Abstract

High resolution cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) was utilized to visualize Treponema pallidum, the causative agent of syphilis, at the molecular level. Three-dimensional (3-D) reconstructions from 304 infectious organisms revealed unprecedented cellular structures of this unusual member in the spirochetal family. High resolution cryo-ET reconstructions provided the detailed structures of the cell envelope, which is significantly different from that of gram-negative bacteria. The 4 nm lipid bilayer of both outer and cytoplasmic membranes resolved in 3-D reconstructions, providing an important marker for interpreting membrane-associated structures. Abundant lipoproteins cover the outer leaflet of the cytoplasmic membrane, in contrast to the rare outer membrane proteins visible by scanning probe microscopy. High resolution cryo-ET images also provided the first observation of T. pallidum chemoreceptor arrays, as well as structural details of the periplasmically located, cone-shaped structure at both ends of bacterium. Furthermore, 3-D subvolume averages of the periplasmic flagellar motors and filaments from living organisms revealed the novel flagellar architectures that may facilitate their rotation within the confining periplasmic space. Together, our findings provide the most detailed structural understanding of the periplasmic flagella and the surrounding cell envelope, which enable this enigmatic bacterium to efficiently penetrate tissue and escape host immune responses.

INTRODUCTION

Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum is the causative agent of syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease with more than 12 million new cases worldwide each year 1. Since 2000, the number of reported cases of primary and secondary syphilis has been rising annually in the United States 2. Of major concern is the recognition that syphilis infection greatly increases susceptibility to HIV infection 3. In addition, closely related organisms cause endemic syphilis (T. pallidum subsp. endemicum), yaws (T. pallidum subsp. pertenue), pinta (T. carateum), and venereal spirochetosis of rabbits (T. paraluiscuniculi) 4. The genome sequences of several of these organisms have been determined 5; 6, T. pallidum continues to be an enigmatic pathogen because of the lack of readily identifiable virulence determinants and the poorly understood pathogenesis of the disease. This deficiency is due primarily to the inability to culture members of this group of obligate pathogens continuously in vitro 7.

T. pallidum is a member of the Spirochetaceae, a biomedically important bacterial phylum that includes the etiological agents of Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi) 8 and leptospirosis (Leptospira interrogans) 9. A striking feature of T. pallidum and other spirochetes is their capacity to swim efficiently in a highly viscous, gel-like environment, such as connective tissue, where most externally flagellated bacteria are slowed down or stopped 10. Therefore, motility is likely to play an important role in the widespread dissemination of spirochetal infections and the establishment of chronic disease 10; 11. Motility-associated genes are shared in both T. pallidum and B. burgdorferi, and an in-depth comparative analysis of these spirochetes may greatly enhance our understanding of the fundamental physiology of these important pathogens 5; 12.

T. pallidum has a spiral shape with a length ranging from 6 to 15 μm and a diameter of ~0.2 μm 11; 13; 14; 15; 16. The protoplasmic cylinder is surrounded by a cytoplasmic membrane, which is enclosed by a loosely associated outer membrane. A thin layer of peptidoglycan between the membranes provides structural stability while permitting flexibility. The flagella are located in the periplasmic space, between the cytoplasmic membrane and the outer membrane. Bundles of flagella originate at flagellar motors at both ends of the organism, wind around the flexible protoplasmic cell cylinder, and overlap in the middle. T. pallidum contains multiple chemotaxis genes encoding methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (MCPs)5. Treponema species also contains cytoplasmic filaments arranged in a ribbon configuration that spans the entire length of the cell 17; 18; 19; 20. cfpA, the gene encoding the ~79 kDa major subunit of the cytoplasmic filaments, is highly conserved in Treponema species. In T. denticola or T. phagedenis, mutation of cfpA results in defective cell division in which two or more cytoplasmic cylinders are encased in a single outer membrane 17. There are at least 46 putative lipoproteins in T. pallidum 21; other than the 47 kDa carboxypeptidase and multiple ABC transporter periplasmic binding proteins, the functions of these lipoproteins are largely unknown11. T. pallidum also has a paucity of integral membrane proteins in its outer membrane, and has been referred to as the “stealth pathogen” because of the scarcity of antigens on its outer surface 2; 22; 23.

Flagella play an essential role in the motility, morphology, and biology of spirochetes as well as other organisms 10. Flagellar structure and function have been extensively studied using E. coli and S. enterica as model systems. Flagellar motion is powered by a proton- or sodium ion-driven rotary motor embedded in the cytoplasmic membrane, but the precise mechanisms of flagellar motor rotation and reversal remain to be determined 24; 25; 26; 27; 28. The periplasmic flagellar assemblies of T. pallidum are expected to generally resemble those of external flagella, owing to the high degree of similarity between flagellar gene homologs. In recent years, progress has been made to understand the periplasmic flagella-driven motility of B. burgdorferi and other spirochetes 29. The motility of B. burgdorferi results from the coordinated asymmetric rotation of the flagella at both ends of the cell 30. The T. pallidum flagellar filaments are composed of several major proteins, including flagellar core proteins FlaB1, FlaB2 and FlaB3, and the sheath protein FlaA 31; 32; 33. However, the structural details of the periplasmic flagella remain unknown.

The cellular architectures of several spirochetes (including T. pallidum, T. primitia, T. denticola and B. burgdorferi) have been studied extensively using cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) analysis 34; 35; 36; 37. Cryo-ET has emerged as a 3-D imaging technique to visualize the cellular and subcellular structures at the molecular level 38; 39. The distinct advantage of cryo-ET is its potential to elucidate the structure of cellular components in situ without fixation, dehydration, embedding or sectioning artifacts. The power of cryo-ET has been significantly enhanced by 3-D subvolume averaging and classification techniques 40; 41; 42; 43. Recently, we used high throughput cryo-ET of B. burgdorferi to determine the molecular architecture of intact flagellar motor at 3.5 nm resolution 44.

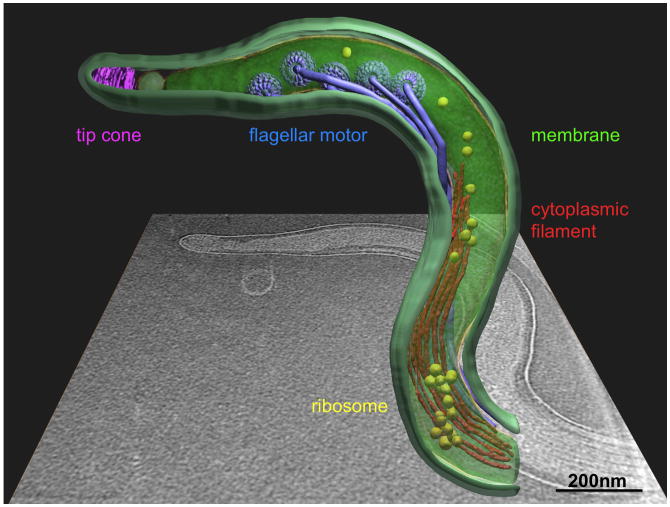

In this study, we investigated infectious T. pallidum organisms and their periplasmic flagella in situ utilizing high throughput cryo-ET. Cryo-ET reconstructions from 304 frozen-hydrated organisms in general support the recently published results of Izard et al.35, but provide significantly amount of novel structural information regarding the detailed structures of cell envelope, the localization of chemoreceptor arrays, and the molecular architecture of flagellar filament and motor in situ. Abundant lipoproteins studding the outer leaflet of the cytoplasmic membrane were visualized for the first time; the proteinaceous nature of this layer was verified by its dissolution following proteinase K treatment of partially disrupted organisms. A periplasmically located, cone-shaped structure was observed at the ends of each organism; this unique feature appears to be comprised of lipoproteins arranged in a helical lattice adjacent to the outer membrane. Furthermore, a comparative analysis of B. burgdorferi and T. pallidum provides insight into the common cellular structures of spirochetes and also exhibits some unique pathogenesis-related features of these two pathogens.

