Abstract

Estrogen and iron play critical roles in a female body development and were investigated in the present study in relation to in vitro cell proliferation. Prempro™, a hormone replacement therapy drug, and 17β-estradiol (E2) were shown to increase cell proliferations in estrogen receptor positive (ER+) cells independent of progesterone receptor (PR) status. For example, increased cell proliferation was observed in ER+/PR+ human breast cancer MCF-7, its matching non-cancerous human breast epithelial MCF-12A, and ER+/PR+ murine mammary cancer MXT+ cells, but not in ER−/PR− MDA-MB-231, its matching non-cancerous MCF-10A, and MXT− (ER−/PR+) cells. By mimicking post-menopausal conditions of high estrogen in local breast tissue and increased iron levels due to cessation of menstrual periods, E2 and iron were shown to exert synergistic effects on proliferation of MCF-7 cells and significantly increased Ki67 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Western blotting of E2-treated ER+ but not ER− cells showed that E2 also increased transferrin receptor (TfR). Further studies are needed to assess the mitogenic effects of iron and estrogen in normal post-menopausal breast.

Keywords: Iron, Estrogen, Progesterone, Breast cancer, Cell proliferation, Menopause

Introduction

Breast cancer incidence rates are higher in post-menopausal women than in pre-menopausal women. Several of the well-established risk factors for breast cancer, such as early age at menarche, nulliparity, late first full-time pregnancy, and/or late menopause, have suggested that a long life-time exposure to estrogens contributes to breast cancer development.1 A meta-analysis of nine prospective studies on post-menopausal levels of endogenous sex hormones and breast cancer showed a strong association of estrogens with breast cancer risk.2 Epidemiological and clinical studies indicate that hormone replacement therapy (HRT) may also increase the risk of breast cancer in post-menopausal women.3–5 However, this increased breast cancer incidence rate in post-menopausal women cannot be simply explained by estrogen or the use of HRT because overall estrogen levels decrease due to menopause.

Menopause is a natural aging process during which time a woman passes from the reproductive with active ovarian function to the non-reproductive years during which ovarian function ceases. In the course of the natural menopause transition, the dynamics of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian hormones change dramatically from cyclic-to-static patterns and serum levels of estrogen and progesterone (Pg) significantly diminish.6,7 Although estrogen is no longer an endocrine factor in post-menopausal women, estrogen is produced locally in breast tissue by aromatase cytochrome P450 (P450arom, the product of the CYP19 gene).8–10 Therefore, despite the marked decline in serum estrogen levels after menopause, breast tissue E2 levels in pre- and post-menopausal women do not significantly differ.11,12 In post-menopausal women, prostaglandin E2 increases intracellular cAMP levels and stimulates estrogen biosynthesis as a consequence of overexpression of the cyclooxygenase type II.12,13 Considering comparable levels of breast tissue estrogen and lower serum estrogen, one still cannot explain higher breast cancer incidence rates in post-menopausal women as compared to pre-menopausal women. These observations strongly suggest that factors other than estrogen may contribute to breast cancer development in post-menopausal women.

One of the most striking physiological differences between pre- and post-menopausal women besides those in endocrine factors is in iron (Fe) status. Due to the cessation of menstrual bleeding, serum levels of Fe, such as that bound to ferritin and transferrin, are 2–3 times higher in post- than in pre-menopausal women.14–16 Ferritin, an Fe storage protein with a capacity of binding up to 4500 atoms of Fe per molecule of ferritin,17 and transferrin, an Fe transport protein with two binding sites for Fe, are more saturated in post- than in pre-menopausal women.18,19 Because of these profound pre- and post-menopausal differences in Fe status, it is conceivable that Fe is an etiological factor in the development of breast cancer in post-menopausal women.

In the present study, we investigated the effects of Prempro™, the most prescribed drug for post-menopausal symptoms,20 as well as 17β-estradiol (E2), Pg, and Fe on proliferation of breast epithelial cancer and non-cancer cells. Various cell lines with different estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) status were used in a cell culture system. Our results suggest that high levels of Fe, which is associated with the cessation of menstrual blood, in conjunction with HRT or high levels of endogenous estrogen, could contribute to breast cancer development in post-menopausal women.

Materials and methods

Chemical reagents

Fetal bovine serum (FBS), antibiotics, and l-glutamine were obtained from Atlanta Biologicals (Norcross, GA). Alpha minimum essential medium (α-MEM), tamoxifen (Tam), E2-water soluble, Pg, ferrous sulfate septahydrate, crystal violet, glutaraldehyde, ethanol, methanol, and monoclonal mouse-anti-β-tubulin antibodies were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Other reagents were: transferrin receptor (TfR) ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), mouse-anti-human TfR antibodies (Research Diagnostics Inc., Flanders, NJ), anti-mouse PCNA antibody and rabbit polyclonal Ki67 antibody (Abcam, Inc., Cambridge, MA), peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), cell lysis M-Per buffer (Pierce, Rockford, IL), Prempo™ tablets (Wyeth-Ayerst Pharmaceuticals, Philadelphia, PA).

Cell culture

Human breast cancer estrogen receptor positive and progesterone receptor positive (ER+/PR+) MCF-7 and ER−/PR− MDA-MB-231 and the immortalized human non-cancerous breast epithelial MCF-12A (ER+/PR+) and MCF-10A (ER−/PR−) cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). MXT+ cell line was derived from the murine mammary cancer model MXT−M-3,2 MC (hormone sensitive), which was induced by urethane treatment in female C57BLxDBAfF1 mice.21 MXT− cell line was derived from the MXT−M-3,2 (OVX) MC (hormone insensitive) mice.22 MXT+ cells with ER+/PR+ and MXT− cells (ER−/PR+) were previously characterized.23 All cells were initially cultured in α-MEM containing 10% FBS and 0.9 mg/ml l-glutamine in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air, 5% CO2 at 37 °C and changed to 0.1% FBS as indicated in the figure legends for treatments.

Measurements of cell proliferation

To evaluate cell proliferation, a crystal violet assay as well as Western blotting using proliferation markers of PCNA and Ki67 were employed as previously described.23,24 To test the effect of Prempro™, the tablet containing 0.625 mg conjugated estrogens and 2.5 mg of medroxy-progesterone acetate (MPA) was weighed (approximately 350 mg) and ground in an agar mortar and suspended in water. Subsequently, a series of dilutions was made and 10 µl of the diluted Prempro™ suspensions were added into the wells to make the final doses of 0, 1, 2, 5, 10 µg/cm2 in a total volume of 200 µl per well. For each dose of Prempro™, 16 replicates on two slots of a 96-well microplate were used. One microplate was also used for each time point (0, 24, 48, 72, 96 and 120 h). Data were presented as µg/cm2 because at these exposure conditions the tablet was not completely soluble. Based on the surface area of 0.36 cm2 in each well and 200 µl of culture media, one µg/cm2 Prempro™ tablet is equivalent to 10−8 M E2 and 3.3 × 10−8 M MPA assuming that the conjugated estrogens and MPA are completely solubilized.

