Abstract

Helicobacter pylori is the dominant species of the human gastric microbiome, and colonization causes a persistent inflammatory response. H. pylori-induced gastritis is the strongest singular risk factor for cancers of the stomach; however, only a small proportion of infected individuals develop malignancy. Carcinogenic risk is modified by strain-specific bacterial components, host responses and/or specific host–microbe interactions. Delineation of bacterial and host mediators that augment gastric cancer risk has profound ramifications for both physicians and biomedical researchers as such findings will not only focus the prevention approaches that target H. pylori-infected human populations at increased risk for stomach cancer but will also provide mechanistic insights into inflammatory carcinomas that develop beyond the gastric niche.

Gastric adenocarcinoma is the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the world. Approximately 700,000 people succumb to this malignancy each year and 5-year survival rates in the United States are <15%1. Two histologically distinct variants of gastric adeno-carcinoma have been described, each with different pathophysiological features. Diffuse-type gastric adeno-carcinoma more commonly affects younger people and consists of individually infiltrating neoplastic cells that do not form glandular structures. The more prevalent form of gastric adenocarcinoma, intestinal-type adeno-carcinoma, progresses through a series of histological steps that are initiated by the transition from normal mucosa to chronic superficial gastritis, which then leads to atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia, and finally to dysplasia and adenocarcinoma2. Helicobacter pylori is a microbial species that specifically colonizes gastric epithelium and it is the most common bacterial infection worldwide. Everyone infected by this organism develops coexisting gastritis, which typically persists for decades, coupling H. pylori and its human host into a dynamic and prolonged equilibrium. However, there are biological costs incurred by such long-term relationships.

H. pylori infection is the strongest known risk factor for malignancies that arise within the stomach, and epidemio-logical studies have determined that the attributable risk for gastric cancer conferred by H. pylori is approximately 75%3. Although H. pylori significantly increases the risk of developing both diffuse-type and intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinoma, chronic inflammation is not required for the development of diffuse-type cancers, suggesting that mechanisms underpinning the ability of H. pylori to induce malignancy are different for these cancer subtypes. Eradication of H. pylori significantly decreases the risk of developing cancer in infected individuals without pre-malignant lesions4, reinforcing the tenet that this organism influences early stages in gastric carcinogenesis. However, only a small proportion of colonized people ever develop neoplasia, and disease risk involves well-choreographed interactions between pathogen and host, which are in turn dependent on strain-specific bacterial factors and/or host genotypic traits. These observations, in conjunction with recent evidence that the carriage of certain strains is inversely related to oesophageal adenocarcinoma and atopic diseases1,5 (BOX 1), underscore the importance and timeliness of reviewing mechanisms that regulate the biological interactions of H. pylori with its hosts and that promote carcinogenesis.

Chronic superficial gastritis

An early step in the histological cascade proceeding from normal gastric mucosa to intestinal-type gastric cancer. Characterized by the infiltration of the gastric lamina propria with mononuclear and polymorphonuclear inflammatory cells.

Atrophic gastritis

An intermediate histological step in the progression to intestinal-type gastric adenocarcinoma. Characterized by variable gland loss and the encroachment of inflammatory cells into the glandular zones.

H. pylori constituents that mediate oncogenesis

H. pylori strains are extremely diverse, freely recombining as panmictic populations. Genetic variability is generated through intra-genomic diversification (for example, point mutations, recombination and slipped-strand mis-pairing) as well as inter-genomic recombination6. The use of broad-range 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) PCR coupled with high-throughput sequencing has demonstrated that H. pylori does not exist simply as a monoculture within the human stomach but is instead a resident of a distinct gastric microbial ecosystem7. Although H. pylori is the dominant species, the presence of other microorganisms provides a genetic repository, which facilitates the generation of new traits that may influence gastric carcinogenesis.

At a glance.

Infection with Helicobacter pylori is the strongest known risk factor for gastric adenocarcinoma, but only a minority of colonized individuals develop cancer of the stomach.

H. pylori strains exhibit extensive genetic diversity and strain-specific proteins augment the risk for malignancy.

β-catenin signalling has an important role in conjunction with other oncogenic pathways in the regulation of host responses to H. pylori that have carcinogenic potential.

Transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor may help us understand the epithelial signalling pathways that mediate H. pylori-induced carcinogenesis.

Chronic inflammation can induce aberrant β-catenin activation in the context of H. pylori infection.

A mechanistic understanding of H. pylori activation of oncogenic signalling may lead to key insights into malignancies that arise from inflammatory foci in other organ systems.

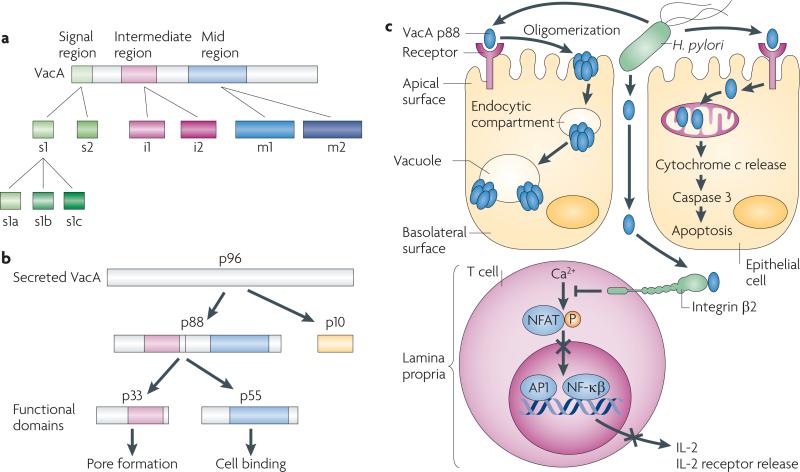

The H. pylori vacuolating cytotoxin

The H. pylori gene vacA encodes a secreted protein (VacA) that was initially identified on the basis of its ability to induce vacuolation in cultured epithelial cells. VacA-induced vacuoles are hybrid compartments of late endosomal origin that depend on the presence of several cellular factors, such as v-ATPase and the GTPases RAB7, RAC1 and dynamin. However, VacA also exerts other effects on host cells, and vacA is a specific locus linked with gastric malignancy. All strains contain vacA, but there is marked variation in vacA sequences among strains with the regions of greatest diversity localized to the 5′ signal terminus (allele types s1a, s1b, s1c and s2), the mid-region (allele types m1 and m2) and the intermediate region (allele types i1 and i2)8 (FIG. 1a). Each vacA gene contains a single signal, mid-region and intermediate region allele, and vacA sequence diversity corresponds to variations in vacuolating activity.

Figure 1. Helicobacter pylori VacA structure and functional effects.

a | vacA is a polymorphic mosaic gene that arose through homologous recombination. Regions of sequence diversity are localized to the signal (s), intermediate (i) and mid (m) region. The s1 signal region is fully active, but the s2 region encodes a protein with a different signal peptide cleavage site, resulting in a short amino-terminal extension that inhibits vacuolation. The mid region encodes a cell-binding site, but the m2 allele is attenuated in its ability to induce vacuolation. The function of the i region is undefined. b | VacA is secreted as a 96 kDa protein, which is rapidly cleaved into a 10 kDa passenger domain (p10) and an 88 kDa mature protein (p88). The p88 fragment contains two domains, designated p33 and p55, which are VacA functional domains. c | The secreted monomeric form of VacA p88 binds to epithelial cells nonspecifically and through specific receptor binding. Following binding, VacA monomers form oligomers, which are then internalized by a pinocytic-like mechanism and form anion-selective channels in endosomal membranes; vacuoles arise owing to the swelling of endosomal compartments. The biological consequences of vacuolation are currently undefined, but VacA also induces other effects, such as apoptosis, partly by forming pores in mitochondrial membranes, allowing cytochrome c release. VacA has also been identified in the lamina propria, and probably enters by traversing epithelial paracellular spaces, where it can interact with integrin β2 on T cells and inhibit the transcription factor nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), leading to the inhibition of interleukin-2 (IL-2) secretion and blockade of T cell activation and proliferation. AP1, activator protein 1; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; P, phosphorylation.

VacA is secreted and undergoes proteolysis to yield two fragments, p33 and p55 (REF. 9), which are VacA functional domains (FIG. 1b). The p33 domain contains a hydrophobic sequence that is involved in pore formation, whereas the p55 fragment contains cell-binding domains. Full-length VacA binds multiple epithelial cell-surface components, including the transmembrane protein receptor-type tyrosine protein phosphatase-ζ (PTPRZ1)10, fibronectin11, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)12, various lipids13 and sphingomyelin14, as well as CD18 (integrin β2) on T cells15.

