. Changes were quantified as ΔPspike = (Pspikedrug/Pspikectrl) − 1. Each data point is the average of 6–8 cells. GABAAR activation has little effect on the first pulse, but it reduces BC spiking for pulses 11–20. This effect increases with firing frequency and GABA concentration. GABABR activation, by contrast, reduces spiking for pulse 1 as well as throughout the train for lower-frequency stimulation.

Activation of GABARs by pressure ejection of 1 mM GABA hyperpolarized the BC and eliminated action potential (AP) firing throughout the train (Fig. 1, Ai and Bi, center left traces). Excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) were visible, but were very small. We tested the contribution of specific GABAR subtypes by bath application of the receptor-specific antagonists CGP55845 (to block GABABRs) and bicuculline (to block GABAARs). When only GABAARs were activated, subsequent GABA puffs did not disrupt responses to initial pulses and later pulses were also restored to some degree (Fig. 1Ai, center right trace). This indicates that the BC response is highly sensitive to GABABR activation. We measured the effect of GABAAR activation on BC spiking by comparing the GABABR-blocked condition against control. GABAAR activation did not block spiking early in trains, although it did in later pulses (Fig. 1Ai).

A complementary effect was observed when only GABABRs were activated during GABA puff. Application of bicuculline restored spiking in the later part of the train, but not at the beginning (Fig. 1Bi). This indicates that GABABR activation has a substantial impact on suppressing spikes at the beginning of trains. Blocking both GABAARs and GABABRs prevented any effects of GABA puff (Fig. 1, Ai and Bi, rightmost traces).

We quantified the effect of GABAR activation on firing probability (Pspike) for the first pulse as well as pulses 11–20 in the train, where EPSC amplitudes appear to have reached steady-state levels of depression (Yang and Xu-Friedman 2008). Under control conditions, Pspike is highly reliable (close to 1), except for the later pulses of high-frequency trains (≥200 Hz; Fig. 1, Aii and Bii, closed circles). Application of 1 mM GABA eliminated spiking under all conditions tested (Fig. 1, Aii and Bii, closed squares). CGP55845 completely restored BC firing for pulse 1 and partly restored responses to the later pulses for lower firing frequencies, but not for higher frequencies (Fig. 1Aii, open triangles). This indicates that GABAAR activation primarily reduced the efficacy of late, depressed EPSPs. By contrast, GABA application in the presence of bicuculline (i.e., GABABR activation) greatly reduced Pspike for pulse 1 and for all pulses at low frequency, but had less effect on later pulses at high firing frequency (Fig. 1Bii, open triangles).

To understand better how GABA modulates the output function of BCs, we quantified changes in Pspike at three different GABA concentrations (10 μM, 100 μM, and 1 mM) in the presence of CGP55845 (to assess GABAARs) or bicuculline (to assess GABABRs) relative to the control. GABAAR activation had no effect on the first pulse (closed triangles) but it significantly reduced Pspike for later pulses in the train (Fig. 1Ci, open symbols). Furthermore, this effect increased with stimulation frequency (Fig. 1Ci). The effects of GABAAR activation were significant only at the highest GABA concentration tested (P < 0.01 for all pairwise comparisons at 1 mM GABA, paired two-tailed t-test). By contrast, GABABR activation greatly decreased Pspike for the first pulse (closed triangles) as well as later pulses in low-frequency trains (Fig. 1Cii, open circles). Late pulses in high-frequency trains scarcely changed with GABABR activation (Fig. 1Cii, open triangles). GABABRs significantly reduced Pspike for GABA concentrations as low as 10 μM, indicating that modulation of BC output is highly sensitive to GABA.

Contribution of GABAR subtypes

The mechanisms that likely underlie GABA's effects have been well studied in other systems, but it was important to confirm them at the mouse endbulb. We first approached this using voltage-clamp recordings from BCs and by activating GABARs using bath application of GABA (Supplemental Fig. S2). Bath application of GABA caused a considerable decrease in EPSC amplitude and changed the synapse from depressing to facilitating. This effect was highly sensitive to GABA, showing effects at concentrations as low as 1 μM. In addition, higher concentrations of GABA (>300 μM) caused a transient increase in the holding current (HC), which decreased within 2–3 min, probably because of receptor desensitization.

To better understand the basis for these multiple effects, we used specific GABAAR and GABABR agonists and antagonists. Application of the GABABR agonist baclofen significantly decreased the amplitude of the first EPSC of a pair (EPSC1) to 9 ± 1% of control (P < 0.001, n = 13, Fig. 2, A and C), but had no effect on the HC (Fig. 2E). In addition, baclofen application significantly increased the paired-pulse ratio (PPR) from 0.60 ± 0.04 to 1.19 ± 0.04, which is a 114 ± 21% increase relative to the control (Fig. 2, A and D). CGP55845 blocked the effect of baclofen and restored both EPSC1 and PPR (Fig. 2, A, C, and D). These effects indicate that GABABRs are responsible for changes in EPSC amplitude and that GABABRs are probably localized presynaptically on the endbulb terminals.

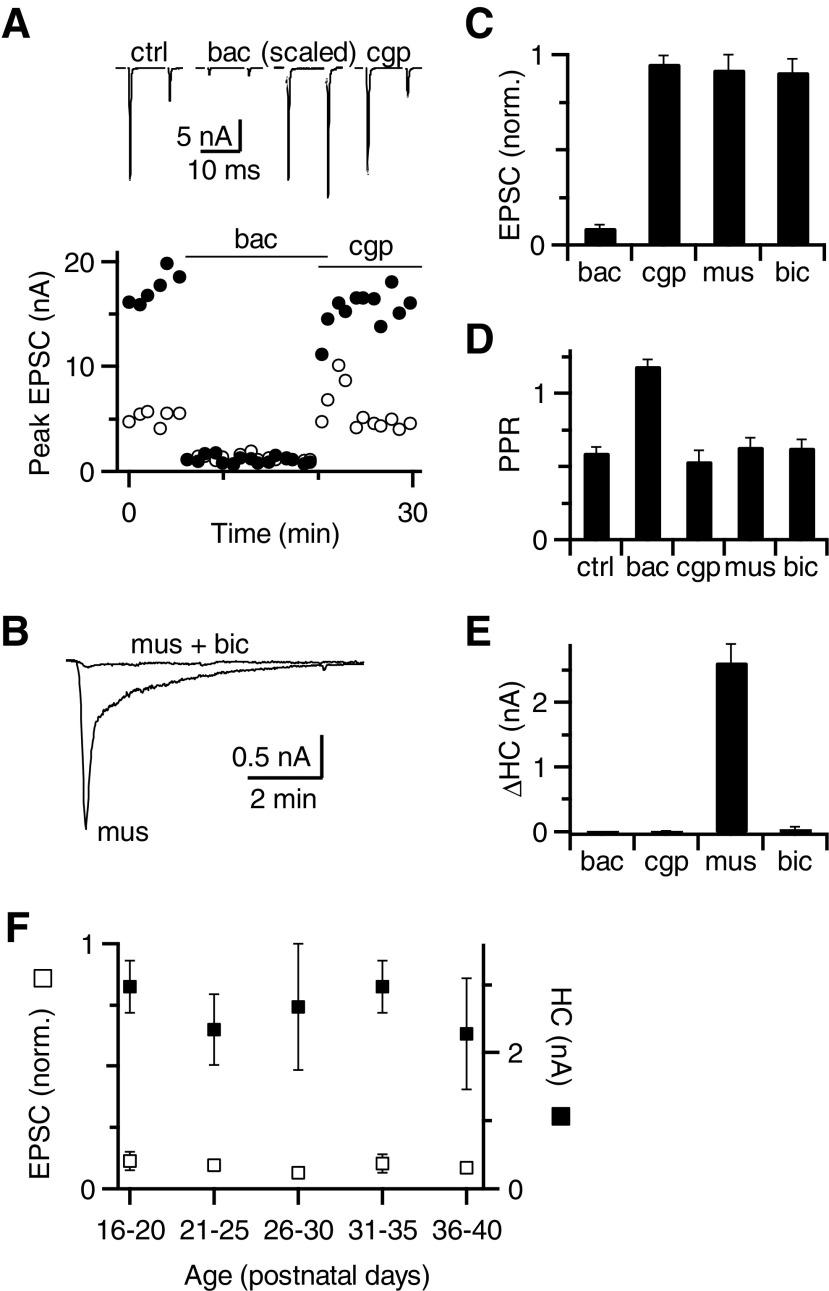

Fig. 2.

