Abstract

Objective

Self-administered by spouses and other collateral informants, the nationally normed Older Adult Behavior Checklist (OABCL) provides standardized data on diverse aspects of older adult psychopathology and adaptive functioning. We tested the validity of the Older Adult Behavior Checklist (OABCL) scale scores in terms of associations with diagnoses of dementia of the Alzheimer’s type (DAT) and mood disorders (MD) and with 9 measures of psychopathology, cognitive performance, and adaptive functioning.

Method

Informants completed OABCLs for 727 60- to 97-year-olds recruited from a memory disorders clinic, geriatric psychiatry clinic, and community–dwelling seniors. OABCL scale scores were tested for associations with DAT and MD diagnoses, as well as with scores on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory, Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE), Clock Drawing Test, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale, Geriatric Depression Scale, Clinical Dementia Rating, Dementia Severity Rating Scale, Trail Making Test Part A, and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living.

Results

OABCL scales had medium to large correlations with the 9 other indices of functioning and significantly augmented MMSE discrimination between patients with DAT vs. MD. OABCL scales also discriminated significantly between patients diagnosed with DAT vs. MD and both these groups vs. nonclinical subjects.

Conclusions

Multiple OABCL scales had medium to large associations with diverse indices of functioning based on other kinds of data. The nationally normed OABCL provides new ways to integrate informant and self-report data to improve assessment of older adults. Specifically, the OABCL can provide discrimination between those who qualify for diagnoses of DAT vs. MD vs. neither diagnosis.

Keywords: Older Adult Behavior Checklist, Mini-Mental State Exam, Dementia of the Alzheimer’s Type, Mood Disorders, Neuropsychiatric Inventory

INTRODUCTION

Over 100 questionnaires and rating forms exist for assessing older adult psychopathology and adaptive functioning (Burns et al., 1999). Assessment of potentially cognitively impaired people is particularly challenging as it typically requires information from “informants” (e.g., spouses, children, family members, friends, and professional caregivers). However, meta-analyses show only modest agreement between informant reports and self-reports, even by people who are not impaired (Achenbach et al., 2005). Because informant reports often convey different information than self-reports, they can augment data obtained from patients, as shown by findings that they improve long-term outcome predictions beyond the predictive power of self-reports and clinical assessment (Tierney et al., 2003). Informant reports can thus span broad spectra of problems and strengths pertaining to diagnoses and other important characteristics.

To maximize utility, informant reports can be compared with norms and with self-reports on parallel instruments. Comparisons with norms reveal whether informant reports for particular subjects deviate from reports for non-impaired peers. Comparisons between informant reports and self-reports can highlight areas in which patients may lack awareness or insight regarding their cognitive, social, and other behaviors. Use of informant reports to identify deviations from norms and discrepancies from self-reports can help clinicians pinpoint areas for further evaluation and intervention.

We have developed the Older Adult Behavior Checklist (OABCL) to obtain informant reports and ratings of diverse problems and strengths that are described in everyday terms. Most existing geriatric measures have been developed using a “top down” approach to psychopathology in which a priori nosological notions are imposed on a specific population. By contrast, the OABCL (and the parallel Older Adult Self Report (OASR)), have been developed for adults aged 60+ using a “bottom up” or empirically-based approach to psychopathology. The empirically-based approach identifies a broad spectrum of behaviors and then statistically determines which behaviors tend to co-occur. The informant responds to 113 items describing problems interspersed with 20 items describing personal strengths, based on the subject’s functioning over the preceding 2 months. As detailed by Achenbach et al. (2004), the items were generated and iteratively tested by the authors based on items from the authors’ other adult instruments with the addition of items particularly relevant to geriatric individuals. An advantage is that the OABCL can be self-administered on paper or on the web or administered by lay interviewers in about 15 minutes, requiring no professional time. OABCL scores are compared to age- and gender-specific norms based on a US national sample spanning ages 60–98 and to similarly normed scores on the parallel OASR (Achenbach et al., 2004).

We tested the validity and utility of the OABCL for diagnostic differentiation of common geropsychiatric diagnoses by examining associations of OABCL scale scores with diagnoses of dementia of the Alzheimer’s type (DAT) and mood disorder (MD) and also with narrower-spectrum measures of psychopathology and adaptive functioning that use other assessment information. We hypothesized that diagnoses and narrower-spectrum measures would be significantly associated with corresponding OABCL scores. We also hypothesized that OABCL scores would significantly augment the ability of the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE; Folstein et al., 1975) and patient age, gender, and education to discriminate between patients receiving DAT versus MD diagnoses. Furthermore, we hypothesized that DAT, MD, and nonclinical subjects would differ significantly on OABCL scale scores, with the nonclinical subjects obtaining the most favorable scores.