VacA not only induces vacuolation but also stimulates apoptosis in gastric epithelial cells16 (FIG. 1c). Transient expression of p33 or full-length VacA induces cyto-chrome c release from mitochondria, leading to the activation of caspase 3, and VacA proteins that contain an s1 signal allele induce higher levels of apoptosis than VacA proteins that contain an s2 allele or VacA mutants lacking the hydrophobic amino terminus region9. VacA also exerts effects on the host immune response that permit long-term colonization with an inherent increased risk of transformation. VacA binding to integrin β2 blocks antigen-dependent proliferation of transformed T cells by interfering with interleukin-2 (IL-2)-mediated signalling through the inhibition of Ca2+ mobilization and downregulation of the Ca2+-dependent phosphatase calcineurin17 (FIG. 1c). This in turn inhibits the activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) and its target genes IL2 and the high-affinity IL-2 receptor-α (IL2RA). VacA exerts effects on primary human CD4+ T cells that are different from its effects on transformed T cell lines by suppressing IL-2-induced cell cycle progression and proliferation in an NFAT-independent manner18. Collectively, these observations suggest that VacA inhibits the expansion of T cells that are activated by bacterial antigens, thereby allowing H. pylori to evade the adaptive immune response.

Most of the evidence linking VacA production to gastric cancer has been derived from epidemiological investigations. H. pylori strains that express forms of VacA that are active in vitro are associated with a higher risk of gastric cancer than the strains that express inactive forms of VacA8,19–22. This relationship is consistent with studies that have examined the distribution of vacA genotypes throughout the world. In regions in which the background rate of distal gastric cancer is high, such as Colombia and japan, most H. pylori strains contain vacA s1 and m1 alleles23. By contrast, animal studies have yielded mixed results, as some investigations indicate that VacA enhances the ability of H. pylori to colonize and induce damage in the stomach, although others have not demonstrated such an effect10,24,25. However, there are limitations to using animal model systems for evaluating the effects of VacA; for example, human T cells are susceptible to the effects of VacA but murine T cells are not15,26. Similar to VacA, strains that express the outer membrane protein BabA (as discussed below) are associated with a higher risk of gastric cancer than the strains that lack this factor19. On the basis of data from epidemiological studies alone, however, it is difficult to determine which of these bacterial factors is most closely linked to adverse disease outcomes, as these virulence constituents tend to cluster together in H. pylori strains19.

Attributable risk

The risk for a particular condition or disease that is defined by differences in the rates of that condition or disease between an exposed group and an unexposed group.

Panmictic population

A microbial population that is not clonal but is characterized by extensive recombination and genetic diversity.

Adaptive immune response

Also known as specific or acquired immunity. It is mediated by antigen-specific lymphocytes and antibodies, is highly antigen-specific and includes the development of immunological memory.

Lewis histo-blood-group antigen

A fucosylated antigen that is expressed on erythrocytes as well as in other body compartments, including the gastric epithelium.

Outer membrane proteins

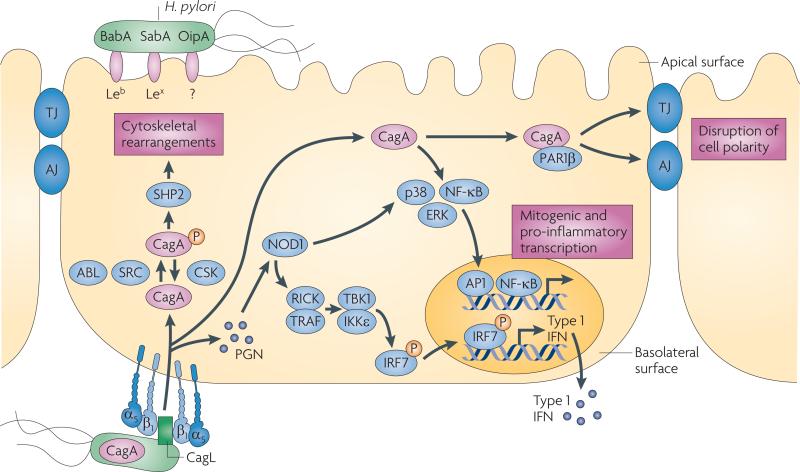

Although most H. pylori reside within the semi-permeable mucous gel layer of the stomach blanketing the apical surface of the gastric epithelium, approximately 20% bind to gastric epithelial cells. Genome analysis from completely sequenced H. pylori strains has revealed that an unusually high proportion of identified open reading frames encode proteins that reside in the outer, as well as the inner, membrane of the bacterium (known as outer membrane proteins (OMPs))27–30. Consistent with genomic studies, H. pylori strains express multiple paralogous OMPs, several of which bind to defined receptors on gastric epithelial cells, and strains differ in both expression and binding properties of certain OMPs (FIG. 2).

Figure 2. Interactions between pathogenic H. pylori and gastric epithelial cells.

Several adhesins such as BabA, SabA and OipA mediate binding of Helicobacter pylori to gastric epithelial cells, probably through the apical surface. H. pylori can also bind to α5β1 integrins, which are located on the basolateral surface of epithelial cells. After adherence, H. pylori can translocate effector molecules such as CagA and peptidoglycan (PGN) into the host cell. PGN is sensed by the intracellular receptor nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 1 (NOD1), which activates nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), p38, ERK and IRF7 to induce the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Translocated CagA is rapidly phosphorylated (P) by SRC and ABL kinases, leading to cytoskeletal rearrangements. Unphosphorylated CagA can trigger several different signalling cascades, including the activation of NF-κB and the disruption of cell–cell junctions, which may contribute to the loss of epithelial barrier function. Injection of CagA seems to be dependent on basolateral integrin α5β1. AJ, adherens junction; CSK, c-src tyrosine kinase; IFN, interferon; IKKε, IκB kinase-ε; IRF7, interferon regulatory factor 7; RICK, receptor-interacting serine-threonine kinase 2; TBK1, TANK-binding kinase 1; TJ, tight junction.

BabA, a member of a family of highly conserved OMPs, and encoded by the strain-specific gene babA2, is an adhesin that binds the Lewis histo-blood-group antigen Leb (also known as MUC5AC) on gastric epithelial cells19,31,32; H. pylori babA2+ strains are associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer19. SabA is an H. pylori adhesin that binds the sialyl-lewisx (Lex; also known as FUT4) antigen, which is an established tumour antigen and a marker of gastric dysplasia that is upregulated by chronic gastric inflammation33. Exploitation of host lewis antigens is further evidenced by data demonstrating that the O-antigen of H. pylori lipopolysaccharide (LPS) contains various human lewis antigens, including Lex, Ley (also known as FUT3), Lea and Leb; and the inactivation of Lex- and Ley-encoding genes prevents H. pylori from colonizing mice34. Approximately 85% of H. pylori clinical isolates express Lex and Ley, and although both can be detected on individual strains one antigen usually predominates35. H. pylori lewis antigens can undergo phase variation in vitro35,36, and in vivo studies using Rhesus monkeys or mice have demonstrated that the Lewis antigen expression pattern of colonizing bacteria is directly altered in response to the expression pattern of their cognate host37,38. In Leb-expressing transgenic or wild-type control mice challenged with an H. pylori strain that expressed Lex and Ley, only bacterial populations recovered from Leb-positive mice expressed Leb, and this was mediated by a putative galactosyltransferase gene (β-(1,3)galT)38. This suggests that Lewis antigens facilitate molecular mimicry and allow H. pylori to escape host immune defenses by preventing the formation of antibodies against shared bacterial and host epitopes.

OipA is another differentially expressed OMP that has been linked to disease outcome39. Expression of OipA is regulated by slipped strand mispairing within a CT-rich dinucleotide repeat region located in the 5′ terminus of the gene. Several reports have demonstrated that OipA co-regulates the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-8, IL-6 and RANTES (also known as CCL5), as well as other effector proteins that may have a role in pathogenesis, such as matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP1; also known as interstitial collagenase)40–44. However, other studies have not demonstrated an effect of OipA on cytokine production45–48, which may be due to different H. pylori strains possessing in-frame versus out-of-frame oipA sequences or to differences in experimental conditions. Interestingly, OipA has now been shown to mediate the adherence of H. pylori to gastric epithelial cells and trigger β-catenin activation48,49. Collectively, these observations underscore the pivotal role of direct contact between H. pylori and epithelial cells in the induction of chronic inflammation and injury.