After treatments, the cell culture medium was removed. One hundred µl of 1% (w/w) glutaraldehyde dissolved in 1 × PBS were then added into each well and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. The glutaraldehyde solutions were subsequently replaced with 150 µl 1 × PBS and the plate was stored at 4 °C until the last plate was collected. Cells in each well were then stained with 0.02% crystal violet solution (100 µl/well) for 30 min. After washing off the excess dye with water, cells in each well were re-dissolved in 70% ethanol at 180 µl/well. After shaking the microplate for 3 h, absorbance was recorded at 578 nm on a microplate reader (Molecular Device, CA).

The effects of chemical reagents on cell proliferation were calculated as follows23: [%] T/C = (T–C0)/(C–C0) × 100 with T representing the mean absorbance of the treated cells, C representing the mean absorbance of the controls, and C0 representing the mean absorbance of the cells at time zero.

Water-soluble E2, Pg, and Fe as ferrous sulfate were all freshly prepared in distilled water at high concentrations except Tam in methanol and further diluted in α-MEM before MCF-7 cell treatment. The selected doses for the testing were relevant to pharmacological doses during HRT use. For the effect of Tam, Tam was added 2 h before E2 or Pg treatment. For the combined effects of Fe and E2, E2 was first added to MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, and MCF-10A cells, and followed by Fe in α-MEM containing 0.1% FBS. The reason for using 0.1% FBS was to avoid the confounding effects of transferrin Fe from the added serum. MCF-12A cells were tested in the presence of 10% FBS because these cells could not survive in α-MEM containing 0.1% FBS. The experiments were quadruplicated in testing these compounds.

To further confirm the effects of E2 and Fe on cell proliferation, MCF-7 cells were collected using a rubber policeman, lysed with M-Per lysis buffer (Pierce). Cell lysates (30 µg protein) were subjected to 7.5% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween-20 and probed with antibodies against Ki67, PCNA or β-tubulin. Antibody binding signals were visualized with peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse antibody using Western Lightning Plus Chemiluminescence Reagent (Perkin-Elmer, Wellesley, MA).

Determination of TfR by Western blotting and ELISA

After treatments with E2 and/or Fe, MCF-7 culture media were collected for TfR measurements. MCF-7, MCF-10A, and MDA-MB-231 cells were collected using a rubber policeman, lysed with M-Per lysis buffer (Pierce), and subjected to Western blot using TfR antibody. TfR in tissue culture media was determined by ELISA using two different monoclonal antibodies specific for TfR (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Twenty microliter culture media were used and the amount of TfR was measured by incubation with a chromogenic substrate at 450 nm.

Statistical analysis

To assure reproducibility, the experiments were repeated at least three times. Graphed data represent the means ± SD. The statistical significance of experimental differences was determined by Student’s t-test. A two-tailed p-value of <0.05 was taken to represent a significant difference in all cases.

Results

Effects of Prempro™ on proliferation of human breast epithelial cells with different ER and PR status

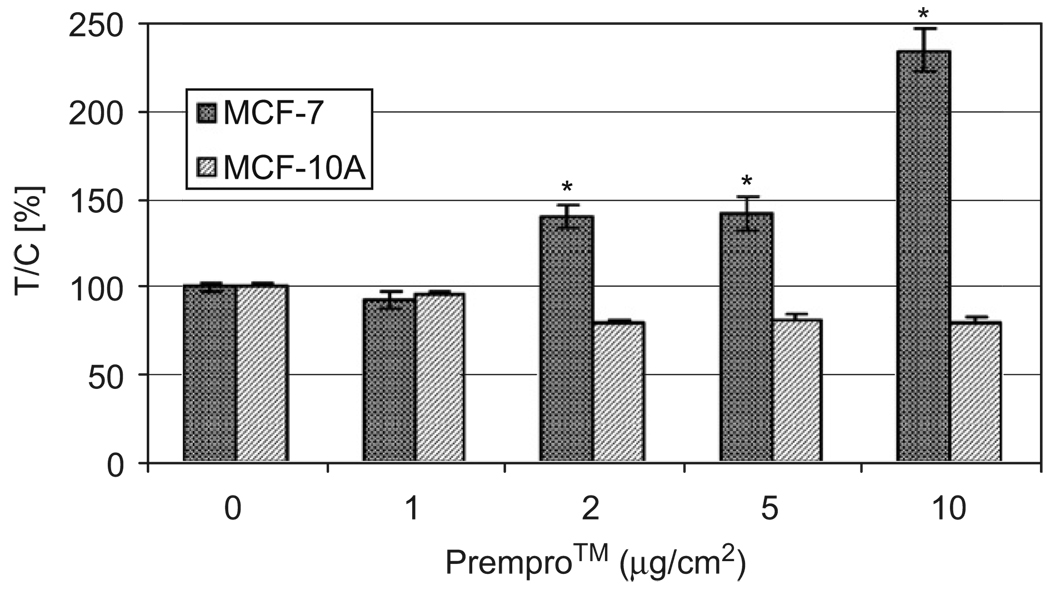

Fig. 1 shows that Prempro™ increased cell proliferation in MCF-7 cells, which are ER+ and PR+. Prempro™ had no effect on cell proliferation of ER−/PR− MCF-10A cells. The increases in proliferation of MCF-7 cells were Prempro™ dose-dependent at 48 h treatment. There was no increase in cell proliferation in ER−/PR− MCF-10A cells treated with low doses of Prempro™. In fact, high doses (≥ 5 µg/cm2 Prempro™) inhibited ER− cell growth (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effects of Prempro™ on proliferation of human breast cancer MCF-7 but not MCF-10A cells. MCF-7 (ER+/PR+) and MCF-10A (ER−/PR−) cells were treated with 0, 1, 2, 5, and 10 µg/cm2 of Prempro™ in 10% FBS α-MEM medium in a 96-well plate for 48 h. One µg/cm2 of Prempro™ equals to 10−8 M E2 and 3.3 × 10−8 MPA in culture media. *Significantly different from control, p < 0.05.