Subtypes of GABARs affecting synaptic transmission. A, top traces: average excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) in response to paired-pulse stimulation before and after application of baclofen and CGP55845. The EPSCs in baclofen are also shown scaled to the control EPSC1 amplitude. Bottom: peak EPSC amplitude measured during the experiment in response to the first (closed circles) and second (open circles) pulses. B: holding current (HC) in response to muscimol application. Bicuculline blocked the effect of muscimol. C–E: effects of GABAR agonists and antagonists on first EPSC amplitude (C), paired-pulse ratio (PPR, D), and HC (E). Only baclofen had a significant effect on EPSC amplitude and PPR (P < 0.001), which were both reversed by CGP55845 (see results). Only muscimol had a significant effect on HC (P < 0.001), which was reversed by bicuculline. Data are averages of 13 (baclofen and CGP) or 16 (muscimol and bicuculline) cells. F: average effect of baclofen on EPSC amplitude (open squares) and muscimol on HC (closed squares) for slices taken from mice of ages P16–P40. Each data point includes 3–6 cells. There were no significant changes in these effects with age.

We next tested the role of GABAAR activation using muscimol. Application of muscimol caused a transient increase in HC (2.63 ± 0.28 nA, n = 16 cells, Fig. 2, B and E), which was blocked by bicuculline. This suggests that the change in HC reflects activation of postsynaptic GABAARs. Muscimol application did not affect EPSC amplitude or PPR in the presence of CGP55845 (P > 0.05, n = 7 cells, Fig. 2, C and D), suggesting that GABAARs are probably not localized presynaptically.

To verify that the effects we saw were not a result of transient expression of GABARs in immature synapses, we conducted similar experiments on slices of animals of different ages (P16–P40). We found no significant change of GABAA or GABAB effects between different age groups (Fig. 2F). This suggests that GABAR expression has reached mature levels and is not a developmental artifact.

We further tested postsynaptic effects of GABARs by making current-clamp recordings from BCs. We delivered a series of depolarizing and hyperpolarizing current pulses in the presence of GABAR agonists and measured the resting membrane potential, input resistance, and AP threshold. For long hyperpolarizing pulses, we also measured the small depolarization in membrane potential (the “sag”), which presumably reflects activation of hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide gated (HCN) channels (Cao et al. 2007). Baclofen application did not have any significant effect on any of those postsynaptic properties (P > 0.2, n = 8 cells, Fig. 3, A and C–F). By contrast, muscimol application hyperpolarized the cell and significantly decreased the input resistance (P < 0.001, n = 8, Fig. 3, B–D). These two effects also had secondary effects on BCs, which included failure to spike in response to identical depolarizing current pulses (Fig. 3B, indicated by asterisk) and a decrease in the sag potential (Fig. 3, B and F). This was despite a small but significant decrease in AP threshold (Fig. 3E). We also noticed that AP height decreased slightly on muscimol application (Fig. 3B). Similar effects were observed when BCs were held at hyperpolarized potentials in the absence of any drug (data not shown). All these effects were blocked by bicuculline. These data support the conclusion that GABAARs are localized postsynaptically and that GABABRs do not directly influence postsynaptic spiking to any measurable extent.

We confirmed using perforated-patch recordings that GABAARs are conventionally hyperpolarizing in mice (Vrev = −101 ± 7 mV; Supplemental Fig. S3), similar to the findings in other rodents (Milenkovic et al. 2007), but not in the chick (Lu and Trussell 2001). This is consistent with the current-clamp recordings (Fig. 3) that muscimol, but not baclofen, led to BC hyperpolarization.

We confirmed whether GABABR activation decreases the probability of release through an effect on presynaptic calcium influx (Bean 1989). We tested this by changing the extracellular calcium (Cae) concentration from 1.5 to 0.6 or 0.7 mM. Low Cae largely mimicked baclofen's effects on evoked EPSCs (Supplemental Fig. S4). We further found that GABABR activation using baclofen significantly decreased miniature (m)EPSC frequency but not amplitude (Supplemental Fig. S5). This does not appear to result from a change in intraterminal calcium because varying Cae from 0.75 to 3 mM had no effects on mEPSC frequency or amplitude (Supplemental Fig. S6). Overall, these results suggest that GABABR activation reduces calcium influx and may affect the neurotransmitter release machinery downstream of calcium influx, but has no effect on postsynaptic α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor properties.

BC input–output function

Next we wanted to examine why GABAR activation led to the decrease in BC spiking observed in Fig. 1. Under control conditions, EPSCs showed considerable depression (Fig. 4A, top left trace). Application of baclofen decreased the EPSC amplitudes throughout the train (Fig. 4A, top middle trace). We normalized the amplitudes of train EPSCs to EPSC1 in control. With low-frequency stimulation (100 Hz), both the initial and later pulses were significantly reduced by baclofen application (P < 0.005, Fig. 4B). With high-frequency stimulation (333 Hz) baclofen decreased the amplitudes of the initial EPSCs but did not significantly change the later pulses (P > 0.2). These effects differ from the avian endbulb in which baclofen application led to an effective increase in EPSC amplitude late in high-frequency trains (Brenowitz and Trussell 2001a; Brenowitz et al. 1998). When the responses in trains under control and baclofen conditions were normalized by their respective EPSC1, baclofen-mediated facilitation lasted for the first half of trains of all frequencies, before showing mild depression for the second half (Fig. 4B, top open symbols).

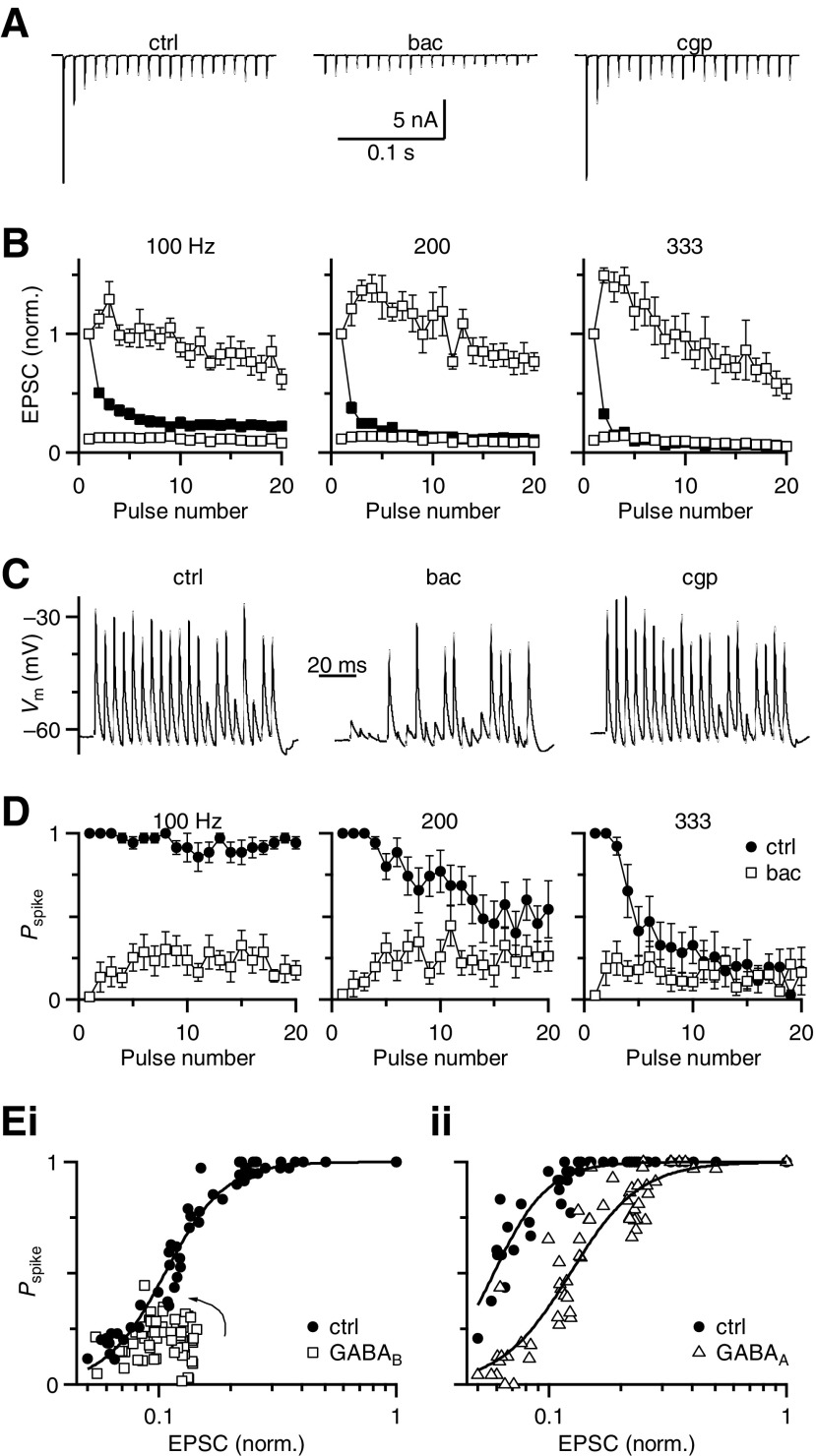

Fig. 4.