METHODS

To test the validity and utility of the OABCL, we examined its performance in common geriatric clinical situations including a university-based memory disorders clinic (predominantly dementia diagnoses), and a university-based geriatric psychiatry outpatient clinic (predominantly affective disorders), and compared these results to those obtained from a non-clinical sample. All diagnosticians were blind to OABCL data.

Participants

Subjects (N = 727, ages 60–97; Table 1) were from outpatient memory and geriatric psychiatry clinics at the University of Vermont-Fletcher-Allen medical center serving urban, suburban, and rural Vermont and upstate New York and from 26 nonclinical settings in urban, suburban, and rural New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Vermont. The OABCL was completed by informants (spouses, partners, family, caregivers, friends) who had intimate knowledge of the subjects. No restrictions were imposed for time spent with the subject by the informant. Other assessments varied with settings. The University of Vermont Institutional Review Board approved the study. No subjects were excluded because of concomitant medication (cognitive enhancers, antidepressants, etc).

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the 727 Older Adults Assessed with the OABCL

| Range | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 60 – 97 | 75.6 (8.2) |

| Educationa | 1 – 9 | 3.9 (5.3) |

| SESb | 1 – 9 | 5.3 (2.3) |

| Ethnicity N (%) | 664 (91.4) White | |

| 39 (5.4) African-American | ||

| 23 (3.2) Other |

32.9% male/67.1% female

Education: 1 = No high school diploma to 9 = doctoral or law degree.

Hollingshead’s (1975) scale for occupation: 1 = lowest to 9 = highest. Descriptions of the 9 levels of education are displayed on the OABCL and in Achenbach et al. 2004

Memory clinic sample (N = 244)

For consecutively referred patients, the OABCL was sent for completion by informants prior to the initial clinic visit. At the second visit, 55 informants were asked to complete a second OABCL and 50 were asked to consent to telephone administration of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI; Cummings et al., 1994). Consenting informants were given a copy of the NPI to peruse. Those who completed the second OABCL and/or the NPI interview received $15.

Diagnoses were based on clinical examinations by physicians and neuropsychologists, including patient and informant interviews, physical/neurological exams, plus neuroimaging, laboratory tests, and family and medical history. In addition, neuropsychological test results included (but were not limited to): MMSE; Clock Drawing Test (CDT; Brodaty and Moore, 1997); Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-COG; Rosen et al., 1984); Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS; Yesavage et al., 1983); Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR; Morris, 1993); Dementia Severity Rating (DSR, modeled on the Global Deterioration Scale; Reisberg et al., 1982); Trail Making Test Part A (TRA; Reitan and Wolfson, 1993); and the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL; Lawton and Brody, 1969). These measures are part of the standard neuropsychological and cognitive battery at the Fletcher-Allen memory clinic..

Geriatric psychiatry clinic sample (N = 107)

The OABCL was completed by informants for consecutively referred patients. Diagnoses were based on clinical examinations by geriatric psychiatrists and psychiatric residents, using patient and informant interviews, physical/neurological exams, neuroimaging, laboratory tests, and family and medical history. Geriatric psychiatrists and psychiatry residents administered the MMSE, evaluated the patients, and used other assessments as indicated.

Nonclinical sample (N = 376)

The 26 sites in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Vermont included senior housing, senior centers, and a cognition study whose participants responded to advertisements and showed no evidence of cognitive impairment or psychopathology. Subjects obtaining MMSE scores < 27 or receiving mental health or substance abuse services in the preceding 12 months were excluded from the nonclinical sample. Although these screening criteria could have missed some psychopathology, false negatives would make our hypothesis-testing more conservative. Subjects completed the CDT and OASR and were given an OABCL with a consent form for completion by an informant who knew them well. Completed OABCLs and consent forms were mailed to the researchers. Subjects received $10, as did informants returning completed OABCLs.

Assessments

OABCL

The informant indicates the subject’s educational level on a 9-step scale and specifies the subject’s usual occupation. Items assessing the subject’s relations with friends and spouse/partner are followed by 113 items describing problems interspersed with 20 items describing personal strengths, rated as 0 = not true (as far as you know); 1 = somewhat or sometimes true; 2 = very true or often true, based on the preceding 2 months. Several items request brief descriptions (e.g., Can’t get mind off certain thoughts, obsessions; describe_____).