RESULTS

Cryo-ET of intact T. pallidum cells

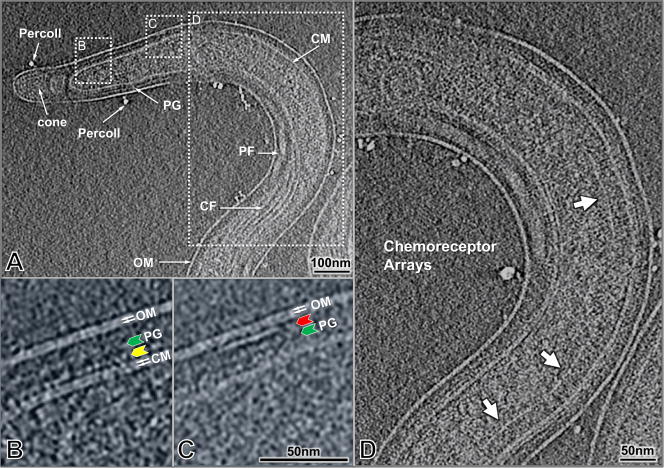

T. pallidum cells (n = 304) were imaged under optimal conditions to obtain high resolution structures using high throughput cryo-ET. Typically, the organism tapers from an approximate diameter of 0.2 μm to 0.1 μm near the end of the cell as shown in a representative image (Fig. 1A). Similar to B. burgdorferi and other spirochetes examined previously, the image from a T. pallidum cell (Fig. 1A) illustrates the outer membrane, the cytoplasmic membrane and a thin peptidoglycan layer, with the flagella wrapping around the cell body in the periplasmic space. Enlarged views (Figs. 1B,C) reveal the inner and outer leaflets of the lipid bilayer of both the outer and cytoplasmic membranes. The T. pallidum outer membrane appears as a simple lipid bilayer by cryo-ET. It therefore differs substantially from the outer membrane of B. burgdorferi, which has a contiguous external layer of density attributable to surface lipoproteins 44. In contrast, a contiguous layer of density associated with the outer surface of the cytoplasmic membrane was demonstrable in most cryo-ET sections of T. pallidum (Fig. 1B, yellow arrow). This layer was distinct from the more loosely arranged density located near the middle of the periplasm (Fig. 1B, green arrow), which represents the peptidoglycan layer. The punctuate nature of the cytoplasmic membrane-proximal density, along with frequent interconnections with the outer leaflet, suggests that this layer may represent periplasmic lipoproteins anchored to the cytoplasmic membrane (Fig. 1B, yellow arrow). In addition, there are small patches of proteins extending from the inner leaflet of the outer membrane (Fig. 1C, red arrow). The occasional dense particles observed outside the organism are residual Percoll particles from the T. pallidum purification procedure.

Figure 1.

Cellular architecture of an intact T. pallidum cell. (A) A typical tomographic slice near the center of the bacterium after 4×4 binning of the original reconstruction. The prominent structural features include the outer membrane, cytoplasmic membrane, peptidoglycan layer, periplasmic flagella, and cytoplasmic filaments (A). The outlined region on the left (A) is enlarged in (B) after 2×2 binning of the original reconstruction. The dotted outline on the right (A) is enlarged in (C). The two leaflets of the membranes are visible as indicated by white arrows. The extra layer of density adjacent to the cytoplasmic membrane is indicated by a yellow arrow, whereas the apparent peptidoglycan layer is shown by the green arrow. An example of a patch of density associated with the inner leaflet of the outer membrane is marked by the red arrow (C). Examples of structures resembling chemoreceptor arrays are visible in (D) (white arrows).

Putative Chemoreceptor arrays were directly visualized for the first time in T. pallidum organisms, as exemplified in Figure 1D. There are three arrays visible in this reconstruction. Their locations are variable, typically from 500 nm to 1000 nm away from the cell end. The width of arrays is also variable, however, the length of receptor (from a prominent line “base plate” to cell membrane) is relatively consistent ~27 nm. Although the detailed structure of the T. pallidum chemoreceptor array has not been determined yet, it appears to be similar to the characteristic structure of bacterial chemoreceptors observed to date 45.

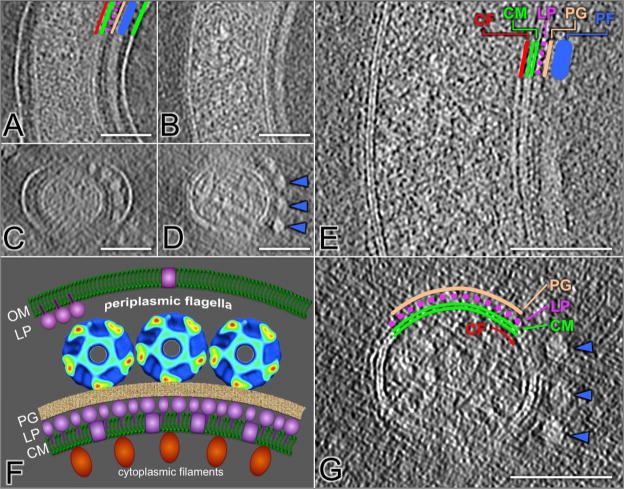

Characterization of Cell Envelope

The appearance of the cell envelope of T. pallidum is modulated by intertwining of the ribbon of periplasmic flagella. The space between cytoplasmic and outer membranes was typically ~23 nm, and became wider (up to 49 nm) in the vicinity of periplasmic flagella (the diameter is 20 nm) as shown in Figs. 2A,C. By repeated centrifugation and resuspension of T. pallidum, the outer membrane can be removed gently without disrupting the association between the flagella and the cell cylinder (Figs. 2B, D). Higher magnification views of this organism reveal the structural details around cytoplasmic membrane bilayer, which is visible as parallel densities spaced 4 nm apart (Figs. 2E, G). An array of cytoplasmic filaments lie just underneath the inner surface of the cytoplasmic membrane, as described in greater detail subsequently. There are two layers of densities in close proximity to the periplasmic side of the cytoplasmic membrane (Figs. 2E, G). The inner layer (colored as purple in Figs 2E,G) appears to consist of a discontinuous array of discrete particles that extend from the outer leaflet of the cytoplasmic membrane. This series of ‘studs’ was suggestive of a layer of proteins that are anchored to the cytoplasmic membrane, through either lipid moieties or hydrophobic amino acid domains. The more distal layer (colored as yellow in Figs 2E,G), which lies between the ‘stud’ layer and the periplasmic flagella, is more contiguous and appears to correspond to the peptidoglycan layer.

Figure 2.

The T. pallidum cell envelope architecture. The space between the outer and cytoplasmic membranes increases from ~23 nm to ~49 nm in regions containing the periplasmic flagella (A, C). The periplasmic flagella (blue line) remain closely associated with cell cylinder following removal of the outer membrane through repeated centrifugation (B, D). The 4 nm lipid bilayer composition of the cytoplasmic membrane is visible in higher magnification views (E and G). The locations of the cytoplasmic filaments (red line), lipoprotein layer (purple circles) and peptidoglycan (orange line) are indicated (E). A, B and E are longitudinal views, while C and D are the cross-section views. Most membrane proteins (colored in orange) are anchored to the cytoplasmic membrane (CM) just underneath the thin layer of peptidoglycan (PG). A model of T. pallidum cell envelope is shown in (F). Rare outer membrane proteins (colored in purple) are exposed on the outer membrane (OM).

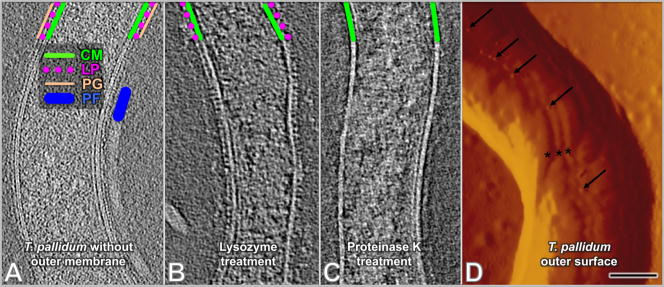

To delineate the composition of these cytoplasmic membrane-proximal layers, we partially disrupted T. pallidum cells by repeated centrifugation and resuspension to remove the outer membrane and thus provide access of periplasmic components to treatment with lysozyme or proteinase K (Fig. 3). In prior studies, it had been shown that repeated centrifugation and resuspension of Percoll-purified T. pallidum in distilled water resulted in blebbing and release of the outer membrane from the majority of cells 20. We thus treated cells in similar manner prior to addition of lysozyme or proteinase K. The suspected membrane protein and peptidoglycan layers, as well as periplasmic flagella and cytoplasmic filaments, were still clearly preserved in repeatedly centrifuged specimens (Fig. 3A). Following treatment with lysozyme, the proposed peptidoglycan layer was removed, whereas the layer of protusions proximal to the cytoplasmic membrane remained intact (Fig. 3B). In contrast, treatment with proteinase K resulted in complete removal of this cytoplasmic membrane-proximal ‘stud’ layer (Fig. 3C). This analysis confirmed the presence of a prominent layer of proteins next to the cytoplasmic membrane, followed by a thin peptidoglycan layer. We propose that the protein layer is comprised primarily of lipoproteins, given the abundance of lipoproteins in T. pallidum 5.

Figure 3.