Changes in the BC input–output function after GABAR activation. A: example traces showing the effect of baclofen during a 100-Hz train of activity. Baclofen application significantly reduced EPSC amplitudes throughout the train. B: average EPSC amplitudes for different stimulation frequencies in control conditions (closed symbols) and in the presence of baclofen (open symbols). The top open symbols are normalized to EPSC1 in baclofen (EPSCibac/EPSC1bac), whereas the lower open symbols are normalized to EPSC1 in control (EPSCibac/EPSC1ctrl) (n = 7 cells). C: example traces showing high reliability during a 200-Hz train in control conditions (left), that decreased in baclofen (middle) and recovered in CGP55845. D: average BC firing probability (Pspike) throughout the train before and after baclofen application for different stimulation frequencies (n = 7 cells). Firing probability is reduced by baclofen at all frequencies. E: BC input–output function. i: Pspike after GABABR activation was plotted against normalized EPSC amplitudes from B. Pspike values were drawn from experiments using either bath-applied baclofen or puffed 1 mM GABA + bicuculline. Because these data are taken from trains of activation, there is also an activity-dependent effect, which is more obvious in the GABAB input–output curve. EPSCs begin at very low efficacy and increase somewhat during the train to approach the control curve (arrow). ii: Pspike after GABAAR activation was plotted against control EPSC data from B (because GABAAR activation does not change EPSC amplitude). Pspike values after GABAAR activation were drawn from puff experiments using 1 mM GABA in the presence of CGP55845. Pspike values for control conditions (open symbols) are derived from experiments before the respective GABAR activation. Error bars have been omitted for the sake of clarity. The data are fit using a Hill equation (see results).

We correlated these changes in EPSC amplitude with the changes in firing probability observed in current-clamp recordings. Baclofen application decreased BC firing probability and this was restored by CGP55845 (Fig. 4C). On average, the BC firing probability was significantly reduced by baclofen throughout 100-Hz trains (P < 0.001, n = 7, Fig. 4D). For 200- and 333-Hz trains, the firing probability of the initial spike was greatly reduced (P < 0.001, n = 7, Fig. 4D, middle and right panels), although later in the train it became more similar to the control conditions (P > 0.05, last 5 pulses of 200 Hz and last 10 pulses for 333 Hz, Fig. 4D, middle and right panels).

We used these data to evaluate the BC input–output function, compiling the results from all stimulation frequencies to probe a wide range of input values (i.e., EPSC amplitudes). These plots revealed that BC firing probability decreased steeply when the EPSC decreased to 20–25% of control (Fig. 4E). In this region, a small change in EPSC amplitude would result in a significant change in firing, irrespective of whether that change arose from depression or neuromodulation.

We then evaluated how GABABR activation changed the input–output function (Fig. 4Ei). We constructed the function using EPSCs measured in baclofen from Fig. 4B, plotted against Pspike values pooled from experiments using either baclofen (Fig. 4D) or 1 mM GABA + bicuculline (Fig. 1Cii) because their effects were indistinguishable. We fit these data to a Hill equation of the form Pspike = 1/[1 + (EPSC1/2/EPSC)rate] (lines in Fig. 4E). In control, the EPSC1/2 was 10.5 ± 0.2% and the rate was 3.4 ± 0.4. The primary effect of GABABR activation was to decrease EPSC amplitudes to the region of low spike probability (Fig. 4Ei). There are also clearly other factors that contribute to spike efficacy. Early in trains, EPSCs have particularly low efficacy and, as the train progresses, EPSCs do not greatly facilitate but efficacy increases (arrow, Fig. 4Ei). This presumably results from temporal summation of the EPSPs.

GABAAR activation had quite different effects on the input–output function (Fig. 4Eii). We plotted Pspike values from experiments similar to Fig. 1 before and after application of GABA + CGP55845 against the control EPSC amplitudes because GABAAR activation does not affect EPSC amplitude (Fig. 2). In this set of experiments, the control data were well fit by a Hill equation with slightly different parameters: EPSC1/2 = 5.8 ± 0.1% and rate = 3.8 ± 0.4. The input–output function was shifted to the right by GABAA activation, with EPSC1/2 of 12.3 ± 0.4% and a similar rate (3.0 ± 0.3). This indicates that with GABAAR activation, larger EPSPs were required to drive the cell to cross threshold and fire a spike. This would have the greatest impact during later pulses of high-frequency activity, where levels of depression are greatest. The greatest change in firing was for EPSC amplitudes of roughly 10% of resting values, where the decrease in spike probability was nearly 60%.

Multiple inputs

The input–output relationship in Fig. 4E had two important implications. First, the steepness of the relationship suggested that small changes in synaptic strength could significantly affect BC firing. Second, GABAR activation appears to place the synapse in a region of low spike probability, but in such a position that a doubling of the synaptic strength would lead to significant restoration of BC spiking. One factor that could cause such changes in synaptic strength would be the recruitment of additional synaptic inputs. BCs receive multiple AN fiber inputs, so if multiple inputs were active at the same time, the resulting summation could enable the cell to cross threshold to fire a spike.

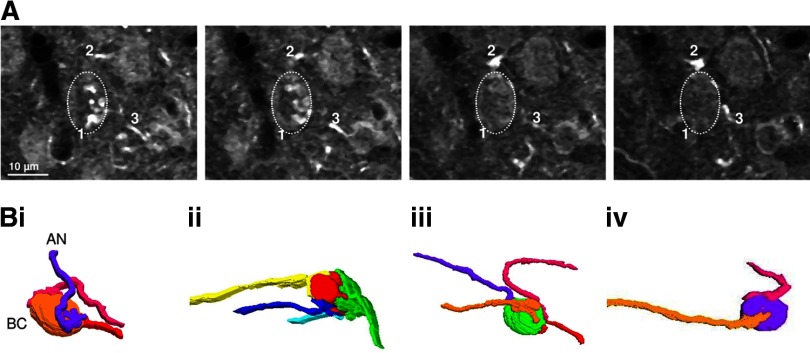

The number of converging endbulbs is not well known in mice. Physiological approaches have estimated two to five AN inputs per BC (Oertel 1985; Xu-Friedman and Regehr 2005a,b). We further investigated this issue using anatomical approaches, by taking advantage of the fact that AN fibers in CBA/CaJ mice have strong calretinin immunoreactivity, but other cell types in the AVCN do not (Fig. 5). We reconstructed AN fibers from confocal images and found that it was possible to trace labeled endbulbs to axons some distance away from the BC soma (Fig. 5A). We found that the number of endbulbs ranged from two to four (average 3.17 ± 0.31, n = 6, Fig. 5B). We consider this estimate to be a lower bound because some immunolabeled puncta could not be traced to an AN fiber or an identifiable endbulb. This is similar to the number of inputs measured using electron microscopy in rat BCs (Nicol and Walmsley 2002).

Fig. 5.

Multiple auditory nerve (AN) fibers converge on mouse BCs. A: 4 optical sections at 0.84-μm intervals taken from mouse AVCN labeled with an anti-calretinin antibody imaged with a confocal microscope. The dashed oval indicates a BC. Endbulbs were identified by their morphology and proximity to the BC and then traced back to their origin at distinct AN fibers. Different fibers are marked with different numbers. B: reconstructed images of 4 BCs and their AN inputs.