Effects of Prempro™ on proliferation of mouse mammary cancer MXT cells with different ER but similar PR status

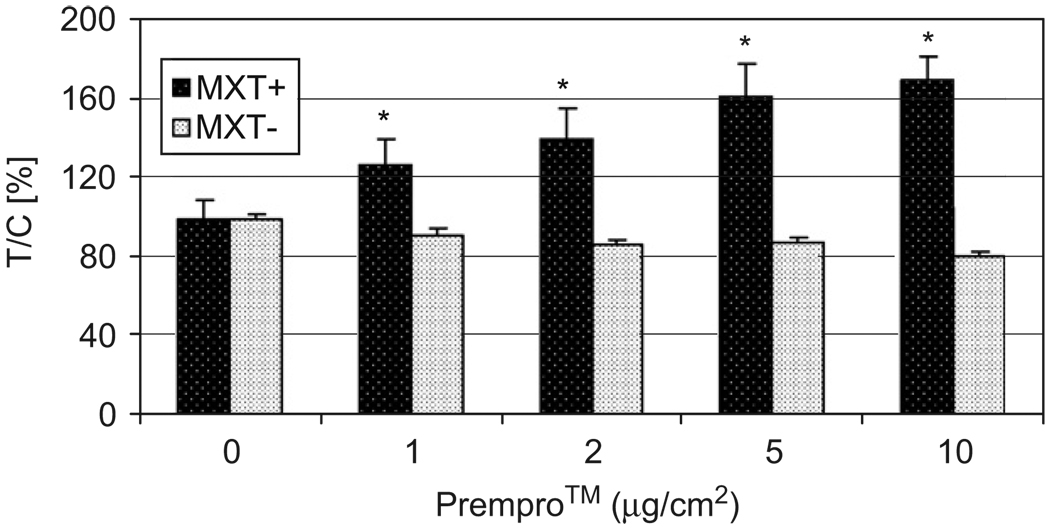

To determine the roles ER and PR status in Prempro™-mediated cell proliferation, mouse mammary cancer MXT+ (ER+/PR+) and MXT− (ER−/PR+) cells were used for comparison. PR levels were previously shown to be similar between MXT+ and MXT− cells.23 Prempro™ increased proliferation of ER+/PR+ MXT+ cells but not ER−/PR+ MXT− cells at 24 h treatment (Fig. 2). After ≥48 h treatment, proliferation of MXT+ cells had reached a maximal growth level under the conditions used (10% FBS-containing α-MEM) and no significant differences were observed between the control MXT+ cells and the Prempro™-treated MXT+ cells. Treatment of MXT− cells with Prempro™ at 10 µg/cm2 for 72 h or longer resulted in a significant inhibition as compared with the control MXT− cells (73.4±1.1% of control readings, p < 0.05). These results indicate that the difference in ER status between these two cell lines is the main factor responsible for the difference in cell proliferation response to Prempro™ treatment.

Fig. 2.

Effects of Prempro™ on proliferation of mouse mammary cancer MXT+ but not MXT− cells. MXT+ (ER+/PR+) and MXT− (ER−/PR+) cells were treated with 0, 1, 2, 5, and 10 µg/cm2 of Prempro™ in 10% FBS α-MEM medium in a 96-well plate for 24 h. *Significantly different from control, p < 0.05.

Effects of E2, Pg, and Tam on proliferation of MCF-7 cells

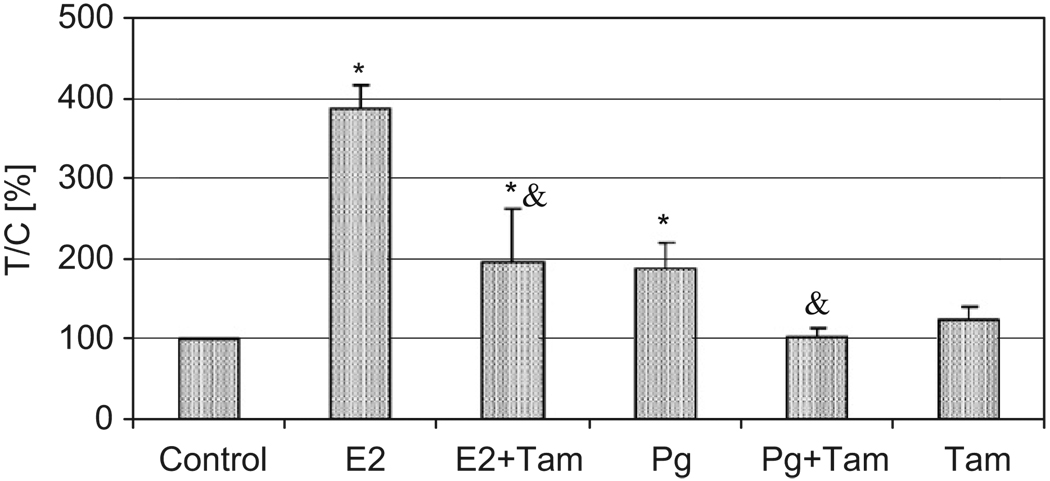

MCF-7 cells were separately treated with 1 nM E2 or 4 nM Pg and/or 5 µM Tam. Fig. 3 shows that E2 significantly increased cell proliferation by 289% over controls after 72 h treatment. At 48 h, the increase over the control was 102% for 1 nM E2 and 123% for 10 nM E2 (data not shown). Tam, an antagonist for ER, significantly inhibited E2-induced cell proliferation. Under these experimental conditions, Tam itself had no effect on MCF-7 or on Pg-induced cell proliferation. Pg also significantly increased MCF-7 cell proliferation (89% over controls).

Fig. 3.

Effects of 17β-estradiol (E2), progesterone (Pg), and/or Tam on proliferation of human breast cancer MCF-7 cells. MCF-7 cells were treated with E2 at 10−9 M, Pg at 4 × 10−9 M, and Tam at 5 µM for 72 h. *Significantly different from control, p < 0.05. &Significantly different from cells treated with E2 or Pg alone, p < 0.05.