Confirmation of T. pallidum peptidoglycan layer, cytoplasmic membrane surface proteins and rare outer surface proteins. Cells in all panels were previously treated with distilled water to remove the outer membrane and expose subsurface structures. (A) Cells without subsequent enzyme treatment. Locations of the cytoplasmic membrane (green line), surface proteins (purple circles), peptidoglycan (orange line) and a periplasmic flagellum (blue line) are shown. (B) With lysozyme treatment. The peptidoglycan layer was removed, whereas the putative lipoproteins (purple circles) are still visible on the outer surface of the cytoplasmic membrane (C) With proteinase K treatment, the layer of putative lipoproteins was removed. (D) Presence of intramembranous particles on the outer surface of T. pallidum, as revealed by scanning probe microscopy (SPM). Freshly prepared, Percoll-purified T. pallidum were applied to a mica surface, air-dried, and visualized by SPM. A portion of one T. pallidum cell is shown using the amplitude mode. Small protrusions are visible on the outer surface (arrows) and often are located on the bulge in the outer membrane created by the underlying periplasmic flagella (asterisks). Scale bar is 100nm.

Our cryo-ET studies corroborated numerous prior studies indicating that the T. pallidum outer membrane lacks proteins or other structures that extend from the membrane bilayer. The treponemal rare outer membrane proteins (also called TROMPs) that appear to represent integral membrane proteins were not readily visible by cryo-ET. To further examine the T. pallidum surface structure, freshly prepared T. pallidum were applied to a mica surface, air-dried, and analyzed using scanning probe microscopy (SPM), a technique that provides high-resolution 3-D images of surface topology46. SPM revealed the presence of occasional protrusions (marked by arrows) on the T. pallidum cell surface (Fig. 3D). Some of these protrusions were located in the outer membrane overlying the periplasmic flagella (asterisks). These protrusions (~8 nm in diameter) appear to correspond to T. pallidum rare outer membrane proteins, identified previously as ~11 nm intramembranous particles by freeze fracture microscopy 15; 16; 47. As noted previously, these densities tend to overlie the periplasmic flagella, visible as three ridges (marked with asterisks) in Fig. 3D. The protrusions are structurally distinct from the much larger and randomly distributed Percoll particles shown in Fig. 1.

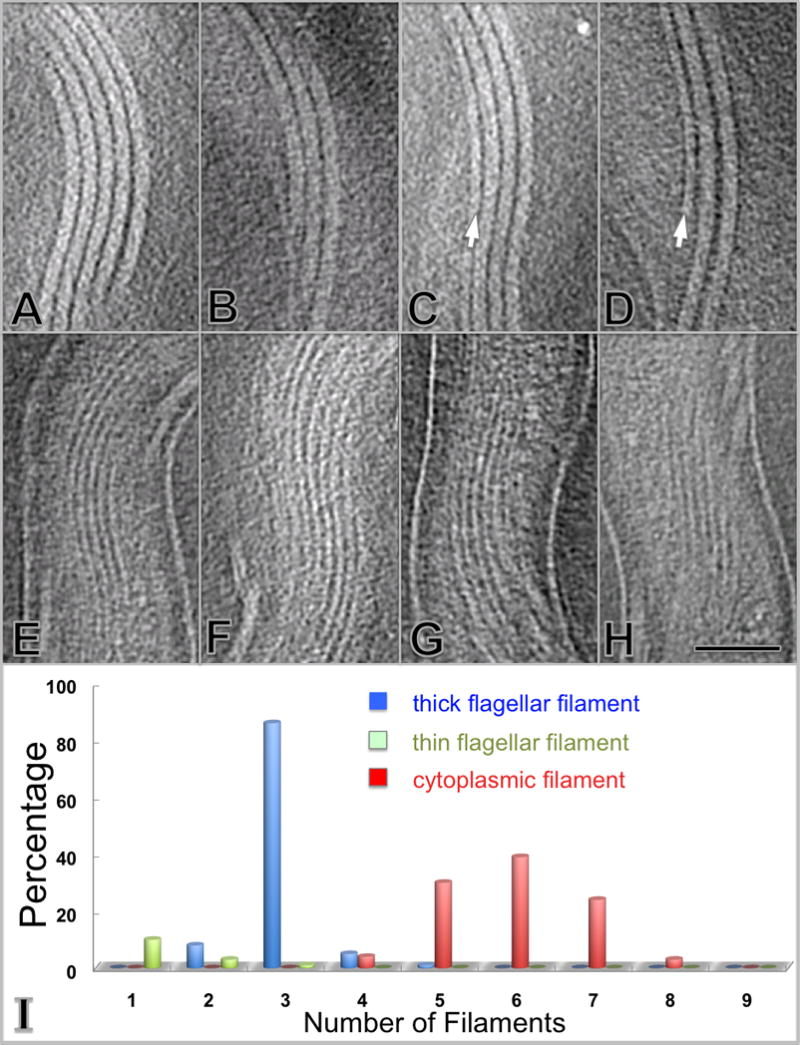

Periplasmic flagella

The flagellar filaments extend from each flagellar motor and are clearly localized between the peptidoglycan layer and the outer membrane (Figs. 2A,B). The diameter of the filament is approximately 20 nm. Flagellar filaments typically form a parallel array (Figs. 4A, B, C and D), with each filament becoming associated with the others beyond the hook region. The center-to-center distance between two filaments is slightly larger than 20 nm. Most bacteria (86%) exhibited three flagella at each end of the organism, although a few had two or five (Figs. 4A, B and I). Thin filaments were also visible in approximately one out of eight cells (Figs. 4C, D and I). The diameter of these thin filaments was ~13 nm, in contrast with the 20nm ‘thick’ flagellar filament. Each of the ‘standard’ 20 nm flagellar filaments was connected with an intact flagellar motor (Fig. S1), whereas the ‘thin’ filaments examined were not obviously associated with flagellar motors or any other discernable molecular assembly. Immunogold labeling of periplasmic flagella from partially disrupted organisms of T. pallidum demonstrated that FlaA antibodies bind to the surface of thick filaments, while FlaB1 antibodies bind preferentially to the thin filaments (Fig. S2). Therefore the thick filaments (20nm in diameter) are likely composed of FlaB in the core and FlaA on the surface, whereas thin filaments (13nm in diameter) are apparently comprised of FlaB subunits.

Figure 4.

Morphology and distribution of the periplasmic flagella and cytoplasmic filaments. The flagella form a side-by-side ribbon that wraps around the protoplasmic cylinder in a right-handed fashion (A–D). The diameter of flagella is ~20 nm. In addition, a thin periplasmic filament is occasionally associated with the flagellar ribbon (C, D), as indicated by a white arrow. The diameter of the thin filament is ~13 nm. Cytoplasmic filaments (E–H) form a ribbon-type structure located within the protoplasmic cylinder. The cytoplasmic filaments are parallel with the periplasmic flagella. The scale bar is 100 nm. The number of filaments per cell is depicted in (I) and is based on the cryo-ET analysis of 304 cells. The number of flagellar filaments is narrowly distributed, with a large majority (86%) of cells possessing three flagella per cell end (blue). The number of cytoplasmic filaments is distributed in a slightly larger range from 4 to 8 (red). The thin periplasmic filaments exist at a low frequency (about one out of eight cells) and 1–3 thin filaments are visible in these organisms (light green).

Cytoplasmic filaments

The cytoplasmic filaments form a ribbon (Figs. 4E, F, G and H) underneath the cytoplasmic membrane with a width of 7.0 to 7.5 nm. The distance between the filaments is about 13.0 nm. The number of cytoplasmic filaments ranges from 4–8 per cell, but most cell sections contain 6 filaments (Fig. 4I). The 3D reconstructions of different regions of the cell body indicated that the cytoplasmic filament ribbon runs parallel to the periplasmic flagella ribbon, separated by the cytoplasmic membrane and the peptidoglycan layer (Fig. 2F).