Phase variation

The alteration of bacterial surface proteins (for example, outer membrane proteins, flagella and lipopolysaccharide) to evade the host immune system.

Pilus

Projection from the bacterial cell surface that allows bacteria to attach to other cells to facilitate the transfer of proteins or genetic material.

Box 1 | Reciprocity between H. pylori and oesophageal and allergic diseases.

The decline in Helicobacter pylori acquisition during the past century in the United States has been mirrored by an expected decrease in distal gastric cancer, but these changes have been opposed by a rapidly increasing incidence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and its sequelae, Barrett's oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma1. This reciprocal effect is almost entirely attributable to cag+ strains, and the location of inflammation in the stomach seems to be crucial. Patients with gastritis that primarily affects the distal stomach, with sparing of the acid-secreting gastric body, have increased gastric acidity, and acid secretion rates are attenuated in infected subjects with gastritis that affects the body of the stomach, which houses acid-producing parietal cells. By inhibiting parietal cell function and/or accelerating the development of gastric atrophy, in which parietal cells are lost, more severe gastric body inflammation that is induced by cag+ strains may blunt the levels of acid secretion required for the development of GERD and its sequelae.

In addition to oesophageal diseases, there have also been increases in the prevalence of allergic diseases in industrialized nations5. Significant inverse relationships are present between the prevalence of H. pylori and asthma, atopy, allergic rhinitis and eczema5, and these reciprocal relationships are most pronounced in young people infected with cag+ strains. Low acid conditions may partially explain these inverse relationships as a substantial proportion of asthma cases in adults are due to GERD. However, H. pylori also aberrantly activates T regulatory cells137, which in turn may dampen immunomodulatory activities against environmental allergens.

Therefore, the interactions of H. pylori cag+ strains with their hosts confer opposing risks for important diseases, underscoring the clinical relevance of identifying specific strains with which individuals are colonized so that their risks for different pathological outcomes can be more correctly identified.

The H. pylori type IV cag secretion system

Another H. pylori strain-specific determinant that influences pathogenesis is the cag pathogenicity island, and cag+ strains significantly augment the risk for distal gastric cancer compared with cag– strains1. Genes within the cag island encode proteins that form a prototypic type IV bacterial secretion system (T4SS) that exports microbial proteins. The product of the terminal gene in the island (CagA) is translocated into and phosphorylated within host epithelial cells following bacterial attachment50 (FIG. 2). Transgenic expression of CagA in mice leads to gastric epithelial cell proliferation and carcinoma development, and CagA attenuates apoptosis in vitro and in vivo — implicating this molecule as a bacterial oncoprotein51,52. Recent evidence suggests that the H. pylori genome might also contain another T4SS, although the relationships between non-cag T4SS and disease remain to be clearly established. For example, duodenal ulcer-promoting gene A (dupA) is an H. pylori gene that has homology to virB4 (a component of bacterial T4SS required for energy-dependent delivery of substrates from the bacterial cytoplasm to host cells), suggesting that it may function as an ATPase within an as yet undefined T4SS53. Some studies have suggested a positive association between the presence of dupA and duodenal ulceration, but a negative association with gastric cancer53–55; however, other investigations have shown no associations between the presence of dupA and disease56–60.

Integrin receptors on host cells represent a portal of entry for CagA injection61, and CagL (FIG. 2), a T4SS-pilus-localized protein, has an important role. CagL bridges the T4SS to integrin α5β1 on target cells and activates the host cell kinases focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and SRC to ensure that CagA is directly phosphorylated at its site of injection. In addition to integrin α5β1 (REF. 61), CagL can also bind integrin αvβ5 and fibronectin, although the downstream consequences of binding to these receptors remain undefined. Recently, additional cag proteins (CagA, CagI and CagY) have been shown to bind integrin β1 and induce conformational changes of integrin heterodimers, which permits CagA translocation62. Integrins are not found at the apical membrane but are present at the basolateral membrane (FIG. 2), indicating that H. pylori may inject effector proteins into target cells only at specific sites, such as the basolateral surface of polarized epithelial cells. This is consistent with recent observations that viable H. pylori are present within paracellular spaces and the gastric lamina propria63,64, in addition to occupying an apical niche.

Following its injection into epithelial cells, CagA undergoes targeted tyrosine phosphorylation by SRC and ABL kinases at motifs containing the amino acid sequence EPIYA, which are located within the 3′ terminus of CagA65,66,67 (BOX 2). Intracellular phospho-CagA activates a cellular phosphatase (SHP2; also known as PTPN11), leading to morphological aberrations that mirror the changes that are induced by growth factor stimulation68,69. Specifically, transfection studies have demonstrated that phospho-CagA–SHP2 interactions contribute to cytoskeletal rearrangements and cell elongation by stimulating the RAP1A–BRAF–ERK signalling pathway68.

Lamina propria

A constituent of the moist linings of mucous membranes, which line different tubes of the body, including the gastrointestinal tract.

Polymorphic mosaic gene

A gene that exists as different alleles owing to defined regions that vary in sequence.

H. pylori tightly regulates the activity of SRC and ABL in a specific and time-dependent manner. SRC is activated during the initial stages of infection and is then rapidly inactivated, but ABL is continuously activated by H. pylori with enhanced activities at later time points, supporting a model of successive phosphorylation of CagA by SRC and ABL67. Phospho-CagA can also inhibit SRC through the recruitment of c-src tyrosine kinase (CSK), a negative regulator of SRC70. As SRC is the primary kinase activated by CagA, inhibition of SRC by phospho-CagA generates a negative feedback loop that carefully controls the amount of intracellular phospho-CagA. However, non-phosphorylated CagA also exerts effects in the cell that might lower the threshold for carcinogenesis. The cell adhesion protein E-cadherin, the hepatocyte growth factor receptor MET, the phospholipase Cγ (PLCγ), the adaptor protein growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (GRB2) and the kinase PAR1β (also known as MARK2) all interact with non-phosphorylated CagA71–74, which leads to pro-inflammatory and mitogenic responses, the disruption of cell–cell junctions and the loss of cell polarity. Non-phosphorylated CagA associates with the epithelial tight junction scaffolding protein ZO1 and the transmembrane protein junctional adhesion molecule A (JAMA; also known as F11R), leading to nascent but incomplete assembly of tight junctions at sites of bacterial attachment that are distant from sites of cell–cell contact75. CagA was recently shown to directly bind PAR1B (BOX 2; FIG. 2), a central regulator of cell polarity, and inhibit its kinase activity. This interaction dysregulates mitotic spindle formation in addition to promoting loss of cell polarity74,76,77. These events are dependent on conserved 16 amino acid repeat motifs embedded within the 3′ terminus of CagA, which have been termed CagA multimerization (Cm)78, conserved repeat responsible for phosphorylation-independent activity (CRPIA)79 or MARK2 kinase inhibitor (MKI)80 motifs. These motifs bind PAR1B and mediate the dimerization of CagA, which confers stronger SHP2 binding; the number of motifs can also vary between strains. A recent co-crystallography analysis of CagA bound to PAR1B demonstrated that the initial 14 amino acids of this motif occupy the substrate-binding site of PAR1B, leading to the inhibition of kinase function80.

Cag delivery of peptidoglycan

Another consequence of cag island-mediated host cell contact is the production of chemokines. Although the induction of inflammatory cytokines is dependent on the host signalling molecules nuclear factor-κb (NF-κB) and MAPK81–83, the specific bacterial effector that mediates chemokine production is not as clearly defined. In certain H. pylori strains, CagA can induce IL-8 expression through NF-κB activation84–86; however, the ability of CagA to mediate IL-8 expression is not universal across all cag-bearing strains81,82,87. In addition to CagA, the cag secretion system can also deliver components of H. pylori peptidoglycan into host cells through outer membrane vesicles88, where they are sensed by an intracytoplasmic pathogen-recognition molecule nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 1 (NOD1)89. NOD1 activation by H. pylori peptidoglycan stimulates NF-κB, p38 and ERK, culminating in the expression of the cytokines MIP2 (also known as CXCL2) and IL-8 (REFS 89,90). NOD1 activation by H. pylori peptidoglycan also initiates the production of type I interferon (IFN) through a signalling pathway that has been previously associated with viral infections91 (FIG. 2).