Adaptive functioning scales include Friends (4 items regarding relationships and contacts with friends); Spouse/Partner (for subjects cohabiting in the preceding 2 months, 7 items regarding relationship and satisfaction with spouse/partner); and Personal Strengths (20 items regarding use of time, self-care, relationships, performance of tasks, self-confidence). Problem items were selected for DSM-oriented scales by having 16 experts from 7 countries rate items as not consistent, somewhat consistent, or very consistent with specific diagnostic categories of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV). DSM-oriented scales designated as Depressive Problems, Anxiety Problems, Somatic Problems, Dementia Problems, Psychotic Problems, and Antisocial Personality Problems comprise items rated by ≥ 63% of the experts as very consistent with particular diagnoses (Achenbach et al., 2004). For a Critical Items scale, the experts identified 31 items as “definitely critical,” i.e., of particular clinical concern.

The following syndrome scales were factor-analytically derived from OABCLs (N = 741) and OASRs (N = 1,048) completed for subjects aged 60–99 years: Anxious/Depressed, Worries, Somatic Complaints, Functional Impairment, Memory/Cognition Problems, Thought Problems, and Irritable/Disinhibited. The syndrome scales comprise statistically identified patterns of co-occurring problems, whereas the DSM-oriented scales reflect experts’ judgments of problems corresponding to DSM diagnostic categories. Problem items are also summed to yield a Total Problems score. Scales were normed by gender for ages 60–75 and > 75. Eight-day test-retest correlations ranged from .90 for the DSM-oriented Anxiety Problems scale to .96 for the Functional Impairment syndrome scale, with a mean of .94 (Achenbach et al., 2004).

Diagnoses

Using clinical evaluations and all data except the OABCL, memory clinic neurologists and geropsychiatrists made DSM-IV diagnoses, which were later reviewed and confirmed by author PAN (a board-certified geriatric psychiatrist). Patients were classified as having (a) dementia of the Alzheimer’s type (DAT; N = 146) according to NINCDS-ADRDA criteria (McKhann et al., 1984), including possible and probable diagnoses, or (b) mood disorder (MD; N = 134), including probable or definite major depression or bipolar depression diagnoses according to DSM-IV criteria, or (c) neither (a) nor (b) (N = 447, including nonclinical subjects). To avoid confounding DAT and MD diagnoses, patients who were diagnosed with both disorders were eliminated from the analyses (N = 13).

Analyses

The following analyses tested the hypotheses: Pearson correlations of OABCL scores on three adaptive functioning scales, six DSM-oriented scales, seven syndrome scales, Total Problems, and Critical Items the 9 other measures; discriminant analyses classified patients as DAT versus MD via candidate predictors MMSE, demographics, DSM-oriented scales, and syndromes; M/ANCOVAs compared DAT, MD, and nonclinical groups on raw scores and on norm-based T scores for all OABCL scales. We hypothesized that OABCL syndrome scales would correlate negatively with favorable aspects of performance as measured by the MMSE, CDT, and TRA, but positively with impairment as measured by the NPI, ADAS-COG, GDS, CDR, DSR, IADL, and clinical diagnoses. We also hypothesized that OABCL adaptive functioning scales would correlate positively with favorable aspects of functioning measured by the MMSE and CDT, but negatively with the NPI, GDS, CDR, DSR, and IADL. To correct for chance, we determined the number of nominally significant effects expected by chance in each set of similar analyses and excluded that number having the smallest effect sizes (ESs) (Sakoda et al., 1954).