Convergence and GABAR activation

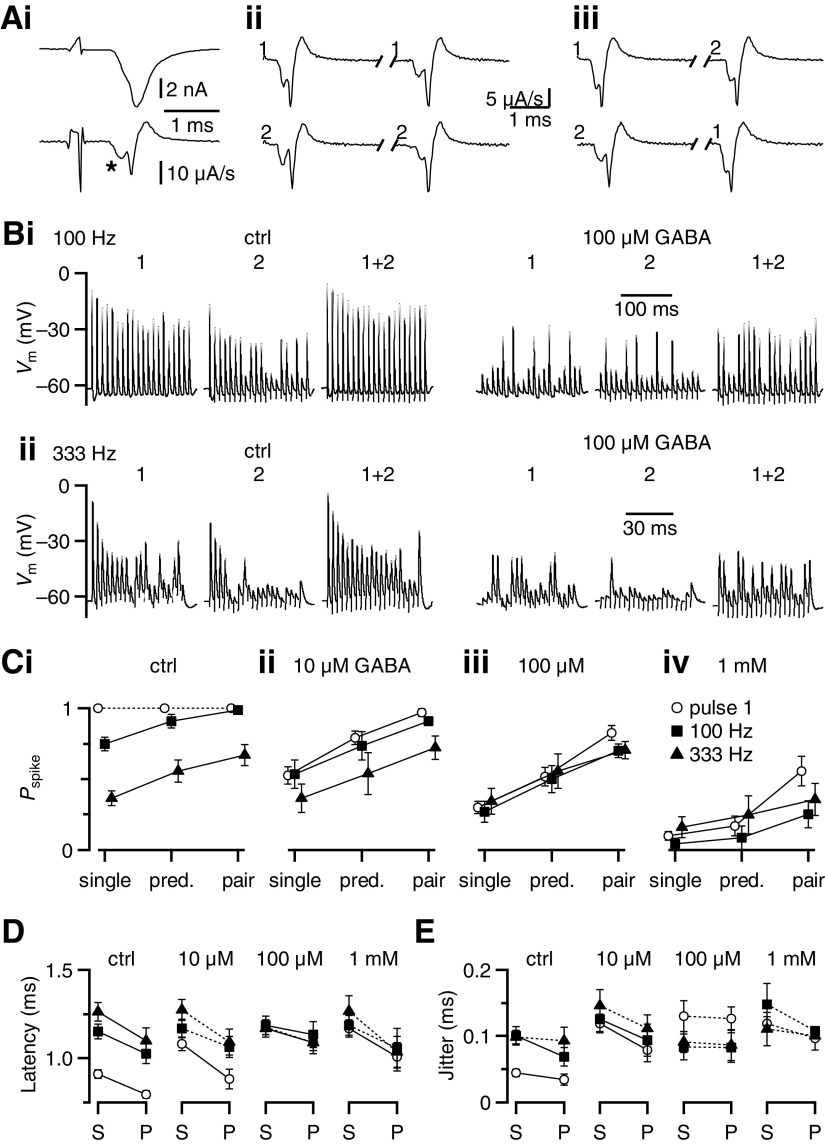

To test whether convergence of multiple inputs could affect firing probability, we quantified the BC spike probability in response to single or paired AN stimulation in the presence of different concentrations of GABA. To isolate distinct inputs, we made BC recordings in voltage-clamp mode. The potassium-based internal solution had imperfect voltage control, so spikes were typically observed following stimulation (Fig. 6Ai, top trace). The EPSCs were distinguished from spikes by using the first derivative of the response and examining the first peak (Fig. 6Ai, asterisk in bottom trace). We isolated two inputs using two stimulation pipettes and verified the inputs were different using cross-depression experiments. When a single input was stimulated twice, the second EPSC was depressed with respect to the first (Fig. 6Aii). However, when two inputs were alternately stimulated at a 10-ms interval, the amplitudes of the respective EPSCs were unaffected (Fig. 6Aiii), indicating that they were distinct inputs.

Fig. 6.

BC spiking is restored by simultaneous activity in 2 inputs. A: representative traces indicating the method of isolating 2 inputs using a potassium-based internal in voltage clamp. i: stimulation yields an EPSC with a superimposed spike (top trace) that can be better distinguished using the first derivative (bottom trace). The EPSC is indicated by an asterisk. Activation of each pathway at 10-ms interval showed paired-pulse depression (ii), but there was no depression when each pathway was stimulated alternately (iii), indicating they are separate inputs. B: representative traces showing the effects of 100 μM GABA on responses to single and paired stimulation in 2 different frequency trains. Responses to each individual input are shown in the 2 left traces in control conditions, with paired stimulation in the third traces. The next 2 traces show reduced spiking after GABA application. The rightmost trace shows that spiking is restored when both inputs are stimulated during GABAR activation. C: average effects of GABAR activation for single and paired stimulation on the probability of BC spiking using different concentrations of GABA: ctrl (i), 10 μM (ii), 100 μM (iii), and 1 mM (iv). Each point is the average of 7 or 8 cells. The “predicted” value represents the enhanced firing probability that is expected to result from spike summation, calculated from the responses to single inputs (see results). The additional enhancement seen with paired stimulation results from excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) summation. The firing probability increased significantly (P < 0.05) comparing between single and paired stimulation as well as between predicted and paired stimulation for all the conditions tested, except for pulse 1 in control, where firing probability was 100%. D and E: average effects of GABA application on the spike latency (D) and jitter (E) for single (“S”) or paired (“P”) stimuli. Each point represents averages of 5 to 8 cells. In some experiments, latency and jitter could not be calculated because of significant failure in AP firing. Significance (P < 0.05) is indicated by solid lines.

We next examined how multiple inputs interacted to drive BC firing. We stimulated two AN inputs individually with a 100-Hz train of stimuli (Fig. 6, Bi and Bii, left panels). When GABARs were activated by bath application of 100 μM GABA, the BC firing probability decreased in response to single input stimulation (Fig. 6Bi, right panels), consistent with the results of Fig. 1, at low and high frequencies. When both inputs were stimulated at the same time, BC spiking was greatly restored throughout the train (Fig. 6B, rightmost panels).

We quantified the effects of paired input stimulation (Fig. 6C). In control, the BC firing probability for the first pulse was always 100% and coincident activity had no additional effect. However, for pulses 11–20 of 100- or 333-Hz trains, depression caused a drop in efficacy for single inputs (Fig. 6Ci, “single”), similar to levels seen in Fig. 1. When both inputs were coactivated, the response probability increased (Fig. 6Ci, “pair”), indicating that coincident activity offsets the effects of depression.

When GABARs were activated, these effects were more pronounced. For GABA concentrations as low as 10 μM, the response to the first pulse was attenuated for single inputs, but when both inputs were activated spiking was nearly fully restored (Fig. 6Cii, “pair” vs. “single”). The late pulses in high-frequency trains showed a similar effect. At higher GABA concentrations, the degree of attenuation of single inputs was greater and spikes were nearly eliminated in 1 mM GABA (Fig. 6, Ciii and Civ). Coincident activation of two inputs considerably restored spiking under all these conditions (Fig. 6C).

Paired stimulation has these effects for two reasons. First, by activating two inputs, the BC response is greater just because it has two chances to respond, regardless of the interaction between the two inputs. We refer to this factor as “spike summation,” which is expressed by the relationship Ppredicted = P1 + P2 − P1P2, where P1 and P2 are the firing probabilities of the BC in response to the two inputs stimulated individually. Ppredicted is greater than the individual firing probabilities for any nonzero P1 or P2 (indicated in Fig. 6C as “pred.”). The second factor that contributes to enhanced response is summation of EPSPs. When the pair of inputs were stimulated at the same time, the spike probability increased significantly over and above the predicted value (“pair” vs. “pred.” in Fig. 6C). This extra enhancement reflects the added contribution of EPSP summation.

We also considered the effects of dual stimulation on BC spike latency and jitter. Latency was measured from each stimulus to the immediately following spike. Jitter was measured as the SD in spike time. We found that paired stimulation tended to decrease spike latency and jitter (Fig. 6, D and E). This was true not only for first pulses, but also for later pulses in the train, in control and different concentrations of GABA. Latency and jitter were typically greater in the presence of even low concentrations of GABA (10 μM). These effects are consistent with latency and jitter being influenced by EPSP amplitude (Xu-Friedman and Regehr 2005a,b): as EPSP amplitude decreases (through depression or GABABR activation), latency and jitter increase; when EPSP amplitude increases (through recruitment of two inputs), latency and jitter decrease.