The delivery of peptidoglycan components into host cells induces additional epithelial responses with carcinogenic potential, such as the activation of PI3K and cell migration. The H. pylori gene slt encodes a soluble lytic transglycosylase that is required for peptidoglycan turnover and release89, thereby regulating the amount of peptidoglycan translocated into host cells. Inactivation of slt has been shown to inhibit H. pylori-induced PI3K signalling and cell migration92. The protein encoded by the H. pylori gene HP0310 deacetylates N-acetylglucosamine peptidoglycan residues and is required for normal peptidoglycan synthesis93. Loss of HP0310, which leads to decreased peptidoglycan production, reciprocally augments the delivery of the other major cag secretion system substrate, CagA, into host cells. This suggests that functional interactions occur between H. pylori translocated effectors94. These findings indicate that contact between cag+ strains and host cells activates multiple signalling pathways that regulate oncogenic cellular responses, which may heighten the risk for transformation, particularly over prolonged periods of colonization.

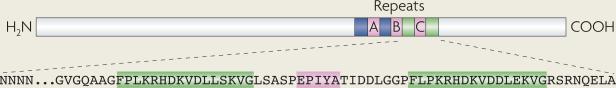

Box 2 | Modifiable motifs within the H. pylori CagA protein.

CagA phosphorylation sites consist of the amino acid motif EPIYA, which are embedded within the carboxyl terminus of CagA (see the figure). Four distinct EPIYA sites have been described, termed A, B, C and D, each of which is flanked by different sequences. EPIYA-A and EPIYA-B motifs are present in strains throughout the world. By contrast, EPIYA-C is found predominantly in strains from Western countries, and EPIYA-D is found in strains from East Asian countries. H. pylori CagA proteins may contain varying numbers of EPIYA motifs. H. pylori strains possessing more than three EPIYA-C motifs are more frequently associated with gastric atrophy, intestinal metaplasia and gastric cancer138,139. In vitro, EPIYA-D motifs exhibit a higher affinity for binding SHP2 than EPIYA-C motifs140, which may partially explain the increased risk of gastric carcinoma among H. pylori-infected people residing in East Asia. CagA EPIYA repeats are flanked by repetitive DNA sequences that are involved in recombination, which probably explains the variability in motif number among CagA variants, as well as strain-specific differences in pathogenicity, exerted by H. pylori strains harbouring cagA and cag pathogenicity island. In addition to EPIYA motifs, there are also PAR1B-interacting amino acid repeat motifs within the C terminus of CagA, which can vary in number.

Western-type CagA proteins contain the phosphorylation motifs EPIYA-A, EPIYA-B and EPIYA-C (pink boxes). Conserved 16 amino acid repeat motifs (FPLKRHDKVDDLSKVG; green boxes) embedded within the 3′ terminus of CagA bind PAR1B and mediate the dimerization of CagA.

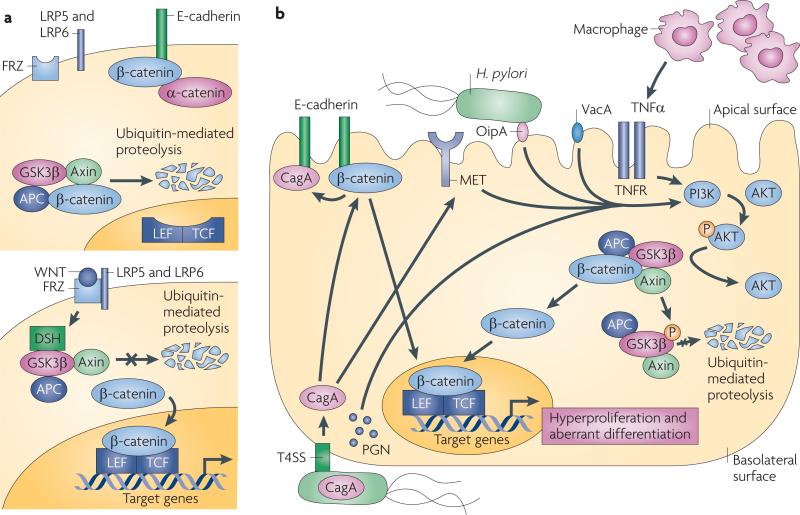

β-catenin in H. pylori carcinogenesis

A specific host molecule that may influence carcinogenic responses in conjunction with H. pylori is β-catenin, a ubiquitously expressed protein that has distinct functions within host cells. Membrane-bound β-catenin is a component of adherens junctions that link cadherin receptors to the actin cytoskeleton, and cytoplasmic β-catenin is a downstream component of the Wnt signal transduction pathway (FIG. 3a). In the absence of Wnt ligand, the inhibitory complex that is composed of axin, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) and glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β) induces the degradation of β-catenin and maintains low steady-state levels of free β-catenin either in the cytosol or the nucleus. After binding of Wnt to its receptor Frizzled, Dishevelled is activated, which prevents GSK3β from phosphorylating β-catenin, thus allowing β-catenin to translocate to the nucleus and activate the transcription of target genes that are involved in carcinogenesis.

Figure 3. Aberrant activation of β-catenin by Helicobacter pylori.

a | Membrane-bound β-catenin links cadherin receptors to the actin cytoskeleton, and in non-transformed epithelial cells β-catenin is primarily localized to E-cadherin complexes. Cytoplasmic β-catenin is a downstream component of the Wnt pathway; in the absence of Wnt (upper panel), cytosolic β-catenin remains bound within a multi-protein inhibitory complex comprised of glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β), the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumour suppressor protein and axin141. Under unstimulated conditions, β-catenin is constitutively phosphorylated (P) by GSK3β, ubiquitylated and degraded141. Binding of Wnt to its receptor, Frizzled (FRZ; lower panel), activates dishevelled (DSH) and Wnt co-receptors, low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) and LRP6, which then interact with axin and other members of the inhibitory complex, leading to the inhibition of the kinase activity of GSK3β141. These events inhibit the degradation of β-catenin, leading to its nuclear accumulation and formation of heterodimers with the transcription factor lymphocyte enhancer factor/T cell factor (LEF/TCF), resulting in the transcriptional activation of target genes that influence carcinogenesis. b | Injection of CagA results in the dispersal of β-catenin from β-catenin–E-cadherin complexes at the cell membrane, allowing β-catenin to accumulate in the cytosol and nucleus. CagA, potentially by binding MET or other H. pylori constituents such as OipA, VacA and peptidoglycan (PGN) as well as tumour necrosis factor-α (TNFα), which is produced by infiltrating macrophages, can activate PI3K, leading to the phosphorylation and inactivation of GSK3β. This liberates β-catenin to translocate to the nucleus and upregulate genes, leading to increased proliferation and aberrant differentiation; TNFR, TNF receptor.

Increased β-catenin expression or APC mutations are present in up to 50% of gastric adenocarcinoma specimens when compared with non-transformed gastric mucosa95, and the nuclear accumulation of β-catenin is increased in gastric adenomas and foci of dysplasia96, suggesting that aberrant activation of β-catenin precedes the development of gastric cancer. H. pylori increases the expression of β-catenin target genes in colonized mucosa and during co-culture with gastric epithelial cells in vitro; therefore, it is likely that the activation of β-catenin signalling is a central component in the regulation of pre-malignant epithelial responses to H. pylori.

H. pylori isogenic mutant studies have revealed that the translocation of CagA into gastric epithelial cells induces the nuclear accumulation and functional activation of β-catenin, events that are recapitulated in colonized rodent and human tissue97,98. Using a CagA-inducible gastric epithelial model system, Murata-Kamiya et al.73 demonstrated that intracellular CagA interacts with E-cadherin, disrupts the formation of E-cadherin–β-catenin complexes and induces nuclear accumulation of β-catenin, all of which are independent of CagA phosphorylation (FIG. 3b). Consequences of CagA-dependent β-catenin activation include the upregulation of target genes that influence gastric cancer, such as caudal type homeobox 1 (CDX1), which encodes an intestinal cell-specific transcription factor that is required for the development of intestinal metaplasia73. Concordant with the requisite motifs that regulate PAR1B inhibition by non-phosphorylated CagA, the specific molecular determinants that mediate the trans-location of β-catenin from the membrane to the nucleus have now been identified as CagA CM motifs (BOX 2).

Recently, additional pathways, including those that are mediated by the transactivation of EGFR (discussed below), have been demonstrated to regulate β-catenin activation in response to H. pylori. Activation of PI3K and AKT leads to the phosphorylation and inactivation of GSK3β, permitting β-catenin to accumulate in the cytosol and the nucleus. Suzuki et al.79 have shown that CagA CM motifs interact with MET, leading to the sustained induction of PI3K–AKT signalling in response to H. pylori and the subsequent activation of β-catenin in vitro and in vivo (FIG. 3b).