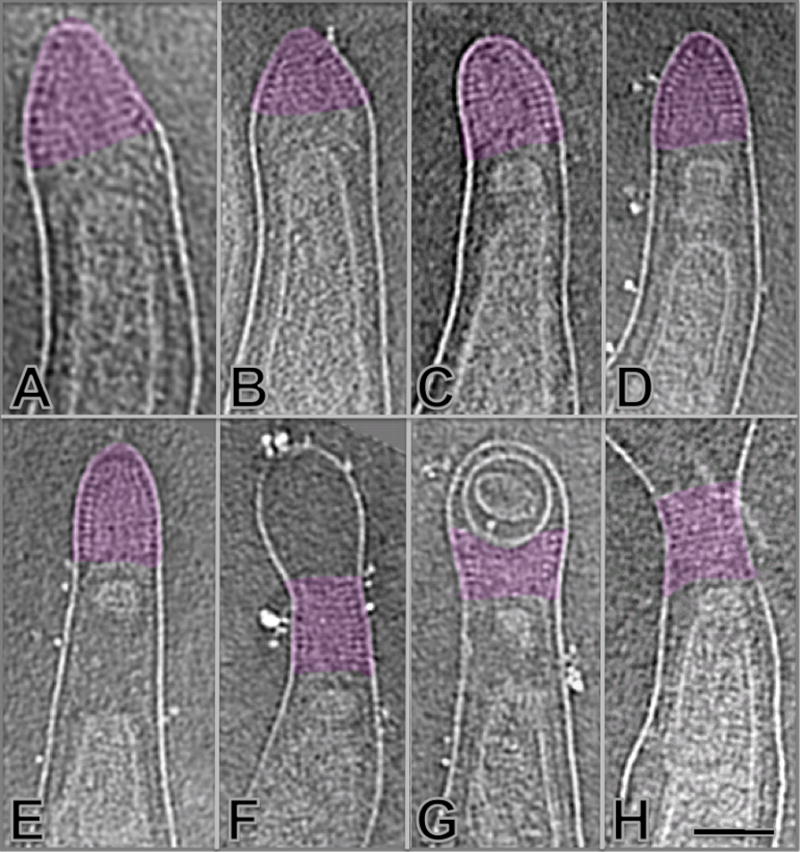

Cone-shaped structure

A periplasmically located, cone-shaped structure was found at the end of every organism (highlighted in purple in Fig. 5). The cone-shaped structure is located adjacent to the outer membrane and sometimes 100 nm away from the cytoplasmic membrane (Figs. 5D and E). It appears that one or more proteins (most likely including at least one lipoprotein) form a helical or ring-shaped lattice along the inner surface of the outer membrane, with a longitudinal spacing of ~5 nm between neighboring lattices. The inner portion of the cone structure was relatively amorphous with no clear arrangement of densities..

Figure 5.

Cone-shaped structures located at the ends of T. pallidum. A helical or ring-shaped array forms the outer surface of a cone-shaped structure (highlighted in purple) at both ends of the organism (A–H). It appears that the structure is likely associated with the outer membrane. Membrane-delimited vesicles are sometimes localized distal or (more commonly) proximal to the cone. The scale bar is 100 nm.

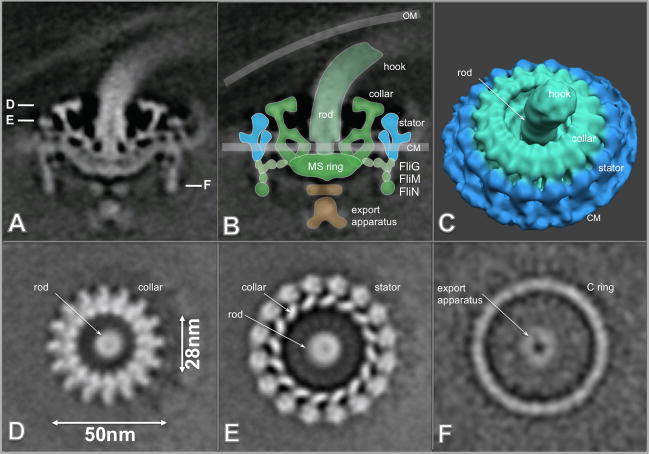

Molecular architecture of the intact flagellar motor

Typically, three flagellar motors are located at each end of the bacterium (Fig 4I). In individual tomograms, an architecture resembling a bowl-shaped structure surrounding a central rod could be discerned (Figs. S1 B,D). A 3-D reconstruction of the intact flagellar motor without imposed symmetry was obtained from the subvolume alignment and averaging of 830 motors. A central section of the resulting 3-D construct illustrates the locations of the putative hook, rod, MS ring, stator, C ring and export apparatus structures (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

Molecular architecture of the intact flagellar motor. (A) Center section of an asymmetric 3-D average structure of the flagellar motor. B is a flagellar model overlaid on the image in A. C is the surface rendering of the flagellar motor structure (the rotor is colored in green and the stator is colored in cyan). (D–F) are horizontal cross sections through a flagellar motor. Section (D) is located near the top of the motor, and the central rod and the uppermost portion of the rotor are visible. Section (E) transects the middle of the rotor body and the stator, just above the cytoplasmic membrane. The bottom of the C ring is visible in section (F). A portion of the export apparatus is visible in the center of the C ring. The scale bar is 50 nm.

The hook structure is visible at the top, attached to the central rod. The rod has a central channel as noted in the flagellar motor from B. burgdorferi 44. The 16-fold symmetry of the outer portion of the upper region of the motor is clearly evident in the cross sections shown in Figs. 6D and E. The centrally located export apparatus is visible on the cytoplasmic side of the MS ring (Figs. 6A, F). The most peripherally located elements of the motor (colored with cyan in surface view of the T. pallidum flagellar motor as shown in Fig. 6C) are thought to represent the stator, which is composed of the membrane-associated proteins MotA and MotB and is embedded in the cytoplasmic membrane (Fig. 6B, C). Overall, the structure of the T. pallidum flagellar motor closely resembles those of B. burgdorferi 44 and T. primitia 48.

Differences do exist between the T. pallidum and B. burgdorferi structures. In the T. pallidum motor, the top of the collar extends further inward toward the rod, such that the ‘opening’ of the collar is ~28 nm; by comparison, the opening for the B. burgdorferi collar is ~38 nm 44. In addition, the T. pallidum rotor lacks the torus-shaped ring corresponding to FlgI in B. burgdorferi; this result is consistent with the absence of flgI in the T. pallidum genome 5. A model of the relative locations of the stator and rotor of the T. pallidum flagellar motor (Fig. 6B) is proposed based on comparisons with that of B. burgdorferi 44.

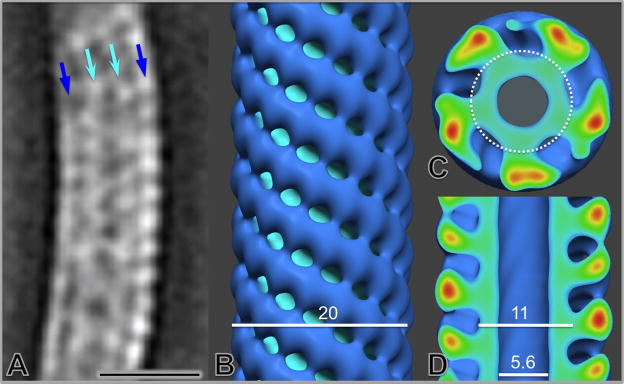

Structural characterization of periplasmic flagella

We also carried out a structural characterization of the thick flagellar filament in situ. The density maps corresponding to segments of the flagella were aligned to generate the first averaged flagellar filament structure, which revealed its native helical curvature and the characteristic presence of central and outer layers of density (Fig. 7A). The curved filament structure was ‘straightened’ to permit longitudinal helical averaging (Figs. 7B, C, D). The resulting structure revealed a central channel, an inner cylinder of density, and external chains of density in a left-handed five-start helical lattice with a pitch of 6 nm. The central channel and inner cylinder have diameters of 5.6 nm and 11 nm respectively (Fig. 7D), whereas the overall diameter of the flagellum is 20 nm. The outer sheath is connected to the core by a narrow region of density, and is composed of subunits with a periodicity of 5 nm. The inner core appeared to be comprised of 5 regions of density in each cross section (Fig. 7C); these substructures were tightly arranged in a stacked helical array. Based on our antibody labeling experiments (Fig. S2) and prior studies 31; 49, the inner ‘core’ (inside the circle outlined in Fig. 7) is likely comprised of FlaB subunits, and the outer ‘sheath’ is composed of FlaA.

Figure 7.

Structural characterization of periplasmic flagella in situ. A single slice from the averaged map of periplasmic flagella (thick filament) segments illustrates the curved configuration of their superhelical conformation (A). After mathematical ‘straightening’ of the superhelical curvature, the refined structural model of the periplasmic flagella in the surface view (B) and center sections (C and D) reveals the central channel, the filament core and its surrounding protein sheath. The scale bar is 20 nm.

DISCUSSION

The pathogenesis of T. pallidum is poorly understood at the molecular level, in part due to the inability to culture the organism continuously in vitro. Consequently, innovative approaches are needed to study the fundamental biology of this enigmatic spirochete. Cryo-ET is well suited for the elucidation of 3-D cellular architecture of intact organisms at the molecular level. We are able to achieve high resolution 3-D reconstructions of intact organisms at the optimal imaging conditions, such as the use of relatively low defocus levels and a small objective aperture. Volume binning of the 3-D reconstructions provided additional contrast for visualization of minute structures, including the leaflets in membrane bilayers and layers of membrane-associated proteins.