RESULTS

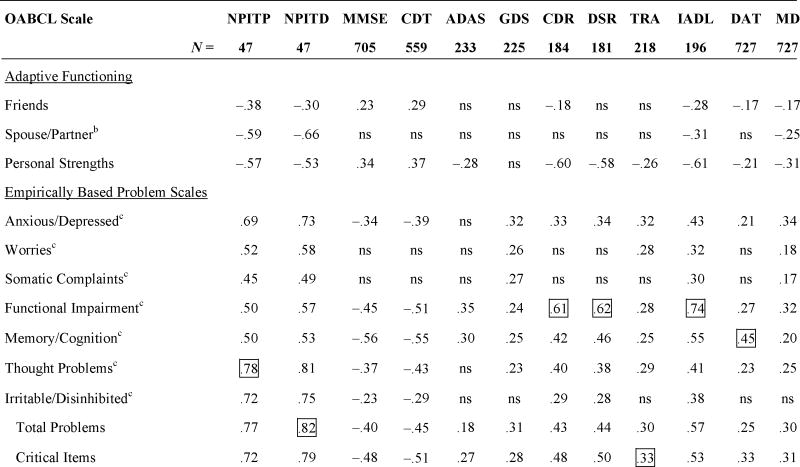

Table 2 presents significant correlations of OABCL scores with other indices, after correction for chance. As Table 2 shows, multiple OABCL scales correlated with every other index, with all significant correlations being in the predicted directions. By Cohen’s (1988) criteria for ESs, OABCL scales had large correlations (≥.50) with the NPI, MMSE, CDT, CDR, DSR, and IADL and medium correlations (.30–.49) with the ADAS, GDS, TRA, DAT diagnoses, and MD diagnoses. Other than the OABCL, only the NPI (administered and scored by clinicians) and IADL (questionnaire regarding subjects’ daily functioning) were scored solely from informants’ reports. The NPI Total Distress score had large correlations with multiple OABCL scales, up to .82 with OABCL Total Problems, as did the IADL score, with correlations up to .74 with OABCL Functional Impairment. NPI Total Distress correlated .50 with the IADL, but had no significant correlations with other non-OABCL indices.

TABLE 2.

Largest Bivariate Correlations Between OABCL Scale Scores and Each Other Index of Functioninga

|

|

Boxes indicate the strongest association of an OABCL scale with each other index; ns = correlations that were p>.05 after correction of alpha for the number of analyses (Sakoda et al., 1954).

NPI = Neuropsychiatric Inventory Total Problems (TP) and Total Distress (TD) caused by subject’s problems; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; CDT = Clock Drawing Test; ADAS = Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale; GDS = Geriatric Depression Scale; CDR = Clinical Dementia Rating; DSR = Dementia Severity Rating; TRA = Trail Making Test Part A; IADL = Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; DAT = Dementia of the Alzheimer’s type; MD = Mood disorder. All indices were based on direct assessments of subjects’ functioning except the NPI, which is a clinical interview of informants, and the IADL, which was completed by collaterals.

N who had lived with spouse/partner in the preceding 2 months ranged from 23 for the NPI to 313 for the diagnoses.

Factor-analytically derived syndrome scales.

Among direct assessments of subjects, the DSR correlated .62 and the CDR correlated .61 with OABCL Functional Impairment, while the MMSE correlated −.57 and the CDT correlated −.56 with OABCL DSM-oriented Dementia Problems. The TRA was least correlated with the OABCL (largest r = .33, p <.01 with OABCL Critical Items). The TRA’s correlations with nonOABCL indices were small to medium, except for its r of −.51 with the MMSE.

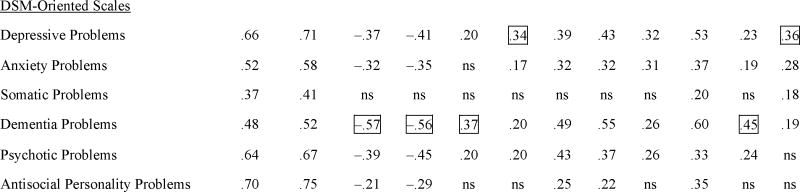

Other quantitative indices least correlated with OABCL scales were the GDS (largest r = .34, p <.01 with OABCL Depressive Problems), and the ADAS-COG (largest r = .37, p <.01 with OABCL Dementia Problems). Although diagnosticians had access to the ADAS and GDS but not to the OABCL scores, OABCL scales correlated higher with diagnoses than the ADAS and GDS did: OABCL Dementia Problems correlated .45 with DAT diagnoses versus .42 for the ADAS, while OABCL Depressive Problems correlated .36 with MD diagnoses versus .09 (nonsignificant) for the GDS.

Correlations Between Corresponding NPI and OABCL Narrow-band Scales

Because the NPI most resembles the OABCL in using informant reports to score subjects on multiple scales, we computed correlations between corresponding NPI and OABCL narrow-band scales. Table 3 displays the correlations that were significant at p <.01, after correction for chance. All correlations in Table 3 were large, except the medium correlation of .49 between the Irritable/Disinhibited syndrome and NPI Disinhibition. Other than the previously mentioned correlation of .82 between OABCL Total Problems and NPI Total Distress, the largest correlations were .72 between DSM-oriented Psychotic Problems and NPI Delusions and .68 between the Irritable/Disinhibited syndrome and NPI Irritability. Differences between the OABCL and NPI aggregations of particular problems are reflected in the substantial correlations of some OABCL scales with multiple NPI scales and vice versa. Examples include the correlations of the Irritable/Disinhibited syndrome with NPI Agitation, Disinhibition, and Irritability, and NPI Apathy with Personal Strengths (negative correlation) and Functional Impairment.