Additive or synergistic effects of E2 and iron on cell proliferation

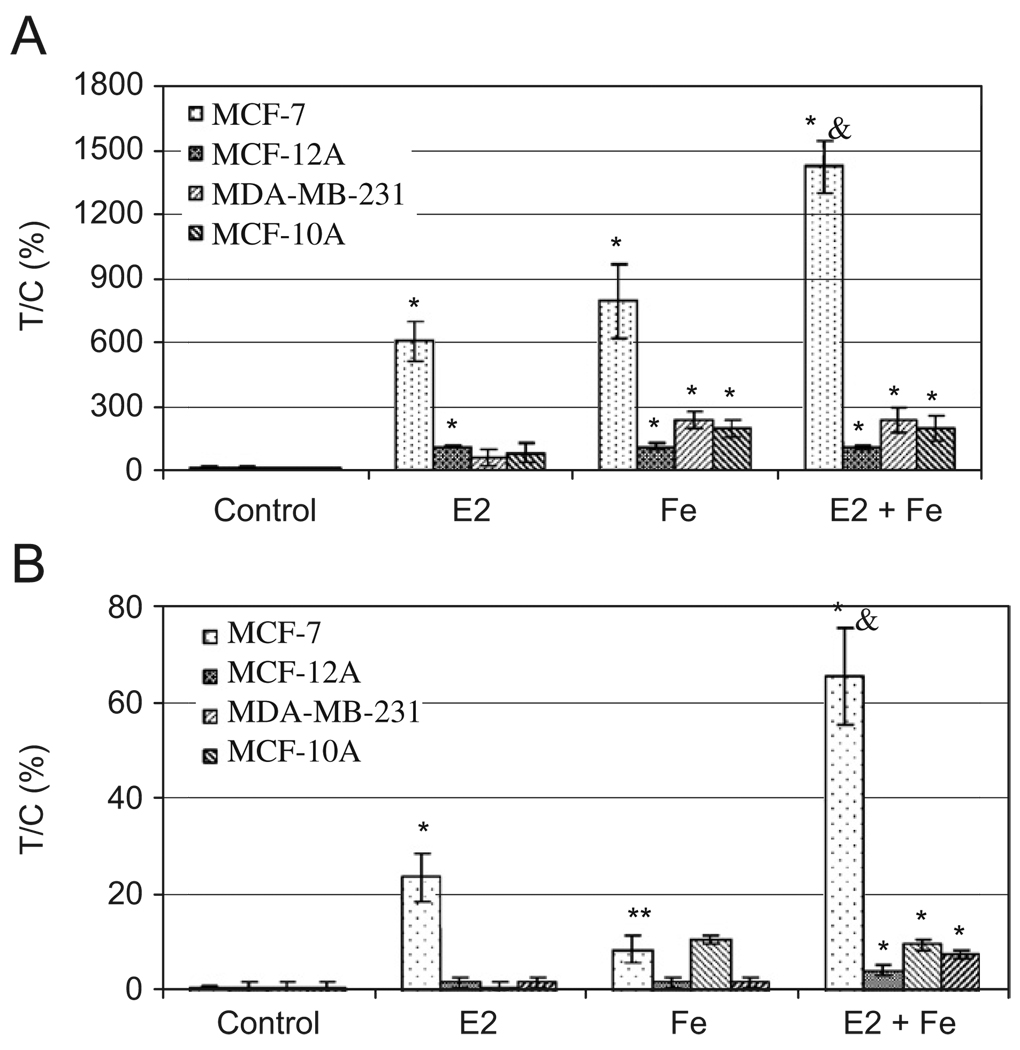

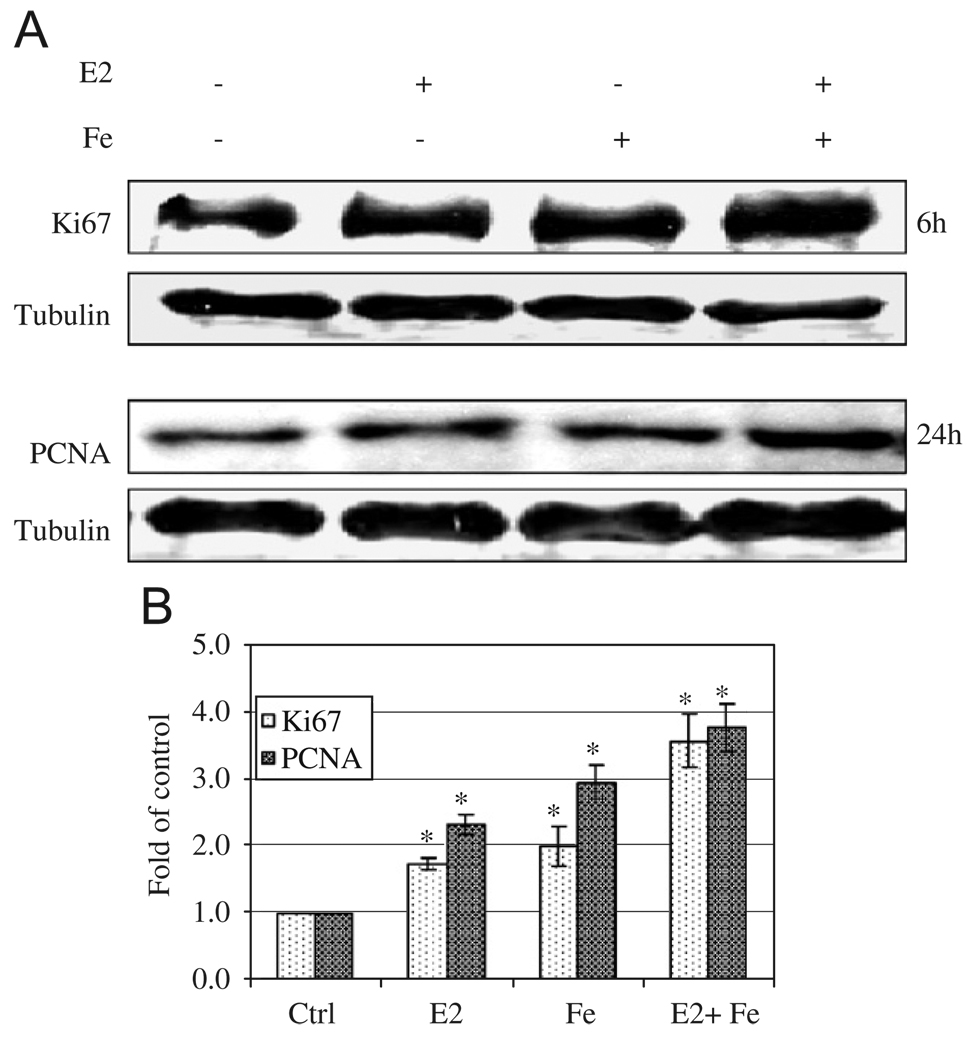

To determine whether Fe contributes, synergistically or additively, to E2-induced cell proliferation, breast cancer MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 and the non-cancerous MCF-12A and MCF-10A cells were treated with E2 and/or Fe. Fig. 4A shows that E2 significantly increased proliferation of ER+ MCF-7 and MCF-12A cells, but not ER− MDA-MB-231 or MCF-10A cells. In contrast, Fe increased proliferation of all types of cells (Fig. 4A). E2 and Fe together, in the presence of 0.1% FBS, significantly enhanced MCF-7 cell proliferation as compared to either factor alone. The combined effects of E2 (10−9 M) and Fe (10 µM) at these concentrations appeared to be additive (Fig. 4A). It is noteworthy that the additive effects of E2 and Fe on MCF-12A cells were not evident. This may be due to the presence of 10% FBS, masking the proliferating effects of E2 and Fe. Lowering E2 and Fe concentrations by one order of magnitude, E2 at 10−10 M or Fe at 1 µM resulted in only a 24% or 9% increase in cell proliferation over the control MCF-7 cells, respectively (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, E2 at 10−10 M with Fe at 1 µM together displayed a 66% increase in cell proliferation over the control MCF-7 cells (Fig. 4B). These effects were neither observed in MDA-MB-231 or MCF-10A cells, which are ER−, nor in ER+ MCF-12A cells, which were grown in 10% FBS. These results indicate that lower doses of E2 or Fe lead to a less robust cell proliferation, but the combined effects were synergistic in ER+/PR+ breast cancer MCF-7 cells. This was further confirmed by Ki67 and PCNA, markers of cell proliferation, showing more intense band with E2 and Fe than control or either alone (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Additive (A) and synergistic (B) effects of E2 and iron on MCF-7 cell proliferation. MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, and MCF-10A cells were treated with 1 × 10−9 M E2 and/or 10 µM Fe (A) or 1 × 10−10 M E2 and/or 1 µM Fe (B) in 0.1% FBS α-MEM for 24 h except MCF-12A cells in 10% FBS. *Significantly different from control, p < 0.05. &Significantly different from cells treated with E2 or iron alone, p < 0.05.