These results indicate a major change in the operation of the endbulb synapse. When the EPSPs are large, such as for initial pulses or during low-frequency activity, they are very effective at driving the BC. Thus to a first approximation, the BC can be thought of as a relay. However, after activation of GABARs, the synapse no longer acts as a relay, but may instead function as a coincidence detector, requiring multiple inputs to elicit significant firing.

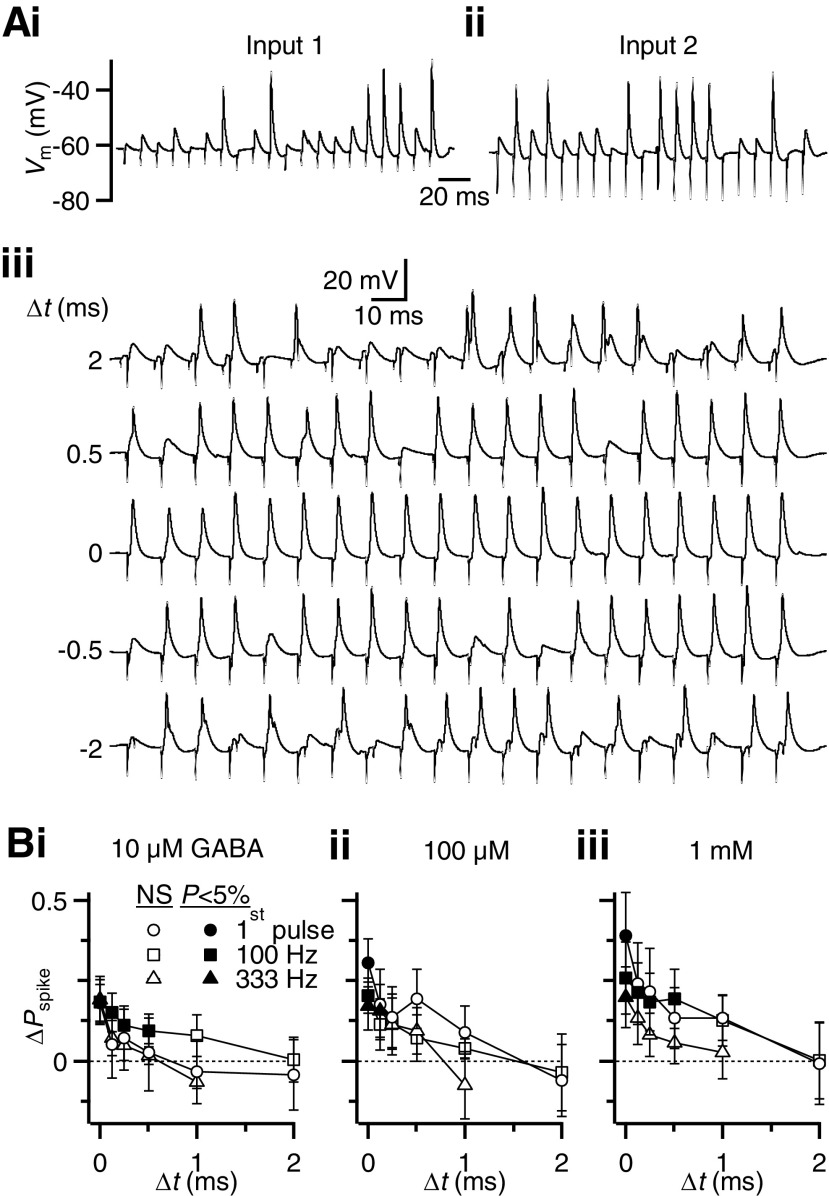

We examined the precision of the BC coincidence detector by activating the two inputs at different time intervals (Δt). During GABA application, there was a low probability of response to stimulation of each input individually (Fig. 7, Ai and Aii). When both were stimulated together, the BC response probability increased at all intervals tested (Fig. 7Aiii), likely as a result of spike summation. The response probability was much greater when the two inputs were stimulated simultaneously (Δt = 0 ms). We quantified the response probability over and above the increase predicted by spike summation. We found that EPSP summation increased the spike probability over very short time windows (Fig. 7B). There was a tendency for the degree of enhancement to increase with higher GABA concentration; however, the time course of EPSP summation did not appear to depend on GABA concentration. Fitting these data to exponential decay functions yielded τ values ranging from 0.16 to 1.25 ms.

Fig. 7.

BC firing in response to 2 inputs requires precise coincidence when GABARs are activated. A: representative responses to stimulation of each input individually (i, ii) and to paired stimulation for different intervals (iii) during bath application of 100 μM GABA. Stimulus artifacts are visible as rapid downward deflections. B: change in BC spike probability (ΔPspike) as a function of the time interval (Δt) between 2 inputs. Values are calculated relative to the predicted Pspike that results from spike summation (see results). Filled symbols indicate Pspike values that are significantly above the value predicted for spike summation. The extent of enhancement appears to increase with GABA concentration, but the τ values of decay do not change significantly. Points are averages of 7 or 8 experiments.

Contribution of different GABARs to BC coincidence detection

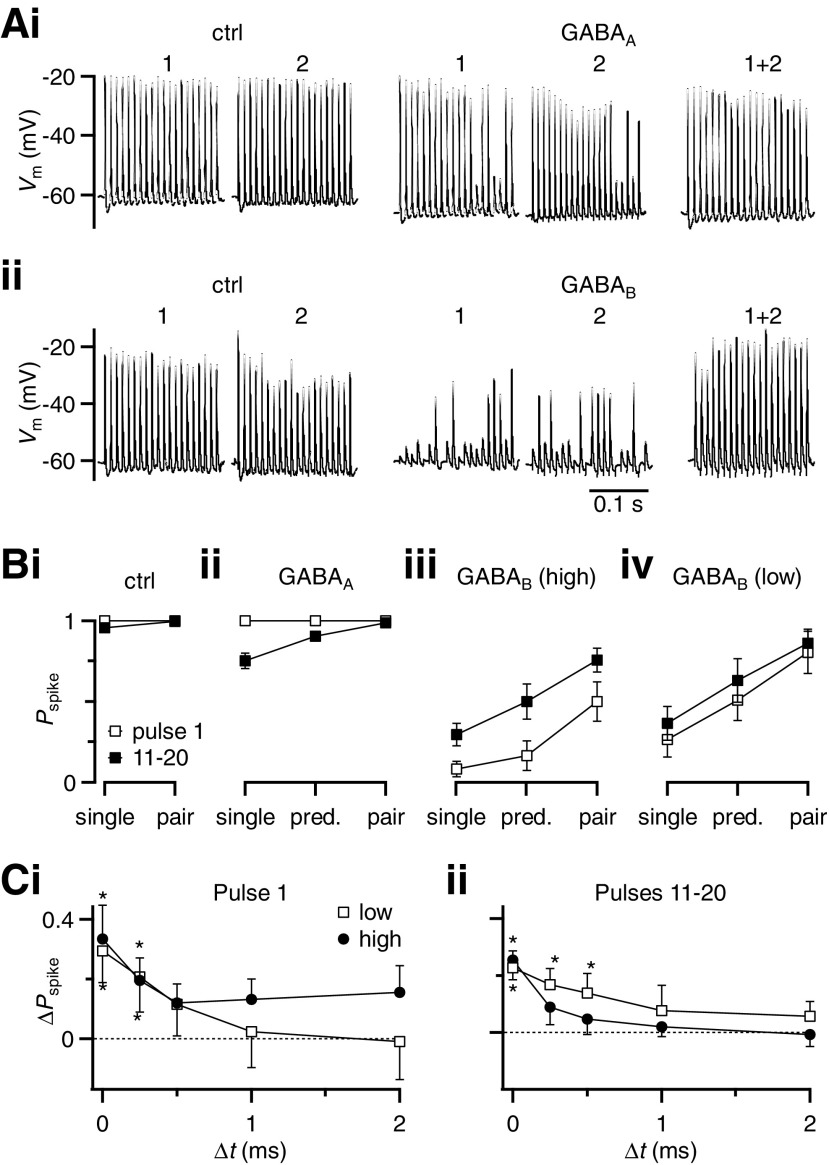

The changes in spike probability seen in Figs. 6 and 7 occurred even at low GABA concentration, suggesting these effects are primarily mediated by GABABRs, which are highly sensitive to GABA (Supplemental Fig. S2). However, the contribution of GABAARs may have been underestimated because bath application of GABA induces receptor desensitization. In addition the high activation of GABABRs in 1 mM GABA may occlude the effects of GABAARs. To clarify the roles of these different receptor types, we examined the contributions of GABAARs and GABABRs in isolation. When GABAARs were activated by puffing 1 mM GABA in the presence of CGP55845, the cell hyperpolarized and the later EPSPs in the train sometimes failed to trigger a spike (Fig. 8Ai, middle panels). When both the inputs were stimulated at the same time, the BC spiked throughout the train (Fig. 8Ai, rightmost panel). The complementary experiment using bath application of baclofen showed that GABABR activation greatly reduced spiking induced by single input activation throughout the train. However, when both inputs were activated simultaneously, spiking was almost completely restored (Fig. 8Aii, rightmost panel).