TABLE 3.

Significant (p <.01) Bivariate Correlations Between Corresponding NPI and OABCL Narrow-band Scales

| OABCL Scales | Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) Scales |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delusions | Hallucinations | Agitation | Depression | Anxiety | Apathy | Disinhibition | Irritability | |

| Adaptive Functioning | ||||||||

| Personal Strengths | −.61 | |||||||

| Syndromes | ||||||||

| Anxious/Depressed | .53 | .57 | ||||||

| Worries | .61 | |||||||

| Functional Impairment | .51 | |||||||

| Thought Problems | .57 | .63 | ||||||

| Irritable/Disinhibited | .55 | .49 | .68 | |||||

| DSM-Oriented Scales | ||||||||

| Depressive Problems | .59 | |||||||

| Anxiety Problems | .62 | |||||||

| Psychotic Problems | .72 | .65 | ||||||

| Antisocial Personality Problems | .67 | |||||||

N = 47. The Older Adult Behavior Checklist (OABCL) was independently completed by informants at a mean of 9.5 days (SD = 2.9) before the NPI was administered to the informants by clinical interviewers over the phone. The NPI scale scores were the sum of the problems reported on each scale. Correlations are Pearson rs, all of which were p <.01 and exceeded chance expectations for the number of analyses (Sakoda et al., 1954).

Discrimination Between DAT and MD Diagnoses

Because geriatric clinicians often need to distinguish DAT from depression (including major depressive disorder and bipolar depression), we tested the OABCL’s ability to augment MMSE discrimination between patients receiving DAT versus MD diagnoses in our clinical samples. For patients having complete data, 146 received DAT diagnoses and 134 MD diagnoses. We performed stepwise linear discriminant analysis with DAT versus MD as classification variable and candidate predictors being: Patient’s age, gender, education, MMSE, OABCL syndrome scores, and OABCL DSM-oriented scale scores. Education was preferable to occupation as an SES index because few patients held paid jobs at the time of assessment. With discriminant weights in parentheses, the final predictors remaining significant were MMSE (.85), OABCL Memory/Cognition Problems (−.30), and OABCL Anxious/Depressed (.14).

After “leave-one-out” cross-validation, 84% of the diagnoses were correctly classified, with .86 specificity (non-DAT diagnoses) and .82 sensitivity (DAT diagnoses). (Because discrimination was between MD and DAT, the .86 “specificity” is the “sensitivity” for correct classification of MD.)

Diagnostic Group Differences in OABCL Raw Scores

To test differences between OABCL scores for DAT, MD, and nonclinical subjects, we performed 2 (gender) × 3 (DAT vs. MD vs. nonclinical group) ANCOVAs on raw scores for Friends, Spouse/Partner, Personal Strengths, Total Problems, and Critical Items. Separate 2 × 3 MANCOVAs were performed for the seven syndromes and for the six DSM-oriented scales. Covariates were age and education. After excluding clinically referred subjects having neither DAT nor MD diagnoses, N was 635, except for Spouse/Partner where N was 259. Effect sizes (ESs) were partial eta2. Table 4 displays the M/ANCOVA statistics.

TABLE 4.

ANCOVA and MANCOVA Results

| Test | Gender | Groupa | Interaction | Covariates | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Education | |||||||||

| F | p | F | p | F | p | F | p | F | p | |

| ANCOVA | ||||||||||

| Friends | 7.73 | <.01b | 29.55 | <.001 | <1 | .48 | <1 | .74 | 6.04 | .01b |

| Spouse | 2.32 | .13 | 14.20 | <.001 | <1 | .65 | 1.16 | .28 | <1 | .56 |

| Personal Strengths | 8.59 | <.01b | 66.83 | <.001 | <1 | .40 | 17.61 | <.001b | 15.13 | <.001 |

| Total Problems | <1 | .53 | 97.92 | <.001 | <1 | .52 | <1 | .40 | 25.33 | <.001 |

| Critical Items | <1 | .48 | 141.33 | <.001 | 1.16 | .31 | 1.91 | .17 | 22.75 | <.001 |

| MANCOVA | ||||||||||

| Syndromes | ||||||||||

| Anxious/Depressed | 3.02 | .08 | 99.03 | <.001 | <1 | .52 | <1 | .64 | 21.48 | <.001 |

| Worries | 1.48 | .22 | 12.06 | <.001 | 1.05 | .35 | <1 | .57 | 32.42 | <.001 |

| Somatic Complaints | <1 | .36 | 11.14 | <.001 | 1.27 | .28 | <1 | .80 | 21.24 | <.001 |