Studies focused on PI3K and AKT have revealed that other H. pylori constituents may also influence β-catenin activation. Infection of Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) epithelial cells with H. pylori leads to AKT-dependent β-catenin activation through GSK3β phosphorylation, although activation occurs independently of CagA in this system99. Using a different model cell system, Nakayama et al.100 reported that VacA can activate PI3K-dependent β-catenin activation, and OipA has also been implicated in aberrant nuclear localization of β-catenin, although the specific mechanism underpinning this observation has not yet been delineated49. Therefore, multiple H. pylori cancer-associated determinants seem to influence β-catenin activation, which is consistent with previous reports investigating mechanisms that regulate β-catenin activation by other bacteria. Co-culture of intestinal epithelial cells with nonpathogenic Salmonella typhimurium leads to the activation of β-catenin signalling by the AvrA-mediated blockade of β-catenin ubiquitylation101,102. Bacteroides fragilis toxin induces nuclear accumulation of β-catenin in human intestinal cells103, and bacterial LPS can stimulate the nuclear localization of β-catenin in myeloid cells through toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-dependent activation of PI3K, which subsequently inhibits GSK3β, thereby increasing steady-state levels of free β-catenin104. Owing to its prolonged colonization period in the stomach, however, it is difficult to discern which microbial factors elaborated by H. pylori exert dominant effects.

Transactivation of EGFR by H. pylori

EGFR is an important target for the treatment of several malignancies other than gastrointestinal cancers, and the phosphorylation and activation of EGFR increases the transcriptional activity of β-catenin by the inactivation of GSK3β. H. pylori infection, gastric epithelial hyperplasia and gastric atrophy are strongly linked to the dysregulation of EGFR and/or cognate ligands, such as heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HBEGF) in human, animal and cell culture models105–108. The in vitro transactivation of EGFR by H. pylori is dependent on genes in the cag pathogenicity island and secreted proteins as well as host factors such as TLR4 and NOD1 (REFS 109,110).

EGFR can be activated by direct interaction with ligands, which initiate dimerization and increased kinase activity (FIG. 4). Cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor-α (TNFα), as well as cell adhesion molecules and G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) transactivate EGFR in gastric epithelial cells111,112. EGFR transactivation by these elements is mediated through metalloproteinase-dependent cleavage of EGFR (Erbb family) ligands111 in a manner similar to H. pylori-induced EGFR transactivation83,105; the required metalloproteinases are likely to be members of the a disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM) family. Many membrane-bound proteins undergo proteolytic release from the membrane by ADAM family proteases. Given a requirement for metalloproteinase activity in H. pylori-initiated HBEGF release, ADAM17, a multi-domain type I transmembrane protein that contains an extracellular zinc-dependent protease domain, is an ideal candidate enzyme for the regulation of this pathway83,105. ADAM17 was the first ADAM to have a defined physiological substrate, the precursor transmembrane form of TNFα. Inhibitors of ADAM17 block the release of soluble TNFα, several members of the EGF ligand family and the ERBB4 ectodomain. Although ADAM17 is ubiquitously expressed in the gastrointestinal tract and is a target of drug development for inflammatory conditions, the disorganized and inflamed nature of the gastrointestinal tract that develops in ADAM17-deficient mice suggests that this metalloproteinase may also have an important role in gut epithelial homeostasis, perhaps through the regulation of EGFR ligands. Furthermore, the processing and availability of at least three EGFR ligands, HBEGF, transforming growth factor-α (TGFα) and amphiregulin (AREG), requires ADAM17 expression113,114. Therefore, a better understanding of the function of ADAM17 during H. pylori-induced gastric epithelial injury could provide insights into its potential role in gastric carcinogenesis.

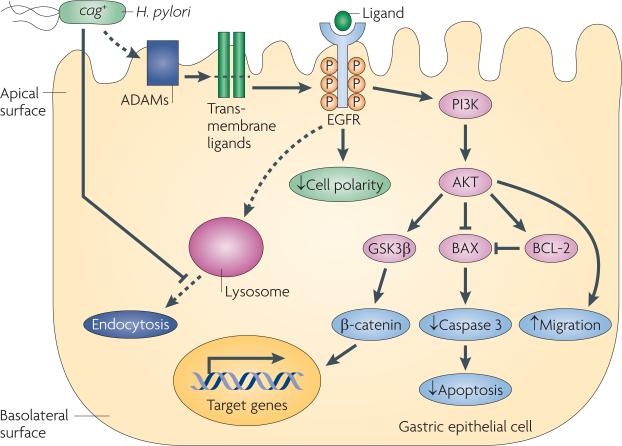

Figure 4. Transactivation of EGFR by H. pylori and induced cellular consequences with carcinogenic potential.

Helicobacter pylori transactivates epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) through cleavage, which is dependent on the a disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM) family proteinases, of EGFR ligands, such as heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HBEGF) in gastric epithelial cells. One downstream target of EGFR transactivation is PI3K–AKT, which leads to AKT-dependent cell migration, inhibition of apoptosis and β-catenin activation. BAX, BCL-2-associated X protein; GSK3β, glycogen synthase kinase-3β; P, phosphorylation.

H. pylori specifically amplifies EGFR signalling by both activating EGFR and decreasing EGFR degradation by blocking endocytosis115. In turn, the transactivation of EGFR by this pathogen mediates several cellular responses with pre-malignant potential (FIG. 4). Alterations in apoptosis have been implicated in the pathogenesis of H. pylori-induced injury before the development of gastric cancer. The ability of H. pylori to induce apoptosis in gastric epithelial cells has been well demonstrated in vitro16. However, chronically infected humans and mongolian gerbils harbouring cag+ strains exhibit increased gastric epithelial cell proliferation without a concordant increase in apoptosis116,117, which may contribute to the augmented risk for gastric cancer that is associated with cag+ strains. H. pylori has been shown to induce anti-apoptotic pathways in gastric epithelial cells through cag-mediated EGFR transactivation118 (FIG. 4). Altered cell polarity and migration are phenotypic responses to H. pylori infection and, although they may acutely promote gastric mucosal repair, long-term stimulation of these responses has been linked to transformation and tumorigenesis74,92. H. pylori-mediated transactivation of EGFR has also been shown to regulate epithelial cell migration through the cag-dependent activation of PI3K and AKT92 (FIG. 4). As the biological responses to EGFR activation include increased proliferation, reduced apoptosis, the disruption of cell polarity and enhanced migration, transactivation of EGFR by H. pylori is an attractive target for studying early events that may precede transformation.

Although the preponderance of evidence suggests that EGFR overexpression and activation are associated with tumorigenesis, recent studies raise questions about targeting EGFR for the treatment of gastric cancer119,120. Gastric cancer cells are resistant to inhibition of EGFR in the absence of concurrent MEK inhibition in vitro119, and surveys of human gastric cancer specimens for evidence of overexpression or mutations of EGFR have found both events to be rare120. Furthermore, when viewed within the context of the cytoprotective role of EGFR during infection with H. pylori121, future investigations using transgenic rodent models that are then confirmed by human studies will be crucial for defining the true link between EGFR transactivation, protection from gastritis and the potential for enhanced gastric cancer progression.

Inflammation, oncogenesis and H. pylori

Although H. pylori proteins and induced epithelial responses clearly influence disease risk, they are not absolute determinants of carcinogenesis, and the chronic inflammation that develops in response to this organism undoubtedly contributes to transformation. Studies in mice infected with the related mouse-adapted Helicobacter species, H. felis, have demonstrated that bone marrow-derived cells (BMDCs) home to and engraft in sites of chronic gastric inflammation — particularly within foci in which tissue injury induces excessive apoptosis and overwhelms the population of endogenous tissue stem cells122. Within the inflamed stomach, BMDCS degenerate into adenocarcinoma, suggesting that gastric epithelial carcinomas can originate from bone marrow-derived sources122. Polymorphisms in the human IL1B gene promoter that are associated with increased expression of IL-1β (a pro-inflammatory cytokine with potent acid-suppressive properties) heighten the risk for atrophic gastritis and gastric adenocarcinoma123. These relationships are present only among H. pylori-colonized people, emphasizing the importance of host–environment interactions and inflammation in the progression to gastric cancer. Recently, transgenic mice overexpressing human IL-1β in parietal cells were shown to develop spontaneous gastritis and dysplasia after 1 year of age, and they progressed to carcinoma when infected with H. felis124. These findings were linked to the activation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) through an NF-κB-dependent, but lymphocyte-independent, mechanism. Previous studies have demonstrated that gastric carcinogenesis in mice is dependent on the presence of CD4+ T cells. However, in this model of IL-1β overexpression, the marked infiltration of MDSCs into the gastric mucosa occurred early, accompanied by only a sparse infiltration of T cells. Furthermore, when IL-1β-transgenic mice were crossed on a T cell-deficient background (recombination activating gene 2 (Rag2)–/–), gastritis and dysplasia still developed124, suggesting that IL-1β induces gastric injury in an MDSC-dependent but T cell-independent manner.