Fig. 5.

Enhancing effects of E2 and iron on Ki67 and PCNA, markers of cell proliferation. MCF-7 cells grown in 0.1% FBS α-MEM were treated with E2 (10−9 M), iron (10 µM) or E2 + iron cultured in 6-well dish for 6 and 24 h. Cells were collected and lysed using M-Per lysis buffer. Thirty µg of protein samples were loaded to each well for Ki67, PCNA, and β-tubulin Western blotting. A representative gel was shown from three replicates (A) and folds of increase over controls were shown in (B) after quantification by densitometry. *Significantly different from control for both Ki67 and PCNA, p < 0.05.

Up-regulation of TfR by E2

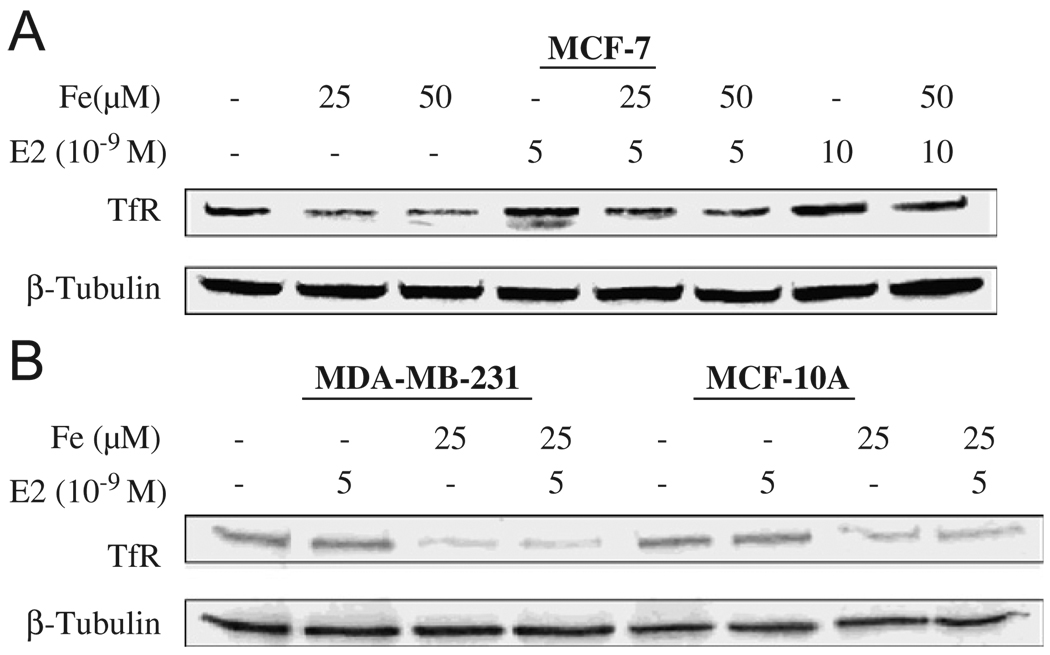

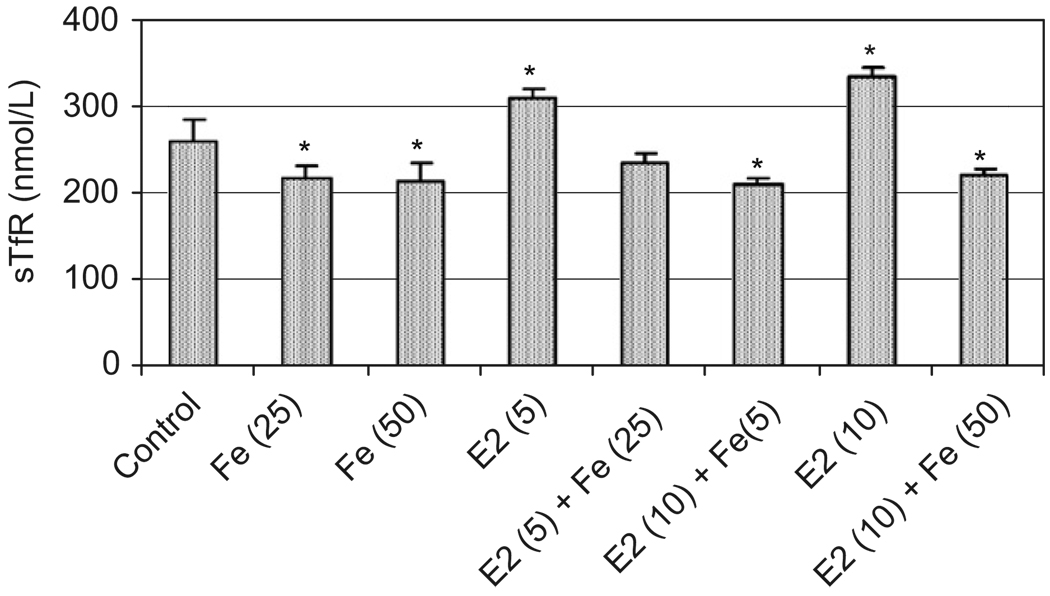

To investigate mechanism of a combined exposure to E2 and Fe on cell proliferation, Western blotting and ELISA techniques were employed to detect TfR, a membrane protein with a molecular weight of 90 kDa, which controls cellular Fe uptake.25,26 Fe at 25 and 50 µM down-regulated the expression of TfR protein in MCF-7 cells (Fig. 6A, lanes 2 and 3), a normal Fe metabolism effect through a negative feed-back mechanism. Interestingly, E2 at 5 and 10 nM induced TfR (Fig. 6A, lanes 4 and 7). This induction may be due to the increased cell proliferation, which requires more Fe at the time when an Fe supply is limited. However, when Fe was present in the tissue culture medium, the induction of TfR by E2 was not significant (Fig. 6A, lanes 5, 6, and 8). Fig. 6B showed that E2 had no effects on TfR induction in ER− MCF-10A and MDA-MB-231 cells. Fe also significantly decreased culture media levels of TfR while E2 increased their TfR levels (Fig. 7), findings paralleling those of the Western blotting and suggesting that the membrane-bound TfR can be released into the culture medium.