Unique envelope architecture

The cell envelope of T. pallidum has been studied extensively using a variety of techniques, but remains poorly understood. The high resolution cryo-tomographic reconstructions in this study revealed an unprecedented structural detail of the cell envelope. The 4 nm lipid bilayer of both outer and cytoplasmic membranes was resolved by cryo-ET, and provided an important marker for the understanding of membrane-associated structures. The outer membrane of T. pallidum appears as a simple lipid bilayer, whereas the external surface of the B. burgdorferi outer membrane has a clearly visible proteinaceous layer 44. The T. pallidum outer membrane can be removed by centrifugation, suggesting a loose association of this pliable membrane with the underlying structures.

Prior freeze fracture electron microscopy studies had shown the presence of rare intramembranous particles in the outer membrane, indicating a paucity of membrane-spanning proteins 15; 16; 47. We were able to confirm the previously described presence of these treponemal rare outer membrane proteins (TROMPs) using SPM, a technique that is complement to cryo-ET and provides surface topology of the outer membrane (Fig. 3D). The putative outer membrane proteins appeared to be preferentially distributed over the flagella. We also identified patches of density near the inner surface of the outer membrane, as shown in Fig. 1C (red arrow). These patches may be comprised of lipoproteins that are anchored to the inner leaflet of the outer membrane, as has been described for TP453 by Hazlett et al. 51. Our data also indicate that the putative lipoprotein layer is closely associated with cytoplasmic membrane, and that the thin peptidoglycan layer lies between this layer of lipoproteins and the periplasmic flagella (Fig. 2F). The space between cytoplasmic and outer membranes was wider in the vicinity of periplasmic flagella, as reported in previous studies of T. pallidum, T. denticola, T. primitia and B. burgdorferi 34; 35; 36; 37; 54. Together, these structural details help to clarify the previous cell envelope model proposed by Cox et al. 52; 53. The unique surface architecture of T. pallidum is consistent to its remarkable ability to evade the host immune response 50.

In a recent reanalysis of spirochetal lipoprotein genes, Setubal et al. 21 estimated that the T. pallidum genome contains 46 genes encoding putative lipoproteins, as compared to 127 predicted lipoprotein genes in B. burgdorferi. B. burgdorferi has an abundance of lipoproteins anchored on the outer membrane surface, as verified in our previous tomographic studies 44. However, there is currently no definitive evidence for the surface localization of any T. pallidum lipoproteins 55; 56; 57; 58. Several T. pallidum proteins have been postulated to be surface exposed, based on ligand and/or antibody binding to intact organisms; these candidates include the laminin-binding protein TP0751, the fibronectin- and laminin-binding protein TP0136 58, Tp92, and TprK, a protein that induces opsonic antibodies, undergoes sequence variation, and may promote immune evasion 50; 59. Continued investigation of the T. pallidum outer membrane remains critical for an improved understanding of the organism’s host-pathogen interactions, as well as for the potential development of vaccines against syphilis 60.

Unique structure and function of periplasmic flagella

Spirochetes possess periplasmic flagella that confer the ability to effectively translocate in highly viscous gel-like media conditions that would normally hinder other bacteria with external flagella 10. Unlike most external flagellar filaments, which are composed of a single flagellin subunit, the flagellar filament of T. pallidum consists of multiple proteins: FlaB1, FlaB2, FlaB3 and FlaA. Here we provided the first ultrastructure of periplasmic flagella by 3-D averaging of the native flagellar filaments (Fig. 7). The flagellar filament structure of the T. pallidum appears significantly different from the well known external flagellar filament structures from S. enterica 61 and the more recent reconstruction from C. jejuni 62. The major components of T. pallidum flagellar filaments (FlaB1, FlaB2, and FlaB3) are homologous to the N- and C-terminal regions of the flagellins of S. enterica and E. coli, but its molecular weight is much smaller due to the lack of an ~200 residue domain in the central region of the enteric flagellin sequences 11. This domain forms an extension out of the filament core in S. enterica 61; this portion of the structure is thus presumed to be absent in the T. pallidum flagellar structure.

Prior studies had shown that FlaA forms an external sheath on the T. pallidum flagellar filament, whereas FlaB1, FlaB2, and FlaB3 form the central core 31; 49. Our 3-D reconstruction of the T. pallidum flagellar filament in situ (Fig. 7) revealed a central channel surrounded by a core and an outer array of helically arranged subunits; this structure thus corresponds well with previous findings. The central channel has a diameter of 5.6 nm. A similar channel has been identified in all bacterial flagella examined, and is required for the transport of subunits to the flagellar tip during assembly 61. Our current structural model lacks sufficient detail to determine the arrangement of the FlaB subunits within the core. Cross-sections of the model (Fig. 7D) indicate that the filament core (~11 nm in diameter) consists of five regions of density surrounding the central channel; these densities may correspond to individual FlaB polypeptides. Chains of subunits on the outer surface of the flagellum appear to be attached to the core subunits via a narrow stem, and thereby follow the helical arrangement of the core. Our data indicate that these chains of subunits represent the outer sheath comprised of FlaA. Li et al. 63 performed elegant genetic studies in an attempt to delineate the structural roles of the three FlaB proteins and the FlaA subunit of Serpulina hyodysenteriae, which has a similar flagellar structure. A S. hyodysenteriae flaA mutant had flagellar filaments with a diameter of 14.8 nm, as compared to a filament diameter of 21 nm in wild type organisms. This result thus correlates well with our model, with allowance for differences in subunit sizes and measurement methods. In the S. hyodysenteriae studies 63, absence of either FlaB1 or FlaB2 resulted in reduced motility and altered the pitch and diameter of the flagellum ‘superhelix’. When both genes were mutated, the organisms were nonmotile; purified filaments had lost their superhelical shape, and were comprised almost entirely of FlaA with little associated FlaB3. Mutations in flaB3 caused relatively little disruption of flagellar structure and function, indicating that FlaB3 is not essential for flagellar filament assembly.

Typically, three periplasmic flagella form a ribbon at each end of T. pallidum as they wrap around the cytoplasmic body in right-handed fashion (Fig. 8). Similar results reported in both B. burgdorferi and T. denticola 34; 54 suggest that spirochetes may share similar architecture of flagella or even similar mechanisms of flagellar rotations. In addition to regular flagellar filaments with a 20 nm diameter, we found that a small proportion of T. pallidum cells possessed thin, 13 nm filaments. Immunoelectron microscopy (Fig. S2) demonstrated that these thin filaments are comprised of FlaB core proteins and appear to lack the sheath component FlaA. While the 20 nm flagella were consistently observed to be connected to motors via a hook structure, the thin filaments did not appear to be associated with flagellar motors. One possibility is that these thin filaments are comprised of ‘excess’ FlaB subunits that are secreted into the periplasmic space and undergo self-assembly.

Figure 8.

Cellular architecture of intact T. pallidum at molecular level. One central slice of a tomographic reconstruction from one organism is shown in the background. A 3-D model was generated by manually segmenting the outer membrane (light green), cytoplasmic membrane (green), flagellar filaments (blue), cytoplasmic filament (red), cone-shaped structure (magenta) and a large macromolecular complex (yellow). Averaged structures of the flagellar motor were computationally mapped back into their cellular context.

In examining B. burgdorferi by cryo-ET, Charon et al.54 hypothesized that interactions between the flagellar ribbon and the cell cylinder (with peptidoglycan at its outer surface, Fig. 2F) gives rise to the formation of the backward migrating wave in the cell body, thus imparting the characteristic serpentine movement of spirochetes. Cryo-ET of T. pallidum provides a detailed model of cell envelope with the presence of periplasmic flagella, suggesting that peptidoglycan layer not only maintains the integrity of cell cylinder, but also serves as the interface between the rotating flagella and cell cylinder. Without the peptidoglycan layer, the fragile cell body of T. pallidum and other spirochetes would not be able to withstand the friction and torque produced by rapid flagellar rotation.