| Functional Impairment | 6.65 | .01b | 115.83 | <.001 | 1.09 | .34 | 17.33 | <.001b | 9.13 | <.01 |

| Memory/Cognition | <1 | .33 | 208.62 | <.001 | 2.11 | .12 | 1.91 | .17 | 1.13 | .29 |

| Thought Problems | <1 | .65 | 65.14 | <.001 | 1.80 | .17 | <1 | .98 | 16.85 | <.001 |

| Irritable/Disinhibited | 1.36 | .25 | 19.40 | <.001 | 2.13 | .12 | <1 | .99 | 8.27 | <.01 b |

| DSM Scales | ||||||||||

| Depression Problems | <1 | .60 | 115.53 | <.001 | <1 | .90 | 2.78 | .10 | 19.37 | <.001 |

| Anxiety Problems | <1 | .42 | 72.07 | <.001 | <1 | .62 | <1 | .85 | 33.17 | <.001 |

| Somatic Problems | 2.92 | .09 | 12.40 | <.001 | <1 | .47 | 1.88 | .17 | 16.67 | <.001 |

| Dementia Problems | 1.63 | .20 | 180.04 | <.001 | 3.21 | .04b | 6.54 | .01b | 2.04 | .15 |

| Psychotic Problems | <1 | .97 | 46.84 | <.001 | <1 | .76 | <1 | .87 | 15.29 | <.001 |

| Antisocial Personality | <1 | .35 | 15.54 | <.001 | 2.99 | .05b | <1 | .64 | 4.60 | .03b |

There were 627 degrees of freedom in the denominators for all analyses, except Friends (df = 624) and Spouse (df = 251, because many subjects had not lived with a spouse/partner in the preceding 2 months). There was 1 degree of freedom in the numerator of all analyses except Group (DAT vs. MD vs. nonclinical) and gender x group, which both had 2 degrees of freedom.

Group = Dementia of the Alzheimer’s type vs. Mood disorders (MD) vs. nonclinical.

Not significant when corrected for the number of analyses of this variable (16).

Age, gender, and interaction effects did not exceed chance expectations. However, higher educational levels predicted significantly more favorable scores on all scales except Spouse/Partner, Memory/Cognition syndrome, and DSM-oriented Dementia Problems, with ESs (partial eta2) = .01 to .05.

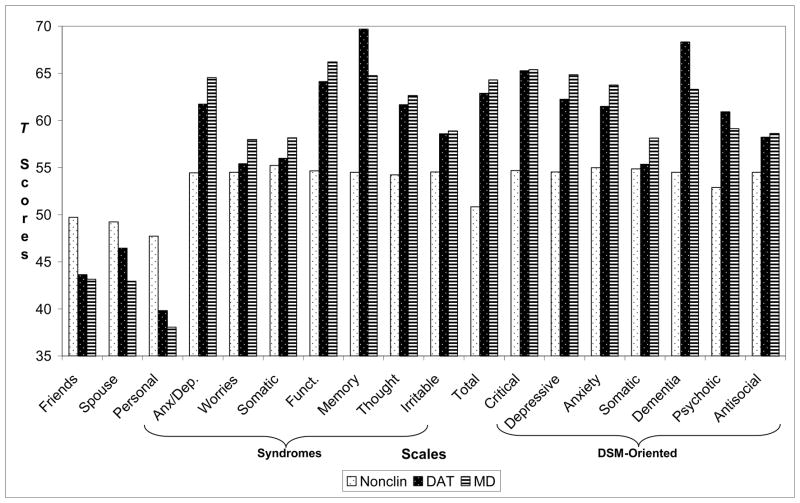

Diagnostic groups differed significantly (p <.001) on all scales. In M/ANCOVA, ESs .01–.059 are small, .059–.138 medium, and ≥ .138 large (Cohen, 1988). Differences among diagnostic groups showed large ESs (partial eta2 in parentheses) on the following scales: Personal Strengths (.18); Functional Impairment (.27); Anxious/Depressed (.24); Memory/Cognition Problems (.40); Thought Problems (.17); Total Problems (.24); Critical Items (.31); Depressive Problems (.27); Anxiety Problems (.19); and Dementia Problems (.37). Medium ESs were found for Irritable/Disinhibited (.06) and Psychotic Problems (.13). ESs on the other scales were small but significant (p<.001).