Fig. 6.

Enhancing effects of E2 on TfR regulation in ER+ MCF-7 (A) but not in ER− MCF-10A and MDA-MB-231 cells (B), and inhibitory effects of iron on TfR in all cells. ER+ MCF-7 cells were treated with E2 at 5 × 10−9 and 10 × 10−9 M in a 10-cm cell culture dish in 10% FBS α-MEM for 24 h, medium removed, then followed by exposure to iron at 25 and 50 µM in 0.1% FBS α-MEM for additional 24 h. ER− MCF-10A and MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with E2 at 5 × 10−9 M and/or iron at 25 µM in the same manner. Cells were collected and lysed using M-Per lysis buffer. Thirty microgram of protein samples were loaded to each well for TfR and β-tubulin Western blotting.

Fig. 7.

Effects of E2 and/or iron on TfR levels in tissue culture media. MCF-7 cells were treated with E2 in 10−9 M ranges and/or iron in µM ranges as described in Fig. 6A and in parentheses. Cell culture media were collected for TfR determination using ELISA method. *Significantly different from control, p < 0.05.

Discussion

Increasing evidence demonstrates that post-menopausal HRT with estrogen alone or estrogen plus progestin may increase breast cancer risk.27 In the present study, we have shown that Prempro™, a drug often used for HRT in post-menopausal women, enhanced cell proliferation only in ER+ cells (e.g., MCF-7 or MXT+ cells), regardless of PR status (e.g., PR− MCF-10A or PR+ MXT− cells). These results suggest that equine estrogen in the Prempro™ tablet may be the main active ingredient causing ER+ cell proliferation. Interestingly, since the release of the Women’s Health Initiatives’ (WHI) findings on Prempro™ and increased breast cancer risk in 2002, a sharp decrease in incidence from 2002 to 2003 was recently reported in women between 50 and 69 years old who predominantly, but not exclusively, had ER+ breast tumors.28 Although many factors could contribute to the decline, it apparently mirrored the drop in hormone use that occurred after the reported findings of WHI.29 Our results on ER+ cell proliferation by Prempro™, in agreement with the observed decrease in ER+ breast tumors during 2002–2003, suggest that HRT use could contribute to ER+ breast tumor development in post-menopausal women.

Prempro™ had no cell proliferating effect on ER−/PR+ MXT− and ER−/PR− MCF-10A cells, suggesting that MPA in the Prempro™ tablet may be inactive in stimulating cell growth or PR in MXT− cells is not functional. In fact, one previous study has shown that E2 stimulated and MPA slightly inhibited the growth of normal human endometrium in a novel organotypic culture model.30 The inhibiting effects of MPA were in contrast to the effect of Pg, which significantly enhanced proliferation of MCF-7 cells (Fig. 3). These results suggest that MPA may have some non-Pg-like effects, enhancing breast cancer risk when used in combination with estrogen therapy.31,32 Tam, an E2 antagonist, decreased E2- and Pg-induced proliferation suggesting that both E2 and Pg effects involve the ER.

Fe and estrogen are two of the most important growth nutrients in a female body development. Fe is essential for cell growth and metabolic processes that include oxygen transport, enzyme functions, DNA synthesis, and electron transport.33 Yet, mounting evidence indicates that increased Fe levels in the body may be associated with increased risk of cancer.34–37 During menopause or perimenopause, Fe accumulates slowly in the female body due to the cessation of menstrual bleeding and is chelated by Fe proteins such as ferritin and transferrin.18,19,38 Estrogens influence the growth, differentiation, and function of tissues of the female reproductive system, i.e., uterus, ovary, and breast.39 Estrogen’s growth-stimulating effects could make it a cancer promoter.40,41 Recent work suggests that estrogen metabolites formed in the body may also cause the initiating mutations.42,43 4-Hydroxyestrone (4-HE) and 16α-hydroxyestrone (16-α) are the main metabolites that may induce alkylation and oxidation of DNA contributing to cancer development.43–45 Although menopause results in a decrease of serum estrogen levels, estrogen levels in breast tissue are much higher than in the serum because of the aromatase activity present in the breast.11,46 Therefore, breast tissues in post-menopausal women are locally exposed to high levels of Fe and estrogen as compared to those in pre-menopausal women, who are characterized by low Fe and high estrogen. This observation prompted us to investigate whether combined exposure of Fe and E2 could enhance breast cell proliferation. Indeed, we have shown an additive effect on the growth of ER+ breast cancer MCF-7 cells at high doses of E2 and Fe and synergistic effect at low doses, which are physiologically relevant47,48 (Fig. 4). Because the non-cancerous MCF-12A cells could not be tested in 0.1% FBS (cell death), we were not able to show whether this effect is true in normal breast epithelial cells. Further in vivo studies are needed to assess this mitogenic effect.

The roles of Fe and estrogen in breast cancer have long been suspected but have not been specifically studied in tandem, particularly in relation to breast epithelial cell proliferation. Previous studies have mainly focused on redox cycling of catecholestrogen metabolites between quinone and catechol forms. The formation of superoxide anions may reduce Fe3+ stored in ferritin and release Fe2+ from it.49,50 It was shown that an elevated dietary Fe intake enhances the incidence of carcinogen-induced mammary cancer in rats and estrogen-induced kidney tumors in Syrian hamsters.51 A sub-cutaneous administration of ferrous sulfate subsequent to DMBA initiation greatly accelerated mammary carcinogenesis in female Sprague-Dawley rats, implying Fe’s promoting activity.52

The maintenance of Fe homeostasis is regulated by TfR that transport Fe into the cell and by ferritin sequestering this metal.53,54 Cellular Fe uptake depends on the numbers of membrane-bound TfR.25,55 Because of the pivotal role of TfR in Fe uptake, the TfR is more abundantly expressed in rapidly dividing cells than quiescent cells,56,57 and high levels of TfR expression have been identified on many tumors.58–60 In fact, studies have shown that expression of TfR is more abundant in breast cancer tissue than in normal tissue.60,61 Given the facts that estrogen and Fe exert their biological effects through their receptors,62,63 it is important to know whether E2 affects TfR in cells with different ER and PR status.