Spirochetal flagellar motor

The T. pallidum flagellar motors are anchored in the cytoplasmic membrane at each end of the cell cylinder, and are arranged in a row such that the flagellar hooks are pointing toward the middle of the organism (Fig. 8). The flagellar motor operons of T. pallidum contain at least 25 genes, most of which are highly homologous to those of B. burgdorferi and other spirochetes 64. The flagellar motors of T. pallidum (Fig. 6), T. primitia 48, and B. burgdorferi 44 are remarkably similar in their global architecture. One obvious difference is lack of a P ring in the T. pallidum and T. primitia motors. This result is consistent with the absence of a flgI ortholog in the T. pallidum genome 5. Clearly, the P ring is not required for motility in T. pallidum and T. primitia, and previous analyses of flgI mutants indicated that the P ring is not required for flagellar rotation in B. burgdorferi 44. In these spirochetes, a collar associated with the rotor forms a characteristic bowl-shaped structure that may replace the putative role of FlgI as a ‘bearing’ that interacts with the surrounding peptidoglycan layer 44; 48. The collar of the T. pallidum motor has a smaller opening than the other two spirochetal flagellar motors, which may reflect differences in both protein composition and function. There is currently a lack of information regarding this unique bowl-shaped structure and its function, which may be addressed by additional structural analyses, coupled with gene disruption or labeling studies in genetically tractable organisms such as B. burgdorferi, S. hyodysenteriae, and T. denticola 44; 63; 65.

The morphology of cytoplasmic filament ribbon

The cytoplasmic filaments of T. pallidum form a ribbon-like structure, typically composed of 4–8 filaments anchored to the inner surface of the cytoplasmic membrane. The ribbon likely extends the length of the cell as reported in T. denticola and T. phagedenis 18. The cytoplasmic filaments of several spirochetes have been purified 20; 66; 67. The major component of the cytoplasmic filament is 79 kDa CfpA, which is highly homologous among the treponemes 66. Based on studies employing T. denticola strains in which cfpA was disrupted, it has been proposed that the cytoplasmic lament ribbon may be involved in the cell division process, structural integrity, motility, and/or chromosome structure and segregation in Treponema 11; 17; 19. However, the exact role of cytoplasmic filaments particularly in T. pallidum requires further investigation.

Cone-shaped structure

Cryo-ET of T. pallidum in this report and another recently published article by Izard et al. 35 revealed the presence of a previously unrecognized cone-shaped structure located at both ends of the organism (Fig. 5). Several types of ‘periplasmic cone’ or ‘patella-like’ structures have been reported previously in T. primitia and T. denticola 34; 37. Images of the T. pallidum cone-shaped structure reported here (Fig. 5) provide additional architectural details and indicate that it is located outside of the peptidoglycan layer, and is associated with the outer membrane near the end of the cell. Discrete, regularly spaced densities on the outer surface of the cone structure follow the contour of the outer membrane and appear to represent either rings or a helical array of a putative, as yet unidentified protein. The central region of the cone is more amorphous in appearance, indicating that its composition may be different than the outermost aspect of the cone. The association of the cone structure with the outer membrane as opposed to the cytoplasmic membrane is demonstrated by its occasional distant localization relative to the end of the cytoplasmic cylinder (e.g. Fig. 5E). What appear to be small cytoplasmic membrane vesicles are often present between the cone-shaped array and the end of the cytoplasmic cylinder. While most commonly located at the cell end, the cone structure is sometimes separated from the end by an outer membrane bleb or internal membrane vesicles (Figs. 5F, G). The function and composition of the cone structure in this and other spirochetes is currently unknown. One can speculate that the cone (colored in purple of Fig. 8) may have extensions across the outer membrane and be involved in adherence or sensory functions; however, studies of the resident protein(s) and/or other components and their properties are needed to elucidate possible roles of this unique and fascinating structure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics Statement

All procedures involving rabbits were reviewed and approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Cryo-ET of intact T. pallidum

T. pallidum subsp. pallidum Nichols was extracted from rabbit testes after intratesticular infection; in some experiments, the organisms were further purified by Percoll density gradient centrifugation as described previously 20. Freshly prepared, motile T. pallidum was centrifuged and resuspended in 20 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a final concentration ~2×109 cells/ml. After mixing with 15 nm gold clusters, 4 μl T. pallidum samples were deposited onto freshly glow-discharged holey carbon grids for 1 min. The grids were blotted with filter paper and rapidly frozen in liquid ethane maintained at −180°C using a gravity-driven plunger apparatus as previously described 44. The resulting frozen-hydrated specimens were imaged at −170 °C using a Polara G2 electron microscope (FEI Company) equipped with a field emission gun and a 4K × 4K CCD (16 megapixel) camera (TVIPS; GMBH, Germany). The microscope was operated at 300 kV with a magnification of 31,000×, resulting in an effective pixel size of 2.8 Å. Using the FEI “batch tomography” program, low dose single-axis tilt series were collected from each bacterium at −4 to −6 μm defocus with a cumulative dose of ~100 e−/Å2 distributed over 65 images, covering an angular range from −64° to +64°, with an angular increment of 2°. A 30 μm objective aperture and 2×2 binning of pixels was used to enhance the image contrast at this defocus level. Tilted images were initially aligned with respect to each other using fiducial markers and the IMOD software package 68. After further refinement using projection-matching, 3-D tomograms were reconstructed using weighted back-projection implemented in the package Protomo 69. In total, 304 cryo tomograms from T. pallidum cells were reconstructed. The effective pixel size of the tomographic reconstructions is 5.6 Å, and the effective in-plane resolution is better than 4 nm, based on the direct separation of lipid bilayers. 2×2×2 binning of these tomograms was used for the visualization of 3-D images and the preparation of figures.

Outer membrane removal, surface proteolysis and lysozyme treatment

Percoll-purified T. pallidum organisms in PBS (~1 × 109) were centrifuged at 21000 × g for 1 m, resuspended in 500 μl PBS with 5 mM MgCl2, and pipetted vigorously ~20 times. This process was repeated, As a result of this treatment, the outer membrane was removed from the majority of T. pallidum organisms. Surface proteolysis was carried out on this preparation by treatment with Proteinase K (0.4 mg/ml) for 40 m at ambient temperature as described in 44. The same preparation was treated in parallel with lysozyme (0.6 mg/ml).

Immunogold labeling of flagellar filaments

Percoll-purified T. pallidum cells partially disrupted by repeated centrifugation as described above were applied to carbon coated grids and incubated with PBS containing 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 min, followed by washing with PBS-5% BSA. Grids were placed on a 30 ul drop of primary rabbit antisera against either FlaA or FlaB1 32 diluted 1:20 in PBS-5% BSA for 60 m, followed by washing again with PBS-5% BSA three times. The samples were stained with gold goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Jackson ImmunoResearch) diluted 1:20 in PBS-5% BSA for 60 m followed by washing in PBS with 2% BSA. The grids were washed with water before staining with 1% uranyl acetate. Samples were viewed in a JEM1200 electron microscope.

Subvolume averaging of flagellar motor and filament

The subvolume processing of flagellar motors was carried out as described in 44. Briefly, the positions and orientations of each flagellar motor in each tomogram were determined manually. Subvolumes (256×256×256 voxels) containing entire flagellar motors were extracted from the original tomograms. In total, 830 flagellar motor volumes were extracted from 273 tomograms and were further used for 3-D alignment, classification and averaging. The resolution of the flagellar motor structure is 4.0 nm based on the Fourier shell correlation (cutoff 0.5).

A total of 4,166 segments (192×192×96 voxels) of flagellar filaments were manually identified and extracted from 55 reconstructions. The initial orientation was determined by using two adjacent points along the filament. The first one is proximal to the flagellar hook, and the polarity of the filament was preserved during the alignment process. After obtaining the asymmetric reconstruction of the flagellar filament, the helical symmetry of the short segment was determined and imposed. The helical model was then used as the reference for further 3-D alignment and averaging.

3-D Visualization

Tomographic reconstructions were visualized using IMOD 68 and surface rendering of flagellar structures was carried out with the software package UCSF Chimera 70. Reconstructions of several T. pallidum organisms were segmented manually using 3-D modeling software Amira (Visage Imaging). 3-D segmentation of the flagellar filaments, cytoplasmic filaments, outer and cytoplasmic membranes, and unique cone-shaped structure were manually constructed. The surface model from the averaged flagellar motor was computationally mapped back into the original cellular context as described 71.

Scanning Probe Microscopy

SPM was carried out using a Digital Instruments/Veeco MultiMode™ instrument equipped with a Nanoscope IIIa SPM controller. A cantilever probe with a spring constant of 40 N/m and an inherent resonance (f0) of ~300 kHz was used. Freshly extracted T. pallidum (6 × 106/ml) in PBS was centrifuged at 500×g for 5 min to remove host cell debris and fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde. A 10 μl sample was applied to a mica support and air dried. The specimen was rinsed 3 times with distilled water and air dried prior to SPM. Scanning was performed in the tapping mode with a scan rate of 1 line/sec.