The nonclinical group scored highest on all adaptive functioning scales and lowest on all problem scales. The DAT group had the second highest scores on all adaptive functioning scales and the second lowest scores on all problem scales except Memory/Cognition Problems, Dementia Problems, and Psychotic Problems. Pairwise difference contrasts (SPSS, 2006) showed that each group differed significantly from the other two groups on Personal Strengths, Anxious/Depressed, Memory/Cognition Problems, Total Problems, Depressive Problems, Anxiety Problems, and Dementia Problems. On all other scales, two of the three contrasts were significant. The following differences between groups were nonsignificant (p >.05): (a) DAT versus MD on Functional Impairment, Irritable/Disinhibited, Thought Problems, Critical Items, Psychotic Problems, and Antisocial Personality Problems; (b) nonclinical versus DAT on Spouse/Partner, Worries, Somatic Complaints, and Somatic Problems.

Diagnostic Group Differences in OABCL Norm-based T Scores

OABCL norms enable users to view scales having different raw score distributions on a common metric of normalized T scores. For nonclinical, DAT, and MD groups, Figure 1 displays mean T scores, which are standardized separately by gender at ages 60–75 and >75. The lowest T score assigned to Critical Items, each syndrome scale, and each DSM-oriented scale is 50 (Achenbach et al., 2004), because so many members of the normative samples obtained raw scores of 0–2 that differentiation below the 50th percentile (T = 50) was dubious. The truncation of scales at T = 50 explains why the mean T scores in Figure 1 for the nonclinical group exceed 50 on these scales. M/ANCOVAs yielded significant differences between diagnostic groups on all T scores, paralleling findings for raw scores. However, mean T scores were similar for each gender/age group, because the T scores are standardized by gender and age.

Figure 1.

Mean T scores for nonclinical (Nonclin), dementia of the Alzheimer’s type (DAT), and mood disorder (MD) groups (N = 635) on OABCL scales: Anx/Dep = Anxious/Depressed syndrome; Funct. = Functional Impairment syndrome; Total = Total Problems. The scale designated as “Som Complaints” is an empirically derived syndrome, whereas the scale designated as “Som” is a DSM-oriented scale.

DISCUSSION

Older patients with multiple cognitive and emotional problems present major challenges to clinicians and other professionals. Comorbidities complicate assessment of psychopathology and adaptive functioning. Many geriatric assessment instruments are specialized, narrowly focused, lack adequate norms, and require much professional time (Burns et al., 1999). While not a substitute for more specialized procedures, the OABCL assesses diverse aspects of psychopathology and adaptive functioning, is completed by informants, has national norms, and is rapidly scored. Although some patients lack informants, the national norms for the OABCL and the parallel OASR can contribute an important normative component to diagnostic assessment.

Informant reports of dementia-related problems have been found to augment prediction of DAT diagnoses by instruments such as the MMSE (Jorm, 1999; Mackinnon et al., 2003; Tierney et al., 2003). Because geriatric clinicians must often distinguish between dementia and depression in cognitively impaired patients, we tested the OABCL’s augmentation of MMSE discrimination between patients diagnosed as DAT versus MD. Although diagnosticians were blind to OABCL but not to MMSE scores, the OABCL Memory/Cognition Problems and Anxious/Depressed syndromes added significantly to MMSE discrimination between DAT versus MD. It should be noted that associations of MMSE scores with diagnoses were probably enhanced by the diagnosticians’ knowledge of MMSE results. The diagnosticians’ blindness to OABCL results therefore made testing OABCL contributions more conservative than testing MMSE contributions. Furthermore, M/ANCOVAs showed that most OABCL scales significantly differentiated DAT versus MD patients and both groups from nonclinical subjects. Differences among DAT, MD, and nonclinical subjects yielded large ESs (eta2) on seven OABCL scales, ranging up to .37 on DSM-oriented Dementia Problems and .40 on Memory/Cognition Problems.

Multiple OABCL scales correlated significantly in the predicted directions with all other assessment indices, including large correlations with six and medium correlations with five. OABCL scales are thus associated with diverse indices of performance and functioning, and they significantly augment MMSE discrimination between DAT versus MD diagnoses. Although NPIs were administered and scored by clinical interviewers 9.5 days after OABCLs were independently completed by informants, all OABCL scales had medium to large correlations with their NPI counterparts.