We have shown that MCF-7 cells treated with Fe down-regulated their TfR expression. E2 up-regulated TfR expression in a dose-dependent manner in ER+ cells, but not in ER− cells (Fig. 6). Some of the over-expressed TfR were released into the tissue culture media (Fig. 7). Previous studies have shown that E2 can induce a novel transferrin binding protein structurally related to the stress-regulated proteins in MCF-7 cells, and lactoferrin in the female reproductive tract of mouse, rat, and hamster.64,65 A recent study has further demonstrated that E2 induces transferrin gene expression in MCF-7 cells through a non-consensus distal estrogen-responsive element.66 In our study, this E2-induced TfR up-regulation appears to be Fe-independent, possibly through estrogen-responsive element in the promoter region of TfR gene.

Collectively, our results suggest that Fe and estrogen may be concomitantly involved in the proliferation of ER+ breast cells. This finding may be significant and relevant to breast cancer development in post-menopausal women because Fe levels in this population are high due to the cessation of menstrual periods. Although serum levels of estrogen decrease in post-menopausal women, it is important to recognize that local breast tissue estrogen levels are high, comparable to the levels before menopause. Therefore, post-menopausal women experience high levels of estrogen and Fe in the breast, which could make them more susceptible to breast cancer development.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Department of Defense (DAMD17-03-1-0717) and the National Cancer Institute (R21 CA132684) and in part by NIH Grants ES10344, ES00260, CA34588, and CA16087.