Fig. 8.

The effects of GABA on coincidence detection are primarily mediated through GABABRs. A: representative traces showing the effects of GABAAR (i) and GABABR (ii) activation on single and paired stimulation in 100-Hz trains. Responses to each individual input in control conditions are shown in the 2 left traces. The next 2 traces show reduced spiking during GABAR activation. The rightmost trace shows that spiking is restored when both inputs are stimulated during GABAR activation. GABAAR activation (i) was done by puffing 1 mM GABA in the presence of CGP55845. GABABR activation (ii) was done by bath application of baclofen. B: average effects of GABAAR (ii) and GABABR (iii, iv) activation for single and paired stimulation on the probability of BC spiking. GABAAR activation (ii) was done by puffing 1 mM GABA in the presence of CGP55845 (6 cells). GABABR activation was done by bath application either of baclofen (iii, “high”; n = 11 cells) or of 10 μM GABA in the presence of bicuculline (iv, “low”; n = 5 cells). Pspike increased significantly from single to paired stimulation under all conditions of GABAR activation (P < 0.02), but not in control. The effects of GABAAR activation are weaker than GABABR activation. C: enhancement of BC spike probability (ΔPspike), for 2 inputs stimulated at different time intervals during GABABR activation. GABABRs were activated using bath application of baclofen (closed circles, “high,” 6 to 11 cells for each point) or 10 μM GABA in the presence of bicuculline (open squares, “low,” 5 cells). ΔPspike is calculated relative to the value predicted for spike summation. Asterisks indicate values significantly different from 0.

We saw similar effects in a number of experiments. For single inputs, GABAAR activation alone had little effect on the first pulse, but later in the train decreased the probability of firing to 75 ± 5% (n = 6, Fig. 8Bii). Spike summation alone would be expected to increase the response during GABAAR activation to 90 ± 2% for later pulses (n = 6, Fig. 8Bii, “predicted”). When the pair of inputs were stimulated at the same time, the spike probability increased to 98 ± 1% (n = 6, Fig. 8Bii, “pair”). The effect of EPSP summation was small for GABAAR activation because the response probability was already high.

Activating GABABRs specifically using baclofen caused a drop in the probability of firing for single inputs and the response was greatly restored by paired stimulation, even above the value predicted with spike summation (Fig. 8Biii). We also evaluated the effects of lower GABABR activation by bath-applying 10 μM GABA in the presence of bicuculline. The probability of spiking for single inputs was strongly reduced by this submaximal activation and there was considerable recovery with paired stimulation, to nearly 100% for the later pulses in the train (Fig. 8Biv). We examined the time course of EPSP summation for low and high activation of GABABRs by evaluating the enhancement above the predicted value for two inputs activated at different intervals. In all cases, there was significant enhancement at short intervals (Fig. 8C). Fitting the data to exponential functions indicated that EPSP summation decayed with τ values of 0.29 to 2.15 ms, indicating that the coincidence window was very narrow.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that neuromodulation through GABARs can change the role of the endbulb synapse. At firing rates of ≤100 Hz under control conditions, the BC acts as a relay, with a high probability of spiking in response to AN fiber stimulation. However, in the presence of GABA, the BC acts as a coincidence detector, with the firing probability significantly elevated by synchronous activity of two inputs. This appears to happen because the input–output relationship of the endbulb synapse is steep and GABABRs modulate the strength of the endbulb just below the point of maximal rise. The greatest enhancement of firing occurs with precisely coincident inputs.

We speculate that this modulation could function to influence hearing in different contexts. For example, if only one input is active, such as during periods of quiet, it may be more useful if the BC reliably relays AN activity for downstream computations, so we might predict low GABABR activation. This would have the disadvantage that spontaneous firing in AN inputs would be relayed to higher centers, even though spontaneous spikes carry little information. Higher GABABR activation could reduce the impact of spontaneous spikes by requiring two coincident inputs. This would most likely be beneficial during louder sounds when at least two inputs are active. In addition, requiring coincident activity from two inputs could improve the precision of timing information conveyed by the BC (Xu-Friedman and Regehr 2005a,b), irrespective of spontaneous activity. The high efficacy of GABABR modulation suggests that this could extend to additional inputs. This would depend on how the activity of endogenous GABAergic inputs changes with sound stimuli. The activity of these descending inputs is not known, but indirect evidence suggests they are tonically activated by sounds (Gai and Carney 2008; Kopp-Scheinpflug et al. 2002).

Properties of the coincidence detector

Two factors contribute to enhanced responses by BCs to two inputs. One we term spike summation, in which the BC has an increased probability of response just by virtue of having two inputs. The relevance of spike summation depends critically on the temporal characteristics of the stimulus: if the BC fails to respond to one AN input, the second input meaningfully makes up for the first only if it is driven by the identical stimulus feature. Salient auditory stimulus features such as tone frequency can be quite rapid, which would reduce the relevance of spike summation.

The second source of enhancement is EPSP summation. The decay of this enhancement was rapid (∼0.5 to 1 ms; Fig. 7B), which is faster than the decay constant of the EPSP (τ = 2.9 ± 0.02 ms, n = 10). In addition, GABAAR activation (which should accelerate the time constant of the cell) had little effect on the coincidence window (Fig. 7). Therefore it seems more likely that the width of the window relates to the steepness of the BC input–output function (Fig. 4E). In this view, a small temporal offset in EPSPs would cause a small change in summated EPSP amplitude, which is amplified as a large change in spike probability.

Endogenous GABA

The functional importance of GABARs in the AVCN is evident from in vivo experiments. Exogenous GABA reduces spontaneous and sound-evoked spiking in BCs (Ebert and Ostwald 1995a,b). Application of GABAAR antagonists causes an increase in sound-evoked firing (Caspary et al. 1994; Gai and Carney 2008; Kopp-Scheinpflug et al. 2002), indicating that GABA is normally present and active in modifying BC responsiveness. These effects in vivo suggest that the vanishingly small GABAAR-mediated IPSCs measured in vitro (Chanda and Xu-Friedman, unpublished observations; Lim et al. 2000) are probably a significant underestimate. This may be because GABAergic fibers do not survive slice preparation well or our stimulation methods do not activate them well. It is also possible that GABAARs do not mediate conventional fast IPSCs, but are expressed extrasynaptically. In any case, it raises the question of what effect GABAARs might have when they are highly activated. To address this, we studied GABAAR activation here using pharmacological approaches.

GABABRs have received somewhat less attention in vivo. Our data suggest that GABABR activation by exogenous agonists may have context-specific effects, depending on the number of active inputs. It seems likely that these receptors would be activated under in vivo conditions because GABABRs are more sensitive than GABAARs to GABA (Figs. 1 and 8 and Supplemental Fig. S2) and there is clear in vivo evidence that GABAARs are normally activated. Our data predict that GABABR activation will have effects in vivo. One might expect GABABR antagonists to produce increases in BC firing and there may also be more subtle effects on the precision of spike timing.

GABA could be released in the AVCN by a number of descending projections. Two nuclei in the superior olivary complex, the superior paraolivary nucleus and the ventral nucleus of the trapezoid body, project to the cochlear nucleus and have a high proportion of GABAergic neurons (Benson and Potashner 1990; Kulesza and Berrebi 2000; Ostapoff et al. 1997). Second, glycinergic inputs from tuberculoventral neurons in the deep cerebellar nuclei (DCN) (Zhang and Oertel 1993) can corelease GABA, which can induce homosynaptic modulation during bouts of high activity (Lim et al. 2000). Third, there are descending inputs from the cortex (Schofield and Coomes 2005) and cortical activation influences the responses of neurons in the cochlear nucleus (Luo et al. 2008), although the nature of these inputs is not well known. It will be important to evaluate how each of these different sources is activated during sounds and whether these sources activate the receptors we have studied here.