Limitations included diagnoses that were made by the evaluating clinicians and were not verified by pathologic examination although DAT diagnoses were made according to current clinical standards. The informants did not have uniform relationships to the subjects. We also did not, in this initial study, examine the OABCL’s ability to assist with more fine-grained diagnostic differentiation (e.g. subtypes of dementia) nor did we attempt to examine stage of illness as a variable. As the number of subjects with bipolar depression was very small, we did not assess whether the OABCL can discriminate between unipolar and bipolar geriatric depression. Inclusion or exclusion of the small number of subjects with bipolar depression did not change the results. We used the GDS to assess mood disturbance, rather than instruments specific to depression in dementia, in order to apply a single instrument to the different subject groups. We do not believe that this alters the validity of the results. We did not examine relations between OABCL scores and self-completed OASR scores as many DAT patients could/would not complete the OASR (although most mood disorder patients did). Self and informant ratings in clinical populations will be compared in future research. Finally, although we included patients with disorders that are both severe and common, associations of OABCL scores with other diagnoses need to be tested.

The OASR/OABCL forms represent an approach to geriatric assessment based on instruments developed for younger ages and widely used in clinical services and research. Whereas numerous geriatric instruments offer patient or informant perspectives, the parallel OABCL and OASR enable direct comparisons between self and informant ratings. The need for multiple informants has long been recognized in child and adolescent psychopathology and is has become evident in geriatric assessment and research. Further research will assess the use of the similarly structured OASR as a geriatric self-report tool. As has been the case for translations of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and associated forms into over 85 languages, translations of the OABCL and OASR can be used to develop norms for countries in addition to the US.

Key points.

There is a need for systematically using informants’ reports to improve assessment and diagnosis of psychopathology in older adults.

Self-administered by spouses and other collaterals, the nationally normed Older Adult Behavior Checklist (OABCL) provides standardized data on diverse aspects of older adult psychopathology and adaptive functioning.

The validity of the OABCL was supported by associations with diagnoses of dementia of the Alzheimer’s type (DAT) and mood disorders (MD), plus numerous measures of psychopathology and adaptive functioning.

The OABCL and the parallel Older Adult Self-Report enable users to integrate data from collateral and self-reports for assessment of older adults and for discrimination between patients meeting criteria for DAT vs. MD vs. neither diagnosis.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families, a nonprofit corporation.

Footnotes

Research Conducted at: Fletcher Allen Health Care and University of Vermont.

Disclosure of Competing Interests

TMA: Co-author of the OABCL and President of the nonprofit 501(c)(3) Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families, which publishes the OABCL and supported this research.

BDB: None

LD: Part of salary was paid by the Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families until May, 2007.

PAN: Co-author of the OABCL; supported by R01 AG021476 and R01 AG022462

Contributor Information

Bartholomew D. Brigidi, Duke University Medical Center

Thomas M. Achenbach, University of Vermont College of Medicine

Levent Dumenci, University of Vermont College of Medicine

Paul A. Newhouse, University of Vermont College of Medicine

References

- Achenbach TM, Krukowski RA, Dumenci L, et al. Assessment of adult psychopathology: Meta-analyses and implications of cross-informant correlations. Psychol Bull. 2005;131:361–382. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Newhouse PA, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA Older Adult Forms & Profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; Burlington, VT: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty H, Moore CM. The Clock Drawing Test for dementia of the Alzheimer’s type: A comparison of three scoring methods in a memory disorders clinic. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1997;12:619–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns A, Lawlor B, Craig S. Assessment Scales in Old Age Psychiatry. Martin Dunitz; London: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2. Academic Press; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, et al. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–2314. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.12.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-mental state’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinican. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Unpublished manuscript. Yale University, Department of Sociology; New Haven, CT: 1975. Four Factor Index of Social Status. [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF. Methods of screening for dementia: A meta-analysis of studies comparing an informant questionnaire with a brief cognitive test. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11:158–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: Self maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon A, Khalilian A, Jorm AF, et al. Improving screening accuracy for dementia in a community sample by augmenting cognitive testing with informant report. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:358–366. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA work group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris J. The CDR: Current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;4:2412–2413. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ, et al. The Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:1136–1139. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.9.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Battery: Theory and Clinical Interpretation. Tucson Neuropsychological Press; Tucson, AZ: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL. A new rating scale for Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141:1356–1364. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.11.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakoda JM, Cohen BH, Beall G. Test of significance for a series of statistical tests. Psychol Bull. 1954;51:172–175. doi: 10.1037/h0059991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Inc. SPSS for Windows, Version 14.1 [Computer Software] Chicago, IL: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tierney M, Herrmann N, Geslani DM, et al. Contribution of informant and patient ratings to the accuracy of the Mini-Mental State Examination in predicting probable Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:813–818. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.51262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Lum O, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1983;17:37–45. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]