Abbreviations

- α-MEM

alpha-minimal essential medium

- E2

17β-estradiol

- ER

estrogen receptor

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- HRT

hormone replacement therapy

- MPA

medroxy-progesterone acetate

- Pg

progesterone

- PR

progesterone receptor

- Tam

tamoxifen

- TfR

transferrin receptor

References

- 1.ESHRE Capri Workshop Group. Hormones and breast cancer. Hum Reprod Update. 2004;10:281–293. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmh025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Endogenous Hormones and Breast Cancer Collaborative Group. Endogenous sex hormones and breast cancer in postmenopausal women: reanalysis of nine prospective studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:606–616. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.8.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormone replacement therapy: collaborative reanalysis of data from 51 epidemiological studies of 52,705 women with breast cancer and 108,411 women without breast cancer. Lancet. 1997;350:1047–1059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bellino FL. Biology of menopause. In: Bellino FL, editor. Serono symposia USA. vol. XVIII 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellino FL, Wise PM. Nonhuman primate models of menopause workshop. Biol Reprod. 2003;68:10–18. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.005215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simpson ER, Davis SR. Minireview: aromatase and the regulation of estrogen biosynthesis—some new perspectives. Endocrinology. 2001;142:4589–4594. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.11.8547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simpson E, Rubin G, Clyne C, Robertson K, O’Donnell L, Jones M, et al. The role of local estrogen biosynthesis in males and females. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2000;11:184–188. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(00)00254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simpson ER. Biology of aromatase in the mammary gland. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2000;5:251–258. doi: 10.1023/a:1009590626450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jefcoate CR, Liehr JG, Santen RJ, Sutter TR, Yager JD, Yue W, et al. Tissue-specific synthesis and oxidative metabolism of estrogens. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2000:95–112. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brueggemeier RW, Richards JA, Petrel TA. Aromatase and cyclooxygenases: enzymes in breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;86:501–507. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bulun SE, Fang Z, Imir G, Gurates B, Tamura M, Yilmaz B, et al. Aromatase and endometriosis. Semin Reprod Med. 2004;22:45–50. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-823026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu JM, Hankinson SE, Stampfer MJ, Rifai N, Willett WC, Ma J. Body iron stores and their determinants in healthy postmenopausal US women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:1160–1167. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.6.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milman N, Byg KE, Ovesen L, Kirchhoff M, Jurgensen KS. Iron status in Danish women, 1984–1994: a cohort comparison of changes in iron stores and the prevalence of iron deficiency and iron overload. Eur J Haematol. 2003;71:51–61. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2003.00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koziol JA, Ho NJ, Felitti VJ, Beutler E. Reference centiles for serum ferritin and percentage of transferrin saturation, with application to mutations of the HFE gene. Clin Chem. 2001;47:1804–1810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrison PM, Arosio P. The ferritins: molecular properties, iron storage function and cellular regulation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1275:161–203. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(96)00022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zacharski LR, Ornstein DL, Woloshin S, Schwartz LM. Association of age, sex, and race with body iron stores in adults: analysis of NHANES III data. Am Heart J. 2000;140:98–104. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2000.106646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitfield JB, Treloar S, Zhu G, Powell LW, Martin NG. Relative importance of female-specific and non-female-specific effects on variation in iron stores between women. Br J Haematol. 2003;120:860–866. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hersh AL, Stefanick ML, Stafford RS. National use of postmenopausal hormone therapy: annual trends and response to recent evidence. JAMA. 2004;291:47–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watson C, Medina D, Clark JH. Estrogen receptor characterization in a transplantable mouse mammary tumor. Cancer Res. 1977;37:3344–3348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watson CS, Medina D, Clark JH. Characterization of progesterone receptors, estrogen receptors, and estrogen (type II)-binding sites in the hormone-independent variant of the MXT-3590 mouse mammary tumor. Endocrinology. 1980;107:1432–1437. doi: 10.1210/endo-107-5-1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernhardt G, Beckenlehner K, Spruss T, Schlemmer R, Reile H, Schonenberger H. Establishment and characterization of new murine breast cancer cell lines. Arch Pharm (Weinheim) 2002;335:55–68. doi: 10.1002/1521-4184(200205)335:2<55::AID-ARDP55>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Ohara N, Takekida S, Xu Q, Maruo T. Comparative effects of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor on the growth of cultured human uterine leiomyoma cells and myometrial cells. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:1456–1465. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pantopoulos K. Iron metabolism and the IRE/IRP regulatory system: an update. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1012:1–13. doi: 10.1196/annals.1306.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ponka P, Lok CN. The transferrin receptor: role in health and disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1999;31:1111–1137. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(99)00070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeh IT. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy: endometrial and breast effects. Adv Anat Pathol. 2007;14:17–24. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e31802ef00f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jemal A, Ward E, Thun MJ. Recent trends in breast cancer incidence rates by age and tumor characteristics among US women. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R28. doi: 10.1186/bcr1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McNeil C. Breast cancer decline mirrors fall in hormone use, spurs both debate and research. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:266–267. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blauer M, Heinonen PK, Martikainen PM, Tomas E, Ylikomi T. A novel organotypic culture model for normal human endometrium: regulation of epithelial cell proliferation by estradiol and medrox-yprogesterone acetate. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:864–871. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colditz GA, Hankinson SE, Hunter DJ, Willett WC, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, et al. The use of estrogens and progestins and the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1589–1593. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506153322401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stevenson JC. Hormone replacement therapy: review, update, and remaining questions after the Women’s Health Initiative Study. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2004;2:12–16. doi: 10.1007/s11914-004-0009-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Le NT, Richardson DR. The role of iron in cell cycle progression and the proliferation of neoplastic cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1603:31–46. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(02)00068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang X. Iron overload and its association with cancer risk in humans: evidence for iron as a carcinogenic metal. Mutat Res. 2003;533:153–171. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kwok JC, Richardson DR. The iron metabolism of neoplastic cells: alterations that facilitate proliferation? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2002;42:65–78. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00213-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Torti FM, Torti SV. Regulation of ferritin genes and protein. Blood. 2002;99:3505–3516. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weinberg ED. The role of iron in cancer. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1996;5:19–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cade JE, Moreton JA, O’Hara B, Greenwood DC, Moor J, Burley VJ, et al. Diet and genetic factors associated with iron status in middle-aged women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:813–820. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.4.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Platet N, Cathiard AM, Gleizes M, Garcia M. Estrogens and their receptors in breast cancer progression: a dual role in cancer proliferation and invasion. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2004;51:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raafat AM, Hofseth LJ, Haslam SZ. Proliferative effects of combination estrogen and progesterone replacement therapy on the normal postmenopausal mammary gland in a murine model. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:340–349. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.110447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshidome K, Shibata MA, Couldrey C, Korach KS, Green JE. Estrogen promotes mammary tumor development in C3(1)/SV40 large T-antigen transgenic mice: paradoxical loss of estrogen receptor alpha expression during tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6901–6910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russo J, Hasan Lareef M, Balogh G, Guo S, Russo IH. Estrogen and its metabolites are carcinogenic agents in human breast epithelial cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;87:1–25. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00390-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Service RF. New role for estrogen in cancer? Science. 1998;279:1631–1633. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5357.1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bolton JL, Yu L, Thatcher GR. Quinoids formed from estrogens and antiestrogens. Methods Enzymol. 2004;378:110–123. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)78006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bolton JL. Quinoids, quinoid radicals, and phenoxyl radicals formed from estrogens and antiestrogens. Toxicology. 2002;177:55–65. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00195-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parl FF. Estrogens, estrogen receptor and breast cancer. Oxoford: IOS Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma Y, de Groot H, Liu Z, Hider RC, Petrat F. Chelation and determination of labile iron in primary hepatocytes by pyridinone fluorescent probes. Biochem J. 2006;395:49–55. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petrat F, de Groot H, Rauen U. Subcellular distribution of chelatable iron: a laser scanning microscopic study in isolated hepatocytes and liver endothelial cells. Biochem J. 2001;356:61–69. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3560061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wyllie S, Liehr JG. Release of iron from ferritin storage by redox cycling of stilbene and steroid estrogen metabolites: a mechanism of induction of free radical damage by estrogen. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;346:180–186. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liehr JG, Jones JS. Role of iron in estrogen-induced cancer. Curr Med Chem. 2001;8:839–849. doi: 10.2174/0929867013372931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wyllie S, Liehr JG. Enhancement of estrogen-induced renal tumor-igenesis in hamsters by dietary iron. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:1285–1290. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.7.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Diwan BA, Kasprzak KS, Anderson LM. Promotion of dimethylbenz[a]anthracene-initiated mammary carcinogenesis by iron in female Sprague-Dawley rats. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:1757–1762. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.9.1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chung J, Wessling-Resnick M. Molecular mechanisms and regulation of iron transport. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2003;40:151–182. doi: 10.1080/713609332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Donovan A, Andrews NC. The molecular regulation of iron metabolism. Hematol J. 2004;5:373–380. doi: 10.1038/sj.thj.6200540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Conrad ME, Umbreit JN. Pathways of iron absorption. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2002;29:336–355. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2002.0564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trowbridge IS, Omary MB. Human cell surface glycoprotein related to cell proliferation is the receptor for transferrin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:3039–3043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.5.3039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sutherland R, Delia D, Schneider C, Newman R, Kemshead J, Greaves M. Ubiquitous cell-surface glycoprotein on tumor cells is proliferation-associated receptor for transferrin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:4515–4519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.7.4515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prost AC, Menegaux F, Langlois P, Vidal JM, Koulibaly M, Jost JL, et al. Differential transferrin receptor density in human colorectal cancer: a potential probe for diagnosis and therapy. Int J Oncol. 1998;13:871–875. doi: 10.3892/ijo.13.4.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lloyd JM, O’Dowd T, Driver M, Tee DE. Demonstration of an epitope of the transferrin receptor in human cervical epithelium—a potentially useful cell marker. J Clin Pathol. 1984;37:131–135. doi: 10.1136/jcp.37.2.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang DC, Wang F, Elliott RL, Head JF. Expression of transferrin receptor and ferritin H-chain mRNA are associated with clinical and histopathological prognostic indicators in breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:541–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shindelman JE, Ortmeyer AE, Sussman HH. Demonstration of the transferrin receptor in human breast cancer tissue. Potential marker for identifying dividing cells. Int J Cancer. 1981;27:329–334. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910270311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murphy MJ., Jr Molecular action and clinical relevance of aromatase inhibitors. Oncologist. 1998;3:129–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Troccoli R, Stella F, Biagioni S, Battistelli S, Cerroni L, et al. Marcheggiani F, et al. Ferritin and transferrin levels in human breast cyst fluids: relationship with intracystic electrolyte concentrations. Clin Chim Acta. 1990;192:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(90)90265-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Poola I, Kiang JG. The estrogen-inducible transferrin receptor-like membrane glycoprotein is related to stress-regulated proteins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:21762–21769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Teng CT, Beard C, Gladwell W. Differential expression and estrogen response of lactoferrin gene in the female reproductive tract of mouse, rat, and hamster. Biol Reprod. 2002;67:1439–1449. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.101.002089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vyhlidal C, Li X, Safe S. Estrogen regulation of transferrin gene expression in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. J Mol Endocrinol. 2002;29:305–317. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0290305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]