In addition to IL-1β, high-expression polymorphisms in TNFα (a pro-inflammatory cytokine) also increase the risk of gastric cancer123. Oguma et al.125 recently identified a link between the expression of TNFα and aberrant β-catenin signalling in gastric cancer. They used transgenic mice that overexpress WNT1, which was under the control of the keratin 19 promoter (K19-Wnt1) in this model, in gastrointestinal epithelial cells; these mice develop gastric dysplasia. Within dysplastic foci, nuclear β-catenin was present in gastric epithelial cells that were in close juxtaposition to infiltrating macrophages, prompting in vitro experiments to determine whether secreted macrophage products could activate epithelial β-catenin signalling125. Conditioned media from activated macrophages induced β-catenin signalling in gastric epithelial cells, which was attenuated by the inhibition of TNFα. TNFα was then shown to induce phosphorylation of AKT and subsequently GSK3β, liberating β-catenin to translocate to the nucleus (FIG. 3b). Recapitulation of these in vitro events was accomplished by infecting K19-Wnt1 mice with H. felis, which resulted in macrophage infiltration and the accumulation of β-catenin in proliferating gastric epithelial cells125. H. felis infection also led to a loss of parietal cells, which are required for epithelial cell differentiation in gastric glandular units. These results invoke a model (FIG. 3b) in which microbial-induced gastritis promotes epithelial hyperproliferation and aberrant differentiation through Wnt-mediated pathways, thereby coupling inflammation and β-catenin signalling in the gastric carcinogenesis cascade.

Parietal cell

A secretory cell that produces acid and is present within the gastric corpus.

Myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC)

A heterogeneous and plastic cell. When isolated from normal bone marrow, it does not exhibit immunosuppresive effects. However, when exposed to the tumour microenvironment, it inhibits both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

Foveolar hyperplasia

Excessive proliferation of epithelial cells within foveolae, small pits from which gastric glands form that result in elongation and tortuosity of the glandular lumen.

Perspectives

Studies that focus on the specific interactions between H. pylori and its host can provide models for general patterns that may be extended to other malignancies that arise from inflammatory foci within the hepatobiliary and gastrointestinal tract. The vast majority of hepatocellular carcinomas are attributable to chronic Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C infections, and cholangio-carcinoma of the biliary tract is strongly linked to chronic inflammation that is induced by parasites126,127. Chronic oesophagitis, pancreatitis and ulcerative colitis each confer a significantly increased risk for the development of adenocarcinoma within their respective anatomic sites126. Focusing on colorectal neoplasia, commonalities between inflammation-induced gastric cancer and carcinomas that arise in the context of ulcerative colitis have been reported. DNA damage resulting from inflammation-associated reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) has a key role not only in dextran sulphate sodium (DSS)-induced colon tumours but also in the development of pre-malignant lesions in H. pylori-infected gastric mucosa. Specifically, the loss of a key DNA repair enzyme, alkyladenine DNA glycosylase (AAG; also known as MPG) that repairs RONS-induced DNA damage, augmented the severity of adenomas and adenocarcinomas in the colons as well as atrophy and foveolar hyperplasia in the stomachs of mice challenged with DSS or H. pylori, respectively128.

Another key effector influencing both gastric and intestinal carcinomas is β-catenin. In conjunction with the strong evidence implicating H. pylori-induced β-catenin activation in the pathogenesis of gastric cancer, numerous studies have demonstrated aberrant β-catenin signalling in carcinomas of the lower intestinal tract. In human colorectal carcinoma specimens, inactivating mutations of APC or axin are present in 70–75% of cases129. Germline APC mutations are responsible for familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), an autosomal dominant disorder that is characterized by the formation of hundreds to thousands of adenomatous polyps that carpet the colon, which initiate an inexorable progression to carcinoma in untreated cases. In regions of the world in which H. pylori prevalence rates are high (for example, Japan), the incidence of gastric cancer in patients with FAP ranges from 39% to 50%, and coexisting H. pylori infection increases the risk of gastric adenomas in these subjects compared with patients without FAP130,131.

Wnt-mediated pathways are crucial for stem cell renewal, and evidence indicates that H. pylori may intimately interact with this cell population. In transgenic mice that overexpress Leb, H. pylori directly adhere to gastric epithelial cells132,133. The genetic ablation of parietal cells in Leb-expressing transgenic mice permits the gastric epithelial progenitor (GEP) stem cell population to expand, which is accompanied by an expansion of H. pylori colonization and inflammation within glandular epithelium134,135. H. pylori has the capacity to directly interact with GEP cells29,136, and the delineation of the GEP transcriptome has identified several pathways that are over-represented in this lineage and which are of particular biological importance for carcinogenesis, including Wnt–β-catenin29. Aberrant activation of Wnt signalling in stem cells is a fundamental principle that underpins carcinogenesis in several organ systems, and within the gastrointestinal tract macrophages have been demonstrated to produce the Wnt ligands WNT2 and WNT5A in human colorectal carcinoma specimens. Therefore, mechanisms through which H. pylori aberrantly activates oncogenic signalling pathways may be applied more broadly to cancers affecting the entire gastrointestinal tract and facilitate a deeper understanding of how chronic inflammation leads to malignant degeneration in other organ systems.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors delcare no competing financial interests.

DATABASES

Entrez Gene: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene CDX1 | IL1B | IL2RA | keratin 19 | Rag2

UniProtKB: http://www.uniprot.org α5 | αv | β1 | β5 | β-catenin | AAG | ABL | ADAM17 | APC | AREG | BRAF | caspase 3 | CD4 | CSK | E-cadherin | EGFR | ERBB4 | FAK | FAP | fibronectin | GRB2 | GSK3β | HBEGF | IL-2 | IL-6 | IL-8 | integrin β2 | JAMA | Leb | Lex | Ley | NOD1 | MET | MIP2 | MMP1 | PAR1B | PTPRZ1 | RAC1 | RANTES | RAP1A | SHP2 | SRC | TGFα | TLR4 | TNFα | WNT1 | WNT2 | WNT5A | ZO1

FURTHER INFORMATION

Richard M. Peek's homepage: http://www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/ddrc