Supplementary Material

The T. pallidum periplasmic flagella and flagellar motor in situ. The flagella are located in the periplasmic space, while the motors are embedded in the cytoplasmic membrane. (A) and (C) are two organisms with the two most frequently observed morphologies - curved and straight. (B) and (D) are enlarged views of (A) and (C), respectively. White arrows indicate the location of a flagellar motor. Black arrows indicate the location of periplasmic flagella. Only one or two motors are visible in each tomogram section. The scale bar is 100nm.

Thin flagellar filaments lack the FlaA surface layer. Flagellar filaments were released from cells by repeated centrifugation and resuspension prior to immunogold labeling. (A and C) Immunolabeling with rabbit anti-FlaA antiserum. 12nm gold particles were primarily attached to 20nm thick flagellar filaments after FlaA antibody labeling. Few gold particles were associated with 14 nm thin flagellar filaments. (B) Labeling with rabbit anti-FlaB1 antiserum. Gold particles were mainly attached to thin filaments after anti-FlaB1 antibody treatment. (D) Control without primary antibody.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. James K. Stoops, Angel Paredes, Hanspeter Winkler and Douglas Botkin for their comments and suggestions. We also want to thank Matthew Swulius for advice and assistance with immunogold labeling. This work was supported in part by Welch Foundation Grant AU-1714 and NIH grant 1R01AI087946 (to J. L.). Maintenance of the Polara electron microscope facility is supported by the Structural Biology Center at the UT Houston Medical School.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gerbase AC, Rowley JT, Heymann DH, Berkley SF, Piot P. Global prevalence and incidence estimates of selected curable STDs. Sex Transm Infect. 1998;74(Suppl 1):S12–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lafond RE, Lukehart SA. Biological basis for syphilis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:29–49. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.1.29-49.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galvin SR, Cohen MS. The role of sexually transmitted diseases in HIV transmission. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:33–42. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norris SJ, Paster BJ, Moter A, Gobel UB. SpringerLink (Online service) The Genus Treponema. In: Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer K-H, Stackebrandt E, editors. The Prokaryotes Volume 7: Proteobacteria: Delta, Epsilon Subclass. Springer-Verlag; New York, NY: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fraser CM, Norris SJ, Weinstock GM, White O, Sutton GG, Dodson R, Gwinn M, Hickey EK, Clayton R, Ketchum KA, Sodergren E, Hardham JM, McLeod MP, Salzberg S, Peterson J, Khalak H, Richardson D, Howell JK, Chidambaram M, Utterback T, McDonald L, Artiach P, Bowman C, Cotton MD, Fujii C, Garland S, Hatch B, Horst K, Roberts K, Sandusky M, Weidman J, Smith HO, Venter JC. Complete genome sequence of Treponema pallidum, the syphilis spirochete. Science. 1998;281:375–88. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5375.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matejkova P, Strouhal M, Smajs D, Norris SJ, Palzkill T, Petrosino JF, Sodergren E, Norton JE, Singh J, Richmond TA, Molla MN, Albert TJ, Weinstock GM. Complete genome sequence of Treponema pallidum ssp. pallidum strain SS14 determined with oligonucleotide arrays. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:76. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norris SJ, Edmondson DG. Factors affecting the multiplication and subculture of Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum in a tissue culture system. Infect Immun. 1986;53:534–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.3.534-539.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steere AC, Coburn J, Glickstein L. The emergence of Lyme disease. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1093–101. doi: 10.1172/JCI21681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levett PN. Leptospirosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:296–326. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.2.296-326.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charon NW, Goldstein SF. Genetics of motility and chemotaxis of a fascinating group of bacteria: the spirochetes. Annu Rev Genet. 2002;36:47–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.36.041602.134359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norris SJ. Polypeptides of Treponema pallidum: progress toward understanding their structural, functional, and immunologic roles. Treponema Pallidum Polypeptide Research Group. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:750–79. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.750-779.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraser CM, Casjens S, Huang WM, Sutton GG, Clayton R, Lathigra R, White O, Ketchum KA, Dodson R, Hickey EK, Gwinn M, Dougherty B, Tomb JF, Fleischmann RD, Richardson D, Peterson J, Kerlavage AR, Quackenbush J, Salzberg S, Hanson M, van Vugt R, Palmer N, Adams MD, Gocayne J, Weidman J, Utterback T, Watthey L, McDonald L, Artiach P, Bowman C, Garland S, Fuji C, Cotton MD, Horst K, Roberts K, Hatch B, Smith HO, Venter JC. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature. 1997;390:580–6. doi: 10.1038/37551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson RC, Ritzi DM, Livermore BP. Outer envelope of virulent Treponema pallidum. Infect Immun. 1973;8:291–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.8.2.291-295.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hovind-Hougen K. Determination by means of electron microscopy of morphological criteria of value for classification of some spirochetes, in particular treponemes. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand Suppl. 1976:1–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walker EM, Zampighi GA, Blanco DR, Miller JN, Lovett MA. Demonstration of rare protein in the outer membrane of Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum by freeze-fracture analysis. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5005–11. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.5005-5011.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radolf JD, Norgard MV, Schulz WW. Outer membrane ultrastructure explains the limited antigenicity of virulent Treponema pallidum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:2051–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.6.2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Izard J. Cytoskeletal cytoplasmic filament ribbon of Treponema: a member of an intermediate-like filament protein family. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;11:159–66. doi: 10.1159/000094052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Izard J, McEwen BF, Barnard RM, Portuese T, Samsonoff WA, Limberger RJ. Tomographic reconstruction of treponemal cytoplasmic filaments reveals novel bridging and anchoring components. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:609–18. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Izard J, Samsonoff WA, Limberger RJ. Cytoplasmic filament-deficient mutant of Treponema denticola has pleiotropic defects. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:1078–84. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.3.1078-1084.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.You Y, Elmore S, Colton LL, Mackenzie C, Stoops JK, Weinstock GM, Norris SJ. Characterization of the cytoplasmic filament protein gene (cfpA) of Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3177–87. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3177-3187.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Setubal JC, Reis M, Matsunaga J, Haake DA. Lipoprotein computational prediction in spirochaetal genomes. Microbiology. 2006;152:113–21. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28317-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radolf JD. Role of outer membrane architecture in immune evasion by Treponema pallidum and Borrelia burgdorferi. Trends Microbiol. 1994;2:307–11. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(94)90446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radolf JD, Desrosiers DC. Treponema pallidum, the stealth pathogen, changes, but how? Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:1081–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06711.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berg HC. The rotary motor of bacterial flagella. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:19–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macnab RM. How bacteria assemble flagella. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:77–100. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kojima S, Blair DF. The bacterial flagellar motor: structure and function of a complex molecular machine. Int Rev Cytol. 2004;233:93–134. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(04)33003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sowa Y, Berry RM. Bacterial flagellar motor. Q Rev Biophys. 2008;41:103–32. doi: 10.1017/S0033583508004691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Terashima H, Kojima S, Homma M. Flagellar motility in bacteria structure and function of flagellar motor. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2008;270:39–85. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(08)01402-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldstein SF, Li C, Liu J, Miller M, Motaleb MA, Norris SJ, Silversmith RE, Wolgemuth CW, Charon NW. The Chic Motility and Chemotaxis of Borrelia burgdorferi. In: Samuels DS, Radolf JD, editors. Borrelia: Molecular Biology, Host Interaction and Pathogenesis. Caister Academic Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li C, Bakker RG, Motaleb MA, Sartakova ML, Cabello FC, Charon NW. Asymmetrical flagellar rotation in Borrelia burgdorferi nonchemotactic mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6169–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092010499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cockayne A, Bailey MJ, Penn CW. Analysis of sheath and core structures of the axial filament of Treponema pallidum. J Gen Microbiol. 1987;133:1397–407. doi: 10.1099/00221287-133-6-1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Norris SJ, Charon NW, Cook RG, Fuentes MD, Limberger RJ. Antigenic relatedness and N-terminal sequence homology define two classes of periplasmic flagellar proteins of Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum and Treponema phagedenis. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4072–82. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4072-4082.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radolf JD, Blanco DR, Miller JN, Lovett MA. Antigenic interrelationship between endoflagella of Treponema phagedenis biotype Reiter and Treponema pallidum (Nichols): molecular characterization of endoflagellar proteins. Infect Immun. 1986;54:626–34. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.3.626-634.