To understand how these sources might influence endbulb function, additional approaches will be needed to activate different sources reliably and in isolation, such as previously done with glycinergic inputs from DCN (Wickesberg and Oertel 1990). This will allow study of the source of GABAAR versus GABABR activation, the temporal relationship between activity in descending inputs and GABABR modulation, and the relative importance of synaptic and extrasynaptic receptors. Furthermore, that will allow an exploration of the relative contributions of GABA and glycine components of different populations of inhibitory inputs. Glycine clearly plays an important role in fast inhibitory neurotransmission and it could have effects similar to the effects of GABAARs observed here.

Relevance to other synapses

Our data differ from earlier findings in that baclofen did not induce an increase in EPSC amplitude late in high-frequency trains, as was found in the chick endbulb (Brenowitz and Trussell 2001b; Brenowitz et al. 1998). We found this difference even when GABABRs were maximally activated by 100 μM baclofen or 1 mM GABA. The paradoxical enhancement seems to depend on desensitization (Brenowitz and Trussell 2001a), which is also present at the mammalian endbulb (Chanda and Xu-Friedman 2010; Isaacson and Walmsley 1995; Yang and Xu-Friedman 2008). It is possible that desensitization could play a larger role in the chick, such as if the initial probability of release is greater or recovery from desensitization is slower.

It will be interesting to see how the results found here may generalize to other synapses. The switch between relay and coincidence-detector modes requires that individual inputs be large under control conditions and that modulation significantly suppress that response. The effectiveness of coincidence also seems to be enhanced by a steep input–output relationship. These factors are likely to be synapse-specific, but could extend to nonglutamatergic synapses under the influence of any neuromodulator.

In addition, other mechanisms besides neuromodulation could lead to sharpening of temporal dependence. One simple mechanism is to reduce the integration window of a cell, such as by recruiting GABAARs (Pouille and Scanziani 2001). The integration window of BCs does not appear to be greatly influenced by GABAAR activation (Fig. 7). One key feature we observed was that GABABR activation modulated the synapse to just below its dynamic range, which can also happen through short-term synaptic plasticity such as depression. Depression during high rates of AN activity also led to the BC acting like a coincidence detector (Fig. 6Ci). Interestingly, high firing rates would tend to occur in vivo during high-intensity sounds (Sachs and Abbas 1974), which are also the stimulus conditions that would favor activating multiple inputs. Thus synaptic depression could similarly convert the synapse from a relay to a coincidence detector under appropriate stimulus conditions. It has been suggested that depression could improve the precision of coincidence detection in the nucleus laminaris of the chick (Cook et al. 2003; Kuba et al. 2002). Since depression relies on previous activity, this may cause shifts in the coincidence properties of a cell between the onset and steady-state phases of a sound. This differs from GABABR activation, in which onset and steady-state parts of trains of all firing rates are similarly affected (Figs. 6C and 8C).

The mechanism that we describe could be relevant to binaural coincidence detection, such as occurs in the medial superior olive of mammals and nucleus laminaris of birds. One feature of this coincidence detector is that the response to noncoincident inputs is lower than that to monaural input (Carr and Konishi 1990; Goldberg and Brown 1969; Yin and Chan 1990). To explain this, most attention has focused on the role of postsynaptic properties, such as sodium channel inactivation and potassium channel activation (Agmon-Snir et al. 1998; Reyes et al. 1996; Svirskis et al. 2004). Our results suggest that an analogous phenomenon could occur in the monaural AVCN through a presynaptic mechanism. That is, the response to a single input could be suppressed by GABAR activation while allowing significantly greater responses to multiple inputs. This would imply the existence of a feedback mechanism, which may provide greater flexibility under different contexts.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant R01 DC-008125 to M. A. Xu-Friedman.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank L. Pliss, J. Trimper, H. Yang, and S. R. Oh for help during the project and for comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental data.