ALL LINKS ARE ACTIVE IN THE ONLINE PDF

References

- 1.Peek RM, Jr., Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal tract adenocarcinomas. Nature Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:28–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process-- First American Cancer Society Award Lecture on Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6735–6740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrera V, Parsonnet J. Helicobacter pylori and gastric adenocarcinoma. Clin. Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:971–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong BC, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication to prevent gastric cancer in a high-risk region of China: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:187–194. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.2.187. [One of the first large, randomized placebo-controlled trials to examine the effect of H. pylori eradication on the incidence of gastric cancer.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y, Blaser MJ. Inverse associations of Helicobacter pylori with asthma and allergy. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007;167:821–827. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.8.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dorer MS, Talarico S, Salama NR. Helicobacter pylori's unconventional role in health and disease. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000544. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bik EM, et al. Molecular analysis of the bacterial microbiota in the human stomach. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:732–737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506655103. [A seminal study that used molecular techniques to define the gastric microbiome.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhead JL, et al. A new Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin determinant, the intermediate region, is associated with gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:926–936. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cover TL, Blanke SR. Helicobacter pylori VacA, a paradigm for toxin multifunctionality. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 2005;3:320–332. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujikawa A, et al. Mice deficient in protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type Z. are resistant to gastric ulcer induction by VacA of Helicobacter pylori. Nature Genet. 2003;33:375–381. doi: 10.1038/ng1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hennig EE, Godlewski MM, Butruk E, Ostrowski J. Helicobacter pylori VacA cytotoxin interacts with fibronectin and alters HeLa cell adhesion and cytoskeletal organization in vitro. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2005;44:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seto K, Hayashi-Kuwabara Y, Yoneta T, Suda H, Tamaki H. Vacuolation induced by cytotoxin from Helicobacter pylori is mediated by the EGF receptor in HeLa cells. FEBS Lett. 1998;431:347–350. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00788-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molinari M, et al. The acid activation of Helicobacter pylori toxin VacA: structural and membrane binding studies. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998;248:334–340. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta VR, et al. Sphingomyelin functions as a novel receptor for Helicobacter pylori VacA. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000073. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sewald X, et al. Integrin subunit CD18 is the T-lymphocyte receptor for the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cover TL, Krishna US, Israel DA, Peek RM., Jr. Induction of gastric epithelial cell apoptosis by Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin. Cancer Res. 2003;63:951–957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gebert B, Fischer W, Weiss E, Hoffmann R, Haas R. Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin inhibits T lymphocyte activation. Science. 2003;301:1099–1102. doi: 10.1126/science.1086871. [This study demonstrated that a previously identified virulence factor could also suppress the immune response to H. pylori.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sundrud MS, Torres VJ, Unutmaz D, Cover TL. Inhibition of primary human T cell proliferation by Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin (VacA) is independent of VacA effects on IL-2 secretion. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:7727–7732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401528101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerhard M, et al. Clinical relevance of the Helicobacter pylori gene for blood-group antigen-binding adhesin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:12778–12783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miehlke S, et al. The Helicobacter pylori vacA s1, m1 genotype and cagA is associated with gastric carcinoma in Germany. Int. J. Cancer. 2000;87:322–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Louw JA, et al. The relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection, the virulence genotypes of the infecting strain and gastric cancer in the African setting. Helicobacter. 2001;6:268–273. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2001.00044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Figueiredo C, et al. Helicobacter pylori and interleukin 1 genotyping: an opportunity to identify high-risk individuals for gastric carcinoma. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1680–1687. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.22.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Doorn LJ, et al. Geographic distribution of vacA allelic types of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:823–830. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salama NR, Otto G, Tompkins L, Falkow S. Vacuolating cytotoxin of Helicobacter pylori plays a role during colonization in a mouse model of infection. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:730–736. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.2.730-736.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wirth HP, Beins MH, Yang M, Tham KT, Blaser MJ. Experimental infection of Mongolian gerbils with wild-type and mutant Helicobacter pylori strains. Infect. Immun. 1998;66:4856–4866. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4856-4866.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Algood HM, Torres VJ, Unutmaz D, Cover TL. Resistance of primary murine CD4+ T cells to Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin. Infect. Immun. 2007;75:334–341. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01063-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomb JF, et al. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [The first annotated description of the entire genome sequence from a single H. pylori strain. This study provided a framework for investigators to delve into H. pylori–host interactions and understand how these relationships affect carcinogenesis.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alm RA, et al. Genomic-sequence comparison of two unrelated isolates of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1999;397:176–180. doi: 10.1038/16495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oh JD, et al. The complete genome sequence of a chronic atrophic gastritis Helicobacter pylori strain: evolution during disease progression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:9999–10004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603784103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McClain MS, Shaffer CL, Israel DA, Peek RM, Jr., Cover TL. Genome sequence analysis of Helicobacter pylori strains associated with gastric ulceration and gastric cancer. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ilver D, et al. Helicobacter pylori adhesin binding fucosylated histo-blood group antigens revealed by retagging. Science. 1998;279:373–377. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Solnick JV, Hansen LM, Salama NR, Boonjakuakul JK, Syvanen M. Modification of Helicobacter pylori outer membrane protein expression during experimental infection of rhesus macaques. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:2106–2111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308573100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahdavi J, et al. Helicobacter pylori SabA adhesin in persistent infection and chronic inflammation. Science. 2002;297:573–578. doi: 10.1126/science.1069076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monteiro MA, et al. Expression of histo-blood group antigens by lipopolysaccharides of Helicobacter pylori strains from Asian hosts: the propensity to express type 1 blood-group antigens. Glycobiology. 2000;10:701–713. doi: 10.1093/glycob/10.7.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wirth HP, et al. Phenotypic diversity in Lewis expression of Helicobacter pylori isolates from the same host. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1999;133:488–500. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(99)90026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Appelmelk BJ, et al. Phase variation in Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide due to changes in the lengths of poly(C) tracts in alpha3-fucosyltransferase genes. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:5361–5366. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5361-5366.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Linden S, Boren T, Dubois A, Carlstedt I. Rhesus monkey gastric mucins: oligomeric structure, glycoforms and Helicobacter pylori binding. Biochem. J. 2004;379:765–775. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pohl MA, et al. Host-dependent Lewis (Le) antigen expression in Helicobacter pylori cells recovered from Leb-transgenic mice. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:3061–3072. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamaoka Y, et al. Importance of Helicobacter pylori oipA in clinical presentation, gastric inflammation, and mucosal interleukin 8 production. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:414–424. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamaoka Y, Kwon DH, Graham DY. A M(r) 34, 000 proinflammatory outer membrane protein (oipA) of Helicobacter pylori. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:7533–7538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130079797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamaoka Y, et al. Role of interferon-stimulated responsive element-like element in interleukin-8 promoter in Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1030–1043. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu H, et al. Regulation of interleukin-6 promoter activation in gastric epithelial cells infected with Helicobacter pylori. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:4954–4966. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-05-0426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kudo T, et al. Regulation of RANTES promoter activation in gastric epithelial cells infected with Helicobacter pylori. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:7602–7612. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7602-7612.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu JY, et al. Balance between polyoma enhancing activator 3 and activator protein 1 regulates Helicobacter pylori-stimulated matrix metalloproteinase 1 expression. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5111–5120. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ando T, et al. Host cell responses to genotypically similar Helicobacter pylori isolates from United States and Japan. Clin. Diagn Lab. Immunol. 2002;9:167–175. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.9.1.167-175.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Odenbreit S, Kavermann H, Puls J, Haas R. CagA tyrosine phosphorylation and interleukin-8 induction by Helicobacter pylori are independent from AlpAB, HopZ and Bab group outer membrane proteins. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2002;292:257–266. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Akanuma M, et al. The evaluation of putative virulence factors of Helicobacter pylori for gastroduodenal disease by use of a short-term Mongolian gerbil infection model. J. Infect. Dis. 2002;185:341–347. doi: 10.1086/338772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dossumbekova A, et al. Helicobacter pylori HopH (OipA) and bacterial pathogenicity: genetic and functional genomic analysis of hopH gene polymorphisms. J. Infect. Dis. 2006;194:1346–1355. doi: 10.1086/508426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Franco AT, et al. Regulation of gastric carcinogenesis by Helicobacter pylori virulence factors. Cancer Res. 2008;68:379–387. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Odenbreit S, et al. Translocation of Helicobacter pylori CagA into gastric epithelial cells by type IV secretion. Science. 2000;287:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1497. [One of the first studies to demonstrate that H. pylori has the capacity to translocate a bacterial protein into host cells.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mimuro H, et al. Helicobacter pylori dampens gut epithelial self-renewal by inhibiting apoptosis, a bacterial strategy to enhance colonization of the stomach. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:250–263. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ohnishi N, et al. Transgenic expression of Helicobacter pylori CagA induces gastrointestinal and hematopoietic neoplasms in mouse. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:1003–1008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711183105. [A remarkable study demonstrating that transgenic expression of CagA in mice can lead to carcinoma, in the absence of co-existing gastritis.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lu H, Hsu PI, Graham DY, Yamaoka Y. Duodenal ulcer promoting gene of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:833–848. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Z, et al. The Helicobacter pylori duodenal ulcer promoting gene, dupA in China. BMC Gastroenterol. 2008;8:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-8-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arachchi HS, et al. Prevalence of duodenal ulcer-promoting gene (dupA) of Helicobacter pylori in patients with duodenal ulcer in North Indian population. Helicobacter. 2007;12:591–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schmidt HM, et al. The prevalence of the duodenal ulcer promoting gene (dupA) in Helicobacter pylori isolates varies by ethnic group and is not universally associated with disease development: a case-control study. Gut Pathog. 2009;1:5. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nguyen LT, et al. Helicobacter pylori dupA gene is not associated with clinical outcomes in the Japanese population. Clin. Microbiol Infect. 2009 October 14; doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03081.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1469–06912009.03081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gomes LI, et al. Lack of association between Helicobacter pylori infection with dupA-positive strains and gastroduodenal diseases in Brazilian patients. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2008;298:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Argent RH, Burette A, Miendje Deyi VY, Atherton JC. The presence of dupA in Helicobacter pylori is not significantly associated with duodenal ulceration in Belgium, South Africa, China, or North America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007;45:1204–1206. doi: 10.1086/522177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Douraghi M, et al. dupA as a risk determinant in Helicobacter pylori infection. J. Med. Microbiol. 2008;57:554–562. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47776-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kwok T, et al. Helicobacter exploits integrin for type IV secretion and kinase activation. Nature. 2007;449:862–866. doi: 10.1038/nature06187. [This study identified the specific cag protein and its cognate host receptor that permits CagA translocation.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jimenez-Soto LF, et al. Helicobacter pylori type IV secretion apparatus exploits beta1 integrin in a novel RGD-independent manner. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000684. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Necchi V, et al. Intracellular, intercellular, and stromal invasion of gastric mucosa, preneoplastic lesions, and cancer by Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1009–1023. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aspholm M, et al. SabA is the H. pylori hemagglutinin and is polymorphic in binding to sialylated glycans. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e110. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Selbach M, Moese S, Hauck CR, Meyer TF, Backert S. Src is the kinase of the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:6775–6778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100754200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stein M, et al. c-Src/Lyn kinases activate Helicobacter pylori CagA through tyrosine phosphorylation of the EPIYA motifs. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;43:971–980. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tammer I, Brandt S, Hartig R, Konig W, Backert S. Activation of Abl by Helicobacter pylori: a novel kinase for CagA and crucial mediator of host cell scattering. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1309–1319. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Higashi H, et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA induces Ras-independent morphogenetic response through SHP-2 recruitment and activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:17205–17216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309964200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Higashi H, et al. SHP-2 tyrosine phosphatase as an intracellular target of Helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Science. 2002;295:683–686. doi: 10.1126/science.1067147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Selbach M, et al. The Helicobacter pylori CagA protein induces cortactin dephosphorylation and actin rearrangement by c-Src inactivation. EMBO J. 2003;22:515–528. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mimuro H, et al. Grb2 is a key mediator of Helicobacter pylori CagA protein activities. Mol. Cell. 2002;10:745–755. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00681-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Churin Y, et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA protein targets the c-Met receptor and enhances the motogenic response. J. Cell Biol. 2003;161:249–255. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Murata-Kamiya N, et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA interacts with E-cadherin and deregulates the beta-catenin signal that promotes intestinal transdifferentiation in gastric epithelial cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:4617–4626. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Saadat I, et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA targets PAR1/MARK kinase to disrupt epithelial cell polarity. Nature. 2007;447:330–333. doi: 10.1038/nature05765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Amieva MR, et al. Disruption of the epithelial apical-junctional complex by Helicobacter pylori CagA. Science. 2003;300:1430–1434. doi: 10.1126/science.1081919. [An insightful study demonstrating the ability of CagA to aberrantly disrupt apical-junctional complexes.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Umeda M, et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA causes mitotic impairment and induces chromosomal instability. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:22166–22172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.035766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lu H, Murata-Kamiya N, Saito Y, Hatakeyama M. Role of Partitioning-defective 1/Microtubule Affinity-regulating Kinases in the morphogenetic activity of Helicobacter pylori CagA. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:23024–23036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.001008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kurashima Y, et al. Deregulation of beta-catenin signal by Helicobacter pylori CagA requires the CagA-multimerization sequence. Int. J. Cancer. 2008;122:823–831. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Suzuki M, et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA phosphorylation-independent function in epithelial proliferation and inflammation. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ne Sbreve Ic D, et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA inhibits PAR1-MARK family kinases by mimicking host substrates. Nature Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:130–132. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Keates S, et al. Differential activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases in AGS gastric epithelial cells by cag+ and cag- Helicobacter pylori. J. Immunol. 1999;163:5552–5559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Meyer-Ter-Vehn T, Covacci A, Kist M, Pahl HL. Helicobacter pylori activates mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades and induces expression of the proto-oncogenes c-fos and c-jun. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:16064–16072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000959200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Keates S, et al. cag+ Helicobacter pylori induce transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor in AGS gastric epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:48127–48134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107630200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Brandt S, Kwok T, Hartig R, Konig W, Backert S. NF-κB activation and potentiation of proinflammatory responses by the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:9300–9305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409873102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kim SY, Lee YC, Kim HK, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori CagA transfection of gastric epithelial cells induces interleukin-8. Cell. Microbiol. 2006;8:97–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lamb A, et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA activates NF-kappaB by targeting TAK1 for TRAF6-mediated Lys 63 ubiquitination. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:1242–1249. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Naumann M, et al. Activation of activator protein 1 and stress response kinases in epithelial cells colonized by Helicobacter pylori encoding the cag pathogenicity island. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:31655–31662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kaparakis M, et al. Bacterial membrane vesicles deliver peptidoglycan to NOD1 in epithelial cells. Cell. Microbiol. 2010;12:372–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Viala J, et al. Nod1 responds to peptidoglycan delivered by the Helicobacter pylori cag pathogenicity island. Nature Immunol. 2004;5:1166–1174. doi: 10.1038/ni1131. [This study identified an additional substrate of the cag secretion system, peptidoglycan.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Allison CC, Kufer TA, Kremmer E, Kaparakis M, Ferrero RL. Helicobacter pylori induces MAPK phosphorylation and AP-1 activation via a NOD1-dependent mechanism. J. Immunol. 2009;183:8099–8109. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Watanabe T, et al. NOD1 contributes to mouse host defense against Helicobacter pylori via induction of type I IFN and activation of the ISGF3 signaling pathway. J. Clin. Invest. 2010 April 12; doi: 10.1172/JCI39481. doi: 10.1172/JCI39481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nagy TA, et al. Helicobacter pylori regulates cellular migration and apoptosis by activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling. J. Infect. Dis. 2009;199:641–651. doi: 10.1086/596660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang G, Olczak A, Forsberg LS, Maier RJ. Oxidative stress-induced peptidoglycan deacetylase in Helicobacter pylori. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:6790–6800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808071200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Franco AT, et al. Delineation of a carcinogenic Helicobacter pylori proteome. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2009;8:1947–1958. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900139-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tsukashita S, et al. Beta-catenin expression in intramucosal neoplastic lesions of the stomach. Comparative analysis of adenoma/dysplasia, adenocarcinoma and signet-ring cell carcinoma. Oncology. 2003;64:251–258. doi: 10.1159/000069310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cheng XX, et al. Frequent translocalization of beta-catenin in gastric cancers and its relevance to tumor progression. Oncol. Rep. 2004;11:1201–1207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Franco AT, et al. Activation of β-catenin by carcinogenic Helicobacter pylori. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:10646–10651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504927102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Suzuki M, et al. Interaction of CagA with Crk plays an important role in Helicobacter pylori-induced loss of gastric epithelial cell adhesion. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202:1235–1247. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sokolova O, Bozko PM, Naumann M. Helicobacter pylori suppresses glycogen synthase kinase 3beta to promote beta-catenin activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:29367–29374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801818200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nakayama M, et al. Helicobacter pylori VacA-induced inhibition of GSK3 through the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:1612–1619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806981200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Neish AS, et al. Prokaryotic regulation of epithelial responses by inhibition of IkappaB-alpha ubiquitination. Science. 2000;289:1560–1563. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sun J, Hobert ME, Rao AS, Neish AS, Madara JL. Bacterial activation of beta-catenin signaling in human epithelia. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G220–G227. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00498.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wu S, Morin PJ, Maouyo D, Sears CL. Bacteroides fragilis enterotoxin induces c-Myc expression and cellular proliferation. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:392–400. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Monick MM, et al. Lipopolysaccharide activates Akt in human alveolar macrophages resulting in nuclear accumulation and transcriptional activity of beta-catenin. J. Immunol. 2001;166:4713–4720. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wallasch C, et al. Helicobacter pylori-stimulated EGF receptor transactivation requires metalloprotease cleavage of HB-EGF. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;295:695–701. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00740-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Romano M, et al. Helicobacter pylori upregulates expression of epidermal growth factor-related peptides, but inhibits their proliferative effect in MKN 28 gastric mucosal cells. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;101:1604–1613. doi: 10.1172/JCI1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Schiemann U, et al. mRNA expression of EGF receptor ligands in atrophic gastritis before and after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Med. Sci. Monit. 2002;8:CR53–CR58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]