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Izard J, Hsieh CE, Limberger RJ, Mannella CA, Marko M. Native cellular architecture of Treponema denticola revealed by cryo-electron tomography. J Struct Biol. 2008;163:10–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Izard J, Renken C, Hsieh CE, Desrosiers DC, Dunham-Ems S, La Vake C, Gebhardt LL, Limberger RJ, Cox DL, Marko M, Radolf JD. Cryo-electron tomography elucidates the molecular architecture of Treponema pallidum, the syphilis spirochete. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:7566–80. doi: 10.1128/JB.01031-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kudryashev M, Cyrklaff M, Baumeister W, Simon MM, Wallich R, Frischknecht F. Comparative cryo-electron tomography of pathogenic Lyme disease spirochetes. Mol Microbiol. 2009;71:1415–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murphy GE, Matson EG, Leadbetter JR, Berg HC, Jensen GJ. Novel ultrastructures of Treponema primitia and their implications for motility. Mol Microbiol. 2008;67:1184–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baumeister W. From proteomic inventory to architecture. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:933–7. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nickell S, Kofler C, Leis AP, Baumeister W. A visual approach to proteomics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:225–30. doi: 10.1038/nrm1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu J, Bartesaghi A, Borgnia MJ, Sapiro G, Subramaniam S. Molecular architecture of native HIV-1 gp120 trimers. Nature. 2008;455:109–13. doi: 10.1038/nature07159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu J, Taylor DW, Krementsova EB, Trybus KM, Taylor KA. Three-dimensional structure of the myosin V inhibited state by cryoelectron tomography. Nature. 2006;442:208–11. doi: 10.1038/nature04719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu J, Wu S, Reedy MC, Winkler H, Lucaveche C, Cheng Y, Reedy MK, Taylor KA. Electron tomography of swollen rigor fibers of insect flight muscle reveals a short and variably angled S2 domain. J Mol Biol. 2006;362:844–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winkler H. 3D reconstruction and processing of volumetric data in cryo-electron tomography. J Struct Biol. 2007;157:126–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu J, Lin T, Botkin DJ, McCrum E, Winkler H, Norris SJ. Intact flagellar motor of Borrelia burgdorferi revealed by cryo-electron tomography: evidence for stator ring curvature and rotor/C-ring assembly flexion. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:5026–36. doi: 10.1128/JB.00340-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Briegel A, Ortega DR, Tocheva EI, Wuichet K, Li Z, Chen S, Muller A, Iancu CV, Murphy GE, Dobro MJ, Zhulin IB, Jensen GJ. Universal architecture of bacterial chemoreceptor arrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:17181–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905181106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Radmacher M, Tillamnn RW, Fritz M, Gaub HE. From molecules to cells: imaging soft samples with the atomic force microscope. Science. 1992;257:1900–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1411505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walker EM, Borenstein LA, Blanco DR, Miller JN, Lovett MA. Analysis of outer membrane ultrastructure of pathogenic Treponema and Borrelia species by freeze-fracture electron microscopy. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5585–8. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.17.5585-5588.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murphy GE, Leadbetter JR, Jensen GJ. In situ structure of the complete Treponema primitia flagellar motor. Nature. 2006;442:1062–4. doi: 10.1038/nature05015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li C, Corum L, Morgan D, Rosey EL, Stanton TB, Charon NW. The spirochete FlaA periplasmic flagellar sheath protein impacts flagellar helicity. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:6698–706. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.23.6698-6706.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cameron CE. T. pallidum Outer Membrane and Outer Membrane Proteins. In: Radolf JD, Lukehart SA, editors. Pathogenic treponema: molecular and cellular biology. Caister Academic; Wymondham, Norfolk, England: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hazlett KR, Cox DL, Decaffmeyer M, Bennett MP, Desrosiers DC, La Vake CJ, La Vake ME, Bourell KW, Robinson EJ, Brasseur R, Radolf JD. TP0453, a concealed outer membrane protein of Treponema pallidum, enhances membrane permeability. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:6499–508. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.18.6499-6508.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cox DL, Chang P, McDowall AW, Radolf JD. The outer membrane, not a coat of host proteins, limits antigenicity of virulent Treponema pallidum. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1076–83. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.1076-1083.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Radolf JD, Bourell KW, Akins DR, Brusca JS, Norgard MV. Analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi membrane architecture by freeze-fracture electron microscopy. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:21–31. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.1.21-31.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Charon NW, Goldstein SF, Marko M, Hsieh C, Gebhardt LL, Motaleb MA, Wolgemuth CW, Limberger RJ, Rowe N. The flat-ribbon configuration of the periplasmic flagella of Borrelia burgdorferi and its relationship to motility and morphology. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:600–7. doi: 10.1128/JB.01288-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brandt ME, Riley BS, Radolf JD, Norgard MV. Immunogenic integral membrane proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi are lipoproteins. Infect Immun. 1990;58:983–91. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.4.983-991.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Porcella SF, Schwan TG. Borrelia burgdorferi and Treponema pallidum: a comparison of functional genomics, environmental adaptations, and pathogenic mechanisms. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:651–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI12484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chamberlain NR, Brandt ME, Erwin AL, Radolf JD, Norgard MV. Major integral membrane protein immunogens of Treponema pallidum are proteolipids. Infect Immun. 1989;57:2872–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.9.2872-2877.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brinkman MB, McGill MA, Pettersson J, Rogers A, Matejkova P, Smajs D, Weinstock GM, Norris SJ, Palzkill T. A novel Treponema pallidum antigen, TP0136, is an outer membrane protein that binds human fibronectin. Infect Immun. 2008;76:1848–57. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01424-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Centurion-Lara A, Castro C, Barrett L, Cameron C, Mostowfi M, Van Voorhis WC, Lukehart SA. Treponema pallidum major sheath protein homologue Tpr K is a target of opsonic antibody and the protective immune response. J Exp Med. 1999;189:647–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.4.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cullen PA, Cameron CE. Progress towards an effective syphilis vaccine: the past, present and future. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2006;5:67–80. doi: 10.1586/14760584.5.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yonekura K, Maki-Yonekura S, Namba K. Complete atomic model of the bacterial flagellar filament by electron cryomicroscopy. Nature. 2003;424:643–50. doi: 10.1038/nature01830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Galkin VE, Yu X, Bielnicki J, Heuser J, Ewing CP, Guerry P, Egelman EH. Divergence of quaternary structures among bacterial flagellar filaments. Science. 2008;320:382–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1155307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li C, Wolgemuth CW, Marko M, Morgan DG, Charon NW. Genetic analysis of spirochete flagellin proteins and their involvement in motility, filament assembly, and flagellar morphology. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:5607–15. doi: 10.1128/JB.00319-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pallen MJ, Penn CW, Chaudhuri RR. Bacterial flagellar diversity in the post-genomic era. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:143–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang Y, Stewart PE, Shi X, Li C. Development of a transposon mutagenesis system in the oral spirochete Treponema denticola. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:6461–4. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01424-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Izard J, Samsonoff WA, Kinoshita MB, Limberger RJ. Genetic and structural analyses of cytoplasmic filaments of wild-type Treponema phagedenis and a flagellar filament-deficient mutant. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6739–46. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.21.6739-6746.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Masuda K, Kawata T. Isolation and characterization of cytoplasmic fibrils from treponemes. Microbiol Immunol. 1989;33:619–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1989.tb02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kremer JR, Mastronarde DN, McIntosh JR. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J Struct Biol. 1996;116:71–6. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Winkler H, Taylor KA. Accurate marker-free alignment with simultaneous geometry determination and reconstruction of tilt series in electron tomography. Ultramicroscopy. 2006;106:240–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–12. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu S, Liu J, Reedy MC, Winkler H, Reedy MK, Taylor KA. Methods for identifying and averaging variable molecular conformations in tomograms of actively contracting insect flight muscle. J Struct Biol. 2009;168:485–502. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The T. pallidum periplasmic flagella and flagellar motor in situ. The flagella are located in the periplasmic space, while the motors are embedded in the cytoplasmic membrane. (A) and (C) are two organisms with the two most frequently observed morphologies - curved and straight. (B) and (D) are enlarged views of (A) and (C), respectively. White arrows indicate the location of a flagellar motor. Black arrows indicate the location of periplasmic flagella. Only one or two motors are visible in each tomogram section. The scale bar is 100nm.

Thin flagellar filaments lack the FlaA surface layer. Flagellar filaments were released from cells by repeated centrifugation and resuspension prior to immunogold labeling. (A and C) Immunolabeling with rabbit anti-FlaA antiserum. 12nm gold particles were primarily attached to 20nm thick flagellar filaments after FlaA antibody labeling. Few gold particles were associated with 14 nm thin flagellar filaments. (B) Labeling with rabbit anti-FlaB1 antiserum. Gold particles were mainly attached to thin filaments after anti-FlaB1 antibody treatment. (D) Control without primary antibody.