REFERENCES

- Adams and Mugnaini, 1987. Adams JC, Mugnaini E. Patterns of glutamate decarboxylase immunostaining in the feline cochlear nuclear complex studied with silver enhancement and electron microscopy. J Comp Neurol 262: 375–401, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agmon-Snir et al., 1998. Agmon-Snir H, Carr CE, Rinzel J. The role of dendrites in auditory coincidence detection. Nature 393: 268–272, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean, 1989. Bean BP. Neurotransmitter inhibition of neuronal calcium currents by changes in channel voltage dependence. Nature 340: 153–156, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellingham and Walmsley, 1999. Bellingham MC, Walmsley B. A novel presynaptic inhibitory mechanism underlies paired pulse depression at a fast central synapse. Neuron 23: 159–170, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson and Potashner, 1990. Benson CG, Potashner SJ. Retrograde transport of [3H]glycine from the cochlear nucleus to the superior olive in the guinea pig. J Comp Neurol 296: 415–426, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawer and Morest, 1975. Brawer JR, Morest DK. Relations between auditory nerve endings and cell types in the cat's anteroventral cochlear nucleus seen with the Golgi method and Nomarski optics. J Comp Neurol 160: 491–506, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenowitz et al., 1998. Brenowitz S, David J, Trussell L. Enhancement of synaptic efficacy by presynaptic GABA(B) receptors. Neuron 20: 135–141, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenowitz and Trussell, 2001a. Brenowitz S, Trussell LO. Maturation of synaptic transmission at end-bulb synapses of the cochlear nucleus. J Neurosci 21: 9487–9498, 2001a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenowitz and Trussell, 2001b. Brenowitz S, Trussell LO. Minimizing synaptic depression by control of release probability. J Neurosci 21: 1857–1867, 2001b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell, 1975. Brownell WE. Organization of the cat trapezoid body and the discharge characteristics of its fibers. Brain Res 94: 413–433, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkitt and Clark, 1999. Burkitt AN, Clark GM. Analysis of integrate-and-fire neurons: synchronization of synaptic input and spike output. Neural Comput 11: 871–901, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cant and Casseday, 1986. Cant NB, Casseday JH. Projections from the anteroventral cochlear nucleus to the lateral and medial superior olivary nuclei. J Comp Neurol 247: 457–476, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao et al., 2007. Cao XJ, Shatadal S, Oertel D. Voltage-sensitive conductances of bushy cells of the Mammalian ventral cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 97: 3961–3975, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr and Konishi, 1990. Carr CE, Konishi M. A circuit for detection of interaural time differences in the brain stem of the barn owl. J Neurosci 10: 3227–3246, 1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspary et al., 1994. Caspary DM, Backoff PM, Finlayson PG, Palombi PS. Inhibitory inputs modulate discharge rate within frequency receptive fields of anteroventral cochlear nucleus neurons. J Neurophysiol 72: 2124–2133, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanda and Xu-Friedman, 2010. Chanda S, Xu-Friedman MA. A low-affinity antagonist reveals saturation and desensitization in mature synapses in the auditory brain stem. J Neurophysiol 103: 1915–1926, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook et al., 2003. Cook DL, Schwindt PC, Grande LA, Spain WJ. Synaptic depression in the localization of sound. Nature 421: 66–70, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert and Ostwald, 1995a. Ebert U, Ostwald J. GABA alters the discharge pattern of chopper neurons in the rat ventral cochlear nucleus. Hear Res 91: 160–166, 1995a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert and Ostwald, 1995b. Ebert U, Ostwald J. GABA can improve acoustic contrast in the rat ventral cochlear nucleus. Exp Brain Res 104: 310–322, 1995b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiala, 2005. Fiala JC. Reconstruct: a free editor for serial section microscopy. J Microsc 218: 52–61, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gai and Carney, 2008. Gai Y, Carney LH. Influence of inhibitory inputs on rate and timing of responses in the anteroventral cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 99: 1077–1095, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg and Brown, 1969. Goldberg JM, Brown PB. Response of binaural neurons of dog superior olivary complex to dichotic tonal stimuli: some physiological mechanisms of sound localization. J Neurophysiol 32: 613–636, 1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson and Walmsley, 1995. Isaacson JS, Walmsley B. Receptors underlying excitatory synaptic transmission in slices of the rat anteroventral cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 73: 964–973, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joris et al., 1994. Joris PX, Carney LH, Smith PH, Yin TC. Enhancement of neural synchronization in the anteroventral cochlear nucleus. I. Responses to tones at the characteristic frequency. J Neurophysiol 71: 1022–1036, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juiz et al., 1996. Juiz JM, Helfert RH, Bonneau JM, Wenthold RJ, Altschuler RA. Three classes of inhibitory amino acid terminals in the cochlear nucleus of the guinea pig. J Comp Neurol 373: 11–26, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp-Scheinpflug et al., 2002. Kopp-Scheinpflug C, Dehmel S, Dorrscheidt GJ, Rubsamen R. Interaction of excitation and inhibition in anteroventral cochlear nucleus neurons that receive large endbulb synaptic endings. J Neurosci 22: 11004–11018, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuba et al., 2002. Kuba H, Koyano K, Ohmori H. Synaptic depression improves coincidence detection in the nucleus laminaris in brainstem slices of the chick embryo. Eur J Neurosci 15: 984–990, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulesza and Berrebi, 2000. Kulesza RJ, Jr, Berrebi AS. Superior paraolivary nucleus of the rat is a GABAergic nucleus. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 1: 255–269, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim et al., 2000. Lim R, Alvarez FJ, Walmsley B. GABA mediates presynaptic inhibition at glycinergic synapses in a rat auditory brainstem nucleus. J Physiol 525: 447–459, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu and Trussell, 2001. Lu T, Trussell LO. Mixed excitatory and inhibitory GABA-mediated transmission in chick cochlear nucleus. J Physiol 535: 125–131, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo et al., 2008. Luo F, Wang Q, Kashani A, Yan J. Corticofugal modulation of initial sound processing in the brain. J Neurosci 28: 11615–11621, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahendrasingam et al., 2000. Mahendrasingam S, Wallam CA, Hackney CM. An immunogold investigation of the relationship between the amino acids GABA and glycine and their transporters in terminals in the guinea-pig anteroventral cochlear nucleus. Brain Res 887: 477–481, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milenkovic et al., 2007. Milenkovic I, Witte M, Turecek R, Heinrich M, Reinert T, Rubsamen R. Development of chloride-mediated inhibition in neurons of the anteroventral cochlear nucleus of gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus). J Neurophysiol 98: 1634–1644, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicol and Walmsley, 2002. Nicol MJ, Walmsley B. Ultrastructural basis of synaptic transmission between endbulbs of Held and bushy cells in the rat cochlear nucleus. J Physiol 539: 713–723, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel, 1983. Oertel D. Synaptic responses and electrical properties of cells in brain slices of the mouse anteroventral cochlear nucleus. J Neurosci 3: 2043–2053, 1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel, 1985. Oertel D. Use of brain slices in the study of the auditory system: spatial and temporal summation of synaptic inputs in cells in the anteroventral cochlear nucleus of the mouse. J Acoust Soc Am 78: 328–333, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostapoff et al., 1997. Ostapoff EM, Benson CG, Saint Marie RL. GABA- and glycine-immunoreactive projections from the superior olivary complex to the cochlear nucleus in guinea pig. J Comp Neurol 381: 500–512, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouille and Scanziani, 2001. Pouille F, Scanziani M. Enforcement of temporal fidelity in pyramidal cells by somatic feed-forward inhibition. Science 293: 1159–1163, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes et al., 1996. Reyes AD, Rubel EW, Spain WJ. In vitro analysis of optimal stimuli for phase-locking and time-delayed modulation of firing in avian nucleus laminaris neurons. J Neurosci 16: 993–1007, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhode and Greenberg, 1994. Rhode WS, Greenberg S. Lateral suppression and inhibition in the cochlear nucleus of the cat. J Neurophysiol 71: 493–514, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman et al., 1993. Rothman JS, Young ED, Manis PB. Convergence of auditory nerve fibers onto bushy cells in the ventral cochlear nucleus: implications of a computational model. J Neurophysiol 70: 2562–2583, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryugo and Fekete, 1982. Ryugo DK, Fekete DM. Morphology of primary axosomatic endings in the anteroventral cochlear nucleus of the cat: a study of the endbulbs of Held. J Comp Neurol 210: 239–257, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs and Abbas, 1974. Sachs MB, Abbas PJ. Rate versus level functions for auditory-nerve fibers in cats: tone-burst stimuli. J Acoust Soc Am 56: 1835–1847, 1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Marie et al., 1989. Saint Marie RL, Morest DK, Brandon CJ. The form and distribution of GABAergic synapses on the principal cell types of the ventral cochlear nucleus of the cat. Hear Res 42: 97–112, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield and Coomes, 2005. Schofield BR, Coomes DL. Auditory cortical projections to the cochlear nucleus in guinea pigs. Hear Res 199: 89–102, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith et al., 1991. Smith PH, Joris PX, Carney LH, Yin TC. Projections of physiologically characterized globular bushy cell axons from the cochlear nucleus of the cat. J Comp Neurol 304: 387–407, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith et al., 1993. Smith PH, Joris PX, Yin TC. Projections of physiologically characterized spherical bushy cell axons from the cochlear nucleus of the cat: evidence for delay lines to the medial superior olive. J Comp Neurol 331: 245–260, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirou et al., 1990. Spirou GA, Brownell WE, Zidanic M. Recordings from cat trapezoid body and HRP labeling of globular bushy cell axons. J Neurophysiol 63: 1169–1190, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirou et al., 2005. Spirou GA, Rager J, Manis PB. Convergence of auditory-nerve fiber projections onto globular bushy cells. Neuroscience 136: 843–863, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svirskis et al., 2004. Svirskis G, Kotak V, Sanes DH, Rinzel J. Sodium along with low-threshold potassium currents enhance coincidence detection of subthreshold noisy signals in MSO neurons. J Neurophysiol 91: 2465–2473, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang and Manis, 2008. Wang Y, Manis PB. Short-term synaptic depression and recovery at the mature mammalian endbulb of Held synapse in mice. J Neurophysiol 100: 1255–1264, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickesberg and Oertel, 1990. Wickesberg RE, Oertel D. Delayed, frequency-specific inhibition in the cochlear nuclei of mice: a mechanism for monaural echo suppression. J Neurosci 10: 1762–1768, 1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter and Palmer, 1991. Winter IM, Palmer AR. Intensity coding in low-frequency auditory-nerve fibers of the guinea pig. J Acoust Soc Am 90: 1958–1967, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu and Oertel, 1986. Wu SH, Oertel D. Inhibitory circuitry in the ventral cochlear nucleus is probably mediated by glycine. J Neurosci 6: 2691–2706, 1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu-Friedman and Regehr, 2005a. Xu-Friedman MA, Regehr WG. Dynamic-clamp analysis of the effects of convergence on spike timing. I. Many synaptic inputs. J Neurophysiol 94: 2512–2525, 2005a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu-Friedman and Regehr, 2005b. Xu-Friedman MA, Regehr WG. Dynamic-clamp analysis of the effects of convergence on spike timing. II. Few synaptic inputs. J Neurophysiol 94: 2526–2534, 2005b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi et al., 2000. Yamauchi T, Hori T, Takahashi T. Presynaptic inhibition by muscimol through GABAB receptors. Eur J Neurosci 12: 3433–3436, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang and Xu-Friedman, 2008. Yang H, Xu-Friedman MA. Relative roles of different mechanisms of depression at the mouse endbulb of Held. J Neurophysiol 99: 2510–2521, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang and Xu-Friedman, 2009. Yang H, Xu-Friedman MA. Impact of synaptic depression on spike timing at the endbulb of Held. J Neurophysiol 102: 1699–1710, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin and Chan, 1990. Yin TC, Chan JC. Interaural time sensitivity in medial superior olive of cat. J Neurophysiol 64: 465–488, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang and Oertel, 1993. Zhang S, Oertel D. Tuberculoventral cells of the dorsal cochlear nucleus of mice: intracellular recordings in slices. J Neurophysiol 69: 1409–1421, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang and Trussell, 1994. Zhang S, Trussell LO. Voltage clamp analysis of excitatory synaptic transmission in the avian nucleus magnocellularis. J Physiol 480: 123–136, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.